Abstract

Protaetia brevitarsis Lewis (P. brevitarsis) larvae, edible insect, traditionally is consumed for various health benefits. However, little information is available with respect to its direct anti-obesity effects. Thus, the present study was designed to investigate the regulatory effect of P. brevitarsis against high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obese mice. HFD-fed mice showed an increase in the body weight and serum levels of total cholesterol as well as low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and triglycerides. The administration of P. brevitarsis to obese mice induced a reduction in their body weight, lipid accumulation in liver and serum lipid parameter compared with the HFD fed mice. P. brevitarsis also inhibited the expression of obesity-related genes such as CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and fatty acid synthesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Moreover, oleic acid was identified as predominant fatty acid of P. brevitarsis by gas chromatography analysis. Conclusively, these findings suggested that P. brevitarsis may help to prevent obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases.

Keywords: Protaetia brevitarsis Lewis, Edible insect, Obesity, High-fat diet, Oleic acid

Introduction

Obesity is a serious health problem in our society and a main cause of metabolic diseases, such as hyperlipidemia, diabetes, fatty liver, atherosclerosis and cancer (Berg and Scherer, 2005; Haslam and James, 2005). Therefore, controlling obesity is an important factor for maintaining a healthy life. In recent decades, several anti-obesity drugs have been withdrawn because of various side effects (Adan et al., 2008; Kennett and Clifton, 2010). Generally, monoamine-reuptake inhibitor (Sibutramine) and lipase inhibitor (orlistat) are used for obesity therapy but use of these drugs has been limited owing to their side effects including high blood pressure, insomnia and heart attack (Buyukhatipoglu, 2008; Padwal and Majumdar, 2007; Thurairajah et al., 2005). Consequently, development of new anti-obesity drugs through natural sources has been increasing and these agents are being used not only as medicines but also as food supplements (Fu et al., 2016).

Adipogenesis is the cellular differentiation process that transforms pre-adipocytes into mature adipocytes. This process is regulated by several transcription factors including CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Additionally, lipogenic related enzymes such as fatty acid synthase (FAS) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) play important roles in lipid accumulation (Farmer, 2006; Ho et al., 2013). It was reported that increase levels of lipogenic genes enhance adipogenesis and obesity (Ranganathan et al., 2006; Yim et al., 2011).

Many species of insects are widely consumed, as they are a healthy nutritious source with protein, high fat and micronutrients (Van Huis, 2016). Additionally, insects are used in traditional medicine including anemia, inflammation, hypertension and asthma (Van Itterbeeck and Van Huis, 2012). Thus, there is an increasing interest in edible insects as an alternative source of nutrients and various bio-prospecting aspects. However, the exact pharmaceutical effect of insects as functional foods is still not well understood. Protaetia brevitarsis Lewis (P. brevitarsis) is a species of Coleoptera, and the larvae stage has been used as a traditional medicine including cancer, inflammatory disease and liver-related diseases (Kang et al., 2012; Yoo et al., 2007). Although P. brevitarsis demonstrated various biological activities, the anti-obesity effect of P. brevitarsis has not been well understood. Therefore, we were interested in determining whether P. brevitarsis has the anti-obesity activity and chose the high fet diet (HFD)-induced obese mice model as the subject for this study. This model resembles human obesity and it is used for pharmacological analysis of effective anti-obesity agents (Aoki et al., 2007; Levin et al., 1997).

To provide experimental evidence that P. brevitarsis might be a useful therapeutic drug for patients with obesity, the effects of P. brevitarsis on body weight change, serum lipid parameters and hepatic steatosis were evaluated in HFD-fed obese mice. Additionally, the constituent of fatty acid in P. brevitarsis was investigated by gas chromatograph (GC) analysis.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Protaetia brevitarsis (the 6-weeks old) were supplied by Iruda 21 Coporation (Chungdo, Republic of Korea). P. brevitarsis were freeze-dried, ground using a mill. The ground powder (50 g) was subjected to extraction with 100 mL of 70% ethanol using sonication at room temperature. The extract was filtered and concentrated using a vacuum evaporator. The extracts were freeze-dried and stored at − 70 °C. The yield of extracts was 16.2%.

1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay

The antioxidant acivity of P. brevitarsis was measured using DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) radical scavenging assay. Briefly, 1.0 mL of DPPH solution (0.1 mM) was added to each sample test tube and was shaken gently. Mixture stands for 30 min and absorbance was taken at 517 nm using spectrophotometer. The percentage of scavenging activity against DPPH radical was calculated according to the following formula:

where Aa was the absorbance of the control (blank, without sample) and Ab was the absorbance of the sample.

