Abstract

Traditionally, precision medicine involves classifying patients to identify subpopulations that respond favorably to specific therapeutics. We pose precision medicine as a dynamic feedback control problem, where treatment administered to a patient is guided by measurements taken during the course of treatment. We consider sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which dysregulation of the immune system causes tissue damage. We leverage an existing simulation of the innate immune response to infection and apply deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to discover an adaptive personalized treatment policy that specifies effective multicytokine therapy to simulated sepsis patients based on systemic measurements. The learned policy achieves a dramatic reduction in mortality rate over a set of 500 simulated patients relative to standalone antibiotic therapy. Advantages of our approach are threefold: (1) the use of simulation allows exploring therapeutic strategies beyond clinical practice and available data, (2) advances in DRL accommodate learning complex therapeutic strategies for complex biological systems, and (3) optimized treatments respond to a patient's individual disease progression over time, therefore, capturing both differences across patients and the inherent randomness of disease progression within a single patient. We hope that this work motivates both considering adaptive personalized multicytokine mediation therapy for sepsis and exploiting simulation with DRL for precision medicine more broadly.

Keywords: agent-based model, deep reinforcement learning, precision medicine, sepsis.

1. Introduction

Precision medicine, as defined by the National Research Council, refers to the “ability to classify individuals into subpopulations that differ in their susceptibility to a particular disease, in the biology and/or prognosis of those diseases they may develop, or in their response to a specific treatment.” Given a specific patient's class, “preventive or therapeutic interventions can then be concentrated on those who will benefit, sparing expense and side effects for those who will not” (National Research Council, 2011). In this work, we pose precision medicine as a dynamic feedback control problem, in which patient measurements during the course of treatment are used to inform future treatment. From a computational standpoint, this changes the problem formulation from classification to optimal control.

We apply the optimal control perspective to sepsis. Sepsis is a life-threatening condition in which the body's immune response to infection becomes dysregulated leading to tissue damage and organ failure. Approximately one million people per year are diagnosed with sepsis in the United States (Singer et al., 2016), with a mortality rate of 28%–50% (Wood and Angus, 2004).

Although operational care process improvements in the past 20 years have led to reduction in mortality rate (Angus et al., 2015), therapeutic options for sepsis are limited to variations of antimicrobial and physiological support dating back nearly a quarter century. There remains no FDA-approved biologically targeted therapeutic for the treatment of sepsis, despite >30,000 patients enrolled across various clinical trials (Marshall, 2000; Opal et al., 2014).

Attempts to discover biologically targeted therapies for sepsis have thus far focused on manipulating a single mediator/cytokine, generally administered with either a single dose or for a very short course (<72 hours) (Marshall, 2000; Opal et al., 2014). Plausible explanations for their failures include inappropriate timing, duration, and/or dosing of the therapeutic agents as well as not accounting for the heterogeneity of the patient population. Thus, we hypothesize that controlling sepsis with cytokine mediation may require an adaptive personalized strategy involving multiple cytokines in coordination rather than a static generic therapy targeting a single cytokine.

This hypothesis can be tested in several ways, each of which involves employing optimal control methods to identify effective treatment strategies. Ideally, optimal control methods would be applied retrospectively, that is, using existing data. Indeed, data-driven approaches for optimal control of sepsis have been performed (Raghu et al., 2017); however, such retrospective studies can only optimize within the same limited space of control strategies that have already been attempted. Given that approaches to date have focused on single cytokine mediation, the data that would be required to test our hypothesis do not exist, and thus a purely data-driven approach is not possible. Alternatively, we could test the hypothesis prospectively, that is, through animal studies and/or clinical trials. However, searching the enormous space of dynamic multicytokine mediation would be prohibitively expensive. Optimal control methods would also require “exploring” and/or “perturbing” the system (i.e., patient) by deliberately applying suboptimal treatments, which raises ethical concerns.

Given the infeasibility of both data-driven and experiment-driven approaches for discovering adaptive multicytokine mediation, we turn to using a simulation as a surrogate of the real system. The use of an appropriate simulation that explicitly models relevant mechanisms has several major advantages: (1) one can explore therapeutic strategies beyond clinical practice and available data (in contrast to retrospective analyses) and (2) the number of candidate therapeutic strategies explored using optimal control is limited only by computational cost, which is generally orders of magnitude less than the costs of animal experiments and/or clinical trials.

