Abstract

Background

Clinical practice is not always evidence‐based and, therefore, may not optimise patient outcomes. Local opinion leaders (OLs) are individuals perceived as credible and trustworthy, who disseminate and implement best evidence, for instance through informal one‐to‐one teaching or community outreach education visits. The use of OLs is a promising strategy to bridge evidence‐practice gaps. This is an update of a Cochrane review published in 2011.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of local opinion leaders to improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice and patient outcomes.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, three other databases and two trials registers on 3 July 2018, together with searching reference lists of included studies and contacting experts in the field.

Selection criteria

We considered randomised studies comparing the effects of local opinion leaders, either alone or with a single or more intervention(s) to disseminate evidence‐based practice, with no intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more intervention(s). Eligible studies were those reporting objective measures of professional performance, for example, the percentage of patients being prescribed a specific drug or health outcomes, or both. We included all studies independently of the method used to identify OLs.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane procedures in this review. The main comparison was (i) between any intervention involving OLs (OLs alone, OLs with a single or more intervention(s)) versus any comparison intervention (no intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more intervention(s)). We also made four secondary comparisons: ii) OLs alone versus no intervention, iii) OLs alone versus a single intervention, iv) OLs, with a single or more intervention(s) versus the same single or more intervention(s), and v) OLs with a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention.

Main results

We included 24 studies, involving more than 337 hospitals, 350 primary care practices, 3005 healthcare professionals, and 29,167 patients (not all studies reported this information). A majority of studies were from North America, and all were conducted in high‐income countries. Eighteen of these studies (21 comparisons, 71 compliance outcomes) contributed to the median adjusted risk difference (RD) for the main comparison. The median duration of follow‐up was 12 months (range 2 to 30 months). The results suggested that the OL interventions probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (10.8% absolute improvement in compliance, interquartile range (IQR): 3.5% to 14.6%; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Results for the secondary comparisons also suggested that OLs probably improve compliance with evidence‐based practice (moderate‐certainty evidence): i) OLs alone versus no intervention: RD (IQR): 9.15% (‐0.3% to 15%); ii) OLs alone versus a single intervention: RD (range): 13.8% (12% to 15.5%); iii) OLs, with a single or more intervention(s) versus the same single or more intervention(s): RD (IQR): 7.1% (‐1.4% to 19%); iv) OLs with a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention: RD (IQR):10.25% (0.6% to 15.75%).

It is uncertain if OLs alone, or in combination with other intervention(s), may lead to improved patient outcomes (3 studies; 5 dichotomous outcomes) since the certainty of evidence was very low. For two of the secondary comparisons, the IQR included the possibility of a small negative effect of the OL intervention. Possible explanations for the occasional negative effects are, for example, the possibility that the OLs may have prioritised some outcomes, at the expense of others, or that an unaccounted outcome difference at baseline, may have given a faulty impression of a negative effect of the intervention at follow‐up. No study reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

We were unable to determine the comparative effectiveness of different approaches to identifying OLs, as most studies used the sociometric method. Nor could we determine which methods used by OLs to educate their peers were most effective, as the methods were poorly described in most studies. In addition, we could not determine whether OL teams were more effective than single OLs.

Authors' conclusions

Local opinion leaders alone, or in combination with other interventions, can be effective in promoting evidence‐based practice, but the effectiveness varies both within and between studies.The effect on patient outcomes is uncertain. The costs and the cost‐effectiveness of the intervention(s) is unknown. These results are based on heterogeneous studies differing in types of intervention, setting, and outcomes. In most studies, the role and actions of the OL were not clearly described, and we cannot, therefore, comment on strategies to enhance their effectiveness. It is also not clear whether the methods used to identify OLs are important for their effectiveness, or whether the effect differs if education is delivered by single OLs or by multidisciplinary OL teams. Further research may help us to understand how these factors affect the effectiveness of OLs.

Plain language summary

Are local opinion leaders effective in promoting best practice of healthcare professionals and improving patient outcomes?

Background

In order to improve patient outcomes, it is important to translate evidence‐based research into practice. One way of doing this may be through the use of local opinion leaders (OLs). OLs are people who are seen as likeable, trustworthy and influential, and who through the use of different methods, e.g. community outreach visits and small group teaching, can educate healthcare professionals and persuade them to use the best available evidence.

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane review was to find out whether OLs can persuade healthcare professionals to follow evidence‐based guidelines when treating patients with the goal of improving patient health outcomes. This is an update of a systematic review published in 2011.

Key messages

The use of OLs probably improves the ability of healthcare professionals to follow evidence‐based guidelines, but we do not know if patient outcomes are improved. To optimise the use of OLs, we need to know more details about what they actually do and how they do it.

What was studied in this review?

Cochrane review authors searched for all relevant studies evaluating the effects of OLs and found 24 relevant studies.

The healthcare professionals targeted by the OL intervention were usually physicians. The clinical condition varied across studies, with the most common being cancer.

The main comparison was between any intervention including OLs as compared to no intervention or interventions that did not involve OLs. We also wanted to find out whether the effects of OLs would vary depending on a) the method used by researchers to identify OLs; b) the educational methods used by OLs to encourage practice change; or c) whether a single OL, or a multidisciplinary OL team delivered the intervention.

We examined whether the intervention had an effect on healthcare professional compliance with evidence‐based practice, patient outcomes, and costs.

What are the main results of the review?

We included 24 studies, involving 337 hospitals, 350 primary care practices, 3005 healthcare professionals, and 29,167 patients (not all studies reported this information). Most studies were from North America (N = 20) and all were conducted in high‐income countries. Eighteen of the 24 studies reported the effects of healthcare professional compliance with evidence‐based practice.

The review found that, overall, any intervention involving OLs probably improves healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice. The effect, however, varies within and across studies. The certainty of evidence was moderate for all comparisons. Occasional results suggested the possibility of a small negative effect of the OL intervention on some outcomes, which may have been caused by OLs prioritising some outcomes, at the expense of others, or that an unfavourable baseline difference might have given a faulty impression of a negative effect at follow‐up.

We know little about the effectiveness of OLs on patient outcomes, since few studies reported patient outcomes and the certainty of this evidence was very low. No study reported on costs. We could not determine whether different methods used to identify OLs had an impact on their effectiveness, as the same method was used in most studies. We were unable to determine which types of educational strategies used by OLs to implement best practice were most effective, as in many studies there was very little description. Lastly, we could not tell whether OL teams were more effective than single OLs because there were no comparisons.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to July 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The translation of evidence into clinical practice is often slow, unpredictable and incomplete (Grimshaw 2012, Grol 1999; Morris 2011). Studies have estimated that between 30% to 40% of patients do not receive treatment that accords with research evidence. Further, 20% of patients receive treatments that have been proven to be detrimental (Grol 2001; Schuster 1998).There is significant interest in devising innovative methods to promote knowledge transfer of evidence into practice and ultimately improve patient healthcare (Curtis 2016; Grimshaw 2012; Grol 1999), including the use of opinion leaders to disseminate evidence‐based practice.

