Abstract

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) mechanical ablation is an emerging technique for noninvasive transcranial surgery. Lesions are created by driving inertial cavitation in tissue, which requires significantly less peak pressure and time-averaged power compared with traditional thermal ablation. The utility of mechanical ablation could be extended to the brain provided the pressure threshold for inertial cavitation can be reduced. In this study, the utility of perfluorobutane-based phase-shift nanoemulsions (PSNE) for lowering the inertial cavitation threshold and enabling focal mechanical ablation in the brain was investigated. We successfully achieved vaporization of PFB PSNE at 1.8 MPa with 740 kHz focused transducer with pulsed sonication protocol (duty cycle = 1.5%, 10 mins sonication) within intact CD-1 mice brains. Evidence is provided showing that a single bolus injection of PSNE could be used to initiate and sustain inertial cavitation in cerebrovasculature for at least 10 minutes. Histological analysis of brain slices after HIFU exposure revealed ischemic and hemorrhagic lesions with dimensions that were comparable to the focal zone of the transducer. These results suggest that perfluorobutane-based PSNE may be used to significantly reduce the inertial cavitation threshold in the cerebrovasculature, and when combined with transcranial focused ultrasound, enable focal intracranial mechanical ablation.

Keywords: focused ultrasound, brain, nonthermal ablation, phase-shift nanoemulsions, microbubble, ultrasound therapy

Introduction

High intensity focused ultrasound ablation has drawn increasing attention in recent years as an alternative to surgical resection of brain tumor. Surgical resection is part of the standard of care for brain tumors (Weller et al. 2014). Patients with brain tumors are usually recommended for surgical resection if possible and there is evidence that more aggressive resections significantly improved the overall survival rate (Chaichana et al. 2014b; Chaichana et al. 2014a). However, for many patients, surgical resection is not an option due to the proximity of the tumor to critical vascular and neural systems (De la Garza-Ramos et al. 2016). Moreover, surgical removal of brain tumor is an invasive procedure that is challenging and risky to patients of advanced age and poor health conditions (Karsy et al. 2018). Therefore, an alternative method to surgical resection that can noninvasively ablate brain tumors that are deemed inoperable is highly desired. To our knowledge, high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is the only completely noninvasive method available on the market that can access and locally ablate inoperable tumors.

HIFU technology utilizes a focused ultrasound transducer to transmit ultrasonic waves noninvasively and ablate targeted tissue either thermally or mechanically (Coluccia et al. 2014). Currently, only HIFU thermal ablation has been approved by FDA for various clinical indications including uterine fibroid ablation, palliation for bone metastases, prostate tissue ablation, and essential tremors (Elias et al. 2016; Gianfelice et al. 2008; Koch et al. 2007; Stewart et al. 2006). HIFU thermal ablation utilizes the heat generated by the absorption of focused ultrasound to coagulate tissues. To enable brain applications, transcranial MRI-guided HIFU systems have been developed and shown to be capable of thermally ablating brain tumors (Coluccia et al. 2014; McDannold et al. 2010).

There are several critical challenges for the application of HIFU thermal ablation in the brain. One of the critical issues is the utilization of high time-averaged power (i.e. over 1000 W) which could result in skull heating when treating peripheral brain regions. Long periods between sonications are also required to allow for the skull to cool, prolonging the treatment and making it challenging to ablate more than tiny volumes (Coluccia et al. 2014). Furthermore, the incidence angle between the incident ultrasound and the skull is large when targeting peripheral regions (White et al. 2006). This significantly increases the reflection of ultrasound, so that the energy deposition efficiency is further reduced. The limitation was evident in a MRI temperature measurement of a tumor patient in which surface heating was observed (McDannold et al. 2010). Standing waves induced within the skull by the long ultrasound bursts typically utilized for thermal ablation is another issue to be considered. The results of experiments and numerical simulations have shown that long tone bursts can create standing wave patterns in the brain, leading to unwanted thermal coagulation outside the focus (Azuma et al. 2005; Baron et al. 2009; Junho Song et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2008). To overcome these problems, transcranial MRI-guided focused ultrasound (FUS) systems using hemispherical phased arrays have been developed (Elias et al. 2016). These systems mitigate heating in the skull by delivering energy to the focus through a larger aperture and using active cooling (Elias et al. 2016; Huss et al. 2015; McDannold et al. 2010). Despite these technical advancements, targeting surface of the brain remains a challenge. Therefore, there is a need for new ablation methods that use significantly lower time-averaged power for treating superficial regions.

One way to dramatically decrease the time-averaged acoustic power is to use mechanical ablation instead of thermal ablation. Mechanical ablation — including histotripsy (Khokhlova et al. 2015; Roberts et al. 2006) and microbubbles (MBs) facilitated mechanical ablation (Arvanitis et al. 2016; Burke et al. 2011; McDannold et al. 2006) has been explored over last decade as alternative to thermal ablation. Unlike thermal ablation, mechanical ablation typically uses short pulses, which limits the overall heat generation during the treatment. Histotripsy is a treatment uses short pulses at pressures exceeding the intrinsic cavitation threshold in tissue (Vlaisavljevich et al. 2015), creating bubble clouds at the focus that homogenize tissue in a highly localized manner (Xu et al. 2005). However, the pressure used in histotripsy — usually above 20 MPa (Khokhlova et al. 2014; Maxwell et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2015) — is even higher than in thermal ablation, which could result in safety concerns. In contrast, MB-facilitated ablation takes advantage of preformed microbubbles (i.e. ultrasound contrast agents) that are injected into the bloodstream. The microbubbles are driven to oscillate with ultrasound and generate stresses that can adversely affect blood vessels, resulting in a significant reduction in tumor perfusion leading to cancer cell death (Al-Mahrouki et al. 2014a; Czarnota et al. 2012) The pressure magnitude required for this bioeffect is three orders of magnitude smaller than the thermal ablation (i.e. 300 W vs 0.1 W). Additionally, the duty cycle which determines on/off ratio of ultrasound transmission is two orders lower (i.e. 1% vs 100% for MB-facilitated vs thermal ablation) (Huang et al. 2013; McDannold et al. 2013; McDannold et al. 2016; McDannold et al. 2006). MBs, when injected intravenously, circulate in the blood stream and cavitate in response to incident ultrasound waves, generating stresses that mechanically ablate tissues (McDannold et al. 2006). However, researchers have been concerned about the damage along the ultrasound pathway due to nonlinear bubble oscillations in the prefocal zones (Arvanitis et al. 2016; Moyer et al. 2015; Phillips et al. 2013). Furthermore, commercial MBs (i.e. ultrasound contrast agents) usually circulate for only a few minutes (Wu et al. 2017), so a volumetric ablation of tumor would require continuous infusion of microbubbles, which is dose limited.

Due to those limitations, using phase shift nanoemulsions (PSNE) to facilitate mechanical ablation has been proposed. PSNE have a lipid monolayer shell with a liquid perfluorocarbon core (Kopechek et al. 2014; Sheeran et al. 2012). PSNE can be vaporized into bubbles when they are exposed to ultrasound that has peak negative pressure higher than the vaporization threshold (Fabiilli et al. 2010; Schad and Hynynen 2010a; Zhang and Porter 2010). Therefore, it is possible to only activate PSNE and create lesions at the focus while sparing tissue in the prefocal zones. Submicron perfluorocarbon droplets have been synthesized with a mean diameter of approximately 200 nm and PEGylated lipid on the surface, which prolonged the circulation in the vasculature (Suk et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2013). For nanoparticles at the range of 50–600 nm, there is a higher chance to accumulate in tumors due to the leaky vasculatures and immature lymphatic drainage system, a phenomenon called enhanced permeability (EPR) effect (Charrois and Allen; Ishida et al. 1999; Maeda et al. 2000; Nomura et al. 1998; Yuan et al.). By virtue of the EPR effect, PSNE have a higher possibility than microbubbles to accumulate into tumors, making it a potentially better candidate for mechanical tumor ablation.

