Introduction

The Earth’s 24-hour axial rotation has forced most organisms to evolve and adapt to a dramatic recurring cycle of day and night. Endogenous circadian timekeeping systems are evolution’s solution to this challenge; these timekeeping systems allow living things to recognize local environmental time and to measure time’s passage. The result is an ability to anticipate periodic daily events, to orchestrate internal temporal programs of behavioral activities and metabolic (and other physiological) functions, and to flexibly set the order and scheduling of such activities and functions to (presumably) optimize fitness in the natural world [1,2]. This system is vital to adjusting the timing and duration of bouts of rest and activity, eating, and other functions to the ecological niche. The system also lies at the core of various mechanisms for successful adaptation to the seasons [3,4]; it enables tracking the changing daylength in order to activate winter strategies to conserve energy, change coloration to avoid detection by predators, time reproductive events, and/or escape by migrating thousands of miles away (using the sun as a time-compensated compass for navigating across the latitudes). The circadian “clock” is indeed a clock for all seasons.

The Formal Language of Circadian Clocks and Rhythms

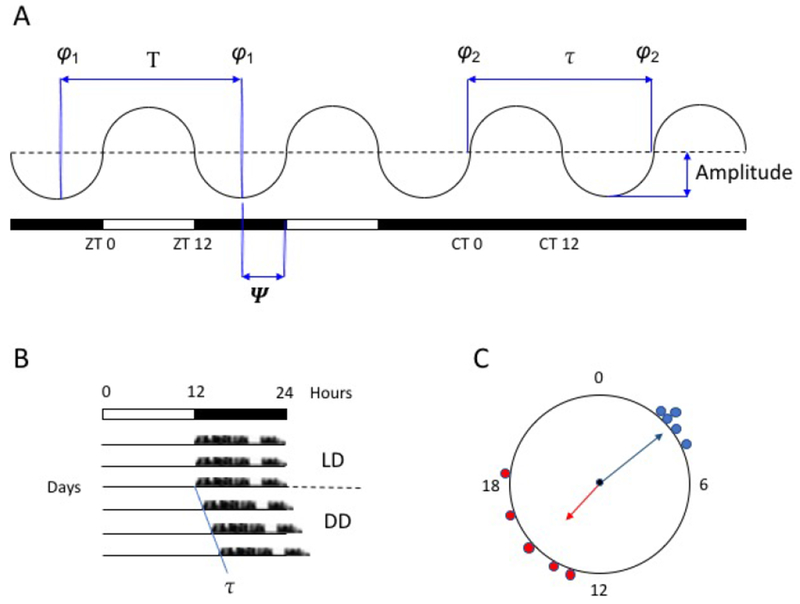

Circadian rhythms are innate, persisting with a circa-24 h oscillation in organisms and across generations in constant environmental conditions (e.g., the rhythms “free-run” in constant darkness); and accurate and precise, even in the face of changing temperatures. Like all rhythmic phenomena, their properties can be described in mathematical terms such as period, phase, and amplitude (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Terminology and Displays.

A. A schematic circadian rhythm, on the left entrained to a 12-h:12-h light:dark cycle and on the right free-running under constant darkness; white bar, light; black bar, dark. Under entrainment, zeitgeber time (zt) 0 represents the time of lights-on (dawn) and zt 12 the time of lights-off (dusk); during free-running, circadian time (ct) 0 represents “subjective” dawn and ct 12 “subjective” dusk. T = period length of the zeitgeber; τ = period length of the free-running rhythm; φ = phase, a defined, stable cycle-to-cycle reference point within the cycle of the rhythm (e.g., φ1, the minimum value); Ψ = phase angle of entrainment, the time difference (phase relationship) between a defined phase of the rhythm and an external phase-reference (e.g., zt 0).

B. A schematic circadian rhythm in “actogram” format. Data (e.g., locomotor activity) is plotted horizontally from left to right over the course of 24-h periods, with succeeding days stacked vertically from top to bottom. LD, light:dark cycle; DD, constant darkness.

C. A schematic circular plot of the phases of individual rhythms from two populations, from 0 to 24 h (or sometimes graphed from 0 to 360°). The solid radial arrow represents the mean phase of each population and its length a measure of the scatter within each population. This format for plotting angular data illustrates that a mean of 15 h for the red population is not a larger value than a mean of 3 h for the blue population, but rather a difference in their relative phases.

