Abstract

Existing high-throughput methods to identify RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) involving capture of polyadenylated RNAs can not recover proteins that interact with non-adenylated RNAs, including lncRNA, pre-mRNA and bacterial RNAs. We present orthogonal organic phase separation (OOPS) which does not require molecular tagging or capture of polyadenylated RNA. We verify OOPS in HEK293, U2OS and MCF10A human cell lines, finding 96% of proteins recovered are bound to RNA. We demonstrate that all long RNAs can be crosslinked to proteins and recover 1838 RBPs, including 926 putative novel RBPs. Importantly, OOPS is approximately 100-fold more efficient than current techniques, enabling analysis of dynamic RNA-protein interactions. We identified 749 proteins with altered RNA binding following release from nocodazole arrest. Finally, OOPS allowed the characterisation of the first RNA-interactome for a bacterium, Escherichia coli. OOPS is an easy to use and flexible technique, compatible with downstream proteomics and RNA sequencing and applicable to any organism.

Introduction

Interactions between RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and RNA regulate transcription and transcript trafficking, decay and translation1–7 thereby modulating cell homeostasis and cell fate. Several approaches are available to characterise RNA-RBP interactions: Protein-Bound RNAs (PBRs) can be purified by immunoprecipitating a specific protein and sequencing its RNA cargo8,9. In addition, the cellular repertoire of polyadenylated RNA-binding proteins can be recovered by UV crosslinking RNA-RBP complexes, capturing RNA by oligo(dT), and subsequently identifying bound proteins10–12. However, current methods to study PBRs are challenging to scale up for a systems-wide analysis of RBPs and PBRs, while oligo(dT)-based purification requires a very large amount of starting material, complicating its application in dynamic conditions13. Furthermore, the requirement for polyA-tails means that oligo(dT)-based methods cannot be used for bacterial systems or eukaryotic non-polyadenylated RNAs. Published methods based on incorporation of modified nucleotides have tried to address these limitations, but they can introduce biases due to transcription-dependent nucleoside-incorporation14–16.

We have developed a method based on Acidic Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform (AGPC) phase partition, that we name Orthogonal Organic Phase Separation (OOPS). AGPC purification enables unbiased recovery of RNA species17,18, by generating two distinct phases: RNA migrating to the upper aqueous phase and proteins occupying the lower organic phase. UV crosslinking at 254 nm generates RNA-protein adducts that combine the physicochemical properties of both molecules and migrate to the aqueous-organic interface19 . We hypothesized that isolation of the interface would enable specific recovery of RBPs or PBRs by digesting the reciprocal component of the adduct.

Here, we report validation and application of OOPS. Separation of free and protein-bound RNA provides a way to quantify the proportion of RNA crosslinked to protein, enabling precise UV dosage optimisation. We show that OOPS recovers all crosslinked-RNA (CL-RNA), including lncRNA, and all crosslinked RBPs. Using the cytostatic agent nocodazole, we identify RNA-binding changes between arrested and released cells for metabolic enzymes and splicing regulators. Finally, we characterise the first bacterium RNA-interactome, confirming that OOPS can retrieve RNA-RBPs in any organism.

Results

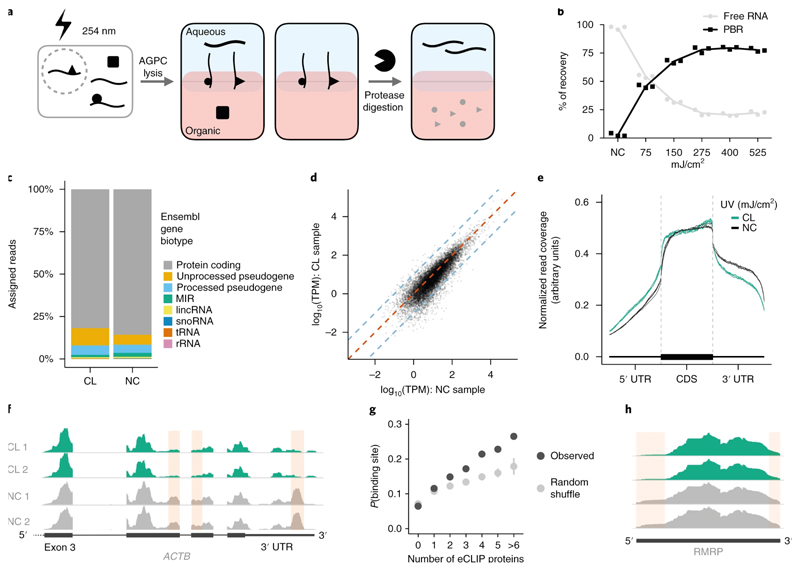

Recovery of protein-bound RNA

Cell lysis in Acidic Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol followed by addition of chloroform produces two distinct phases: an aqueous (upper) phase containing RNA and an organic (lower) phase containing proteins. We hypothesized that UV-crosslinking at 254 nm would produce stable RNA-protein adducts that would be retained at the interface between the phases (Figure 1a). CL-RNA was recovered from the interface by protein digestion using proteinase-K and extraction from the aqueous phase of a subsequent phase separation (Figures 1a-b, online methods). RNA migration from the interface to the aqueous phase after protein digestion indicates that its previous presence at the interface was protein binding-dependent. We observed a UV dose-dependent migration of RNA from the aqueous phase to the interface, saturating at approximately 75% of the total RNA content (Figures 1b; Figure S1a). This indicates that all crosslinked RNAs can be recovered from the interface. The size profile of CL-RNA resembles total free-RNA of a non-crosslinked sample (NC), with the aqueous phase of the CL sample containing free small RNAs (Figure S1b), suggesting that small RNAs may be less frequently crosslinked with proteins.

Figure 1. OOPS recovers protein-bound RNAs.

(a) Schematic representation of the OOPS method to extract protein-bound RNA. Cells are crosslinked to induce RNA-proteins adducts which are drawn simultaneously to the organic and aqueous phases in Acid Guanidinium-Phenol-Chloroform (AGPC) and thus remain at the interface. Protease digestion and a further AGPC separation yields RNA in the aqueous phase.

(b) Relative proportions of free RNA (aqueous phase) and protein-bound RNA (PBR; interface) with increasing UV dosage. Data shown as mean +/- SD of 3 independent experiments.

(c) Relative proportions of RNA-Seq reads assigned to Ensembl gene biotypes for 400 mJ/cm2 CL and NC samples.

(d) Correlation between gene abundance estimates for NC replicate 1 and 400 mJ/cm2 CL replicate 1. Blue dashed lines represent a 10-fold difference. Red dashed line represents equality.

(e) Meta-plot of read coverage over protein-coding gene-model. Reduced coverage observed for 400 mJ/cm2 CL samples in the 3' UTR.

(f) Read coverage across ACTB for CL (400 mJ/cm2) and NC replicates. Red boxes denote regions with consistently reduced coverage in CL.

(g) Relationship between the number of eCLIP proteins with a peak in a sliding window and the probability of the window being identified as a protein binding site. For random shuffle, the center value is the mean and error bar is 2 standard deviations, n = 100 iterations.

(h) Read coverage across RMRP for CL (400 mJ/cm2) and NC replicates. Red boxes denote regions with consistently reduced coverage in CL.

Non-crosslinked=NC, Crosslinked=CL.

We compared the relative abundance of RNAs in crosslinked and non-crosslinked samples using RNA-seq. Ribosomal RNA was depleted and total RNA-seq carried out on samples exposed to varying UV dosages (150-400 mJ/cm2; Figure S1c). The abundance of RNA species in CL-RNA and NC-RNA samples was similar, with protein-coding mRNAs predominating (Figures 1c, S1d). Crucially, the Pearson correlation between CL and NC samples was as high as that in crosslinked samples (median correlations are 0.89 and 0.92, respectively; Figures 1d, S1e) and as RNA size does not affect abundance in the interface post-CL, these data suggest that all crosslinked RNAs over 60 bp are recovered without any systematic bias (Figure S1f).

Despite the high correlation between RNA abundance in CL and NC samples, we observed an overall reduction of coverage in the 3’ UTRs of mRNAs (Figures 1e) and a loss of coverage at discrete positions (Figure 1f). We hypothesized that this was due to steric hindrance of reverse transcription at sites of RNA-protein crosslinking, as protein-RNA binding occurs frequently within the 3’ UTR20. We therefore applied a sliding window approach to identify ‘loss of coverage’ sites in the CL samples transcriptome (supplementary note). Loss of coverage occurs more frequently in mRNA 3’ UTRs and sites significantly overlap with ENCODE eCLIP protein-binding peaks21, confirming that they represent protein binding (Figure 1g, S1g). An alternative explanation is that adjacent uracils can photo-dimerize with 254 nm UV, generating adducts that block reverse transcription22. Regions of RNA with high uracil content, which preferentially crosslink to proteins at 254 nm, are more likely to contain a detectable loss of coverage, but adjacent uracils have no effect (Figure S1h). Protein-RNA crosslinking is the most likely cause of observed differences in read coverage and OOPS can therefore identify protein-binding footprints.