2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) assay

To test antioxidant activity, the ABTS (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) radical scavenging assay was performed. ABTS radical solution was generated by reacting 7 mM ABTS with 2.5 mM potassium persulfate in the dark for 20 h (absorbance = 0.700 ± 0.005). A various concentration of P. brevitarsis extracts were reacted with equal volume of the ABTS solution and the absorbance was recorded at 734 nm using the spectrophotometer (Neogen, Daejeon, Korea).

Animal experiments

Male C57BL/6J mice (4 weeks old) were obtained from the Daehan Biolink Co. (Eumsung, Korea) and housed 5–10 per cage in laminar air flow room maintained at 22 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 55 ± 10%. During acclimation, the mice were given normal chow along with water ad libitum. To induce obesity, the mice then were fed a HFD consisting of 60% fat (Rodent diet D12492; Research diet, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). Normal group were fed a commercial standard chow diet (CJ Feed Co., Seoul, Korea).The mice were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 7/group) as follows; (1) Normal diet (ND); (2) High-fat diet (HFD); (3) HFD plus P. brevitarsis (100 mg/kg/day); (4) HFD plus P. brevitarsis (200 mg/kg/day); (5) HFD plus EGCG (50 mg/kg/day), respectively for 7 weeks. P. brevitarsis and EGCG were dissolved in normal saline and administrated orally to the mice once a day. Body weight and food intake were measured once per week. All of the animal experiment and animal care was conducted with the approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Daegu Hanny University.

Serum assays

Blood samples of overnight fasted mice were collected and serum was separated by centrifugation at 4000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. The serum biochemical concentrations of total cholesterol (TG), LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TC), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were determined by the Seoul Medical Science Institute (Seoul Clinical Laboratories, Seoul, Korea).

Histological analysis

The liver tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm. For histopathological analysis, the sections were placed in xylenes and rehydrated through serial alcohol gradients (100%, 95%, 90%, 80%, 70%, and 50%, 2 min each) and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). For histological analyses of the tissue morphology, samples were examined under a light microscope (IX71; Olympus, Japan).

Cell culture and adipocyte differentiation

3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were cultured and differentiated into adipocytes in plate. Briefly, cells were cultured until confluence, as described above. Two days after confluence (day 0), cells were differentiated by inducers (0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM Dex, 1 μg/mL insulin in DMEM with 10% FBS, MDI). After 48 h (day 2), the cells were incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1 μg/mL insulin, and various concentrations of P. brevitarsis were added along with the medium. From day 4 to day 6, the medium (consisted of DMEM with 10% FBS and 1 μg/mL insulin) was changed.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 3T3-L1 cells by using a Gene AllR RiboEx Total RNA extraction kit (Gene All Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea). Total RNA was used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis performed using a Power cDNA Synthesis Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were measured with a StepOnePlus Real-time RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the relative gene expression was calculated based on the comparative CT method using StepOne Software v2.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Fatty acid methylation

The freeze-dried samples (30 g powder) of P. brevitarsis were extracted with 100 mL of 100% n-hexane at room temperature. After filtration, the n-hexane extract was evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain lipids (3.2 g).The extracted P. brevitarsis lipids were used for fatty acid analysis. The total lipids (25 mg) were mixed with 0.5 N NaOH in methanol and flushed with a stream of nitrogen gas, which was capped and votrexed. The mixtures were heated at 100 °C for 5 min. The mixtures were left at room temperature, 2 mL of the 14% boron trifluoride in methanol (BF3/MeOH) were added to each vial, which was tightly capped, the vial was carefully vortexed for 1 min, and placed in Heating/Stirring Module at 100 °C for 30 min. After derivatization, samples were allowed to cool to room temperature. Then, 5 mL of saturated NaCl solution was added to each reaction vial; the vial was vortexed for 30 s. Then, fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were extracted with 1 mL of isooctane. The isooctane layers were combined in a test tube.

