Abstract

Objectives

To study the trajectories of body mass index (BMI) in Norway over five decades and to assess the differential influence of the obesogenic environment on BMI according to genetic predisposition.

Design

Longitudinal study.

Setting

General population of Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway.

Participants

118 959 people aged 13-80 years who participated in a longitudinal population based health study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, HUNT), of whom 67 305 were included in analyses of association between genetic predisposition and BMI.

Main outcome measure

BMI.

Results

Obesity increased in Norway starting between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s and, compared with older birth cohorts, those born after 1970 had a substantially higher BMI already in young adulthood. BMI differed substantially between the highest and lowest fifths of genetic susceptibility for all ages at each decade, and the difference increased gradually from the 1960s to the 2000s. For 35 year old men, the most genetically predisposed had 1.20 kg/m2 (95% confidence interval 1.03 to 1.37 kg/m2) higher BMI than those who were least genetically predisposed in the 1960s compared with 2.09 kg/m2 (1.90 to 2.27 kg/m2) in the 2000s. For women of the same age, the corresponding differences in BMI were 1.77 kg/m2 (1.56 to 1.97 kg/m2) and 2.58 kg/m2 (2.36 to 2.80 kg/m2).

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that genetically predisposed people are at greater risk for higher BMI and that genetic predisposition interacts with the obesogenic environment resulting in higher BMI, as observed between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s. Regardless, BMI has increased for both genetically predisposed and non-predisposed people, implying that the environment remains the main contributor.

Introduction

Obesity has almost tripled worldwide since 1975, yet the origins of the obesity epidemic are still unclear.1 2 3 An altered dietary pattern is the most plausible environmental factor influencing excess energy balance4 5; however, a more sedentary lifestyle and possibly changes in the biological environment, such as toxins and microbiota, could also contribute.6 Although secular trends can change the prevalence of obesity in an entire population simultaneously,5 genetic differences could make some people more susceptible than others to an obesogenic environment.7 8 9 10

Heritability estimates for obesity of between 0.5 and 0.8 in twin and adoption studies indicate a strong genetic contribution at the individual level.11 12 In contrast with these estimates, genome-wide association studies have identified genetic variants that explain a mere 2-5% of variation in BMI.13 14 Although the biological pathways are still not fully understood, the identified genetic variants consistently predict overweightness and obesity and weight gain throughout life.7 8 Genetic variants predisposing to obesity might also modify behavioural responses to the environment, creating a gene-environment interaction.10 15 For instance, dietary components, physical activity, and socioeconomic status might alter the association between genetic predisposition and BMI,10 15 allowing for a targeted approach to obesity prevention and treatment.10 Although environmental changes likely precipitated the obesity epidemic,5 genetic predisposition could also interact with secular trends, thereby affecting the distribution of obesity in the population under changing environmental conditions. Limitations such as self reported BMI, fewer genetic variants for BMI, short follow-up, or a selected older population10 prevented previous studies from quantifying the impact of a gene-environment interaction during the obesity epidemic.

Our study assessed to what extent recent secular trends have affected genetically predisposed and non-predisposed people differently. From 1963 to 2008 we have followed a large Norwegian population longitudinally with repeated measurements of BMI.

Methods

The study population is based on data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT, 1984-2008) linked to previous height and weight measurements for the same participants in the tuberculosis screening programme (1963-75).

Our study sample consisted of 118 959 participants aged 13-80 who participated in HUNT and had valid repeated measurements for BMI. The HUNT population is an ethnically homogeneous cohort with an age span from adolescence to late adulthood and is representative of the Norwegian population. The entire adult population was invited and data gathering was conducted in three waves: HUNT1 (1984-86), HUNT2 (1995-97), and HUNT3 (2006-08).16 HUNT includes survey information on health, lifestyle, drug treatment, family situation (eg, cohabiting), and social security, as well as clinical measures such as blood pressure, height, weight, and waist-hip circumference.16 Participation declined from 88% in HUNT1 to 71% in HUNT2 and subsequently 54% in HUNT3. Blood samples were collected from adults participating in HUNT2 and HUNT3. The Young-HUNT survey is the adolescent part of HUNT, including teenagers aged 13-19 years. The first Young-HUNT survey was performed in 1995-97, simultaneous with HUNT2. In 2000-01, Young-HUNT2 was performed as a follow-up of 2400 participants from Young-HUNT1. Young-HUNT3 took place with HUNT3.