Identification of discrete protein-binding sites was restricted to coding genes since these are more highly expressed. We also manually inspected highly expressed lncRNAs and observe a loss of coverage at Small nucleolar RNA host gene 16 (SNHG16) and RNA Component of Mitochondrial RNA Processing Endoribonuclease (RMRP; Figure 1h & S1i). RMRP has two functions: initiating mitochondrial DNA replication and RNA processing. The 5’ site we identify matches the previously identified binding sites for the multi-function RBP HuR23, which promotes RMRP migration from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria24. However, confirmation that this loss of coverage is directly due to HuR binding needs an orthogonal approach.

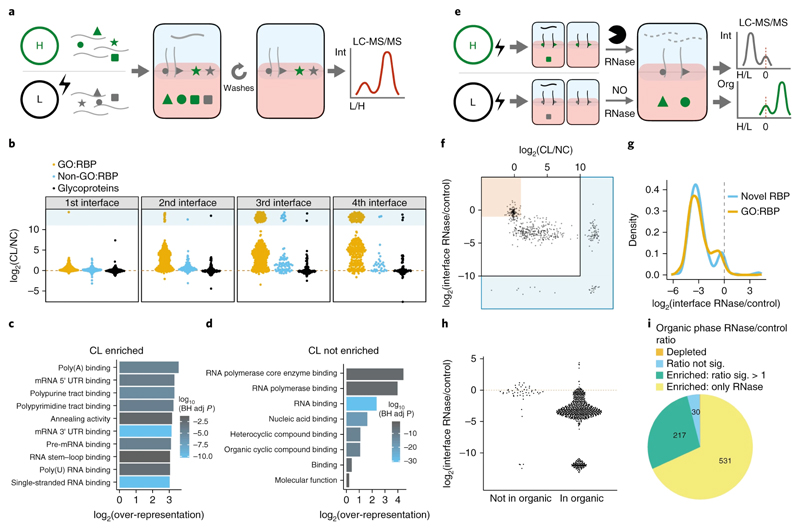

Recovery of RNA-binding proteins

Next, we identified proteins crosslinked to RNA. Notably, this required less than 1% of the cells needed in previous RBP-capture methods10,25 (online methods). First, we used stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)26 to determine the relative abundance of proteins from CL and NC U2OS cells in the same OOPS interface (Figure 2a; online methods). Repeated phase separation removed non-crosslinked proteins with three repeat separations optimal (Figures 2b, S2a, supplementary table 1). As glycosylated proteins share the physicochemical properties of RNA-protein adducts, their presence at the interface is CL-independent. In contrast, non-glycosylated proteins show a similar CL-enrichment, whether or not they are GO-annotated as RBPs (Figures 2b). These data confirm that crosslinking enriches RBPs in the interface.

Figure 2. OOPS for RBP recovery.

(a) Schematic representation of the SILAC experiment used to determine the effect of UV crosslinking on protein abundance in the interface and the effect of additional phase separation cycles to wash the interface. Equal quantities of cells +/- UV crosslinking are labelled with SILAC and mixed prior to OOPS. RNA bound proteins are expected to have a positive CL vs NC ratio. Contaminants are expected to be equally abundant in CL and NC.

(b) Protein CL vs NC ratios for the 1st to 4th interfaces. Infinite ratios (not detected in NC) are presented as pseudo-values in blue box. GO:RBP = GO annotated RNA binding protein.

(c) Top 10 molecular function GO terms over-represented in proteins enriched by CL in the 3rd interface. BH adj p-value = Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value. P-value obtained from a modified hypergeometric test to account for protein abundance (see online methods).

(d) As per (c) for proteins not enriched by CL in the 3rd interface.

(e) Schematic representation of the SILAC experiment to determine protein abundance in the 3rd interface and 4th organic phase following RNase treatment. Equal quantities of cells were UV crosslinked and RNA-protein adducts enriched by OOPS +/- RNase before combining the samples for a final phase separation in which both the interface and the organic phase are collected. Proteins from RNase treated cells will be depleted from the interface and enriched in the organic phase.

(f) Protein CL vs NC ratio and RNase vs control ratio in the interface. Red box denotes proteins which are not CL-enriched and not depleted by RNase. The blue regions surrounding the graph denote ratios which cannot be accurately estimated as the protein was only detected in one condition and therefore a pseudo-value is presented.

(g) RNase vs control ratio in the interface for GO annotated RBPs and other OOPS RBPs

(h) Protein RNase vs control ratio in the interfaces for proteins identified in the 4th step organic phase. Red line = equal intensity in RNase-treated and control.

(i) Proportion of proteins enriched in the organic phase following RNase treatment. Proteins detected in both +/- RNase conditions but with insufficient peptides to test for significant enrichment are excluded.

Excluding glycoproteins, 73% of proteins were enriched at the 3rd interface post UV-crosslinking (Figure S2b,d,e). A similar proportion of proteins were enriched with a lower UV dosage (150 mJ/cm2; Figure S2e). CL-enriched proteins showed a clear over-representation of RNA-related GO terms (Figure 2c). Within the CL-independent proteins, after accounting for protein abundance, there was a clear over-representation of RNA-binding GO terms (Figure 2d), suggesting that CL-enrichment alone is not sufficient to distinguish free proteins from RNA-bound proteins.

In order to establish that the presence of the proteins at the interface was RNA-dependent, we treated the interfaces with ribonucleases (RNase), and measured protein migration to the organic phase (Figure 2e; online methods, Figures S2f-g). Proteins that migrated to the organic phase included those that were CL-independent, suggesting their presence in the interface is RNA-dependent, but their interaction with RNA was stable even in the absence of CL (Figure 2f, S2h). Moreover, proteins not annotated as RBPs show similar RNase sensitivity to those annotated as RBPs, suggesting they may be undiscovered RBPs (Figure 2g). In contrast, glycoprotein abundance at the interface was unaffected by RNase (Figure S2i). Since the presence of glycoproteins at the interface was also CL-independent (Figure 2i), we excluded them from downstream analyses. Ninety-three percent of proteins in the organic phase were RNase sensitive, whereas those absent were largely RNase insensitive (Figure 2h). Ninety-six percent of proteins extracted from the organic phase showed an enrichment following RNase treatment (Figure 2i) and a clear over-representation of GO terms related to RNA binding (Figure S2j). Moreover, canonical RBPs were in the organic phase after RNase treatment (Figure S2f, supplementary note). Together, these experiments in U2OS cells show that RNase treatment is necessary. Similar results were found in HEK293 cells (Figure S2c-e and g-i).

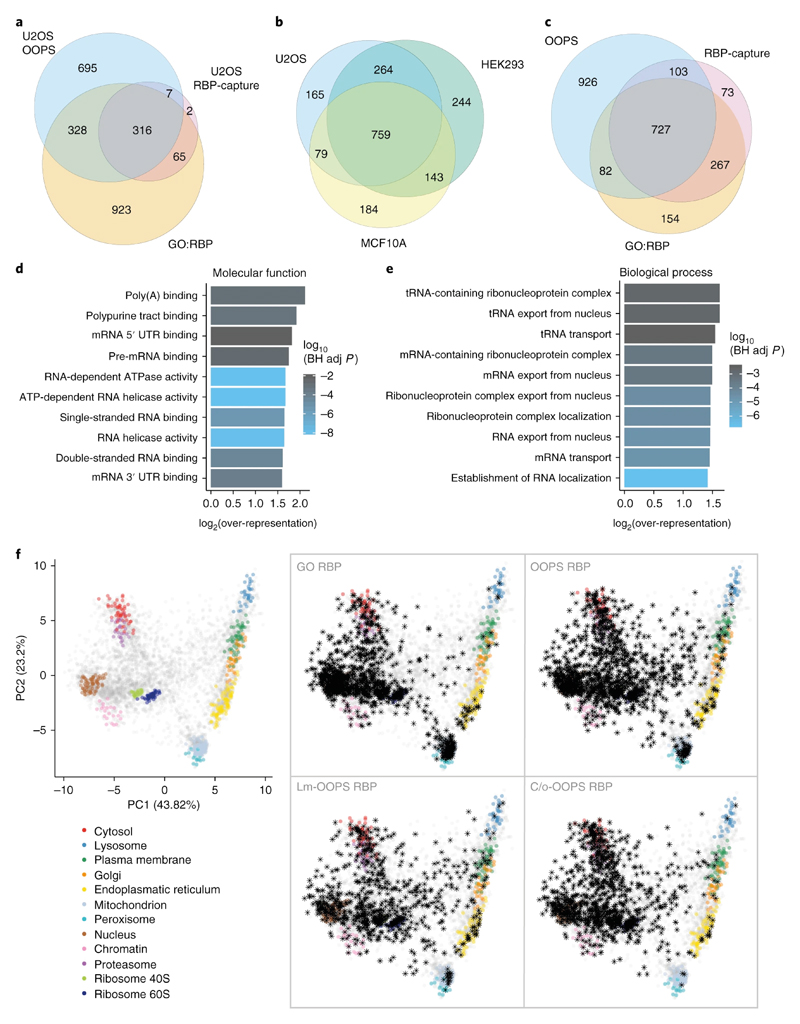

OOPS identifies canonical and novel RBPs

RBPs identified using OOPS were compared with those from oligo(dT) RBP-Capture analysis. Eighty-three percent of proteins identified by RBP-capture in U2OS cells were also identified by OOPS (Figure 3a, S3a). For proteins identified using only one method, there was significant over-representation of GO-annotated RBPs (p-value < 2.2e-16, Fisher's Exact Test). We applied OOPS to MCF10A (a cell line derived from a healthy individual) and HEK293, and observed a “common” RBPome of 759 proteins in all 3 cell lines (Figure 3b, S3b, supplementary table 2). Interestingly, the 264 proteins that were specific to the tumour-derived cell lines had an over-representation of cell cycle RBPs (Figure S3c), indicating previous RBP cataloging experiments in these cell lines may have identified RBPs with limited RNA binding in non-tumour cells. A comparison of the 1838 proteins from the 3 cell lines used in this study with all previous human RBP-capture data, showed 71% identity (Figure 3c). In addition, OOPS identified 80% of the proteins isolated by polyA-independent RICK15 and CARIC14 methods (Figure S3d-e). These results indicate that OOPS recovers most of the annotated RBPome, including proteins that do not bind poly-adenylated RNAs.

