Abstract

Background: More research is needed in lymphedema management to strengthen the evidence base and ensure patients receive clinically and cost-effective treatment. It is critical that patients and clinicians are involved in prioritizing research to ensure that it reflects their needs and is not biased by commercial interests. This study aimed to set the research priorities for lymphedema management in the United Kingdom, through collaboration with patients, carers, and clinicians.

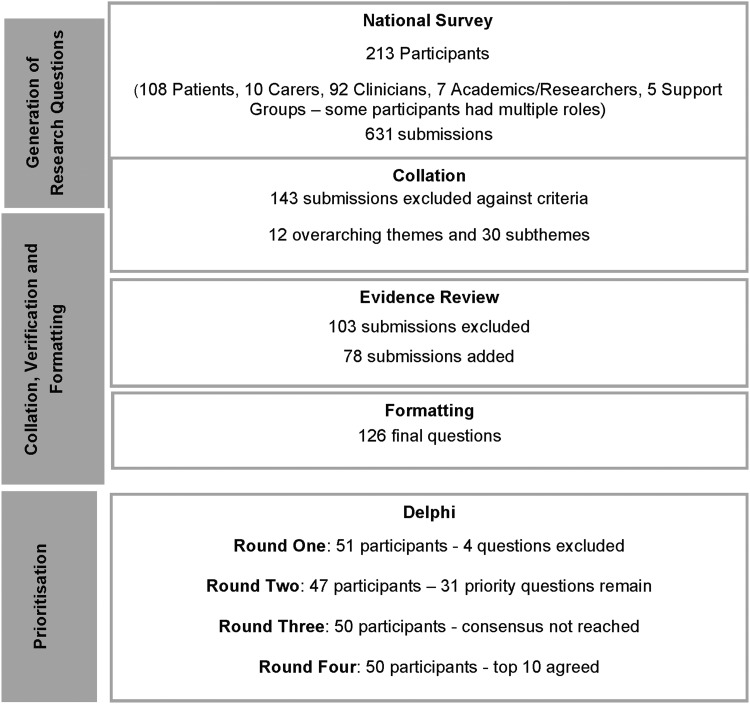

Methods and Results: Following the James Lind Alliance's methodology, a national survey was conducted to identify unanswered questions about lymphedema management from the perspective of patients, carers, and clinicians. These were collated and verified against an in-depth evidence review. Unanswered questions were formatted into broad research questions, which were prioritized by a purposive sample of patients, carers, and clinicians, using an online Delphi survey. The initial survey generated 631 submissions from 213 participants, including 108 patients, 9 carers, and 88 clinicians. Of these, 485 met inclusion criteria and were grouped into 12 overarching themes. The evidence review demonstrated that 101 submissions were answered by existing research and identified an additional 78 questions. The remaining unanswered submissions were collated into 126 broad research questions, which were prioritized over four rounds of the Delphi survey to produce the top 10 priorities.

Conclusions: This study is the first to attempt to systematically identify research priorities for lymphedema management in the United Kingdom, from the perspective of patients, carers, and clinicians. The results provide guidance for researchers and funders to ensure future research meets the needs of those living with lymphedema.

Keywords: research prioritization, patient and public involvement, lymphedema

Introduction

Lymphedema results from a failure of the lymphatic system and causes swelling, skin and tissue changes, and a predisposition to infection. It may affect any part of the body and occur at any age. Lymphedema is classified as either primary, caused by genetic lymphatic dysplasia, or secondary, caused by damage to the lymphatic system by an extrinsic process such as cancer and cancer treatment, trauma, disease, or infection.1 It is a chronic, progressive, and disabling condition, which impacts greatly on quality of life and requires life-long management.2,3 Although probably underestimated, it is thought that lymphedema affects ∼140–250 million people worldwide.4 In the United Kingdom, lymphedema is estimated to currently affect 3.93 per 1000 population, which increases with age to 10.31/1000 in those aged 65–74, rising to 28.75 in those aged over 85 years.5