Description of the intervention

Social Learning Theory hypothesises that individuals perceived as 'credible', 'likeable' and 'trustworthy' are likely to be persuasive agents of behavioural change. Such 'opinion leaders' may play a key role in assisting individuals to identify the evidence underpinning best practice and to facilitate behaviour change (Rogers 1976). Opinion leadership (more properly termed 'Informal Opinion Leadership') is the degree to which an individual is able to influence other individuals' attitudes or overt behaviour informally, in a desired way with relative frequency (Rogers 1995). This informal leadership is not a function of the individual's formal position or status in the system; it is earned and maintained by the individual's technical competence, social accessibility, and conformity to the system's norms. When compared to their peers, opinion leaders (hereafter OLs) tend to be more exposed to all forms of external communication, have somewhat higher social status, and to be more innovative. However, the most striking feature of OLs is their unique and influential position in their system's communication structure; they are at the centre of interpersonal communication networks – interconnected individuals who are linked by patterned flows of information. Their use has been explored in different clinical disciplines such as surgery, obstetrics, paediatrics, neurology, general medicine, nursing and infection control (Albrecht 2016; Gifford 1999; Rogers 1995; Ryan 2002). OLs are a specific type of 'change agent'. The underlying theory about why OLs work is that they socially influence other professionals and that their influence is a function of the respect of their peers (Mittman 1992). As a result, it is important that the method of identification respects this mechanism of action. OLs should not be confused with 'champions'. Champions are appointed by management. It is unclear whether they function as OLs and whether they function through social influence or managerial status/process. Hence, they are a different type of 'change agent', and a different type of intervention.

How the intervention might work

Theoretically, OLs use a range of interpersonal skills in order to achieve desired behavioural change. However, there is considerable variation in the types of educational initiatives OLs use to implement best practice. Informal one‐to‐one teaching, community outreach education visits, small group teaching, academic detailing, and preceptorships are examples of strategies used by OLs for disseminating and implementing evidence‐based practice (Rogers 1995; Ryan 2002;). Whilst OLs have also used formal strategies, such as delivering didactic lectures, education delivered informally is regarded as a key ingredient in marketing and innovation diffusion (Rogers 1976). However, it is unclear whether education delivered by OLs in an informal way is more persuasive compared with formal strategies. Formalising the educational process may produce more diverse results than those in which the role of OLs is allowed to be self‐directed (Rogers 1995; Ryan 2002). It has been suggested that OLs may be less influential when their role is formalised through mail‐outs, workshops or teaching rounds (Ryan 2002). Research also suggests that the setting of an opinion leader intervention may be important for its success, that is, that opinion leader interventions in secondary care may be more effective than in primary care, due to more complex social networks in the former (Grimshaw 2006a). It has also been proposed that different OLs may be needed for different clinical issues (Grimshaw 2006a). Finally, if there is a feasibility issue with using OLs, due to their temporal instability, there may be a need for successive identification processes (Doumit 2006).

Another issue is whether the process by which OLs are selected affects the success or otherwise of their educational initiatives. Theory‐based methods used to identify OLs can be broadly classified into four categories: the observation method, the self‐designating method, the informant method, and the sociometric method (Rogers 1995) though this list of methods has recently been expanded (Valente 2007).The observation method employs an independent observer to identify OLs amongst a group of professionals interacting with one another in a work context. The self‐designating method requires that members of a professional network report their own perceptions of their role as an opinion leader. The informant method relies on asking individuals to identify those individuals who act as principal sources of influence. Via a standardised, self‐reported questionnaire, the sociometric method asks members of a social network to judge individuals according to the extent to which they are educationally influential, knowledgeable and humanistic. Methods used to select OLs have not been consistent across studies. Moreover, different methods result in different individuals being identified as OLs (Grimshaw 2006a). The question of whether any one method is more likely to identify OLs that are more effective in promoting knowledge transfer remains open to empirical assessment. We have expanded this review to also include studies that have used other methods than the four previously defined to identify OLs (Valente 2007). The methods, which show some overlap with those described above, include: i) the use of celebrities; ii) self‐selection, that is, individuals, who are not necessarily seen as educationally influential, are selected via word‐of‐mouth, printed material, or other forms of media, and essentially volunteer as an opinion leader; iii) self‐identification, by which individuals respond to a survey measuring their perceptions of their own opinion leadership and who select those as OLs who score the highest on the scale and/or who perceive themselves as influential; iv) staff selection, that is, project staff select OLs based on community observations; v) positional approach, that is, selection of OLs are based on their occupational or organisational roles; vi) judges’ ratings method, which uses key informants to identify potential OLs; and vii) expert Identification method, which uses trained scientists who act as participant observers to identify potential OLs. The latter two methods rely on knowledgeable individuals within a community to identify leaders rather than project staff, and are both similar to the informant method described above. Three methods use social network analysis methods to identify OLs: viii) snowball method, ix) sample sociometric method, and x) sociometric method. The snowball method is an iterative process, which starts with a randomly selected sample who are asked to nominate OLs in the community. Individuals nominated in the first round can be interviewed in the second round, and so forth, and this process is repeated until a sufficient number of OLs are identified. The sample sociometric method starts with a representative sample who are asked to nominate OLs, while the sociometric method involves interviewing all (or almost all) community members whereafter a social network is constructed from the nominations. These three methods select OLs based on a predetermined threshold of nominations. The comparable effectiveness of all these methods is unknown.

Why it is important to do this review

In order to improve patient outcomes and decrease inappropriate or potentially harmful patient treatments, it is important to speed up and optimise the process of translating evidence‐based research into practice. One way of doing this may be through the use of local OLs. Several aspects of OL interventions need further investigation to be able to advise on their best use. We report an update of the previous Cochrane review to determine the effectiveness of the use of OLs targeted at changing the behaviours of professionals and improving the healthcare outcomes of their patients. This is the third update of the Cochrane review (Thomson 1999). Our update uses revised methods to systematically assess the overall risk of bias of included studies and to grade the certainty of evidence; it extends the previously published review (Flodgren 2011) by including studies independently of methods used to identify OLs (i.e. not only the four previously described methods). We did this, since is not known which method is most effective in identifying OLs, and also to provide decision‐ and policy‐makers with a fuller picture of the effectiveness of OLs.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of local OLs in improving healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice and patient outcomes.

We sought to answer the following questions:

What is the effectiveness of OLs alone compared to no intervention?

What is the effectiveness of OLs alone compared to a single intervention?

What is the effectiveness of OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) compared to the same single or more intervention(s)?

What is the effectiveness of OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) compared to no intervention?

Does the effectiveness of OLs vary according to the method used by researchers to identify OLs?

Does the effectiveness of OLs vary according to the educational methods used by OLs to encourage knowledge translation? We intended to compare informal education (e.g. one‐to‐one teaching) versus formal education (e.g. community outreach education, small group teaching, academic detailing, and preceptorships).

Does the effectiveness of a OLs vary according to whether a single opinion leader or a multidisciplinary opinion leader team deliver the intervention?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised trials only (including cluster‐randomised trials) only, since they provide the best available evidence of effect.

Types of participants

Healthcare professionals in charge of patient care. We excluded studies involving undergraduate students.

Types of interventions

Any intervention evaluating the effectiveness of OLs, either alone or in combination with other interventions, for improving the behaviour of healthcare professionals, i.e. compliance with evidence‐based practice (evidence‐based guidelines or recommendations) and patient outcomes. OLs could have been identified by either the four previously defined methods: sociometric method, informant method, self designating method, observation method, or by other methods (e.g. judge's rating, snowball method) (Valente 2007).