Figure 3. RBPs identified using OOPS.

(a) Overlap between OOPS, RBP-Capture and GO-annotated proteins for U2OS cells. Proteins were restricted to those expressed in U2OS.

(b) Overlap between proteins identified with OOPS from U2OS, HEK293 and MCF10A. Proteins were restricted to those expressed in all cell lines.

(c) Overlap between the union of OOPS RBPs identified in the 3 cell lines in (b), all published RBP-Capture studies, and GO annotated RBPs. Proteins were restricted to those expressed in all 3 OOPS cell lines.

(d) Top 10 molecular function GO terms over-represented in the proteins identified in U2OS OOPS. BH adj p-value = Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value. P-value obtained from a modified hypergeometric test to account for protein abundance (see online methods).

(e) As per (d) for novel U2OS RBPs identified by OOPS.

(f) HyperLOPIT projections of protein steady state localisation. Left: Canonical subcellular localisation markers indicated in colour as shown. Right: Highlighted RBPs shown as black asterisks. GO RBP = GO annotated RBP. Lm = Light membrane-enriched fraction. C/o = Cytoplasm/Other fraction. Annotated proteins in each fraction were detected in at least one of 5 repeat experiments.

As expected, OOPS RBPs show an over-representation of GO terms describing all forms of RNA-binding, including 5’ and 3’ UTR sites, and single and double-stranded RNA-binding (Figure 3d, S3f-g). Previously unknown RBPs identified by OOPS show an over-representation of GO terms related to mRNA transport and RNA localisation (Figure 3e, S3h). We projected OOPS RBPs onto our published hyperLOPIT data27, which identifies the average localisation of proteins, as an initial indication of the subcellular distribution of the RNA-bound fraction. Known RBPs mainly localised to the nucleus, mitochondria, cytosol and large protein complexes (e.g. ribosomes; Figure 3f), whereas previously undetected RBPs were more broadly distributed with a greater proportion of membrane proteins and proteins of indeterminate localisation (Figure 3f). Since membrane proteins are generally underrepresented in mass spectrometry experiments, we performed a crude cell fractionation to separate cellular compartments into 3 fractions: “heavy membranes” (e.g. nucleus, mitochondria), “light membranes” (e.g. endoplasmic reticulum, plasma membrane, etc.) and “cytosol” (Figure S3i, supplementary note) and confirmed that transmembrane domain-containing RBPs were more abundant in membrane fractions (Figure S3j). RBPs were detected from all fractions with the membrane fractions yielding more previously unknown membrane-RBPs and RBPs that are known to function in RNA trafficking (Figures 3f, supplementary table 3). Most of the trafficking RBPs are related to the nuclear pore complex and the transport between nucleus and cytoplasm, but we also identified Unconventional Myosin-1C (MYO1C) which is involved in the movement of GLUT4-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane28,29 and associated with the RNA polymerase II in the nucleus30. Our hyperLOPIT data indicates the steady-state localisation of MYO1C is in the secretory pathway, suggesting its RNA binding may have a role in RNA trafficking. Combining OOPS with fractionation thus recovers RBPs from previously underrepresented compartments.

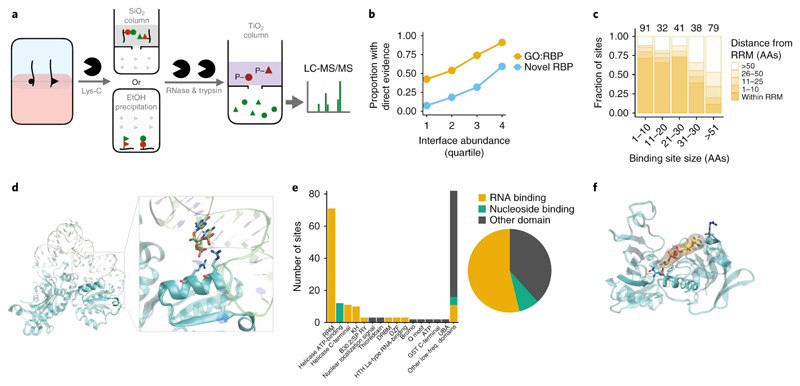

High-throughput validation of RBPs

To validate the identified RBPs and map their RNA-binding sites, we developed a method to identify RNA-binding sites based on RBD-map25 (online methods; Figure 4a). The RNA-peptide enrichment techniques used were orthogonal to OOPS to provide independent validation of RNA binding capacity. Detected trypsin peptides can be mapped to the Lys-C RNA-peptide to determine the RNA binding region. Where possible, this region is further refined based on the presence/absence of expected trypsin peptides across the Lys-C peptides since trypsin RNA-peptides will not be identified due to the variable mass shift of the RNA-peptide adduct (Figure S4a-b; see online methods). Not all RNA binding sites are amenable to the sequential LysC-Trypsin digestion approach due to the requirements for relative positions of lysine and arginine residues (Figure S4a). Despite this, we identified discrete putative RNA-binding sites in 544 (40%) of OOPS U2OS proteins using the adjacent peptides. This validation rate compares favourably with the 30% of RBP-Capture proteins where an RNA binding site could be identified via sequential digestion using RBD-map25. As expected, putative binding sites were more easily identified in proteins with a higher abundance in the interface, with a binding site identified for 59% of the most abundant novel RBPs (Figure 4b, supplementary table 4).

Figure 4. Crosslink site analyses validates OOPS RBPs.

(a) Schematic representation of the sequential digestion method used to identify the RNA-binding site. RNA-protein adducts are extracted from the interface and digested with Lys-C to yield RNA-peptides which are subsequently enriched by silica affinity column or ethanol precipitation. Enriched RNA-peptides are treated with RNases followed by trypsin digestion. Peptides containing the UV-crosslinked nucleotide/RNA are retained by a TiO2 affinity column and the unbound fraction containing the peptide sequences adjacent to RNA crosslinking site is analysed by LC-MS/MS. Red=peptides containing site of crosslinking. Green=peptides adjacent to the RNA-binding site peptide.

(b) Proportion of OOPS RBPs in which a putative RNA-binding site was identified. Proteins separated into GO annotated RBPs and novel RBPs, and by their abundance at the OOPS interface.

(c) Distance of putative RNA-binding sites to the nearest RRM. Smaller putative RNA-binding sites are closer to RRM. Counts for each size range shown above bars.

Analysis restricted to proteins with an RRM.

(d) Crystal structure of Glycyl-tRNA synthetase in complex with tRNA-Gly (PDB ID 4KR2). RNA is shown as transparent lime ribbon; Glycyl-tRNA synthetase is shown in a cyan transparent cartoon representation. The putative RNA binding peptide is shown in an opaque representation and RNA and protein residues at 4 Å or less from each other are shown as lime and cyan sticks respectively.

(e) The number of putative RNA-binding site which intersect an Interpro-annotated protein domain. Domains classified as RNA or nucleotide binding or other.

(f) Crystal structure of GAPDH complexed with NAD (PDB ID 4WNC). GAPDH is shown as a cyan transparent cartoon; putative RNA binding peptide is shown in an opaque representation. Residues at 4 Å or less from NAD (yellow sticks and surface representation) are shown as cyan sticks.

To confirm the specificity of our approach, we focused on proteins containing annotated RNA-recognition motifs (RRM)s, and observed a substantial overlap between identified sites and RRMs (Figure 4c). To further test these sites, we inspected published structures of RBP-RNA complexes. For example, the crystal structure of the glycyl-tRNA synthetase in complex with tRNA-Gly31 confirms that the detected binding site is less than 4 Å from the tRNA (Figure 4d). We further observed protein-RNA contacts in 17 proteins of the ribosome quality control complex structure previously detected using RBP-Capture, together with a novel RBP detected by OOPS32 (Figure S4c). Finally, we established that our method identifies known RNA-binding domains in GO annotated RBPs, including the canonical RRM and KH domains, and non-canonical helicase C-terminal33,34 and DZF25 domains (Figure 4e). Alongside these non-canonical RNA-binding domains, we identified multiple NAD-binding domains. These included two sites within the NAD-binding pocket of GAPDH35, which confirmed previous RNA-binding site predictions based on in vitro experiments36 (Figure 4f). Importantly, proteins with assigned RNA binding sites include some pharmacological targets. We found 21 proteins with known inhibitors in the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology37, 5 of which are targets of currently approved drugs. Analysis of structural information on these drug targets revealed that the detected RNA binding sites overlapped with the binding sites of the antiviral ribavirin to IMPDH2 (Figure S4d) and of antitumoral PARP1 inhibitors like rucaparib (Figure S4e). This surprising observation of shared interaction sites for RNA and drugs indicates that future studies would benefit from considering the RNA-binding role of these proteins.

