Abstract

Background

The implementation of interventions at-scale is required to maximise population health benefits. ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone (PA4E1)’ was a multi-component school-based program targeting adolescents attending secondary schools in low socio-economic areas. An efficacy trial of the intervention demonstrated an increase in students’ mean minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day and lower weight gain at low incremental cost. This study aims to assess the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a multi-component implementation support intervention to improve implementation, at-scale, of the evidence based school physical activity (PA) practices of the PA4E1 program. Impact on student PA levels and adiposity will also be assessed, in addition to the cost of implementation.

Methods

A cluster randomised controlled trial, utilising an effectiveness-implementation hybrid design, will be conducted in up to 76 secondary schools located in lower socio-economic areas across four health districts in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Schools will be randomly allocated to a usual practice control arm or a multi-component implementation support intervention to embed the seven school PA practices of the PA4E1 program. The implementation support intervention incorporates seven strategies including executive support, in-School Champion, teacher training, resources, prompts, audit and feedback and access to an external Support Officer. The primary trial outcome will be the proportion of schools meeting at least four of the seven physical activity practices of the program, assessed via surveys with Head Physical Education teachers at 12 and 24-months. Secondary outcomes will be assessed via a nested evaluation of student PA and adiposity at 12-months (Grade 8 students) and 24 months (Grade 9 students) undertaken in 30 schools (15 per group). Resource use associated with the implementation intervention will be measured prospectively. Linear mixed effects regression models will assess program effects on the primary outcome at each follow-up period.

Discussion

This study is one of few evidence-based multi-component PA programs scaled-up to a large number of secondary schools and evaluated via randomised controlled trial. The use of implementation science theoretical frameworks to implement the evidence-based program and the rigorous evaluation design are strengths of the study.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12617000681358 registered 12th May 2017. Protocol Version 1.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-019-6965-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Physical activity; Adolescents; School; Randomised controlled trial, implementation, multi-component, scale-up

Background

Physical inactivity is the fourth leading cause of mortality globally [1] and accrues a substantial negative economic impact [2]. Physical inactivity is a major risk factor in the development of non-communicable diseases, including coronary heart disease, type II diabetes and certain cancers [3]. Adolescence is considered a critical period, when physical inactivity adversely impacts on physical, mental and social health [4–6], and physical activity (PA) habits track into adulthood [7]. Despite the widely accepted benefits of PA during adolescence, less than 10% of adolescents globally (including Australia) accumulate sufficient PA to accrue the associated health benefits [8].

Secondary schools are a key setting to provide opportunities for PA, as they provide access to adolescents and their families for ongoing periods in a critical development phase. In addition, schools have the resources, professional skills of teachers and policies to encourage physically active lifestyles [9, 10]. School-based PA programs for children can be effective at increasing mean duration of daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), the proportion of students meeting PA guidelines, and can reduce weight, as demonstrated in a number of systematic reviews [9, 11–13]. Additionally, whilst research is currently limited, there is also some evidence suggesting a sustained impact of the school-based PA programs beyond the initial intervention period [14]. However, few programs targeting adolescents have had beneficial effects on whole day PA [15–18], particularly those targeting adolescents from lower socioeconomic background who are most at-risk of inactivity [19], and most trials targeting adolescents have not been evaluated using whole day objective PA measures [17, 18]. The implementation of comprehensive school PA programs and the use of the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework for school based programs can enhance PA outcomes [13, 20, 21], with systematic review evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions that address: the curriculum (physical education (PE) and sport) [22]; the school environment (e.g. recess and lunch activities and equipment) [23]; and the broader school community (partnerships with community PA providers and parents) [24].

Our recent cluster randomized controlled trial ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone (PA4E1)’, conducted in ten (5 intervention) secondary schools in socio-economically disadvantaged areas in Australia, demonstrated an increase in adolescent daily minutes of MVPA and a smaller increase in unhealthy weight gain over two years [15, 25]. Furthermore, the PA4E1 program delivered these improved health outcomes at a low incremental cost [15, 26]. Briefly, the PA4E1 efficacy trial consisted of seven PA practices including increased PA within physical education (PE), development of student personal PA plans, enhanced school sport programs, recess and lunchtime PA, school PA policy, links with community PA providers and links with parents. Secondary schools were supported to adopt the seven PA practices via six implementation support strategies including location of a change agent within the school one day per week.

In order to improve adolescent PA levels, the implementation at-scale of effective programs and practices, such as PA4E1, is required to achieve population level health benefits [27]. However, a review of PA interventions that have been scaled-up (fifty or more sites), identified that only six of the 16 interventions were within the school setting, and none within the secondary school setting [28]. Furthermore, a review of implementation trials [29] conducted within the school setting identified that of the 27 trials included in the review, only six interventions focused on school-based PA and had evaluated the effectiveness of methods to improve the implementation of evidence based policies, programs or practices. None of these school-based PA implementation trials had been conducted within the secondary school setting. The review concluded that whilst modest improvements in implementation appeared possible, the quality of evidence was poor and the characteristics and cost of effective implementation strategies remains relatively unknown [29]. Identifying the barriers or enablers to program implementation via formative evaluation and consultation with key stakeholders, co-development of contextually-relevant implementation support strategies and the use of theories and/ or frameworks to guide intervention design were recommended to be incorporated into future trials to maximize the likelihood of the effective of implementation.

To address this gap in the evidence base, the aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a multi-component implementation support strategy to improve implementation, at-scale, of evidence-based school PA practices of the PA4E1 program within socio-economically disadvantaged secondary schools, compared to usual school practice. The impact of the intervention on student PA levels (overall and school day MVPA) and adiposity will be assessed as secondary outcomes, in addition to the cost and cost effectiveness of implementation.

Methods/Design

Study design

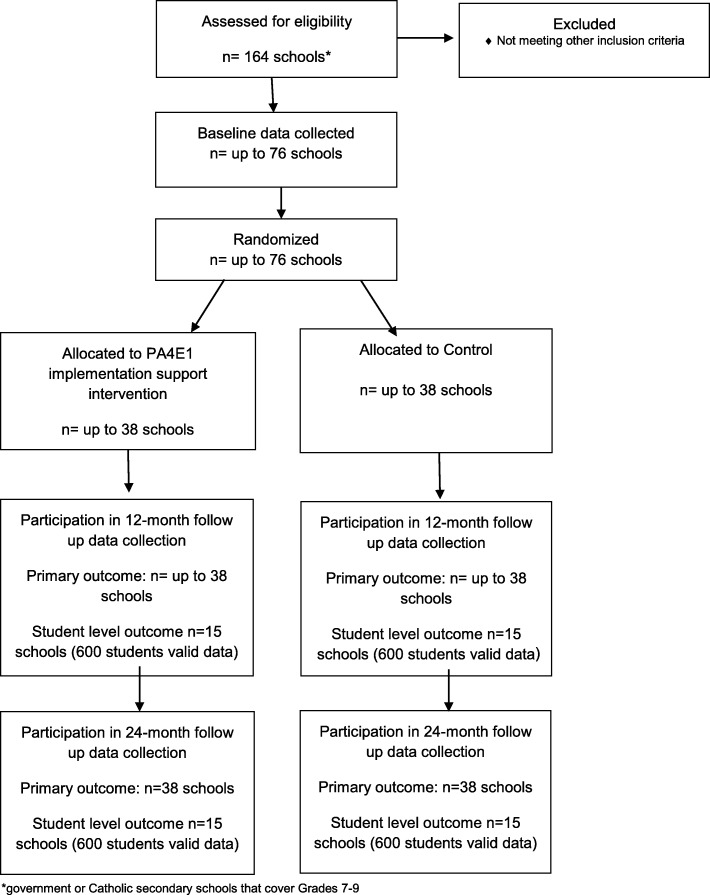

This study will employ a cluster randomised controlled design (Fig. 1). A type III hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial will be conducted combining both implementation outcomes and individual student level PA and anthropometric outcomes [30].

