Abstract

Introduction

A significant proportion of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are administered intraoperatively; yet there is limited evidence to guide transfusion decisions in this setting. The objective of this systematic review is to explore the availability, quality and content of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) reporting on the indication for allogenic RBC transfusion during surgery.

Methods

Major electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL), guideline clearinghouses and Google Scholar, will be systematically searched from inception to January 2019 for CPGs pertaining to indications for intraoperative allogenic RBC transfusion. Characteristics of eligible guidelines will be reported in a summary table. The AGREE II instrument will be used to appraise the quality of identified guidelines. Recommendations advising on indications for intraoperative RBC transfusion will be manually extracted and presented to allow for comparison of similarities and/or discrepancies in the literature.

Ethics and dissemination

The results of this systematic review will be disseminated through relevant conferences and peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

CRD42018111487

Keywords: surgery, adult anaesthesia, paediatric anaesthesia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The proposed study is the first systematic review to identify the availability of practice guidelines advising on intraoperative red blood cell transfusion.

A multidisciplinary group of methodological and content experts are involved in this review.

The search strategy will be PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) reviewed.

Guidelines in all languages will be considered for inclusion.

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument, an internationally validated tool, will be used to assess the quality of guidelines by four independent reviewers.

Introduction

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions, although potentially lifesaving, are a costly and limited resource, associated with possible harm. Potential adverse outcomes range in severity, from minor to life-threatening. Relatively mild reactions include febrile non-haemolytic transfusion reactions, minor allergic reactions or development of RBC alloantibodies. RBC alloantibodies can usually be managed with the provision of antigen negative products.1 2 However, in the case of rare antibodies, development of alloantibodies can complicate administration of future blood products.1 Life-threatening transfusion reactions include anaphylaxis, transfusion-related acute lung injury, bacterial contamination of blood products resulting in sepsis, acute haemolytic transfusion reactions and transfusion associated circulatory overload.1 2 While the risk of transfusion transmitted viral infections has dropped drastically in recent years and the risk of this occurring is extremely low, it remains a concern when deciding to transfuse patients.2 RBC transfusions may also cause immunosuppression in the recipient, a process called ‘transfusion-related immunomodulation’ (TRIM).3 TRIM provides rationale for the negative association observed between RBC transfusion and postoperative adverse events as well as cancer recurrence in patients undergoing oncology surgery.4–10 At an estimated price tag of US$102–761 per unit, RBC transfusions are costly.11–14 They are also in short supply, relying on altruistic blood donors to ensure inventory stability.15 16 Given their associated risk, expense and scarcity, it is critical they are administered wisely.

There has been significant evolution in our understanding of humans’ ability to tolerate anaemia, resulting in a shift in approach to RBC transfusion prescribing practices from the ‘10/30’ rule (ie, transfusion indicated below a haemoglobin of 10 g/L or haematocrit <30%) to the widely accepted transfusion trigger of 70 g/L in the asymptomatic patient without significant cardiac comorbidity. This change came into effect following reporting of the TRICC trial and others that have shown the safety of a restrictive transfusion threshold.17–20 Importantly, the findings of these studies, which have impacted transfusion practices across a broad spectrum of clinical scenarios, are not necessarily applicable in the operative setting.

