Abstract

The glycom e describes the complete repertoire of glycoconjugates com posed of carbohydrate chains, or glycans, that are covalently linked to lipid or protein molecules. Glycoconjugates are formed through a process called glycosylation and can differ in their glycan sequences, the connections between them and their length. Glycoconjugate synthesis is a dynamic process that depends on the local milieu of enzymes, sugar precursors and organelle structures as well as the cell types involved and cellular signals. Studies of rare genetic disorders that affect glycosylation first highlighted the biological importance of the glycome, and technological advances have improved our understanding of its heterogeneity and complexity. Researchers can now routinely assess how the secreted and cell-surface glycom es reflect overall cellular status in health and disease. In fact, changes in glycosylation can modulate inflammatory responses, enable viral immune escape, promote cancer cell metastasis or regulate apoptosis; the com position of the glycom e also affects kidney function in health and disease. New insights into the structure and function of the glycom e can now be applied to therapy developm ent and could improve our ability tofine-tune im m unological responses and inflammation, optimize the performance of therapeutic antibodies and boost immune responses to cancer. These examples illustrate the potential of the emerging field of ‘glycomedicine’.

Glycobiology studies the structure, biosynthesis and biology of glycans, which are widely distributed in nature. Most glycans are found on the outermost surfaces of cellular and secreted macromolecules and are remark-ably diverse. Simple and highly dynamic protein-bound glycans are also abundant in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cells, where they exert regulatory effects. In fact, in addition to forming important structural features, the sugar components of glycoconju gates modulate or mediate a wide variety of functions in physiological and pathophysiological states1. Glycoproteins and polysaccharides also have important functions in bacterial cells, and glycoproteins have central roles in the biology of most viruses.

Glycoconjugates are formed by the addition of sugars to proteins and lipids; 17 monosaccharides commonly found in mammalian glycoconjugates are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (REF2). A vast number of naturally occurring sugars can be combined to create a variety of unique glycan structures on lipid and protein molecules that modulate their function. Multiple enzymatic site preferences, as well as the use of stereochemical α or β conjugations, create further diversity in where and how these sugars are linked to each other. In fact, altogether, these features imply the potential existence of ~10 12 different branched glycan structures3. Protein glycosylation includes the addition of N-linked glycans, O-linked glycans, phosphorylated glycans, glycosam inoglycans and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors to peptide backbones as well as C-mannosylation of tryptophan residues (FIG. 1). Glycolipids are form ed through the addition of sugars to lipids; this type of glycoconjugate includes glycosphingolipids (GSLs)4,5 (Fig. 1). Glycosylation of proteins and lipids occurs in the endoplasm icreticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, with most of the term in al processing occurring in the cis-, medial- and trans-Golgi compartments. In these organelles, glycosyltransferases and glycosidases form carbohydrate structures in a series of steps that are controlled by substrate availability, enzyme activity, levels of gene transcription and enzyme location within the organelles (Fig. 2). In fact, the glycome of a particular cell reflects its unique gene-expression pattern, which controls the levels of the enzymes responsible for glycoconjugation. Unlike the genome, exome or proteome, the glycome is produced in a non-templated manner and is intricately controlled at multiple levels in the ER and Golgi apparatus.

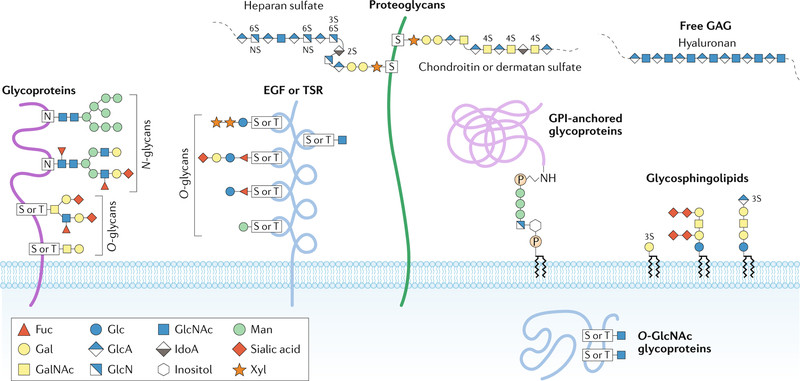

Fig. 1 |. Major types of glycosylation in humans.

Glycans can be covalently attached to proteins and lipids to form glycoconjugates; glycans in these compounds are classified according to the linkage to the lipid, glycan or protein moieties. Glycoproteins consist of glycans and glycan chains linked to nitrogen and oxygen atoms of amino acid residues and are thus termed N-glycans and O-glycans, respectively. N-glycans consist of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) attached by a β1-glycosidic linkage to the nitrogen atom of the amino group of Asn (N) at the consensus glycosylation motif Asn-X-Ser/Thr (in which X denotes any amino acid except for Pro). These branched and highly heterogeneous N-glycan structures consist of a core glycan containing two GlcNAc residues and three mannose (Man) residues. Perhaps the most diverse form of protein glycosylation is O-glycosylation, in which glycans attach to the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl groups of Ser (S) or Thr (T) residues. O-glycans can be further subclassified on the basis of the initial sugar attached to the protein and the additional sugar structures added to the initial glycan. For example, mucin-type O-glycosylation denotes that the initial glycan is N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc); mucin-type glycans can be further classified on the basis of the glycans attached to the initial GalNAc6. Other types of O-glycans, such as O-linked fucose (Fuc) and O-linked Man, often occur in specific proteins or protein domains, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeats, thrombospondin type I repeats (TSR) or dystroglycan. N-glycans and O-glycans are often capped with negatively charged sialic acid. O-GlcNAc is a unique type of O-glycosylation that is synthesized by O-GlcNAc transferase; it occurs in the cytosol and nucleus. Proteoglycans represent a major class of glycoproteins that are defined by long glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains attached to proteins through a tetrasaccharide core consisting of glucuronic acid (GlcA)–galactose (Gal)–Gal–xylose (Xyl); this carbohydrate core is attached to the hydroxyl group of Ser at Ser-Gly-X-Gly amino acid motifs. Proteoglycan GAGs can be further classified according to the number, composition and degree of sulfation of their repeating disaccharide units; common GAGs include heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoproteins represent another major class of glycoconjugates. These glycoproteins are linked at the carboxyl terminus through a phosphodiester linkage to phosphoethanolamine attached to a trimannosyl-nonacetylated glucosamine (Man3-GlcN) core; the GlcN residue is linked to phosphatidylinositol, which is embedded in the cell membrane. Glycosphingolipids are a class of glycoconjugate in which glycans, such as Gal or glucose (Glc), are attached to cellular membrane lipids. Another major class of glycans is represented by GAGs that are not attached to protein cores, such as hyaluronan, which is synthesized at the plasma membrane by sequential addition of GlcA and GlcNAc. IdoA, iduronic acid. Adapted with permission from ref.277, Springer Nature Limited and from ref.278, Stanley, P. Golgi glycosylation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 0033, a005199 (2005), with permission from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

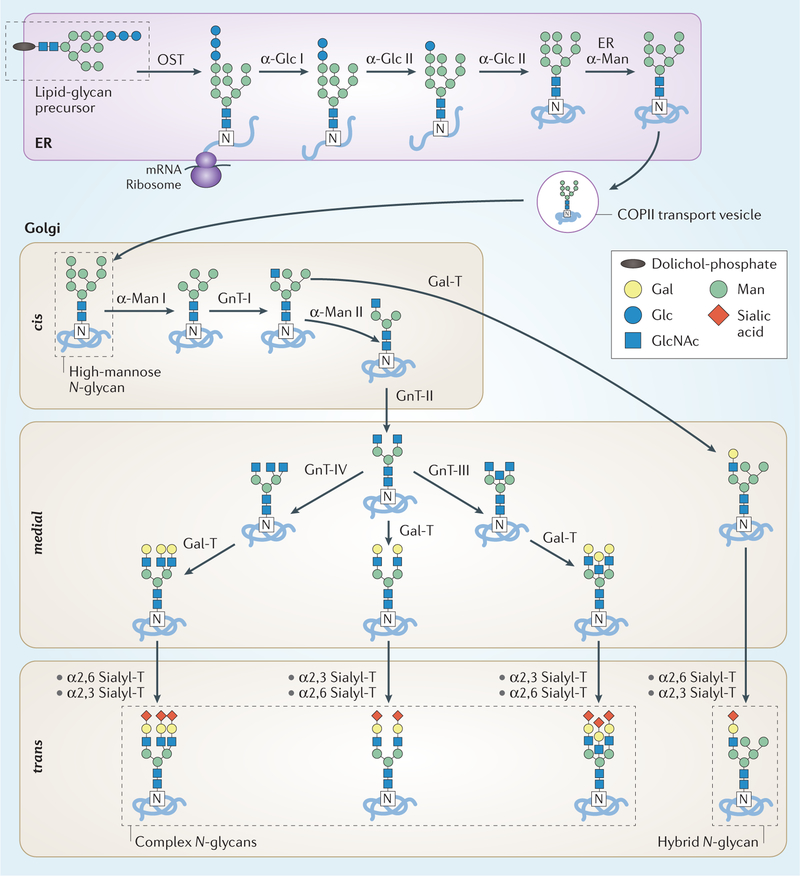

Fig. 2 |. N-glycan biosynthesis in the secretory pathway.

