Abstract

Background:

The choice of primary hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in patients ≥80 years of age with a displaced femoral neck fracture has not been adequately studied. As the number of healthy, elderly patients ≥80 years of age is continually increasing, optimizing treatments for improving outcomes and reducing the need for secondary surgery is an important consideration. The aim of the present study was to compare the results of hemiarthroplasty with those of total hip arthroplasty in patients ≥80 years of age.

Methods:

This prospective, randomized, single-blinded trial included 120 patients with a mean age of 86 years (range, 80 to 94 years) who had sustained an acute displaced femoral neck fracture <36 hours previously. The patients were randomized to treatment with hemiarthroplasty (n = 60) or total hip arthroplasty (n = 60). The primary end points were hip function and health-related quality of life at 2 years. Secondary end points included hip-related complications and reoperations, mortality, pain in the involved hip, activities of daily living, surgical time, blood loss, and general complications. The patients were reviewed at 3 months and 1 and 2 years.

Results:

We found no differences between the groups in terms of hip function, health-related quality of life, hip-related complications and reoperations, activities of daily living, or pain in the involved hip. Hip function, activities of daily living, and pain in the involved hip deteriorated in both groups compared with pre-fracture values. The ability to regain previous walking function was similar in both groups.

Conclusions:

We found no difference in outcomes after treatment with either hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in active octogenarians and nonagenarians with a displaced femoral neck fracture up to 2 years after surgery. Hemiarthroplasty is a suitable procedure in the short term for this group of patients.

Level of Evidence:

Therapeutic Level I. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

The choice of surgical procedure for elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures remains controversial1-4. Despite extensive research and the publication of several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty, the question remains regarding whether there is any advantage of replacing a healthy acetabulum with a cup in healthy elderly patients5-11. Several published RCTs have indicated better outcomes after total hip arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty5,7,8,. With few exceptions8,9,11, those studies included a relatively large population of patients <80 years of age. As the number of healthy, elderly patients ≥80 years of age is continually increasing, it is important to study this patient group to assess whether they receive the same benefit as patients <80 years of age.

We hypothesized that total hip arthroplasty would be associated with superior hip function and health-related quality of life, without increasing the rates of complications and reoperations, when compared with hemiarthroplasty for the treatment displaced femoral neck fractures in cognitively intact elderly patients ≥80 years of age.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Location

This single-center, single-blinded, prospective RCT followed the guidelines of good clinical practice and the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement12 and was performed between 2009 and 2018 (inclusion period, September 2009 to April 2016) at the Orthopaedic Department, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karolinska Institute, and all patients gave informed consent to participate in the trial.

Participants

All patients with a displaced femoral neck fracture who were admitted to Danderyd Hospital were screened for participation in the study. The inclusion criteria were an acute displaced femoral neck fracture (Garden 3 or 4) that had occurred <36 hours previously, an age of ≥80 years, the ability to walk independently with or without walking aids, and intact cognitive function with a Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) score of 8 to 10 points13. Patients with a pathological fracture or osteoarthritis, patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the fractured hip, and patients who were non-walkers or who were deemed unsuitable for participation in the study for any reason were excluded14.

Randomization and Blinding

The patients were block-randomized in groups of 10 in a 1:1 ratio to receive either hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty. We used sealed envelopes, and the randomization was stratified for sex to ensure that the sex distribution would be the same in both groups. The participants were blinded to the choice of treatment, but the surgeons and staff were not. They were, however, mindful that patients were blinded and were instructed to not reveal allocation to the patients. The physiotherapy and other care did not differ between the groups. The patients were not allowed to view their radiographs. To verify that blinding was maintained during the study, the patients were asked if they knew their assigned treatment at the 2-year follow-up.

Data Collection and Follow-up

A research nurse interviewed the patients and obtained baseline data for the last week prior to the fracture. The patients were then followed at 3 months and at 1 and 2 years. In the case of withdrawal of consent, the subjects were followed according to the standard procedures of our institution. Functional outcome scores were self-reported by the patients. We used the Swedish unique personal identification number to identify all hip-related complications during the study period. We searched digital medical charts at Danderyd Hospital, the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, and the Swedish Patient Registry. All hip-related complications in the study were managed and registered at our department, and no other reoperations or complications were found to have occurred at other hospitals in Sweden. All study data were collected in a digital case report form using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools provided by Karolinska Institute15.