Lymphedema remains a poorly evidenced speciality, relying largely on expert review and consensus6 with a paucity of randomized controlled studies and satisfactory meta-analysis,3,7 resulting in a weak and inconclusive evidence base.8,9 Further research is therefore needed to strengthen the evidence base and ensure patients receive the optimum treatment. To best utilize research funding, clinical research needs to ensure that it addresses priority questions that have not already been answered, are representative of patient's needs,10 and not driven by commercial interests and priorities,11 which are not necessarily those of patients and clinicians.12

Research prioritization has been conducted in many specialities. In lymphedema, priorities for breast cancer-related lymphedema have been established by an international expert consensus group13 and for lymphedema in general for the United Kingdom by clinicians.14 These studies, however, are no longer current and did not involve patients or carers. A more recent study, which established research priorities for morbidity control of lower limb lymphedema in India, successfully involved patients to prioritize seven research questions.15 These are however, specific to filariasis affected countries, and although western healthcare can learn much from this, our priorities are likely to be different.

The lymphedema research prioritization partnership aimed to set research priorities for the treatment and management of lymphedema in the United Kingdom, through collaboration with patients, carers, and clinicians, to inform research funding strategies and policies.

Materials and Methods

Governance

The study was conducted in collaboration with the Lymphedema Support Network (LSN), a U.K. charity which represents patients with lymphedema and their carers and the British Lymphology Society (BLS), a U.K. charity that represents clinicians, academics, and researchers in lymphedema. Both organizations were represented on the study steering group.

Ethical approval was gained from the Faculty of Health and Human Sciences Ethics Committee, Plymouth University (June 30, 2016) and undertaken in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were kept in accordance with the Data Protection Act.16

Methods

The study used the internationally accepted James Lind Alliance (JLA) methodology,17 which is recognized as the gold standard in research prioritization.18 This involves four stages: initiation, engagement, and generation of research ideas; collation, analysis, verification, and formatting of submissions; prioritization; and evaluation and dissemination, which are detailed below.

Data collection

Phase one: generation of research questions

A national qualitative, online and paper, survey was conducted over a 10-week period in 2016, with the aim of generating research questions. Surveys have been used in many other research prioritization studies19,20 and have been shown to generate more top 10 research priorities, reach a wider audience, provide greater breadth of information, and were more cost-effective than other methodologies.21

To gain as many wide-ranging perspectives as possible, the survey was presented at both the LSN and BLS conferences and advertised via their newsletters, website, and social media forums, which has proved an effective method of recruitment in other studies.22,23 In addition, individuals with lymphedema and clinicians were asked to publicize to their local support groups, and the Children's Lymphoedema Special Interest Group promoted the research during its Lymphaletics event for children and young people with lymphedema and their carers.

As this was a qualitative survey, a high number of respondents would not necessarily result in more or better research questions,17 and therefore, the focus was to ensure a representative sample of participants. Those eligible to complete the survey were people with lymphedema older than the age of 16 years, unpaid carers of individuals with lymphedema, clinicians treating patients with lymphedema, academics or researchers with an interest in lymphedema, and lymphedema support groups, with no geographical boundaries. All those who expressed an interest were provided with a participant information sheet; consent was presumed by virtue of them completing and returning the survey. Participants could complete the survey anonymously or add their contact details to enable them to be contacted to participate in phase three, the Delphi study, at which time the participants completed a separate consent and declaration of interest's form.

The survey was completed and returned either in paper form or online (cloud-based Bristol Online Surveys). Both versions were distributed at the LSN and BLS conferences and could be returned at the conference, by post or online. The survey asked a single open-ended question, paraphrased to ensure clarity for the respondent: “What questions about the treatment of Lymphedema do you feel need to be answered by research?” or “What questions about lymphedema treatment have you and your healthcare professional been unable to answer?.” Respondents were asked to submit up to five questions. Examples of questions from other unrelated JLA partnerships were also provided. Demographic data indicating the role of the participant (patient, carer, clinician, academic, researcher, or support group) and their country of residence were also collected.

