Abstract

Introduction

The physiologic importance of fast CO2/HCO3- interconversion in various tissues requires the presence of carbonic anhydrase (CA, EC 4.2.1.1). Fourteen CA isozymes are present in humans, all of them being used as biomarkers.

Area covered

A great number of patents and articles were focused on the use of CA isozymes as biomarkers for various diseases and syndromes in the recent years, in an ascending trend over the last decade. The review highlights the most important studies related with each isozyme and covers the most recent patent literature.

Expert opinion

The CAs biomarker research area expanded significantly in recent years, shifting from the predominant use of CA IX and CA XII in cancer diagnostic, staging and prognosis towards a wider use of CA isozymes as disease biomarkers. CA isozymes are currently used either alone, in tandem with other CA isozymes and/or in combination with other proteins for the detection, staging and prognosis of a huge repertoire of human dysfunctions and diseases, ranging from mild transformation of the normal tissues to extreme shifts in tissue organization and function. The techniques used for their detection/quantitation and the state-of-the art in each clinical application are presented through relevant clinical examples and corresponding statistical data.

Keywords: carbonic anhydrases, biomarker, physiology, pathology

1. Introduction

Carbonic anhydrase (CA, E. C. 4. 2. 1. 1) is a zinc metalloprotein that catalyzes the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to produce a bicarbonate ion and a proton (CO2 + H2O → HCO3- + H+). The enzyme is ubiquitously spread with the vegetal and animal kingdoms, a fact that is quite natural considering that carbon dioxide is the end product of aerobic metabolism in living organisms. It catalyzes the reaction to rates that reach diffusion-limit, thus serving the metabolic needs of various organisms, from the simplest to the most complex ones [1, 2].

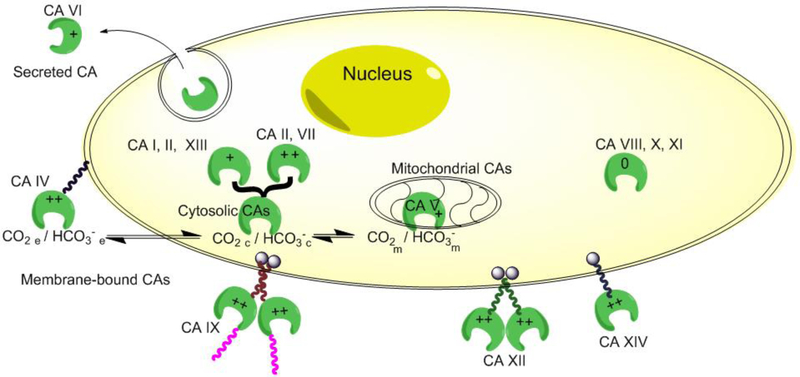

Five separate gene families encode these enzymes, namely α-CAs, β-CAs, γ-CAs, δ-CAs and η-CAs [1, 3–5]. The α-CAs are the only group found in mammals, with 14 different CA isozymes being described to date in humans (hCAs). They evolved to catalyze CO2/HCO3- interconversion in different macro- and micro-environments of the human body and consequently are involved in physiologic and pathologic processes such as respiration and CO2 excretion, pH homeostasis, secretion of electrolytes, gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and ureagenesis, bone resorption and calcification, and also in tumorigenicity. In terms of subcellular localization, one can distinguish cytosolic isozymes (CA I, CA II, CA III, CA VII, CA XIII), mitochondrial isozymes (CA VA and CA VB), membrane-bound isozymes (CA IV, CA IX, CA XII, CA XIV), and a secreted isozyme (CA VI). Besides these functional isozymes, there are three acatalytic representatives (CA VIII, CA X, CA XI) that do not contain Zn and whose function and role in the organism is not completely understood (Figure 1 and Table 1) [1, 2, 6].

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicting the 14 human CA isozymes, their relative catalytic activity and subcellular localization. For a more detailed overview, see Table 1.

Table 1.

The 14 human CA isozymes, their kinetic properties, main structural features and normal cell/tissue/organ distribution. See also Figure 1.

| CA isozyme, cellular localization | Main structural features | Kinetic properties kcat (s−1) | Normal organ/tissue location | Physiologic function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA I (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain | 2 × 105 | Red blood cells, neutrophils, corneal epithelium, lens, ciliary body epithelium of the eye, sweat glands, adipose tissue, myoepithelial cells of the epithelium of the large intestine, zona glomerulosa of the adrenal glands | Involved in equilibration of CO2/HCO3− pools maintains the pH in blood, other body fluids, facilitates the CO2 transport from tissues to lungs |

| CA II (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain | 1.4 × 106 | oligodendrocytes and epithelium of the choroid plexus of the brain, ciliary body, lens, Muller cells of retina of the eyes, acinar cells of the salivary glands, type II epithelial cells of the lung, perivenous hepatocytes of the liver, proximal tubule, distal tubule and intercalated cells of the cortical collecting ducts of the kidneys, endothelial cells, erythrocytes, platelets, neutrophils, gastric parietal cells, epithelial cells of the duodenum, intestine and colon, pancreatic ducts cells, uterine endometrial cells, epithelial cells of seminal vesicle and ductus deferens, spermatozoa, zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal glands, bone osteoclasts | Contribute to equilibration of dissolved CO2/HCO3− pools in blood and maintain the pH homeostasis in blood and in cytoplasm of cells |

| CA III (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain | 1 × 104 | skeletal muscles, adipocytes, uterus, prostate, lungs, kidneys, colon, and testis, red blood cells | Equilibrates dissolved CO2/HCO3− pools in and maintain the pH homeostasis in cytoplasm of muscle cells, confers resistance to oxidative stress of natural sources or induced via consumption of alcohol and various drugs |

| CA IV (External membrane-bound) | Catalytic domain linked to a phosphatidyl inositol glycan (GPI) membrane anchor | 1.1 × 106 | apical plasma membrane of certain capillary beds (pulmonary microvasculature, cortical capillaries, choriocapillaries of the eye, microcapillaries of skeletal and cardiac muscle), apical plasma membrane of the colon GI epithelial cells and of certain segments of the nephron, specific epithelial cells of the human reproductive tract | Involved in the equilibration of CO2/HCO3− pools in the extracellular space, where the concentration of Cl− ions is much higher than in the cytosol |

| CA VA (Mitochondria) | Catalytic domain | 2.9 × 105 | liver | Involved in gluconeogenesis, ureagenesis, lipogenesis, supply HCO3− to pyruvate carboxylase within gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis pathways, to carbamoylphosphate synthetase in ureagenesis pathway, to propionyl-CoA carboxylase and to 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase within the branched chain amino acids catabolism |

| CA VB (Mitochondria) | Catalytic domain | 9.5 × 105 | skeletal and heart muscles, kidneys, pancreas, GI tract, brain and spinal cord | |

| CA VI (Secreted in saliva and milk) | Catalytic domain | 3.4 × 105 | secreted by salivary and mammary glands | In saliva, it neutralizes the acid generated from ingested food and also from decomposition of food by bacteria living in the oral cavity, thus protecting the upper alimentary canal from acidity |

| CA VII (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain | 9.5 × 105 | mainly in the CNS, also encountered in liver, skeletal muscles, stomach, duodenum, colon | Equilibrates dissolved CO2/HCO3− pools in and maintain the pH homeostasis in cytoplasm of CNS cells and in other tissues |

| CA VIII (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain (non-functional) | N/A | Purkinje cells of cerebellum, neural cell bodies and some astrocytes, liver, lungs, heart, gut, thymus, kidneys | Influences inositol triphosphate (ITP) binding to its receptor ITPR1 on the endoplasmatic reticulum, thus modulating calcium signaling inside the cells |

| CA IX (External membrane-bound) | Dimer consisting of proteoglycan, catalytic domain, transmembrane domain, cytoplasmic domain | 3.8 × 105 | epithelium of stomach, bile duct, gallbladder duct, pancreatic duct, rapidly-proliferating normal cells of small intestine, and (low expression) in the CNS | Involved in the equilibration of CO2/HCO3− pools in the extracellular space, plays a significant role in cell survival under hypoxic conditions, over-expressed in hypoxic tumors |

| CA X (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain (non-functional) | N/A | myelin sheath in the brain | Plays an important role in myelin sheath organization in normal brain development |

| CA XI (Cytosol) | N/A | CNS: choroid plexus and pia arachnoid areas, within neural body, neurites, and astrocytes, but not within oligodendroglia, Spinal cord, GI tract (stomach, small intestine, colon), pancreas, liver, kidneys, skeletal muscles, ovaries, lymph nodes, adrenal gland, thyroid, salivary glands | Unknown | |

| CA XII (External membrane-bound) | Dimer consisting of catalytic domain, transmembrane domain, cytoplasmic domain | 4.2 × 105 | colon, rectum, esophagus, pancreas, kidneys, prostate, brain, endometrium, ovaries, testis, sweat glands of skin, breast epithelium and non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells of the eye | Involved in the equilibration of CO2/HCO3− pools in the extracellular space, enhanced expression in certain tumors |

| CA XIII (Cytosol) | Catalytic domain | 1.5 × 105 | colon, small intestine, testis, uterine cervix, endometrial glands and the thymus | Contribute to equilibration of dissolved CO2/HCO3− pools and helps maintain the pH homeostasis in cytoplasm of different cells, regulates the HCO3− ion concentration and pH homeostasis in the cervical and endometrial mucus thus maintaining the mobility of sperms and ensuring normal fertilization process |

| CA XIV (External membrane-bound) | Monomer consisting of catalytic domain, transmembrane domain, cytoplasmic domain | 3.1 × 105 | highly expressed in the kidney, brain, retina and the heart, also abundant expression in the skeletal muscle, liver, and lungs | Involved in the equilibration of CO2/HCO3− pools in the extracellular space, interacts with bicarbonate transporters, involved in acid–base balance in muscles and in other tissues in response to chronic hypoxia, in hyperactivity of the heart, and in pH regulation in the retina |