N-glycan synthesis is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the en bloc transfer of a lipid-glycan precursor (that is, glucose (Glc)3 mannose (Man)9 N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)2 bound to dolichol phosphate) to Asp by the multisubunit oligosaccharyltransferase (OST). The glucose residues are sequentially removed by two α-glucosidases (α-Glc I–II) and an initial Man residue is removed by the ER α-mannosidase (ER α-Man). After a quality-control checkpoint, the glycoprotein moves to the Golgi apparatus for additional trimming by α-mannosidase I and II (α-Man I–II) and further glycan modifications. A cis-to-trans distribution of glycosidases and transferases — GlcNAc-transferase I–IV (GnT-I–IV), β1,4 galactosyltransferases (Gal-T), α2,3 sialyltransferase (α2,3, Sialyl-T) and α2,6 sialyltransferase (α2,6 Sialyl-T) — facilitates further processing by these carbohydrate-modifying enzymes to create a plethora of N-glycoforms that often terminate with sialic acid moieties. The final site-specific N-glycan composition is affected by the expression levels of glycosyltransferases, the accessibility of the glycoprotein glycosylation sites and the length of time during which the glycoprotein remains in the ER and Golgi apparatus. Gal, galactose.

In this Review, we discuss fundamental concepts in glycobiology and integrate these with recent advances in understanding the key roles of the glycome in health and disease. We review how glycosylation patterns are altered in multiple hum an diseases, including congenital disorders of glycosylation (C D G s) as well as auto-immune, infectious and chronic inflammatory diseases, and cancer. We also provide specific examples of how an improved understanding of abnormal glycosylation in various diseases might offer new diagnostic options and/or targets for glycan-mediated therapeutic interventions.

Main types of glycosylation in humans

N - linked glycosylation.

Many proteins are modified by N-glycosylation, which refers to the attachment of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to the nitrogen atom of an Asn side chain by a β−1N linkage. These Asn-linked glycoconjugates contain a G lcNAc2 mannose (Man)3 core, to which a variable number of other monosaccha-rides can be added or removed (FIGS 1,2). These additions include, for example, galactosylation, GlcNAclyation, sialylation and fucosylation, and they determine whether the final structure is classed as a high-mannose N-glycan, a hybrid N-glycan or a complex N-glycan (FIG. 2). N-glycans are found in most living organism s and have a crucial role in regulating m any intracellular and extracellular functions. N-glycosylation depends on the formation of a lipid precursor in which GlcNAc and Man form a branched carbohydrate structure that is attached to dolichol phosphate (Dol-P) on the cytoplasmic side of the ER6. This lipid precursor is then flipped to face the ER lumen, where M an and glucose units are added to form a 14-sugar structure — Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 (FIG. 2). Following completion of the Dol-P-carbohydrate structure, an oligosaccharyltransferase adds the carbohydrate chain to a protein at an Asn-X-Ser/Thr site (in which X denotes any amino acid except for Pro); the nascent carbohydrate-protein conjugate undergoes further processing in the ER, which usually involves removal of the glucose residues as p art of a quality-control process. The structure then moves to the Golgi apparatus (that is, the cis-Golgi), where the carbohydrate structures are trim med further by a series of specific m annosidases before being transferred to the medial- Golgi for maturation. It is within the medial- and trans-Golgi compartments that hybrid and complex N-glycans are produced through the addition of GlcNAc, galactose, sialic acid and fucose sugars6 (FIG. 2).

O - glycosylation.

Glycosylation can occur on amino acids with functional hydroxyl groups, which are most often Ser and Thr. In humans, the most com m on sugars linked to Ser or Thr are GlcN Ac and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)7 (FIG. 1). GalNAc-linked glycans, often called mucin-type O-glycans, are abundant on m any extracellular and secreted glycoproteins8–9, including mucins, which form a crucial interface between epithelial cells and the external mucosal surfaces of the body. Mucins are characterized by a variable number of tandem repeats with a high content of Pro, Ser and Thr, which creates m any sites for O-glycosylation. Moreover, these sites often have extended O-glycan cores that create a gel-like substance thought to protect both the glycoproteins and cellular surfaces from external stress, microbial infection and self-recognition by the immune system. This class of O-glycans contains six major basic core structures (that is, cores 1–4, terminal GalNAc (Tn) and sialyl-Tn antigens) and is integral, along with other O-linked glycoconjugates, to the classification of blood-group antigens (BOX 1). Mucin-type O-glycan synthesis is initiated by polypeptide GalNAc transferases (GA LN Ts)7. These GALNTs differ in their specificity for amino acid motifs, although they are often promiscuous, which adds a level of regulation to how and where O-glycans are attached. Non-templated sequential addition of glycans to the initial GalNAc gives rise to a diverse set of carbohydrate structures that are often highly clustered on certain glycoproteins, including mucins and human immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1). These sugars are added as the protein moves through the cis-, medial- and trans-Golgi compartments and, unlike N-glycans, pre-processing and post-processing that trim s existing sugar structures does not occur. Instead, the glycopeptide O-glycan chains are modified by distinct glycosyltransferases that can expand the existing structure with galactose, GlcNAc, sialic acid and, in some instances, fucose7.

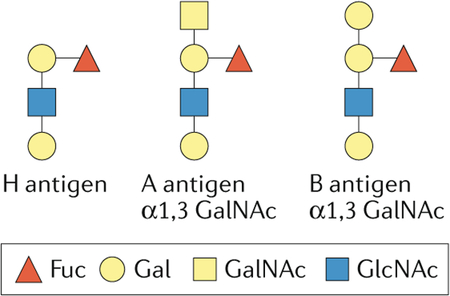

Box 1 |. Blood-group sugars can be immunogenic.

Many blood-group antigens on erythrocytes are glycans conjugated to lipids or proteins. The ABO(H) blood-group antigens were discovered in the early 20th century on the basis of the existence of antibodies in some individuals that agglutinated red blood cells from other individuals. Follow-up studies revealed that these antibodies recognized glycan epitopes on the cell surface of red blood cells that were also expressed in other cells of the same individual. These studies established for the first time that glycans can be antigenic. The ABO(H)-associated glycan epitopes are determined by the inheritance of glycosyltransferase genes in ABO, FUT1 and FUT2 loci. Group O individuals express the H antigen, the precursor to A and B antigens. Group A individuals have α1,3-N-acetylglucosamine (GalNAc) attached to the galactose residue of the H antigen, whereas Group B individuals have α1,3-Gal. Additional blood-group antigens have been described, and many contain glycan epitopes such as Lewis antigen. Compatibility of ABO(H) and other antigens between donor and recipient is necessary for a successful blood transfusion268,269. Some blood-group antigens affect the binding of bacteria and viruses to host cell surfaces and represent risk factors in chronic inflammatory diseases270–273. For example, the blood-group O phenotype is associated with disease severity in patients infected with Vibrio cholerae274. Human noroviruses, which cause sporadic and epidemic gastroenteritis, also selectively bind ABO(H) and Lewis blood-group antigens275; some viral strains recognize the A and/or B and H antigens, whereas others recognize only the Lewis and/or H antigens. Thus, susceptibility to these viruses is influenced by the host’s blood-group antigens and the sequence variations of the capsid protein276.

GlcNAc linked to Ser or Thr is typically found on intracellular glycoproteins present in nuclear, mitochondrial and cytoplasmic compartments (FIG. 1). Unlike the mucin-type O-glycans, which are GalN Ac-linked, addition of G lcN A c does not typically occur in the Golgi apparatus and is not extended; this synthesis is regulated through O-linked GlcNAc (O-GlcNAc) transferases (OGTs) and O-GlcNAcases (OGAs)10. Although different forms of these enzymes exist depending on the sub-cellular compartment, they all perform the same rapid cycle of addition and rem oval of GlcNAc from protein substrates. This dynamic process seem s to be unique to this glycosylation motif and is thought to regulate m any cellular functions, including cellular metabolism. Moreover, O-GlcNAc modification competes with protein phosphorylation at Ser and Thr residues, adding to the complexity of regulatory circuits11,12. This functional role of O-glycosylation can be controlled by the expression levels of the enzymes involved, as well as substrate concentrations. For the purposes of this Review, other glycoprotein conjugates will not be discussed in detail (reviewed in REFS4,13–15).

Glycosphingolipids.

GSLs comprise a sphingolipid to which a glycan is attached at the C1 hydroxyl position of a ceramide; they are one of the most abundant glycolipids in humans and are typically found in the lipid bilayers of cellular mem branes16 (FIG. 1). GSL glycosylation starts with the addition of glucose or galactose to the lipid moiety at the cytoplasmic side of the ER or the Golgi apparatus, but the structure is then flipped to the luminal side for further processing. The enzymes that initiate GSL glycosylation are specific for lipids, but further processing of the carbohydrate chain can be performed by more general glycosyltransferases. The distribution of different types of GSLs is controlled by functional competition between multiple glycosyltransferases16. GSLs perform critical cellular functions associated with the formation of lipid rafts, and their glycan com position imparts specific GSL properties16.

Proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans.

Proteoglycans are glycoproteins in the extra cellular matrix that, in addition to containing canonical N-glycans and O-glycans, are characterized by the presence of long sugar repeats attached via O-linked glycosylation motifs17. These extended sugar chains are termed glycosaminoglycans and contribute to a substantial proportion of the proteoglycan’s molecular mass. Whereas N-glycans typically include 5–12 monosaccharides, a glycosaminoglycan motif can easily contain more than 80 sugars (for example, keratan sulfate is a poly-N-acetyllactosamine chain that contains up to 50 disaccharide units)16. These long chains are constructed through disaccharide repeats formed by GlcNAc or GalNAc, combined with an uronic acid (that is, glucuronic or iduronic acid) or galactose. Glycosaminoglycans are functionally diverse and include heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate and hyaluronan18. Glycosaminoglycans are crucial to the formation of the glycocalyx, an essential structure for the maintenance of the cell mem brane that also functions as a reservoir for sequestered growth factors18.

Extrinsic glycosylation events.

