This review covers advances made in genome mining SMs produced by Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus terreus in the past six years (2012–2018). Genetic identification and molecular characterization of SM biosynthetic gene clusters, along with proposed biosynthetic pathways, is discussed in depth.

This review covers advances made in genome mining SMs produced by Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus terreus in the past six years (2012–2018). Genetic identification and molecular characterization of SM biosynthetic gene clusters, along with proposed biosynthetic pathways, is discussed in depth.

Abstract

Secondary metabolites (SMs) produced by filamentous fungi possess diverse bioactivities that make them excellent drug candidates. Whole genome sequencing has revealed that fungi have the capacity to produce a far greater number of SMs than have been isolated, since many of the genes involved in SM biosynthesis are either silent or expressed at very low levels in standard laboratory conditions. There has been significant effort to activate SM biosynthetic genes and link them to their downstream products, as the SMs produced by these “cryptic” pathways offer a promising source for new drug discovery. Further, an understanding of the genes involved in SM biosynthesis facilitates product yield optimization of first-generation molecules and genetic engineering of second-generation analogs. This review covers advances made in genome mining SMs produced by Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus terreus in the past six years (2012–2018). Genetic identification and molecular characterization of SM biosynthetic gene clusters, along with proposed biosynthetic pathways, will be discussed in depth.

1. Introduction

Filamentous fungi, including those within the Aspergillus genus, are known to produce a vast array of secondary metabolites (SMs) that exhibit a broad range of biological activities. SMs are organic small molecules that confer selective advantage to the organism despite not being directly required for survival. In nature, SMs function as weapons to eliminate neighboring competition, chemical signals in microbial cell communication, agents of symbiosis and transportation, sexual hormones, or differentiation effectors.1 However, SMs also possess various characteristics that make them great drug candidates, which has resulted in their extensive use in the pharmaceutical industry. For example, they exhibit enormous structural and chemical diversity due to the enzymatic nature of their biosynthesis, in which the core backbone of the SM is often biosynthesized by either a polyketide synthase (PKS), which can be either non-reducing (NR-PKS) or highly-reducing (HR-PKS), a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), a PKS–NRPS hybrid, a dimethylallyl tryptophan synthase (DMATS), or a terpene cyclase (TC). The carbon skeleton is then further diversified by various tailoring enzymes encoded by genes that are usually clustered in the genome with the SM core backbone gene.2 Tailoring enzymes may include oxidoreductases, oxygenases, dehydrogenases, reductases, and transferases. This process facilitates many reactions that are not possible synthetically and therefore SMs often feature more chiral centers and increased steric complexity than synthetic molecules. Further, because SMs have evolved within a biological setting, they usually possess many favorable drug-like properties. SMs currently represent a significant source of antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antiparasitic, anti-infective, anticancer, and antidiabetic drugs.3 Notable examples include the antibiotic penicillin, the cholesterol-lowering statin lovastatin, the antitumor agent paclitaxel,4 and the immunosuppressant cyclosporine.5 Additionally, the majority of small-molecule drugs introduced between 1981 and 2010 were either SMs, SM derivatives, SM mimics, or possessed a SM pharmacophore, and approximately 49% of all anticancer drugs are SMs or were inspired by SMs.3

Genome sequencing of Aspergillus species has greatly illuminated the potential for further drug discovery within the Aspergillus genus, revealing that the number of predicted SM biosynthetic genes or gene clusters considerably exceeds the number of identified SMs. A primary reason for this is that the majority of genes involved in SM biosynthesis are either silent or expressed at very low levels in standard laboratory conditions.6 This is a logical phenomenon given the natural functions of SMs, as laboratory culture conditions lack the life-threatening or competitive circumstances likely to trigger SM production. Expression of these genes sometimes requires exposure to a specific condition or stressful environment, and therefore culturing fungi in various conditions can result in the production of different SMs.7 Other times, genetic engineering techniques, such as heterologous expression or the use of inducible promoters, are required. Since the sequencing of the first Aspergillus genome in 2005,8 researchers have used bioinformatics to identify and characterize the SM biosynthetic gene clusters present in various species of Aspergillus.9 There have been considerable efforts to activate silent clusters and link them to their downstream products, as genome mining these “cryptic” pathways offer a promising source for new drug discovery.10 Further, linking known therapeutically-relevant SMs to their biosynthesis genes facilitates genetic manipulation efforts to optimize product yields of first-generation compounds and engineer second-generation compounds.

In 2012, a comprehensive review depicting the status Aspergillus SM research was published by J. F. Sanchez et al.11 Building on this previous work, this review examines advances made in Aspergillus SM genome mining efforts since 2012. Specifically, it focuses on progress made within the species of Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus terreus, which are distinguished for their significant use in research, medicine, and biotechnology. The well-characterized fungus A. nidulans has been extensively used as a model organism to study genetics and cell biology. Additionally, the development of A. nidulans “clean background” strains, which are lacking production of common SMs, combined with the availability of regulatable promoters and several genetic selection markers have facilitated its wide use as a heterologous expression host.12 The common airborne pathogen A. fumigatus threatens immunocompromised individuals and is responsible for most invasive aspergillosis infections, although infections can also be caused by A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger, and A. nidulans.13,14 Nevertheless, A. fumigatus is known to produce biologically useful SMs, including fumitremorgin C, which exhibits potent activity against the breast cancer resistance protein.15 Melanized A. niger is used extensively in the biotechnology industry for production of citric acid and enzymes.16 Additionally, it produces an array of therapeutically relevant SMs, including the antimicrobial aurasperone A,17 the antioxidant and antifungal aurasperone B,18 the human cancer cytotoxic agent bicoumanigrin A,19 and the antioxidant pyranonigrin A.20A. terreus is used for biotechnological production of the cholesterol-lowering drug lovastatin21,22 and the industrial polymer precursor itaconic acid.23,24

2. The status of genome mining Aspergillus secondary metabolites

The overall status of linking predicted SM core backbone synthase enzymes to their downstream products in A. nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. niger, and A. terreus is summarized in Table 1. Of the 66 predicted core synthase enzymes in the A. nidulans genome, 29 (43.9%) have been linked to downstream SM products. Similarly, of the 40 predicted SM core synthase enzyme-encoding genes in A. fumigatus, 19 (47.5%) have been linked to downstream SM products. While the A. niger and A. terreus genomes contains 99 and 74 predicted SM synthase enzymes, only 14 (14.1%) and 20 (27.0%) have been linked to their products, respectively. Tables 2–5 list the predicted SM core synthase genes and linked cluster products in A. nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. niger, and A. terreus, respectively. The following sections review the specific advances made in the genetic characterization and biosynthetic pathway elucidation of SMs produced by these four species in the past six years (2012–2018). It is important to note that the levels of details that have been clarified for these pathways varies quite significantly, as some pathways have been proposed with considerable detail while others involve sole characterization of the core synthase enzyme.

Table 1. The status of linking Aspergillus SM core synthase genes to downstream products.

|

Aspergillus nidulans

|

Aspergillus fumigatus

|

Aspergillus niger

|

Aspergillus terreus

|

|||||

| Linked | Total | Linked | Total | Linked | Total | Linked | Total | |

| PKS | 16 | 33 | 6 | 16 | 8 | 46 | 9 | 29 |

| NRPS | 11 | 25 | 9 | 18 | 4 | 35 | 9 | 36 |

| Hybrid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| DMATS | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| TC | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 29 | 66 | 19 | 40 | 14 | 99 | 20 | 74 |

Table 2. Core secondary metabolite synthesis genes and their products in A. nidulans.

| No. | Broad designation | Gene name | Gene type | SM(s) produced |

| 1 | AN0016 | pes1 | NRPS | |

| 2 | AN0150 | mdpG | NR-PKS | Monodictyphenone,84 emodin,143 xanthones,40 sanghaspirodins A and B144 |

| 3 | AN0523 | pkdA | NR-PKS | |

| 4 | AN0607 | sidC | NRPS | Ferricrocin145 |

| 5 | AN1034 | afoE | NR-PKS | Asperfuranone44 |

| 6 | AN1036 | afoG | HR-PKS | Asperfuranone44 |

| 7 | AN1242 | nlsA | NRPS | Nidulanin A58 |

| 8 | AN1594 | TC | ent-Pimara-8(14),15-diene25 | |

| 9 | AN1680 | NRPS-like | ||

| 10 | AN1784 | sdgA (pkjA) | HR-PKS | Asperniduglene A126 |

| 11 | AN2032 | pkhA | NR-PKS | |

| 12 | AN2035 | pkhB | HR-PKS | |

| 13 | AN2064 | NRPS-like | ||

| 14 | AN2545 | easA | NRPS | Emericellamides43 |

| 15 | AN2547 | easB | HR-PKS | Emericellamides43 |

| 16 | AN2621 | acvA | NRPS | Penicillin146 |

| 17 | AN2924 | NRPS-like | ||

| 18 | AN3230 | pkfA | NR-PKS | Aspernidine A28 |

| 19 | AN3273 | HR-PKS | ||

| 20 | AN3277 | TC | ||

| 21 | AN3386 | pkiA | NR-PKS | 6-Hydroxy-7-methyl-3-nonylisoquinoline-5,8-dione29 |

| 22 | AN3396 | micA | NRPS-like | Microperfuranone30 |

| 23 | AN3495 | inpA | NRPS | Fellutamide B37 |

| 24 | AN3496 | inpB | NRPS | Fellutamide B37 |

| 25 | AN3612 | HR-PKS | ||

| 26 | AN4827 | NRPS-like | ||

| 27 | AN5318 | NRPS-like | ||

| 28 | AN5475 | NR-PKS | ||

| 29 | AN6000 | aptA | NR-PKS | Asperthecin47 |

| 30 | AN6236 | sidD | NRPS | |

| 31 | AN6431 | HR-PKS | ||

| 32 | AN6448 | pkbA | NR-PKS | Cichorine,38 aspercryptin48 |

| 33 | AN6784 | xptA | DMAT | |

| 34 | AN6791 | HR-PKS | ||

| 35 | AN7071 | pkgA | NR-PKS | Alternariol, citreoisocoumarin and analogs29 |

| 36 | AN7084 | PKS-like | ||

| 37 | AN7489 | PKS-like | ||

| 38 | AN7825 | stcA (pksST) | NR-PKS | Sterigmatocystin147 |

| 39 | AN7880 | PKS-like | ||

| 40 | AN7884 | atnA | NRPS | Aspercryptin48 |

| 41 | AN7903 | dbaI (pkeA) | NR-PKS | Felinone A50 |

| 42 | AN7909 | orsA | NR-PKS | F9775 A and B,143 sanghaspirodins A and B144 |

| 43 | AN8105 | NRPS-like | ||

| 44 | AN8209 | wA | NR-PKS | YWA1, melanin148 |

| 45 | AN8383 | ausA | NR-PKS | Austinol, dehydroaustinol41 |

| 46 | AN8412 | apdA | Hybrid | Aspyridone A, B149 |

| 47 | AN8513 | tdiA | NRPS-like | Terrequinone A150 |

| 48 | AN8910 | HR-PKS | ||

| 49 | AN9005 | HR-PKS | ||

| 50 | AN9129 | NRPS-like | ||

| 51 | AN9226 | asqK | NRPS | 4′-Methoxyviridicatin55 |

| 52 | AN9243 | NRPS-like | ||

| 53 | AN9244 | NRPS | ||

| 54 | AN10289 | DMAT | ||

| 55 | AN10297 | NRPS-like | ||

| 56 | AN10430 | HR-PKS | ||

| 57 | AN10486 | NRPS-like | ||

| 58 | AN10576 | ivoA | NRPS | Grey-brown conidiophore pigment57,59 |

| 59 | AN11080 | DMAT | ||

| 60 | AN11191 | alnA | HR-PKS | (+)-Asperlin65 |

| 61 | AN11202 | DMAT | ||

| 62 | AN11820 | NRPS-like | ||

| 63 | AN12331 | PKS-like | ||

| 64 | AN12331 | PKS-like | ||

| 65 | AN12402 | xptB | DMAT | |

| 66 | AN12440 | NR-PKS |

Table 3. Core secondary metabolite synthesis genes and their products in A. fumigatus.