Circadian rhythmicity represents the overt manifestation of an internal pacemaker that functions as a “clock” through the daily resetting of its circa-24 h oscillation by environmental 24 h cues, thus adopting a stable phase relationship to the environment (i.e., entrainment). Of the possible multitude of entraining cues (“zeitgebers”), light is the most powerful and the best studied. Photic “phase response” curves rigorously quantify the resetting responses of rhythms to light pulses presented across the circadian cycle, revealing how the interaction of an endogenous oscillation with a rhythm of light responsiveness can lead to precise and accurate entrainment to the natural light:dark (day:night) cycle and shift it to a new phase (e.g., after travel across time zones). For entrainment, the clock is reset to match its intrinsic period to 24 h; light administered just before dawn will advance its rhythm, whereas exposure to an identical light stimulus (in duration, wavelength, and intensity) after dusk will delay its rhythm. So, to entrain the clock of an animal with an endogenous free-running period longer than 24 h (as is typical for humans), daily morning light acts to increase the clock’s speed and advance its phase. Importantly, a stimulus can also affect the expression of a rhythm without entraining its underlying clock; such a mechanism has been termed “masking,” because it bypasses or acts downstream of the clock and thus “masks” the clock’s true state. For example, studies of the body temperature rhythm in humans (which is significantly influenced by the circadian clock) have revealed that masking factors such as light at night, activity levels, postural changes, meal times, and sleep may significantly alter its value [5]; therefore, determining the endogenous circadian rhythm in core body temperature requires specialized conditions in which these masking factors are minimized or spread evenly over 24 hours (detailed below).

While historically the search for the clock focused on its self-sustained rhythmicity, it is the phase of entrainment (e.g., the timing of sleep onset, or temperature minimum, or locomotor activity peak in relation to the light:dark cycle) that matters for survival in the wild [6]. The clock’s free-running period and phase of entrainment are systematically related to each other, such that faster clocks (shorter period length) tend to lead to earlier phase of entrainment; but entrainment phase is also affected by other factors, including the intensity of light and prior exposure to different day lengths. Entrainment phase is sometimes referred to as “chronotype,” or the temporal phenotype of an individual or a population (as in morning “larks” and night “owls”), and has provided a window for understanding how genetic determinants and ecological constraints (including those imposed by our own urban living and societal mores) shape rhythmic behaviors [7].

A Network for Internal Time

Although daily rhythms – the opening and closing of leaves in concert with the alternation of day and night, for example – have been known since antiquity, our mechanistic understanding of daily and annual timing has blossomed over the last 50 years, now encompassing details at the molecular, cellular, tissue, organismal, and even societal levels. The basic oscillatory mechanism is intracellular, focused on a suite of “clock” genes that function within negative autoregulatory feedback loops, rhythmically repressing the transcription of their own mRNAs ([8], see Allada, this volume). Post-transcriptional and post-translational regulatory mechanisms, currently under active investigation by many researchers, also clearly contribute to fundamental rhythm properties. Notably, “clock” transcription factors do not operate solely within the clock’s feedback loops; they regulate the transcription of downstream clock-controlled genes in a wide array of the cell’s metabolic and other pathways. This linkage begins to suggest how the motion of a molecular clock can be translated into a 24-h program of biochemical events.

