Key Points

Question

Are adults who were born preterm or with low birth weight less likely to experience social transitions normative of adulthood, such as romantic partnerships, sexual intercourse, or parenthood?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies describing up to 4.4 million participants, adults who were born preterm or with low birth weight were less likely to experience a romantic partnership, sexual intercourse, or parenthood than their peers who were born full-term. The likelihood of experiencing these social transitions decreased with lower gestational age and birth weight, and was similar in both young and middle adulthood.

Meaning

The findings suggest that adults who were born preterm or with low birth weight are less likely to have sexual or partner relationships than adults born full-term, which might put them at increased risk of decreased well-being and poorer physical and mental health.

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the association between preterm birth or low birth weight and social relationships in adulthood.

Abstract

Importance

Social relationships are important determinants of well-being, health, and quality of life. There are conflicting findings regarding the association between preterm birth or low birth weight and experiences of social relationships in adulthood.

Objective

To systematically investigate the association between preterm birth or low birth weight and social outcomes in adulthood.

Data Sources

PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Embase were searched for peer-reviewed articles published through August 5, 2018.

Study Selection

Prospective longitudinal and registry studies reporting on selected social outcomes in adults who were born preterm or with low birth weight (mean sample age ≥18 years) compared with control individuals born at term.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The meta-analysis followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The data were collected and extracted by 2 independent reviewers. Pooled analyses were based on odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals and Hedges g, which were meta-analyzed using random-effects models.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Ever being in a romantic partnership, ever having experienced sexual intercourse, parenthood, quality of romantic relationship, and peer social support.

Results

Twenty-one studies were included of the 1829 articles screened. Summary data describing a maximum of 4 423 798 adult participants (179 724 preterm or low birth weight) were analyzed. Adults born preterm or with low birth weight were less likely to have ever experienced a romantic partnership (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81), to have had sexual intercourse (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.31-0.61), or to have become parents (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.65-0.91) than adults born full-term. A dose-response association according to degree of prematurity was found for romantic partnership and parenthood. Overall, effect sizes did not differ with age and sex. When adults born preterm or with low birth weight were in a romantic partnership or had friends, the quality of these relationships was not poorer compared with adults born full-term.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that adults born preterm or with low birth weight are less likely to experience a romantic partnership, sexual intercourse, or to become parents. However, preterm birth or low birth weight does not seem to impair the quality of relationships with partners and friends. Lack of sexual or partner relationships might increase the risk of decreased well-being and poorer physical and mental health.

Introduction

Preterm birth or low birth weight (PT/LBW) is associated with an increased risk for disability,1,2 neurocognitive impairment,3,4,5,6 learning difficulties,3,6 and mental health problems,7,8,9 with the association being stronger for those with lower gestational age.3,10,11,12 These functional deficits are associated with adverse impacts on preterm-born adults’ socioeconomic outcomes.13 However, little is known about whether those born preterm master social transitions into adulthood, such as building a supportive peer group, establishing romantic partnerships, having sexual intercourse, or becoming a parent.

Close, intimate, and supportive relationships are associated with increased happiness and well-being,14,15 good physical health,16 and good mental health.17 Studies have shown that social relationships are more challenging for children born PT/LBW.18 Indeed, prematurity has been associated with a behavioral phenotype18,19,20 and personality profile21,22,23,24 that includes being timid, socially withdrawn, overcontrolling, and disinclined toward risk-taking or fun seeking. These differences may predispose PT/LBW individuals to face greater difficulties in establishing romantic and peer relationships.

In contrast, research on social outcomes of adults born preterm is not conclusive. While Scandinavian registry studies have found that adults born PT/LBW were less likely to ever be in a registered partnership11,12,25 or to be parents,12,25 prospective studies have reported conflicting findings across26,27,28 and within2,29 studies. Regarding the latter, a Canadian cohort study2,29 of extremely low-birth-weight infants reported different findings for social outcomes at distinct time points: while no differences were found in rates of marriage or cohabitation and parenthood between the extremely low-birth-weight individuals and those born full term at ages 22 to 26 years,29 adults with extremely low birth weight were less likely to be married or cohabitating and to have had children during the fourth decade of life.2 Additionally, there is a lack of research that has analyzed the impact of preterm birth on the quality of close relationships, such as with partners2,30,31 and friends.2,30,32,33,34

Hence, there are inconsistent and scarce findings about the social lives of PT/LBW adults. This systematic review and meta-analysis systematically investigates the association between being born PT/LBW and social outcomes in adulthood, such as ever being in a romantic partnership, ever having had sexual intercourse, parenthood, quality of romantic relationship, and peer social support. Furthermore, we investigate whether there is a dose-response association according to degree of prematurity and whether outcomes are moderated by type of study (ie, cohort or registry), age, or sex.

Methods

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline35 and was registered with PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO identifier: CRD42017078286).

Search Strategy

A systematic search for articles published in the electronic databases PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Embase was performed from inception through August 5, 2018, for publications in English. The following keywords were used: (preterm* OR “low birth weight”) AND (partner* OR roman* OR marri* OR sexual* OR reprod* OR fertility OR intercourse OR parent* OR social* OR peer OR friend*) AND (adult*).

Study Selection Criteria

Studies were eligible for review according to the following criteria: (1) the sample included individuals who were born PT (<37 weeks’ gestation) or LBW (<2500 g at birth); (2) term control group; (3) adult participants (ie, mean sample age ≥18 years); (4) measured at least 1 of the following social outcomes in adulthood: romantic partnership (eg, dating, cohabitation, marriage), quality of romantic relationship (eg, satisfaction, intimacy), sexual intercourse (ie, if ever experienced sexual intercourse), parenthood (ie, if any live biological child), or social support (ie, positive and supportive relationships with friends); and (5) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal. If data from the same sample were published in multiple works for the same social outcome, we retained (1) the study with the longest follow-up interval (ie, oldest age at assessment); and (2) the study with the largest sample size and the broadest concept coverage.