For this investigation, we use a previously developed agent-based model (ABM) of systemic inflammation: the innate immune response agent-based model (IIRABM) (An, 2004) as a surrogate system for clinical sepsis. Previous experiments using the IIRABM provide an explanation as to why single/limited cytokine perturbations at a single or few time points are unlikely to significantly improve the mortality rate of sepsis (An, 2004). This result is consistent with the clinical failures of previous static nonpersonalized attempts at treating sepsis. Recently, genetic algorithms have been used to explore time-varying (but nonadaptive) multicytokine control strategies for the IIRABM (Cockrell and An, 2018). The results showed some generalizability, but the authors recognized that more advanced strategies are needed to achieve lower simulated mortality rates across a broader range of simulated patients. In this study, we apply deep reinforcement learning (DRL)—a class of optimal control methods—to the IIRABM to discover an adaptive personalized treatment policy that specifies effective multicytokine therapy to simulated sepsis patients based on systemic measurements.

To our knowledge, this work represents the first investigation into treating sepsis with adaptive personalized multicytokine mediation. We hope that by demonstrating this strategy through simulation, we will help inform and direct research toward “minimally sufficient” criteria for developing measurement technology, identifying biological targets for future drug development, and ultimately designing animal experiments and/or clinical trials. Finally, this work presents the first application of DRL to control a simulation of a biological system. We believe the use of simulation together with reinforcement learning (RL) for discovering adaptive and personalized therapeutics can have broad applicability in the biomedical sciences, with potential for large impacts.

2. Background

2.1. Agent-based models and their use as a sepsis simulation

ABMs are a generic class of computational models well suited to represent the complex, stochastic, and nonlinear dynamics of biological systems such as the immune response (An et al., 2009). ABMs are a powerful alternative to differential equation-based models. Although differential equation-based models excel in providing precise predictions for systems in which mechanisms are well understood and uncertainty is low, ABMs facilitate exploring the behavior space for complex stochastic systems in which mechanisms are poorly understood and uncertainty is high (Hunt et al., 2013). ABMs can also be highly modularized (Petersen et al., 2014), affording the ability to easily explore the space of new mechanisms and control strategies. ABMs have proved to be useful tools for biological applications, including immune system modeling (Baldazzi et al., 2006; Bailey et al., 2007), host–pathogen modeling (Bauer et al., 2009), and cancerous tumor modeling (Zhang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015).

Specifically, we use the existing IIRABM as a surrogate system for the investigation of potential control strategies for a hospitalized patient with sepsis, a role previously proposed for ABMs (An et al., 2017). The IIRABM simulates the human inflammatory signaling network response to injury. The model has been calibrated such that it reproduces clinical trajectories of sepsis (An, 2004; Cockrell and An, 2017). The IIRABM operates by simulating multiple cell types and their interactions, including endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and helper T cells (Th0, Th1, and Th2 cells).

The IIRABM has been used to simulate in silico clinical trials of mediator-directed therapies through the inhibition or augmentation of single cytokine synthesis pathways or limited hypothetical combinations of interventions (An, 2004). These studies reproduced the failures of past clinical trials and demonstrated that several other simulated treatment strategies were non-efficacious. The authors could not provide a pathway toward discovering a sucessful intervention strategy.

The IIRABM is instantiated by selecting five physiological parameters that characterize the injury/infection and host: initial injury size, microbial invasiveness, microbial toxigenesis, environmental toxicity, and host resilience. In previous work (Cockrell and An, 2017), the authors performed a parameter sweep to determine the subset of all parameterizations that are considered clinically relevant. These are parameterizations that can lead to multiple outcomes: complete healing, death by infection, or death from immune dysregulation/sepsis.

2.2. Reinforcement learning

RL is a class of methods within machine learning for finding solutions to high-dimensional control problems that may not be analytically tractable. RL is a suitable candidate for controlling ABMs, which do not have analytic expressions for their global state dynamics and are not straightforward to approach using classical control methods. A traditional simulation of an ABM proceeds “uninterrupted”: given an initial state and starting parameters, agents behave semiautonomously without external influence. In the context of RL, external actions are applied throughout the course of the simulation in an attempt to guide the system toward a desired final state. The goal of RL is to learn the best action to execute for each possible state during the simulation; it learns an adaptive policy for maximizing a reward function (e.g., a patient's health).

