Abstract

Background

gamification is a potentially attractive option for improving balance and reducing falls.

Objectives

to assess the effect of balance training using the NintendoTM Wii game console on balance (primary outcome), falls and fear of falling.

Design

quasi-randomised, open-label, controlled clinical trial in parallel groups, carried out on community-dwelling patients over 70 years, able to walk independently. Participants were assigned 1:1 to the intervention or control group. Balance training was conducted using the Nintendo WiiFitTM twice a week for 3 months. Balance was assessed using the Tinetti balance test (primary outcome), the unipedal stance and the Wii balance tests at baseline, 3 months and 1 year. Falls were recorded and Fear of falling was assessed by the Falls Efficacy Scale (Short-FES-I).

Results

1,016 subjects were recruited (508 in both the intervention and the control group; of whom 274 and 356 respectively completed the 3-month assessment). There was no between-group difference in the Tinetti balance test score, with a baseline mean of 14.7 (SD 1.8) in both groups, and 15.2 (1.3) at 3 months in the intervention group compared to 15.3 (1.7) in controls; the between-group difference was 0.06 (95% CI 0.30–0.41). No differences were seen in any of the other balance tests, or in incident falls. There was a reduction in the fear of falling at 3 months, but no effect at 1 year.

Conclusions

the study found no effect of balance training using the NintendoTM Wii on balance or falls in older community-dwelling patients.

The study protocol is available at clinicaltrials.gov under the code NCT02570178.

Keywords: quasi-randomized clinical trial, balance, falls, Nintendo WiiFitTM, older adults, community-dwelling

Key points

No improvements were detected on any of the balance tests at the end of training.

No fall reduction was detected after balance training using the NintendoTM Wii console in older adults.

A reduced fear of falling was found after balance training using the NintendoTM Wii console in older adults at 3 months, but no longer at 1 year. This may be a chance finding.

Introduction

Background

Falls and their consequences constitute a major health problem for older adults, due to both potential physical injuries as well as psychological trauma with fear of falling, loss of self-confidence, loss of autonomy and reduced quality of life [1]; there is a substantial financial burden associated with hospitalisation, institutionalisation and even death [2]. Over the course of a year, 30% of adults over 65 years of age fall at least once [3].

It has been suggested that balance training using home video consoles may be an effective intervention for older adults to improve balance and reduce falls [4, 5]. The NintendoTM Wii console, together with the Nintendo WiiFitTM game and Wii Balance Board, offers the possibility of following a balance training exercise programme [6–9]. This is a low-cost technology that can be used recreationally both on an individual and group basis. However there is no consensus on what exercises, doses or maintenance times should be used [10, 11], and the largest clinical trials published to date have been conducted on samples of just 40–60 people, with uncertainty about any benefits [4, 5].

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether balance training, delivered using the Nintendo WiiFitTM video console, improved balance in older adults. Secondary objectives included assessment of effect on falls and fear of falling.

Methods

Trial design

Quasi-randomized, open (non-blinded), controlled clinical trial in parallel groups (allocation ratio 1:1) that compared an intervention group, which received balance training using the Nintendo WiiFitTM, with a control group which received usual care. Potential participants were identified from the primary care lists, and recruited via telephone calls by clerical staff. A detailed description of the study protocol was published at clinicaltrials.gov under the code NCT02570178, as of 2 July 2015 [12].

The primary outcome was the Tinetti’s balance test (scored from 0 to 16 points; higher scores indicate better balance); secondary outcomes included the Tinetti gait test (0–12 points), total Tinetti score (balance plus gait; 0–28 points) [13]; the unipedal stance test (patient able to stand up on one foot without any support for 5 s [14], assessment of balance through the balance percentage calculated by the WBB in the Wii balance test from 0 to 100 points (higher scores indicate better balance) [15], fear of falling and self-efficacy regarding falls through the Falls Efficacy scale or Short-FES-I (7–28 points, lower scores indicating less fear of falling) [16], and the number of falls during the study period.

