Abstract

Objectives

To review the notification rate and characteristics of tertiary and neurosyphilis cases in Alberta, Canada in the postantibiotic era.

Methods

A retrospective review of all neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis cases reported in Alberta from 1973 to March 2017 was undertaken and cases classified into early neurosyphilis, late neurosyphilis and cardiovascular (CV) syphilis. Variables collected included demographics, sexual partners, HIV status, clinical parameters, symptoms and treatment and distributions were compared between early versus late neurosyphilis and asymptomatic versus symptomatic cases (stratified by early versus late stage). Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.19.0.

Results

254 cases were identified; 251 were neurosyphilis and 3 were CV. No cases of gummatous syphilis were reported. Early neurosyphilis accounted for 52.4% (n=133) and 46.1% (n=117) were late neurosyphilis cases; one (0.4%) case with unknown duration. Three outbreaks of infectious syphilis were identified during the study period and a concurrent rise in both early and late neurosyphilis was observed during the outbreak periods. The most common manifestation of symptomatic neurosyphilis was ocular involvement which was more likely in early neurosyphilis. Relative to late neurosyphilis cases, early neurosyphilis cases were more likely to be younger, Caucasian, born in Canada, HIV positive and reporting same sex partners.

Conclusions

Our review of tertiary and neurosyphilis cases found that early and late neurosyphilis cases continue to occur in the context of cycling syphilis outbreaks. CV syphilis cases were extremely rare. Ongoing identification of new cases of syphilis and clinical evaluation of cases for complications continues to be important in the context of global resurgence of syphilis.

Keywords: tertiary syphilis, neurosyphilis, Canada

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An important strength of our study was the consistent reporting of all cases with positive syphilis serology over the 44-year period by laboratories as well as active follow-up of all cases by the provincial STI programme.

Another strength of our study is the retrospective application of current case definitions to all cases by two experienced STI clinicians.

One of the limitations to the retrospective review of data is the possibility of inaccurate classification of cases due to insufficient available information.

Additional study limitations include changes in testing policies over time.

Routine testing for HIV in cases of syphilis was also not conducted in earlier years and as such the number of concurrent HIV infections may have been underestimated.

Background

Syphilis, caused by Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum, passes through a series of stages, including primary, secondary, latent and tertiary syphilis if left untreated.1 Based on data from the preantibiotic era, about a third of persons with untreated latent syphilis will develop late neurosyphilis, cardiovascular (CV) syphilis or gummatous syphilis.2 Gummatous syphilis is characterised by the development of indolent granulomatous lesions3 which typically affect the skin, liver and bone but can also involve other parts of the body.4 Syphilitic aortitis is the most common manifestation of CV syphilis and typically involves the ascending aorta.4–6

Neurosyphilis can occur at any stage of syphilis.1 7 It is classified into early and late forms.1 Early neurosyphilis affects the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), cerebral blood vessels and meninges more often than the brain or spinal cord parenchyma. Typically, manifestations occur within weeks to a few years after primary infection and may occur at the same time as primary or secondary syphilis or may be asymptomatic. Manifestations may include meningitis with or without cranial nerve involvement, meningovascular disease or stroke. Late neurosyphilis can remain asymptomatic or progress to meningovascular syphilis, tabes dorsalis or general paresis. Late neurosyphilis is extremely rare in the antibiotic era and usually occurs years to decades after primary infection.1 8 HIV infection may affect the natural course of disease as atypical presentations and rapid progression of syphilis in HIV positive individuals has been reported.9–13

In the preantibiotic era, an estimated one third of untreated persons developed tertiary syphilis with about 15% progressing to gummatous disease (1–46 years postinfection), 10% to CV syphilis (20–30 years after infection) and 4%–14% to late neurosyphilis (2–50 years after infection).1 After the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, the number of cases of syphilis plummeted in the USA, reaching a nadir in 2000.1 Nowadays, tertiary syphilis is a rare disease due to easy and effective treatment of infectious and latent syphilis. Antibiotic use for other infections is also likely a factor.

