Abstract

The Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT) is a temporally-dynamic process model of mindful positive emotion regulation that elucidates downstream cognitive-affective mechanisms by which mindfulness promotes health and resilience. Here we review and extend the MMT to explicate how mindfulness fosters self-transcendence by evoking upward spirals of decentering, attentional broadening, reappraisal, and savoring. Savoring is highlighted as a key means of inducing absorptive experiences of oneness between subject and object, amplifying the salience of the object while imbuing sensory-perceptual field with affective meaning. Finally, this article provides new evidence that inducing self-transcendent positive emotions and nondual states of awareness through mindfulness-based interventions may restructure reward processing and thereby produce therapeutic effects on addictive behavior (e.g., opioid misuse) and chronic pain syndromes.

Keywords: broaden-and-build, nondual awareness, opioid, positive psychology, reward

Mindfulness research burgeoned in the early 1990s and contemplative scientists have since made significant strides toward illuminating the nature of mindfulness. Even so, scholars have paid relatively little attention to the positive mechanistic sequelae of mindfulness – i.e., to answering the question “How does mindfulness enhance salutary cognitive-affective states to promote health and resilience?”

Informed both by the systems theory of second-order cybernetics [1] and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions [2], we [3–5] proposed that mindfulness was a central mechanism for energizing upward spirals of positive psychological processes. By virtue of its deautomatization [6], decentering [7], attention regulation [8], and perspective-shifting functions [9], we posited that mindfulness provides the system perturbation needed to disrupt habitual cognitive schemas and broaden awareness to encompass an enlarged set of contextual data from which new, adaptive appraisals of self and world can be constructed. Mindfulness-induced positive emotions increase this broadening and tune attention towards previously unattended positive information. Integrating a widened array of positive and negative contextual features within the broadened scope of awareness occasioned by mindfulness can reconfigure cognitive structures within working memory and thereby facilitate reappraisal of adversity as a source of psychological growth – fueling resilience in the face of suffering. In turn, the positive emotions stimulated by this mindful reappraisal process can be further amplified through use of mindfulness to savor the pleasant sensory features and higher-order affective meaning of the situational context. We theorized that such positive affectivity infuses the upward spiral with hedonic tone and enriches eudaimonic dimensions of adaptation to life’s challenges.