The operative setting presents a unique situation in which the indications for transfusion commonly reported in the non-operative patient have limited transferability. As blood loss, and consequently haemoglobin concentration can be unpredictable during surgery, haemoglobin concentrations may drop suddenly, making previous measurements of haemoglobin concentration invalid. This limits the feasibility of using specific haemoglobin levels to guide RBC transfusion administration in surgical patients.21 There is some literature to suggest estimated surgical blood loss can be used to guide transfusion decisions.22 23 However, there is good evidence to support the inability of clinicians to accurately predict blood loss.24 It is also important to appreciate that not all intraoperative bleeding is the same, varying from a persistent, slow ooze, to massive, rapid blood loss from a major vessel. Additionally, reliance on haemodynamics is complex as in addition to blood loss, it is a reflection of multiple variables, including but not limited to anaesthetic agents, patient positioning, presence of pneumoperitoneum and neurological stimulation.25 In the non-operative setting, acute blood loss of approximately 20% results in a compensatory tachycardia.26 However, because of the other variables at play in the anaesthetised patient, tachycardia is not a reliable marker of blood loss. Another common recommendation is to monitor for the presence of inadequate perfusion and oxygenation of vital organs.23 The ability to monitor for symptoms of decreased end-organ perfusion such as decreased level of consciousness, chest pain or abdominal pain is not possible in the unconscious patient under general anaesthesia. Incorporation of decision rules specific to surgical patient, such as monitoring for ST changes, is fundamental to guiding appropriate RBC transfusion for a patient under general anaesthesia for surgery.27 Another aspect unique to the unconscious patient under general anaesthesia, subject to dynamic changes in haemodynamics for a number of reasons, is our limited ability to identify transfusion reactions. Although literature in this area is lacking, it would be reasonable to hypothesise that transfusion reactions in the intraoperative setting are underreported. This, in combination with the evidence that patients who receive intraoperative transfusions suffer increased short-term and long-term morbidity, advocates for careful consideration of transfusion administration.7 28

The uncertainty of transfusion indications in this patient population is demonstrated by the abundance of literature reporting on the wide variability in transfusion practices but largely reporting overtransfusion of surgical patients.29–33 A recent survey of Canadian liver surgeons and anaesthesiologists highlights the lack of consensus between practitioners regarding indications for transfusion. In response to the question ‘what is the most important information you use to decide on intraoperative transfusion,’ the majority of anaesthesiologist selected haemoglobin value (47.2% vs 19% of surgeons; p<0.05), whereas surgeons selected haemodynamics (33.4% vs 14% of anaesthesiologist; p>0.05).34 A prospective observational study of intraoperative transfusion practices in Europe reported ‘physiologic trigger irrespective of haemoglobin’ as the most common indication for transfusion in a cohort of 5803 patients.35 Despite a global shift to a more restrictive transfusion strategy, wide variability in practice patterns in the intraoperative setting exists, and therefore warrants a review of the recommendations.

A preliminary search reveals guidance pertaining to RBC transfusion in the intraoperative patient population is lacking. Recently published guidelines from AABB, a worldwide leader in producing clinical practice guidelines for utilisation of blood components, neglected to provide recommendations on indications for RBC transfusion in the intraoperative setting likely due to a lack of evidence on which to base recommendations.36 Guidelines endorsed by surgical and anaesthesia societies offer vague recommendations with limited directives for when to transfuse, for example, to monitor for blood loss, check haemoglobin or haematocrit prior to transfusion, adopt a restrictive transfusion strategy or assess for adequate perfusion and oxygenation.37–41 As alluded to previously, reliance on these variables is limited in the intraoperative period. A formal review of the literature to understand available guidance for intraoperative RBC decisions is necessary.

In summary, blood transfusions are associated with possible harm and overtransfusion in the intraoperative setting is common. Although there is an abundance of guidance pertaining to indications for RBC transfusion, a review of guidance dedicated to the intraoperative patient does not currently exist.

Objective

The objective of this systematic review is to explore the availability, quality and consistency of published guidelines reporting on the indication for allogenic RBC transfusion in the intraoperative setting. We also aim to summarise the existing recommendations and associated level of evidence.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist guidelines were referenced for development of this protocol.42 43 A PRISMA-P checklist is available as a online supplementary document. The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 16 October 2018 (CRD42018111487).

bmjopen-2019-029684supp001.pdf (97.2KB, pdf)

Any amendments made to the current protocol will be published using a protocol addendum, accompanied by the date of and rationale for the reported amendment, with the final manuscript.