Data Collection Process

Two of us (M.M. and A.B.) reviewed titles and abstracts of traced articles. The title and abstract screening was followed by the analyses of full texts to check inclusion criteria. Discordances were resolved by discussion among all authors. When reported information was unclear or numerical data were not obtainable, relevant corresponding authors were contacted for clarification.

Data Extraction

Studies reporting on PT or LBW were grouped into the same category because infants with low birth weight are mostly born preterm.36 When information was available, we used 4 different gestational age subgroups: extremely preterm (EPT; <28 weeks or <1000 g), very preterm (VPT; 28-31 weeks or 1000-1500 g), moderate-to-late preterm (MLPT; 32-36 weeks or 1500-2500 g), and full-term (FT; >36 weeks or >2500 g). When studies referred to preterm birth without mentioning gestational weeks, data were included in the MLPT subgroup.

A standardized form was used to extract data from each study that included publication details, country, characteristics of participants (year of birth, sample size, gestational age or birth weight, percentages of men, and age), type of study (ie, cohort or registry), type of social outcome, and outcome data (ie, means and standard deviations or numbers and frequencies)37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63 (Table 1). The extraction was conducted independently by 2 of us (M.M. and A.B.) and information was cross-checked for consistency. When inconsistencies emerged information was checked in the original study.

Table 1. Summary of the Studies Included in the Meta-analysis of Social Outcomes in Adulthood After Preterm Birth/Low Birth Weight .

| Source | Country | Year of Birth | Participants, No. | Male, No. (%) | Age Outcome, y | Degree of PT/LBW | Registry or Cohort (Name) | Social Outcomes | Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | FT | PT | FT | ||||||||

| Båtsvik et al,57 2015 | Norway | 1982-1985 | 37 | 46 | 19 (51.4) | 25 (54.4) | 24 | EPT | Cohort | Partnership | Marriage or cohabitation |

| Cooke,26 2004 | United Kingdom | 1980-1983 | 79 | 71 | 35 (44.3) | 30 (42.3) | 19-22 | PT | Cohort | Partnership; sexual intercourse, parenthood | Ever in relationship |

| Dalziel et al,58 2007 | New Zealand | 1969-1974 | 126 | 66 | 66 (52.3) | 33 (50) | 31 | PT | Cohort (Auckland Steroid Trial) | Partnership | Marriage or cohabitation |

| Darlow et al,43 2013 | New Zealand | 1986 | 230 | 69 | 104 (45.2) | 33 (47.8) | 22-23 | VLBW | Cohort | Sexual intercourse | NA |

| D’Onofrio et al,11 2013 | Sweden | 1973-2008 | 154 322 | 3 146 386 | 85 195 (55.2) | 1 618 442 (51.4) | ≤38 | EPT, VPT, and MLPT | Registry | Partnership; parenthood | Ever partnered |

| Drukker et al,59 2018 | Israel | 1982-1997 | 4005 | 53 906 | 1788 (45) | 26 825 (49) | NA | VPT and MLPT | Cohort | Parenthood | NA |

| Hack et al,60 2002 | United States | 1977-1979 | 242 | 233 | 116 (48) | 108 (46) | 20 | VLBW | Cohort | Sexual intercourse; parenthood | NA |

| Hallin et al,32 2010 | Sweden | 1985-1986 | 51 | 52 | 19 (37.3) | 23 (42.6) | 18 | EPT | Cohort | Peer social support | Adaptive functioning for friends (adult self-report) |

| Hille et al,23 2008 | Netherlands | 1983 | 656 | 418 | 294 (44.8) | 220 (52.6) | 19 | VPT | Cohort (POPS Study and Dutch general population) | Partnership; sexual intercourse | In relationship |

| Husby et al,33 2016 | Norway | 1986-1988 | 35 | 37 | 14 (40) | 15 (40.5) | 23 | VLBW | Cohort (University Hospital Trondheim) | Peer social support | Adaptive functioning for friends (adult self-report) |

| Jaekel, et al,9 2017 | Germany | 1985-1986 | 200 | 197 | 106 (53) | 94 (47.7) | 26 | VPT or VLBW | Cohort (Bavarian Longitudinal Study) | Partnership; sexual intercourse | In relationship |

| Kajantie et al,28 2008 | Finland | 1978-1985 | 162 | 188 | 68 (42) | 75 (39.9) | 22.3 | VLBW | Cohort (Helsinki Study of Very Low Birth Weight Adults) | Partnership; sexual intercourse; parenthood | Ever partnered |

| Kroll et al,61 2017 | United Kingdom | 1979-1984 | 122 | 89 | 76 (62) | 42 (47) | 28-34 | VPT | Cohort | Partnership; parenthood | In relationship |

| Männistö et al,62 2015a | Finland | 1985-1989 | 397 | 356 | 189 (47.6) | 170 (47.8) | 23.2 | MLPT | Cohort (ESTER) | Partnership; sexual intercourse; parenthood | Ever partnered |

| Mathiasen et al,25 2009 | Denmark | 1974-1976 | 1422 | 192 233 | 736 (51.8) | 98 240 (51.1) | 27-29 | VPT | Registry | Partnership; parenthood | In relationship |

| Moster, et al,12 2008 | Norway | 1967-1983 | 39 465 | 828 227 | 21 715 (55) | 421 568 (50.9) | 20-36 | EPT, VPT, and MLPT | Registry | Partnership; parenthood | Marriage or cohabitation |

| Odberg et al,34 2011 | Norway | 1986-1988 | 134 | 135 | 61 (54) | 64 (53) | 19 | LBW (<2000 g) | Cohort | Partnership; peer social support | In relationship; self-reported quality of the social network |

| Roberts, et al,63 2013 | Australia | 1991-1992 | 194 | 148 | 84 (45.2) | 60 (43.5) | 18 | EPT or ELBW | Cohort (Victorian Infant Collaborative Study) | Sexual intercourse | NA |

| Saigal et al,2 2016a | Canada | 1977-1982 | 100 | 89 | 39 (39.0) | 33 (37.1) | 32.3 | ELBW | Cohort (McMaster ELBW Cohort) | Partnership; quality of romantic relationship; sexual intercourse; parenthood; peer social support | Marriage or cohabitation; satisfaction with partner; Young Adult Social Support Index |

| Scharf et al,30 2013 | Israel | NA | 57 | 57 | NA | NA | 26.6 | PT | Cohort | Quality of romantic relationship; peer social support | Intimacy in relationship; emotional closeness |

| Winstanley et al,31 2015 | United Kingdom | NA | 11 592 | 51 460 | 3554 (30.7) | 8038 (69.3) | 31.4 | PT | Cohort | Partnership; parenthood; quality of romantic relationship | Marriage or cohabitation; satisfaction with partner |