In Canada, syphilis (all stages) has been nationally notifiable since 1924. However, national reports only include data on infectious syphilis, since only these cases are of major public health significance.14 In Alberta, all cases of syphilis, including tertiary and neurosyphilis have been notifiable to a centralised programme under the Public Health Act since 1921. Syphilis notification rates have fluctuated over the last 50 years with a rise in notification rates during outbreak periods. Since 2000, notification rates of infectious syphilis have increased dramatically in Alberta (0.6/100 000 population in 2000 to 12.5/100 000 population in 2017), with the most recent resurgence among men who have sex with men (MSM) and up to 30% of patients coinfected with HIV (personal communication Jennifer Gratrix, Provincial STI Services, Alberta Health Services).15

There are few data on the prevalence and characteristics of tertiary and neurosyphilis cases in the post antibiotic era. We are aware of only one study from the Netherlands which estimated that 10%–13% of all syphilis cases from 1999 to 2010 had neurosyphilis; these data were limited by the fact that the diagnostic criteria used for neurosyphilis were based on hospital discharge diagnosis rather than clinical examination or laboratory criteria.16 We sought to determine the notification rate and characteristics of reported cases of tertiary and neurosyphilis in Alberta from 1973 onwards.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of all tertiary and neurosyphilis cases in Alberta (current population 4.3 million) from 1973 (when syphilis data were first available by staging) to March 2017 (most recent cases staged at time of data collection). All cases of syphilis are reportable by laboratories and clinicians to Provincial STI Services under the Alberta Public Health Act. A paper chart was created for each syphilis case containing laboratory results, medical correspondence, syphilis-relevant history, clinical findings and staging. Cases diagnosed since 2000 were also entered into a provincial surveillance database. Cases were classified as defined in table 1.17

Table 1.

Case definitions used for diagnosis of neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis (Adapted from Ref. 17)

| Syphilis stage | Definition |

| Tertiary syphilis | Reactive treponemal serology together with characteristic late abnormalities of the cardiovascular system, bone, skin or other structures, in the absence of other known causes of these abnormalities and no clinical or laboratory evidence of neurosyphilis |

| Early neurosyphilis (<1 year after infection) Asymptomatic |

Laboratory confirmation of primary, second or early latent syphilis and (i) reactive CSF-VDRL in non-bloody CSF AND/OR (ii) elevated CSF leucocytes (>5/10E6/L) and/or elevated CSF protein (>0.45 g/L) in the absence of other known causes AND NO signs or symptoms of neurosyphilis |

| Early neurosyphilis (<1 year after infection) Symptomatic |

Laboratory confirmation of primary, second or early latent syphilis and (i) reactive CSF-VDRL in non-bloody CSF AND/OR (ii) elevated CSF leucocytes (>5/10E6/L) and/or elevated CSF protein (>0.45 g/L) in the absence of other known causes AND clinical signs or symptoms of neurosyphilis* |

| Late neurosyphilis (>1 year after infection) Asymptomatic |

Reactive treponemal serology (not staged as primary, secondary or early latent syphilis) and (i) reactive CSF-VDRL in non-bloody CSF AND/OR (ii) elevated CSF leucocytes (>5/10E6/L) and/or elevated CSF protein (>0.45 g/L) in the absence of other known causes AND NO clinical signs or symptoms of neurosyphilis |

| Late neurosyphilis (>1 year after infection) Symptomatic |

Reactive treponemal serology (not staged as primary, secondary or early latent syphilis) and (iii) reactive CSF-VDRL in non-bloody CSF AND/OR (iv) elevated CSF leucocytes (>5/10E6/L) and/or elevated CSF protein (>0.45 g/L) in the absence of other known causes AND clinical signs or symptoms of neurosyphilis* |

*If ocular or otic signs or symptoms present with a normal CSF examination, patient was classified as symptomatic neurosyphilis (early or late).

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LLS, late latent syphilis; STI, sexually transmitted infection; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Serological testing for syphilis changed during the study period, with reverse sequence syphilis screening (RSSS) using an enzyme immunoassay being introduced in September 2007; prior to this, a quantitative rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was used. Since the criteria for classifying neurosyphilis evolved over time, all neurosyphilis cases during the study period were reviewed by two STI physicians and classified into early asymptomatic, early symptomatic, late asymptomatic, late symptomatic neurosyphilis cases; disagreement between the classifications of cases was resolved by consensus between the two physicians (PS and AES).