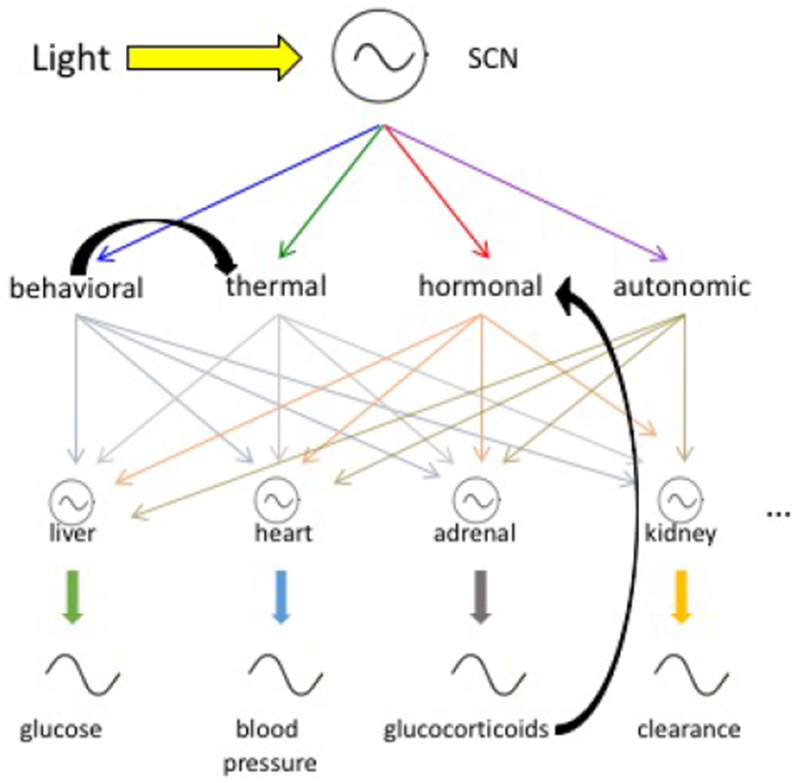

The identification of “clock” genes enabled the construction of transgenic mice bearing bioluminescent reporters (e.g., using “clock” gene promoter elements to drive rhythmic transcription of the gene encoding the enzyme luciferase), contributing to the discovery that cells, tissues, and organs throughout the brain and body express circadian oscillators [9]. In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the anterior hypothalamus (discussed below) orchestrates this network for internal time, in which the multiplicity of “peripheral” clocks exhibit defined but permutable phase relationships to each other and the environmental light:dark cycle. This coordination is mediated by the interplay of a number of coupling factors that carry the SCN’s output signals to subsidiary clocks – including rhythms of behavior (e.g., rest and activity, feeding and fasting), body temperature, hormone levels (e.g., cortisol, melatonin), and neural activity – in various combinations and strengths [10] (Figure 2). This system can insure homeostasis over time; as just one example, the hepatic clock’s proper timing of compensatory glycogenolysis and glucose export enables maintenance of plasma glucose levels through nighttime fasting [11,12]. By tuning coupling strengths and oscillator speeds, the network should be capable of adaptively re-aligning the relative phasing of its components under changing internal and external conditions. Such short-term circumstances might include food availability at an unexpected time as well as social interactions; note that during development, the phase of the hepatic clock in rat pups reverses around the time of weaning, corresponding to the switch from diurnal nursing to nocturnal feeding [13]. On the other hand, pathological misalignment – between the environment and behavior, or between behavior and the SCN, or between the SCN and peripheral clocks, or between peripheral clocks – might be both a consequence and a cause of at least some of the symptoms of aging and disease (see Zee, this volume).

Figure 2. A Network for Internal Time.

Simplified cartoon of the mammalian circadian timekeeping system, with the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) entrained by the light:dark cycle and “peripheral” body clocks entrained by SCN output signals, including rhythmic behaviors, body temperature, hormone levels, and nervous system activity; not shown are other clocks within the nervous system itself. These subsidiary clocks and rhythms also can respond to inputs downstream of the SCN (e.g., a shifted cycle of food availability on the hepatic clock). Of possible feedbacks, two exemplary ones are illustrated (i.e., locomotor activity itself affecting body temperature; adrenal output itself acting as a coupling signal).

The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) as a Mammalian Master Clock

The SCN is a bilaterally-paired hypothalamic nucleus straddling the midline, bordering the third ventricle above the optic chiasm [14]. While present in diverse species, it has been studied most intensively in rodents. Its metabolic and neuronal spike activities exhibit circadian rhythms in vivo and in vitro; in vivo, there is a close congruence between the rhythm of electrical activity and the temporal profile of behavioral rest and activity, with feedback effects of locomotion and sleep shaping the waveform of SCN firing rate [15,16]. Behavioral, physiological, and hormonal circadian rhythms depend on the integrity of the SCN; ablation of the nucleus results in circadian arrhythmicity without disrupting homeostatic mechanisms, whereas neural grafts of fetal SCN tissue re-establish behavioral rhythmicity in arrhythmic SCN-lesioned recipients, with the rhythms restored by the transplants exhibiting properties characteristic of the circadian pacemakers of the donors rather than those of the hosts [17].

Photic entrainment of SCN rhythmicity relies on a monosynaptic retinal input that primarily codes for luminance, involves signaling by glutamate and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide, and reflects the activity of a class of melanopsin-expressing, intrinsically photoreceptive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs); other ipRGCs appear to subserve light-modulatory effects on aspects of sleep and mood [18]. SCN neural outputs are mostly intra-hypothalamic but with close connections to key targets. Via the ventral sub-paraventricular zone, these include polysynaptic pathways to sleep- and wake-active cell groups, suggesting a circadian influence on both behavioral states that is time-dependent [19,20]. Note that the phases of intrinsic SCN rhythms are similar in diurnally- and nocturnally-active species, suggesting that the differing chronotypes of these species require inversion of SCN output signals or their reception [21]. Another important output is via the sympathetic system and its innervation of the pineal gland, which drives the nocturnal synthesis and secretion of melatonin. Both diurnal and nocturnal species display high melatonin levels during the night (dark phase), with its duration inversely related to the length of the day (light phase) [3,4]. Interestingly, there is also evidence implicating SCN output via diffusible substances, e.g., transforming growth factor α [22] and prokineticin 2 [23].