Gas chromatography (GC)-FID analysis

The analysis of the fatty acid methyl esters(FAMEs) was carried out on a Shimadzu GC 2010 GC (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a SP-2560 capillary column (100 m × 0.25 mm, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). The carrier gas was N2 with a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min. Injector and detector and detector temperatures were set at 225 °C and 285 °C, respectively. The GC oven temperatures was held at 100 °C for 4 min, increased at a rate of 3 °C/min to 240 °C, and held at 240 °C for 20 min. The fatty acid compounds were identified and quantificated by comparing with the retention times and concentrations of with those of the standards under the same conditions.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of independent experiments, and statistical analyses were conducted using a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey, and a Duncan post hoc test to express the difference between groups. All statistical analyses were processed using the SPSS version 11.0. Values with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

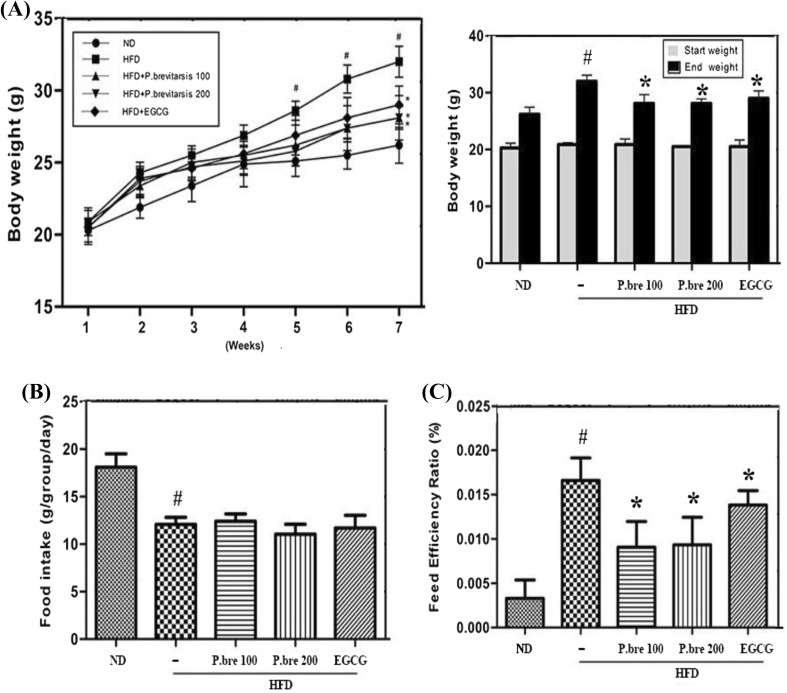

Effect of P. brevitarsis on body weight and food efficiency ratio in HFD-fed obese mice

A HFD induces a variety of metabolic disorders related to the progression of obesity and also influences the serum levels of several biochemicals such as TC, TG and LDL-C (Zhang and Yang, 2016). Therefore, the effects of P. brevitarsis on the HFD-induced body weight change were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 1(A), all groups had similar body weight at the beginning of this experiment and the final body weight in HFD-fed mice was increased compared with those in ND-fed mice, whereas P. brevitarsis (100 or 200 mg/kg) administration significantly inhibited the HFD-induced weight gain in a dose-dependent manner. In this study, EGCG was used as a positive control. These results suggested that P. brevitarsis could be an effective agent to provide an anti-obesity activity. Additionally, the effect of P. brevitarsis on food intake and the food efficiency ratio was also evaluated. Although there were no significant differences in food intake among HFD-fed mice with or without P. brevitarsis, the food efficiency ratio was significantly attenuated in P. brevitarsis group compared with the HFD group (Fig. 1B, C). This result suggested that weight loss effect of P. brevitarsis was not mediated by a reduction of food intake.

Fig. 1.

Effect of P. brevitarsis in HFD-induced obese. (A) Body weight, (B) food intake and (C) food efficiency ratio. Food efficiency ratio (%) = body weight gain/food intake × 100. Each datum represents the mean ± SD. (n = 7). (#P < 0.05, significantly different from ND group; *P < 0.05, significantly different from HFD—treated group)