The tuberculosis screening programme was established in 1943 and contributed to the surveillance of tuberculosis in the general Norwegian population.17 Starting in 1963, efforts were gradually directed to the surveillance of groups at high risk of tuberculosis. Simultaneously, the systematic measurement of height and weight was introduced. As participants aged less than 14 years were not considered targets for total population surveillance, we excluded their BMI measurements. In the analysis studying the effect of decade, we used data from the tuberculosis screening programme limited to 1966-69, as this interval contains most of the observations.

BMI assessment

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms per metre squared. Weight was measured to the nearest half kilogram with the participants wearing light clothes and no shoes, and height was measured to the nearest centimetre.18 The World Health Organization defines overweight as a BMI greater than or equal to 25 and obesity as a BMI greater than or equal to 30.1 BMI strongly relates to longitudinal growth, and for participants younger than 18 years we calculated their BMI z score, using the International Obesity Task Force reference to adjust for age and sex.19 Each participant’s BMI z score was subsequently used to estimate the corresponding BMI at age 18 years.

Genotyping and computation of genetic risk score

Genotyping of the adult participants in HUNT2 and HUNT3 was carried out with one of three different Illumina HumanCoreExome arrays (HumanCoreExome12 v1.0, HumanCoreExome12 v1.1, and UM HUNT Biobank v1.0, Illumina, CA), as described previously.20 We included 96 of the 97 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) previously identified to be associated with BMI in the Giant Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium.13 We lacked data on one SNP (rs12016871) owing to insufficient quality of genotyping or imputation procedures. The supplementary file provides more details about the quality control procedure.

We first multiplied the number of risk alleles for each of the 96 BMI associated SNPs with the estimated effect size of that particular SNP on BMI published by the GIANT consortium,13 and then summarised over all SNPs to create a weighted genetic risk score.21 The study population was divided into five equal sized groups, the top fifth group being the most genetically susceptible to higher BMI and the bottom fifth group being the least. Additional analyses were done with a proxy (rs4771122) in linkage disequilibrium (r2=0.88, DPrime 1.00) replacing the excluded SNP.

Statistical analysis

We analysed longitudinal trajectories in BMI using linear multilevel mixed models with observations clustered within individuals, and with a random slope for age. Analyses were performed separately for men and women. We estimated BMI growth trajectories for different birth cohorts in the total study sample and included age and the square of age as continuous covariates. Then we estimated the effect of genetic risk of obesity on BMI according to time of measurement and age. For optimal age adjustment, we created linear splines of age with knots at every decile. We used bayesian information criteria to compare goodness of fit for models with two year, five year, 10 year, 15 year, and 20 year age bands, and concluded 10 year age bands to be the most appropriate model. Based on this model, we plotted the estimated BMI for the highest compared with the lowest fifth of genetic susceptibility to BMI for chosen ages at each decade for men and for women. In the main text we present results for adults aged 25-55 years, as this age band shows a relevant age span and was most complete in our dataset. The supplementary file provides information on estimated BMI for each fifth of genetic risk, marginal effects, and the statistical modelling.