Assessment of RNA-binding in a dynamic system

Next, we applied OOPS to a dynamic system using a microtubule depolymerizing agent. Microtubule depolymerizing drugs arrest cells in prometaphase by inhibiting chromosome alignment and segregation, and affect a wide range of other cellular processes like intracellular transport and mitochondrial replication38–43.

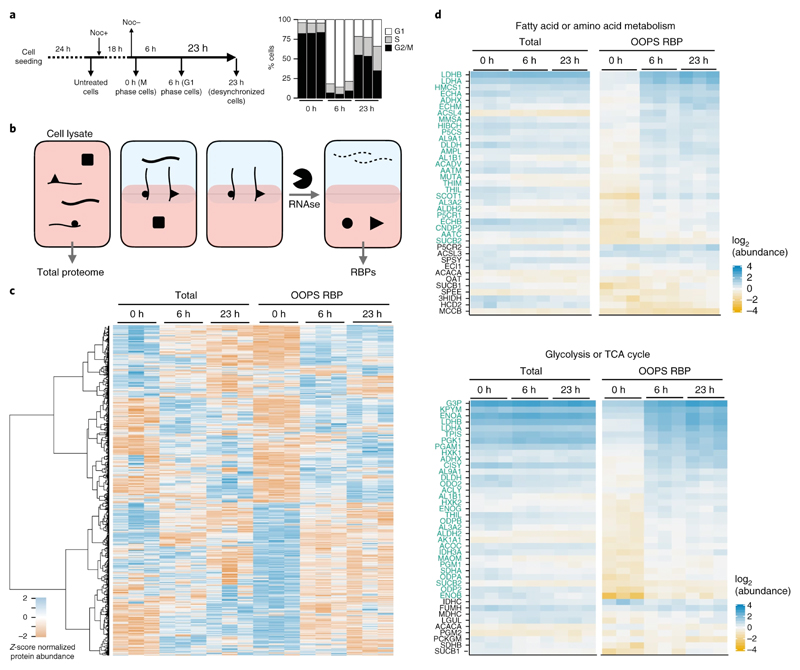

U2OS cells were arrested with nocodazole and dynamic changes in RNA-binding were determined following a short (6 h) and long recovery (23 h) using TMT quantification (Figures 5a & b, S5a and online methods). These experiments required only 0.07 m2 of cell culture, compared to the 19-27 m2 that would be required using RBP-Capture10,11. As expected, we observed increased abundance of spindle proteins at 0 h relative to 6 h, demonstrating that nocodazole arrested cells at the spindle checkpoint (Figure S5b). Quantifying protein abundance in OOPS and total cell lysates of the same sample (Figure 5b) revealed changes in RNA-binding independent from concurrent changes in total protein abundance. Interestingly, changes in OOPS-enriched protein abundance frequently did not correlate with variations in total protein abundance, suggesting that specific RBPs bind RNA differentially in different cell-cycle stages (Figure 5c, supplementary table 5).

Figure 5. RBP-ome after nocodazole arrest.

(a) Left: schematic representation of the nocodazole arrest/release experiment. Cells were analysed after 18 h nocodazole arrest and after a 6 h or 23 h release from the treatment release. Right: relative proportions of cells in G1, S and M phase for cells synchronised at each time-point (shown as the mean +/- SD of 3 independent experiments)

(b) Schematic representation of protein extraction for nocodazole-arrest experiment. Total proteomes were extracted from cell lysates and RBPs were extracted following OOPS proteome method.

(c) Protein abundance from total proteome and OOPS extractions. Abundance z-score normalised within each extraction type. Proteins hierarchically clustered across all samples as shown on left

(d) Protein abundance for groups of overlapping KEGG pathways over-represented in proteins with a significant increase in RNA-binding at 6 h vs 0 h. Individual proteins with a significant increase in RNA binding in 6 h vs 0 h are highlighted in green

To better understand protein dynamics, we used a linear model framework to identify proteins with changes in RNA-binding, taking into account their total abundance (see online methods). We focused on changes occurring between arrested cells and 6 h post-release. KEGG-pathway44 and GO term over-representation analysis identified pathways with altered RNA binding between arrest and release (Figure S5c, S6e). Open mitosis is associated with a global inhibition of RNA processing, including splicing and translation45,46. In agreement, 20/23 tRNA synthetases detected show lower RNA binding during nocodazole prometaphase arrest, suggesting a coordinated decrease in aminoacyl-tRNA availability (Figure 5Sd). Conversely, we see increased RNA binding in nocodazole arrest for components of the spliceosome (Figure S5e-f), including SRS10, which can inhibit splicing in mitosis47.

Nocodazole affects mitochondrial activity and cellular metabolism42,43,48. Indeed, we observed an over-representation of proteins involved in metabolic processes including pyruvate, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, and glycolysis in the proteins with increased RNA binding after release which was maintained at 23 h (Figure 5d, S5c, S6e). To further explore the effect of nocodazole arrest/release on metabolic enzyme RNA binding we carried out an additional experiment using a complementary approach, thymidine-nocodazole arrest (Figure S6). Comparing arrest/release cells with a non-treated population we found a similar RNA binding profile for mitochondrial and metabolic proteins between non-treated and arrested cells. The increase in the RNA binding capacity of these proteins post-release points to a gain of RBP activity after the disruptive effects of nocodazole on microtubule formation dissipate.

Many metabolic proteins have been described as eukaryotic RNA-binding proteins 12,49,50. However, this is the first demonstration, to our knowledge, of dynamic RNA-binding for these RBPs.

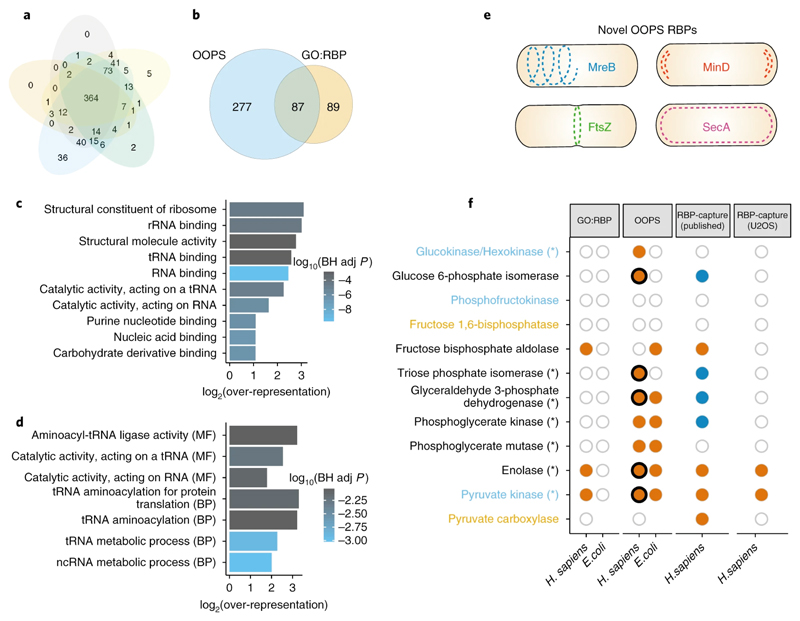

OOPS characterisation of the Escherichia coli RBPome

OOPS is not limited to polyadenylated RNA so we used it to obtain the RBPome of E. coli (online methods). We detected 364 proteins (Figure 6a) in all 5 replicates, which represents ~8% of the predicted K-12 strain proteome 51, and is s similar to the proportion obtained in eukaryotic cells. We recovered 87/176 GO annotated RBPs (Figure 6b, supplementary table 2) and observed that the over-represented GO terms for OOPS RBPs are related to RNA binding including “rRNA binding”, “tRNA binding” and the more general “nucleic acid binding” (Figure 6c). Furthermore, of the 277 novel OOPS RBPs reported here, we find a clear enrichment for RNA-associated GO-terms, mainly relating to tRNAs or ncRNAs (Figure 6d). However, 234/364 OOPS RBPs are not annotated with an RNA-related GO term, suggesting OOPS can reveal new RBP functions in prokaryotes.

Figure 6. E. coli bacterial RBPome.

(a) Overlap between RBPs identified in 5 independent OOPS replicates.

(b) Overlap between E.coli OOPS RBPs and GO annotated RBPs.

(c) Top 10 molecular function GO terms over-represented in E.coli OOPS RBPs. BH adj p-value = Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value. P-value obtained from a modified hypergeometric test to account for protein abundance (see online methods).

(d) As per (c) for all GO terms over-represented in novel E.coli OOPS RBPs.

(e) Schematic representation of OOPS novel RBPs that follow 4 distinct localisation patterns in which RNA has been found.