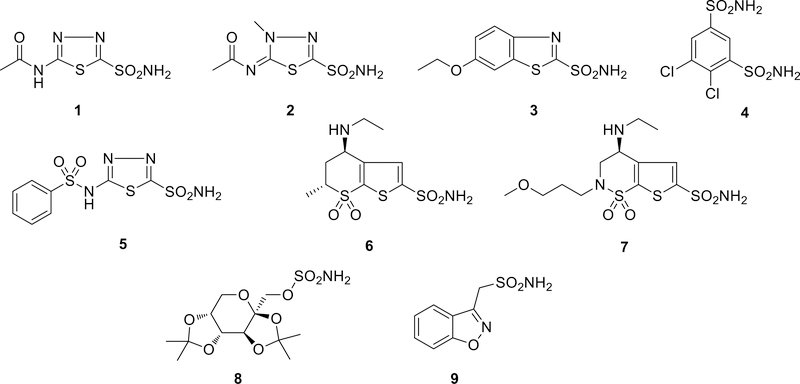

The fourteen human isozymes have a high structural homology, with key amino acid differences within their active site making them to vary quite widely in their kinetic parameters (Table 1) and also in their susceptibility to different inhibitors. Two main classes of inhibitors are currently known, the metal-complexing anions and the sulfonamides and their isosteres sulfamates and sulfamides [1, 7]. The second class was extensively used in human therapy, with sulfonamide inhibitors such as acetazolamide 1, methazolamide 2, ethoxzolamide 3, dichlorphenamide 4, benzolamide 5, dorzolamide 6 and brinzolamide 7 being used as diuretics, and in the management of edema, mountain sickness, epilepsy, and glaucoma (Figure 2) [1, 6, 8–10]. Anti-epileptic drugs topiramate 8 and zonisamide 9 are also potent CA inhibitors (CAIs). Other promising CA inhibitors are currently under advanced clinical stages in the treatment of hypoxic tumors [1, 6, 9–13] and were also used recently in the selective delivery of toxic drugs to tumors [14, 15]. Slower isozymes can be activated with CA activators, with potential applications in memory and learning enhancement [1, 16–23] The boundary between CA activation and inhibition was also revealed recently [24].

Figure 2.

CA inhibitors in clinical use, administered either systemically (compounds 1-5, 8, 9) or topically (antiglaucoma compounds 6 and 7, administered directly into the eye). One may notice that all compounds contain a primary sulfonamide/sulfamate group that binds the Zn (II) ion in the active site of CAs.

As mentioned above, CA isozymes are involved in many organs, where they are involved in different physiologic and pathologic processes and are biochemically coupled with other enzymes in various pathways. Alteration of these normal pathways in various dysfunctions or diseases trigger CA isozyme up/down-regulation from the gene level, which constitutes the main premise for using CAs as disease markers. Different diseases can also change the normal distribution of CA isozymes within the human body, leading to their appearance in large amounts in locations where they do not normally reside and/or decrease of their level in normal locations. These premises constitute the base for using CA isozymes as biomarkers for various human dysfunctions and diseases, which will be subsequently detailed in the following section.

2. Carbonic anhydrases as biomarkers for human diseases

2. 1. Carbonic anhydrase I as a disease biomarker

CA I is ubiquitously spread across body tissues. It is also present in significant amount in red blood cells (RBCs), together with CA II. Thus, CA I is five to six times more abundant than CA II in human erythrocytes, although it has only about 15% of the CA II activity. Even though CA I is the most abundant non-hemoglobin protein in RBCs, no hematologic abnormalities result from its absence. Both CA I and CA II contribute to equilibration of dissolved CO2/HCO3- pools in blood, maintain the pH blood homeostasis, and facilitate the CO2 transport from tissues to lungs [25]. The amount of free CA I protein in blood is normally very low in normal subjects but it can significantly increase in certain pathological conditions. CA I is also found in neutrophils, in the corneal epithelium, lens, ciliary body epithelium of the eye, in sweat glands, in the adipose tissue, in the myoepithelial cells of the epithelium of the large intestine, and in zona glomerulosa of the adrenal glands (Table 2) [25].

Table 2.

Distribution of isozyme CA I in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Red blood cells, neutrophils Eye (corneal epithelium, lens, ciliary body epithelium of the eye) Sweat glands, Adipose tissue, Large intestine (myoepithelial cells) Adrenal glands (zona glomerulosa) |

Immunostaining, WB | [25] | |

| Diseased | Blood/serum | |||

| • Breast cancer | MS (MRM) | [26] | ||

| • Non-small cell lung cancer | MALDI-MS, ELISA | [27] | ||

| 2DICAL-MS | [28] | |||

| • Prostate cancer | [29] | |||

| • Sepsis | Leucine-rich-alpha-2-glycoprotein | SELDI-TOF-MS, WB, ELISA | [30] | |

| • Schistosomiasis | [31] | |||

| • Diabetic nephropathy (with several other biomarkers) | Many other (complex set) | |||

In this context, Bio-Medieng Co. and Seul National University R&DB Foundation patented a method for early diagnostic of breast cancer relying on selective detection and quantification of a multiple biomarker set. The biomarker set included two apolipoproteins, fibronectin, neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein and CA I. The method relies on detection of two or more biomarkers in patient blood samples via multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) through triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. The biomarkers were detected directly via MRM or after being bound by specific antibodies raised against them, on biochips developed for this purpose. The authors claimed that the method avoids traditional biopsy and has a high diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity. Interestingly, CA I biomarker displayed the highest cancer/normal selectivity ratio of 1.6 (P < 0.001) among all biomarkers within this set [26].

Similarly, Wang et al. discovered via a combination of two-dimensional electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) that CA I isozyme was significantly elevated in the sera of stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (3.18 ± 1.27 ng/mL, n = 22, measured via ELISA) as compared to cohorts of patients having benign tumors (2.21 ± 0.71 ng/mL, n = 18) and a normal control group (2.04 ± 0.63 ng/mL, n = 18) (P = 0.001) and concluded that CA I might serve as a novel biomarker for early detection of NSCLC [27].

In a related clinical study, Takakura and collaborators discovered that CA I can serve as a potential biomarker for detection of prostate cancer (PC). The motivation of their study was that there is currently a diagnostic gray zone of PC via measurement of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. In this diagnostic uncertain zone, characterized by PSA values ranging from 4 to 10 ng/mL, biopsies reveal no evidence of cancer in 75% of these subjects, raising the need of addressing additional biomarkers. After analyzing enriched plasma proteins from 25 prostate cancer patients and 15 healthy controls using a label-free quantitative shotgun proteomics platform called 2DICAL (2-dimensional image converted analysis of liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry) the authors identified CA I by tandem MS. Independent immunological assays revealed that plasma CA I levels in 54 prostate cancer patients were significantly higher than those in 60 healthy controls, with a P = 0.022. Therefore it was concluded that CA I can potentially serve as a valuable plasma biomarker and that the combination of PSA and that CA I may enhance the accuracy of early diagnosis of prostate cancer in patients with gray-zone PSA level [28].

Besides cancer-related applications, National University Corporation Chiba University patented a method for diagnosing sepsis by measuring CA I or leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein in a blood sample. The patients were diagnosed with sepsis if the concentration of CA 1 or leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein was significantly higher than in healthy persons or non-septic kidney injury patients [29]. In another study, Kardoush et al. sought to identify novel biomarkers of human Schistosoma mansoni infection by studying serum proteins in a mouse model of schistosomiasis, followed by confirmation in chronically infected patients. Acute (6 weeks) and chronic (12 weeks) sera from S. mansoni–infected C57Bl/6 mice, as well as sera from chronically infected patients, were assessed using two proteomic platforms: surface-enhanced, laser desorption and ionization, time-of-flight mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF MS) and Velos Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Several candidate biomarkers were further evaluated by Western blot and/or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). CA I was identified among the most promising biomarkers for schistosomiasis in both mouse and human samples. Interestingly, CA I was identified as a negative biomarker, with a progressive reduction of serum CA I levels over the 12-week infection period confirmed in both species by both Western blot (murine and human: both P < 0.001) and by ELISA (human: P < 0.01) [30].

