Abstract

Objective.

Young adults attempt suicide at disproportionately high rates relative to other groups and demonstrate high rates of sleep disturbance. A study has yet to prospectively evaluate disturbed sleep as an acute indicator of risk using an objective index of sleep. We investigated objective and subjective parameters of disturbed sleep as a warning sign of suicidal ideation (SI) among young adults over an acute period.

Method.

A longitudinal study across a 21-day observation period and three time-points. Fifty participants were prescreened from N=4,847 (February 2007-June 2008), based on suicide attempt (SA) history and recent SI. Actigraphic and subjective sleep parameters were evaluated as acute predictors of SI (Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation), adjusting for baseline symptoms. Hierarchical regression analyses were employed to predict residual change scores.

Results.

Ninety-six percent of participants endorsed an SA history. Mean actigraphy revealed objectively-disturbed sleep parameters; 78% and 36% endorsed clinically-significant insomnia and nightmares. Controlling for baseline suicidal and depressive symptoms, actigraphy and subjective sleep parameters predicted SI residual change scores at 7- and 21-days follow-up (p<.001). Specifically, actigraphy-defined variability in sleep timing, insomnia, and nightmares predicted increases in SI (p<.05). In a test of competing risk factors, sleep variability outperformed depressive symptoms in the longitudinal prediction of SI across time-points (p<.05).

Conclusion.

Objective and subjective sleep disturbances predicted acute SI increases, independent of depressed mood. Self-reported insomnia and nightmares, and actigraphically-assessed sleep variability, emerged as acute warning signs of SI. This highlights the potential utility of sleep as a proposed biomarker of suicide risk and therapeutic target.

Keywords: Suicide, Sleep disturbances, Actigraphy, Insomnia, Nightmares

INTRODUCTION

Suicide represents a preventable public health problem and global disease burden, accounting for nearly 1 million deaths annually worldwide.1 The Institute of Medicine furthermore estimates an additional 25 attempts (100–200 for youth) for every suicide death.2 Calls to Action by the U.S. Surgeon General consistently highlight the need to identify risk factors to enhance surveillance and treatment development to prevent suicide, particularly among youth.3 In general, selective interventions for suicide as an indication remain either alarmingly scarce, unacceptable (i.e., based on attrition), or inaccessible to those highest in need.

Sleep disturbances are among the top warning signs of suicide by SAMHSA,4 and preliminary research suggests they may confer risk for suicidal behaviors.5 Even so, numerous methodological limitations, often inherent to the study of suicide, constrain the impact of such findings.6,7 These include the frequent use of retrospective and cross-sectional study designs, chart review or historical assessment of suicidal symptoms, and reliance on single-item evaluations of suicidal symptoms (e.g., from depression inventories) versus validated instruments.7 Finally, investigations often fail to control for the confounding influence of existing psychopathology, particularly depression severity.7 Because sleep and suicidal symptoms are diagnostic criteria for depression,8 and among the strongest predictors of suicide risk,6,9 this is crucial to delineating independent risk for suicidal behaviors (i.e., versus representing a mere correlate of depression).

Evaluation among young adults is motivated by the shared prevalence of sleep disturbance and suicide risk during this developmental period. Sleep disturbances are overrepresented among young adults,10,11 and suicide is the second leading cause of death among those aged 19–24.12 Relative to other risk factors, sleep appears visible as a warning sign. In a psychological autopsy study13 of 140 adolescent suicide decedents and 131 community-matched controls, sleep problems were visible to friends and family in the weeks and months prior to death. Even after adjustment for depression, disturbed sleep predicted up to a 10-fold greater risk for suicide compared to controls. Population-based studies of adolescents also identify sleep in association with suicidal behavior,14 controlling for depressive symptoms.15

According to a systematic review of studies addressing the methodological issues above, research supports sleep disturbances (e.g., insomnia, poor sleep quality, nightmares) as an independent risk factor for suicide ideation, attempts, and fatalities—adjusting for depression— across investigations diverse in design, samples, and assessment techniques.7 This includes self-reported insomnia and fatigue as correlates and risk factors for suicide ideation and attempts and poor subjective sleep quality as a risk factor for suicide death in a longitudinal, epidemiological study.16 Given the inherent costs and methodological challenges to assessing sleep objectively, within large-scale studies of suicide, reports have primarily relied on surveyed sleep complaints versus objective sleep parameters.5,7 By comparison, objective assessment of sleep in association with suicidal behaviors has received less attention in suicide research. Indeed, of ten total studies conducted7 evaluating electroencephalographic (EEG)-assessed sleep in association with suicide risk, only one included depression as a covariate.17 Nonetheless, this study reported significant relationships between EEG parameters and past suicide ideation and attempts, covarying depression severity.18

To address these gaps in the literature, we sought to: (Aim 1) confirm that disturbed sleep confers independent risk for suicidal ideation symptoms (i.e., beyond known covariates, depression6,9 and alcohol use19,20) using a longitudinal design, validated symptom measures, and an acute time frame, and (Aim 2) evaluate whether this relationship emerges using objective and subjective sleep measures. Due to the invasiveness of EEG and its time-limited nature in the context of suicidal symptom change (i.e., single-night versus ongoing assessments), actigraphy was selected as our primary sleep measure. Last, based on research suggesting that emotion regulation deficits are associated with sleep disruption21 and suicidal behaviors,22–24 we explored whether intra-individual variation in mood was related to SI and sleep parameters (Aim 3).

