Abstract

Objectives

Globalisation has increased the opportunities for health professionals working in developed countries to provide clinical and educational support in developing countries. However, how these experiences contribute to the leadership competency of health professionals is unclear; therefore, this study explored this with the objective of analysing the process of developing individual leadership competency.

Design

This is a qualitative descriptive study. Qualitative descriptive study is widely used in healthcare research, particularly to describe the nature of various healthcare phenomena. Qualitative descriptive data were collected in face-to-face, semistructured interviews.

Setting

The authors interviewed Japanese health professionals who participated in an international medical cooperation project as part of a multinational medical team between July 2017 and March 2018, and analysed and interpreted the data using a social constructivism paradigm.

Participants

The authors interviewed 20 research participants, including 5 nurses, 5 dentists and 10 physicians with an average of 15.3 years of clinical experience.

Results

The interviews identified 58 emergent themes related to their leadership competency, 23 of which affected the actual medical care in their own institutions. The authors categorised the 58 emergent themes into seven competency areas: leadership concepts, teambuilding, direction setting, communication, business skills, working with others and self-development. The authors identified the relationships among each competency and identified differences between professions: nurses particularly reflected on their empathic attitudes towards patient after global clinical health experience; dentists tended to reflect on their business skills; physicians tended to reflect on their leadership concepts and teambuilding.

Conclusions

This study clarified the leadership competency gained through short-term global clinical health experience and the process of individual leadership competency development. The findings provide expected learning competency for those considering medical practice in developing or other countries in the future.

Keywords: qualitative research, leadership, global health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study clarified leadership competency gained through the global clinical health experience and the process of individual leadership competency development because this is the first time the relationship between the two was explored.

Researchers focused on the members of a multinational team of physicians, dentists and nurses because this 1 month experience of working closely together gave extensive opportunity for data collection and observation.

A limitation of this study is that we had interviewed only Japanese health professionals who have participated in short-term global clinical health experiences.

Further investigation of how health professionals adopted their leadership competency on their return to their own worksites would be required.

Introduction

With globalisation, the opportunities for health professionals1 (box 1) working in developed countries to conduct medical practice and provide educational support in developing countries are multiplying.2 Many universities offer students and advanced medical personnel opportunities to undergo short-term medical training in developing countries.3 Through global clinical health experiences4 (box 1), health professionals not only become aware of what they did not notice previously, but they can also improve their interactions with others.5 Both quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted on health professionals and students who provide healthcare services in developing countries to determine the type of learning process that occurs in these health professionals.6–8 Various research has been conducted on host countries that have accepted medical support9 10; however, how these experiences are utilised by health professionals in their own fields is unclear. Moreover, to our knowledge, no study has assessed the differences in each profession. This study aimed to explore how the health professionals’ short-term global clinical health experiences were translated into clinical practice from the perspective of experiential learning.

Box 1. Glossary.

Health professional

A person who maintains health in humans through the application of the principles and procedures of evidence-based medicine and caring. It includes medical doctors, nursing professionals, midwife professionals, dentists and pharmacists.1

Global clinical health experience

Experience of clinical practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide and emphasising vulnerable populations in underserved settings.4

Leadership competency

A group of competencies linked to the concept of leadership where leadership is not restricted to people who hold designated leadership roles and where there is a shared sense of responsibility for the success of the organisation and its services.28

The experiential learning theory was established by a multidisciplinary integration of knowledge through many academic disciplines.11 Experience is the foundation of learning, and learners actively build their own experiences. Learning and experience are closely linked and cannot be separated.12 ‘Learning’ refers to changes in knowledge and skills, and ‘experience’ refers to mutual interaction with the outside world that promotes changes in knowledge and skills.13 The concept of ‘experiential learning’ refers to the ways in which a variety of experiences are affected by sociocultural norms and the subjectivity of agents. This idea can be differentiated into ‘external experiences’, in which events are the subject of learning, and ‘internal experiences’, in which past experiences accumulated in the memory become the conditions for learning.14 The model of experiential learning as presented by Kolb is the most influential of the theories that attempt to explain individual managers’ experiential learning and has been applied in a variety of fields, including education, psychology, medicine, nursing and general management.15 16 However, Kolb’s experiential learning model does have its limitations, particularly in connection with the introspection of experiences, and it has also been criticised for not considering social factors, unconscious learning and higher meta-learning processes.17 18 In response to these criticisms, other researchers have proposed models that relate to meta-learning in which experience itself can be transformed through introspection.19