Bio-Rad and CNRS France proposed a method for the in vitro detection of an increased risk of diabetic nephropathy in a subject suffering from diabetes and being normoalbuminuric. The method involved the detection of at least two proteins selected from a biomarker set that included heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein (or fragments thereof), CA I, prothrombin (or fragments thereof), tetranectin, CD59 glycoprotein, plasma serine protease inhibitor, mannan-binding lectin serine protease 2 (or isoforms thereof), antithrombin-III, alpha-1-antitrypsin, collagen alpha-1(I) chain, alpha-enolase, histone H2B type 1-O, glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase, protein AMBP and zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein. A kit that facilitates biomarker detection was also patented (Table 2) [31].

2. 2. Carbonic anhydrase II as a disease biomarker

CA II is the most active CA isozyme, having a turnover rate for CO2 hydration approaching diffusion limit (Kcat = 1.4 × 106 s−1, Table 1), and has the widest distribution in the body, being expressed in the cytosol of cells from virtually every tissue or organ [1]. It is found in large amounts in oligodendrocytes and epithelium of the choroid plexus in the brain, in the ciliary body, lens, Muller cells of retina of the eyes, in acinar cells of the salivary glands, in the type II epithelial cells of the lung, in the perivenous hepatocytes of the liver, in the proximal tubule, distal tubule and intercalated cells of the cortical collecting ducts of the kidneys. It is also found in endothelial cells, erythrocytes, platelets, neutrophils, in gastric parietal cells, in the epithelial cells of the duodenum, intestine and colon, in pancreatic ducts cells, uterine endometrial cells, epithelial cells of seminal vesicle and ductus deferens, spermatozoa, in zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal glands and in bone osteoclasts (Table 3) [25]. The impact of this CA isozyme in the human body is best exemplified by CA II deficiency syndrome, a human autosomal recessive disorder characterized by osteopetrosis, renal tubular acidosis, and cerebral calcification. Subjects suffering from this disorder are characterized by developmental delay, short stature, cognitive defects, and bone fragility [25].

Table 3.

Distribution of isozyme CA II in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Endothelial cells, red blood cells, platelets, neutrophils | Immunostaining, WB | [25] | |

| Brain (oligodendrocytes and epithelium of the choroid plexus) | ||||

| Eye (ciliary body, lens, Muller cells of retina) | ||||

| Salivary glands (acinar cells) | ||||

| Lung (type II epithelial cells) | ||||

| GI tract (gastric parietal cells, epithelial cells of the duodenum, small intestine and colon, pancreatic duct cells) | ||||

| Liver (perivenous hepatocytes) | ||||

| Kidneys (proximal tubule, distal tubule, intercalating cells of the cortical collecting ducts) | ||||

| Reproductive tract (endometrial cells of the uterus, epithelial cells of seminal vesicle and ductus deferens, spermatozoa) | ||||

| Adrenal glands (zona glomerulosa cells) | ||||

| Bones (bone osteoclasts) | ||||

| Diseased | Blood/plasma | |||

| • Hemolysis; also hemoglobinopathies, disseminated intravascular coagulation, malaria, pulmonary hypertension, anemia | CA I | Stopped-flow Assay | [32] | |

| • Atherosclerosis | Immunostaining | [33] | ||

| • Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | Immunostaining WB | [34] | ||

Researchers from Case Western Reserve University patented an assay to detect hemolysis within a blood sample by quantifying carbonic anhydrases I and II. As mentioned above, CA I and CA II are found in large amounts in erythrocytes. When hemolysis occurs, both proteins are released in the bloodstream. However, the circulation time of the free proteins is short (t½ of about 2h) due to their removal by reticuloendothelial system after binding by a transferrin-like protein. The assay exploits the catalytic properties of CA towards the CO2 hydration reaction. It relies on mixing a human sample including red blood cells (RBCs) and/or RBC lysate with an out-of-equilibrium CO2/HCO3− solution (0.5% CO2/22 mM HCO3−, at physiologic pH = 7.2. This solution is typically made in a stopped flow spectrometer cell from two dissimilar CO2/HCO3− solutions, one containing 0% CO2/0% HCO3−, pH 7.03 and another one containing 1% CO2/44 mM HCO3−, pH 8.41, which are mixed rapidly in the measuring cell of the instrument. The resulted out-of-equilibrium solution spontaneously equilibrates and its pH raises to 7.5, being monitored by the fluorescent dye pyranine. Since the equilibration speed depends on the amount of CA present, this method allows quantification of CA in the sample, which is proportional with the extent of RBC hemolysis in vivo. It is claimed that the assay, due to its precise nature, can be utilized to assess RBC hemolysis in patients on drugs that would predispose them to hemolysis, as well as patients suffering from other conditions such as hemoglobinopathies, disseminated intravascular coagulation, malaria, pulmonary hypertension, anemia. The assay might be also useful for assessing RBC status/fragility prior to blood transfusions and CA release following lysis of a wide range of cells and tissues [32].

Clofent-Sanchez and collaborators disclosed the phage display selection and characterization of human single-chain scFv antibodies that target the vascular endothelial cell surface proteins and the sub-endothelial molecular repertoire of an atherosclerosis mouse model. In one example, CA II was identified as the target for a scFv that stained an area rich in macrophage- and smooth muscle cell-derived foam cells under endothelium and a deeper area rich in necrotic cells adjacent to the internal elastic lamina in advanced lesions. Therefore, it is claimed that anti-CA II antibodies have the potential to be utilized for imaging vulnerable plaques in atherosclerosis [33].

Parkilla and collaborators have recently revealed the use of CA II as a biomarker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). These tumors constitute the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, which are usually generated from expression of mutant KIT or PDGFRA receptor tyrosine kinase oncogenes. As a consequence, most GISTs display strong expression of KIT that allow their reliable diagnosis. However, a subset of GISTs that lacks KIT expression was evidenced and in order to distinguish them from other sarcomas/leiomyosarcomas new biomarkers are needed. After evaluating CA II expression in 175 GISTs (two cohorts including 152 and 23 cases) via Western blotting, authors observed that CA II is highly expressed in GIST cell lines, with 95% of GISTs being positive for the protein. Interestingly, the CA II expression in GISTs did not correlate with KIT or PDGFRA mutated proteins expressed by these tumors. Biomarker selectivity was good, with immunoreactivity for CA II being either absent or low in other mesenchymal tumor categories analyzed. High CA II expression was associated with a better disease-specific survival rate compared to low or no expression of the protein (Mantel–Cox test, P < 0.0001), which pleads for use of CA II as a useful biomarker in diagnosis of this tumor type among mesenchymal tumors (Table 3) [34].

2. 3. Carbonic anhydrase III as a disease biomarker

CA III is a low activity isozyme, with a Kcat of about 100 smaller than that of CA II (Table 1) [1]. This is due to particularities of its active site, which also make this isozyme much more resistant to inhibition with sulfonamides as compared with CA II and other (fast) isozymes. It can be found in large amounts in skeletal muscles (up to 8 % of the soluble protein), in adipocytes, and, in low amounts, in uterus, red cells, prostate, lung, kidney, colon, and testis (Table 4) [25, 35].

Table 4.

Distribution of isozyme CA III in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Skeletal muscles | Immunostaining, WB | [25, 35] | |

| Adipocytes | ||||

| Red blood cells (small amount) | ||||

| Lungs, kidneys, colon, uterus, testis (small amounts) | ||||

| Diseased | Liver tissue | |||

| • downregulation in liver injury due to alcoholism | CPS-1, isoaspartate (upregulated) | WB | [36, 37] | |

