Abstract

Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) have emerged as powerful tools for delivering bioactive cargoes, such as biosensors or drugs to intact cells. One limitation of CPPs is their rapid degradation by intracellular proteases. β-hairpin “protectides” have previously been demonstrated to be long-lived under cytosolic conditions due to their secondary structure. The goal of this work was to demonstrate that arginine-rich β-hairpin peptides function as both protectides and as CPPs. Peptides exhibiting a β-hairpin motif were found to be rapidly internalized into cells with their uptake efficiency dependent on the number of arginine residues in the sequence. Cellular internalization of the β-hairpin peptides was compared to unstructured, scrambled sequences and to commercially available, arginine-rich CPPs. The unstructured peptides displayed greater uptake kinetics compared to the structured β-hairpin sequences; however, intracellular stability studies revealed that the β-hairpin peptides exhibited superior stability under cytosolic conditions with a 16-fold increase in peptide half-life. This study identifies a new class of long-lived CPPs that can overcome the stability limitations of peptide-based reporters or bioactive delivery mechanisms in intact cells.

Keywords: β-hairpin, cell penetrating peptide, protectide

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) have emerged as powerful tools for delivering bioactive cargoes into the cytosol of intact cells for therapeutic and sensing purposes. These short, charged sequences can be incorporated into biomaterials, antimicrobial drugs, anticancer therapeutics, small molecule inhibitors, intracellular probes, and more.[1–3] In recent years, several new types of CPPs have been identified with a range of primary and secondary structures in an attempt to increase cellular uptake and intracellular targeting of biomolecules.[4] The need for incorporating CPPs into biosensors has increased in recent years due to novel single cell analysis techniques.[5] These high-throughput screening approaches have relied on electroporation and microinjection to introduce peptide-based reporters into single intact cells.[3] In addition to peptide-based reporters, CPPs have found an important role in the development of novel therapeutics compounds called PROTACs (proteolysis targeting chimeras). These peptides take advantage of the naturally occurring ubiquitination machinery inside of the cells to target “undruggable” proteins such as FKBP12, ErbB3, and the tau protein to the proteasome for degradation.[6] Many of the early PROTAC sequences incorporated CPPs to facilitate the uptake of the peptides into the cells to allow for the targeted degradation of specific proteins; however, these PROTACs suffered from high protease susceptibility and low cell permeability which decreased their overall utility as new therapeutic compounds.[7] Despite the vast potential of CPPs, one significant limitation is the rapid degradation by extracellular and intracellular enzymes[7–9] resulting in a time-dependent decrease in biomolecule concentration at the active site which can lead to decreased efficacy for CPP-tagged drugs or poor analytical signals for CPP-tagged biosensors.[8] Thus, there is a need to design novel CPPs with sufficient uptake efficiency coupled with enhanced resistance to protease-mediated degradation. A recent review by Kristensen and co-workers[8] identified this need and highlighted current approaches to increase the lifetime of CPP-tagged peptides under cytosolic conditions. Strategies for developing protease-resistant CPPs include incorporating D-amino acids,[10] introducing nonnatural groups like β-amino acids or N-methylated amino acids,[11,12] or modifying peptide backbone by macrocyclization.[9,13,14] One challenge associated with these strategies is that in an effort to increase peptide stability, uptake efficiency is compromised. Hence, there exists a tradeoff between peptide internalization efficiency and enhanced intracellular stability.[8,15]

While several different cyclic CPPs have been developed[9,14,16], one area that has not been studied is developing CPPs with a pronounced secondary structure designed to impair degradation by intra-cellular peptidases. Prior work has identified the utility of “protectides,” peptide sequences exhibiting a β-hairpin secondary structure that are resistant to degradation by peptidases and proteases.[17,18] Unstructured peptides gain entry to the catalytic cleft of peptidases and are degraded on the order of seconds to minutes,[19] while structured peptides like β-hairpins cannot enter the catalytic site and thus remain intact for several hours.[17,18] These protectides have the ability to confer this stability to unstructured peptide substrates via conjugation at the N-terminus, resulting in highly stable biosensors.[17,20] A sequence first identified by Cline and co-workers, WKWK (Ac-RWVKVpGOWIKQ-NH2)[17,18] consisted of several positively charged amino acid residues (lysine, arginine, and ornithine) as positions 1, 4, 8, and 11 coupled with a d-Pro-Gly β-turn to establish the secondary structure which increases intracellular stability. Coupling arginine- and proline-rich sequences for the generation of structured CPPs with enhanced intracellular stability has also been explained by Daniels and Schepartz.[15] Recent work by Houston and co-workers found that replacing the lysine residues with ornithine or arginine further increased intracellular stability and also converted the β-hairpin sequence into a primary degron capable of intracellular ubiquitination.[21] The goal of this work is to determine if these β-hairpin protectides, which are rich in positively charged residues, could also function as CPPs. To accomplish this, a library of β-hairpin protectides was synthesized based on the WKWK sequence with arginine and ornithine amino acid substitutions at positions 1, 4, and 11. The effect of time, temperature, and concentration on peptide uptake was determined and compared to the internalization efficiencies of unstructured, scrambled versions of the same sequences as well as well-known CPPs, TAT, and nona-arginine (ARG). Peptide uptake was quantified in intact cells using fluorometry and fluorescent microscopy. The intracellular stability of peptides was tested using a degradation assay in cell lysates. The results confirmed that the β-hairpin protectides behaved as CPPs with rapid cellular uptake in intact cells and demonstrated superior intracellular stability compared to unstructured counterparts.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Chemicals

Fmoc-protected amino acids, 2-(6-Chloro-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,−1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and rink amide SS resin were purchased from Advanced ChemTech, Louisville, Kentucky. Nα-Fmoc-Nδ-allyloxycarbonyl-l-ornithine (Fmoc-Orn[Aloc]-OH) was purchased from Chem-Impex International, Inc, Wood Dale, Illinois. 1-Hydroxy-6-(trifluoromethyl)benzotriazole (HOBt) and (Ethyl cyano[hydroxyimino]acetato)-tri-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-phosphonium (PyBOP) were purchased from Novabiochem, Billerica, Massachusetts. Dimethylformamide (DMF) was purchased from Protein Technologies, Tucson, Arizona. Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), triisopropylsilane (TIPS), tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) (palladium), 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (FAM), chloroform (CHCl3), methanol (MeOH), dichloromethane (DCM), and N-methylmorpholine (NMM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri. Glacial acetic acid was purchased from Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, Massachusetts. Acetic anhydride was purchased from Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, New Jersey.

