Abstract

HDAC inhibitors have been developed very rapidly in clinical trials and even in approvals for treating several cancers. However, there are few reported HDAC inhibitors designed from Nɛ-acetyl lysine. In the current study, we raised a novel design, which concerns Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives containing amide acetyl groups with the hybridization of ZBG groups as novel HDAC inhibitors.

Keywords: Nɛ-acetyl lysine, ZBG group, analogues, hybridization, HDAC inhibitor

1. Introduction

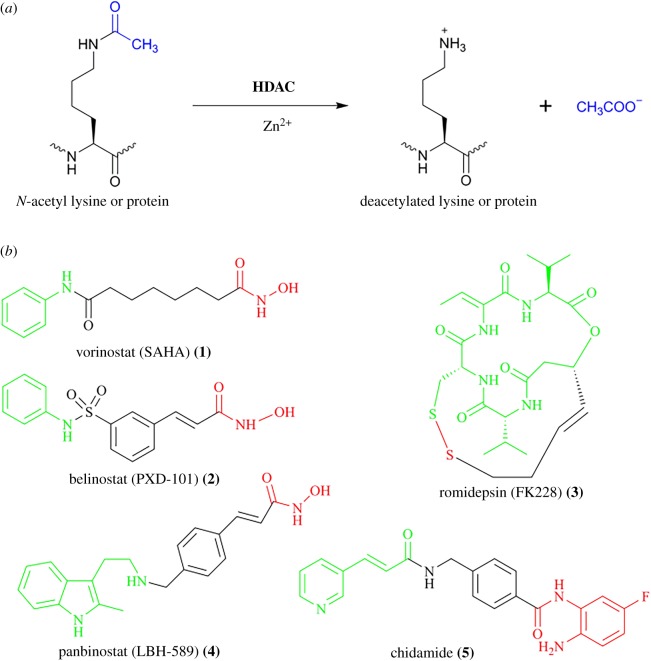

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are a class of hydrolases that remove acetyl groups from lysine residues of proteins, and play a very important role in the regulation of many biological processes, including transcription, genome stability, metabolism, protein activity, lifespan and so on [1–4]. According to sequence identity and similarity, human HDACs have been typically divided into four classes [5,6]. Class I consists of HDAC 1, 2, 3 and 8 while Class II includes HDAC 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10, which is further divided into two subclasses: Class IIa (HDAC 4, 5, 7 and 9) and Class IIb (HDAC 6 and 10). Class IV has only one member, called HDAC 11. Notably, Class I, Class II and Class IV are all Zinc (Zn2+) dependent deacetylases (figure 1a), whereas Class III is a family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacylases, which is also known as sirtuin and contains seven members (SIRT 1–7). Because of their critical role in cell proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis of cancer cells, HDACs have been considered as promising therapeutic targets for treating cancer [7–13]. Furthermore, the development of HDAC inhibitors has been proven to be an efficient strategy for cancer treatment. Indeed, there are many HDAC inhibitors currently in clinical trials and there are even five HDAC inhibitors already on the market. Vorinostat (SAHA) 1 [14], belinostat (PXD-101) 2 [15] and romidepsin (FK228) 3 [16] have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) or peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) while panbinostat (LBH-589) 4 [17] has also been approved by the FDA for the treatment of multiple myeloma (figure 1b). Recently, chidamide 5 [18] was approved by the China Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of PTCL (figure 1b).

Figure 1.

HDAC (Zn2+-dependent deacetylases) and approved HDAC inhibitors. (a) HDAC catalysed deacetylation; (b) the structural features of approved HDAC inhibitors: their common structural characteristics have been defined as three components, which are a cap group as surface recognition marked with green, a linker marked with black, and a zinc binding group (ZBG) marked with red that can chelate the zinc (II) cation.