Abbreviations: ELBW, extremely low birth weight (<1000 g); EPT, extremely preterm (<28 weeks’ gestation), FT, full term; LBW, low birth weight (<2500 g); MLPT, moderate-to-late preterm (32-36 weeks’ gestation); NA, not available; PT, preterm; VLBW, very low birth weight (1000-1500 g); VPT, very preterm (28-31 weeks’ gestation).

This study reported on an early preterm (<34 weeks’ gestation) subgroup overlapping with MLPT subgroup. We excluded this subsample of less than 34 weeks’ gestation from the analysis.

Quality Assessment

Study quality was assessed independently by 2 of us (M.M. and A.B.) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale37 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Scores could range from 0 to 9. The mean (range) of ratings for study quality was 7.3 (4-9), indicating overall good quality.

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis of the overall comparison between adults born PT/LBW and their FT peers was carried out with Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 2 software (Biostat)38 for each social outcome. We used pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals for studies presenting dichotomous outcomes (eg, frequencies) and Hedges g for studies presenting continuous outcomes (eg, means and standard deviations) with random effects. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed with Cochran Q (P value), Higgins I2, and τ2. Low heterogeneity was defined as an I2 value of 0% to 25%, moderate heterogeneity as an I2 of 25% to 75%, and high heterogeneity as an I2 of 75% to 100%. To explore heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses (dependent on data availability) for degree of prematurity (ie, EPT, VPT, MLPT), type of study (ie, cohort or registry), age groups (ie, young adulthood [18-25 years] or middle adulthood [≥26 years]), and sex.

Publication bias analysis was assessed through (1) the trim and fill procedure to examine the symmetry of effect sizes plotted by the inverse of the standard error39 (ideally, effect sizes should mirror one another on either side of the mean); (2) the Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation test to examine the likelihood of bias in favor of small sample size studies,40 in which nonsignificance of correlation indicates no publication bias; and (3) Egger test to examine whether publication bias was related to the direction of study findings.41 The intercept value provided by this test shows the level of funnel plot asymmetry from the standard precision.

Because PT and LBW were combined into 1 group, it is essential to prove that the findings of the meta-analysis are not dependent on this decision. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken in which we repeated the analysis excluding the studies that reported on LBW only.

Results

Study Characteristics

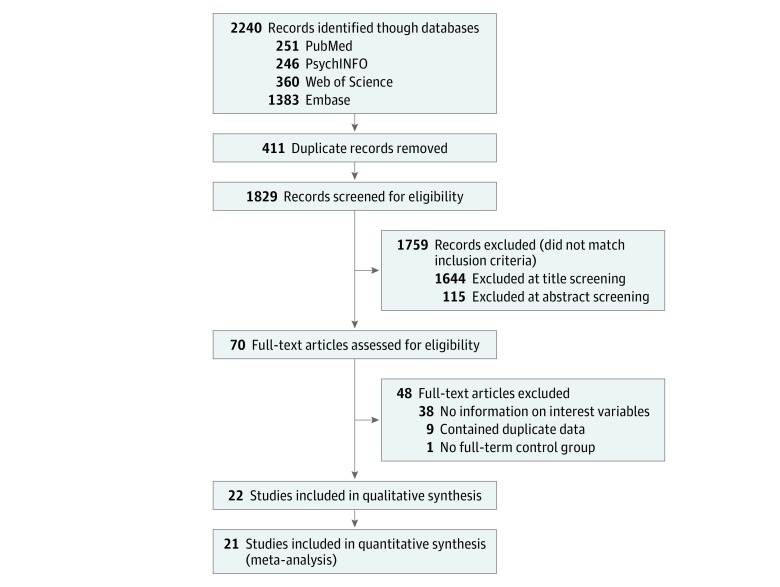

Of 1829 articles screened, 21 studies were eligible for quantitative analysis (Figure 1). According to our selection criteria, it was possible to identify 14 studies for romantic partnership, 9 for sexual intercourse, 11 for parenthood, 3 for quality of romantic relationship, and 5 for peer social support. We also identified 5 studies for number of friends,32,33,34,42,43 but they were not included in the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) owing to the different ways the number of friends was assessed across studies. The studies included in the meta-analysis were conducted in 12 countries (Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Israel, Canada, United States, New Zealand, and Australia). The number of participants included in each analysis of summary data ranged from 4 423 798 (179 724 PT/LBW) for parenthood to 648 (276 PT/LBW) for peer social support (Table 2). Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean percentage of occurrence of each social transition across the studies is shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis Flow Diagram.

One study included in the qualitative synthesis was excluded from meta-analysis because it reported only on number of friends.