2.2 |. Peptide synthesis and purification

All peptides were synthesized on a Tribute peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Tucson, Arizona) using a standard Fmoc peptide chemistry protocol on a 100 μmol scale using rink amide resin (189 mg, 0.53 mmol/g). Fivefold excess of Fmoc-amino acids (Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Val-OH, Fmoc-Orn-OH, Fmoc-d-Pro-OH, Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-Ile-OH, Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Orn(Aloc)-OH), and HCTU) in the presence of 10 equivalents of NMM were used for each of the amino acid coupling steps (10 minutes) with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as the solvent. A solution of acetic anhydride, NMM, and NMP (1:1:3) was added to the deprotected resin and shaken for 30 minutes to acetylate the N-terminus of the peptide. Once the peptide synthesis was complete, the resin was washed with DMF (3 × 30 seconds) then DCM (3 × 30 seconds). The Aloc group was removed with 3-fold excess of palladium in 4 mL of CHCl3-HOAc-NMM (37:2:1) under nitrogen for 2 hours. The resin was then washed with DCM (3 × 30 seconds) followed by DMF (3 × 30 seconds). In the dark, FAM was coupled to the delta nitrogen of the ornithine side chain with 4-fold excess of FAM, HOBt, PyBOP, and DIEA in 3 mL DMF for 24 hours and then repeated for 8 hours. The peptide resin was washed with DMF (3 × 30 seconds) and DCM (3 × 30 seconds). The peptide was cleaved from the resin and side-chain deprotected using TFA/water/TIPS (4 mL, 95:2.5:2.5) for 3 hours and collected in a 50-mL centrifuge tube. The cleavage reaction was repeated for 10 minutes. The cleavage solutions for the peptide were combined and concentrated in vacuo. Cold diethyl ether was then added to the peptide solution to precipitate the crude peptide. The peptide was centrifuged for 10 minutes (4000 rpm) and the ether layer decanted. Fresh cold diethyl ether was added, and the pelleted peptide was resuspended. The peptide was centrifuged again, and the procedure was repeated 5 times in total. After the final ether wash, the peptide pellet was dissolved in 5 mL water containing 0.1% TFA, frozen and lyophilized.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was performed with a Waters 616 pump, Waters 2707 Autosampler, and 996 Photodiode Assay Detector which are controlled by Waters (Massachusetts, US) Empower 2 software. The separation was performed on an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) Zorbax 300SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with an Agilent guard column Zorbax 300SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 12.5 mm). Elution was done with a linear 5%−55% gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in water) over 50 minutes at a 1 mL/min flow rate with UV detection at 442 nm. Preparative HPLC runs were performed with a Waters prep LC Controller, Waters Sample Injector, and 2489 UV/Visible Detector which are controlled by Waters (Massachusetts, US) Empower 2 software. The separation was performed on an Agilent Zorbax 300SBC18 PrepHT column (7 μm, 21.2 × 250 mm) with Zorbax 300SB-C18 PrepHT guard column (7 μm, 21.2 × 10 mm) using a linear 5%−55% gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in water) over 50 minutes at a 20 mL/min flow rate with UV detection at 215 nm. Fractions of high (>95%) HPLC purity of each peptide and with the expected mass were combined and lyophilized. Representative data for the HPLC purification and mass spectrometry validation of the RWRWR peptide (Supporting Information Figure S1) and the SRWRWR (Supporting Information Figure S2) are included in the Supporting Information.

2.3 |. Cell culture and lysate generation

HeLa cells (LSU AgCenter Tissue Culture Facility) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS, Seradigm). OPM-2 cells (a kind gift from Nancy Allbritton, UNC) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 12% FBS, 21.8 mM glucose, 8.6 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate. THP-1 cells (a kind gift from Nancy Allbritton, UNC) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% v/v FBS and0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. K562 cells (a kind gift from Nancy Allbritton, UNC) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% v/v FBS. U937 cells (LSU AgCenter Tissue Culture Facility) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% v/v FBS. All media components were from Corning (Atlanta, GA, USA) unless otherwise noted HeLa lysates were generated by harvesting 1 × 106 cells/mL, followed by washing 2× and pelleting in phosphate buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 27 mM KCL, and 1.75 mM KH2PO4 at pH 7.4). The cell pellet was resuspended in an approximately equivalent volume of mammalian protein extraction reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to the volume of the cell pellet (~1000–2000 μL) then vortexed for 10 minutes at room temperature. Following this, the mixture was centrifuged at 14 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant transferred to a centrifuge tube and stored on ice until use. Total protein concentration was determined using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI, USA).