Types of outcome measures

Objective dichotomous measures of professional performance (i.e. compliance with evidence‐based practice), for example, the percentage of patients being prescribed a specific drug (receiving a target process of care), documentation of performance of a specific task, such as weight counselling, or proportion of patients whose care is in compliance with an overall guideline) or patient outcomes. We included cost data, if available. We excluded studies that measured knowledge or performance in a test situation only. We did not address equity issues in this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases for primary studies on 3 July 2018:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 6) in The Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE, Ovid (including Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Versions);

Embase, Ovid;

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: Global, UK & Ireland;

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐Expanded);

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI);

Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S).

Search strategies were comprised of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no language limits. We searched all databases from the date of the last search in the previous version of the review (Flodgren 2011). One review author (GF) also searched the reference lists of included studies.

All strategies used are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Trial Registries

We searched the following trials registers on 3 July 2018:

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Word Health Organization (WHO) www.who.int/ictrp/en/;

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinicaltrials.gov/.

Grey Literature

We also searched the following databases for grey literature not indexed in the databases listed above:

Index to Theses (http://www.theses.com/) (2005, July 2018);

WorldCat Dissertations, OCLC (2005, July 2018);

HMIC, Ovid (2005, July 2018).

We also conducted a cited reference search for citations of any previous version of the review using Science Citation Index (searched 3 July 2018).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

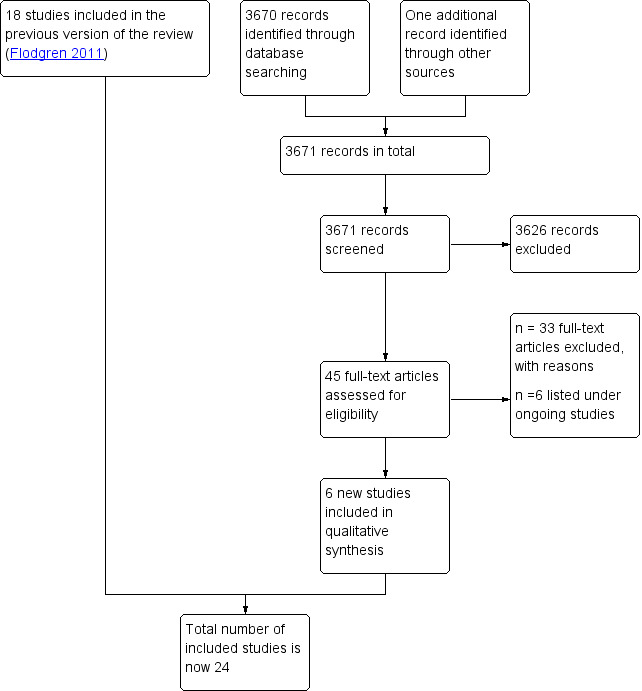

See Figure 1. Two review authors (GF, EP or MAOB) independently screened all titles and abstracts applying the inclusion criteria. We retrieved the full text of all potentially relevant studies. Where there was any doubt about a study's eligibility, a third review author assessed its eligibility. We resolved disagreements by consensus. Studies that were excluded after scrutiny are documented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (GF, EP, or MAOB) independently extracted data from each included study, and results for the longest follow‐up, into a modified data extraction form (EPOC 2017). We reconciled data and resolved any disagreements by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GF, EP, or MAOB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and three additional criteria specified by EPOC (EPOC 2016).

The criteria included:

Random sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Similarity of baseline outcome measurements;

Similarity of baseline characteristics (for providers and patients);

Blinding;

Incomplete outcome data;

Protection against contamination;

Selective outcome reporting;

Other risks of bias.

Studies that used cluster randomisation were scored as adequate for the protection against contamination and on concealment of allocation (if the randomisation sequence generation was adequate). We assessed the overall risk of bias (high, moderate or low) of each included study using the approach suggested in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). Studies achieved an overall 'low' risk of bias score if all key domains were judged as 'adequate' or when it seemed unlikely that bias would seriously alter the results. A score of overall moderate risk of bias was given to studies that scored unclear on at least one domain or when judged to have some bias that possibly could raise doubts about the conclusions. Studies that scored high risk in at least one domain or were judged to have serious concerns that questioned the certainty of the conclusions were assigned as having an overall high risk of bias. We updated studies included in the previous review using this approach. We resolved disagreements by consensus. No studies were excluded because of poor methodological quality. We compared results between studies considered as having 'low risk' of bias with studies judged to be at either 'moderate' or 'high' risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated the adjusted risk differences (RD) for dichotomous compliance outcomes, and expressed all outcomes as compliance with evidence‐based practice, that is, improved compliance was always represented by higher proportions, even if a reduction in behaviour was desired (for example, if the targeted clinical behaviour was to reduce the number of episiotomies, this was expressed as the number of women not receiving an episiotomy and for which an increase was desired). An adjusted risk difference is the difference between intervention and control group means of compliance after ('post') the intervention minus the difference between groups before ('pre') the intervention which may be expressed as:

Adjusted risk difference (RD) = (risk of compliance (intervention ‐ control) post‐intervention) ‐ (risk of compliance (intervention ‐ control) pre‐intervention)

A positive adjusted RD indicates that compliance improved more in the opinion leader intervention group that in the control group. Therefore, a positive adjusted RD (e.g. of + 0.12) indicates an absolute improvement in compliance with evidence‐based practice (of 12%) whilst a negative adjusted RD represents decreased compliance.

For continuous outcomes, we reported means and standard deviations in additional tables and in the text, but these data were not included in the primary analyses. When necessary, results were approximated from graphical representations of results.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We assessed whether analyses of studies using cluster randomisation had taken into account the design effect, as not taking into account the effect of clustering risk inflates the type 1 error‐rate and results in artificially narrow confidence intervals. For cluster‐randomised trials not accounting for the design effect, we did not report P values or confidence intervals . We did not adjust the results as with no meta‐analysis, this was not needed. We noted in text and tables which studies had a unit of analysis error.

Studies with more than two arms

If more than one comparison from multi‐arm studies (i.e. studies with more than two arms) were eligible for the same comparison, we did as follows: for dichotomous compliance outcomes, we divided the number of events and participants as equally as possible between the shared arms. We did not provide a summary estimate of the effect for the continuous outcomes, but reported the results from each study separately. We did not divide the number of participants between shared arms, as suggested in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors if primary outcomes data were missing or reported in a way that prevented them being included in the median adjusted RD calculations. We did not impute data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We made no statistical assessment of heterogeneity as meta‐analyses were not feasible.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not attempt to assess reporting biases through examinations of funnel plots as no meta‐analyses were conducted.

Data synthesis

As expected, meta‐analysis was not feasible, since the included studies were too heterogenous in terms of populations (patients and healthcare professionals), settings, targeted clinical behaviours, and characteristics of the interventions. We chose to report the improvement in compliance with evidence‐based practice using the median adjusted risk difference (ARD), with interquartile range (IQR). This method was developed by Grimshaw 2004, and has since been used in a number of systematic reviews (for example, Ivers 2012; Shojania 2009). It should be noted that this method uses the 'median' in two different ways. If a single primary outcome measure was specified by the authors, we calculated the adjusted RD for that outcome measure only. However, If more than one primary outcome was reported in a study, or if a primary outcome measure was not specified among a number of outcomes reported by the authors, we calculated an adjusted RD for each outcome measure reported, and extracted the median value across outcomes for each study. In the result tables, we tabulated the median adjusted RD for studies that reported an odd number of primary outcomes. For studies that reported an even number of outcomes, we averaged the risk difference for the two middlemost to produce the median study adjusted RD. We then extracted the single median value from each study and calculated the median (and IQR) across studies for the compliance outcomes and for each comparison. For outcomes that lacked baseline outcome measures, we calculated the unadjusted risk difference. For dichotomous patient outcomes, we calculated the adjusted RD. For continuous patient outcomes, we reported the adjusted mean difference in the text. When there was additional outcome information that could not be incorporated into the median adjusted RD calculations, we noted this in the text, and stated if the additional result data supported or contradicted the information from the median ARD calculations.