Reported notification rates of other stages of syphilis prior to 2000 were obtained from historical surveillance reports from Alberta STI Services beginning in 1975. Population denominators were obtained through government population estimates.18 An outbreak was defined as an increase in infectious syphilis cases of two SD above the baseline (previous 5 year quarterly average) for the given time period.

Variables collected for analysis included demographics, sexual partners, HIV status (testing available since 198519 and recommended for all syphilis cases once serology available), diagnosis date, clinical parameters, symptoms and treatment. Variables for cases diagnosed prior to 2004 were captured through chart review, while variables for cases diagnosed after 2004 were extracted from the provincial STI surveillance system. Client reported symptoms were broken into five categories (not mutually exclusive) based on system involvement: ocular (eg, uveitis, retinal, vision loss), auditory (eg, hearing loss, tinnitus), ataxia, cognitive impairment (eg, dementia, psychosis) and other (aphasia, stroke, reduced level of consciousness, headache and unspecified neurological symptoms).

Treatment data were divided into three mutually exclusive categories based on the following minimum treatments: (1) penicillin G 3–4 million units intravenous q 4 hour (18–24 million units/day) for 10–14 days, (2) ceftriaxone 2 g intravenous/IM daily × 10–14 days, (3) other, which included drugs like chloramphenicol, doxycycline, tetracycline, benzathine penicillin G-long acting, reduced doses of penicillin G or ceftriaxone.

Analysis was stratified by stage of syphilis to compare early and late neurosyphilis by the previously listed variables using χ² or Fisher’s exact for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables. Missing data were categorised as unknown and included in the analysis. As well, each syphilis stage was stratified by asymptomatic and symptomatic for comparison. The significance was set at a two-sided p<0.05. A sensitivity analysis to verify univariate findings by cases diagnosed pre-2000 and post-2000 was considered; however, small cell sizes precluded the inclusion of early neurosyphilis and changes to syphilis screening in 2007 increasing the diagnosis of late latent syphilis cases were already known. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). This study was approved by the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (Approval Number: Pro00075972).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design of this research study.

Results

A total of 254 cases were identified during the study period, of which 251 were neurosyphilis and 3 were CV cases; one case of CV syphilis was reported in each of the following years: 1976, 1979 and 1984. No cases of gummatous syphilis were reported during this time period. The neurosyphilis cases were evenly divided as early (52.4%; n=133) and late (46.1%; n=117), with one additional case of unknown duration. Three individuals were diagnosed with two distinct episodes of neurosyphilis over the course of the reporting period. All three of these individuals were men who reported same sex partners, all six episodes were diagnosed between 2005 and 2014 and all categorised as early neurosyphilis. Two of these men were coinfected with HIV.