2.4 |. Quantification of peptide cell permeability

The quantification of peptide uptake was performed using a protocol previously developed by Qian and co-workers[16] to evaluate peptide permeability efficiency in a time-, concentration-, and temperature-dependent manner. Prior to experimentation, all peptides were reconstituted in sodium phosphate buffer (2.26 mM NaH2PO4 H2O and 8.43 mM Na2H PO4 7H2O). Stock peptide concentration was determined using a Nano-Drop (Thermo Scientific) at the wavelength of 492 nm using the UV-vis function. Three days prior to the experiment, HeLa cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/mL in 12-well plates (Corning). On the day of experiment, peptides were diluted to the desired final concentrations in extracellular buffer (ECB; 5.036 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 136.89 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 2.066 mM MgCl2 6H2O, 1.8 mM CaCl2 2H2O, and 5.55 mM glucose). The cells were washed 2× with ECB (1 mL/well) followed by the addition of the peptide solutions (500 μL/well) for indicated time points at the indicated temperatures. All plates were wrapped in aluminum foil to avoid deactivating the FAM tag on the peptide. Following the incubation time, the peptide solution was removed, and the cells were washed 2× with ECB. The cells were trypsinized (200 μL/well) for 10 minutes at room temperature to detach the cells from the wells and remove any remaining peptide adhered to the extracellular surface. The cells were then resuspended in ECB (1 mL/well), thoroughly mixed, and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes. The samples were centrifuged (1800 rcf, 2.5 minutes, at room temperature) to isolate the cells. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was lysed with 0.1 M NaOH (250 μL/tube). While the fluorescent intensity of FAM has been demonstrated to be dependent on pH, it was confirmed that the 0.1 M NaOH had negligible effects on the intensity profile of RWRWR, OWRWR, and S-OWRWR peptides at both 10 and 30 μM concentrations (Supporting Information Figure S3).

Each sample was then transferred to a 96-well plate and quantified by fluorometry (Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA) Wallac 1420 VICTOR2 multilabel HTS counter). The FAM tag was quantified using an excitation filter of 490 nm and an emission filter of 535 nm. During every experiment, a no peptide control was performed (eg, cells incubated with ECB only). To measure the background signal of each peptide, the peptide solutions used in each experiment was analyzed by fluorometry to normalize the observed fluorescent signal for each sample. All experimentation conditions were performed in triplicate with every experiment performed twice to ensure reproducibility. The fluorescent signal measured by the plate reader was normalized using Equation (1):

| (1) |

where F denotes the fluorescent signal of cells incubated with peptide, C denotes the fluorescent signal of cells incubated with no peptide, P denotes the average fluorescent signal of the peptide in suspension, and B denotes the average fluorescent signal of the ECB. This analysis was performed to allow for a comparison between the different peptides used in this study. Data reported for each peptide are the average of triplicate samples. Standard deviations were calculated based on the triplicate samples to obtain the error bars and perform analysis of variance. Each experiment was repeated twice to confirm the results.

Statistical analysis of uptake was performed using ANOVA F-statistics with SAS software. The III-67B peptide, a sequence determined to be impermeable to intact cells, was used as negative control. To determine the statistical significance of the permeability efficiency of each peptide, the normalized signals obtained from that peptide were assessed by statistical t-tests compared the negative control. For the time-dependent studies, 10 μM peptide was incubated with HeLa cells for at 10-minute intervals between 10 and 100 minutes at 37°C. For the peptides that demonstrated insignificant time-dependence (rapid internalization; RWRWR, OWRWR, RWOWR, TAT, and ARG) comparison against the negative control was carried out based on the 20-minute time point. For the peptides demonstrating time-dependence (slow internalization), namely OWOWO and WKWK, this analysis was performed based on the 100-minute time point. For the temperature-dependent studies, 10 μM peptide solution was incubated with HeLa cells for 60 minutes at 3 different temperature (37, 25, and 4°C). For the concentration-dependent studies, 4 different concentrations of peptide (5, 10, 20, and 30 μM) solution were incubated with HeLa cells at 37°C for 60 minutes. ANOVA F-statistics were performed to assess the statistical significance of the effect of incubation time, incubation temperature, and peptide concentration on the normalized fluorometry signals.

2.5 |. Circular dichroism

Peptide concentrations were determined based on the absorbance of FAM at 492 nm. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy data were collected using a J-815 CD spectrometer (JASCO, Easton, MD, USA). Spectra were generated at 25°C with a wavelength scan (260–185 nm) using 50 nm/min scanning speed in a 0.1 cm cell. Data pitch and accumulation were 1 and 3 nm, respectively. Scan mode was continuous. The smoothing method was Savitzky-Golay with a convolution width of 7. All peptides were at a final concentration of 40 μM in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.02).

2.6 |. Peptide degradation studies

Peptide stability was determined using a modified version of a degradation assay previously described by Cline and co-workers.[18,22] Briefly, 30 μM peptide solution was incubated in HeLa lysates diluted to a total protein concentration of 2 mg/mL in an assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) at 37°C in the dark. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed at set intervals, at which point further peptidase activity was quenched by heating the aliquots at 90°C for 5 minutes followed by immediately freezing in liquid nitrogen and then storage at −20°C until analysis by HPLC. The zero-minute time point measurements were made using lysates that were heat killed prior to peptide incubation. HPLC analysis was performed with a Waters 616 pump, Waters 2707 Autosampler, and 996 Photodiode Assay Detector which are controlled by Waters Empower 2 software. The separation was performed on an Agilent Zorbax 300SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with an Agilent guard column Zorbax 300SB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 12.5 mm). Elution was done with a linear 5%−85% gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in water) over 40 minutes at a 1 mL/min flow rate with UV detection at 442 nm. Sample chromatograms for RWRWR and III-67B can be seen in Supporting Information Figure S5. Peak areas were calculated by the Waters Empower 2 software by integration of peaks identified using a peak width of 30.00 and a peak threshold of 50.00. Percent intact peptide remaining was calculated by dividing the area of the parent peptide peak at each time point divided by the area of the parent peptide peak at the zero-minute time point. The identity of the parent peptide peak was confirmed using the parent peptide alone and verified with the t = 0 minute chromatogram. Experiments were performed twice. Representative chromatograms are included in Supporting Information Figure S5.