Table 2. Number of Participants Included in Meta-analysis.

| Social Outcome | Total No. | No. Analyzed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Participants | Degree of Prematurity | Type of Study | Age Group | Sex | |

| Romantic partnership | 14 | 4 367 489 (176 632 PT) | 6244 EPT; 13 606 VPT; 156 782 MLPT | Cohort = 66 566 (13 456 PT); registries = 4 300 923 (163 176 PT) | 18-25 y = 2531 (1326 PT); ≥26 y = 356 824 (175 304 PT) | 793 Male (435 PT); 967 female (559 PT) |

| Sexual intercourse | 9 | 3730 (2029 PT) | 286 EPT; 1420 VPT; 323 MLPT | NA | 18-25 y = 3147 (1732 PT); ≥26 y = 583 (297 PT) | 1023 Male (551 PT); 1214 female (685 PT) |

| Parenthood | 11 | 4 423 798 (179 724 PT) | 6207 EPT; 13 369 VPT; 160 148 MLPT | Cohort = 122 952 (16 560 PT); registries = 4 300 917 (163 164 PT) | 18-25 y = 1589 (741 PT); ≥26 y = 4 364 369 (174 978 PT) | 34 531 Male (2045 PT); 33 101 female (2540 PT) |

| Quality of romantic relationship | 3 | 63 238 (11 688 PT) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Peer social support | 5 | 648 (276 PT) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: EPT, extremely preterm (<28 weeks’ gestation); MLPT, moderate-to-late preterm (32-36 weeks’ gestation); NA, not analyzed; PT, preterm, VPT, very preterm (28-31 weeks’ gestation).

Differences in Social Outcomes Between Adults Born PT/LBW and FT

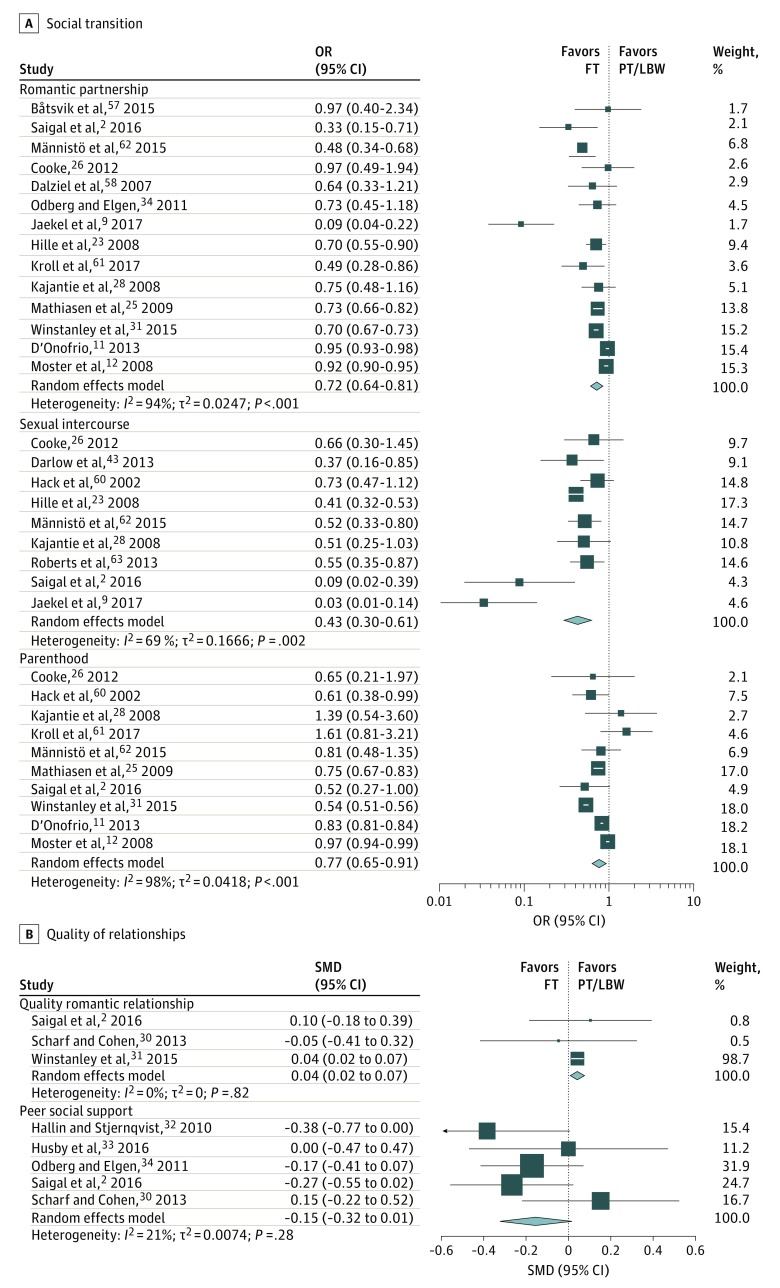

Meta-analysis results (Table 3 and Figure 2) revealed that PT adults were less likely to have ever been involved in a romantic partnership than those born FT (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81). Heterogeneity analysis indicated high variation in effects between studies. Subgroup analysis according to the degree of prematurity revealed a dose-response association of degree of prematurity and romantic partnership (Q = 26.35; P < .001) with the EPT subgroup being the least likely to have ever been in a romantic partnership (OR for EPT, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.24-0.50; OR for VPT, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.55-0.82; and OR for MLPT, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65-0.96). Comparisons of type of study (Table 3) indicated that in both cohort and registry studies PT birth was associated with decreased likelihood of romantic partnership when compared with individuals born FT, but this effect was stronger in cohort studies. In both age groups, PT/LBW were less likely to experience a romantic partnership. Finally, subgroup analysis for sex revealed that both men and women born PT/LBW were less likely to ever be involved in a romantic partnership than their same-sex FT counterpart.

