Abstract

Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix is fundamental to tissue integrity and human health. Integrins are the main cellular adhesion receptors that through multifaceted roles as signalling molecules, mechanotransducers and key components of the cell migration machinery are implicated in nearly every step of cancer progression from primary tumour development to metastasis. Altered integrin expression is frequently detected in tumours, where integrins have roles in supporting oncogenic growth factor receptor (GFR) signalling and GFR-dependent cancer cell migration and invasion. In addition, integrins determine colonization of metastatic sites and facilitate anchorage-independent survival of circulating tumour cells. Investigations describing integrin engagement with a growing number of versatile cell surface molecules, including channels, receptors and secreted proteins, continue to lead to the identification of novel tumour-promoting pathways. Integrin-mediated sensing, stiffening and remodelling of the tumour stroma are key steps in cancer progression supporting invasion, acquisition of cancer stem cell characteristics and drug resistance. Given the complexity of integrins and their adaptable and sometimes antagonistic roles in cancer cells and the tumour microenvironment, therapeutic targeting of these receptors has been a challenge. However, novel approaches to target integrins and antagonism of specific integrin subunits in stringently stratified patient cohorts are emerging as potential ways forward.

Introduction

The main cell adhesion receptors for components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), the integrins, are a family of 24 transmembrane heterodimers generated from a combination of 18α integrin and 8β integrin subunits. Integrins can be classified into receptors recognizing Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide motifs, collagen receptors, laminin receptors and leukocyte-specific integrins1. However, integrins also recognize numerous other physiological ligands and serve as receptors for snake venoms, viruses and other pathogens2,3. While some integrins bind to only specific ECM ligands (for example, α5β1 integrin to fibronectin), others exhibit a broader ligand-binding repertoire overlapping with other integrin heterodimers (for example, αvβ3 integrin binds to fibronectin, vitronectin, fibrinogen and thrombospondin, to name a few)1. Engagement of the same ligand by different integrin heterodimers can trigger distinct signalling in the cell and thus the pattern of integrin expression on the cell surface is key to determining cell behaviour in response to microenvironmental influences. Integrins heterodimerize in the endoplasmic reticulum and, following further post-translational modifications in the Golgi, are trafficked to the cell surface in an inactive conformation4, where they can become activated to engage the ECM. Integrins are unique multidirectional signalling molecules (Box 1). Integrin activation and binding to the ECM trigger the recruitment of the so-called adhesome: a complex array of signalling, scaffolding and cytoskeletal proteins engaging directly or indirectly with integrin cytoplasmic tails5,6,7. Together, these adhesion constituents represent a complex and highly dynamic machinery responsible for regulating aspects of cell fate such as survival, migration, polarity and differentiation8. Therefore, dysregulated integrin-mediated adhesion and signalling is a precursor in the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including bleeding disorders, cardiovascular disease and cancer8.

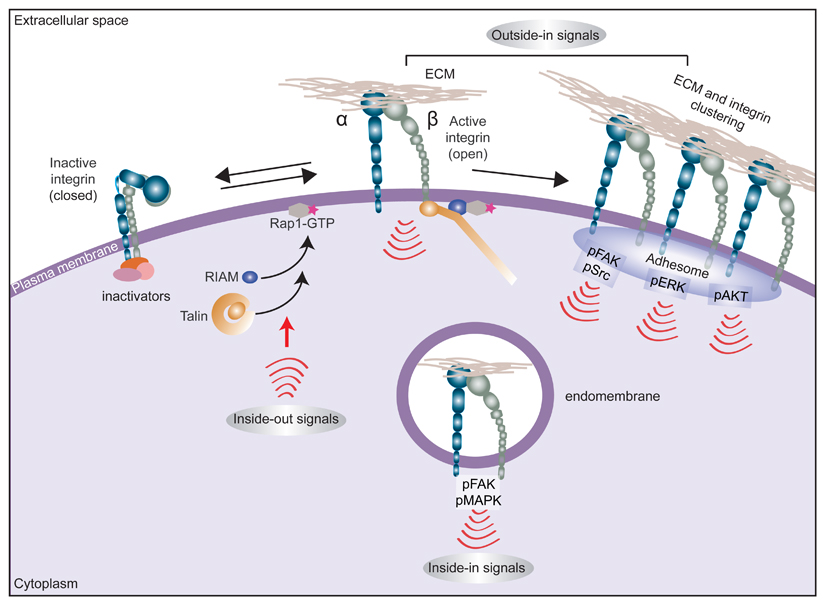

Box 1. Multidirectional integrin signalling.

Integrins are unique bidirectional signalling molecules that exist in different conformational states that determine the receptor affinity for extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins: a bent (closed) integrin represents the inactive form, with low affinity for ECM ligands, whereas a fully extended (open) integrin is active and capable of eliciting downstream signalling and cellular responses following ligand engagement. Many ECM proteins contain multivalent integrin recognition sites and/or are assembled as multiprotein deposits or fibrils in the extracellular compartment. Ensuing integrin–ligand engagement (adhesion) and clustering on the plasma membrane provides a platform for the assembly of multimeric complexes that provoke downstream adhesion signalling (‘outside-in’ signalling). This outside-in signal is heterodimer-dependent and context-dependent (for example, specific to the cell type or the ECM ligand engaged or dictated by ECM properties) but typically involves recruitment and autophosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) with subsequent recruitment and activation of SRC1,5. Integrin adhesion also activates, among other pathways, the RAS–MAPK and PI3K–AKT signalling nodes. Integrins also respond to ‘inside-out’ signals, whereby stimulation of small GTPase RAP1A activity on the plasma membrane triggers recruitment of RAP1-GTP-interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM; also known as APBB1IP) to activate talin. Talin binding to the β-integrin subunit tail triggers an extended open receptor conformation and recruitment of additional integrin-activating proteins such as kindlins205. Integrin activation can be counterbalanced by inactivating proteins such as integrin cytoplasmic domain-associated protein 1 (ICAP-1; also known as ITGB1BP1), filamin A, SHARPIN and proteins of the SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains (SHANK) family, which, directly or indirectly, restrict the ability of talin to bind and activate integrins16,206.

Integrins have also been demonstrated to be functional in subcellular locations other than plasma membrane adhesion sites, where their roles are well recognized. Active integrins and integrin-dependent signalling complexes, along with ECM ligands or receptor tyrosine kinases found within endosomes, can trigger ‘inside-in’ signalling44,45,123 (see also Fig. 2).

Altered integrin expression patterns have been linked to many types of cancer9,10,11. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes some purported associations between the expression of specific integrin subunits or integrin heterodimers and the extent of neoplastic progression, patient survival or response to therapy; however, it is worth noting that most of the observed clinical data are correlative, rather than direct evidence of a role for specific integrins in the indicated cancers. Moreover, some of these studies provide contradictory data either within the same cancer type or in relation to different cancers for the same integrin molecules. These discrepancies may be explained on several levels by factors, including challenges in acquiring patient samples at equivalent stages of disease and in classifying disease state based on different methodologies; the reported integrin expression profiles possibly being a dynamic property of the disease, with switching between integrin heterodimers, binding of different integrins to the same ligand (potentially occurring in response to treatment or microenvironmental cues12,13,14) and fluctuation of integrin levels at different stages of disease progression; heterogeneity in patient samples; and altered integrin expression, although evident in many cancers, not being a direct readout of integrin signalling and therefore possibly not being the defining feature of the disease.

Indeed, integrin function in cells is regulated by more than mere expression; multiple additional levels of regulation exist. Integrins are constantly endocytosed and recycled back to the plasma membrane, the kinetics of which are frequently altered in cancer cells, resulting in a change in the normal ratios of the receptors between the cell surface and endosomal pools4,15. Furthermore, integrin activity is tightly regulated in normal cells (Box 1), and aberrations in integrin activity confer cells with oncogenic properties through altered adhesion dynamics and increased integrin signalling16. A vast collection of literature exists regarding altered integrin expression in different cancer types (Supplementary Table 1), the applicability of integrins as therapeutic targets10,11,17 and, given that integrin profiles are used to identify tumour-initiating cells, the potential role of integrins in cancer stem cells9,11. In this Review, we discuss the contribution of integrins to the different steps of the metastatic cascade with a special focus on key mechanisms identified in the past 5 years that underlie the ability of integrins to drive invasive protrusions, influence tumour–stroma crosstalk, support the formation of metastases and induce drug resistance in solid tumours. However, it is important to note that integrins play vital roles in other cancer-relevant processes not described in this Review, including white blood cell trafficking and activation, chronic inflammation, immune mimicry and angiogenesis, which ultimately determine disease state.

Despite the disappointing outcome of previous clinical trials targeting integrins, the continued drive to better understand the role of these receptors in cancer progression could lead to the development of innovative targeting approaches and a revival in the field.