Previously, our group injected perfluoropentane (PFP) PSNE introvenously (i.v.) and observed an accumulation of PFP PSNE within the implanted tumor in a rabbit (Kopechek et al. 2014). A lesion was created successfully in that study. However, the vaporization threshold of PFP PSNE was 3–5 MPa, which potentially would cause severe adverse effects in the brain, particularly at the lower frequencies used for transcranial sonication. We were therefore encouraged to look for another formulation to synthesize PSNE with a more volatile perfluorocarbon such as perfulorobutane (PFB). PFB-based nanoemulsions produced using a microbubble condensation method (Sheeran et al. 2011; Sheeran et al. 2012) reportedly have been vaporized at pressures less than 2 MPa (Sheeran et al. 2013), which is a more ideal pressure for ultrasound applications in the brain.

In this study, we investigated ultrasound-induced vaporization of PFB-based PSNE at 740 kHz, which is a clinically relevant frequency (i.e. 650 kHz for Exablate Neuro system, Insightsec Ltd, Tirat Carmel, Israel) for transcranial applications (Clement et al. 2000). There have only been limited investigations on the vaporization of PSNE using transducer operating below one megahertz (Giesecke and Hynynen 2003; Schad and Hynynen 2010b), the acoustic signatures of PSNE at sub-MHz frequency range is thus vital for monitoring and control of PSNE vaporization in the brain. Our objectives here were to use PFB PSNE to lower the mechanical ablation threshold in the brain through an intact skull in a mouse model. Broadband acoustic emissions recorded with a passive cavitation detector were monitored during each sonication. The lesions were characterized through histological analysis.

Materials and Methods

Emulsions preparation

PSNE were prepared using a cooling and condensation protocol described in (Sheeran et al. 2012). In brief, the lipid solution was formed from 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) from Avanti Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA) in a 95:5 molar ratio. Lipids (45 mg in total) were dissolved in chloroform for a thorough mixture. The solvent was evaporated, and the dry lipid film was rehydrated with 15 ml phosphate-buffered saline at 60 oC to achieve a final concentration of 3 mg/ml lipid solution. The lipid solution was sonicated for 2 min at 20% power (100 Watt at 20 kHz) using a Vibra-Cell probe sonicator (VC 505, Sonics & Materials, Newtown, CT, USA) at room temperature right before use. A 0.75 ml volume of lipid solution was transferred to a 1.5 ml glass vial with a septum cap. The cap space was then ventilated with 4 ml perfluorobutane (PFB) gas. An addition 6 ml volume of PFB gas was injected into the vial. A high-speed shaker was then used to shake the vial for 30 s to generate microbubbles. The MB solution was transferred into a 7 ml glass vial with 5 ml PBS. The PBS was degassed overnight, and the cap space then was replaced with PFB gas. The glass vial was then put into an acetone dry ice bath, which was kept at −5 oC to −10 oC. The vial was pressurized with PFB until the solution became clear, which indicated a transition from microbubbles to nanoemulsions, followed by 3 passes through 200 nm polycarbonate membrane filters (Whatman, Piscatway, NJ, USA) using a LIPEX extruder (Northern Lipids, Burnaby, BC, Canada). The resulting PSNE solution was kept in the 7 ml glass vial with the headspace filled with PFB gas at 20 psi. The PSNE solution was stored in the refrigerator until use. The synthesized PSNE were diluted and measured with qNano (Izon science, Cambridge, MA, USA). The mean PSNE diameter was 226 ± 7.3 nm and the mean concentration was 5.2 ± 1.4 × 109 particles/ml.

Animals

Experiments were performed in accordance with procedures approved by the Brigham and Women’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed in 12 male CD-1 mice each weighing 25–30 g. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. The hair on the head was removed beforehand, a catheter was placed in the tail vein, and PSNE (100 μl) were administered as a bolus injection for all animals (N = 12).

Focused ultrasound ablation

A focused circular transcranial ultrasound transducer was built in-house that has 10 cm aperture and 8 cm curvatures. The center frequency of the transducer is 740 kHz. The transducer was driven by sinusoidal waves produced by a function generator (Agilent 33250A, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and amplified by a power amplifier (ENI 2100L, Bell Electronics, Renton, Washington, USA). Electrical power output from the amplifier was measured using a power meter (E4419B, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a dual directional coupler (model C5948, Werlatone, Patterson, NY, USA). A laboratory assembled radiation force balance was used to measure the acoustic power transmitted from the transducer in degassed water. Additionally, the transmitted pressure field was mapped using a needle hydrophone (HNC-0200, Onda, CA, USA). As is shown in figure 1B, the transverse and longitudinal full width half maximum of the transducer focus are 2.5 and 11.7 mm respectively.

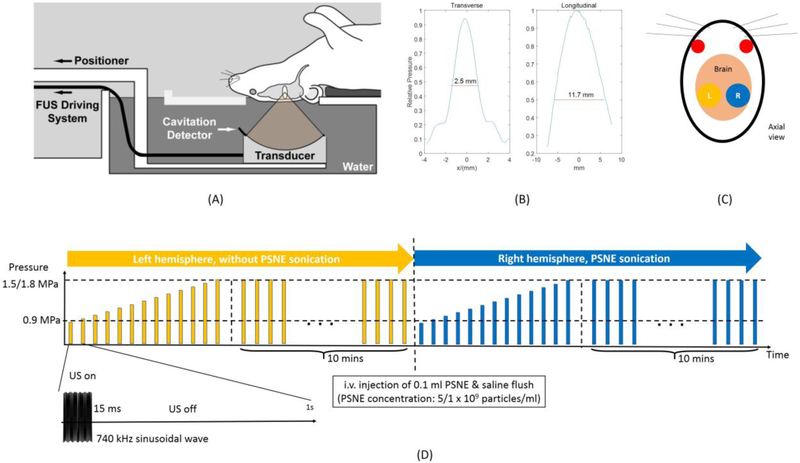

Figure 1:

(A) Experimental setup. A focused transducer and a cavitation detector were mounted on a manually adjustable 3D positioner located in a water tank. The mice were held by a customized holder in a supine position. (B) The longitudinal and transverse pressure profiles of the focused transducer. (C) Schematic of the targets location. (D) Timeline and schematic of sonication protocol. For each animal, the left hemisphere was sonicated first and then 0.1 ml PSNE in different concentrations will be administered before the right hemisphere was sonicated. For each sonication on both hemispheres, series of ramping pressure pulses will be applied followed by 10 mins constant pressure pulses. Each pulse consisted of 15 ms 740 kHz sinusoidal wave repeated at 1 Hz.

As is shown in figure 1A, the transducer was mounted on a manually adjustable three-axis translation stage and submerged into degassed deionized water within an acrylic tank. The animals were placed in a plastic stereotactic frame (constructed in house), which was attached so that the animals were supine with the top of their head in the water bath. The targets were selected from a mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin 2004) and were centered 2.5 mm lateral, 3 mm dorsal, and 3 mm anterior. As is shown in figure 1C, each animal has two sonications located at a region 1.5 mm above hippocampus on both hemispheres (left hemisphere: sonication without PSNE started from 0 min; right hemisphere: after sonication of left hemisphere and i.v. injection of PSNE followed by saline flush). Sonication protocol is described in figure 1D. Each sonication started with a series of 15 ms pulses repeated at 1 Hz and each pulse has pressure increased from 0.9 MPa to 1.5/1.8 MPa at 0.18 MPa pressure interval (4 mice with 1.8 MPa and 4 mice with 1.5 MPa). Immediately after that, constant pressure (the maximum pressure used in ramping pressure pulses) pulses with 15 ms burst length that repeated at 1 Hz were used to sonicate the brain for 10 mins (4 mice with 1.8 MPa and 4 mice with 1.5 MPa). The corresponding time-averaged acoustic power for 1.5 MPa and 1.8 MPa was approximately 0.17 and 0.24 W, respectively. To understand the effect of PSNE concentration on the ablation, another group of animals (4 mice) were sonicated with 1.8 MPa after injection of diluted PSNE (dilution factor = 5). The 5 times dilution factor was chosen based on a pilot study from our group (unpublished) that showed no apparent damage generated at this condition. All other acoustic parameters remained the same. The summary of acoustic parameters and PSNE concentrations for different groups is shown in table 1.