An RL problem is formulated as a Markov decision process, in which an environment interacts with an RL agent (see Supplementary Material). Since the sepsis environment exhibits a high-dimensional continuous state space, we exploit DRL, a subclass of RL that uses function approximators to represent the policy and/or value functions. Specifically, our RL agent is trained using the deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm (Lillicrap et al., 2015), a DRL algorithm suitable for continuous action spaces.

3. Methods

3.1. Defining the sepsis environment

We formalize the control problem by casting the IIRABM as an RL environment, that is, by defining initial and termination conditions, an observation space, action space, and reward function derived from the IIRABM.

3.1.1. Initial and termination conditions

An episode begins 12 hours after the onset of the initial simulated injury, that is, once the system has accumulated tissue damage and is trying to recover. Since both the initial state and the dynamics of the simulation are stochastic, this burn-in period produces a random draw from the environment's starting state distribution. An episode ends when the simulated patient completely heals or dies, or when the RL algorithm reaches 1000 steps.*

3.1.2. Observation space

The IIRABM state exists over a discrete 101  101 grid. There are 21 real-valued state variables of interest at each grid point: concentrations for 12 cytokines, concentrations for 2 cytokine receptors, counts for 5 cell types, a measure of tissue damage, and a measure of infection. However, a spatially resolved observation space would be clinically unrealistic, as it would involve measuring the precise locations of cells and local cytokine gradients in the body, which is infeasible given current technology. We chose a more clinically relevant observation space by spatially aggregating values for each dimension, consistent with systemic cell and cytokine concentrations, for example, as measured from a blood sample. This reduces the putative observation space from

101 grid. There are 21 real-valued state variables of interest at each grid point: concentrations for 12 cytokines, concentrations for 2 cytokine receptors, counts for 5 cell types, a measure of tissue damage, and a measure of infection. However, a spatially resolved observation space would be clinically unrealistic, as it would involve measuring the precise locations of cells and local cytokine gradients in the body, which is infeasible given current technology. We chose a more clinically relevant observation space by spatially aggregating values for each dimension, consistent with systemic cell and cytokine concentrations, for example, as measured from a blood sample. This reduces the putative observation space from  to

to  .

.

3.1.3. Action space

An action taken by the RL agent corresponds to a continuous value between −1 (maximal inhibition) and +1 (maximal augmentation) for each of the 12 cytokines (see Supplementary Material for details). Thus, the action space is  . Clinically, the choice of continuous actions reflects the ability of multiple therapeutics to be administered independently and with precise control through intravenous infusions. An action is applied every four frames of the ABM (which maps to 28 minutes) and the values are sustained in the ABM for all four frames. Note that cytokine mediation actions are applied on top of a fixed antibiotic therapy regimen in which antibiotics are applied every 24 hours. Since the antibiotic regimen is fixed, it is not considered as part of the control problem and is thus not part of the RL agent's action space.

. Clinically, the choice of continuous actions reflects the ability of multiple therapeutics to be administered independently and with precise control through intravenous infusions. An action is applied every four frames of the ABM (which maps to 28 minutes) and the values are sustained in the ABM for all four frames. Note that cytokine mediation actions are applied on top of a fixed antibiotic therapy regimen in which antibiotics are applied every 24 hours. Since the antibiotic regimen is fixed, it is not considered as part of the control problem and is thus not part of the RL agent's action space.

3.1.4. Reward function

A fully healed patient receives a positive terminal reward (chosen as +250). A patient who dies receives a negative terminal reward (chosen as −250). If the episode terminates early due to the 1000-step limit, there is no terminal reward. To facilitate learning, we provide an intermediate reward shaping term proportional to  , where

, where  . This term penalizes (or rewards) the RL agent for increasing (or decreasing) tissue damage, which helps the RL agent drive the state toward health. Finally, we added an L1 penalty to the reward function for actions taken. This promotes conservative actions (those that use less mediator), which is clinically relevant as real drugs incur additional side effects not explicitly captured in the simulation.

