Abstract

Striae distansae (SD) or stretch marks are very common, asymptomatic, skin condition frequently seen among females between 5 to 50 years of ages. It often causes cosmetic morbidity and psychological distress, particularly in women and in certain professions where physical appearances have significant importance. Of late, with the increasing emphasis on cosmetic management and awareness, patients approach dermatologists for stretch marks treatment. However, despite several advances, no fully effective treatment has emerged. Unfortunately, there is paucity of the strong evidence in the literature for the effective treatment of striae. A literature search using the terms 'striae distansae (SD or stretch marks’ was carried out in the PubMed, Google Scholar and Medline databases. Only articles related to the treatment were considered and analysed for their data. Commonly cited treatments include topical treatments like tretinoin, glycolic acid, ascorbic acid and various lasers including (like) carbon dioxide, Er:YAG, diode, Q-switched Nd:YAG, pulse dye and excimer laser. Other devices like radiofrequency, phototherapy and therapies like platelet rich plasma, chemical peeling, microdermabrasion, needling, carboxytherapy and galvanopuncture have also been used with variable success. This article reviews all currently accepted modalities and their effectiveness in the treatment of stretch marks.

Keywords: Lasers, striae, treatment

Introduction

Striae distensae (SD) commonly known as stretch marks are visible linear scars which develop in areas of dermal damage as a result of excessive stretching of the skin. They are twice as common in females and are reported in the age group of 5–50 years.[1]

Striae are extremely common and often cause cosmetic morbidity and psychological distress, particularly in women and certain professions. Of late, with the increasing emphasis on cosmetic management and awareness; patients approach dermatologists for striae treatment. However, despite several advances, no fully effective treatment has emerged.

This article will evaluate the existing treatments and their efficacy and provide a concise review of available therapeutic modalities for SD.

Methods of search: A through search of the literature using the words 'striae distensae’, striae rubra, striae alba and stretch marks was carried out in the PubMed, Google Scholar and Medline databases. Articles which focused on the treatment of SD were considered and analysed critically.

Etiopathogenesis

Striae generally develope in various physiological states such as pregnancy, growth spurt during puberty or rapid change in proportion of specific body regions such as in weight lifters, obese or weight loss.[2]

They are also seen in pathological conditions with hypercortisolism like Cushing's syndrome[3] and genetic disorders such as Marfan syndrome.[4] SD sometimes may occur as a side effect related to drugs such as local or systemic corticosteroid therapy[3,5] and anti-retroviral protease inhibitors (indinavir).[6]

The origin of SD is thus multifactorial and exact etiopathogenesis of SD still remains controversial. Primary pathology lays in altered dermal connective tissue framework involving components of extracellular matrix (ECM) namely fibrillin, elastin, fibronectin and collagen.[7,8]

In the initial stages, elastic fibres undergo elastolysis along with degranulation of mast cells.[9] Affected tissue may also show low expression of collagen and fibronectin genes or high proportion of rigid cross-linked collagen, which makes the connective tissue prone to stress rupture.[1]

Other factors like genetic predisposition, mechanical stress, hormones especially corticosteroids (both topical and systemic) also play an important role in causation.[1,3]

On histopathology, in initial stage (i.e., striae rubra (SR), the epidermis is almost normal and dermis is oedematous with perivascular lymphocytic cuffing suggestive of inflammation. As ageing of lesion occurs, i.e. striae alba (SA) epidermis becomes thin, atrophic with blunting of rete ridges and absence of skin appendages.[10]

Clinical features

Early lesions of SD are smooth, raised, irritable and erythematous to bluish in colour, known as SR. As the lesion ages, it flattens, becomes pale and irregular with finely wrinkled surface known as SA; which is usually permanent.[1]

Clinically SD appear as multiple, symmetric, well defined, irregularly linear, red to pale coloured (depending upon the stage) atrophic scars which follows the lines of cleavage and lies parallel to the skin surface.

The pubertal growth spurt induced SD are commonly seen after thelarche. They are present over thighs, buttocks and breasts in girls. In boys, they often develop over lumbosacral region and outer aspect of the thighs. Stretch marks of pregnancy, also known as striae gravidarum (SG);[11] are commonly seen over abdomen, breast and thighs in third trimester. SG lesions are more common in young primigavida and are associated with higher weight gain in pregnancy, large for gestational age babies and increased risk of traumatic vaginal delivery.[12]

Overall striae are generally benign in nature; rarely the bigger lesions may ulcerate or rupture if traumatised.[1]

As explained earlier, multiple pathological changes occur in the dermal connective tissue components as lesions of SD progress from SR to SA stage. They are reflected macroscopically as altered texture, strength and colour of the skin.

The dermal collagen bundles get thinned out with altered orientation of fibres.

Diagnosis of striae is often clinical and straight forward without any need of specific investigation.

Treatment

Striae, while otherwise being harmless, are frequent cause of cosmetic concern or disfigurement leading to distress in the affected individuals especially females. With increasing preference for outdoor activities such as gym and swimming; apparels which reveal part of the riff, midriff or thighs, in the modern women, treatment of striae has become a necessity in many patients.

In adolescents, SD associated with pubertal growth spurt becomes less conspicuous with time and has excellent prognosis as compared to other SD. Other SD, like SG tends to improve to some extent after delivery.[1] Even corticosteroid-induced striae may disappear or become inconspicuous after withdrawal of offending steroid. Hence counselling is an important part of initial management in all cases.

Multiple treatment options have been reported with varying success, from numerous topicals to lasers and energy based devices. However, most available publications are small studies, case reports and very few case-controlled double blind trials. Only a few of these are proven and have evidence, whereas many others are hyped by product manufacturers.

In view of this, it is very important to understand the basis of different therapeutic options and to choose the right modality and ensure proper counselling to the patients to optimise treatment outcome.

Box 1 enumerates the targets of different therapeutic modalities used in SD.[13,14]

Box 1.

Treatment targets of different therapies used in striae distensae

| Induction of dermal collagen production and fibroblastic activity (to improve tissue strength) |

| Reduction of lesional vascularity (especially in SR) |

| Reduction in wrinkling and roughness of skin (to improve texture) |

| Increase in pigmentation (in SA) |

| Increase in elasticity and blood perfusion |

| Improvement in cell proliferation |

| Increased skin hydration and |

| Anti-inflammatory properties |

General measures for prevention of striae

Development of stretch marks may be prevented by avoidance of brisk weight gain or loss; particularly in high-risk groups, e.g., adolescents, athletes and pregnant women.

Dietary modifications and exercise plan were thought to be important for reduction of SD in earlier days. A study conducted by Schwingel et al. has failed to demonstrate effect of any weight loss programme diet and any type of exercise on SD.[15]

Topical treatments

The various topical therapeutic agents used for SD are enlisted in Table 1. Tretinoin and retinoic acid have been found to be useful in several studies.[14,16] In early SD, it is believed to act by stimulation of fibroblasts leading to increase tissue collagen levels. Studies have found it to be effective in SR also, though transient erythema and scaling were most common side effects.[16,17]

Table 1.