Table 1:

List of key parameters for different groups

| Group | Pressure (MPa) |

PSNE concentration (particles/ml) |

Number of subjects |

|---|---|---|---|

| High pressure high PSNE concentration |

1.8 | 5.2 ± 1.4 × 109 | 4 |

| Low pressure high PSNE concentration |

1.5 | 5.2 ± 1.4 × 109 | 4 |

| High pressure low PSNE concentration |

1.8 | 1.0 ± 0.3 × 109 | 4 |

Monitoring PSNE-nucleated inertial cavitation

Acoustic vaporization of PSNE and subsequent inertial cavitation activity were monitored using a passive cavitation detector (PCD). An unfocused 400-kHz transducer served as the PCD and was positioned orthogonal to and confocal with the FUS transducer. The PCD acquired acoustic energy radiated at frequencies below 740 kHz, which could only be generated by nonlinearly oscillating and collapsing MB. Two notch filters (Customized Notch filter, FD: 660kHz, Allen Avionic; in-house notch filter with 740 kHz center frequency) were used to filter out the fundamental frequency from the transducer and a digital pulse receiver (Pulser/Receiver 5072PR, GE panametrics, Waltham, MA, USA) was used as the amplifier for the PCD signal providing 40 dB gain and operating in low-pass mode (cut off frequency 10 MHz). Acoustic emissions were digitized by a high-speed AD converter (PXIe 1073, National Instruments) at a sampling rate of 5 MHz.

Analysis of PSNE-nucleated inertial cavitation (IC)

The PCD signals were processed and analyzed to determine a threshold for PSNE-nucleated IC and to characterize the IC activity. The IC threshold was determined by comparing the mean broadband acoustic emission power spectra (MBEPS) for PSNE and no PSNE groups. The MBEPS was calculated as in equation (1):

| (1) |

PS stands for power spectrum, which was the square of the signal spectrum calculated by fast Fourier transform in MATLAB. f0 represents the center frequency of the spectrum of interest, which was 370 kHz (subharmonic) in this study. fb denotes the frequency bandwidth of the spectrum of interests, which was 40 kHz in this study. PSnoise(f) was considered the power spectrum of the electronic noise of the system, which was estimated by averaging from 5 acquisitions without ultrasound transmission. The IC threshold was identified as the lowest pressure at which the MBEPSPSNE was statistically larger than MBEPSNOPSNE. Two-samples Student’s t-test with unequal variance was used for statistical analysis. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

We speculated that IC activity, and thus the power within PCD signals, would vary with the concentration of administered PSNE. To test the hypothesis, the enhancement in PS for a PSNE group relative to a control group (i.e. no PSNE) was calculated and compared for different administered concentrations of PSNE. The relative enhancement in PS within a given bandwidth was calculated as in equation (2):

| (2) |

Histological analysis

Animals were sacrificed within 24 h after treatment under deep anesthesia with isoflurane. The brains were fixed by cardiac perfusion using 0.9% NaCl (10 ml) followed by 10% buffered formalin phosphate (10 ml). The brains were then harvested and kept in 10% buffered formalin phosphate for at least 24 hours before histology. Mice brains were then cut into two 3 mm blocks. Blocks were cut into 2 μm thickness sections and every 50 sections were stained with H&E. The lesions were manually selected by one investigator (C. Peng) and analyzed with ImageJ to measure the lesion sizes. The areas of lesions from the group using non-diluted PSNE sonicated with 1.8 MPa (the only group that has lesion at targeted area) were averaged (N = 4) and compared to the circular area of the transverse full width half maximum (FWHM) of the transducer acoustic focus.

Results

PSNE vaporization and inertial cavitation

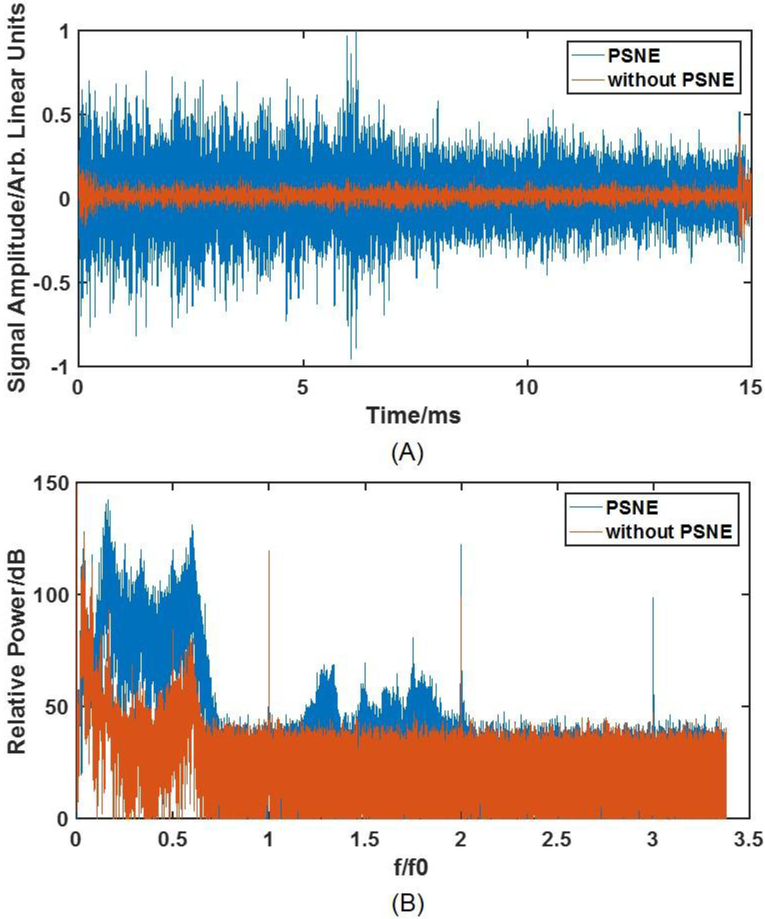

Acoustic emissions received by the PCD were processed and compared across a range of conditions. Typical temporal and spectral signals from the PCD with and without PSNE at 1.8 MPa are plotted in figure 2. There was a significant increase in the peak voltage and the relative power of the PCD signal associated with PSNE vaporization and inertial cavitation in the brain. Given that the bandwidth of the PCD was less than the frequency of the transmitted tone burst, the detected acoustic emissions should originate only from cavitating microbubbles created in the acoustic field. Therefore, the representative traces in figure 2 suggest that enough acoustic energy was transmitted through the skull to vaporize the PSNE and drive inertial cavitation activity.

Figure 2:

(A) time domain signal of acoustic emissions obtained during 1.8 MPa bursts applied with and without PSNE. The sonication started at 0 ms and ended at 15 ms. (B) the corresponding frequency domain power spectrum as a function of normalized frequency (f0 = 740 kHz) for these two bursts. A significant elevation of signal at both temporal and frequency domain could be observed indicating vaporization of PSNE.