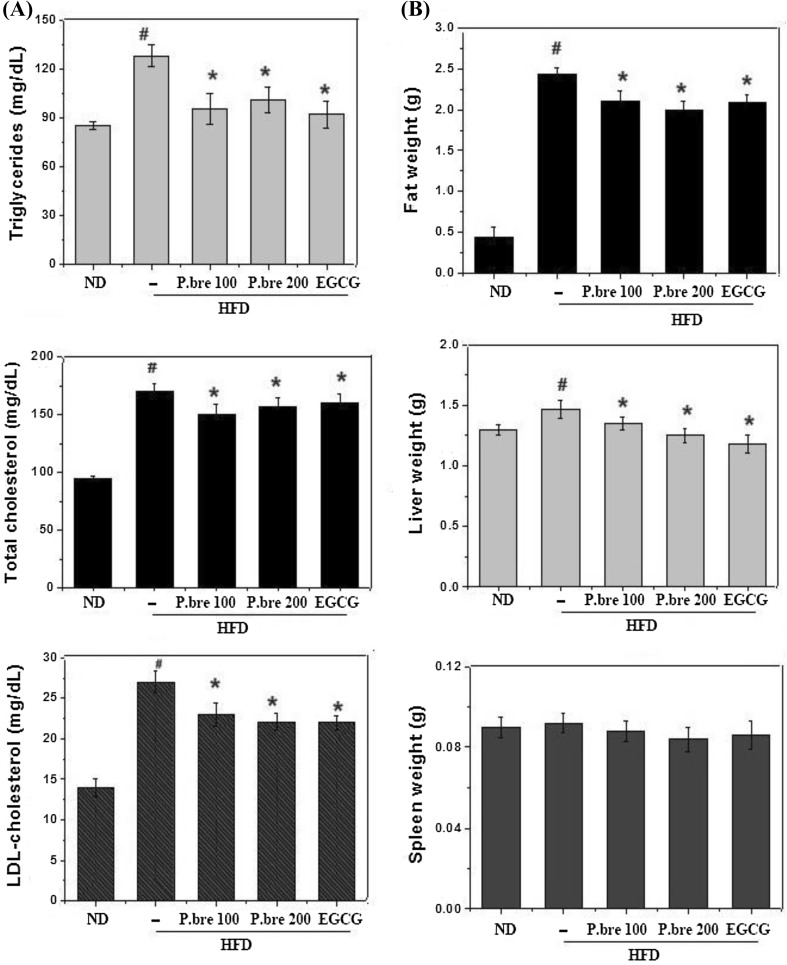

Effect of P. brevitarsis on serum levels of lipid parameters and organ weight in HFD-fed obese mice

It is well known that dyslipidemia is associated with obesity (Denke, 2001). Therefore, serum biochemical analysis was performed to determine whether P. brevitarsis regulates HFD-induced lipid parameters in the serum. As shown in Fig. 2(A), a HFD induced significant increase in TG, TC, and LDL-C, but P. brevitarsis supplementation significantly attenuated these increased TG, TC, and LDL-C levels (P < 0.05). Additionally, we investigated the effect of P. brevitarsis on organ and fat weight. The weights of the liver, epididymal, subcutaneous fat and spleen in the HFD group were higher compared with the ND group and these increased tissue weights were significantly decreased in mice fed the P. brevitarsis. However, there were no significant differences in spleen weight among HFD-fed mice with or without P. brevitarsis (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrated the potential effect of P. brevitarsis on anti-obesity activity via regulation of serum lipid levels and fat accumulation in adipose tissue.

Fig. 2.

Effect of P. brevitarsis on blood biochemistry parameters and organic tissue weights in HFD-fed obese mice. (A) Blood biochemistry parameters and (B) organic tissue weights. Each datum represents the mean ± SD. (n = 7). (#P < 0.05, significantly different from ND group; *P < 0.05, significantly different from HFD—treated group)