Table 3. Associations Between Preterm or Low Birth Weight and Social Outcomes.

| Social Outcome | Data Points, No. | Hedges g or OR (95% CI) | Cochran Q | Test for Heterogeneity, P Value | τ2 | I2, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romantic Partnership | ||||||

| All studies | 14 | 0.72 (0.57-0.77)a | 234.39 | <.001 | 0.02 | 94.45 (92.2-96.05) |

| Degree of prematurityb | ||||||

| MLPT (32-36 wk GA) | 7 | 0.79 (0.65-0.96)a | 256.61 | <.001 | 0.03 | 97.62 (96.58-98.40) |

| VPT (28-31 wk GA) | 7 | 0.64 (0.48-0.77)a | 31.25 | <.001 | 0.04 | 80.80 (61.2-90.51) |

| EPT (<28 wk GA) | 4 | 0.33 (0.24-0.50)a | 23.76 | <.001 | 0.39 | 87.38 (69.84-94.71) |

| Study type | ||||||

| Cohort | 11 | 0.65 (0.57-0.73)a | 20.13 | <.001 | 0.07 | 68.77 (41.53-83.29) |

| Registry | 3 | 0.88 (0.80-0.97)a | 24.01 | <.001 | 0.004 | 91.67 (78.74-96.74) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18-25 y | 6 | 0.69 (0.54-0.90)a | 5.79 | .33 | 0.008 | 13.61 (0-38.26) |

| ≥26 y | 8 | 0.73 (0.53-0.78)a | 217.18 | <.001 | 0.02 | 96.77 (95.32-97.82) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 4 | 0.62 (0.45-0.86)a | 4.38 | .22 | 0.14 | 31.52 (0-75.42) |

| Women | 4 | 0.71 (0.53-0.95)a | 2.25 | .52 | 0 | 0 (0-95) |

| Sexual Intercourse | ||||||

| All studies | 9 | 0.43 (0.31-0.61)a | 24.81 | .002 | 0.16 | 69 (35.10-83.9) |

| Degree of prematurity | ||||||

| MLPT (32-36 wk GA) | 2 | 0.55 (0.25-1.33)a | 0.28 | .60 | 0 | 0 |

| VPT (<32 wk GA) | 5 | 0.37 (0.22-0.66)a | 18.32 | .01 | 0.28 | 78.16 (47.61-90.9) |

| EPT | 2 | 0.32 (0.13-0.87)a | 5.37 | .02 | 1.37 | 81.41 (20.87-95.62) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18-25 y | 7 | 0.50 (0.42-0.59)a | 6.35 | .38 | 0.003 | 5.54 (0-72.4) |

| ≥26 y | 2 | 0.05 (0.02-0.15)a | 0.86 | .35 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 5 | 0.49 (0.32-0.78)a | 9.98 | .04 | 0.22 | 59.98 (0-85.01) |

| Women | 5 | 0.45 (0.29-0.69)a | 3.71 | .45 | 0 | 0 (0-65.23) |

| Parenthood | ||||||

| All studies | 11 | 0.78 (0.67-0.90)a | 555.98 | <.001 | 0.04 | 98.20 (97.64-98.63) |

| Degree of prematurityc | ||||||

| MLPT (32-36 wk GA) | 5 | 0.79 (0.65-0.96)a | 562.88 | <.001 | 0.05 | 99.11 (98.8-99.34) |

| VPT (28-31 wk GA) | 6 | 0.67 (0.55-0.82)a | 65.83 | <.001 | 0.07 | 90.11 (83.79-94.87) |

| EPT (<28 wk GA) | 3 | 0.31 (0.23-0.42)a | 55.26 | <.001 | 0.57 | 96.38 (92.41-97.46) |

| Study type | ||||||

| Cohort | 8 | 0.71 (0.60-0.85)a | 182.58 | <.001 | 0.09 | 96.16 (94.21-97.46) |

| Registry | 3 | 0.85 (0.71-1.01)a | 131.92 | <.001 | 0.01 | 98.49 (97.33-99.14) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18-25 y | 4 | 0.76 (0.55-1.31)a | 2.43 | .48 | 0 | 0 (0-98) |

| ≥26 y | 6 | 0.76 (0.64-0.93)a | 552.86 | <.001 | 0.12 | 99.06 (98.77-99.33) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 5 | 0.63 (0.36-1.09)a | 1.68 | .79 | 1.02 | 0 (0-23.21) |

| Women | 5 | 0.65 (0.41-1.04)a | 10.88 | .02 | 0 | 63.07 (0-88.14) |

| Quality of Romantic Relationship | ||||||

| All studies | 3 | 0.04 (0.02-0.07)c | 0.41 | .81 | 0 | 0 (0-83.64) |

| Peer Social Support | ||||||

| All studies | 5 | −0.15 (−0.32 to 0.01)c | 5.10 | .28 | 0.008 | 21.63 (0-74.70) |

Abbreviations: EPT, extremely preterm; GA, gestational age; MLPT, moderate-to-late preterm; OR, odds ratio; VPT, very preterm.

Values are odds ratios.

The number of data points are higher in the degree of prematurity analysis since some studies reported on more than 1 degree of prematurity.

Values are Hedges g.

Figure 2. Forest Plots for Social Outcomes of Adults Born Preterm or With Low Birth Weight (PT/LBW) Compared With Adults Born Full-term (FT).

Odds ratio (OR) or standardized mean difference (SMD) for individual studies are indicated by squares and 95% CIs by horizontal lines. Pooled estimates and their 95% CIs are represented by diamonds. The size of the squares and the diamonds are proportional to the weight assigned to the relative effect sizes. The arrow for the study of Hallin and Stjernqvist32 indicates that the 95% CI exceeds the limit for the effect size range.

Being born PT/LBW was associated with being less likely to ever have experienced sexual intercourse (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.31-0.61) (Table 3). Heterogeneity analysis indicated high variation in sexual activity effects between studies. Subgroup analysis for degree of prematurity revealed that both the EPT and VPT subgroups were less likely to ever have had sexual intercourse than the FT adults; however, adults born MLPT did not differ from FT. In both age groups, PT/LBW were less likely to ever have had sexual intercourse than FT individuals, and this association was stronger for the older age group (OR for 18-25 years, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.42-0.59 and OR for ≥26 years, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.02-0.15). Subgroup analysis for sex revealed that both men and women born PT/LBW were less likely to have experienced sexual intercourse than their same-sex counterparts born FT.