Surgical Intervention

All operations were performed either by a consultant orthopaedic surgeon or by a registrar with assistance from a consultant with use of a direct lateral approach with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. The modular, collarless, polished, tapered cemented femoral component (CPT; Zimmer) was used until 2014. On the basis of the high incidence of early periprosthetic fractures reported in association with this stem in patients with femoral neck fracture16,17, we changed the implant to an anatomically shaped cemented stem (Lubinus SP2; Waldemar Link) according to a decision made at our institution. A unipolar head replacement was used in the hemiarthroplasty group, and a 32-mm cobalt-chromium head was used in the total hip arthroplasty group. A cemented highly cross-linked polyethylene acetabular component was used in all patients in the total hip arthroplasty group. A vacuum-mixed low-viscosity cement with gentamicin (Palacos with gentamicin; Schering-Plough) was used in all patients. All patients received antibiotic and anticoagulant prophylaxis (3 doses of 2-g cloxacillin and low-molecular-weight heparin for 30 days postoperatively). All patients were allowed to bear weight as tolerated with use of crutches and were mobilized the day after surgery without any restrictions.

Primary End Points

The primary end points were hip function status as assessed with the Harris hip score (HHS) and health-related quality of life as assessed with the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) at 2 years. The HHS has been validated for patients with femoral neck fractures and for self-reporting18,19. Health-related quality of life was assessed before fracture and at the time of follow-up with a generic instrument, the health section of the EQ-5Dindex score20.

Secondary End Points

Secondary end points included hip function status as assessed with the HHS and health-related quality of life as assessed with the EQ-5D at 3 months and 1 year, hip-related complications and reoperations, activities of daily living, pain in the involved hip, mortality, surgical time, intraoperative bleeding, and the ability to regain previous walking function. We recorded adverse events, including cardiovascular events.

Sample Size and Power Analysis

Before the start of the study, sample size calculations were performed on the 2 primary outcome variables (HHS and EQ-5D). Two-sided power analysis was used. On the basis of a previous trial from our research group, we assumed that a mean difference (and standard deviation) of 10 ± 15 points21 in the HHS was the smallest effect that would be clinically relevant. We calculated that a total of 80 patients (40 in each group) would have a power of 80% to yield a significant result. This calculation also allowed an 80% power to prove non-inferiority of EQ-5D with a sample of 40 patients in each group, with the assumption of a mean EQ-5D value (and standard deviation) of 0.73 ± 0.18 and a non-inferiority limit of 0.1. The significance level was set at 2.5% (p < 0.025) to handle multiplicity because we performed 2 sample-size calculations. We planned to include 60 patients in each group (120 patients total) to allow for the loss of patients to follow-up.

Statistical Methods

The analyses of outcomes were based on the intention-to-treat principle, and all patients were analyzed in their randomized group regardless of any other surgical intervention. A per-protocol analysis, including only those patients who received their allocated treatments, was also performed. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used to describe the patient characteristics and outcome variables at the measurement points. The chi-square test was used to test correlations between ordinal data. The Student t test was used to compare the HHS and EQ-5D between the groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of the primary end points was used to reduce variance, with adjustments for exposure variable (hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty) and stratification (male or female). The data are presented with mean differences and odds ratios (ORs), and the uncertainty estimation is presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with use of SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM).

Registration

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02246335) and a detailed study protocol has been published previously14. The complete study period is up to 10 years but with the prespecified primary end points at 2 years.

Both the HHS and EQ-5D were, from the study start, set as primary end points as specified in the study protocol and used in the sample size calculation prior to the start of the study. In the ClinicalTrials.gov registration, only the HHS is listed as the primary endpoint.