. This term penalizes (or rewards) the RL agent for increasing (or decreasing) tissue damage, which helps the RL agent drive the state toward health. Finally, we added an L1 penalty to the reward function for actions taken. This promotes conservative actions (those that use less mediator), which is clinically relevant as real drugs incur additional side effects not explicitly captured in the simulation.

Thus, the final reward function is

|

where  and

and  .

.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Training

We trained the RL agent on a single patient parameterization with 46% baseline (antibiotic only) mortality rate. Each episode used a different random seed. We ceased training at 2500 episodes (about 7 million frames), by which time the reward signal plateaued and many episodes resulted in healing during training.

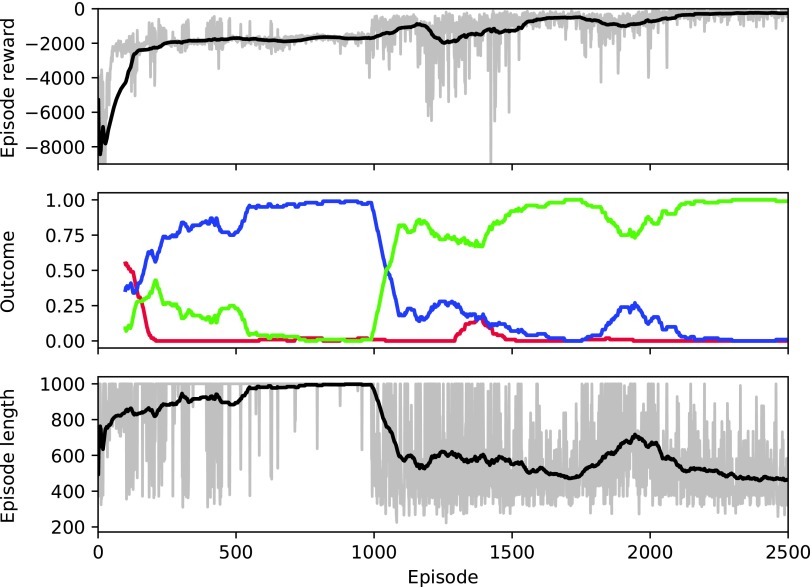

Figure 1 illustrates the reward per episode, outcome distribution, and episode length as a function of training episode. Taken together, these results suggest that the RL agent progresses through several qualitatively different stages of learning. Early on, some patients heal during training, as the policy begins centered around zero-valued actions (recall that the patient heals 46% of the time with standalone antibiotic therapy). The reward per episode then reaches an early peak around episode 125, despite a poor healing rate and long episodes. As the RL agent continues to learn, episode lengths increase up to the 1000-step maximum as both the healing and death rates drop to nearly zero. Around episode 1000, the RL agent begins healing patients quickly and episode length correspondingly declines to roughly 500 steps. For the remainder of the training episodes, the policy maintains a high healing rate. Thus, it appears that the RL agent first learned to stabilize the patient (leading to long episodes) despite not healing patients. It then learned to heal these patients and continued to improve by healing them faster.

FIG. 1.

Training performance. Top: reward per episode. Middle: moving average for 100 episodes of the rates of patient outcome (death: red, timeout: blue, health: green). Bottom: episode length (in steps). For the top and bottom plots, gray represents the actual value of each episode; black represents a moving average for 100 episodes.

4.2. Policy evaluation and generalizability

The clinically relevant measure of performance is patient outcome (life or death). Since the simulation is stochastic, any given initialization (with or without cytokine mediation) results in a distribution of outcomes. Thus, we evaluate a policy by its resulting mortality rate. Specifically, a policy proceeded until a health/death outcome was reached or 1000 time steps elapsed. At this point, cytokine mediation stopped and the patient proceeded for at least 12 hours before determining the final outcome. The learned policy resulted in 0% patient mortality rate during test time for the patient parameterization on which DDPG was trained.