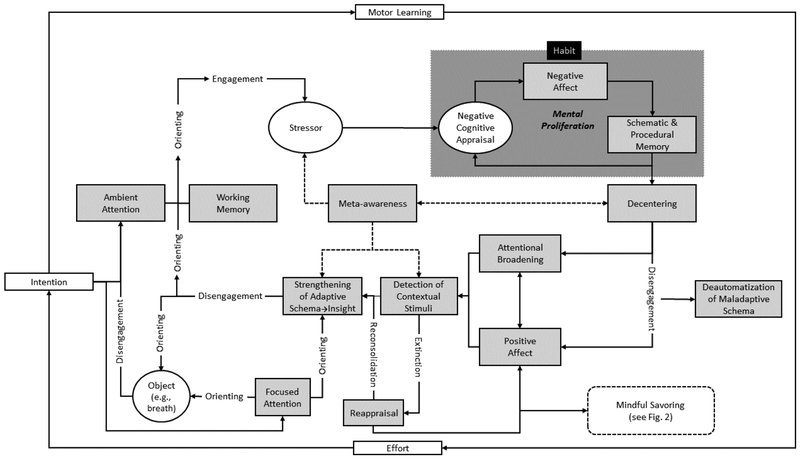

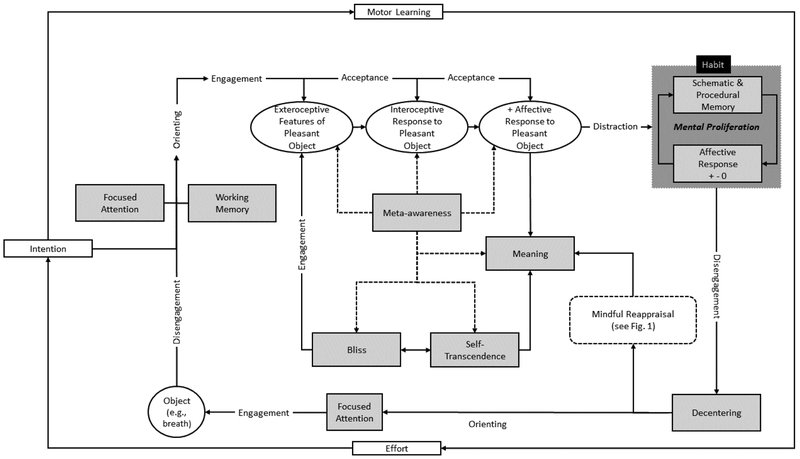

Despite the promise of this conceptual model, its tenets were sometimes misunderstood. For example, some scholars interpreted the model as posing an ontological identity between mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring, which it did not. To the contrary, the model proposed that these processes are distinct yet complementary, and that flexibly and rapidly toggling between non-evaluative states of mindful awareness and evaluative processes like reappraisal and savoring would facilitate emotion regulation and engender eudaimonic meaning. This notion is echoed by recent neuroimaging network analyses indicating that connectivity between frontoparietal and default mode networks in the brain may subserve the switch from mindfulness to evaluation [10]. To clarify the tenets of our model, we crystallized our conceptual framework into the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT) [11,12], a formal theory with two primary, empirically-tractable hypotheses: 1) mindfulness promotes reappraisal (the mindful reappraisal hypothesis, see Figure 1); and 2) mindfulness promotes savoring (the mindful savoring hypothesis, see Figure 2). These two tenets of MMT are supported by an array of cross-sectional, observational, experimental, and clinical studies (for a review, see [11]). Across this body of research, mindfulness (as a state, trait, and practice) is associated with both reappraisal and savoring. More recently, results from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) provided strong support for the mindful reappraisal hypothesis, by demonstrating that even absent training in reappraisal, 8 weeks of MBSR increased reappraisal efficacy to a similar extent as cognitive-behavioral therapy, a treatment that provides explicit instruction in reappraisal [13]. Multivariate analyses of longitudinal data from this and another RCT found evidence for the mechanistic causal pathways (decentering → attentional broadening → reappraisal → trait positive affect/well-being) specified by the MMT [14]. Although the MMT has been successful in predicting and explaining empirically observed relations between mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring, the theory’s original scope was constrained by parsimony to a limited set of basic cognitive-affective processes. Here, we briefly present an extension of the MMT to the more complex positive psychological state of self-transcendence, and its specific application to the treatment of two intersecting clinical domains with particular relevance to the 21st century, addiction and chronic pain. Epidemiologic research has directly linked increased prevalence of these two “diseases of despair” to the rising tide of morbidity and mortality (an increase of 0.5% a year since 1998) observed among white U.S. adults [15].

Figure 1. Proposed causal model of the mindful reappraisal hypothesis.

adapted from Vago & Silbersweig’s mindfulness process models [56]. Intention is formed to either focus attention on an object of mindfulness (e.g., breath) or recruit ambient attentional networks (i.e., practice open monitoring). When attention becomes engaged by a stressor, the ensuing negative cognitive appraisal elicits negative affect which activates maladaptive schemas. Mindful decentering from this circuit of mental proliferation facilitates attentional disengagement from the stressor and deautomatizes maladaptive schematic responses, resulting in relief and calm – low arousal positive emotions that, when combined with positive affective states like relaxation, contentment, and joy induced by mindfulness practice, broaden the scope of attention (see [2]) to encompass previously unattended contextual stimuli. Affective tuning of the attentional system allows for detection of positive contextual features, resulting in integration of a broadened array of pleasant and unpleasant stimuli that shifts perception of environmental contingencies, extinguishing the conditioned (cognitive, affective, and behavioral) response as the meaning of the stressor stimulus is reappraised. Reconsolidation of this reappraisal strengthens new, adaptive schemas that may then become the target of focused attention and contemplation during analytical meditation. Meta-awareness oversees the entire mindful reappraisal process by monitoring the stressor, facilitating decentering to identify the non-veridicality of the stress appraisal, tracking the arising of previously unattended (positive) contextual data, and reconsolidating the reappraisal into schematic memory as an insight. Once insight has occurred, the practitioner may disengage from the reappraisal and return focused attention back to the object of mindfulness (e.g., the breath), recruit ambient attention to the ever changing nature of the stressor-in-context, or mindfully savor the positive emotions and affective meaning generated from this process (see Figure 2). Repetitions of this circuit facilitate learning, resulting in increasing effortlessness of the mindful reappraisal practice.