Results

Patient Flow and Baseline Data

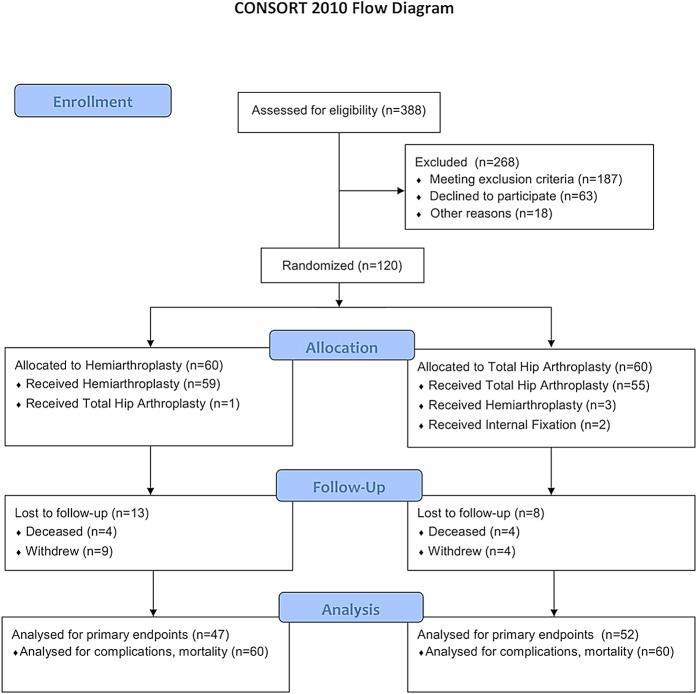

We enrolled 120 patients, 60 in the hemiarthroplasty group and 60 in the total hip arthroplasty group (Fig. 1). The study group included 90 women and 30 men with a mean age of 86 years (range, 80 to 94 years). The baseline characteristics of the groups were similar, but with a slightly higher proportion of patients in the hemiarthroplasty group having an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of 3 or 4. The mean surgical time was 22 minutes shorter in the hemiarthroplasty group. We found no difference between the groups in terms of perioperative bleeding (Table I). Six patients (1 in the hemiarthroplasty group and 5 in the total hip arthroplasty group) did not receive their allocated treatment because of a decline in medical status between randomization and surgical treatment. Two patients were managed with closed reduction and internal fixation with use of cannulated screws (Fig. 1). Eight patients, 4 in each group, died during the study. No deaths occurred during surgery.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flowchart of the patients in the study. One patient in the hemiarthroplasty group was managed with total hip arthroplasty because of the surgeon’s choice during surgery. Two patients in the total hip arthroplasty group were managed with closed reduction and internal fixation because of a suspected urinary tract infection. Another 3 patients in the total hip arthroplasty group were managed with hemiarthroplasty because of the surgeon’s choice during surgery.

TABLE I.

Baseline Data

| Hemiarthroplasty Group (N = 60) | Total Hip Arthroplasty Group (N = 60) | |

| Sex (no. of patients) | ||

| Female | 45 | 45 |

| Male | 15 | 15 |

| Age* (yr) | 86 ± 4 | 85 ± 4 |

| ASA classification (no. of patients) | ||

| 1-2 | 20 | 30 |

| 3-4 | 40 | 30 |

| Body mass index* (kg/m2) | 25 ± 4 | 24 ± 4 |

| Charnley functional classification (no. of patients) | ||

| A | 50 | 46 |

| B | 4 | 9 |

| C | 6 | 5 |

| Mobility: no walking aid or just 1 stick (no. of patients) | 29 (48%) | 30 (50%) |