(f) RNA-binding capacity of glycolysis/gluconeogenesis proteins. Proteins coloured by pathways; blue text = only glycolysis, orange text = only gluconeogenesis. Asterisks = increased RNA-binding after release from nocodazole arrest. GO:RBP=GO-annotated RBP. Orange filled circle = protein observed in the dataset indicated. Dark blue fill = protein in human RBP-Capture experiments but listed as a lower-confidence “candidate” RBP. Empty circle = protein present in species but not observed in dataset. Where paralogs exist, filled circles indicate the detection of at least one paralog. Thick black line indicates an RNA-binding site was identified in the sequential digestion experiment.

Recent observations suggest that in E. coli, transcription and translation are not always linked and RNA can be sequestered in helix-like structures, or be localized to the poles or the middle of the cell, or distributed near the plasma membrane52,53. Interestingly, we found RBPs that follow these RNA localisation patterns (figure 6e), suggesting their potential implication in bacterial subcellular RNA organization.

Many of the glycolytic enzymes that bind RNA in H. sapiens, also bind RNA in E. coli (Figure 6f). Enolase 1 and Pyruvate kinase, detected in previous RBP-capture studies were identified as RBPs by OOPS in E. coli. Furthermore, GAPDH and PKG, previously described as low-confidence candidate RBPs in human by RBP-Capture, and phosphoglycerate mutase, a glycolytic protein not previously identified in any human RBP-capture, were also found as RBPs in our human and bacteria studies.

Discussion

OOPS retrieves both crosslinked RNAs representing the complete cellular transcriptome and their crosslinked RBPs. Our results agree with orthogonal data from previous RBP identification methods. Importantly, OOPS detects new RBPs from underrepresented subcellular compartments, identifies specific RNA-protein interactions, characterises dynamic systems and can interrogate bacteria.

Although OOPS recovers RNAs in an unbiased manner from both the aqueous phase and the interface post-UV crosslinking, we observe an underrepresentation of small RNAs (sRNAs) in the PBR fraction. One explanation is that tRNAs, one of the most abundant sRNA species, are less frequently protein-bound, as has been observed in bacteria54. Overall, sRNAs have a lower probability of UV crosslinking to proteins, as their shorter length results in fewer simultaneous interactions. Despite this, we consistently found sRNA-binding proteins in both human and bacteria, including canonical (Hfq) and recently discovered (ProQ) E. coli sRNA binding proteins55. Although we primarily performed RNA-Seq to demonstrate that OOPS recovers all crosslinked RNAs, we were further able to identify putative protein binding sites, including within lncRNAs. With increased read coverage at lncRNAs by depletion of mRNAs, enrichment of lncRNAs56, and/or increased overall sequencing depth, it would be possible to provide a wide-scale assessment of protein binding on lncRNAs which would help prioritise functional studies of lncRNAs.

OOPS exploits the separation of macromolecules by their physicochemical properties. As such, glycoproteins and RNA-protein adducts cannot be distinguished since glycans and RNAs are hydrophilic polymers. Our observation that the interface abundance of most glycoproteins is CL-independent and RNase insensitive suggests that they do not bind RNA. Despite this, it is interesting to note that 17/21 glycoproteins enriched by CL are localised to the exosome (a RNA-rich compartment57–59) and include 4 known RNA binding glycoproteins10,60. To completely catalog RNA-binding glycoproteins, it would be necessary to remove glycans. Achieving this in a manner that does not degrade RNA is non-trivial. We therefore took a conservative approach and discounted glycoproteins from our analyses.

Crosslinking-based detection of RBPs is based on proximity of RNAs and proteins. Currently, proteins crosslinking to RNA are referred to as RBPs, since UV crosslinking occurs at zero distance, implying binding. However, highly abundant proteins are more likely to contact RNAs at random. Therefore, characterisations of the RBPome inferred by UV crosslinking-based methods need, at a minimum, to account for the abundance of proteins in the cell, as we do here. Moreover, since some proteins may interact non-functionally with RNA, the functional relevance of some catalogs should be considered with caution19. Dynamic experiments provide one method to interrogate the biological function of RNA-protein interactions and can uncover system-wide changes in RBPs.

One of the most striking findings presented here is the coordinated increase in RNA-binding of metabolic enzymes following release from nocodazole arrest. Considering the previously described regulation of the thermal stability of glycolytic proteins in response to nocodazole arrest48, and the reported repression of translation by GAPDH in response to changes in glycolytic flux61, our results provide further evidence for a possible link between metabolism and RNA binding. Many metabolic proteins have been described as RNA-binding proteins, although this remains a controversial proposition12,49,50. Here, we confirmed that the presence of glycolysis and TCA cycle-related proteins in OOPS interfaces is CL-dependent and RNase sensitive according to our SILAC experiments (Figure S5g), supporting their capacity to interact with RNA. In particular, GAPDH has been shown to bind to a range of RNA species including tRNAs, AU-rich elements, and TERC62,63. In vitro experiments suggest binding occurs within its NAD-binding crevice, but this has not been observed in vivo36,62,64. Here, we provide the first in vivo evidence of GAPDH RNA binding in the NAD-binding crevice.

Subcellular transcriptome organization has been proposed to contribute to protein localization in eukaryotes65. In bacteria, spatial transcriptome distribution has historically been underappreciated but it now appears RNA may adopt discrete distributions52,53. close to the membrane, in a helical arrangement, close to the poles, or medial. Moreover, RNA distribution may relate to the localisation of their protein product. For example, RNA proximity to the plasma membrane has been found to be more prevalent in the transcripts that code for membrane proteins, due to their localized translation at the membrane66. Here we find that the peripheral membrane protein SecA is an RBP. Interaction between SecA, an ATPase component of the bacterial protein translocase system, and the ribosome, is thought to be mediated by a protein-protein interaction with the ribosomal L23 protein67,68. However, our data suggest that SecA may also directly interact with RNA, making it a candidate to localise RNA to the membrane. Moreover, we further determined that proteins known to follow helical, distal, and medial distributions, such as MreB69, MinD70,71 or FtsZ72, can interact with RNA, making them candidates for future targeted studies of RNA localisation.

OOPS is a highly-efficient, low-cost method for the isolation of RNA-protein complexes in any organism, enabling the analysis of both the RNA and protein components. This simple method will make RNA-protein interaction studies more accessible. We hope this will foster a systems biology view of their function by permitting the study of their dynamic properties.

Online Methods

Cell culture

U-2 OS (U2OS) and MCF 10A cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). HEK-293 were kindly provided by Dr. Johanna Rees (University of Cambridge). U2OS and HEK-293 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A and DMEM (Gibco-BRL) media respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL). MCF 10A were maintained in MEBM media (Lonza/Clonetics) supplemented with 10 ng/ml of cholera toxin (Sigma-Aldrich). All cells were maintained at 37 ºC and 5% CO2 and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination with negative results.

E. coli K-12 DH5a strain (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was cultured in LB Broth (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 ºC. All E. coli experiments were done at stationary phase after 16 h of cell growth.

Orthogonal Organic Phase Separation in human cells

Cells were cultured in 6 cm diameter dishes (28.2 cm2) for catalog experiments, or 10 cm diameter dishes (78.5 cm2) for dynamic experiments, until a maximum of 90% of confluence was reached, using a single dish per replica and condition. Cells were washed twice with PBS and supernatant removed by pipetting. In non-crosslinked controls, cells were immediately lysed by scrapping in Acidic Guanidinium-Thiocyanate-Phenol (Trizol, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the homogenate transferred to a new tube. In crosslinked samples, UV-crosslinking was performed on PBS-washed cells by UV-irradiation at 254 nm (CL-1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker; UVP). Immediately after crosslinking, cells were scraped in Trizol and the homogenized lysate was transferred to a new tube and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min to dissociate unstabilised RNA-protein interactions. For biphasic extraction, 200 μL of chloroform (Fisher Scientific) were added, phases were vortexed and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 x g at 4 °C. The upper aqueous phase (containing non-crosslinked RNAs) was transferred to a new tube, and RNA precipitated following manufacturer instructions. The lower organic phase (containing non-crosslinked proteins) was transferred to a new tube and proteins precipitated by addition of 9 volumes of methanol (Fisher Scientific). Interface (containing the Protein-RNA adducts) was subjected to extra AGPC phase separation cycles, precipitated by addition of 9 volumes of methanol, and pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 x g, RT for 10 min.

For RNA analyses, the precipitated interfaces were incubated for 2h at 50 ºC in 30 mM Tris HCl (pH8)/10 mM EDTA and 18 U of proteinase K (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were cooled and released RNA was purified by standard phenol/chloroform extraction (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer instructions.

For RNA-binding protein analyses, the precipitated interface was resuspended in 100 μL of 100 mM TEAB, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% SDS, incubated at 95 ºC for 20 min, cooled down and digested with 2 μg RNase A, T1 mix (2 mg/mL of RNase A and 5000 U/mL of RNase T1, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2-3 h at 37 ºC. Another 2 μg of RNase mix was added and incubated overnight at 37 ºC, after which a final cycle of AGPC phase partitioning was performed and released proteins recovered from the organic phase by methanol precipitation.