We performed several additional analyses. Firstly, we estimated the association between BMI measured in the 1960s and availability of genetic data to investigate the possibility of a selection bias. Secondly, we performed sensitivity analyses including only people born after 1940 as there was evidence of lower participation among those with higher BMI in the older birth cohorts. Thirdly, as our genetic risk score was based on genome-wide analyses performed in adults, whereas our data also included adolescents, we assessed the impact of excluding people younger than 20 years from the analyses. Fourthly, we assessed the associations using the fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) SNP alone. FTO is the dominating BMI associated SNP that is also associated with BMI in childhood.22 Fifthly, we restricted the analyses to self reported never smokers in the 1990s or the 2000s to assess whether smoking trends could affect the results. Sixthly, we assessed the association between genetic risk and obesity rather than genetic risk and BMI. For similarity with the main model and to maintain a population averaged effect, we chose a linear probability model. Finally, we assessed the association between genetic risk score and the natural logarithm of BMI. This was done to approximate the relative difference in BMI rather than the absolute difference in BMI between the top and bottom fifth of genetic predisposition.23 Analyses were performed with StataMP 15.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design or implementation of the study. As the study used previously collected data, we did not ask patients or the public to assess the burden of participation. We will seek involvement from a patient organisation in the development of an appropriate method of dissemination.

Results

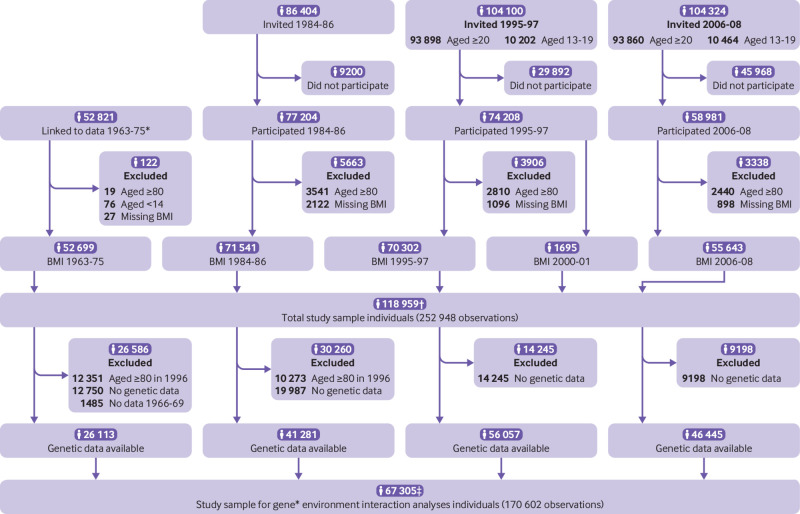

The study sample included 118 959 participants aged 13-80 years with a total of 252 948 BMI measurements (fig 1). Of these individuals, 67 305 were included in analyses of the association between genetic predisposition and BMI, with an average of 2.6 observations per person. Participants in the 1960s were five to 10 years younger than those at other time points, except for 2000-01 when only adolescents participated (see supplementary table S1).

Fig 1.

Flowchart of study participants and criteria for inclusion in study sample. *Linkage to data from tuberculosis screening programme 1963-75 required participation in any part of Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. †Of 52 699 people with body mass index (BMI) measured in 1963-75, 48 959 had another valid BMI measurement before age 80. Of the 71 541 people with BMI measured in 1984-86, 43 723 had BMI measured also in 1995-97 and 27 536 had BMI measured also in 2006-08. Of these, 25 253 had BMI measured in 1984-86, 1995-97, and 2006-08. Of 1695 people who had BMI measured in 2000-01, 1664 had valid BMI measurements in 1995-97. 36 292 people had BMI measured in 1995-97 and 2006-08. ‡Of the 26 113 people with genetic data and BMI measured in 1966-69, 26 082 also had another valid BMI measurement before age 80. Of the 41 281 people with genetic data and BMI measured in 1984-86, 38 888 also had a valid BMI measurement in 1995-97 and 26 927 also had BMI measured in 2006-08. Of these, 24 714 had BMI measured in 1984-86, 1995-97, and 2006-08. 35 408 people had genetic data and BMI measured before age 80 in 1995-97 and 2006-08