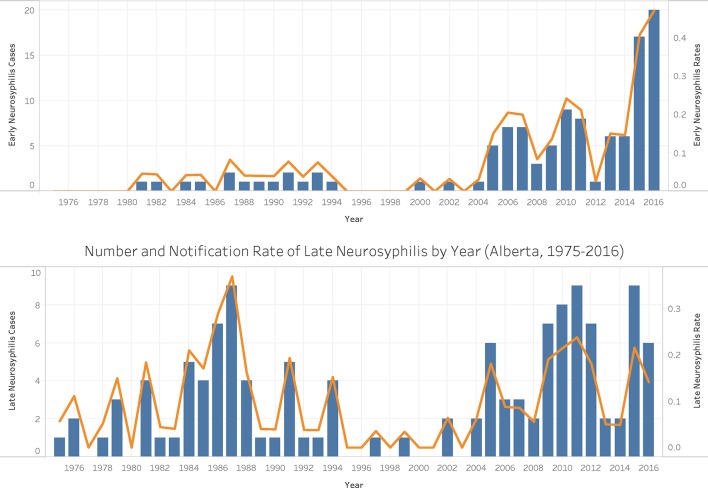

Between 1975 and 2016, 8874 total cases of syphilis were reported in Alberta. Of these, 4513 (51%) were infectious (ie, staged as primary, secondary, early latent) and 4361 (49%) were classified as non-infectious (ie, late latent, tertiary). Over the time period, three outbreaks of infectious syphilis were identified (figure 1). The first outbreak occurred between 1981 and 1987, the second outbreak started in 2000 and declined in 2011 and a third outbreak began in 2015 and continues. Of the infectious syphilis cases, 2.8% (n=128) were staged as early neurosyphilis. When plotting the notification rate of early neurosyphilis cases, increases in the rate were found at corresponding times to infectious syphilis outbreaks #2 and #3 (figure 2). Of the non-infectious syphilis cases staged during this time, 2.6% (115/4316) were staged with late neurosyphilis. Similarly, for late neurosyphilis, peaks in notification rates were found shortly after outbreak #1 and outbreak #2 (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Rate per 100 000 population of syphilis by type and diagnosis year (Alberta, Canada, 1975–2016). RSSS, Reverse sequence syphilis screening.

Figure 2.

Number and notification rate of early and late neurosyphilis by year (Alberta, 1975–2016).

Early neurosyphilis cases were significantly younger, more likely to be Caucasian, born in Canada, diagnosed in recent decades (2010s), reported same sex partners and HIV positive as compared with late neurosyphilis cases (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of early and late neurosyphilis (Alberta, 1973 to March 2017; n=250)

| Early neurosyphilis | Late neurosyphilis | Comparison of Early and Late p-Value | |||||||

| Asymptomatic (n=28) | Symptomatic (n=105) | Total (n=133) | P value | Asymptomatic (n=47) | Symptomatic (n=70) | Total (n=117) | P value | ||

| Median age (IQR) | 40 (32–46) | 47 (39–55) | 44 (36–54) | 0.02 | 45 (32–65) | 64 (53–75) | 58 (45–70) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 8 (28.6) | 12 (11.4) | 20 (15.0) | 0.02 | 6 (12.8) | 15 (21.4) | 21 (17.9) | 0.23 | 0.54 |

| Male | 20 (71.4) | 93 (88.6) | 113 (85.0) | 41 (87.2) | 55 (78.6) | 96 (82.1) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Indigenous | 6 (21.4) | 6 (5.7) | 12 (9.0) | 0.001 | 6 (12.8) | 3 (4.3) | 9 (7.7) | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 10 (35.7) | 78 (74.3) | 88 (66.2) | 14 (29.8) | 23 (32.9) | 37 (31.6) | |||

| Other | 3 (10.7) | 4 (3.8) | 7 (5.3) | 16 (34.0) | 27 (38.6) | 43 (36.8) | |||

| Unknown | 9 (32.1) | 17 (16.2) | 26 (19.5) | 11 (23.4) | 17 (24.3) | 28 (23.9) | |||

| Municipality | |||||||||

| Calgary | 9 (32.1) | 32 (30.5) | 41 (30.8) | 0.62 | 10 (21.3) | 22 (31.4) | 32 (27.4) | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| Edmonton | 15 (53.6) | 48 (45.7) | 63 (47.4) | 28 (59.6) | 35 (50.0) | 63 (53.8) | |||

| Other | 4 (14.3) | 25 (23.8) | 29 (21.8) | 9 (19.1) | 13 (18.6) | 22 (18.8) | |||

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| Canada | 16 (57.1) | 56 (53.3) | 72 (54.1) | 0.23 | 23 (48.9) | 16 (22.9) | 39 (33.3) | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Outside of Canada | 5 (17.9) | 9 (8.6) | 14 (10.5) | 17 (36.2) | 36 (51.4) | 53 (45.3) | |||

| Unknown | 7 (25.0) | 40 (38.1) | 47 (35.3) | 7 (14.9) | 18 (25.7) | 25 (21.4) | |||

| Decade of diagnosis | |||||||||

| 1970s | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.5) | 0.001 | 4 (8.5) | 1 (1.4) | 5 (4.3) | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| 1980s | 6 (21.4) | 3 (2.9) | 9 (6.8) | 13 (27.7) | 15 (21.4) | 28 (23.9) | |||

| 1990s | 3 (10.7) | 5 (4.8) | 8 (6.0) | 6 (12.8) | 9 (12.7) | 15 (12.8) | |||

| 2000s | 8 (28.6) | 28 (26.7) | 36 (27.1) | 4 (8.5) | 20 (28.6) | 24 (20.5) | |||

| 2010s | 10 (35.7) | 68 (64.8) | 78 (58.6) | 20 (42.6) | 25 (35.7) | 45 (38.5) | |||