2.7 |. Fluorescent microscopy

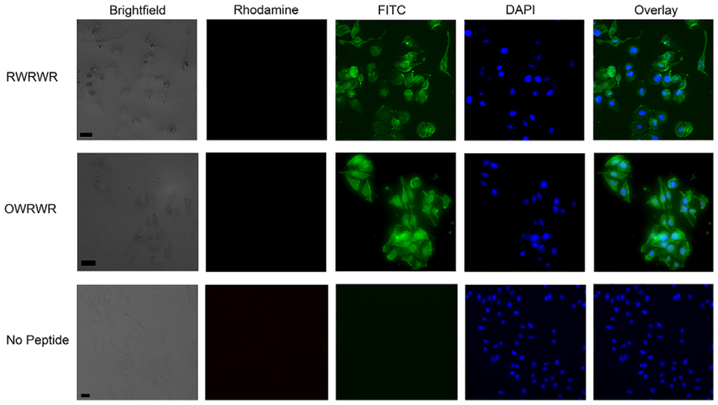

Adherent HeLa cells were cultured on Falcon CultureSlides (Corning) 24 hours prior to experimentation. On the day of experiment, the culture media was removed, and the cells were washed twice with ECB. A total of 500 μL of a 30 μM peptide solution was incubated with HeLa cells for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark. After the incubation period, the peptide solution was removed, and the cells were washed twice with ECB to remove excess, unbound peptides. Cells were then co-incubated with 4 μM Ethidium homodimer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA, USA) and 8 μM Hoechst (ThermoFisher Scientific) stains for 30 minutes and imaged immediately (Figure 6). Cellular fluorescence was visualized using a Leica DMi8 inverted microscope outfitted with a Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter cube, 20× objective (Leica HC PL FL L, 0.4× correction), and phase contrast and brightfield applications. Digital images were acquired using the Flash 4.0 high speed camera (Hamamatsu) with a fixed exposure time of 500 ms for FITC, DAPI, and Rhodamine filters, and 10 ms (brightfield). Image acquisition was controlled using the Leica Application Suite software. All images were recorded using the same parameters.

FIGURE 6.

Intracellular distribution of β-hairpin peptides in HeLa cells. A total of 30 μM RWRWR and OWRWR peptide solutions were incubated with HeLa cells seeded on glass imaging chambers for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed with ECB and co-incubated with 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (eth-D1) and 8 μM Hoechst stain for 30 minutes prior to imaging. Bottom row illustrates cells incubated with only ECB as the negative (no peptide) control. Representative images include brightfield, rhodamine (eth-D1), FITC (for peptide uptake), and DAPI (Hoechst) filters. All scale bars are 40 μm

A modified protocol was adopted to visualize peptide uptake in 4 non-adherent cell lines: OPM-2, K-526, U-937, and THP-1 (Figure 7). For this experiment, a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL was isolated from T-75 flasks by centrifugation, washed with ECB, and resuspended in a 500 μL solution containing 10 μM peptides. This suspension was incubated at 37°C in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes for 60 minutes in the dark. After incubation, the cells were pelleted, the peptide solution was removed, and the cells were washed twice with ECB. The cells were then resuspended in ECB and transferred to custom imaging chambers consisting of a silicone o-ring (Ace Glass, Vineland, NJ, USA) affixed to a glass coverslip (Corning No. 1.4, 24 × 40 mm) using high vacuum grease (Dow Corning, Milwaukee, WI) and imaged. The surface of the glass coverslip was pre-treated with 7 μL Cell-Tak (Corning) to attach the cells to the cover glass. The cells were imaged using the same microscope set-up described above.

FIGURE 7.

β-hairpin peptide cellular internalization in suspension cancer cell lines. A total of 10 μM RWRWR peptide solutions were incubated with 4 non-adherent cancer cell lines including OPM2, U937, THP-1, and K562 for 60 minutes at 37°C. Cells were attached to cover glass using Cell-Tak prior to imaging. Representative images include brightfield (left) and FITC (right) microscopy filters. All scale bars are 40 μm

An additional microscopy experiment was performed with HeLa cells (Supporting Information Figure S6) to examine the role of trypsinization after incubating the cells with a peptide solution. For this experiment, HeLa cells were seeded in a 12-well plate 3 days prior to experimentation following a protocol previously developed by Qian and coworkers[16]. On the day of experimentation, the HeLa cells were washed twice with ECB and incubated with a 10 μM peptide solutions for 60 minutes at 37°C in the dark. After the incubation period, cells were washed twice with ECB and then trypsinized for 10 minutes at room temperature. The cell suspension was transferred from the 12-well plate to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube where the cells were pelleted, and the super-natant was removed. The cells were then resuspended in ECB and then transferred to the custom imaging chamber described above coated with Cell-Tak. These cells were then incubated using the same microscopy set-up. Both negative control experiments incubating HeLa cells with the III-67B peptide and FAM solution were performed using this protocol.

3 |. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 |. Increasing the number of arginine residues enhances cellular uptake of β-hairpin protectides