Experiences that are related to creating change and transcending boundaries can be seen as developmental challenges, and it is evident that the experience of working beyond boundaries is connected to the development of human resources.20 21 It is further clear that culture shock can contribute to the development of leadership.22 Fulfilling innovative duties in the workplace could allow managers to learn, and challenging situations could allow individuals to challenge traditional ways of thinking and behaving, thereby creating the motivation to bridge the gap between an individual’s current capabilities and those they desire. These experiences of working beyond boundaries, also known as developmental challenges, lead to the acquisition of abilities.23 By transcending boundaries and overcoming barriers to teambuilding, individuals can learn valuable lessons. With the creation of teams that cross-boundaries and by being part of such teams, members can increase their knowledge of other disciplines, expand networks with colleagues in other organisations and enhance leadership competencies.24 Leadership is an important required competency for health professionals to demonstrate practical skills and effective team management in complex organisational and human relationships in various environments.25 High-quality healthcare relies on developing healthcare professionals’ leadership, thereby optimising health system performance.26 The Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) review showed the evidence used in the leadership development of medical faculty members,27 demonstrating that the use of experiential learning and reflective practice contribute to positive outcomes that promote leadership. However, relationships between cross-boundary experiences in the health professionals and their leadership development have not been identified.

This study examined the contribution of a short-term global clinical health experience in various Asian-Pacific countries to the leadership competency28 (box 1) of members of a multinational team of physicians, dentists and nurses. We conducted a qualitative descriptive study with the participants’ consent. The objective was to analyse the process of developing individual leadership competency from the perspective of experiential learning. The potential to inculcate the competency of leadership exists in all individuals, regardless of their current job designations. In addition, we explored their relationship with daily clinical practice to clarify the differences between various types of jobs. The study findings will help in guiding mentors who conduct global clinical health training for undergraduate students and residents, and will also provide useful information for developing leadership competency in health professionals.

Method

We followed the standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) recommendations.29 Full details of the SRQR can be found in the research checklist to this paper. Qualitative descriptive study30 is one of the qualitative study methods that are widely used in healthcare research, particularly to describe the nature of various healthcare phenomena. We conducted a qualitative descriptive study, and interviewed 20 research participants. The thematic analysis method31 used in this study involved generative coding and theorisation.

Setting

Following the Sumatra earthquake and Indian Ocean tsunami,32 the US army organised the ‘Pacific Partnership’, a multilateral project that aimed to improve humanitarian assistance and disaster relief capacity. Under this project, a US navy boat conducts annual visits to several countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Through cooperation with government agencies, the military and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) of the participating countries, the Pacific Partnership aims to improve mutual understanding and strengthen cooperation among related countries by conducting medical activities, facility repair and cultural exchange programmes. We adopted this project as a short-term global clinical health experience in our study to explore how the experiences are translated into clinical practice, and our first author actually participated in the 2016 and 2017 Pacific Partnership as an NGO member and developed relationships with research participants. Japanese health professionals provided medical support in Palau (Pacific Partnership 2016) and Vietnam (Pacific Partnership 2017) for several weeks. The participants lived and worked with the visiting health professionals from the USA, the UK and Australia on military transport ships and conducted outdoor medical practice, ambulatory care support and educational activities for each job category. All participants shared both clinical and administrative duties because of the location and working conditions, which varied from day to day.

Participants

All 50 health professionals involved in this project were invited to participate. Twenty people volunteered: 5 nurses, 5 dentists and 10 physicians who had participated in the 2016 or 2017 Pacific Partnership and who had provided informed consent for study participation. The mean age of the research participants was 40.0 years (range, 29–57 years), and the mean duration of clinical experience was 15.3 years (range, 4–34 years). By focusing on a culturally homogenous group, we could achieve thematic saturation with this limited number (20) of participants. Table 1 provides their profiles.

Table 1.