Phase two: collation, verification, and formatting

Anonymized results from the online and paper-based versions of the survey were downloaded into a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet; to ensure transparency and maintain an audit trail, all submissions were given a unique code. The data were then screened for out-of-scope questions against agreed exclusion criteria by two researchers (E.U., K.R.), and the outcome verified by the steering group. Other studies have found that this screening process can potentially reduce the contribution of patients and carers, who may not have phrased their submission as a research question,24 therefore to ensure equity, submissions relating to broad themes were included. The agreed out-of-scope submissions were removed, and service dissatisfaction submissions were passed to the LSN and BLS to be used as illustrations of the impact of poor service provision. The remaining questions were then collated and analyzed, using an inductive approach to a group of similar questions into themes.25 This informed the evidence review, which in turn informed the thematic analysis.

The JLA17 states that a treatment uncertainty is a question that has not been answered by a systematic review of the evidence. An in-depth literature review was undertaken to verify the submissions, identify evidence gaps, and add additional unanswered questions identified in the research. Healthcare databases (AMED, BNI, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, JBI Library, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science) were searched from 2006 to 2017 for systematic reviews, nationally or internationally accepted clinical practice guidelines and future research need documents relating to the treatment or management of lymphedema; robust literature reviews were considered in the absence of a systematic review. In addition, consensus documents and clinical guidelines from the International Lymphoedema Framework, International Lymphology Society, and BLS were also included.

The systematic reviews were assessed for methodological validity by the primary researcher (E.U.), using the AMSTAR measurement tool26 adapted to provide a score for each systematic review; areas of conclusive evidence were identified and research questions extracted. The second reviewer (M.W.) reviewed any article where the confidence interval crossed the line of no effect to clarify its clinical relevance in the absence of statistical significance, and this was agreed in discussion with the primary researcher,17 areas of uncertainty were discussed with a third person (J.F.). Questions relating to areas of conclusive evidence with established effectiveness and those questions known to have been answered in the expert opinion of the steering group were excluded from phase three and were provided to the LSN and BLS to highlight the lack of awareness by the respondents of available evidence. The research recommendations from the literature were then added to the submitted questions.

The themes were then transformed into broad research questions, using population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO),27 wherever relevant. The steering group reviewed these questions to ensure that they reflected the submissions and were understandable and meaningful to patients, clinicians, and researchers. The questions were refined following discussion, and a glossary of terms was developed to help patients and carers understand the medical terminology.

Phase three: prioritization

An online Delphi survey was used in the prioritization phase to allow recruitment of a more representative sample from a wide geographical area at low cost, negating difficulties with traveling and time away from work or caring responsibilities.28 This approach also avoided issues of dominance in the group due to status or ability to articulate.29,30

The agreed list of research questions from phase two were prioritized over four rounds of the Delphi, with a purposive, representative sample of patients, carers, and clinicians, who volunteered in phase one, to gain consensus on a ranked list of the top 10 priorities. The sample for patients and carers was based on current estimated lymphedema prevalence figures: 78% Female, 20% Male, 2% Children, 60% Noncancer, and 40% Cancer,31 with maximum variation based on age, diagnosis, and time from diagnosis and geographical spread based on the U.K. population. Round one of the Delphi was an item reduction round and participants were asked to rate the importance of the question for research on a three-point Likert scale. The subsequent rounds asked the participant to rank the remaining questions in order of priority.

Results

Phase one and two

Overall 213 participants, including 118 patients/carers and 88 clinicians, completed the survey, which generated 631 submissions (illustrated in Fig. 1). After screening for out-of-scope questions, 488 remained. These were analyzed and collated into 12 broad themes and 30 subthemes, which informed the evidence review. The evidence review excluded 103 submissions as there was adequate evidence in the literature to answer these, and an additional 78 unanswered research questions were added as a result of the evidence review. The final 463 submissions were formulated into 126 broad research questions.

FIG. 1.

Summary of results for the lymphedema research prioritization partnership.