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

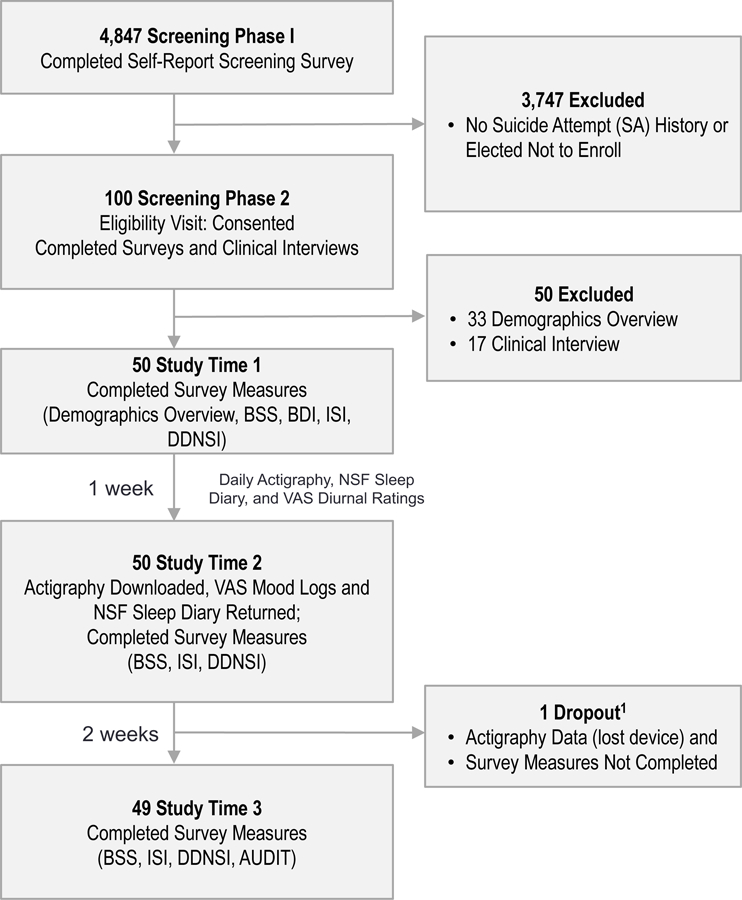

Participants were recruited for high suicide risk through a multi-phase screening process (February 2007-June 2008) described in a previous report.25 Participants were undergraduates (N=4,487) screened for high suicide risk for inclusion in the present study (See Figure 1 and Supplementary Material for recruitment/enrollment procedures). Inclusion criteria for the current study were: (1) age≥18, and (2) endorsed either: (a) ≥1 past SA, verified by clinical interview,26 and recent (≤6 mos) suicidal ideation; or (b) no SA history, but current (≤1 mos) and recent (≤6 mos) suicidal ideation. SA history was used as a proxy for current risk based on past research,27,28 and study criteria and recruitment procedures were modeled after large-scale suicide prevention trials.29 The NIH Human Subjects and Florida State University Institutional Review Boards approved al study procedures.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of Recruitment, Enrollment, and Study Timeline.

CONSORT diagram of recruitment, enrollment, and study timeframe according to screening and study methods. 1This participant completed T2, but not T3

Abbreviations: AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BSS, Beck Suicide Scale; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; DDNSI; Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Index; Pierce SIS, Pierce Suicide Intent Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale

Materials

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic Overview.

This survey assessed baseline demographic information, personal and family SA history, medication use, medical history, diagnostic characteristics, shiftwork status, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI).

Suicide Risk Measures

Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS).

This 21-item self-report instrument assesses suicidal symptom severity.30 Higher total scores (0–38) indicate greater levels of SI. This scale shows strong reliability and validity and has been normed among inpatient and outpatient samples.30

Pierce Suicidal Intent Scale (Pierce SIS).

This 12-item, clinician-administered interview documents the severity and intent of past suicide attempts.26 Total Scores (0–25) reflect summed subscales (Circumstances, Self-Report, Medical Risk). Research demonstrates good psychometric properties for this measure,26 used to verify inclusion criteria.

Objective Sleep Measures

Actigraphy.

Actigraphy (Actiwatch®; Respironics) provided an objective measurement of sleep. Actigraphs are small, watch-like devices (37×29×9mm;17g) worn on the non-dominant wrist. An electronic accelerometer records movement over preprogrammed (30s) intervals. The actigraph wearer inserts event markers by pressing a button on the actigraph to demarcate, in real-time, their attempted sleep onsets and offsets, which define a given sleep interval. Data were verified for adherence and correspondence with sleep diaries and analyzed by the first author, using commercially-available software algorithms (Actiware®), which automatically generate sleep/wake statistics. Actigraphy data reliably discriminate sleep/wake patterns,31 which show good correspondence with EEG.32 For each sleep interval, derived variables included: sleep onset latency (SoL; minutes elapsed between attempting and achieving sleep onset), total sleep time (TST; sleep duration, minus awakenings), wake after sleep onset (WASO; minutes awake following sleep onset), sleep efficiency (SE; [%] of time asleep: time in bed), and sleep variability (SV; standard deviations of daily sleep onsets [i.e., time when sleep was initiated] and sleep offsets [i.e., time of final wakening]; these indices were summed to provide an overall index of SV, consistent with past reports33), identified using Actiware® algorithms. Additional variables included average bedtime (BT)/wake time (WT), time in bed (TIB; hours in bed, regardless of time asleep), and nap and sleep interval frequency. For post-hoc analyses, standard deviations of SoL, TST, WASO, and SE were also calculated. Actigraphy sleep data were computed based on a 7-day period for each participant.

Daily Sleep Diary.

Actigraphy data were verified using the National Sleep Foundation diary, adapted for study use. Diaries provide reliable comparison with actigraphy32 and were inspected for missing event markers, consistent with past studies.31,34,35

Subjective Sleep Measures

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

This 7-item self-report measure assesses the frequency and severity of insomnia symptoms.36 Higher total scores indicate greater insomnia severity. This measure is a gold standard insomnia instrument,37 widely used in clinical trials. Scores ≥10 appear to provide optimal sensitivity and specificity.37

Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Severity Index (DDNSI).

This 5-item self-report scale assesses the intensity, frequency, and severity of disturbing dreams and nightmares. This is a revised version of the Nightmare Frequency Questionnaire38 and is used commonly in nightmare assessment. Scores >10 suggest clinically-significant nightmares.

Covariate Measures

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II).

This 21-item self-report inventory assesses depressive symptomatology, with higher scores reflecting greater symptom severity.39 It yields adequate reliability estimates and psychometrics.39 To prevent collinearity, overlapping items (9, 16, 20) were removed, consistent with previous reports.15,16

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).

This 10-item self-report questionnaire screens for hazardous alcohol use.40 Items address consumption, alcohol-related problems, and dependence symptoms. Total scores ≥8 generally signal harmful drinking.40

Exploratory Measures

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Mood Ratings.

Self-ratings of depressed mood were administered alongside daily sleep diaries, diurnally (i.e., once in the morning, once at night). Participants used a vertical line to indicate ratings (anchors: “not at all depressed” to “very depressed.” To index intra-individual mood variation, the standard deviation of VAS (VAS-MV) was calculated as a proxy for mood lability.

Sequence of Investigation

Those invited from Screening Phase 1 scheduled in-person eligibility visits for Screening Phase 2 using a secure, fully-encrypted online network. Participants provided written informed consent after thorough explanation of study procedures. Visits occurred at three study time points: T1 (baseline), T2 (7-day follow-up), and T3 (21-day follow-up).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were planned for all key variables, including inter-correlations between measures. Factors significantly associated with baseline BSS were planned for inclusion as covariates.