The study protocol was approved by the ANONYMIZED. All data were anonymized and the confidentiality of EHR was respected at all times, in accordance with national and international law.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients 70 years of age or older who were able to walk independently (with or without walking aids) attending one of five primary care centres.

Exclusion criteria

Home care patients, patients receiving rehabilitation treatment for gait, patients with moderate cognitive impairment (Pfeiffer’s test ≥5 [17]), patients in terminal phases of disease, patients without a telephone, patients with difficulties communicating (sensory impairment and language barriers).

Interventions

Balance training was performed by using the NintendoTM Wii console and the WBB. We used eight out of the nine exercises in the balance category of the Nintendo WiiFitTM game (balance bubble, soccer heading, ski jump, table tilt, ski slalom, penguin slide, snowboard slalom, tightrope walk) [18]. Two 30-min sessions per week during three months were carried out. Training was delivered in groups of four persons and the same exercises at the same time were performed. The groups were guided by support monitors who had received standardized training. During the training sessions, participants stood barefoot on the WBB and performed the various exercises included in the balance category of the Nintendo WiiFitTM game following the instructions displayed on the screen. Chairs were available for anyone who wanted one to guarantee their safety and catch themselves in case they lose their balance. The monitor was in charge of handling the consoles, collecting data, keeping order and managing the time so that all exercises were completed in each session. The number of repetitions of each exercise varied depending on the participants’ agility, but the total time dedicated to each exercise was the same for all participants in the group. The intervention was considered to be complete if participants attended at least 80% of the sessions. The second visit was performed after the 3-month period (up on completing the intervention) and the third visit 1 year after the beginning of the study (9 months post-intervention). Thus, the two groups participated in the study for one year. Balance tests were repeated at every visit for both groups. Participants were also asked for new falls in every visit. The intervention was performed in a nursing home and the follow-up visits in five primary Healthcare centres.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in the Tinetti balance test from baseline to the 3-month follow-up visit. Secondary outcomes included the unipedal stance test and Wii balance test, falls and fear of falling.

Sample size

We calculated that 380 patients per group were required to give 80% power at P = 0.05 (2-tailed) to detect a between-group difference of 0.5 points in the sub-scale of Tinetti’s stationary balance test (score range 0–16 points), assuming a standard deviation of 2.2. The study numbers were inflated to allow for loss of up to 20% of patients in follow-up. More detailed information regarding sample size can be found in the study protocol [12].

Randomisation

At the initial visit, having revised the inclusion/exclusion criteria and signing the informed consent, each participant was assigned an identification code. This code contained four digits: the first referred to their primary healthcare centre and the rest were sequential numbers. Participants were assigned by the care provider (nursing staff) to the intervention or control group based on whether or not their code was odd or even (odds were the intervention group and evens were the control group).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize overall data, describing demographic characteristics of the groups. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute number and percentages and continuous variables as means or medians and standard deviation (SD). To compare the differences between groups before and after intervention, Student’s T-test and McNemar’s test were used. A secondary analysis was carried out on those patients who completed the study intervention (per-protocol analysis). All statistical tests were two-sided and the level of significance was set at 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 14 for Windows (Stata Corp. LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