Phase three

A purposive sample of 27 patients, 3 carers, and 31 clinicians were selected from volunteers, to ensure broad representation. Round one of the Delphi received 51 responses, however, the item reduction was not successful as no questions were excluded by the participants. During this round, the JLA Cellulitis priority setting partnership published their priorities,32 and to avoid duplication four questions were excluded. Round two reduced the questions to a priority list of 31, which were ranked in rounds three and four, to reach final consensus on a ranked, top 10 research priorities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Top 10 Research Priorities for the Treatment and Management of Lymphedema in the United Kingdom

| 1. What early intervention modalities are the most effective in preventing or controlling lymphedema and preventing long-term complications? |

| 2. How effective are self-management regimes on the long-term management of lymphedema? |

| 3. Is it possible to promote the rerouting of lymphatic vessels with noninvasive treatment modalities to improve lymphatic drainage in lymphedema? |

| 4. How does exercise affect lymphatic flow, what exercises are the most beneficial for improving lymphatic drainage in upper and lower limb lymphedema and midline lymphedema (head and neck, trunk and genital) and what is the optimum protocol for these? |

| 5. What are the differential diagnostic criteria for cellulitis, erysipelas, inflammation, and bilateral red legs and how can these be utilized to enable prompt diagnosis and treatment by all care providers? |

| 6. What predictive risk factors are there for developing cancer-related lymphedema and how could these be assessed to reduce risk and inform cancer treatment decisions? |

| 7. Is MLD an effective treatment to improve the symptoms of and manage lymphedema and what are the long-term benefits of a course of MLD? |

| 8. What are the indications for surgical treatment of lymphedema and at what stage should each surgical technique optimally be used? |

| 9. Is ongoing specialist review needed for long-term management of lymphedema or can patients be safely discharged with self-management and review by generalist services? |

| 10. Which specific exercise regimes (i.e., swimming, walking, Pilates, yoga, weight training) are the most beneficial in improving lymphatic drainage of the upper and lower limb and which are contraindicated? |

MLD, manual lymphatic drainage.

Conclusions

Although research prioritization has been carried out in many specialities, this is the first attempt at systematically identifying the evidence gaps and treatment uncertainties for the management of lymphedema in the United Kingdom from the perspective of patients, carers, and clinicians and prioritizing them for research.

The strengths of this study are its use of the robust, structured, and transparent JLA methodology, the collaboration with the LSN and BLS, and the involvement of patients, carers, and clinicians nationally throughout the process. Of the 126 final questions, patients and carers contributed to 75 questions and clinicians to 82 questions. Only 15 questions were derived from the literature alone, which demonstrate the value of patient, carer, and clinician involvement in generating meaningful research questions. Finally the use of a steering group with patient, clinician, and researcher/academic representation to guide the study provided invaluable clinical and research expertise, reduced the risk of bias, ensured transparency, provided methodological rigor, and ensures that the developed research priorities are relevant and feasible.33

The results of this study should, however, be interpreted within the context of its limitations. The survey was predominantly Internet-based and was only available in English, which may have excluded some individuals from participating, and although membership of the LSN or BLS was not necessary to participate, they were the main source of advertising and therefore nonmembers may not have engaged in the study. The study was conducted in the United Kingdom and may therefore be most relevant to the U.K. healthcare setting. However, the evidence review included international research, and while the priorities may differ, the unanswered questions are likely to be similar; the list of potential research questions may therefore be of international relevance to other high-income countries.

This study has reached consensus on the top 10 research priorities for lymphedema management in the United Kingdom through collaboration with patients, carers, and clinicians. Through dissemination of these research priorities, it is hoped that research is generated, which addresses questions that are important to patients with lymphedema and the clinicians who treat them, with the goal of improving lymphedema management.