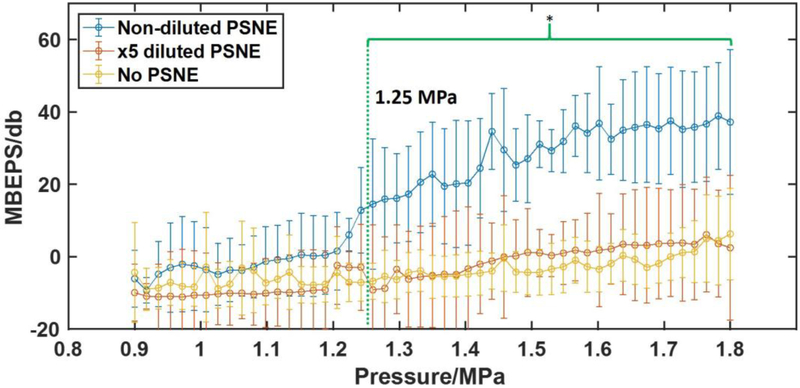

The detected IC activity was quantified as MBEPS and plotted as a function of transmitted pressure (figure 3). For the PSNE group (5.2 ± 1.4 × 108 injected particles), MBEPS did not change significantly until the pressure exceeded 1.2 MPa. The lowest non-derated pressure at which MBEPS for the PSNE group was significantly greater than MBEPS for control group was 1.25 MPa (p<0.05), which was identified as the IC threshold. Comparatively, there was no significant elevation of MBEPS generated from 5x diluted PSNE (1.0 ± 0.3 × 108 injected particles).

Figure 3:

Mean of Broadband Emission Power Spectra (MBEPS) from sonication with and without PSNE as a function of the pressure amplitude. The green bracket indicates the pressure range that MBEPS of non-diluted PSNE (5.2 ± 1.4 × 109 particles/ml) was significantly higher than for sonication without PSNE. After 1.25 MPa, sonications with non-diluted PSNE created significant higher MBEPS — a measurement of acoustic emission — than the sonication without PSNE. MBEPS of ×5 diluted PSNE (1.0 ± 0.3 × 109 particles/ml) has no significant difference with that obtained without PSNE control indicating a lack of PSNE-nucleated inertial cavitation. (Mean ± standard deviation shown, N=4 for the two PSNE groups. N=8 for controls; *P < 0.05).

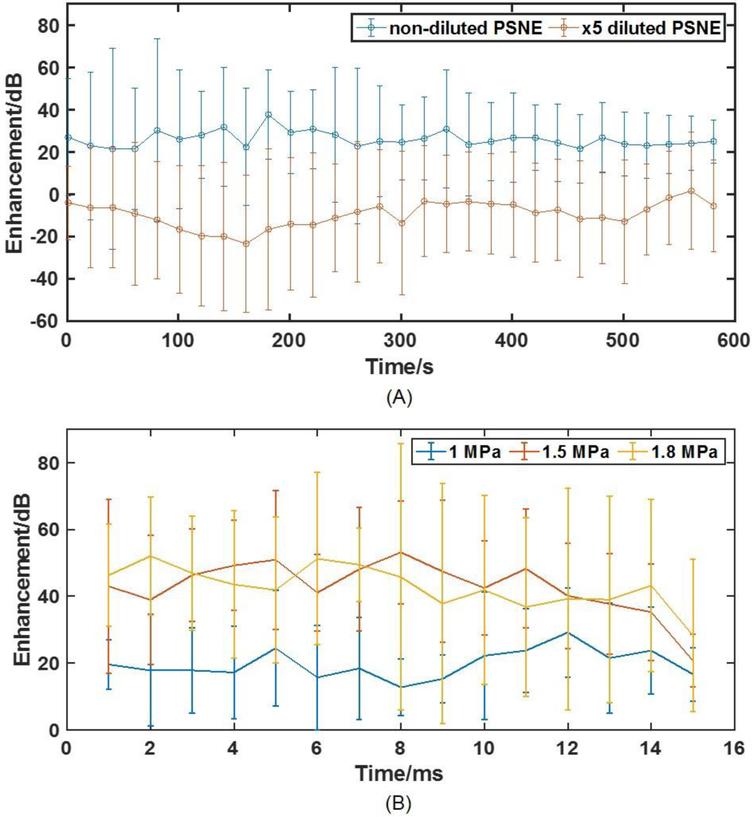

To further investigate PSNE vaporization and IC activity over a relatively longer period, 10-minute sonications were applied after the ramping pulse and the acoustic emission enhancement was calculated and plotted in figure 4A. Elevated acoustic emissions were detected throughout the 10-minute exposure, indicating a continuous existence and vaporization of PSNE in the blood stream. The average enhancement acoustic emission within each 15-ms tone burst at 1 MPa, 1.5 MPa and 1.8 MPa is presented in figure 4B. The results show that inertial cavitation occurred over the entire duration of the tone burst, most likely sustained by PSNE vaporization.

Figure 4:

(A) Acoustic emission enhancement of non-diluted and ×5 diluted PSNE over 10 mins. The enhancement stayed stable during 10 mins which indicated a constant activation of PSNE during the whole sonication. (B) Acoustic emission enhancement as a function of time within each 15 ms bursts during sonication at 1, 1.5, and 1.8 MPa. The acoustic emission enhancement is stable throughout the pulse length indicating the PSNE were vaporized as soon as the sonication started and there that were presumably enough PSNE to be vaporized during the pulse. (N = 4 per group).

Histological analysis of PSNE-enhanced lesions

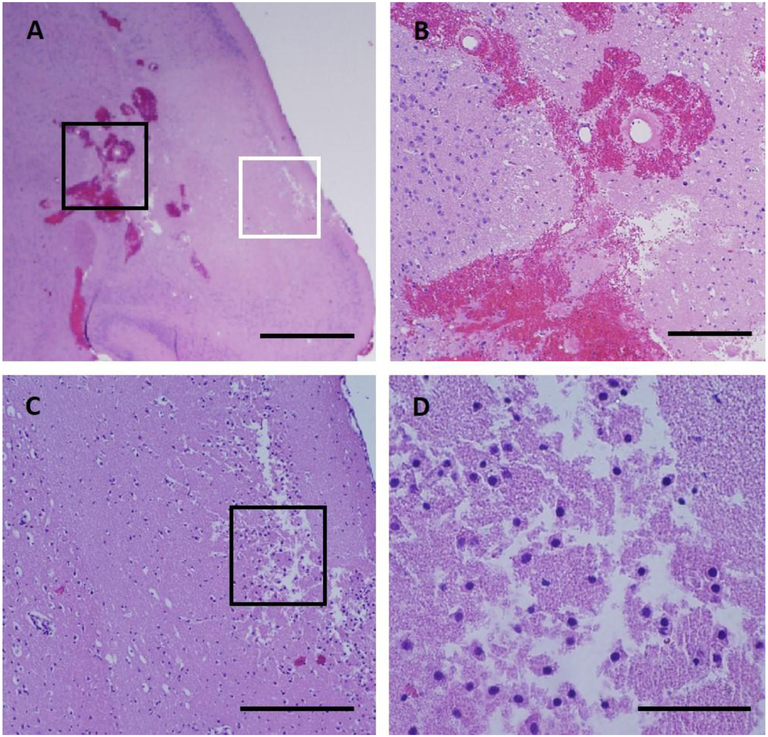

High pressure (1.8 MPa) and non-diluted PSNE:

Examinations of the lesions in tissue blocks showed hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in the targeted area (right of figure 5A and figure 5B) and there was no apparent damage in the contralateral side (left side in figure 5A and figure 5C). Histological examinations revealed that intense PSNE-nucleated IC activity at this pressure led to blood vessel rupture localized to the lesion (figure 6A and 6B). Erythrocyte extravasation was more obvious around large blood vessels, which could be due to the relatively lower inertial cavitation threshold in larger blood vessels (Hynynen 1990). Damage to the microvasculature could disrupt the local blood supply resulting in ischemic necrosis in the targeted area as shown in figure 6C. Tissue fragmentation could also be observed in figure 6D, which was possibly the result of mechanical fragmentation.