Integrins and the metastatic cascade

Integrins and integrin-dependent processes have been implicated in almost every step of cancer progression, including cancer initiation and proliferation, local invasion and intravasation into vasculature, survival of circulating tumour cells (CTCs), priming of the metastatic niche, extravasation into the secondary site and metastatic colonization of the new tissue (Fig. 1). For most solid tumours, the metastatic cascade begins with cancer cells breaching the underlying basement membrane. This process is considered to require proteolytic activity, and integrins contribute by upregulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase genes and facilitating protease activation and function at the ECM interface18. Invasive carcinomas penetrate the stroma and migrate into the surrounding tissue as individual cells or as cell clusters by multiple different integrin-dependent mechanisms. In addition, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can contribute to cancer progression via several integrin-linked mechanisms. CAFs can lead invasion by generating pro-migratory tracks through the stromal ECM19, by depositing fibronectin20,21, by regulating fibronectin alignment22 or by physically pulling cancer cells out of the primary tumour23.

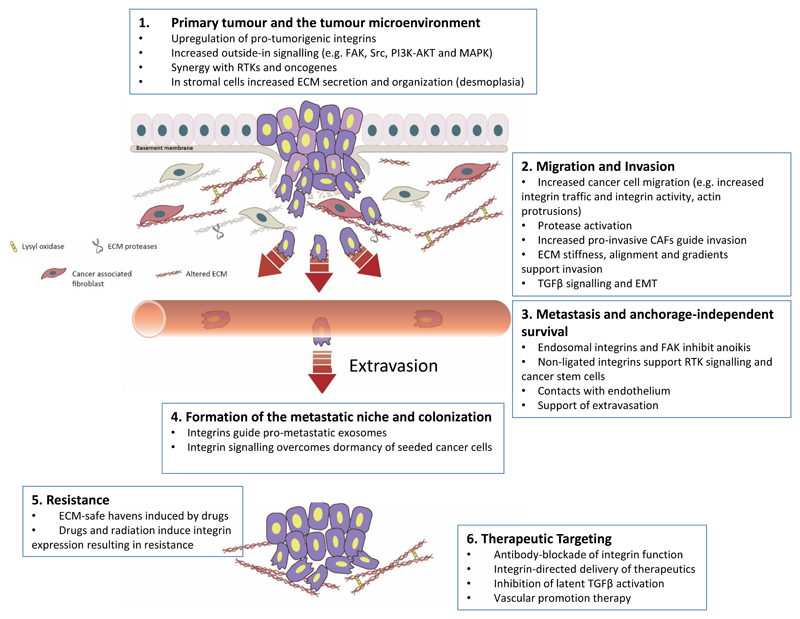

Fig. 1. Integrin involvement in many of the steps of cancer progression.

Integrin expression and/or function have been implicated in nearly every stage of cancer development from primary tumour formation to cancer cell extravasation and formation of a metastatic niche (parts 1–4). In addition, integrin signalling has been linked to the acquisition of drug resistance (part 5). This fact, together with the vital roles of integrins in cancer, has rendered integrins and integrin-dependent functions attractive therapeutic targets in the fight against cancer (part 6). CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β.

CTCs are readily detected in patients with cancer, suggesting that cancer cells are constantly entering the circulation from the primary tumour24. While normal epithelial cells undergo anoikis25, CTCs undergo anchorage-independent growth and display anoikis resistance through pathways involving altered integrin signalling26. For successful metastasis, CTCs must attach within the vasculature of distant organs and extravasate into the perivascular tissue. Thrombus formation is thought to support tumour cell extravasation by recruiting fibronectin to activate integrins27,28. Finally, following successful extravasation, integrin contacts with the ECM in the perivascular tissue dictate whether the seeded cancer cells continue to proliferate or become dormant24.

The primary tumour and microenvironment

Integrins as tumour promoters and tumour suppressors

As depicted in Supplementary Table 1, the reported links between integrin expression and cancer are highly dependent on the tumour type and on the state of the disease, complicating the applicability of these receptors as therapeutic targets and underlying the need for patient stratification on the basis of integrin profiles in future studies. For example, while most β1 integrins, and more specifically α3β1 integrin, are necessary for mammary tumorigenesis29,30, α2β1 integrin is a metastasis suppressor in breast cancer31, and laminin-binding integrins have both growth-promoting and growth-inhibiting functions (reviewed in ref.32). Integrins that activate transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) may be tumour suppressors33 until the cancer becomes refractory to the anti-proliferative effects of TGFβ; after this event, the same integrins can drive tumour progression34. There is also crosstalk between integrins, which determines their response in activating TGFβ. Genetic depletion of β1 integrin induces a compensatory-like upregulation of β3 integrins that may promote activation of TGFβ and TGFβ-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer cells35. However, β3 integrin overexpression alone was not sufficient to replicate the pro-metastatic phenotype observed in response to β1 integrin loss, suggesting that other factors are involved in regulating TGFβ signalling. Increased expression of tumour-promoting integrins correlates with poor prognosis; the underlying contribution of these integrins to cancer progression varies but can include support of cancer invasion, which occurs in part by cooperating with or upregulating proteases36,37,38,39,40 or by switching the integrin–ECM linkage. For example, upregulation of α5β1 integrin and fibronectin is linked to poor prognosis and tumour progression in lung cancer41. Furthermore, upon loss of epithelial monolayer integrity, α5β1 integrin becomes engaged by its specific adaptor protein zonula occludens 1 (ZO1)42, to drive directional cancer cell migration42 and alter the mechanical properties of α5β1 integrin–fibronectin links by increasing ligand recruitment but reducing resistance to force43. Integrins also facilitate tumour progression by promoting cancer cell stemness9 and/or by acting alone or in synergy with growth factor receptors (GFRs) to promote survival and growth signalling10,44,45,46,47,48,49. For example, in breast and lung cancer, increased αvβ3 integrin expression and downstream activation of SRC correlate with a cancer stem cell phenotype, anoikis resistance and increased metastasis50,51,52. In the case of growth factors, fibronectin binding to α5β1 integrin is sufficient to induce ligand-independent activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) MET53 while α6β4 integrin regulates MET oncogenic signalling49.

Cooperation between cancer cells and stromal cells

Cancer progression is not an isolated event of accumulating mutations and ensuing malignant traits in the primary tumour. Secreted factors from cancer cells profoundly alter the biology and composition of the underlying stroma by attracting immune cells, triggering angiogenesis and inducing CAF activation. These events result in numerous tumour-promoting signals from the tumour microenvironment (TME)20. In this Review, we focus specifically on modifications in the ECM such as stiffening (desmoplasia), owing to excess matrix protein deposition, and remodelling during cancer invasion. CAF activation is associated with alterations in integrin function, the actomyosin cytoskeleton and cellular mechanical properties21, which result in effective remodelling of the TME to support tumour progression. In addition, crosstalk between cancer cells, CAFs, immune cells and the vasculature is likely to be involved in generating an organ-specific, cancer-driven ECM, with substantial changes in ECM composition and topological structure54,55.

Under normal conditions, each tissue has a tightly regulated, specific optimal stiffness56, which is sensed by cells via integrins and the cytoskeleton. Thus, integrins are important mechanoreceptors and, in conjunction with other mechanoresponsive adhesome proteins such as the integrin-activating protein talin, vinculin and CRK-associated substrate (CAS; also known as BCAR1)57,58, convert mechanical signals into biochemical ones. Desmoplasia is common in many cancer types, including breast and pancreatic cancers, and facilitates cancer cell proliferation via multiple mechanisms, many of which are linked to integrins59. Increased stiffness correlates with higher β1 integrin activity in cancer cells, culminating in increased focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and RHOA–RHO-associated protein kinase (ROCK) signalling, two important pro-oncogenic elements in breast cancer60,61. In accordance, higher levels of β1 integrin, active FAK and active AKT are detected in invasive fronts and correlate with increased stiffness in experimental mouse breast cancer models and in invasive human breast cancer62. ECM stiffness supports cell proliferation by increasing, through direct or indirect epigenetic regulation, two transcriptional activators, nuclear yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ; also known as WWTR1), that operate in the Hippo pathway to induce the expression of pro-survival genes63,64,65. Mechanosensing by integrins and adhesion reinforcement by talin and vinculin support nuclear YAP localization66. The link between matrix rigidity, mechanosensing and nuclear YAP–TAZ is well established63,64,65. By contrast, the exact signalling pathways activating YAP–TAZ downstream of integrins in cancer are not fully understood and remain somewhat controversial. In sparse fibroblasts, cultured in the presence of serum, nuclear localization of YAP is integrin independent67, whereas in serum-starved breast epithelial MCF10A cells, fibronectin engagement appears to trigger nuclear YAP; additionally, in mammary fibroblasts, inhibition of αv integrins with the RGD peptide-based antagonist cilengitide inhibits YAP transcriptional activity68,69. Nevertheless, a requirement for SRC and/or FAK activity has been reported in numerous studies65,67,68,69,70, and a recent study unveiled a feedforward mechanism whereby increased cellular spreading via RHOA activates a YAP-dependent transcriptional programme upregulating genes encoding integrins and focal adhesion docking proteins71.

