Abstract

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is upregulated in several human cancers which contributes to tumorigenesis. However, whether UCP2 expression is amplified in cholangiocarcinoma and whether UCP2 promotes cholangiocarcinoma progression are not known. Our results found that in human cholangiocarcinoma tissues, UCP2 was highly expressed in tumors and its levels were negatively associated with prognosis. Importantly, lymph node invasion of cholangiocarcinoma was associated with higher UCP2 expression. In cholangiocarcinoma cells, cell proliferation and migration were suppressed when UCP2 expression was inhibited via gene knockdown. In UCP2 knockdown cells, glycolysis was inhibited, the mesenchymal markers were downregulated whereas AMPK was activated. The increased mitochondrial ROS and AMP/ATP ratio might be responsible for this activation. When the UCP2 inhibitor genipin was applied, tumor cell migration and 3D growth were suppressed via enhancing the mesenchymal-epithelial transition of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Furthermore, cholangiocarcinoma cells became sensitive to cisplatin and gemcitabine treatments when genipin was applied. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the amplified expression of UCP2 contributes to the progression of cholangiocarcinoma through a glycolysis-mediated mechanism.

Keywords: UCP2, Cholangiocarcinoma, EMT, Glycolysis, Mitochondrial ROS

1. Introduction

Cholangiocytes make up the epithelium of the biliary tree, including liver parenchyma and the extrahepatic bile duct. The malignant transformation of cholangiocytes can cause cholangiocarcinomas, the second most common primary malignancy in the hepatobiliary system [1–3]. According to the site of tumor origin, this fatal disease can be divided into intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC) [2]. Difficulties in early diagnose and resistance to therapy, such as chemotherapy, are responsible for the dismal prognosis. Understanding the exact molecular mechanisms of cholangiocarcinoma progression may help improve the prognosis of this disease.

Uncoupling proteins (UCPs), a family of a mitochondrial transmembrane protein, widely exist in vertebrate cells. The primary function of UCPs is mediating the “proton leak” reactions to decrease the electrochemical potential (Δψm), which is used for ATP synthesis [4]. As a ubiquitously expressed UCP, UCP2 is highly expressed in a number of human cancers including pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and skin cancer [5–7]. It has been suggested that UCP2 helps cancer cells tolerate the states of high-load metabolism [8–10].

Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) is a critical process for cancer cells to gain an enhanced ability for migration, invasion, metastasize, and resistance to therapies [11, 12]. Cells undergoing EMT progressively lose the expression of epithelial adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin, while express mesenchymal associated genes, such as vimentin and snail [11]. Studies have demonstrated that EMT can be regulated by cancer metabolism [10, 13, 14]. Certainly, EMT is also a pivotal change during the development and progression of cholangiocarcinoma [15, 16].

In this study, we detected the expression levels of UCP2 in human cholangiocarcinoma tissues and analyzed any association between UCP2 expression and disease progression. We further generated UCP2 stable knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells to study how UCP2 contributes to cholangiocarcinoma progression. Finally, we utilized the UCP2 inhibitor genipin to treat cholangiocarcinoma cells as a translational approach.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Clinical tissue samples

Tissue samples were obtained from 74 patients at the Shaoxing People’s Hospital from January 2013 to February 2018. Informed consent was obtained from patients and the tissue acquisition protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shaoxing People’s Hospital. There were 59 samples of tumor tissues and 15 samples from normal bile ducts. Among the biliary tract cancer patients, 28 patients underwent chemotherapy while 31 patients did not. Normal specimens were obtained from patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy because of pancreatic or duodenal diseases and whose bile ducts were disease-free. The clinical characteristics of the patients were collected; including tumor location, histological type, differentiation grade, lymph node invasion, TNM staging. Fresh tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and used for RNA and protein extraction.

2.2. Cell culture and drug treatment

The intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell line HuCCT1 and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell line TFK-1 were purchased from the RIKEN BioResource Center (Ibaraki, Japan). HEK-293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (VWR Corporate, Radnor, PA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA, USA), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. HEK-293 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. All cell lines were in their low passage numbers.