| No. | Af293 gene | A1163 gene | Gene name | Gene type | SM(s) produced |

| 1 | Afu1g01010 | No homolog | HR-PKS | ||

| 2 | Afu1g10380 | AFUB_009800 | pesB (pes1) | NRPS | Fumigaclavine C151 |

| 3 | Afu1g17200 | AFUB_016590 | sidC | NRPS | Ferricrocin, hydroxyferricrocin152,153 |

| 4 | Afu1g17740 | AFUB_045790 | Hybrid | ||

| 5 | Afu2g01290 | AFUB_018370 | HR-PKS | ||

| 6 | Afu2g05760 | AFUB_022790 | PKS-like | ||

| 7 | Afu2g17600 | AFUB_033290 | alb1 (pksP) | NR-PKS | YWA1, conidial pigment154 |

| 8 | Afu2g17990 | AFUB_033680 | fgaPT1 | DMAT | Fumigaclavine C155 |

| 9 | Afu3g01410 | AFUB_046990 | HR-PKS | ||

| 10 | Afu3g02530 | No homolog | PKS-like | ||

| 11 | Afu3g02570 | No homolog | NR-PKS | ||

| 12 | Afu3g02670 | AFUB_045610 | NRPS-like | ||

| 13 | Afu3g03350 | AFUB_044900 | sidE | NRPS | |

| 14 | Afu3g03420 | AFUB_044830 | sidD | NRPS | Fusarinine C, triacetylfusarinine C152,153 |

| 15 | Afu3g12920 | AFUB_036270 | hasD (pesF) | NRPS | Hexadehydroastechrome73 |

| 16 | Afu3g12930 | AFUB_036260 | hasE | DMAT | Hexadehydroastechrome73 |

| 17 | Afu3g13730 | AFUB_035460 | pesG | NRPS | |

| 18 | Afu3g14700 | AFUB_034520 | HR-PKS | ||

| 19 | Afu3g15270 | AFUB_033950 | pesH | NRPS | |

| 20 | Afu4g00210 | AFUB_100730 | encA | NR-PKS | Endocrocin81 |

| 21 | Afu4g14560 | AFUB_071800 a | tpcC | NR-PKS | Trypacidin, endocrocin82 |

| 22 | Afu4g14770 | AFUB_072030 | helA | TC | Helvolic acid100 |

| 23 | Afu5g10120 | AFUB_057720 | NRPS-like | ||

| 24 | Afu5g12730 | AFUB_060400 | pesI | NRPS | |

| 25 | Afu6g03480 | AFUB_094810 | fmpE | NRPS-like | Fumipyrrole103 |

| 26 | Afu6g08560 | AFUB_074520 | NRPS-like | ||

| 27 | Afu6g09610 | AFUB_075660 | pesJ | NRPS | |

| 28 | Afu6g09660 | AFUB_075710 | gliP | NRPS | Gliotoxin156 |

| 29 | Afu6g12050 | AFUB_078040 | fqzC (pesL) | NRPS | Fumigaclavine C,157 fumiquinazolines158 |

| 30 | Afu6g12080 | AFUB_078070 | NRPS | fumiquinazolines159 | |

| 31 | Afu6g13930 | AFUB_000820 | pyr2 | HR-PKS | Pyripyropene A160 |

| 32 | Afu7g00160 | AFUB_086700 | nscA (fccA) | NR-PKS | Neosartoricin,105 fumicyclines106 |

| 33 | Afu8g00170 | AFUB_086360 | ftmA | NRPS | Fumitremorgins161 |

| 34 | Afu8g00370 | AFUB_086200 | fma-PKS | HR-PKS | Fumagillin113 |

| 35 | Afu8g00540 | AFUB_086030 | psoA | Hybrid | Pseurotin A162 |

| 36 | Afu8g00620 | AFUB_085950 | cdpNPT | DMAT | |

| 37 | Afu8g01640 | AFUB_084950 | NRPS-like | ||

| 38 | Afu8g02350 | AFUB_084240 | NR-PKS | ||

| 39 | No homolog | AFUB_079710 | PKS | ||

| 40 | No homolog | AFUB_045640 | PKS |

aIndicates pseudogene.

Table 4. Core secondary metabolite synthesis genes and their products in A. niger.

| No. | CBS 513.88 gene | ATCC 1015 gene (FungiDB) | JGI v4 protein ID | Gene name | Gene type | SM(s) produced |

| 1 | An01g00060 | ASPNIDRAFT_55511 | 1083843 | PKS-like | ||

| 2 | An01g01130 | No homolog | No homolog | HR-PKS | ||

| 3 | An01g06930 | ASPNIDRAFT_225574 | 1162446 | fum1 | HR-PKS | Fumonisins163,164 |

| 4 | An01g06950 | ASPNIDRAFT_225587 | 1083446 | HR-PKS | ||

| 5 | An01g11770 | ASPNIDRAFT_170963 | 1082121 | NRPS-like | ||

| 6 | An02g00210 | N/A | 1121186 | NRPS-like | ||

| 7 | An02g00450 | ASPNIDRAFT_118617 | 1088618 | HR-PKS | ||

| 8 | An02g00840 | ASPNIDRAFT_36645 | 1184525 | NRPS-like | ||

| 9 | An02g05070 | ASPNIDRAFT_36929 | 1158197 | NRPS | ||

| 10 | An02g08290 | ASPNIDRAFT_118624 | 1122199 | Hybrid | ||

| 11 | An02g09430 | ASPNIDRAFT_37260 | 1135841 | HR-PKS | ||

| 12 | An02g10140 | ASPNIDRAFT_173610 | 1152150 | NRPS-like | ||

| 13 | An02g14220 | ASPNIDRAFT_55650 | 1165581 | PKS-like | ||

| 14 | An03g00650 | ASPNIDRAFT_128584 | 1166499 | NRPS | ||

| 15 | An03g01820 | N/A | 1109472 | NR-PKS | ||

| 16 | An03g03520 | ASPNIDRAFT_191228 | 1186498 | sidD | NRPS | Siderophore |

| 17 | An03g04890 | ASPNIDRAFT_191577 | 1186592 | TC | ||

| 18 | An03g05140 | ASPNIDRAFT_118598 | 1159456 | HR-PKS | ||

| 19 | An03g05440 | ASPNIDRAFT_191422 | 1153534 | NR-PKS | ||

| 20 | An03g05680 | ASPNIDRAFT_191357 | 1092575 | NRPS-like | ||

| 21 | An03g06010 | ASPNIDRAFT_44571 | 44571 | NRPS | ||

| 22 | An03g06380 | ASPNIDRAFT_191702 | 1125648 | HR-PKS | ||

| 23 | An04g01150 | ASPNIDRAFT_190264 | 1094020 | NRPS-like | ||

| 24 | An04g04340 | ASPNIDRAFT_44005 | 1126346 | HR-PKS | ||

| 25 | An04g04380 | ASPNIDRAFT_190891 | 1177621 | NRPS-like | ||

| 26 | An04g06260 | ASPNIDRAFT_118635 | 1177761 | NRPS | ||

| 27 | An04g09530 | ASPNIDRAFT_51499 | 1126849 | ktnS | NR-PKS | Kotanin114 |

| 28 | An04g10030 | ASPNIDRAFT_118662 | 1126920 | HR-PKS | ||

| 29 | An05g01060 | ASPNIDRAFT_118599 | 1102698 | NRPS | ||

| 30 | An06g00430 | ASPNIDRAFT_175936 | 1169209 | PKS-like | ||

| 31 | An06g01300 | ASPNIDRAFT_207636 | 1189171 | sidC | NRPS | Siderophore |

| 32 | An07g01030 | No homolog | 1151290 | NR-PKS | ||

| 33 | An07g02560 | ASPNIDRAFT_40106 | 1164213 | DMAT | ||

| 34 | An08g02310 | ASPNIDRAFT_52774 | 1168636 | NRPS | ||

| 35 | An08g03790 | ASPNIDRAFT_176722 | 1188722 | Hybrid | ||

| 36 | An08g04820 | ASPNIDRAFT_38316 | 1188789 | NRPS-like | ||

| 37 | An08g09220 | No homolog | No homolog | NRPS-like | ||

| 38 | An08g10830 | ASPNIDRAFT_120113 | 1130084 | TC | ||

| 39 | An08g10930 | ASPNIDRAFT_47227 | 1114420 | PKS-like | ||

| 40 | An09g00450 | ASPNIDRAFT_188738 | 1114543 | NRPS-like | ||

| 41 | An09g00520 | ASPNIDRAFT_43555 | 1114546 | NRPS | ||

| 42 | An09g01290 | ASPNIDRAFT_43495 | 1148587 | HR-PKS | ||

| 43 | An09g01690 | ASPNIDRAFT_212679 | 1079950 | NRPS | ||

| 44 | An09g01860 | ASPNIDRAFT_56946 | 1080089 | azaA | NR-PKS | Azanigerones117 |

| 45 | An09g01930 | ASPNIDRAFT_188817 | 1148627 | azaB | HR-PKS | Azanigerones117 |

| 46 | An09g02100 | No homolog | No homolog | PKS-like | ||

| 47 | An09g05110 | ASPNIDRAFT_129581 | 1114952 | NRPS-like | ||

| 48 | An09g05340 | ASPNIDRAFT_188697 | 188697 | HR-PKS | ||

| 49 | An09g05730 | ASPNIDRAFT_56896 | 1099425 | albA (fwnA) | NR-PKS | Naphtho-γ-pyrones, melanin165 |

| 50 | An09g06090 | ASPNIDRAFT_50045 | 50045 | TC | ||

| 51 | An10g00140 | ASPNIDRAFT_44965 | 1123159 | yanA | HR-PKS | Yanuthone D121 |

| 52 | An10g00630 | ASPNIDRAFT_45003 | 45003 | PKS-like | ||

| 53 | An11g00050 | ASPNIDRAFT_118659 | 1126949 | NRPS | ||

| 54 | An11g00250 | ASPNIDRAFT_179585 | 1111323 | pynA | Hybrid | Pyranonigrins E–J123,125 |

| 55 | An11g03920 | ASPNIDRAFT_179079 | 1095656 | HR-PKS | ||

| 56 | An11g04250 | ASPNIDRAFT_129526 | 1154309 | NRPS-like | ||

| 57 | An11g04280 | ASPNIDRAFT_39026 | 1223918 | HR-PKS | ||

| 58 | An11g05500 | ASPNIDRAFT_39114 | 39114 | NRPS-like | ||

| 59 | An11g05570 | ASPNIDRAFT_47991 | 1224252 | HR-PKS | ||

| 60 | An11g05940 | No homolog | No homolog | HR-PKS | ||

| 61 | An11g05960 | No homolog | No homolog | HR-PKS | ||

| 62 | An11g06260 | ASPNIDRAFT_39174 | 1154415 | TC | ||

| 63 | An11g06460 | ASPNIDRAFT_118644 | 1112058 | Hybrid | ||

| 64 | An11g07310 | N/A | 1112167 | adaA | NR-PKS | TAN-1612166 |

| 65 | An11g09720 | ASPNIDRAFT_118629 | 1167936 | HR-PKS | ||

| 66 | An12g02050 | ASPNIDRAFT_190014 | 1084740 | NR PKS | ||

| 67 | An12g02670 | ASPNIDRAFT_189378 | 1150307 | HR-PKS | ||

| 68 | An12g02730 | No homolog | No homolog | HR-PKS | ||

| 69 | An12g02840 | ASPNIDRAFT_43807 | 1172138 | NRPS | ||

| 70 | An12g07070 | ASPNIDRAFT_118666 | 1119191 | HR-PKS | ||

| 71 | An12g07230 | ASPNIDRAFT_42205 | 1103566 | NRPS | ||

| 72 | An12g10090 | ASPNIDRAFT_194895 | 1085888 | NRPS-like | ||

| 73 | An12g10670 | ASPNIDRAFT_45966 | 1085752 | TC | ||

| 74 | An12g10860 | ASPNIDRAFT_195043 | 1172993 | NRPS-like | ||

| 75 | An13g01840 | ASPNIDRAFT_123820 | 1161952 | DMAT | ||

| 76 | An13g02430 | ASPNIDRAFT_128638 | 1116441 | HR-PKS | ||

| 77 | An13g02460 | ASPNIDRAFT_57223 | 1156292 | NRPS-like | ||

| 78 | An13g02960 | No homolog | No homolog | NR-PKS | ||

| 79 | An13g03040 | ASPNIDRAFT_44880 | 1116473 | NRPS | ||

| 80 | An14g01910 | ASPNIDRAFT_41618 | 1099903 | Hybrid | ||

| 81 | An14g02060 | ASPNIDRAFT_41629 | 1155978 | TC | ||

| 82 | An14g04850 | ASPNIDRAFT_41846 | 1115863 | Hybrid | ||

| 83 | An15g02130 | ASPNIDRAFT_181803 | 1104204 | HR-PKS | ||

| 84 | An15g04140 | ASPNIDRAFT_210217 | 1119988 | HR-PKS | ||

| 85 | An15g05090 | ASPNIDRAFT_118744 | 1104411 | HR-PKS | ||

| 86 | An15g07530 | ASPNIDRAFT_182031 | 1164062 | NRPS | ||

| 87 | An15g07910 | No homolog | No homolog | NRPS | Ochratoxin164 | |

| 88 | An15g07920 | No homolog | No homolog | HR-PKS | Ochratoxin164 | |

| 89 | An16g00260 | ASPNIDRAFT_129626 | 1175966 | TC | ||

| 90 | An16g00600 | ASPNIDRAFT_183440 | 1123743 | NRPS-like | ||

| 91 | An16g06720 | ASPNIDRAFT_118601 | 1108909 | NRPS | Ferrichrome | |

| 92 | An18g00520 | ASPNIDRAFT_187099 | 1128344 | pyrA | Hybrid | Pyranonigrin A128 |

| 93 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_118581 | 1087173 | Hybrid | ||

| 94 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_128601 | 1170655 | Hybrid | ||

| 95 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_138585 | 1154267 | HR PKS | ||

| 96 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_171221 | 1156426 | PR PKS | ||

| 97 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_194381 | 1159236 | NR-PKS | ||

| 98 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_211885 | 1168194 | HR-PKS | ||

| 99 | No homolog | ASPNIDRAFT_55153 | 1186328 | NRPS |

Table 5. Core secondary metabolite synthesis genes and their products in A. terreus.