| Blood/serum | Myoglobin | Radioimmunoassay | [38, 39, 40] | |

| • acute myocardial infarction | H-FABP | Biochip array | [41] | |

| • acute coronary syndrome | WB, ELISA | [42] | ||

| • vasculitis | WB, MALDI-TOF | [43] | ||

| Synovial membrane | ||||

| • rheumatoid arthritis | ||||

The distinctive nature of CA III relative to other CAs is the presence of two reactive sulfhydryl groups, which can form a disulfide linkage. Through these S-containing groups, CA III can contribute to resistance to oxidative stress, of either natural sources or induced via consumption of alcohol, various drugs, etc. Prolonged ethanol feeding was shown to affect pathways that catalyze the re-methylation of homocysteine to form methionine in the liver methionine metabolic pathway, lowering hepatocyte S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) levels [44]. With alcohol consumption being a major healthcare problem, Kharbanda et al. recently examined the effects of prolonged ethanol consumption on liver enzymes, in search for biomarkers to characterize and assess liver injury. Within this study, male Wistar rats were exposed to ethanol for 4 weeks, after which liver protein were analyzed using one dimensional and two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D- and 2D-PAGE) techniques. For quantitation of CA III during exposure to ethanol, western blotting using anti-CA III antibodies was utilized. The authors observed a downregulation of CA III due to ethanol-induced biochemical stress [36]. Following this study, the same team suggested the use of CA III, carbamoyl phosphate synthase-1 (CPS-1), and isoaspartate as biomarkers of liver injury. Alcohol intake induces isoaspartate protein damage by inhibiting protein isoaspartyl methyltransferase (PIMT), an enzyme that triggers repair of isoasparate-containing proteins. In their study, the liver proteome of ethanol-fed rats was compared with the hepatic proteome of PIMT- KO mice. The rats were exposed to ethanol for either 4 weeks, or for 8 weeks. Quantification of isoaspartate-related protein damage was performed by extracting the liver and methylating with 3H-SAM using exogenous PIMT to radiolabel the isoaspartate, followed by resolving by 1D PAGE and visualization via western blotting. It was observed that nearly 98% of CA III was downregulated in the ethanol-exposed rats after 4 weeks (P = 0.009), while CPS-1 increased by 20% and 64%. The levels of CPS-1 increased with alcohol consumption, suggesting that elevated isoaspartate and CPS-1 levels and reduced CA-III levels can be associated with hepatocellular injury caused by alcoholism (Table 4) [37].

On the other hand, the particular biodistribution of CA III isozyme, its high abundance in skeletal muscles and its absence from myocardial muscle, propelled CA III as a serum marker for skeletal muscle damage and also for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), in tandem with myoglobin. In a seminal study, Vaanen et al. [38] measured serum concentrations of myoglobin (S-Myo) and CA III by specific radioimmunoassay in 26 patients with acute myocardial infarction, 14 patients with neuromuscular diseases, and six healthy subjects, before and after physical exercise. Authors have found that S-Myo was increased in infarct patients, whereas S-CA III was not altered. On the contrary,in patients with neuromuscular diseases and in healthy subjects after physical exercise, both S-Myo and S-CA III were significantly increased. Thus, the presence of both myoglobin and CA III in blood (low myoglobin/CA III ratio) indicated skeletal muscle damage, while presence of only myoglobin (or high myoglobin/CA III ratio) indicated potential AMI [38, 39, 45]. It was further proven that within the first critical 6 hours of chest pain, a key symptom of an MI, myoglobin/carbonic anhydrase III ratio is a more sensitive parameter for detection of early acute myocardial infarction than creatine kinase (CK), creatine kinase myocardial band protein (CK-MB) or myoglobin alone (P < 0.001). Myoglobin remains, though, one of the earliest cardiac markers that elevates in serum after AMI [39]. Following these studies, the ratio between serum myoglobin and carbonic anhydrase III was used to evaluate the success of thrombolytic treatments following an MI, as well as screening patients in need of rescue angioplasty post thrombolysis [40].

Building on these studies, Sawicki and collaborators investigated the use of CA III in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This is frequently a challenging task, with biomarkers playing a key role in the evaluation, immediate risk stratification and implementation of appropriate therapy in the management of patients with suspected ACS. Cardiac troponins remain the best established biomarkers in ACS for both diagnosis and risk assessment due to their high sensitivity and specificity for detecting myocardial necrosis. Unfortunately, troponin release is delayed for several hours after the onset of ischemic injury and suffer from interference by other than ACS conditions involving myocardial damage. Using a biochip array technology, authors attempted to identify potential biomarkers of ACS shortly after the symptom onset, in a study group consisting of 42 patients suspected for ACS. Although CA III failed to act as biomarker in predicting ACS conditions, the authors identified other proteins such as H-FABP that displayed a very good efficacy in early detection of ACS (90.5%), especially when used in conjunction with troponins detection. This study highlights the importance of disease biology/biochemistry and its intrinsic link with the disease biomarkers [41].

Robert-Pachot and collaborators attempted to identify new autoantibodies with potential utility for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) via immunoblotting on synovial membrane proteins. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and 2D electrophoresis, the team identified CA III as the target protein recognized by autoantibodies in RA sera. The sensitivity of these new autoantibodies for RA, using the immune-enzymatic technique, was found to be about 17%. Specificity was found to be very high when compared to non-autoimmune diseases (100%), with CA III being essentially absent from the synovial membrane of non-RA patients. However, the specificity was found to be weak (67%) when comparing the levels of the CA III autoantibodies in other autoimmune diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [43]. Saito et al. expanded the use of CA III autoantibodies quantification to the diagnostic of vasculitis - clinical syndromes characterized by blood vessel wall inflammation that lead to tissue or end organ damage. Thus, the Japanese research team tested the prevalence of anti-CA III antibodies in diverse vasculitis such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TA), using immunological assays such as ELISA and the Western Blotting technique. A significantly higher prevalence of anti-CA III antibodies was found in MPA patients versus healthy subjects (MPA, 1½3 (47.8%); healthy controls, 2/32 (6.3%); P < 0.001). Further, MPA patients positive for anti-CAIII antibodies had higher Birmingham vasculitis activity scores (BVAS - a typical disease assessment in systemic vasculitis) as compared to anti-CAIII antibody-negative patients. A commonly used diagnostic test for MPA patients is myeloperoxidase – anti‐nuclear cytoplasmic antibody (MPO‐ANCA) test, which is quite limited, with up to 40% of patients diagnosed with MPA that are negative in ANCA test. In this context, one should mention that a weak and not significant negative correlation was observed between anti-CAIII antibody levels and MPO-ANCA levels, suggesting the possibility of utilizing anti-CAIII antibodies for diagnosis of MPA in MPO-ANCA negative patients. Importantly, no significant differences were found in anti-CAIII autoantibody levels between MPA and the other primary vasculitis (Table 4) [42].

2. 4. Carbonic anhydrase IV as a disease biomarker

CA IV is a membrane-bound CA, associated to membranes via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. It is a fast isozyme (Kcat = 1.1 × 106 s−1), similarly to CA II [1, 46–48]. CA IV was found to be more resistant to inhibition by halide ions than CA II, being adapted to catalyze the CO2/HCO3- interconversion in the extracellular space, where the concentration of Cl- ions is much higher than in the cytosol. The isozyme is expressed on the apical plasma membrane of certain capillary beds, GI epithelial cells and of certain segments of the nephron. It is also expressed on specific epithelial cells of the human reproductive tract, on the plasma face of the pulmonary microvasculature, cortical capillaries, choriocapillaries of the eye, microcapillaries of skeletal and cardiac muscle, and on the microvasculature and apical plasma membrane of the colon (Table 5) [25].

Table 5.

Distribution of isozyme CA IV in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Capillary beds (apical face): • pulmonary vasculature, • cortical capillaries, • choriocapillaries of the eye, • skeletal and cardiac muscles microcapillaries |

Immunostaining, WB | [25, 47, 48] | |

| Epithelial cells of • GI tract • Reproductive tract |

||||

| Diseased | Blood/Serum | |||

| • acute myocardial infarction | MMP-9, PGLYRP1, MANSC1, QPCT, IRAK3, VNN3 | RT-PCR, DNA chip, WB, ELISA, radioimmunoassay, rocket immunoelectrophoresis | [49] | |

| • autoimmune pancreatitis | gamma-globulin and IgG | WB | [50] | |

| • apendicitis | many other (complex set) | Illumina BeadChip Arrays | [51] | |

Since CA IV is an extracellular isozyme, it can be selectively targeted by membrane-impermeant inhibitors, either charged [52–55] or polymeric [56, 57]. Some of these membrane-impermeant inhibitors were used for the detection of CA IV and other membrane-bound isozymes in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo [1, 9, 58].

Researchers from Catholic University Industry Academic Cooperation Foundation of South Korea patented biomarkers and a kit for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. The biomarker comprises a protein expressed within 4 h after the acute myocardial infarction, selected form a set comprising CA IV, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), peptidoglycan recognition protein 1 (PGLYRP1), MANSC domain-containing protein 1 (MANSC1), glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase (QPCT), interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 3 (IRAK3) and Vanin 3 (VNN3). Detection of the biomarker was done either at mRNA or at protein level in a blood sample, via RT-PCR, DNA chip and by western blot, ELISA, radioimmunoassay analysis and/or diffusion, rocket immunoelectrophoresis [49].

Nishimori et al. assessed the potential of antibodies to CA IV in diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). The authors detected serum antibodies to CA IV in patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, including AIP patients, via western blot technique. Moreover, it was found that the presence of serum antibodies against CA IV was significantly correlated with serum gamma-globulin and IgG levels in AIP patients, suggesting that CA IV can constitute a target antigen that is commonly expressed in epithelial cells of specific tissues involved in AIP and AIP-related diseases [50]. CA IV was also included as a potential biomarker for appendicitis within a relatively large pool of proteins, in a recent application from The George Washington University Corporation [51].