Topicals agents used for striae distensae

| Topical agent used | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|

| Tretinoin or retinoic acid | Increase tissue collagen I levels through fibroblastic stimulation |

| Hyaluronic acid | Increase tensile resistance to mechanical forces |

| Trofolastin (Centella asiatica) | Stimulation of fibroblasts and antagonist to glucocorticoid effect |

| Silicone | Skin hydration |

| Acid peels - glycolic acid, trichloroaceticacid (TCA) | Proliferation of fibroblast and stimulate collagen production by fibroblasts |

| Ascorbic acid | Improved collagen production |

| Alphasria | Increasing volume to oppose mechanical atrophy |

| Cocoa butter | Mositurisation |

| Oils - olive oil, almond oil, coconut oil, bio oil | Action by massage and cutaneous hydration |

| Pirfenidone | Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, promote collagenase, fibroblastic activity |

Hyaluronic acid is also found to be effective in SD as it increases collagen production.[18] Other agents used with varying success are trofolastin (Centella asiatica), silicone, glycolic acid, ascorbic acid, alphasria, cocoa butter, olive oil, almond oil, chamomile, coconut oil and bio-oil.[14]

In one study, pirfenidone which is a small synthetic non-peptide having immuno-modulatory as well as anti-inflammatory properties has also been used. It can also modulate collagenase, fibroblastic activity and cytokines in the wound healing process thus found to be effective in SD.[19]

In spite of multiple topical therapies being available for treatment of SD, there are limited numbers of evidence-based scientific studies documenting the efficacy of these agents. The reported efficacy is modest and the drugs need to be used for prolonged periods of time. Therefore, efficacy of topicals in prevention and treatment of SD is questionable.

Procedural therapies

In the recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in minimally invasive non-surgical skin rejuvenation procedures and technologies which offer minimal downtime leading to increased patient compliance. The basic principle on which these therapies are based is induction of controlled inflammation in dermis which results in stimulation of neocollagenesis by recruitment of fibroblast. To be effective in SD, in addition to neocollagenesis, these modalities should also reduce erythema in SR and improve pigmentation in SA. Different procedural therapies used for SD are enlisted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Procedural therapies used for striae distensae

| Type of procedure |

|---|

| Lasers |

| Ablative fractional CO2 10,600 nm |

| Non-ablative fractional Er:YAG 1540 nm |

| Non-ablative 1450 nm diode laser |

| 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser |

| Flash-pumped 585 nm pulsed dye laser |

| Cu bromide laser |

| 308 nm excimer laser |

| Light-based therapies |

| Intense pulsed light |

| UVB/UVA1 combined therapy and targeted phototherapy |

| Infrared light |

| Radiofrequency (or ablative/non-ablative) |

| Non-fractional |

| Fractional |

| Microneedle radiofrequency (MNRF) |

| Galvanopuncture |

| Carboxytherapy |

| Microdermabrasion |

| Platelet rich plasma (PRP) |

| Microneedling therapy or percutaneous collagen induction therapy |

| Chemical peeling |

Lasers

Lasers are the light energy based devices which deliver coherent, cohesive and monochromatic light energy to the skin by acting on specific tissue chromophore. The lasers target different chromophores such as water, haemoglobin and melanin and thus improve overall appearance of SD by increasing collagen production, decreasing vascularity (especially in SR) and by increasing melanin pigmentation.[13,20] Both ablative and non-ablative lasers have been tried with varying success in striae management.

Ablative Lasers

Ablative lasers of wavelength more than 1000 nm are readily absorbed by tissue water, results in cell vaporisation, tissue heating and remodelling.[21] The commonly used ablative lasers for SD are CO2 (10,600 nm) and Er:YAG (2940 nm).[20]

However, ablative lasers are associated with severe erythema, post-procedure pigmentation and prolonged downtime.

In an attempt to combat these shortcomings, the concept of fractional photothermolysis was introduced. In this, the laser beam creates non-contiguous areas of thermal damage having controlled width, depth and density with sparing of adjacent epidermis termed ‘microthermal tissue zones’.[22] Within these areas, localised epidermal necrosis occurs alongside collagen denaturation. Ultimately, the necrotic debris is expelled and neocollagenesis occurs. All this leads to rapid dermal collagen remodelling with sparing of intermittent epidermis, ultimately leading to improvement in these atrophic dermal scars.[23] These devices are thus associated with minimal downtime and are dealt with more detail below.

Fractional CO2 10,064 nm (Fr CO2)

This laser stimulates fibroblast activity, induces dermal tissue remodelling and thus has been successfully used for laser resurfacing of SD.[24] The clinical improvement was also reflected histopathologically as increase in thickness of epidermis and dermis as well as higher immunoreactivity of procollagen type 1.[25] However, multiple sessions were needed.

The use of this laser is associated with erythema, post-treatment pain, crust formation and pigmentary dyschromia which may be a cause of concern in the darker skin types IV and VI.[26,27] Shin et al. in his study proposed the positive effect of succinylated atelocollagen with fractional resurfacing CO2 laser on SD.[28] In another study, monthly fractional CO2 laser sessions were compared with topical therapy regimen comprising 10% glycolic acid + 0.05% tretinoin cream at every night. The former was found to reduce the mean surface area of SD more effectively as compared to the topical therapy.[29] Fractional CO2 laser was more effective in reduction of mature SD than in SR.[27] Treatment outcome of fractional CO2 laser was found to be augmented when used in combination with pulsed dye laser (PDL).[30] In a study comparing ablative laser (fractional CO2) with non-ablative lasers (1540 Er glass laser) in SD, both were found equally effective, but the latter was more patient friendly and better tolerated.[26]

Fractional Er:YAG laser

Variable square pulse Er:YAG laser has been used for resurfacing of the SD. Wanitphakdeedecha et al. has shown efficacy of lower fluence in volumetric reduction of striae.[31] In another comparative study with variable square pulse Er:YAG and Nd:YAG laser investigators have refuted use of either lasers in management of SA.[32] In comparative study of PDL and fractional Er:YAG laser, both were found to be equally effective, though Er:YAG laser was preferred by patients.[33] The laser has also been found effective in ethnic skin especially skin type IV–VI in terms of efficient fractional non-ablative photothermolysis as well as minimal side effect profile. On an average 6–8 sittings at 4 weekly intervals are required to obtain sustainable improvement in dimensions, texture and pigmentation of SD.

Non-ablative Lasers

Erbium glass (Er glass 1540 nm) laser

Erbium glass laser has also been used for fractional photothermolysis. Generally, repetitive treatments (4–6 sessions) are required at 4–6 weeks interval.[23,34,35] The laser (1550 nm) has shown to reduce dimensions of SD with improved elasticity, colour and skin texture; when used by multiple investigators in different striae like SG,[36] breast striae post-augmentation surgery[37] and steroid-induced striae.[38] Stotland et al. has reported overall improvement in dimensions of SD independent of age, gender and skin phototype with the use of 1550 nm, erbium-doped fibre laser; but lesser improvement in dyschromia and texture of striae.[39] Most common adverse events were transient pain, post-treatment erythema, oedema and dyschromia.[40] In another study by Wang et al. two different wavelengths 1540 and 1410 nm of lasers were compared; both were found efficient in SD reduction without any significant difference between the two.[41] Tretti and Lavagno has used a different frequency 1565 nm (Resur FX) laser in stretch marks which demonstrated improved pigmentation, volume and textural appearance of SD.[42]

Pulsed dye laser

Initial stages of SR are marked by erythema due to presence of dilated blood vessels and the haemoglobin in these microvasculature acts as a chromophore for PDL, making it a good treatment candidate for SD management. McDaniel and colleagues[43] have used PDL at different energy densities for SD and found improvement in appearance of the striae with higher energy. They concluded it was due to increased dermal elastin and collagen production. In other studies there was limited improvement noted in SA as compared to SR, the overall improvement was more in colour. Study by Nehal et al.[44] had noticed only mild subjective improvement in texture of mature SD with the use of PDL but it failed to show the same changes histopathologically. In darker skin types (IV–VI) melanin also competes with haemoglobin as a target for PDL, thus the use of this laser increases the risk of pigmentation post-therapy.[45] There are multiple comparative studies performed with PDL versus intense pulsed light (IPL),[46] fractional CO2[27] and Er:YAG[33] lasers; which concluded that it is better than IPL but not superior to fractional ablative lasers. In one study when fractional CO2 and PDL were used together, it was found that the combination of two lasers is superior to the single modality.[30]