| No. | Broad designation | Gene name | Gene type | SM(s) produced |

| 1 | ATEG_00145 | terA | NR-PKS | Terrein131 |

| 2 | ATEG_00228 | NRPS | ||

| 3 | ATEG_00282 | HR-PKS | ||

| 4 | ATEG_00325 | Hybrid | Isoflavipucine167 | |

| 5 | ATEG_00700 | atqA | NRPS-like | Asterriquinones168 |

| 6 | ATEG_00881 | NRPS | ||

| 7 | ATEG_00913 | NR-PKS | ||

| 8 | ATEG_01002 | NRPS | ||

| 9 | ATEG_01052 | NRPS-like | ||

| 10 | ATEG_01730 | DMAT | ||

| 11 | ATEG_01769 | TC | ||

| 12 | ATEG_01894 | HR-PKS | ||

| 13 | ATEG_02004 | apvA | NRPS-like | Aspulvinones168 |

| 14 | ATEG_02403 | NRPS-like | ||

| 15 | ATEG_02434 | HR-PKS | ||

| 16 | ATEG_02815 | btyA | NRPS-like | Butyrolactones168 |

| 17 | ATEG_02831 | NRPS | ||

| 18 | ATEG_02944 | NRPS | ||

| 19 | ATEG_03090 | NRPS-like | ||

| 20 | ATEG_03432 | NR-PKS | ||

| 21 | ATEG_03446 | HR-PKS | ||

| 22 | ATEG_03470 | ataP | NRPS | Acetylaranotin133 |

| 23 | ATEG_03528 | NRPS | ||

| 24 | ATEG_03563 | atmelA | NRPS-like | Asp-melanin168,169 |

| 25 | ATEG_03576 | NRPS | ||

| 26 | ATEG_03629 | NR-PKS | ||

| 27 | ATEG_03630 | NRPS-like | ||

| 28 | ATEG_04218 | DMAT | ||

| 29 | ATEG_04322 | NRPS | ||

| 30 | ATEG_04323 | NRPS | ||

| 31 | ATEG_04416 | astA | TC | Aspterric acid134 |

| 32 | ATEG_04718 | HR-PKS | ||

| 33 | ATEG_04975 | NRPS-like | ||

| 34 | ATEG_04999 | DMAT | ||

| 35 | ATEG_05073 | NRPS | ||

| 36 | ATEG_05795 | NRPS-like | ||

| 37 | ATEG_06056 | HR-PKS | ||

| 38 | ATEG_06111 | DMAT | ||

| 39 | ATEG_06113 | NRPS | ||

| 40 | ATEG_06206 | NR-PKS | ||

| 41 | ATEG_06275 | atX | HR-PKS | Terreic acid132 |

| 42 | ATEG_06680 | HR-PKS | ||

| 43 | ATEG_06998 | NRPS-like | ||

| 44 | ATEG_07067 | HR-PKS | ||

| 45 | ATEG_07279 | HR-PKS | ||

| 46 | ATEG_07282 | HR-PKS | ||

| 47 | ATEG_07358 | NRPS | ||

| 48 | ATEG_07379 | HR-PKS | ||

| 49 | ATEG_07380 | NRPS-like | ||

| 50 | ATEG_07488 | NRPS | ||

| 51 | ATEG_07500 | HR-PKS | ||

| 52 | ATEG_07659 | AteafoG | HR-PKS | Asperfuranone12 |

| 53 | ATEG_07661 | AteafoE | NR-PKS | Asperfuranone12 |

| 54 | ATEG_07894 | NRPS-like | ||

| 55 | ATEG_08172 | HR-PKS | ||

| 56 | ATEG_08204 | TC | ||

| 57 | ATEG_08427 | NRPS | ||

| 58 | ATEG_08451 | gedC | NR-PKS | Geodin91,170 |

| 59 | ATEG_08662 | NR-PKS | ||

| 60 | ATEG_08678 | NRPS-like | ||

| 61 | ATEG_08899 | pgnA | NRPS-like | Phenguignardic acid136 |

| 62 | ATEG_09019 | NRPS | ||

| 63 | ATEG_09033 | NRPS-like | ||

| 64 | ATEG_09064 | apmB | NRPS | Asperphenamate140 |

| 65 | ATEG_09068 | apmA | NRPS | Asperphenamate140 |

| 66 | ATEG_09088 | HR-PKS | ||

| 67 | ATEG_09100 | HR-PKS | ||

| 68 | ATEG_09142 | NRPS-like | ||

| 69 | ATEG_09617 | ctvA | HR-PKS | Citreoviridin142 |

| 70 | ATEG_09961 | lovB | HR-PKS | Lovastatin171 |

| 71 | ATEG_09968 | lovF | HR-PKS | Lovastatin171 |

| 72 | ATEG_09980 | DMAT | ||

| 73 | ATEG_10080 | trt4 | NR-PKS | Terretonin130 |

| 74 | ATEG_10305 | anaPS | NRPS | Asterrelenin, epi-aszonalenin A168 |

3. Genetic characterization of secondary metabolites in Aspergillus nidulans

3.1. Biosynthesis of ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene

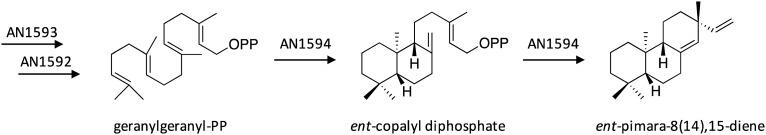

The silent SM gene cluster of the novel diterpene ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene was activated through overexpression of the Zn(ii)2Cys6 transcription factor PbcR present in the cluster.25 This led to high up-regulation of 7 adjacent genes encoding a diterpene synthase, a geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase, a HMG-CoA reductase, a translation elongation factor, a short-chain dehydrogenase, a hypothetical protein with partial similarity to methyltransferase, and a cytochrome P450, as well as the production of ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene. Based on this information, the biosynthesis of ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene was proposed to involve HMG-CoA reductase AN1593 to generate mevalonate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase AN1592 to generate geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (Scheme 1). Next, the diterpene synthase AN1594 was proposed to catalyze two cyclization reactions to generate ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene through a ent-copalyl diphosphate intermediate.

Scheme 1. Biosynthesis of ent-pimara-8(14),15-diene in A. nidulans.25.

3.2. Biosynthesis of asperniduglene A1

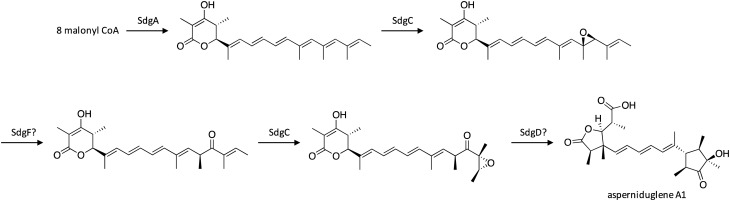

The asperniduglenes were discovered upon activation of the sdg gene cluster in A. nidulans, which harbors genes with similarity to the citreoviridin (ctv) gene cluster in A. terreus.26 Interestingly, despite the similarity of the cluster to the ctv cluster, the asperniduglenes fall into a different class of compounds than citreoviridin. The cluster was activated by replacing the promoters of genes within the sdg cluster with the inducible alcA promoter. Large-scale cultivation and examination of SMs and intermediates produced by mutant strains enabled the biosynthetic pathway of asperniduglene A1 to be proposed (Scheme 2). First, the polyketide product is biosynthesized by the HR-PKS SdgA, followed by epoxidation by SdgC, and subsequent ketone formation via Meinwald rearrangement, likely catalyzed by SdgF. Next, SdgC catalyzes a second epoxidation on the last olefin, followed by stereospecific cyclization and hydrolytic cleavage, both of which may be catalyzed by SdgD, to form asperniduglene A1.

Scheme 2. Biosynthesis of asperniduglene A1 in A. nidulans.26.

3.3. Biosynthesis of aspernidine A

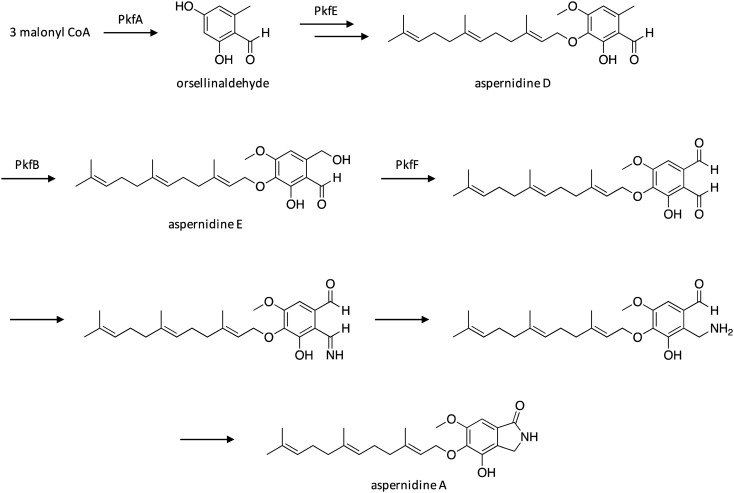

The biosynthetic gene cluster of aspernidine A, which has exhibited antiproliferative activity against tumor cell lines,27 was identified following construction of a genome-wide kinase knockout library in A. nidulans.28 Screening of the library, which consisted of 98 deletion strains, revealed that deficiency of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkA resulted in the production of aspernidines A and C. Structural analysis indicated that aspernidines A and C are likely derived from orsellinaldehyde, which suggested the involvement of the NR-PKS PkfA in their biosynthesis.29 Individual deletion of genes within the pkf cluster in the mpkA-genetic background strain resulted in the discovery of related compounds aspernidines D and E and allowed a biosynthetic pathway for aspernidine A to be partially proposed (Scheme 3). Following biosynthesis by PkfA, orsellinaldehyde undergoes O-methylation, hydroxylation, and prenylation to yield aspernidine D, which is likely catalyzed, in part, by the prenyltransferase PkfE. Aspernidine D is then hydroxylated by cytochrome P450 PkfB to form aspernidine E, which is oxidized by PkfF to generate a dialdehyde intermediate that is subsequently transformed to aspernidine A in a manner that has not been fully clarified yet.

Scheme 3. Biosynthesis of aspernidine A in A. nidulans.28.

3.4. Biosynthesis of microperfuranone

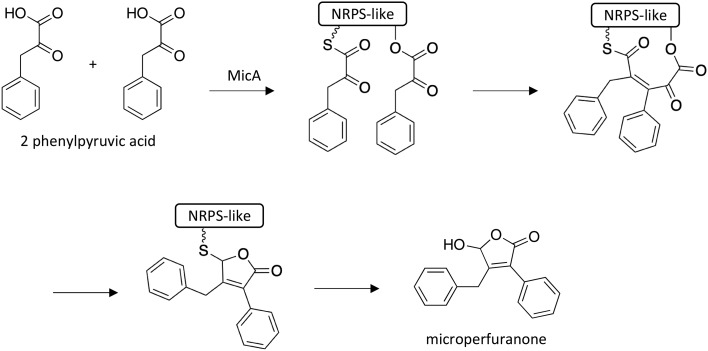

To investigate SMs produced by NRPS-like genes, scientists replaced the native promoters of the 13 predicted NRPS-like genes in A. nidulans with the inducible alcA promoter.30 Induction of NRPS-like MicA resulted in enhanced production of microperfuranone, which has previously been isolated from Anixiella micropertusa and Emericella nidulans.31,32 Heterologous expression of micA in A. niger confirmed that MicA is solely responsible for the biosynthesis of microperfuranone, which was proposed to involve the joining of two units of phenylpyruvic acid via an aldol condensation reaction while tethered to MicA (Scheme 4). Next, the tethered intermediate undergoes sulfur-mediated cyclization to yield a furan ring, followed by decarboxylation and keto–enol tautomerization to form microperfuranone.