Fig. 1.

Consort Flow Diagram

The research will be conducted and reported in accordance with the requirements of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement [31, 32] and the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement [33]. Secondary schools will be randomised to receive either the multi-component implementation support intervention, or to a control arm (usual school practices) after baseline data collection. Assessment of school PA practices will occur at baseline, 12 months (mid intervention) and 24 months. A nested study involving 15 schools per arm will be used to evaluate student level outcomes, objectively measured student PA via accelerometers (overall minutes of MVPA per day, and minutes of MVPA within school hours) and indicators of adiposity (weight, Body Mass Index (BMI)), measured at 12 and 24 months (Fig. 1). Approval will be obtained from relevant ethics committees. The trial has been prospectively registered ACTRN12617000681358.

Setting

The study will be conducted across four local health districts in the state of NSW, Australia (Hunter New England (HNE), South Western Sydney (SWS), Central Coast (CC) and Mid North Coast (MNC)). These districts are geographically widespread and encompass major city (SWS, CC, HNE) and regional/rural areas (HNE,MNC, CC) [34].

Sample and participants

Schools

Secondary schools in NSW cater for students aged 12 to 18 years old (Grades 7–12) and operate over four terms per calendar year. Schools are required to ensure students undertake 300 h of Health and PE each year, from Grades 7 to 10 [15]. Schools should also provide opportunities for students to engage in PA through school sport, PE and other associated informal opportunities in line with NSW Department of Education policy; to provide a minimum of 150 min of planned moderate intensity PA, with some vigorous intensity, to students each week in government schools [35].

Secondary schools within the study regions that meet the following criteria will be eligible to participate in the study: (1) Government and Catholic schools; (2) enrol students in Grades 7–9; (3) located in areas classified as being disadvantaged by the SEIFA Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (suburb in lower 50% of NSW) [36]; (4) not fully selective/sports/performing arts/agriculture/boarding schools; (5) not participating in other major whole school PA trials or initiatives. Eligibility against the first four criteria will be determined from publicly available data [37], and for the remaining criteria, based on contact with schools during recruitment. The study will recruit up to 76 schools. A nested sample of 30 schools will be selected for student level data. The nested sample (n = 30) will include co-educational schools only and will be randomly selected from the main study sample.

PE teachers

At baseline, 12- and 24-months, Head and all PE teachers within each school will be invited to participate in the study assessments.

Students

All students within Grade 8 (12 month follow-up) and Grade 9 (24 month follow-up) from the schools in the nested sample (n = 30) will be invited to participate in study measures. Classes catering for students with severe physical or mental disabilities will be excluded from eligibility for collection of student measures.

Recruitment procedures

Schools

Prior to recruitment, the study will be promoted to school sector Regional Directors within the NSW Department of Education (DoE) and the relevant Catholic school dioceses, and to Government school staff in relevant regions through existing electronic communication systems (e.g. email). A list of schools deemed eligible and within strata (based on local health district (four) and school sector (two) will be assembled). The list of schools will be randomly ordered within their strata using a random number function in Microsoft Excel by a statistician not involved in contacting schools or in the study delivery [15]. A letter inviting schools will be emailed to all Principals, requesting the information be shared with the Head PE teacher. The Principal and/ or Head PE teacher will be contacted by telephone by a dedicated recruitment project officer with PE teacher training. A face-to-face or telephone meeting will be offered to outline the requirements of the study and confirm eligibility.

Teachers

Following school consent, all PE staff will be provided with a study information letter that outlines the purpose of the study and level of involvement expected.

Students (nested sub study)

Parents and students will be provided with letters outlining the study and a student consent form. The form will allow consent to be provided separately for participation in accelerometry, anthropometric measures, and student surveys. Parents will be provided with a telephone number to leave a message if they do not want to be prompted about consent or do not want their child to participate in study measurements. Parents who have not returned a consent form or left a message within two weeks will be telephoned by staff employed through the education sector who will explain the study and seek verbal consent using a standardised script [15].

As some schools will have Aboriginal student enrolments of 10% or greater [37], the study will adopt strategies to facilitate involvement of Aboriginal parents and students (with Principal permission) including: information on study letters on how to make contact with an Aboriginal member of the research team; contact with a school Aboriginal staff member to make them aware of the study and seek advice on ways the schools would usually communicate with parents; offer information to Aboriginal Education Consultative Groups (AECGs) through school channels; and having an Aboriginal staff member present on data collection days. As some schools will have high proportions of students with parents who speak languages other than English (LOTE) at home [37], the study will adopt strategies to facilitate involvement of such parents and students, including (with Principal’s permission): strategies the schools would usually use to communicate with such parents, including translation of study letters and consent forms into the major languages; adapting telephone prompting protocols to allow involvement of interpreters or school staff; and having appropriate staff members present at data collection sessions.

Randomisation

Consenting schools will be randomised to either program or control condition using a random number function in Microsoft Excel. Block randomisation (1:1) will be undertaken within the strata (four local health districts and two school sectors). Principals will be notified of their school allocation following baseline collection of school practice measures. Schools consenting to student level data (nested study) will be randomly selected within strata using a random number generator in Excel, and at stratum sizes proportional to that observed in the main study. Schools will be notified of student level measurement involvement when notified of group allocation.

Blinding

Due to the inability to blind schools and teachers to the program strategies, the study will be conducted as an open trial. Data collectors will not be informed of group allocation, however blinding cannot be assured as this may be disclosed by school staff or students. The statistician undertaking data analysis will be blinded to study group, by using treatment numerical codes only.

Program group

Theoretical framework

The Health Promoting Schools (HPS) Framework and the Social Ecological Theory underpin the seven evidence-based school PA practices used in the initial efficacious PA4E1 trial [15] and in the current trial. The Behaviour Change Wheel [39] and the Theoretical Domains Framework [40] were used to develop the multi-component implementation support strategies.

School physical activity promotion practices

Table 1 provides an overview of the school PA practices that are the focus for the current trial. The expectation is that schools use one school term for planning, and then will commence practice implementation in the second term with a focus on incoming Grade 7 students (age 12–13). Practice implementation builds over two school years (8 school terms) and is designed to be ongoing.