Of these five approved HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat (SAHA) 1, belinostat (PXD-101) 2, romidepsin (FK228) 3 and panbinostat (LBH-589) 4 are all pan-HDAC inhibitors, which exhibit a lack of isoform selectivity (figure 1b) [14–17]. However, chidamide 5 is the first selective HDAC inhibitor to obtain marketing approval in China so far (figure 1b) [18]. Whether they are pan- or selective- HDAC inhibitors, three common structural characteristics have been defined, which are a cap group as surface recognition (marked with green), a linker (marked with black) and a zinc binding group (ZBG) (marked with red) that can chelate the zinc (II) cation (figure 1b). Typically, ZBG groups include the hydroxamate group, thiol group and amino benzamide.

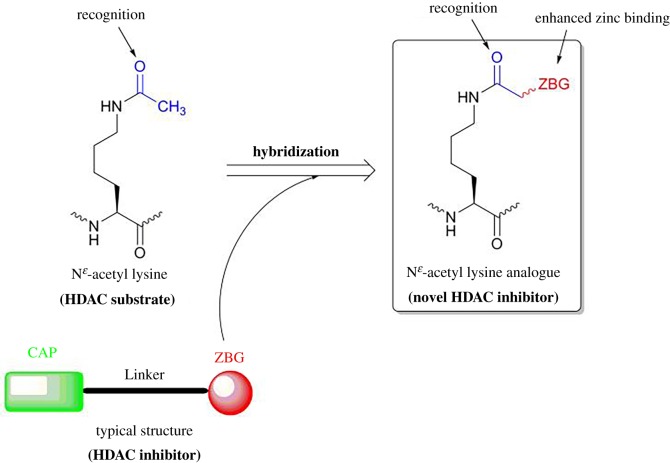

Although considerable progress has been made in the development of HDAC inhibitors, clinically used HDAC inhibitors still have some side effects, such as excessive toxicities, instability and off-target effects [19–23]. Therefore, the continued development of novel HDAC inhibitors is needed to avoid side effects and improve their pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties [24–26]. At present, there are few HDAC inhibitors designed from Nɛ-acetyl lysine (HDAC substrate) while the designs of sirtuin inhibitors by mimicking Nɛ-acyl lysine (sirtuin substrate) have led to many successful examples [27–30]. Considering this, our design herein is based on the hypothesis that Nɛ-acetyl lysine (HDAC substrate) derivatives containing amide acetyl groups with the hybridization of the ZBG group may help their recognition of HDAC and further enhance the zinc binding in the HDAC active site, thus inhibiting HDAC activity (figure 2). We report here the synthesis of the new hybrid compounds, the evaluation of their HDAC inhibition and preliminary results in anti-cancer activities on several cancer cell lines.

Figure 2.

The design of a novel HDAC inhibitor based on Nɛ-acetyl lysine and ZBG of typical HDAC inhibitors.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

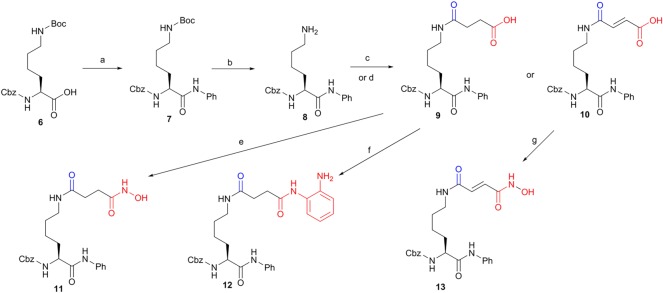

The synthesis of Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives started from the condensation of commercial Nɛ-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl(Boc)-Nα-carbobenzoxyl(Cbz)-L-lysine 6 with aniline in the presence of N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide as a coupling reagent to obtain compound 7. After the deprotection of the Boc group by treating compound 7 with trifluoroacetic acid, the key intermediate 8 was achieved in a yield of 85% for two steps. After the reaction of compound 8 with succinic anhydride or maleic anhydride, compounds 9 and 10 were obtained, respectively. The desired hydroxamic acid 11 was achieved by the treatment of compound 9 with hydroxyl amine while the amino benzamide 12 was given by the coupling of 1,2-diaminobenzene with compound 9. Treatment of compound 10 with hydroxyl amine gave another desired hydroxamic acid 13 (scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