It was hypothesized that the number of positively charged residues on the peptides identified by Cline and co-workers[18] and Houston and co-workers[21] could facilitate their behavior as potential CPPs. A library of β-hairpin peptides was synthesized using the sequences previously published by Houston and co-workers with different amino acid substitutions between ornithine and arginine at positions 1, 4, and 11 (Figure 1A; Supporting Information Figure S1). Ornithine was selected because it is similar in structure to lysine, yet was demonstrated to exhibit greater stability.[21] Five iterations of the β-hairpin sequences (RWRWR, RWOWR, OWRWR, OWOWO, and WKWK) were found to enter intact HeLa cells (Figure 1B). Uptake of the β-hairpin peptides was compared to an unstructured, negative control peptide (III-67B) that was previously demonstrated to be rapidly degraded under cytosolic conditions [21,23] and was initially found here to be impermeable in intact cells and thus not a CPP. Statistical t-tests were performed against this peptide to illustrate the significance of intracellular fluorescent signals for the β-hairpin peptides (Figure 1B). The 3 peptides with at least 2 arginine residues (RWRWR, OWRWR, and RWOWR) demonstrated a rapid, time-independent internalization as assessed by F-statistics (Supporting Information Table S1) and reached a statistically significant permeability efficiency compared to the negative control peptide within 20 minutes of incubation (Figure 1B). Comparing the β-hairpin sequences at the 20-minute time point revealed that the peptide with 3 arginine residues, RWRWR exhibits the highest permeability efficiency (P < .0005) while the β-hairpin peptides with a single arginine residue (WKWK) or no arginine residues (OWOWO) demonstrated the weakest permeability efficiencies (P < .005 and P < .05). Moreover, these 2 peptides with 1 (WKWK) or no arginine (OWOWO) residues exhibited slower, time-dependent internalization (Supporting Information Table S1) which required an incubation time of 100 minutes before they reached a significant permeability efficiency against the negative control peptide. At the 20-minute time point, RWRWR exhibits a 56-fold increase of fluorescence intensity compared to the negative control III67B. OWRWR and RWOWR rank second in terms of internalization potential with 49- and 42-fold increase in fluorescence activity against III67B. The third rank belongs to OWOWO, with a 16-fold increase in fluorescence activity against III67B. Finally, WKWK exhibits a 10-fold increase in fluorescence intensity against III67B. At the 100-minute time point, the top performer remains RWRWR, and the rest of the peptides perform similarly with fluorescence intensities varying within a small range (Figure 1B). These findings are supported by literature with CPPs with a greater number of arginine residues exhibiting superior uptake kinetics.[8,24] The permeability efficiencies of the β-hairpin peptides were then compared to 2 commercially available CPPs [TAT (FAM-YGRKKRRQRRR) and ARG (FAM-RRRRRRRRR)]. Both TAT and ARG exhibited better permeability efficiency compared to the β-hairpin peptides with TAT showing a 1-fold increase over RWRWR (P < 0.05) and ARG a 2-fold increase over RWRWR (P < .0001; Figure 1C). Similar to the observations for the β-hairpin peptides, both TAT and ARG were found to exhibit time-independent cellular uptake (Supporting Information Table S1). There are 2 explanations for the enhanced permeability of the TAT and ARG peptides over the members of the β-hairpin library. First is the number of arginine residues. TAT has 6 arginine residues and ARG has 9 arginine residues compared to 3 arginine residues in RWRWR. There was a correlation between the number of arginine residues and permeability efficiency in the β-hairpins, which coincides with the enhanced permeability of ARG over TAT (Figure 1C) which has previously been shown in the literature for other arginine-rich peptides.[8,25,26] The second explana tion for the enhanced uptake of TAT and ARG over the β-hairpin peptides is the absence of secondary structure.[7,8,27]

FIGURE 1.

Time-dependent cellular association of β-hairpin protectides with HeLa cells. A, Names and sequences of peptides studied. Bold amino acids (O-ornithine, R-arginine) at positions 1, 4, and 11 were altered for different library members. Substrates were acetylated at the N-terminus and amidated at the C-terminus. FAM denotes 5,6-carboxyfluorescein and “p” denotes d-pro. Scrambled, unstructured sequences of the β-hairpins peptides are denoted by an “S” in the name. B, A total of 10 μM peptide solution was incubated with intact cells followed by lysis and quantification by fluorometry. C, Comparison between the β-hairpin protectides and 2 commercially available peptides ARG and TAT. **Denotes P < .0001 and *denotes P < .05 as compared to the negative control peptide (III67B) to ensure the statistical significance of the normalized fluorometry signal for each peptide. P values correspond to the 20 minutes time point for RWRWR, OWRWR, RWOWR, ARG, and TAT peptides. P values correspond to the 100 minutes time point for OWOWO and WKWK peptides. All data are representative of duplicate experiments with each data point performed in triplicate to produce the error bars

3.2 |. Initial peptide concentration, but not incubation temperature, demonstrates a significant effect on the permeability efficiency of β-hairpin peptides

The effect of initial peptide concentration and incubation temperature on cellular uptake was assessed. All 5 members of the β-hairpin library were found to enter intact HeLa cells when incubated at 4, 25, or 37°C (Figure 2A). A statistical analysis on peptide uptake found that incubation temperature did not have a significant effect on the permeability efficiency of any member of the library (Supporting Information Table S2). The fact that decreasing the incubation temperature did not inhibit the permeability of the peptides suggests that, in the case of endocytosis, the peptides are able to escape the endosome and enter the cytosol. The absence of any significant effect of incubation temperature on permeability efficiency is indicative of the involvement of energy-independent internalization pathways like direct membrane transduction at the given experimental conditions. Both endocytosis and energy-independent internalization have been previously observed in cellular uptake of arginine-rich CPPs.[28,29]. Previous work by Duchardt and co-workers[28] revealed that direct membrane transduction was a highly efficient, nondisruptive, direct internalization mechanism that occurred at peptide concentrations 10 μM and higher. Unlike the direct translocation of CPPs that has been observed at concentrations lower than 5 μM, the integrity of the plasma membrane is fully maintained in the case of direct membrane transduction. Results discussed here are in line with a recent study by Appelbaum and co-workers[24] which demonstrated that discrete arginine arrangements embedded within a well-folded protein can direct cytosolic access by facilitating both efficient uptake and early endosomal escape.

FIGURE 2.