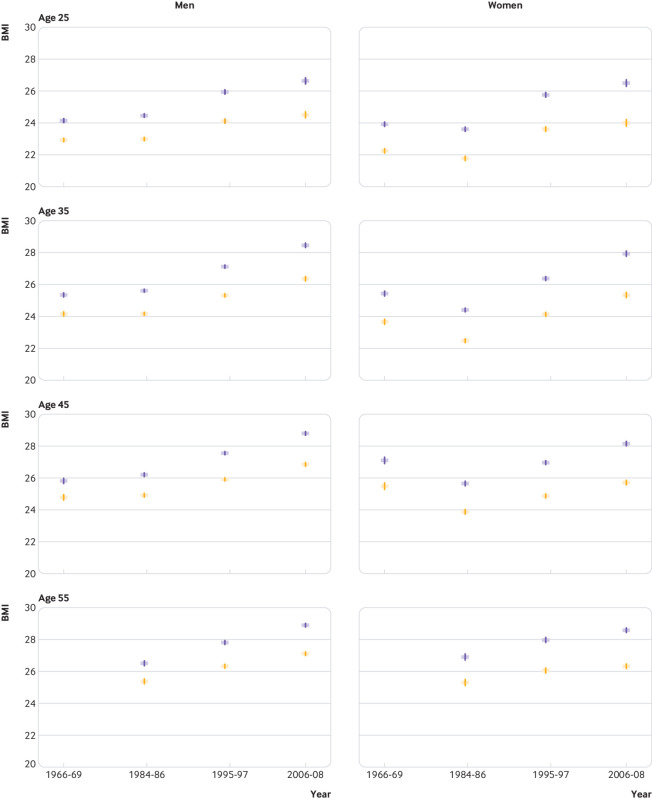

Our data showed a noticeable increase in BMI in Norway starting between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. Men and women became heavier with both age and birth cohort, and, compared with older birth cohorts, those born after 1970 had a substantially higher BMI already in young adulthood (figs 2 and 3, also see supplementary figs S1 and S2). Men aged 35 in the bottom fifth of genetic predisposition were 2.20 kg/m2 (95% confidence interval 2.05 to 2.35 kg/m2) heavier in the 2000s compared with the 1980s. The corresponding difference among 35 year old women was 2.88 kg/m2 (2.70 to 3.06 kg/m2). Slightly smaller differences were found among the other ages (see supplementary table S4). We also found a relatively high and stable BMI among middle aged women in the earliest cohorts (primarily before 1920 and 1920-29) and a subsequent decrease in BMI among this group from the 1960s to 1980s.

Fig 2.

Body mass index (BMI) trajectories with 95% confidence intervals for women and men by birth cohort. Estimates from a linear mixed model of participants in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, Norway. The most recent cohorts are observed at the youngest ages (on left of graph)

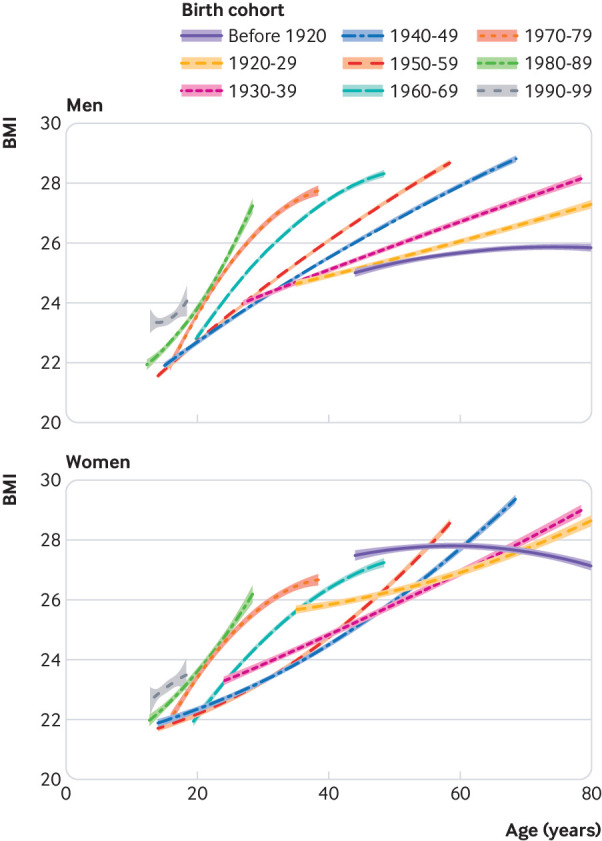

Fig 3.