| Living condition (no. of patients) | ||

| Independent living | 57 | 58 |

| Service buildings/senior housing | 3 | 2 |

| Operative data* | ||

| Surgical time (min) | 77 ± 19 | 99 ± 25 |

| Bleeding (mL) | 324 ± 216 | 355 ± 202 |

| Discharged to geriatric ward (no. of patients) | 52 | 53 |

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

Primary End Points

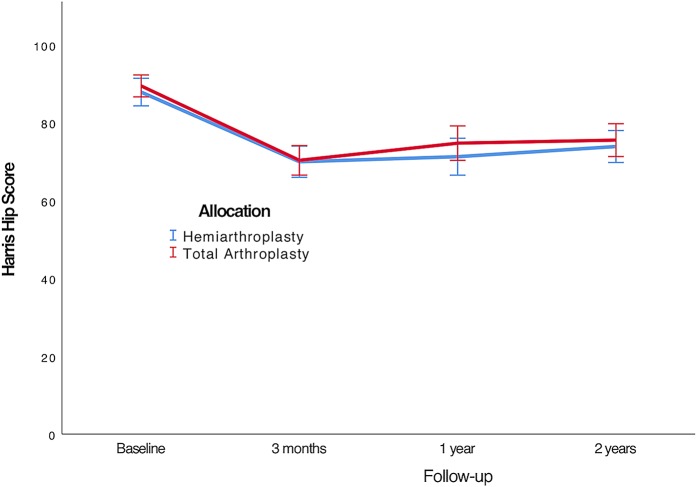

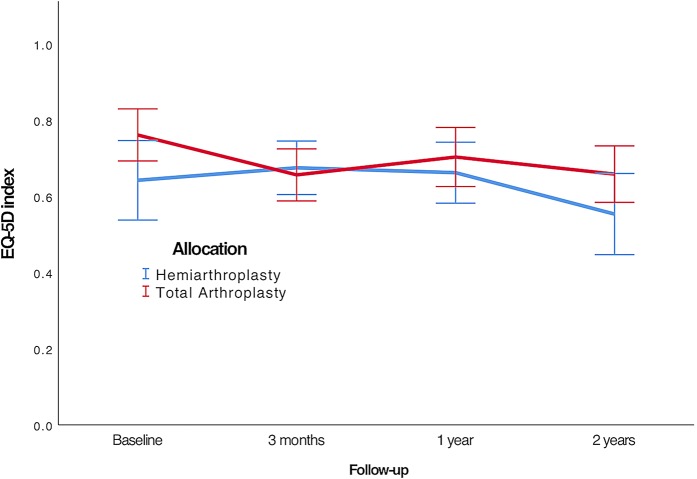

In the intention-to-treat analysis, both the HHS and the EQ-5D score deteriorated from baseline during the study period, but we found no clinically relevant or statistically significant differences in the primary end points between the groups up to 2 years after surgery. These findings remained after both the per-protocol analysis and the ANCOVA analysis of the primary end points (Table II, Figs. 2 and 3). The ASA classification at baseline did not affect the primary end point. Patients with a higher walking ability prior to fracture had a higher HHS at 2 years, but there was no difference in the change of scores between total hip arthroplasty as compared with hemiarthroplasty.

Fig. 2.

Line graph showing the mean HHS (and 95% CIs) for hip function during the study period.

Fig. 3.

Line graph showing the mean EQ-5D index scores (and 95% CIs) for health-related quality of life during the study period.

TABLE II.

Functional Outcomes During the Study Period*

| Intention to Treat | Per Protocol | |||||

| Hemiarthroplasty Group† (N = 60) | Total Hip Arthroplasty Group† (N = 60) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | Hemiarthroplasty Group† (N = 59) | Total Hip Arthroplasty Group† (N = 55) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | |

| Harris hip score (points) | ||||||

| Baseline | 88 ± 12 (n = 59) | 89 ± 10 (n = 60) | −1 (−5 to 3) | 88 ± 12 (n = 59) | 89 ± 10 (n = 55) | −1 (−5 to 3) |

| 3 mo | 69 ± 14 (n = 54) | 70 ± 13 (n = 57) | −1 (−6 to 4) | 69 ± 14 (n = 54) | 70 ± 14 (n = 53) | −1 (−6 to 5) |

| 1 yr | 71 ± 16 (n = 50) | 74 ± 16 (n = 56) | −3 (−9 to 3) | 71 ± 16 (n = 50) | 73 ± 16 (n = 52) | −2 (−9 to 4) |

| 2 yr | 74 ± 14 (n = 47) | 76 ± 15 (n = 56) | −2 (−4 to 2) | 74 ± 14 (n = 47) | 75 ± 15 (n = 49) | −1 (−7 to 5) |

| EQ-5D | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.67 ± 0.34 (n = 59) | 0.75 ± 0.26 (n = 60) | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.02) | 0.67 ± 0.34 (n = 59) | 0.75 ± 0.26 (n = 55) | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.04) |