Temperature- and concentration-dependent internalization of β-hairpin protectides. A, Intact HeLa cells were incubated with 10 μM peptide solution for 1 hour at the indicated temperatures in the dark. B, Intact HeLa cells were incubated for1 hour at 37°C using the indicated concentrations of the 6 peptides. All data are representative of duplicate experiments with each data point performed in triplicate to produce the error bars

The effect of initial peptide concentration on cellular uptake was evaluated. There was a marked increase in peptide uptake in cells incubated with higher initial concentrations compared to cells incubated with lower concentration (Figure 2B). A statistical analysis of peptide uptake found that initial concentration does have a significant effect on the permeability efficiency, although to variable extents (Supporting Information Table S3). The effect of concentration was dramatic with the 2 peptides containing at least 2 arginine residues with one being located at the N-terminus (RWRWR and RWOWR). Similar results were observed for TAT and ARG as described in the literature.[28,29] One of the peptides with 2 arginine residues but an N-terminal ornithine residue (OWRWR) did show a concentration-dependent increase in uptake; however, this was to a slightly lesser extent (Supporting Information Table S3, P < .0005 compared to P < .0001). The effect of peptide concentration on the permeability efficiency was found to be weak and statistically insignificant for the WKWK peptide within the experimental concentration range of 10–30 μM. In other words, the uptake of WKWK peptide did not change significantly by increasing its concentration above 10 μM. This suggested that the presence of the lysine residues instead of ornithine and arginine residues as positions 4 and 11 affected the concentration-dependent uptake within the experimental range.

3.3 |. Secondary structure of β-hairpin protectides reduces peptide internalization

One potential explanation for the enhanced permeability efficiencies of TAT and ARG compared to β-hairpin peptides is their lack of secondary structure. To explore this, 3 scrambled peptides were synthesized (S-RWRWR, S-OWRWR, and S-OWOWO) using the same amino acids as their structured counterparts, but with these amino acids at different positions to eliminate the secondary structure (Figure 1A). CD was used to determine the intrinsic structure of the RWRWR and S-RWRWR peptides in addition to the TAT peptide (Figure 3). The CD spectra of the S-RWRWR and TAT peptides confirmed that they were unstructured based on a minimum near 195 nm. Conversely, the CD spectrum of RWRWR displayed characteristics of the β-hairpin with a minimum near 205 nm (Figure 3). Moreover, RWRWR exhibits a maximum near 225 nm that arises from exciton coupling of the indole rings of the cross-strand Trp residues, further supporting the correct-fold.[30] These spectra are consistent with the CD spectrum of related peptides WKWK,[31] WRWR,[32] OWRWR,[21] OWOWO,[21] and S-OWOWO[21] that have been previously characterized by both NMR and CD and shown to adopt a well-folded β-hairpin.

FIGURE 3.

CD spectra of β-hairpin and linear peptides. Experiments were performed using 40 μM peptide solution in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.02 at 25°C. The RWRWR peptide (black) exhibited spectra associated with a well-folded β-sheet confirmation with a minimum near 205 nm. Conversely, the S-RWRWR (red) and TAT (blue) peptides were determined to be unstructured based on the minimum near 195 nm

The permeability efficiency was quantified for the unstructured, scrambled sequences, and compared to original structured sequences. All scrambled peptides demonstrated significant permeability efficiency against the negative control within 20 minutes of incubation (Figure 4). The scrambled RWRWR peptide (S-RWRWR) exhibited a superior permeability efficiency observable from the 20-minute time point. The signal increased with time and reached over 3-fold increase in uptake compared to RWRWR at the 100-minute time point (P < .005). A comparison between the uptake efficiency of S-RWRWR and TAT at the 100-minute time point showed over 1-fold increase in permeability efficiency for S-RWRWR (P < .001), suggesting that peptide internalization was enhanced by the lack of secondary structure. Similar findings have been reported and discussed in the literature suggesting that the incorporation of secondary structure such as a β-hairpin in the peptide backbone in an attempt to stabilize a CPP can partially compromise their cellular uptake efficiency.[8,15,33] Another interesting finding was that the cellular uptake of S-RWRWR was found to be time-dependent with maximal peptide uptake occurring at the 100-minute time point. This contrasts with the RWRWR peptide, which displayed no significant time effect on peptide internalization (Supporting Information Table S1). This is an indication of a steady internalization process for S-RWRWR compared to RWRWR that penetrates the cells rapidly and remains unchanged after 20 minutes. The S-OWRWR and S-OWOWO peptides did not exhibit any significant time-dependence in permeability (Supporting Information Table S1). Similar to the β-hairpins, no significant temperature-dependence was observed in the permeability of the scrambled sequences (Supporting Information Figure S4 and Table S2).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of secondary structure on peptide uptake efficiency. “S” peptides refer to scrambled sequences of the RWRWR, OWRWR, and OWOWO peptides that lack any secondary structure. A total of 10 μM peptide solution was incubated with HeLa at the indicated time points. **Denotes P < .0001 and *denotes P < 0.05. All P values were calculated relative to the negative control peptide III67B. All data are representative of duplicate experiments with each data point performed in triplicate to produce the error bars

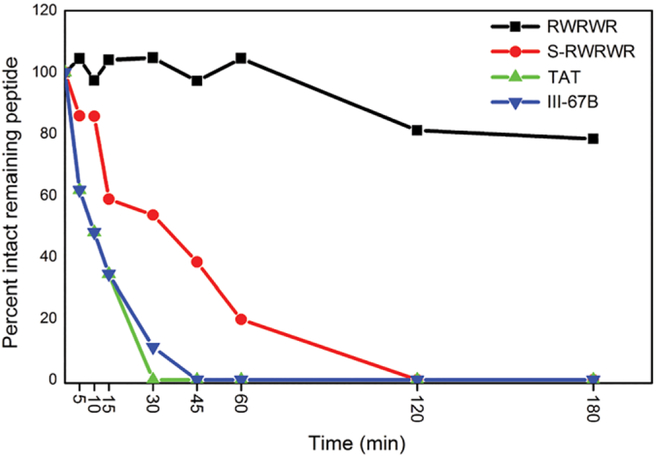

3.4 |. β-hairpin protectides demonstrate enhanced stability under cytosolic conditions