The circadian clock in the SCN is itself a complex coupled network of heterogeneous neuronal (and glial) oscillators [24,25]. Anatomical “modules” have been defined by neurotransmitters and other biomarkers, with functional consequences following their specific genetic manipulation: a retino-recipient region (referred to as “core”) that includes neurons expressing vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and gastrin releasing peptide; an arginine vasopressin neuronal “shell;” and other identified cell groups that overlap these subdivisions (e.g., expressing neuromedin S or D1 dopamine receptor). Somehow these anatomical units are dynamically coupled to yield emergent properties of the SCN clock that are critical to its function. Circuit-level mechanisms enable clock precision (generation of a stable ensemble period from sloppy cellular oscillations), robustness (persistence in the face of genetic perturbations), and plasticity (cellular phase dispersion in response to changing daylength). One such mechanism involves the interaction of SCN molecular and electrical activities. The intracellular molecular clock governs electrical activity through an array of ion channels that switch resting membrane potential from daytime depolarization to nighttime hyperpolarization and sustain the level of neuronal firing; in turn, electrical activity regulates calcium-dependent transcription and thus the phase and amplitude of the molecular clock. Under investigation are additional mechanisms (e.g., state-dependent actions of VIP and GABA, small world network topology) to account for the complex spatio-temporal activity patterns exhibited by SCN tissue.

On Sleep and Wakefulness

The most obvious circadian-regulated output is sleep and wake timing. Sleep is a complex multisite and multi-function behavior. Overtly, it involves changes in consciousness, responsiveness, and posture. Within the organism, it causes changes in all physiological systems. Unlike coma and anesthesia, sleep is unique in its ability to, without external pharmacological manipulation, rapidly and reversibly change to a fully functioning wake state [26]. Considerable progress is being made in elucidating the neural circuitry underlying the regulation of sleep:wake states and their transitions [27,28].

Sleep is required for normal physiology; death occurs if there is long-term sleep deprivation [29]. The multiple changes that occur during sleep are important for the entire body, not just for the brain. Surprisingly, “the” function of sleep is unknown. As Dr. Alan Rechtschaffen famously said: “If sleep doesn’t serve an absolutely vital function, it is the greatest mistake evolution ever made.” During the time animals sleep, they are not procreating, feeding, or defending themselves – three important behaviors for sustaining the species. Therefore, the fact that sleep or sleep-like behavior has persisted in every animal species suggests that it is required for normal physiological functioning. There are probably multiple functions “of’ – or more properly “that occur during” – sleep, suggesting that sleep is the platform during which multiple physiological processes occur. Sleep is not just required for feeling “rested”; metabolic, immunologic, learning and other physiological work occurs during sleep. Each of these physiological processes probably has its own time course of build-up and decay, so “enough” sleep for one function may be different than for another. Therefore, “completing” these functions would be expected to be part of the regulation of timing or duration of sleep. Indeed, even sleep is not uniform; it is composed of non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, which are differentially regulated (discussed below). More studies are needed to determine the time course of buildup and decay of each of these processes, since the timing and duration of sleep would also be expected to be regulated to increase the chance of survival.

Circadian and Homeostatic Regulation of Sleep Timing and Content

The Two Process Model [30] is the dominant framework for understanding the timing and content of sleep behavior at the level of the whole organism and specific brain areas. The two processes are circadian rhythmicity (Process C) and sleep homeostasis (Process S). Sleep homeostasis increases during wake (and possibly REM sleep) and decreases during sleep (or possibly just NREM sleep). Accepted markers of sleep homeostasis across one or two sleep and wake episodes (e.g., wake episodes lasting 4-60 hours and daytime and/or nighttime sleep episodes) are Slow Wave Sleep (SWS, N3 under current AASM criteria) or Slow Wave Activity (SWA, ~0.5-4.5 Hz) during sleep and/or ~12.25-25.0 Hz waves [31] during wake in the EEG; the putative biochemical agent is adenosine. All these markers have levels that increase with wake duration and decrease during sleep. Consistent with this is the fact that caffeine, an adenosine receptor antagonist, decreases “sleepiness”. The buildup and decay of Process S are modeled mathematically as saturating exponentials – consistent with data that lost sleep is not recovered minute-by-minute and therefore an intensity factor (e.g., increased SWA) must be involved. For a longer time course of sleep homeostasis, as seen with chronic sleep restriction (i.e., multiple nights with insufficient sleep), SWS or SWA are not appropriate markers and the time course of buildup and recovery is different than for sleep deprivation (i.e., one continuous wake episode) [32]; one hypothesized biochemical change is in adenosine receptor concentrations [33].