CAFs and their integrins contribute to generating a stiffer, altered ECM by promoting the secretion of ECM components such as collagen and fibronectin, and even more importantly by altering ECM architecture by adhering to the ECM and generating contractile forces to remodel the matrix. CAFs increase ECM stiffening by introducing increased crosslinking through the activity of lysyl oxidase (LOX) enzymes20,72. This is most likely linked to the integrins expressed on CAFs, given that several αv integrins activate TGFβ73, a known activator of LOX expression74, and that α2β1 integrin binding to collagen induces LOX expression75. Such a structurally altered ECM is sensed by cancer cells and facilitates their growth by promoting gene transcription and signalling65,76.

Cancer cell migration and invasion

As the principal receptors for ECM molecules, integrins are critically important in regulating cell motility in normal physiological processes, such as development and wound healing77, and during cancer dissemination. The major emphasis of research into cancer cell migration has been on the pursuit of understanding cancer cell invasion and metastasis. However, increased cell motility could also be an important contributor to tumour growth, as demonstrated by mathematical simulations coupling cell proliferation to cell motility78. Tumours with non-motile cells undergo rapid growth inhibition owing to steric hindrance and crowding, whereas local cell dispersal allows tumours to expand and reach higher growth rates78. The molecular and biomechanical details of cell movement in 2D in vitro settings are well defined, in which integrin-mediated ECM contacts function as so-called molecular clutches that propel the cell forward by converting actin polymerization at the protruding plasma membrane into traction force79,80,81. However, owing to the complexity of the 3D in vivo microenvironment, the dynamic interplay between different cells and the unique features (for example, genomic profile, tumour origin, environment and tumour heterogeneity) of each cancer type, the mechanisms governing cancer cell motility in vivo remain much more poorly understood. What is evident is that cancer cell migration is characterized by remarkable plasticity and crosstalk between integrins, other cell adhesion receptors and the actin cytoskeleton.

Altered ECM guides migration and invasion

In addition to providing a stiffer microenvironment that favours cancer progression, the cancer-associated ECM is a rich source of other pro-migratory and pro-invasive cues. Second-harmonic generation microscopy analysis, which detects fibrillar collagen structures, in mouse breast tumour models suggests that collagen reorganization at the tumour–stromal interface is a relevant parameter for predicting breast cancer dissemination82. In addition, elevated collagen deposition in the ECM augments tumour-progressive signals, intravasation and metastasis of oestrogen receptor-α (ERα)-positive mouse mammary tumour cells injected into the mammary fat pads of recipient mice83. These findings are not restricted to breast cancer. In pancreatic adenocarcinoma, a highly fibrotic cancer type, increased collagen alignment promotes cancer cell migration and serves as a negative prognostic factor84,85. Moreover, the thickness of collagen fibres in the tumour stroma also appears to be linked to survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)86. Accordingly, in KRAS-driven mouse models of PDAC with constitutively active β1 integrin and deletion of epithelial TGFβ signalling, tumour progression is accelerated and correlates with increased deposition of thick collagen fibres and tissue tension86. In fact, altered collagen deposition, which is presumably mediated by collagen-binding integrins and contractility of stromal cells, may be a general hallmark of poor prognosis in cancer. Recent work analysing collagen fibre structure within the tumour stroma of head and neck, oesophageal and colorectal cancers suggests a significant correlation between activated myofibroblasts, collagen fibre elongation and poor survival in all three cancer types87. However, in the microenvironment of the brain, which is poor in ECM, the presence of collagen fibres has been associated with better survival of patients with glioblastoma88.

In addition to contraction and remodelling of the existing collagen stroma to promote cancer cell invasion, CAFs have been shown to drive invasion by depositing fibronectin in an αvβ3 integrin-dependent manner in colon cancer21. In this context, contractile forces exerted by CAFs are insufficient to promote invasion in the absence of a fibronectin network21. Another fibronectin receptor, α5β1 integrin, has also been reported to play a role in pro-migratory fibronectin alignment by CAFs22. In addition, cancer-specific intracellular-binding partners of α5β1 integrin can also promote cell invasion by sensitizing cancer cells to changes in ECM composition. Coupling of α5β1 integrin to the pro-metastatic isoform of the actin-regulatory protein mammalian enabled homologue (MENA; also known as ENAH), termed MENA(INV), which is frequently reported to be highly expressed in invasive breast cancer cells, supports α5β1 integrin ‘outside-in’ signalling to FAK89 (Box 1) and tumour cell haptotaxis towards high fibronectin concentrations such as those typically seen in the perivascular space and in the periphery of breast tumour tissues90.

Recently, pharmacological inhibition or RNAi-mediated or genetic knockout of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an important metabolic sensor, was shown to trigger elevated integrin activity and fibronectin matrix deposition in normal fibroblasts by increasing tensin expression and the formation of α5β1 integrin–tensin complexes91,92. While the link between AMPK activity and fibronectin deposition in CAFs remains to be fully explored, AMPK activation with metformin, a widely used anti-diabetic drug, has been demonstrated to reduce desmoplasia and tumour growth in a PDAC mouse model93. Furthermore, in contrast to the well-established link between talin-induced integrin activation and mechanoresponsive growth signalling to YAP66,67,68,69,70,71, the relevance of tensins as integrin activators in cancer cells remains to be investigated, and their possible implication in mechanotransduction is not known.

Integrin involvement in different modes of migration in cancer

Cancer cell invasion involves complex crosstalk between distinct receptor systems. In addition to integrin–ECM contacts, cancers, in particular, invasive carcinomas, exhibit different degrees of cell–cell contacts, perhaps reflecting the various modes of cell migration observed in vivo (which range from integrin-mediated single-cell motility to collective cell migration as sheets or strands)94,95. A substantial body of evidence has linked EMT, loss of E-cadherin-mediated adherens junctions and increased integrin-mediated adhesions to dissemination of individual cancer cells96. However, in collectively migrating carcinomas, invasion is a delicate balance between cell–cell and cell–ECM adhesions and requires crosstalk between junctional proteins and proteins regulating integrin–ECM adhesions. For example, in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), both loss of E-cadherin at cell–cell adhesions97 and overexpression of E-cadherin, which normally localizes to cell–cell junctions, have been reported to inhibit collective migration and invasion98. Furthermore, cell–ECM adhesions are coupled to cell–cell adhesions via multiple distinct crosstalk pathways98,99. Integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin triggers a negative feedback signal that hinders the formation of E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesions100. Reintroduction of β1 integrin to β1 integrin-null epithelial cells triggers loss of cell–cell contacts and scattering of individual cells in a manner dependent upon β1 integrin activity and ligand binding101, and this result is indicative of an inhibitory role for integrin–ECM adhesions in the regulation of cell–cell junctions. Accordingly, integrin outside-in signalling can disrupt cell–cell adhesion by increasing actomyosin contractility102 and by influencing E-cadherin junctional stability through FAK and SRC signalling. In addition, SRC activity induces E-cadherin endocytosis to destabilize adherens junctions98. While the extent of crosstalk between integrins and cell–cell junctions is likely to be influenced by the cell type and the local TME, it is clear that this interdependence is an important regulator of the apparent plasticity of cancer cell migration and invasion in vivo.

In individually migrating cells, integrins are associated with another switch between migration modes. Particularly evident in melanoma, cells in a 3D ECM can switch between integrin-dependent mesenchymal migration and integrin-independent amoeboid migration103 (reviewed in refs104,105). The latter is driven by strong actomyosin contractility and can be induced in cells that normally adopt the mesenchymal migration mode by global inhibition of integrins and matrix-degrading proteases104,105. Alternatively, amplification of MET can trigger strong activation of RHO signalling and integrin internalization, resulting in amoeboid cell morphology in gastric cancer47.

Integrin transport and invasion

Integrin traffic is an important mechanism contributing to dynamic adhesion turnover, actin remodelling and membrane protrusion and is therefore central to the process of cell migration15. Interestingly, trafficking of integrin heterodimers with overlapping ligand specificity, such as α5β1 integrin and αvβ3 integrin that both bind fibronectin, can trigger very different cell motility outcomes. It is well established that preferential recycling of αvβ3 integrin over α5β1 integrin triggers directional cell migration in 2D, whereas increased α5β1 integrin recycling drives random cell motility in 2D and correlates with increased 3D invasion14,106. Interestingly, retrograde transport of inactive, non-ligand-bound β1 integrin heterodimers, but not β3 integrins, from the plasma membrane to the Golgi, followed by polarized delivery of the receptor to the cell front, has been linked to persistent cell migration in normal epithelial cells107. However, this pathway remains to be validated in other cell types, and its role in directional motility of cancer cells has not been studied. These examples highlight an antagonistic relationship between α5β1 integrin and αvβ3 integrin heterodimers during cell migration in 2D that may also be reliant on receptor activation state.