There was also a significant association between PT/LBW and parenthood, with adults born PT/LBW less likely to be parents than FT adults (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.65-0.91). Heterogeneity analysis indicated significant variation in parenthood effects between studies. Subgroup analysis for degree of prematurity revealed a dose-response association of degree of prematurity and parenthood (Q = 22.30; P < .001), with the EPT subgroup being the least likely to have become a parent (OR for EPT, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.23-0.42; OR for VPT, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.55-0.82; and OR for MLPT, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65-0.96). When comparing the type of study, PT adults were less often reported to be parents in cohort studies, but not in registry studies. Subgroup analysis for age groups revealed no differences between PT/LBW and FT individuals in the younger age group, but PT/LBW adults in the older age group were less likely to be parents compared with FT adults of the same age. No moderation effect was found for sex.

Significant differences between PT and FT adults were found for the quality of romantic relationship (Table 3 and Figure 2). Adults born PT/LBW perceived the relationship with their partner as significantly more satisfying or intimate than those born FT. Heterogeneity was not significant for this variable. Furthermore, we observed no significant differences between PT/LBW and FT adults regarding the peer social support.

Publication Bias

Under the random-effects model, the point estimate for the combined studies was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.67 to 0.73) for romantic partnership, 0.04 (95% CI, 0.02 to 0.07) for quality of romantic relationship, 0.54 (95% CI, 0.39 to 0.74) for ever having experienced sexual intercourse, 0.78 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.93) for parenthood, and 0.15 (95% CI, −0.32 to 0.01) for peer social support. With the use of trim and fill, these values remained unchanged for all relational outcomes, indicating no publication bias. The Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation and Egger test were not statistically significant for all outcomes, indicating no evidence of publication bias.

Sensitivity Analysis

Results remained the same after excluding studies that reported only birth weight. Hence, PT adults were less likely to be in a partnership (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66-0.85), to have ever had sexual intercourse (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31-0.76), and to be parents (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.97) in comparison with FT adults.

Discussion

Our findings revealed that adults born PT/LBW are less likely to experience romantic partnerships, sexual intercourse, or parenthood. Nevertheless, when they were in a romantic partnership or had friends, the quality of these relationships was similar to those experienced by FT adults.

Using summary data from prospective studies with more than 4 million participants provided evidence for a temporal association between being born PT/LBW and establishing social transitions into adulthood, here defined as romantic partnership, sexual intercourse, and parenthood. The associations were robust across degree of prematurity, age groups, and sex. These findings are consistent with the increasing recognition of the impact that early life influences have on outcomes in adulthood.13,44,45 Furthermore, our findings are in line with evidence of a preterm behavior phenotype that follows into adulthood,21,22,24 which might be associated with more difficulty engaging in these transitions for individuals born PT/LBW.

We verified that the strength of the associations between PT/LBW and social transitions were in general small for romantic partnership and parenthood and moderate for sexual intercourse. The associations diverged depending on degree of prematurity, type of study, and age group. The subgroup analysis for degree of prematurity revealed that the likelihood of PT/LBW experiencing a romantic partnership, sexual intercourse, or parenthood decreased with lower gestational age. Indeed, a significant dose-response association was found between degree of prematurity and rates of romantic partnership and parenthood, with adults born EPT 67% less likely to be in a romantic partnership and 69% less likely to be parents than those born FT.

With respect to the type of study, we found that PT/LBW adults were less likely to have experienced romantic partnership or parenthood in cohort studies compared with registry studies. This difference may be related to the fact that cohort studies included mainly individuals born at less than 32 weeks’ gestational age, whereas registry studies included the full range of preterm birth, and the likelihood of occurrence of these transitions decreases with lower gestational ages.

It has been suggested that PT/LBW individuals might take longer to accomplish the milestones normative of adult life, such as employment, romantic partnership, and parenthood.28 The current findings do not support this hypothesis. We verified that the difference of experiencing these transitions in comparison with FT individuals did not alter in the older age group and, in some cases, it was even greater in the older age group. To illustrate, while at ages 18 to 25 years, individuals born PT/LBW were 50% less likely than those born FT to have ever experienced sexual intercourse, after the age of 25 years the decreased likelihood for PT/LBW went up to 95%. These findings may be cautiously interpreted, as only 2 studies2,9 could be included in the older age group for this analysis. Alternatively, we may speculate that new ways of dating, such as dating applications, may be used more often by the younger age group of PT/LBW individuals.46

Adults born PT/LBW were overall less likely than those born FT to be parents. However, this difference was not significant in the younger age group. This finding is in line with the findings of Saigal et al.2 A likely explanation is that, consistent with the general trend for first parenthood to take place in the late 20s or early 30s,47 few participants in the FT group were parents, yielding no difference between groups. However, once parenthood was assessed in middle adulthood, the differences between PT/LBW and FT groups emerged. At a societal or population level, it suggests that prematurity is associated with a cross-generational fertility loss. Adults born PT/LBW are less likely to become parents and their parents were already less likely to have subsequent children after their preterm child was born.48

Overall, rather than a delay, our findings suggest persistent difficulties in making these social transitions that have been associated with negative outcomes later in life,49,50 such as lower wealth, social isolation, and poorer physical and mental health. Both biological and environmental factors, such as alterations in the so-called social brain as part of the neurodevelopmental sequelae of preterm birth51 or parental stress in the early stages of life,52 have been found to contribute to social difficulties for PT/LBW individuals, such as being more timid and withdrawn. However, more investigation is required to shed light on the mechanisms through which biological and environmental factors interplay during PT/LBW individuals’ development. These findings highlight, on the one hand, the need for more prospective studies over the life course of PT/LBW individuals and the analysis of early predictors of social outcomes and, on the other hand, the importance of continued monitoring and adequate support of PT/LBW individuals throughout life.

With respect to sex, it was only possible to include 4 to 5 studies in these subgroup analyses. We verified that both men and women born PT/LBW were less likely to have experienced romantic partnerships or sexual intercourse than their counterparts born FT. No differences were found for parenthood; however, it is important to note that there were few participants with children in this subgroup analysis. Previous studies have not been consistent when analyzing the role of sex on social outcomes.2,26,28 Although it was possible to pool data from more than 1200 participants in these analyses, the lack of studies reporting on sex highlight the need for future research to clarify its moderating role.