Summary of findings

Two review authors (GMF, EP or MAOB) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low) using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations/risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias; Guyatt 2008), for the following outcomes in order to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review: compliance with evidence‐based practice, patient outcomes, and costs. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2016). We resolved disagreements on certainty of ratings by discussion. We provided justification for decisions to down‐ or up‐grade the ratings using footnotes in the table and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review, where necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not conduct subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with a high or moderate overall risk of bias. We also investigated whether excluding studies with unadjusted outcomes (with no baseline measure of outcomes) would change the results, as it has been suggested by others that cluster‐randomised trials may suffer from large baseline differences (Ivers 2012). None of these analyses showed any differences in the median effect between groups.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See Figure 1. We screened 3671 citations, and retrieved and reviewed 45 possibly eligible studies in full text. We listed six studies under ongoing studies (Alsweiler 2017; Bosch 2014; ISRCTN50041378; Johnson 2006; McKenzie 2013; Tello‐Bernabe 2011). We found six new studies which met our inclusion criteria (Johnston 2007; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Simunovic 2010). We had previously excluded four of these studies but now judged them to be eligible, due to our expanded inclusion criteria (Johnston 2007; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Schectman 2003). We included 24 randomised studies in the review.

Included studies

For details see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design and setting

All included studies were randomised trials, of which a majority were cluster‐randomised trials.

Twelve of the 24 studies were based in the United States, eight in Canada, one in Australia, the UK, and Hong Kong respectively, and one in Argentina and Uruguay. No studies were from low‐ or middle income countries. The setting of the interventions were as follows: hospitals (17 studies), primary care practices (3 studies; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Schectman 2003), and physiotherapy clinics (one study; Rebbeck 2006). One study involved both primary and secondary care (Elliott 1997). In two studies, the setting was unclear (Cabana 2006; Majumdar 2007).

Sample sizes

The number of hospitals randomised in the included studies ranged from 6 to 37 (median: 17), and the number of communities or regions randomised ranged from 6 to 10. Among the studies that randomised healthcare professionals, the number of these professionals ranged from 52 to 272. One study randomised 252 primary care practices, and one study randomised six wards at one hospital.

Participants

When reported, the total number of healthcare professionals in the included studies was 3005 (median: 103; range 6 to 769). Four studies did not report the number of healthcare professionals. The type of healthcare professionals targeted by the intervention were as follows: physicians (16 studies), nurses (3 studies), physiotherapists (one study), and four studies targeted a combination of healthcare professionals. In all but one study (Rycroft‐Malone 2012), OLs delivered educational initiatives to members of their own healthcare profession.

A total of 29,167 patients (median: 728; range 103 to 6798) were recruited in the included studies. The type of patients varied widely and constituted: mothers with their newborns receiving pre and postnatal care, people with chronic respiratory conditions (asthma, COPD), people with cardiovascular conditions (unstable angina, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction), people with diabetes, with cancer, with conditions of the bone, joints and surrounding tissue (osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis), with traumatic or idiopathic musculoskeletal pain (whiplash, acute low‐back pain), and people receiving pre or postoperative care.

Interventions

Methods used to identify OLs

In 14 studies, OLs were identified using the sociometric method in which healthcare professionals were asked to complete a self‐administered questionnaire to identify educationally influential colleagues (Hiss 1978; Rogers 1995). Response rates varied between 30% to 67% (7 studies). Eight studies used methods equivalent to the informant method (Hong 1990; Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Simunovic 2010). Two studies (Cabana 2006; Sisk 2004) described two methods of identification: in Sisk 2004, the informant method and the sociometric method (Coleman 1966) were used, and in Cabana 2006, the informant and the self‐designating method. We found no studies using other methods of identifying OLs than the four previously predefined methods (Valente 2007). The four previously excluded studies did not explicitly state what methods they had used, however based on their description we classified them as using the informant method.

Targeted behaviours

Targeted behaviours involved the general management of various clinical condition and evidence‐based practices: increased use of prophylactic oxytocin and decreased use of episiotomy in vaginal deliveries (Althabe 2008); decreased use of epidural anaesthesia (Hodnett 1996); increased rates of trial of labour and vaginal birth (Lomas 1991); guideline consistent care of people with unstable angina (Berner 2003); improved care of people with asthma (Cabana 2006); improved cancer pain management (Elliott 1997); discussing treatment options for early breast cancer (Guadagnoli 2000); improved urinary catheter care (Hong 1990); improved paediatric pain management (Johnston 2007); provision of antenatal corticosteroids for foetal maturation (Leviton 1999); statin management in coronary heart disease (McAlister 2009); appropriate medication for heart failure and Ischaemic heart disease (Majumdar 2007); improved osteoporosis care (Majumdar 2008); improved diabetes safety and care (O'Connor 2009); guideline‐consistent care of people with whiplash (Rebbeck 2006); improving perioperative fluid‐fast times (Rycroft‐Malone 2012); appropriate care of people with acute low‐back pain (Schectman 2003); improved rectal cancer surgical treatment (Simunovic 2010); increased breastfeeding rate (Sisk 2004); improved care of people post‐myocardial infarction (Soumerai 1998); improved care for people with rheumatoid arthritis (Stross 1980); improved care for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Stross 1983); improved care for people with osteoarthritis (Stross 1985); improved colon cancer staging (Wright 2008).

Characteristics of the interventions

OLs was the only intervention in five studies (Hong 1990; Lomas 1991; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985). In 19 studies, OLs were supplemented by other interventions such as audit and feedback, chart reminders, faxed evidence summaries, educational materials, seminars, learning cases, web resources, one‐to‐one coaching, workshops and lectures. The median duration of the Interventions was seven months (range: one week (Cabana 2006) to 18 months (Althabe 2008)). The median duration of follow‐up was 12 months (range 2 to 30 months).

The OLs in the included studies used both formal (e.g. educational meetings, group tutorials, conferences, grand rounds) and informal methods of educating their peers (e.g. one‐to‐one teaching), which typically took place face‐to‐face. In four of the included studies, there was no face‐to‐face interaction; instead OL‐endorsed evidence summaries were faxed to the patients clinician (Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009), or the interaction was web‐based (Rycroft‐Malone 2012). In one study, the role of the OL was described as 'being a support person' which required encouragement of their peers to take part in demonstrations. In many cases, however, the methods used by the OLs were not clear. The frequency with which OLs engaged with the target professionals was clearly described in six studies (Cabana 2006; Johnston 2007; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Schectman 2003; Sisk 2004), and two more attempted a description (Hodnett 1996; Lomas 1991), while no description was provided in the remaining 16 studies.

In eight studies, teams of OLs were used (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Elliott 1997; Hong 1990; Leviton 1999; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; Stross 1980), of which four were multidisciplinary (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Leviton 1999; Majumdar 2007), and in one study identification of more than one OL was permitted (Rycroft‐Malone 2012) .