Eligibility criteria

Guidelines reporting on indications for allogenic RBC transfusion in the intraoperative setting will be considered for inclusion. Our definition of clinical practice guidelines is adopted from the Institute of Medicine and National Guideline Clearinghouse which define them as recommendations, derived from systematic review of evidence, from collective opinions of an expert panel, aimed at healthcare providers intended to improve patient care.44 45 An article will be included if it: (1) is presented as a clinical practice guideline; (2) is based on a systematic review of evidence; (3) is produced by a medical association, professional society, public or private organisation or government agency and not by an individual(s) not sponsored or supported by the above groups; (4) includes recommendations for indications for allogenic RBC transfusion in patients undergoing general anaesthesia in an operating room; (5) in any language; (6) full-text available.

We plan on excluding: (1) documents that do not meet the definition of a guideline as stated above; (2) guidelines pertaining to the perioperative period that do not make specific recommendations on the intraoperative setting; (3) previous documents replaced by updated versions from the same organisation.

Information sources and search strategy

MEDLINE (OVID interface, including In‐Process and Epub Ahead of Print) and EMBASE (OVID interface) and CINHAL will be systematically searched from inception to January 2019, through application of a search strategy developed by a health science librarian with expertise in systematic reviews. Search terms will include ‘allogenic red blood cell transfusion’, ‘guideline’ and ‘operative’. The search will not be restricted by date, language or patient population (ie, adult vs paediatric). A Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) will be performed by a second information specialist who is not associated with the project. A draft search strategy for Medline can be found in online supplementary appendix 1. The following guideline-specific databases will also be searched: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (UK), the Canadian Medical Association Infobase (Canada), the G-I-N International Guideline Library, the New Zealand Guidelines (NZG) Group, The WHO and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).46–51 Google Scholar will be searched with ‘(intraoperative OR perioperative) AND (guideline OR consensus OR recommendation OR statement)’ and the first 200 records will be screened. References of identified articles will be reviewed for relevant guidelines.

bmjopen-2019-029684supp002.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)

Study records

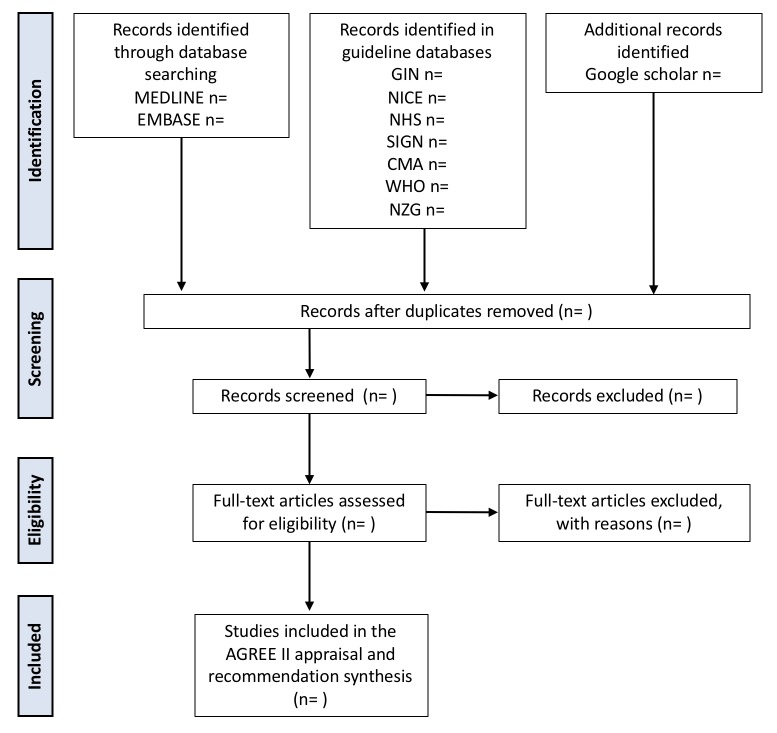

Articles identified through the electronic databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE) will be imported into Covidence, an online citation manager.52 All titles and abstracts identified will be independently screened by two reviewers for relevance and categorised as relevant, possibly relevant or irrelevant. Articles categorised as relevant or possibly relevant will be retrieved for further evaluation. Full texts will also reviewed in duplicate for eligibility. Google translate will be used to translate non-English, non-French articles, with the exception of those written in Chinese.53 Any disagreement regarding relevancy will be resolved by a senior author, independent from the reviewers. Reason for study exclusion will be documented and presented in the PRISMA flow diagram for study screening (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process.