Extrinsic glycosylation is the process by which soluble glycan-modifying enzymes, such as glycosyltransferases that circulate in the blood, conjugate a monosaccharide to an existing sugar structure extracellularly19–21. Common acceptor structures for extrinsic glycosylation on mammalian glycoconjugates are galactose (G al)(β3)-GlcNAc, Gal(β3)-GalNAc, Gal(β4)-GlcNAc and GalNAc; β3 and β4 represent two different linkage positions on the conjugating sugar19–21. Circulating glycosyltransferases are generated by cleaving the soluble portion of the mem brane-associated enzyme and releasing it into the circulation; these soluble enzymes most often originate from liver hepatocytes and platelets. Platelets also contribute to extrinsic glycosylation processes by providing activated sugar intermediates, such as activated sialic acid, galactose and/or fucose19–21. Extrinsic glycosylation processes can generate Lewis and sialyl Lewis antigens, which are fucosylated carbohydrate moieties, as well as Tn and sialyl-Tn antigens, which are O-glycans with a terminal GalNAc or sialylated GalNAc, respectively. These glycosylation motifs have an important role in regulating leukocyte trafficking during inflammatory responses and in mediating the interactions between haematopoietic cells and their progenitors in the bone marrow22.

Congenital disorders of glycosylation

Genetic defects in glycosylation are often embryonic lethal, underlying the vital role of glycans23–32; C D G s are classified as type I and type II32. Type I C D G s are caused by abnormalities in the formation of the oligosaccharide structure on the glycolipid precursor before the attachment to the Asn residue of a protein (FIG. 2). Type II CDG s involve defects in the control of the N-linked branching structure on the nascent glycoprotein30,31.

CDGs are typically severe in their manifestations, as they affect m any muscular, developmental and neurological functions (TABLE 1). In fact, these disorders were originally discovered in children with previously unexplained multi-system disorders; detection of under-glycosylated serum transferrin in the affected children led to the identification of defective glycosylation as the cause for the disease33. The test used in the diagnosis of CDGs was origin ally devised to detect alcoholism on the basis of the hyposialylation of liver-derived serum transferrin in patients with alcoholism34. In some CDGs, the defect affects a single glycosylation step or pathway, whereas in other CDG s several pathways are affected. Depending on where the defect in glycosylation occurs, CDG phenotypes can result from altered activation, presentation or transport of sugar precursors; altered expression and/or activity of glycosidases or glycosyltransferases; and altered expression and/or activity of proteins that control the glycosylation machinery or maintain the Golgi apparatus.

Table 1 |.

Selected examples of congenital disorders of glycosylation

| CDGa or syndrome | Defective gene and protein | Affected pathway | Phenotypic outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALG1-CDG | ALG1, β1,4-mannosyltransferase | N-glycan biosynthesis; ALG1 catalyses the first mannosylation step in the biosynthesis of the lipid-linked precursor oligosaccharide for N-glycosylation | Intellectual disability, hypotonia, seizures, microcephaly, infections and early death |

| B4GALT1-CDG | B4GALT1, β1,4-galactosyltrans-ferase 1 | Two alternative transcripts: one encodes a trans-Golgi-resident protein involved in glycoconjugate biosynthesis whereas the second transcript encodes a protein that forms soluble lactose synthase | Intellectual disability, developmental delay, hypotonia, macrocephaly, Dandy-Walker malformation, coagulopathy and myopathy |

| COG7-CDG | COG7, conserved oligomeric Golgi complex subunit 7 | Retrograde transport from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum; involved in multiple glycosylation pathways | Hypotonia, microcephaly, growth retardation, adducted thumbs, failure to thrive, cardiac anomalies, wrinkled skin and early death |

| MPI-CDG | MPI, mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | Conversion of fructose-6-phosphate and mannose-6-phosphate; involved in multiple glycosylation pathways | Hepatic fibrosis, coagulopathy, hypoglycaemia, protein-losing enteropathy and vomiting; no neurological symptoms |

| NGLY1-CDG | NGLY1, PNGase | NGLY1 cleaves the β-aspartyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc) of the glycan and the amide side chain of Asn, converting Asn to Asp. This process assists in proteasome-mediated degradation of misfolded glycoproteins | Intellectual disability, developmental delay, seizures, abnormal liver function and hypolacrima or alacrima |

| PMM2-CDG | PMM2, phosphomannomutase 2 | Conversion of mannose-6-phosphate to mannose-1-phosphate; involved in multiple glycosylation pathways | Intellectual disability, hypotonia, seizures, strabismus, cerebellar hypoplasia, failure to thrive and cardiomyopathy; 20% lethality in the first 5 years of life |

| SRD5A3-CDG | SRD5A3, polyprenol reductase | SDR5A3 enzyme converts polyprenol into dolichol, a key step in the synthesis of dolichol-linked monosaccharide and the oligosaccharide precursors for N-glycosylation | Intellectual disability, hypotonia, eye and brain malformations, nystagmus, hepatic dysfunction, coagulopathy and ichthyosis |

| CHIME syndrome | PIGL,GlcNAc-PI de-N-acetylase | PIGL catalyses the second step of GPI biosynthesis, de-N-acetylation of GlcNAc-PI | Coloboma, congenital heart disease, ichthyosiform dermatosis, mental retardation and ear anomalies syndrome (CHIME) |

| GNE myopathy | GNE, bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc-2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase | Biosynthesis of sialic acid | Proximal and distal muscle weakness, wasting of the upper and lower limbs and selective sparing of the quadriceps |

| Walker-Warburg syndrome | Various genes, including POMT1 and POMT2 that encode two subunits of O-mannosyltransferase | Malfunction of various enzymes that modify α-dystroglycan | Defects in muscle, brain and eye development and elevated serum creatine kinase |

CDG, congenital disorder of glycosylation; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; ManNAc, N-acetylmannosamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol.

Current recommended nomenclature for CDGs is used, XX-CDG, in which XX defines the specific affected gene.

N - glycan - related CDGs.

PMM2-CDG is caused by mutations in PMM2, which encodes phosphoman - nomutase 2 (PMM2) and is the most common form of CDG; it can present with a neurological or multi-system phenotype29,35. PMM2 converts Man −6-phosphate (Man −6-P) to M an-1-P, a precursor for the synthesis of GDP-(Dol-P-Man). In turn, these com pounds are substrates for the mannosyltransferases involved in the synthesis of the lipid-bound precursor of N-glycans, Glc3Man9GlcNAc2-P-P-D ol29,35. The type of gene mutation affects the disease severity, which ranges from an embryonic lethal defect if the enzyme is completely inactive to mild cognitive impairment if the enzyme is still partially active29,35. A long-term follow-up of 75 patients with PMM2-CDG indicated that there were no significant changes in the overall clinical severity over time and that some bio chemical variables spontaneously improved35. Although there are currently no therapeutic options for patients with PMM2-CDG, new treatment strategies that involve the use of pharmacological chaperones to rescue PMM2 loss-of-function mutations are being explored36,37. This strategy is based on the rationale that increasing the stability of mutant enzymes, which often exhibit destabilizing and oligomerization properties, would improve the enzyme activity.

MPI-CDG, the second most common CDG, is caused by mutations in MPI, which encodes M an −6-P isomerase29. This enzyme is responsible for the interconversion of M an-6-P and fructose-6-phosphate. Man-6-P can also be generated directly by hexokinase-catalysed phosphorylation of M an, a pathway that is functional in patients with MPI-CDG. Thus, M an dietary supplementation is an effective treatment for MPI-CDG and is well tolerated27,38.

O-glycan-related CDGs.

Congenital muscular dystrophies, such as Walker-Warburg syndrome and muscle-eye-brain disease, involve abnormal Man O-glycosylation, primarily on α-dystroglycan39. O-Mannosylation of α-dystroglycan and similar proteins is initiated in the ER by the attachment of Man to a Ser or Thr residue, a reaction that is catalysed by the O-mannosyltransferase complex that contains POMT1 and POMT2 enzymes24–29. The Man linked to Ser or Thr is then further modified by multiple enzymes in the Golgi apparatus to generate an elongated glycan. The resultant polymeric glycan, matriglycan, is necessary for the binding of laminin and other extracellular matrix proteins to a-dystroglycan24,29. The disruption of this interaction alters the properties of cell mem branes and leads to the development of muscular dystrophy. Clinical manifestations of α-dystroglycanopathy frequently include alterations in the central nervous system and ocular disease manifestations, in addition to muscular dystrophy.

NGLY1 deficiency.

NGLY1 deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder of the ER-associated protein degradation pathway. The level of protein loss (that is, loss of PNGase, encoded by NGLY1) correlates with neurological dysfunction, abnormal tear production and liver disease40; a nonsense mutation is associated with a particularly severe disease phenotype. PNGase is responsible for the translocation of misfolded proteins across the ER membrane into the cytosol for subsequent degradation by the proteasome41. A Drosophila model of PNGase deficiency led to the identification of various cellular processes associated with PNGase deficiency, including disruption of mitochondrial physiology, reduced cellular respiratory capacity and altered regulation of bone morphogenetic protein42–44. These new insights might lead to novel therapeutic approaches for NGLY1-CDG.

Current and future the rapies for CDG.

The design or improvement of a diagnostic test, or therapeutic option, for a CDG requires a clear understanding of its pathophysiological mechanism s. Dietary supplementation, such as M an therapy in MPI-CDG, can be very helpful as such approaches are generally inexpensive and broadly available. However, various dietary supplementation strategies have been tested in multiple CDG s and CDG disease models with varied results. Positive results were observed for dietary supplementation approaches in CAD-CDG, GNE-CDG, PGM1-CDG and SLC 35C1-CDG38. Other CDGs might benefit from a personalized medicine approach based on the identification of relevant genetic mutations in individual patients. Characterizing the underlying mechanism of a CDG at a molecular level should enable the development of new therapeutic approaches.