Table 1.

Overview of the evidence based intervention (PA4E1 PA practices) including standards required of program schools

| Physical activity practices by Health Promoting Schools domain | |

|---|---|

| Curriculum, teaching and learning | |

| 1. Quality PE lessons: PE department uses documented principles or guidelines for teachers to maximize PE quality, active learning time and student engagement in PE lessons (Program schools to use the SAAFE principles- Supportive, Autonomous, Active, Fair, Enjoyable [41]). Each PE teacher to have peer observation of a practical PE lesson, at least once a yeara. Desirable – peer observation feedback is against the department’s quality PE principles. | |

| 2. Student PA plans: Process in place for all students to set personal PA plans in Grade 7, and preferably for more grades 7–10b. Plans/process to i) include personal goals to improve or maintain activity or fitness ii) include actions and timelines to achieve goals and iii) include progress monitoring and goal review at least once within the year. | |

| 3. Enhanced school sport program: scheduled for delivery to all students in at least one Grade, between 7 and 10. A structured PA Program to be: short duration (10–12 weeks), designed to improve adolescents’ fitness and provide them with knowledge, motivation and skills to engage in a range of lifelong physical activities, includes directed practical PA sessions (Program schools to use the Resistance Training for Teens program for all Grade 7 [46]. This program includes: an interactive student seminar; structured PA program focused on muscular fitness and lifelong activities, and a smartphone app. | |

| Ethos and environment | |

| 4. Recess/ lunchtime physical activity: Supervised recess and/or lunchtime PA sessions offered to all students in Grades 7–10 at least 3 days per week. PA equipment freely available to students at least 3 days per week at recess and/or lunch. Desirable at least one organized recess or lunch activity per week targeting girls. Sessions promoted to students at least once per term. | |

| 5. School Physical Activity Policy or Procedure: inclusive of the following: school provides all students in Grades 7–10 with at least 150 min/week of MVPA during school time; school implements supportive practices to enhance all students’ PA (at least 3 of practices 1–4, 6–7 in this table)c. | |

| Partnerships and services | |

| 6. Links with community physical activity providers: Links with community PA providers- Schools promote and engage with community based PA providers to support ‘outside of school time’ activity. At least three links go beyond promotion of the provider (e.g. in newsletters) to involve an agreement, connection, partnership or engagement (e.g. out of hours sessions on school facilities, presentation by providers at school). Links communicated to students and families at least once per termd. Desirable - at least one link to not carry a cost/or be low cost in an ongoing way. | |

| 7. Communicating physical activity messages to all parents of students in Grades 7–10 at least once per term (excludes messages only about school events e.g. carnivals, or school sports timetables or results, or promotion (advertisements for) community PA providers)d. |

aProgram schools were asked to aim for peer observations once a semester

bProgram schools asked to set plans for Grade 7 at 12 months, 7 and 8 at 24 months. For outcome assessment schools reporting plans developed for at least Year 7 was considered sufficient

cProgram schools asked to include practices 1–4, 6 and 7 in their policy

dProgram schools asked to use multiple modes to promote community links and to communicate PA information to parents (eg newsletters, parent app, parent information evening)

Implementation support intervention

The multi-component implementation support intervention will consist of seven strategies delivered over two school years (Table 2). As outlined below, the implementation support intervention was developed for the original trial, then adapted for scale-up for this study.

Table 2.

Overview of the multi-component implementation support intervention

| Implementation support strategies (implemented over 8 school terms) | |

|---|---|

| 1. Obtaining executive and leadership support: School executive sign a partnership agreement outlining commitment to the program. School team/committee formed (new team or re-alignment of existing team, inclusive of in-School Champion and school executive member) to oversee program, meet at least once per term. | |

| 2. Embedded school staff: in-School Champion: An existing school PE teacher is allocated a half day per week funding to support program implementation (funding of $350AUD a fortnight provided by the Department of Health to cover half–day a week release for the duration of the intervention (8 school terms, which is 2 years)). | |

| 3. External implementation support: A Support Officer (health promotion officer, ideally with PE teacher training) co-located within the relevant local health district will make regular contact (weekly for 12 months, and as needed for the remaining 12 months) with in-School Champion via phone, email and/or face-to-face site visits. | |

|

4. Teacher professional learning: Accredited with teacher accreditation body NESA [38] • In-School Champion training – Two × 1-day face to face training sessions - hosted by PA4E1 implementation team in Term 1 and Term 5. These involve paid overnight accommodation, all meals and transport costs for those in-School Champions that attend • Quality PE training – 8 × 10-min online training videos delivered via the password protected program website focused on the SAAFE principles to be viewed by all PE teachers and discussed as a PE department, including some brief quiz questions relating to the videos • Enhanced school sport training – PA4E1 in-School Champion (or other teachers involved in delivering the program could attend 1 day face-to-face training offered through NSW Department of Education (School Sport Unit). – Resistance Training for Teens (course costs paid by project for in-School Champion), or equivalent training run by PA4E1 implementation team - Term 1–2 (not accredited). Other teachers can attend (not paid for by project) • School PA policy training – in-School Champion to undertake existing online school PA policy training run by the NSW Department of Education (Government schools only) [42] | |

|

5. Resources: Primarily distributed via the program website (PA4E1 Online) accessed by in-School Champion and other PE teachers as required: • Resources on the program website include: Overview of program presentation (Powerpoint presentation), project milestones to be achieved each term (over 8 terms, with term 1 as a planning term - this includes preparation, training and practice implementation milestones), online quality PE training (SAAFE Principle videos (6 videos - one overview and one per Principle) and worksheet, peer observation materials), student personal activity plan templates, recess and lunch resources, policy templates, examples of community PA providers, tips and frequently asked questions • Some PA equipment provided to support the delivery of recess and lunchtime PA ($100AUD equipment voucher) and enhanced schools sport program (5 Gymsticks/school) • Posters outlining Quality PE principles (SAAFE Principles [41] to be displayed in PE department by 12 months | |

| 6. Provision of prompts and reminders: emails or phone calls (occurring weekly in the first 12 months and as needed in the second 12 months from Support Officer encouraging schools to implement PA practices, complete training. Automated messages sent each term via the program website to in-School Champions about completion of teacher professional learning and completion on online termly surveys. | |

| 7. Implementation performance monitoring and feedback – termly performance monitoring surveys are completed by in-School Champions via the program website, and a feedback report on progress against milestones for each PA practice is automatically generated and sent to the school Principal, Head PE teacher and in-School Champion. The report is used by the external Support Officer to identify practices that can be achieved as ‘easy-wins’ (i.e. need only a little bit more effort to be achieved) and to guide implementation support and overcome barriers to implementing PA4E1 more broadly. |

Adaptation of the PA4E1 program school practices and implementation support intervention for implementation at scale

For this study, minor adaptations were made to the school physical activity promoting practices to address barriers raised regarding their implementation identified in the original trial. The multi-component implementation support strategies were similarly adapted to address barriers to their delivery and utility in the original trial, and to aid their implementation at-scale. The adaptations were made based on a review of existing models and factors for scaling up public health interventions [43] and a scoping review of frameworks for adapting public health interventions [44].