The UCP2 inhibitor genipin [17], cisplatin, and gemcitabine were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). All chemicals were dissolved as stock solutions with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The stock solutions were further diluted with medium to reach different working concentrations before use. All treatment groups, including the vehicle group, were administered with the same amount of DMSO.

2.3. Establishment of UCP2 stable knockdown (KD) clones

HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells were infected with pooled UCP2 siRNA/shRNA/RNAi lentivirus (Applied Biological Materials, Vancouver, Canada). The target sequences include 5’-CGGTTACAGATCCAAGGAGAA-3’, 5’-GGCCTGTATGATTCTGTCA-3’, 5’-GCACCGTCAATGCCTACAA-3’ and 5’-CGTGGTCAAGACGAGATACATGAACTCTG-3’. Seventy-two hours post-infection, the cells underwent puromycin (1 μg/ml) selection for 2 weeks. The resistant colonies were picked and amplified, and Western blot analysis was performed to select the UCP2 KD clones. The clones infected with scrambled siRNA lentivirus were similarly selected.

2.4. RNA extraction and the polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix using the ABI 7500 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The designed PCR primers were as follows: UCP2 forward primer, 5’-TGGTCGGAGATACCAAAGCACC −3’; UCP2 reverse primer, 5’-GCTCAGCACAGTTGACAATGGC −3’; β-actin forward primer, 5’AGAAGGAGATCACTGCCCTGGCACC −3’; β-actin reverse primer, 5’-CCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCTGCTG −3’. β-actin was used as the endogenous control. Experiments were repeated three times. Relative expression levels were determined using the 2 −ΔΔCt methods [18].

2.5. Western blot analysis

Primary antibodies against β-actin, AMPK, E-cadherin, Vimentin, snail, YB-1 (Y-box binding protein-1), Bax (BCL2-associated X protein), and Bcl2 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). Primary antibodies against UCP2, p-473Ser-AKT, AKT, p-172Thr-AMPK, FoxO3a, and cleaved caspase 3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA). 20 μg total protein was separated on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred onto a poly-vinylidene fluoride membranes, blocked, incubated with a primary antibody following by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence solution (Genesee Scientific, El Cajon, CA, USA). Experiments were repeated three times. β-actin was employed as the loading control. The pixel densities of proteins were quantified by ImageJ.

2.6. Cell proliferation assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed using the IncuCyte live-cell system (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Two thousand viable cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Corning 353072). Cells were imaged every 4 h and proliferation rates based on confluency were determined using the IncuCyte software. Eight repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

2.7. Wound healing assays

Twenty thousand HuCCT1 and Forty thousand TFK-1 were seeded and cultured overnight in 96-well plates (Essen BioScience, 4379). Scratches were introduced by the Woundmaker (Essen BioScience). Wells were washed twice with the serum-free medium; fresh culture medium was then added. Imaging was dynamically captured. Because of the differences in migration, HuCCT1 cells were analyzed after a 12-hour incubation and TFK-1 cells were analyzed after 24-hour incubation. Six repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

2.8. Transwell invasion assays

After starving overnight with serum-free medium, ten thousand cells in 0.1 ml serum-free medium were placed into the upper chamber of the insert (Corning, NY, USA) coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and 0.5 ml growth medium was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h, cells migrated to the other side of the insert were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 0.05% crystal violet. These experiments were repeated three times.

2.9. Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

Ten thousand cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. Cells were incubated with growth medium containing 2 μg/ml JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine iodide, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min. The medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS. Fluorescence intensity was measured immediately by fluorescence spectrometry (For JC-1 green, Ex=485 nm, Em=525 nm; for JC-1 red, Ex=535 nm, Em=590 nm). Six repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