Glycans in immunity and inflammation

Cells of the immune system, similarly to all other cells, express cell surface-associated glycoproteins and glycolipids that, together with glycan-binding proteins and other molecules, sense environmental signals. Many immune receptors that are expressed on innate and adaptive immune cells recognize glycans found on the surface of microorganism s that are known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Examples of such glycan-containing molecules include bacterial lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, teichoic acids, capsular polysaccharides and fungal mannans. The recognition of these glycosylated microbial patterns by the immune system has been exploited for the development of vaccines45,46; pneumococcal vaccines, for example, are formulated using a mixture of capsular polysaccharides47. The recent progress in H IV-1 vaccine development has also been driven by a better understanding of the HIV-1 envelope (Env) glycoprotein and the effects of its glycan composition on immune responses and immune evasion48–53. Moreover, the interactions between endothelial cells and leukocytes, which are crucial for leukocyte trafficking and recruitment to sites of tissue injury, are controlled by adhesion molecules that are in turn regulated by cellular glycosylation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can also induce changes in cell-surface N-glycosylation of endothelial cells, suggesting that glycosylation might contribute to inflammatory vascular diseases54,55.

In the adaptive immune system, glycans also have crucial and multifaceted roles in B cell and T cell differentiation. These functions involve multiple cell-surface and secreted proteins (such as CD 43, CD 45, selectins, galectins and siglecs), different types of cell-cell interactions and the recognition of glycan-containing antigens56–58. The regulation of cellular glycosylation and its impact on the molecules that function as ligands and receptors during an inflammatory response is controlled through various mechanisms and is dependent on the inflammatory insult and its location. These mechanisms, which include ERK and p65 signalling, are critical to understanding the failure to control chronic inflammation in multiple disease states55. Immunoglobulins, for example, are crucial components of hum oral immunity, and altered glycosylation patterns of some immunoglobulin isotypes have been identified in chronic inflammatory, autoimmune and infectious diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and HIV infection59–68.

In fact, glycosylation patterns differentially affect the effector roles of immunoglobulins69–73. Below, we present several examples to illustrate various biological roles of glycans and glycan-recognizing molecules in B cell and T cell biology, including immunoglobulin effector functions.

CD43 and CD45.

The glycoproteins CD43 and CD45 are abundantly expressed on the surface of B cells and T cells and contain both O-glycans and N-glycans. Glycosylation of these proteins is modulated during cellular differentiation and activation, and regulates multiple T cell functions, including cellular migration, T cell receptor signaling, cell survival and apoptosis74,75. CD45 has an active receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase domain that interacts with Src family kinases in B cells and T cells to regulate the signalling threshold for the activation of B cell receptors (BCRs) and T cell receptors75–77. CD45 also has non-catalytic functions, for example, in modulating the function of the inhibitory co-receptor CD22 on B cells78. CD43 is involved in the multiple functions of lymphocytes and other cells of haematopoietic origin, including T cell adhesion and activation. CD43 has an elongated extracellular domain through which it interacts with multiple ligands, including ICAM1(CD54), major histocompatibility class I (MHCI), siglec1 (CD169), galectin 1 and E-selectin. Crosslinking of C D 43 with monoclonal antibodies can induce CD43 internalization, whereas phorbol ester-induced activation can lead to both protein internalization and proteolytic cleavage of the CD43 ectodomain; in T cells, CD43 shedding is linked to the regulation of apoptotic cell death79.

The glycans present in CD43 and CD45 (namely, their types, size and sites of attachment) are regulated by controlling the expression levels of specific glycosyltransferases and glycosidases. Alternative splicing of the gene that encodes CD45 creates further diversity as it enables the translation of several protein isoform s with different potential glycosylation sites74. The affinity of the interactions between glycosylated CD43 or CD45 ligands and their receptors is affected by the presence of core 2 O-glycans (that is, GlcNAcβ1 −6 (Galβ1–3) GalNAcαSer/Thr) versus core 1 O-glycans (that is, Galβ1–3GalNAcαSer/Thr); the presence of sialic acid is another important factor74.

Galectins.

Galectins are small soluble proteins that contain one or two carbohydrate-binding domains specific for galactose-containing glycans80. The members of this family of 15 carbohydrate-binding proteins are involved in m any processes in the immune system, including the regulation of T cell receptor signal strength as well as T cell and B cell death. For example, galectin 1 can induce apoptosis by binding to N-glycans or O-glycans present on C D 45 (REF81). Galectin 3 not only interacts with CD43 and CD45 but also binds to highly branched N-glycans on extracellular matrix glycoproteins such as laminin, fibronectin, vitronectin and integrin 1, thus affecting cellular adhesion80,82. In addition to binding to extracellular matrix proteins and cell-surface glycol-conjugates in a carbohydrate-dependent manner, galectins can also establish carbohydrate-independent interactions with cytosolic or nuclear targets82. Galectins interact with glycopeptides present on the cell surface through the formation of oligomers; oligomerization facilitates receptor clustering, lattice formation and cell-cell interactions. The binding affinity of galectins varies according to the type of glycan it interacts with, and changes in glycan characteristics can regulate the signals induced by galectin bin ding. For instance, the signal induced by the binding of galectin 1 to CD45 depends on several factors, including the CD45 isoform, which affects its glycosylation potential; the presence of core 2 O-glycans, which are high-affinity ligands for galectin 1; the com position of the N-glycan branching; and the extent of sialylation80. The addition of sialic acid is dependent on the relative expression of α2,6-sialyltransferases or α2,3-sialyltransferases, and the presence of α2,6-sialic acid on multi-antennary N-glycans prevents binding to galectin 1 (REF83). The multiple biological activities of galectins suggest these proteins are valuable potential therapeutic targets in inflammatory diseases and cancer; multiple galectin antagonists are currently under development84.

Siglecs.

Siglecs are sialic acid-binding proteins expressed on many cells of the immune system that perform various functions, including the regulation of antigen-specific immune responses and cell homing85. CD22 is one of 16 siglec proteins characterized in humans and is expressed on B cells, where it specifically binds a2,6-lin ked sialic acid-containing ligands; this interaction is crucial for the formation of nanoclusters in the cell mem brane that control BC R signalling following antigen binding86. Moreover, CD22 can act as a homing receptor, directing cells to tissues that express high amounts of α 2,6-linked sialic acids87. The CD22-CD22L interaction s are also essential for maintain in g self-tolerance, and CD 22-deficient m ice produce higher amounts of somatically mutated, high-affinity autoreactive IgG antibodies than wild-type controls88. Thus, it seems that CD22 is linked to the tight regulation of BCR signalling that maintains self-tolerance. Perturbations caused by CD22 deficiency might increase the likelihood of developing autoimmune diseases, and CD22 might be a therapeutic target for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as SLE89. Importantly, the success of such a therapy would require a method for targeting CD22-mediated signalling on pathogenic autoreactive B cells without compromising the responses of pathogen-specific B cells.

Another important member of the siglec family is CD169 (also known as sialoadhesin or siglec 1), a macrophage adhesion molecule that binds sialic acid linked by an α2,3 bond to Gal on N-linked and O-linked glycans and glycolipids90–92. CD169 binds to sialic acid with low affinity; therefore, its ligands must be heavily sialylated and multimeric to enable an effective interaction93. This siglec mediates cell-cell interactions and the binding of immune cells to sialic acid-containing pathogens. CD169 is also used as a marker for a specific population of macrophages that not only have key roles in the initiation of antibacterial immune responses but are also involved in the transmission of some viruses and in the development of inflammation and several autoimmune diseases90,94–96.

Selectins.

The selectin family of proteins consists of E-selectin, P-selectin and L-selectin, which are mainly expressed on endothelial cells, platelets and leukocytes, respectively; these cell adhesion molecules are critical for leukocyte rolling on the endothelium before tissue extravasation97. Selectins recognize sialylated and fuco-sylated glycans but can also bind a subset of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans98. The finding that inhibition of selectin restored blood flow in a mouse model of sickle cell disease led to a trial of a small-molecule inhibitor of P-selectins and L-selectins, GMI 1070, in patients with sickle cell anaemia; the inhibitor reduced selectin-mediated cell adhesion and abrogated vascular occlusion and ‘sickle cell crisis’99. Another study demonstrated that inclacumab, a recombinant monoclonal antibody against P-selectin, reduces myocardial damage after a percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction100. These examples demonstrate that targeting selectins may be beneficial in some inflammatory diseases.

Immunoglobulin glycosylation.

Immunoglobulin isotypes differ in the number of N-glycans present on their heavy chains62,64,66,73. Some immunoglobulins, such as IgA1 and IgD, also contain O-glycans, which are usually clustered in the hinge-region segments of these antibodies101,102. Immunoglobulin glycans impact the effector functions of antibodies depending on the b ranching of N-glycans and/or the term in al sugars of N-glycans or O-glycans, which include galactose and sialic acid. In fact, immunoglobulin glycosylation can determine whether an antibody glycoform is pro-inflammatory, such as IgG with galactose-deficient N-glycans, or anti-inflammatory, such as IgG with sialylated N-glycans.