Linear hierarchical multiple regression analyses were employed to test hypotheses. To assess causal risk and temporal ordering, symptom relationships were assessed longitudinally, adjusting for baseline symptoms in each model. BSS residual change scores were created to evaluate actigraphic and subjective sleep parameters in association with suicidal symptom increases at 7- and 21-days follow-up (T2, T3). To create residual change scores, T1 BSS total scores were entered into Block 1 of each regression; planned covariates were entered into Block 2. For Actigraphy Analyses, lower SE and higher TST, SoL, WASO, and SV were hypothesized to predict T2 and T3 BSS increases. This approach was repeated for Subjective Sleep Analyses, wherein higher ISI/DDNSI scores were hypothesized to predict T2 and T3 BSS increases. For Exploratory Analyses, higher VAS-MV was expected to predict BSS change and actigraphic and subjective sleep parameters.

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Software—Version 23.00 (IBM).

Power

Based on similarly-designed studies,16,41 proposed analyses had adequate power (1-β>.85; α<.05) to detect a medium effect size (d~.5) or higher.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics are presented in Tables 1–2.

Table 1a.

Baseline Sample and Clinical Severity Characteristics

| No. (%) or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 19.2 (1.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male, No. (%) | 14 (29) |

| Female, No. (%) | 35 (71) |

| Race/Ethnicity1 | |

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 37 (74) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 6 (12) |

| African American, No. (%) | 3 (6) |

| Asian, No. (%) | 1 (2) |

| Mixed Race, No. (%) | 2 (4) |

| Other, No. (%) | 1 (2) |

| Suicidal Behavior History | |

| Past Suicide Attempts | |

| No Attempts, No. (%) | 2 (4) |

| Single Attempters, No. (%) | 33 (66) |

| Multiple Attempters, No. (%) | 15 (30) |

| Years Since Last Suicide Attempt, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.4) |

| Age at Worst-Point Suicide Attempt, mean (SD) | 15.0 (2.3) |

| Suicide Attempt Method | |

| Overdose/Poisoning, No. (%) | 29 (60) |

| Cutting, No. (%) | 13 (27) |

| Asphyxiation, No. (%) | 2 (4) |

| Firearm, No. (%) | 1 (2) |

| Other, No. (%) | 3 (6) |

| Pierce SIS Intent Score, mean (SD) | 8.2 (4.4) |

| Family History of Suicide, No. (%) | 6 (12) |

| Non-Suicidal Self-Injury History, No. (%) | |

| No Prior History, No. (%) | 16 (32) |

| Prior History, No. (%) | 25 (50) |

| Current NSSI, No (%) | 5 (10) |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses, No. (%) | 21 (42) |

| Mood Disorders, No. (%) | 16 (76) |

| Anxiety Disorder, No. (%) | 7 (33) |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, No. (%) | 7 (33) |

| Eating Disorder, No. %) | 1 (5) |

| Sleep Disorder | 2 (10) |

| Comorbid Disorders, No. (%) | 9 (43) |

| Psychiatric Medication Use | 9(16) |

| Antidepressants, No. (%) | 5 (56) |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), No. (%) | 5 (56) |

| Other Antidepressants, No. (%) | 2 (22) |

| Stimulant/Non-Stimulant SSRI (SNRI). No. (%) | 2 (22) |

| Anxiolytics, No. (%) | 1(11) |

| Antipsychotic, No. (%) | 1(11) |

| Mood Stabilizer. No. (%) | 1(11) |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | |

| BSS. mean (SD) | 6.7 (6.2) |

| Mild Symptoms (0–4), No. (%) | 29 (58) |

| Moderate Symptoms (5–15), No. (%) | 17(34) |

| Moderate-Severe Symptoms (16–23), No. (%) | 3(6) |

| Severe (24–36), No. (%) | 1(2) |

| BDI-II. mean (SD) | 19.7(10.4) |

| Minimal Symptoms (0–13), No (%) | 16(32) |

| Mild Symptoms (14–19), No (%) | 9(18) |

| Moderate Symptoms (20–28), No (%) | 17(34) |

| Severe Symptoms (29–63), No (%) | 8(16) |

| AUDIT, mean (SD) | 9.5 (6.9) |

| Non-Clinical Symptoms (0–7), No (%) | 18 (36) |

| Clinically Significant Symptoms (8–29), No (%>) | 28 (56) |

| Subjective Sleep Disturbances | |

| 1ST mean (SD) | 13.5 (5.6) |

| Non-Clinical Symptom Range (0–9), No. (%) | 11 (22) |

| Clinical Symptom Range (10–28), No. (%) | 39 (78) |

| DDNSI. mean (SD) | 7.1 (7.0) |

| Non-Clinical Symptom Range (0–9), No. (%) | 32 (64) |

| Clinical Symptom Range (10–37), No. (%) | 18 (36) |

Abbreviations: AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BSS, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; DDNSI; Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Index; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; Pierce SIS, Pierce Suicide Intent Scale

Ethnicity and racial categorization options were created by the investigators, and identification to a given category was based on participant response

Table 2.

Baseline Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges, and Intercorrelations Between Measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BSS | 1 | .487a | .026 | .254 | .343a | .385b |

| 2. BDI-II | 1 | .303a | .552b | .503b | −.087 | |

| 3. AUDIT | 1 | .224 | .104 | −.149 | ||

| 4. ISI | 1 | .344a | −.062 | |||

| 5. DDNSI | 1 | −.062 | ||||

| 6. Pierce SIS | 1 | |||||

| Mean | 6.7 | 19.7 | 9.5 | 13.5 | 7.1 | 8.2 |

| SD | 6.2 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 4.4 |

| Range | 1−27 | 1−41 | 0−29 | 0−24 | 0−21 | 1−12 |

| α | .83 | .90 | .86 | .84 | .74 | .76 |

Abbreviations. AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BSS, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; DDNSI, Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Severity Index; Pierce SIS, Pierce Suicide Intent Scale

Note.

= P < .05

= P < .01

Covariates.

AUDIT alcohol-related problems were common, and participants reported moderate to severe BDI-II-assessed depressive symptoms.

Suicidal Symptoms.

Moderate mean BSS symptoms were observed, with maximum scores in the severe range for SI.

Actigraphic Sleep Parameters.

Sleep diaries were complete in 100% of cases, which paralleled actigraphy use compliance (>98%). Event marker adherence was also high (2.67 missing of 14.77 mean total). Independent of shiftwork status (n=3 recorded shiftwork schedules 1–3 days; i.e., schedules overlapping with midnight), several other participants (n=3) demonstrated extended wakefulness (i.e., 24-hour periods without initiating sleep). Both appeared associated with greater SV, according to mean actigraphy metrics and their inter-correlations. For example, SV correlated with delayed BT (r=.46, p=.001), WT (r=.45, p=.001), nap frequency (r=.42, p=.003), and sleep interval number (r=.27, p=.052).