Figure 2. Proposed causal model of the mindful savoring hypothesis.

adapted from Vago & Silbersweig’s mindfulness process models [56]. Intention is formed to focus attention on the object of savoring (i.e., a pleasant sensory object). Attention orients toward the pleasant exteroceptive and proprioceptive features of the object. When interoceptive and positive affective responses to the object enter awareness, cultivation of an attitude of acceptance and openness allows for heightened sensory-perceptual contact between subject and object. Meta-awareness of the phenomenological signature of structural coupling between self and world (e.g., a perceived fading of the boundaries of the “skin encapsulated ego” [57] and a sense of oceanic oneness) results in self-transcendence and bliss, which imbues the stimulus context with affective meaning while stabilizing attention into a deep form of absorption with the object of savoring. When distraction occurs, decentering facilitates disengagement from the circuit of mental proliferation, freeing cognitive resources to reorient attention to the breath as a means of stabilizing concentration before disengaging and focusing attention back on the object of savoring. Alternatively, mindful reappraisal can be engaged to regulate mental proliferation by reconsolidating cognitive appraisals and integrating memories and affective responses arising during mind wandering into the meaning-making process of savoring (see Figure 1). Repetitions of this circuit facilitate learning, resulting in increasing effortlessness of the mindful savoring practice.

Extending the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory towards Self-Transcendence

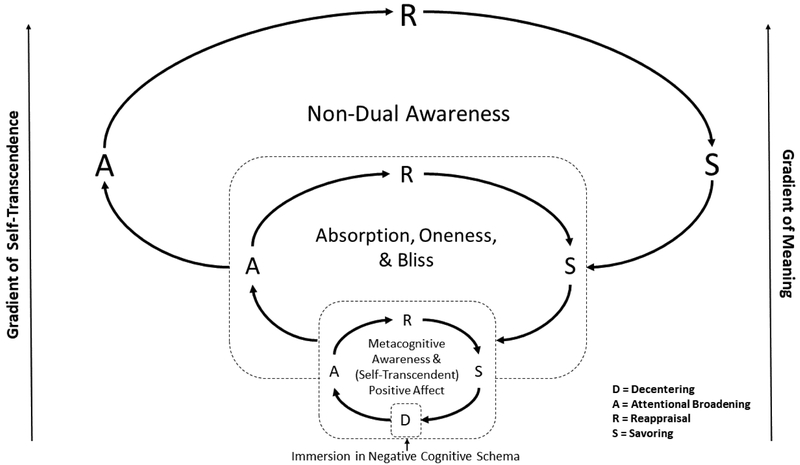

The MMT specifies a recursive cycle of positive psychological processes, including decentering, attentional broadening, reappraisal, and savoring, that kindles momentary states of meta-awareness infused with positive affect, such as the self-transcendent positive emotions of awe, compassion, elevation, gratitude, and love. This cycle, when repeatedly activated, builds an upward spiral (see Figure 2, innermost loop) that stimulates a gradient of self-transcendence (see Figure, leftmost vertical arrow) extending from decentered meta-awareness of mental objects to experiences of oneness between subject and object, and finally, to nondual states in which the subject-object dichotomy is completely (albeit temporarily) transcended. A similar gradient of self-transcendence has been suggested [16]; the MMT postulates that iterations of decentering, broadening, reappraisal, and savoring propel advancement along this gradient. With each iteration of the MMT cycle, momentary states of meta-awareness and self-transcendent positive emotions accrue into the durable trait-like propensity towards dispositional mindfulness, selfless happiness [17], and the sense of meaningfulness that arises during long-term cultivation of meditative insights. These insights themselves may unfold along a gradient of meaning (see Figure, rightmost vertical arrow), from the distancing reappraisal that arises during decentering, “Thoughts are not facts, they are transitory mental experiences,” to the positive reappraisal emerging from extended contemplation, “Adversity is the path towards psychological growth,” to the ontological reappraisal revealed in the deepest meditative states, “Self is not permanent but rather is empty and interdependent” [12,18].