Estimated body mass index (BMI) by top (most susceptible, shown in blue) and bottom fifth (least susceptible, shown in orange) of genetic risk score by age and time point for 31 823 men and 35 482 women who participated in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, Norway

The difference in BMI between the top and bottom fifth of genetic susceptibility (highest and lowest, respectively) was substantial for all ages at each time point, and the difference increased gradually from the 1960s to the 2000s (fig 3, see supplementary table S5). For men aged 35, the most genetically predisposed fifth had 1.20 kg/m2 (1.03 to 1.37 kg/m2) higher BMI than the least genetically predisposed fifth in the 1960s compared with 2.09 kg/m2 (1.90 to 2.27 kg/m2) in the 2000s. For women of the same age, the corresponding differences in BMI were 1.77 kg/m2 (1.56 to 1.97 kg/m2) and 2.58 kg/m2 (2.36 to 2.80 kg/m2). Hence, the increased difference in BMI of 0.89 kg/m2 (0.63 to 1.15 kg/m2) and 0.81 kg/m2 (0.51 to 1.12 kg/m2) for men and women, respectively, in the 2000s, could be attributed to the gene-obesogenic environment interaction (see supplementary table S6).

When survival bias was assessed, a weak association was found between BMI measured in the 1960s and survival to and participation in genetic analyses in the 1990s (odds ratio 0.98, 95% confidence interval 0.98 to 0.99, per kg/m2). However, this was not as apparent among cohorts born in 1940 and later (odds ratio of having genetic data 0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.98 to 1.01, per kg/m2 in the 1960s). When restricting analyses of the association between time point and BMI to these cohorts, estimates were similar to those of the main results. This restriction, however, prevented estimation of BMI in the1960s for anyone older than 27 years (see supplementary fig S3).

Additional analyses showed that restricting the study sample to never smokers did not change results substantially (see supplementary fig S4). As expected, the associations with FTO alone were weaker than the associations with the genetic risk score yet showed the same trends as in the main analyses (see supplementary fig S5).

Furthermore, we used the natural logarithm of BMI as the outcome and still found evidence of a small interaction between genetic risk and time (see supplementary table S7). This interaction was thus evident on a multiplicative scale; however, the relative difference in BMI according to genetic risk was constant over time. Among the most genetically predisposed men aged 35-45, estimated prevalence of obesity increased from less than 10% in the 1960s to more than 30% in the 2000s (see supplementary fig S6). In comparison, for the least predisposed 35 year old men, the estimated prevalence of obesity increased from nearly 2% in the 1960s to 13% in the 2000s. For women aged 35-45, the estimated prevalence of obesity decreased between the 1960s and 1980s. From the 1980s, the estimated prevalence of obesity increased steadily by time for both men and women. When analyses were repeated using a proxy (rs4771122) in linkage disequilibrium (r2 0.88, DPrime 1.00) for the one excluded SNP, results were consistent with the main results (data not shown).

Discussion

In the Norwegian population, body mass index (BMI) increased substantially from the 1960s to 2000s for both men and women, and the increase was more evident in people with a genetic predisposition to higher BMI. Our study suggests that genetic predisposition interacts with the obesogenic environment and this has resulted in higher BMI in recent decades. This finding provides a novel insight into the role of genetics in the development of obesity.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of our study is that we followed a large ethnically homogeneous Norwegian population longitudinally from 1963 to 2008 with repeated standardised measurements of BMI. This population provides an adequate sample size with an age range from adolescence to late adulthood. The ability to link genetic data from these participants to their BMI trajectories provided a unique opportunity to quantify the role of genetics on the development of obesity.