The key steps for adapting the implementation support strategies were undertaken iteratively, and involved: i) identifying barriers and enablers to change based on a review of the literature, focus groups with PE teachers and students, key informant interviews with school executives participating in the initial trial and Aboriginal stakeholder meetings and; ii) using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [40] and Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [39] to map the identified barriers to school implementation of PA practices and to evidence based implementation support strategies (behaviour change techniques); iii) revising the PA practices and implementation support strategies and delivery modes based on scalability (using the APPEASE criteria [45]) and iv review of the resulting adaptations by expert researchers and practitioners.

The main adaptations to the school physical activity promotion practices were: a broader focus on quality PE [41] rather than solely on ‘active PE’; and the use of a modified enhanced school sport program developed in partnership with the NSW Department of Education, designed to meet the needs of schools and supported by the Education system known as ‘Resistance Training for Teens’ [46] (rather than Program X [16]). These adaptations were made to support delivery at scale and synchronise with existing systems.

Adaptations to the multi-component implementation support intervention strategies were: 1) embedding school staff by appointing and funding an in-School Champion along with access to a local health promotion Support Officer to replace the external change agent model used in the original trial; 2) a change in the modality of teacher professional learning from face-to-face training to online where possible, and use of accredited education sector courses where possible rather than project specific learning programs, to allow teachers to include attendance at these courses within their professional accreditation [38]; 3) the provision of tools (such as PE observation forms) and resources via a program website rather than paper-based; 4) prompts and reminders and performance monitoring and feedback automated to each school (via completion of termly progress surveys) to occur via the program website rather than verbal/email prompts and manually generated feedback reports.

Additional file 1: Table S1 presents an overview of the identified barriers to school implementation and scale-up, the mapping of these barriers to the TDF [40] and BCW [39], the behaviour change techniques selected to address the barriers, and a further description of how these have been incorporated into the multi-component implementation support intervention used in the current trial.

Control group

Control schools will participate in study measures and continue delivering usual PE lessons, school sport and other PA programs and practices. PA4E1 program materials, inclusive of access to the program website will be available to these schools on study completion.

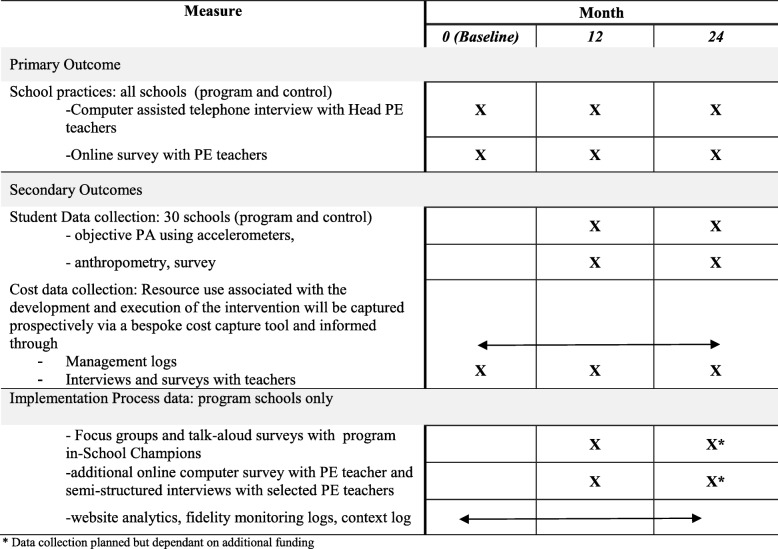

Data collection procedures and measures

An overview of data collection is shown in Table 3. The primary outcome will be the proportion of schools in each group implementing any four of the seven PA practices (the prior trial showed a significant effect on student MVPA at 12 month mid-point [47], by which time schools had implemented 4 of the 7 practices). Secondary outcomes will be the mean number of PA practices achieved, whether or not schools implement each of the seven PA practices (to determine compliance with each practice), as well as student level outcomes (objectively measured PA and adiposity indicators). Economic outcomes will include: 1) the direct cost of the multi-component implementation support intervention from multiple stakeholder perspectives; 2) average and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, subject to assessment of effectiveness, and 3) budget impact calculated from a public finance perspective.

Table 3.

Schedule of study data collection and measures

aData collection planned but dependant on additional funding

A separate process evaluation protocol will be developed and published elsewhere.

School characteristics/ Head PE teacher characteristics

Publicly available data [37] will provide information on school sector, postcode, size (total enrolments), Indigenous enrolments, and students who speak a LOTE at home enrolment for all schools approached for consent. For schools participating in the project the following characteristics will be obtained through a Head PE teacher computer assisted telephone interview: number of PE teachers and full time equivalent PE positions; language groups most commonly represented when the school has more than 10% of LOTE students.

Computer assisted telephone interviews with Head PE teachers and online surveys with all PE teachers conducted at baseline, 12 and 24 months, will ask for background information including sex, PE training, years of teaching experience, how long they’ve taught PE at their current school, and grades they teach in the current year.

School practices

Measures of the seven PA practices shown in Table 1 will be undertaken via the computer assisted telephone interviews with Head PE teachers, administered by trained interviewers. The items will be adapted from those used to collect process data in the previous PA4E1 trial [15, 25, 47] and will be forwarded by email to participants prior to the interview.

Student level variables (nested sub study)

Physical activity: Whole-day objective PA measurement will be undertaken using wrist worn Actigraph GT9X-BT or GT3X+ accelerometers [48], distributed to students at school within class, at the same time as students’ complete anthropometric measures and surveys. Accelerometers have displayed acceptable intra- and inter-instrumental reliability and provide a valid and reliable estimate of PA in young people [48, 49]. Students will be asked by trained research assistants to wear the accelerometers on their non-dominant wrist during waking hours for seven consecutive days. To improve compliance, student and/ or parent mobile phone numbers will be requested via the consent form, and a text message sent by the researchers each morning reminding students to wear the accelerometer [15]. School start and finish times that apply during the assessment period will be requested from schools.

Anthropometric data

Research assistants will be trained in measuring height and weight (used to calculate body mass index; BMI) using the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) procedures [50]. Where possible, all measurements will be taken in the morning [51]. Weight will be measured in light clothing without shoes using a portable digital scale (Model no. UC-321PC, A&D Company Ltd., Tokyo Japan) to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height will be recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Model no. PE087, Mentone Educational Centre, Australia). The physical assessments will be conducted in a sensitive manner, with student measurements taken behind a privacy screen. Body mass index (BMI) will be calculated as weight/height squared (kg/m2). Weight status will be determined using International Obesity Taskforce definitions [52].