Guidelines identified from the guideline repositories will be recorded in an Excel spread sheet.

Data items

Data pertaining to the publication details (authors, year of publication, journal and so on) will be identified. All relevant recommendations will be extracted from the guidelines to aid in the determination of population(s) in which the intraoperative transfusion guidelines pertain to (type of surgery), patient variables taken into consideration in determining appropriateness for transfusion, and grading of recommendation if assigned will be extracted. We will identify whether or not the following variables are accounted for in identified decision rules or recommendations: patient comorbidities—specifically a history of coronary artery disease, haemodynamics (hypotension, tachycardia or presence of vasopressor support), estimated blood loss, evidence of cardiac ischaemia and evidence of end organ ischaemia in addition to cardiac. Data extraction forms (DEF) will be developed and piloted independently by two reviewers on a set of five randomly selected guidelines. Modifications will be made to the DEF as necessary. Data will be extracted independently by two reviewers, in duplicate.

Outcomes and prioritisation

The objectives are to (1) characterise the clinical practice guidelines advising on intraoperative RBC utilisation, (2) appraise their quality and (3) provide a descriptive summary of the included guidelines.

Characterisation of identified guidelines

A descriptive table of identified guidelines will be presented. This table will include information publication information as well as the target patient population of the guideline.

Guideline quality assessment: AGREE II

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument will be used to assess the quality of included guidelines.54 The AGREE II instrument is a validated questionnaire aimed at assessing the methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines and has been widely adopted in the scientific literature.54–56 It is comprised of 23 questions scored on a seven-point Likert scale (whereby 7 indicates the highest quality), covering 6 domains, inclusive of scope and purpose of the guidelines, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation and editorial independent. There are two additional questions. The first assesses the overall quality of the guideline, rated on a seven-point Likert scale. The final question asks the evaluator whether they would recommend using this guideline, to which the assessor responds ‘yes,’ ‘yes, with modifications’ or ‘no’.

It is recommended that four assessors complete the AGREE II to achieve an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) ≥0.7. Four appraisers will therefore be selected to complete the online training and independently evaluate the included guidelines. Once complete, the evaluators will meet and discuss any scores differing by more than one point. At that point, evaluators can amend or keep their original score. Inter-rater reliability will be calculated using the ICC using SAS.

Domain scores will be reported separately using both the median and scaled domain scores, as is recommended by the AGREE II consortium. The scaled domain score will be calculated as follows: (obtained score-minimal possible score)/(maximal possible score-minimal possible score)=__%. The minimum possible score is calculated as: (number of questions) × (number of reviewers) × 1. The maximum possible score is calculated as: (number of questions) × (number of reviewers) × 7.

Recommendation synthesis

A descriptive table of included studies will be presented displaying all recommendations pertaining to indications for RBC transfusion in the intraoperative period. Recommendations will be compared for consistency and/or repetition.

Analysis of subgroups or subsets

Guidelines pertaining to indications for blood transfusion in cardiac versus non-cardiac surgery patients will be grouped and considered separately. In addition, guidelines published following publication of the TRICC trial in May 1997 will be considered separately in our descriptive analysis.18 The rationale for this being that the prevailing theme of current practice is a result of this trial.

Dissemination

The results of this review will be submitted for presentation at national and international meetings and publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Reporting of review

The findings of this systematic review will be reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) statement. The completed checklist will be provided as supplementary material.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The quality of recommendations will be evaluated by using the systematic and comprehensive approach known as Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE).57 The quality of evidence will be assessed across the domains of risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision and publication bias.