Subjective Sleep Parameters.

Mean ISI scores were consistent with an insomnia diagnosis;37 one-third of participants reported clinically-significant nightmares.

Covariate Analyses

Demographic variables were not significantly correlated with BSS (age: r=−.08, p=.57; sex: r=−.05, p=.74). BDI-II totals correlated with BSS across time points (r=.40-.50, p<.01), whereas AUDIT scores did not (r=.−05-.10, p>.05). BDI-II was thus retained as a covariate.

Regression Analyses

See Table 3 for model statistics.

Table 3.

Model Statistics for Hierarchical Linear Regression Analyses

| t | β (95% CI) | P Value | Model Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actigraphy Sleep Measures | ||||

| Regression 1: T2 BSS |

R2=0.69 F(7,49)=13.36 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 7.43 | 0.78 (0.47 to 0.83) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | −0.41 | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.09) | 0.67 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SE | −0.18 | −0.03 (−0.38 to 0.31) | 0.85 | |

| WASO | −0.56 | −0.09 (−0.15 to 0.08) | 0.57 | |

| SoL | 0.85 | 0.08 (−0.07 to 0.19) | 0.39 | |

| TST | 0.84 | 0.12 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.40 | |

| SV | 3.18 | 0.28 (0.13 to 0.58) | <0.01b | |

| Regression 2: T3 BSS |

R2=0.55 F(7,48)=16.36 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 5.28 | 0.67 (0.37 to 0.84) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | 0.44 | 0.05 (−0.12 to 0.18) | 0.66 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SE | 1.27 | 0.32 (−0.17 to 0.75) | 0.21 | |

| WASO | 0.68 | 0.13 (−0.10 to 0.21) | 0.49 | |

| SoL | 0.67 | 0.08 (−0.11 to 0.23) | 0.50 | |

| TST | −0.58 | −0.10 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.56 | |

| SV | 2.46 | 0.27 (0.06 to 0.66) | 0.01a | |

| Subjective Sleep Measures | ||||

| Regression 1: T2 BSS |

R2=0.69 F(4,49)=25.22 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 8.41 | 0.81 (0.51 to 0.83) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | −1.46 | −0.16 (−0.20 to 0.03) | 0.15 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| T2 ISI | 2.04 | 0.18 (0.00 to 0.40) | 0.04a | |

| T2 DDNSI | 2.49 | 0.22 (0.03 to 0.33) | 0.01a | |

| Regression 2: T3 BSS | R2=0.59 F(4,48)=16.36 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 4.62 | 0.52 (0.26 to 0.67) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | −0.38 | −0.04 (−0.16 to 0.11) | 0.70 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| T3 ISI | 3.10 | 0.32 (0.11 to 0.52) | <0.01b | |

| T3 DDNSI | 2.19 | 0.22 (0.01 to 0.37) | 0.03a | |

| Exploratory Mood Measures | ||||

| Regression 1: T2 BSS |

R2=0.66 F(3,49)=30.91 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 7.48 | 0.73 (0.44 to 0.77) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | −0.73 | −0.07 (−0.15 to 0.07) | 0.46 | |

| Block 2: VAS-MV | 2.80 | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.76) | <0.01b | |

| Regression 2: T3 BSS |

R2=0.49 F(3,48)=14.48 P≤0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 4.90 | 0.60 (0.31 to 0.76) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | 0.26 | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.17) | 0.79 | |

| Block 2: VAS-MV | 1.59 | 0.18 (−0.09 to 0.78) | 0.11 | |

| Regression 3: VAS-MV |

R2=0.38 F(6,48)=4.37 P=0.002 |

|||

| Block 1: BDI-II | 2.48 | 0.32 (0.01 to 0.18) | 0.01a | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SE | 0.46 | 0.13 (−0.22 to 0.35) | 0.64 | |

| WASO | −0.04 | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.09) | 0.96 | |

| SoL | 2.35 | 0.33 (0.01 to 0.24) | 0.02a | |

| TST | −0.19 | −0.03 (−0.02 to 0.01) | 0.84 | |

| SV | 2.79 | 0.35 (0.07 to 0.44) | <0.01b | |

| Regression 4: VAS-MV |

R2=0.21 F(3,49)=4.24 P=.010 |

|||

| Block 1: BDI-II | 2.20 | 0.32 (0.00 to 0.20) | 0.03a | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| T2 ISI | 1.29 | 0.18 (−0.06 to 0.30) | 0.20 | |

| T2 DDNSI | 0.46 | 0.06 (−0.10 to 0.17) | 0.64 | |

| Post-Hoc Analyses | ||||

| Regression 1: T2 BSS |

R2=0.70 F(4,48)=25.86 P<0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 8.51 | 0.81 (0.51 to 0.83) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | −0.28 | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.09) | 0.77 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SV Onset | 2.79 | 0.41 (0.26 to 1.61) | <0.01b | |

| SV Offset | −0.91 | −0.13 (−1.07 to 0.40) | 0.36 | |

| Regression 2: T3 BSS |

R2=0.53 F(4,48)=12.73 P<0.001 |

|||

| Block 1: | ||||

| T1 BSS | 5.52 | 0.66 (0.37 to 0.80) | <0.01b | |

| BDI-II | 0.45 | 0.05 (−0.11 to 0.17) | 0.65 | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SV Onset | 1.74 | 0.32 (−0.12 to 1.70) | 0.08 | |

| SV Offset | −0.30 | −0.05 (−1.15 to 0.85) | 0.76 | |

| Comparison of Predictors: T2 BSS |

R2=0.69 F(4,48)=25.41 P<.001 |

|||

| Block 1: BDI-II | 7.91 | 0.76 (0.47 to 0.79) | <0.01b | |

| Block 2: | ||||

| SV | 2.22 | 0.20 (0.02 to 0.48) | 0.03a | |

| VAS-MV | 1.73 | 0.17 (−0.04 to 0.63) | 0.09 | |

| BDI-II | −0 88 | −0.08 (−0.15 to 0.06) | 0.38 |

Abbreviations: SE, Sleep Efficiency; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset; SoL, Sleep Onset Latency; TST, Total Sleep Time; SV, Sleep Variability; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; BSS, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; DDNSI, Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Severity Index; VAS-MV, Visual Analog Scale-Mood Variability

Note.

