Abstract

Introduction

Apnoeic oxygenation using nasal high-flow oxygen delivery systems with heated and humidified oxygen has recently gained popularity in the anaesthesia community. It has been shown to allow a prolonged apnoea time of up to 65 min as CO2 increase was far slower compared with previously reported data from CO2 increase during apnoea. A ventilatory exchange due to the high nasal oxygen flow was proposed explaining that phenomenon. However, recent studies in children did not show any difference in CO2 clearance comparing high-flow with low-flow oxygen. To investigate this ventilatory exchange in adults, we plan this study comparing different oxygen flow rates and the increase of CO2 during apnoea. We hypothesise that CO2 clearance is non-inferior when applying low oxygen flow rates.

Methods and analysis

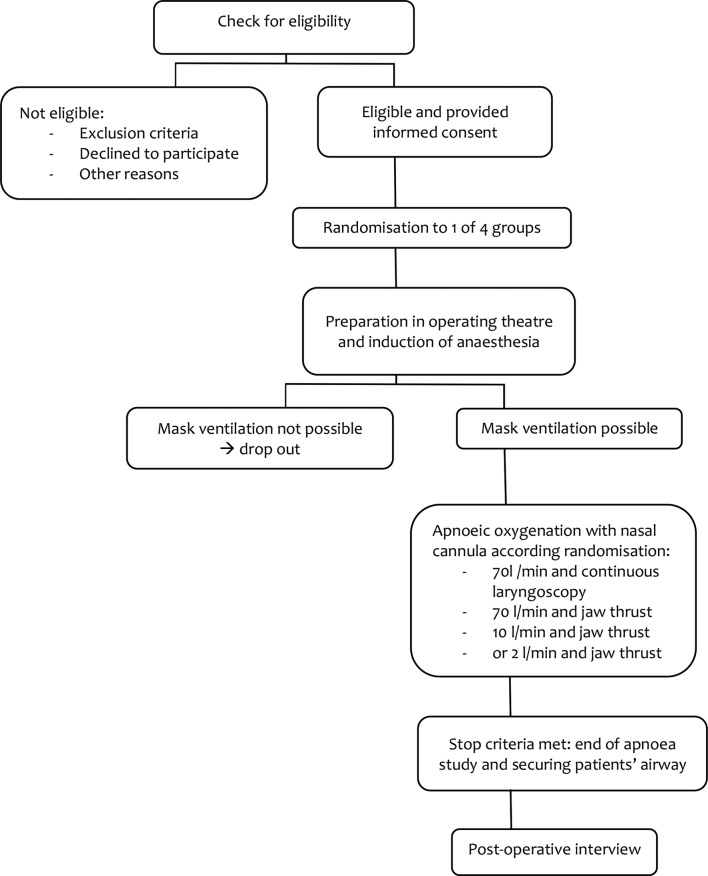

In this single-centre, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial, we randomly assign 100 patients planned for elective surgery to either control (oxygen 70 L/min, airway opened by laryngoscopy) or one of three intervention groups: oxygen 70, or 10, or 2 L/min, all with jaw thrust to secure airway patency. After anaesthesia induction and neuromuscular blockage, either one of the interventions or the control will be applied according to randomisation. Throughout the apnoea period, we will measure the increase of transcutaneous pCO2 (tcpCO2) until any one of the following criteria is met: time=15 min, SpO2 <92%, tcpCO2 >10.67 kPa, art. pH <7.1, K+ >6.0 mmol/L. Primary outcome is the mean tcpCO2 increase in kPa/min.

Ethics and dissemination

After Cantonal Ethic Committee of Bern approval (ID 2018–00293, 22.03.2018), all study participants will provide written informed consent. Patients vulnerable towards hypoxia or hypercarbia are excluded. Study results will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

This study was registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03478774, Pre-results) and the Swiss Trial Registry KOFAM (SNCTP000002861).