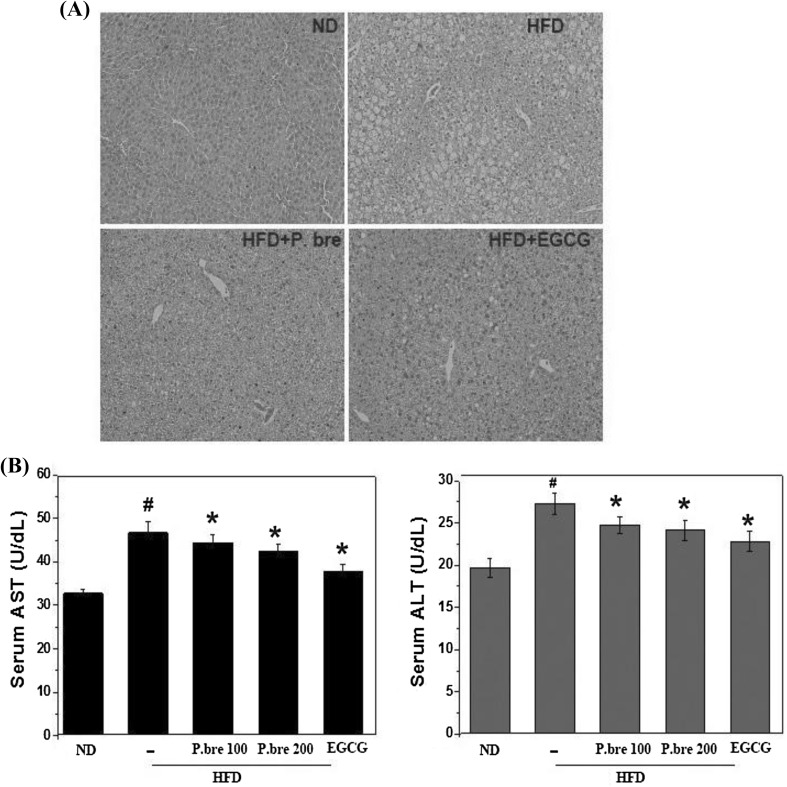

Effect of P. brevitarsis on fat accumulation in the liver in HFD-fed obese mice

Hepatic steatosis is associated with the pathogenesis of obesity (Erickson, 2009; Silverman et al., 1990). In this study, we evaluated the effect of P. brevitarsis on HFD-induced fat accumulation in liver. As depicted in Fig. 3(A), representative liver sections of the HFD group showed enlarged vacuoles, suggesting hepatic lipid deposition, compared with the ND fed mice, but this phenomenon was decreased in the P. brevitarsis group compared with the HFD group. As ALT and AST levels are commonly measured to determine liver health, the serum AST and ALT levels were also evaluated. We observed that the AST and ALT activity levels in the HFD groups was significantly increased compared with the ND groups, but was significantly decreased in the P. brevitarsis group compared with the HFD group (Fig. 3B). Consequently, these results indicated that the HFD triggered hepatic steatosis, whereas P. brevitarsis significantly suppressed this effect. This result suggested the possibility of P. brevitarsis for treatment as a valuable lipid source and providing a scientific evidence for further utilization of insects.

Fig. 3.

Effect of P. brevitarsis extracts on liver histological profiles in HFD-fed obese mice. (A) Representative photographs of liver tissue of H&E stained sections (magnification, × 200). (B) AST, ALT serum levels. (#P < 0.05, significantly different from ND group; *P < 0.05, significantly different from HFD—treated group)

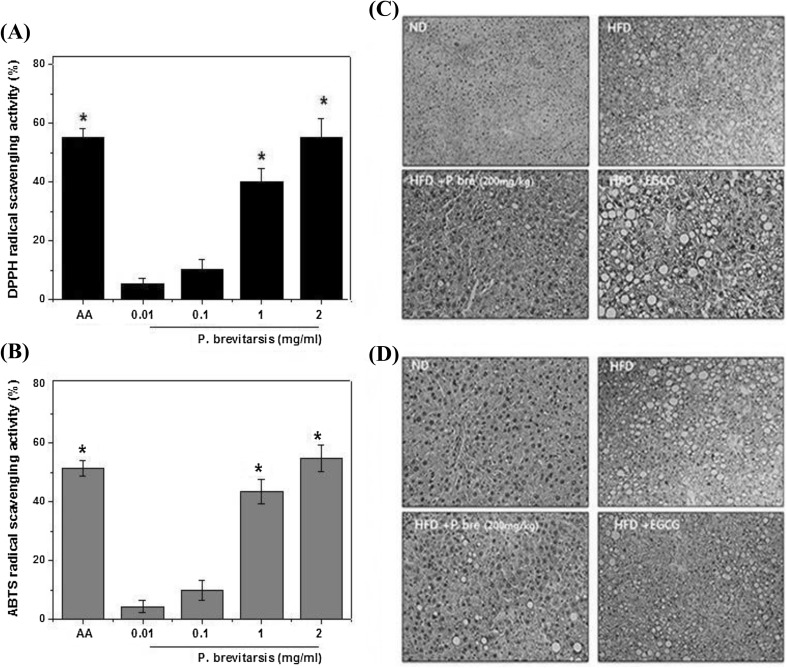

Effect of P. brevitarsis on radical scavenging activities and hepatic antioxidant enzyme in HFD-fed obese mice

It was reported that obesity is responsible for the generation of systemic oxidative stress, and produces reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, the activity of antioxidant enzymes was found to be diminished in obesity (Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2011; Newsholme et al., 2016). These results indicated that oxidative stress may be target for prevention of obesity. To investigate the antioxidant effect of P. brevitarsis, DPPH radical scavenging test was conducted. The DPPH scavenging activities of P. brevitarsis were measured at various concentrations (0.01–2.00 mg/mL). The results showed that the scavenging activities were increased significantly with the increased concentrations of P. brevitarsis: the scavenging activities of the P. brevitarsis were determined to be 55.3%, 40.2%, 10.2% and 5.2% for 0.01, 0.10, 1.00 and 2.00 mg/mL, respectively (Fig. 4A). Ascorbic acid (AA) was used as a positive control. The ABTS assay also was used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of P. brevitarsis. The ABTS radical scavenging effects of the P. brevitarsis were found to be 4.13%, 9.8%, 43.5% and 54.8% for 0.01, 0.10, 1.00 and 2.00 mg/mL, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results showed that P. brevitarsis could be an anti-oxidant rich source for human consumption.