All four human IgG subclasses have two variable biantennary glycans in their crystallizable fragment (Fc) region, attached at the conserved Asn297 site (FIG. 3a). Certain glycoforms of IgG, such as those deficient in sialic acid and galactose (Fig. 3b), are particularly abundant in some chronic diseases such as RA, SLE, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), H IV and mycobacterial infections59–65; IgG1 galactose deficiency was also found in individuals with parasitic infection or asthma using population-wide immune activation studies66. Biochemical and immunological studies, as well as genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have identified specific genes, enzymes and pathways associated with the production of galactose-deficient IgG molecules; these include β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1, cytokine-signalling adaptor gp 130 and T helper 17 (TH17) cell-dependent pathways67,68. IgG glycoengineering in vitro69 and in vivo70 confirmed the pathogenicity of IgGs with galactose-deficient (and therefore, also sialic acid-deficient) N-glycans. Conversely, sialylation of pathogenic IgG autoantibodies attenuated their pathogenic activity (Fig. 3c). In fact, N-glycosylation of the Fc region of IgG modulates its effector functions as it affects the binding efficiency of Fcγ recep tors (FcγR s)103–105. On the basis of these and other findings, glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been used to produce therapeutic IgGs with tailored activity, such as sialylated IgG with anti-inflammatory properties71–73.

Fig. 3 |. Functional impact of variable Igg Fc glycan composition.

a | Immunoglobulin G (IgG) has two heavy and two light chains, and its crystallizable fragment (Fc) region can bind to Fcγ receptors and some proteins of the complement system. The IgG Fc region contains two N-glycans, one per heavy chain, attached at Asn297; these glycans contribute to the structural integrity of the Fc region and to its interactions with Fc receptors and complement. The Fc glycans in the IgG molecule are biantennary glycans with variable content of fucose (Fuc), bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), galactose (Gal) and sialic acid; most IgG molecules are fucosylated. The glycan composition of IgG affects its biological activity; for example, Gal-deficient IgG glycoforms, which have been associated with chronic inflammatory diseases, can activate the lectin complement pathway. b | IgG glycoforms with Gal-deficient glycans are pro-inflammatory. c | IgG glycoforms with sialylated glycans are considered to be anti-inflammatory. Man, mannose.

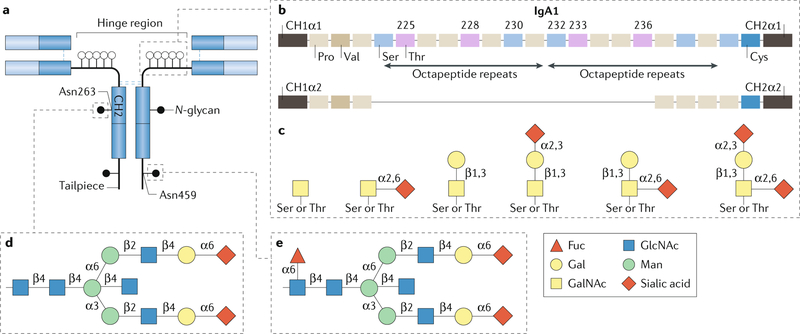

Human IgA exists in two subclasses, IgA1 and IgA2. Both subclasses have several N-glycans in the Fc region, but IgA1 typically also has a cluster of 3–6 O-glycans in the hinge region (Fig. 4). IgA and IgM are found in the circulation and in mucosal secretions. Circulating IgA is predominantly monomeric IgA1 (~90%), whereas the remaining IgA is polymeric and consists of two or more monomers connected by a J chain. Secretory IgA is polymeric and includes the secretory component, a heavily N-glycosylated polypeptide that is derived from the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor and is added to IgA during transcytosis through mucosal epithelial cells106. IgA glycans have multiple biological roles, including glycan-mediated antigen-nonspecific binding to bacteria102,107. IgA1 has core 1 O-glycans (that is, GalNAc with β1,3-linked galactose), but in some diseases, including IgA nephropathy (IgAN), patients have elevated circulatory IgA1 with galactose-deficient O-glycans108.

Fig. 4 |. Structure and glycosylation of human IgA.

Human immunoglobulin A (IgA) occurs in two subclasses, IgA1 and IgA2. a | The amino acid sequence is very similar for both subclasses, but the IgA1 heavy chain contains additional amino acids in the hinge region. Each heavy chain of IgA1 also contains two N-glycans, one in the CH2 domain (Asn263) and one in the tailpiece (Asn459). Although human IgA2 does not contain O-glycans, it can have more N-glycans per heavy chain than IgA1. b | The IgA1 hinge region is composed of two octapeptide repeats, which include nine Ser and Thr residues that are potential O-glycosylation sites; usually 3–6 of these residues are O-glycosylated and the most common IgA1 glycoforms have 4–5 O-glycans in the hinge region. c | The O-glycan composition of normal circulating human IgA1 is variable but usually consists of a core 1 disaccharide structure with N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) in β1,3-linkage with galactose (Gal); each of these monosaccharides can be sialylated. d | The CH2 site of N-glycosylation contains digalactosylated biantennary glycans with or without a bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), but it is not usually fucosylated. e | By contrast, the tailpiece N-glycosylation site contains fucosylated glycans. Fuc, fucose; Man, mannose.

Glycosylation in cancer

Mechanisms.

Tumour growth depends on the ability of cancer cells to bypass cellular division checkpoints, evade death signals and immune surveillance and migrate to metastatic sites; glycosylation has a role in all of these processes. For example, abnormal growth factor signalling is a critical component of cancer development that can be controlled by the specific glycosylation motifs on the relevant ligands, receptors and molecular scaffolding109. Glycosylation patterns were one of the first biomarkers of cancer and continue to be used to identify cells with stem-cell-like phenotypes, both within cancer and in healthy tissue110–112. Glycosylation changes that are often observed in cancer cells include an increase in sialyl Lewis structures, abnormal core fucosylation, increased N-glycan branching or exposure of the mucin-type O-glycan, Tn antigen. Many of these altered glycosylation patterns found in cancer have been termed ‘oncofetal’ as they resemble patterns often seen in early development113,114. As cancer cells evolve through multiple stages of disease, glycan composition can change in parallel with changes in cellular metabolism. This phenomenon includes incomplete synthesis, which refers to truncated glycosylation that produces the Tn antigen in O-glycans, and neo-synthesis, which produces abnormal glycosylation patterns such as sialyl Lewis X. These glyco-neoantigens, normally reserved for lymphocyte extravasation from the blood, are commonly found in cancer cells and facilitate metastatic spread115,116.

The number of studies concerning the functional implications of altered glycosylation in cancer has increased over the past decade, but the field still lacks good mechanistic studies of the processes that lead to cancer-associated changes in glycosylation. Proteins from the epidermal growth factor receptor family have both O-glycosylation and N-glycosylation sites that are modified in many types of cancer through altered expression of glycosyltransferase enzymes, such as polypeptide GALNT3 and Gal 3(4)-L-fucosyltransferase (FUT3). Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB2 (also known as HER2) is overexpressed in a number of cancers, including prostate, breast and gastric cancers, and its functional properties are modulated through a range of complex post-translational modifications, including glycosylation117,118. Loss of GALNT3 can lead to increased production of pro-growth and pro-metastatic carbohydrate antigens, such as T and Tn antigens on HER2, whereas suppression of FUT3 can have an anti-metastatic and growth-suppressing effect by preventing Lewis Y antigen (LeY) production on HER2 (refs119,120). In addition, HER2 can also be regulated through glycoprotein GalNAc 3β-galactosyltransferase 1 (C1GalT1) activity, as increased mucin-type O-glycosylation enhances galectin 4 binding, which leads to HER2 activation118,121. Abnormal promoter region methylation in some glycosyltransferase genes, such as GALNT3, can also lead to aberrant enzyme expression122.

Currently, there is a dearth of studies in the cancer field that assess the intracellular mechanisms that drive changes in expression and activity of specific glycosyltransferases with respect to their targets. An exception is mucin 1 (MUC1), one of the most studied glycoconjugates in the cancer field, partly owing to its increased expression and altered glycan composition in many adenocarcinomas, and partly owing to its use as a cancer-vaccine antigen123–125. MUC1 contains a large extracellular domain (that is, the mucin domain) with five potential O-glycosylation sites in each of its multiple repeats that consist of ~20 amino acid residues. Studies of glycosyltransferase enzymes implicated the dysregulation of several enzymes in altering O-glycosylation of MUC1, including C1GalT1, β-galactoside α−2,3-sialyltransferase 1 (ST3GalI) and α-GalNAc α−2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6GalNAcI); altered localization of GALNTs in the ER also has a role in changing MUC1 glycosylation126–129. GALNTs typically initiate O-glycosylation in the Golgi apparatus, but in cell-culture models these enzymes can translocate to the ER via a process that involves aberrant Src signalling, leading to an increased density of O-glycosylation of MUC1 repeats128,130; MUC1 produced by cancer cells also exhibits increased sialyl-Tn antigen129,131,132. In addition, altered glycosylation motifs on MUC1 can affect cancer immune surveillance, typically through co-opting cell-surface lectins such as CD169, which enhances macrophage activation after binding to sialylated MUC1 and promotes tumour growth133–135.

The glycosylation of specific proteins in serum and/or tumour tissues can be used as a diagnostic biomarker and to assess patient prognosis and responses to treatment; examples of such glycoproteins include CEA, MUC1, MUC16 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA)136–141. Carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9) is detected with a specific mouse monoclonal antibody that recognizes the sialyl Lewis A (sLea) carbohydrate motif (that is, Neu5Acα2,3Galβ1,3(Fucα1,4)GlcNAcβ1-R) on a monosialoganglioside first identified in gastrointestinal cancer142. Synthesis of this sLea antigen is controlled by Lewis, a gene involved in ABO(H) blood-group determinants143 (Box 1). CA19–9 is often, but not always, elevated in the serum of patients with a variety of cancers, including pancreatic, gastric and colorectal cancers; the mechanisms that lead to this increase in serum levels in cancer are poorly understood, but it seems to be associated with dysregulated sialyltransferases, such as Gal-β−1,3-GalNAc-α−2,3-sialyltransferase 2 and 4 (ST3GalII and ST3GalIV, respectively)144. The presence of CA19–9 across multiple cancers highlights abnormal glycosylation as a fundamental feature of cancer pathobiology136,143.