Orthogonal Organic Phase Separation in bacteria

E. coli cultures were grown overnight. 3 ml of culture was pelleted by centrifugation (5 min at 6000 x g, RT) and washed twice with PBS. Cells were re-suspended in PBS and crosslinked in solution at 254 nm for 525 mJ/cm2. Crosslinked cells were pelleted again and supernatant removed by pipetting, leaving approximately 50 μl of PBS. 500 μl of 0.5 mm glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each sample, mixed gently, frozen on dry ice and dried by sublimation for 2 h. Dried cells were disrupted by vortexing for 5 min, at intervals of 1 min to avoid warming the sample. 1 ml Trizol was added to each tube and samples were homogenized by vortexing. Supernatant (avoiding glass beads) was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged 5 min at 6000 x g at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, leaving the unlysed cells as a pellet. Finally, OOPS was performed as described above.

RNA quantification and integrity assessment

RNA purity was assessed by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples with a 260/280 ratio below 1.9 or 260/230 below 2 were discarded. RNA concentration was estimated using the Qubit RNA BR (Broad-Range) Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA integrity was evaluated using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent).

RNA sequencing

Protein Bound RNA (PBR) and total non-crosslinked (NC) RNA were purified using OOPS or standard Trizol extraction respectively. All RNA samples were treated with turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was depleted using RiboCop kit V1.2 (Lexogen, Greenland, NH, USA) according to manufacturer instructions, starting with 1 ug of RNA. Two nanograms of rRNA-depleted NC-RNA or 8 ng of rRNA-depleted PBR were used to generate sequencing libraries using SENSE total RNA-Seq Library Prep kit (Lexogen). All libraries were sequenced in parallel on a NextSeq 500 for 75 cycles (Illumina).

RNA-Seq data processing and bioinformatics

Quality control of raw fastqs was performed using FastQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Reads were aligned to the hg38 human genome and Ensembl 8773 using hisat274 with default settings and reads with MAPQ < 10 were discarded. Transcript quantification was performed with Salmon75 using default settings. The meta-plot of read coverage over gene model was obtained using the CGAT bam2geneprofile script with reporter=utrprofile76. For details of the identification of putative protein binding sites and the overlap with eCLIP data, see supplementary note.

Oligo(dT) RBP-capture

RBP-Capture was performed according to25, with the following modifications. We used 4 x 500 cm2 plates per condition. Oligo(dT)25 magnetic beads (NE Biolabs) were reconditioned as per manufacturer’s instructions and incubated with the lysates for a second round of RBP-capture with eluates from the two rounds were pooled together

Subcellular fractionation

U2OS cells from a single 80% confluent 500 cm2 cell culture dish (Sigma-Aldrich) were detached using trypsin without EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), pelleted 5 min at 250 x g, washed with PBS, resuspended in 50 ml of PBS and crosslinked in solution at 254 nm at 400 mJ/cm2. Cells were pelleted again for 5 min at 250 x g, resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (Roche), and lysed with a ball-bearing homogenizer (Isobiotec) on ice. Unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation at 200 x g, 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 1000 x g, 10 min at 4 ºC with the pellet collected as ‘heavy membrane fraction’. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 12.200 x g with the pellet collected as the ‘light membrane fraction’. The supernatant was collected as cytosolic fraction, frozen and dried by sublimation by SpeedVac (Labconco). Pellets from the heavy membranes, light membranes and cytosol were re-suspended in Trizol and RBPome and “total” proteome were extracted using OOPS.

Nocodazole arrest

Single nocodazole arrest

A single 10 cm2 diameter dish (per replica and condition) of U2OS cells at 70% of confluence was arrested in prometaphase by direct addition of 1 μg/ml of nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) to the cell culture media. 16-18 h post treatment, synchronised cells were washed twice in PBS and crosslinked at 254 nm at 400 mJ/cm2. Arrested cells were detached by mechanical stimulation, pelleted, solubilised in Acidic Guanidinium-Thiocyanate-Phenol and stored at -80 ºC. For the post-release 6 h and 23 h timepoints, synchronised cells were detached from the dish by mechanical stimulation, washed in PBS and re-seeded in media without nocodazole. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and crosslinked at 254 nm at 400 mJ/cm2. Cell lysates were obtained by directly scraping the crosslinked cells in Acidic Guanidinium-Thiocyanate-Phenol. The total proteome was extracted from the lysate and the RBPome was determined using OOPS (see Orthogonal Organic Phase Separation in human cells).

Double thymidine-nocodazole arrest

A single 10 cm2 diameter dish (per replica and condition) of U2OS cells at 70% of confluence was arrested in G1/S phase by incubating the cells with 2.5 mM of thymidine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 h. After the first thymidine block, cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated for 16 h with media containing 100 ng/ml of nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich). To collect our 0 h timepoint, cells were washed twice with PBS and released from nocodazole arrest for 20 min before being crosslinked at 254 nm at 400 mJ/cm2. Cells were detached by mechanical stimulation, pelleted and solubilised in Acidic Guanidium-Thiocyanate-Phenol (Trizol) and stored at –80 ºC. For post-release timepoint (6 h post-arrest), total cell lysate and OOPS preparation, cells were handled in the same conditions as for the single nocodazole arrest.

A parallel cell dish was cultured for every time point and replicate to assess the arrest efficacy and the recovery post release by flow cytometry. DNA content per cell was analysed using the Propidium Iodide Flow Cytometry Kit (Abcam) as indicated by the manufacturer. Flow cytometry results were analysed using FlowJo 8.7, manually determining the different cell populations according with their DNA content (2N = G1, 2-4N = S and 4N = G2/M).

Proteomic sample preparation

Samples were resuspended in 100 μL of 100 mM Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) (Sigma-Aldrich), reduced with 20 mM DTT (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 60 min and alkylated with 40 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature in the dark for at least 60 min. Samples were digested overnight at 37 ºC with 1 μg of Trypsin (Promega) with the exception of samples for TMT labeling which were digested overnight at 37 ºC with 1 μg Lys-C (Promega). Subsequently, 1 μg of modified trypsin (Promega) was added, and the samples were incubated for 3-4 h at 37 ºC. Samples were then acidified with TFA (0.1% (v/v) final concentration; Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged at 21,000 x g for 10 min, with the supernatant frozen at -80 ºC until required.

For peptide clean-up and quantification, 200 μL of Poros Oligo R3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) resin slurry (approximately 150-200 μL resin) was packed into Pierce™ Centrifuge Columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and equilibrated with 0.1% TFA. Samples were loaded, washed twice with 200 μL 0.1% TFA and eluted with 300 μL 70% acetonitrile (ACN) (adapted from77). 10 μL was taken from each elution for Qubit™ protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) quantitation, with the remaining sample retained for MS.

LC-MS/MS

Supplementary table 6 details the main parameters used for each sample.

SILAC labelling was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions by growing cells in DMEM media containing light (Arg0-Lys0) or heavy (Arg10-Lys8) isotopes (SILAC Protein Quantitation Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). SILAC and unlabeled samples generated from OOPS experiments in E. coli and MCF10A were acquired using CHarge Ordered Parallel Ion aNalysis (CHOPIN) acquisition in positive ion mode as previously reported78, using the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a nanoLC Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples for direct assessment of RNA crosslinking site were acquired in the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos using HCD fragmentation and detection in the orbitrap analyser.

TMT-11plex or TMT-10plex (Thermo Fisher Scientific) labelling from desalted peptides was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Equal amounts of desalted peptides were labelled immediately after being quantified with Qubit™ protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Multiplexed TMT samples were separated into 4 fractions using Pierce™ High pH Reversed-Phase Peptide Fractionation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). TMT labeled fractions were analysed in an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos. Mass spectra were acquired in positive ion mode applying data acquisition using synchronous precursor selection MS3 (SPS-MS3) acquisition mode79.

Samples from Oligo(dT) capture and from subcellular fractionation were analysed in an Orbitrap nano-ESI Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), coupled to a nanoLC (Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC).

All samples were analysed in a 120 min run except for TMT-labeled fractions (240 min) and RNA-crosslinking site assessment samples (60 min).

MS spectra processing and peptide/protein identification

Raw data were viewed in Xcalibur v.2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and data processing was performed using Proteome Discoverer v2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The Raw files were submitted to a database search using Proteome Discoverer with Mascot, SequestHF and MS Amanda80 algorithms against the Homo sapiens database for U2OS, HEK-293 and MCF 10A cells or E. coli database, downloaded in early 2017 containing human (or E. coli) protein sequences from UniProt/Swiss-Prot and UniProt/TrEMBL. Common contaminant proteins (several types of human keratins, BSA, and porcine trypsin) were added to the database, and all contaminant proteins identified were removed from the result lists prior to further analysis. The spectra identification was performed with the following parameters: MS accuracy, 10 ppm; MS/MS accuracy of 0.05 Da for spectra acquired in Orbitrap analyser and 0.5 Da for spectra acquired in Ion Trap analyser; up to two missed cleavage sites allowed; carbamidomethylation of cysteine (as well as TMT6plex tagging of lysine and peptide N-terminus for TMT labeled samples) as a fixed modification; and oxidation of methionine and deamidated asparagine and glutamine as variable modifications. Arginine (+10.008 Da) and Lysine (+8.014 Da) were also set as variable modifications in SILAC-labeled samples. Percolator node was used for false discovery rate estimation and only rank 1 peptide identifications of high confidence (FDR < 1 %) were accepted. A minimum of two high confidence peptides per protein was required for identification using Proteome Discoverer, except in samples for RNA crosslinking site assessment.