We found that PT/LBW individuals perceived their romantic relationships slightly more positively than FT individuals, and that there was no difference for perceptions of peer social support between both groups. Although it was not possible to assess the amount of friends in this meta-analysis, most studies have found that PT/LBW adults had fewer friends42,43,53 than FT adults. In addition, studies on PT/LBW children and adolescents reported poorer-quality relationships with peers18,54 than those born FT, including being bullied by peers more often.55 Hence, our findings suggest that despite fewer close relationships, relationship quality was not poorer when PT/LBW adults had friends or a partner, or the quality of relationships in PT/LBW individuals improves into adulthood. Longitudinal studies are required to explore these alternative explanations.

Limitations

This comprehensive study of social outcomes of premature birth uses large sample sizes of PT/LBW individuals in comparison with FT individuals, particularly in the analysis of romantic partnership and parenthood. However, there are limitations for the other outcome measures—having ever experienced sexual intercourse, quality of romantic relationships, and peer social support—that included a smaller number of studies and PT/LBW participants. There are also considerable variations of how peer support and quality of romantic relationships were measured across studies. For example, quality of romantic relationships included studies reporting on satisfaction with partner and intimacy, and social support included studies reporting on emotional closeness with friends to self-reported quality of social network. We recommend individual studies use similar valid measures to make comparisons less problematic.

Furthermore, the degree of prematurity is associated with physical and mental health and cognitive development,11,12,13,45 and information on disability was not available for most studies. Thus, it could not be assessed whether functional deficits or disability moderated the association between PT/LBW and social outcomes. In this study, PT and LBW were treated as 1 factor. Although these constructs show high comorbidity and our sensitivity analyses revealed consistent results, it would be important to disentangle the effects of PT and LBW and their possible additive effects on social outcomes. This would involve considering data on birth weights appropriate for gestational age or small for gestational age, which most studies included in the meta-analyses did not report. Future research should address these limitations by conducting individual participant meta-analysis and obtaining data directly from the study authors.

The heterogeneity of studies was high, indicating considerable variation. This might arise from incorporating cohort and registry studies with various sample sizes. To address this possibility, we used a random-effects model in the analysis and conducted moderator analyses. Nevertheless, our moderator analysis explained only some of the heterogeneity. Thus, the findings from the current study should be interpreted with caution and analysis should be repeated when more adulthood data becomes available from the cohort studies. Also, only English publications were considered in this meta-analysis and, therefore, potential language bias should be taken into account.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides a qualitative and quantitative overview of the current state of knowledge concerning social outcomes in adults born PT/LBW. Pooling data from multiple cohort and registry studies provided evidence that fewer adults born PT/LBW experience romantic partnerships, sexual intercourse, or parenthood. These associations are stronger the lower the gestational age and were found in young and middle adulthood. However, when PT/LBW individuals were in a romantic partnership or had friends, the quality of these relationships was at least as good compared with FT individuals. Hence, analyzing both objective indicators about the occurrence of social transitions and subjective measures about the quality of close relationships provided distinct and complementary information on the social lives of adults born PT. The implications of the current findings are that PT/LBW adults are at increased risk of never experiencing sexual intercourse, being without a supportive partner, and being less likely to experience parenthood. Lack of sexual activity56 and lack of romantic partner support9 are associated with lower levels of happiness and poorer physical and mental health. Future research is needed to identify the predictors and promotive factors of social outcomes in PT/LBW individuals to allow for timely interventions in aiding the transition into adulthood.