Keywords: apnoeic oxygenation, general anaesthesia, hypercapnia, nasal cannula

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Extensive measurements and rigorous study design on comparable groups allows analysis of the physiological response to apnoeic oxygenation and increasing CO2 over time to assess a possible ventilatory effect of nasal oxygen delivery.

Randomised, direct comparison of different nasal oxygen flow rates to investigate their subsequent effect on CO2 clearance over time in order to determine the existence of a ventilatory effect.

For this ‘proof of effect’ study, we include an essentially healthy study population, which limits the transfer of results to patients with compromised lung function or other major health issues.

Due to obvious differences in devices, anaesthetists cannot be blinded but it is unlikely that this will influence our primary outcome (CO2 increase).

Introduction

Apnoeic oxygenation was first scientifically described by Volhard in 1908.1 He sufficiently oxygenated paralysed dogs through a glass tube placed in the trachea without ventilation or respiratory movements. This only worked when 100% oxygen was provided, which was later confirmed by others.2–4 In 2015, Patel et al applied the same principle to high-flow nasal oxygenation (HFNO) but administered heated, humidified oxygen through nasal cannulas at very high flow rates up to 70 L/min in adults. The study group observed a lower-than-expected rise of CO2 using this method. This allowed extension in apnoea time of patients who underwent general anaesthesia, even if they had difficult airways.5 A new term for this oxygen delivery technique was thus created by the study authors: THRIVE (transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange). The ventilatory effect is thought to happen by turbulences caused by the high-flow oxygen combined with the open mouth. These turbulences are believed to continue down through the trachea into the alveoli, which ultimately leads to a washout of CO2. Thereafter, several studies described prolonged apnoea time without desaturation up to 65 min during continuous laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy,5–7 or for laryngeal or tracheal surgery, where a tracheal tube would block the surgical field.8

However, the physiological effects of HFNO remain insufficiently understood. Especially the ventilatory effect has not yet been proven with sufficient data. Rising CO2 levels are the time limitation for HFNO, as they result in effects such as marked acidosis, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate and increased cerebral blood flow.9–11 During the last century, PaCO2 increase in apnoeic patients has been repeatedly studied. According to that literature, PaCO2 increases rapidly during the first minute of apnoea (1.6–1.73 kPa), whereas afterwards, a linear increase of about 0.4–0.67 kPa/min sets in.4 11–13 This physiological CO2 increase is faster than the one described using HFNO, which is only about 0.15–0.24 kPa/min.

Recently, two studies showed that apnoeic oxygenation using low flow rates in children is equal to HFNO14 15 without difference regarding CO2 increase. Given this new evidence, it seems possible that the nasal oxygen flow rate has little to no impact on CO2 clearance in adults as well.

Therefore, we will compare different nasal flow rates of 100% oxygen (70, 10 and 2 L/min) with HFNO (70 L/min). Furthermore, we will apply continuous laryngoscopy to HFNO and compare it to normal jaw thrust in the intervention groups in order to determine how mouth opening influences CO2 clearance.

We hypothesise that any of our intervention groups (70, 10 and 2 L/min, all with jaw thrust) is non-inferior to the control group (HFNO with oxygen 70 L/min using continuous laryngoscopy) regarding mean transcutaneous CO2 increase in kPa/min.

Methods and analysis

This study is registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03478774) as well as on the Swiss Trial Registry KOFAM (SNCTP000002861).

Aims

We want to better understand possible ventilatory effects during apnoeic oxygenation using nasal cannulas at different flow rates and demonstrate the physiological effects of increased CO2 levels on human physiology during general anaesthesia.

Design

This is a single-centre, single-blinded, prospective, non-inferiority randomised controlled trial at the Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland. After the study participant has enrolled in the study by signing the informed consent, he or she will be randomised using a computer-generated sequence. Once general anaesthesia is induced and mask ventilation is possible, the sealed envelope will be opened and oxygen flow will be provided according to randomisation. Therefore, the participant is blinded towards his or her group allocation, but anaesthesiologists cannot be blinded, because devices clearly differ from each other. Once randomised, the participant will stay in the allocated group for analysis, even if another intervention is applied (intention-to-treat).