In the MMT, mindfulness facilitates decentering from schematized appraisals of self and world into a state of meta-awareness in which self-referential appraisals are attenuated and transcended. This state expands the field of awareness beyond self-relevant information to encompass previously unattended contextual data from which reappraisals can be formulated. By virtue of positive affective tuning of the attentional system [19], mindfulness facilitates savoring, a process of orienting toward the pleasant sensory features of a stimulus context while cultivating meta-awareness of the positive emotions and higher-order meanings that flow from the rewarding experience. Insofar as pleasure is not a property of the object but rather arises from consciousness of its homeostatic self-relevance to the subject [20], mindfully savoring pleasure involves a degree of self-reflexivity that cultivates meta-awareness [21]. To the extent that mindfulness promotes inhibitory control in affective contexts [22], mindfulness may inhibit attentional biases [23] and cognitive-emotional interference that prevent sensorial data from entering the buffer of working memory [24], thereby improving psychological contact with the sense object. Mindfulness-based amplification of sensory-perceptual contact, evident in measures of sensory function [25] and electrocortical markers of emotional attention [26], may increase reward experience from naturally rewarding stimuli (i.e., social affiliation, food, natural beauty, for example see [27]. Through these mechanisms, mindfulness may magnify the impact of savoring on increasing positive emotions [28], allowing them to arise out of heightened phenomenological contact between subject and object.

In addition, mindful reappraisal may be needed to engender an attitude of openness and acceptance towards the object of savoring when maladaptive cognitive schema such as “I don’t deserve to feel good” and “The world is a bad place” are activated. Indeed, acceptance appears to be essential to cultivating positive emotions through mindfulness [29], a psychological parallel to the evolutionarily conserved behavior of acceptance wriggles [21] that mammals exhibit to prolong and magnify hedonic contact with the rewarding stimulus, such as curling the tongue to savor palatable food or caressing the skin of a loved one. This concept implies that acceptance of the stimulus affords greater attention to its qualities, which then allows for an expanded emotional experience. Moreover, within social contexts, the tandem practices of reappraisal and savoring hold the potential to foster experiences of connection, such as the positivity resonance emerging from the affective and physiological synchrony evident in loving interpersonal interactions [30] – a positive feedback loop in which the salutary psychophysiological states of two or more relational partners reciprocally energize positive emotions and prosocial behavior in one another. We posit that mindfulness of connection between self and nonself (human or otherwise) might be evident along the continuum of increasing self-transcendence and meaningfulness. This continuum begins with awareness of simple sensorimotor coupling with the natural environment (e.g., savoring the beauty of a mountaintop sunset with awe) and expands to awareness of social-affective coupling with the social environment (e.g., savoring positivity resonance with warmth, kindness, and feelings of connection), and ultimately shifts to awareness of systemic structural coupling between self and world. Phenomenologically, this shift may be characterized by a perceived softening of boundaries between self and non-self, either in the form of a relational unity (a feeling of oceanic oneness) or an annihilational unity (a fading of the sense of self coupled with a spacious opening of the field of awareness) [31,32]. At the highest level of abstraction, the experience of self is fully transcended by the emergence of non-dual awareness – a temporary experiential collapse of the subject-object dichotomy that organizes ordinary human consciousness [33]. According to Yogācāra philosophy, the duality of subject and object is a form of ignorance (avidyā) that, when dispelled by mindfulness meditation, reveals a self-transcendent, non-dual state [34]; non-dual awareness is achieved, according to the Mahāmudrā tradition, by effortlessly resting awareness in the mind’s natural state [34].

