ABSTRACT

Since NH4+ is one of the most important limiting nitrogen sources for plant growth, ammonium uptake and transport system has particular attention. In plant cells, ammonium transporters (AMTs) are responsible for ammonium uptake and transport. In previous studies, we identified a PutAMT1;1 gene from Puccinellia tenuiflora, which is a monocotyledonous halophyte species that thrives in alkaline soil. The overexpression of PutAMT1;1 in Arabidopsis thaliana enhanced plant growth and increased plant susceptibility to toxic methylammonium (MeA). This transporter might be useful for improving the root to shoot mobilization of MeA (or NH4+). Interestingly, in our other studies, it can be assumed that urease acts on urea to produce NH4+, which may exacerbate salt stress. Overexpression of PutAMT1;1 promoted early root growth after seed germination in transgenic Arabidopsis under salt stress condition. These findings suggest that ammonium transport alleviates ammonia toxicity caused by salt stress. Subcellular localization revealed that PutAMT1;1 is mainly localized in the plasma membrane and the nuclear periphery and endomembrane system of yeast and plant cells. Here, we discuss these recent findings and speculate on the regular dynamic localization of PutAMT1;1 throughout the cell cycle, which may be related to intracellular activity.

KEYWORDS: Puccinellia tenuifolra (P. tenuifolra), Ammonium transporter (AMT), Green fluorencence protein (GFP), Arabidopsis thaliana

Nitrogen is one of the essential macronutrients for plant growth and one of the main factors to be considered affecting productivity. Ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) are two primary inorganic nitrogen sources absorbed by roots of higher plant in most natural and agricultural environment.1,2 Since ammonium assimilation requires less energy than that of nitrate, ammonium is the preferential form of nitrogen uptake when plants are subjected to nitrogen deficiency.3,4 Although ammonium uptake is more efficient, excessive ammonium uptake into the plant can be toxic;5–9 therefore, ammonium uptake system in plants has particular attention.10,11 However, there is relatively little discussion about the coupling relationship between ammonium ion transport and ammonia toxicity.

