Introduction

Measles is a highly contagious, albeit vaccine-preventable, acute viral disease that can cause rash, fever, diarrhea, pneumonia, encephalitis, and death. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 134,200 people died from measles in 2015 – mostly children under the age of 5 (1). Although endemic transmission of measles in the United States was declared to be eliminated in 2000 (2), importations from countries in which measles is still endemic continue to occur. On April 10, 2017 in Minnesota, a 25-month-old child who had no history of receipt of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine manifested measles infection (3). The virus was spread quickly to two other children who attended the same childcare center. The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) instituted outbreak investigation and response activities, and the outbreak resulted in a total of 79 confirmed measles cases before it was declared to be over on August 25, 2017. The 79 measles cases were nine more than United States total in 2016 and 23 more than the previous 20 years combined in Minnesota.

Despite repeated challenges from measles introductions, most importations of measles do not lead to further spread, and outbreaks are generally small and short-lived (1). The success of the measles-control program in the United States is the result of a high proportion of coverage with a safe and efficacious vaccine (the measles–mumps–rubella [MMR] vaccine) due to state-level mandatory vaccination statutes (4), combined with the aggressive implementation of control measures once cases are detected. In general, MMR uptake for Minnesota children is near the average of other states. In 2016, 92% of Minnesota children aged 19–35 months were up-to-date on the MMR vaccine (5) and 92.8% of students entering kindergarten in the state were up-to-date on MMR (6). However, recent research has shown that localized clusters of low vaccine uptake are found throughout regions with otherwise high levels of uptake at national (7), state (8), and local (9, 10) scales. Localized outbreaks can and do occur within these clusters, putting surrounding communities at risk medically and financially (11).

The 2017 outbreak in Minnesota was largely confined to Minneapolis’ Somali population, with 64 of the 79 cases occurring in this community. Autism spectrum disorders are more common in the Somali community (12), and the Somali community in Minnesota has extremely low MMR uptake largely due to a misplaced fear of the vaccine’s link to autism (13–15). The 2017 outbreak was preceded by a smaller measles outbreak in Minnesota in 2011, of which 8 of 21 cases were Somalis (16).

Although the 2017 Minnesota measles outbreak was largely confined to a specific socio-cultural community and did not manifest into a statewide epidemic, this does not mean that other places in the state were not potentially at risk. San Diego’s 2008 outbreak of 839 persons was found to be possible in an otherwise high-coverage area because of mixing populations of intentionally unvaccinated in an otherwise immunized cohort (10, 11). The purpose of this research is to map the geographic distribution of MMR vaccination coverage in Minnesota’s schools and the location of confirmed measles cases in the 2017 outbreak in an effort to highlight those regions that were potentially at risk for measles transmission, as well as to identify other vulnerable regions where interventions are needed to improve coverage.

Methods

We gathered vaccination and enrollment data for incoming kindergarteners in Minnesota over Fall 2012–2016 from the Minnesota Department of Health (17, 18). The data are available by school, school district, and county, and included children entering schools that had 5 or more incoming students (roughly 94% of all kindergarteners in Minnesota are included). This dataset differs from the National Immunization Survey because of its wide spatial extent with the tradeoff of existing at an aggregated scale. Because five years of data were available, we combined them to estimate the overall MMR coverage in the state’s public elementary schools (grades K-4) (19). To accomplish this, we summed the yearly number of incoming kindergarteners and the number that were fully up-to-date (2 doses) on their MMR vaccine upon school entry, and then calculated the percent of up-to-date students.

We used the included public/private school district information to differentiate public and private schools. We attached the MMR coverage data to a spatial data layer representing Minnesota’s public school district boundaries (private school boundaries are not available) gathered from the Minnestota Geospatial Commons (20) for mapping purposes. We also gathered the number of measles cases by county from Minnesota’s Measles Outbreak page (21) and attached these data to a spatial data layer of the state’s counties. We then overlaid the MMR vaccination data with the measles data for analysis.