308 nm Excimer laser

Excimer laser has a wavelength in the narrow-band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) light spectrum. As compared to other lasers, excimer laser specifically acts by increasing pigmentation of SA and hence are thought to be useful in striae atrophicans.[47] A study conducted by Goldberg et al. on the use of excimer laser for SA found cosmetically significant pigmentation of SA with repetitive sessions.[48] In a further comparative study (2005), the same author has investigated the use of UVB light therapy and the excimer laser in SD and found repigmentation of SD with both the light as well as laser. On histopathology and electron microscopic study, excimer laser was found to cause hypertrophy and hyperplasia of melanocytes leading to increase melanin pigmentation without any improvement in dermal atrophic scarring.[49] Other studies have also confirmed this finding in SA as well as in hypo-pigmented scars. However, in study conducted by Ostovari et al. use of excimer laser showed very weak results along with splaying of the pigment to surrounding normal skin as a major side effect.[50] All the reported changes are short term and not permanent in nature, and hence multiple maintenance treatments are necessary.[49,51]

Nd:YAG 1064 nm

The neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet has affinity for all the chromphores relevant to SD, viz. Hb, water and melanin. Goldman et al. have used it successfully for SR.[52] In another study by Elsaie with the use of two different fluences, investigators reported significant improvement in SA at higher energy of 100 J/cm2, while SR responded better with 75 J/cm2 (four sessions).[53] An Egyptian study by El-Ramly et al. failed to show any statistically significant clinical improvement in SD after four sittings of Nd:YAG laser.[54]

Diode laser

The 1450-nm diode laser has been shown to increase dermal collagen but it has been reported only once in the literature for the management of SD. In a trial by Tay, three laser sessions with increasing energy failed to show any improvements in SD but there were high rates of adverse events like pigmentary dyschromia and erythema noted.[55]

Copper-Bromide Laser

Copper-bromide laser of wavelength 577 nm is more selective for haemoglobin than PDL and thus was also tried for SD management. Longo et al.[56] have used it with fluence of 4–8 J/cm2 in 15 patients of striae and noted moderate improvement in the lesions but the results were inconsistent. They observed transudation, crusting and scabbing as adverse effects.

Even though the lasers are thought to have role in the SD, body's normal healing process also goes hand in hand with it, which might be contributing to the results of the lasers.[57]

Summary of findings of laser

Although a variety of lasers have been used in SD, results are inconsistent. Fractional ablative and non-ablative lasers perhaps have shown the maximum beneficial outcome.

Radiofrequency

The non-ablative and fractional microneedle radiofrequency (MNRF) devices have been recently used for tightening of the skin with significant efficacy and safety profile. Higher-energy fluences generated by radiofrequency (RF) current by coupling method are delivered to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue without causing damage to the epidermis. This transmitted electrical energy upon reacting with the skin's impedance is converted to homogenously distribute thermal energy, which in turn leads to stimulation of fibroblasts with contraction and denaturation of fibrillar collagen structure. All these changes promote neocollagenosis, neoelastogenesis and changes in ECM.[58] All types of RF devices like monopolar,[59] bipolar,[60] tripolar[61] and multipolar[58] have been successfully used in treatment of SD. A study conducted by Montesi et al., has shown that multiple sessions of bipolar RF are highly effective in SD management showing improvement on clinical, histopathology and immunohistochemistry.[60] Sometimes with higher fluences, erythematous rashes, ecchymosis or occasional blistering are observed. Average number of sittings required in RF is 3–6, performed at 4 weekly intervals. Investigators have used this technology in conjunction with other modalities like PDL,[59] autologous PRP,[62] pulsed magnetic fields,[63] infrared (IR) light therapy[64] as well as topical like retinoic acid[65] and found it to be more efficacious than RF alone in management of SD. The fractional method of delivering heat energy to the tissue has also been used in RF devices for better penetration of thermal energy to the target area with safety. Pongsrihadulchai et al. have found statistically significant reduction in dimensions and total surface area of SD with nano-fractional RF.[66] These changes were reflected histopathologically by increase in average mean number of collagen and elastin bundles. A fractional ablative micro-plasma RF roller device (by Alma lasers, Israel) for SD was used by Mishra et al. in five patients; the study concluded that there was improvement in the appearance of abdomen striae with this newer device.[67]

Platelet rich plasma

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) is a concentrated solution of plasma containing various growth factors and protein, injected intra dermally and acts by augmenting dermal elasticity by stimulation of ECM and inducing synthesis of new collagen. It has been used alone as well as in combination with RF,[62,68] carboxytherapy,[69] ultrasonography[68] and found to have synergistic effect in the treatment of SD. In a split comparative study of PRP versus carboxytherapy done once a month in 20 patients of SA by Hodeib et al.[69] both were found effective; with carboxytherapy being superior to PRP. Gamil et al.[70] in a comparative study of PRP versus 0.1% tretinoin cream found it to be more effective than tretinoin for SA. However, this is a recent modality and the results need to be confirmed in larger studies.

Microneedling therapy or percutaneous collagen induction therapy

In this minimally invasive method, small needles are used to create micro channels extending to the papillary dermis. This induced inflammation stimulates dermal wound healing by increasing collagen and elastin synthesis.[71] Aust et al.[72] and Park et al.[73] have independently used this therapy and reported marked improvements in appearance and texture of SD. Khater[74] et al. compared microneedling with fractional CO2 laser, while Nasser et al.[75] used microneedling versus microdermabrasion (MDA) with sonophoresis; both studies found microneedling/percutaneous collagen induction therapy more effective than the other two. Averages three sessions of microneedling treatment at 4 weekly intervals are needed.

Microdermabrasion

The procedure of micro resurfacing uses aluminium oxide crystals which causes mechanical ablation of damaged skin leading to inflammatory cascade. Even with a single treatment session there is an elevation of transcription factors, cytokines [tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-β (IL-β)], matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)-1,3,8 and increased type 1 procollagen formation.[76] A study done by Abdel-Latif et al.[77] showed good-to-excellent response in 20 subjects of SR with monthly sessions of MDA for 5 months. The histochemical analysis showed upregulation of type I procollagen mRNA. Mahuzier[78] states that 10–20 sessions of MDA done at monthly interval lead to epidermal thickening as well as more collagen and elastic fibres in the dermis. The procedure is said to be having no efficacy in hypodermic rupture and it may cause post-inflammatory pigmentary changes as an adverse effect. A comparative study of MDA versus topical tretinoin in early SD by Hexsel et al.[79] showed both modalities to be equally efficacious. However, MDA is associated with lesser side effects and better patient compliance.

Intense pulsed light

IPL is a type of non-laser visible light-based device which uses high intensity, non-coherent, filtered flash lamp, with a broadband frequency spectrum of around 500–1200 nm. Studies investigating use of IPL 2–4 weeks apart from five sessions in SD have found significantly increased amide1 and beta sheets along with dermal collagen on histopathology and synchrotron IR microspectroscopy.[80,81] In a comparative study by Mausin et al.[82] on two different IPL wavelengths, 590 nm was found to be more effective in reducing erythema and dimensions of SD than 695 nm. However, in comparative studies of IPL versus lasers like fractional CO2[83] and PDL[46,84] the lasers proved to be superior.