First run synthesis of the key intermediate 8 and compounds 9–13. Reagents and conditions: (a) aniline, 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), 3 h, 90%; (b) 33% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in CH2Cl2, 1 h, 95%; (c) succinic anhydride, triethylamine (TEA), THF, rt, 1 h, 90%; (d) maleic anhydride, TEA, rt, 1 h, 90%; (e) (i) isobutyl chloroformate (IBCF), TEA, THF, (ii) NH2OH·HCl, MeOH, 0°C to rt, 3 h, 42%; (f) 1,2-diaminobenzene, HBTU, DIEA, 80%, 4 h; (g) (i) IBCF, TEA, THF, (ii) NH2OH·HCl, MeOH, 0°C to rt, 3 h, 40%.

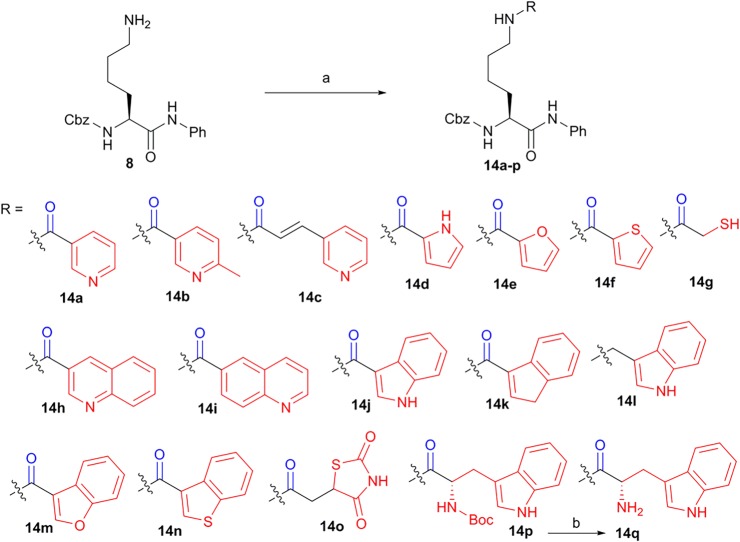

The intermediate 8 was coupled with different heterocyclic acids or an aromatic acid (1H-indene-3-carboxylic acid) to give compounds 14a-f, 14h-k and 14m-p, respectively. Compound 14g containing the thiol group was achieved by the condensation of compound 8 and 2-mercaptoacetic acid. The condensation of the intermediate 8 with indole-3-carboxaldehyde and then the reduction of imine gave compound 14l. Additionally, the deprotection of the Boc group of compound 14p by TFA gave compound 14q (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Second run synthesis of compounds 14a-q. Reagents and conditions: (a) HBTU, DIEA, indicated heterocyclic acids or an aromatic acid (1H-indene-3-carboxylic acid), rt, 3 h, 20–85% for 14a-k and 14m-q; (b) (i) indole-3-carboxaldehyde, dry MeOH, (ii) NaBH4, MeOH, 78% for 14l; (c) 33% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in CH2Cl2, 1 h, 95%.