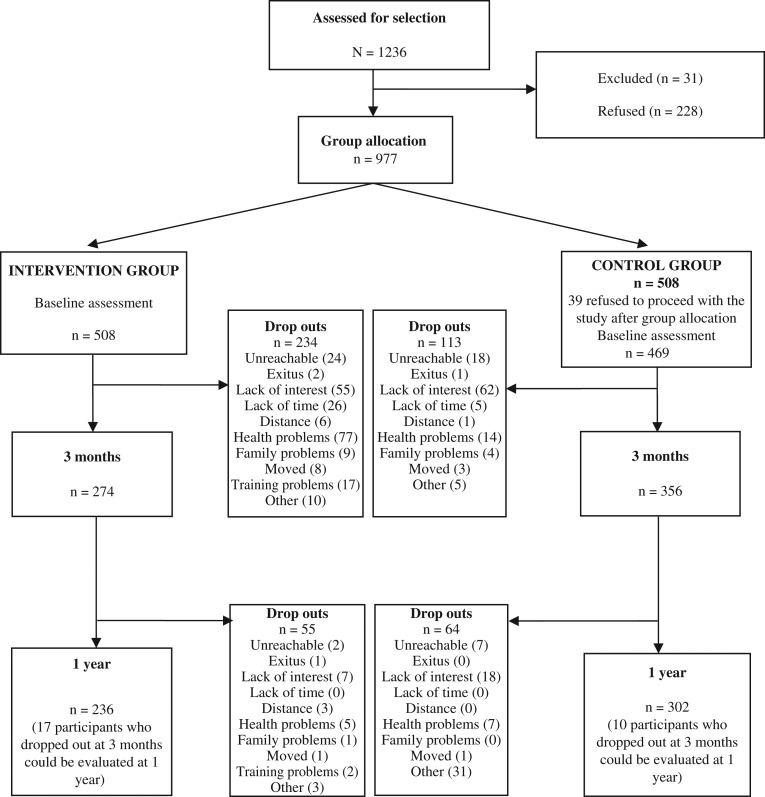

A total of 1016 participants were recruited between October 2013 and November 2016; 508 were assigned to the intervention group and 508 to the control group, of whom 469 proceeded with the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Baseline data

Five hundred and seventy-seven (59%) participants were female; the median age was 75 (73–79); 121 (13%) required technical assistance to walk and had better scores on the fear of falling assessment (median Short-FES-I = 8). A record of falls in the previous year was observed in 192 (38%) of the intervention group compared to 120 (26%) of the controls, [192 (38%) vs. 120 (26%)] (Table 1 and Appendix 1 available in Age and Ageing online).

Table 1.

Baseline data.

| Whole cohort study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Intervention Group | Control Group | |

| N = 977 | N = 508 | N = 469 | |

| Sex, n/N (%) | |||

| Male | 400/977 (40.9) | 192/508 (37.8) | 208/469 (44.3) |

| Female | 577/977 (59.1) | 316/508 (62.2) | 261/469 (55.7) |

| Age, median (p25–p75) | 75.3 (72.6–78.5) | 75.1 (72.6–78.7) | 75.4 (72.7–78.6) |

| BMI, median (p25–p75) | 27.8 (25.1–30.8) | 27.8 (25.5–30.8) | 27.5 (24.8–30.8) |

| Underweight, n/N (%) | 6/963 (0.6) | 1/499 (0.2) | 5/464 (1.1) |

| Normal weight, n/N (%) | 225/963 (23.4) | 103/499 (20.6) | 122/464 (26.3) |

| Overweight, n/N (%) | 432/963 (44.9) | 239/499 (47.9) | 193/464 (41.6) |

| Obesity, n/N (%) | 300/963 (31.1) | 156/499 (31.3) | 144/464 (31.0) |

| Cognitive impairment, n/N (%) | |||

| Without | 902/934 (96.6) | 461/475 (97.1) | 441/459 (96.1) |

| Mild | 32/934 (3.4) | 14/475 (2.9) | 18/459 (3.9) |

| IADL Scale, n/N (%) | 204/970 (21.0) | 106/503 (21.1) | 98/467 (21.0) |

| Dependent (0–7) | 766/970 (79.0) | 397/503 (78.9) | 369/467 (79.0) |

| Independent (8) | |||

| Tinetti’s test, median/N (p25–p75) | |||

| Balance | 16/963 (14–16) | 15/499 (14–16) | 16/464 (14–16) |

| Gait | 12/962 (11–12) | 12/499 (11–12) | 12/463 (12-12) |

| Total | 27/960 (26–28) | 27/497 (25–28) | 28/463 (26–28) |

| Unipedal stance test, n/N (%) | |||

| Is able | 762/962 (79.2) | 392/501 (78.2) | 370/461 (80.3) |

| Is unable | 200/962 (20.8) | 109/501 (21.8) | 91/461 (19.7) |

| Balance Wii test %, median/N (p25–p75) | 70/965 (37–87) | 70/502 (35–87) | 71/463 (39–86) |