| Sexual partners | |||||||||

| Heterosexual | 12 (42.9) | 46 (43.8) | 58 (43.6) | 1.00 | 30 (63.8) | 38 (54.3) | 68 (58.1) | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Same sex | 14 (50.0) | 52 (49.5) | 66 (49.6) | 11 (23.4) | 5 (7.1) | 16 (13.7) | |||

| Unknown | 2 (7.1) | 7 (6.7) | 9 (6.8) | 6 (12.8) | 27 (38.6) | 33 (28.2) | |||

| HIV status | |||||||||

| Negative | 5 (17.9) | 68 (64.8) | 73 (54.9) | <0.001 | 19 (40.4) | 27 (38.6) | 46 (39.3) | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 17 (60.7) | 30 (28.6) | 47 (35.3) | 8 (17.0) | 6 (8.6) | 14 (12.0) | |||

| Unknown | 6 (21.4) | 7 (6.7) | 13 (9.8) | 20 (42.6) | 37 (52.9) | 57 (48.7) | |||

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Penicillin G | 22 (78.6) | 82 (78.1) | 104 (78.2) | 0.87 | 21 (44.7) | 63 (90.0) | 84 (71.8) | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Ceftriaxone | 3 (10.7) | 14 (13.3) | 17 (12.8) | 12 (25.5) | 5 (7.1) | 17 (14.5) | |||

| Other | 3 (10.7) | 9 (8.6) | 12 (9.0) | 14 (29.8) | 2 (2.9) | 16 (13.7) | |||

Among early neurosyphilis cases, 79.0% (n=105) were symptomatic; symptomatic cases were more likely to be older, male, Caucasian, recently diagnosed (2010s) and HIV negative compared with asymptomatic cases. Among late neurosyphilis cases, 59.8% (n=70) were symptomatic; symptomatic cases were more likely to be older, born outside of Canada and treated with intravenous penicillin G and less likely to have a same sex partner as compared with asymptomatic cases.

The majority (79.9%; n=139) of symptomatic cases reported a single manifestation. The most common clinical manifestation of the symptomatic cases (41.1%; n=72) was ocular involvement; early neurosyphilis cases were more likely to have ocular involvement than late neurosyphilis cases (table 3). The first case of ocular syphilis was reported in 1990 with the majority (68.1%; n=49) of cases being diagnosed between 2010 and 2017. The second most common (33.7%; n=59) manifestation of symptomatic neurosyphilis was cognitive impairment with significantly more late neurosyphilis cases reporting these symptoms than early cases. Twelve (6.9%) cases reported auditory symptoms and 10.9% (n=19) reported ataxia. Nearly one-third (29.7%; n=52) of cases reported other symptoms including aphasia, stroke, reduced level of consciousness, headache and unspecified neurological symptoms.

Table 3.

Manifestations of early and late symptomatic neurosyphilis (Alberta, 1973–March 2017; n=175)

| Manifestation | Early neurosyphilis (n=105) | Late neurosyphilis (n=70) | P value |

| Ocular | 59 (56.2) | 13 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 20 (19.0) | 39 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| Ataxia | 9 (8.6) | 10 (14.3) | 0.23 |

| Auditory | 10 (9.5) | 2 (2.9) | 0.13 |

| Other* | 30 (28.6) | 22 (31.4) | 0.69 |

*Aphasia, reduced level of consciousness, headache, unspecified neurological symptoms.

Although the first HIV coinfected case was reported in 1986, over one-half (57.4%; n=35) of HIV coinfected cases were reported between 2010 and 2017. The majority (62.2%; n=46) of cases with an unknown HIV status occurred between the 1970’s and 1980’s, prior to the clinical availability of diagnostic serology. Cases that had HIV test results were significantly younger (47 years; IQR: 37–55) than cases without HIV test results (64 years; IQR: 44–70; P<0.001).

Thirty-six (14.2%) of all the cases were diagnosed without a lumbar puncture result. Nearly all of these clinical cases (97.2%; n=35) were symptomatic. The remaining asymptomatic case was diagnosed based on an inadequate fall in RPR titres over time. There was no significant difference by HIV status for those who had and did not have a lumbar puncture (P=0.62). Clinical parameters by HIV status are outlined in figure 3. Of the 2 HIV-positive and 6 HIV-negative cases with negative clinical parameters, all were symptomatic cases.