Patient and public involvement

This investigation is aligned with research priorities established by The Canadian Blood Services (CBS), a not-for-profit charitable organisation, responsible for managing the Canadian blood supply (with the exception of Quebec).58 Specifically, they have identified: (1) promoting appropriate blood product utilisation and (2) ensuring an adequate blood product supply, as two of five research priorities. CBS invites public participation in their biannual board meetings, where a number of issues are addressed, inclusive of priority research agendas. Patients or the public were not involved in the development of our specific research question or outcome measures of interests.

Discussion

A significant number of patients receive intraoperative transfusion. However, there is substantial variation in transfusion practice and a paucity of guidance available. Despite the fact that a plea for intraoperative blood transfusion guidelines was made over 20 years ago, widely adopted recommendations have yet to be developed.59 A systematic review of transfusion guidelines in the intraoperative setting has not previously been performed. Although a quality appraisal of RBC and plasma guidelines was published in 2018, it did not identify intraoperative recommendations.37 Additionally, their search strategy did not include guideline clearinghouses or the grey literature.

There are several methodological strengths of our review; these include multidisciplinary input, a PRESS reviewed search strategy, review of the grey literature and application of the AGREE II tool to assess the quality of identified guidelines by four independent reviewers.

This systematic review will allow for identification, appraisal and summary of literature devoted to the guidance of intraoperative allogenic RBC transfusion. The Perioperative Anesthesia Clinical Trials Group (PACT) identified transfusion as one of seven themes that has a significant impact on mortality, reinforcing the importance of this review.60 The results of this review will provide rationale and justification for development of guidance or the need for prospective evaluation of various intraoperative transfusion strategies. If evidence-informed recommendations for the use of intraoperative transfusion can be developed and disseminated the incidence of overtransfusion may be reduced, ensuring responsible use of this limited resource and minimising patient exposure to the risks of transfusion.

To achieve this goal will require collaboration between surgeons, anaesthetists and transfusion specialists. Given the paucity of high quality data on which to base guidelines, this collaboration must first identify areas where only expert opinion exists and propose methods for further examination. The input of patients who have had intraoperative transfusion should be sought to determine where patient preference may supersede rigorous adherence to guidelines. Following well planned knowledge translation phase, auditing to monitor compliance with the guidelines will need to be done. Additionally, following guideline implementation quality assurance initiatives with patient centred outcomes will also be necessary to ensure that the safety and tolerability of developed guidelines. Thus, it is unlikely that final guideline recommendations regarding intraoperative transfusion will be forthcoming in the near future. However, this review reinforces the urgent need to begin the undertaking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Josee Skuce for her help with developing and PRESS reviewing the search strategy as well as retrieving articles.

Footnotes

Contributors: LB and GM are responsible for aiding in the conception of the work, drafting and revising the manuscript, approves the submitted version and is accountable for all aspects of the work. LP, RG, AM, HA, AD, DIM, ES and AT are responsible for aiding in the conception of the work, revising the manuscript, approving the final version and are in agreement to being accountable for all aspects of the work. DAF and GM are responsible for aiding in the conception of the work, revising it for important intellectual content, give their approval of the content for publication and agree to accountability for all aspects of the work. DAF and GM are responsible for aiding in the conception of the work, revising it for important intellectual content, give their approval of the content for publication and agree to accountability for all aspects of the work. GM is the guarantor of the protocol.

Funding: Canadian Blood Services Blood Efficiency and Accelerator Award Program and The Academic Health Science Center Alternative Funding Plan Innovation Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Hendrickson JE, Roubinian NH, Chowdhury D, et al. Incidence of transfusion reactions: a multicenter study utilizing systematic active surveillance and expert adjudication. Transfusion 2016;56:2587–96. 10.1111/trf.13730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Candian Bloods Services. Clinical Guide to Transfusion: Adverse Reactions [Internet]. 2017. https://professionaleducation.blood.ca/en/transfusion/clinical-guide-transfusion.