Protocols for Separating Circadian and Sleep:Wake Influences

A difficulty in determining the relative effect of circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostatic factors is that circadian timing (phase) and sleep homeostatic buildup and decay covary: on a 24-h schedule with sleep at night and wake during the day, both circadian phase and the length of time awake (during which sleep homeostasis increases) or asleep (during which sleep homeostasis decreases) advance at the same rate. For example, suppose we set circadian time 0 as 5 am, wake time at 7 am, and sleep onset time at 11 pm. Then wake time will be at circadian time 2; 5 hours after wake time will be circadian time 7; and sleep onset time (after 16 hours awake) will be circadian time 18. We can never learn what happens when circadian time is 18 but wake duration is 2 hours, such as might happen with someone working the night shift or experiencing jet lag. An additional difficulty in determining circadian phase or sleep:wake influence on a variable is that sleep and wake are associated with multiple other differences besides the sleep or wake state; these include differences in physical and mental activity levels, fasting/feeding, social interactions, lighting conditions, and posture. Therefore, sleep or wake per se may not be the only determining factor.

For these reasons, several types of protocols have been developed to separate the circadian and homeostatic influences on sleep:wake physiology. In two of these protocols, subjects are not allowed to choose their sleep and wake times, change lighting conditions (which are usually very dim to minimize alerting and phase-shifting effects of light), or know clock time. One protocol is the “constant routine” in which the subjects remain awake for 40 hours or longer in constant posture and dim light conditions and eat multiple small meals; this enables study of wake at all circadian phases and especially at two different sleep homeostatic pressures (24 hours apart) for each circadian phase and under conditions in which masking (defined above) is minimized or distributed equally across all circadian phases. This protocol, however, induces sleep deprivation; it, therefore, is of great use for studying hormones, performance, cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, and other physiological functions but of limited use for studying the independent effects of circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostasis on sleep. The other protocol is a “forced desynchrony” protocol in which subjects live on non-24 h “days”. Studies have been conducted with “days” as short as 90 minutes [34] and as long as 42.85 hours [32]. Within each of these “days”, there is usually a 2:1 wake:sleep (and light:dark) ratio, though other ratios can be used if chronic sleep restriction is being studied [35]. Under such schedules, the circadian pacemaker cannot entrain to the wake:sleep or light:dark cycle, leading to desynchrony between circadian and sleep homeostatic processes. These forced desynchrony protocols create multiple evenly-distributed combinations of length of time awake or asleep at each circadian phase, so that separate effects of circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostasis can be studied. Such intensive inpatient studies have documented the findings described below about the relative circadian and homeostatic influences on sleep timing and duration.

A third protocol in which individuals sometimes exhibit spontaneous desynchrony between circadian and sleep:wake cycles occurs when they are allowed to self-select their wake:sleep and light:dark schedules [36]. Under these conditions, the observed cycle length is usually longer than the endogenous circadian pacemaker’s period of ~24.2 h [37], and there is no longer the opportunity to study all possible timing combinations of circadian and homeostatic factors. The observed circadian period is also ~25 h instead of ~24.2 h; this apparent discrepancy can be explained by the non-uniform (across the day) light exposure [38], such that there is more light exposure during the circadian phases that cause phase delays. Nevertheless, spontaneous desynchrony protocols have also yielded much useful information on the effects of circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostasis on sleep [39].