Study population

Possible participants will be screened for eligibility checking the surgical schedule and we invite them to participate during our pre-anaesthesia interview. To allow patients sufficient time to consider participation, we contact eligible study participants the day before surgery. We will include adults (>18 years of age), who will undergo elective surgery requiring general anaesthesia, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical health status I-III, SpO2 ≥96% breathing room air, and who provide written informed consent in German as this is the common language spoken in Bern, Switzerland.

Because we intend to study the impact of apnoeic oxygenation on the accumulation of CO2, we will exclude all patients who—through their underlying condition—could bias or influence the normal physiological response. Also, for patient safety reasons, we will exclude patients who might be harmed due to study-related effects or measurements. Specifically, we exclude:

Patients with risk factors for difficult airway (indication for flexible optic intubation, high risk of regurgitation or expected difficult mask ventilation).

Vulnerability towards hypoxaemia (known coronary heart disease, peripheral occlusive arterial disease, known stenosis of the carotid or vertebral arteries, anaemia or pregnancy).

Vulnerability towards hypercarbia (pulmonary arterial hypertension, increased intracranial pressure, intracranial surgery or hyperkalaemia).

Obstructive sleep apnoea, nasal obstruction, body-mass index <16 kg/m2 or >35 kg/m2 or known, suspected cervical spine instability, neuromuscular disorder, absent power of judgement, limited knowledge of German language, allergies towards any of the used agents.

In order to further reduce potential bias, we will stratify randomisation according to body-mass index (BMI) into three groups (16–25, 25–30 and 30–35 kg/m2) and according to smoker status into four groups (non-smokers, non-daily smokers, daily smokers <40 years of age and daily smokers >40 years of age). According to the BMI, smoking status and age group, the patient fits into one of the possible 12 strata. Within each strata, the groups are being randomised for the different flow rates. Participants will be randomised in a 1:1:1:1 ratio (25 patients per group) using a computer-generated sequence which will be executed by a study nurse.

Sample size

Patel et al showed an increase of only 0.15 kPa/min with a flow rate of 70 L O2/min and maximal mouth opening.5 However, end-tidal CO2 was measured, not transcutaneous tcpCO2. Gustafsson et al measured both, tcpCO2 as well as arterial pCO2, and found a CO2 increase of 0.24 kPa/min, with a SD of 0.05 kPa, which was almost twice as high as the tcpCO2 value.6 Using a non-inferiority design, a difference of means of 0.04 kPa/min, a SD of 0.05 kPa/min, an alpha of 0.025 (one-sided) with a power of 80%, revealed a necessary sample size of 22 patients per group. We will include 25 patients in each group (100 patients in total) to account for possible dropouts. A difference of means of 0.04 kPa/min CO2 increase would still only result in an absolute difference of 1.2 kPa CO2 after 30 min of apnoea time. We defined this as measurable, but still clinically acceptable and therefore non-inferior because the normal range of standard arterial pCO2 is 1.3 kPa (4.7–6.0 kPa).16

Procedure

Once written informed consent is obtained and pregnancy is excluded in female patients by a pregnancy test, we will extract demographic data from the hospital information system. This includes data collected through routine patients’ workflow: age, sex, weight, height, BMI, airway risk factors (Mallampati score, mouth opening, thyromental distance, reduced neck movement, retrognathia, and dental status) underlying diseases, smoking habits, ASA physical health status and indication for surgery.