= P < .05

= P < .01

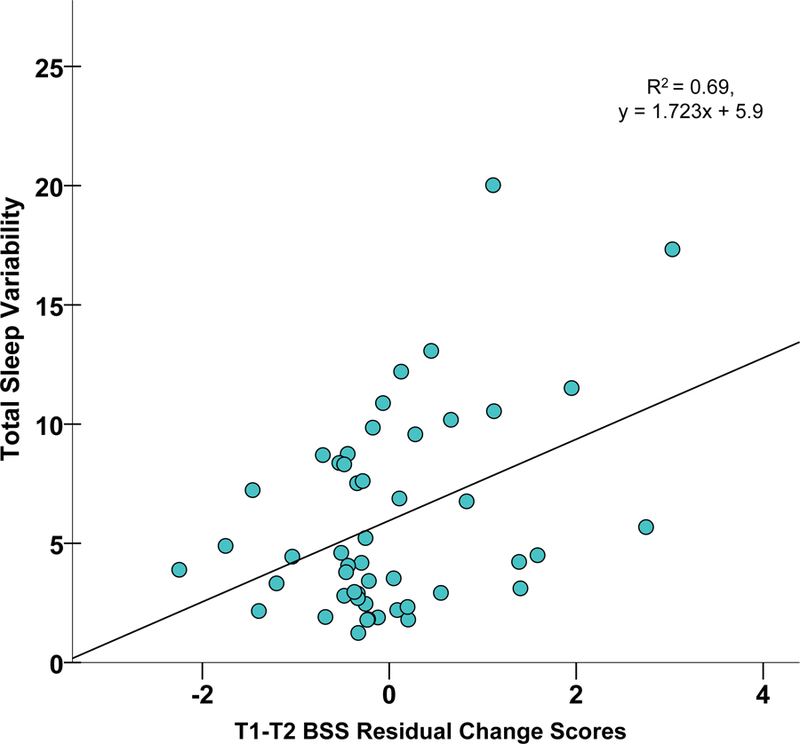

Actigraphic Sleep Parameters

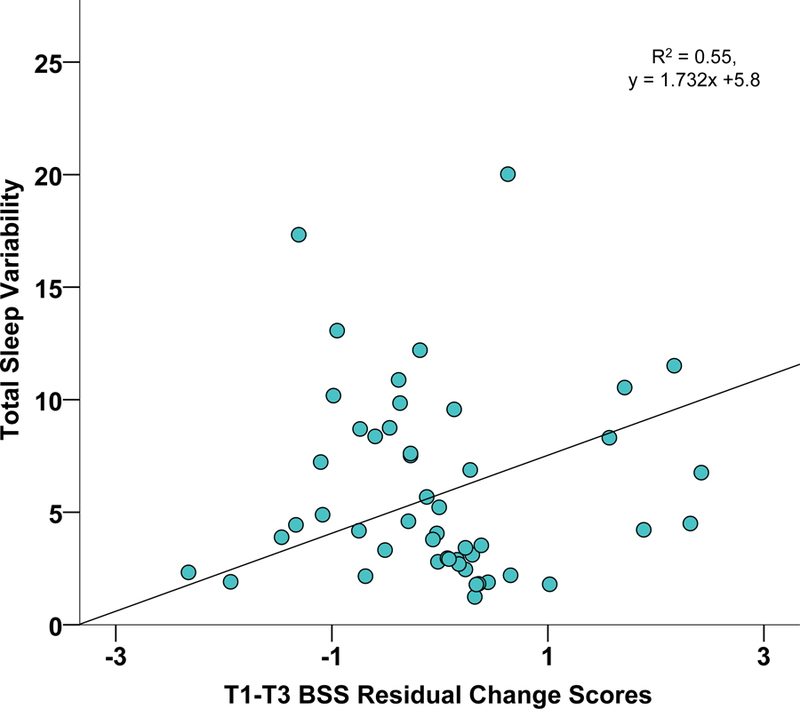

For Regressions 1–2, actigraphy variables, as a set, significantly predicted T2 and T3 BSS residual change scores, controlling for BDI-II. However, only SV predicted such change relative to other actigraphy parameters (Figure 2).

Figure 2a. Scatterplot of Sleep Variability and T2 BSS Residual Change Scores.

Scatterplot of actigraphically-assessed total sleep variability by BSS suicidal ideation residual change scores (T1-T2), adjusting for baseline BDI-II

Abbreviations: BSS, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2

Note: Sleep variability represents the standard deviation of actigraphically-assessed sleep offsets and sleep onsets, summed, as an overall index of sleep timing and irregularity

Subjective Sleep Parameters

For Regressions 1–2, higher ISI and DDNSI were significantly associated with T2 and T3 BSS residual change scores, adjusting for BDI-II. Each emerged as individual predictors of symptom increases.

Exploratory Mood Analyses

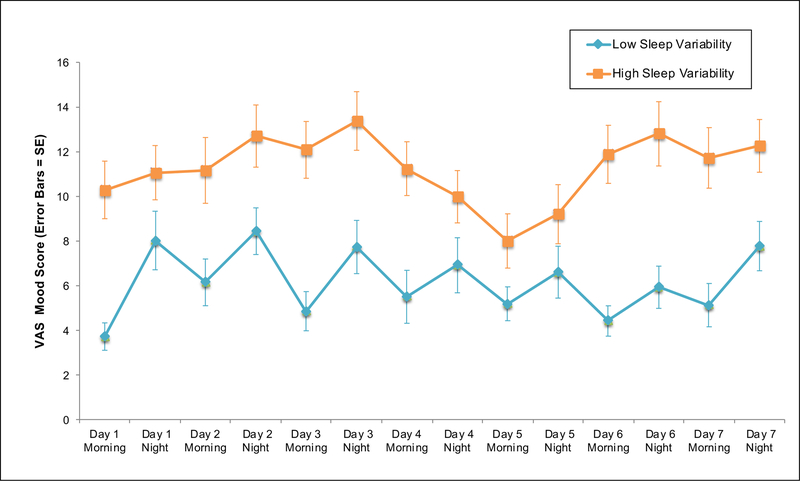

For Regressions 1–2, main effects were significant for model statistics. However, this was a non-significant trend for T3 BSS. For Regression 3, whereas actigraphy variables jointly predicted VAS-MV, controlling for BDI-II; only SoL and SV individually contributed to the model variance. For Regression 4, neither ISI nor DDNSI individually predicted VAS-MV.