| 3 mo | 0.67 ± 0.24 (n = 54) | 0.65 ± 0.26 (n = 57) | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.11) | 0.67 ± 0.24 (n = 54) | 0.65 ± 0.25 (n = 53) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.11) |

| 1 yr | 0.66 ± 0.27 (n = 50) | 0.68 ± 0.30 (n = 56) | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.09) | 0.66 ± 0.27 (n = 50) | 0.67 ± 0.31 (n = 52) | −0.01 (−0.12 to 0.10) |

| 2 yr | 0.55 ± 0.36 (n = 47) | 0.66 ± 0.27 (n = 52) | −0.11 (−0.23 to 0.02) | 0.55 ± 0.36 (n = 47) | 0.65 ± 0.27 (n = 49) | −0.11 (−0.23 to 0.03) |

| Pain numerical rating scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.4 ± 1.6 (n = 59) | 0.38 ± 1.3 (n = 60) | 0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | 0.4 ± 1.6 (n = 59) | 0.3 ± 1.2 (n = 55) | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.6) |

| 3 mo | 2.3 ± 1.9 (n = 54) | 1.9 ± 1.7 (n = 57) | 0.3 (−0.4 to 1.0) | 2.3 ± 1.9 (n = 54) | 2.0 ± 1.7 (n = 53) | 0.3 (−0.5 to 0.9) |

| 1 yr | 1.6 ± 1.8 (n = 50) | 1.3 ± 1.8 (n = 56) | 0.3 (−0.4 to 0.2) | 1.6 ± 1.8 (n = 50) | 1.3 ± 1.8 (n = 52) | 0.3 (−0.4 to 1.0) |

| 2 yr | 1.5 ± 1.9 (n = 47) | 1.5 ± 1.9 (n = 56) | 0.0 (−0.8 to 0.8) | 1.5 ± 1.9 (n = 47) | 1.5 ± 2.0 (n = 49) | 0.0 (−0.8 to 0.8) |

| Activities of daily living | ||||||

| Baseline | 90% (53/59) | 93% (56/60) | 88% (52/59) | 93% (51/55) | ||

| 3 mo | 69% (37/54) | 68% (39/57) | 69% (37/54) | 68% (36/53) | ||

| 1 y mo | 68% (34/50) | 64% (36/56) | 68% (34/50) | 63% (33/52) | ||

| 2 y mo | 72% (34/47) | 65% (34/52) | 64% (30/47) | 65% (32/49) | ||

There was no significant difference between the groups in any of the analyses.

The Harris hip score, EQ-5D, and pain numerical rating scale data are given as the mean and standard deviation, with the number of patients with available data in parentheses The activities of daily living data are given as the proportion of patients who were fully independent in activities of daily living, with the numerator and denominator in parentheses.

Secondary End Points and Adverse Events

There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of the prevalence of all hip-related complications and reoperations up to 1 year postoperatively. We found 4 hip-related complications in each group, including 1 dislocation and 3 deep periprosthetic infections in the hemiarthroplasty group and 3 superficial infections and 1 nonunion in the total hip arthroplasty group (Table III). Of the 2 patients managed with closed reduction and internal fixation, 1 developed nonunion and underwent reoperation with a hemiarthroplasty. Two of the 3 patients in the hemiarthroplasty group who had deep periprosthetic infections were managed surgically, whereas the third was managed conservatively with antibiotics for 3 months. The surgical procedure was 1-stage revision involving surgical debridement, removal of the prosthesis, and recementing of a new implant (Table III). We found no difference between the groups in terms of the activities of daily living and pain scores during the follow-up period. However, both of these scores deteriorated in both groups (Table II).

TABLE III.