| Patients who had fallen during past year, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 658/970 (67.8) | 312/504 (61.9) | 346/466 (74.2) |

| Yes | 312/970 (32.2) | 192/504 (38.1) | 120/466 (25.8) |

| Has received rehabilitating treatment for gait during the past year, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 907/938 (96.7) | 466/485 (96.1) | 441/453 (97.4) |

| Yes | 31/938 (3.3) | 19/485 (3.9) | 12/453 (2.6) |

| Needs technical assistance to walk, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 844/965 (87.5) | 435/502 (86.7) | 409/463 (88.3) |

| Yes | 121/965 (12.5) | 67/502 (13.3) | 54/463 (11.7) |

| Fear of falling, median/N (p25–p75) | 8/934 (7–10) | 8/475 (7–11) | 8/459 (7–10) |

Outcomes

We observed no difference between groups on any of the balance tests post-intervention (at 3-month and 1-year follow-up visits), even though the intra-group balance scores improved at 3 months and 1 year. We found a reduction fear of falling in 0.63 points (P = 0.008) at 3 months in the intervention group compared to controls that was not maintained in the 1-year follow-up visit (Table 2). The per-protocol analysis gave very similar results (see Appendix 2 available in Age and Ageing online).

Table 2.

Outcomes between groups at 3 months and 1 year. Whole cohort study.

| Intervention | Control | Differences in groups | Differences between groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Difference in % IG (95%CI)/N | Difference in % CG (95% CI)/N | Change difference % IG–CG (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Tinetti’s test, balance | ||||||

| Baseline | 14.9 (1.7)/499 | 14.8 (2.0)/464 | ||||

| 3 months | 15.2 (1.4)/293 | 15.1 (1.9)/342 | 0.28 (0.09; 0.47)/293 | 0.30 (0.10; 0.50)/342 | −0.02 (−0.30; 0.26) | 0.878 |

| 1 year | 14.9 (1.7/250) | 15.1 (1.9)/295 | 0.08(−0.16; 0.32)/250 | 0.25 (0.04; 0.46)/295 | −0.17 (−0.47; 0.14) | 0.280 |

| Tinetti’s test, gait | ||||||

| Baseline | 11.4 (1.3)/499 | 11.4 (1.8)/463 | ||||

| 3 months | 11.5 (1.3)/288 | 11.4 (1.9)/336 | 0.16 (−0.03; 0.35)/288 | 0.06 (−0.13; 0.25)/336 | 0.10 (−0.17; 0.37) | 0.466 |

| 1 year | 11.1 (2.0)/247 | 11.4 (1.9)/294 | −0.15 (−0.44; 0.14)/247 | 0.07 (−0.17; 0.32)/294 | −0.25 (−0.67; 0.17) | 0.250 |

| Tinetti’s test, total | ||||||

| Baseline | 26.2 (2.6)/497 | 26.2 (3.5)/463 | ||||

| 3 months | 26.7 (2.4)/288 | 26.5 (3.5)/333 | 0.43 (0.10; 0.76)/288 | 0.38 (0.04; 0.72)/333 | 0.05 (−0.43; 0.53) | 0.835 |

| 1 year | 26.1 (3.3)/246 | 26.4 (3.4)/294 | −0.05 (−0.50; 0.40)/246 | 0.33 (−0.07; 0.73)/294 | −0.38 (−0.98; 0.23) | 0.220 |

| Unipedal stance test, if able | ||||||

| Baseline | 231 (79.7)/501 | 276 (81.7)/461 | ||||

| 3 months | 251 (86.6)/290 | 292 (86.4)/338 | 6.90 (1.20; 12.59)/290 | 4.73 (0.54; 8.93)/338 | 2.16 (−4.36; 8.69) | 0.515 |

| 1 year | 190 (76.3)/249 | 231 (79.1)/292 | −8.03 (−7.60; 6.00)/249 | −2.05 (−6.84; 2.73)/292 | 1.25 (−6.40; 8.90) | 0.748 |

