Abstract

Beijing’s reforms have succeeded in reducing hospitals’ reliance on drug sales and shifting patients to primary care, say Xiaoyun Liu and colleagues

Key messages.

In 2017, Beijing implemented a comprehensive public hospital reform which focused on separating drug sales from hospital revenues and adjusting the prices of medical services. The aim was to reduce the heavy reliance of public hospitals on drug sales and to contain the escalating medical expenditure

The reform succeeded in reducing drug sales as a proportion of total hospital revenues and redirected the flow of outpatients from tertiary hospitals to community health centre.

An unintended consequence of the reform, however, has been an increasing use of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography

An alignment of incentives between public hospitals, health workers, and patients was a key driver of these changes

The experiences gained from the Beijing reform may help inform further reforms of public hospitals in China and in other countries with similar systems

Public hospitals in China (tertiary and secondary hospitals) have strong incentives to make a profit from drug sales and high value medical consumables, and this has become a target for change over the past decade.1 Since 2009, China has been piloting public hospital reforms to reduce these incentives, as part of an overall reform of the health system.2 Several initiatives have been undertaken, focusing on governance and management structures, compensation mechanisms, and provider payment methods.3 While these reforms have made some progress, the challenges of increasing medical expenditure and a heavy reliance on drug sales have not been adequately dealt with; nor has the profit driven behaviour of the public hospitals been sufficiently reversed.3 4 Patients continue to bypass primary healthcare to seek expensive secondary and tertiary healthcare, even for conditions that are not serious.5

Central government has encouraged local governments to pilot innovative interventions to gain experience in this important field of health system reform. In this context, Beijing municipal government initiated a comprehensive public hospital reform in 2017 to contain the rapid increase in medical expenditure. This paper presents this innovative case study of public hospital reform in Beijing to draw from the experience and lessons learnt.

What was proposed in the Beijing public hospital reform?

Beijing has a large population of 21.7 million, and in 2017 the gross domestic product per capita was ¥128 927 (£14 785; $18 662; €16 760), ranking first in China. It has 116 tertiary hospitals, more than any other city in China. Public hospitals in Beijing play a more dominant part in providing medical services than in other regions of China. Among all outpatient visits in Beijing in 2016, 63% were at public hospitals and only 27.1% were in primary healthcare settings, much lower than the national average of 55.1%. In 2016, more than 45.1% of revenues in tertiary public hospitals in Beijing were from drug sales, while the national average was 38.9%.6

The Beijing municipal government started a comprehensive public hospital reform in April 2017 (see table 1 for details) aimed at promoting use of primary healthcare services, containing the escalating medical expenditure, and reducing the proportion of revenues from drug sales to rebuild an appropriate compensation mechanism for public hospitals.7 Dual leadership of the National Health Commission and Beijing municipal government was set up to coordinate the policy development and implementation process. The Beijing Health Commission acted as the implementation organisation to coordinate with other sectors, including departments of finance, civil affairs, and social security.

Table 1.

Reform measures at public hospitals in Beijing

| Reform measures | Descriptions of reform measures |

|---|---|

| Zero mark-up of drug sales | 15% mark-up from drug sales removed in all public hospitals |

| Medical consultation service fees | A tiered schedule: higher level hospitals and senior physicians can charge higher service fees. For example, the consultant service fee for an outpatient visit is raised from ¥5 to ¥50 in tertiary hospitals, ¥30 in secondary hospitals, and ¥20 in primary healthcare facilities (for junior physicians). Patients’ co-payment on medical consultation service fees are ¥10, ¥2, and ¥,1 respectively. For senior physicians, the new consultant service fee is ¥80, ¥70, and ¥60, respectively |

| Price adjustment | Prices of 435 medical service items are adjusted, with increased prices for surgical operations and traditional Chinese medicine services and decreased prices for medical investigations (eg CT and MRI). All these services with changed prices are covered by social health insurance schemes. The co-payment level remained the same |

| Availability of medicines | More types of medicine, especially for non-communicable chronic diseases, are available at primary healthcare facilities The length of prescriptions for patients with non-communicable diseases is extended from one month to two months at primary healthcare facilities |

The reform focused on price adjustment of drugs and medical services. Based on national guidelines, the 15% mark-up from drug sales was removed in all public hospitals to reduce reliance of public hospitals on profits from drug sales. Prices of 435 medical service items were adjusted to guide health professionals’ service provision behaviour, with increased prices for surgical operations and traditional Chinese medicine services and decreased prices for medical investigations (for example, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)). In addition, the Beijing reform set up innovative medical consultation service fees to better compensate public hospitals’ financial loss from the zero mark-up policy for drugs and to better reflect doctors’ professional values.

To encourage use of primary care services, the reform improved the availability of medicines at primary healthcare facilities, especially for patients with chronic diseases. The medical consultation service fee is a tiered charge: tertiary hospitals, secondary hospitals, and primary healthcare facilities. Patients’ co-payments on medical consultation service fees at primary healthcare facilities are less than those at secondary and tertiary hospitals.