Miscellaneous Light Based Therapies (other than Lasers) for SD

1. UVB (296–315 nm) and UVA1 (360, 370 nm)

A combined UVB and UVA1 wavelength emitting high-intensity light device model with wavelength peaks at 313, 360 and 420 nm was used in SD by Sadick et al.[85]

In this study greater than 51% improvement in SA pigmentation was reported after weekly (maximum 10 weeks) phototherapy sessions in all nine study participants. Transient hyperpigmentation of striae was seen in almost half the subjects as an adverse event.[85] On biopsy it failed to show any effect on collagen remodelling, thus limiting its efficacy only for repigmentation of SA.

2. IR light

Thermal energy from IR light is known to cause collagen remodelling and neocollagenesis effects. Trelles et al.[86] in his study used IR device to deliver high fluences with high frequency stacked pulses in 10 patients and observed objective improvement in SD did not match visual observations where both physician and patients did not appreciate much clinical benefit.

Chemical peeling

Applications of chemical agents are thought to induce inflammatory response, with subsequent neocollagenosis. The most commonly used agents are trichloroacetic acid, retinoic acid and glycolic acid (GCA).[87,88] Post-inflammatory pigmentary changes and mild irritation are the most common adverse events. Chemical peeling is a cost effective option for treating wider surface area of SD.

Galvanopuncture

In this therapy low level direct micro current is applied to the body with the help of needles to reduce the oxidative injury with subsequent collagen production. Its use in SA was investigated by Bitencourt[89] et al. which demonstrated substantial clinical improvements in 32 SD patients after 10 sessions. Ferreira et al.[90] has compared galvanopuncture versus dermabrasion; he found both treatments showed improvement in SD but the difference was statistically insignificant.

Carboxytherapy

In this procedure, CO2 gas is injected subcutaneously at the depth of 5–6 mm in striae, at weekly interval for 3–12 sessions (depending upon the age of striae). This stimulates blood circulation and increases the release of oxygen by means of oxyhaemoglobin. It also activates the synthesis of collagenase, elastin and hyaluronic acid by stimulation of fibroblast function.[91]

Study performed by Podgórna et al.[92] demonstrated increase skin elasticity, decrease in SD dimensions and improved aesthetic appearance on cutometric assessment post carboxytherapy. The therapy is associated with moderate pain or discomfort and haematoma formation. However, this modality is controversial and cannot be therefore recommended as a routine treatment.

Practical approach

The above review suggests that while multiple modalities have been documented to be of use, no single treatment is fully satisfactory [Table 3 and Box 2]. The studies are small with lower evidence levels and hence there are no standard guidelines available for management. From the evidence presented, it would appear that fractional laser and fractional MNRF should be the first line of management, but cost of these treatments and the large areas usually involved in stretch marks would be limiting factors. In such cases, peels or derma rollers with PRP may be a cheaper alternative.

Table 3a.

Different therapies used for striae distensae

| Type of modality used in study | Type of study | Machine specifications | Frequency and total no of sittings | Results and remarks | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional ablative CO2 laser[25] | Retrospective cohort study | 10,600 nm at 10 mJ/MTZ | Single session Retrospectively reviewed | Almost 60% of patients showed ≥50% clinical improvement in SA Most of the patients were very satisfied A/E - PIH, pruritus, crusting, oozing, erythema | 4 |

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser[31] | RCT | 1550-nm Er:YAG | 1-2 sessions with 4 week intervals | Decrease erythema index, melanin index of the treated SD lesions Skin elasticity was partially normalised with increase in epidermal thickness, collagen and elastic fibre A/E- mild, transient pain and hyperpigmentation | 2 |

| 1550 nm non-ablative fractional Er glass laser[33] | Case series | Moderately high-energy sessions of 1550 nm | 5 sessions at 4 weeks interval | Dimensions of both SA and SR were decreased at 1 month and 1 year after treatment in comparison to before | 4 |

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser[34] | Prospective cohort study | 1550 nm at 80-100 mJ/MTZ | 4-8 sessions at 4-week intervals | Mean clinical improvement of~80% after an average of 6-7 sessions Mean patient satisfaction score of 8.2/10 A/E - PIH | 4 |

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser[35] | Cross-sectional study | 1540 nm at 70 mJ/MTZ | 3-6 sessions at 1-month interval | 50% of patients showed clinical improvement after 3 sessions and remaining 50% showed after 4-6 sessions A/E - erythema, oedema | 4 |

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser[36] | RCT | 1550 nm at 12-18 J/cm2 | 6 sessions with 2-3 week intervals Untreated site acted as controls | 63% patients had almost 50% improvement Improvement in striae dimensions≤50% improvement was observed in texture and colour of the striae A/E - erythema, oedema, blistering | 1 |

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser[38] | RCT | Abdomen divided into 2 parts treated with 1540 nm at 50 J/cm2 vs 1410 nm at 30 J/cm2 | 6 treatments at 3-6-week interval | All patients demonstrated clinical improvement with histopathology showing increased epidermal thickness, dermal thickness and collagen and elastin density 28% of 1410-nm treated and 33% of 1540-nm treated groups had good or excellent improvements; 71.4% and 28.6% of patients were very satisfied and moderately satisfied, respectively No significant differences between lasers A/E - 1540-nm laser - pain and 1410-nm laser - PIH, pruritus | 2 |

| PDL[41] | RCT | 585 nm Four treatment protocols (fluence): 1=10 mm, 2.5 J/cm2; 2=10 mm; 3 J/cm2, 3=7 mm, 2 J/cm2; 4=7 mm, 4 J/cm2 untreated striae in same patient acted as controls | Single session | Improved aesthetic appearance and skin shadowing with all protocols Best results observed with higher fluence, i.e., 10-mm spot size+3 J/cm2 A/E - purpura, erythema, hyper-hypopigmentation | 2 |

| PDL[43] | RCT | 585 nm at 3 J/cm2 | Two treatments 6 weeks apart Untreated striae as controls | No significant differences in striae area Colour improvement in SR but not in SA A/E - PIH | 2 |

| 308 nm excimer laser[46] | RCT | 308 nm at 150-900 J/cm2 | Up to 15 sessions | Almost 100% patients achieved darkening and improved appearance of striae | 2 |

| XeClexcimer laser[49] | RCT | 308 nm | Up to 10 sessions with weekly intervals | 80% of patients showed very poor results, without any satisfaction | 2 |

| Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser[50] | Comparative RCT | Striae divided into 3 sections and treated with 1064 nm at 75 J/cm2 vs 100 J/cm2 vs control 5 mm spot size and 15 ms pulse duration | 4 treatments at 3-week interval | Histopathological and clinical improvement in length and width of striae was seen SA showed better response to 100 J/cm2 and SR responded better with 75 J/cm2 | 2 |

| Long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser[52] | Comparative RCT | 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser | 4 treatments at 4-week interval | Some clinical and histopathological improvement in SD, but it was not statistically significant | 2 |

| 1450 nm diode[55] | RCT | 1450 nm at 4, 8 and 12 J/cm2 | Three sessions with 6-week intervals | Patients failed to show any improvement A/E - erythema, PIH | I |

| Tripollar RF[59] | Case control | 40-50 W | Six sessions with weekly intervals | Improvement of 25-50% and 51-75% in 38.2% and 11.8% of patients, respectively Patients were slightly satisfied, satisfied and very satisfied (12%, 23% and 65% of patients, respectively No significant differences in striae surface smoothness A/E - occasional pinching, sensation during treatment | 4 |