eTable 1. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale—Cohort Studies

eTable 2. Mean Percentage of Occurrence of Social Transition

References

- 1.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Adult outcome of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):-. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saigal S, Day KL, Van Lieshout RJ, Schmidt LA, Morrison KM, Boyle MH. Health, wealth, social integration, and sexuality of extremely low-birth-weight prematurely born adults in the fourth decade of life. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):678-686. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):717-728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aylward GP. Update on neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born prematurely. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(6):392-393. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breeman LD, Jaekel J, Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Preterm cognitive function into adulthood. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):415-423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovachy VN, Adams JN, Tamaresis JS, Feldman HM. Reading abilities in school-aged preterm children: a review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(5):410-419. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nosarti C, Reichenberg A, Murray RM, et al. . Preterm birth and psychiatric disorders in young adult life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):E1-E8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyhälä R, Wolford E, Kautiainen H, et al. . Self-reported mental health problems among adults born preterm: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162690. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaekel J, Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Mood and anxiety disorders in very preterm/very low-birth weight individuals from 6 to 26 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(1):88-95. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGowan JE, Alderdice FA, Holmes VA, Johnston L. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1111-1124. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Onofrio BM, Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Preterm birth and mortality and morbidity: a population-based quasi-experimental study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1231-1240. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):262-273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilgin A, Mendonca M, Wolke D. Preterm birth/low birth weight and markers reflective of wealth in adulthood: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173625. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakalım O, Taşdelen-Karçkay A. Friendship quality and psychological well-being: the mediating role of perceived social support. Int Online J Educ Sci. 2016;8(4):1-9. doi: 10.15345/iojes.2016.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powdthavee N. Putting a price tag on friends, relatives, and neighbours: using surveys of life satisfaction to value social relationships. J Socio-Economics. 2008;37(4):1459-1480. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2007.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL. Marriage protection and marriage selection—prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(1):113-123. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00347-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mastekaasa A. Is marriage/cohabitation beneficial for young people? some evidence on psychological distress among Norwegian college students. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16(2):149-165. doi: 10.1002/casp.854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montagna A, Nosarti C. Socio-emotional development following very preterm birth: pathways to psychopathology. Front Psychol. 2016;7:80. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arpi E, Ferrari F. Preterm birth and behaviour problems in infants and preschool-age children: a review of the recent literature. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(9):788-796. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson S, Marlow N. Preterm birth and childhood psychiatric disorders. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(5 Pt 2):11R-18R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212faa0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allin M, Rooney M, Cuddy M, et al. . Personality in young adults who are born preterm. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):309-316. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eryigit-Madzwamuse S, Strauss V, Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Personality of adults who were born very preterm. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100(6):F524-F529. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-308007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hille ETM, Dorrepaal C, Perenboom R, Gravenhorst JB, Brand R, Verloove-Vanhorick SP; Dutch POPS-19 Collaborative Study Group . Social lifestyle, risk-taking behavior, and psychopathology in young adults born very preterm or with a very low birthweight. J Pediatr. 2008;152(6):793-800, 800.e1-800.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, et al. . Personality of young adults born prematurely: the Helsinki study of very low birth weight adults. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):609-617. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathiasen R, Hansen BM, Nybo Anderson AM, Greisen G. Socio-economic achievements of individuals born very preterm at the age of 27 to 29 years: a nationwide cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(11):901-908. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooke RW. Health, lifestyle, and quality of life for young adults born very preterm. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(3):201-206. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.030197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hack M. Young adult outcomes of very-low-birth-weight children. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(2):127-137. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2005.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajantie E, Hovi P, Räikkönen K, et al. . Young adults with very low birth weight: leaving the parental home and sexual relationships—Helsinki Study of Very Low Birth Weight Adults. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e62-e72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Streiner D, et al. . Transition of extremely low-birth-weight infants from adolescence to young adulthood: comparison with normal birth-weight controls. JAMA. 2006;295(6):667-675. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scharf M, Cohen T. Relatedness and individuation among young adults born preterm: the role of relationships with parents and death anxiety. J Adult Dev. 2013;20(4):212-221. doi: 10.1007/s10804-013-9172-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winstanley A, Lamb ME, Ellis-Davies K, Rentfrow PJ. The subjective well-being of adults born preterm. J Res Pers. 2015;59:23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallin A-L, Stjernqvist K. Follow-up of adolescents born extremely preterm: self-perceived mental health, social and relational outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(2):279-283. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husby IM, Stray KM, Olsen A, et al. . Long-term follow-up of mental health, health-related quality of life and associations with motor skills in young adults born preterm with very low birth weight. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:56. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odberg MD, Elgen IB. Low birth weight young adults: quality of life, academic achievements and social functioning. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(2):284-288. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02096.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes MM, Black RE, Katz J. 2500-g low birth weight cutoff: history and implications for future research and policy. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(2):283-289. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2131-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. . The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-analysis. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Health Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borenstein MHL, Higgins JHR. Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duval S, Tweedie RA. Nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(449):89-98. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088-1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Health-related quality of life into adulthood after very preterm birth. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20153148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darlow BA, Horwood LJ, Pere-Bracken HM, Woodward LJ. Psychosocial outcomes of young adults born very low birth weight. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1521-e1528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathewson KJ, Chow CH, Dobson KG, Pope EI, Schmidt LA, Van Lieshout RJ. Mental health of extremely low birth weight survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(4):347-383. doi: 10.1037/bul0000091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raju TNK, Buist AS, Blaisdell CJ, Moxey-Mims M, Saigal S. Adults born preterm: a review of general health and system-specific outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(9):1409-1437. doi: 10.1111/apa.13880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith A, Anderson M 5 Facts about online dating. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating/. Published February 29, 2016. Accessed September 8, 2018.

- 47.Sobotka T, Beaujouan É. Late motherhood in low-fertility countries: reproductive intentions, trends and consequences In: Stoop D, ed. Preventing Age Related Fertility Loss. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018:11-29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-14857-1_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alenius S, Kajantie E, Sund R, et al. . The missing siblings of infants born preterm. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20171354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Umberson D, Pudrovska T, Reczek C. Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: a life course perspective. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(3):612-629. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waite LJ. Does marriage matter? Demography. 1995;32(4):483-507. doi: 10.2307/2061670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Healy E, Reichenberg A, Nam KW, et al. . Preterm birth and adolescent social functioning-alterations in emotion-processing brain areas. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1596-1604. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ranger M, Synnes AR, Vinall J, Grunau RE. Internalizing behaviours in school-age children born very preterm are predicted by neonatal pain and morphine exposure. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(6):844-852. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00431.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lund LK, Vik T, Lydersen S, et al. . Mental health, quality of life and social relations in young adults born with low birth weight. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:146. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heuser KM, Jaekel J, Wolke D. Origins and predictors of friendships in 6- to 8-year-old children born at neonatal risk. J Pediatr. 2018;193:93-101.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolke D, Baumann N, Strauss V, Johnson S, Marlow N. Bullying of preterm children and emotional problems at school age: cross-culturally invariant effects. J Pediatr. 2015;166(6):1417-1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen RC, Bachmann GA. Sexual well-being, happiness, and satisfaction, in women: the case for a new conceptual paradigm. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008;34(4):291-297. doi: 10.1080/00926230802096234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Båtsvik B, Vederhus BJ, Halvorsen T, Wentzel-Larsen T, Graue M, Markestad T. Health-related quality of life may deteriorate from adolescence to young adulthood after extremely preterm birth. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(9):948-955. doi: 10.1111/apa.13069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dalziel SR, Lim VK, Lambert A, et al. . Psychological functioning and health-related quality of life in adulthood after preterm birth. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(8):597-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drukker L, Haklai Z, Ben-Yair Schlesinger M, et al. . “The next-generation”: long-term reproductive outcome of adults born at a very low birth weight. Early Hum Dev. 2018;116:76-80. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hack M, Flannery DJ, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Borawski E, Klein N. Outcomes in young adulthood for very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(3):149-157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kroll J, Karolis V, Brittain PJ, et al. . Real-life impact of executive function impairments in adults who were born very preterm. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017;23(5):381-389. doi: 10.1017/S1355617717000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Männistö T, Vääräsmäki M, Sipola-Leppänen M, et al. . Independent living and romantic relations among young adults born preterm. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):290-297. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts G, Burnett AC, Lee KJ, et al. ; Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group . Quality of life at age 18 years after extremely preterm birth in the post-surfactant era. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1008-13.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale—Cohort Studies

eTable 2. Mean Percentage of Occurrence of Social Transition