Fig. 4.

Effect of P. brevitarsis extracts on radical scavenging activity and hepatic antioxidant status in liver of HFD-fed obese mice. (A) Various concentrations of P. brevitarsiswas incubated with DPPH at 25 °C for 20 min and absorbance measured was at 517 nm. (B) ABTS cation radical scavenging activity of P. brevitarsis Lewis was evaluated. Sections of liver of HFD-treated mice with or without P. brevitarsis treatment were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. The liver were removed and embedded in paraffin, and then 5 m sections were prepared and stained with anti- catalase (C) and anti- glutathione peroxidase (D). All tests were carried out in triplicate. Each datum represents the mean ± SD. (#P < 0.05, significantly different from control group)

Elevated level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is associated with obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases. Especially, oxidative stress associated with consumption of HFD results from overwhelmed antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (CAT). Numerous reports have demonstrated that antioxidants may be a regulator of obesity (Bharathi et al., 2018; Gentile et al., 2018). In our current study, we investigated the effect of P. brevitarsis the antioxidant enzymes status in the liver of HFD-fed mice. As shown in Fig. 4(C, D), the hepatic content of CAT and GPx in the liver of HFD-fed mice decreased when compared to ND group and this decrease was significantly reversed by administration of P. brevitarsis. These results of present study indicated that P. brevitarsis could be a strong therapeutic alternative for the prevention and treatment of HFD-induced oxidative stress.

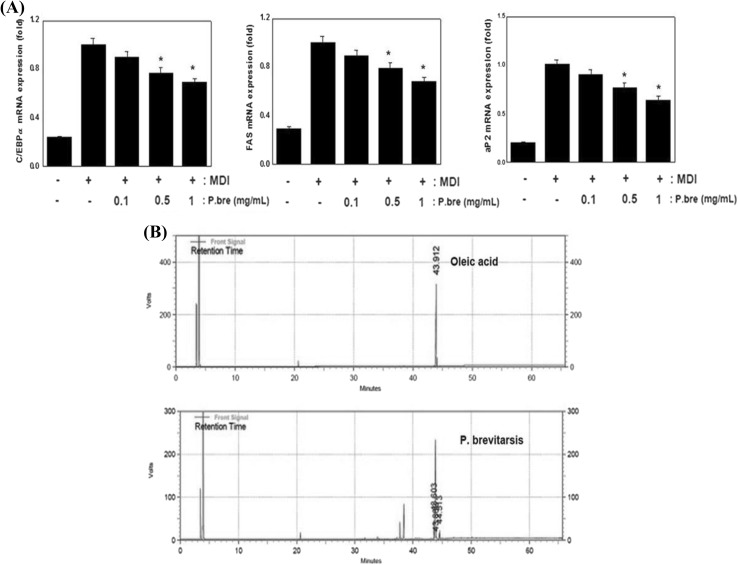

Effect of P. brevitarsis on adipogenesis-related genes expression and qualitative analysis of P. brevitarsis by GC analysis

The 3T3-L1 murine pre-adipocyte cell line has been commonly used as an in vitro model system to investigate the molecular mechanism of adipogenesis. It was reported that materials with anti-obesity activity suppressed the adipocyte differentiation through the regulation of specific genes including PPARγ, C/EBPα, aP2, and FAS in 3T3-L1 cells (Denke, 2001). Recently, the anti-obesity activity and mechanism of edible insects have been investigated. For example, Allomyrinal dichotoma larvae reduce food intake and body weight via the regulation of adipogenesis-related genes (Chung et al., 2006). Tenebrio molitor Larvae inhibit adipogenesis through the suppression of PPARγ and C/EBPα expression in 3T3-L1 cell (Seo et al., 2017). In this study, we investigated whether P. brevitarsis can inhibit adipocyte differentiation through the suppression of related transcription factors. As a result, P. brevitarsis treatment resulted in reduced expression of C/EBPα mRNA levels in 3T3-L1 cells. We also observed that 3T3-L1 cells treated with P. brevitarsis showed a decreased mRNA expression of several adipogenesis-related genes including aP2 and FAS (Fig. 5A). These results demonstrated that the anti-obesity activity of P. brevitarsis is attributable to the regulation of adipogenesis-related genes expression.

Fig. 5.