Comparisons

The comparisons were as follows: OLs alone versus no intervention (5 studies); OLs alone versus a single intervention (2 studies); OLs with a single or more other intervention(s) versus the same single or more intervention(s) (5 studies); and OLs with a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention (10 studies).

Outcomes

The type of compliance outcomes varied greatly across studies, as did the type of patient outcomes. Eighteen of the 24 included studies reported compliance outcomes: 10 studies reported outcomes involving prescribing practices; five studies reported outcomes related to test ordering; documentation and referrals; and 12 studies reported on compliance with a number of miscellaneous evidence‐based practices. Three studies reported five dichotomous patient outcomes, and five studies reported eight continuous patient outcomes. None of the included studies reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Nine of 24 studies reported having conducted a sample size calculation (Althabe 2008; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Simunovic 2010; Wright 2008).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies

We excluded 69 studies with reasons, such as ineligible intervention (e.g. not OLs) (17 studies), ineligible study design (not randomised: 11 studies), or ineligible (nonobjective) outcomes (three studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

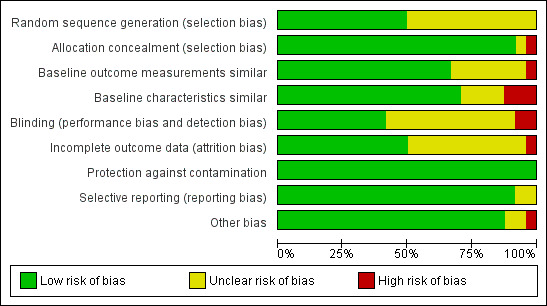

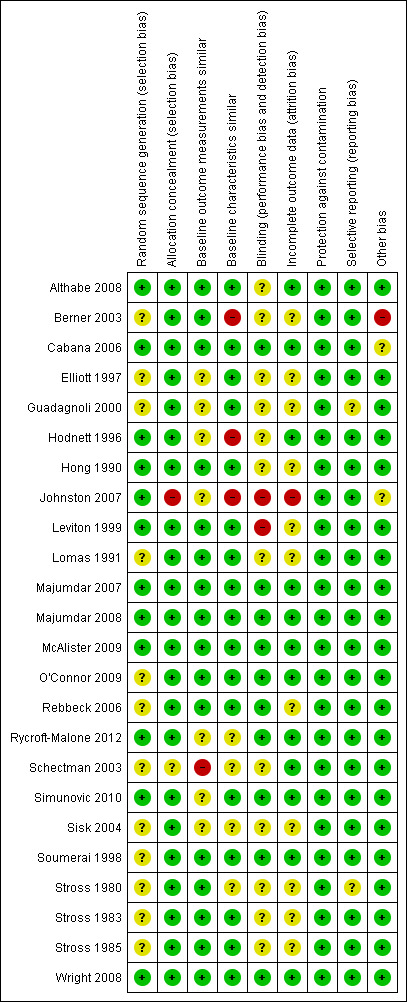

See Figure 2, Figure 3 and the risk of bias tables within the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Nine studies (38%) were judged to have an overall high risk of bias (Berner 2003; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Johnston 2007; Schectman 2003; Sisk 2004; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985), four (17%) to be at overall moderate risk of bias (Hodnett 1996; Leviton 1999; Lomas 1991; Rebbeck 2006) and eleven studies (46%) were assigned an overall low risk of bias (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Hong 1990; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Soumerai 1998; Wright 2008).

Random sequence generation

Twelve studies reported adequate sequence generation in the randomisation process (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Hodnett 1996; Hong 1990; Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999; Majumdar 2008; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Wright 2008). The sequence generation was unclear in the remaining 12 studies (Berner 2003; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2007; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Sisk 2004; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985).

Similarity of baseline outcome measures

Fifteen of the included studies had similar baseline outcome measures (Althabe 2008; Berner 2003; Cabana 2006; Hong 1990; Leviton 1999; Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985). In one study (Wright 2008), baseline differences were adjusted for in the analysis. In seven studies, it was not clear if the baseline outcomes were similar (Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Hodnett 1996; Johnston 2007; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Sisk 2004). One study was at high risk due to differences in baseline outcome measures (Schectman 2003) .

In one study (Berner 2003), less than half of eligible hospitals agreed to participate, creating a potential risk of self‐selection bias as the hospitals that declined to participate were different from the others. In two studies (Cabana 2006,Johnston 2007), a low proportion of eligible providers agreed to participate: 8% and 30% respectively, and it was unclear if those who agreed to participate were different from those who declined. This may affect the generalisability of the results.

Similarity of baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics were similar in 15 of the included studies (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Hong 1990; Leviton 1999; Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2007; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1983; Stross 1985; Wright 2008). In three studies (Berner 2003; Hodnett 1996; Johnston 2007), the baseline characteristics were significantly different between intervention and control group. In one of the studies (Johnston 2007), the number of nurses who agreed to participate differed between sites (range 17% to 68%). In one study (Majumdar 2008), baseline differences were adjusted for in the analysis. In four studies (Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Sisk 2004; Stross 1980), the risk of bias was unclear as no baseline characteristics were reported.

Allocation

The concealment of allocation was adequate in all but two studies (Johnston 2007; Schectman 2003). It was unclear in one of the studies (Schectman 2003). In one study, the allocation was not concealed as randomisation was by a coin toss (Johnston 2007).

Blinding

Ten studies were at low risk of bias either because patient, healthcare professionals and outcome assessors were all blinded, or the patient/healthcare professional were blinded and it was stated that the outcomes were objective and/or retrieved from registers (Cabana 2006; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Soumerai 1998; Wright 2008). In 12 studies, it was not clear whether or not the patients, the healthcare professionals or the outcome assessor were blinded (Althabe 2008; Berner 2003; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Hodnett 1996; Hong 1990; Lomas 1991; Schectman 2003; Sisk 2004; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985). In two studies (Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999), the risk of performance (and detection) bias was high due to non‐blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were either complete or incomplete data adequately addressed in 12 studies (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Hodnett 1996; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Simunovic 2010; Soumerai 1998; Wright 2008), but for the remaining studies it was unclear whether the outcome data were complete or adequately addressed, or both. One study (Johnston 2007) suffered from a large variation in attrition rate between sites.

Protection against contamination

All studies were protected against contamination.

Selective reporting

All but two of the included studies were free from selective reporting. In these studies (Guadagnoli 2000; Stross 1980), it was not clear if the reporting of outcomes was selective, as the outcomes of interest were not listed in the methods section.