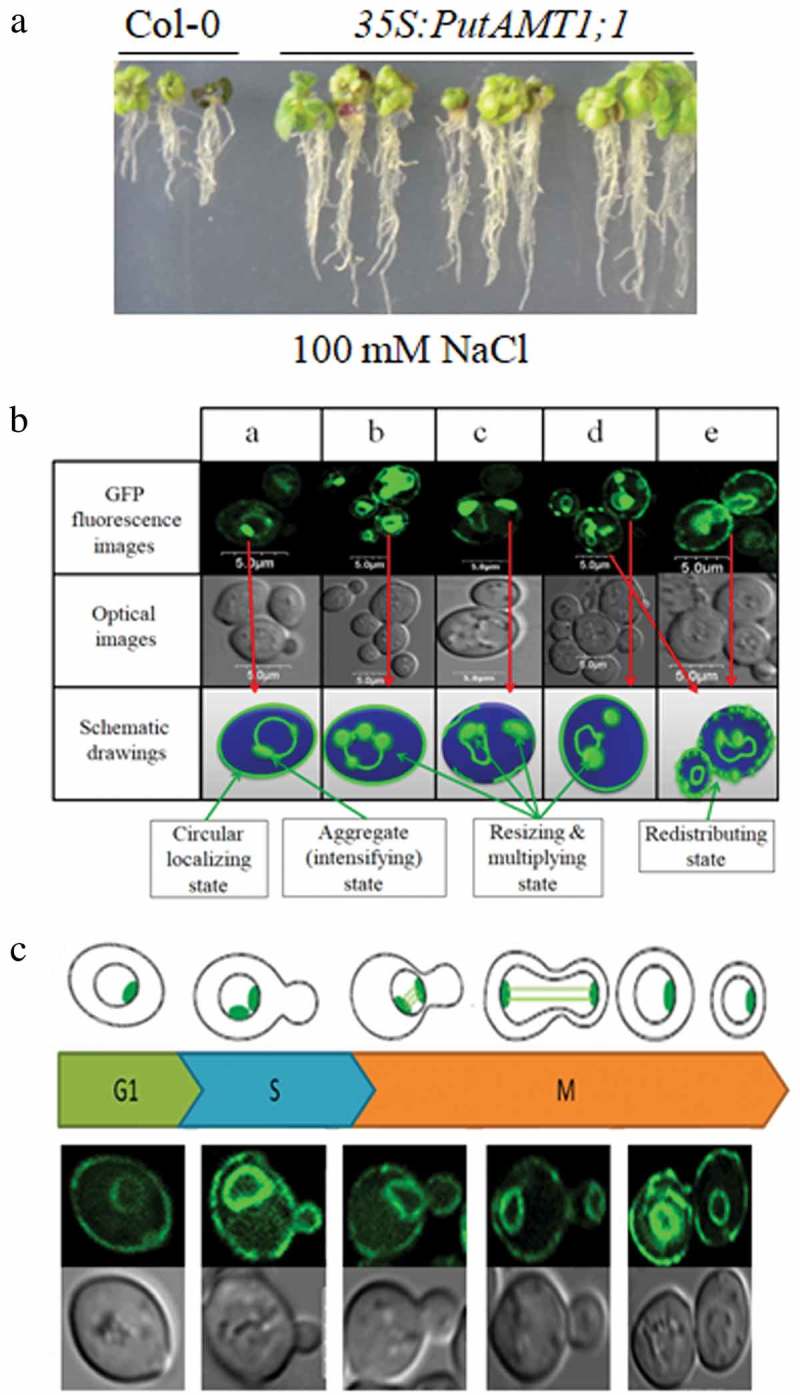

Plant ammonium uptake is mediated by ammonium transporter (AMT) family that can be subdivided into two subfamilies, AMT1 and AMT2 in plants.12 Moreover, physiological studies on NH4+ uptake in plant roots showed that there have two transport systems for NH4+, a high-affinity transport system (HATS) and a low-affinity transport system (LATS). HATS plays a major role when ammonium in the soil is at micromolar [NH4+], while LATS in plants mainly at millimolar or higher concentrations.13–15 In a previous study, we identified a high-affinity AMT1 transporter gene (PutAMT1;1) from Puccinellia tenuiflora.16 Compared to the wild-type, transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing PutAMT1;1 exhibit better growth phenotype in root length under low concentration of NH4+ condition. Besides NH4+, plant AMT1-type transporter is known to also permeate the substrate analog MeA, which is toxic to plants.17,18 MeA treatment resulted in the remarkable reductions in root growth for the transgenic lines with decolorization of the leaf.16 These findings suggest that PutAMT1;1 mediates MeA uptake from the medium to the roots, with the substance then being transported to the shoot. In addition, the pYES2-PutAMT1;1 transformant allowed yeast to grow under different pH conditions, ranging between 4.0 and 8.0; hence, PutAMT1;1 function is not pH sensitive.16 This result indicates that PutAMT1;1 can alleviate environmental pH stress. Our latest results show that overexpression of the PutAMT1;1 gene in Arabidopsis significantly improves salt tolerance during the early root growth stage after seed germination (Figure 1(a)), while there was no significant difference in wild-type and PutAMT1;1 transgenic lines under normal condition. This phenomenon seems to be related to our previous findings: blocking urease activity can alleviate the salt stress of Arabidopsis during the same growth stage.19 Therefore, we speculate that the former reduces the production of ammonia, while the latter is an effective way to accelerate the transport and distribution of ammonia, thereby alleviating the local toxic effects of ammonia.

Figure 1.

Expression and localization of PutAMT1;1 in Arabidopsis and yeast cells. (a) Growth of wild-type and PutAMT1;1 transgenic lines (lines #1, #2, and #3) on salt stress containing medium for 14 d. (b) GFP fusion proteins of PutAMT1;1 expressed in the yeast cells. (a–e) GFP fusion proteins of PutAMT1;1 are localized at the plasma membrane and around the nuclear periphery of yeast. (c) A suggested model for a possible correlation between fluorescence images of PutAMT1;1-GFP localization and cell cycle. All images were made with a TCS SP2 laser-scanning confocal image system (Leica). GFP fluorescence was excited with an argon laser (488 nm). The size of the scale bars is shown directly in the images.