Survey

The student survey, which will take approximately 20 min, will be undertaken to assess: student socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status, languages spoken at home, postcode of residence); which years they have attended the school; self-reported PA [53]; school PA behaviour (items from Questionnaire Assessing School Physical Activity Environment Q-SPACE [54]); autonomous motivation for PA (intrinsic motivation and identified regulation subscales of the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 2 (BREQ-2) [55]), social support for PA [56]; perceptions of school PA environment (items from or adapted from scales including Q- SPACE [54], Student Engagement in School Questionnaire [57], Teacher as Social Context questionnaire [58] controlling teacher scale [59]; and general health and well-being (KIDSCREEN 10 [60]). The survey will be completed by students at 12 and 24-months via a tablet provided by the research team.

Cost data

Cost data pertaining to the development and implementation of the intervention will be collected prospectively using a resource use capture tool. The tool, developed in MS Excel (2013), allows the input of resource use data from each of the stakeholders involved in implementing the intervention for the following cost categories: labour (health service), labour (non-health service), materials, joint costs and miscellaneous costs. Management logs routinely used by the Support Officers will inform the identification and measurement of resource use associated with the intervention. Interviews and surveys with teachers will also inform the identification and measurement of resource use from the perspective of the schools.

Implementation process outcomes

A full process evaluation protocol, with detailed aims, will be published separately. Briefly, the evaluation of implementation outcomes for the trial will be aligned to the assessment of domains recommended by Proctor et al. 2011 [61] including appropriateness, acceptability, adoption, feasibility, fidelity, penetration (reach) and sustainability. In addition, usability and engagement with the program website will be investigated [62]. A mixed-methods assessment will use data obtained from a variety of sources including PE Teacher and in-School Champion termly implementation surveys from program schools (Table 3). Appropriateness, acceptability and feasibility will be assessed using validated survey items developed by Wiener et al. [63]. Adoption (primary trial outcome) will be assessed via computer assisted telephone interviews with Head PE teachers. Fidelity and dosage (and context) will be assessed via a fidelity monitoring log [64] and a project specific fidelity checklist. Reach and sustainability will be assessed using items developed by the project team, specific to the program. Qualitative data sources will include in-School Champion focus groups and semi-structured interviews with PE teachers, as well as talk-aloud surveys relating to the engagement, usability and user experience with the program website.

The online surveys of PE teachers in program and control schools will provide data on practice barriers (Table 3).

Supporting schools with data collection

All schools will be offered half a day of teacher relief ($175AUD) at each practice data collection point (baseline, mid-point and follow-up) to reimburse the school for their time in assisting with data collection. In addition, schools participating in student data collection (nested sub study) will be offered 1.5 days teacher relief ($525AUD) at each of the 12 and 24 month collections, plus additional funding if school staff are involved in parent consent gaining calls. This will allow a school staff member to be present during the student data collection sessions. Prior to data collection days, a list of students with parental consent will be provided to the school so schools can consider whether additional research staff may be required to assist students with limited literacy.

Statistical analyses

School characteristics will be summarised separately for schools participating in the trial and those refusing participation, and for program and control schools. Student characteristics (nested sample) will also be summarised for each group for the 12 month (Grade 8) and 24 month (Grade 9) samples.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome is the proportion of schools implementing at least four of the seven PA practices [47] based on the Head PE teacher computer assisted telephone interview data. The analysis will follow intention-to-treat principles, with multiple imputation the primary method of dealing with missing data. Per protocol analyses will also be performed, based on those schools receiving the full implementation support intervention.

Differences between treatment groups in the primary outcome at 12 and 24-months will be assessed using generalised linear regression models (a separate analysis conducted for each time point). A log link and binomial distribution function will be used (a logistic link will be utilised if the analysis model fails convergence). The stratification variables will be included in the models as covariates.

Secondary outcomes

School practices

Secondary outcomes will include the mean number of PA practices achieved and the proportion of schools meeting each of the practices (Table 1). Analysis will be undertaken similarly to the primary outcome, with a normal distribution function for the mean number of practices outcome.

Student level measures (nested sub study)

Student data will be analysed if accelerometers are worn for ≥480 min per day on ≥3 days [65]. Appropriate cut-points based on emerging evidence and expert advice for wrist worn accelerometers will be used to categorize different intensities of PA [66]. Analysis will use all available data and follow the intention to treat principle. Analysis of minutes of MVPA per day (overall, within school hours as determined by school timetables) at each of the two follow-up time-points (corresponding to 12 and 24 month follow-up) will be undertaken using linear mixed models, including school level random intercept to model the clustering (30 clusters) of students within schools, and a random intercept for individuals. Analyses will adjust for demographic characteristics (sex, age, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background). Least square mean differences between intervention and control students will be presented at both time points, together with 95% confidence intervals and p-values. A similar analysis will be undertaken for anthropometry outcomes, weight, BMI, BMI z scores. Exploratory subgroup analyses will be undertaken by sex, Aboriginality and LOTE.

Economic analyses

The economic evaluation will be performed as a within-trial analysis, indicating that only costs and effects that accumulate within the trial duration are included. In this study, the prospective, trial-based economic evaluation will involve (i) resource use modelling to describe the investment required to develop and execute the implementation-intervention from all relevant stakeholder perspectives; (ii) a cost consequence analysis to identify, measure and value all associated costs and outcomes associated with the program compared to usual practice and (iii) subject to assessment of effectiveness, a cost-effectiveness analysis based on both primary school level outcome and secondary, student level outcomes.

Costs

The cost model will be based on the concept of opportunity cost, that is, the value of the benefit forgone in not employing a resource in a different use. In this analysis, market prices will be used as a proxy for this value. Labour costs will include an overhead to allow for additional costs of employment. Materials refer to non-abour cost items such as stationary (education materials) or electronic hardware or software. Joint costs are defined as those costs incurred in connection with multiple projects. For example, the maintenance costs of a website portal supporting different interventions. Capital costs refer to major one-off investments such as the purchase of additional office buildings or motor vehicles. Miscellaneous costs are considered to be those costs not easily classified into the other categories. The primary outcome from the cost model will be an estimate of the mean cost per school of implementing the intervention. Costs for each of the intervention elements will be reported separately and jointly. The analysis will adhere to cost and economic analysis guidelines [67–69]. To maintain a conservative approach to cost estimation, the non-capital implementation costs are not amortised.

Cost consequence analysis

Cost consequence analysis, the listing of all cost/benefit implications of each alternative, represents the simplest form of economic evaluation. In this analysis, where the collection of outcomes is diverse, it has value in being able to inform spending decisions by capturing the range of returns generated by the investment.

Cost effectiveness analysis

Subject to assessment of effectiveness, the trial-based evaluation will include assessment of cost-effectiveness. It has been suggested that one of the ways to improve efficiency in conducting economic evaluations of implementation interventions, is to confine the study to measures of the care process or intermediate outcomes [70]. This is the approach adopted in this study, where the cost-effectiveness outcomes, the incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICER) will be: (i) incremental cost per percent change in the proportion of schools implementing at least four of the seven PA practices, reflective of the primary trial outcome and (ii) incremental cost per unit changes in student-level outcomes (minutes of MVPA per day, % reduction in BMI and metabolic equivalent (MET) hours gained). The ICERs will be calculated as the arithmetic mean difference in cost between the intervention and usual practice arms divided by the arithmetic mean difference in effect [68, 71].