Other potential sources of bias

In 19 studies, the results were appropriately analysed at the cluster level or by considering the intra‐cluster correlation when the analysis was conducted using data from individual patients. Five studies had unit of analysis errors (Hong 1990; Lomas 1991; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

for the main comparison.

| Local opinion leaders alone or with one or more other intervention(s) compared with no intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more intervention(s) | |||

|

Population: Healthcare professionals (e.g. primary care physicians, surgeons, obstetricians, birth attendants, nurses) Setting: Primary and secondary care Countries: USA, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Argentina and Uruguay Intervention: Local OLs alone, or with one or more other intervention(s) Comparison: No intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more other intervention(s) | |||

| Outcomes |

Compliance outcomes: Adjusted absolute improvement (Risk difference)* Median (Interquartile range) |

No of Studies (no of healthcare professionals/ no of sites) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Compliance with evidence‐based practice* | 10.8% (3.5% to 14.6%) absolute improvement in compliance |

18 randomised studies (2216 healthcare professionals; 249 hospitals, 284 practices) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖a MODERATE |

| Patient (dichotomous) outcomes (including adverse events) |

It is uncertain whether OLs (alone, or with one or more other interventions), improve patient outcomes (postpartum haemorrhage rate, local cancer reoccurrence, permanent colostomy rate, and breastfeeding rate). |

3 studies (370 health care professionals; 53 hospitals) |

⊕⊖⊖⊖b,c VERY LOW |

| Costs | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| *The post‐intervention risk differences were adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups, where pre values were available. Five out of six (unadjusted) studies, that did not report a baseline measure of outcome, stated that there were no baseline differences across groups. aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to high risk of bias (a majority of studies had high or moderate risk of bias), bWe downgraded the certainty of evidence two steps due to indirectness (all three studies compared a multifaceted OL intervention with no intervention, which makes it difficult to separate out the effect of the OLs per se. Also one study evaluated surrogate outcomes i.e. breastfeeding rate instead of infant health outcomes). cWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participating healthcare professionals, the effect varying across studies from a beneficial effect in one, to little or no effect in the other two, and, in addition, the types of outcomes that were assessed varied across studies). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

*Eighteen of the 24 included studies (21 comparisons; 71 outcomes) contributed to the calculation of the median adjusted risk difference (RD) for the main comparison.

The remaining six studies did not provide data that could be included in the adjusted RD calculations. Three of the 24 included studies reported in total 5 dichotomous patient outcomes.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings for secondary comparison 1.

| Local opinion leaders alone compared with no intervention | |||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals (nurses, primary care physicians) Setting: Primary and secondary care Country: USA and Canada Intervention: Local OLs Comparison: No intervention | |||

| Outcomes |

Adjusted absolute improvement (Risk difference)* Median (Interquartile range) |

No of Studies (no of healthcare professionals/ no of sites) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Compliance with evidence‐based practice* | 9.15% (‐0.3% to 15%) absolute improvement in compliance |

5 randomised studies (769 primary care physicians, 28 groups/clusters of physicians, 20 groups of nurses, 48 hospitals and one large health system) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖a MODERATE |

| Patient (dichotomous) outcomes (including adverse events) |

Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| Costs | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| *The post‐intervention risk differences were adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups, where pre values were available. aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to high risk of bias (three studies were at high risk of bias and one at moderate risk). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

*Five of the 24 included studies (5 comparisons; 37 dichotomous outcomes) contributed to the calculation of the median adjusted risk difference (RD).

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings for secondary comparison 2.

| Local opinion leaders alone compared with a single intervention | |||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals (nurses, physicians including obstetricians) Setting: Secondary care Country: Hong Kong and Canada Intervention: Local OLs Comparison: A single other intervention | |||

| Outcomes |

Adjusted absolute improvement (Risk difference)* Median (interquartile range) |

No of Studies (no of healthcare professionals/ no of sites) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Compliance with evidence‐based practice* | 13.8% (12% to 15.5%) absolute improvement in compliance |

2 randomised studies (147 nurses, 76 physicians, 16 hospitals, and 6 wards at one hospital) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖a MODERATE |

| Patient (dichotomous) outcomes (including adverse events) |

Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| Costs | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| *The post‐intervention risk differences were adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups, where pre values were available. aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to imprecision (fewer than 400 healthcare professionals received the intervention). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

*Two of the 24 included studies (2 comparisons; 3 dichotomous outcomes) contributed to the calculation of the median RD.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings for secondary comparison 3.

| Local opinion leaders with a single or more other intervention(s) compared with the same single or more intervention(s) | |||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals (nurses, physicians including surgeons) Setting: Primary and secondary care Contry: USA, Canada and Hong Kong Intervention: Local OLs with one or more other intervention(s) Comparison: The same one or more other intervention(s) | |||

| Outcomes |

Adjusted absolute improvement (Risk difference)* Median (Interquartile range) |

No of Studies (no of healthcare professionals/no of sites) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Compliance with evidence‐based practice* | 7.1% (‐1.4% to 19%) absolute improvement in compliance |

5 randomised studies (618 physicians/surgeons, 220 nurses, 66 hospitals, 18 primary care clinics in one health system) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖a MODERATE |

| Patient (dichotomous) outcomes | Intervention may lead to little or no difference in HbA1c and LDL levels. |

1 randomised study (38 physicians; 18 clinics ‐ medical groups) |

⊕⊕⊖⊖b,c LOW |

| Costs | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| *The post‐intervention risk differences were adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups, where pre values were available. aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to high risk of bias (two of five studies had high risk of bias). bWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to imprecision (fewer than 400 healthcare professionals receiving the intervention). cWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to indirectness (surrogate outcomes, i.e. HbA1c and LDL levels instead of patient‐important outcomes like diabetes symptoms or QOL). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

*Five of the 24 included studies (five comparisons; 12 dichotomous outcomes) contributed to the calculation of the median adjusted risk difference (RD).

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings for secondary comparison 4.

| Local opinion leaders plus a single or more intervention(s) compared with no intervention | |||

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals Setting: Primary and secondary care Country: Canada, USA, Argentina and Uruguay Intervention: Local OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) Comparison: No intervention | |||

| Outcomes |

Adjusted absolute improvement (Risk difference)* Median (Interquartile range) |

No of Studies (no of sites) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Compliance with evidence‐based practice* | 10.25% (0.6% to 15.75%) absolute improvement in compliance |

10 randomised trials (136 hospitals; 284 primary care practices; two EDs and two fracture clinics) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖a MODERATE |

| Patient (dichotomous) outcomes | It is uncertain if OLs with a single or more intervention(s), improve patient outcomes (postpartum haemorrhage rate, local cancer reoccurrence, permanent colostomy rate, and breastfeeding rate). |

3 studies (370 healthcare professionals; 53 hospitals) |

⊕⊖⊖⊖b,c VERY LOW |

| Costs | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ |

| *The post‐intervention risk differences were adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups, where pre values were available.

aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to indirectness (the OL intervention was one of multiple interventions) bWe downgraded the certainty of evidence one step due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participating healthcare professionals, the effect varying across studies from a beneficial effect in one, to little or no effect in the other two, and, in addition, varying types of outcomes were reported). cWe downgraded the certainty of evidence two steps due to indirectness (all three studies compared OLs with one or more intervention(s) with no intervention, which makes it difficult to separate out the effect of the OLs per se. Also, one study evaluated a surrogate outcome i.e. breastfeeding rate instead of infant health outcomes). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

*Ten of the 24 included studies (10 comparisons; 20 dichotomous outcomes) contributed to the calculation of the median adjusted risk difference (RD). The same three trials as in the main comparison reported five dichotomous patient outcomes.

Comparison 1. Effects of local OLs alone, or plus a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more intervention(s)(main comparison)

For a summary of the evidence, see Table 1. For detailed results, see Appendix 3, Appendix 4, Appendix 5, and Appendix 6. For the evidence profiles, see Appendix 7.

i) Compliance with evidence‐based practice

There were 71 usable objective dichotomous outcomes from 18 studies (Althabe 2008,Berner 2003; Guadagnoli 2000; Hodnett 1996; Hong 1990,Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999,Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2007,Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Schectman 2003; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985; Wright 2008). Six studies did not contribute dichotomous outcomes to the median adjusted RD calculation (Cabana 2006,Elliott 1997,Rebbeck 2006; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Sisk 2004).