Scheme 4. Biosynthesis of microperfuranone in A. nidulans.30.

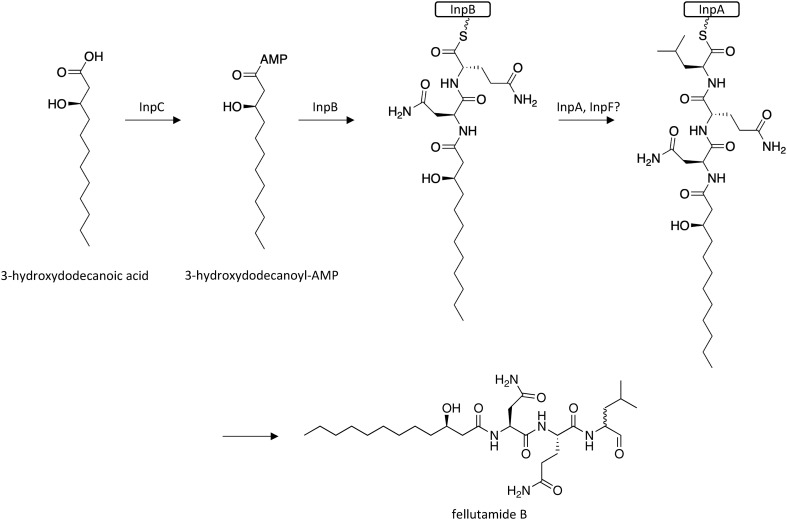

3.5. Biosynthesis of fellutamide B

Fellutamide B, which was originally isolated from Penicillium fellutanum, is a potent proteasome inhibitor that also induces nerve growth factor release.33 In the past decade proteasome inhibitors have emerged as effective anticancer agents, with several second-generation proteasome inhibitors currently being tested in clinical settings.34–36 To identify biosynthetic gene clusters that may be involved in the production of proteasome inhibitors, researchers searched for potential resistance genes harbored within SM gene clusters in A. nidulans.37 Interestingly, they found that within the inp cluster, inpE encoded a putative proteasome component, which has no obvious role in SM biosynthesis. The silent inp cluster was activated by replacing the promoters of six genes within the cluster with the inducible promoter alcA, which revealed that fellutamide B is the SM cluster's final product. The fellutamide B biosynthetic gene cluster contains two NRPS genes, a predicted fatty-acyl-AMP ligase, a NRPS product release/transfer protein, a transporter, and inpE, which was found to confer resistance to internally produced fellutamide B.37 Biosynthesis of fellutamide B was proposed to involve initial activation of 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid by IncP to form 3-hydroxydodecanoyl-AMP, which undergoes addition of l-Asn and l-Gln while tethered to InpB, followed by addition of l-Leu while tethered to InpA (Scheme 5). The product is then released to yield fellutamide B.

Scheme 5. Biosynthesis of fellutamide B in A. nidulans.37.

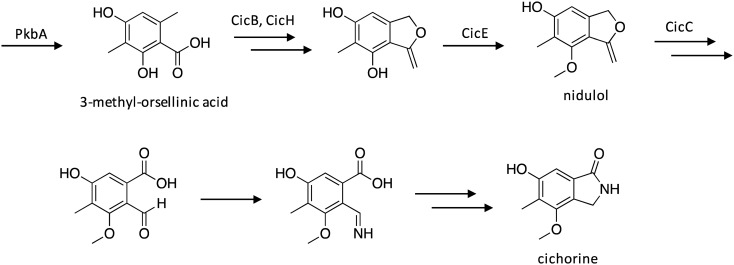

3.6. Biosynthesis cichorine

Culturing of A. nidulans on yeast extract sucrose (YES) led to the production of cichorine, which is a phytotoxin that possesses activity against corn, soybeans, and knapweed.38,39 The cichorine biosynthetic gene cluster was identified using targeted individual gene deletions, revealing that the gene cluster consisted of NR-PKS-encoding pkbA, regulatory protein-encoding cicD, transporter-encoding cicA, and four tailing protein-encoding genes.38 Analysis of extracts produced by deletion strains enabled some insights into the cichorine biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 6), which involves initial production of 3-methyl-orsellinic acid by the PKS PkbA, which undergoes a ring-closing transformation by CicB and/or CicH, followed by phenol group methylation by CicE to yield nidulol. The remaining steps in cichorine biosynthesis involve a lactone to lactam conversion carried genes found outside the cic SM gene cluster, perhaps by genes within a different cluster, such as the case with xanthone and terpene biosynthesis in A. nidulans.40,41

Scheme 6. Biosynthesis of cichorine in A. nidulans.38.

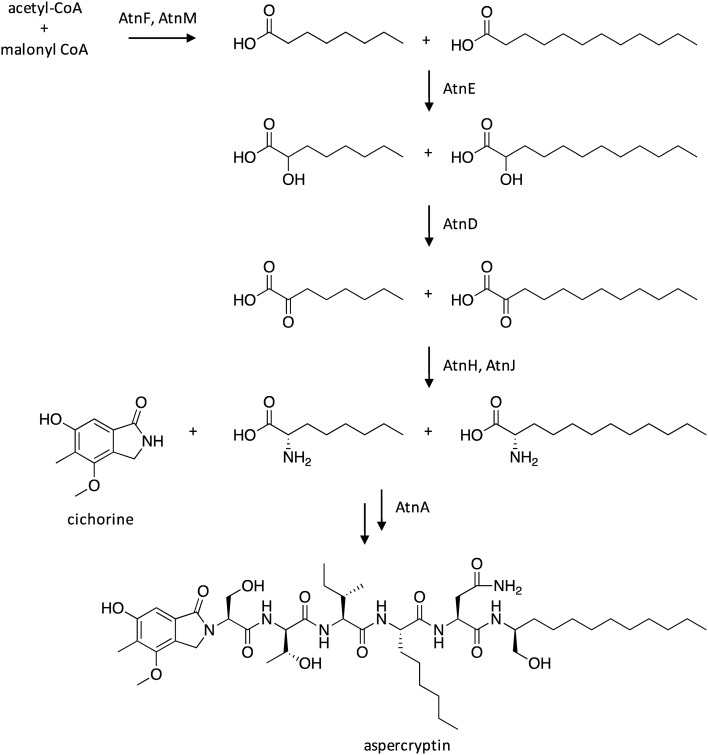

3.7. Biosynthesis aspercryptin

Researchers generated a “genetic dereplication” strain, which is deficient in production of most A. nidulans SMs, including sterigmatocystin,42 the emericellamides,43 asperfurnanone,44 the prenyl xanthones,40 terrequinone,45 F9775A and B,46 asperthecin,47 austinol,41 and dehydroaustinol.41 The clean SM background facilitated the detection of a novel SM, designated as aspercryptin.48 The structure of aspercryptin indicated that it is biosynthesized by a NRPS pathway and involves the incorporation of six amino acids, including threonine, isoleucine, aspartic acid/asparagine, serine, lysine-like, and one unidentified amino acid. NRPS enzymes feature adenylation domains responsible for the correct identification and incorporation of amino acid monomers during SM biosynthesis. Often times, each adenylation domain present within an NRPS is responsible for the incorporation of a different amino acid.49 Therefore, scientists searched for an NRPS containing six adenylation domains in silico, which revealed NRPS-encoding AN7884. Microarray expression array data had previously revealed that AN7884 was co-regulated with 13 adjacent genes, including genes encoding for a short chain dehydrogenase, a cytochrome P450 hydroxylase, a fatty acid synthase, amino acid aminotransferase, and transporters. Targeted gene deletions confirmed the involvement of these genes in the biosynthesis of aspercryptin, which were designated as atnA–atnN, and evaluation of biosynthetic intermediates in deletion strains facilitated the elucidation of the aspercryptin biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 7). Interestingly, the proposed pathway uses cichorine as a precursor, which was confirmed by deleting the NR-PKS involved in cichorine biosynthesis, which eliminated production of aspercryptin.

Scheme 7. Biosynthesis of aspercryptin in A. nidulans.48.

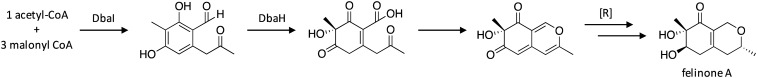

3.8. Biosynthesis of felinone A

To search for negative regulators of secondary metabolism, researchers generated auxotrophic mutants by replacing the coding sequences of target SM core synthase enzymes with the A. fumigatus riboB gene (AfriboB).50 Thus, when the target SM cluster is inactive, the fungus will not be able to survive without media supplementation of riboflavin. The strain was then mutagenized with 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (NQO), which causes base-pair substitutions, and subsequent growth without riboflavin enabled the detection of strains in which the induced mutations resulted in SM cluster activation. This technique enabled the identification of the transcription factor mcrA. Investigation of SM production in mutant strains lacking and overexpressing mcrA revealed that it is a negative regulator of at least ten SM clusters in A. nidulans. Additionally, large-scale cultivation of the mcrA-deletion strain enabled the isolation of the antibiotic felinone A.51 Examination of the structure of felinone A, combined with products previously reported to be produced by the dba cluster,29,52 enabled the biosynthetic pathway for felinone A to be proposed (Scheme 8). The pathway involves generation of the polyketide product by the NR-PKS DbaI, followed by dearomatization via hydroxylation by the FAD-binding monooxygenase DbaH. The final steps of the pathway include a ring closure to generate an azaphilone ring system followed by several reductive steps that have not been clarified yet.

Scheme 8. Biosynthesis of felinone A in A. nidulans.50.

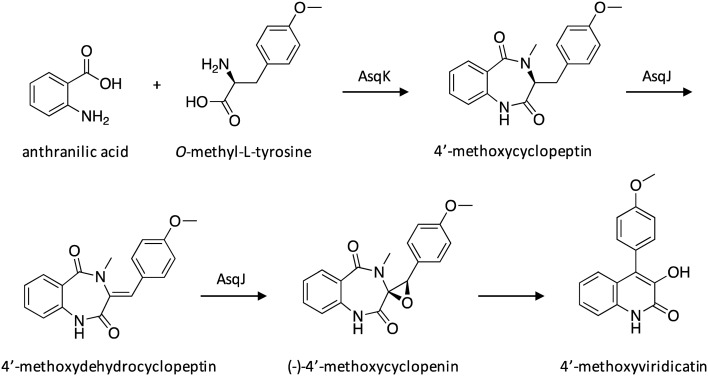

3.9. Biosynthesis 4′-methoxyviridicatin

Quinolone alkaloids are a class of SMs that exhibit a broad range of medicinally relevant characteristics, including antibiotic, antiviral, antimalarial, and antitumor activities.53 A 6,6-quinolone scaffold is present in a variety of quinolone alkaloids, including 4′-methoxyviridicatin and structurally similar viridicatin, which exhibits strong activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.54 To elucidate the biosynthetic nature of this class of compounds, a silent candidate cluster containing genes encoding an NRPS, a prenyltransferase, terpene cyclases, and redox enzymes was activated through overexpression of the NRPS AsqK.55 A combination of in vivo and in vitro assays were conducted to elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of 4′-methoxyviridicatin (Scheme 9). The proposed pathway involves an anthranilic acid and O-methyl-l-tyrosine precursor, which undergo conversion to 4′-methoxycyclopeptin by NRPS AsqK. Next, the dioxygenase AsqJ catalyzes two distinct oxidation reactions, the first being a desaturation reaction to form a double bond and yield 4′-methoxydehydrocyclopeptine, followed by monooxygenation of that double bond to form an epoxide and yield (–)-4′-methoxycyclopenine. Interestingly, this epoxide formation then facilitates subsequent non-enzymatic rearrangement to form the 6,6-quinolone viridiatin scaffold from the 6,7-bicyclic core of (–)-4′-methoxycyclopenine, yielding 4′-methoxyviridicatin.

Scheme 9. Biosynthesis of 4′-methoxyviridicatin in A. nidulans.55.