TMT reporter values were assessed through Proteome Discoverer v2.1 using Most Confident Centroid method for peak integration and integration tolerance of 20 ppm. Reporter ion intensities were adjusted to correct for the isotopic impurities of the different TMT reagents (manufacturer specifications).

Direct assessment of RNA crosslinking site in proteins

Starting from the methanol-precipitated OOPS interface, proteins were digested using 1 μg Lys-C (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in 100 μL of 100 mM TEAB (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1 μL of RNaseOUT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 37 ºC. Two different approaches were used to enriched RNA-peptides:

-

(i)

Silica-based RNA purification using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen), according with the manufacturer's instructions;

-

(ii)

Precipitation in 80% ethanol. Two rounds of precipitations were used to further clean the sample.

RNA-peptides were re-suspended in 100 μL of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)/ 2 mM MgCl2, sonicated for 15 min and incubated at 95 ºC for 20 min. 2 μg RNase A/T1 mix (2 mg/mL of RNase A and 5000 U/mL of RNase T1) was added to cooled samples, and incubated for 4 h at 37 ºC followed by a second protease digestion using 1 μg trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37 ºC. Digested samples were desalted with Oligo R3 as described in the “proteomics sample preparation” section and dried on speedvac (Labconco).

Digests were re-suspended in 30-40 μL of 80% acetonitrile (ACN)/2% TFA containing 1 μg of TiO2 beads (GL Sciences). The slurry was transferred into a p200 tip containing a C8 “plug” (3M Empore, Sigma-Aldrich) to retain the loaded TiO2 beads and the flow-through collected. The packed TiO2 was washed with 20 μL 80% ACN/2% TFA, then 20 μL 10% ACN/0.1% TFA and the flow-through from both retained. The TiO2-enriched fraction was eluted from the beads with two rounds of 20 μL of ammonia solution (1.5-1.8%), pH>10.5, and 20 μL of 50% ACN.

Proteomics bioinformatics and data analysis

Peptide-level output from Proteome Discoverer was re-processed with the add_master_protein.py script (https://github.com/TomSmithCGAT/CamProt) to ensure uniform peptide to protein assignment for all samples from a single experiment and identify peptides which are likely to originate from contaminating proteins such as keratin (see supplementary note). For quantitative experiments, peptide-level quantification was obtained by summing the quantification values for all peptides with the same sequence but different modifications. Protein-level quantification was then obtained by taking the median peptide abundance. For SILAC experiments, the ratio between treatment and control protein abundance was calculated for each sample separately and aggregated to average protein ratio. For TMT experiments, data analysis was performed using the MSnbase R package81. Log2-transformed protein abundance was centre-median normalised within each sample. For the crude fractionation experiments (n=5), the protein abundance was quantified by label-free quantification, averaged across the replicates per fraction and normalised per protein such that the sum of abundances over the 3 fractions was 1. For the U2OS RBP-Capture experiment, only proteins observed in all 3 CL replicates and no NC replicates were retained. In crosslink-testing SILAC experiments, only proteins present in at least 2 replicates were retained.

GO terms, Interpro protein domains and KEGG pathway annotations were obtained using the R package UniProt.ws82. GO terms were expanded to include all parent terms using the R package GO.db83. Glycoproteins were identified using the Uniprot84 API with categories=PTM and types=CARBOHYD. Transmembrane proteins were identified using the Uniprot API with types=TRANSMEM.

Statistics

Data handling was performed with R v3.4.1 using tidyverse packages and python v3.6.5. Plotting was performed with the ggplot2 R package85.

Proteins observed only in CL in at least one replicate were deemed enriched. For the RNAse-testing SILAC experiments, proteins only ever observed in the RNAse condition at the organic phase were deemed enriched. Vis versa, those only ever observed in the control condition at the interfaces were deemed depleted. For proteins which did not meet these criteria, all peptides observed across the replicates were treated as independent observations and a two-tailed Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon Test was used to test whether the log2 median CL:NC or RNase:Control ratio was > 0 (enriched) or < 0 (depleted), with a BH-adjusted p-values < 0.05 considered significant. Proteins with less than 6 peptides were excluded from the statistical test due to insufficient power.

GO, InterPro and KEGG over-representation analyses were conducted using the R package goseq. This package was originally developed to account for the relationship between the probability of an differentially expressed gene in RNA-seq and the length of the gene by calculating a probability weight function to estimate the relationship between gene length and P(differential expression) and then approximating a null distribution for the number of genes expected to be differentially expressed from a given set (e.g GO term) based on their length alone. An empirical p-value is then derived by comparing the number of observed genes to the null expectation. The package allows this approach to be generalised to any observation and any confounding factor. We used protein abundance since more abundant proteins are more likely to be detected and more likely to be detected as significantly altered in abundance due to relatively lower variance and thus increased statistical power. For U2OS and HEK-293, protein abundance was derived from86 taking the maximum abundance recorded across the replicates. For MCF10A, we used an in-house deep proteomics data set. For E.coli, protein abundance was obtained from PaxDB87. Proteins not present in the above reference data sets were excluded from the analysis. Resultant p-values were adjusted to account for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg88 FDR procedure. GO-terms and InterPro domains with adjusted p-value <0.01 and at least 5 proteins were considered significantly over-represented. KEGG pathways with adjusted p-value <0.05 and at least 5 proteins were considered significantly over-represented. Over-representation values given are not adjusted for protein abundance.

For the nocodazole arrest/release experiment, proteins with a change in abundance or RNA binding were identified using the lm function in R. Specifically, to identify protein with a change in abundance between nocodazole arrest and 6 h release, total protein abundance was modelled as a function of the time point alone (abundance ~ timepoint). The p-values for the timepoint coefficients for each proteins were adjusted to account for multiple hypothesis testing according to Benjamini-Hochberg88 and proteins with an adjusted p-value < 0.01 (1 % FDR) were considered to have changed abundance. To identify proteins with a change in RNA binding between nocodazole arrest and 6 h release, protein abundance in the total proteome and OOPS samples was modelled as a function of the time point, the abundance type (total or OOPS), and the interaction between these two variables (abundance ~ timepoint + type + timepoint*type). Here, the interaction term denotes whether the abundance in OOPS and total follows the same pattern across the timepoints (coefficient is zero), indicating total abundance determines the amount of protein bound to RNA, or diverges (non-zero coefficient), indicating a change in RNA binding between the timepoints. The p-values for the interaction term were obtained and adjusted as indicated above. For the heatmap representation, protein abundances were z-score normalised within the total and OOPS samples separately. Hierarchical clustering was performed with the R hclust function using 1-Spearman’s rho as the distance metric and average linkage.

For details of the identification of RNA binding sites see supplementary note.

Structural Assessment of RNA-protein contacts

In order to look for structural information to validate our direct evidence for RNA-protein contacts, the Uniprot IDs of the detected proteins were used to retrieve all their associated PDB IDs using the Uniprot Retrieve/ID mapping tool. In parallel, we retrieved information for all structures annotated as containing protein-RNA complexes in the nucleic acid database89. Comparison of PDB IDs common in both subsets revealed the structures of the ribosome quality control complex (PDB ID 3J92) and of a Glycyl-tRNA synthetase in complex with tRNA-Gly (PDB ID 4KR2). These structures, together with the structure of GADPH in complex with NAD (PDB ID 4WNC), were later visualized using VMD 1.9.490.

Supplementary Material

Editors summary.

RNA-binding proteins can be identified and quantified in any organism using a simple method that combines UV crosslinking and phase separation.

Acknowledgments

EV, TS, RQ, RH, MP, and MR, are supported by Wellcome Trust, Grant/Award numbers: 110170/Z/15/Z, 110071/Z/15/Z awarded to AEW and KSL. VD is supported by Medical Research Council, Grant/Award number: 5TR00.

MM-S is supported by a FEBS Long-Term Fellowship.

GHT and KSL are supported by IB Catalyst grant for Project DETOX (BB/N01040X/1).

We would like to thank Harriet T. Parsons for donating E. coli cells, Mohammed A. Elzek for culturing MCF10A cells, Tom Mulroney for helping culturing U2OS cells and Bettina Fisher for kindly sharing equipment.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

KSL, AEW, EV, TS and RQ conceived the study. EV, RQ, TS and KSL designed the experiments. EV optimised the initial OOPS protocol, prepared RNA-seq libraries and performed flow cytometry analysis. EV performed the SILAC, cellular subfractionation and nocodazole arrest experiments with assistance from RQ. E. coli experiments were performed by MM, EV and RQ. U2OS RBP-Capture was performed by MP, VD. EV and RQ performed all additional experiments including the RNA binding site experiment. RQ performed all mass spectrometry. TS performed all data analysis, with the exception of the analysis of uridine content (DM) and analysis of E. coli data (TS, MM) . EV, TS, RQ and KSL interpreted results, with critical appraisal of findings from AEW, MP, MR, RH and VD, including additional experiments (MP, VD and RH). GT assisted with interpretation of E. coli data. MM-S performed the protein-RNA structural analysis. TS, EV, RQ, KSL and MM-S drafted the manuscript, with revision from AEW, RH, GT, DM, MP and MR.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The Reporting Summary is available online: Life Sciences Reporting Summary

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE91 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD009668.