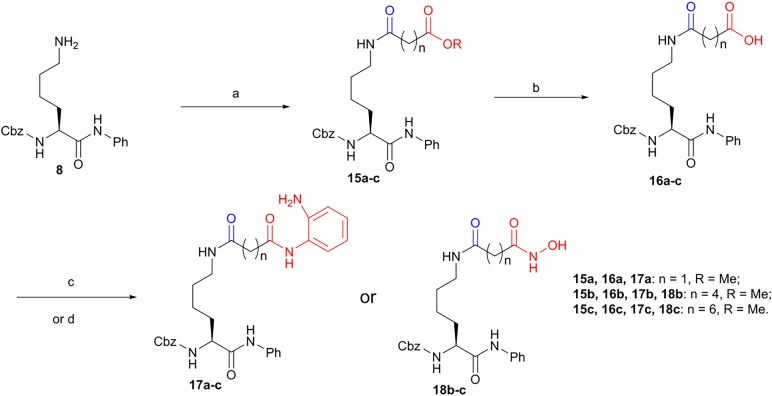

Amino benzamides 17a-c were synthesized from the intermediate 8. The intermediate 8 was first coupled with mono ethyl or monomethyl α, ω-dicarboxylic esters to give compounds 15a-c, which was hydrolysed to give compounds 16a-c. Then, the intermediates 16a-c were coupled with 1,2-diaminobenzene to obtain amino benzamides 17a-c, respectively. On the other hand, by the treatment of intermediates 16b-c with hydroxyl amine, hydroxamic acids 18b-c were finally obtained (scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Third run synthesis of amino benzamides 17a-c and hydroxamic acids 18b-c. Reagents and conditions: (a) indicated monoethyl or monomethyl α,ω-dicarboxylic esters, HBTU, DIEA, THF, rt, 3 h,73–88% for 15a-d; (b) LiOH, 25% H2O in THF, 0°C, 0.5 h, approximately 90%; (c) 1,2-diaminobenzene, HBTU, DIEA, rt, THF, 3 h, 60–80% for 17a-c; (d) NH2OH·HCl, MeOH, rt, 40–60% for 18b-c.

2.2. HDAC inhibition, cellular study and antiproliferative activity

With these Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives in hand (schemes 1–3), we then did the pilot screening for general HDAC inhibitory activity at a compound's concentration of 100 µM. All tested compounds were subjected to the inhibition assay against the HDAC deacetylation reaction by using a HeLa nuclear extract as a source of HDACs and BOC-Ac-Lys-AMC as a substrate. As shown in table 1, hydroxamic acid 11 showed better HDAC inhibition (86.0 ± 3.0%) than that of other first-run synthesized compounds (9, 10, 12, 13) (scheme 1). This indicated that the hybridization of hydroxamic acid might be the best choice compared to the hybridization of other ZBG groups like acid or amino benzamide. In the second run synthesis, we have incorporated not only another classic ZBG group like the thiol group but also other potential ZBG groups like heterocyclic groups into the candidate compounds (scheme 2). Unfortunately, none of them (14a-q) showed superior inhibition compared to that of hydroxamic acid 11 (14a-q versus 11, table 1). Although Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives with the hybridization of different heterocyclic groups could not greatly improve the inhibitory potency compared with those with the hybridization of aromatic group or non-keto heterocyclic group (14a-f, 14h-k versus 14k or 14l, table 1), most of those with the hybridization of heterocyclic groups did show some degree of HDAC inhibition (table 1). Among them, the best one is 14e with a furan group as a ZBG group showed the HDAC inhibition of 54.0 ± 1.9% at 100 µM (table 1). The introduction of the benzo group into the six-member heterocyclic group showed no obvious effects on the HDAC inhibition (14h-i versus 14a-b, table 1). However, the HDAC inhibition of 14m was dropped to 14.3 ± 0.5% when the furan group was replaced by the 2,3-benzofuran group (14m versus 14e, table 1). Similarly, the HDAC inhibitions of 14j and 14n were both decreased to 12.2 ± 6.5% and 16.2 ± 2.0%, respectively (14j versus 14d and 14n versus 14f, table 1).

Table 1.

Pilot screening of HDAC inhibiton for Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives containing acetyl group with the hybridization of ZBG groups (*100 µM; **10 µM).

| *Cmpd | HDAC inhibition (%) |

*Cmpd | HDAC inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 37.5 ± 0.6 | 14m | 14.3 ± 0.5 |

| 10 | 38.7 ± 1.0 | 14n | 16.2 ± 2.0 |

| 11 | 86.0 ± 3.0 | 14o | 48.6 ± 0.5 |

| 12 | 30.7 ± 3.7 | 14p | 24.7 ± 2.8 |

| 13 | 39.3 ± 3.1 | 14q | 36.2 ± 0.4 |

| 14a | 39.6 ± 0.4 | 15a | 19.4 ± 10.9 |

| 14b | 39.2 ± 0.8 | 15b | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| 14c | 51.0 ± 1.0 | 15c | 7.1 ± 0.3 |

| 14d | 48.4 ± 4.4 | 16a | 4.0 ± 1.7 |

| 14e | 54.0 ± 1.9 | 16b | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| 14f | 45.0 ± 0.4 | 16c | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| 14g | 10.3 ± 4.9 | 17a | 7.0 ± 0.4 |