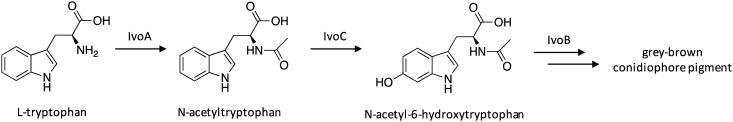

3.10. Biosynthesis of grey-brown conidiophore pigment

Fungal pigments have a wide range of beneficial properties, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities, and can act as natural alternatives to chemically synthesized colorants.56 Historically, the NRPS IvoA and the phenol oxidase IvoB were known to be involved in grey-brown condidiophore pigment production,57 although its biosynthetic pathway had not been fully elucidated. Additionally, microarray expression data had revealed that the gene adjacent to ivoA, ivoC, was coregulated with ivoA.58 Researchers therefore replaced the native promoters of ivoA, ivoB, and ivoC with the inducible promoter alcA, which resulted in hyphal accumulation of dark pigments.59 The biosynthetic pathway was reconstructed in a stepwise manner to assign functions to each involved gene, revealing that IvoA is the first NRPS known to acetylate tryptophan, leading to N-acetyltryptophan. IvoC is then responsible for 6-hydroxylation of N-tryptophan, followed by subsequent oxidation by IvoB to yield grey-brown conidiophore pigment (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10. Biosynthesis of grey-brown conidiophore pigment in A. nidulans.57,59 .

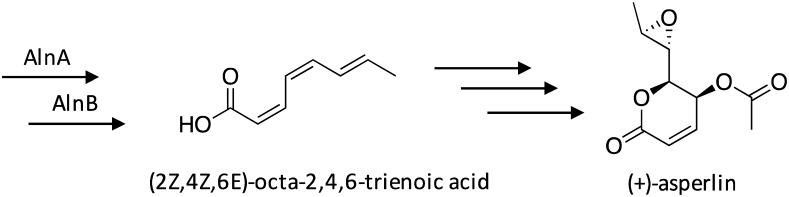

3.11. Biosynthesis of (+)-asperlin

The SM (+)-asperlin, whose production has been reported in A. nidulans, Aspergillus caespitosus, and Aspergillus versicolor, possesses antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activity.60–64 The biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for (+)-asperlin production was recently identified in A. nidulans using a novel cluster activation method that features the use of a hybrid transcription factor,65 as previous attempts to activate this cluster through overexpression of the cluster's transcription factor were unsuccessful.29 Up-regulation of the hybrid transcription factor, which featured the DNA-binding domain of the cluster's native transcription factor fused to the activation domain of the asperfuranone gene cluster transcription factor AfoA, led to production of (+)-asperlin. Targeted gene deletions in combination with RNA-seq confirmed the involvement of 10 genes in the biosynthesis of (+)-asperlin, which were designated as alnA–alnI and alnR. Additionally, (2Z,4Z,6E)-octa-2,4,6-trienoic acid, which exhibits photoprotectant properties,66 was identified as a biosynthetic pathway intermediate (Scheme 11). The individual steps involved in the biosynthesis of (+)-asperlin remain to be fully elucidated.

Scheme 11. Biosynthesis of (+)-asperlin in A. nidulans.65.

4. Genetic characterization of secondary metabolites in Aspergillus fumigatus

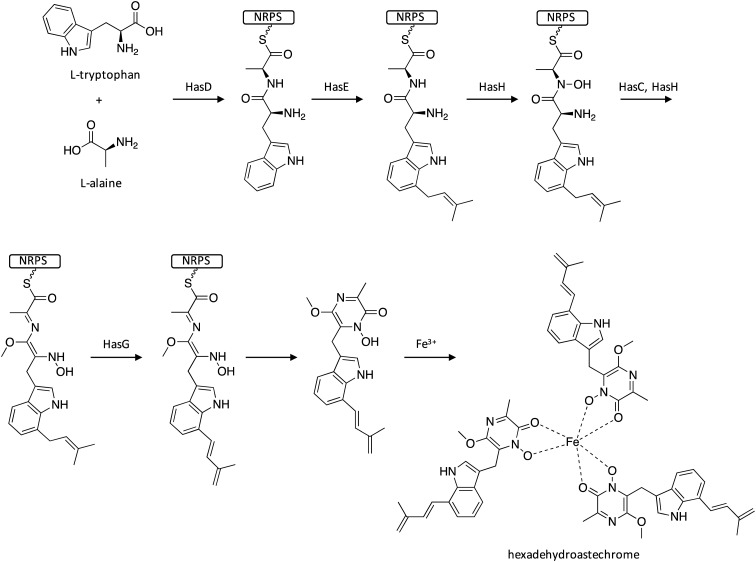

4.1. Biosynthesis of hexadehydroastechrome

The positive global regulator of secondary metabolism LaeA has been shown to also play a major role in positive regulation of virulence genes in A. fumigatus.67 One way that LaeA alters virulence is through up-regulation of SM gene clusters responsible for biosynthesis of toxins, such as the epipolythiodioxopiperazine gliotoxin.13,68 To search for other SM virulence factors in A. fumigatus, scientists reasoned that such SMs would be up-regulated by both LaeA and exposure to host/hypoxia environments. Microarrays were compared to identify gene clusters that exhibited down-regulation in laeA-deletion strains and up-regulation in response to host exposure/hypoxia.69–72 Such comparison revealed the identification of the has eight-gene cluster, harboring genes encoding the NRPS HasD, the DMATS HasE, two C6 transcription factors HasA and HasF, the transporter HasB, the O-methyltransferase HasC, the FAD binding protein HasG, and the cytochrome P450 HasH.73 C6 transcription factors commonly regulate expression of genes within a SM cluster and hasA was highly down-regulated in the laeA-mutant strain. Researchers therefore overexpressed hasA by replacing its promoter with the constitutive gdpA promoter, which led to activation of the has gene cluster and production of the Fe(iii) complex hexadehydroastechrome. Interestingly, activation of the has cluster enhanced the virulence of A. fumigatus, significantly decreasing the survival of infected mice.73 To investigate the biosynthetic pathway of hexadehydroastechrome, individual gene knockout mutants were generated for hasB–hasE in the OE::hasA genetic background strain. Biosynthesis of hexadehydroastechrome initiates by loading the NRPS HasD with l-tryptophan and l-alanine, followed by prenylation of the Trp-Ala-dipeptide (Scheme 12). The subsequent biosynthetic tailoring reactions performed by HasH, HasC, and HasG were proposed to occur while the intermediate remains tethered to the NRPS. Next, the NRPS releases a O-methylated diketopiperazine derivative, which then forms a trimeric complex with Fe(iii).

Scheme 12. Biosynthesis of hexadehydroastechrome in A. fumigatus.73.

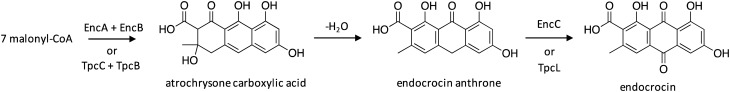

4.2. Biosynthesis of endocrocin

The anthraquinone endocrocin has been isolated from a broad range of species, including various fungi,74,75 plants,76 and insects.77 Historically, anthraquinones have been known to display various medicinal properties, such as anti-inflammatory and antitumor bioactivities, and have been used in dyes, cosmetics, paper manufacturing, and as food additives.76,78,79 However, more recently endocrocin was found to contribute to the pathogenicity of A. fumigatus through inhibition of neutrophil recruitment.80 Interestingly, endocrocin was found to be biosynthesized through two distinct routes by physically discrete clusters enc and tpc in A. fumigatus.81,82 Biosynthesis by the enc cluster was initially reported in A. fumigatus CEA10-derived strains,81 which did not produce trypacidin due to a single nucleotide mutation present in PKS-encoding tpcC.83 To elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of endocrocin in A. fumigatus, the genome was surveyed for a candidate NR-PKS. Endocrocin was previously identified as a biosynthetic intermediate of monodictyphenone that was only produced in strains lacking the activity of the decarboxylase MdpH.84 Bioinformatics were therefore used to search for proteins with similarity to the monodictyphenone-producing NR-PKS MdpG in A. nidulans, which revealed the identification of three NR-PKS genes within the A. fumigatus genome. The biosynthetic gene clusters of two of the NR-PKSs suggested a final product more complex than endocrocin, so researchers focused on the third NR-PKS, which they named EncA. The NR-PKS EncA lacked the thioesterase (TE) or Claisen cyclase (CLC) domain that is usually responsible for releasing the nascent polyketide product in this class of enzymes.85,86 In such TE-less enzymes, the polyketide product is instead released by metallo-β-lactamase-type thioesterases enzymes.87 To confirm involvement of EncA in the biosynthesis of endocrocin, a encA-mutant was generated, which resulted in a strain deficient in endocrocin production.81 Subsequent deletion of tailoring genes revealed the involvement of the metallo-β-lactamase domain protein EncB and the anthrone oxidase EncC in endocrocin biosynthesis, which enabled its biosynthetic pathway to be proposed (Scheme 13). Surprisingly, deletion of the cluster gene encD resulted in increased production of endocrocin, which could have occurred for two reasons: EncD may catalyze the formation of an unknown product from endocrocin or EncD may inhibit endocrocin biosynthesis by converting an intermediate to an unknown product.81

Scheme 13. Biosynthesis of endocrocin in A. fumigatus.81.

Redundant biosynthesis of endocrocin by the tpc cluster was later revealed upon elucidation of the trypacidin biosynthetic pathway in A. fumigatus strain Af293, which will be discussed more thoroughly in the following section.82 To investigate any interrelationships between endocrocin and trypacidin, encA was deletion in the trypacidin-producing Af293 strain. In contrast to the previous study conducted in CEA10-derived strains with an inactive tpc cluster, deletion of encA did not result in complete loss of endocrocin production, although production yields decreased.81,82 Subsequent generation of a mutant strain deficient in both encA and tpcA resulted in a complete loss of endocrocin production. To further investigate the biosynthesis of endocrocin by tpc-encoded enzymes, genes within the tpc cluster were individually deleted in the encA-background, which revealed a second pathway for endocrocin biosynthesis in A. fumigatus (Scheme 13). Endocrocin is likely a shunt product of the trypacidin biosynthesis, as the beginning pathway steps both involve the production of atrochrysone carboxylic acid from TpcC and TpcB, which then undergoes a loss of H2O to yield endocrocin anthrone. Formation of endocrocin is then catalyzed by TpcL.

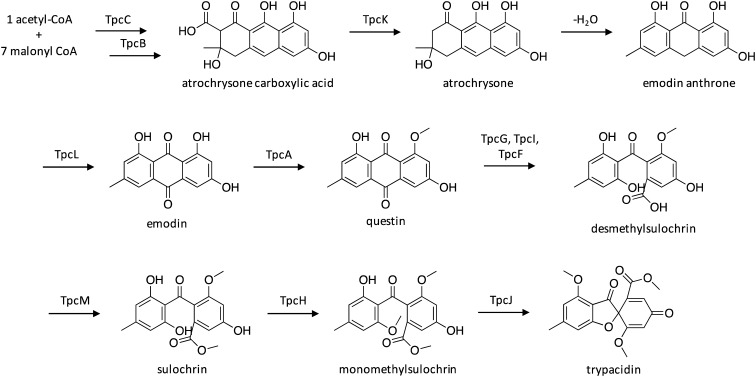

4.3. Biosynthesis of trypacidin

The spore metabolite trypacidin, which was initially identified as an anti-protozoal agent,88,89 was more recently shown to be cytotoxic against human lung cells.90 A candidate cluster for trypacidin biosynthesis was identified as a cluster harboring the TE-less NR-PKS TpcC,82 which belongs to the same NR-PKS clade as the endocrocin PKS in A. fumigatus,81 the monodicyphenone PKS in A. nidulans,84 and the geodin PKS in A. terreus.91 The 13 genes within the cluster, 12 of which displayed high sequence homology to the geodin-producing cluster,91 were individually deleted and mutant strains were analyzed for the production of pathway intermediates,82 which enabled proposal of the trypacidin biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 14). The first few steps are identical to that of endocrocin biosynthesis, with the generation of atrochrysone carboxylic acid from NR-PKS TpcC and metallo-β-lactamase TpcB. TpcK then catalyzes decarboxylation to yield atrochrysone, which then undergoes dehydration to yield emodin anthrone. The anthrone oxygenase TpcL catalyzes the addition of a ketone functional group to yield emodin, followed by activity of the O-methyltransferase TpcA to yield questin. The remaining steps in the pathway were proposed based on comparison to similar pathways, and involve a ring opening catalyzed by TpcG, TpcI, and TpcF, followed by O-methylation by both TpcM and TpcH to generate monomethylsulochrin, which is then converted to trypacidin by TpcJ.

Scheme 14. Biosynthesis of trypacidin in A. fumigatus.82.