All sequencing data can be accessed through the European Nucleotide Archive, accession code PRJEB26736.

References

- 1.García-Mauriño SM, et al. RNA Binding Protein Regulation and Cross-Talk in the Control of AU-rich mRNA Fate. Front Mol Biosci. 2017;4:71. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller-Mcnicoll M, Neugebauer KM. How cells get the message: Dynamic assembly and function of mRNA-protein complexes. RNA Biol. 2013;14:275–287. doi: 10.1038/nrg3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engreitz JM, et al. Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature. 2016;539:452–455. doi: 10.1038/nature20149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang KC, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–126. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Ruscio A, et al. DNMT1-interacting RNAs block gene-specific DNA methylation. Nature. 2013;503:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHugh CA, et al. The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature. 2015;521:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature14443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hafner M, et al. PAR-CliP--a method to identify transcriptome-wide the binding sites of RNA binding proteins. J Vis Exp. 2010:2–6. doi: 10.3791/2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huppertz I, et al. iCLIP: protein-RNA interactions at nucleotide resolution. Methods. 2014;65:274–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castello A, et al. Insights into RNA Biology from an Atlas of Mammalian mRNA-Binding Proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baltz AG, et al. The mRNA-Bound Proteome and Its Global Occupancy Profile on Protein-Coding Transcripts. Mol Cell. 2012;46:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckmann BM, et al. The RNA-binding proteomes from yeast to man harbour conserved enigmRBPs. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sysoev VO, et al. Global changes of the RNA-bound proteome during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12128. 12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang R, Han M, Meng L, Chen X. Transcriptome-wide discovery of coding and noncoding RNA-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E3879–E3887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718406115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao X, et al. Capturing the interactome of newly transcribed RNA. Nat Methods. 2018;15 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jao CY, Salic A. Exploring RNA transcription and turnover in vivo by using click chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15779–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chomczynski P. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;159:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: Twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagenmakers AJM, Reinders RJ, Van venrooij WJ. Cross-linking of mRNA to Proteins by Irradiation of Intact Cells with Ultraviolet Light. Eur J Biochem. 1980;112:323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb07207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey RF, et al. Trans-acting translational regulatory RNA binding proteins. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9:e1465. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Nostrand EL, et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP) Nat Methods. 2016;13:508–514. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kladwang W, Hum J, Das R. Ultraviolet shadowing of RNA can cause significant chemical damage in seconds. Sci Rep. 2012;2:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep00517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinman MN, Lou H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3168–3181. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noh JH, et al. HuR and GRSF1 modulate the nuclear export and mitochondrial localization of the lncRNA RMRP. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1224–39. doi: 10.1101/gad.276022.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castello A, et al. Comprehensive Identification of RNA-Binding Domains in Human Cells. Mol Cell. 2016;63:696–710. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong S-E, et al. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–86. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thul PJ, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science (80-. ) 2017;356:eaal3321. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bose A, et al. Glucose transporter recycling in response to insulin is facilitated by myosin Myo1c. Nature. 420:821–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Münnich S, Taft MH, Manstein DJ. Crystal structure of human myosin 1c--the motor in GLUT4 exocytosis: implications for Ca2+ regulation and 14-3-3 binding. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2070–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ihnatovych I, Migocka-Patrzalek M, Dukh M, Hofmann WA. Identification and characterization of a novel myosin Ic isoform that localizes to the nucleus. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2012;69:555–65. doi: 10.1002/cm.21040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin X, et al. Cocrystal structures of glycyl-tRNA synthetase in complex with tRNA suggest multiple conformational states in glycylation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:20359–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao S, Brown A, Santhanam B, Hegde RS. Structure and Assembly Pathway of the Ribosome Quality Control Complex. Mol Cell. 2015;57:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L, Yang J, Huang Y, Liu Z-R. Phosphorylation of p68 RNA helicase regulates RNA binding by the C-terminal domain of the protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranji A, Shkriabai N, Kvaratskhelia M, Musier-Forsyth K, Boris-Lawrie K. Features of Double-stranded RNA-binding Domains of RNA Helicase A Are Necessary for Selective Recognition and Translation of Complex mRNAs * S. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White MR, et al. A dimer interface mutation in glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulates its binding to AU-rich RNA. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:1770–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.618165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh R, Green M. Sequence-specific binding of transfer RNA by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Science (80-. ) 1993;259:365–368. doi: 10.1126/science.8420004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harding SD, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1091–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buchan JR, Parker R. Eukaryotic Stress Granules: The Ins and Outs of Translation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:932–941. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulic IM, et al. The role of microtubule movement in bidirectional organelle transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:10011–10016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800031105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin C, et al. Active diffusion and microtubule-based transport oppose myosin forces to position organelles in cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11814. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Athamneh AIM, et al. Neurite elongation is highly correlated with bulk forward translocation of microtubules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7292. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C, et al. Dynamic tubulation of mitochondria drives mitochondrial network formation. Cell Res. 2015;25:1108–1120. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karbowski M, et al. Opposite effects of microtubule-stabilizing and microtubule-destabilizing drugs on biogenesis of mitochondria in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:281–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hofmann JC, Husedzinovic A, Gruss OJ. The function of spliceosome components in open mitosis. Nucleus. 1:447–59. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.6.13328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanenbaum ME, Stern-Ginossar N, Weissman JS, Vale RD. Regulation of mRNA translation during mitosis. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin C, Manley JL. The SR protein SRp38 represses splicing in M phase cells. Cell. 2002;111:407–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becher I, et al. Pervasive Protein Thermal Stability Variation during the Cell Cycle. Cell. 2018;173:1495–1507.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castello A, Hentze MW, Preiss T. Metabolic Enzymes Enjoying New Partnerships as RNA-Binding Proteins. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:746–757. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao Y, et al. The Cardiomyocyte RNA-Binding Proteome: Links to Intermediary Metabolism and Heart Disease. Cell Rep. 2016;16:1456–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anton BP, Raleigh EA. Complete Genome Sequence of NEB 5-alpha, a Derivative of Escherichia coli K-12 DH5α. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e01245–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01245-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buskila AA, Kannaiah S, Amster-Choder O. RNA localization in bacteria. RNA Biol. 2014;11:1051–60. doi: 10.4161/rna.36135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nevo-Dinur K, Govindarajan S, Amster-Choder O. Subcellular localization of RNA and proteins in prokaryotes. Trends Genet. 2012;28:314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plochowietz A, Farrell I, Smilansky Z, Cooperman BS, Kapanidis AN. In vivo single-RNA tracking shows that most tRNA diffuses freely in live bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:926–937. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smirnov A, et al. Grad-seq guides the discovery of ProQ as a major small RNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:11591–11596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609981113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mercer TR, et al. Targeted sequencing for gene discovery and quantification using RNA CaptureSeq. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:989–1009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei Z, et al. Coding and noncoding landscape of extracellular RNA released by human glioma stem cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1145. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01196-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Batagov AO, Kurochkin IV. Exosomes secreted by human cells transport largely mRNA fragments that are enriched in the 3′-untranslated regions. Biol Direct. 2013;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanada M, et al. Differential fates of biomolecules delivered to target cells via extracellular vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418401112. 201418401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watanabe A, et al. Raftlin Is Involved in the Nucleocapture Complex to Induce Poly(I:C)-mediated TLR3 Activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10702–10711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang C-H, et al. Posttranscriptional Control of T Cell Effector Function by Aerobic Glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcin ED. GAPDH as a model non-canonical AU-rich RNA binding protein. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White MR, Garcin ED. The sweet side of RNA regulation: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as a noncanonical RNA-binding protein. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2016;7:53–70. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carmona P, Rodríguez-Casado A, Molina M. Conformational structure and binding mode of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to tRNA studied by Raman and CD spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta - Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 1999;1432:222–233. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taliaferro JM, Wang ET, Burge CB. Genomic analysis of RNA localization. RNA Biol. 2014;11:1040–50. doi: 10.4161/rna.32146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moffitt JR, Pandey S, Boettiger AN, Wang S, Zhuang X. Spatial organization shapes the turnover of a bacterial transcriptome. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.13065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huber D, et al. SecA interacts with ribosomes in order to facilitate posttranslational translocation in bacteria. Mol Cell. 2011;41:343–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang S, Yang C-I, Shan S-O, et al. SecA mediates cotranslational targeting and translocation of an inner membrane protein. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:3639–3653. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201704036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Teeffelen S, et al. The bacterial actin MreB rotates, and rotation depends on cell-wall assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15822–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rowlett VW, Margolin W. The bacterial Min system. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R553–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shih Y-L, Le T, Rothfield L. Division site selection in Escherichia coli involves dynamic redistribution of Min proteins within coiled structures that extend between the two cell poles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7865–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232225100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Du S, Lutkenhaus J. Assembly and activation of the Escherichia coli divisome. Mol Microbiol. 2017;105:177–187. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zerbino DR, et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D754–D761. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]