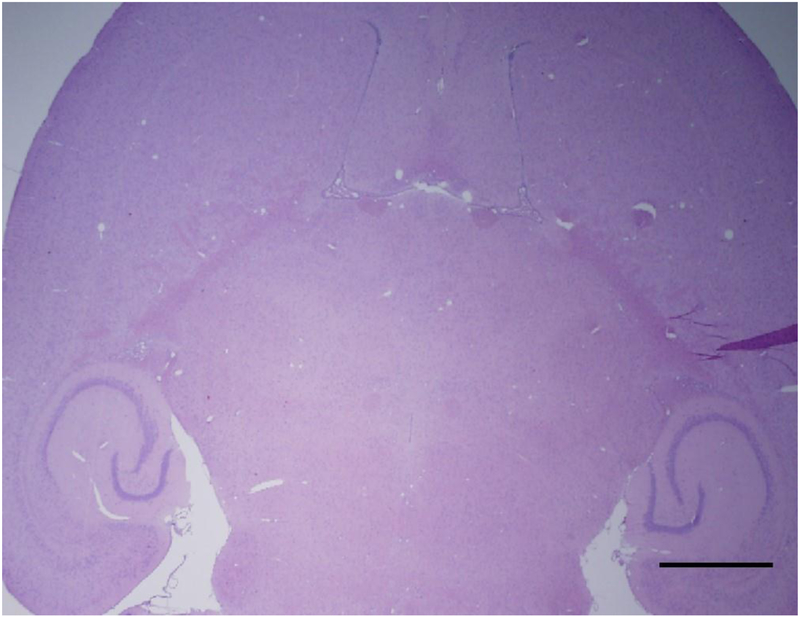

Figure 5:

Representative histological slices from the subjects that were injected with non-diluted PSNE and were exposed to high ultrasound pressure. Lesions (1.5~2.5 mm in transverse dimension) were observed 24 hours after the sonications in 4/4 mice. Hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions were formed at the targeted area. On the right side where were sonicated without PSNE, no apparent damaged was observed. Scale bars are 2 mm in (A) and 0.5 mm in (B) and (C).

Figure 6:

Histological appearance of a lesion 24 hours after sonication. (A) Brain tissue necrosis with a loss of tissue structure. (B) High magnification view of the area outlined in black in (A). Extensive hemorrhages occurred at one side of the lesion where large vessels were abundant and were ruptured by the inertial cavitation. The red blood cells were obvious around the damaged vessel. (C) High magnification view of the area outlined in white box in (A). Dead neurons with shrunken nuclei and empty cytoplasm were abundant within the lesion. (D) High magnification view of the area outlined in black in (C). Some tissues close to the edge of the brain appeared spongy and semiliquid suggesting mechanical destruction. Scale bars are 1 mm in (A), 0.2 mm in (B) & (C) and 0.05 mm in (D).

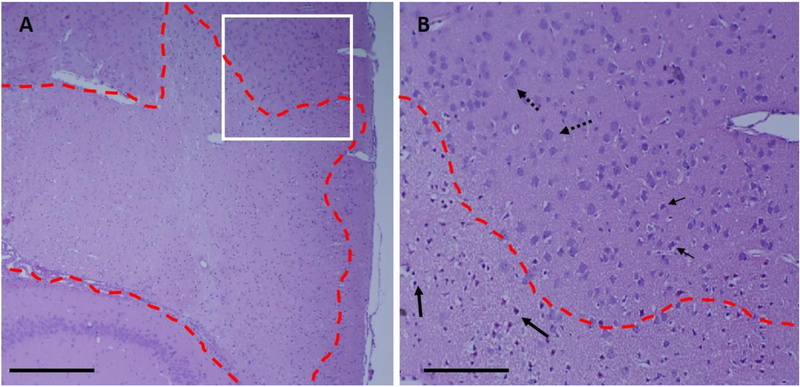

Another example of the lesion from this group is presented in figure 7. The lesion had a sharp boundary with a small transition area about 0.1–0.2 mm wide (figure 7B). The average area of lesion was 6.94 ± 1.26 mm2, which was comparable with the 0.9 MPa transverse contour of the transducer (half of the peak pressure) as is shown in figure 1B (diam ~ 2.5 mm). It can be seen in figure 7 that despite the substantial volume of this lesion in the mouse brain (~ 10 mm), the hippocampus remained undamaged. Dead neurons with shrunk nuclei and without cytoplasm were also observed throughout the lesion and pyknotic nuclei can be seen around the boundary of the lesion (figure 7B).

Figure 7:

Histological example of ischemic lesions with sharp boundary from high pressure and high PSNE concentration group. (A) A lesion was formed at the targeted area that has well-defined boundary (red dash lines) of living and dead cells. (B) Dead neurons with shrunken nucleus and empty cytoplasm(solid arrows) were formed within the circumference of the lesion (red dash lines). Living cells (dotted arrows) were abundant outside of the lesion. There is a transition zone that with some cells with pyknotic nucleus shown by small arrows. Scale bar is 1 mm in (A) and 0.1 mm in (B).

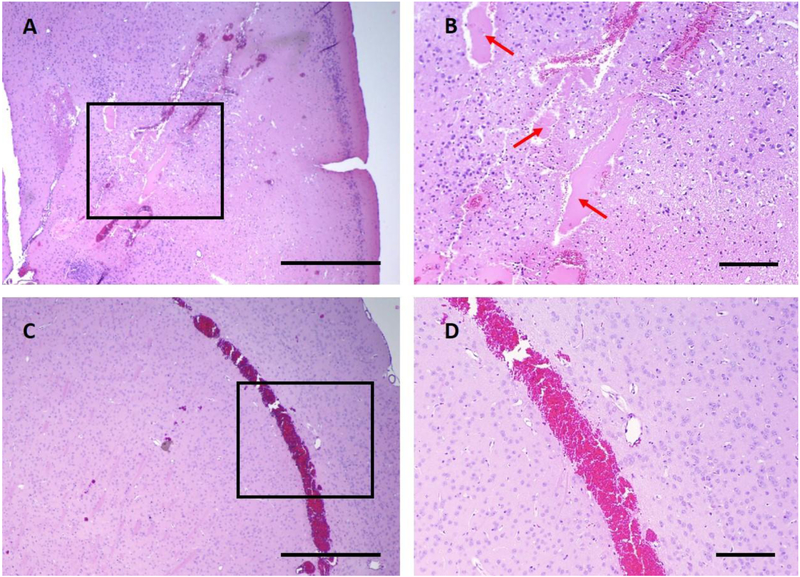

In some subjects, PSNE-enhanced sonications created an empty cavity where proteinaceous fluid filled in and appeared in pink color. This was presumably due to the mechanical destruction of tissues, which created space for fluid to accumulate (figure 8A & 8B). Damage at tissue boundary away from the target was seen in some subjects between white matter and grey matter and at meninges (figure 8C & 8D).

Figure 8:

Histological example of damages appeared less frequently in high pressure and high PSNE concentration group. (A) An empty cavity was created within the lesion (1 out of 4 subjects), and the proteinaceous fluid filled into the cavity. (B) High resolution view of the are in the black box in (A). Proteinaceous fluid is pointed with red arrow. (C) Extensive red blood cell extravasation at the tissue boundary which indicated a strong boundary effect due to the tissue boundary. (D) High resolution view of the area in the black box in (C). Scale bars are 1 mm in (A) & (C) and 0.2 mm in (B) & (D).