Previous research indicates that all plant AMT1 proteins are localized in the plasma membrane;17,18,20,21 however, our confocal and immunogold electron microscopy assays demonstrate that PutAMT1;1 is primarily localized to the plasma membrane and nuclear peripheral and intimal systems of yeast and plant cells, and its localization pattern is more complex. Based on this idea, we observed a new dynamic positioning characteristic of PutAMT1;1 to further understanding the basis of its function in yeast cells. First, at the beginning of a typical film localization pattern, the green fluorescence was intensified locally along the membrane with weakening other part membrane (Figure 1(b)). After some time from the circular localization, the morphology of the intensified light appeared as bar- or globular-shaped along the membrane (Figure 1(b-a)). As the incubation time increased further, the number of the accumulated localization increased (Figure 1(b-b)). Subsequently, the intensified shapes merged into bigger size with deformation and/or disappearance of nuclear membrane shape (Figure 1(b-c)). Finally, the green light morphology recovered into plasma membrane shape again (Figure 1(b-d) and (e)) with the reappearance of peripheral rings of nuclear. It seems that there is a dynamic process of AMT localization. The dynamic changes were characterized into four processes: (1) circular localizing state along the membrane, (2) aggregate (intensifying) state, (3) multiplying and size-glowing state, and (4) redistributing state as shown in schematic drawings of Figure 1(c). We have observed the dynamic change of the PutAMT1;1 localization; the cause of the changes appeared in yeast is not clear. It seems this dynamic process contains the information of the cellular activity. Among our observed images, we have found the morphologies corresponding to the cell cycle as shown in Figure 1(c). In summary, PutAMT1;1-GFP will be a good candidate for visualizing the dynamic process of the cell cycle; on the other hand, PutAMT1;1 produces a large-scale aggregation state (possibly due to overexpression); however, the localization of PutAMT1;1 to the membrane system via protein sorting is not only orderly but also highly efficient during the cell division cycle. These observations may be helpful in obtaining insights into nitrogen metabolism and its function.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China (No. 31500501); Heilongjiang Province Government Postdoctoral Science Foundation (LBH-Q18008); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572016CA14); State Key Laboratory of Subtropical Silviculture Open Fund (KF201707); Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (No. IRT17R99).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Patterson K, Cakmak T, Cooper A, Lager I, Rasmusson AG, Escobar MA.. Distinct signalling pathways and transcriptome response signatures differentiate ammonium and nitrate-supplied plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:1486–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AJ, Fan XR, Orsel M, Smith SJ, Wells DM. Nitrate transport and signalling. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:2297–2306. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom AJ, Sukrapanna SS, Warner RL. Root respiration associated with ammonium and nitrate absorption and assimilation by barely. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1294–1301. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazzarrini S, Lejay L, Gojon A, Ninnemann O, Frommer WB, von Wiren N. Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 1999;11:937–947. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britto DT, Kronzucker HJ. NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. J Plant Physiol. 2002;159:567–584. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-0774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hachiya T, Watanabe CK, Fujimoto M, Ishikawa T, Takahara K, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H, Uesono Y, Terashima I, Noguchi K. Nitrate addition alleviates ammonium toxicity without lessening ammonium accumulation, organic acid depletion and inorganic cation depletion in Arabidopsis thaliana shoots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:577–591. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteban R, Ariz I, Cruz C, Moran JF. Review: mechanisms of ammonium toxicity and the quest for tolerance. Plant Sci. 2016;248:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerendás J, Zhu Z, Bendixen R, Ratcliffe RG, Sattelmacher B. Physiological and biochemical processes related to ammonium toxicity in higher plants. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 1997;160:239–251. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horichani F, Rbia O, Hajri R, Aschi-Smiti S. Nitrogen nutrition ammonium toxicity in high plants. Int J Bot. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.3923/ijb.2011.1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britto DT, Siddiqi MY, Glass ADM, Kronzucker HJ. Futile transmembrane NH4+ cycling: a cellular hypothesis to explain ammonium toxicity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4255–4258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronzucker HJ, Siddiqi MY, Glass ADM. Kinetics of NH4+influx in spruce. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:773–779. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loque D, von Wiren N. Regulatory levels for the transport ammonium in plant roots. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1293–1305. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toshihiko K, Toshihiko H, Tadahiko M, Kunihiko O, Tomoyuki Y. Characteristics of ammonium uptake by rice cells in suspension culture. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1994;40:333–338. doi: 10.1080/00380768.1994.10413307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kronzucker HJ, Britto DT, Davenport RJ, Tester M. Ammonium toxicity and the real cost of transport. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:335–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang MY, Siddiqi MY, Ruth TJ, Glass DM. Ammonium uptake by rice roots. II. Kinetics of 13NH4+ influxes across the plasmalemma. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:1259–1267. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bu Y, Sun B, Zhou A, Zhang X, Lee I, Liu S. Identification and characterization of a PutAMT1;1gene from Puccinellia tenuiflora. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e13111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan L, Loque D, Kojima S, Rauch S, Ishiyama K, Inoue E. The organization of high-affinity ammonium uptake in Arabidopsis roots depends on the spatial arrangement and biochemical properties of AMT1-type transporters. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2636–2652. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loque D, Yuan L, Kojima S, Gojon A, Wirth J, Gazzarrini S, Ishiyama K, Takahashi H, von Wiren N. Additive contribution of AMT1;1 and AMT1;3 to high-affinity ammonium uptake across the plasma membrane of nitrogen-deficient Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 2006;48:522–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuanyuan B, Kou J, Sun B, Takano T, Liu S. Adverse effect of urease on salt stress during seed germinationin Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1308–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludewig U, von Wiren N, Frommer WB. Uniport of NH4+ by the root hair plasma membrane ammonium transporter LeAMT1;1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13548–13555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludewig U, Wilken S, Wu BH, Jost W, Obrdlik P, EIBakkoury M, Marini AM, Andre B, Hamacher T, Boles E, et al. Homo-and hetero-oligomerization of ammonium transporter-1 NH4+uniporters. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45603–45610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]