Character of research participants

| No | Sex | PGY | Type of institution | Position | Participation |

| N1 | F | 15 | Community hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| N2 | M | 4 | Nursing home | Staff | 2017 |

| N3 | M | 20 | Self-defense forces | Staff | 2016 |

| N4 | F | 10 | University | Graduate student | 2016 |

| N5 | M | 17 | University | Lecturer | 2016 |

| D1 | M | 15 | Self-defense forces hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| D2 | M | 9 | Self-defense forces | Staff | 2016 |

| D3 | M | 34 | University hospital | Professor | 2016 |

| D4 | M | 23 | Community hospital | Manager | 2017 |

| D5 | M | 11 | Self-defense forces hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| P1 | M | 16 | Self-defense forces hospital | Manager | 2016 |

| P2 | M | 21 | University hospital assistant | Professor | 2017 |

| P3 | M | 13 | Community hospital | Staff | 2017 |

| P4 | F | 13 | Community hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| P5 | M | 14 | Community hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| P6 | M | 19 | University hospital | Lecturer | 2016, 2017 |

| P7 | M | 9 | Self-defense forces hospital | Staff | 2016 |

| P8 | M | 8 | University hospital | Staff | 2017 |

| P9 | M | 4 | University hospital | Resident | 2017 |

| P10 | M | 30 | University hospital | Assistant professor | 2017 |

D, dentist; N, nurse; P, physician (doctor); PGY, postgraduate year.

Patient and public involvment

Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Data collection

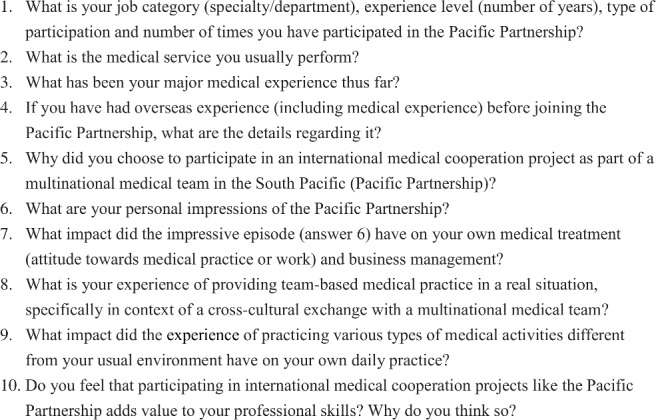

In this qualitative descriptive study, we conducted face-to-face, semistructured interviews using an audio recorder. Each interview lasted 30–90 min. The interviews took place at the participant’s place of clinical practice between July 2017 and March 2018. To ensure a safe environment that would elicit the interviewees’ straightforward beliefs, only the participant and the interviewer were present in these interviews. An interview guide (see figure 1) was used to clarify how the participants viewed their experiences and how those experiences influenced their leadership competency. The study authors agreed that the interview guide suited our research purpose and that the contents of the interview guide did not change over time. On the other hand, each of the interviews were flexible, and the participants were allowed to take the discussion in any direction. As a participant in the Pacific Partnership, the first author worked alongside the 20 participants and observed them in situ. The recorded audio data of the interviews were transcribed verbatim by the authors immediately after each interview.

Figure 1.

Interview guide.

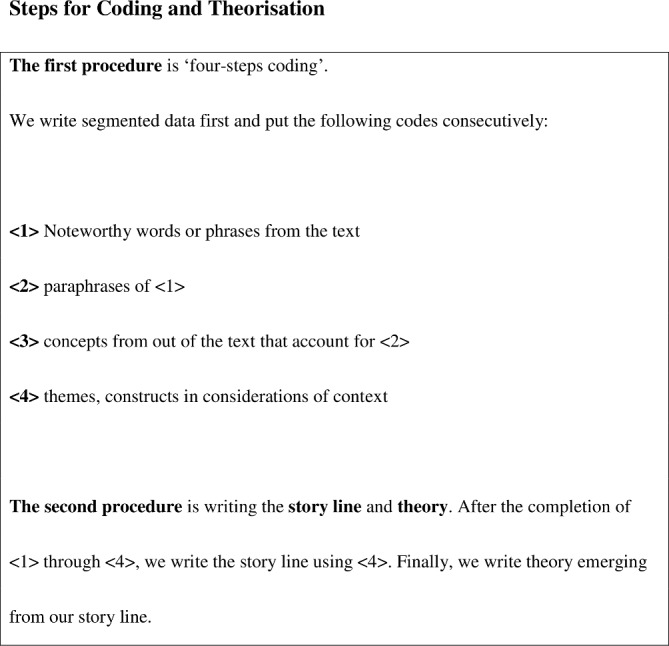

Data analysis

We have analysed the data manually with multiple names using the steps for coding and theorisation method and performed a theoretical evaluation from the perspective of a social constructivism paradigm.33 34 The method of coding and theorisation for data analysis comprised two major steps: first, the text data were divided into small units and were classified as meanings or ideas, and second, each of these small units was labelled with an interpretive description (see figure 2). These processes were conducted on each interview transcript. For the targeted number of research participants, we conducted interviews for multiple occupations until theoretical saturation was obtained. After data collection and individual manual analyses, we agreed that we had achieved theoretical saturation, with no new themes emerged in the data set, and we achieved a complete understanding of the identified concepts. Member checking was conducted twice by the research participants after the interviews and analyses.