2.10. Detection of ATP and AMP by high-performance liquid chromatography

Standard ATP and AMP were purchased from Research Products International (Mount Prospect, IL, USA) and Beantown Chemical (Hudson, NH, USA), respectively. Intracellular levels of ATP and AMP in cholangiocarcinoma cells were measured as previously reported with slight modifications [19]. Cells in exponential phase were harvested from 60-mm culture dishes at the same confluency. Cells were lysed by sonication and proteins were eliminated by filtering through 10k cut-off columns. 10 μl of filtered sample was injected into Shimadzu Prominence 20A equipped with SPD-20AV and an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6×250 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of buffer A (Water, 0.1% TFA) and buffer B (acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA). The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min. ATP and AMP were detected at 254 nm, and the separation was performed using continuous gradient elution. The gradient program was as followings: 2 min 99% buffer A; 7 min 80% buffer A; 7.5 min 10% buffer A; 8.5 min 10 % buffer A and 9.0 min 99% buffer A. Finally, the program took a further 1 min to return to the initial conditions and stabilize. Typical retention times for ATP and AMP were 2.78 min and 5.43 min, respectively. The concentrations of ATP and AMP were determined using the external standard method. Six samples from each cell were analyzed and the ratios of AMP/ATP were calculated.

2.11. 3D spheroid growth

A 96-well round bottom plate (ultra-low attachment, Corning, NY, USA) was used for seeding cells. Five thousand viable cells were seeded in 90 μL medium containing 5% Matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). After centrifuging at 700 rpm for 5 min, the plate was incubated overnight to form spheroids. The next day, 10 μL treatments (genipin and/or gemcitabine) were added into the culture. The spheroids were imaged every 48 h and the volume was calculated with the following formula: volume = 4/3π*b2*c (b=longest semidiameter, c= shortest semidiameter). Six repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

2.12. Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescent staining of cells was performed as previously described with a minor modification [20]. Briefly, ten thousand HuCCT1 or TFK-1 cells were seeded into 8-well Chamber Slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and cultured overnight. Cells were washed with PBS then fixed with cold 70% ethanol. After washing with PBS and blocking, a primary antibody was added (1:50 dilution) and incubated at 4° C overnight, followed by incubation with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma, 1:128 dilution) for 1 hour. Fluorescence was immediately detected using a New-Zeiss AxioObserver microscope (Oberkochen, Germany). Experiments were repeated three times.

2.13. Drug sensitivity assays

Cisplatin and gemcitabine were used as chemo drugs to evaluate the effect of genipin on chemotherapy sensitivity. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (four thousand cells/well), and cultured overnight. Cells were treated with various concentrations of drugs plus 50 μM genipin. After incubated for 48 h, viable cells were determined using the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) assay. One-tenth volume of MTT diluted in serum-free medium was added to each well, and the plates were further incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance at 595 nm was measured using a spectrometer (Bio-Rad, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Eight repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

2.14. Lactate assay

Intracellular levels of lactate were measured using the Lactate Assay Kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lactate levels were normalized to the amount of proteins extracted from the cells. Experiments were repeated three times.

2.15. Detection of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS)

MitoSOX™ Red probe (Invitrogen) was used to detect mitochondrial ROS. Cells were incubated in Hank’s buffer containing 5 μM MitoSOX and 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 30 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After washed with PBS, cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope. Six repeated wells from each cell were analyzed.

The flow cytometry assay was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, 0.5 × 106 cells were suspended in 0.5 ml RPMI-1640 medium containing 2.5 μM MitoSOX in a 37°C water bath, protected from light, for 40 min. After washed with PBS, the red fluorescence was detected by FACScan using the LSRII SORP (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin, NJ, USA). Experiments were repeated three times.

2.16. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay

SOD activity was measured using the Superoxide Dismutase Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical). Whole Cell Lysate was prepared in PBS (containing proteinase inhibitors) by sonication. The measurement was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final SOD activity was normalized by the protein concentration. Experiments were repeated three times.