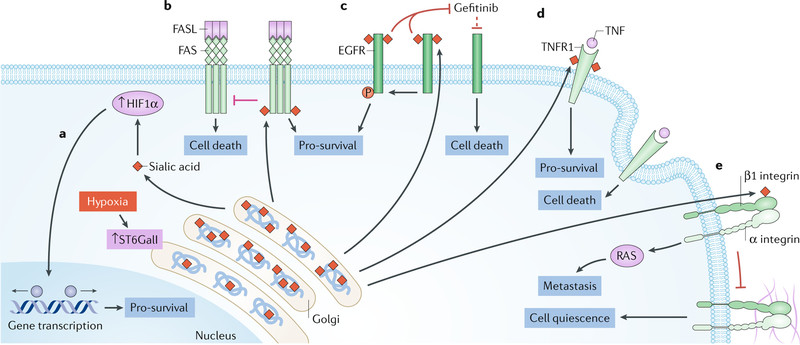

Another important glycosylation pattern is the α2,6-linked sialic acid in N-glycans, which is commonly elevated in pancreatic and colon cancers and has pro-tumour effects; this sialic acid is added to the glycan backbone by β-Gal α−2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6GalI), also upregulated in these cancers145–147 (Fig. 5). Increased expression of ST6GalI is associated with pro-survival pathways, and its sialylated products can inhibit tumour cell apoptosis and activate growth factor pathways110,111,148–150.

Fig. 5 |. ST6galI and abnormal sialylation in cancer.

N-glycans with terminal α2,6-sialylation are synthesized by the β-galactoside α−2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6GalI). Both upregulation of ST6GalI and increase in α2,6-sialylation are observed in many types of cancers and are associated with negative patient outcomes. In fact, α2,6-sialylation is involved in the regulation of many key proteins that are known to contribute to cell survival and metastasis in cancer. a | Hypoxia increases the expression and activity of ST6GalI, leading to enhanced α2,6-sialylation; in turn, increased sialylation upregulates HIF1α and the expression of pro-survival HIF1α target genes, such as growth factors and glucose transporters. b | The death receptor FAS, also known as CD95, is a target of ST6GalI, and its sialylation inhibits the initiation of apoptotic signalling and subsequent receptor internalization. Increased expression of ST6GalI prevents FAS ligand (FASL)-induced apoptosis through FAS. c | Increased expression of ST6GalI in cancer cell lines enhances the α2,6-sialylation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which increases its tyrosine kinase activity and the phosphorylation of its targets279. α2,6-Sialylation enhances the activity of EGFR, both at baseline and after cell activation, and leads to increased activation of pro-growth and survival genes. Moreover, cells in which ST6GalI is overexpressed, leading to enhanced α2,6-sialylation, are protected against cell death induced by the anticancer drug gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor. d | In cells with low ST6GalI expression and reduced α2,6 sialylation, prolonged activation of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 (TNFR1) by TNF leads to receptor internalization, caspase activation and cell death. This apoptotic cell death pathway is prevented by enhanced α2,6-sialylation of TNFR. e | α2,6-Sialylation of β1 integrin in the Golgi apparatus by ST6GalI results in hypersialylation, which inhibits β1 integrin binding to matrix proteins such as type I collagen and fibronectin and prevents downstream signalling. These signals maintain cell quiescence, and their disruption due to enhanced sialylation leads to increased cell motility and invasion, which promotes cancer cell metastasis.

Glycome profiles.

Although the use of a single biomarker for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression is an attractive prospect, research shows that whole glycome profiles might be better than a single glycosylation pattern for the assessment of disease progression. In one study, glycome profiling of prostate cancer biopsy samples enabled the identification of indolent versus metastatic disease with 91% accuracy; conventional assessment was 72% accurate151. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) of hepatocellular carcinoma biopsy samples identified increases in fucosylation across a panel of N-glycosylation structures in 95% of patients; the specific glycome profiles correlated with median patient survival time152. Transcriptional analysis of melanoma biopsy samples indicated that expression of β1, 6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (GCNT2) in these samples was decreased compared with those of healthy epidermal melanocytes. This decrease led to a decrease in Asn-linked I-branched glycans (that is, glycans that have additional GlcNAc-Gal branches, also termed ‘adult I’ blood-group antigen), a novel marker of metastatic melanoma progression153. Collectively, these studies highlight the advantages of whole glycome profiling over the detection of traditional single markers of glycosylation in cancer.

Xenotransplantation

The major bottleneck for organ transplantation continues to be the shortage of available viable organs. Xenotransplantation (for example, from pig donors) is a proposed solution for this problem154 but it has been hindered by several factors, including the presence of donor carbohydrate antigens that are not present in humans and can trigger immune rejection. Examples of such antigens include the Gal-α(1,3)-Gal epitope present on glycoproteins and glycolipids and N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc).

The Gal-α(1,3)-Gal epitope is synthesized by an α1,3-galactosyltransferase in New World primates and many non-primate mammals. However, the gene that encodes this enzyme, GGTA1, is inactivated in humans and Old World primates, which leads to the production of antibodies that recognize Gal-α(1,3)-Gal-containing glycoconjugates155. It is thought that these antibodies are induced by Gal-α(1,3)-Gal-containing compounds present in the microbiota and from dietary sources. The antibodies bind to vascular Gal-α(1,3)-Gal antigens of xenotransplants and induce complement-mediated endothelial cell cytotoxicity that results in graft rejection156. Importantly, deletion of GGTA1 from the pig genome revealed the presence of additional endothelial cell xenoantigens that could contribute to graft rejection156.

Neu5Gc is another relevant xenoantigen, and it is synthesized by CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase. This enzyme is present in most mammals, including pigs, but it is inactive in humans, although Neu5Gc can be obtained from dietary sources and metabolically incorporated into many human glycoconjugates157,158. Neu5Gc, also termed Haganutzui–Deicher antigen, has been identified as the antigen in horse serum that causes serum sickness in humans159. A third example of an important xenoantigen found in pig tissues is terminal GalNAc, also known as the SDa blood-group antigen, which is synthesized by β1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2, encoded by B4GALNT2. Although SDa is expressed in various human cells, anti-SDa IgM is commonly detected in human serum160.

It is hoped that modern approaches based on CRISPR–Cas-mediated gene editing might be used to remove these xenoantigens and aid the development of animal tissues and organs that are suitable for transplantation in humans155,157.

Autoimmunity and chronic inflammation

The immune system routinely recognizes and responds to foreign carbohydrate epitopes, such as lipopolysaccharides; however, loss of tolerance and autoimmunity might also occur, for example, if the glycosylation patterns of the host and the pathogen overlap, perhaps owing to abnormal enzymatic activity. Changes in the glycosylation patterns of proteins can also result in immune detection of these neo-glycan epitopes and lead to autoimmunity. In addition, IgG effector functions are controlled by N-glycosylation. Altered sialylation, galactosylation and/or fucosylation, as well as changes in glycan composition, can contribute to immune dysregulation and a range of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases.

Rheumatoid arthritis.

RA is an autoimmune disease that results in chronic inflammation of joints and other associated tissues; it is characterized by the presence of serum rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies161. Early studies of collagenous tissues from patients with RA found considerable immune aggregates consisting of IgG and IgA162. Moreover, IgG from patients with RA has overall and site-specific changes in glycosylation that affect the composition of Fc-associated and antigen-binding fragment (Fab)-associated glycans. In addition to an increased proportion of Gal-deficient Fc glycans, Fab-portion glycans contain high amounts of bisecting GlcNAc and core fucose163. Changes in the glycosylation of antigen-specific IgGs precede disease onset, and the degree of these changes correlates with disease severity164,165. Altogether, these findings suggest that changes in the glycosylation of IgG are a critical component of RA pathogenesis.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

IBD refers to chronic inflammatory diseases that affect the gastrointestinal tract and includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. In IBD, both decreased secretion of mucins and structural changes to mucins themselves can occur; the mucins of the gastrointestinal tract form a physical barrier between the intestinal microbiota and the intestinal epithelium166. Chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract is thought to involve gut microbiota-induced changes in the glycosylation patterns of the host that result in enhanced entry of bacteria or dietary lectins into the host tissue167–170. This process leads to increased inflammation that can lead to ulcer development and cancer171. In addition to potential changes in glycosylation associated with alterations in gut mucosa and the epithelium, changes in N-glycosylation of IgG are also observed. Patients with IBD have decreased galactosylation of IgG N-glycans, and the extent of under-galactosylation correlates with disease severity60. Specific changes in antibody glycosylation could be used to discriminate between patients with ulcerative colitis and those with Crohn’s disease172.

Systemic lupus erythematosus.

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the presence of polyreactive autoantibodies that bind to different host targets, including proteins, nucleic acids and their complexes. Similarly to other autoimmune diseases, reduced galactosylation and sialylation of IgG are associated with SLE63,173. Furthermore, a decrease in core fucosylation and an increase in bisecting GlcNAc of N-glycans is observed. Together, these findings show that alterations in the IgG glycome in SLE limit the negative feedback loops that rely on complete IgG glycosylation and promote an inflammatory glycan profile. It is unknown whether the changes in glycosylation of IgG associated with SLE correlate with a loss of B cell tolerance and the production of autoreactive antibodies. Interestingly, treatment with sialylated IgG protected against disease symptoms in a mouse model of SLE174.

Tn syndrome.