On the day of surgery, we will place an arterial cannula into the radial artery under local anaesthesia and draw arterial blood gases from the awake study participant breathing room air as a baseline measurement. We will instal (1) standard anaesthesia monitoring: EKG, pulse oximetry, invasive blood pressure, end-tidal O2, end-tidal CO2, train of four (TOF), Narcotrend EEG (Narcotrend, Hannover, Germany), and (2) study-related monitoring: cardiac output (LiDCO, LiDCO Ltd, London, UK), thoracic electric impedance tomography (EIT; using PulmoVista 500, by Dräger, Lübeck, Germany), bilateral near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS; using Niro-200NX, Hamamatsu, Tokyo, Japan) and transcutaneous pCO2and pO2 (tcpO2) measurement (both via TCM5, Radiometer, Thalwil, Switzerland). After that, we will start bag-mask preoxygenation until end-tidal O2 has reached 90%. Patients will receive a fentanyl bolus of 2 µg/kg, and induction of anaesthesia will begin using a target-controlled infusion (TCI, Schnider model using syramed µSP6000, Arcomed AG, Regensdorf, Switzerland) for propofol with a target concentration of 3.0 µg/mL and TCI for remifentanil (Minto model using syramed µSP6000, Arcomed AG, Regensdorf, Switzerland) with a target concentration of 2.0 ng/mL. We will administer rocuronium 0.9 mg/kg to achieve neuromuscular blockage. After induction, general anaesthesia will be confirmed by absent end-tidal CO2 readings, unconsciousness and Narcotrend-values in the target range of 40–60 under bag-mask ventilation.

Once mask ventilation with a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 12/min is successful, the previously sealed envelope containing the randomisation will be opened and the intervention will be prepared according to group allocation.

For safety reasons, the experiment will be discontinued if mask ventilation is impossible even after full neuromuscular blockage and placement of an oropharyngeal tube. The anaesthetist in charge would then intubate the trachea and no study-related measurements would take place.

For all patients who show a cardiovascular reaction (an increase of heart rate and blood pressure) to the study procedure (laryngoscopy or jaw thrust), we will titrate remifentanil to effect. Once a steady state has set in, we will no longer interfere with remifentanil. Whenever Narcotrend values rise above our target range, propofol will be increased. We will not correct dropping Narcotrend values as this is likely to be caused by increasing CO2 and therefore an effect we want to measure.

When complete neuromuscular blockage has been confirmed by TOF=0, we will stop mask ventilation and start the apnoea time. Arterial blood gas will be drawn and analysed at the start of apnoea.

If assigned to the control group, the study participant will receive high-flow humidified oxygen at 70 L/min via Optiflow (Fisher&Paykel, Auckland, NewZealand) throughout the apnoea period while the glottis will be visualised by video laryngoscopy (MacGrath MAC, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland), thus assuring airway patency. If assigned to one of the intervention groups, one of the senior anaesthesia researchers will apply jaw thrust and one of the following flow rates: (1) high-flow humidified oxygen at 70 L/min via Optiflow; (2) medium-flow humidified oxygen at 10 L/min (Carbamed digiflow, Switzerland; Aquapak Hudson RCI, Teleflex, Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA; O2Star nasal cannula curved, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany); or (3) low-flow humidified oxygen at 2 L/min (Carbamed digiflow, Switzerland; Aquapak Hudson RCI, Teleflex, Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA; O2Star nasal cannula curved, Dräger, Lübeck, Germany) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

During jaw thrust, upper airway patency will be visually confirmed by a nasopharyngeal fiberscope (EF-N slim, Acutronic, Hirzel, Switzerland).17 Only if the airway is obstructed, we will insert an oropharyngeal airway tube (Guedel airway, Intersurgical, Workingham, Berkshire, UK). We will not assess the degree of opening, as this would not have any direct consequences for the study.