The reform design was based on experiences from a pilot reform in five public hospitals starting in 2012.8 Potential financial gains and losses at public hospitals were estimated to inform the design of price adjustment.

What has been achieved since the reform began?

Results on flow of outpatients and length of stay of inpatients

One of the most important achievements of the Beijing public hospital reform is that it managed to redirect the flow of outpatients from tertiary hospitals to community health centres.9 One year after the reform, there was an 11.9% decrease in outpatient service volumes in tertiary hospitals, while the primary healthcare facilities had a 15.0% increase. Figure 1 shows the increasing trend of outpatient visits in primary healthcare facilities based on an analysis of interrupted time series.10 As a comparison, over the same period outpatient service volumes in the entire country had a 6.1% increase in tertiary hospitals and a 1.4% increase in primary healthcare facilities.6

Fig 1.

Interrupted time series of outpatient visits to primary healthcare facilities in Beijing (2016-2017)

Two possible reasons may explain these positive results.9 Firstly, the higher consultant service fee and higher co-payment in tertiary hospitals compared with primary healthcare facilities provided an incentive for some patients with minor illnesses to use primary healthcare services instead of tertiary services, especially older patients whose outpatient visits were mainly to refill their prescriptions for non-communicable diseases. Secondly, the increasing availability of more essential medicines for non-communicable diseases and prescriptions for a longer period (up to 2 months) at primary healthcare facilities may attract more patients to use primary healthcare services.

The potential revenue loss from drug mark-up pushed public hospitals to improve their efficiency in use of resources and service provision. As a result, the average length of stay for inpatient services fell from 8.9 days to 8.3 days in tertiary hospitals and from 10.0 days to 8.8 days in secondary hospitals.

Results on cost containment and public hospitals’ revenue structure

The reform led to a slowed rate of growth for medical expenditure and a changed structure of public hospitals’ revenues.10 The annual growth of total health expenditure fell from 6.94% before the reform to 4.73% afterwards.6 In tertiary hospitals the proportion of drug sales in total hospital revenues fell from 45.14% to 36.98%; in primary healthcare facilities, the proportion decreased by 2.79% (table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of drug revenues in total service revenues in public hospitals in Beijing (%)

| Pre-reform | Post-reform | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospitals | 45.14 | 36.98 | -8.16 |

| Secondary hospitals | 52.03 | 44.25 | -7.78 |

| Primary healthcare facilities | 83.77 | 80.98 | -2.79 |

The shift in outpatient volume from tertiary hospitals to primary healthcare facilities was the main mechanism for the slowed rate of growth of medical expenditure. Patients with more severe diseases still received outpatient care in tertiary hospitals, which may have increased the cost per visit. This contributed 13.1% to the growth of total outpatient expenditure in tertiary hospitals; the decrease in outpatient service volumes contributed -11.9% to this growth. As a result, the annual growth of total outpatient expenditure was only 0.4%.11 The promotion of primary healthcare services helped to leave more health resources at tertiary hospitals for patients with more severe conditions.

The reduction in the proportion of drug revenues in total service revenues was due mainly to removal of the 15% drug mark-up. This may help reverse the longstanding distorted incentive towards drug sales in public hospitals. For most hospitals, loss of revenues from the drug zero mark-up policy can be compensated for by adjusting the service consultation fee, among other price adjustments.10

What should be done now to further progress?

Beijing has made a huge step towards containing medical expenditure through the public hospital reform. While these experiences are useful for other parts of China and other countries with similar systems, Beijing needs further efforts to consolidate its health system reforms.

Further regulations to reduce unnecessary use of high value medical investigations and consumables

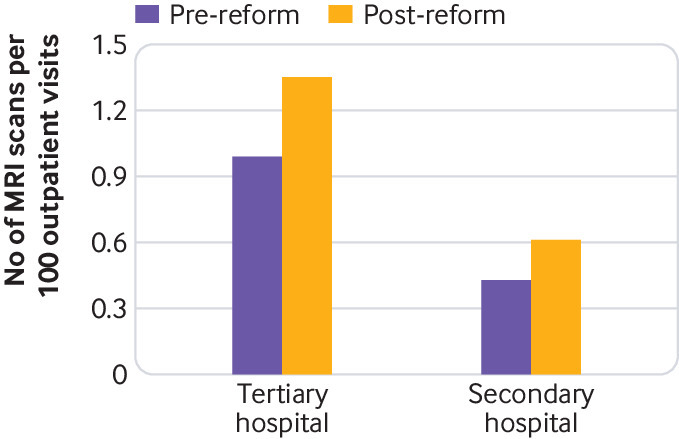

The decreased price of CT and MRI scans aimed to reduce the reliance of public hospitals on revenues generated from these expensive medical investigations. However, profit driven behaviour of public hospitals cannot be fully dealt with overnight. Public hospitals may shift costs from medicines to other high value medical consumables or clinical processes.12 A 35.7% increase in MRI in tertiary hospitals and a 41.47% increase in secondary hospitals was noted after the reform (fig 2). This may be because hospitals are trying to increase their CT and MRI service volumes to compensate for the financial loss due to the price reduction.9

Fig 2.