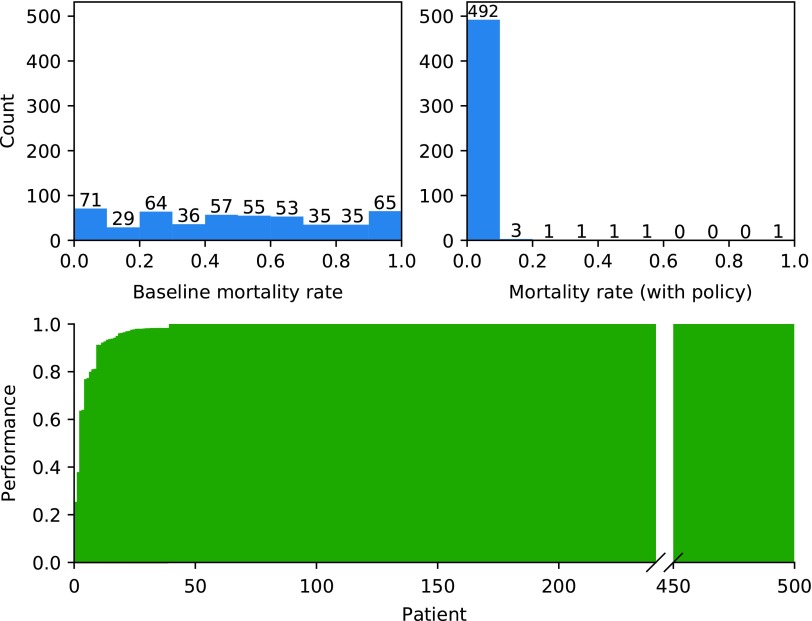

We analyzed the generalizability of the learned policy by testing it over a set of 500 different patient parameterizations with baseline mortality rates in the range 1%–99%. The patient parameterizations included in this study span the entire space of clinically plausible parameterizations for the IIRABM as determined in Cockrell and An (2017). For each patient parameterization, mortality rate was calculated for 50 episodes with different random seeds (Fig. 2; Top). The overall mortality rate (across all 500 patient parameterizations) improved from 46.0% with standalone antibiotic therapy to 0.8% under the policy. Moreover, no patient parameterization exhibited an increase in mortality rate compared to baseline. For each test patient parameterization, we also assessed a measure of performance of the policy relative to baseline (Fig. 2; Bottom). These results suggest that despite being trained on a single patient parameterization, the policy generalizes well, as it is robust to changes in patient parameterizations.

FIG. 2.

Top left: Histogram of baseline (standalone antibiotic therapy) mortality rates for 500 test patient parameterizations (N = 50 instances per test patient parameterization). Top right: Histogram of mortality rates using the learned policy (combination antibiotic cytokine mediation therapy) for 500 test patient parameterizations. Bottom: Performance of the learned policy on each of the 500 test patient parameterizations (defined as the difference in mortality rate with and without the policy, normalized by the larger of the two), sorted by increasing performance. Thus, positive values can be interpreted as the fraction of patients who were healed by the policy that otherwise would have died, whereas negative values indicate the fraction of patients who died from the policy that otherwise would have healed. Since the policy did not cause an increase in mortality rates for any patient parameterization, there are no negative values.

4.3. Policy characterization

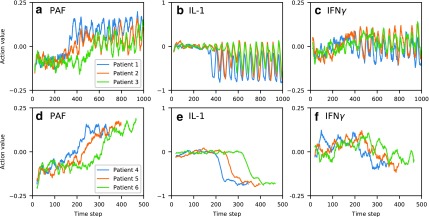

To investigate whether the learned policy indeed (1) is adaptive to patients' state progression over time, (2) prescribes personalized (i.e., patient-specific) actions, and (3) involves mediating multiple cytokines simultaneously in coordination, we characterized the policy by observing the time series of selected actions over various characteristic episodes on different patient parameterizations.