During apnoea time, we will continuously measure invasive arterial blood pressure, pulse oximetry and EKG as part of standard monitoring. Furthermore, we will continuously measure tcpCO2, tcpO2 by applying a probe to the patient’s chest, two fingers below the clavicle; depth of anaesthesia (Narcotrend); bilateral brain oxygenation (NIRS); cardiac output by pulse contour analysis; and ventilation distribution changes by thoracic electrical impedance tomography. For this, resulting potential differences are measured, and impedance distribution sampled at 30 Hz will be calculated by an automated linearised Newton-Raphson reconstruction algorithm.18 Relative change in end-expiratory lung impedance (EELI) and measures of ventilation inhomogeneity such as the global inhomogeneity index will be calculated as described previously, using customised software (Matlab R2013a, The MathWorks, Nattick, Massachusetts, USA).19 20

Furthermore, we will take arterial blood samples at the onset of apnoea, 1 min after apnoea, and thereafter every 2 min to perform blood gas analysis (total of max. 10 measurements). These blood samples will be analysed for PaO2, SaO2, PaCO2, pH, bicarbonate and potassium.

During the induction of anaesthesia, potential hypotension due to the anaesthetic drugs will be counteracted with a continuous infusion of norepinephrine. Thereafter, a steady state will set in and any change in blood pressure is due to the vasoactive effect of CO2. As we want to measure these effects, we will no longer interfere with blood pressure, except for persisting hypotension.

The experiment will end when any of the following criteria is met: SpO2 <92%, ptcCO2 >10.67 kPa, pH <7.1, K+ >6.0 mmol/L, t=15 min. Thereafter the trachea will be intubated according to the decision of the attending anaesthetists. With that, the presurgical part of the study will end.

Study participants will either be visited on the ward or contacted by phone on the first postoperative day in the morning to ask about the quality of recovery.21 22 This includes the ability to breathe easily, feeling rested, being able to enjoy food, getting support from hospital doctors and nurses as well as any pain, nausea and vomiting, feeling worried or anxious, or feeling sad or depressed. Furthermore, we ask specifically for pain localised in the patient’s throat, mandibular joint, or head; nasal dryness; lip injuries; dental damages; other injuries; or any other discomfort or complication. For assessing the severity of complications, we will use a (modified) visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 is no pain (or discomfort) and 10 is maximum pain (or discomfort). We will also assess all injuries obtained during airway management and the study period. After this interview, no further data will be acquired and the study ends.

Objectives

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome is to measure the increase of mean transcutaneous CO2 over time in kPa/min and to determine the influence of nasal oxygen flow rate (70, 10 and 2 L/min) and the presence of an open mouth (jaw thrust vs continuous laryngoscopy).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are: lowest O2 saturation; changes in EELI, which will help quantify the degree of atelectasis after intubation, and influence of increasing CO2 on: cardiac output and systemic blood pressure, invasive arterial blood pressure, pulse oximetry and EKG as part of standard monitoring, tcpO2, depth of anaesthesia, bilateral brain oxygenation (NIRS), arterial blood gas analysis (PaO2, SaO2, PaCO2, pH, bicarbonate and potassium). Furthermore: postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, feeling worried or anxious, or feeling sad or depressed, injuries or any other discomfort or complication.

Statistical plan

Distribution of data will be checked for normality using qq-plots and the Shapiro-Wilks analysis using Stata (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). For our primary outcome parameter, the rise of ptcCO2, we will use a linear mixed model using groups and minutes. Normal distributed data will be presented as means and SD, otherwise median and IQR will be used. Proportions will be presented as numbers and percentage. Analytical statistics uses Mann-Whitney U test and Student’s t-test, according distribution, or ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis for multiple group comparisons. Each of the groups will a priori be compared with the control group independently, therefore no correction for multiple comparisons will have to be used. Other multiple comparisons and any subgroup analyses will be performed using appropriate correction factors. Proportions will be compared by χ2 test or Fisher exact test. As sensitivity analyses, we will do regression analyses, using mixed effects linear regressions. All statistical analyses will be performed on an intention-to-treat basis. We will also include a per-protocol analysis in order to minimise bias for the standard treatment group. If the results of such an analysis are consistent with those from the intention-to-treat approach and if both lie below the non-inferiority threshold, the inference regarding non-inferiority is strengthened. A p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Patient involvement