The first wave of the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study survey (HUNT1) is considered unselected as 88% of the Nord-Trøndelag adult population attended. As in most other population based studies, participation in the surveys declined from the first wave (HUNT1) to third wave (HUNT3).18 A non-participation study for HUNT3 with self reported height and weight provided little evidence for higher BMI among non-participants.24 We assumed this to be true for both HUNT1 and HUNT2 with far greater participation. Selective survival to date of genetic assessment in 1995-97 is another potential source of bias. When limiting the analyses to participants younger than 80 in 1996, those with a higher BMI in the 1960s had a slightly lower participation in genetic analyses. This was not apparent among cohorts born in 1940 and later, however, and additional analyses restricted to these cohorts did not change the results. Hence, estimates from the 1960s for those aged 27 years and older should be interpreted with caution. Current genome-wide association studies have identified mutations that explain a mere 2-5% of variation in BMI.13 14 We cannot rule out that our estimates could have been different with a better classification of genetically predisposed and non-predisposed people.

Comparison with other studies

Our data suggest that the obesity epidemic was noticeable in Norway between the mid-1980s and 1990s. This trend was even more apparent in the US in the mid-1970s, and several other countries have shown similar results.5 The obesity epidemic is largely attributed to over-nutrition and sedentary behaviour, both related to sociodemographic characteristics. However, the underlying cause is likely a complex combination of globalisation, industrialisation, and other societal, economic, cultural, and political factors. One example is related to the American food bill introduced in the 1970s. This political reform might have helped precipitate the obesity epidemic in the United States by changing food supplies that ultimately lead to unfavourable dietary patterns.5 In Norway, the 1980s were characterised by increased prosperity as a result of new working cultures, increased market consumption, and, feasibly, a comparable change in eating patterns, influenced by North America and the rest of Europe.25 26 The decrease in BMI primarily in middle aged women from the 1960s to the 1980s is puzzling, yet population based studies across Norway have found similar trends.27 Delayed transitioning to sedentary work, greater parity, and new societal trends in female body image to a slimmer ideal could have contributed.

Genetic predisposition may not have precipitated the obesity epidemic but may still play an important role in the development of obesity. Our findings indicate a substantial difference in BMI between genetically predisposed and non-predisposed people in all age groups. This finding is of clinical interest as it corresponds to a difference in estimated prevalence of obesity among the most and least genetically predisposed people in recent decades. Hence, those with a predisposition are more likely to be obese and experience the social and physical burdens of obesity and obesity related diseases.

The obesogenic environment could be amplifying the effect of genetic predisposition on obesity10 from in utero to agedness.28 This gene-environment interaction has been exposed by converging findings from heritability, syndromic, monogenic, and polygenic obesity studies.28 Earlier studies have suggested that the association between genetic risk score and BMI was of greater magnitude in more recent birth cohorts or in social groups more exposed to an obesogenic environment.9 29 30 Compared with these studies, our dataset was large and comprised a wide range of ages containing measured BMI before and after the onset of the obesity epidemic. We confirmed a stronger association between genetic risk and BMI in the years with the most obesogenic environment. The difference in BMI attributable to the gene-environment interaction was almost 1 BMI unit, which is of clinical significance at the population level.

A British study with 120 000 participants of European decent showed that the combination of physical activity, sedentary time, television watching, and Western diets interacted with the genetic risk score for BMI.15 Evidence that a specific aspect of the environment or a certain behaviour interacts directly with the genetic risk score for BMI is difficult to prove. Changes in dietary patterns to unhealthy foods and increased portion size, sedentary lifestyle, and socioeconomic inequality are possible candidates; however, the undoing of these changes is less likely without extreme individual motivation and major societal transformation.10 Although we lacked detailed pathophysiological understanding of the influence of SNPs on phenotype,10 we suspect that those with a genetic predisposition for obesity will gain more weight by eating more unhealthy foods when these are readily available. This agrees with our knowledge of hypothalamic appetite control as there is an enriched expression of genes near the loci regulating BMI in the central nervous system.10

Generalisability of the findings

Genetic risk is likely to differ slightly among populations as the genetic variants associated with BMI may vary. Furthermore, environments could be more obesogenic or less obesogenic. Although the estimates for gene-environment interaction might differ, the underlying mechanisms for how genetic variants affect BMI are likely the same. As a result, the interplay between genes and the environment will exist in populations worldwide.