Figure 2.

Processes of data analysis.

Results

Through the interviews, we identified 58 emergent themes to the competency of leadership (see table 2). We divided them into ‘during’ and ‘after’ the actual global clinical health experience. Among them, 23 of the themes that affected the actual medical care in their own institutions were recognised. We categorised the 58 themes into the seven competency areas: leadership concepts, teambuilding, direction setting, communication, business skills, working with others and self-development. We focused on the leadership aspects of certain specific factors related to clinical practice. For instance, we considered the ‘establishment of a trust relationship’ to be a leadership competency component of ‘working with others’ but did not regard ‘performing assignments’ as an element contributing to leadership competency.

Table 2.

Emergent themes

| During participation | After participation |

| Leadership concept | |

| Fulfilment of duties Recognition of individual leadership Overseeing medical treatment as a specialist Leveraging the individual leadership concept Promoting awareness of potential leadership Constructing the leadership concept A place to guide change Self-assessment of leadership Paradigm shift on leadership |

Establishment of individual leadership style Establishment of servant leadership Strengthening follower-friendly servant leadership Contribution of leadership concept to daily practice Delegation of authority |

| Teambuilding | |

| Making policy decision as a practical community meta-recognition of past work experience Promoting understanding of diversity Strengthening the attitude of shared leadership Practicing conflict management |

Strengthening the awareness of teambuilding |

| Direction setting | |

| Taking action based on context dependence Making the medical care environment relative Recognition of local context Development of cultural competency Awareness of target setting and backwards development Making policy decisions Paying attention to team direction and process Understanding environment and decision-making |

Recognition of individual organisational position Understanding the environment Reviewing target setting Strengthening viewpoint of leader development |

| Communication | |

| Nurturing global thinking and communication skills Encouraging reflection of communication skills |

Strengthening the awareness of communication |

| Business skills | |

| Strengthening business and communication skills Simulation training for disasters Understanding and reflection of business skills Paying attention to the power relation |

Applying simulation tools Awareness of business skills Developing other support activities Reflecting individual examination style |

| Working with others | |

| Seeking out new leadership concepts Establishment of a trust relationship |

Empowering other health professions Developing others and career support Reflecting individual educational policy Strengthening cooperation among staff members |

| Self-development | |

| Developing awareness of a sense of belonging Strengthening adaptability and self-management Paradigm shift as a professional Seeking self-development opportunities Recognising the necessity of total management |

Reconsidering empathic attitude towards patient Establishing self-management Motivation for career advancement and self-development Lifelong learning |

Leadership concepts

The experience of participating in the global clinical health cooperation project became a trigger that often led to the establishment of a leadership style. Although we can see some differences in each health professional and their own experiences, many health professionals saw the change in location as an impetus for change. To quote one participant: ‘There are many developing nations, and I feel that Japan is quite advanced in terms of its medical standards. Instead of simply providing assistance with medical care, I think it is important to educate local medical practitioners that are providing such care. Furthermore, education is obviously necessary, but I also felt that the perspective of training educators was necessary’ (Participant D3).

Health professionals self-evaluated their leadership in highly uncertain situations during their actual global clinical health experience. Some noted that after the experience, they continued to strengthen the leadership concept of delegation of authority that had been gained through their short-term global clinical health experience: ‘I appointed a person-in-charge in each department, asked them to organize the department, and then supervised them during the subsequent activity.…Although I had not thought about team medical care before participating in the program, I allocated more responsibilities to staff members in my hospital after seeing the professionalism of the participants’ (P1).

Teambuilding

The project helped health professionals recognise that a cooperative workplace led to more successful policy decisions and a better understanding of diversity and their colleagues’ environment, and they meta-recognised past work experience of their own: ‘The biggest achievement from global clinical health experience is that one’s perspective as a medical professional broadens by participating.…Although we were different in age and positions, my team members were great people. Having peers with whom I wanted to work with together again was the biggest reward from this program’ (D4).