Figure 3.

Algorithm of diagnosis of neurosyphilis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative cases (Alberta, 1975–March 2017). CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorbed test; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory; WBC, white blood cell count.

The majority (74.4%; n=189) of all cases were treated with intravenous penicillin G. Asymptomatic late neurosyphilis cases were less likely to be treated with penicillin G (44.7%; n=21) as compared with symptomatic late neurosyphilis (90.0%; n=63; p<0.001). There was a rise in the use of ceftriaxone in late neurosyphilis treatment from no use in the 1970s to 1990s, to 12.5% (n=3) in 2000s and 31.1% (n=14) in the 2010s. Other drug combinations for neurosyphilis were highest in the 1970s (85.7%; n=6) and dropped to a low of 4.3% (n=1) in the 1990s.

Discussion

A review of the trends in reported cases of infectious syphilis from 1975 to March, 2017 in Alberta shows a cycling in the number of cases over time. During this time period, the first major outbreak of infectious syphilis occurred between 1981 and 1987, with the majority of cases between 1983 and 1985.20 A quiescent period of approximately two decades followed with a resurgence in infectious cases in 2000 followed by a decline in 2011 and then another rise in 2015. These observations are consistent with a study of long-term trends in reported primary and secondary syphilis cases in the USA which showed recurrent peaks and troughs in approximately 10 year cycles.21 This pattern of periodic resurgence of syphilis has variously been attributed to either failure to sustain control efforts, changing risk behaviours (such as crack cocaine use) and waxing and waning partial host immunity to infection at the population level.22 23 Interestingly, our province observed a 20-year gap between the outbreak in the mid 1980s and the mid 2000s. The reasons for this prolonged gap are unclear but are likely multifactorial including a well-established and sustained prevention and control programme for STIs in the province, emergence of HIV and the mass education that occurred during this time period. This theory is supported by declining notification rates of gonorrhoea and chlamydia until 1998 and then subsequent rises to current rates.24 Our observed rising notification rates of infectious syphilis since the mid-2000s are consistent with many jurisdictions across Canada and the USA.14 25 The rise in late latent syphilis in 2007 has been attributed to the introduction of RSSS.26

Some studies have reported a rise in cases of neurosyphilis related to outbreaks of infectious syphilis. One possible explanation for this is that the overall rise in notification rates of infectious syphilis could potentially increase the pool of persons progressing to neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis. For example, a study conducted in British Columbia, one of Alberta’s neighbouring provinces, reported that in the context of rising rates of infectious syphilis, the neurosyphilis rate was 0.03 per 100 000 in 1992 and increased 27-fold to 0.8 per 100 000 in 2012.27 Investigators from Guangdong province in China similarly reported an incidence rate increase in neurosyphilis cases from 0.21 cases per 100 000 persons in 2009 to 0.31 cases per 100 000 persons in 2014 and in tertiary cases from 0.28 cases per 100 000 persons in 2009 to 0.36 cases per 100 000 persons in 2014.28 Neither of these studies, however, distinguished between early and late neurosyphilis cases. In our review, we observed a significant rise in early neurosyphilis during the outbreak periods and a significant decline after the outbreak periods, for example, only one case was observed in 2012 after the second outbreak. We had expected to see a sustained increase in late neurosyphilis cases based on the hypothesis that the number of untreated infected persons with syphilis would increase over time but there was no significant increase during the overall observation period. Interestingly, a rise in late neurosyphilis cases was observed towards the end of the outbreak periods, perhaps due to heightened awareness and increased testing due to public health announcements during the outbreak periods and also because late (tertiary) neurosyphilis can occur as soon as 2 years postinfection.1 Although individuals diagnosed with late symptomatic neurosyphilis are not infectious and therefore not of concern from a public health perspective, these individuals would benefit from screening and appropriate treatment for syphilis to prevent complications of tertiary syphilis.1