2. 5. Carbonic anhydrases VA and VB as disease biomarkers

Carbonic anhydrases VA and VB are two mitochondrial isozymes with medium-high activity (Kcat VA = 2.9 × 105 s−1, Kcat VB = 9.5 × 105 s−1), which are important for gluconeogenesis and ureagenesis - two metabolic pathways that depend in part on mitochondrial enzymes. They supply HCO3- to pyruvate carboxylase within gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis pathways, to carbamoylphosphate synthetase in ureagenesis pathway, to propionyl-CoA carboxylase and to 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase within the branched chain amino acids catabolism. CA VA is found mainly in the liver, while CA VB is found in skeletal and heart muscles, kidneys, pancreas, GI tract, brain and spinal cord (Table 6) [1, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65]. The important role played by these isozymes in the body was recently evidenced in the CA V-deficiency syndrome, characterized by lethargy, hyperlactatemia, and hyperammonemia of unexplained origin during the neonatal period and early childhood [66]. Following administration of carglumic acid, Van Karnebeek and collaborators successfully resolved hyperammonemia in three children suffering from this syndrome and suggested that diagnostic molecular analysis of CA VA should be considered in newborns and other persons displaying this biochemical imbalance. Moreover, the authors indicated that CA VA deficiency should be added to the list of treatable inborn errors of metabolism potentially causing intellectual disability [66].

Table 6.

Distribution of isozyme CA VA and VB in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | CA VA • liver |

[1, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63] | ||

| CA VB • skeletal and heart muscles, • kidneys, • pancreas, • GI tract, • brain and spinal cord |

||||

| Diseased | peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBC) – CA VB • pancreatic cancer • pancreatic cancer/ chronic pancreatitis |

Complex gene set Complex gene set, CA19–9 |

whole genome cDNA microarray technique whole genome cDNA microarray technique | [68] [69] |

On the other hand, due to their involvement in the anabolic processes presented above, CA VA and VB constitute major targets for anti-obesity therapy, which includes treatment with primary sulfonamide drugs with potent CA inhibitory activity topiramate 8 and zonisamide 9 (Figure 2), and their combinations with other agents [67].

Bain and collaborators identified CA VB gene and CA VB as potential biomarker for the diagnostic of pancreatic cancer (PC) via transcriptional profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBC). Thus, the authors analyzed PBMC samples from 26 PC patients and 33 matched healthy controls using whole genome cDNA microarray technique, which allowed them to identify a set of genes significantly different between PC cases and healthy controls. Within this gene set, 65 genes displayed at least a 1.5 fold change in expression versus normal expression profiles. Further unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis identified CA VB within an eight-gene predictor set that could distinguish PC patients from healthy controls with an accuracy of 79% in a blinded subset of samples from treatment naive patients, with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 75% (Table 6) [68]. In a subsequent study, the same team validated their initial findings and refined the gene set predictor (still containing the CA VB gene) on a larger cohort of 177 patients, including 95 PC patients, 35 patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) and 47 healthy subjects, using the same techniques, with the goal of differentiating resectable PC from CP. Multivariate models for PBMC gene expression were applied in order to assess if any combination of the proteins from the gene set was diagnostically superior to the main PC biomarker approved, CA19–9, which lacks selectivity and specificity. It was found that addition of four PBMC gene subset expression level (including CA VB) to CA19–9 significantly improved CA19–9’s diagnostic abilities when comparing resectable PC to CP patients (p = 0.023), thus offering a new tool for early PC diagnosis (Table 6) [69].

2. 6. Carbonic anhydrase VI as a disease biomarker

CA VI is a medium-fast isozyme (Kcat = 3.4 × 105 s−1), which is the only secreted CA isozyme in human subjects, being found in saliva and milk. In saliva, it neutralizes the acid generated from ingested food and also from decomposition of food by bacteria living in the oral cavity, thus protecting the upper alimentary canal from acidity (Table 7) [1, 25, 70].

Table 7.

Distribution of isozyme CA VI in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Saliva | [1, 25, 70] | ||

| Human milk | ||||

| Diseased | Saliva | |||

| • oral cavities | α-amylase | ELISA, zymography | [71] | |

| • enamel erosion | mucin 5B, statherine | [72] | ||

| Saliva, blood/serum | ||||

| • Sjögren’s Disease • secondary Sjogren’s syndrome |

salivary gland protein 1, parotid secretory protein | ELISA, WB | [73, 74] | |

In this context, Borghi et al. revealed a direct relationship between α-amylase and CA VI from saliva, the visible bacterial biofilm, and early childhood caries. This longitudinal study found that CA VI activity was significantly higher in saliva of children with caries (P ≤ 0.05), and that α-amylase activity was significantly higher in saliva of caries‐free children (P < 0.0001) (Table 7) [71]. In the same framework, Colgate-Palmolive Company patented a kit diagnosing the amplified predisposition to enamel erosion in a mammal based on two methods, both measuring and quantifying the concentrations of proteins critical to proper enamel formation. The first method measures concentrations of biomarkers mucin 5B, carbonic anhydrase VI, and statherine in a saliva sample from the oral cavity using specific antibodies against these targets, and compares the concentrations of these proteins to control samples. Based on the results generated with this kit, concentrations lower than 250 mg/ml mucin 5B, < 35 mg/ml of CA 6, or > 15 mg/ml of statherin indicate susceptibility to enamel erosion. The second method requires a sample of acquired enamel pellicle (AEP) from a patient and measures concentrations of total protein, statherin, and calcium concentrations in the AEP. The determined concentrations of these proteins are compared to control values generated from normal patients. Since AEP provides a protective layer on enamel, it is claimed that a reduction in the AEP concentration of [statherin] < 30 ng or of [Ca2+] < 0.001 mol/mm2 were indicative of erosion susceptibility. The authors claimed the need for this kit in identifying highly susceptible patients for proper treatment, along with further evaluation of dental erosion (Table 7) [72].

The Research Foundations of State University of New York patented a kit to identify patients with early Sjögren’s Disease (SD) - an autoimmune disease characterized by dryness of the mouth and eyes. SD can occur alone (primary SD) or can be associated with another underlying autoimmune disease (secondary Sjogren’s syndrome (SS)) such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), systemic lupus erythematosus, or polymyositis. Primary SS presents the greatest diagnostic challenge, since the symptoms are vague and non-specific, and because primary SD can trigger a wide range of systemic and extraglandular ocular complications. As the disease progresses, the lacrimal glands vital for tear production become irreversibly destroyed, leading to the symptoms observed clinically. Primary SD was associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, predisposition to hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia and various forms of lymphoma compared to the general population [73, 74]. The proposed method involves the detection of antibodies against salivary gland protein 1 (SP-1), parotid secretory protein (PSP), carbonic anhydrase VI, in saliva, blood, or serum samples, via antigen-antibody reaction quantified by immunohistochemical techniques such as Western blotting and ELISA. Individuals were identified as having Sjögren’s disease if above-mentioned antibodies or a combination of them were present in the biological sample prelevated. Furthermore, the kit, containing purified proteins salivary gland protein 1 (SP-1), parotid secretory protein (PSP) and carbonic anhydrase VI (CA VI), could be utilized to validate the absence of Sjögren’s Disease. Thus, absence of PSP and SP-1 antibodies, as well as low levels of CA 6 antibodies were considered indicative that the patient does not have Sjögren’s Disease. The value of the kit is deemed important due to its ability for early diagnosis of this disease (Table 7) [74].

2. 7. Carbonic anhydrase VII as a disease biomarker

CA VII is a fast isozyme (Kcat = 9.5 × 105 s−1), found in large amounts in the CNS, but also encountered in colon, liver, skeletal muscles, duodenum, stomach [1]. In the CNS CA VII is found in the neurons of hippocampus, together with CA II. However, CA VII is not found in glial cells, which contain just CA II. Using a novel CA VII (Car7) knockout (KO) mouse model, as well as a CA II (Car2) KO, and a CA II/VII double KO mouse models, Ruusuvuori et al. have shown that mature hippocampal pyramidal neurons are endowed with these two cytosolic isoforms that enhance bicarbonate-driven GABAergic excitation during intense GABAA-receptor activation. It appears that CA VII is predominantly expressed by neurons starting around postnatal day 10 (P10), while CA II is expressed in neurons at P20. The authors also found that CA VII mRNA is expressed in the human cerebral cortex at a very early age, that points towards CA VII being a key molecule in age-dependent neuronal pH regulation (Table 8) [75, 76]. Earlier studies from the same group have shown that CA VII acts as a molecular switch in the development of synchronous gamma-frequency firing of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in response to high-frequency stimulation [77], making CA VII an important modulator of long-term synaptic plasticity, with direct implications in memory and learning processes [17, 20, 21].