The participants strengthened their awareness of teambuilding and shared leadership, which in turn led to interprofessional education: ‘Through my experience abroad, I was able to experience that collaboration between different professions is important in any environment. It can serve as an educational tool for the future because even after participants come back to Japan, it will lead them to strengthen the collaboration between different professions on-site’ (N5).

Direction setting

The experience of the global clinical health cooperation project urged the participants to be more conscious of goal setting and policy decision-making as an organisation. They developed cultural competency: ‘The significance of this program is that participants can learn about how things are done in other countries because of the diversity of members within the program. It also becomes a learning experience on the diversity of management’ (D2).

The experience contributed to a better understanding of the participants’ own work environments as well as how the environment and the team process strengthened the awareness of target setting and backward development. In addition, they strengthened their viewpoint of leader development through acquiring intersubjectivity: ‘The place where this program’s activities took place had no educational environment even if people wanted to learn about performing medical practice. Therefore, we are preparing to establish a structure within our facility in which we can accept foreign students to study. I would like to increase both the quality and quantity of local health professionals’ (D4).

Communication

Not only during but also after participating in the global health cooperation project, the participants increased their emphasis on communication at their work site, recognising the project as a place to nurture global thinking and communication skills. Strengthening their awareness of communication led to education: ‘While I felt that when I go to a new place…. it is necessary to first properly talk with one another when a relationship of trust has not yet been established, I also learned that communication in my daily medical practice settings can take place because there is an existing relationship of trust’ (N4).

Business skills

Through unexpected situations and conflict management, the participants were particularly influenced with respect to their consciousness of business skills in the field. They also recognised their own individual work style: ‘I did not know what to do because there was not even an option, and surgery and medicine would obviously not improve the situation.…By providing medical treatment in an environment that is different from my usual one, I felt that I had been practicing medical care by relying too much on tools’ (P7).

The participants also reflected on their own business skills, and as a result reinforced these skills and applied them to simulation tools: ‘I thought that it is important to take necessary items with us and have a logistic system in place to manage them when a disaster actually occurs…I came to be more aware of management and collaboration after the medical cooperation project’ (N3).

Working with others

Through the multilateral project that aimed to improve humanitarian assistance and disaster relief capacity, the health professionals established a relationship of trust in the field and made a more conscious effort to empower other health professionals. Furthermore, back in their workplace, the participants leveraged their experience into developing others and career support, and strengthened credit accumulation and cooperation among their staff members: ‘Both the students and my colleagues became interested in this program through my activity report. I want to provide as many people as possible with the opportunities that I was given’ (N2). ‘I had the opportunity to contact people from other departments and make adjustments before the program took place, helping me acquire the habit of trying to understand the other person’s organizations’ (D2).

Self-development

Through the global clinical health experience, some participants experienced a paradigm shift that became a trigger for career advancement and self-development: ‘Although there were differences depending on the environment, I felt that I had to hone my regular skills so that I could also give instructions after seeing the accurate medical techniques of the local physicians’ (P2).

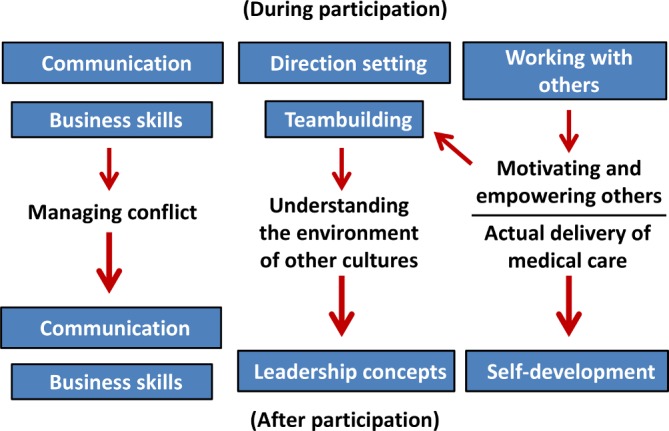

Relationships between themes

We identified several types of relationships between the themes described above (see figure 3). Experience in managing conflict during the global clinical health experience led the health professionals to reflect on their communication and business skills: ‘I could see that people abroad think in a completely different manner even if I didn’t interact with them on a regular basis.…I made all the schedules to indicate who would be taking the day off. It was difficult to coordinate because there was a language barrier and there were complaints that people weren’t getting many days off’ (D1).

Figure 3.

Relationships between themes.