Early neurosyphilis cases were more likely to be younger, Caucasian, born in Canada, HIV positive and reporting same sex partners. These observations parallel the observed rise in infectious syphilis during the third outbreak and may also be related to selection bias since lumbar punctures were more likely to be performed in HIV positive persons in the early years, especially those with low CD4 counts (<350) and/or RPR>1:32 dilutions as recommended in the Canadian STI Guidelines.29 In addition, most clinicians providing care to HIV positive individuals in Alberta would have offered regular syphilis screening in HIV-positive individuals, as endorsed for several years in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines.30

The most common manifestation (40%) of symptomatic neurosyphilis was ocular involvement with cases of early neurosyphilis more likely than cases of late neurosyphilis to have ocular involvement (54% vs 17%, p<0.001). Two-thirds of ocular cases were reported between 2010 and 2017, with 46.4% reported among MSM, similar to other studies.31 Late neurosyphilis cases were more likely to be older, born outside of Canada and less likely to report same sex partners, paralleling the demographics of late latent cases of syphilis in our province (data not shown).

Our study identified very few (n=3) CV cases of tertiary syphilis with all cases identified at the time of a diagnosis of aortic aneurysm. This likely represents an underestimate in the actual number of cases of CV syphilis as we suspect that most patients with aortic aneurysm or initial CV involvement do not have syphilis testing performed. In Alberta, the provincial STI programme facilitates the assessment of all late stage syphilis cases by a physician who then conducts a neurological and CV examination. A chest radiograph, recommended in the past in some jurisdictions to look for linear calcification of the ascending aorta, a radiological sign of syphilitic aortitis is not routinely done. Chest radiographs for the evaluation of CV syphilis in asymptomatic patients with LLS is of such low yield, that it is not routinely recommended.32 Neither clinical examination nor chest radiograph is likely to be sensitive enough to identify cases of CV syphilis and given the presumed rarity of this condition and that the treatment is the same as for LLS, further evaluations (eg, echocardiograms) are not warranted.

No cases of gummatous syphilis were reported during our study period. Although syphilitic gummas were reported in up to 15% cases in the preantibiotic era, it is possible that the widespread use of antibiotics for other conditions, which may indirectly treat or partially treat syphilis, has affected the occurrence.

One of the strengths of our study is that there was consistent reporting of all cases with positive syphilis serology over time by laboratories and active follow-up by the provincial STI programme with healthcare providers. We were able to apply current case definitions retrospectively to all cases; however, one of the limitations to retrospective review of data is the possibility of inaccurate classification of cases. Our review by two experienced medical consultants resulted in only one case where insufficient information was available to classify the case with reasonable accuracy. Additional study limitations include changes in and quality of data collection practices over time, with improved data quality over time. The information about gender of sex partners may have been inaccurate in earlier years due to stigma associated with same sex partners. Routine testing for HIV in cases of syphilis was also not conducted in earlier years and as such the number of concurrent HIV infections may be underestimated.

In summary, our review of tertiary and neurosyphilis cases in Alberta over a 44-year period found that early and late neurosyphilis cases continue to occur in the context of cycling of infectious syphilis outbreaks. Ocular disease was the most common manifestation of neurosyphilis in our study. On the other hand, CV syphilis was extremely rare and no cases of gumma were identified. Ongoing identification of syphilis cases with prompt treatment and follow-up continues to be important in the context of resurgence of infectious syphilis worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TL reviewed hard copy records of all cases and conducted data entry into an Excel file. PS and AES reviewed and reclassified all cases. JG conducted data analysis. JG and AES drafted initial versions of the manuscript. TL, PS, RC, JG, LB, RR, BR and AES helped develop the study design and reviewed drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: TL received funding as a post secondary summer student from Alberta Health Services.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA 2003;290:1510–4. 10.1001/jama.290.11.1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gjestland T. The Oslo study of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation of the natural course of syphilitic infection based on a restudy of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. J Chronic Dis 1955;2:311–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kent ME, Romanelli F. Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:226–36. 10.1345/aph.1K086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kampmeier RH. The late manifestations of syphilis: skeletal, visceral and cardiovascular. Med Clin North Am 1964;48:667–97. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)33449-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cole HN. Cooperative clinical studies in the treatment of syphilis. The effect of specific therapy on the prophylaxis and progress of cardiovascular syphilis. JAMA 1937;108:1861–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howles JK. Synopsis of clinical syphilis. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Co, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Continuum 2015;21:1714–28. 10.1212/CON.0000000000000250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Merritt HH. Neurosyphilis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berry CD, Hooton TM, Collier AC, et al. Neurologic relapse after benzathine penicillin therapy for secondary syphilis in a patient with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1587–9. 10.1056/NEJM198706183162507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johns DR, Tierney M, Felsenstein D. Alteration in the natural history of neurosyphilis by concurrent infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1569–72. 10.1056/NEJM198706183162503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, et al. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. The Syphilis and HIV Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997;337:307–14. 10.1056/NEJM199707313370504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lukehart SA, Hook EW, Baker-Zander SA, et al. Invasion of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med 1988;109:855–62. 10.7326/0003-4819-109-11-855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Musher DM, Hamill RJ, Baughn RE. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the course of syphilis and on the response to treatment. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:872–81. 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on sexually transmitted infections in Canada: 374 2013-2014. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/report-sexually-transmitted-infections-canada-2013-14.html#a41 (Accessed 27 Mar 2018).