| Balance Wii test % | ||||||

| Baseline | 62.9 (29.3)/502 | 63.8 (28.4)/463 | ||||

| 3 months | 52.1 (32.3)/238 | 53.5 (30.2)/324 | −10.8 (−15.9; −5.7)/238 | −10.4 (−14.7; −6.1)/324 | −0.4 (−7.1; 6.2) | 0.895 |

| 1 year | 49.5 (31.5)/258 | 58.8 (69.1)/293 | −8.74 (−13.9; −3.59)/258 | −2.18 (−10.6; 6.22)/293 | −6.6 (−16.7; 3.6) | 0.205 |

| Fear of falling | ||||||

| Baseline | 9.5 (3.2)/475 | 9.0 (3.1)/459 | ||||

| 3 months | 8.9 (2.4)/269 | 9.0 (3.0)/339 | −0.61 (−0.89; −0.32)/269 | 0.06 (−0.19; 0.31)/339 | −0.66 (−1.05; −0.28) | 0.001 |

| 1 year | 9.3 (2.7)/177 | 8.8 (3.1)/249 | −0.60 (−1.06; −0.15)/177 | −0.42 (−0.73; −0.11)/249 | −0.18 (−0.71; 0.35) | 0.499 |

IG, intervention group; CG, control group; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

We found 92 participants who fell at 3 months [28 (12.0%) vs. 64 (17.6%)] and 126 at 1 year [47 (23.6%) vs. 79 (24.8%)].

Drop outs and harms

Three hundred and forty-seven (36%) participants dropped out of the study at 3 months, 234 (46%) in the intervention group vs. 113 (24%) of the controls. The most common reasons for dropping out were: lack of interest [117 (33.7%); 55 (23.5%) vs. 62 (54%)]; health problems [91 (26%); 77 (33%) vs. 14 (12.4%)]; lack of time [31 (9%); 26 (11%) vs. 5 (4.4%)], unreachable [42 (12%); 24 (10%) vs. 18 (16%)], problems with the training programme [17 (4.8%)]. The reasons for dropping out of study due to the training itself can be categorised in three groups: pain (n = 9), difficulty performing exercises (due to difficulties with mobility n = 4 due to a sensation of instability n = 3) and exhaustion (n = 1). (Figure 1 and Appendix 3).

Discussion

Our study showed no beneficial effect on balance or falls of 3 months of balance training using the Nintendo Wii video console. We found a reduction in fear of falling at 3 months but this was no longer present at 1 year; this is most likely to be a chance finding. To date, this is the largest clinical trial of its kind [10, 11, 19, 20]. Exercises were performed safely; no accidents were recorded during training and the monitors did not have to prevent any falls. We did not perform warm-up exercises prior to the training.

To date, group and home exercise programmes containing some balance and strength training exercises, such as Tai Chi, are known to be effective in reducing falls according to the Cochrane review [21]. For multifactorial interventions, it is not known whether their efficacy may depend on factors that have not yet been determined.

It is possible that the balance variables analysed were compromised by the ceiling effect [22], making it impossible to observe improvements. It must be considered that the study population consisted of healthy, ‘robust’ older adults who live in the community and who already presented good results on all the balance tests at the baseline visit. The percentages of falls in both groups (38% intervention group and 26% control group) are similar to other studies in this age group; in our region, the percentage of falls in patients older than 65 ranges from 14% to 46% [3].

It is worth noting that there were baseline imbalances between our two groups. The intervention group had more women and a higher percentage with previous falls. This could be a source of bias.

Limitations

Our trial had a number of limitations. First, the non-random method of group allocation using odd and even numbers is prone to bias, as the allocation of patients can be anticipated. Blinding of patients was not possible, and there was no formal blinding of outcome assessors. It is also worth noting that there were baseline imbalances between our two groups. The intervention group had more women and a higher percentage with previous falls. There was substantial attrition, both immediately after allocation and during follow-up; 39 participants in the control group refused to participate after recruitment and assignation of codes. Third, adherence to the training programme was a further problem (mostly due to health problems or lack of interest).