| l4h | 28.3 ± 4.6 | 17b | 69.3 ± 3.4 |

| 14i | 36.8 ± 1.1 | 17c | 50.6 ± 6.9 |

| 14j | 12.2 ± 6.5 | 18b | 99.9 ± 0.9 |

| 14k | 22.4 ± 0.2 | 18c | 109.2 ± 0.5 |

| 14l | 3.1 ± 0.5 | **SAHA (1) | 102.2 ± 4.1 |

To further improve the inhibitory potency, we performed the third run synthesis of amino benzamides 17a-c and hydroxamic acids 18b-c, and their evaluation for HDAC inhibition. Again, amino benzamide and hydroxamic acid have been confirmed to be the most appropriate ZBG groups compared to carboxyl acid or carboxyl ester (17a-c and 18b-c versus 15a-c and 16a-c, table 1). By optimizing the length between the carbonyl of amide acetyl moiety and amino benzamide as a ZBG group, we found that amino benzamides 17b and 17c gave the better HDAC inhibition of 69.3 ± 3.4% and 50.6 ± 6.9%, respectively (17b-c versus 17a, table 1). Finally, hydroxamic acids 18b and 18c demonstrated the best inhibitory potency of 99.9 ± 0.9% and 109.2 ± 0.5% at 100 µM, respectively, which is comparable to the HDAC inhibition of SAHA (1) at 10 µM. Additionally, 18c and SAHA (1) demonstrated no obviously inhibitory selectivity between HDAC I and HDAC II (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

To further evaluate the inhibitory potency of hydroxamic acids 11 and 18b-c, we measured their IC50 values through the HDAC deacetylation reaction by using a HeLa nuclear extract as a source of HDACs and BOC-Ac-Lys-AMC as a substrate (table 2). The IC50 values of hydroxamic acids 11 and 18b were 25.36 ± 1.35 µM and 10.44 ± 3.86 µM, respectively (table 2). Hydroxamic acid 18c eventually turned out to be the most potent HDAC inhibitor with a IC50 value of 0.50 ± 0.21 µM, which like SAHA fell into the nanomolar range with an IC50 value of 0.05 ± 0.01 µM (18c versus SAHA (1), table 2).

Table 2.

IC50 values (μM) of Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives as HDAC inhibitors.