Effects of Self-selected Behaviors on Circadian Rhythms and Sleep

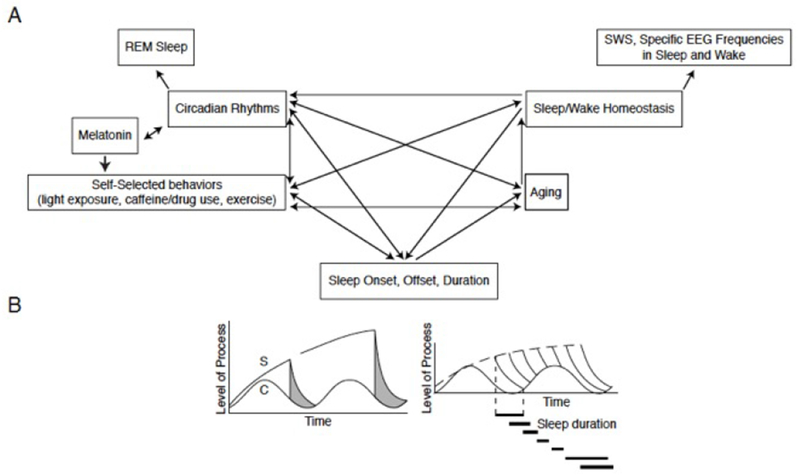

There are also direct and indirect effects of behaviors that may affect both circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostasis (Figure 3). Light during the normal dark times can induce sleep in rodents, and dark during the normal light times can induce wake. In addition, as described above, self-selected light:dark timing may affect alertness and circadian rhythms, which then affect timing of sleep (which occurs in the dark). Notably, self-selected light:dark timing differentially affects early “lark” vs late “owl” chronotypes and their circadian phase. When larks and owls can choose their own lighting schedules, circadian phase is later in owls than larks; but when all are exposed to the same light:dark schedule, circadian phase is approximately the same in all [40]. Caffeine can directly affect the circadian system [41] as well as to increase alertness, which then includes increased light that can directly affect the circadian clock.

Figure 3. The Regulation of Sleep and Wake.

A. Inter-relationships of factors affecting multiple aspects of sleep and wake.

B. Diagrams of changes in time of (left) Two-Process Model of sleep regulation. S=Process S, the sleep homeostatic factor; C=Process C, the circadian rhythm process; Grey areas=time of sleep. When an individual self-selects their sleep onset (one of the two vertical lines), the level of homeostatic drive is at the Process S level (upper line); homeostatic drive then declines in an exponential manner until it reaches the Process C level. Then the person awakens and the level of homeostatic drive begins to rise again (which is not shown). (Right) Sleep durations associated with different self-selected sleep onsets.

Self-selected light:dark schedules may be involved in some circadian rhythm sleep disorders. For example, individuals who do not choose regular light:dark schedules or live mostly under indoor dim light conditions, blind people, or individuals with relatively long endogenous periods who stay up late at night or for long durations (possibly because of endogenous- or pharmaceutically-induced low sleep homeostatic pressure buildup rate) and have light exposure that promotes circadian delays may develop Non-24-Hr Sleep-Wake Disorder (see Abbott, this volume). Or, individuals with reduced light sensitivity or preferential late night light exposure may develop Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome (Wyatt & Culnan, this volume). Reduced rate of rise of sleep homeostatic pressure (as has been postulated to occur with aging) would affect the relative amplitudes of circadian and homeostatic influences on sleep timing, and, together with a relative circadian phase advance, may be a reason for early morning awakening complaints of many older people.

Markers of Circadian Rhythms in Humans

Circadian rhythms generated by the SCN heavily influence the timing of sleep onset and offset and of the timing of REM sleep within a sleep episode. The SCN’s tight regulation of melatonin rhythmicity (discussed above) makes melatonin a valuable marker of circadian timing if melatonin is collected under dim light conditions, since ocular light exposure suppresses melatonin. Another marker of circadian timing and amplitude is core body temperature (CBT); however, given the circadian-phase-dependent masking effects of sleep/wake and activity on CBT, it cannot be used as a marker of circadian phase and amplitude except under highly controlled inpatient conditions. Melatonin (usually Dim Light Melatonin Onset, DLMO) and CBT (usually minimum of fit sinusoidal curve) markers are tightly linked in both phase (i.e., DLMO occurring ~6 hours before CBTmin [49]) and amplitude [37,50,51]. Unexpectedly, even though melatonin levels are high when individuals are usually tired, it is not effective as a hypnotic [42] when taken for insomnia and/or at an individual’s habitual sleep time. On the other hand, melatonin or its agonists can phase shift the circadian pacemaker of sighted and blind people [43,44] and through that mechanism affect sleep. That sleep itself can modulate pacemaker function has already been noted [16]; sleep restriction can also decrease the effectiveness of phase-shifting light stimuli [45], an interaction that may be important for some circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

Circadian and Homeostatic Effects on Sleep

Paradoxically, in humans, the circadian drive for sleep is strongest near the end of the habitual sleep episode, perhaps to consolidate sleep as the homeostatic drive decreases during the sleep episode; while the circadian drive for wake is strongest a few hours before habitual wake during the “wake maintenance zone,” perhaps to consolidate wake as sleep homeostatic drive builds up over an ~16 hour wake episode [46]. REM sleep is most likely to occur during the end of the habitual sleep episode, both because that is the time the circadian drive promotes REM sleep and because the NREM-REM sleep “competition” across the night has decreased NREM sleep pressure as sleep homeostasis declines.