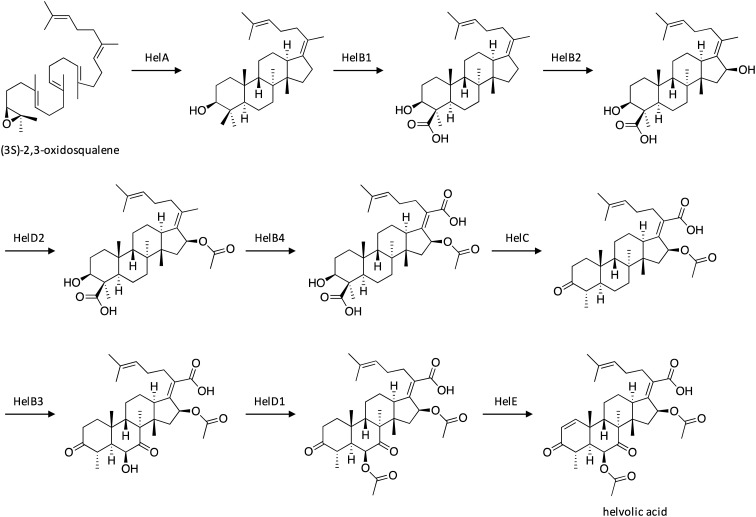

4.4. Biosynthesis of helvolic acid

Fusidane-type antibiotics are a class of fungi-derived triterpenes that include helvolic acid,92 fusidic acid,93 and cephalosporin P1,94 all which display potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria.95 Structurally, they have a characteristic tetracyclic core that is generated from enzymatic cyclization of (3S)-2,3-oxidosqualene.96 Notably, fusidane-type antibiotics have exhibited no cross-resistance to commonly used antibiotics,97,98 which has drawn the attention of scientists to search for analogs with increased bioactivity.99 Researchers therefore investigated the full biosynthetic pathway of helvolic acid, as such understanding can facilitate the development of useful fusidane-type antibiotic derivatives. A portion of genes within the helvolic-acid-producing hel cluster had previously been identified. To further characterize the cluster, its nine genes were heterologously introduced stepwise in Aspergillus oryzae, which resulted in the production and of helvolic acid and 21 derivatives, three of which exhibited increased antibiotic activity against Staphylococcus aureus when compared to helvolic acid.100 A biosynthetic pathway was proposed for helvolic acid (Scheme 15), which involves initial cyclization of (3S)-2,3-oxidosqualene by oxidosqualene cyclase HelA to yield protosta-17(20)Z,24-dien-3β-ol. The intermediate then undergoes two rounds of oxidation by HelB1 and HelB2, followed by acetylation by HelD2, oxidation by HelB4, and oxidative decarboxylation by HelC. Next, HelB3 mediates two oxidative reactions which result in hydroxyl and ketone formation, followed by O-acetylation by HelD1, and dehydrogenation by HelE to yield helvolic acid. Interestingly, this study revealed unique roles for HelB1 and HelC, which work together to remove the C-4β methyl group through oxidation followed by decarboxylation, a mechanism distinct from the similar demethylation reaction that occurs during sterol biosynthesis.

Scheme 15. Biosynthesis of helvolic acid in A. fumigatus.100.

4.5. Biosynthesis of fumipyrrole

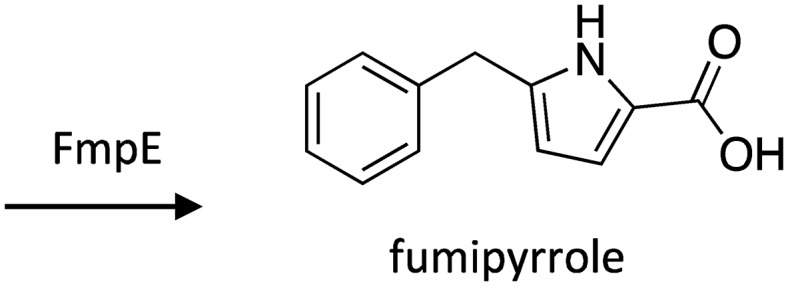

A. fumigatus is capable of surviving in a myriad of distinct niches, ranging from the human lung, where it can cause invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals, to decaying vegetation, where it plays important roles in breaking down organic matter.101 The capacity to readily survive in different habitats, which correlates with pathogenicity in physiological environments, is largely dependent on the ability to sense external stimuli and respond with different signal transduction cascades, including the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway.102 To explore the targets of the cAMP/PKA pathway, the catalytic subunit 1 of PKA was overexpressed, which resulted in induction of the pathway and differential expression of various genes, including high up-regulation of the transcription factor fmpR, which is harbored in a SM gene cluster.103 To identify the SM produced by this cluster, fmpR was overexpressed using the Tet-on system,104 which led to activation of six other cluster genes encoding the NRPS FmpE, the fructosyl amino acid oxidase FmpA, hypothetical proteins FmpB and FmpC, ABC multidrug transporter FmpD, and the phenol-2-monooxygenase FmpF. The product produced by this biosynthetic gene cluster was identified as the novel SM fumipyrrole (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16. Biosynthesis of fumipyrrole in A. fumigatus.103.

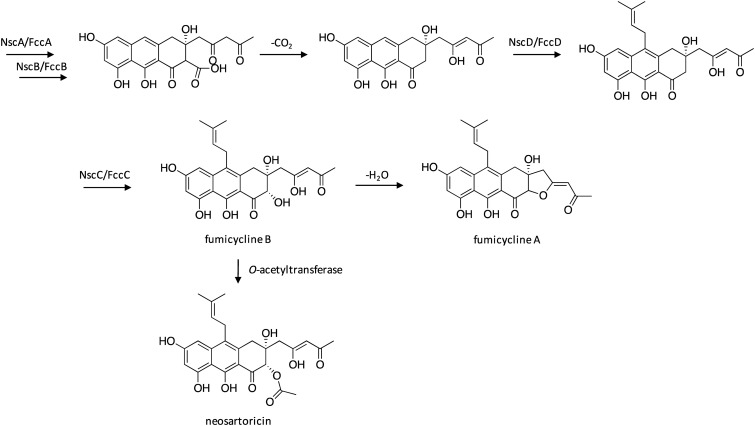

4.6. Biosynthesis of neosartoricin and fumicyclines

The meroterpenoid neosartoricin was first isolated following activation of the six-gene nsc/fcc cluster in both A. fumigatus and Neosartorya fischeri, which harbors genes encoding the TE-less NR-PKS NscA/FccA, the metallo-β-lactamase-type thioesterase NscB/FccB, the Flavin-dependent monooxygenase NscC/FccC, the polycyclic prenyltransferase NscD/FccD, the NAD-dependent dehydratase NscE/FccE, and the pathway-specific Zn(ii)2Cys6 transcription factor NscR/FccR.105 In both species, the cluster was activated through overexpression of NscR/FccR. Shortly after, related fumicyclines A and B were isolated from A. fumigatus following cocultivation with Streptomyces rapamycinicus.106 Full genome microarrays were used to identify the gene cluster responsible for production of fumicyclines, which revealed up-regulation of the nsc/fcc gene cluster following cocultivation. To confirm the involvement of this cluster, NR-PKS-encoding nscA/fccA was deleted, which resulted in complete elimination of fumicycline production. For both studies, the biosynthetic pathway of neosartoricin and fumicyclines was proposed based on the detection of intermediates and shunt products (Scheme 17). Biosynthesis initiates with reactions catalyzed by the NR-PKS NscA/FccA and release of the nascent polyketide product by NscB/FccB. The intermediate then undergoes a loss of CO2, followed by prenylation catalyzed by NscD/FccD and hydroxylation by NscC/FccC to yield fumicycline B. Fumicycline B then undergoes O-acetylation to yield neosartoricin or dehydration to yield fumicycline A.

Scheme 17. Biosynthesis of neosartoricin and fumicyclines in A. fumigatus.105,106 .

4.7. Biosynthesis of fumagillin

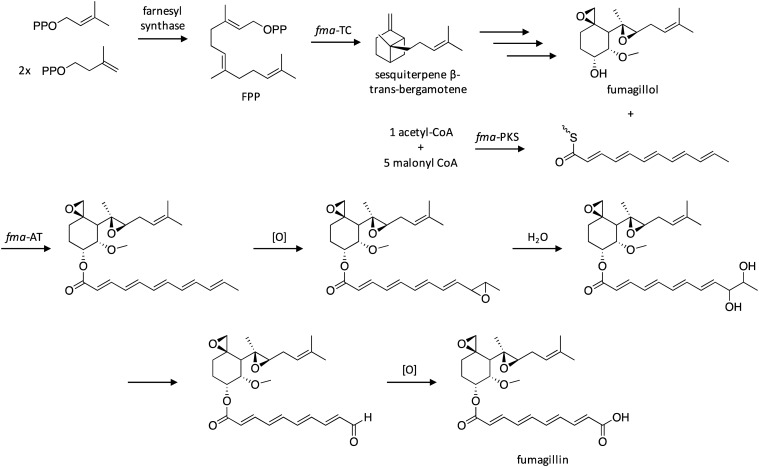

Since its discovery in 1951, the antibiotic fumagillin has been extensively studied for its medicinal applications, which include anti-angiogenic activity through inhibition of human type 2 methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP-2) and potential use for treatment of amebiasis and microsporidiosis.107–110 Fumagillin is a meroterpenoid that possesses a highly-oxygenated cyclohexane ring esterified with a decatetraenedioic acid. Interestingly, although the total synthesis of fumagillin has been well-studied,111,112 its biosynthetic pathway had not been elucidated. Researchers therefore examined SM clusters harboring genes encoding HR-PKSs in A. fumigatus, and identified a candidate cluster containing genes encoding MetAP-2 and a type 1 MetAP, which they hypothesized might be involved in self-resistance against fumgaillin.113 To confirm that this cluster was responsible for fumagillin production, the cluster's HR-PKS, designated fma-PKS, was deleted, which resulted in complete elimination of fumagillin production. In vitro assays were used to decipher the functions of other enzymes encoded within the fma cluster, which enabled the biosynthetic pathway of fumagillin to be proposed (Scheme 18). Biosynthesis of the terpenoid portion of the carbon backbone involves initial generation of farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), which is converted to sesquiterpene β-trans-bergamotene by the terpene cyclase fma-TC, which then undergoes two rounds of epoxidation, dihydroxylation, and O-methylation to yield fumagillol. In parallel, the HR-PKS fma-PKS biosynthesizes the polyketide product, which is then combined with fumagillol in a reaction catalyzed by fma-AT. The intermediate's terminal alkene is then epoxidated, followed by hydrolysis to yield a vicinal diol, followed by cleavage to yield an aldehyde, and oxidation to generate fumagillin.

Scheme 18. Biosynthesis of fumagillin in A. fumigatus.113.

5. Genetic characterization of secondary metabolites in Aspergillus niger

5.1. Biosynthesis of kotanin

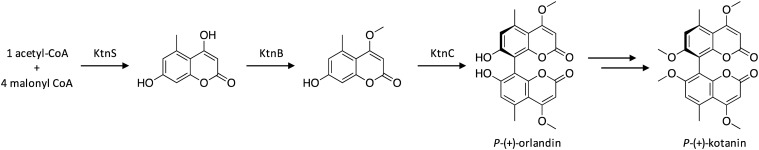

To identify the biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for biosynthesis of the bicoumarin kotanin in A. niger, scientists searched for gene clusters containing NR-PKS genes, since formation of the monomeric coumarin does not require any reduction steps.114 The candidate clusters were further narrowed down to include only clusters harboring cytochrome P450 or monooxygenases, which would be required for kotanin production. The NR-PKS required for kotanin biosynthesis was confirmed to be KtnS through targeted gene deletion, which led to complete loss of coumarin production. The functions of the other genes within the cluster were investigated using targeted gene deletions, which confirmed the involvement of the O-methyltransferase KtnB and the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase KtnC in kotanin biosynthesis, and allowed the biosynthetic pathway for kotanin to be proposed (Scheme 19). The pathway is initially catalyzed by KtnS to synthesize the pentaketidic dihydroxycoumarin, followed by O-methylation by KtnB to yield a siderin derivative. Next, KtnC catalyzes an oxidative phenol coupling reaction while controlling regio- and stereoselectivity to generate P-(+)-orlandin. Docking experiments were performed to explore the mechanism of regio- and stereoselectivity, which revealed that it is likely dependent on substrate orientation in the active site of KtnC.114P-(+)-kotanin is then generated following O-methylation of P-(+)-orlandin.

Scheme 19. Biosynthesis of kotanin in A. niger.114.