The identification of an α-integrin subunit-specific clathrin-adaptor-binding motif in a subset of α-integrin subunits, including α2 integrin, α3 integrin and α6 integrin108, which have been reported to have both cancer-inhibiting and cancer-promoting roles (that is, such roles have been identified for α2β1 integrin, α3β1 integrin and α6 integrin pairs31,54), could provide a mechanism for regulating the trafficking of these receptors independently of other α-integrin–β1 integrin pairs that bind to the same ligand and possibly explain some of the context-dependent and cell type-specific behaviour of these integrins in cancer.

Integrin-heterodimer-specific trafficking has already been linked to cancer cell migration and invasion. Among the genetic mutations prevalent in human cancer, mutant p53 expression is strongly linked to increased invasion and metastasis109,110,111. Interestingly, gain-of-function p53 mutant proteins increase α5β1 integrin recycling, which, in turn, is linked to generation of RHO-driven invasive cellular protrusions in a fibronectin-rich 3D microenvironment106. Furthermore, mutant p53-mediated α5β1 integrin recycling has been demonstrated to promote actin-related protein 2/3 (ARP2/3) complex-independent ovarian cancer cell invasion in vivo, a process that is regulated by the formation of FH1/FH2 domain-containing protein 3 (FHOD3)-dependent filopodia-like protrusions112. In addition, mutant p53 increases the expression of the non-conventional myosin motor myosin X113, which binds directly to integrin and transports it to filopodia tips114. Thus, mutant-p53-driven integrin recycling and overexpression of an integrin-transporting motor protein could synergistically facilitate cancer cell invasion. In concordance, high levels of myosin X correlate with poor prognosis in cohorts of patients with breast cancer and with metastasis in mouse models of the disease113,115.

Integrins sense both chemical and physical properties of the ECM, and cells can dynamically increase the affinity of integrins for their ligands. For example, integrin-mediated adhesion at filopodia tips and filopodia formation in breast cancer cells are influenced by matrix composition116. In addition, integrin activation at filopodia tips is critical for filopodia stabilization and for the capacity to direct focal adhesion maturation via a mechanism involving voltage-dependent calcium channels and integrin downstream signalling117. Integrins are also important components of invasive structures called invadopodia or invadosomes found in cancer cells in 2D118,119. While the existence of invadopodia in 3D remains somewhat debated, numerous studies have linked increased numbers of invadopodia-like structures with increased ECM degradation and invasive capacity in 3D and in vivo120.

Giving rise to metastasis

A major challenge for cancer cells, and possibly the most critical step in cancer progression, is survival within the vasculature for long enough to home to a distant site that permits dissemination. Here, we focus on highlighting recently emerged integrin functions in this step.

Integrin endosomal signalling in cancer cell survival and anoikis suppression

Classically, integrins and their cancer-regulatory functions have been considered to be restricted to the plasma membrane and to signalling from focal adhesions. However, recent studies have challenged these views and identified novel mechanisms of integrins promoting anchorage-independent survival and metastasis in unconventional ways (Fig. 2). Even though the exact trigger for endocytosis of active integrins is unknown, one hypothesis has been that, upon matrix degradation, loss of ECM tension enables uptake of active integrins bound to ligand fragments. In accordance, active integrins and ECM ligands like fibronectin are readily detected in endosomes in cancer cells121,122. Importantly, active FAK localizes to active β1 integrin-positive endosomes45,123, and at least in reconstituted systems, integrin-containing endosomes have the capacity to recruit and activate FAK on endomembranes45. In adherent cells, FAK activity on endosomes maintains integrin activity by facilitating talin 1 recruitment to endosomes123. In normal detached cells, endosomal integrin signalling prolongs FAK activity and in breast cancer cells supports anchorage-independent growth and metastasis45.

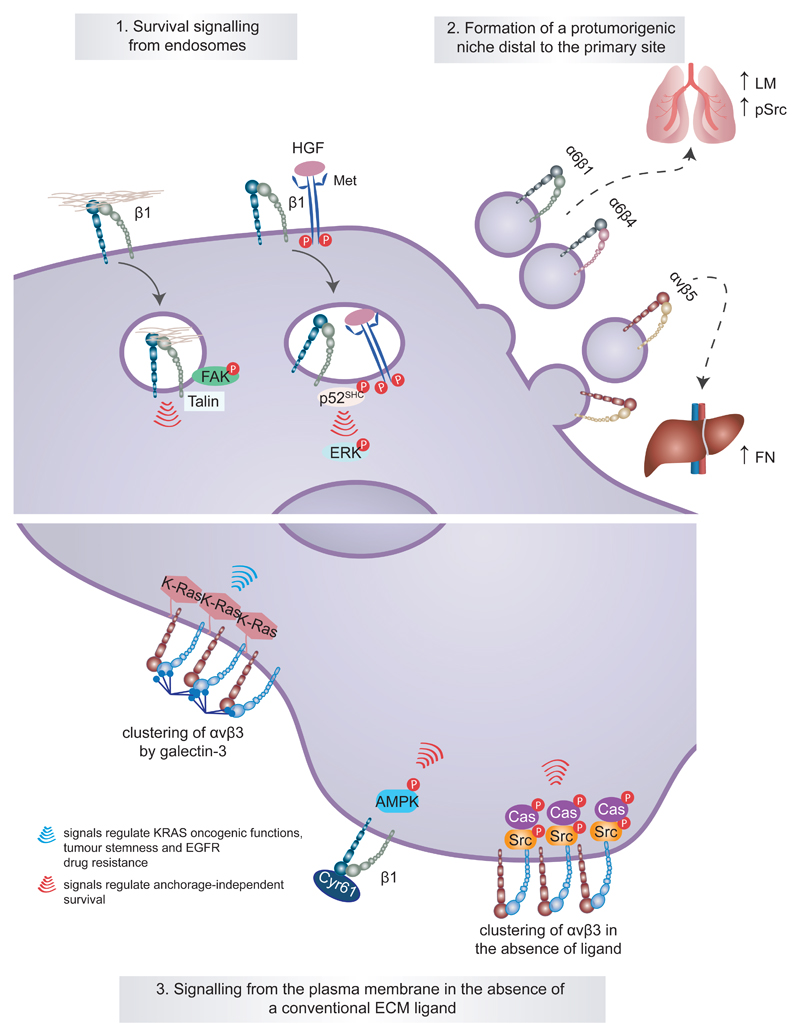

Fig. 2. Unconventional integrin signalling contributes to cancer cell survival, stemness and drug resistance.

Classical integrin signalling has been described to be restricted to the plasma membrane and to require intact integrin–extracellular matrix (ECM) ligand engagement. However, it is now clear that unconventional modes of integrin signalling exist and contribute to cancer cell survival and disease progression. For example, active integrin signalling has been shown to be maintained away from the plasma membrane following integrin endocytosis in the presence of an ECM ligand or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-stimulated receptor tyrosine kinase MET and to contribute to anchorage-independent growth and survival of cancer cells through different pathways (part 1). A more extreme example of long-range integrin signalling has been illustrated in tumour exosomes and is associated with disease advancement. Tumour exosomal α6β1 integrin and α6β4 integrin appear to target metastatic cells to the lung, whereas exosomal αvβ5 integrin is linked to liver metastasis. At these defined sites, the exosomes prepare a premetastatic niche by triggering the expression of specific ECM components (higher laminin and elevated SRC phosphorylation (pSRC) in lung fibroblasts and elevated fibronectin in the liver) and pro-inflammatory S100 proteins in the target tissue (part 2). Integrin signalling from the plasma membrane can also be unconventional and occur in the absence of an ECM ligand or be promoted by the interaction of non-structural ECM proteins such as galectin 3 and cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61) with the integrin extracellular domains (part 3). AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CAS, CRK-associated substrate; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; P, phosphorylation; p52-SHC, p52 isoform of SHC-transforming protein 1.

Integrins can also function in a ligand-independent manner to support cell survival in suspension and prolong oncogenic signalling. Activation of MET by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) induces co-endocytosis of MET and β1 integrins44,47. Unexpectedly, the β1 integrin within these MET-containing endosomes is maintained in an active conformation, even in the absence of ECM ligands, and in this active form it supports prolonged MET signalling from the p52 isoform of SHC-transforming protein 1 (p52-SHC) to ERK44. This integrin–MET ‘inside-in’ signalling is necessary for oncogenic MET to drive anchorage-independent growth and metastasis in a mouse model using NIH-3T3 fibroblasts overexpressing mutant MET44 (Fig. 2 and Box 1). Even more unexpectedly, a recent study suggested that MET displaces α5 integrin from β1 integrin to form a MET–β1 integrin complex in breast cancer and glioblastoma, particularly in therapy-resistant invasive glioblastomas124. It is currently unclear whether this unorthodox integrin heterodimer is implicated in the previously reported requirement for a functional β1 integrin in MET-driven oncogenic signalling44. Nevertheless, the multiple reported links between β1 integrin and β4 integrin and oncogenic MET signalling44,47,49,53,125 suggest that targeting these integrins would provide some benefit in treating MET-dependent carcinomas.