In the first test, we selected patient parameterizations with recurrent injury values in the set  (low, middle, and high values in the parameter range), and identical values for all other parameters. These parameterizations correspond to baseline mortality rates

(low, middle, and high values in the parameter range), and identical values for all other parameters. These parameterizations correspond to baseline mortality rates  , respectively. Each parameterization healed under the policy. Figure 3a–c illustrates the moving average of time series of actions prescribed for cytokines platelet-activating factor (PAF), interleukin (IL)-1, and interferon (IFN)

, respectively. Each parameterization healed under the policy. Figure 3a–c illustrates the moving average of time series of actions prescribed for cytokines platelet-activating factor (PAF), interleukin (IL)-1, and interferon (IFN) , respectively. The policy's actions for this patient demonstrate that the policy is adaptive, even switching from inhibition to augmentation during the course of treatment in the case of PAF. Differences between patient trajectories show the policy's specificity to different patient parameterizations. The periodicity of action values that arise after certain time points further reflects the policy's adaptive response to recurrent injuries: after patients have reached the health threshold, the policy specifies a repeating cycle of augmentation of IL-1 when the recurrent injury reappears, and inhibition once the recurrent injury is cleared. In each of the cytokines shown, we see that patient 3 (green) takes the most time to enter the periodic region, since this patient has the highest recurrent injury number.

, respectively. The policy's actions for this patient demonstrate that the policy is adaptive, even switching from inhibition to augmentation during the course of treatment in the case of PAF. Differences between patient trajectories show the policy's specificity to different patient parameterizations. The periodicity of action values that arise after certain time points further reflects the policy's adaptive response to recurrent injuries: after patients have reached the health threshold, the policy specifies a repeating cycle of augmentation of IL-1 when the recurrent injury reappears, and inhibition once the recurrent injury is cleared. In each of the cytokines shown, we see that patient 3 (green) takes the most time to enter the periodic region, since this patient has the highest recurrent injury number.

FIG. 3.

Moving average of action values (window length 20) for PAF, IL-1, and IFN , selected by the learned policy during test treatment of three patient parameterizations. Top row (a–c): varying recurrent injury parameter, all other parameters held constant. Bottom row (d–f): varying initial injury size, all other parameters held constant, with recurrent injury set to zero. All patients healed from the policy's intervention. IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; PAF, platelet-activating factor.

, selected by the learned policy during test treatment of three patient parameterizations. Top row (a–c): varying recurrent injury parameter, all other parameters held constant. Bottom row (d–f): varying initial injury size, all other parameters held constant, with recurrent injury set to zero. All patients healed from the policy's intervention. IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; PAF, platelet-activating factor.

We repeated this experiment for patient parameterizations with initial injury size in the set  , with all other parameters held constant and recurrent injury set to zero (to remove the aforementioned periodicity). These parameterizations correspond to baseline mortality rates {4%, 30%, 100%}, respectively. Figure 3d–f demonstrates the policy's adaptive transition between inhibition and augmentation, as well as dependence on a patient's initial injury size.

, with all other parameters held constant and recurrent injury set to zero (to remove the aforementioned periodicity). These parameterizations correspond to baseline mortality rates {4%, 30%, 100%}, respectively. Figure 3d–f demonstrates the policy's adaptive transition between inhibition and augmentation, as well as dependence on a patient's initial injury size.

Although a thorough biomedical interpretation of the learned policy is beyond the scope of this article, we note that the policy has some intuitive characteristics. For example, the control pattern of IL-1 (a proinflammatory cytokine) seen in Figure 3e is consistent with nonsuppression during the very early phases of the response where IL-1 is needed to clear the infection, followed by later suppression of IL-1 to aid in containment of runaway inflammation and collateral damage. Moreover, the suppression occurs later for patients with larger initial injury (e.g., patient 6), likely due to the fact that the immune system requires a longer period of inflammation for larger initial injury sizes to contain and control the greater level of infection/injury present. IFN follows a similar pattern (Fig. 3f), although less clearly defined perhaps due to its more complicated secondary effects like modulating Th cell population distributions.

follows a similar pattern (Fig. 3f), although less clearly defined perhaps due to its more complicated secondary effects like modulating Th cell population distributions.