Adverse Events Up to 2 Years After Surgery

| Hemiarthroplasty (N = 60) | Total Hip Arthroplasty (N = 60) | |

| Hip-related complications | ||

| Dislocation | 1 | 0 |

| Superficial infection | 0 | 3 |

| Deep periprosthetic infection | 3 | 0 |

| Non-healing fracture | 0 | 1 |

| Total number of hip complications | 4 | 4 |

| Number of patients with any hip complication | 4 | 4 |

| Reoperation | ||

| Closed reduction | 1 | 0 |

| Surgical debridement and 1-stage revision | 2 | 0 |

| Another major reoperation | 0 | 1 |

| Total number of major reoperations | 2 | 1 |

| General complications | ||

| Pneumonia | 7 | 4 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 1 |

| Myocardial infarct | 1 | 2 |

| Cerebral vascular lesion | 3 | 6 |

| Acute kidney failure | 0 | 1 |

Two patients in each group were bedridden or wheelchair-bound at the 1-year follow-up. During the study period, 26 (47%) of 55 patients in the hemiarthroplasty group and 24 (42%) of 57 patients in the total hip arthroplasty group were able to regain their previous walking function.

Blinding Success

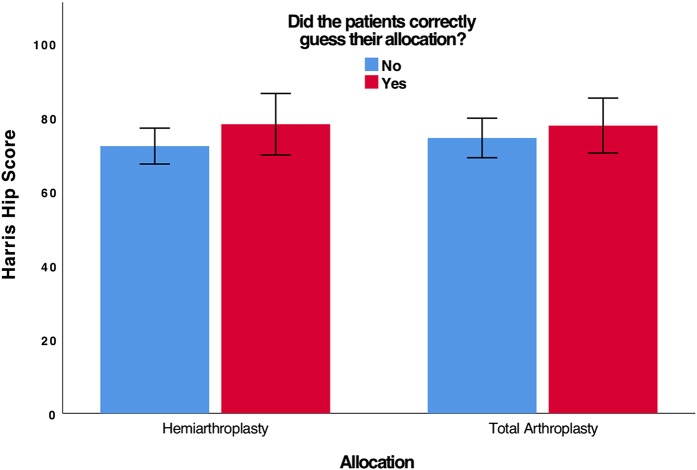

Of the 99 patients who were available at the 2-year follow-up, 30 correctly guessed their allocation, 15 guessed incorrectly, and 54 answered “don’t know” (Table IV). There was no significant difference between the groups when testing for blinding (p = 0.1, chi-square test). In addition, those patients who correctly guessed their allocation did not have a clinically relevant or statistically significant difference in outcome from those who did not (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Bar graph showing the mean HHS (and 95% CIs) for hip function at the 2-year follow-up for the patients who correctly guessed their allocation (n = 30) as compared with those who did not (n = 66).

TABLE IV.

Testing for Blinding, as Assessed by the 99 Patients Who Completed the 2-Year Follow-up

| Actual Allocation (no. of patients) | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty (N = 47) | Total Hip Arthroplasty (N = 52) | |

| What procedure were you allocated to? | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 13 (28%) | 8 (15%) |

| Total hip arthroplasty | 7 (15%) | 17 (33%) |

| “Don’t know” | 27 (57%) | 27 (52%) |

Patients Who Declined Participation

The 63 patients who declined to participate in the study did not differ from the study subjects with regard to sex (p = 0.6), age (p = 0.5), or ASA classification (p = 0.2)22.

Discussion

In this prospective randomized study of octogenarians and nonagenarians with a displaced femoral neck fracture that was treated with hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty, we found no difference at 2 years in any relevant outcome variables. Hip function, health-related quality of life, pain in the operatively treated hip, activities of daily living, and ability to regain previous walking function deteriorated at 2 years in both groups compared with the pre-fracture values.

The strengths of the present study are its prospective, blinded, randomized controlled design, the use of both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, the randomization process stratified by sex to ensure equal sex distributions, and strict adherence to the pre-study-determined hypothesis, outcome measurements, and published study protocol14.

In addition, we included an analysis of how successful we were with the blinding of the patients and also presented the results for patients who chose to not participate in the study. To our knowledge, this is also the first RCT comparing hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in patients ≥80 years of age.

As is the case in many RCTs in medicine, our cohort had a lower mortality compared with non-participants, but the functional results did not differ between participants and non-participants, indicating that our trial had good external validity. We have described these results in a separate report, the first in the orthopaedic literature to evaluate the external validity of an RCT involving patients with hip fractures22.