No patients or patient representatives were involved in the design of this trial.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practise (ICH GCP) and local regulations with the approval of the Cantonal Ethics Committee Bern, following the Swiss law for human research.23 The ethics committee already approved our study (ID 2018–00293), including the safety endpoints. A drop in O2 saturation <92% allows for timely securing the airway without risk of hypoxic damages of the study participants. Furthermore, prior publications suggest it to be very likely that all groups maintain stable O2 saturation throughout the maximum apnoea time of 15 min.24 25 Rising CO2 levels could lead to acidosis; therefore, patients vulnerable to hypercarbia are excluded preliminarily (see the Study population section). As routinely stated in the protocol for the ethics committee, the study can be terminated prematurely if new evidence suggesting severe disadvantage or increased morbidity will arise during the study period.

All study data will be directly recorded in the case report form (CRF), which should also be considered being source data. These data will be transferred into the departmental research documentation system—LabKey (LabKey Software, Seattle, Washington, USA, V.14.3). All study data will be archived for a minimum of 10 years after study termination or premature termination of the clinical trial.

Data will be transferred into a secure, web-based data integration platform and controlled independently by two members of the study team. Additionally, data are double-checked by comparing the screening records with the digital anaesthesia documenting system of the hospital.

A study nurse otherwise not involved in the study will be in charge of data monitoring and auditing after every 20 patients.

Important modifications to the protocol will have to be reported to the ethics committee.

Both the principal investigator and sponsor investigator will have access to the final trial dataset. Other researchers may be granted access to the dataset to answer scientific questions.

Results will be presented at national and international scientific meetings and will be published in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

Informed consent

In order to be eligible for the study, all patients have to sign an ethics committee approved informed consent form. All potential risks and benefits will be thoroughly explained by study personnel and the patient will be given enough time to consider his or her study participation.

Discussion

Humidified HFNO is a widely used therapy in intensive care for both adults and paediatric spontaneously breathing patients. The new use in patients under general anaesthesia has revitalised the old concept of apnoeic oxygenation. Its use in anaesthesiology spreads from oxygenating an awake patient to pre-oxygenation, as well as to apnoeic oxygenation during rapid-sequence intubation (RSI), or during microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy. More and more applications for humidified HFNO or THRIVE are emerging and they show great potential.

However, there is only limited evidence explaining physiological changes during HFNO, especially the proposed mechanism of CO2 elimination by a ventilatory effect in anaesthetised patients. It remains unknown how different flow rates affect CO2 clearance and if a minimal flow rate (of 2 L/min) is able to maintain oxygenation over 15 min. There are a few studies suggesting lower flow rates could also be effective.24 25 However, no prospective study compared high flow with low flow so far; and it has not yet been determined how flow rate influences CO2 clearance. As high CO2 levels have a multitude of effects, such as pulmonic arterial vasoconstriction, acidosis and hyperkalaemia, a better understanding of CO2 clearance could lead to the definition of contraindications or safety measurements for humified HFNO/THRIVE, especially for longer apnoea periods (eg, during micro laryngoscopy).

It is not known whether changes of thoracic EIT in anaesthetised patients are similar to those in awake patients.26 For example, it is already known that EELI is increased in awake patients. This is probably due to a higher pharyngeal pressure observed in patients with HFNO who breathe spontaneously. The effect has never been evaluated in anaesthetised patients.27 28

Also, haemodynamic changes during apnoeic oxygenation and under increasing PaCO2 have not yet been investigated rigorously. We only found studies describing increased PaCO2 and its influence on cardiac output and brain perfusion in awake patients and healthy volunteers.9 10 29 It is very likely that anaesthetised patients have a different reaction due to the vasodilatory effect of most anaesthetic drugs, which could very easily overweigh the vasoconstrictive effects of increased CO2 levels.