Insofar as self-transcendence suppresses self-referential processing that in normative states of consciousness delimits criteria for meaning to that which is “good/bad for me” [35], the conscious filter that typically parses the salience of stimuli for self-relevance may begin to relax, resulting in positive emotions and enhanced apperception of affective meaning across the sensory-perceptual field [31]. According to the Theravadan tradition of the jhānas, as self-transcendence deepens, the process of absorption yields bliss [36] – possibly reflected in hyperactivation of brain reward systems [37]. This profound positive affective state is distinguished from sense-bound pleasure by its desirelessness and lack of self-reference [38]; yet, in the Guhsamāja Tantra it was recognized that mindful engagement with pleasant sense objects can produce bliss, yielding meditative absorption (samādhi) and mental stability needed to realize non-duality [39]. At this point, attention may fully disengage from the object and turn back upon itself to savor the blissful field of consciousness that has been liberated from mentation through iterations of decentering, broadening, and reappraisal. At its zenith, the experience of self-transcendence achieved through deep states of mindfulness can produce a sense of ultimate meaningfulness [40]. On a neural level, meaning induced by self-transcendence might be reflected in increased functional connectivity between dorsal attentional, default mode, and salience networks observed during the practice of meditation [41]. Though such self-transcendent experiences have been typically conceptualized as uncommon and accessible to only the most adept meditators, recent findings indicate that they also occur with some frequency in novice meditators and meditation-naïve samples [32].

Clinical Applications of the MMT to Addiction and Chronic Pain

The MMT has been applied to biobehavioral models of psychological treatment for addiction and chronic pain [18]. Such forward-translation of the MMT suggests that evoking hedonic and eudaimonic well-being through the integration of mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring would attenuate (physical and emotional) pain and enhance natural reward processing, thereby decreasing the propensity to engage in addictive behaviors.

Evidence for these hypotheses has been generated by RCTs of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) as a treatment for prescription opioid misuse among chronic pain patients [42,43]. As a mindfulness-based intervention founded on the MMT, the MORE treatment sequence begins with a foundation of mindfulness training, which, by virtue of its effects on augmenting cognitive control capacity, aims to facilitate reappraisal and savoring skills introduced later in the intervention. MORE leverages this synergy of mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring techniques to restructure reward processing from valuation of drug-related rewards back to valuation of natural rewards – a therapeutic process hypothesized to reduce drug craving (i.e., the restructuring reward hypothesis [18]). In this way, MORE targets the hedonic dysregulation that undergirds opioid misuse - a downward spiral of sensitization to pain and drug-related cues coupled with decreased responsiveness to natural rewards that compels opioid dose escalation as a means of preserving a dwindling sense of well-being [44,45].

Outcome data from two separate Stage 2 RCTs indicate that MORE significantly decreases chronic pain, craving, and opioid misuse behaviors [42,43]. Ecological momentary assessments from the first of these trials revealed that compared to an active control group, participants in MORE were approximately 2.75 times more likely to be positively affectively regulated (i.e., able to maintain positive affect from moment-to-moment and/or recover positive affect after a momentary negative affective perturbation) over the course of treatment, and increases in the trajectory of momentary positive affect predicted decreases in opioid misuse [46]. These improvements in subjective positive affect were complemented by evidence of enhanced cardiac-autonomic [47] and neurophysiological indices of natural reward processing following MORE [48]. In support of the restructuring reward hypothesis, MORE’s effects on increasing autonomic and EEG responses to natural reward stimuli were associated with reductions in craving [47,48]. Recent analyses indicated that MORE increased autonomic responsiveness to natural reward cues relative to drug cues, and that such increases in relative responsiveness of natural to drug-related reward significantly predicted decreased opioid misuse at follow-up [49].

New data from a second RCT indicates that MORE robustly increases MMT mechanisms including positive affect, savoring, meaning in life, and the proclivity to experience self-transcendent, non-dual states of awareness; in a multivariate path analysis, these positive psychological effects were linked with decreases in pain severity and opioid misuse risk [42]. How should these linkages be understood in light of the MMT developments discussed in this article? With respect to alleviation of physical pain, in addition to corticothalamic modulation of ascending nociceptive input [50] and shifting from affective to sensory processing of pain sensations [43,51], mindfulness-based pain relief may derive in part from the positive affective states [52] and the associated self-transcendence generated during mindfulness practice. When awareness expands beyond the mortal coil, pain is likely to become less dominant in consciousness. Similarly, in addition to the effects of mindfulness on decreasing reactivity to drug cues [23,47] and restructuring reward processing in corticostriatal circuitry [53], mindfulness-induced self-transcendence might reveal the inherent meaningfulness of the basic sense of one’s own existence and thereby bring relief from addictive cravings. When awareness expands to encompass the unity of self and world, any strong sense of lack is likely to recede. Recent psychometric advances [32] will allow additional quantitative investigation of self-transcendence as a therapeutic mechanism of action, as well as help to unpack the antecedents and neurobiological mediators of self-transcendent states of awareness.