While the biology and cancer relevance of integrin endosomal signalling alone or in conjunction with GFRs remain to be studied in detail in relevant in vivo models, the role of integrins in anoikis resistance via other mechanisms is well established. ECM-induced integrin outside-in signalling entails ligand engagement and receptor clustering (Box 1). In non-anchored cells, clustering of most integrins on the plasma membrane by ECM molecules is lost. Furthermore, in the absence of matrix adhesion, clustering of other receptors like epidermal GFR (EGFR) is also reduced126. In normal cells, such events are sufficient to trigger anoikis. However, upregulation of specific integrins can confer anoikis resistance. αvβ3 integrin has the unique ability to maintain receptor clustering in non-adherent cells51. This enables αvβ3 integrin to confer anoikis resistance to cancer cells by recruiting SRC to the β3 integrin subunit cytoplasmic tail, leading to SRC activation, CAS phosphorylation and cell survival51. Interestingly, in contrast to the anoikis resistance induced by endosomal signalling of β1 integrins, this αvβ3 integrin-mediated anoikis resistance mechanism appears independent of FAK activation51(Fig. 2.)

In addition, there are reports suggesting that integrins can also provide anoikis resistance by binding to non-structural ECM components. Members of the CCN family of matricellular proteins, including cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), harbour several binding sites for integrins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans and are secreted by cancer cells and stromal cells into the TME127. Elevated CYR61 levels are correlated with a more advanced phenotype in breast cancer128. In triple-negative breast cancer cell lines, CYR61 supports metastasis and attenuates anoikis by activating β1 integrins and AMPK signalling independently of AKT, FAK and ERK1 and/or ERK2 activation129. Secreted galectin 3 is a carbohydrate-binding protein that promotes integrin endocytosis in adherent cells by interacting with N-glycans on the integrin extracellular domains130. By contrast, galectin 3 mediates anchorage-independent clustering of αvβ3 integrin, giving rise to membrane-proximal KRAS clustering, which enables numerous oncogenic functions of activated KRAS, including macropinocytosis131, cancer cell stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibitors132(Fig. 2). Galectin 3–αvβ3 integrin clustering was recently described as an underlying mechanism driving KRAS addiction in tumour cells, and inhibition of galectin 3 was identified as a potential strategy to target KRAS-addicted (KRAS-G12D mutant) lung and pancreatic cancers133. Oncogenic KRAS (KRAS-G12V) can also induce anoikis resistance in normal kidney epithelial cells by increasing α6 integrin expression. When coupled to ectopic overexpression of αv integrins, the KRAS–α6 integrin–αv integrin axis was sufficient to transform these cells into a highly invasive phenotype characterized by EMT-like features in vitro134.

Integrins and priming the metastatic niche

Exosomes, the small membrane-bound vesicles actively shed by both normal and cancerous cells135, regulate cell–cell communication by horizontal transfer of RNAs and proteins136. Integrins are the most highly expressed receptors on the surface of exosomes and were recently shown to have a functional role in guiding exosomes to particular tissue sites to act as ‘primers’ of the metastatic niche (Fig. 2) and support the propensity of different cancer types to metastasize to specific organs137. In particular, lung-tropic cancer cells were found to secrete exosomes rich in α6β1 integrins and α6β4 integrins, whereas liver-tropic cancer cells shed predominantly αvβ5 integrin-positive exosomes. When isolated from cancer cells and injected into mice, the biodistribution of these exosomes was found to match the organotropic dissemination of the cell line of origin. Furthermore, exosome uptake by resident cells within the target tissue was suggested to prime the distant site in support of cancer cell survival by triggering the expression of specific ECM components and pro-inflammatory S100 proteins137 (Fig. 2). However, the general applicability of this mechanism in cancer metastasis remains to be validated in vivo for other models of metastasis and for other cancer types.

Integrins in extravasation

For enduring CTCs, the next critical step in metastasis is extravasation, and this is dependent on multiple factors. For example, the permeability and integrity of the vascular endothelium determine the rate of extravasation in many organs. Several mechanisms involving platelet-released ATP, inflammatory mediators and cancer cell-secreted growth factors and proteases have been implicated in the regulation of capillary wall permeability24. Integrin expression both on cancer cells and on endothelial cells has also been implicated in extravasation (Fig. 3). Endothelial cells use integrins to interact with their underlying basement membrane. These cell–ECM contacts combined with protein tyrosine kinase-induced signalling are important regulators of vessel integrity138. In cancer, increased angiopoietin 2 (ANG2) signalling in endothelial cells, in conjunction with reduced levels of the angiopoietin receptor TIE2 (also known as TEK), increases vascular permeability, and ANG2 blocking antibodies can inhibit metastasis138,139. In the absence of TIE2, ANG2 interacts with α5β1 integrin, triggering integrin receptor activation and translocation to fibrillar adhesions, which results in compromised vascular integrity140. In addition, endothelial α5 integrin contributes to extravasation by directly interacting with neuropilin 2 (NRP2), a multifunctional non-kinase receptor for multiple growth factors expressed on cancer cells141. The NRP2–α5 integrin trans-interaction facilitates cancer cell binding to the endothelium and mediates vascular extravasation in zebrafish and mouse xenograft models of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma141. Thus, endothelial α5 integrin expression is likely to be associated with the strong clinical correlation between elevated NRP2 levels and metastasis in osteosarcoma and breast cancer142,143.

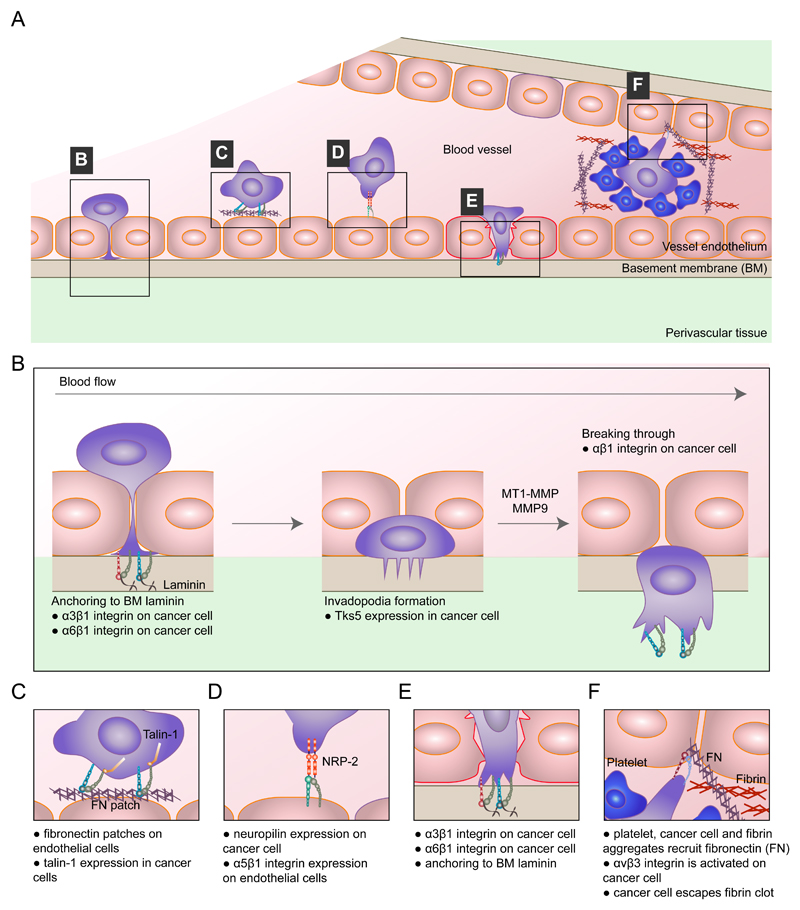

Fig. 3. Integrins in extravasation.

The top panel shows a schematic of integrin-mediated extravasation of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) (part a). The mechanisms involved in this process are α3β1 integrin-mediated and α6β1 integrin-mediated cancer cell adhesion to subendothelial laminin, which is required for successful transendothelial migration. β1 integrin is also a prerequisite for tumour cells to fully clear the endothelial layer and invade into the basement membrane (part b). The presence of fibronectin patches on endothelial cells promotes cancer cell adhesion to the vessel wall in a manner dependent on the integrin activator talin 1 (part c). Endothelial cells also express integrins. Endothelial α5 integrin directly binds to neuropilin 2 (NRP2), a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the semaphorin family of proteins, on cancer cells, and this interaction promotes cancer cell attachment to the endothelium and subsequent extravasation (part d). Pre-existing patches of exposed basement membrane can promote CTC arrest on the vascular wall in a mechanism whereby exposed laminin is engaged by α3β1 integrin on the tumour cell (part e). Features of the blood clotting cascade can promote integrin-mediated cancer cell invasive protrusion and extravasation, such as local recruitment of plasma fibronectin to trigger αvβ3 integrin activation (part f). MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MT1, membrane type 1; TKS5, tyrosine kinase substrate with five SH3 domains (also known as SH3PXD2A).