Results

Full, 2-dose MMR coverage has substantial variation across districts and district types, as shown in Table 1. The overall coverage for MMR vaccination for public school students in grades K-4 is 93.35%. The minimum full MMR coverage is 58.33% and the maximum is 100% in public schools. Private schools, which represent approximately six percent of Minnesota’s kindergarten enrollment, have a substantially lower coverage, with an overall coverage of 83.00% across the five years. There was at least one observed school with 0% coverage (in 2012–13), and numerous schools below 40% (which is lower than any minimum value for public school districts) were present in each year for private school districts.

Table 1.

2-Dose MMR coverage in Minnesota public and private school districts.

| 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Students | 72,466 | 70,844 | 68,756 | 67,564 | 66,861 | 346,491 |

| Overall Coverage | 93.76 | 93.36 | 93.69 | 93.08 | 92.80 | 93.35 |

| Public Schools | ||||||

| Number of Students | 68,442 | 66,906 | 64,709 | 63,198 | 62,264 | 325,519 |

| Combined MMR Coverage | 94.52 | 93.81 | 94.32 | 93.82 | 93.57 | 94.02 |

| Minimum MMR Coverage | 43.62 | 60.34 | 58.97 | 48.28 | 50.00 | 58.33 |

| Maximum MMRCoverage | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Private Schools | ||||||

| Number of Students | 4,024 | 3,938 | 4,047 | 4,366 | 4,581 | 20,956 |

| Combined MMR Coverage | 80.94 | 85.73 | 83.72 | 82.43 | 82.36 | 83.00 |

| Minimum MMR Coverage | 0.00 | 36.36 | 23.08 | 22.22 | 34.78 | 50.65 |

| Maximum MMRCoverage | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Percent of Students in Private School | 5.55 | 5.56 | 5.89 | 6.46 | 6.85 | 6.05 |