Additionally, the global clinical health experience encouraged participants to motivate and empower others and encouraged ‘teambuilding’: ‘The biggest achievement that one can get by forming a team with people they just met is the ability to communicate effectively. This experience can be useful even in a different environment’ (D3).

The development of individual leadership competency associated with leading a medical care team was related to ‘understanding the environment of other cultures’ and teambuilding. One participant stated this: ‘We did actually provide outdoor medical care as if it was an actual field hospital. I keenly felt the difficulties of practicing medical care by having to start by preparing the tools. I learned how difficult it is to work in an environment with hygiene standards that are completely different from those of Japan’ (P4).

Finally, the concepts of ‘motivating and empowering others’ and ‘lifelong learning’ became associated with the actual delivery of medical care: ‘Coming into contact with various health professionals in a foreign country will be a good experience to have. I hope that the participants’ perspectives will broaden through their interactions. On the contrary, engaging only in one’s regular medical care environment will limit their perspectives. I want to share what I learned with my colleagues’ (P6).

Differences in the professions

Some differences in each profession were identified through the data analysis.

Nurses

Nurses particularly improved their empathic attitudes towards colleagues and patients as a result of the global clinical health experience. Consequently, through perspective gained from work in the field, they established servant leadership with the mentality of understanding others through relationships of trust, stating: ‘A relationship in which each person can see the other person’s face is extremely important…After participating in the program, I am more conscious of listening to my peers while on-site. With my staff members in particular, I check what they are having troubles with and provide everything I can for their growth’ (N1).

Dentists

Dentists tended to reflect on their business skills after the global clinical health experience. The experience affected their consciousness of their business skills at their own work site and their application of these skills to the leadership concept: ‘Instead of relying on the limited resources during medical treatments, I became able to think about how to replace the resources with something else and share this finding with colleagues’ (D2). Another dentist stated: ‘The attitude to provide the best medical care in environments with limited resources like where the activity took place is important. A similar mindset is also needed when one transfers from a hospital with enhanced facilities, like a university hospital, to a regional hospital with limited resources’ (D3).

Physicians

After participating in the project with the multinational medical team, physicians recognised the importance of teambuilding at their own work site. They recognised that they became conscious of strengthening their leadership and goal setting at their own organisations: ‘On-site, I became able to make adjustments well by transferring some of the authorities to the staff members and having them practice and make corrections instead of taking on all the responsibilities as a department director.…I feel that finding what each person can do in their profession and allocating duties accordingly can draw out their abilities’ (P1). Another physician stated: ‘Seeing case examples of diseases that cannot be treated on-site made me re-acknowledge just how fortunate the Japanese medical environment is’ (P8).

Discussions

We identified seven leadership competencies strengthened by the short-term global clinical health experience. In addition, we clarified relationships among each leadership competency gained through the experience and the different types of leadership competency among various types of jobs. Previous studies have shown the potential benefits for global clinical health participants in terms of increased awareness of global health issues, gaining new medical information, capacity building for clinical problem solving and an improved sense of professional satisfaction.5 8 Our results contribute to the literature with additional findings regarding the enhancement of leadership competency.

We considered several factors contributing to how health professionals can gain leadership competency through the global experience and then add it to their clinical practice. Collaboration among the multinational team of health professionals certainly led to increased leadership competency. While leadership and collaboration are highly valued and potentially conflicting competencies in clinical practice,26 by managing conflict and difficult cases in the global clinical health experience, participants collaborated with each other, enhancing their leadership competency. From the perspective of experiential learning, the global clinical health experience was an external experience by health professionals that contributed to their daily clinical practice as an internal experience.14 Second, understanding the environment of other cultures forms the basis for gaining leadership competency as shown in the relationships among the themes. Experiencing cultural differences becomes conscious behaviour through contact with new situations and cultures in which unconscious and implicit cultural behaviour and sensibilities are required.35 The global clinical health experience offered the opportunity for participants to learn about themselves and their own leadership,36 and they continued these leadership competencies in their own institutions on their return. In this process, we observed that a meta-learning process occurred in each health professional as a result of their global clinical health experience, and that this process led to the enhancement of their leadership competency in each context.