The requirement for integrins in extravasation and metastasis is likely to be dependent on the cancer cell type and tissue-specific features. For instance, the presence of integrin-dependent myosin X-induced filopodia in breast cancer cells correlates with the degree of extravasation in the lung113. In another example of direct integrin-mediated regulation of cancer cell–endothelium interactions at the step of extravasation, pre-existing patches of exposed basement membrane in the pulmonary vasculature regulate CTC arrest144 as laminin, a basement membrane component, is engaged by α3β1 integrin on the tumour cell144. In addition, the blood clotting cascade is selectively involved in lung metastasis and associated with integrin activation27,28. Here, aggregates of platelets, fibrin and carcinoma cells support local recruitment of plasma fibronectin. The ensuing fibrin–fibronectin complexes induce αvβ3 integrin activation, triggering invasive protrusions and pro-invasive EMT signalling in the cancer cells27,28.

Within the fenestrated endothelium of bone marrow and liver, which are regions that are more permissive to CTC entry, direct integrin-mediated interactions or active transendothelial migration may be less prominent approaches for extravasation. However, recent data from primary tumour-bearing mice and tissue from human colon cancer metastases show that the luminal side of liver blood vessels is enriched in fibronectin deposits145. CTCs adhere to these endothelial fibronectin patches, and this tethering requires talin 1 (ref.145) and presumably integrins, although this remains to be formally investigated. In the brain, CTCs need to cross the blood–brain barrier, the integrity of which may be compromised in patients with cancer146. Currently, there is no clear understanding of how, or whether, integrins contribute to cancer cell extravasation to the brain owing to the challenge of directly assessing the blood–brain barrier. However, at least in model systems, certain integrin profiles have been shown to influence tropism of breast cancer cell metastases to the brain147.

Inhibition of β1 integrin significantly reduces the formation of metastatic foci of several cancer types, including breast cancer148 and PDAC149. However, the specific metastatic steps regulated by β1 integrin remain unclear and are likely to be context dependent. Human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells injected into the vasculature of zebrafish embryos were found to adhere to the intraluminal vessel wall via β1 integrins, migrate along the vessel and undergo β1 integrin-dependent transendothelial migration by inducing remodelling of the vascular endothelium, including cell–cell junctions150. Furthermore, transcriptional upregulation of β1 integrin expression by CDC42 and serum response factor (SRF) has been linked to cancer cell interaction with endothelial cells and transendothelial migration151. A more detailed insight into the role of tumour β1 integrin in extravasation was obtained using an in vitro model of microvasculature152. β1 integrin-mediated adhesion and activation were essential to stabilize the initial contacts made by the tip of the leading protrusion of the cancer cell with the subendothelial matrix. In addition, β1 integrin was necessary for the cancer cells to invade through the basement membrane after clearing the endothelial barrier152. These findings, which are supportive of integrin activation playing a key role in extravasation, are in line with the finding that expression of activated mutants of β1 integrin in cancer cells intravenously injected into chick embryos and mice increases metastatic colonization of the liver153.

Regulators of integrin activity have also been implicated in metastasis. Gene expression profiling of CTCs derived from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer has revealed high expression of known integrin binding partners such as talin 1, vinculin and kindlin 3 (also known as FERMT3)154. Specifically, talin 1 functionally contributes to the extravasation and metastasis of colon cancer CTCs145, while talin 1 overexpression has been shown to correlate with aggressiveness in oral SCC and contribute to anoikis suppression during prostate cancer metastasis155,156. Kindlin 1 (also known as FERMT1) is elevated in cancer types with a propensity to metastasize to the lungs, such as breast cancer; this finding has led to the suggestion that kindlin 1 is a prognostic factor for lung metastasis157,158. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of kindlin 1 in breast cancer cells has been shown to suppress primary tumour growth and lung metastasis in vivo157, while genetic deletion of kindlin 1 in mice impaired α4 integrin-mediated pulmonary arrest of disseminating mammary tumour cells158. Therefore, mounting evidence suggests that increased integrin activity in cancer cells or endothelial cells is coupled to extravasation.

Integrins in dormancy

Successfully extravasated cancer cells may lack the necessary growth-promoting signals in their new tissue environment and thus enter a dormant state. Links between integrins and the ECM play an important role in regulating cancer cell dormancy. Fibronectin secretion, activation of cytoskeletal contractility downstream of β1 integrins159 and activation of FAK in response to integrin-mediated adhesion160 have all been associated with integrin-induced exit of cancer cells from dormancy. During lung metastasis, the proliferation of cancer cells was induced by the formation of β1 integrin-containing, actin-rich, filopodia-like protrusions. These protrusions were generated by the cooperative action of two formin family members, namely, RAP1-interacting factor (RIF) and MDIA2 (also known as DIAPH3)161, which induce actin nucleation and subsequent elongation of actin filaments162 and were critical for the activation of FAK to overcome dormancy163. In addition, integrin downstream signalling functioned as a positive feedback mechanism to sustain signalling pathways involving integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and β-parvin, two integrin–actin-bridging proteins, prolonging the lifetime of the filopodia161.

Integrins in anticancer therapy

In addition to being implicated in nearly every step of the metastatic cascade, integrin-mediated pathways are often connected to the development of drug resistance10,132,164,165,166. In mouse mammary tumour models, increased collagen levels and increased β1 integrin and SRC activity have been demonstrated to accompany, and promote, combined resistance to anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2: also known as ERBB2) (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) and anti-PI3K (buparlisib) therapies164. In lung cancer, β1 integrin–SRC–AKT signalling has been proposed as a key mediator of acquired resistance to EGFR-targeted anticancer drugs167, while a β1 integrin–FAK–cortactin signalling nexus has been described as a mechanism reducing head and neck SCC sensitivity to radiotherapy168. αvβ3 integrin is a putative marker of breast, lung and pancreatic carcinomas with stem-like properties and high resistance to RTK inhibitors9,132. Recently, paradoxical activation of melanoma-associated fibroblasts by a BRAF inhibitor (PLX4720), which leads to stromal matrix stiffening and elevated β1 integrin–SRC–FAK signalling in melanoma cells, was demonstrated to promote PLX4720 resistance169.

As such, integrins are considered to be attractive drug targets, a concept that is bolstered by the accessibility of their crucial cell surface-exposed ligand binding and regulatory sites to therapeutic intervention; however, despite largely encouraging preclinical studies, ensuing successful clinical trials based on current methodologies are, regrettably, few in number. For example, several in vitro and preclinical studies have indicated that integrin inhibition would be efficient at sensitizing breast cancer170,171 and glioblastoma to radiotherapy172,173. However, cilengitide, a selective αvβ3 integrin and αvβ5 integrin inhibitor, in combination with standard of care (radiotherapy with the chemotherapy temozolomide), failed to improve survival of patients with glioblastoma in an open-label phase III trial, the CENTRIC EORTC 26071–22072 study, and in a companion phase II trial, the CORE study, and therefore, further development of this drug was discontinued for treatment of glioblastoma174,175,176. The recent POSEIDON trial, combining abituzumab, a humanized αv integrin-specific antibody, with the standard of care, showed no improvement in progression-free survival of patients with wild-type-KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer compared with the standard of care alone177; however, the data did suggest some improvement in patients with high αvβ6 integrin expression177, a preliminary observation that needs to be verified in trials in which αvβ6 integrin expression is used to stratify the patient cohort.

Notably, most current therapeutic strategies, including cilengitide and abituzumab, have been primarily designed to interfere with integrin–ligand interactions. Considering the breadth of new evidence describing ECM ligand-independent integrin signalling in cancer cell survival and drug resistance44,51,129,132, there may be a need to develop alternative strategies that exploit tumour-specific integrin expression profiles (Box 2) or downstream integrin effectors rather than focusing directly on targeting the integrin receptors themselves. Moreover, switching between integrin heterodimers in cancer12,14 may be one mechanism whereby tumour cells evade therapy12 and may explain the lack of efficacy of specific integrin heterodimer inhibitors.

Box 2. A second chance for integrin-targeting agents in cancer therapy?