Post-Hoc Analyses

Based on observed findings for SV as a significant predictor of risk, post-hoc analyses were conducted to evaluate whether a specific component of the sleep-wake cycle (i.e., sleep onsets versus offsets) differentially contributed to risk and—by extension—might serve as a treatment target. Specifically, sleep/wake timing variability (i.e., SV onset versus SV offset) was simultaneously compared in the model. Including BDI-II and baseline BSS as covariates, SV Onset accounted for a significant portion of the variance in T2 and T3 BSS change scores relative to SV Offset. Variability of other sleep parameters (i.e., variations in SE, WASO, SoL, and TST) were also examined as predictors of risk within a single model with SV, including BDI-II and baseline BSS as covariates. Only greater SV and less variability in TST were significant predictors of T2 BSS change scores (Supplementary Material).

Correlations were employed to elucidate SV in relationship to other sleep parameters. Beyond delayed BT/WT and nap frequency, SV was not significantly correlated with other actigraphy variables (TST, SoL, WASO, SE; p>.05); though a non-significant trend emerged for TST (r=−.26, p=.07). Significant intercorrelations were, however, observed for SV and both T2 ISI (r=.35, p=.02) and DDNSI (r=.02, p=.04).

Finally, given that SV and VAS-MV significantly predicted T2 BSS symptom change, controlling for BDI-II, a follow-up test was conducted to identify the most robust predictor of risk. All three variables were included in a competing model for simultaneous comparison as predictors (Regression 3) and to replicate past findings,16,42 using an objective sleep index. Surprisingly, SV and VAS-MV accounted for more unique variance in prediction of BSS symptom change compared to BDI-II (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Findings revealed that actigraphic and self-reported sleep disturbances (i.e., sleep variability, insomnia, and nightmares) predicted acute suicidal ideation symptom changes, an effect that occurred independent of depressive symptoms at 7- and 21-days follow-up. This converges with past reports demonstrating associations between subjective sleep problems and suicidal behaviors—controlling for depression severity and affective disorder7,13,16—and studies identifying nocturnal wakefulness as a predictor of suicide ideation and deaths.43,44 Such effects were observed despite clinical levels of covariates and sleep problems, commensurate with a diagnosis. Likewise, mean actigraphy indices exceeded cut-points distinguishing those with insomnia from controls,34,35 which revealed significant variability in the timing of sleep onsets and offsets (≥2.9 h). Such patterns strongly conflict with an increased developmental need for sleep among this age group.10,45

Although actigraphic parameters together predicted suicidal ideation increases, only sleep variability—in particular, sleep onset variability—individually predicted such symptom change. Greater variability of other objective sleep parameters (i.e., SE, WASO, SoL) did not predict SI changes, whereas less variability in total sleep time (i.e., consistent lack of sleep) significantly predicted risk, alongside irregularity in the overall timing of sleep. This builds upon an emerging literature tying intra-individual variability in sleep timing to an array of adverse outcomes, including stressful life events, negative affect, insomnia, and depression.33,46 Similar to studies among youth,47 we observed significant correlations between sleep variability and subjective sleep complaints, delayed bedtimes, and nap frequency. This aligns with conceptual models of insomnia development, underscoring the unpredictability of sleep as a cause and a consequence of insomnia and its maintenance.48,49 Such findings suggest that sleep variability may be an important feature—alongside insomnia, nightmares, and nocturnal wakefulness43,44—to assess in the presence of other well-established suicide risk factors. These findings may also guide application to risk assessment, given findings that combination of actigraphy and self-reported sleep may significantly aid prediction of risk and specific mood states.50,51

Our sample reflected a group at heightened risk based on history of suicidal behaviors28 and NSSI.52,53 The majority of participants endorsed a past suicide attempt, and one-third reported multiple attempts. In most cases, these occurred by age 15. This corresponds with a recent epidemiological study among adolescents (n=12,395), in which a newly-identified “invisible” risk group (i.e., with reduced sleep, high media use and sedentary behaviors) showed prevalence of suicidal ideation comparable to those classified by more traditional risk factors.54 Given escalation of risk from adolescence to adulthood among those with past attempts,55,56 sleep may warrant investigation as a risk factor and intervention target for repeat suicidal behaviors.

Regarding clinical rationale, sleep disturbances are arguably less stigmatized compared to other risk factors, yet modifiable and highly treatable. Gold standard insomnia interventions indicate preliminary efficacy in as few as 1–4 treatment sessions.57 Such treatments reduce sleep variability—which otherwise predicts treatment resistance.46,58 Insomnia and nightmare treatment furthermore demonstrates improvements in non-sleep outcomes, including depression and suicidal ideation.38,59 Additionally, the brevity of this approach appears well-matched to the acute nature of a suicidal crisis and treatment engagement difficulties following a suicide attempt (i.e., where up to half will refuse treatment,60 and 75% may drop out ≤1 year61). Taken together, sleep treatment may represent a low-risk intervention strategy for suicidal behaviors.

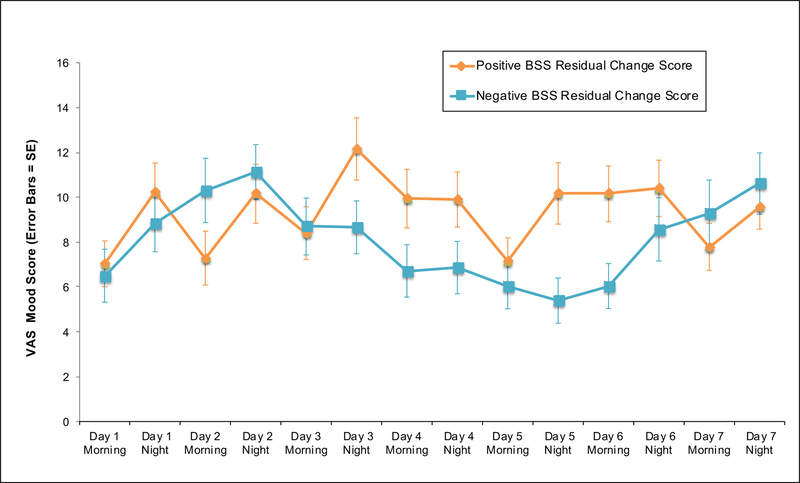

As a proposed exploratory factor, intra-individual mood variation predicted suicidal symptom increases, independent of depressive symptoms. Although main effects were observed for objective and subjective sleep parameters, only sleep variability and sleep onset latency were individually related to mood fluctuations, which may be unsurprising given the degree of symptom overlap. Finally, in a competing risk model, we compared sleep variability, depressive symptoms, and mood variability as predictors of suicidal ideation. Remarkably, sleep variability—and to a lesser extent, mood variability—outperformed depression severity in the prediction of acute suicidal symptom change. While unexpected, this converges with at least two reports, including a study among military personnel referred for imminent suicide risk42 and a population-based investigation of late-life suicide.16 In both cases, poor subjective sleep quality outperformed depressive symptoms and hopelessness in the prediction of incident risk for suicide attempts (i.e., ≤1 month) and fatalities (i.e., ≤10 years). To our knowledge, this is the first study yielding similar results utilizing an actigraphic sleep measure and acute time frame.