Originally called permanent mixed-field polyagglutinability, Tn syndrome is a rare blood disorder characterized by the presence of Tn antigens on all haematopoietic cell lineages175. In this syndrome, the Tn antigen-containing glycoconjugates are recognized by IgM antibodies, which leads to varying degrees of anaemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia in affected patients. Tn syndrome is a disorder of O-glycosylation in which Tn antigen is over-represented owing to a decrease in the galactosylation of terminal GalNAc by C1GalT1. This syndrome is an acquired and permanent disease that can occur in males and females at any age175 and results from a clonal somatic mutation in COSMC (also known as C1GALT1C1), which encodes a molecular chaperone specific for C1GalT1 (refs176,177). Mutations in COSMC reduce the amount of active C1GalT1, thus decreasing GalNAc galactosylation.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly called Wegener granulomatosis) often have circulating IgG anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), typically specific for proteinase 3; these antibodies are thought to activate resident and/or infiltrating macrophages in the vasculature, leading to inflammation. GPA affects small-to-medium-sized blood vessels; therefore, the lung and kidney are particularly vulnerable to macrophage-mediated damage. Several studies reported that abnormal glycosylation of the IgG Fc region (namely, low galactosylation and sialylation) correlates with driving the enhanced macrophage activation. Anti-proteinase 3 IgG antibodies, which are significantly elevated in patients with GPA, are less sialylated than IgG from healthy individuals178–180. These hyposialylated autoantibodies lead to enhanced macrophage activation when compared with antibodies with normal sialylation, and increased levels of hyposialylated autoantibodies are associated with disease activity178–181.

IgA nephropathy.

IgAN is a unique autoimmune disease in which the autoantigen is an antibody itself — specifically, IgA1 antibodies that contain galactose-deficient O-glycans and terminal GalNAc182 (Fig. 6). GWAS183,184 and biochemical studies185,186 identified an association between several glycosyltransferases, and related proteins, with galactose deficiency of IgA1 in IgAN. In fact, patients with IgAN have elevated levels of serum IgA1 with altered mucin-type O-glycans in the hinge region; serum levels of galactose-deficient IgA1 and the corresponding autoantibodies are predictive of disease progression182 (Figs 4,6). Disease pathogenesis is not completely understood but is thought to involve altered expression and activity of key enzymes in IgA1-secreting cells, which, in genetically susceptible individuals, lead to the production of IgG autoantibodies. Consequently, circulating immune complexes form in blood, some of which deposit in the mesangium and activate mesangial cells, leading to renal injury; approximately half of patients with IgAN progress to end-stage renal disease182 (Fig. 6).

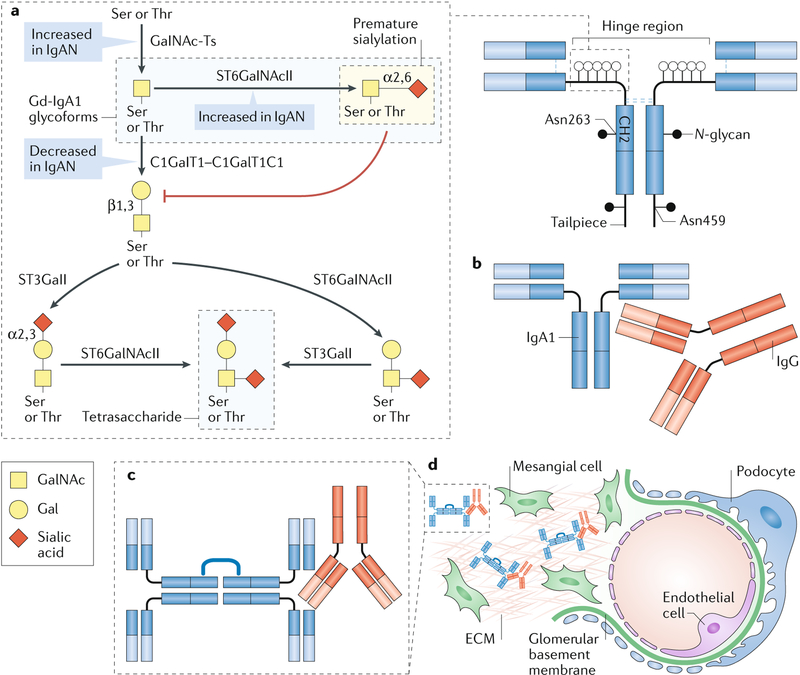

Fig. 6 |. Aberrant O-glycosylation in IgA nephropathy.

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy (IgAN) is an autoimmune disease that is thought to result from a four-hit process. a | Hit 1: increased production of circulating galactose (Gal)-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1), in which some O-glycans do not contain Gal. The first step in the glycosylation of the hinge region of IgA1 is the addition of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) to Ser or Thr residues by a GalNAc-transferase (GalNAc-T) to form the terminal GalNAc (Tn) antigen. Premature sialylation of the terminal GalNAc by α-GalNAc α−2, 6-sialyltransferase 2 (ST6GalNAcII) can block subsequent glycosylation; however, most often GalNAc is galactosylated by the glycosyltransferase GalNAc 3β-galactosyltransferase 1 (C1GalT1). The chaperone C1GalT1C1 is required for appropriate expression and function of C1GalT1. After galactosylation, GalNAc, Gal or both sugars may be sialylated; ST6GalNAcII adds sialic acid to GalNAc and β-galactoside α−2,3-sialyltransferase 1 (ST3GalI) sialylates Gal; the largest glycan of circulatory IgA1 is a tetrasaccharide. In many patients with IgAN, the number of O-glycosylated residues in the hinge region of IgGA1 is also increased82,83. Increased initiation of glycosylation by GalNAc-Ts, premature sialylation of GalNAc by ST6GalNAcII and decreased galactosylation by C1GalT1 might each contribute to the formation of Gd-IgA1, the key autoantigen in IgAN. b | Hit 2: production of IgG autoantibodies that are specific for Gd-IgA1. c | Hit 3: formation of circulating Gd-IgA1–IgG immune complexes. For simplicity, IgA1 is shown as a dimer; IgA1 monomers are the main circulating molecular form, but polymeric IgA1 is the predominant molecular form of Gd-IgA1 in the circulation. d | Hit 4: glomerular deposition of immune complexes. Other serum proteins, such as complement, are likely to be involved in the formation of the pathogenic immune complexes that are deposited in the glomeruli, activate resident mesangial cells and cause renal injury. ECM, extracellular matrix.

In IgAN, several factors might contribute to increased levels of Tn and sialylated Tn (sTn) antigens on IgA1, including decreased expression of C1GalT1 or C1GalT1C1 as well as increased expression of ST6GalNAcII, leading to premature sialylation of GalNAc185 (Fig. 6). Alternatively, changes in the activity of GALNTs might alter the sites and/or densities of initial GalNAc attachment and thereby contribute to the formation of Tn and sTn antigens. Technological advances in glycoconjugate analysis have enabled researchers to recognize that there is restricted heterogeneity in the glycosylation pattern of the IgA1 hinge region, which not only varies between patients but can also vary within individuals187 (Box 2; Supplementary Table 2). Together, these mechanisms demonstrate the critical role of correct glycan composition during glycoprotein production and demonstrate that altered glycosylation can result in the presentation of glycan autoantigens and the onset of autoimmunity.

Box 2 |. Techniques for glycoconjugate analysis.

Over the past two decades, many different technologies have been developed for the analyses of glycans and glycoconjugates. Many of the initial glycan analyses were carried out using lectins that recognize a specific glycan or glycans, often combined with pretreatment with glycosidases to selectively remove monosaccharide residues or larger components of extended glycoconjugates. For more detailed analysis, mass spectrometric techniques are now commonly used for global and individual molecular analyses. The advent of chemo-enzymatic techniques for the synthesis of glycans has driven the more widespread use of glycan array technologies that enable the simultaneous screening of hundreds of individual glycan structures. Improved glycan synthesis has also enabled the development of glycan-specific antibodies, which have become more readily available. Standard ‘-omics’ technologies have been applied to the study of patterns of gene expression and levels of glycan synthetic enzymes to help identify novel clinical disorders that involve altered glycans. In terms of 3D structural analysis of glycans, NMR has been used heavily throughout the years as a means of understanding the shape of glycoconjugates in solution; molecular dynamics simulations have complemented these structural analyses by modelling glycans on protein structures. There are now many different techniques at the disposal of researchers for the analysis of glycoconjugates. Supplementary Table 2 provides a list of methodologies used for the analysis of glycoconjugates, examples of the techniques and reagents used, and referenced examples of how these methods have been applied in biomedical research.

Diabetes mellitus.

Diabetes mellitus is commonly characterized by excess glucose in the blood, which predictably leads to various glycosylation abnormalities in patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The most widely used marker for monitoring the long-term management of diabetes is glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), which is a surrogate for the average blood glucose levels in the previous 3 months188–190. Non-enzymatic glycosylation (also known as glycation) based on reactions between haemoglobin and glucose can produce multiple glycoforms, but, in the case of HbA1c, it requires a multistep reaction between the amino-terminal Asp on the haemoglobin β-chain and a condensation reaction at the 1-hydroxyl of the glucose molecule followed by an Amadori rearrangement191–193. A similar non-enzymatic glycosylation process produces advanced glycation end products, which are glycated proteins and lipids that are elevated in diabetes and are linked to disease pathology194,195.