| inhibitor | HeLa nuclear extract |

|---|---|

| 11 | 25.36 ± 1.35 |

| 18b | 10.44 ± 3.86 |

| 18c | 0.50 ± 0.21 |

| SAHA (1) | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

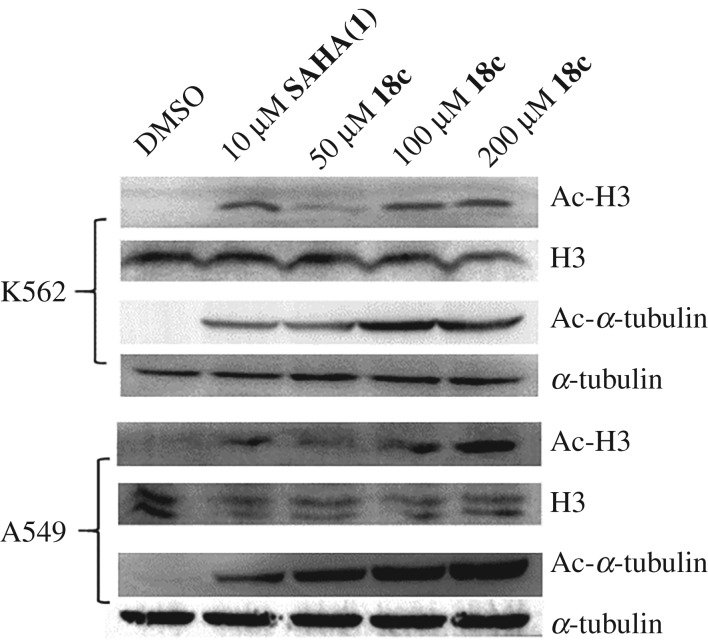

This result encouraged us to further evaluate whether hydroxamic acid 18c could work on the cellular HDACs. Therefore, hydroxamic acid 18c was engaged in western blotting analysis to evaluate the acetylation levels of histone H3 and α-tubulin. The leukaemia K562 and human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell lines were treated with hydroxamic acid 18c at 50, 100 and 200 µM for 24 h, in comparison with SAHA (1) at 10 µM as a positive control. As shown in figure 3, hydroxamic acid 18c induced a dose-dependent increase in acetylation levels of histone H3 and α-tubulin in both K562 and A549 cell lines. In other words, hydroxamic acid 18c was able to increase the acetylation levels of histone H3 and α-tubulin, suggesting that 18c could inhibit HDACs in cells.

Figure 3.

Cellular HDAC inhibition of hydroxamic acid 18c by western blotting analysis of the acetylation levels of histone H3 and α-tubulin in K562 and A549 cell lines.

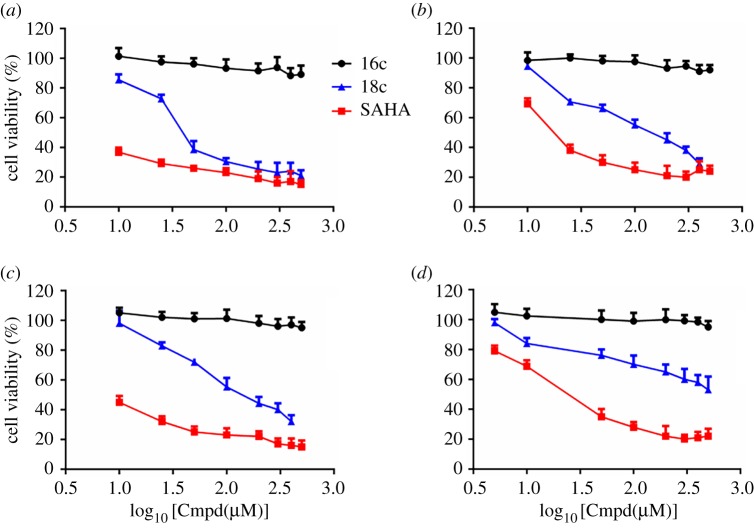

Because of the great anti-tumour potential of HDAC inhibitors, we did the antiproliferative evaluation of 18c against K562 cells, A549 cells and HepG2 cells using MTS assay as previously described [7–13]. Hydroxamic acid 18c displayed the antiproliferative activities in tested cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner within a concentration range of 10–500 µM (figure 4a–c). In K562 and A549 cells, 18c at 50–100 µM showed comparable antiproliferative activity to that of SAHA (1) at 10 µM (figure 4a) while 18c at 200 µM demonstrated comparable antiproliferative activity to that of SAHA (1) at 10 µM in HepG2 cells (figure 4b–c) (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Additionally, 16c as a negative control compound with 500 µM showed no obvious antiproliferative activities in all tested tumour cell lines (figure 4a–c), indicating the cytotoxicity of 18c was contributed by its HDAC inhibition. More importantly, like the negative control compound 16c, hydroxamic acid 18c showed less toxicity in one non-cancerous kidney cell (HEK293) than that of SAHA (1) at the same concentrations (5 µM and 10 µM, figure 4d), which demonstrated that 18c may have the therapeutic potential for targeting cancer cells but less toxicity for normal cells (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Figure 4.

The antiproliferative evaluation of 18c against K562 cells (a), A549 cells (b), HepG2 cells (c) and HEK293 (d) using MTS assay. (Cmpd: tested compound 16c, 18c or SAHA).