Sleep disturbances and suicidal behaviors cut across psychiatric and medical illness,62,63 suggesting a shared underlying neurobiology. Based on the role of sleep in emotion,21 and its association to suicide risk,24 we evaluated mood variability as an exploratory risk factor. Our findings broadly converge with experimental and non-experimental studies of sleep deprivation, which show effects on emotional reactivity,64 amygdala activation,65 a blunting of positive affect,64 and depression-like changes in serotonergic function.63 Interestingly, a number of biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory cytokines, BDNF, 5HTT expression, etc.) exist at the intersection of sleep and suicidal behaviors,47,66,67 suggesting that sleep loss may induce vulnerability at the molecular level. Given the neurocognitive deficits observed in suicidal behaviors,68 and the degree to which poor sleep and suicide cut across psychiatric illness,8 we recommend further study of sleep using a systems neuroscience approach. This is commensurate with initiatives emphasizing the importance of transdiagnostic risk factors69 and development of a biosignature for suicide.66,67

Several limitations should be noted. First, actigraphy served as our objective measure of sleep versus polysomnography. Future studies, evaluating correspondence to sleep architecture, are needed. Next, although research identifies poor sleep as a risk factor across diagnostically diverse samples, our study was limited to self-reported diagnostic histories. Replication is thus warranted using clinician-administered diagnostic interviews and to evaluate generalizability among those without a suicide attempt history. Finally, suicidal behaviors range in severity from suicide ideation to attempts to fatalities. While suicidal thoughts are well-established as a suicide risk factor,70 especially in the presence of past attempts,28,71 investigation of actigraphically-assessed sleep and for suicide attempt risk is strongly recommended.

Conclusions

Research suggests that less than 1% of studies examining suicide risk reflect the weeks prior to suicidal behaviors,6 elevating the need for methodologically-rigorous screening and evaluation of warning signs. Study strengths include its highly selective sample, longitudinal design, and acute time frame. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal report indicating that objective and subjective sleep disturbance confer risk for suicidal ideation, independent of depression severity. Given the ease of sleep disturbance assessment and treatment, and its unique visibility as a warning sign, we propose poor sleep as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for suicide prevention.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2b. Scatterplot of Sleep Variability and T3 BSS Residual Change Scores.

Scatterplot of actigraphically-assessed total sleep variability by BSS suicidal ideation residual change scores (T1-T3), adjusting for baseline BDI-II

Abbreviations: BSS, Beck Suicide Scale; T1, Time 1; T3, Time 3

Note: Sleep variability represents the standard deviation of actigraphically-assessed sleep offsets and sleep onsets, summed, as an overall index of sleep timing and irregularity

Figure 2c. Mean VAS Mood Ratings for Individuals with Positive and Negative BSS Residual Change Scores.

Abbreviations: BSS, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; SE, Standard Error

Note: BSS residual change scores represent suicidal ideation symptom increases from T1-T2, controlling baseline BSS and BDI-II

Figure 2d. Mean VAS Mood Ratings for Individuals with Low and High Sleep Variability.

Abbreviations: VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; SE, Standard Error

Note: Sleep variability represents an overall index of sleep timing and sleep irregularity (i.e., the summed standard deviation of sleep offsets and sleep onsets)

Table 1b.

Sample Subjective and Objective Sleep Parameter Descriptives Assessed at Time 2

| No. (%) or Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Sleep Parameters | |||

| ISI, mean (SD) | 11.8 (4.8) | 1 | 23 |

| Nov-Clinical Symptom Range (0–9), No. (%) | 14 (28) | -- | -- |

| Clinical Symptom Range (10–28), No. (%) | 36(72) | -- | -- |

| DDNSI, mean (SD) | 5–5 (6.3) | 0 | 24 |

| Non-Clinical Symptom Range (0–9), No. (%) | 39 (78) | -- | -- |

| Clinical Symptom Range (10–37), No. (%) | 11 (22) | -- | -- |

| Objective Sleep Parameters, mean (SD)1 | |||

| Bedtime (BT). hli:nun | 02:08 (1:34) | 22:06 | 05:54 |

| Wake Time (WT). hlimnn | 09:21 (1:37) | 04:06 | 12:12 |

| Total Time m Bed (TIB), h | 7.7 (1.1) | 5.0 | 11.0 |

| Naps, No. | 1.35 (1.78) | 0 | 7 |

| Sleep Intervals, No. | 8.37 (2.02) | 6 | 15 |

| Sleep Onset Latency (SoL). m | 11.6(7.8) | 1.2 | 44.9 |

| Total Sleep Time (TST), h | 5.9 (1.1) | 3.2 | 7.6 |

| Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO). m | 31.2 (14.1) | 10.3 | 73.9 |

| Sleep Efficiency (SE), % | 84.4 (6.2) | 64.4 | 93.6 |

| Sleep Variability (SV), h | 6.0 (4.2) | 1.24 | 20.0 |

| SV Onset, h | 3.1 (2.3) | 0.4 | 9.6 |

| SV Offset h | 2.9 (2.1) | 0.3 | 10.4 |

Abbreviations: ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; DDNSI, Disturbing Dreams and Nightmare Severity Index; BT, Bedtime; WT, Wake Time; TIB, Total Time in Bed; SoL, Sleep Onset Latency; TST, Total Sleep Time; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset; SE, Sleep Efficiency; SV, Sleep Variability; h = hours; m = minutes; hh:mm = clock time

One participant lost the Actiwatch device and completed T2, but not T3

CLINICAL POINTS.

Self-reported sleep disturbances confer risk for suicide; however, little is known about objective sleep parameters as a warning sign for suicidal behaviors.

Assessment and management of suicide risk are indicated among patients with disturbed sleep, particularly variability in sleep timing, insomnia, and nightmares.

Poor sleep is proposed as a biomarker of risk and a potential therapeutic target for suicide prevention.

Acknowledgment:

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation (Joiner) and National Institutes of Health support: F31MH080470-01 (Bernert), NIH K23MH093490 (Bernert). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: N/A

Disclaimers: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative Geneva: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Reducing suicide: A national imperative 2002.

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention 2012: Goals and Objectives for Action Washington, DC; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Mental Health Information Center. Suicide warning signs 2005. http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SVP11-0126/SVP11-0126.pdf.