| Nano-fractional RF[66] | Case control | - | 3 sessions 4 week interval | The total surface area and the width and the length of striae alba significantly decreased from the baseline Average mean number of collagen and elastin bundles was significantly increased A/E - PIH | 3 |

| Ablative fractional microplasma RF[67] | Case control | - | Four sessions every 2 weeks | Mean severity score improved by 20% Mean score from patient assessment was 2.4 (≥50%) (good to very good) A/E -erythema, oedema | 4 |

| PCT[72] | Case control | Disk microneedle therapy system (DTS) | 3 sessions with 4-week intervals | Marked to excellent improvement in 43.8% with minimal-to-moderate improvement in remaining patients | 4 |

| Microdermabrasion[76] | RCT | 5 sessions at weekly intervals Other half of body acted as control | Good to excellent (i.e ≥50%) improvement in 50% and mild-to-moderate improvement in the rest Greater improvement in SR Increased type 1 procollagen at mRNA levels in treated striae A/E - PIH, erythema | 2 | |

| IPL[80] | Case control | 535, 550 and 580 nm at 25-35 J/cm2 | Five sessions with 3-4 week interval | Increased collagen, amide1 and beta sheet expression after IPL treatment A/E=stinging sensation | 4 |

| IPL[81] | RCT | 650 nm at 13-15.5 J/cm2 vs 590 nm at 13-14.5 J/cm2 | Five sessions with 2-week intervals Different wavelengths used on opposite sides of body | Significant reductions in length and width with both treatments Significant reduction in erythema with 590-nm wavelength along with superior patient Satisfaction scores A/E=erythema, pain, burning, PIH (all more common with 590-nm wavelength) | 2 |

| UVB/UVA1 light therapy[85] | RCT | UVB: 296-315 nm 1 UVA: 360-370 nm at 45-400 mJ/cm2 | Biweekly treatments for a maximum of 10 treatments | After final treatment, 5 patients had 100% pigmented striae (hyperpigmented), 3 had 76-100%, and 1 had 51-75% improvement After 12 weeks, 2 patients had 51-75% improvement, 3 had 26-50% improvement and 4 had 0-25% improvement Increase in elastic fibre to collagen ratio in 1 patient A/E -erythema, PIH | 2 |

| TCA-based easy peel solution 1 post peel cream[88] | Case control | TCA: 50% | Up to 8 treatments monthly | Almost all had a 60-75% improvement with reduced depth of striae | 4 |

Box 2.

Level of evidence study design

| 1 Randomised, controlled trial, systematic review with meta-analysis |

| 2 Non-randomised, controlled trial, prospective, comparative cohort trial |

| 3 Case-control study, retrospective cohort study |

| 4 Case series cross-sectional study |

| 5 Expert opinion case reports (Quality rating scheme modified from the Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine for ratings of individual studies) |

Table 3b.

Comparative analysis of different therapies used for striae distensae

| Type of modality used in study | Type of study | Machine specifications | Frequency &total no of sittings | Results and remarks | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional non-ablative Er glass laser vs fractional ablative CO2 laser[27] | Comparative RCT | Er: glass laser: 1550 nm at 50 mJ CO2 laser: 10,600 nm at 40-50 mJ | 3 sessions at 4-week intervals | Clinical improvements was observed in 90.9% of striae in both treatment groups | 2 |

| Increased skin elasticity and reduced width of striae with both treatments from baseline | |||||

| Increased epidermal thickness and collagen and elastic fibres with both lasers | |||||

| No statistically significant difference in response between either laser | |||||

| A/E - pain during treatment, PIH and crusting were more with the CO2 laser | |||||

| 585 nm PDL and the short pulsed CO2 laser[27] | RCT | PDL: 585 nm at 3 J/cm2 CO2 laser: 350 mJ and 400 mJ | Single session Striae split into 3 areas and treated with both lasers and 1 control area | No improvement with either treatment | 2 |

| Succinylatedatelocollagen or placebo vs succinylatedatelocollagen or placebo + ablative fractional CO2 vs ablative fractional CO2 laser[28] | Comparative RCT | CO2 laser: 50 mJ Abdomen divided into 3 areas; placebo or collagen applied twice a day | 3 laser sessions performed every 4 weeks | Increased epidermal thickness and erythema and melanin index in all laser irradiated sites but no significant differences between laser alone vs combination | 2 |

| A/E - erythema, PIH, pruritus | |||||

| Fractional ablative CO2 vs GCA + tretinoin[29] | Comparative RCT | Group 1 - Fr CO2-10,600 nm at 16 J/cm2 vs Group 2-10% GCA + 0.05% tretinoin daily | 5 sessions with 2-4-week intervals; GCA + tretinoin | Significantly higher clinical improvements in striae surface area in laser group compared to topicals | 2 |

| Patient satisfaction was significantly higher in laser group | |||||

| A/E - PIH | |||||

| Fractional CO2 laser vs combination of PDL + fractional CO2 laser[30] | Comparative RCT | Group 1- fractional CO2 laser Group 2 - PDL + fractional CO2 laser, Settings -- Fr CO2 - ultra pulse, 10,600 nm, energy-140 mJ; pulse duration: 20-9540 μs, fluence: 16±2 J/cm2; PDL (N-lite) 5-7 J/cm2; pulse duration -0.5 ms, spot size - 7 mm |

Group 13 sessions at 4 week; Group 2 - fractional CO2 laser (3 sessions) and PDL (2 sessions) alternately, with 2-week intervals (the first session was fractional CO2 laser) | Mean surface area decreased significantly in both groups | 2 |

| Combination of PDL and fractional CO2 laser was more effective | |||||

| PDL vs IPL[46] | Comparative RCT | PDL: 595-nm at 2.5 J/cm2; IPL: 565 nm at 17.5 J/cm2 | Five sessions with 4-week intervals | Decreased striae width and improved skin texture with both modalities | 2 |

| SR showed better response vs SA | |||||

| PDL induced higher levels of collagen expression | |||||

| A/E - PIH erythema, pain, itching with both treatments | |||||

| XeCl excimer laser vs UVB light[49] | Comparative RCT | XeCl: 308 nm UVB: 290-320 nm | Up to 10 treatments | All patients showed increase in melanin and melanocytes with both treatments | 2 |

| Multipolar RF+pulsed magnetic field[63] | Comparative | - | 6 sessions | ~80% patients noticed visible improvements in SD | 4 |

| Significant mean reduction in length and width of 1.031 cm and 0.160 cm, respectively | |||||

| Bipolar RF+IR light vs fractional bipolar RF vs fractional bipolar RF + bipolar RF+IR light[64] | Comparative RCT | Bipolar RF+IR light: 100 J/cm2 Fractional bipolar RF: 50-65 mJ/pin Abdomen divided into quadrants with one acting as a control | Monthly sessions for 3 months | Decrease of 21.64% in striae depth with the combined approach of all 3 treatments vs 1.73% increase in control areas | 1 |

| No significant differences in striae width | |||||

| Greater clinical improvement with combined approach of all 3 treatments vs control areas | |||||

| More reticulated pattern of collagen fibres in combination treated and fractional bipolar RF-treated areas | |||||

| Thicker reticular dermis collagen fibres in all treatment areas | |||||

| A/E - bipolar RF: transient crusts, PIH. Mild pruritus with all treatments | |||||

| Ablative fractional RF+tretinoin cream+acoustic pressure wave US vs ablative fractional RF[65] | Comparative RCT | RF: 45 W Tretinoin: 0.05% US: 50 Hertz 1 80% intensity | 4 sessions every 4 weeks Topical tretinoin daily | All patients in combined treatment group showed clinical improvement | 2 |