5. Conclusion

We propose a novel approach for precision medicine that involves formulating a dynamic feedback control problem, simulating the disease process mechanistically, and using optimal control methods to identify adaptive personalized therapeutic strategies. We demonstrated this approach using an agent-based simulation of sepsis and investigated whether adaptive personalized multicytokine mediation is an effective approach for lowering simulated patient mortality rate. Using DRL, we identified a policy that dramatically lowers mortality rate across a wide range of simulated patients. These proof-of-concept results using simulation motivate further investigation into such adaptive approaches on real systems.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to exploit DRL to control a biological simulation, and is the first to consider adaptive personalized multicytokine mediation therapy for sepsis. This work has demonstrated that mechanism-based simulations in the biomedical sciences can be a powerful alternative to relying exclusively on real-world data sets. Indeed, the mechanism-based simulation enabled us to explore therapeutic strategies that have never been attempted in clinical or experimental settings. This work has also demonstrated that DRL is a powerful methodology to control simulations of real-world systems; we hope that such methods continue to be applied to simulations in biology and beyond.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Desautels, Jason Lenderman, and Aaron Wilson for their insightful feedback and comments throughout the course of this study. This work was supported, in part, by NIH/NIGMS Grant 1S10OD018495-01 (G.A. and C.C.).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no conflicting financial interests exist.

To avoid ambiguity, hereafter we refer to a frame as a single step of the ABM; we use step to refer to a single step taken by the RL agent.

References

- An G. 2004. In silico experiments of existing and hypothetical cytokine-directed clinical trials using agent-based modeling. Crit. Care Med. 32, 2050–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G., Fitzpatrick B.G., Christley S., et al. 2017. Optimization and control of agent-based models in biology: A perspective. Bull. Math. Biol. 79, 63–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G., Mi Q., Dutta-Moscato J., et al. 2009. Agent-based models in translational systems biology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 1, 159–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus D.C., Barnato A.E., Bell D., et al. 2015. A systematic review and meta-analysis of early goal-directed therapy for septic shock: The arise, process and promise investigators. Intensive Care Med. 41, 1549–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A.M., Thorne B.C., and Peirce S.M. 2007. Multi-cell agent-based simulation of the microvasculature to study the dynamics of circulating inflammatory cell trafficking. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 35, 916–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldazzi V., Castiglione F., and Bernaschi M. 2006. An enhanced agent based model of the immune system response. Cell. Immunol. 244, 77–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A.L., Beauchemin C.A.A., and Perelson A.S. 2009. Agent-based modeling of host–pathogen systems: The successes and challenges. Inf. Sci. 179, 1379–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockrell C., and An G. 2017. Sepsis reconsidered: Identifying novel metrics for behavioral landscape characterization with a high-performance computing implementation of an agent-based model. J. Theor. Biol. 430, 157–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockrell C., and An G. 2018. Examining the controllability of sepsis using genetic algorithms on an agent-based model of systemic inflammation. PLoS Computat. Biol. 14, e1005876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C.A., Kennedy R.C., Kim S.H.J., et al. 2013. Agent-based modeling: A systematic assessment of use cases and requirements for enhancing pharmaceutical research and development productivity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 5, 461–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap T.P., Hunt J.J., Pritzel A., et al. 2015. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv arXiv:150902971 [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.C. 2000. Clinical trials of mediator-directed therapy in sepsis: What have we learned? Intensive Care Med. 26, S075–S083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. 2011. Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease. National Academies Press, Washington (DC) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal S.M., Dellinger R.P., Vincent J.-L., et al. 2014. The next generation of sepsis trials: What next after the demise of recombinant human activated protein C? Crit. Care Med. 42, 1714–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen B.K., Ropella G.E.P., and Hunt C.A. 2014. Toward modular biological models: Defining analog modules based on referent physiological mechanisms. BMC Syst. Biol. 8, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu A., Komorowski M., Celi L.A., et al. 2017. Continuous state-space models for optimal sepsis treatment—A deep reinforcement learning approach. arXiv arXiv:170508422 [Google Scholar]

- Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., et al. 2016. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 3150, 801–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Butner J.D., Kerketta R., et al. 2015. Simulating cancer growth with multiscale agent-based modeling. Sem. Canc. Biol. 30, 70–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K.A., and Angus D.C. 2004. Pharmacoeconomic implications of new therapies in sepsis. Pharmacoeconomics 22, 895–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Athale C.A., and Deisboeck T.S. 2007. Development of a three-dimensional multiscale agent-based tumor model: Simulating gene-protein interaction profiles, cell phenotypes and multicellular patterns in brain cancer. J. Theor. Biol. 244, 96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.