The studies involved in total more than 3005 healthcare professionals and 104 groups/clusters of healthcare professionals, 249 hospitals, 284 primary care practices, and more than 29,167 patient participants.

OLs alone, or plus a single or more intervention(s), as compared to no intervention, a single intervention, or the same single or more intervention(s), probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (median adjusted RD 10.8%, interquartile range (IQR) 3.5% to 14.6% absolute improvement in compliance in the intervention group; moderate‐certainty evidence).

ii) Patient outcomes

Eight studies, all of which evaluated OLs plus a single or more intervention(s), as compared to no intervention, reported 10 comparisons, five dichotomous outcomes and eight continuous patient outcomes.

Dichotomous patient outcomes

Three studies reported five dichotomous patient outcomes. One study reported that using OLs may lead to less postpartum haemorrhage for women receiving obstetric care (relative rate reduction > 500 mL: 45%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 9% to 71%; > 1000 mL: 70%; 95% CI, 16% to 78%; Althabe 2008). One study reported that OLs may lead to little or no difference in local cancer reoccurrence (RD 0.1%) and in permanent colostomy rate (RD ‐1.4%) for people with colon cancer (Simunovic 2010). One study reported similar breastfeeding rates across groups (Sisk 2004). We are however uncertain if OLs alone, or with a single or more intervention(s), may lead to improved patient (dichotomous) outcomes since the certainty of evidence was very low.

Continuous patient outcomes

Five studies reported eight continuous outcomes: one study reported slightly fewer parent‐reported emergency department visits for children with asthma who received care from intervention group physicians (adjusted mean difference (MD): ‐0.25 visits per year; P < 0.05), and similar number of admissions to hospital and urgent office visits (P > 0.05). Six percent of the parent‐reported data were checked against registers for accuracy (Cabana 2006). One study reported similar pain scores for people with cancer in intervention and control groups (adjusted MD: +0.86 scale steps; P = 0.66) (Elliott 1997). One study reported similar glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) levels for people with diabetes in the intervention group (adjusted MD: +0.123 units greater increase in HbA1c, P > 0.05; and 0.4 units lower decrease in LDL level, P > 0.05) (O'Connor 2009). One study reported similar functional rating scores for people with whiplash who received care from intervention physicians as for those receiving care from control physicians (MD: ‐0.6 score, 95% CI:‐7.8 to 6.6; P = 0.87) (Rebbeck 2006), and one study reported similar fluid fast time for surgical patients in intervention (OLs + web‐based intervention) and control groups (0.33, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 1.12; P > 0.05) (Rycroft‐Malone 2012). We are uncertain if OLs alone, or with a single or more intervention(s), may improve patient (continuous) outcomes (5 studies; very low‐certainty of evidence).

iii) Costs

We did not find studies that reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Comparison 2. Effects of local OLs alone versus no intervention

See Table 2, and Appendix 3.

i) Compliance with evidence‐based practice

Five studies reported 37 dichotomous outcomes (and one continuous outcome) for this comparison (Hodnett 1996; Majumdar 2007; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985).

The studies involved in total 48 hospitals, one large health system, and more than 884 patient participants. The healthcare professionals targeted by the intervention were nurses (Hodnett 1996) and primary care physicians (Majumdar 2007; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985). The number of participating healthcare professionals was unclear.

Hodnett 1996 reported one primary outcome: rates of epidural anaesthesia for women in labour. Majumdar 2007 assessed two primary outcomes: use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for people (N = 55) with heart failure (HF) and statins for people (N = 117) with Ischaemic coronary disease (ICD). Stross 1980 assessed 14 outcomes concerning care of people with rheumatoid arthritis (N = 114). Stross 1983 assessed 14 outcomes for care of people (N = 510) with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and Stross 1985 assessed six outcomes concerning care of people with osteoarthritis (N = 89). The duration of the interventions ranged from six to 18 months.

OLs alone, as compared to no intervention, probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (median adjusted RD (IQR): 9.15% (‐0.3% to 15% absolute improvement in the intervention group; moderate‐certainty evidence). Two of the five studies (Hodnett 1996,Majumdar 2007) did not report baseline measures of outcome, and the results were therefore not baseline‐adjusted. Majumdar 2007 reported that none of the participants were taking or had previously been taking the study medications (ARBs or ACEs), and there were no baseline differences for any other cardiovascular medication between groups.

ii) Patient outcomes

We did not find studies that reported on (primary) patient outcomes.

iii) Costs

We did not find studies that reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Comparison 3. Effects of Local OLs alone versus a single intervention

See Table 3 and Appendix 4.

i) Compliance with evidence‐based practice

Two studies reported three dichotomous outcomes for this comparison. The comparison interventions were standardised lectures (Hong 1990) and audit and feedback (Lomas 1991).

The studies involved in total 17 hospitals, 148 nurses and 76 physicians, with an unclear number of patients in one study (Hong 1990), while in the other, 3552 patient charts were reviewed (Lomas 1991).

OLs alone, as compared to a single intervention, probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (median RD (range): 13.75% (12% to 15.5%) absolute improvement in compliance in the intervention group; moderate‐certainty evidence). P values were not reported due to unit of analysis issues. Neither study reported a baseline measure of outcomes, and were therefore not baseline‐adjusted. Authors of both studies stated that the baseline outcome measures did not differ across groups.

ii) Patient outcomes

We did not find studies that reported on (primary) patient outcomes.

iii) Costs

We did not find studies that reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Comparison 4. Effects of local OLs with a single or more intervention(s) versus the same single or more intervention(s)

See Table 4 and Appendix 5.

i) Compliance with evidence‐based practice

Five studies reported 12 dichotomous outcomes for this comparison (and two continuous outcomes). The additional interventions included standardised lectures (Hong 1990), learning cases (O'Connor 2009) and, in three studies, audit and feedback (Berner 2003,Guadagnoli 2000; Soumerai 1998).

The studies involved in total 86 hospitals, 18 primary care clinics, 147 nurses, more than 57 physicians (three studies did not report the number of healthcare professionals), and 11,891 participating patients.

Berner 2003 reported five primary outcomes concerned with compliance with guidelines for unstable angina. O'Connor 2009 reported two primary outcomes concerned with diabetes care. Soumerai 1998 reported three outcomes concerned with care for people post‐acute myocardial infarction. Two of the studies reported only one primary outcome, discussion of breast cancer treatment options (Guadagnoli 2000), and correct urinary catheter practices (Hong 1990). The median duration of follow‐up was 12 months (range 2 to 12 months).

OLs, with one or more additional intervention, as compared to the same one or more additional interventions, probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (median adjusted RD (IQR) 7.1% (‐1.4% to 19%) absolute improvement in compliance in the intervention group; moderate‐certainty evidence). Two of the five studies were not adjusted for baseline differences (Berner 2003; Hong 1990).

ii) Patient outcomes

OLs with a single or more intervention(s), as compared with the same single or more intervention(s) may lead to little or no difference in the levels of HbA1c (MD: 0.19 units higher; P= 0.04) or LDL (MD: 1.3 units higher levels, P> 0.05) in people with diabetes (low‐certainty evidence) (O'Connor 2009).

iii) Costs

We did not find studies that reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Comparison 5. Effects of Local OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention

See Table 5 and Appendix 6.

i) Compliance with evidence‐based practice

Fifteen studies (Althabe 2008; Berner 2003,Cabana 2006; Elliott 1997; Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999; Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; O'Connor 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003; Simunovic 2010; Sisk 2004; Wright 2008) contributed 20 dichotomous outcomes for this comparison. One of the studies reported two dichotomous patient outcomes (Simunovic 2010), and four studies reported continuous patient outcomes (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Elliott 1997; Rycroft‐Malone 2012). One study provided no numerical data (Sisk 2004). Thus, ten studies contributed data to calculations of the median adjusted RD.