| Four patients in RF-alone group did not show any improvements | |||||

| All patients in combined treatment group rated improvement between 76-100% vs 25% in RF-alone group | |||||

| Creation of micro channels in epidermis with reaching dermoepidermal junction with combined approach | |||||

| A/E - erythema, oedema and burning sensation in both groups PIH with RF only | |||||

| Plasma fractional RF+PRP+US[68] | Case control | RF: 40-45 W | Three sessions with 3-week intervals | Excellent improvement in 33%; 38.9%, very good; 22.4%, good and 5.6%, mild | 4 |

| Average reduction in width of striae from 0.75 mm to 0.27 mm. Patients were very satisfied with treatment | |||||

| Significant increases in dermal collagen and elastic fibres A/E=PIH | |||||

| Carboxy therapy vs PRP[69] | Case control | PRP injection in their right side (group A) and carboxy therapy session in their left side (group B) | Every 3-4 weeks for 4 sessions | Significant improvement in striae alba in both groups after than before treatment. | 4 |

| No significant difference between both groups as regards either percentage of improvement, response (grading scale) or patient satisfaction | |||||

| Increased fibronectin expression with carboxy therapy than PRP | |||||

| PRP vs tretinoin[70] | RCT | Half of the selected striae were treated with PRP intralesional injection. The other half was treated by topical tretinoin | - | Statistically significant improvement in the SD treated with PRP and topical tretinoin cream | 2 |

| The improvement was more in the SD treated with PRP injections. Collagen and elastic fibres in the dermis were increased in all biopsies after treatment | |||||

| PCT vs fractional ablative CO2[74] | RCT | PCT: Laser: 10,600 nm at 100 W | Both the treatments were given as 3 sessions with 4-week intervals | Clinical and histopathological improvements in 90% of PCT-treated group vs 50% in laser treated group | 2 |

| PCT vs MDA with sonophoresis[75] | RCT | PCT andmicrodermabrasion | PCT: 3 sessions with 4-week intervals Microdermabrasion: 10 sessions over 5 months | Clinical as well as histopathological improvements in 90% of PCT-treated group vs 50% in microdermabrasion with sonophoresis treated group | 2 |

| Superficial dermabrasion vs topical tretinoin[79] | Comparative RCT | Tretinoin (0.05%) daily Dermabrasion weekly |

Topical application on daily bases vs dermabrasion weekly Both for 16 weeks | Clinical improvements with significant reductions in length and width of striae in both groups but no significant differences between treatments | 2 |

| Reduction in elastolysis, collagen fragmentation and epidermal atrophy in dermabrasion group | |||||

| A/E - pruritus, erythema, burning sensation, scaling/crusting, pain, swelling, papules | |||||

| All present in both groups | |||||

| Fractional ablative CO2 laser vs IPL[83] | RCT | CO2 laser: 10,600 nm at 40 mJ IPL: 590 nm at 20-30 J/cm2 | FrCO2-5 sessions with 1-month intervals IPL - 10 sessions twice weekly for 5 months | In the laser and IPL groups, 80% and 32% were deemed to have 50% improvement, respectively | 2 |

| Significant improvements in striae width in both groups but no significant changes in striae length | |||||

| In the laser group, 80% of patients were satisfied vs 20% in the IPL group | |||||

| A/E - erythema, burning, pruritus, PIH | |||||

| PDL vs IPL[84] | Case control | PDL-585 nm | 5 sessions with a 4-week interval between | Decreased striae width, improved skin texture, increased collagen expression after PDL and IPL | 4 |

| PDL induced the expression of collagen I in a highly significant compared with IPL | |||||

| Results were more in SR compared to SA | |||||

| 20% glycolic acid/0.05% tretinoin vs 20% glycolic acid/10% L-ascorbic acid[87] | Comparative RCT | GCA: 20% tretinoin: 0.05% Daily for 12 weeks to opposite sides of abdomen or thigh | Clinical and histological improvements with both regimens but no differences between individual treatments | 2 | |

| Tretinoin regimen increased reticular and papillary dermal elastin content | |||||

| A/E- mild irritation, dermatitis |

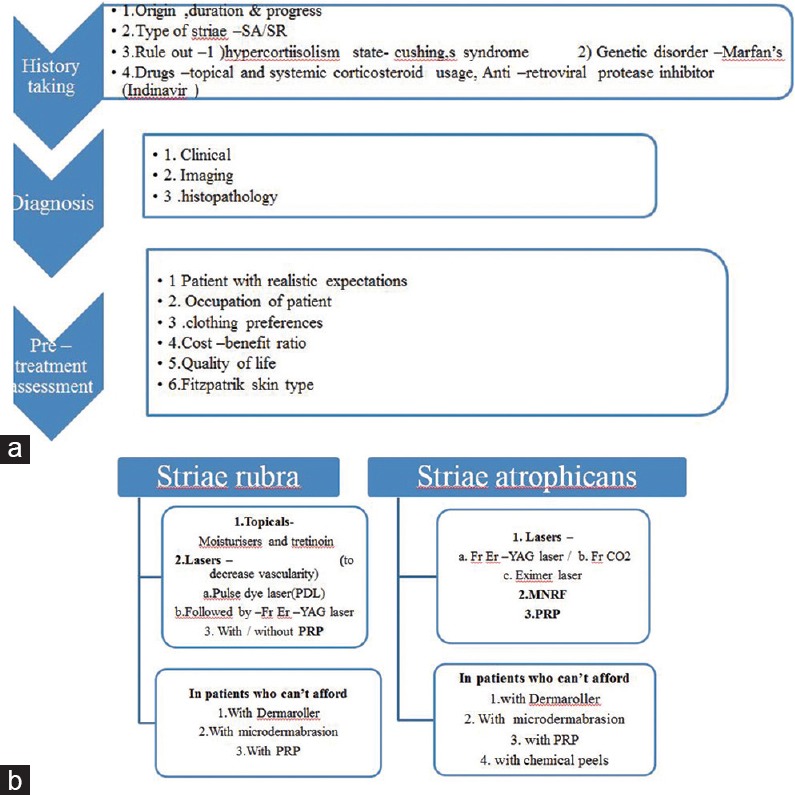

Treatment of SD needs to be tailored to the emotional needs of the person, area of involvement and occupation. It should be made clear during counselling that as of now, none of the treatments can provide complete clearance and multiple sessions are always needed. The efforts should be to use topical therapies in combination with procedural modalities. The authors have made an effort to show these principles in the approach for management in below flow charts [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1.

(a) Flowchart for management of striae distensae pre-treatment workup. (b) Flowchart for management of striae distensae – practical approach

Conclusion

To offer an effective treatment of SD it is important to perform a complete evaluation of a patient including taking proper history, assessing type of SD and skin type of patient. Even in a patient who comes with realistic expectations, finding an effective treatment is often challenging for the treating physician.

There are various therapeutic strategies available, but so far no single modality is found solely effective. Multiple sessions using different therapeutic modalities targeting skin at different levels are often needed.