Conclusions and implications

Since the mid-1980s, Norway has experienced an obesity epidemic. The population shift towards a higher overall BMI implies that more people are experiencing the physical and social burdens of obesity and obesity related diseases. Cohorts born after 1970 have a substantially higher BMI already in young adulthood and are subject to the implications of lifelong obesity. Our study provides statistical evidence that genetically predisposed people are at greater risk of a higher BMI and that genetic predisposition interacts with the obesogenic environment resulting in the higher BMI in recent decades. Regardless of BMI being a heritable trait,11 12 secular trends have increased BMI for both genetically predisposed and genetically non-predisposed people. This reinforces the need for more effective preventive strategies that would benefit the population as a whole and that could prove to be particularly advantageous among people with a genetic predisposition to obesity.

What is already known on this topic

Heritability, syndromic, monogenic, and polygenic studies indicate a gene-environment interaction in the development of obesity

Previous polygenic studies are limited by a narrow age span, short follow-up, and self reported body mass index (BMI)

How the effect of genetic predisposition to obesity differs as environments are becoming more obesogenic is unknown

What this study adds

Genetic predisposition seems to interact with the obesogenic environment resulting in a higher BMI in recent decades

Regardless, BMI has increased for both genetically predisposed and non-predisposed people, implying that the environment remains the main contributor

More effective obesity prevention strategies would benefit the population as a whole and that could prove to be particularly advantageous among people with a genetic predisposition to obesity

Acknowledgments

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU, Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The genotyping in HUNT was financed by the National Institutes of Health; University of Michigan; the Research Council of Norway; the Liaison Committee for Education, Research and Innovation in Central Norway; and the Joint Research Committee between St Olavs hospital and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU. The genotype quality control and imputation was conducted by the K.G. Jebsen centre for genetic epidemiology, Department of public health and nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health provided data from the tuberculosis screening programme used in this study. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health does not accept responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented in this publication.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: additional tables, figures, and methods

Contributors: JHB, ES, RØ, and GÅV planned the study. MB and GÅV performed the statistical analyses. MB drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. MB accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting criteria have been omitted.

Funding: MB was funded by the Liaison Committee for Education, Research and Innovation in Central Norway and GÅV was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (grant No 250335). BOÅ works in a research unit funded by Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU; the Liaison Committee for Education, Research and Innovation in Central Norway; and the joint research committee between St Olavs hospital and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU. The funding source was not involved in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The researchers were independent from funders and all authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: GÅV reports grants from the Research Council of Norway during the conduct of the study. MB reports grants from the Liaison Committee for Education, Research and Innovation in Central Norway during the conduct of the study; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2016/537). All participants gave informed consent before taking part in the study.

Data sharing: Data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) used in research projects is available upon reasonable request to the HUNT data access committee (hunt@medisin.ntnu.no). The HUNT data access information (www.ntnu.edu/hunt/data) describes in detail the policy about data availability. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health will consider applications for data from the tuberculosis screening programme (www.fhi.no/en/op/data-access-from-health-registries-health-studies-and-biobanks/).

Transparency: The lead author (MB) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Obesity and Overweight: World Health Organization; www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2018-08-02).