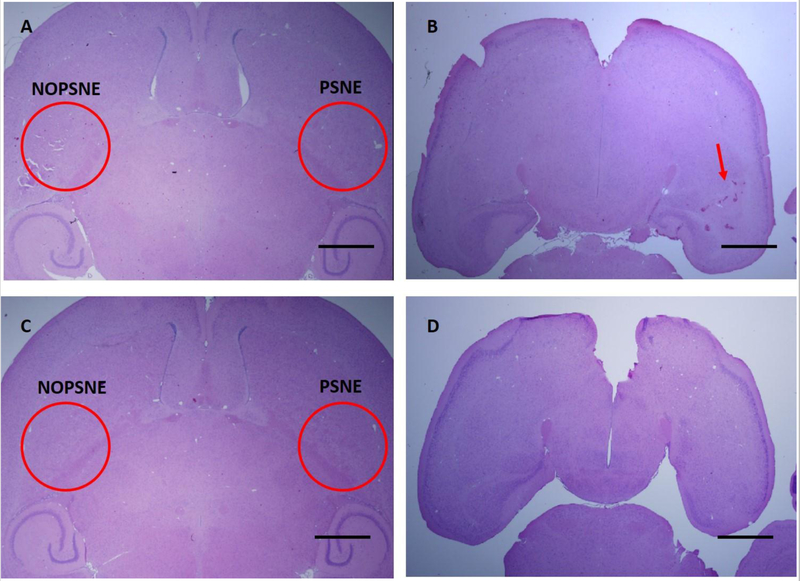

Low pressure (1.5 MPa) and non-diluted PSNE:

Four mice were sonicated with lower pressure (1.5 MPa) and non-diluted PSNE. The pressure used in this group was still higher than the IC threshold determined from the acoustic measurements. In this group, 3 out of 4 subjects had no apparent damage as is shown in figure 9C & 9D. One subject had a hemorrhagic damage close to the base of the brain (figure 9B). However, there was no apparent damage in the slice from the middle of the brain (figure 9A). Considering the ultrasound propagation direction, which was from top to bottom of the skull, this was likely caused by the reflection from the skull, which increased the pressure close to the base of the brain and created unpredictable damage. Also, the resulted lesion was less than 1 mm in diameter, which was smaller than the lesion created for the 1.8 MPa exposures.

Figure 9:

Examples of H&E staining from two subjects that were injected with non-diluted PSNE and sonicated at 1.5 MPa. (A) The slice that was located 3 mm from the bottom of the brain from subject 1. No apparent damage was created by sonication within the targeted area with or without PSNE. (B) H&E slice from the bottom of the brain from subject 1. Red arrow is pointing at the side that was sonicated with PSNE. Some micro-hemorrhage was observed, but it was not as extensive as subjects sonicated at a higher pressure. This was observed only in 1 of the 4 mice. (C) H&E slice that was located 3 mm from the bottom of the brain from subject 2. No apparent damage was found in both side. (D) H&E slice from the bottom of the brain from subject 2. There was no apparent damage at the bottom in both side. Scale bars are 1mm.

High pressure (1.8 MPa) and 5 times diluted PSNE:

Four mice were sonicated with high pressure (1.8 MPa) after administration of 5 times diluted PSNE (1.0 ± 0.3 × 108 injected particles) and no apparent damage was observed in this group. An example histology slide is presented in figure 10. This suggested that a sufficient concentration of PSNE should be administered so that there will be enough IC activity to create the desired bioeffect (i.e. ischemic or hemorrhagic lesion). In all, we can see from these two groups that in order to consistently create lesions in the brain, a relatively high concentration of PSNE should be administered and the ultrasound pressure should exceed the PSNE-nucleated IC threshold.

Figure 10:

H&E staining example of subjects that were injected with 5 times diluted PSNE and were exposed with high ultrasound pressure (1.8 MPa). No apparent damage was found on either side, with or without PSNE. Scale bar is 1mm.

Discussion

In this pilot study, we tested two central hypotheses: 1) circulating PFB-based PSNE could be vaporized in brain blood vessels with sub-MHz transcranial focused ultrasound tone-bursts below 2 MPa, and 2) focal mechanical ablation of brain tissue was possible with PFB-based PSNE combined with sub-MHz FUS. To test the first hypothesis, a 740-kHz FUS transducer transmitted 15-ms tone bursts into the mouse brain through the skull after IV injection of PFB-based PSNE. A PCD sensitive to the f/2 subharmonic of the FUS transducer monitored for inertial cavitation nucleated by vaporized PSNE. A significant increase in average power for the processed PCD signals was observed once the FUS transmitted peak negative pressure (PNP) exceeded 1.2 MPa, suggesting successful vaporization of circulating PFB-based PSNE. This “apparent” threshold for IC activity in the brain sonicated at 740 kHz compared favorably with a recent study in which PFB-based PSNE were vaporized in brain blood vessels with 6.7-ms tone bursts at 1.5-MHz (Wu et al. 2018). In the documented study, significant IC activity was detected via PCD when the transmitted derated PNP was at least 0.9 MPa (Wu et al. 2018), The non-derated PNP based on 18.1% loss due to skull attenuation at 1.5 MHz (Choi et al. 2007) is approximately 1.125 MPa, which is comparable with our non-derated pressure for initiating IC activity at 740 kHz. Importantly, the estimated time-average acoustic power for pulses exceeding the “apparent” IC threshold ranged from 0.11 to 0.24 W. We do not anticipate significant heating in the skull leading to thermal damage at the periphery of the brain at these power levels based on our unpublished studies, and thus we explored these pressures for focal nonthermal ablation of brain tissue.

Reportedly, the mean circulation half-life for PFB-based PSNE is approximately 10 minutes, which is about three times the mean half-life for encapsulated microbubbles (Sheeran et al. 2015). Thus, a single bolus PSNE injection may serve as IC nuclei for several minutes. Our results displayed in figure 4A, which show significant enhancement in acoustic emissions for 10 minutes post-injection of the nanoemulsions, support this idea. Additional bolus injections of PSNE could be administered to maintain an ideal concentration of IC nuclei for longer than ten minutes if needed.

Next, we used histology to analyze the impact of sustained localized IC activity on the brain tissue and blood vessels. We identified contiguous regions of dead tissue (lesions) in all cases where significant IC activity was detected. The lesions appeared to have a sharp boundary between living and dead cells, and the lesions’ size and shape were comparable to the FWHM acoustic pressure contour of the beam plot at the focus of the transducer. In addition, there was less or no damage in the pre-focal region, which was commonly found when other exogenous agents were used to nucleate cavitation (McDannold et al. 2016; Moyer et al. 2015; Phillips et al. 2013). These findings indicate that we could utilize this technique to create a confined lesion at acoustic focus. Comparatively, more severe damage could be found at the post focal region close to skull base, which presumably was due to reflection at the skull wall. Reflections from the skull were expected given the long focus (FWHM: 12 mm) of the transducer relative to the thickness of the mouse brain (6 mm) in this study. A future study using a larger animal or a transducer with a shorter focus would mitigate this problem.

We speculated that cavitation-induced vascular disruption and ischemia would be the predominant mechanism for lesion formation in this technique. Intravascular PSNE vaporization and inertial cavitation can create shock waves and/or high-velocity jets that could damage blood vessels. Cumulative vascular damage may severely disrupt perfusion locally, leading to focal ischemia in the brain. This was supported by observation of microhemorrhage, which was a typical capillary damage reported in bubble-enhanced ablation (McDannold et al. 2006). Lesions were not detected in brain regions where FUS exposures were not above 1.2 MPa or in subjects that were injected with PSNE at low concentration (i.e. 5x diluted). In both cases, acoustic emissions were negligible, which suggests that PSNE-nucleated IC activity was minimal. It is worth noting that the H&E staining of some subjects contained some areas without evidence of ruptured blood vessels or erythrocyte extravasation but still had ischemic lesions (figure 6C & 6D). This is presumably due to the generation of occlusion or constriction of the blood vessels. It has been reported previously that HIFU in combination with ultrasound contrast agents (PSNE or MBs) can occlude blood vessels (Al-Mahrouki et al. 2014b; Hynynen et al. 1996; Hwang et al. 2005; Kripfgans et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2010). Spasms in blood vessels also has been reported in previous work (Raymond et al. 2007). There are several mechanisms through which cavitation may suppress perfusion resulting in ischemia. The intensity and/or duration of cavitation activity may dictate the mechanism of vascular shutdown. As such, it will be essential to control the level of vasculature damage with a feedback system, which could be achieved by an acoustic detection system (O’Reilly and Hynynen 2012; Sun et al. 2017).