These findings yield testable hypotheses concerning the clinical impact of the successive upward spirals within the MMT. They also help to advance the concept of mindfulness by raising novel questions that are now within the scope of scientific inquiry. Among these are: To the extent that mindfulness facilitates “seeing things as they are,” is the self a discrete entity separate from its environment, or instead part of an interdependent, non-dual system? Is mindful reappraisal of adversity a path to awakening [54]? And, is the awakened mind a blank or neutral state, or rather, infused with a “basic goodness” to be savored [55]? We encourage others to join us in our efforts to address these and related empirical questions stemming from the revision to MMT we have sketched here.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to acknowledge David Vago for providing consultation concerning the development of Figures 1 and 2 and Adam Hanley for his assistance in developing Figure 3 in this manuscript.

Figure 3. Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (MMT) extended toward self-transcendence.

This extension of the MMT proposes that iterations of decentering, attentional broadening, reappraisal, and savoring extricate consciousness from immersion in negative cognitive schema to kindle momentary states of meta-awareness infused with positive affect. Decentering (“D”), attentional broadening (“A”), reappraisal (“R”), and savoring (“S”) are all metacognitive self-regulatory processes that involve monitoring of cognitive, affective, and sensory-perceptual experience. The MMT proposes that each iteration of this cycle fosters psychological distance from self-referential appraisals, helping the mindfulness practitioner to “get over himself/herself” – thereby shifting focus from egocentric processing to allocentric focus on the structural coupling between self and world. Attending to sensorimotor and social-affiliative coupling between self and pleasant non-self objects (e.g., a beautiful sunset, a lover’s smile or touch) induces experiences of natural reward that can be magnified through savoring. This cycle, when repeatedly activated, is theorized in the MMT to build an upward spiral that stimulates a gradient of self-transcendence extending from decentered meta-awareness of mental objects to blissful, absorptive experiences of oneness between subject and object, and finally, to transitory nondual states in which the subject-object dichotomy is completely transcended. With each iteration of this cycle, the MMT proposes that momentary states of meta-awareness and self-transcendent positive emotions accrue into a durable propensity towards dispositional mindfulness, selfless happiness, and the sense of meaning in life.

Funding: This work was supported by grant numbers R01DA042033 and R61AT009296 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to E.L.G.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Declarations of Interest: None.