In conclusion, our study failed to demonstrate benefit from balance training using the Nintendo Wii video console in terms of any change in the balance tests or incident falls; the reduction in fear of falling at 3 months may be a chance finding.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Mataró Nursing Home of the Ministry of Labor, Family and Social Affairs for allowing us to carry out the training programme in their facilities. We would also like to thank all the participants for collaborating on this project.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: Nintendo lent the equipment to carry out the training programme. This equipment was be returned up on completion of the study, as stipulated in the contract.

Declaration of Sources of Funding: This project received a grant for primary care research from the Fundació Institut Universitari per a la recerca a l'Atenció Primària de Salut Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol) in 2010 (Barcelona, Spain) and a Goncal Calvo I Queralto grant from the Acadèmia de Ciències Mèdiques i de la Salut de Catalunya i Balears, Filial Maresme 2011 (Mataró, Spain). Additionally, it received funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain) in the 2012 call for Strategic Action in Health Grants, within the framework of the Spanish National Plan for Scientific Research Development and Technical Innovation 2008–11; under file code PI12/01677, and cofounded by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

References

- 1. World Health Organization WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Da Silva Gama ZA, Gómez Conesa A, Sobral Ferreira M. Epidemiología de caídas de ancianos en España. Una revisión sistemática, 2007. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2008; 82: 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rendon AA, Lohman EB, Thorpe D, Johnson EG, Medina E, Bradley B. The effect of virtual reality gaming on dynamic balance in older adults. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu AS, Gao KL, Tung AK, Tsang WW, Kwan MM. The effectiveness of exergaming training for reducting fall risk and incidence among the frail older adults with a history of falls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: 2096–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams MA, Soiza RL, Jenkinson AM, Stewart A. Exercising with Computers in Later Life (EXCELL) – pilot and feasibility study of the acceptability of the Nintendo® WiiFit in community-dwelling fallers. BMC Res Notes 2010; 3: 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clark RA, Bryant AL, Pua Y, McCrory P, Bennell K, Hunt M. Validity and reliability of the Nintendo Wii Balance Board for assessment of standing balance. Gait Posture 2010; 31: 307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park DS, Lee G. Validity and reliability of balance assessment software using the Nintendo Wii Balance board: usability and validation. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2014; 11: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leach JM, Mancini M, Peterka R, Hayes TL, Horak FB. Validating and calibrating the Nintendo Wii Balance Board to derive Reliable Center of pressure Measures. Sensors 2014; 14: 18244–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Manlapaz DG, Sole G, Jayakaran P, Chapple CM. A narrative synthesis of Nintendo Wii Fit Gaming protocol in addressing balance among healthy older adults: What system works? Games Health J 2017; 6: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shier V, Trieu E, Ganz D. Implementing exercise programs to prevent falls: systematic descriptive review. Inj Epidemiol 2016; 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montero-Alía P, Muñoz-Ortiz L, Jiménez-González M et al. . Study protocol of a randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of a primary care intervention using the NintendoTM Wii console to improve balance and decrease falls in elderly. BMC Geriatr 2016; 16: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34: 119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vellas B, Wayne SJ, Romero L, Baumgartner RN, Rubenstein LZ, Garry PJ. One-leg balance is an important predictor of injurious falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 735–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GuíasNintendo [http://www.guiasnintendo.com/2a_WII/wii_fit/wii_fit_sp/test_equilibrio.html]

- 16. Kempen GI, Yardley L, van Haastregt JC et al. . The Short FES-I: a shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age Ageing 2008; 37: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975; 23: 433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guías Nintendo [http://wiifit.com/training/balance-games.html]

- 19. Padala KP, Padala PR, Lensing SY et al. . Efficacy of Wii-Fit on static and dynamic balance in community dwelling older veterans: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Aging Res 2017; 2017: 4653635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roopchand- Martin S, Mc Lean R, Gordon C, Nelson G. Balance training with Wii Fit plus for community-dwelling persons 60 years and older. Games Health J 2015; 4: 247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; CD007146 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2010; 46: 239–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.