There were a few limitations in this pilot study. While we successfully created brain lesions, there were some cases that severe damage and tissue homogenization occurred at the base of the brain, which presumably was caused by reflection. Therefore, use of a larger animal model most likely would resolve this limitation. In addition to that, we did not perform a longitudinal study and therefore lack information regarding the timing for formation of the brain lesions or its impact on the health and survival of the animal. However, the findings of the study do provide valuable information on the parameters that may be utilized for focal ablation of brain tumors in a larger animal model.

Conclusions

In this study, we successfully vaporized PSNE to facilitate the transcranial HIFU mechanical ablation in the brain. The results suggested that PSNE can significantly reduce the time-average power and pressure compared with traditional HIFU thermal ablation. The damage created by PSNE facilitated ablation is consistent with previous bubble facilitated ablation including localized vasculature damaged, ischemic strokes and tissue fragmentation. We are therefore encouraged to further investigate whether we are able to ablate tumor in a glioblastoma model in the future. We foresee that the success of our study could improve the efficacy and efficiency of HIFU ablation and expand the treatment envelop which would benefit more patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants P01CA17464501 and Boston University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital training grant BU-BWH partnership.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Mahrouki AA, Iradji S, Tran WT, Czarnota GJ. Cellular characterization of ultrasound-stimulated microbubble radiation enhancement in a prostate cancer xenograft model. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2014a;7:363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahrouki AA, Iradji S, Tran WT, Czarnota GJ. Cellular characterization of ultrasound-stimulated microbubble radiation enhancement in a prostate cancer xenograft model. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2014b;7:363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz F, Livingstone M, McDannold N. Cavitation-enhanced nonthermal ablation in deep brain targets: feasibility in a large animal model. Journal of Neurosurgery 2016;124:1450–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T, Kawabata K, Umemura S, Ogihara M, Kubota J, Sasaki A, Furuhata H. Bubble Generation by Standing Wave in Water Surrounded by Cranium with Transcranial Ultrasonic Beam. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2005;44:4625–4630. [Google Scholar]