Uncertainty analysis will be conducted using parametric and non-parametric bootstrapping techniques and sensitivity analyses will be conducted to explore the robustness of the economic outcomes to any uncertainty associated with key parameters.

Budget impact analysis

A budget impact analysis considers specific requirements of policy makers taking account of local perspective and time horizons. Subject to assessment of effectiveness, the results of the cost and cost-consequence analyses will be reconfigured as a budget impact statement reflecting the costs and outcomes falling directly within specific budgets and within the usual timeframe of the budget holder.

All of the analyses will be constructed in Microsoft Excel and will adhere to international reporting standards for economic evaluations [67].

Process data

A mixed methods process evaluation based on Proctor et al. [61] will be undertaken using a descriptive analysis that will be detailed in a separate protocol.

Sample size

Based on publicly available data there are approximately 120 potentially eligible schools. Based on school consent rates in previous trials conducted by the researchers of around 65–70% [15], a sample of 76 schools (38 per arm) will provide 80% power to detect an absolute increase of ~ 35% between groups in the proportion of schools implementing at least 4 of the 7 items at 12 and 24-months (alpha 0.025 to allow for program effect at 12 or 24 months). Without prior data on baseline levels of school practices, this calculation makes the conservative assumption that 40% of schools in the usual care arm achieve this target at follow-up.

For student level variables it is estimated that a nested sample of 30 schools and a student consent rate of 65% will yield about 1200 students (600 per group) with valid accelerometer data. Using an ICC of 0.03 [15] and a standard deviation of 23 min of MVPA, will allow a 6.2 min [47] difference in the mean difference between groups at each separate follow-up to be detected with 80% power and a 2.5% type 1 error rate.

Trial discontinuation or modification

It is not anticipated that any events would occur that would warrant discontinuing the trial. Any unforeseen adverse events will be reported to the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (primary approval committee) and advice sought regarding required action. The trial registration record will be updated with any protocol modifications and any deviations from original protocol will be reported in study outcome papers.

Discussion

Implementation research is a neglected area of scientific investigation, particularly within community settings [72]. Research evaluating methods for increasing implementation of effective health policies, programs or practices represents just 1% of health promotion research publications. [73] Similarly, recent systematic reviews have identified few implementation intervention trials across a variety of community settings and health behaviours, and a scarce number of implementation trials conducted at-scale [29, 72, 74]. Rigorous trials of theoretically based implementation interventions provide the best evidence to identify solutions to bridge this evidence-practice gap and assist in providing critical information needed to support implementation at scale. Scaling up effective public health interventions is the ultimate goal, as unless interventions are delivered at scale, they offer little benefit to population health [75]. This trial is one of few large-scale, randomised trials of an intervention to improve PA practice implementation at-scale in a non-clinical setting. Using a systematic, theoretically grounded approach, this trial will provide critical information to develop more efficient and effective next generation trials focused on implementation scaling-up and scaling-out.

This will be the first implementation study at-scale of a PA intervention targeting PA practices in socio-economically disadvantaged secondary schools. The findings will inform future efforts to support schools to implement health promoting policies and programs. Further, the findings could provide a basis for supporting implementation of other evidence based policies in this setting.

Additional file

Table S1. Description of identified barriers to implementing the evidence based intervention mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel’s COM-B and the behaviour change techniques and description of the implementation support intervention. (DOCX 23 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the NSW Department of Education School Sport Unit for their advice with the study.

Funding

This project is funded by the NSW Ministry of Health, Translational Research Grant Scheme. The NSW Ministry of Health has not had any role in the design of the study as outlined in this protocol and will not have a role in data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data and dissemination of findings. RS and NN are supported by a NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1150661 and APP1132450). NN is also supported by a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; LW is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1128348), Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (101175) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; DRL is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

All study materials are available from the research team upon request to lead investigators. All data will be stored securely as per ethical requirements. All participants will be issues a unique identification number following consent for confidentiality. The final trial dataset will be stored securely and accessed only by the study statistician. The results of this trial will be disseminated via publication in peer reviewed journal, conference presentations and reports to schools and relevant health and education departments.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HPS

Health Promoting Schools

- LOTE

Language other than English

- MVPA

moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

- NSW

New South Wales

- PA

Physical Activity

- PA4E1

Physical Activity 4 Everyone

- PE

Physical Education

Authors’ contributions

RS and EC led the development of this manuscript. RS, EC and JW conceived the intervention concept. JW, RS, EC, NN, LW, PJM, DRL, KG, CO, AS, MW, NE, AB, secured funding for the study. RS, EC, NN, PJM, DRL, LW, KG, CO guided the design and piloting of the intervention. RS, EC, NN, PJM, DRL, LW, KG, CO guided the evaluation design and data collection. PR and AS contributed to the development of data collection methods specific to the cost and cost-effectiveness measures. CO developed the analysis plan. RS, EC, NN, PJM, DRL, LW, KG, CO, AS, PR, MW, NE, AB, RM, MM, JW are all members of the Advisory Group that oversee the program and monitor data. All authors contributed to developing the protocols and reviewing, editing, and approving the final version of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref No. 11/03/16/4.05), University of Newcastle (Ref No. H-2011-0210), NSW Department of Education (SERAP 2011111), Maitland Newcastle Catholic School Diocese, Broken Bay Catholic School Diocese, Lismore Catholic School Diocese, Armidale Catholic School Diocese, and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council. To gain consent, a letter inviting schools will be emailed to all Principals, requesting the information be shared with the Head PE teacher. The Principal and/ or Head PE teacher will be contacted by telephone by a dedicated recruitment project officer with PE teacher training. A face-to-face or telephone meeting will be offered to outline the requirements of the study and confirm eligibility. Following school consent, all PE staff will be provided with a study information letter that outlines the purpose of the study and level of involvement expected. To gain consent from parents and students, a letter outlining the study and a student consent form will be sent home. The form will allow consent to be provided separately for participation in accelerometry, anthropometric measures, and student surveys. Parents will be provided with a telephone number to leave a message if they do not want to be prompted about consent or do not want their child to participate in study measurements. Parents who have not returned a consent form or left a message within two weeks will be telephoned by staff employed through the education sector who will explain the study and seek verbal consent using a standardised script.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors RS, EC, NN, LW, KG, MW, NE, AB and JW receive salary support from their respective Local Health Districts. Hunter New England Local Health District contributes funding to the project outlined in this protocol. None of these agencies were involved in the peer review of this grant. RS and NN are Associate Editors for BMC Public Health. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rachel Sutherland, Email: Rachel.Sutherland@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Elizabeth Campbell, Email: Libby.Campbell@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Nicole Nathan, Email: Nicole.Nathan@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Luke Wolfenden, Email: Luke.Wolfenden@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

David R. Lubans, Email: David.Lubans@newcastle.edu.au

Philip J. Morgan, Email: Philip.Morgan@newcastle.edu.au

Karen Gillham, Email: Karen.Gillham@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

Chris Oldmeadow, Email: Christopher.Oldmeadow@hmri.org.au.