Our results clearly demonstrate that the leadership concept is perceived differently by individuals from different professions. Nurses particularly strengthened their empathic attitudes towards patients and colleagues, and they strengthened their leadership by establishing a mentality of understanding and relationships of trust in their workplace. Nurses tend to be well trained in an empathetic attitude in their careers,37 which supports our result. Meanwhile, dentists particularly focused on their business skills. In the clinical environment in many countries, treatment must be done with limited equipment, and dentists often solved these problems while leveraging their own business skills. As ethical stewardship of healthcare resources are important for health professionals,38 participant dentists became aware of the ethics of waste avoidance in their daily practice overseas. Consequently, they improved their business skills and brought those improved skills to their own jobs after their participation. Finally, physicians recognised the importance of teambuilding and after the global clinical health experience strengthened their leadership and goal setting in their own organisation. Physicians have professional obligations and a responsibility to develop public roles.39 The global clinical health experience presented physicians with many opportunities to coordinate and make decisions with other occupations, thereby strengthening their competencies related to leadership and teambuilding.

Our findings show important parallels with earlier studies, including the BEME review that showed that leadership competencies are gained through faculty development programmes.27 These studies examined the prevalence and characteristics of faculty leadership development programmes at academic health centres and found that conflict management or interpersonal effectiveness are emphasised but business skills and lifelong learning are part of faculty development.40 In this study, we pointed out various types of leadership competency gained by health professionals through a global clinical health experience, which supports the idea that the use of experiential learning and reflective practice contribute to positive outcomes in promoting leadership. Furthermore, we identified a link between cross-boundary experiences and the participants’ leadership development. It would be useful to elucidate the differences in the learning process between faculty development and experiential learning and examine the concept of tacit knowledge that is difficult to transfer to another person.41 In general, faculty development aims to ensure that health professionals have the knowledge and skills for leadership development, while in experiential learning, health professionals learn leadership competency as tacit knowledge through the experience itself without formal instruction.

One limitation of this study is we had interviewed only Japanese health professionals who participated in the short-term global clinical health project. As there is no leadership that exerts a common effect beyond culture in a previous study,42 we should investigate the process of developing individual leadership competency in other countries. Another limitation of this study is we focused on health professionals who mainly have their own specialty (mean duration of clinical experience is 15.3 years). Leadership is one of the important competencies required to demonstrate practical skills in effective team management in complex organisations at all levels.25 Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to investigate the leadership development process through global clinical health experiences in the younger generation, including residents and undergraduate students. Finally, the actual interpersonal interaction in each health professional’s institution is not made clear in this study. Although we identified the contribution of the short-term global clinical health experience to the leadership competency as an outcome, the organisations where the participants work are complex and dynamic social environments.43 44 Therefore, further investigation of how health professionals adopted their leadership competency on their return to their own environment would be required. As stated above, leadership competency development in other cultures would have to be studied to investigate the transferability of these results. Leadership competencies would be affected by cultural values such as individualism—collectivism and social norms including cultural tightness—looseness.45 It is also difficult to make generalised statements without researching the leadership development process in other fields such as volunteering, construction or religious missions. Based on emergent themes, we can predict that other fields or cultures would yield some similar findings in parameters such as communication, working with others and teambuilding (table 2).

Conclusion

This study clarified the leadership competency gained through a short-term global clinical health experience and the process of individual leadership competency development. The competencies gained by nurses, dentists and physicians were different. The findings provide expected learning competency for those considering clinical practice in developing or other countries in the future. The study findings may also help in guiding mentors who conduct global clinical health training for health professionals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to say thank Linda Snell, MD, MHPE, FRCPC, MACP, McGill’s Centre for Medical Education, for her critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH was the principal investigator for this study, conducted the interviews and authored the paper. HO contributed to the design of this study. DS analysed and coded all data with MH. ME checked the results, advised edits and approved for public release. All authors have agreed with the final version of this paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo (IRB ID 11562).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are availavle.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Transforming and Scaling Up Health Professionals' Education and Training: World Health Organization Guidelines. 2013. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/transf_scaling_hpet/en/ (Accessed 5 Apr 2019). [PubMed]