The studies involved in total 176 hospitals; 284 primary care practices; two emergency departments, two fracture clinics, more than 1895 healthcare professionals, and more than 19,914 patients.

Five of the studies assessed one primary outcome: antenatal corticosteroids for foetal maturation (Leviton 1999), bisphosphonate treatment for people with osteoporosis (Majumdar 2008), statin management for people with CHD (McAlister 2009), patient care compliant with low back guidelines (Schectman 2003), and lymph node assessment in stage II colon cancer (Wright 2008). Four studies reported two primary outcomes each: use of prophylactic oxytocin and use of episiotomy during third stage of labour (Althabe 2008), HbA1C and LDL test rate (O'Connor 2009), offer of trial of labour and vaginal birth (Lomas 1991), and permanent colostomy rate and local cancer reoccurrence (Simunovic 2010). One study reported three outcomes related to pain management (Johnston 2007), and one study contributed five primary outcomes related to unstable angina care to the analysis (Berner 2003). Three studies did not report any baseline measure of outcome, and were therefore not baseline‐adjusted (Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009). In one of those studies none of the participants received bisphosphonate treatment at baseline according to the authors (Majumdar 2008), and, in one study, the authors stated that the proportion of participants who received statins (and standardised statin dose) at baseline were similar across groups (McAlister 2009). The duration of follow‐up was a median of 12 months (range 6 to 24 months).

OLs, plus a single or more intervention(s), as compared to no intervention, probably improve healthcare professionals' compliance with evidence‐based practice (median adjusted RD (IQR): 10.25% (0.6% to 15.75%) absolute improvement in compliance in the intervention group; moderate‐certainty evidence).

ii) Patient outcomes

See patient outcomes under Comparison 1.

iii) Costs

We did not find studies that reported on costs or cost‐effectiveness.

Effects of local OLs identified by different methods

Fifteen of the included studies used the sociometric method (Althabe 2008; Berner 2003; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Hodnett 1996; Lomas 1991; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009; Simunovic 2010; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985,Wright 2008), and seven studies used methods equivalent to the informant method to identify OLs (Hong 1990; Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999; O'Connor 2009; Rebbeck 2006; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Schectman 2003). Two studies used a combination of two methods (Cabana 2006; Sisk 2004).

We reported the effect of OLs identified by different methods classified according to each of the four a priori group comparisons, as none of the new included studies used other methods to identify OLs.

i) OLs versus no intervention

All studies included used the sociometric method; the median adjusted RD was 9%.

ii) OLs versus a single intervention

Lomas 1991 used the sociometric method; the RD was 15%. Hong 1990 used the informant method; the RD was 12%.

iii) OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) versus the same one or more intervention(s)

Three studies used the sociometric method to identify OLs (Berner 2003; Guadagnoli 2000; Soumerai 1998).Two studies used the informant method (Hong 1990; O'Connor 2009). The effects of the three studies using the sociometric method varied from 7% to 13% (median adjusted RD: 7%). The RD for the compliance outcomes in the two studies using the informant method was 25% (Hong 1990), and 8% (O'Connor 2009).

iv) OLs plus a single or more intervention(s) versus no intervention

For the six studies which used the sociometric method to identify OLs, the median adjusted RD was 10% (Althabe 2008; Berner 2003; Elliott 1997, Majumdar 2008; McAlister 2009, Wright 2008). The median adjusted RD for the three studies that used the informant method was 11% (0.85% to 21%) (Johnston 2007; Leviton 1999; O'Connor 2009). The two remaining studies used the informant method (Sisk 2004) and the sociometric method (Coleman 1966). It was not possible to calculate a median RD for Sisk 2004 or for Cabana 2006 which used the informant and the self‐designating method.

Comparison across all studies irrespective of comparison

Overall, the absolute increase in evidence‐based practice (median adjusted RD) for studies using the sociometric method of identification was 10% and for the informant method was 11%.

Effects of method of delivering the opinion leader education and effect of frequency of opinion leader involvement

We intended to determine whether OLs were more or less effective depending on whether education was delivered formally or informally. Due to a limited amount of detail, most studies could not be reliably categorised according to the educational method OLs used. Too little detail was also provided on the frequency of involvement of OLs, to make further investigation feasible.

Effects of using a multidisciplinary opinion leader team versus a single opinion leader to deliver the intervention

Across outcomes for the three studies involving multidisciplinary OL teams, the median adjusted RD (IQR) was 11% (9.15% to 42.1%). Across outcomes for the 11 studies involving single OLs, the median adjusted RD (IQR) was 8.1% (‐0.75% to 13%).

Effects for studies considered as having low risk of bias versus studies judged to be at either moderate or high risk of bias

Across outcomes for studies judged to be at low risk of bias, the median adjusted RD (IQR) was 11.5% (0.85% to 14%) (Althabe 2008; Cabana 2006; Hong 1990; McAlister 2009; Majumdar 2007; Majumdar 2008; O'Connor 2009; Rycroft‐Malone 2012; Simunovic 2010; Soumerai 1998; Wright 2008). For the 13 studies judged to be of either moderate (Hodnett 1996; Leviton 1999; Lomas 1991; Rebbeck 2006) or high risk of bias (Berner 2003; Elliott 1997; Guadagnoli 2000; Lomas 1991; Sisk 2004; Soumerai 1998; Stross 1980; Stross 1983; Stross 1985), the median adjusted RD (IQR) was 11.0% (4.5% to 15.5%).

Certainty of the evidence

All included studies were randomised and were initially considered to have a high certainty of evidence (before assessment of quality). We downgraded the certainty of evidence for the main outcome (compliance with evidence‐based practice) from high to moderate certainty of evidence due to high risk of bias. We downgraded the dichotomous patient outcomes (postpartum haemorrhage rate, local cancer reoccurrence, permanent colostomy rate, and breastfeeding rate) one step due to indirectness, since all three studies compared a multifaceted OL intervention with no intervention, which makes it difficult to separate out the effect of the OLs per se. One study evaluated surrogate outcomes (i.e. breastfeeding rate instead of infant health outcomes). In addition, we downgraded the certainty of evidence two steps due to imprecision, because fewer than 400 healthcare professionals participated in the included studies and the intervention effect varied across studies (i.e. from a relatively large beneficial effect in one study, to little or no effect in the other two).

As for the dichotomous patient outcomes, we downgraded the certainty of evidence two steps due to indirectness (all three studies compared a multifaceted OL intervention with no intervention, which makes it difficult to separate out the effect of the OLs per se). Also one study evaluated surrogate outcomes (i.e. breastfeeding rate instead of infant health outcomes) and one step due to imprecision (fewer than 400 participating healthcare professionals, the effect varied across studies from a beneficial effect in one, to little or no effect in the other two, and in addition varying types of outcomes were assessed in the studies), i.e. from high to very low certainty of evidence.

Discussion

Summary of main results