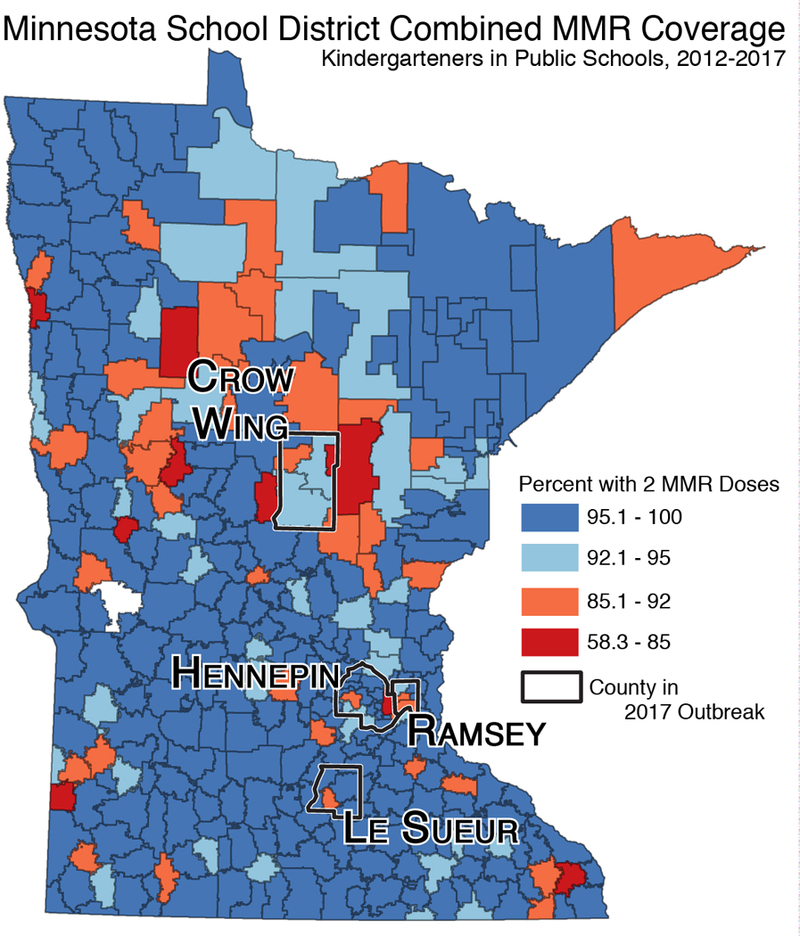

Full MMR coverage by school district is mapped in Figure 1, showing a large amount of geographic variation throughout the public school districts of the state. Many of the districts with lower levels of MMR coverage are in the northern half of the state. The map classes in Figure 1 are broken at 92% and 95% coverage, which are oft encountered threshold values associated with herd immunity for measles (22). Because these populations are not homogenous, the thresholds hold limited value from a quantitative perspective (23). However, they do assist in linking the observed coverage values to values that have some (if limited) interpretive usefulness. Furthermore, recent research has shown that non-random mixing and heterogeneity can increase the coverage required for herd immunity (10), which may make 92% and 95% underestimates of safe levels of coverage.

Figure 1.

2-Dose MMR coverage in Minnesota public school districts and counties with confirmed measles cases.

Measles cases in the 2017 outbreak were located in Crow Wing (4), Hennepin (70), Le Sueur (2), and Ramsey (3) counties. Figure 1 shows that there are school districts with relatively low MMR coverage (85.1–92%) located in all four counties and school districts with extremely low coverage (65.6–85%) located in Crow Wing and Hennepin county. Furthermore, Figure 1 also shows that there are numerous school districts with low MMR coverage in very close geographic proximity to Crow Wing county.

Discussion

The MMR vaccine is highly effective, and its uptake is critical (24). Despite the protection the vaccine affords, measles outbreaks continue to occur in the United States. The Minnesota Department of Health estimated potentially more than 8,000 exposures to the virus and its costs for the outbreak response were more than $900,000 (21). State law requires that children aged 2 years or older receive the MMR vaccine, and compliance was high until 2008. Uptake among Somali-Americans began to fall starting in 2008, and by 2014 coverage had fallen to around 42 percent among Somali Minnesotan 2-year-olds (13). The Somali community has shown a higher prevalence of autism compared to other ethnic groups, and fears of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism have left it vulnerable (15, 16).

The 2017 outbreak was relatively isolated. However, the statewide MMR coverage data suggests that other communities were at risk given their geographic proximity to the outbreak and modest coverage. In addition, the outbreak mostly occurred as schools were out of session – an outbreak that had schools as an additional transmission location might have resulted in many more cases. The Minnesota measles outbreak underscores the importance of addressing vaccine hesitancy and low levels of uptake from multiple angles. Research has shown in situations where parents believe vaccines are unsafe that health care providers can be highly influential in the final vaccination decision (25, 26). School immunization rates are strongly associated with school compliance enforcement by public health officials (27). Better enforcement of MMR vaccine compliance in child care and schools could have a significant impact on preventing disease going forward, particularly among the Somali population in Minnesota where there were previous measles outbreaks. But, these efforts should be done in tandem with continued trust building with the community and fleshing out culturally appropriate and effective ways to deal with questions, concerns, and misinformation regarding the MMR vaccine.

Contributor Information

Timothy F. Leslie, Department of Geography and Geoinformation Science, 4400 University Drive, MS 6C3 George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA

Paul L. Delamater, Department of Geography University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Y. Tony Yang, Department of Health Administration and Policy George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Measles Fact Sheet http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs286/en/, last accessed February 15, 2018.

- 2.Katz SL, Hinman AR. Summary and conclusions: measles elimination meeting, 16–17 March 2000. J Infect Dis 2004;189:Suppl 1:S43–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall V, Banerjee E, Kenyon C, Strain A, Griffith J, Como-Sabetti K, Heath J, Bahta L, Martin K, McMahon M, Johnson D, Roddy M, Dunn D, Ehresmann K. Measles Outbreak - Minnesota April-May 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017. July 14;66(27):713–717. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith PJ, Shaw J, Seither R, Lopez A, Hill HA, Underwood M, Knighton C, Zhao Z, Ravanam MS, Greby S, Orenstein WA. Vaccine exemptions and the kindergarten vaccination coverage gap. Vaccine. 2017. September 25;35(40):5346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disese Control. ChildVaxView Initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/index.html, last accessed February 15, 2018.