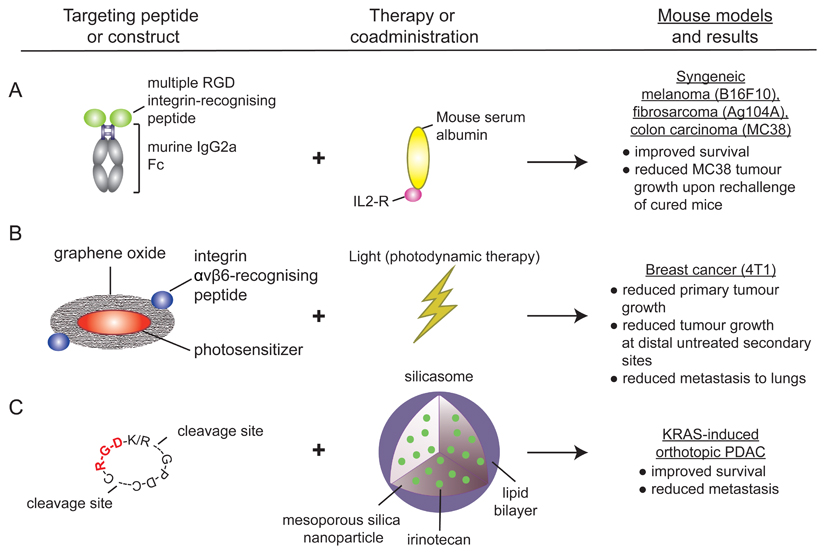

The identification of Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif-binding α5β1 integrin and αv integrin expression in the tumour vasculature, combined with their important roles in vascular biology and angiogenesis207, initiated the development of RGD peptide-specific antagonists, as potential anti-angiogenic cancer therapies185, and imaging tracers199,200,201. However, the success of integrin antagonists in preclinical cancer models has not been reflected in clinical settings11, calling for alternative strategies to target integrin function.

New studies are now exploiting RGD integrins not in their capacity as extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion molecules but rather as validated tumour-associated antigens to selectively deliver antitumour agents (see the figure). Recent successes of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which were developed to induce T cell antitumour activity, have prompted a wide interest towards cancer immunotherapy208. In a recent study, a highly specific RGD integrin imaging peptide fused to the Fc-domain of immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) was used to direct antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity209. This peptide, when administered alongside an interleukin-2 (IL-2) fusion protein, was shown to promote CD8+ T cell and natural killer cell activation and was demonstrated to significantly improve survival in preclinical models of melanoma, colorectal cancer and fibrosarcoma. The observed efficacy was attributed to efficient recruitment of host immune cells to the tumours, rather than through any antagonism of integrin function209 (see the figure, part a). Another study exploited an αvβ6 integrin-specific peptide to generate a tumour-targeted photosensitizer, which, when used in photodynamic therapy resulted in effective ablation of primary lung tumours in mouse models. The resulting necrotic tumour cells triggered dendritic cell activation and a CD8+ T cell response to destroy residual tumour cells and suppress tumour relapse210 (see the figure, part b).

Others have shown that co-administration of an internalized RGD (iRGD) peptide with affinity for both RGD integrins and neuropilin 1 (NRP1) increases cellular uptake via NRP1 of silicasome carriers loaded with the chemotherapeutic drug irinotecan, resulting in improved survival and markedly reduced metastasis in a pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) mouse model211 (see the figure, part c). In another example, the potential for redesigning replication-selective oncolytic adenoviruses to include expression of an αvβ6 integrin-specific peptide to specifically target cancer cells has been demonstrated in a PDAC mouse model212.

FAK is a typical example of a protein that is highly phosphorylated in response to integrin activation and has diverse cellular functions (for example, cell proliferation, adhesion and migration) that impinge on tumour cell behaviour178,179,180. FAK has been identified as a key player in the resistance to anoikis45,178,179,180 and in maintaining an immunosuppressive TME181,182. Currently, FAK inhibitors in combination therapy are under phase I/II safety and pharmacokinetics evaluation for treatment of advanced solid cancers (NCT02428270, a phase II trial using a FAK inhibitor in combination with a MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor183 and NCT02546531, a phase I trial using a FAK inhibitor in combination with a humanized antibody targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) and chemotherapy184); however, whether these have true potential as single or combinatorial therapies remains to be seen. The interpretation of results from these clinical trials is likely to be complicated, in particular, by new insights into cancer-specific roles of FAK distinct from those associated with its classical subcellular localization at the plasma membrane. In SCC, FAK activity in the nucleus has been linked to transcriptional regulation of chemokine and cytokine networks to promote tumour evasion from immune cells182 and to cell cycle progression to support tumour growth185. It is currently unclear whether integrin signalling plays a role in nuclear FAK activity, how FAK is translocated to the nucleus and whether FAK-dependent transcription of immunomodulatory genes also occurs in other cancer types. This latter point is particularly interesting, as in pancreatic cancer, FAK inhibition has been shown to increase immune cell infiltration into the TME and to sensitize tumours to immune checkpoint therapy181.

An emerging theme in integrin research is the ability of these receptors to modulate the tumour-associated stroma into an environment tolerating tumour growth and progression. This has potential therapeutic implications. For example, LOX-mediated matrix crosslinking, which is associated with matrix stiffening and tumour progression in several cancers186,187,188,189, increases integrin-dependent signalling in pancreatic cancer190 and drives SRC-dependent cell proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer191. Recently, inhibition of LOX was shown to dampen metastasis and to increase response to chemotherapy in a PDAC mouse model187. In this study, it was suggested that blocking integrin interaction with fibronectin (using an α5 integrin-blocking antibody) strengthens the negative effect of LOX inhibition on cell viability; however, this preliminary observation requires in-depth validation. It may also be interesting to dissect the potential relationship between integrins and LOX expression73,75 to further understand the mechanisms of action of LOX inhibitors.

Another therapeutically intriguing finding is the somewhat counterintuitive role of a bulky glycocalyx in inducing integrin signalling and cell survival in cancer. Mucins, such as mucin 1 (MUC1) and MUC16, are bulky cell surface glycoproteins frequently upregulated in epithelial cancers192. They extend far from the plasma membrane and sterically hinder integrin–ECM links. However, in parallel, they promote increased integrin clustering, downstream signalling and crosstalk with GFRs in areas in the cell membrane where ECM linkages are formed193. Importantly, MUC1 overexpression supports tumour growth and metastasis of melanoma xenografts in mice, and cells engineered to have a thick glycocalyx foster increased metastatic potential, most likely owing to increased integrin signalling194. Given the established role of mucins in tumour progression192, several strategies to target them therapeutically have been developed. Small molecule drugs that inhibit MUC1 cytoplasmic tail oligomerization (for example, GO-201) have shown promising results in human breast tumour and MUC1-expressing prostate cancer xenografts in mice195,196 and were found to be well tolerated in a phase I trial in patients with advanced solid tumours (NCT01279603 (ref.197)). In addition, drugs inhibiting the core mucin-synthesizing enzyme GCNT3, which lead to disrupted mucin production in vivo and in vitro198, have been described and may inhibit tumour growth either independently or in synergy with other drugs192.

In addition to being considered prominent drug targets, several integrins (for example, αvβ3 integrin, αvβ6 integrin and α5β1 integrin) are emerging as valuable probes in cancer imaging studies to determine both prognosis and treatment efficacy199,200,201. Clinical trials using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of integrin-binding tracers include an RGD peptide-containing αvβ3 integrin tracer to evaluate tumour burden and angiogenesis (NCT00565721 (ref.202)) and an αvβ6 integrin tracer to detect tumours and evaluate treatment response in patients with pancreatic cancer (NCT02683824 (ref.203)).

Conclusions

Decades of research into the biological functions of integrins in cancer have demonstrated a strikingly complex set of molecular mechanisms employed by these adhesion receptors in different steps of cancer progression. The importance of integrins as cellular mechanotransducers is becoming increasingly recognized, and integrins are understood to play critical roles in tumour progression, in which altered integrin function or expression contributes to both cancer cell behaviour and the biophysical and biochemical features of the TME. Integrins are also expressed by stromal cells and on tumour-derived exosomes, and in this way, they help to define the ECM deposited around primary tumours and in metastatic niches and further contribute to disease progression. Thus, targeting integrins in the tumour stroma may be an important avenue to explore when considering future therapeutic options. Integrins are also key players in metastasis owing to diverse roles in cell motility, the ability to facilitate intravasation and extravasation via multiple mechanisms and regulation of cancer cell survival in the circulation. Whole genome sequencing of clinical samples from an autopsy study of patients with metastatic prostate cancer has demonstrated that metastases seed further metastases and give rise to diverse therapy-resistant subclones204. Thus, inhibiting integrin-mediated seeding of cancer at any stage of the disease is likely to be beneficial for the patient.

Supplementary Material

Glossary.

Angiogenesis

A physiological process characterized by the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, which can be deregulated during disease to promote the spread of cancer cells.

Intravasation

The invasion of cancer cells through a basement membrane to enter blood or lymphatic vessels.

Extravasation

The movement of cells out of a blood vessel, which involves traversing an endothelial cell layer and basement membrane, into the surrounding tissue.

Anoikis

A specialized form of programmed cell death, which occurs upon loss of integrin-mediated adhesion to the extracellular matrix.

Thrombus

Also known as a blood clot, a structure that is the final result of blood coagulation. A thrombus consists of aggregated platelets and red blood cells and a mesh of crosslinked fibrin.

Desmoplasia

The growth of fibrous or connective tissue wherein resident cells produce excess fibrous matrix components such as collagen.

Mechanoreceptors

A term used to define receptors capable of receiving and translating mechanical cues from the environment.