3. Conclusion

Using Nɛ-acetyl lysine (HDAC substrate), we raised a novel design, concerning Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives containing amide acetyl groups with the hybridization of ZBG groups as novel HDAC inhibitors. This idea is triggered by our successful design of sirtuin inhibitors mimicking Nɛ-acyl lysine [31–34]. Then, we synthesized 33 small molecules as candidates by using acetyl lysine successively hybridized with carboxylic ester or acid, hydroxamic acid, amino benzamide, thiol and heterocyclic groups as ZBG groups. After evaluation of these compounds, we found that the compounds 11 and 18b-c hybridized with hydroxamic acid demonstrated superior HDAC inhibition in comparison with all tested compounds. The best one is compound 18c, with an IC50 value of approximately 500 nM, which also can inhibit cellular HDACs (table 2 and figure 3). Most importantly, 18c in a concentration range of 50 to 200 µM showed comparable antiproliferative activity to that of SAHA (1) at 10 µM in all tested human tumour cell lines (K562, A549 and HepG2) while 18c showed less toxicity in one non-cancerous kidney cell (HEK293) than that of SAHA (1) at the same concentrations (figure 4 and electronic supplementary material, table S2). The inhibitory mechanism is possibly that the unit of amide acetyl lysine in 18c may help its recognition of HDAC and the unit of hydroxamic acid in 18c further enhances the zinc binding in the HDAC active site, and thus inhibits HDAC activity (figure 2). Eventually, this result tells us that the novel design of acetyl lysine with the hybridization of ZBG groups has opened up a new direction and could be exploited for developing more therapeutic HDAC inhibitors. The study of HDAC inhibitor 18c as a leading compound for medicinal chemistry is underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Hening Lin from Cornell University and Dr Yi Wang from Hong Kong University give us helpful suggestions during the research.

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d1t59pp [35].

Authors' contributions

F.W. carried out most synthetic and biological work, and participated in data analysis; C.W. and J.W. participated in synthetic work; Y.Z. and X.C. participated in biological work in biological work; T.L., Yan L. and Yongjun L. participated in the data analysis, discussion and proofreading; B.H. did the design and drafted the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21662010), Guiyang Municipal Science and Technology Project (grant no. [2017] 30-18/30-38), Department of Science and Technology of Guizhou Province (grant nos. [2019]2760, [2018]5779-68 and [2016]5613/5677), One hundred Talents Program of Guizhou Province (2015), the Engineering Center of Natural Science Foundation of Department of Education of Guizhou Province (Microbiology and Biochemical Pharmacy, [2015]338).