Overall, knowledge of the underlying physiological mechanisms during HFNO in anaesthetised patients is still very limited. This study investigates under rigorously controlled circumstances the concept of humidified HFNO on prolonged apnoea time, presumably without desaturation. With our findings, we hope to improve airway management safety as this study enables the medical community to better understand the physiology behind apnoeic oxygenation and the influence of different nasal flow rates on CO2 clearance. Our study’s extensive setup also allows us to measure the effects of increased CO2 on cerebral perfusion and cardiac output.

If low-flow oxygen administration with standard nasal cannula is non-inferior compared with high-flow humidified HFNO, it could have a direct clinical impact. Oxygen and standard nasal cannula are ubiquitously available and it will be hard to argue against apnoeic oxygenation during routine intubation. Especially for RSI and other emergency airway procedures, apnoeic oxygenation may be—and perhaps should be—performed using a standard nasal cannula at a low flow rate.30 For patients at risk of desaturation, this has the potential to reduce complication of hypoxia and therefore will improve patient safety with little additional resources.

Due to the design of this trial, we will not be able to determine the influence of pathophysiological alterations of patients’ underlying diseases, as we exclude severely ill patients from this study for safety reasons. Furthermore, although we include 100 patients in this trial, we may still end up with an uneven distribution of risk factors. To minimise this bias, we stratify according to BMI and smoking status, as we assume these factors to be the most influential on our primary outcome.

Provided all groups have a similar CO2 clearance, the inclusion of 100 patients will provide a solid foundation to detect even smaller haemodynamic, thoracic EIT or EEG changes. Nevertheless, all results are to be considered for anaesthetised patients using propofol and remifentanil. We do not know how other anaesthetic drugs would potentially interfere with patients’ physiology.

All this leads us to the conclusion that this study will be able to provide highly interesting results and urgently needed evidence on physiological changes during HFNO and CO2 increase in adult patients during apnoeic oxygenation. We will find an answer to our question, if the application of nasal oxygen at 70, 10 or 2 L/min using a jaw thrust is non-inferior compared with nasal oxygen at 70 L/min using continuous laryngoscopy in regard to CO2 clearance in anaesthetised patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RG and LT: conceived the study. RG, LT, FS, HK and TR: wrote the study protocol. RG, LT, FS and HK: developed the practical approach to measurement and recruitment. TRiv: was involved in the protocol development and manuscript review. LT: designed the statistical analysis plan for the protocol. All authors critically reviewed this manuscript and agree to its final form.

Funding: This research is funded by a departmental research grant assigned to LT. For this study, Fisher & Paykel (Auckland, New Zealand) provide all necessary breathing circuits and nasal cannulas without costs.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Cantonal Ethics Committee of Bern (ID 2018-00293).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Volhard F. Über künstliche Atmung durch Ventilation der Trachea und eine einfache Vorrichtung zur rhythmischen künstlichen Atmung. Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1908;55. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meltzer SJ, Auer J. Continuous respiration without respiratory movements. J Exp Med 1909;11:622–5. 10.1084/jem.11.4.622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartlett RG, Brubach HF, Specht H. Demonstration of aventilatory mass flow during ventilation and apnea in man. J Appl Physiol 1959;14:97–101. 10.1152/jappl.1959.14.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eger EI, Severinghaus JW. The rate of rise of PaCO2 in the apneic anesthetized patient. Anesthesiology 1961;22:419–25. 10.1097/00000542-196105000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel A, Nouraei SA. Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange (THRIVE): a physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia 2015;70:323–9. 10.1111/anae.12923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gustafsson IM, Lodenius Å, Tunelli J, et al. Apnoeic oxygenation in adults under general anaesthesia using Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange (THRIVE) - a physiological study. Br J Anaesth 2017;118:610–7. 10.1093/bja/aex036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lyons C, Callaghan M. Apnoeic oxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen for laryngeal surgery: a case series. Anaesthesia 2017;72:1379–87. 10.1111/anae.14036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Riva T, Seiler S, Stucki F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula therapy and apnea time in laryngeal surgery. Paediatr Anaesth 2016;26:1206–8. 10.1111/pan.12992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bain AR, Ainslie PN, Hoiland RL, et al. Cerebral oxidative metabolism is decreased with extreme apnoea in humans; impact of hypercapnia. J Physiol 2016;594:5317–28. 10.1113/JP272404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sechzer PH, Egbert LD, Linde HW, et al. Effect of carbon dioxide inhalation on arterial pressure, ECG and plasma catecholamines and 17-OH corticosteroids in normal man. J Appl Physiol 1960;15:454–8. 10.1152/jappl.1960.15.3.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frumin MJ, Epstein RM, Cohen G. Apneic oxygenation in man. Anesthesiology 1959;20:789–98. 10.1097/00000542-195911000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holmdahl MH. Pulmonary uptake of oxygen, acid-base metabolism, and circulation during prolonged apnoea. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1956;212:1–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stock MC, Schisler JQ, McSweeney TD. The PaCO2 rate of rise in anesthetized patients with airway obstruction. J Clin Anesth 1989;1:328–32. 10.1016/0952-8180(89)90070-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riva T, Pedersen TH, Seiler S, et al. Transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange for oxygenation of children during apnoea: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:592–9. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Humphreys S, Lee-Archer P, Reyne G, et al. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) in children: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2017;118:232–8. 10.1093/bja/aew401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Habben FA. Blutgasanalyse. 2018. http://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Blutgasanalyse (accessed 19 Jan 2018).