- 15. Government of Alberta. Interactive Health Data Application. STI-Age-Sex Specific 378 Incidence Rate. http://www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/redirectToURL.do?cat=81&subCat=466 (Accessed 12 Jun 2018).

- 16. Daey Ouwens IM, Koedijk FD, Fiolet AT, et al. Neurosyphilis in the mixed urban-rural community of the Netherlands. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2014;26:186–92. 10.1017/neu.2013.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Government of Alberta Public Health Notifiable Disease Management Guidelines. Syphilis. 2012. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/e234483d-fc2d-4bbf-a248-e0442808187e/resource/244eaccc-c0ac-4933-9347-a908cbbc45f0/download/Guidelines-Syphilis-2012.pdf (Accessed 26 Apr 2018).

- 18. Government of Alberta. Interactive Health Data Application. Population Estimates. http://www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/redirectToURL.do?cat=5&subCat=63 (Accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 19. Government of Alberta Public Health Notifiable Disease Management Guidelines. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). 2011. https://open.alberta.ca/publications/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv (Accessed 24 Jul 2018).

- 20. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Love EJ, et al. Epidemiology of an outbreak of infectious syphilis in Alberta. Int J STD AIDS 1991;2:424–7. 10.1177/095646249100200606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakashima AK, Rolfs RT, Flock ML, et al. Epidemiology of syphilis in the United States, 1941--1993. Sex Transm Dis 1996;23:16–23. 10.1097/00007435-199601000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grassly NC, Fraser C, Garnett GP. Host immunity and synchronized epidemics of syphilis across the United States. Nature 2005;433:417–21. 10.1038/nature03072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grenfell B, Bjørnstad O. Epidemic cycling and immunity. Nature 2005;433:366–7. 10.1038/433366a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alberta Health and Wellness. Sexually transmitted infections surveillance report: Alberta – 1998 to 2002. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/262e0d89-1fbe-4120-b521-d0b586caea0b/resource/e2fd112f-7d7d-4f2e-accb-8afd38af4dba/download/sti-surveillance-2002.pdf (Accessed 13 Mar 2019).

- 25. Patton ME, JR S, Nelson R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Primary and secondary syphilis-United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:402–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gratrix J, Plitt S, Lee BE, et al. Impact of reverse sequence syphilis screening on new diagnoses of late latent syphilis in Edmonton, Canada. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:528–30. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824e53f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lester RT, Morshed M, Gilbert M, et al. Syphilis and neurosyphilis increase to historic levels in BC. BC Med 2013;55:204–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tang W, Huang S, Chen L, et al. Late neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis in Guangdong Province, China: results from a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 2017;7:45339 10.1038/srep45339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections-Management and treatment of specific infections-Syphilis. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines/sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines-sexually-transmitted-infections-27.html (Accessed 11 Jul 2018).

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, American Academy of HIV Medicine, Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, the National Minority AIDS Council, and Urban Coalition for HIV/AIDS Prevention Services. Recommendations for HIV Prevention with Adults and Adolescents with HIV in the United States. 2014. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/26062 (Accessed 10 Mar 2019).

- 31. Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular Syphilis - Eight Jurisdictions, United States, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1185–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6543a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dabis R, Radcliffe K. Is it useful to perform a chest X-ray in asymptomatic patients with late latent syphilis? Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:105–6. 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.