References

- [1].Maturana H, Varela F, The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding, Shambala, Boston, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fredrickson BL, The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol Sci 359 (2004) 1367–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Garland EL, Fredrickson BL, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL, Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology, Clin. Psychol. Rev 30 (2010) 849–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Garland EL, The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping, Complement. Health Pract. Rev 12 (2007) 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Park J, The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal, Explore NY. 5 (2009) 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Deikman AJ, Deautomatization and the mystic experience, Psychiatry. 29 (1966) 324–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bernstein A, Hadash Y, Lichtash Y, Tanay G, Shepherd K, Fresco DM, Decentering and Related Constructs: A Critical Review and Metacognitive Processes Model, Perspect. Psychol. Sci 10 (2015) 599–617. doi: 10.1177/1745691615594577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ, Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation, Trends Cogn Sci. 12 (2008) 163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hodgins HS, Adair KC, Attentional processes and meditation, Conscious. Cogn 19 (2010) 872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vago DR, Zeidan F, The brain on silent: mind wandering, mindful awareness, and states of mental tranquility, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1373 (2016) 96–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Garland EL, Farb NA, Goldin PR, Fredrickson BL, Mindfulness Broadens Awareness and Builds Eudaimonic Meaning: A Process Model of Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation, Psychol. Inq 26 (2015) 293–314. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garland EL, Farb NA, Goldin PR, Fredrickson BL, The Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory: Extensions, Applications, and Challenges at the Attention–Appraisal–Emotion Interface, Psychol. Inq 26 (2015) 377–387. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1092493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Goldin PR, Morrison A, Jazaieri H, Brozovich F, Heimberg R, Gross JJ, Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial., J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 84 (2016) 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Garland EL, Hanley AW, Goldin PR, Gross JJ, Testing the mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Evidence for mindful positive emotion regulation from a reanalysis of longitudinal data, PLOS ONE 12 (2017) e0187727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Case A, Deaton A, Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 112 (2015) 15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dorjee D, Defining Contemplative Science: The Metacognitive Self-Regulatory Capacity of the Mind, Context of Meditation Practice and Modes of Existential Awareness, Front. Psychol 7 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5112249/(accessed August 7, 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dambrun M, Ricard M, Self-centeredness and selflessness: A theory of self-based psychological functioning and its consequences for happiness., Rev. Gen. Psychol 15 (2011) 138. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garland EL, Restructuring reward processing with Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement: novel therapeutic mechanisms to remediate hedonic dysregulation in addiction, stress, and pain, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1373 (2016) 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wadlinger HA, Isaacowitz DM, Positive mood broadens visual attention to positive stimuli, Motiv. Emot 30 (2006) 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cabanac M, On the origin of consciousness, a postulate and its corollary, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 20 (1996) 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Frijda NH, Sundararajan L, Emotion refinement: A theory inspired by Chinese poetics, Perspect. Psychol. Sci 2 (2007) 227–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Leyland A, Rowse G, Emerson L-M, Experimental effects of mindfulness inductions on self-regulation: Systematic review and meta-analysis., Emotion (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Garland EL, Baker AK, Howard MO, Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement reduces opioid attentional bias among prescription opioid-treated chronic pain patients, J. Soc. Soc. Work Res (2017) 000–000. doi: 10.1086/694324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ortner CNM, Kilner SJ, Zelazo PD, Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task, Motiv. Emot 31 (2007) 271–283. doi: 10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Garcia-Martin E, Ruiz-de-Gopegui E, Otin S, Blasco A, Larrosa JM, Polo V, Pablo LE, Demarzo MMP, Garcia-Campayo J, Assessment of Visual Function and Structural Retinal Changes in Zen Meditators: Potential Effect of Mindfulness on Visual Ability, Mindfulness. 7 (2016) 979–987. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0537-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Egan RP, Hill KE, Foti D, Differential effects of state and trait mindfulness on the late positive potential, Emotion. (2017) No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1037/emo0000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Arch JJ, Brown KW, Goodman RJ, Della Porta MD, Kiken LG, Tillman S, Enjoying food without caloric cost: The impact of brief mindfulness on laboratory eating outcomes, Behav. Res. Ther 79 (2016) 23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kiken LG, Lundberg KB, Fredrickson BL, Being present and enjoying it: Dispositional mindfulness and savoring the moment are distinct, interactive predictors of positive emotions and psychological health, Mindfulness. 8 (2017) 1280–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lindsay EK, Chinb B, Grecoa CM, Youngc S, Brownd KW, Wrighta AG, Smythe JM, Burketta D, Creswellb JD, How mindfulness training promotes positive emotions: Dismantling monitoring and acceptance in two randomized controlled trials, J. Pers. Soc. Psychol (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Major BC, Le Nguyen KD, Lundberg KB, Fredrickson BL, Well-Being Correlates of Perceived Positivity Resonance: Evidence From Trait and Episode-Level Assessments,Well-Being Correlates of Perceived Positivity Resonance: Evidence From Trait and Episode-Level Assessments, Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull (2018) 0146167218771324. doi: 10.1177/0146167218771324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yaden DB, Haidt J, Hood RW Jr., Vago DR, Newberg AB, The varieties of self-transcendent experience, Rev. Gen. Psychol 21 (2017) 143–160. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hanley AW, Nakamura Y, Garland EL, The Nondual Awareness Dimensional Assessment (NADA): New tools to assess nondual traits and states of consciousness occurring within and beyond the context of meditation, Psychol. Assess (2018). doi: 10.1037/pas0000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Josipovic Z, Neural correlates of nondual awareness in meditation, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1307 (2014) 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dunne J, Toward an understanding of non-dual mindfulness, Contemp. Buddhism 12 (2011) 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Northoff G, Hayes DJ, Is our self nothing but reward?, Biol. Psychiatry 69 (2011) 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bhikkhu Ñ, Anupada-sutta MN 111. trans. Middle-Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhīma Nikāya, Wisdom Publications, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hagerty MR, Isaacs J, Brasington L, Shupe L, Fetz EE, Cramer SC, Case Study of Ecstatic Meditation: fMRI and EEG Evidence of Self-Stimulating a Reward System, Neural Plast 2013(2013). doi: 10.1155/2013/653572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fort AO, Beyond pleasure: Śankara on bliss, J. Indian Philos. 16 (1988) 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kilty G, A Lamp to Illuminate the Five Stages, Wisdom Publications, Somerville, MA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Austin JH, Zen and the brain: Toward an understanding of meditation and consciousness, MIT Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Froeliger B, Garland EL, Kozink RV, Modlin LA, Chen N-K, McClernon FJ, Greeson JM, Sobin P, Meditation-state functional connectivity (msfc): strengthening of the dorsal attention network and beyond, Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med 2012 (2012). http://www.hindawi.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/journals/ecam/aip/680407/ (accessed May 20, 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Garland EL, Hanley AW, Riquino MR, Priddy SE, Baker AK, Wheeler KS, Yack B, Bedford CE, Bryan MA, Atchley RM, Nakamura Y, Froeliger BE, Howard MO, Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement reduces risk of prescription opioid misuse among chronic pain patients by promoting positive psychological processes: Mechanistic analyses of proximal outcome data from a stage 2 RCT, Manuscr. Submitt. Publ (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [43].Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO, Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial., J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 82 (2014) 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Garland EL, Froeliger B, Zeidan F, Partin K, Howard MO, The downward spiral of chronic pain, prescription opioid misuse, and addiction: Cognitive, affective, and neuropsychopharmacologic pathways, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 37 (2013) 2597–2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shurman J, Koob GF, Gutstein HB, Opioids, pain, the brain, and hyperkatifeia: a framework for the rational use of opioids for pain, Pain Med. Malden Mass 11 (2010) 1092–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Garland EL, Bryan CJ, Finan PH, Thomas EA, Priddy SE, Riquino MR, Howard MO, Pain, hedonic regulation, and opioid misuse: Modulation of momentary experience by Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement in opioid-treated chronic pain patients, Drug Alcohol Depend. 173 (2017) S65–S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO, Effects of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement on reward responsiveness and opioid cue-reactivity, Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 231 (2014) 3229–3238. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3504-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO, Neurophysiological evidence for remediation of reward processing deficits in chronic pain and opioid misuse following treatment with Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement: exploratory ERP findings from a pilot RCT, J. Behav. Med 38 (2015) 327–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Garland EL, Howard MO, Zubieta J-K, Froeliger B, Restructuring hedonic dysregulation in chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: effects of mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement on responsiveness to drug cues and natural rewards, Psychother. Psychosom 86 (2017) 111–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zeidan F, Vago DR, Mindfulness meditation–based pain relief: a mechanistic account, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1373 (2016) 114–127. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Palsson O, Faurot K, Mann JD, Whitehead WE, Therapeutic mechanisms of a mindfulness-based treatment for IBS: effects on visceral sensitivity, catastrophizing, and affective processing of pain sensations, J. Behav. Med 35 (2012) 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Finan PH, Garland EL, The role of positive affect in pain and its treatment, Clin. J. Pain 31 (2015) 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Froeliger B, Mathew AR, McConnell PA, Eichberg C, Saladin ME, Carpenter MJ, Garland EL, Restructuring reward mechanisms in nicotine addiction: A pilot fMRI study of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for cigarette smokers, Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med 2017 (2017) e7018014. doi: 10.1155/2017/7018014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jinpa T, Gyalchok S, Gyaltsen K, Mind training: The great collection, Simon and Schuster, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chogyam T, Shambala, The Sacred Path of the Warrior, London: Shambhala Publications Train to Win, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vago DR, Silbersweig DA, Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness, Front. Hum. Neurosci 6 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480633/ (accessed October 8, 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Watts A, Psychotherapy East & West, Random House, New York, 1961. [Google Scholar]