The timing and content of sleep, including sleep latency and wake within a sleep episode, are regulated by a non-linear interaction between these circadian and sleep homeostatic processes: the magnitude of the circadian influence depends on how long an individual has been awake or asleep. When a person has just awoken, there is little circadian variation in sleep latency; similarly, when a person has just fallen asleep, there is little circadian variation in wake within a sleep episode. However, if the person has been awake for a long time, then sleep latency depends on circadian phase (large amplitude circadian influence); and if the person has been asleep for a long time, then the amount of wake within the sleep episode depends on circadian phase. Therefore, when sleep homeostasis and circadian phase are aligned, there is relatively short sleep latency and consolidated sleep without significant wake within the sleep episodes [46], The two, however, are misaligned in jet lag and shift work; during these conditions, the circadian system is promoting sleep when the individual desires to be awake and promoting wake when the individual desires to be asleep. The non-linear combination of sleep homeostasis and circadian phase also affects some EEG frequencies [47] and cortical and subcortical activity in the brain as measured by fMRI [48].

Coda

Circadian neurobiology and sleep-wake regulation affect virtually all physiological systems including each other. Self-selected behaviors may also affect these processes, leading to cycles that may cause (e.g., jet lag, shift-work, and/or other circadian rhythm sleep disorders) or worsen (e.g., metabolic, immune, cognitive) diseases or disorders. Understanding the underlying physiology is crucial for developing and testing appropriate education, pharmaceutical and other interventions to lessen these adverse consequences.

KEY POINTS.

Precise, robust, and flexible circadian rhythmicity is the product of a network of tissue and organ clocks, including a master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus.

The timing, duration, and content of sleep are regulated by non-linear interactions between circadian and sleep homeostatic processes and the environmental and behavioral variables that affect them.

Changes in the time course, strength, or alignment of circadian and homeostatic drives, either environmentally or pathologically, can begin to account for disordered sleep rhythms and suggest rational therapeutic approaches.

SYNOPSIS.

Endogenous central and peripheral circadian oscillators are key to organizing multiple aspects of mammalian physiology; this “clock” tracks the day:night cycle and governs behavioral and physiological rhythmicity. Flexibility in the timing and duration of sleep and wakefulness, critical to the survival of species, is the result of a complex, dynamic interaction between two regulatory processes: the clock and a homeostatic drive that increases with wake duration and decreases during sleep. When circadian rhythmicity and sleep homeostasis are misaligned – as in shifted schedules or time zone transitions, aging, or disease – sleep, metabolic, and other disorders may ensue.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health NIH K24-HL105664, NIA P01-AG009975, R01-HL128538, R01-GM-105018, and NICHD R21-HD086392. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have nothing to disclose