Table 8.

Distribution of isozyme CA VII in normal and pathologic tissues

On the other hand, CA VII was recently suggested as a genetic marker for detecting colorectal cancer, within a larger group of biomarkers, by the National Defense Medical Center Taiwan. Thus, Drs. Chu and Chang from the above-mentioned institution revealed an increased expression of CA VII in colorectal cancer cells vs normal counterparts and suggested the use of CA VII levels as a predictor of malignancy propensity of sampled tissues (Table 8) [78].

2. 8. Carbonic anhydrases VIII, X, XI as disease biomarkers

CAs VIII, X, XI are CA isozymes devoid of catalytic activity due to absence of one or more histidine residues needed to coordinate the Zn2+ ion in their active site. These inactive isozymes are known as CA-related proteins (CA-RPs) and their physiologic role is relatively poorly understood.

CA VIII is the most structurally-studied protein among the three CA-RPs, known to be present in the Purkinje cells of cerebellum, in the neural cell bodies and some astrocytes, and in other human tissues such as the liver, lung, heart, gut, thymus, and kidney (Table 9) [6, 79, 80, 81]. Picaud et al. revealed that the core domain of hCA VIII adopts the classical architecture of the mammalian CA enzymes, with a 10-stranded central β-sheet surrounded by several short α-helices and β-strands, resembling closely the cytosolic isozymes CA II and CA XIII [82]. It was proved that CA-RP VIII influences inositol triphosphate (ITP) binding to its receptor ITPR1 on the endoplasmic reticulum, thus modulating calcium signaling inside the cells [79, 83]. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis has also revealed the presence of CA VIII mRNA in developing human lungs and, to a lesser extent, in normal lungs, where it is expressed in the pulmonary epithelium of developing lungs, and also into the bronchial ciliated cells of adult lungs [84]. A mutations in CA-RP VIII gene (S100P) that significantly reduces the protein stability [79] has been associated with ataxia, mild mental retardation and a predisposition for quadrupedal gait in humans and with lifelong gait disorder in mice. This suggests an important role for CA-RP VIII in the normal brain [79, 85, 86]. CA-RP VIII has been recently identified as an autoantigen involved in the pathogenesis of melanoma-associated paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD), a disease characterized by the selective damage of the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum, believed to be immune-mediated (Table 9) [87].

Table 9.

Distribution of isozyme CA-RP VIII in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Brain (Purkinje cells of cerebellum, neural cell bodies, astrocytes) Lungs, Heart, Liver, gut, Thymus, Kidneys |

[6, 79, 80, 81, 84] | ||

| Diseased | Blood/Serum | |||

| • melanoma-associated paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration | WB | [87] | ||

| • Non-small cell lung cancer (squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, and adenosquamous cell carcinomas) | Northern-blot analysis, RT-PCR, immunostaining | [84] | ||

| • Colon cancer | RT-PCR, immunocytochemical analysis | [88] | ||

Importantly, CA-RP VIII was found to be strongly expressed in many lung cancers, including squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, and adenosquamous cell carcinomas. The protein was abundantly expressed in cancer cells at the front of tumor progression, suggesting an important role in non-small cell lung carcinomas progression [84]. CA-RP VIII was also significantly over-expressed, at both mRNA and protein levels, in certain colon cancers, where it potentiates the proliferative and invasive abilities, both in vitro and in vivo. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of CA-RP VIII translated into significant inhibition of cell proliferation and colony formation in a HCT116 colon cancer cell line expressing CA-RP VIII (Table 9) [88].

CA X was the second CARP reported, after CA VIII [81, 89]. Sequence analysis of cDNA libraries showed significant homology (25–57%) to other CA isozymes and revealed the lack of two histidine residues required for Zn-binding and catalytic activity similarly to another inactive CA isozyme, CA-RP XI [81]. Using monoclonal antibodies against human CA-RP X, it was found that the protein it is expressed in the cytoplasm of the myelin sheath (Table 10) [81]. Moreover, it was also found that a decreased CA-RP X level correlated well with the demyelinization of axons in the human brain in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, correlation supported by almost complete disappearance of CA-RP X protein in a mouse model of incomplete myelinization [81, 90]. These findings are supporting an important role played by CA-RP X in myelin sheath organization in normal brain development [80, 81]. Additionally, comparative analysis of the CA-RP X expression pattern from more than 17000 microarrays, revealed protein upregulation in several cancers (Table 10) [80, 91].

Table 10.

Distribution of isozyme CA-RP X in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | CNS • cytoplasm of the myelin sheath cells |

immunostaining | [81, 89] | |

| Diseased | CNS (cytoplasm of the myelin sheath - downregulation) • acute disseminated encephalomyelitis |

Immunostaining | [81, 90] | |

| Tumors (various types) | Many other (large set) | Affymetrix gene expression array | [80, 91] | |

CA XI is the last CARP, similar in structure with CA-RP X. CA-RP XI was found to be expressed in CNS, in the choroid plexus and pia arachnoid areas, within neural body, neurites, and astrocytes, but not within oligodendroglia [81]. RT-PCR-driven expression analysis, together with northern blot analysis, revealed the presence of CA XI mRNA in large amounts in the brain, followed by expression in the spinal cord, pancreas, liver, kidney, thyroid salivary gland, skeletal muscles, ovaries, small intestine, colon, stomach, lymph nodes and adrenal gland, at substantial lower levels (Table 11) [80]. Increases expression of CA-RP XI in these tissues can be correlated with risk of cancer. Thus, an elevated expression of CA-RP XI was found in 91 % of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) specimens analyzed immunohistochemically, with an elevated expression of the protein found at the periphery of GISTs. Interestingly, CA-RP VIII was also found over-expressed in the same specimens, although less frequently – only 59% of all cases. The correlation between expression patterns of CARP XI and GIST was also confirmed in vitro, in the GIST cell line GIST-T1. Through RT-PCR, Southern blot, and immunocytochemistry, it was confirmed that ectopic expression of CA-RP XI in GIST-T1 cells induced cell proliferation and invasion (Table 11) [92]. Similarly to CA-RP X, upregulation of CA-RP XI mRNA was linked to several cancers and pathological conditions via microarrays screening (Table 11) [80, 91].

Table 11.

Distribution of isozyme CA-RP XI in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Brain • choroid plexus and pia arachnoid areas, • neural body, neurites, and astrocytes Spinal cord, GI tract (stomach, small intestine, colon) Pancreas, Liver, Kidneys, Skeletal muscles, Ovaries, Lymph nodes, Adrenal gland, thyroid, salivary glands |

[80, 81] | ||

| Diseased | Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | CA-RP VIII | Immunostaining, RT-PCR, Southern blot, immunocytochemistry | [92] |

| Other tumors (various types) | Many other (large set) | Affymetrix gene expression array | [80, 91] | |

| Gliomas, astrocytomas, oligodendroglial tumors | CA II, CA IX, CA XII | Immunostaining | [93] | |

Karjalainen et al. [93] recently assessed the expression of CA-RPs VIII and CA-RPs XI in human astrocytomas or oligodendroglial tumors and analyzed their association to different clinicopathological features. The authors also attempted to correlate the expression of these CA-RPs with the expression of other CA isozyme traditionally associated with tumors, namely the cytosolic CA II, and the membrane-bound CA IX and CA XII. An analysis of the two CA-RPs in 405 gliomas of different grades via immunostaining revealed that CA-RP VIII was expressed in 13% of the astrocytomas and in 9% of the oligodendrogliomas, while CA-RP XI was expressed in 7% of the astrocytic and in 1% of the oligodendroglial tumor specimens. The benign tumors such as pilocytic astrocytomas did not express CARPs at all. Another finding was that the presence of these CARPs was associated with a more benign behavior in grade II-IV astrocytomas (both CA-RP VIII and XI), and in oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas (CA-RP VIII only). No correlation was found between CA-RP VIII expression and the expression of other CAs and between the expression of CA-RP XI and CA VII, CA IX, and CA XII. Interestingly, the expression of CA-RP XI was found to be positively correlated with the cytoplasmic CA II in astrocytic tumors (P = 0.037). It was concluded that CA-RPs do play a role in tumorigenesis of diffusively infiltrating gliomas through an unknown mechanism that requires further investigations (Table 11) [93].