- 5.Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73(9):e1160–e1167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 2016. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernert RA, Kim JS, Iwata NG, Perlis ML. Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17(3):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown G, Beck A, Steer R, Grisham J. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68(3):371–377. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens J, Adolescent Sleep Working Group, Committee on Adolescence. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: An update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics 2014;134(3):e921–e932. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep 2008;31(4):473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. WISQARS: Cost of Injury Reports https://wisqars.cdc.gov:8443/cost. Published 2015.

- 13.Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76(1):84–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.76.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roane BM, Taylor DJ. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep 2008;31(10):1351–1356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong MM, Brower KJ. The prospective relationship between sleep problems and suicidal behavior in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46(7):953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernert RA, Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Joiner TE. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: A longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(10):1129–1137. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keshavan MS, Reynolds CF, Montrose D, Miewald J, Downs C, Sabo EM. Sleep and suicidality in psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;89(2):122–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabo E, Reynolds CF 3rd, Kupfer DJ, Berman SR. Sleep, depression, and suicide. Psychiatry Res 1991;36(3):265–277. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90025-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004;76 Suppl:S11–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagge CL, Lee HJ, Schumacher JA, Gratz KL, Krull JL, Holloman G. Alcohol as an acute risk factor for recent suicide attempts: A case-crossover analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2013;74(4):552–558. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1156:168–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minkel JD, Banks S, Htaik O, et al. Sleep deprivation and stressors: Evidence for elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived. Emotion 2012;12(5):1015–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0026871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiskal HS, Benazzi F. Psychopathologic correlates of suicidal ideation in major depressive outpatients: Is it all due to unrecognized (bipolar) depressive mixed states? Psychopathology 2005;38(5):273–280. doi: 10.1159/000088445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zlotnick C, Donaldson D, Spirito A, Pearlstein T. Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(6):793–798. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hom MA, Joiner TE, Bernert RA. Limitations of a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history: Implications for standardized suicide risk assessment. Psychol Assess 2015;4(27). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce DW. Suicidal intent in self-injury. Br J Psychiatry 1977;130:377–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT. History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(3):437–443. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: Even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry 2016. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294(5):563–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. J Clin Psychol 1988;44(4):499–505. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadeh A The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: An update. Sleep Med Rev 2011;15(4):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med 2001;2(5):389–396. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bei B, Wiley JF, Trinder J, Manber R. Beyond the mean: A systematic review on the correlates of daily intraindividual variability of sleep/wake patterns. Sleep Med Rev 2015;28:104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natale V, Léger D, Bayon V, et al. The consensus sleep diary: Quantitative criteria for primary insomnia diagnosis. Psychosom Med 2015;77(4):413–418. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natale V, Léger D, Martoni M, Bayon V, Erbacci A. The role of actigraphy in the assessment of primary insomnia: A retrospective study. Sleep Med 2014;15(1):111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011;34(5):601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krakow B, Hollifield M, Johnston L, et al. Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286(5):537–545. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Revised Beck Depression Inventory San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernert RA, Joiner TE Jr., Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep 2005;28(9):1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM, et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord 2012;136(3):743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perlis ML, Grandner MA, Brown GK, et al. Nocturnal wakefulness as a previously unrecognized risk factor for suicide. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77(6):e726–e733. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ballard ED, Vande Voort JL, Bernert RA, et al. Nocturnal wakefulness is associated with next-day suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77(6):825–831. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am 2011;58(3):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suh S, Nowakowski S, Bernert RA, et al. Clinical significance of night-to-night sleep variability in insomnia. Sleep Med 2012;13(5):469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carskadon MA, Sharkey KM, Knopik VS, McGeary JE. Short sleep as an environmental exposure: A preliminary study associating 5-HTTLPR genotype to self-reported sleep duration and depressed mood in first-year university students. Sleep 2012;35(6):791–796. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manber R, Chambers AS. Insomnia and depression: A multifaceted interplay. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2009;11(6):437–442. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998–2004). Sleep 2006;29(11):1398–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geoffroy PA, Boudebesse C, Bellivier F, et al. Sleep in remitted bipolar disorder: A naturalistic case-control study using actigraphy. J Affect Disord 2014;158:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson WK, Gershon A, O’Hara R, Bernert RA, Depp CA. The prediction of study-emergent suicidal ideation in bipolar disorder: A pilot study using ecological momentary assessment data. Bipolar Disord 2014;16(7):669–677. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawton K, Harriss L, Zahl D. Deaths from all causes in a long-term follow-up study of 11,583 deliberate self-harm patients. Psychol Med 2006;36(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: Findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry 2014;13(1):78–86. doi: 10.1002/wps.20088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldston DB, Erkanli A, Daniel SS, Heilbron N, Weller B, Doyle O. Developmental trajectories of suicidal thoughts and behaviors from adolescence through adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;55(5):400–407.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldman-Mellor S, Caspi A, Harrington H, et al. Suicide attempt in young people: A signal for long-term health care and social needs. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(2):119–127. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellis JG, Cushing T, Germain A. Treating acute insomnia: A randomized controlled trial of a “single-shot” of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep 2015;38(6):971–978. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sánchez-Ortuño MM, Edinger JD. Internight sleep variability: Its clinical significance and responsiveness to treatment in primary and comorbid insomnia. J Sleep Res 2012;21(5):527–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manber R, Edinger J, Gress J, San Pedro-Salcedo M, Kuo T, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep 2008;31(4):489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurz A, Moller HJ. Help-seeking behavior and compliance of suicidal patients. Psychiatr Prax 1984;11(1):6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rudd MD, Joiner TE, Rajab MH. Help negation after acute suicidal crisis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63(3):499–503. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V. The neurobiology and genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: A focus on the serotonergic system. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;24(5):467–477. doi: 10.1016/s0893-133x(00)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roman V, Walstra I, Luiten PG, Meerlo P. Too little sleep gradually desensitizes the serotonin 1A receptor system. Sleep 2005;28(12):1505–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Lavie P. The effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: a cognitive-energy model. Sleep 2005;28(1):47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gujar N, Yoo SS, Hu P, Walker MP. Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. J Neurosci 2011;31(12):4466–4474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3220-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oquendo MA. Subtyping suicidal behavior: A strategy for identifying phenotypes that may more tractably yield molecular underpinnings. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77(6):813–814. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16f10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oquendo M, Sullivan G, Sudol K, et al. Toward a biosignature for suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2014. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keilp JG, Sackeim HA, Brodsky BS, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological dysfunction in depressed suicide attempters. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(5):735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE, et al. Warning signs for suicide: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2006;36(3):255–262. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chu C, Klein KM, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Routinized assessment of suicide risk in clinical practice: An empirically informed update. J Clin Psychol 2015. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.