The main limitation of the present study was the short-term follow-up period. A 2-year follow-up possibly was not sufficient time for the development of acetabular erosion in patients ≥80 years of age, who may have limited activity. Therefore, radiographic measurements of erosion of the acetabular cartilage are not presented but will be performed during later follow-up examinations. Other limitations included the use of a single disease-specific patient-reported outcome measure as the HHS has been shown to be limited by ceiling effect23. The age-related decline due to factors other than hip function might have affected the usefulness of the HHS in the present population. However, the HHS is widely used and has been validated for patients with a femoral neck fracture18.

There have been several RCTs to date comparing hemiarthroplasty with total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients, but the results of those trials have been heterogeneous. Several studies with short and intermediate-term follow-up failed to show any functional difference between hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty, which is consistent with the findings of the present study. van den Bekerom et al., in a study of 252 patients11, demonstrated no difference in hip function between hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty at 1 and 5 years of follow-up. Their findings at the 1-year follow-up concurred with ours, although the dislocation rate in that study was high. We used the direct lateral approach in all patients, whereas those authors used both direct lateral and posterolateral approaches. This factor may explain the difference in the dislocation rate. Avery et al.6 found that the significant functional benefits afforded by total hip arthroplasty over hemiarthroplasty at the 3-year follow-up were no longer present at 7 to 10 years. Tol et al., in another long-term RCT, reported results comparable with those of the present study, with no differences between the total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty groups in terms of hip function, the complication rate, and the revision rate24.

In contrast to our findings, several RCTs with short-term follow-up have shown that total hip arthroplasty is superior to hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of mobile, independent patients5,7-10. Blomfeldt et al.9 found significantly better hip function in the total hip arthroplasty group at 1 year despite no signs of acetabular erosion in any of the patients in the bipolar hemiarthroplasty group. The HHS at the 1-year follow-up was lower in both groups in our study compared with the patients in the study by Blomfeldt et al.9. Similarly, Baker et al.7 found significantly lower hip function and shorter self-reported walking distance in the hemiarthroplasty group compared with the total hip arthroplasty group. Those findings may be explained by the fact that healthy, relatively younger active patients with walking ability were included. Hedbeck et al.10 showed that the difference in hip function in favor of the total hip arthroplasty group that had been previously reported at 1 year persisted and seemed to increase over time through a 4-year follow-up period. The difference in health-related quality of life, which was not significant at 1 year, was statistically significant at 4 years. Mouzopoulos et al.25 found no significant difference at 1 and 4 years of follow-up between hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty groups with regard to functional outcome but recommended total hip arthroplasty for patients >70 years of age who had good cognitive status because of its association with less pain and lower reoperation rates.

Two meta-analyses showed that total hip arthroplasty may lead to lower reoperation rates and better functional outcomes compared with hemiarthroplasty among older patients, but both studies demonstrated a higher dislocation rate in the total hip arthroplasty group26,27. However, the findings were not conclusive, and further studies were recommended. A Cochrane review demonstrated no difference between total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in terms of the level of pain, ambulation, or use of walking aids; however, the evidence was insufficient and further RCTs were recommended26.

In conclusion, we found no difference in outcomes after treatment with either hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in active octogenarians and nonagenarians with a displaced femoral neck fracture up to 2 years after surgery. Hemiarthroplasty is a suitable procedure in the short term for this group of patients.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopaedics at Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

Disclosure: The study was funded by grants from the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A94).

Data Sharing

A data-sharing statement is provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A95).