2. 9. Carbonic anhydrases IX as a disease biomarker

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) is a medium-fast (Kcat = 3.8 × 105 s−1), membrane-bound, isozyme of carbonic anhydrase. It is a transmembrane isozyme, possessing an N-terminal proteoglycan domain, the catalytic domain, a single-pass transmembrane region, and an intracellular tail [1, 94, 95]. Mass spectrometry experiments showed that CA IX protein is dimeric, possessing an intermolecular disulfide bond between two similar Cys residue located on separate CA catalytic domains [96]. CA IX normal expression is limited to the epithelium of stomach, bile duct, gallbladder duct, pancreatic duct, rapidly-proliferating normal cells of small intestine, and, to a lower extent, to the CNS, where it can be found mainly in the ventricular-lining cells and in the choroid plexus (Table 12) [94, 97, 98]. However, CA IX is strongly upregulated in many hypoxic tumors, where it plays a significant role in tumor cell survival, invasiveness and metastasis [94]. Fast-growing tumors are becoming quickly hypoxic, triggering the stabilization of HIF-1 in cytoplasm, followed by relocation to the nucleus, where it triggers the expression of a plethora of genes encoding proteins involved in cell survival and proliferation under hypoxic conditions, including CA IX [1, 94]. Hypoxic tumor cells rely on glycolysis as the main source of energy production, and produce large amounts of acidic byproducts pyruvate and lactate. CA IX plays a defensive role towards pH regulation inside the tumor cell, moving protons from cytoplasm to the external milieu via reversible HCO3- dehydration/CO2 hydration, in tandem with cytosolic CA isozymes such as CA II [1, 94, 99–102]. Giving its central role in promoting tumor cell survival, CA IX expression is upregulated in many types of cancers including breast, kidney, colon, ovarian, head-and-neck, pancreatic and lung cancer [1, 94, 98, 103]. This expression pattern renders CA IX a potential biomarker and a compelling therapeutic target for the detection and treatment of hypoxic solid tumors (Table 12) [1, 6, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 56, 100, 102, 104–113].

Table 12.

Distribution of isozyme CA IX in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | GI tract • epithelium of stomach, bile duct, gallbladder duct, pancreatic duct, • rapidly-proliferating normal cells of small intestine |

Immunostaining | [94, 96, 97, 98] | |

| CNS • ventricular-lining cells • choroid plexus |

Immunostaining | [94, 96, 97, 98] | ||

| Diseased | Tumors • renal cell carcinoma, colon, lung, breast, ovarian, head-and-neck, pancreatic cancer, transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract |

Imaging/detection via CA IX antibodies and CA IX inhibitors, Immunostaining, WB | [1, 6, 9, 11, 100, 102, 110, 111, 112, 113] [114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119] |

|

| Blood • renal cell carcinoma • non-small cell lung cancer |

ELISA ELISA |

[120] [117] |

||

| Urine • transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract |

WB | [121] | ||

In this context, Hulick et al. investigated the relationship between the CA IX blood levels and the progression of renal cell carcinoma (RCC). They utilized an anti-CA IX antibody (M75)-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to determine CA IX levels in blood obtained before and after nephrectomy for clinically localized disease in patients with clear cell RCC, papillary and chromophobe RCC, oncocytoma, or benign kidney lesions. Comparison with CA IX levels in blood drawn from normal control individuals revealed a significant reduction in the blood levels of CA IX (P < 0.006), after nephrectomy for localized disease, in the majority of patients with clear cell RCC (57%). On the other hand, blood samples from patients with non-clear cell RCC, a benign disease, or those having undergone de-bulking nephrectomy for metastatic disease did not show a decrease in CA IX levels after nephrectomy. The follow-up measurements of CA IX levels in a small group of patients indicated that rising CA IX levels directly correlate with disease progression (Table 12) [120].

In another study, Genega et al. investigated the level of expression of CA IX in primary and metastatic renal neoplasms and correlated this expression to the grade and type of the tumor. They evaluated the CA IX expression in 366 cancer cases, among which 317 cases were primary and 42 cases were metastatic tumors. The cases were divided based on tumor type as follows: 308 renal cell carcinomas (186 clear cell, 52 papillary, 35 chromophobe, 20 unclassified, 15 Xp11.2 translocation), 26 oncocytomas, 2 metanephric adenomas, 1 urothelial carcinoma, 1 mixed epithelial and stromal tumor, 1 angiomyolipoma, 21 unknown and 6 with more than one tumor type. CA IX immunostaining was carried out using the mouse monoclonal antibody MN-75 [122] on one representative section of tumor from each case. Samples were scored based on the staining intensity of the cytoplasmic membrane and the percentage of positive cells such that samples in which > 85% of tumor cells stained for CA IX were considered as high CA IX expressing tumors, whereas those in which ≤ 85% of tumor cells stained for CA IX were considered as low CA IX expressing tumors. Their results showed a correlation between high CA IX expression and tumor type (clear cell versus non-clear cell). Moreover, a statistically significant association between the expression and grade in primary clear cell carcinomas was found, thus supporting the evidence that CA IX could be used as an immunohistochemical marker to reliably distinguish between different tumor types and if its expression is correlated to RCC grade (Table 12) [114].

In a more comprehensive study, Luong-Player et al. examined the level of expression of CA IX in different type of malignancies as well as in normal tissues. The study included 1,551 cases encompassing 1,160 malignant tumors, 69 benign neoplasms, and 322 normal tissues. Immunohistochemical staining of CA IX was performed using a mouse monoclonal antibody, clone MRQ-54. Cytoplasmic membrane staining was regarded as a positive result. The staining intensity was graded as weak or strong. The distribution of staining was recorded as negative (< 5% of tumor cells stained), 1+ (5%−25%), 2+ (26%−50%), 3+ (51%−75%), or 4+ (> 75%). The results revealed the overexpression of CA IX in clear renal cell carcinoma (CRCC) with 90% of low-grade CRCCs and 86% of high-grade CRCCs cleared showing CA IX overexpression. On the other hand, all chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (ChRCC) and renal oncocytomas were CA IX negative. Moreover, 90 % of the intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) cases showed a significant level of CA IX overexpression, while only 15 % of the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases were CA IX positive. All carcinomas of the breast, thyroid, or prostate as well as normal renal tubules except one case showed no staining and were reported as CA IX negative. These findings validated CA IX as a potential diagnostic biomarker in differentiating CRCC from ChRCC and oncocytoma. The authors also provided evidence that CA IX can be used to distinguish low-grade CRCC from normal renal tubules, which can be challenging in small biopsy specimens or fine-needle aspirations. Moreover, these findings rendered CA IX as an adjunctive immunohistochemical tool in separating cholangiocarcinomas from HCC and identify the role of CA IX as an important marker in separating CRCCs from other lesions with clear cell features, such as clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and uterus (Table 12) [115].

Besides serving as a diagnostic biomarker for renal carcinomas, CA IX is also considered to be a potential diagnostic epitope for colorectal cancer. In this context, Korkeila et al. evaluated the level of CA IX expression in tumor samples obtained from 166 rectal cancer patients treated by preoperative radio- or chemo-radiotherapy or surgery only. Operative samples harvested from non-irradiated patients served as controls. The level of CA IX expression was evaluated using a rabbit polyclonal antibody for CA IX by three different strategies - either positive or negative, proportion of positivity and staining intensity. The results of immunohistochemical analysis were also validated by western blotting analysis. Results revealed that CA IX staining was positive in 44%, weak in 15% and moderate or strong in 29% of the operative samples. The proportion of CA IX positive staining and staining intensity were directly correlated. Moreover, the staining intensity of CA IX in the operative samples was shown to be significantly dependent on the treatment categories. The long-course radiotherapy group samples were CA IX positive with moderate/strong staining intensity. On the other hand, the chemo-radiotherapy group samples were mostly CA IX negative, implying the synergistic effect of chemotherapy in enhancing the treatment outcome. This reflects the prognostic significance of CA IX in rectal cancer, suggesting that strong staining intensity of CA IX is an adverse prognostic factor in rectal cancer (Table 12) [116].

Furthermore, CA IX has proven to be a predictive prognostic tool for lung adenocarcinoma as shown by Nakao and collaborators [123]. In this study, the level of CA IX expression was evaluated immunohistochemically in cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) and cancer cells in 158 resected cases of lung adenocarcinoma. CA IX staining was done using a rabbit polyclonal antibody for CA IX and the samples were considered positive for CA IX if cell membrane and cytoplasmic staining was present in > 10 % of the CAFs and > 20 % of the cancer cells. The results revealed that CA IX expression by cancer cells was observed in 25.3% of the cases, while its expression by stromal spindle cells that were morphologically identified as fibroblasts was observed in 24.7% of the cases. Moreover, CA IX expression by both cancer cells and fibroblasts was observed in 11.4% of the total cases. Interestingly, all cases that were positive for CA IX expression by cancer cells or fibroblasts were cases of invasive carcinoma (Table 12) [123].