Acknowledgments

This study was only possible with the support of the patients, carers, and clinicians working in lymphedema, the LSN, and BLS. The study was supported by a British Lymphology Society Lymphoedema Research Grant. This article presents independent research which formed part of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded Masters in Clinical Research program.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Transforming Cancer Services Team for London T. Commissioning Guidance for Lymphoedema Services for Adults Living with and Beyond Cancer. Transforming Cancer Services Team for London; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armer JM, Hulett JM, Bernas M, Ostby P, Stewart BR, Cormier JN. Best-practice guidelines in assessment, risk reduction, management, and surveillance for post-breast cancer lymphedema. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 2013; 5:134–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Lymphoedema Framework. Compression Therapy: A Position Document on Compression Bandaging. 2nd ed. London: International Lymphoedema Framework; 2012:76 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greene AK, Borud LJ, Slavin SA. Lymphedema. Plastic Surgery Secrets Plus (Second Edition). Elsevier; 2010:630–635 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moffatt CJ, Keeley V, Franks PJ, Rich A, Pinnington LL. Chronic oedema: A prevalent health care problem for UK health services. Int Wound J 2017; 14:772–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema. International Consensus. London: MEP Ltd.; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2013; 46:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ezzo J, Manheimer E, McNeely L, Howell M, Weiss R, Johansson I, et al. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; CD003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stuiver M, ten RM, Agasi-Idenburg S, Lucas C, Aaronson K, Bossuyt MM. Conservative interventions for preventing clinically detectable upper-limb lymphoedema in patients who are at risk of developing lymphoedema after breast cancer therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; CD009765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014; 383:156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Partridge N, Scadding J. The James Lind Alliance: Patients and clinicians should jointly identify their priorities for clinical trials. Lancet 2004; 364:1923–1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buckley BS, Grant AM, Tincello DG, Wagg AS, Firkins L. Prioritizing research: Patients, carers, and clinicians working together to identify and prioritize important clinical uncertainties in urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2010; 29:708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petrek JA, Pressman PI, Smith RA. Lymphedema: Current issues in research and management. CA Cancer J Clin 2000; 50:292–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sitzia J, Harlow W. Lymphoedema 4: Research priorities in lymphoedema care. Br J Nurs 2002; 11:531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Narahari SR, Aggithaya MG, Moffatt C, Ryan TJ, Keeley V, Vijaya B, et al. Future research priorities for morbidity control of lymphedema. Indian J Dermatol 2017;62:33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Data Protection Act. Chapter 29. Legislation.gov.uk 1998. Available at www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/section/2

- 17. James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance Guidebook, Version 6. James Lind Alliance; 2016. Contract No.: 2/5/16

- 18. Smith JE, Morley R. The Emergency Medicine Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and the British Association for Accident & Emergency Medicine; 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, Toye F, Rees JL. Research priorities for shoulder surgery: Results of the 2015 James Lind Alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2016; 6:e010412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deane KH, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, Pascoe R, Penhale B, Clarke CE, et al. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson's disease. BMJ Open 2014; 4:e006434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crowe S, Regan S. Gathering Treatment Uncertainties from Patients/Carers Using Different Methods: Evaluation Report for Oxford Biomedical Research Centre—In association with the Oxford Health Experiences Research Group and the JLA Hip and Knee Replacement for Osteoarthritis. 2014(July):1–43

- 22. Layton A, Eady EA, Peat M, Whitehouse H, Levell N, Ridd M, et al. Identifying acne treatment uncertainties via a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. 2015: 5–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. INVOLVE. I. Guidance on the Use of Social media to Actively Involve People in Research. INVOLVE; 2017

- 24. Snow R, Crocker JC, Crowe S. Missed opportunities for impact in patient and carer involvement: A mixed methods case study of research priority setting. Res Involv Engagem 2015; 1:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research, a Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007; 7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64:395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1995;311:376–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Owens C, Ley A, Aitken P. Do different stakeholder groups share mental health research priorities? A four-arm Delphi study. Health Expectations 2008;11:418–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murphy M, Black N, Lamping D, McKee CM, Sanderson C, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England) 1998;2:1–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper G, Bagnall A. Prevalence of lymphoedema in the UK: Focus on the southwest and West Midlands. Br J Community Nurs 2016; Suppl:S6–S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas K, Brindle R, Chalmers J, Gamble B, Francis N, Hardy D, et al. Identifying priority areas for research into the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cellulitis (erysipelas)—Results of a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177:541–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R, Walsh J, Stewart J. Health research priority setting in selected high income countries: A narrative review of methods used and recommendations for future practice. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2014; 12:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]