Andrew Searles, Email: Andrew.Searles@hmri.org.au.

Mandy Williams, Email: Mandy.Williams@health.nsw.gov.au.

Nicole Evans, Email: Nicole.Kajons@health.nsw.gov.au.

Andrew Bailey, Email: Andrew.Bailey@health.nsw.gov.au.

Matthew McLaughlin, Email: Matthew.Mclaughlin@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

John Wiggers, Email: John.Wiggers@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. p. 62.

- 2.Ding Ding, Lawson Kenny D, Kolbe-Alexander Tracy L, Finkelstein Eric A, Katzmarzyk Peter T, van Mechelen Willem, Pratt Michael. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–1324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee I-Min, Shiroma Eric J, Lobelo Felipe, Puska Pekka, Blair Steven N, Katzmarzyk Peter T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen Ian, LeBlanc Allana G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biddle S. J. H., Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;45(11):886–895. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eime Rochelle M, Young Janet A, Harvey Jack T, Charity Melanie J, Payne Warren R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):98. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telama Risto. Tracking of Physical Activity from Childhood to Adulthood: A Review. Obesity Facts. 2009;2(3):187–195. doi: 10.1159/000222244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, van Sluijs EM, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children's accelerometry database (ICAD). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113. 10.1186/s12966-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kriemler S., Meyer U., Martin E., van Sluijs E. M. F., Andersen L. B., Martin B. W. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;45(11):923–930. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pate Russell R., Davis Michael G., Robinson Thomas N., Stone Elaine J., McKenzie Thomas L., Young Judith C. Promoting Physical Activity in Children and Youth. Circulation. 2006;114(11):1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD007651. 10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Katz D.L. School-Based Interventions for Health Promotion and Weight Control: Not Just Waiting on the World to Change. Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30(1):253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langford R, Bonell C, Jones H, Pouliou T, Murphy S, Waters E, et al. The World Health Organization's health promoting schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:130. 10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Lai Samuel K., Costigan Sarah A., Morgan Philip J., Lubans David R., Stodden David F., Salmon Jo, Barnett Lisa M. Do School-Based Interventions Focusing on Physical Activity, Fitness, or Fundamental Movement Skill Competency Produce a Sustained Impact in These Outcomes in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review of Follow-Up Studies. Sports Medicine. 2013;44(1):67–79. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland Rachel L., Campbell Elizabeth M., Lubans David R., Morgan Philip J., Nathan Nicole K., Wolfenden Luke, Okely Anthony D., Gillham Karen E., Hollis Jenna L., Oldmeadow Chris J., Williams Amanda J., Davies Lynda J., Wiese Jarrod S., Bisquera Alessandra, Wiggers John H. The Physical Activity 4 Everyone Cluster Randomized Trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;51(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubans David R., Morgan Philip J., Callister Robin, Collins Clare E. Effects of Integrating Pedometers, Parental Materials, and E-mail Support Within an Extracurricular School Sport Intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(2):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borde R., Smith J. J., Sutherland R., Nathan N., Lubans D. R. Methodological considerations and impact of school-based interventions on objectively measured physical activity in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2017;18(4):476–490. doi: 10.1111/obr.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love Rebecca, Adams Jean, Sluijs Esther M. F. Are school‐based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta‐analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer‐assessed activity. Obesity Reviews. 2019;20(6):859–870. doi: 10.1111/obr.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stalsberg R., Pedersen A. V. Effects of socioeconomic status on the physical activity in adolescents: a systematic review of the evidence. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2010;20(3):368–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carson Russell L., Castelli Darla M., Pulling Kuhn Ann C., Moore Justin B., Beets Michael W., Beighle Aaron, Aija Rahma, Calvert Hannah G., Glowacki Elizabeth M. Impact of trained champions of comprehensive school physical activity programs on school physical activity offerings, youth physical activity and sedentary behaviors. Preventive Medicine. 2014;69:S12–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russ Laura B., Webster Collin A., Beets Michael W., Phillips David S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Multi-Component Interventions through Schools to Increase Physical Activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2015;12(10):1436–1446. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonsdale Chris, Rosenkranz Richard R., Peralta Louisa R., Bennie Andrew, Fahey Paul, Lubans David R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in school physical education lessons. Preventive Medicine. 2013;56(2):152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridgers Nicola D., Salmon Jo, Parrish Anne-Maree, Stanley Rebecca M., Okely Anthony D. Physical Activity During School Recess. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(3):320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y., Cai L., Wu Y., Wilson R. F., Weston C., Fawole O., Bleich S. N., Cheskin L. J., Showell N. N., Lau B. D., Chiu D. T., Zhang A., Segal J. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2015;16(7):547–565. doi: 10.1111/obr.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland R, Campbell E, Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Okely AD, Nathan N, et al. A cluster randomised trial of a school-based intervention to prevent decline in adolescent physical activity levels: study protocol for the ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone’ trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):57. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sutherland R, Reeves P, Campbell E, Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Nathan N, et al. Cost effectiveness of a multi-component school-based physical activity intervention targeting adolescents: the ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone’ cluster randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):94. 10.1186/s12966-016-0418-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wolfenden Luke, Milat Andrew J., Lecathelinais Christophe, Skelton Eliza, Clinton-McHarg Tara, Williams Christopher, Wiggers John, Chai Li Kheng, Yoong Sze Lin. A bibliographic review of public health dissemination and implementation research output and citation rates. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;4:441–443. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reis Rodrigo S, Salvo Deborah, Ogilvie David, Lambert Estelle V, Goenka Shifalika, Brownson Ross C. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. The Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfenden L, Nathan NK, Sutherland R, Yoong SL, Hodder RK, Wyse RJ, et al. Strategies for enhancing the implementation of school-based policies or practices targeting risk factors for chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(11). 10.1002/14651858.CD011677.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Curran Geoffrey M., Bauer Mark, Mittman Brian, Pyne Jeffrey M., Stetler Cheryl. Effectiveness-implementation Hybrid Designs. Medical Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz K. F, Altman D. G, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340(mar23 1):c332–c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D., Hopewell S., Schulz K. F, Montori V., Gotzsche P. C, Devereaux P J, Elbourne D., Egger M., Altman D. G. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340(mar23 1):c869–c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:1–9. 10.1136/bmj.i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Statistical Geography Volume 1- Australian Standard Geogrphical Classification (ASGC). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2006.

- 35.NSW Department of Education. Sport and Physical Activity Policy 2018 [cited 2018 05/12/2018]. Available from: https://perma.cc/7WDH-ZKPS.

- 36.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Technical Paper:Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes For Australia (SEIFA). Cat. no 2033.0.55.001. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2016.