- 3. Youssef LA, Spitalnik SL. Transfusion-related immunomodulation: a reappraisal. Curr Opin Hematol 2017;24:551–7. 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu HL, Tai YH, Lin SP, et al. The Impact of Blood Transfusion on Recurrence and Mortality Following Colorectal Cancer Resection: A Propensity Score Analysis of 4,030 Patients. Sci Rep 2018;8:13345 10.1038/s41598-018-31662-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hallet J, Tsang M, Cheng ES, et al. The Impact of Perioperative Red Blood Cell Transfusions on Long-Term Outcomes after Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:4038–45. 10.1245/s10434-015-4477-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xun Y, Tian H, Hu L, et al. The impact of perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion on prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after radical hepatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Medicine 2018;97:e12911 10.1097/MD.0000000000012911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glance LG, Dick AW, Mukamel DB, et al. Association between intraoperative blood transfusion and mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2011;114:283–92. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182054d06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernard AC, Davenport DL, Chang PK, et al. Intraoperative transfusion of 1 U to 2 U packed red blood cells is associated with increased 30-day mortality, surgical-site infection, pneumonia, and sepsis in general surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:931–7. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennett S, Baker LK, Martel G, et al. The impact of perioperative red blood cell transfusions in patients undergoing liver resection: a systematic review. HPB 2017;19:321–30. 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lyu X, Qiao W, Li D, et al. Impact of perioperative blood transfusion on clinical outcomes in patients with colorectal liver metastasis after hepatectomy: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:41740–8. 10.18632/oncotarget.16771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shander A, Hofmann A, Gombotz H, et al. Estimating the cost of blood: past, present, and future directions. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2007;21:271–89. 10.1016/j.bpa.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stokes EA, Wordsworth S, Staves J, et al. Accurate costs of blood transfusion: a microcosting of administering blood products in the United Kingdom National Health Service. Transfusion 2018;58:846–53. 10.1111/trf.14493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amin M, Fergusson D, Wilson K, et al. The societal unit cost of allogenic red blood cells and red blood cell transfusion in Canada. Transfusion 2004;44:1479–86. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amin M, Fergusson D, Aziz A, et al. The cost of allogeneic red blood cells--a systematic review. Transfus Med 2003;13:275–86. 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00454.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S, et al. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 2010;50:753–65. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Candian Bloods Services. National Blood Inventory. 2018. https://blood.ca/en