A prior study by Cline and co-workers demonstrated that the WKWK peptide was highly resistant to peptidase-mediated degradation[18] and a similar study by Houston and co-workers[21] confirmed that OWRWR exhibited a similar behavior in cell lysates. To investigate the stability of the peptides in this study, select peptides were incubated with HeLa lysates to mimic the intracellular environment. As expected, the RWRWR peptide was resistant to degradation in HeLa lysates (Figure 5, black squares) with ~80% peptide remaining after 180 minutes yielding a half-life of 420 minutes for the intact peptide in the cytosolic mixture. These findings match the degradation studies in OPM2 lysates by Houston and co-workers with the OWRWR peptide.[21] Conversely, the S-RWRWR peptide was mostly degraded within 120 minutes (Figure 5, red circles) with a half-life of 30 minutes. Thus, the secondary structure present in RWRWR resulted in an increase in stability compared to its unstructured counterpart. It was found that TAT was mostly degraded within 30 minutes (Figure 5, blue triangles) with a half-life of 10 minutes. The stability of TAT was comparable to the unstructured negative control peptide, III-67B, which was previously found to rapidly degrade under cytosolic conditions.[21] In this study, III-67B (Figure 5, green triangles) displayed a half-life of 9.5 minutes, similar to that found by Houston and co-workers chromatograms showing the degradation of RWRWR and III67B are shown in Supporting Information Figure S5. These findings indicate that while the presence of secondary structure in a CPP can decrease the permeability efficiency, it will increase the stability of the peptide once it gains entry into intact cells. These findings are consistent with previous observations for stable CPPs using D-amino acids,[10,34] β-amino acids,[11,12] or cyclic structures.[27,35,36]

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of peptide degradation in HeLa lysates using RPHPLC. The stability of the structured, unstructured, and commercially available peptides was evaluated by incubation with 2 mg/mL HeLa lysates at 37°C. The structured β-hairpin RWRWR (black squares, t1/2 = 423.08 minutes) was substantially more resistant to degradation than its unstructured counterpart S-RWRWR (red circles, t1/2 = 27.9 minutes) as evidenced by a substantially greater amount of intact peptide and a significantly higher half-life. The commercially available TAT peptide exhibited rapid degradation in the HeLa lysates (green triangle, t1/2 = 10.0 min). An unstructured, rapidly degraded peptide (III-67B) was used as a positive control to demonstrate the activity of the HeLa lysates (inverted blue triangles,t1/2 = 9.5 minutes). The zero minute time point was achieved using heat shocked lysates and served as the baseline for intact peptide

3.5 |. Cellular distribution of internalized β-hairpin peptides in model cancer cell lines

Live-cell microcopy studies were performed to provide further evidence of the internalization of the β-hairpin peptides. HeLa cells, previously seeded on microscopy glass slides, were incubated with the RWRWR and OWRWR peptides and immediately visualized to show the intracellular peptide distribution in intact cells while preserving the intact cell morphology (Figure 6). Cell nuclei were co-stained with Hoechst, and viability was assessed using Ethidium homodimer-1 (Eth-D1). The absence of any signal from the Eth-D1 confirmed the absence of any dead cells and cell debris in the images and therefore the viability of cells after incubation with peptides at a concentration as high as 30 μM. A negative control was performed incubating cells with ECB (no peptide) to confirm the intracellular fluorescence was due to the CPPs (Figure 6). It was observed that the RWRWR and OWRWR peptides were distributed across the cytosol and nucleus of HeLa cells in a heterogenous manner in terms of both intracellular peptide distribution and cell-to-cell variability. These results suggest that there is an inherent heterogeneity in cellular uptake with select cells showing greater peptide uptake than others. These findings are in line with current efforts in single cell analysis of cancer cells[5,23,37] and will be investigated in future studies using high-throughput single cell screening methods. Nevertheless, these results confirm that the β-hairpin sequences introduced here can enter intact cells and exhibit cytosolic and nuclear distribution within the cell while maintaining cell viability.

An additional microscopy experiment was performed to investigate the role of trypsinization prior to imaging the cells using fluorescent microscopy to determine if the trypsinization step altered peptide uptake (Supporting Information Figure S6). HeLa cells were incubated with 4 FAM-labeled peptides (RWRWR, OWRWR, TAT, and ARG) for 60 minutes at 37°C and then trypsinized after the incubation period, prior to imaging, to remove any peptide bound to the outside of the cell as an additional control. It has been previously reported in the literature that trypsin removes cell-surface bound proteins without affecting internalized peptides.[24] Similar results of peptide uptake were observed in HeLa cells including or removing a trypsinization step prior to imaging. It was observed that the fluorescent signal was distributed across the cells treated with both RWRWR and OWRWR indicating cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of the peptide (Supporting Information Figure S6A,B). A similar result was observed for cells treated with the positive controls TAT and ARG (Supporting Information Figure S6C,D). Control experiments were performed treating the cells with the non-permeable III-67B peptide and the fluorophore FAM which showed no observable increase in fluorescent signal confirming that the negative control peptide and the fluorophore alone were not capable of cellular entry (Supporting Information Figure S6E,F). Control experiments containing no peptide were performed along with every microscopy experiment that resulted in no observable fluorescent signal.

The uptake of the RWRWR peptide was also assessed in 4 non-adherent cancer cell lines. A total of 10 μM RWRWR peptide solutions were incubated with a multiple myeloma cell line (OPM2), a lymphoma cell line (U937), an acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1), and a chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line (K562) as shown in Figure 7. All non-adherent cell lines showed prominent cellular uptake of the RWRWR peptide; however, the localization within the cell varied. An evenly distributed fluorescent signal was observed in OPM2, K562, and U937 cells while punctuate fluorescence was observed in the THP-1 cells. This confirms that the β-hairpin peptides can gain entry to non-adherent cell lines as well as adherent cell lines.