- 37.Australian Curriculum, Assesment and Reporting Authority. My School is a resource for parents, educators and the community to find information about each of Australia's schools. 2019 [cited 2019 19/02/2019]. Available from: https://myschool.edu.au/.

- 38.Education Standards Authority. Guide to accreditation 2019 [cited 2019 19/02/2019]. Available from: http://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/.

- 39.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):37. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Lubans DR, Lonsdale C, Cohen K, Eather N, Beauchamp MR, Morgan PJ, et al. Framework for the design and delivery of organized physical activity sessions for children and adolescents: rationale and description of the ‘SAAFE’ teaching principles. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):24. 10.1186/s12966-017-0479-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.NSW Department of Education. School Sports Unit - Developing procedures for school sport 2019. [20/02/2019]. Available from: www.Gdurl.com/wEEE

- 43.Milat AJ, Bauman A, Redman S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):113. 10.1186/s13012-015-0301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Escoffery Cam, Lebow-Skelley Erin, Udelson Hallie, Böing Elaine A, Wood Richard, Fernandez Maria E, Mullen Patricia D. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2018;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

- 46.KENNEDY SARAH G., SMITH JORDAN J., MORGAN PHILIP J., PERALTA LOUISA R., HILLAND TONI A., EATHER NARELLE, LONSDALE CHRIS, OKELY ANTHONY D., PLOTNIKOFF RONALD C., SALMON JO, DEWAR DEBORAH L., ESTABROOKS PAUL A., POLLOCK EMMA, FINN TARA L., LUBANS DAVID R. Implementing Resistance Training in Secondary Schools. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2018;50(1):62–72. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutherland R, Campbell E, Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Okely AD, Nathan N, et al. ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone’ school-based intervention to prevent decline in adolescent physical activity levels: 12 month (mid-intervention) report on a cluster randomised trial. Br J Sports Med. 2015. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Trost Stewart G. State of the Art Reviews: Measurement of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2007;1(4):299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dollman James, Okely Anthony D., Hardy Louise, Timperio Anna, Salmon Jo, Hills Andrew P. A hitchhiker's guide to assessing young people's physical activity: Deciding what method to use. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2009;12(5):518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marfell-Jones MOT, Stew A, Carter L. International standards for anthropometric assessment. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Lower Hutt: The International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry; 2006.

- 51.Routen A. C., Edwards M. G., Upton D., Peters D. M. The impact of school-day variation in weight and height on National Child Measurement Programme body mass index-determined weight category in Year 6 children. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011;37(3):360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cole T. J. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Booth ML, Okely AD, Chey TN, Bauman A. The reliability and validity of the adolescent physical activity recall questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1986–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000038981.35052.D3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Robertson-Wilson Jennifer, Lévesque Lucie, Holden Ronald R. Development of a Questionnaire Assessing School Physical Activity Environment. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science. 2007;11(2):93–107. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Markland David, Tobin Vannessa. A Modification to the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire to Include an Assessment of Amotivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2004;26(2):191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dishman Rod K., Hales Derek P., Sallis James F., Saunders Ruth, Dunn Andrea L., Bedimo-Rung Ariane L., Ring Kimberly B. Validity of Social-Cognitive Measures for Physical Activity in Middle-School Girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;35(1):72–88. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hart SR, Stewart K, Jimerson SR. The Student Engagement in Schools Questionnaire (SESQ) and the Teacher Engagement Report Form-New (TERF-N): Examining the Preliminary Evidence. Contemp Sch Psychol Formerly Calif Sch Psychol. 2011;15(1):67–79. 10.1007/BF03340964.

- 58.Belmont M, Skinner E, Wellborn J, Connell J. Teacher as social context: A measure of student perceptions of teacher provision of involvement, structure, and autonomy support. Rochester: Univeristy of Rochester; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang Hyungshim, Reeve Johnmarshall, Ryan Richard M., Kim Ahyoung. Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101(3):644–661. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravens-Sieberer Ulrike, Erhart Michael, Rajmil Luis, Herdman Michael, Auquier Pascal, Bruil Jeanet, Power Mick, Duer Wolfgang, Abel Thomas, Czemy Ladislav, Mazur Joanna, Czimbalmos Agnes, Tountas Yannis, Hagquist Curt, Kilroe Jean. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(10):1487–1500. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Proctor Enola, Silmere Hiie, Raghavan Ramesh, Hovmand Peter, Aarons Greg, Bunger Alicia, Griffey Richard, Hensley Melissa. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perski Olga, Blandford Ann, West Robert, Michie Susan. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2016;7(2):254–267. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):65. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.TROIANO RICHARD P., BERRIGAN DAVID, DODD KEVIN W., MÂSSE LOUISE C., TILERT TIMOTHY, MCDOWELL MARGARET. Physical Activity in the United States Measured by Accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Evenson Kelly R., Catellier Diane J., Gill Karminder, Ondrak Kristin S., McMurray Robert G. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2008;26(14):1557–1565. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Husereau Don, Drummond Michael, Petrou Stavros, Carswell Chris, Moher David, Greenberg Dan, Augustovski Federico, Briggs Andrew H., Mauskopf Josephine, Loder Elizabeth. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—Explanation and Elaboration: A Report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value in Health. 2013;16(2):231–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, George WT. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 2nd ed. Oxford: University Press; 1997.

- 69.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). How to compare the costs and benefits: evaluation of the economic evidence, in Handbook series on preparing clinical practice guidelines. 2001.

- 70.Hoomans T, Severens JL. Economic evaluation of implementation strategies in health care. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):168. 10.1186/s13012-014-0168-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, Polsky D. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolfenden Luke, Reilly Kathryn, Kingsland Melanie, Grady Alice, Williams Christopher M., Nathan Nicole, Sutherland Rachel, Wiggers John, Jones Jannah, Hodder Rebecca, Finch Meghan, McFadyen Tameka, Bauman Adrian, Rissel Chris, Milat Andrew, Swindle Taren, Yoong Sze Lin. Identifying opportunities to develop the science of implementation for community-based non-communicable disease prevention: A review of implementation trials. Preventive Medicine. 2019;118:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oldenburg Brian F., Ffrench Margot L., Sallis James F. Health Behavior Research: The Quality of the Evidence Base. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14(4):253–257. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.4.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rabin Borsika A., Glasgow Russell E., Kerner Jon F., Klump M. Paula, Brownson Ross C. Dissemination and Implementation Research on Community-Based Cancer Prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(4):443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Owen Neville, Glanz Karen, Sallis James F., Kelder Steven H. Evidence-Based Approaches to Dissemination and Diffusion of Physical Activity Interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(4):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Description of identified barriers to implementing the evidence based intervention mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel’s COM-B and the behaviour change techniques and description of the implementation support intervention. (DOCX 23 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All study materials are available from the research team upon request to lead investigators. All data will be stored securely as per ethical requirements. All participants will be issues a unique identification number following consent for confidentiality. The final trial dataset will be stored securely and accessed only by the study statistician. The results of this trial will be disseminated via publication in peer reviewed journal, conference presentations and reports to schools and relevant health and education departments.