O-GlcNAc glycosylation has an important role in many cellular control mechanisms in general and in diabetes specifically, including the cellular response to insulin196; it is catalysed by OGT, which adds GlcNAc to Ser and/or Thr residues197–199. OGT uses UDP-GlcNAc as a substrate, which is a product of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway. This pathway functions in part as a glucose sensor and regulates cellular responses to insulin by controlling the levels of UDP-GlcNAc-mediated glycosylation of targets related to insulin activity200,201. The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway is highly responsive to glucose levels, and its flux is significantly increased in some tissues of patients with diabetes, leading to increased levels of UDP-GlcNAc and, thus, elevated O-GlcNAc glycosylation202–204. For example, O-GlcNAc glycosylation of the transcription factor NeuroD1 is crucial for its nuclear translocation, which leads to insulin production by pancreatic β-cells in response to high glucose levels205. Long-term exposure to high glucose increases O-GlcNAc modifications and, thus, its biological effects; in the context of diabetes, increased O-GlcNAc glycosylation of proteins, such as AKT, can lead to enhanced β-cell death206,207.

Cardiomyocytes can be damaged by high blood glucose levels, leading to the high rates of systolic or diastolic dysfunction in patients with diabetes (~16.9%)208; in animal models of diabetes, contractility deficits in the heart are associated with O-GlcNAc glycosylation levels209. In a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes, ventricular arrhythmias were associated with O-GlcNAc modification of the sodium channel protein type 5 subunit-α (HH1). Decreasing O-GlcNAc addition to HH1 during high-glucose stress improved the function of this sodium channel210. In addition, using an adenovirus injection to the heart to increase the expression of protein OGA, the enzyme that removes O-GlcNAc adducts, improved cardiomyocyte contractility and decreased O-GlcNAc-protein levels in the same model of diabetes211. However, in a model of myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury, decreased O-GlcNAc-protein levels were associated with increased infarct size in diabetic mice when compared with controls. Recovery of O-GlcNAc levels via miR-24 activation of OGT prevented the increase in infarct size in diabetic mice212. In the context of cardiac function, appropriate regulation of O-GlcNAc glycosylation is crucial as, depending on the cardiac insult, glycosylation that is either increased by OGT or reduced by OGA might be beneficial.

N-glycosylation defects can also cause diabetes, as demonstrated by a mouse model in which inactive N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-IVa (GnT-IVa) led to impaired insulin release and hyperglycemia213. A mass spectrometric analysis of glycosylated proteins in the kidneys of two mouse models of diabetes, caused by leptin receptor-deficiency (db/db) or by administration of streptozotocin, showed significant differences in general protein N-glycosylation between diabetic mice and healthy controls, with some similarities between the two models of disease214. Another study of serum samples from 818 patients with diabetic kidney disease reported that HbA1c positively correlated with the degree of complex and branched N-glycan content on IgG215. In addition, hyposialylated IgG, which is often present in the serum of patients with type 2 diabetes216, activates endothelial FcγRIIb, which leads to insulin resistance in obese mice. Further studies are required to understand the mechanisms underlying N-glycosylation changes in diabetes.

Glycans and glomerular filtration

Glycans have many roles in physiological kidney function, including several major roles in glomerular filtration. The most relevant glycoconjugates are found in the glycocalyx of the fenestrated glomerular endothelial cells, in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), formed by extracellular matrix proteins, and in the podocyte slit diaphragm (Fig. 7).

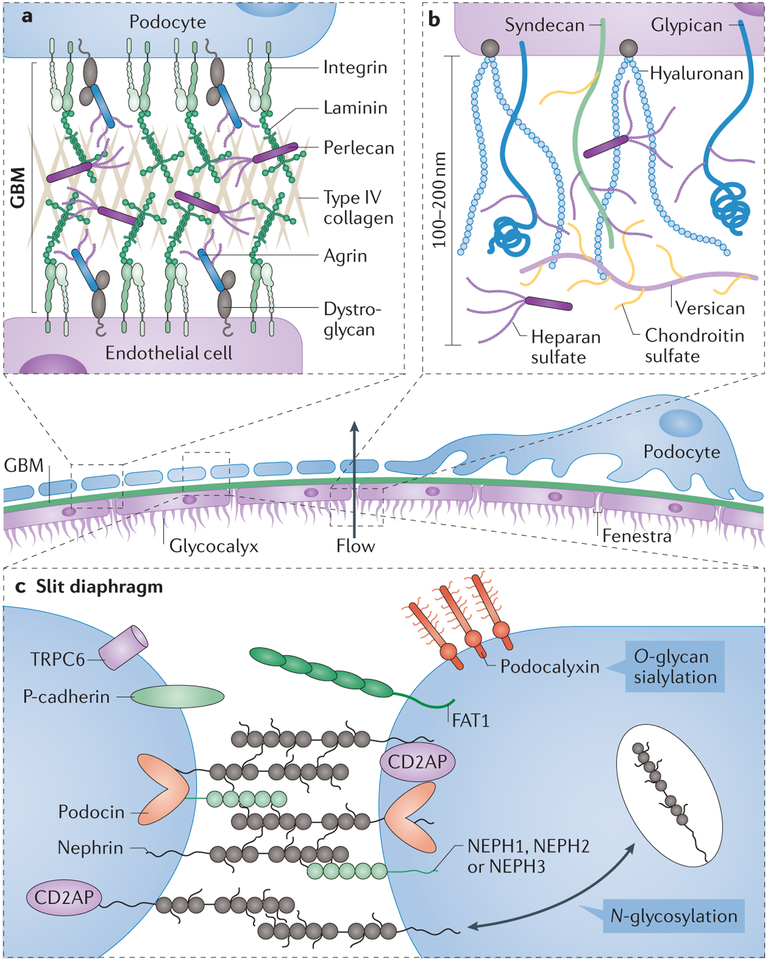

Fig. 7 |. Glycoconjugates and glomerular filtration.

Glomerular filtration occurs in the glomerulus, and endothelial cells and podocytes are the principal cells involved in this process. Mesangial cells have a key role in maintaining and supporting the endothelial and podocyte glomerular filtration barrier, in part through the production of extracellular matrix proteins, and in regulating blood pressure. a | The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is found at the interface between endothelial cells and podocytes; the GBM contains a network of type IV collagen, negatively charged heparan sulfate proteoglycans, laminins and several other extracellular matrix proteins280. Loss of proteoglycans that contain heparan sulfate, such as agrin or perlecan, occurs in some glomerular diseases, including minimal change disease and membranous nephropathy. Glycosylation of membrane-associated α-dystroglycan has an important role in the interaction between the cells that line the GBM and the extracellular matrix through its interaction with laminin. b | The endothelial glycocalyx extends far from the plasma membrane of the glomerular endothelial cells, creating a physical barrier of glycoproteins, glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans across the fenestrae. The glycan components of the glycocalyx have a key role in maintaining its mechanical and structural integrity and enabling its proper function as part of the glomerular filtration unit. Hyaluronan extends from the cell surface, whereas chondroitin sulfate and heparin sulfate are attached to extracellular matrix proteins, such as versican and perlecan, or membrane proteins such as syndecan and glypican. Together, these molecules make a dense negatively charged glycocalyx. c | The structure of the slit diaphragm, the key component of the glomerular molecular filter, relies heavily on the cell-surface adhesion protein nephrin; appropriate N-glycosylation of nephrin is critical for its surface expression and function. Sialylation of the cell-surface sialoglycoprotein podocalyxin also has a key role in podocyte morphogenesis and structural integrity. Many other cell-surface glycoproteins are involved in the formation of the slit diaphragm, including P-cadherin, podocin, nephrin-like proteins 1–3 (NEPH1–NEPH3), protocadherin fat 1 (FAT1) and transient receptor protein 6 (TRPC6). CD2-associated protein (CD2AP) is an adaptor molecule that can bind to the cytoplasmic domain of nephrin.

The first barrier that blood encounters in the glomeruli is the fenestrated endothelium, which determines the glomerular filtration rate217,218. The fenestrated endothelium also acts as a crucial barrier that prevents proteins from entering Bowman’s space; however, the pore size of the fenestrated endothelium cannot alone prevent albumin and other macromolecules from entering Bowman’s space217,218. Rather, the endothelial glycocalyx, which covers the endothelial fenestrae, probably contributes to the high permselectivity of glomeruli219. The glycocalyx is composed of negatively charged glycoproteins, glycosaminoglycans and membrane-associated and secreted proteoglycans that form an interlinking network of proteins and glycans.

One of the most evident roles of glycans in renal function relates to the formation and maintenance of the GBM, which connects the basal lamina of the fenestrated endothelial cells to the foot processes of podocytes. The GBM consists of three layers: the lamina rara interna, which is adjacent to the endothelial cells and is composed of negatively charged heparan sulfate proteoglycans; the lamina densa, a dark central zone composed of collagen IV and laminin; and the lamina rara externa, adjacent to podocyte foot processes and composed of heparan sulfate proteoglycans. The heavily sulfated glycans of proteoglycans, such as agrin and perlecan, are responsible for the negative charge of the GBM, which may have a role in regulating complement activation in the glomeruli220. Loss of heparan sulfate chains from agrin is observed in several glomerulopathies, including lupus nephritis, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease and diabetic kidney disease, suggesting a prominent role for heparan sulfate in GBM function221. Although multiple mechanisms might account for this decrease in heparan sulfate, increased activity of heparanase, an endo-β(1–4)-D-glucuronidase that degrades heparan sulfate, has been observed in both rodent models and patients with diabetic kidney disease, minimal change disease, membranous nephropathy and IgAN222,223; heparanase treatment dramatically increases the permeability of the GBM224. In addition to heparan sulfate, O-mannosyl glycans of α-dystroglycan mediate the interface between podocyte foot processes and the GBM through direct interactions with agrin and laminin 11 (ref.225). Deglycosylated α-dystroglycan can no longer bind agrin, which might lead to the detachment of podocytes from the GBM and impaired glomerular filtration in vivo226.