5.2. Biosynthesis of azanigerones

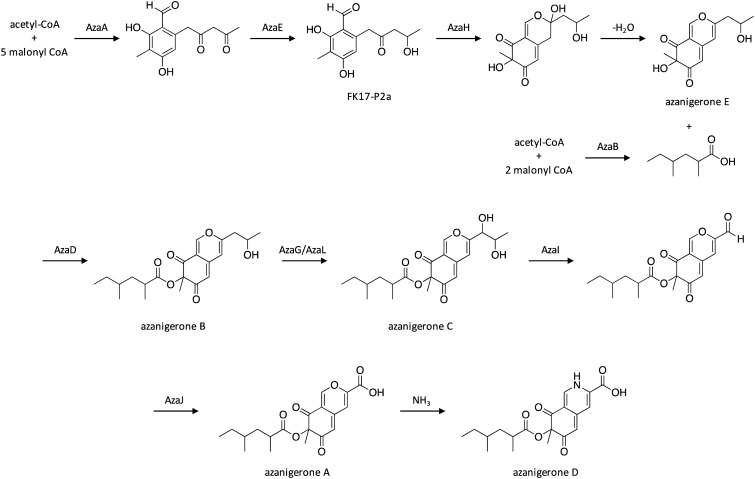

Although many SM gene clusters contain only one encoding PKS, others contain two that can either work in sequence or in convergence to biosynthesize the polyketide product.44,115,116 When two PKS enzymes work in sequence, the polyketide chain biosynthesized from the first PKS is transferred to the second PKS, which continues the chain elongation process. Two PKSs working in convergence function independently of one another, and the polyketide products generated from each enzyme are ultimately connected by other pathway enzymes. To explore similar PKS–PKS partnerships in A. niger, researchers overexpressed a pathway-specific transcription factor that was present in a cluster that also harbored the NR-PKS AzaA and the HR-PKS AzaB, which led to the production of previously unknown azaphilone SMs.117 Azaphilones are a class of compounds that consist of a highly-oxygenated bicyclic core and a chiral quaternary center.118 They are structurally diverse and feature a wide range of bioactivities, including antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and nematicidal properties.118 The most abundant azaphilone produced in the overexpression strain was designated as azanigerone A. Other related compounds were produced at earlier time points, including FK17-P2a and azanigerones B and C, and azanigerone D was observed to replace azanigerone A at later time points. To further explore the mechanism of collaboration between NR-PKS AzaA and HR-PKS AzaB in azanigerone biosynthesis, an azaB-deletion strain was generated, which upon culturing led to the accumulation of two new compounds, designated as azanigerones E and F. This suggests a convergence biosynthesis model, in which AzaA and AzaB biosynthesize two discrete polyketide products which are combined at later step in the pathway. Interestingly, this is the first report of convergent collaboration between an NR-PKS and a HR-PKS in SM biosynthesis. These findings, combined with subsequent in vitro experiments to confirm the role of tailoring enzyme AzaH, enabled scientists to propose a pathway for azaphilone biosynthesis in A. niger (Scheme 20). The NR-PKS AzaA catalyzes biosynthesis of a hexaketide precursor, which then undergoes a terminal ketone reduction catalyzed by the ketoreductase AzaE to yield FK17-P2a. Next, the monooxygenase AzaH hydroxylates FK17-P2a, which facilitates formation of the pyran-ring and generation of azanigerone E. In parallel, the HR-PKS AzaB biosynthesizes a 2,4-dimethylhexanoyl chain, which is combined with FK17-P2a to generate azanigerone B in a reaction facilitated by the acyltransferase AzaD. Next, azanigerone B is hydroxylated by FAD-dependent monooxygenase AzaG or AzaL to yield azanigerone C, followed by C–C oxidative cleavage by cytochrome P450 AzaI, and oxidation of the aldehyde to a carboxylic acid by AzaJ, yielding azanigerone A. Azanigerone A can then undergo addition of NH3 to generate azanigerone D, which was observed to replace azanigerone A production at later time points.

Scheme 20. Biosynthesis of azanigerones in A. niger.117.

5.3. Biosynthesis of yanuthone D

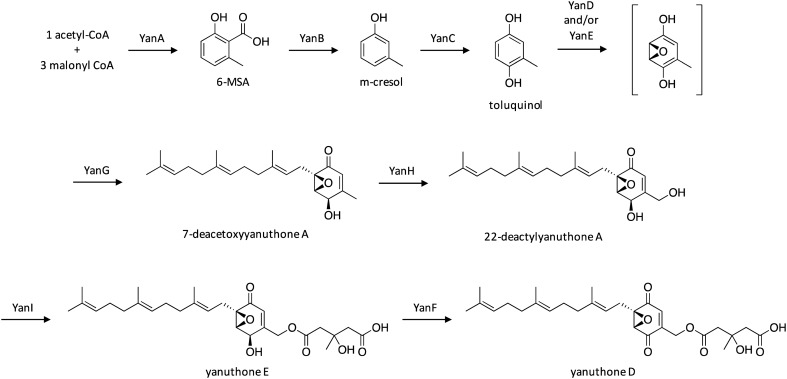

The yanuthones comprise a group of SMs that feature an epoxylated six-member ring with a sesquiterpene and two other varying side chains.119 The core structure of yanuthones can be derived from the polyketide 6-methylsalicylic acid (6-MSA), which are distinguished as class I yanuthones, or from an unknown precursor that generates a C6-core scaffold, which are distinguished as class II yanuthones.120 The class I yanuthone, yanuthone D, has displayed potent antimicrobial activity against Candida albicans, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.119,121 To investigate the capacity of A. niger to produce 6-MSA-derived SMs, the A. niger PKS-encoding YanA was heterologously expressed in A. nidulans to confirm its involvement in the biosynthesis of the polyketide 6-MSA.121 To identify the final SM product of the 10-gene yan cluster, a yanA-deletion strain was generated and screened on various media, which revealed a loss of production of two SMs that were identified as yanuthones D and E. The biosynthetic pathway of yanuthone D was further investigated by individually deleting genes within the yan cluster which resulted in the accumulation of yanuthone intermediates, and enabled a biosynthetic pathway to be proposed (Scheme 21). The pathway initiates with the biosynthesis of 6-MSA by the PKS YanA, followed by decarboxylation by YanB, and hydroxylation by the cytochrome P450 YanC, yielding toluquinol. Epoxide formation is then catalyzed by YanD and/or YanE, followed by prenylation by YanG to form 7-deacetoxyyanuthone A. Next, cytochrome P450 YanH catalyzes conversion to 22-deacetylyanuthone A, followed by conversion to yanuthone E by the O-mevalon transferase YanI. Interestingly, this is the first time that O-mevalon transferase activity has been molecularly characterized. Lastly, the oxidase YanF catalyzes the formation of yanuthone D from yanuthone E.

Scheme 21. Biosynthesis of yanuthone D in A. niger.121.

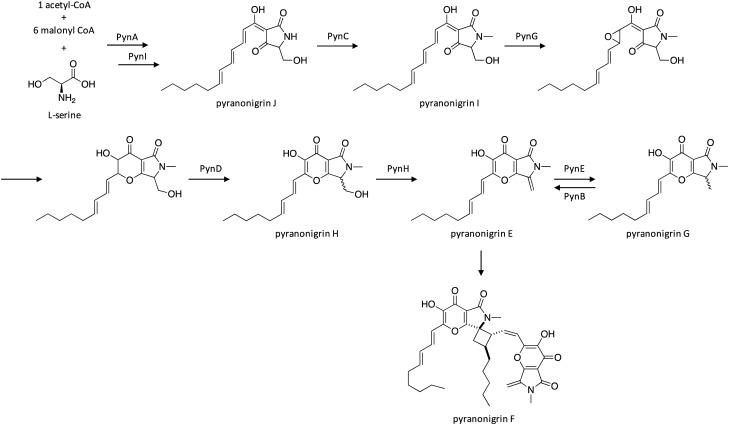

5.4. Biosynthesis of the pyranonigrins

The pyranonigrins are a group of compounds produced by A. niger with 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging antioxidant activity.20,122 The pyn gene cluster was activated by introducing a plasmid containing the pathway-specific Zn2Cys6 transcriptional regulator pynR under control of the arginase (aga) promoter.123 Cluster activation resulted in induced transcription of PKS–NRPS-encoding pynA, FAD-dependent oxidoreductase-encoding pynB, N-methyltransferase-encoding pynC, cytochrome P450 oxidase-encoding pynD, and NAD-binding protein-encoding pynE, along with production of the SM pyranonigrin E. In a subsequent study, the pyn cluster was activated by replacing the pynR promoter with the robust glaA promoter,124 and the biosynthetic pathway of pyranonigrin E was investigated using cluster gene deletion mutants in combination with in vivo and in vitro assays.125 Researchers identified three additional pyn cluster genes, including flavin-dependent oxidase-encoding pynG, aspartase protease-encoding pynH, and thioesterase-encoding pynI. The proposed biosynthetic pathway initiates with biosynthesis of the polyketide–nonribosomal peptide hybrid product by PynA, followed by release of the intermediate from PynA by PynI, generating pyranonigrin J (Scheme 22). Next PynC catalyzes N-methylation of pyranonigin J, followed by epoxidation by PynG, which facilitates the subsequent ring closure. PynD and PynH then catalyze the formation of pyranonigrin E, which can then dimerize to form pyranonigrin F. Alternatively, PynE can catalyze the conversion of pyranonigrin E to pyranonigrin G, which can be reversed by the PynB.

Scheme 22. Biosynthesis of pyranonigrins E–J in A. niger.123,125 .

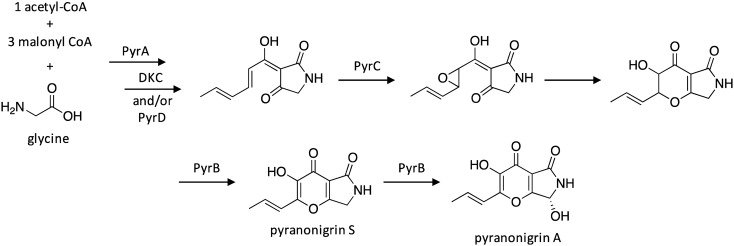

The potent antioxidant pyranonigrin A, whose production was previously reported in A. niger,126,127 was found to be biosynthesized by a PKS–NRPS gene cluster different from the pyn cluster.128 The biosynthetic pathway of pyranonigrin A, which was elucidated in Penicillium thymicola, involves initial biosynthesis of the polyketide–nonribosomal peptide product by the PKS–NRPS PyrA, followed by product release catalyzed by either a Dieckmann cyclase (DKC) and/or the hydrolase PyrD (Scheme 23). Next, FAD-binding monooxygenase PyrC may catalyze epoxidation followed by subsequent ring closure to form the pyrano[2,3-c]pyrrole core, followed by conversion to pyranonigrin S and pyranonigrin A by cytochrome P450 PyrB.

Scheme 23. Biosynthesis of pyranonigrin A in A. niger.128.

6. Genetic characterization of secondary metabolites in Aspergillus terreus

In 2014, a review summarizing advances in SM genome mining in A. terreus was published by C. J. Guo et al.,129 which included the genetic characterization of terretonin,130 asperfuranone,12 terrein,131 terreic acid,132 and acetylaranotin.133 This section focuses on discoveries made in A. terreus SM biosynthesis research since that review was published.

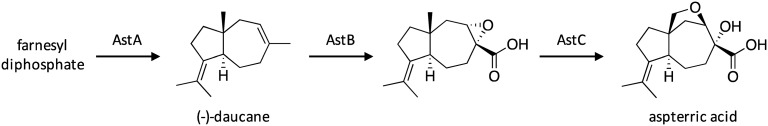

6.1. Biosynthesis of aspterric acid

The gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of the potent herbicide aspterric acid was identified using a resistance-gene-directed approach.134 Scientists focused on identifying SMs that would target the dihydroxyacid dehydratase (DHAD) enzyme within the branched chain amino acid (BCAA) biosynthetic pathway, which is necessary for plant growth and considered a specific target for weed-control agents.135 They reasoned that gene clusters responsible for biosynthesis of a DHAD inhibitor may also include a self-resistance gene, such as an additional copy of DHAD that is not sensitive to the produced inhibitor. Such a cluster was identified in A. terreus, which included genes encoding the sesquiterpene cyclase AstA, cytochrome P450 enzymes AstB and AstC, and a homolog of DHAD AstD. Interestingly, this cluster is conserved across multiple fungal genomes, including Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181, Penicillium brasilianum, and Penicillium solitum strain RS1.134 To activate the silent gene cluster, astA, astB, and astC were heterologously expressed stepwise in Saccharomyces cerevisiae RC01, which resulted in the production of the sesquiterpenoid aspterric acid and its biosynthetic intermediates, and enabled researchers to propose the biosynthetic pathway for aspterric acid (Scheme 24). Its biosynthesis initiates with the cyclization of farnesyl diphosphate by AstA to yield (–)-daucane, followed by AstB-catalyzed oxidation to convert a methyl group to a carboxylic acid and form an epoxide. Next, the oxidation of a methyl group by AstC yields an alcohol, which facilitates an intramolecular epoxide opening to generate aspterric acid. Aspterric acid was found to inhibit DHAD at sub-micromolar levels, highlighting its capacity for use as a potent herbicidal agent. Additionally, the ability of the DHAD AstD to confer self-resistance to aspterric acid was confirmed.