Effect of P. brevitarsis extracts on adipogenesis-related genes expression in 3T3-L1 cells and gas chromatogram in fatty acid of P. brevitarsis. (A) 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated in the absence or presence of P. brevitarsis for 6 days. C/EBPα, FAS and aP2 mRNA expression were evaluated by the quantitative real-time PCR. GAPDH was used as internal controls. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. Where P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference from the differentiated control. (B) The retention time of oleic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and fatty acid of P. brevitarsis was specified for the comparison

Previous other study reported that P. brevitarsis larvae contained the crude protein (54.25%), crude fat (26.70%), carbohydrate (10.61%), crude ash (4.45%) and moisture (3.99%) (Yeo et al., 2013). To elucidate the fatty acid profile of P. brevitarsis, GC analysis was conducted. The fatty acid content for P. brevitarsis was presented in Table 1. The results showed that the 14 fatty acids from P. brevitarsis were identified and characteristic of fatty acid composition was the high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (82.4% of total fatty acids) versus saturated fatty acids (17.6% of total fatty acids). Oleic acid was reported to be the primary fatty acid in various edible insects (Yang et al., 2014). In present study, we confirmed the predominant fatty acid was oleic acid (C18:1, 62.7% of total fatty acids). It was reported that the high oleic acid diet has anti-obesity activity via increase of oxidation and energy expenditure (Kien and Bunn, 2008; Liu et al., 2016). Figure 5(B) shows the detection of oleic acid in fatty acid of P. brevitarsis by GC. Therefore, oleic acid of P. brevitarsis may be beneficial agent for treating and preventing obesity.

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition of P. brevitarsis

| No. | Components | Fatty acid | Retention time (min) | Content (% of total fatty acids) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myristic acid | C14:0 | 36.87 | 0.4 |

| 2 | Myristoleic acid | C14:1 | 37.96 | 0.9 |

| 3 | Pentadecenoic acid | C15:1 | 40.34 | 0.7 |

| 4 | Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 41.33 | 14.4 |

| 5 | Palmitoleic acid | C16:1 | 42.99 | 7.5 |

| 6 | Heptadecanoic acid | C17:0 | 43.84 | 0.1 |

| 7 | cis-10-heptadecanoic acid | C17:1 | 45.04 | 0.3 |

| 8 | Stearic acid | C18:0 | 45.82 | 2.1 |

| 9 | Oleic acid | C18:1 | 47.11 | 62.7 |

| 10 | Linoleic acid | C18:2 | 49.11 | 10.0 |

| 11 | Arachidic acid | C20:0 | 49.91 | 0.4 |

| 12 | cis-11-Eicosenoic acid | C20:1 | 51.19 | 0.1 |

| 13 | Linolenic acid | C18:3 | 51.54 | 0.2 |

| 14 | Tricosanoic acid | C23:0 | 55.85 | 0.2 |

In conclusion, this study suggested that P. brevitarsis can regulate the obesity in vivo including body weight gain, serum lipid levels, epididymal and peritoneal fat, and hepatic steatosis induced by a HFD. Additionally, we demonstrated that the anti-obesity activity of P. brevitarsis could be attributed, at least in part, to the inhibition of obesity-related gene expression. These results provide experimental evidence showing that P. brevitarsis might have potential as a new strategy to treat obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by “Food Functionality Evaluation program” under the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs and partly Korea Food Research Institute.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eun-Mi Ahn, Email: AhnEM@dhu.ac.kr.

Noh-Yil Myung, Email: myungnohyil@wdu.ac.kr.

Hyeon-A Jung, Email: jungha@dhu.ac.kr.

Su-Jin Kim, Phone: +82-53-819-1389, Email: ksj1009@dhu.ac.kr.