References

- 1.Bernstein BE, Tong JK, Schreiber SL. 2000. Genomewide studies of histone deacetylase function in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13 708–13 713. ( 10.1073/pnas.250477697) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Ruijter AJM, Van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. 2003. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem. J. 370, 737–749. ( 10.1042/bj20021321) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E. 2005. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene 363, 15–23. ( 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangwan R, Rajan R, Mandal PK. 2018. HDAC as onco target: reviewing the synthetic approaches with SAR study of their inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 158, 620–706. ( 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.08.073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregoretti I, Lee Y-M, Goodson HV. 2004. Molecular evolution of the histone deacetylase family: functional implications of phylogenetic analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 338, 17–31. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haigis MC, Guarente LP. 2006. Mammalian sirtuins–emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 20, 2913–2921. ( 10.1101/gad.1467506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weichert W, Roske A, Gekeler V, Beckers T, Ebert MP, Pross M, Dietel M, Denkert C, Rocken C. 2008. Association of patterns of class I histone deacetylase expression with patient prognosis in gastric cancer: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 9, 139–148. ( 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70004-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weichert W, et al. 2008. Histone deacetylases 1, 2 and 3 are highly expressed in prostate cancer and HDAC2 expression is associated with shorter PSA relapse time after radical prostatectomy. J. Cancer. 98, 604–610. ( 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudo T, et al. 2011. Histone deacetylase 1 expression in gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep. 26, 777–782. ( 10.3892/or.2011.1361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oehme I, et al. 2009. Histone deacetylase 8 in neuroblastoma tumorigenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 91–99. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0684) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West AC, Johnstone. 2014. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 30–39. ( 10.1172/JCI69738) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falkenberg KJ, Johnstone RW. 2014. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 673–691. ( 10.1038/nrd4360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Seto E. 2016. HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in cancer development and therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a026831 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a026831) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duvic M, et al. 2007. Phase 2 trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood 109, 31–39. ( 10.1182/blood-2006-06-025999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piekarz RL, et al. 2009. Phase II multi-institutional trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin as monotherapy for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 5410–5417. ( 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molife LR, de Bono JS. 2011. Belinostat: clinical applications in solid tumors and lymphoma. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 20, 1723–1732. ( 10.1517/13543784.2011.629604) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Libby EN, Becker PS, Burwick N, Green DJ, Holmberg L, Bensinger WI. 2015. Panobinostat: a review of trial results and future prospects in multiple myeloma. Expert Rev. Hematol. 8, 9–18. ( 10.1586/17474086.2015.983065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, et al. 2015. A new strategy to target acute myeloid leukemia stem and progenitor cells using chidamide, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 15, 493–503. ( 10.2174/156800961506150805153230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, et al. 2015. Trend of histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy: isoform selectivity or multitargeted strategy. Med. Res. Rev. 35, 63–84. ( 10.1002/med.21320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey RR, et al. 2002. Trifluoromethyl ketones as inhibitors of histone deacetylase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 3443–3447. ( 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00754-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiter LA, et al. 2004. Pyran-containing sulfonamide hydroxamic acids: potent MMP inhibitors that spare MMP-1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 3389–3395. ( 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.083) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farkas E, Katz Y, Bhusare S, Reich R, Röschenthaler GV, Königsmann M, Breuer E. 2004. Carbamoylphosphonate-based matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor metal complexes: solution studies and stability constants. Towards a zinc-selective binding group. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 9, 307–315. ( 10.1007/s00775-004-0524-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien EC, Farkas E, Gil MJ, Fitzgerald D, Castineras A, Nolan KB. 2000. Metal complexes of salicylhydroxamic acid (H2Sha), anthranilic hydroxamic acid and benzohydroxamic acid. Crystal and molecular structure of [Cu(phen)2(Cl)]Cl·H2Sha, a model for a peroxidase-inhibitor complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 79, 47–51. ( 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00245-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Woster PM. 2015. Discovery of a new class of histone deacetylase inhibitors with a novel zinc binding group. Medchemcomm. 6, 613–618. ( 10.1039/C4MD00401A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clawson GA. 2016. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. Ann. Transl. Med. 4, 287 ( 10.21037/atm.2016.07.22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Miyata N. 2005. Non-hydroxamate histone deacetylase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 2867–2880. ( 10.2174/092986705774454706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dancy BC, et al. 2012. Azalysine analogues as probes for protein lysine deacetylation and demethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5138–5148. ( 10.1021/ja209574z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith BC, Denu JM. 2007. Acetyl-lysine analog peptides as mechanistic probes of protein deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37 256–37 265. ( 10.1074/jbc.M707878200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Jing H, Lin H. 2014. Sirtuin inhibitors as anticancer agents. Future Med. Chem. 6, 945–966. ( 10.4155/fmc.14.44) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen B, Zang W, Wang J, Huang Y, He Y, Yan L, Liu J, Zheng W. 2015. The chemical biology of sirtuins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 5246–5264. ( 10.1039/C4CS00373J) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He B, Du J, Lin H. 2012. Thiosuccinyl peptides as Sirt5-specific inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1922–1925. ( 10.1021/ja2090417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He B, Hu J, Zhang X, Lin H. 2014. Thiomyristoyl peptides as cell-permeable Sirt6 inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 7498–7502. ( 10.1039/C4OB00860J) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jing H, et al. 2016. A SIRT2-selective inhibitor promotes c-myc oncoprotein degradation and exhibits broad anticancer activity. Cancer Cell. 29, 297–310. ( 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, et al. 2018. The mimics of N ɛ -acyl-lysine derived from cysteine as sirtuin inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 28, 2375–2378. ( 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.06.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang F, Wang C, Wang J, Zou Y, Chen X, Liu T, Li Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, He B. 2019. Data from: Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives with zinc binding groups as novel HDAC inhibitors Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.d1t59pp) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wang F, Wang C, Wang J, Zou Y, Chen X, Liu T, Li Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, He B. 2019. Data from: Nɛ-acetyl lysine derivatives with zinc binding groups as novel HDAC inhibitors Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.d1t59pp) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d1t59pp [35].