Number of magnetic resonance imaging scans per 100 outpatient visits in secondary and tertiary hospitals

To overcome this unintended consequence, health authorities and health insurance agencies should strengthen regulations to reduce unnecessary use of these high cost medical investigations and consumables. Price adjustment of more service items and provider payment reform should be implemented to further reduce the profit driven behaviour of public hospitals and health workers.

Strengthening primary healthcare capacity

The Beijing reform has succeeded in directing some patients with mild illnesses from tertiary hospitals to primary healthcare facilities. Primary healthcare providers have higher workloads of outpatient services than before the reform. Without sufficient investment, the quality of primary healthcare may decrease.

Primary healthcare facilities need to strengthen their capacity to provide good quality health services to accommodate the increasing workloads after the reform. This includes improving quantity and quality of human resources, financial and non-financial incentives, and other quality assurance mechanisms.5

Monitoring and evaluation on quality of care and health outcome

The Beijing reform has closely monitored key indicators from a sample of public hospitals each day since the policy implementation. A research team from Peking University led an independent evaluation on the policy process and results. The monitoring and evaluation activities are helpful in drawing lessons learnt from the reform. However, these activities mainly focus on service utilisation and medical expenditure. The achievement of the reform on cost containment and more use of primary healthcare services should not be at the expense of service quality and health outcomes. Long term monitoring and evaluation activities should be conducted to evaluate the impact of the reform on quality of care and health outcomes.

Conclusions

The Beijing reform of public hospitals used price adjustment to contain the rise in medical expenditure. It achieved its objectives mainly through encouraging patients with mild illnesses to use primary healthcare services rather than tertiary hospitals. Alignment of incentives among different stakeholders including public hospitals, health workers, and patients have been the key drivers of these changes. As China is yet to develop a gate keeping system, as is found in most developed countries, the reform in Beijing helps set a pioneering example of using pricing reform in public hospitals to contain rising medical costs and promote the establishment of a tiered service delivery system.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Beijing Health Commission for their support in providing data and information. Zhuang Yu, Zhou Shuduo, and Yang Shuo, from Peking University, provided technical assistance in data analysis. James Chia, from Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, helped proofread the paper.

For other articles in the series see: www.bmj.com/china-health-reform

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Chinese translation

Contributors and sources: XL, JX, BY, and QM have studied and reported widely on China’s health system reform. XM and HF are health economists. XL and QM led the evaluation of Beijing public hospital. All authors participated in study design, data collection, and analysis. XL drafted the paper. All authors contributed to the revision and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series proposed by the Peking University China Center for Health Development Studies and commissioned by The BMJ. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication of these articles. Open access fees are funded by Peking University China Center for Health Development Studies.

References

- 1. Meng Q, Mills A, Wang L, et al. What can we learn from China’s health system reform? BMJ 2019;365:l2349 10.1136/bmj.l2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, Stata Council. Opinions on deepening health system reform. Zhongfa [2009] No 6. 2009

- 3. Xu J, Jian W, Zhu K, et al. Reforming public hospital financing in China: progress and challenges. BMJ 2019;365:l4015. 10.1136/bmj.l4015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He J. China’s ongoing public hospital reform: initiatives, constraints and prospect. Journal of Asian Public Policy 2011;4:342-9 10.1080/17516234.2011.630228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ma X, Wang H, Yang L, et al. Realigning the incentive system for China’s primary health care providers. BMJ 2019;365:l2406 10.1136/bmj.l2406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Health Commission Health statistics yearbook 2018. Peking Union Medical College Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beijing Municipal Government Implementation plan for comprehensive reform on separating drug sales from hospital revenues. Beijing Municipal Government. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng G, Zhu H, Fu M. An empirical study on the effect of Beijing’s reform of separating medical services from pharmaceutical services. Chinese Journal of Hospital Administration 2014;30:881-5. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou S, Zhuang Y, Yang S, et al. The comprehensive reform of separating drug sales from medical services and its impact on outpatients and emergency medical flow in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Health Policy 2018;11:37-41. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhuang Y. Effectiveness evaluation of comprehensive reform of abolishing drug-markup on medical expenditure containment in Beijing. Peking University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhuang Y, Zhou S, Yang S, et al. The impact of separating drug sales from medical services reform on mechanism of controlling outpatient and emergency expenses in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Health Policy 2017;10:9-14. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee IH, Bloor K, Hewitt C, Maynard A. International experience in controlling pharmaceutical expenditure: influencing patients and providers and regulating industry - a systematic review. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 2015;20:52-9. 10.1177/1355819614545675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chinese translation