Contributor Information

William J. Schwartz, Depts. of Neurology (Dell Medical School) & Integrative Biology (College of Natural Sciences), The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Elizabeth B. Klerman, Dept. of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital & Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, DeCoursey PJ (eds). Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2009, 382 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roenneberg T, Merrow M. The circadian clock and human health. Curr Biol 2016;26:R432–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul MJ, Zucker I, Schwartz WJ. Tracking the seasons: the internal calendars of animals. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2008;363:341–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood S, Loudon A. Clocks for all seasons: unwinding the roles and mechanisms of circadian and interval timers in the hypothalamus and pituitary. J Endocrinol 2014;222:R39–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wever RA. Internal interactions within the human circadian system: the masking effect. Experientia 1985;41:332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helm B, Visser ME, Schwartz WJ, et al. Two sides of a coin: ecological and chronobiological perspectives of timing in the wild. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017;372:20160246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythms 2003;18:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genetics 2017;18:164–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci 2012;35:445–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schibler U, Gotic I, Saini C, et al. Clock-talk: interactions between central and peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2015;80:223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamia KA, Storch K-F, Weitz CJ. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:15172–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qian J, Scheer FAJL. Circadian system and glucose metabolism: implications for physiology and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2016;27:282–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamazaki S, Yoshikawa T, Biscoe EW, et al. Ontogeny of circadian organization in the rat. J Biol Rhythms 2009;24:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver DR. The suprachiasmatic nucleus: a 25-year retrospective. J Biol Rhythms 1998;13:100–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houben T, Coomans CP, Meijer JH. Regulation of circadian and acute activity levels by the murine suprachiasmatic nuclei. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e110172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deboer T, Vansteensel MJ, Détári L, et al. Sleep states alter activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci 2003;6:1086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralph MR, Foster RG, Davis FC, et al. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science 1990;247:975–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014;15:443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mistlberger RE. Circadian regulation of sleep in mammals: role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Rev 2005;49:429–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saper CB, Scammell TE, Lu J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 2005;437:1257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smale L, Lee T, Nunez AA. Mammalian diurnality: some facts and gaps. J Biol Rhythms 2003;18:356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer A, Yang FC, Snodgrass P, et al. Regulation of daily locomotor activity and sleep by hypothalamic EGF receptor signaling. Science 2001;294:2511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou QY, Cheng MY. Prokineticin 2 and circadian clock output. FEBS J 2005;272:5703–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, Kay SA. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Annu Rev Physiol 2010;72:551–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hastings MH, Maywood ES, Brancaccio M. Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018;19:453–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown EN, Lydic R, Schiff ND. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. New Engl J Med 2010;363:2638–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saper CB, Fuller PM, Wake-sleep circuitry: an overview. Curr Opinion Neurobiol 2017;44:186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scammell TE, Arrigoni, Lipton JO. Neural circuitry of wakefulness and sleep. Neuron 2017;93:747–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everson CA. Functional consequences of sustained sleep deprivation in the rat. Behav Brain Res 1995;69:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borbély AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Human Neurobiol 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aeschbach D, Matthews JR, Postolache TT, et al. Dynamics of the human EEG during prolonged wakefulness: Evidence for frequency-specific circadian and homeostatic influences. Neurosci Lett 1997;239:121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen DA, Wang W, Wyatt JK, et al. Uncovering residual effects of chronic sleep loss on human performance. Science Translational Medicine 2010;2:14ra13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips AJK, Klerman EB, Butler JP. Modeling the adenosine system as a modulator of cognitive performance and sleep patterns during sleep restriction and recovery. PLoS Computational Biology 2017;12:e1005759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Sleep studies on a 90-minute day. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol 1975;39:145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McHill AW, Hull JT, Wang W, et al. Chronic sleep curtailment, even without extended (>16 h) wakefulness, degrades human vigilance performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:6070–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wever RA. The Circadian System of Man: Results of Experiments Under Temporal Isolation. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1979, 276 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duffy JF, Cain SW, Chang AM, et al. Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2011;108:15602–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klerman EB, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, et al. Simulations of light effects on the human circadian pacemaker: implications for assessment of intrinsic period. Am J Physiol 1996;270:R271–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strogatz SH, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Circadian regulation dominates homeostatic control of sleep length and prior wake length in humans. Sleep 1986;9:353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright KP Jr, McHill AW, Birks BR, et al. Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Curr Biol 2013;23:1554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burke TM, Markwald RR, McHill AW, et al. Effects of caffeine on the human circadian clock in vivo and in vitro. Science Translational Medicine 2015;7:305ra146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017;13:307–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajaratnam SM, Polymeropoulos MH, Fisher DM, et al. Melatonin agonist tasimelteon (VEC162) for transient insomnia after sleep-time shift: two randomised controlled multicenter trials. Lancet 2008;373:482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lockley SW, Skene DJ, James K, et al. (2000) Melatonin administration can entrain the free running circadian system of blind subjects. J Endocrinol 2000;164:R1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgess HJ. Partial sleep deprivation reduces phase advances to light in humans. J Biol Rhythms 2010;25:460–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Paradoxical timing of the circadian rhythm of sleep propensity serves to consolidate sleep and wakefulness in humans. Neurosci Lett 1994;166:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J Neurosci 1995;15:3526–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muto V, Jaspar M, Meyer C, et al. Local modulation of human brain responses by circadian rhythmicity and sleep debt. Science 2016;353:687–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahl K, Avery DH, Lewy AJ, et al. Dim light melatonin onset and circadian temperature during a constant routine in hypersomnia winter depression. Acta Psychiat Scand 1993;88:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shanahan TL, Czeisler CA. Light exposure induces equivalent phase shifts of the endogenous circadian rhythms of circulating plasma melatonin and core body temperature in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;73:227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanahan TL, Kronauer RE, Duffy JF, et al. Melatonin rhythms observed throughout a three-cycle bright-light stimulus designed to reset the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms 1999;14:237–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]