References

- 1.Parker MJ, Pryor G, Gurusamy K. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures: a long-term follow-up of a randomised trial. Injury. 2010. April;41(4):370-3. Epub 2009 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur—13 year results of a prospective randomised study. Injury. 2000. December;31(10):793-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonardsson O, Sernbo I, Carlsson A, Akesson K, Rogmark C. Long-term follow-up of replacement compared with internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fractures: results at ten years in a randomised study of 450 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010. March;92(3):406-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heetveld MJ, Rogmark C, Frihagen F, Keating J. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: what is the evidence? J Orthop Trauma. 2009. July;23(6):395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keating JF, Grant A, Masson M, Scott NW, Forbes JF. Displaced intracapsular hip fractures in fit, older people: a randomised comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. Health Technol Assess. 2005. October;9(41):iii-iv, ix-x, 1-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avery PP, Baker RP, Walton MJ, Rooker JC, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip replacement and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a seven- to ten-year follow-up report of a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011. August;93(8):1045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker RP, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006. December;88(12):2583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macaulay W, Nellans KW, Garvin KL, Iorio R, Healy WL, Rosenwasser MP; other members of the DFACTO Consortium. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing hemiarthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: winner of the Dorr Award. J Arthroplasty. 2008. September;23(6)(Suppl 1):2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Eriksson K, Söderqvist A, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. A randomised controlled trial comparing bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007. February;89(2):160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedbeck CJ, Enocson A, Lapidus G, Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. Comparison of bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: a concise four-year follow-up of a randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. March 2;93(5):445-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Bekerom MP, Hilverdink EF, Sierevelt IN, Reuling EM, Schnater JM, Bonke H, Goslings JC, van Dijk CN, Raaymakers EL. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a randomised controlled multicentre trial in patients aged 70 years and over. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010. October;92(10):1422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010. August;63(8):834-40. Epub 2010 Mar 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975. October;23(10):433-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sköldenberg O, Chammout G, Mukka S, Muren O, Nåsell H, Hedbeck CJ, Salemyr M. HOPE-Trial: hemiarthroplasty compared to total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly-elderly, a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015. October 19;16:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009. April;42(2):377-81. Epub 2008 Sep 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodén C, Mukka S, Muren O, Eisler T, Boden H, Stark A, Sköldenberg O. High risk of early periprosthetic fractures after primary hip arthroplasty in elderly patients using a cemented, tapered, polished stem. Acta Orthop. 2015. April;86(2):169-74. Epub 2014 Oct 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukka S, Mellner C, Knutsson B, Sayed-Noor A, Sköldenberg O. Substantially higher prevalence of postoperative peri-prosthetic fractures in octogenarians with hip fractures operated with a cemented, polished tapered stem rather than an anatomic stem. Acta Orthop. 2016. June;87(3):257-61. Epub 2016 Apr 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frihagen F, Grotle M, Madsen JE, Wyller TB, Mowinckel P, Nordsletten L. Outcome after femoral neck fractures: a comparison of Harris hip score, Eq-5D and Barthel Index. Injury. 2008. October;39(10):1147-56. Epub 2008 Jul 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Söderman P, Malchau H. Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001. March;384:189-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001. July;33(5):337-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chammout GK, Mukka SS, Carlsson T, Neander GF, Stark AW, Skoldenberg OG. Total hip replacement versus open reduction and internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomized long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012. November 7;94(21):1921-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukka S, Sjöholm P, Chammout G, Kelly-Pettersson P, Sayed-Noor A, Sköldenberg O. External validity of the HOPE-Trial - hemiarthroplasty compared to total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in octogenarians. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wamper KE, Sierevelt IN, Poolman RW, Bhandari M, Haverkamp D. The Harris hip score: do ceiling effects limit its usefulness in orthopedics? Acta Orthop. 2010. December;81(6):703-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tol MC, van den Bekerom MP, Sierevelt IN, Hilverdink EF, Raaymakers EL, Goslings JC. Hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of a displaced intracapsular fracture in active elderly patients: 12-year follow-up of randomised trial. Bone Joint J. 2017. February;99-B(2):250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mouzopoulos G, Stamatakos M, Arabatzi H, Vasiliadis G, Batanis G, Tsembeli A, Tzurbakis M, Safioleas M. The four-year functional result after a displaced subcapital hip fracture treated with three different surgical options. Int Orthop. 2008. June;32(3):367-73. Epub 2007 Mar 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker MJ, Gurusamy KS, Azegami S. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. June 16;6:CD001706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgers PT, Van Geene AR, Van den Bekerom MP, Van Lieshout EM, Blom B, Aleem IS, Bhandari M, Poolman RW. Total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in the healthy elderly: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized trials. Int Orthop. 2012. August;36(8):1549-60. Epub 2012 May 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

A data-sharing statement is provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A95).