In future, more research with properly designed clinical trials with large sample size of patients, having longer follow-up periods and comparing different modalities are expected to address the issue of optimum management of SD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lovell CR. Acquired Disorders of Dermal Connective Tissue - Striae in Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. In: Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. 9th ed. Chichester UK: 2016. pp. 96.9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammar NM, Rao B, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Adolescent striae. Cutis. 2000;65:69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuster S. The cause of striae distensae. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1979;59:161–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agg B, Benke K, Szilveszter B, Polos M, Daroczi L, Odler B, et al. Possible extracardiac predictors of aortic dissection in Marfan syndrome. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuutinen P, Riekki R, Parikka M, Salo T, Autio P, Risteli J, et al. Modulation of collagen synthesis and mRNA by continuous and intermittent use of topical hydrocortisone in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:39–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darvay A, Acland K, Lynn W, Russell-Jones R. Striae formation in two HIV-positive persons receiving protease inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:467–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson RE, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, Jones CJ, Polson DW, Kielty CM, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tung JY, Kiefer AK, Mullins M, Francke U, Eriksson N. Genome-wide association analysis implicates elastic microfibrils in the development of nonsyndromic striae distensae. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2628–31. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheu HM, Yu HS, Chang CH. Mast cell degranulation and elastolysis in the early stage of striae distensae. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:410–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1991.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertin C, Lopes-Da Cunha A, Nkengne A, Roure R, Stamatas GN. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo . Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81–6. doi: 10.1111/srt.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muzaffar F, Hussain I, Haroon TS. Physiologic skin changes during pregnancy: A study of 140 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:429–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahman AJ, Finan MA, Emerson SC. Striae gravidarum as a predictor of vaginal lacerations at delivery. South Med J. 2000;93:873–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hague A, Bayat A. Therapeutic targets in the management of striae distensae: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ud-Din S, McGeorge D, Bayat A. Topical management of striae distensae (stretch marks): Prevention and therapy of striae rubrae and albae. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:211–22. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwingel AC, Shimura Y, Nataka Y, Kazunori O. Exercise and striae distensae in obese women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:S33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangel O, Arias I, Garcia E, Lopez-Padilla S. Topical tretinoin 0.1% for pregnancy-related abdominal striae: An open-label, multicenter, prospective study. Adv Ther. 2001;18:181–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02850112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elson ML. Treatment of striae distensae with topical tretinoin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:267–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1990.tb03962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Draelos ZD, Gold MH, Kaur M, Olayinka B, Grundy SL, Pappert EJ, et al. Evaluation of an onion extract, Centella asiatica, and hyaluronic acid cream in the appearance of striae rubra. Skinmed. 2010;8:80–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koontz JP, Parco J. A pilot study: Pirfenidone, 8% (KitosCell) as a treatment for striae distensae (Doctoral dissertation of striae rubra) Skinmed. 2010;8:80–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldahan AS, Shah VV, Mlacker S, Samarkandy S, Alsaidan M, Nouri K. Laser and light treatments for striae distensae: A comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:239–56. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altshuler GB, Yaroslavsky I. Burlington: Palomar Medical Technologies; 2004. Absorption Characteristics of Tissues as a Basis for the Optimal Wavelength Choice in Photodermatology; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tierney EP, Kouba DJ, Hanke CW. Review of fractional photothermolysis: Treatment indications and efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1445–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bak H, Kim BJ, Lee WJ, Bang JS, Lee SY, Choi JH, et al. Treatment of striae distensae with fractional photothermolysis. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macedo OR, Bussade M, Salgado A, Ribeiro MM. Fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of striae distensae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:AB204. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SE, Kim JH, Lee SJ, Lee JE, Kang JM, Kim YK, et al. Treatment of striae distensae using an ablative 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser: A retrospective review of 27 participants. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1683–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang YJ, Lee GY. Treatment of Striae distensae with nonablative fractional laser versus ablative CO (2) fractional laser: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:481–9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nouri K, Romagosa R, Chartier T, Bowes L, Spencer JM. Comparison of the 585 nm pulse dye laser and the short pulsed CO2 laser in the treatment of striae distensae in skin types IV and VI. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:368–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.07320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin JU, Roh MR, Rah DK, Ae NK, Suh H, Chung KY. The effect of succinylated atelocollagen and ablative fractional resurfacing laser on striae distensae. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:113–21. doi: 10.3109/09546630903476902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naein FF, Soghrati M. Fractional CO2 laser as an effective modality in treatment of striae alba in skin types III and IV. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:928–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naeini FF, Nikyar Z, Mokhtari F, Bahrami A. Comparison of the fractional CO2 laser and the combined use of a pulsed dye laser with fractional CO2 laser in striae alba treatment. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:184. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.140090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wanitphakdeedecha R. Treatment of striae distensae with variable square pulse Erbium: YAG laser resurfacing. J Laser Health Acad. 2012;1:S15. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gungor S, Sayilgan T, Gokdemir G, Ozcan D. Evaluation of an ablative and non-ablative laser procedure in the treatment of striae distensae. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:409–12. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.140296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gauglitz GG, Reinholz M, Kaudewitz P, Schauber J, Ruzicka T. Treatment of striae distensae using an ablative Erbium: YAG fractional laser versus a 585-nm pulsed-dye laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:117–9. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.854621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim BJ, Lee DH, Kim MN, Song KY, Cho WI, Lee CK, et al. Fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of striae distensae in Asian skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:33–7. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Angelis F, Kolesnikova L, Renato F, Liguori G. Fractional nonablative 1540-nm laser treatment of striae distensae in Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV: Clinical and histological results. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:411–9. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11402493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gokalp H. Long-term results of the treatment of pregnancy-induced striae distensae using a 1550-nm non-ablative fractional laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2017;19:378–82. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1342040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guimarães PA, Haddad A, Neto MS, Lage FC, Ferreira LM. Striae distensae after breast augmentation: Treatment using the nonablative fractionated 1550-nm erbium glass laser. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:636–42. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31827c7010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alves RO, Boin MF, Crocco EI. Striae after topical corticosteroid: Treatment with nonablative fractional laser 1540nm. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015;17:143–7. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2014.1003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stotland M, Chapas AM, Brightman L, Sukal S, Hale E, Karen J, et al. The safety and efficacy of fractional photothermolysis for the correction of striae distensae. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:857–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malekzad F, Shakoei S, Ayatollahi A, Hejazi S. The safety and efficacy of the 1540nm non-ablative fractional XD probe of star lux 500 device in the treatment of striae alba: Before-after study. J Lasers Med Sci. 2014;5:194–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang K, Ross N, Osley K, Sahu J, Saedi N. Evaluation of a 1540-nm and a 1410-nm nonablative fractionated laser for the treatment of striae. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:225–31. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tretti Clementoni M, Lavagno R. A novel 1565 nm non-ablative fractional device for stretch marks: A preliminary report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015;17:148–55. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1007061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDaniel DH, Ash K, Zukowski M. Treatment of stretch marks with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:332–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nehal KS, Lichtenstein DA, Kamino H, Levine VJ, Ashinoff R, Perelman RO. Treatment of mature striae with the pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:41–4. doi: 10.1080/14628839950517084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jimeénez GP, Flores F, Berman B, Gunja-Smith Z. Treatment of striae rubra and striae alba with the 585-nm pulsed-dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:362–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shokeir H, El Bedewi A, Sayed S, El Khalafawy G. Efficacy of pulsed dye laser versus intense pulsed light in the treatment of striae distensae. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:632–40. doi: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Passeron T, Ortonne JP. The 308 nm excimer laser in dermatology. Press Med. 2005;34:301–9. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(05)83912-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg DJ, Marmur ES, Hussain M. 308 nm excimer laser treatment of mature hypopigmented striae. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:596–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg DJ, Marmur ES, Schmults C, Hussain M, Phelps R. Histologic and ultrastructural analysis of ultraviolet B laser and light source treatment of leukoderma in striae distensae. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:385–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostovari N, Saadat N, Nasiri S, Moravvej H, Toossi P. The 308-nm excimer laser in the darkening of the white lines of striae alba. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:229–31. doi: 10.3109/09546631003592044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Bernstein LJ, Friedman PM, Geronemus RG. The safety and efficacy of the 308-nm excimer laser for pigment correction of hypopigmented scars and striae alba. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:955–60. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.8.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman A, Rossato F, Prati C. Stretch marks: Treatment using the 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:686–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsaie ML, Hussein MS, Tawfik AA, Emam HM, Badawi MA, Fawzy MM, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of two fluences using long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of striae distensae. Histological and morphometric evaluation. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1845–53. doi: 10.1007/s10103-016-2060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Ramly AZ, El-Hanafy GM, El Maadawi ZM, Bastawy NH. Histological and quantitative morphometric evaluation of striae distensae treated by long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. 2015;12:120–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tay YK, Kwok C, Tan E. Non-ablative 1,450-nm diode laser treatment of striae distensae. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:196–9. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Longo L, Postiglione MG, Marangoni O, Melato M. Two-year follow-up results of copper bromide laser treatment of striae. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2003;21:157–60. doi: 10.1089/104454703321895617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sardana K. Lasers for treating striae: An emergent need for better evidence. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:392–4. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.140288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaplan H, Gat A. Clinical and histopathological results following Tri Pollar™ radio frequency skin treatments. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11:78–84. doi: 10.1080/14764170902846227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suh DH, Chang KY, Son HC, Ryu JH, Lee SJ, Song KY. Radiofrequency and 585-nm pulsed dye laser treatment of striae distensae: A report of 37 Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montesi G, Calvieri S, Balzani A, Gold MH. Bipolar radiofrequency in the treatment of dermatologic imperfections: Clinic pathological and immunohistochemical aspects. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:890–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manuskiatti W, Boonthaweeyuwat E, Varothai S. Treatment of striae distensae with a TriPollar radiofrequency device: A pilot study. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20:359–64. doi: 10.3109/09546630903085278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim IS, Park KY, Kim BJ, Kim MN, Kim CW, Kim SE. Efficacy of intradermal radiofrequency combined with autologous platelet-rich plasma in striae distensae: A pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1253–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dover JS, Rothaus K, Gold MH. Evaluation of safety and patient subjective efficacy of using radiofrequency and pulsed magnetic fields for the treatment of striae (stretch marks) J Clin Aesthet Dermato. 2014;7:30–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harmelin Y, Boineau D, Cardot-Leccia N, Fontas E, Bahadoran P, Becker AL, et al. Fractionated bipolar radiofrequency and bipolar radiofrequency potentiated by infrared light for treating striae: A prospective randomized, comparative trial with objective evaluation. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:245–53. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Issa MC, de Britto Pereira Kassuga LE, Chevrand NS, do Nascimento Barbosa L, Luiz RR, Pantaleão L, Vilar EG, et al. Transepidermal retinoic acid delivery using ablative fractional radiofrequency associated with acoustic pressure ultrasound for stretch marks treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45:81–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pongsrihadulchai N, Chalermchai T, Ophaswongse S, Pongsawat S, Udompataikul M. An efficacy and safety of nano fractional radiofrequency for the treatment of striae alba. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:84–90. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mishra V, Miller L, Alsaad SM, Ross EV. The use of a fractional ablative micro-plasma radiofrequency device in treatment of striae. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suh DH, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Shin MK, Song KY. Treatment of striae distensae combined enhanced penetration platelet-rich plasma and ultrasound after plasma fractional radiofrequency. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14:272–6. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.738916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hodeib AA, Hassan GF, Ragab MN, Hasby EA. Clinical and immunohistochemical comparative study of the efficacy of carboxytherapy vs platelet-rich plasma in treatment of stretch marks. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1008–15. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gamil HD, Ibrahim SA, Ebrahim HM, Albalat W. Platelet-rich plasma versus tretinoin in treatment of striae distensae: A comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:697–704. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alster TS, Graham PM. Microneedling: A review and practical guide. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:397–404. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aust MC, Knobloch K, Vogt PM. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy as a novel therapeutic option for striae distensae. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:219e–20e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea93da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park KY, Kim HK, Kim SE, Kim BJ, Kim MN. Treatment of striae distensae using needling therapy: A pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1823–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khater MH, Khattab FM, Abdelhaleem MR. Treatment of striae distensae with needling therapy versus CO2 fractional laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:75–9. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1063665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nassar A, Ghomey S, El Gohary Y, El-Desoky F. Treatment of striae distensae with needling therapy versus microdermabrasion with sonophoresis. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:330–4. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2016.1175633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Karimipour DJ, Kang S, Johnson TM, Orringer JS, Hamilton T, Hammerberg C, et al. Microdermabrasion: A molecular analysis following a single treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdel-Latif AM, Elbendary AS. Treatment of striae distensae with microdermabrasion: A clinical and molecular study. JEWDS. 2008;5:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mahuzier F. Microdermabrasion of stretch marks. In: Mahuzeier F, editor. Microdermabrasion or Parisian Peel in Practice. Marseille: 1999. pp. 25–65. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hexsel D, Soirefmann M, Porto MD, Schilling-Souza J, Siega C, Dal’Forno T. Superficial dermabrasion versus topical tretinoin on early striae distensae: A randomized, pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:537–44. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hernandez-Perez E, Charrier EC, Valencia-Ibiett E. Intense pulsed light in the treatment of striae distensae. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1124–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bedewi AE, Khalafawy GE. The use of synchrotron infra-red microspectroscopy to demonstrate the effect of intense pulsed light on dermal fibroblasts. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:305–9. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.769271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Al-Dhalimi MA, Abo Nasyria AA. A comparative study of the effectiveness of intense pulsed light wavelengths (650 nm vs 590 nm) in the treatment of striae distensae. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:120–5. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.El Taieb MA, Ibrahim AK. Fractional CO2 laser versus intense pulsed light in treating striae distensae. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:174–80. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.177774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El-Khalafawy GM. Comparative study between Intense Pulsed Light IPL and Pulsed Dye Laser in the treatment of striae distensae. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:632–4. doi: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sadick N, Magro C, Hoenig A. Prospective clinical and histologicalstudy to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a targeted highintensity narrow band UVB/UVA1 therapy for striae alba. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:79–83. doi: 10.1080/14764170701313767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trelles MA, Levy JL, Ghersetich I. Effects achieved on stretch marks by a non-fractional broadband infrared light system treatment. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:523–30. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ash K, Lord J, Zukowski M, McDaniel DH. Comparison of topical therapy for striae alba (20% glycolic acid/0.05% tretinoin versus 20% glycolic acid/10% L-ascorbic acid) Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:849–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deprez P. Easy peel for the treatment of stretch marks. International Journal of Cosmetic Surgery and Aesthetic Dermatology. 2000;2:201–4. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bitencourt S, Lunardelli A, Amaral RH, Dias HB, Boschi ES, Oliveira JR. Safety and patient subjective efficacy of using galvanopuncture for the treatment of striae distensae. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:393–8. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ferreira AC, Guida AC, Piccini AA, Parisi JR, Sousa LD. Galvano-puncture and dermabrasion for striae distensae: A randomized controlled trial? J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018:1–5. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2018.1444777. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2018.1444777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sinyakova OV, Drogovoz SM, Kononenko AV, Ivantsyk LB. Applied use of carbon dioxide in cosmetology. 2016;81 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Podgórna K, Kołodziejczak A, Rotsztejn H. Cutometric assessment of elasticity of skin with striae distensae following carboxytherapy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1170–4. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]