- 2. Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, et al. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med 2007;82:226–30. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jeffrey J, Dumont RA, Kim GY, et al. Effects of international health electives on medical student learning and career choice: results of a systematic literature review. Fam Med 2011;43:21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009;373:1993–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greysen SR, Richards AK, Coupet S, et al. Global health experiences of U.S. Physicians: a mixed methods survey of clinician-researchers and health policy leaders. Global Health 2013;9:19 10.1186/1744-8603-9-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med 2000;32:566–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, et al. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med 2009;84:320–5. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nordhues HC, Bashir MU, Merry SP, et al. Graduate medical education competencies for international health electives: a qualitative study. Med Teach 2017;39:1128–37. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1361518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraeker C, Chandler C. "We learn from them, they learn from us": global health experiences and host perceptions of visiting health care professionals. Acad Med 2013;88:483–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182857b8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kung TH, Richardson ET, Mabud TS, et al. Host community perspectives on trainees participating in short-term experiences in global health. Med Educ 2016;50:1122–30. 10.1111/medu.13106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2005;4:193–212. 10.5465/amle.2005.17268566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. : Boud D, Cohen R, Walker D, Using Experience for Learning: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beard C, Wilson JP. The Power of Experiential Learning: A Handbook for Trainers and Educators. London: Kogan Page, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moon JA. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamazaki Y, Kayes DC. An experiential approach to cross-cultural learning: a review and integration of competencies for successful expatriate adaptation. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2004;3:362–79. 10.5465/amle.2004.15112543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kayes DC. Experiential learning and its critics: preserving the role of experience in management learning and education. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2002;1:137–49. 10.5465/amle.2002.8509336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vince R. Behind and Beyond Kolb’s Learning Cycle. Journal of Management Education 1998;22:304–19. 10.1177/105256299802200304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development : Armstrong SJ, Fukami C V, The Sage handbook of management learning. Education and development: Sage, 2009:42–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Derue DS, Wellman N. Developing leaders via experience: the role of developmental challenge, learning orientation, and feedback availability. J Appl Psychol 2009;94:859–75. 10.1037/a0015317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ohlott JP. Job assignment : McCauley CD, Moyley RS, Velsor E V, The Center for Creative Leadership: Handbook of Leadership Development. New York: Josey-Bass, 1998:130–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCall MW, Hollenbeck GP. Developing Global Executives: The Lessons of International Experience. Harvard Business School Press 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCauley CD, Ruderman MN, Ohlott PJ, et al. Assessing the developmental components of managerial jobs. J Appl Psychol 1994;79:544–60. 10.1037/0021-9010.79.4.544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edmondson AC. Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dine CJ, Kahn JM, Abella BS, et al. Key elements of clinical physician leadership at an academic medical center. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:31–6. 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00017.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McAlearney AS. Using leadership development programs to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:319–31. 10.1097/00115514-200809000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach 2012;34:483–503. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.680937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Medical leadership competency framework. 3rd edn, 2010. https://www.leadershipacademy.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/NHSLeadership-Leadership-Framework-Medical-Leadership-Competency-Framework-3rd-ed.pdf (Accessed 5 Apr 2019).

- 29. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health 2017;40:23–42. 10.1002/nur.21768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Srinivas H, Nakagawa Y. Environmental implications for disaster preparedness: lessons learnt from the Indian Ocean Tsunami. J Environ Manage 2008;89:4–13. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Otani T. “SCAT” A qualitative data analysis method by four-step coding: Easy startable and small scale data-applicable process of theorization. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development. Nagoya University 2007;54:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Otani T. SCAT: Steps for Coding and Theorization. Qualitative Data Analysis Method. 2015. http://www.educa.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~otani/scat/index-e.html#02 (Accessed 31 Jan 2019).

- 35. Dreier O. Personal trajectories of participation across contexts of social practice. Outline: Critical Social Studies 1999;1:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cole DC, Plugge EH, Jackson SF. Placements in global health masters' programmes: what is the student experience? J Public Health 2013;35:329–37. 10.1093/pubmed/fds086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Upper Saddle River: Prince-Hall, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brody H. From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1949–51. 10.1056/NEJMp1203365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens--public roles and professional obligations. JAMA 2004;291:94–8. 10.1001/jama.291.1.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lucas R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, et al. Leadership development programs at academic health centers: results of a national survey. Acad Med 2018;93:229–36. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wagner RK, Sternberg RJ. Practical intelligence in real-world pursuits: The role of tacit knowledge. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985;49:436–58. 10.1037/0022-3514.49.2.436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. House RJ, Hanges PJ, Javidan M, et al. Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies: Sage Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Doll WE, Trueit D. Complexity and the health care professions. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:841–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mennin S. Self-organisation, integration and curriculum in the complex world of medical education. Med Educ 2010;44:20–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aktas M, Gelfand MJ, Hanges PJ. Cultural Tightness–Looseness and Perceptions of Effective Leadership. J Cross Cult Psychol 2016;47:294–309. 10.1177/0022022115606802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.