Scheme 24. Biosynthesis of aspterric acid in A. terreus.134.

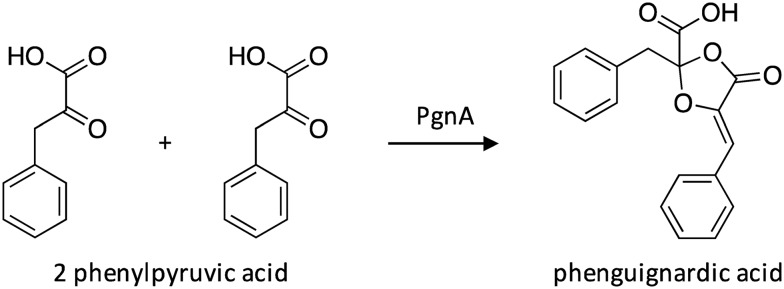

6.2. Biosynthesis of phenguignardic acid

The NRPS-like-encoding gene pgnA was activated in A. terreus using a doxycycline-dependent inducible Tet-on expression system that had previously been developed for the activation of genes in A. niger.104,136 The system involves gdpA-mediated constitutive expression of the doxycycline-dependent transcriptional activator rtTA fused to tetO7 sites and a Pmin promoter sequence that precedes the target gene. In the presence of doxycycline, rtRA binds to tetO7-Pmin and activates transcription of the target gene. The study revealed that activation of the pgnA resulted in the production of phenguignardic acid,136 which has displayed non-host-specific phytotoxic activity.137 Heterologous expression in A. nidulans confirmed that PgnA is independently responsible for phenguignardic acid production (Scheme 25).

Scheme 25. Biosynthesis of phenguignardic acid in A. terreus.136.

6.3. Biosynthesis of asperphenamate

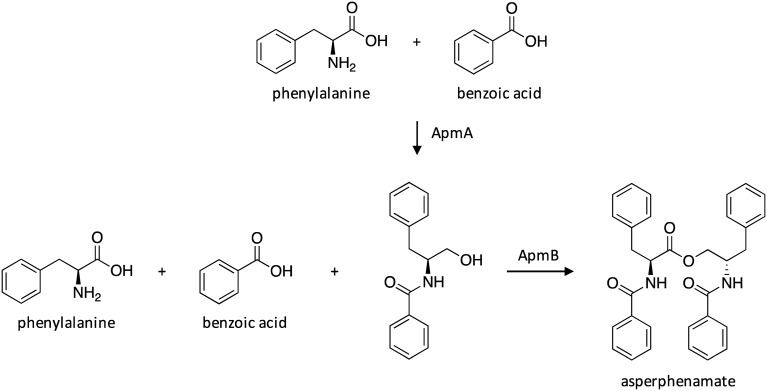

The amino acid ester asperphenamate and its derivatives have displayed potent activity against breast cancer cell lines.138,139 The structure of asperphenamate consists of N-benzoylphenylalanine and N-benzoylphenylalaninol subunits, which are linked together by an ester. Its bioactivity and rare structure prompted the molecular characterization of asperphenamate. Targeted gene deletions in asperphenamate-producing Penicillium brevicompactum confirmed that the apm cluster, which harbors two NRPSs and is conserved across the genomes of A. terreus and Aspergillus aculeatus, is responsible for asperphenamate biosynthesis.140 The biosynthetic pathway of asperphenamate was elucidated by examining the production of biosynthetic intermediates in deletion strains and by conducting feeding studies in heterologous hosts. This study confirmed that NRPSs ApmA and ApmB are sufficient for biosynthesis of asperphenamate, despite the presence of potential tailoring enzymes within the cluster (Scheme 26). First, ApmA biosynthesizes an amide intermediate from phenylalanine and benzoic acid precursors. ApmB activates the same substrates and accepts the ApmA-biosynthesized linear dipeptidyl precursor, which are combined through inter-molecular ester bond formation to generate asperphenamate. Interestingly, this was the first study to reveal a two-module NRPS system responsible for the biosynthesis of an amino acid ester.

Scheme 26. Biosynthesis of asperphenamate in A. terreus.140.

6.4. Biosynthesis of citreoviridin

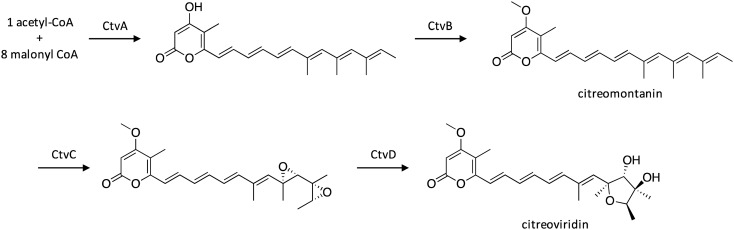

Citreoviridin is an ATP synthase inhibitor that has been investigated as a therapeutic agent to target breast cancer.141 To identify its biosynthetic gene cluster in A. terreus, a resistance-gene-driven approach was utilized.142 One such cluster contained the F1-ATPase β-chain-encoding CtvE, which is a subunit of the target of citreoviridin, along with genes encoding the HR-PKS CtvA, the SAM-dependent methyltransferase CtvB, the flavin-dependent monooxygenase CtvC, and the hydrolase CtvD. To investigate the biosynthetic pathway of citreoviridin, the genes within the ctv cluster were heterologously expressed stepwise in A. nidulans, which resulted in the production of intermediates and allowed a biosynthetic pathway to be proposed (Scheme 27). CtvA first biosynthesizes an α-pyrone intermediate, which undergoes hydroxyl group methylation by CtvB to yield citreomontanin. Next, the citreomontanin terminal alkenes undergo isomerization to form a (17Z)-hexaene, which is bisepoxidated by CtvC. CtvD then catalyzes formation of the tetrahydrofuran ring, resulting in citreoviridin production.

Scheme 27. Biosynthesis of citreoviridin in A. terreus.142.

7. Conclusion

In the post-genomic era, fungal sequencing initiatives have accelerated our ability to link SMs to their biosynthetic gene clusters. Further, they have enhanced our understanding of fungal SM biosynthetic processes and the underpinning genes that define them. Such knowledge can have enormous applications for pharmaceutical production and industrial processes, as genetic engineering can be used to optimize SM production levels or to generate useful second-generation analogs. Despite the significant progress made in the past six years, many SMs that Aspergillus species have the capacity to produce still have not been identified or linked to their biosynthetic gene clusters, which remains true for many other fungal species. Thorough characterization of the Aspergillus secondary metabolome will require a combination of approaches, including the use of inducible promoters, overexpression of pathway-specific regulators, growth in various conditions, heterologous expression, and gene knockout techniques, along with the collaborative effort of the research community.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research in the Wang group is supported in part by R21 AI127640 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, by NNX15AB49G from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and by WP-2339 from the U.S. Department of Defense, Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program. We thank Adriana Blachowicz for proofreading the manuscript and for providing the image of A. fumigatus used in the Graphical Abstract.

Biographies

Jillian Romsdahl

Jillian Romsdahl is currently a National Research Council Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC. She earned her Ph.D. in molecular pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Southern California in 2018, where she conducted research in the laboratory of Professor Clay Wang. She received her B.S. in chemistry at the University of California, Santa Cruz in 2012. Her research has focused on molecular genetic analysis of secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi and microbial adaptation to radiation and the space environment.

Clay C. C. Wang

Professor Clay C. C. Wang is currently Department Chair and Professor of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Professor of Chemistry at the University of Southern California (USC). He received his B.S. in chemistry from Harvard University in 1996 while working in the laboratory of Professor George Whitesides. He received his Ph.D. in chemistry from California Institute of Technology in 2001 in the laboratory of Professor Peter Dervan. Between 2001 and 2003, he was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University in the laboratory of Professor Chaitan Khosla. He has been on the faculty at USC since 2003. His research focuses on fungal natural product discovery and biosynthesis.

References

- Demain A. L. and Fang A., in History of Modern Biotechnology I, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach M. A., Walsh C. T. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Bustamante Z. R., Rivera-Orduña F. N., Martínez-Cárdenas A., Flores-Cotera L. B. J. Antibiot. 2010;63:460–467. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo D., Ammirati E. J. Biol. Regul. Homeostatic Agents. 2011;25:493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlach K., Hertweck C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:1753–1760. doi: 10.1039/b821578b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode H. B., Bethe B., Höfs R., Zeeck A. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:619. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<619::AID-CBIC619>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagan J. E., Calvo S. E., Cuomo C., Ma L.-J., Wortman J. R., Batzoglou S., Lee S.-I., Baştürkmen M., Spevak C. C., Clutterbuck J., Kapitonov V., Jurka J., Scazzocchio C., Farman M., Butler J., Purcell S., Harris S., Braus G. H., Draht O., Busch S., D'Enfert C., Bouchier C., Goldman G. H., Bell-Pedersen D., Griffiths-Jones S., Doonan J. H., Yu J., Vienken K., Pain A., Freitag M., Selker E. U., Archer D. B., Peñalva M. Á., Oakley B. R., Momany M., Tanaka T., Kumagai T., Asai K., Machida M., Nierman W. C., Denning D. W., Caddick M., Hynes M., Paoletti M., Fischer R., Miller B., Dyer P., Sachs M. S., Osmani S. A., Birren B. W. Nature. 2005;438:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/nature04341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjærbølling I., Vesth T. C., Frisvad J. C., Nybo J. L., Theobald S., Kuo A., Bowyer P., Matsuda Y., Mondo S., Lyhne E. K., Kogle M. E., Clum A., Lipzen A., Salamov A., Ngan C. Y., Daum C., Chiniquy J., Barry K., LaButti K., Haridas S., Simmons B. A., Magnuson J. K., Mortensen U. H., Larsen T. O., Grigoriev I. V., Baker S. E., Andersen M. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E753–E761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715954115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis G. L. Microbiol. 2008;154:1555–1569. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. F., Somoza A. D., Keller N. P., Wang C. C. C. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:351–371. doi: 10.1039/c2np00084a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y.-M., Oakley C. E., Ahuja M., Entwistle R., Schultz A., Chang S.-L., Sung C. T., Wang C. C. C., Oakley B. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7720–7731. doi: 10.1021/ja401945a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais T. R. T., Keller N. P. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22:447–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latgé J. P. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12:310–350. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran S. K., Ross D. D., Doyle L. A., Yang W., Greenberger L. M. Cancer Res. 2000;60:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster E., Dunn-Coleman N., Frisvad J. C., Van Dijck P. W. M. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;59:426–435. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban M., Shaaban K. A., Abdel-Aziz M. S. Org. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;2:6. doi: 10.1186/2191-2858-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choque E., El Rayess Y., Raynal J., Mathieu F. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:1081–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiort J., Maksimenka K., Reichert M., Perović-Ottstadt S., Lin W. H., Wray V., Steube K., Schaumann K., Weber H., Proksch P., Ebel R., Müller W. E. G., Bringmann G. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1532–1543. doi: 10.1021/np030551d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y., Ito C., Itoigawa M., Osawa T. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2007;71:2515–2521. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobert J. A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2003;2:517–526. doi: 10.1038/nrd1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samiee S. M., Moazami N., Haghighi S., Aziz Mohseni F., Mirdamadi S., Bakhtiari M. R. Iran. Biomed. J. 2003;7:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Willke T., Vorlop K. D. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;56:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s002530100685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert T., Friebel S. Green Chem. 2016;18:2922–2934. [Google Scholar]

- Bromann K., Toivari M., Viljanen K., Vuoristo A., Ruohonen L., Nakari-Setälä T. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.-S., Chen B., Chiang Y.-M., Wang C. C. C. ChemBioChem. 2019;20:329–334. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201800486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlach K., Schuemann J., Dahse H.-M., Hertweck C. J. Antibiot. 2010;63:375–377. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaegashi J., Praseuth M. B., Tyan S.-W., Sanchez J. F., Entwistle R., Chiang Y.-M., Oakley B. R., Wang C. C. C. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2862–2865. doi: 10.1021/ol401187b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]