In the same context of using CA IX as a biomarker for lung cancer, Ilie et al. investigated the expression of CA IX in tumor tissue and/or plasma of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). They generated tissue microarrays of 555 NSCLC tissue samples for quantification of CA IX expression. The plasma level of CA IX was determined by ELISA in 209 of these NSCLC patients and in 58 healthy individuals. The CA IX tissue immunostaining and plasma levels were correlated with clinicopathological factors and patient outcome. High tissue expression of CAIX was correlated with shorter overall survival (OS) (P = 0.05) and disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients (P = 0.002). It is found that the plasma level of CA IX was significantly higher in patients with NSCLC than in healthy individuals (P<0.001) and associated with shorter OS (P < 0.001) and DSS (P < 0.001), mostly in early stage I+II NSCLC. Besides, high CA IX tissue expression (P = 0.002) was associated with poor prognosis in patients with resectable NSCLC. In addition, a high plasma level of CA IX was an independent variable predicting poor OS (P < 0.001) in patients with NSCLC. The authors concluded that high expression of CA IX in tumor tissue is a predictor of poor survival, and a high plasma level of CA IX is an independent prognostic biomarker in patients with NSCLC, particularly in early-stage I+II carcinomas (Table 12) [117].

In another study, Kim et al. analyzed the level of CA IX expression associated with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNETS). The level of expression was investigated immunohistochemically in 164 well-differentiated PanNETs and 23 incidentally identified pancreatic neuroendocrine microadenomas, using a primary antibody directed against CA IX. Moderate to strong staining of CA IX in > 10% of tumor cells was considered as positive. Results revealed that CA IX expression was observed in normal islets, while neuroendocrine microadenomas and small (< 1 cm) PanNETs showed loss of CA IX expression. CA IX expression was observed in 38 (23%) and 36 (22%) of PanNETs, respectively. CA IX expression was associated with larger size (p = 0.001), higher grade (p < 0.001), higher pT category (p < 0.001), lymph node (p = 0.003) and distant (p = 0.047) metastases, higher AJCC stage (p < 0.001), and lymphovascular (p < 0.001) and perineural (p = 0.002) invasion. Moreover, PanNET patients with CA IX expression had a shorter recurrence-free survival (5-year survival rate 47%) than those without CA IX expression (76%) by univariate (p = 0.001) but not multivariate analysis. These results suggested that CA IX expression was found mainly in normal islets, while neuroendocrine microadenomas and small PanNETs showed loss of CA IX expression. CA IX was found to be expressed in larger PanNETs, associated with aggressive clinicopathologic factors and poor recurrence-free survival by univariate but not multivariate analysis. The value of CA IX expression as prognostic marker for PanNET patients needs further studies (Table 12) [118].

Furthermore, CA IX expression was associated with transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary tract. Hyrsl et al. studied the expression level of cell-associated CA IX in histological sections of the transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary tract and of the soluble form of CA IX (s-CAIX) shed by the tumor into the serum and urine of TCC patients. A number of 23 patients with TCC or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and sixteen healthy persons as controls were enrolled in this study. Soluble s-CAIX were detected in urine samples using Western blots, as a double band at 50 and 54 kDa. In most cases, the presence of s-CA IX in the urine correlated with CA IX expression in the tumor. On the other hand, s-CA IX did not exceed the normal level in the serum of TCC patients. s-CAIX was found to be presented in the urine of patients with TCC of the urinary bladder and renal pelvis, allowing the detection of tumors in approximately 70% of the patients. In conclusion, the authors suggested that a simple, rapid and sensitive test, monitoring s-CA IX levels in urine can be developed for the early detection of relapse in patients following transurethral tumor resection (Table 12) [121].

Chu et al. analyzed the expression of CA IX in patients with invasive breast ductal carcinoma and attempted to correlate the expression level of this CA isozyme with histological grade, lymphatic metastasis, TNM stage and patient prognosis. Invasive breast ductal carcinoma is characterized by a heterogeneously hypoxic environment and therefore it is not surprising that the expression of CA IX was detected by non-biotin immunohistochemical method in 29 (29.0%) of 100 invasive breast ductal carcinomas investigated. The CA IX expression was found to be significantly correlated to lymph node metastasis (P = 0.015), TNM stage (P = 0.018) and overall survival rate (P = 0.0001) or disease-free survival rate (P = 0.0001), but not to age (P = 0.375), tumor size (P = 0.288) and histological grade (P = 0.526), thus proving CA IX as an independent prognostic factor (P = 0.002). It was also concluded that the hypoxic microenvironment in invasive breast ductal carcinoma might be associated with aggressive tumor phenotype of this cancer type (Table 12) [119].

2. 10. Carbonic anhydrases XII as a disease biomarker

CA XII is another medium-fast (Kcat = 4.2 × 105 s−1), membrane-bound isozyme, similar in general structure with CA IX. It contains the N-terminal CA domain, an α-helical transmembrane region, and a short intracytoplasmic tail, as does CA IX, but it does not have a proteoglycan domain. Similarly with CA IX, it forms a dimer with the two active sites oriented towards the extracellular milieu. The extracellular catalytic domain contains two asparagine residues that can be glycosylated, while the transmembrane domain contains the GXXXG and GXXXS motifs, which are involved in the dimerization of the protein polypeptide. The cytoplasmic domain at the C-terminus contains two potential sites for phosphorylation in the 29 amino acid sequence [1, 124–128].

CA XII is overexpressed in many cancers, including renal, breast, non-small cell lung cancer, etc [126, 127]. In fact, the protein was discovered in a cDNA library from a human renal cell carcinoma (RCC) using the serological expression screening method [124] and was also cloned from the same cells using the RNA differential display technology [127]. In RCC, CA XII expression has been found mostly in clear cell carcinomas and oncocytomas. In clear cell carcinomas, the level of CA XII expression correlates with the histological grade of the tumor [126, 129, 130]. Both CA IX and CA XII are overexpressed under hypoxic conditions [131], but the level of expression depends on the tissue type. In contrast to CA IX, CA XII is highly expressed in many normal tissues including colon (but not small intestine), kidney, prostate, endometrium, rectum, esophagus, brain, pancreas, ovary, testis, sweat glands of skin, breast epithelium and non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells of the eye (Table 13) [126, 127, 132]. Importantly, the expression patterns of CA IX and CA XII are different and they overlap only marginally [132].

Table 13.

Distribution of isozyme CA XII in normal and pathologic tissues

| Status | Biodistribution | Other biomarkers co-assessed | Method of assessment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | GI tract | Immunostaining | [126, 127, 132] | |

| • esophagus | ||||

| • colon (but not small intestine), | ||||

| • rectum | ||||

| Pancreas, | ||||

| Kidneys, | ||||

| Prostate, | ||||

| Brain, | ||||

| Endometrium, | ||||

| Ovaries, testis, | ||||

| Sweat glands of skin, | ||||

| Breast epithelium, non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells of the eye | ||||

| Diseased | Tumors | CA IX (in some) | cDNA libraries screening, PCR, | [124, 126, 127, 131, 133] |

| • kidney (renal cell carcinoma) | Northern blotting | [126, 129, 130] | ||

| • breast cancer | [134] | |||

| • lung cancer | Immunostaining | [135] | ||

| • cervical cancer | Immunostaining, tissue microarrays | [136] [137] |

||

| • ovarian cancer | CA IX | Immunostaining | ||

| Immunostaining | [138] | |||

| • colorectal cancer | CA IX | [139, 140] | ||

| CA IX | Immunostaining | [141, 142] | ||

| • brain cancers | CA IX, CA II | Immunostaining | ||

| Immunostaining, WB, RT-PCR | [143] | |||

| • esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Immunostaining | [144, 145, 146, 147] | ||

| Blood (mutated version) | ||||

| • Cystic fibrosis-like diseases | Genotyping, gene sequencing, RT-PCR, | [148, 149] | ||

| • Pancreatitis | [126, 148, 150] | |||

| • Sjogren’s syndrome | Large set of biomarkers considered | Immunostaining | [151, 152] | |

| Nucleus pulposus of vertebrae | ||||

| • Chronic back pain | CA IV, CA IX | cDNA microarray analysis, RT-PCR, immunostaining, flow cytometry | [153] | |

| Eyes (non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells) • Glaucoma |

Immunostaining, Northern blotting | |||

As mentioned above, CA XII expression has been detected in many other tumors, besides RCC. Dinona (Seoul, KR) patented an antibody recognizing and binding to CA XII-expressing tumors for diagnostic purposes. The antibody binds a non-catalytic region, located at an N terminus of CA XII and can also be used in the alleviation, prophylaxis, therapy or CA XII-positive solid tumors [133].

In breast cancer CA XII expression is controlled by the estrogen receptor (ER) and is associated with positive ER alpha receptor status [126, 134, 154]. Immunohistochemistry assessment of CA XII expression in a series of 103 cases of invasive breast cancer determined that CA XII was present in 75% of tested patients and was associated with lower grade (P = 0.001), positive estrogen receptor status (P < 0.001), and negative epidermal growth factor receptor status (P < 0.001). CA XII expression was associated with an absence of necrosis (P < 0.001), and CA XII positive tumors were associated with a lower relapse rate (P = 0.04) and a better overall survival for the patient (P = 0.01). It was concluded that CA XII is a biomarker that is associated with a better prognosis in an unselected series of invasive breast carcinoma patients (Table 13) [134].