References

- Adan RAH, Vanderschuren LJ, la Fleur SE. Anti-obesity drugs and neural circuits of feeding. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29:208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki F, Honda S, Kishida H, Kitano M, Arai N, Tanaka H, Yokota S, Nakagawa K, Asakura T, Nakai Y, Mae T. Suppression by licorice flavonoids of abdominal fat accumulation and body weight gain in high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:206–214. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2005;96:939–949. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharathi V, Rengarajan RL, Radhakrishnan R, Hashem A, Abd Allah EF, Alqarawi AA, Anand AV. Effects of a medicinal plant Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.formulation (MUF) on obesity-associated oxidative stress-induced liver injury. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018;25:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyukhatipoglu H. A possibly overlooked side effect of orlistat: gastroesophageal reflux disease. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2008;100:1207. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MY, Yoon YI, Hwang JS, Goo TW, Yoon EY. Anti-obesity effect of Allomyrina dichotoma (Arthropoda: Insects) larvae ethanol extract on 27. 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Entomol. Res. 2014;44:9–16. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denke MA. Connections between obesity and dyslipidaemia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2001;12:625–628. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SK. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:412–416. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800089-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Sánchez A, Madrigal-Santillán E, Bautista M, Esquivel-Soto J, Morales-González Á, Esquivel-Chirino C, Durante-Montiel I, Sánchez-Rivera G, Valadez-Vega C, Morales-González JA. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:3117–3132. doi: 10.3390/ijms12053117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Jiang Y, Guo J, Su Z. Natural products with anti-obesity effects and different mechanisms of action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;28:9571–9585. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile D, Fornai M, Pellegrini C, Colucci R, Blandizzi C, Antonioli L. Dietary flavonoids as a potential intervention to improve redox balance in obesity and related co-morbidities. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018;6:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0954422418000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JN, Son ME, Lim WC, Lim ST, Cho HY. Germinated brown rice extract inhibits adipogenesis through the down-regulation of adipogenic genes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013;68:274–278. doi: 10.1007/s11130-013-0366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Kang C, Lee H, Kim E, Kim J, Kwon O, Lee H, Kang H, Kim C, Jang H. Effects of fermented aloe vera mixed diet on larval growth of Protaetia brevitarsis seulensis (Kolbe) (Coleopteran: Cetoniidae) and protective effects of its extract against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in Sprague-Dawley rats. Entomol. Res. 2012;42:111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5967.2012.00444.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Clifton PG. New approaches to the pharmacological treatment of obesity: can they break through the efficacy barrier? Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2010;97:63–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kien CL, Bunn JY. Gender alters the effects of palmitate and oleate on fat oxidation and energy expenditure. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:29–33. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balkan B, Keesey RE. Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague dawley rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:725–730. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kris-Etherton PM, West SG, Lamarche B, Jenkins DJ, Fleming JA, McCrea CE, Pu S, Couture P, Connelly PW, Jones PJ. Effects of canola and high-oleic-acid canola oils on abdominal fat mass in individuals with central obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:2261–2268. doi: 10.1002/oby.21584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Cruzat VF, Keane KN, Carlessi R, de Bittencourt PI., Jr Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochem. J. 2016;15:4527–4550. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160503C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwal RS, Majumdar SR. Drug treatments for obesity: orlistat, sibutramine, and rimonabant. Lancet. 2007;6:71–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan G, Unal R, Pokrovskaya I, Yao-Borengasser A, Phanavanh B, Lecka-Czernik B, Rasouli N, Kern PA. The lipogenic enzymes DGAT1, FAS, and LPL in adipose tissue: effects of obesity, insulin resistance, and TZD treatment. J. Lipid. Res. 2006;47:2444–2450. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600248-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M, Goo TW, Chung MY, Baek M, Hwang JS, Kim MA, Yun EY. Tenebrio molitor larvae inhibit adipogenesis through AMPK and MAPKs signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and obesity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:518. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JF, O’Brien KF, Long S, Leggett N, Khazanie PG, Pories WJ, Norris HT, Caro JF. Liver pathology in morbidly obese patients with and without diabetes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1349–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurairajah PH, Syn WK, Neil DA, Stell D, Haydon G. Orlistat (xenical) induced subacute liver failure. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;17:1437–1438. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000187680.53389.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Huis A. Edible insects are the future? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016;75:294–305. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itterbeeck J, van Huis A. Environmental manipulation for edible insect procurement: a historical perspective. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Liu S, Sun J, Yu L, Zhang C, Bi J, Yang Z. Nutritional composition and protein quality of the edible beetle Holotrichia parallela. J. Insect. Sci. 2014;14:139. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo H, Youn K, Kim M, Yun EY, Hwang JS, Jeong WS, Jun M. Fatty acid composition and volatile constituents of Protaetia brevitarsis larvae. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013;18:150–156. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2013.18.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim MJ, Hosokawa M, Mizushina Y, Yoshida H, Saito Y, Miyashita K. Suppressive effects of Amarouciaxanthin A on 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation through down-regulation of PPARγ and C/EBPα mRNA expression. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011;59:1646–1652. doi: 10.1021/jf103290f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo YC, Shin BH, Hong JH, Lee J, Chee HY, Song KS, Lee KB. Isolation of fatty acids with anticancer activity from Protaetia brevitarsis larva. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2007;30:361–365. doi: 10.1007/BF02977619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yang XJ. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8905–8909. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]