- Baron C, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Meairs S, Fink M. Simulation of Intracranial Acoustic Fields in Clinical Trials of Sonothrombolysis. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2009;35:1148–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CW, Klibanov AL, Sheehan JP, Price RJ. Inhibition of glioma growth by microbubble activation in a subcutaneous model using low duty cycle ultrasound without significant heating: Laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery 2011;114:1654–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaichana KL, Cabrera-Aldana EE, Jusue-Torres I, Wijesekera O, Olivi A, Rahman M, Quinones-Hinojosa A. When Gross Total Resection of a Glioblastoma Is Possible, How Much Resection Should Be Achieved? World Neurosurgery 2014a;82:e257–e265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaichana KL, Jusue-Torres I, Navarro-Ramirez R, Raza SM, Pascual-Gallego M, Ibrahim A, Hernandez-Hermann M, Gomez L, Ye X, Weingart JD, Olivi A, Blakeley J, Gallia GL, Lim M, Brem H, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Establishing percent resection and residual volume thresholds affecting survival and recurrence for patients with newly diagnosed intracranial glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2014b;16:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrois GJR, Allen TM. Rate of biodistribution of STEALTHR liposomes to tumor and skin: influence of liposome diameter and implications for toxicity and therapeutic activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta :7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Pernot M, Small SA, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive, transcranial and localized opening of the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound in mice. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2007;33:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Sun J, Giesecke T, Hynynen K. A hemisphere array for non-invasive ultrasound brain therapy and surgery. Phys Med Biol 2000;45:3707–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccia D, Fandino J, Schwyzer L, O’Gorman R, Remonda L, Anon J, Martin E, Werner B. First noninvasive thermal ablation of a brain tumor with MR-guided focused ultrasound. J Ther Ultrasound 2014;2:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnota GJ, Karshafian R, Burns PN, Wong S, Al Mahrouki A, Lee JW, Caissie A, Tran W, Kim C, Furukawa M, Wong E, Giles A. Tumor radiation response enhancement by acoustical stimulation of the vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012;109:E2033–E2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Garza-Ramos R, Kerezoudis P, Tamargo RJ, Brem H, Huang J, Bydon M. Surgical complications following malignant brain tumor surgery: An analysis of 2002–2011 data. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2016;140:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, Ghanouni P, Kim YG, Lee W, Schwartz M, Hynynen K, Lozano AM, Shah BB, Huss D, Dallapiazza RF, Gwinn R, Witt J, Ro S, Eisenberg HM, Fishman PS, Gandhi D, Halpern CH, Chuang R, Butts Pauly K, Tierney TS, Hayes MT, Cosgrove GR, Yamaguchi T, Abe K, Taira T, Chang JW. A Randomized Trial of Focused Ultrasound Thalamotomy for Essential Tremor. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;375:730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiilli ML, Haworth KJ, Sebastian IE, Kripfgans OD, Carson PL, Fowlkes JB. Delivery of Chlorambucil Using an Acoustically-Triggered Perfluoropentane Emulsion. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2010;36:1364–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfelice D, Gupta C, Kucharczyk W, Bret P, Havill D, Clemons M. Palliative Treatment of Painful Bone Metastases with MR Imaging–guided Focused Ultrasound. Radiology 2008;249:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesecke T, Hynynen K. Ultrasound-mediated cavitation thresholds of liquid perfluorocarbon droplets in vitro. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2003;29:1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Vykhodtseva NI, Hynynen K. Creating Brain Lesions with Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound with Microbubbles: A Rat Study at Half a Megahertz. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2013;39:1420–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss DS, Dallapiazza RF, Shah BB, Harrison MB, Diamond J, Elias WJ. Functional assessment and quality of life in essential tremor with bilateral or unilateral DBS and focused ultrasound thalamotomy: Functional Assessment of ET Treated by DBS or FUS. Movement Disorders 2015;30:1937–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JH, Brayman AA, Reidy MA, Matula TJ, Kimmey MB, Crum LA. Vascular effects induced by combined 1-MHz ultrasound and microbubble contrast agent treatments in vivo. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2005;31:553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K THE THRESHOLD FOR THERMALLY SIGNIFICANT CAVITATION IN DOG’S THIGH MUSCLE IN VZVO. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology 1990;13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, Colucci V, Chung A, Jolesz F. Noninvasive arterial occlusion using MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 1996;22:1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida O, Maruyama K, Sasaki K, Iwatsuru M. Size-dependent extravasation and interstitial localization of polyethyleneglycol liposomes in solid tumor-bearing mice. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1999;190:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Junho, Pulkkinen A, Huang Yuexi, Hynynen K Investigation of Standing-Wave Formation in a Human Skull for a Clinical Prototype of a Large-Aperture, Transcranial MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) Phased Array: An Experimental and Simulation Study. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012;59:435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsy M, Yoon N, Boettcher L, Jensen R, Shah L, MacDonald J, Menacho ST. Surgical treatment of glioblastoma in the elderly: the impact of complications. J Neurooncol 2018;138:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlova TD, Wang Y-N, Simon JC, Cunitz BW, Starr F, Paun M, Crum LA, Bailey MR, Khokhlova VA. Ultrasound-guided tissue fractionation by high intensity focused ultrasound in an in vivo porcine liver model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014;111:8161–8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlova VA, Fowlkes JB, Roberts WW, Schade GR, Xu Z, Khokhlova TD, Hall TL, Maxwell AD, Wang Y-N, Cain CA. Histotripsy methods in mechanical disintegration of tissue: Towards clinical applications. International Journal of Hyperthermia 2015;31:145–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch MO, Gardner T, Cheng L, Fedewa RJ, Seip R, Sangvhi NT. Phase I/II Trial of High Intensity Focused Ultrasound for the Treatment of Previously Untreated Localized Prostate Cancer. The Journal of Urology 2007;178:2366–2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopechek JA, Park E-J, Zhang Y-Z, Vykhodtseva NI, McDannold NJ, Porter TM. Cavitation-enhanced MR-guided focused ultrasound ablation of rabbit tumors in vivo using phase shift nanoemulsions. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2014;59:3465–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripfgans OD, Ives KA, Eldevik OP, Fowlkes JB. Acoustic Droplet Vaporization for Temporal and Spatial Control of Tissue Occlusion: A Kidney Study. 2005;52:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. Journal of Controlled Release 2000;65:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AD, Wang T-Y, Cain CA, Fowlkes JB, Sapozhnikov OA, Bailey MR, Xu Z. Cavitation clouds created by shock scattering from bubbles during histotripsy. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2011;130:1888–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Clement GT, Black P, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Transcranial Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Focused Ultrasound Surgery of Brain Tumors. Neurosurgery 2010;66:323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Zhang Y, Vykhodtseva N. Nonthermal ablation in the rat brain using focused ultrasound and an ultrasound contrast agent: long-term effects. Journal of Neurosurgery 2016;125:1539–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Zhang Y-Z, Power C, Jolesz F, Vykhodtseva N. Nonthermal ablation with microbubble-enhanced focused ultrasound close to the optic tract without affecting nerve function: Laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery 2013;119:1208–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold NJ, Vykhodtseva NI, Hynynen K. Microbubble Contrast Agent with Focused Ultrasound to Create Brain Lesions at Low Power Levels: MR Imaging and Histologic Study in Rabbits. Radiology 2006;241:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer LC, Timbie KF, Sheeran PS, Price RJ, Miller GW, Dayton PA. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation enhancement in vivo via phase-shift nanodroplets compared to microbubbles. Journal of Therapeutic Ultrasound 2015. [cited 2018 Jul 15];3 Available from: http://www.jtultrasound.com/content/3/1/7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T, Koreeda N, Yamashita F, Takakura Y, Hashida M. Effect of particle size and charge on the disposition of lipid carriers after intratumoral injection into tissue-isolated tumors. Pharm Res 1998;15:128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K. Blood-Brain Barrier: Real-time Feedback-controlled Focused Ultrasound Disruption by Using an Acoustic Emissions–based Controller. Radiology 2012;263:96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Gulf Professional Publishing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LC, Puett C, Sheeran PS, Dayton PA, Wilson Miller G, Matsunaga TO. Phase-shift perfluorocarbon agents enhance high intensity focused ultrasound thermal delivery with reduced near-field heating. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2013;134:1473–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond SB, Skoch J, Hynynen K, Bacskai BJ. Multiphoton Imaging of Ultrasound/Optison Mediated Cerebrovascular Effects in vivo. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2007;27:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WW, Hall TL, Ives K, Wolf JS, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. Pulsed Cavitational Ultrasound: A Noninvasive Technology for Controlled Tissue Ablation (Histotripsy) in the Rabbit Kidney. The Journal of Urology 2006;175:734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad KC, Hynynen K. In vitro characterization of perfluorocarbon droplets for focused ultrasound therapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2010a;55:4933–4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad KC, Hynynen K. In vitro characterization of perfluorocarbon droplets for focused ultrasound therapy. Phys Med Biol 2010b;55:4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran PS, Luois S, Dayton PA, Matsunaga TO. Formulation and Acoustic Studies of a New Phase-Shift Agent for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Ultrasound. Langmuir 2011;27:10412–10420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran PS, Luois SH, Mullin LB, Matsunaga TO, Dayton PA. Design of ultrasonically-activatable nanoparticles using low boiling point perfluorocarbons. Biomaterials 2012;33:3262–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran PS, Matsunaga TO, Dayton PA. Phase-transition thresholds and vaporization phenomena for ultrasound phase-change nanoemulsions assessed via high-speed optical microscopy. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2013;58:4513–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran PS, Rojas JD, Puett C, Hjelmquist J, Arena CB, Dayton PA. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging and in Vivo Circulatory Kinetics with Low-Boiling-Point Nanoscale Phase-Change Perfluorocarbon Agents. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2015;41:814–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Rabinovici J, Tempany CMC, Inbar Y, Regan L, Gastout B, Hesley G, Kim HS, Hengst S, Gedroye WM. Clinical outcomes of focused ultrasound surgery for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertility and Sterility 2006;85:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, Hanes J, Ensign LM. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016;99:28–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Zhang Y, Power C, Alexander PM, Sutton JT, Aryal M, Vykhodtseva N, Miller EL, McDannold NJ. Closed-loop control of targeted ultrasound drug delivery across the blood–brain/tumor barriers in a rat glioma model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017;114:E10281–E10290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaisavljevich E, Lin K-W, Maxwell A, Warnez MT, Mancia L, Singh R, Putnam AJ, Fowlkes B, Johnsen E, Cain C, Xu Z. Effects of Ultrasound Frequency and Tissue Stiffness on the Histotripsy Intrinsic Threshold for Cavitation. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2015;41:1651–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-N, Khokhlova T, Bailey M, Hwang JH, Khokhlova V. Histological and Biochemical Analysis of Mechanical and Thermal Bioeffects in Boiling Histotripsy Lesions Induced by High Intensity Focused Ultrasound. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2013;39:424–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Moehring MA, Voie AH, Furuhata H. In vitro evaluation of dual mode ultrasonic thrombolysis method for transcranial application with an occlusive thrombosis model. Ultrasound in medicine & biology 2008;34:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M, van den Bent M, Hopkins K, Tonn JC, Stupp R, Falini A, Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal E, Frappaz D, Henriksson R, Balana C, Chinot O, Ram Z, Reifenberger G, Soffietti R, Wick W. EANO guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of anaplastic gliomas and glioblastoma. The Lancet Oncology 2014;15:e395–e403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Clement GT, Hynynen K. Longitudinal and shear mode ultrasound propagation in human skull bone. 2006;27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S-K, Chu P-C, Chai W-Y, Kang S-T, Tsai C-H, Fan C-H, Yeh C-K, Liu H-L. Characterization of Different Microbubbles in Assisting Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. Scientific Reports 2017;7:46689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S-Y, Fix SM, Arena CB, Chen CC, Zheng W, Olumolade OO, Papadopoulou V, Novell A, Dayton PA, Konofagou EE. Focused ultrasound-facilitated brain drug delivery using optimized nanodroplets: vaporization efficiency dictates large molecular delivery. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2018;63:035002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Fowlkes JB, Rothman ED, Levin AM, Cain CA. Controlled ultrasound tissue erosion: The role of dynamic interaction between insonation and microbubble activity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2005;117:424–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular Permeability in a Human Tumor Xenograft: Molecular Size Dependence and Cutoff Size. :6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Fabiilli ML, Haworth KJ, Fowlkes JB, Kripfgans OD, Roberts WW, Ives KA, Carson PL. Initial Investigation of Acoustic Droplet Vaporization for Occlusion in Canine Kidney. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2010;36:1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Kopechek JA, Porter TM. The impact of vaporized nanoemulsions on ultrasound-mediated ablation. 2013;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Porter T. An in vitro Study of a Phase-Shift Nanoemulsion: A Potential Nucleation Agent for Bubble-Enhanced HIFU Tumor Ablation. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2010;36:1856–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Ding Y, Cain CA. Non-invasive Thrombolysis using Histotripsy beyond the “Intrinsic” Threshold (Microtripsy). 2015;35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]