Focal adhesion

Integrin-mediated cell–extracellular matrix contact that is connected to the actin cytoskeleton and acts as both a physical anchor and a signalling hub to regulate the cell’s response to extracellular cues.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) enzymes

Extracellular copper-dependent enzymes that act on lysine residues in collagen and elastin to promote crosslinking of these matrix molecules.

Haptotaxis

Directional cell migration on an extracellular matrix gradient towards higher matrix concentrations.

Filopodia

Actin-rich, finger-like membrane protrusions that extend out of the cell to probe the extracellular matrix.

Invadopodia

Actin-based membrane protrusions found in invasive carcinoma cells and associated with sites of extracellular matrix degradation.

Glycocalyx

Also known as the pericellular matrix, an external cell layer that contains a fibrous meshwork of carbohydrates (oligosaccharides, glycoproteins and mucins). This layer projects from the cell surface to cover the cell membrane in many animal cells and bacteria.

Photodynamic therapy

A medical treatment that uses a photosensitizing molecule (frequently a drug that becomes activated by light exposure) and a light source to activate the administered drug.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize to all colleagues whose work was not mentioned here owing to space limitations. The authors thank the Ivaska laboratory members for their constructive criticisms of this review and J. Marshall for insightful discussion and contributions to Supplementary Table 1. Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by funding from the Academy of Finland, a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation and the Cancer Society of Finland.

Footnotes

Contributions

J.I. researched the data for the article and wrote the body of the manuscript before submission. H.H. assembled the table, drafted the display items and contributed to writing of the manuscript before submission. J.I. and H.H. equally contributed to revising and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arruda Macêdo JK, Fox JW, de Souza Castro M. Disintegrins from snake venoms and their applications in cancer research and therapy. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2015;16:532–548. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150515125002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussein HAM, et al. Beyond RGD: virus interactions with integrins. Arch Virol. 2015;160:2669–2681. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2579-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Franceschi N, Hamidi H, Alanko J, Sahgal P, Ivaska J. Integrin traffic - the update. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:839–852. doi: 10.1242/jcs.161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton ER, et al. Definition of a consensus integrin adhesome and its dynamics during adhesion complex assembly and disassembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1577–1587. doi: 10.1038/ncb3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton ER, et al. The integrin adhesome network at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:4159–4163. doi: 10.1242/jcs.192054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaidel-Bar R, Itzkovitz S, Ma'ayan A, Iyengar R, Geiger B. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:858–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb0807-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winograd-Katz SE, Fässler R, Geiger B, Legate KR. The integrin adhesome: from genes and proteins to human disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:273–288. doi: 10.1038/nrm3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seguin L, Desgrosellier JS, Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Integrins and cancer: regulators of cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance. Trends in cell biology. 2015;25:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamidi H, Pietilä M, Ivaska J. The complexity of integrins in cancer and new scopes for therapeutic targeting. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1017–1023. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raab-Westphal S, Marshall JF, Goodman SL. Integrins as Therapeutic Targets: Successes and Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/cancers9090110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parvani JG, Galliher-Beckley AJ, Schiemann BJ, Schiemann WP. Targeted inactivation of β1 integrin induces β3 integrin switching, which drives breast cancer metastasis by TGF-β. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3449–3459. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Flier A, et al. Endothelial alpha5 and alphav integrins cooperate in remodeling of the vasculature during development. Development. 2010;137:2439–2449. doi: 10.1242/dev.049551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. alpha v beta3 and alpha5beta1 integrin recycling pathways dictate downstream Rho kinase signaling to regulate persistent cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:515–525. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul NR, Jacquemet G, Caswell PT. Endocytic Trafficking of Integrins in Cell Migration. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouvard D, Pouwels J, De Franceschi N, Ivaska J. Integrin inactivators: balancing cellular functions in vitro and in vivo. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:430–442. doi: 10.1038/nrm3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheldrake HM, Patterson LH. Strategies to inhibit tumor associated integrin receptors: rationale for dual and multi-antagonists. J Med Chem. 2014;57:6301–6315. doi: 10.1021/jm5000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munshi HG, Stack MS. Reciprocal interactions between adhesion receptor signaling and MMP regulation. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:45–56. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaggioli C, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attieh Y, Vignjevic DM. The hallmarks of CAFs in cancer invasion. Eur J Cell Biol. 2016;95:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attieh Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts lead tumor invasion through integrin-β3-dependent fibronectin assembly. J Cell Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201702033. [This article demonstrates that cancer cell invasion requires not only CAF-mediated contractility of the matrix but also CAF-dependent remodelling of fibronectin by integrin αvβ3.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdogan B, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote directional cancer cell migration by aligning fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201704053. [This study describes a mechanism whereby CAFs align fibronectin fibres within the tumour ECM and, through application of traction forces mediated by integrin α5β1, promote directional cancer cell migration.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labernadie A, et al. A mechanically active heterotypic E-cadherin/N-cadherin adhesion enables fibroblasts to drive cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:224–237. doi: 10.1038/ncb3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert AW, Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Emerging Biological Principles of Metastasis. Cell. 2017;168:670–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui PY. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strilic B, Offermanns S. Intravascular Survival and Extravasation of Tumor Cells. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:282–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knowles LM, et al. Integrin αvβ3 and fibronectin upregulate Slug in cancer cells to promote clot invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6175–6184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0602. [The authors in this study connect increased fibronectin and active integrin αvβ3 expression to upregulation of SLUG, EMT and fibrin invasion as a mechanism selectively involved in lung metastasis. ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malik G, et al. Plasma fibronectin promotes lung metastasis by contributions to fibrin clots and tumor cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4327–4334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cagnet S, et al. Signaling events mediated by α3β1 integrin are essential for mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2014;33:4286–4295. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White DE, et al. Targeted disruption of beta1-integrin in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer reveals an essential role in mammary tumor induction. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramirez NE, et al. The α2β1 integrin is a metastasis suppressor in mouse models and human cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:226–237. doi: 10.1172/JCI42328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramovs V, Te Molder L, Sonnenberg A. The opposing roles of laminin-binding integrins in cancer. Matrix Biol. 2017;57–58:213–243. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludlow A, et al. Characterization of integrin beta6 and thrombospondin-1 double-null mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:421–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore KM, et al. Therapeutic targeting of integrin αvβ6 in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Truong HH, et al. β1 integrin inhibition elicits a prometastatic switch through the TGFβ-miR-200-ZEB network in E-cadherin-positive triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed N, et al. Overexpression of alpha(v)beta6 integrin in serous epithelial ovarian cancer regulates extracellular matrix degradation via the plasminogen activation cascade. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:237–244. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baum O, et al. Increased invasive potential and up-regulation of MMP-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells expressing the beta3 integrin subunit. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu X, Niu J, Dorahy DJ, Scott R, Agrez MV. Integrin alpha(v)beta6-associated ERK2 mediates MMP-9 secretion in colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:348–351. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kesanakurti D, Chetty C, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Role of MMP-2 in the regulation of IL-6/Stat3 survival signaling via interaction with α5β1 integrin in glioma. Oncogene. 2013;32:327–340. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yue J, Zhang K, Chen J. Role of integrins in regulating proteases to mediate extracellular matrix remodeling. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s12307-012-0101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roman J, Ritzenthaler JD, Roser-Page S, Sun X, Han S. alpha5beta1-integrin expression is essential for tumor progression in experimental lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:684–691. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0375OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuomi S, et al. PKCepsilon regulation of an alpha5 integrin-ZO-1 complex controls lamellae formation in migrating cancer cells. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra32. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.González-Tarragó V, et al. Binding of ZO-1 to α5β1 integrins regulates the mechanical properties of α5β1-fibronectin links. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:1847–1852. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-01-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrow-McGee R, et al. Beta 1-integrin-c-Met cooperation reveals an inside-in survival signalling on autophagy-related endomembranes. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11942. 11942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alanko J, et al. Integrin endosomal signalling suppresses anoikis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1412–1421. doi: 10.1038/ncb3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo W, et al. Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mai A, et al. Distinct c-Met activation mechanisms induce cell rounding or invasion through pathways involving integrins, RhoA and HIP1. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1938–1952. doi: 10.1242/jcs.140657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novitskaya V, et al. Integrin α3β1-CD151 complex regulates dimerization of ErbB2 via RhoA. Oncogene. 2014;33:2779–2789. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. A signaling adapter function for alpha6beta4 integrin in the control of HGF-dependent invasive growth. Cell. 2001;107:643–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desgrosellier JS, et al. Integrin αvβ3 drives slug activation and stemness in the pregnant and neoplastic mammary gland. Dev Cell. 2014;30:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desgrosellier JS, et al. An integrin alpha(v)beta(3)-c-Src oncogenic unit promotes anchorage-independence and tumor progression. Nat Med. 2009;15:1163–1169. doi: 10.1038/nm.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Q, et al. Proapoptotic PUMA targets stem-like breast cancer cells to suppress metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:531–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI93707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]