- 2. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377-96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390:2627-42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Young LR, Nestle M. Expanding portion sizes in the US marketplace: implications for nutrition counseling. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:231-4. 10.1053/jada.2003.50027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodgers A, Woodward A, Swinburn B, Dietz WH. Prevalence trends tell us what did not precipitate the US obesity epidemic. Lancet Public Health 2018;3:e162-3. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franks PW, McCarthy MI. Exposing the exposures responsible for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Science 2016;354:69-73. 10.1126/science.aaf5094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Song M, Zheng Y, Qi L, Hu FB, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Associations between genetic variants associated with body mass index and trajectories of body fatness across the life course: a longitudinal analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:506-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Song M, Zheng Y, Qi L, Hu FB, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Longitudinal Analysis of Genetic Susceptibility and BMI Throughout Adult Life. Diabetes 2018;67:248-55. 10.2337/db17-1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walter S, Mejía-Guevara I, Estrada K, Liu SY, Glymour MM. Association of a Genetic Risk Score With Body Mass Index Across Different Birth Cohorts. JAMA 2016;316:63-9. 10.1001/jama.2016.8729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodarzi MO. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:223-36. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rokholm B, Silventoinen K, Tynelius P, Gamborg M, Sørensen TI, Rasmussen F. Increasing genetic variance of body mass index during the Swedish obesity epidemic. PLoS One 2011;6:e27135. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R, et al. Differences in genetic and environmental variation in adult BMI by sex, age, time period, and region: an individual-based pooled analysis of 40 twin cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:457-66. 10.3945/ajcn.117.153643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. LifeLines Cohort Study. ADIPOGen Consortium. AGEN-BMI Working Group. CARDIOGRAMplusC4D Consortium. CKDGen Consortium. GLGC. ICBP. MAGIC Investigators. MuTHER Consortium. MIGen Consortium. PAGE Consortium. ReproGen Consortium. GENIE Consortium. International Endogene Consortium Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015;518:197-206. 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yengo L, Sidorenko J, Kemper KE, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ~700 000 individuals of European ancestry. bioRxiv 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tyrrell J, Wood AR, Ames RM, et al. Gene-obesogenic environment interactions in the UK Biobank study. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:559-75. 10.1093/ije/dyw337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center HR. HUNT Databank www.ntnu.no/hunt/databank (2017-08-10).

- 17.Norwegian Institute of Public Health Tuberculosis Register. Norwegian Institute of Public Health; https://fhi.no/nettpub/data-fra-helseregistre-store-helseundersokelser-og-biobanker/data-fra-store-helseundersokelser/landsomfattende-skjermbildeundersok/ (2018-07-02).

- 18. Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, et al. Cohort Profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:968-77. 10.1093/ije/dys095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:284-94. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nielsen JB, Thorolfsdottir RB, Fritsche LG, et al. Genome-wide association study of 1 million people identifies 111 loci for atrial fibrillation. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Use of allele scores as instrumental variables for Mendelian randomization. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1134-44. 10.1093/ije/dyt093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Felix JF, Bradfield JP, Monnereau C, et al. Bone Mineral Density in Childhood Study (BMDCS) Early Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) consortium. Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium. Bone Mineral Density in Childhood Study BMDCS Genome-wide association analysis identifies three new susceptibility loci for childhood body mass index. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25:389-403. 10.1093/hmg/ddv472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Romundstad P, Heggland J, Holmen J. The HUNT study: participation is associated with survival and depends on socioeconomic status, diseases and symptoms. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:143. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistical Yearbook 1986: Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway; www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1986.pdf (2018-06-29).

- 26.Statistical Yearbook 1987: Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway; www.ssb.no/a/histstat/aarbok/1987.pdf (2018-06-29).

- 27. Graff-Iversen S, Øien H. Kroppsmasseindeks og vektutvikling: Hvilke forskjeller er det mellom kjønnene? [Body mass index and weight change: What are the differences between sexes?] Nor Epidemiol 2000;10:87-94. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddon H, Guéant JL, Meyre D. The importance of gene-environment interactions in human obesity. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:1571-97. 10.1042/CS20160221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosenquist JN, Lehrer SF, O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Smoller JW, Christakis NA. Cohort of birth modifies the association between FTO genotype and BMI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:354-9. 10.1073/pnas.1411893111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Demerath EW, Choh AC, Johnson W, et al. The positive association of obesity variants with adulthood adiposity strengthens over an 80-year period: a gene-by-birth year interaction. Hum Hered 2013;75:175-85. 10.1159/000351742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: additional tables, figures, and methods