- 6.Seither R, Calhoun K, Street EJ, et al. Vaccination Coverage for Selected Vaccines, Exemption Rates, and Provisional Enrollment Among Children in Kindergarten — United States, 2016–17 School Year. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2017; 66: 1073–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PJ, Marcuse EK, Seward JF, Zhao Z, Orenstein WA. Children and adolescents unvaccinated against measles: geographic clustering, parents’ beliefs, and missed opportunities. Public Health Reports. 2015. September;130(5):485–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT, Jacobsen KH. An approach for estimating vaccination coverage for communities using school-level data and population mobility information. Applied Geography 2016; 71: 123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M. Geographic clusters in underimmunization and vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015. February 1;135(2):280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasser JW, Feng Z, Omer SB, Smith PJ, Rodewald LE. The effect of heterogeneity in uptake of the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine on the potential for outbreaks of measles: a modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016. May 1;16(5):599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugerman DE, Barskey AE, Delea MG, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Bi D, Ralston KJ, Rota PA, Waters-Montijo K, LeBaron CW. Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population, San Diego, 2008: role of the intentionally undervaccinated. Pediatrics. 2010. April 1;125(4):747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnevik–Olsson M, Gillberg C, Fernell E. Prevalence of autism in children born to Somali parents living in Sweden: a brief report. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2008. August 1;50(8):598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt A, Hall-Lande J, Hamre K, Esler AN, Punyko J, Reichle J, Gulaid AA. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Prevalence in Somali and Non-Somali Children. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(8):2599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson C1, Rai D, Goodman A, Lundberg M, Idring S, Svensson A, Koupil I, Serlachius E, Dalman C. Migration and autism spectrum disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gahr P, DeVries AS, Wallace G, et al. An Outbreak of Measles in an Undervaccinated Community. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e220–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahta L, Ashkir A. Addressing MMR Vaccine Resistance in Minnesota’s Somali Community. Minn Med 2015; 98: 33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minnesota Department of Health. School Immunization Data http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/immunize/stats/school/index.html, last accessed February 15, 2018.

- 18.Leslie TF, Street EJ, Delamater PL, Yang YT, Jacobsen KH. Variation in Vaccination Data Available at School Entry Across the United States. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 2180–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Yang YT. California Senate Bill 277’s Grandfather Clause and Nonmedical Vaccine Exemptions in California, 2015–2022. JAMA Pediatrics 2016; 170: 619–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minnesota Geospatial Commons. Minnesota School District Boundaries https://gisdata.mn.gov/dataset/bdry-school-district-boundaries, last accessed February 15, 2018

- 21.Minnesota Department of Health. Health officials declare end of measles outbreak http://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2017/measles082517.html, last accessed February 15, 2018

- 22.Fine PEM. Herd Immunity: History, Theory, Practice. Epidemiologic Reviews 1993; 15: 265–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng Z, Hill AN, Smith PJ, Glasser JW. An elaboration of theory about preventing outbreaks in homogeneous populations to include heterogeneity or preferential mixing. Journal of theoretical biology. 2015. December 7;386:177–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campos-Outcalt D Measles: why it’s still a threat: a recent outbreak in Minnesota underscores the need to maintain vigilance and adhere to best practices in immunization and containment of known cases. Journal of Family Practice. 2017; 66(7):446–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith PJ, Kennedy AM, Wooten K, Gust DA, Pickering LK. Association Between Health Care Providers’ Influence on Parents Who Have Concerns About Vaccine Safety and Vaccination Coverage. Pediatrics. 2006. November 1;118(5):e1287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry NJ, Danchin M, Trevena L, Witteman HO, Kinnersley P, Snelling T, Robinson P, Leask J. Sharing knowledge about immunisation (SKAI): An exploration of parents’ communication needs to inform development of a clinical communication support intervention. Vaccine. 2018. February 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall KJ, Howell MA, Jansen RJ, Carson PJ. Enforcement Associated With Higher School-Reported Immunization Rates. American journal of preventive medicine. 2017. December 1;53(6):892–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]