- 17. Hare GM. Tolerance of anemia: understanding the adaptive physiological mechanisms which promote survival. Transfus Apher Sci 2014;50:10–12. 10.1016/j.transci.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hébert PC, Wells G, Tweeddale M, et al. Does transfusion practice affect mortality in critically ill patients? Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1618–23. 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2453–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1012452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mazer CD, Whitlock RP, Fergusson DA, et al. Six-Month Outcomes after Restrictive or Liberal Transfusion for Cardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1224–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB*. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:49–58. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu WC, Smith TS, Henderson WG, et al. Operative blood loss, blood transfusion, and 30-day mortality in older patients after major noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2010;252:11–17. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e3e43f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adjuvant T. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Practice guidelines for perioperative blood transfusion and adjuvant therapies: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Anesthesiology 2006;105:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adkins AR, Lee D, Woody DJ, et al. Accuracy of blood loss estimations among anesthesia providers. Aana J 2014;82:300–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barash PG. Clinical Anesthesia Fundamentals. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein HG, Spahn DR, Carson JL. Red blood cell transfusion in clinical practice. Lancet 2007;370:415–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61197-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett S, Tinmouth A, McIsaac DI, et al. Ottawa Criteria for Appropriate Transfusions in Hepatectomy: Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Surg 2018;267:766–74. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Behrends M, DePalma G, Sands L, et al. Association between intraoperative blood transfusions and early postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:365–70. 10.1111/jgs.12143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choy YC, Lim WL, Ng SH, Sh N. Audit of perioperative blood transfusion. Med J Malaysia 2007;62:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spencer J, Thomas SR, Yardy G, et al. Are we overusing blood transfusing after elective joint replacement?--a simple method to reduce the use of a scarce resource. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005;87:28–30. 10.1308/1478708051379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niraj G, Puri GD, Arun D, et al. Assessment of intraoperative blood transfusion practice during elective non-cardiac surgery in an Indian tertiary care hospital. Br J Anaesth 2003;91:586–9. 10.1093/bja/aeg207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mallett SV, Peachey TD, Sanehi O, et al. Reducing red blood cell transfusion in elective surgical patients: the role of audit and practice guidelines. Anaesthesia 2000;55:1013–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01618-3.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hallissey MT, Crowson MC, Kiff RS, et al. Blood transfusion: an overused resource in colorectal cancer surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1992;74:59–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bennett S, Ayoub A, Tran A, et al. Current practices in perioperative blood management for patients undergoing liver resection: a survey of surgeons and anesthesiologists. Transfusion 2018;58:781–7. 10.1111/trf.14465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meier J, Filipescu D, Kozek-Langenecker S, et al. Intraoperative transfusion practices in Europe. Br J Anaesth 2016;116:255–61. 10.1093/bja/aev456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carson JL, Guyatt G, Heddle NM, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA 2016;316:2025–35. 10.1001/jama.2016.9185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pavenski K, Stanworth S, Fung M, et al. Quality of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Transfusion of Red Blood Cells and Plasma: A Systematic Review. Transfus Med Rev 2018:135–43. 10.1016/j.tmrv.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kozek-Langenecker SA, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013;30:270–382. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835f4d5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Practice Guidelines for blood component therapy: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Blood Component Therapy. Anesthesiology 1996;84:732–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klein AA, Arnold P, Bingham RM, et al. AAGBI guidelines: the use of blood components and their alternatives 2016. Anaesthesia 2016;71:829–42. 10.1111/anae.13489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moll FL, Powell JT, Fraedrich G, et al. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms clinical practice guidelines of the European society for vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S1–S58. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Clinical Practice Guidelines we can trst [press release]. The National Academies Press 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rozanski A, Slomka P, S Berman D, Sb D. Extending the Use of Coronary Calcium Scanning to Clinical Rather Than Just Screening Populations: Ready for Prime Time? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9(5). 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.004876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guidelines International Network. 2019. www.g-i-n.net.

- 47. National Institute for Health for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/.

- 48. National Health Service (NHS) Evidence. 2019. https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/.

- 49. Canadian Medical Association Infobase. 2019. https://joulecma.ca/cpg/homepage.

- 50. New Zealand Guidelines Group. 2019. https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/organizations/new-zealand-guidelines-group/.

- 51. World Health Organization. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/en/.

- 52. Ulrich-Vinther M, Carmody EE, Goater JJ, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated osteoprotegerin gene therapy inhibits wear debris-induced osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1405–12. 10.2106/00004623-200208000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Balk EM, Chung M, Chen ML, et al. Assessing the Accuracy of Google Translate to Allow Data Extraction From Trials Published in Non-English Languages. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2013;12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med 2010;51:421–4. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ 2010;182:1045–52. 10.1503/cmaj.091714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ 2010;182:E472–E478. 10.1503/cmaj.091716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Canadian Blood Services. Centre for Innovation Intramural Research Grant Program Guidelines. 2018. https://blood.ca/sites/default/files/Intramural_Research_Grant_Program_Guidelines_1.pdf.

- 59. Sudhindran S. Perioperative blood transfusion: a plea for guidelines. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1997;79:299–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Boet S, Etherington N, Nicola D, et al. Anesthesia interventions that alter perioperative mortality: a scoping review. Syst Rev 2018;7:218 10.1186/s13643-018-0863-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029684supp001.pdf (97.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029684supp002.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)