4 |. CONCLUSIONS

With the increased use of peptide-based reporters in addition to coupling CPPs with peptide and small molecule drugs, there is a great need to identify new classes of CPPs with enhanced intracellular stability. This work identified that peptides with a β-hairpin sequence motif functioned as CPPs while simultaneously behaving as long-lived protectides. The cellular uptake of 3 of β-hairpin peptides (RWRWR, OWRWR, and RWOWR) was found to be time-independent above 10 minutes of incubation, while the uptake of all 5 peptides was found to be temperature-independent. However, initial concentration did affect peptide uptake in the peptides with 2 or more arginine residues. It was determined that the number of arginine residues present in the peptide correlates with optimal permeability efficiency of the β-hairpin peptides, with the RWRWR peptide displaying the best permeability efficiency. A comparison between the structured β-hairpin peptides, unstructured scrambled sequences, and unstructured commercially available CPPs (TAT and ARG) indicated that the presence of a secondary structure decreases the cellular uptake of the peptides. However, the secondary structure confers an increase in peptide stability. Thus, there exists a tradeoff between uptake kinetics and intra-cellular stability of CPPs which has been demonstrated in the literature and now includes peptides with secondary structure to those with D-amino acids and β-amino acids.[8,11,12,34,36] The superior intracellular stability of the β-hairpin peptides makes them ideal candidates for peptide-based reporters or PROTAC-based therapeutics that require long-lived peptides. Live-cell microscopy images visualized peptide localization in cytosol of intact cells and confirmed cell viability. The degree of peptide uptake across the population of cells was found to be heterogeneous both in terms of cell to cell variability and intracellular peptide distribution. Work is currently underway to further investigate this phenomenon by performing high-throughput single cell analysis of CPP uptake in intact cells. These future studies aim to provide a greater understanding of CPP uptake efficiency and intra-cellular peptide homogeneity in addition to identifying the underlying subpopulations found in each sample.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, R03EB02935 (ATM), the National Science Foundation, CBET1509713 (ATM), the LSU College of Engineering FIER—Round VII (ATM), and the LSU Council on Research (ATM). The authors thank Rachel Nguyen (Louisiana State University) for some assistance with preliminary experiments.

Funding information

LSU Council on Research; LSU College of Engineering; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: CBET1509713; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, Grant/Award Number: R03EB02935

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Hamley I, Chem. Rev 2017, 117(24), 14015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Craik D, Fairlie D, Liras S, Price D, Chem. Biol. Drug Des 2013, 81(1), 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gonzalez-Vera JA, Morris MC, Proteomes 2015, 3, 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kauffman W, Fuselier T, He J, Wimley W, Trends Biochem. Sci 2015, 40(12), 749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kovarik M, Allbritton N, Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29(5), 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ottis P, Crews C, ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12(4), 892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cromm P, Spiegel J, Kuchler P, Dietrich L, Kriegesmann J,Wendt M, Goody R, Waldmann H, Grossmann T, ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11(8), 2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kristensen M, Birch D, Nielsen H, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2016, 17(2), 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tugyi R, Mezo G, Fellinger E, Andreu D, Hudecz F, J. Pept. Sci 2005, 11(10), 642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tugyi R, Uray K, Ivan D, Fellinger E, Perkins A, Hudecz F, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102(2), 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Peterson-Kaufman K, Haase H, Boersma M, Lee E, Fairlie W,Gellman S, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10(7), 1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Werner H, Cabalteja C, Horne W, ChemBioChem 2016, 17(8), 712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pelay-Gimeno M, Glas A, Koch O, Grossmann T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54(31), 8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Qian Z, Martyna A, Hard R, Wang J, Appiah-Kubi G, Coss C,Phelps M, Rossman J, Pei D, Biochemistry 2016, 55(18), 2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Daniels D, Schepartz A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129(47), 14578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Qian Z, Liu T, Liu Y, Briesewitz R, Barrios A, Jhiang S, Pei D, ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8(2), 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang S, Proctor A, Cline L, Houston K, Waters M, Allbritton N, Analyst 2013, 138(15), 4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cline L, Waters M, Biopolymers 2009, 92(6), 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ray K, Hines C, Coll-Rodriguez J, Rodgers D, J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279(19), 20480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tian Y, Zeng X, Li J, Jiang Y, Zhao H, Wang D, Huang X, Li Z, Chem. Sci 2017, 8(11), 7576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Houston KM, Melvin AT, Woss GS, Fayer EL, Waters ML,Allbritton NL, ACS OMEGA 2017, 2(3), 1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brooks H, Lebleu B, Vives E, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2005, 57(4), 559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Proctor A, Wang Q, Lawrence D, Allbritton N, Anal. Chem 2012, 84(16), 7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Appelbaum J, LaRochelle J, Smith B, Balkin D, Holub J,Schepartz A, Chem. Biol 2012, 19(7), 819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kristensen M, Franzyk H, Klausen M, Iversen A, Bahnsen J,Skyggebjerg R, Fodera V, Nielsen H, AAPS J 2015, 17(5), 1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rothbard J, Jessop T, Lewis R, Murray B, Wender P, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126(31), 9506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kwon Y, Kodadek T, Chem. Biol 2007, 14(6), 671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Duchardt F, Fotin-Mleczek M, Schwarz H, Fischer R, Brock R, Traffic 2007, 8(7), 848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brock R, Bioconjug. Chem 2014, 25(5), 863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cochran A, Skelton N, Starovasnik M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2001, 98(10), 5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Park J, Waters M, Org. Biomol. Chem 2013, 11(1), 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Butterfield S, Sweeney M, Waters M, J. Org. Chem 2005, 70(4), 1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Caesar C, Esbjorner E, Lincoln P, Norden B, Biophys. J 2009, 96(8), 3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nielsen E, Yoshida S, Kamei N, Iwamae R, Khafagy E, Olsen J,Rahbek U, Pedersen B, Takayama K, Takeda-Morishita M, Control J. Release 2014, 189, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rezai T, Yu B, Millhauser G, Jacobson M, Lokey R, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128(8), 2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Qian Z, LaRochelle J, Jiang B, Lian W, Hard R, Selner N,Luechapanichkul R, Barrios A, Pei D, Biochemistry 2014, 53(24), 4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Proctor A, Wang Q, Lawrence D, Allbritton N, Analyst 2012, 137(13), 3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.