- 17. Uzun L, Ugur MB, Altunkaya H, et al. Effectiveness of the jaw-thrust maneuver in opening the airway: a flexible fiberoptic endoscopic study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2005;67:39–44. 10.1159/000084304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yorkey TJ, Webster JG, Tompkins WJ. Comparing reconstruction algorithms for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1987;34:843–52. 10.1109/TBME.1987.326032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schnidrig S, Casaulta C, Schibler A, et al. Influence of end-expiratory level and tidal volume on gravitational ventilation distribution during tidal breathing in healthy adults. Eur J Appl Physiol 2013;113:591–8. 10.1007/s00421-012-2469-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wettstein M, Radlinger L, Riedel T. Effect of different breathing aids on ventilation distribution in adults with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 2014;9:e106591 10.1371/journal.pone.0106591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Myles PS, Boney O, Botti M, et al. Systematic review and consensus definitions for the Standardised Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine (StEP) initiative: patient comfort. Br J Anaesth 2018;120:705–11. 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Theiler L, Hermann K, Schoettker P, et al. SWIVIT--Swiss video-intubation trial evaluating video-laryngoscopes in a simulated difficult airway scenario: study protocol for a multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in Switzerland. Trials 2013;14:94 10.1186/1745-6215-14-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bundesverfassung der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft, Artikel 118b. 2010.

- 24. Teller LE, Alexander CM, Frumin MJ, et al. Pharyngeal insufflation of oxygen prevents arterial desaturation during apnea. Anesthesiology 1988;69:980–2. 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heard A, Toner AJ, Evans JR, et al. Apneic oxygenation during prolonged laryngoscopy in obese patients: a randomized, controlled trial of Buccal RAE Tube Oxygen Administration. Anesth Analg 2017;124:1162–7. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parke RL, Bloch A, McGuinness SP. Effect of Very-High-Flow Nasal Therapy on Airway Pressure and End-Expiratory Lung Impedance in Healthy Volunteers. Respir Care 2015;60:1397–403. 10.4187/respcare.04028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Groves N, Tobin A. High flow nasal oxygen generates positive airway pressure in adult volunteers. Aust Crit Care 2007;20:126–31. 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parke R, McGuinness S, Eccleston M. Nasal high-flow therapy delivers low level positive airway pressure. Br J Anaesth 2009;103:886–90. 10.1093/bja/aep280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Price HL. Effects of carbon dioxide on the cardiovascular system. Anesthesiology 1960;21:652–63. 10.1097/00000542-196011000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Ann Emerg Med 2012;59:165–75. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.