2.17. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 13.0. Our data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the differences between groups were analyzed using One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey–Kramer adjustment. The relationship between UCP2 expression and clinicopathological features of cholangiocarcinoma were analyzed with χ2 test. p< 0.05 was defined as significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. UCP2 expression was upregulated in human cholangiocarcinoma tissues

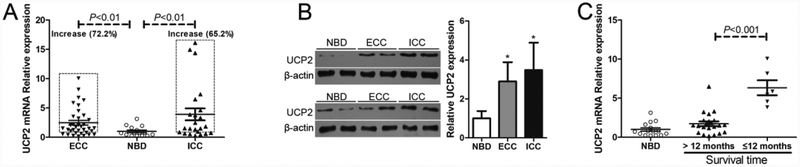

To determine the clinical relevance of UCP2 in human cholangiocarcinoma, quantitative real-time PCR was performed to determine the levels of UCP2 mRNA in 59 human cholangiocarcinoma tissue samples. Compared to that in normal biliary duct (NBD) specimens, the UCP2 mRNA levels were increased in 26 of 36 ECC tumors (72.2%) and 15 of 23 ICC tumors (65.2%), both differences were significant (Fig. 1A). The results from Western blot analysis further confirmed that UCP2 protein levels were upregulated in both ECC and ICC tumor tissues (Fig. 1B). Next, the UCP2 mRNA levels in the tumor samples from the patients who underwent chemotherapy and had different prognosis were also detected. As shown in Fig. 1C, UCP2 mRNA levels were higher in the tumor samples from the patients who had a worse prognosis (survival time ≤12 months), compared to those from the patients who had a better prognosis (survival time >12 months).

Figure 1.

The expression levels of UCP2 are increased in human cholangiocarcinoma. (A) Detection of the mRNA levels of UCP2 in cholangiocarcinoma tissue samples. (B) Detection of the protein levels of UCP2 in cholangiocarcinoma tissue samples. Left panel: representative Western blot results were shown. Right panel: summary of the results (n=8, each group). (C) Comparison of the mRNA levels of UCP2 in tumor samples with patients’ prognosis outcomes (n=22, >12 months; n=6, ≤ 12 months). ECC: extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; ICC: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; NBD: normal bile duct. *P < 0.05, compared with NBD.

Patients enrolled in this study were classified according to the expression level of UCP2 mRNA, and clinical characteristics were compared. Most clinical characteristics including gender, tumor location, age, differentiation grade, TNM staging or serum markers, were not found to be associated with the expression levels of UCP2 (Table 1). However, increased lymph node invasion was positively associated with higher UCP2 expression (Table 1). This result suggests a correlation between the expression of UCP2 and the metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma.

Table 1.

The relationship between UCP2 expression and clinicopathological features of cholangiocarcinoma.

| Variables | N | UCP2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | P | ||

| Gender | 41 | 18 | ||

| Male | 30 | 21 | 9 | 0.931 |

| Female | 29 | 20 | 9 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≥60 | 39 | 25 | 14 | 0.209 |

| <60 | 20 | 16 | 4 | |

| Tumor location | ||||

| ICC | 23 | 15 | 8 | 0.569 |

| ECC | 36 | 26 | 10 | |

| Lymph node invasion | ||||

| Present | 18 | 18 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Absent | 41 | 23 | 18 | |

| TNM staging | ||||

| I–II | 48 | 34 | 14 | 0.640 |

| III–IV | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

| Serum CEA level (ng/ml) | ||||

| >5 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 0.466 |

| ≤5 | 40 | 29 | 11 | |

| Serum CA19–9 level (U/ml) | ||||

| >37 | 41 | 29 | 12 | 0.755 |

| ≤37 | 18 | 12 | 6 | |

| Serum CA50 level (IU/ml) | ||||

| >25 | 39 | 28 | 11 | 0.592 |

| ≤25 | 20 | 13 | 7 | |

| Serum CA125 level (U/ml) | ||||

| >35 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0.474 |

| ≤35 | 49 | 35 | 14 | |

| Differentiation | ||||

| G1 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 0.286 |

| G2 | 25 | 19 | 6 | |

| G3 | 19 | 14 | 5 | |

The expression level of UCP2 in a tumor tissue was higher than the average UCP2 expression level in normal bile ducts, was defined as ‘High’; the opposite was defined as ‘low’. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant and showed in bold. ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; ECC, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis classification according to the AJCC/UICC 8th edition; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA, carbohydrate antigen; G1, well differentiated; G2, moderately−differentiated; G3, poorly−differentiated.

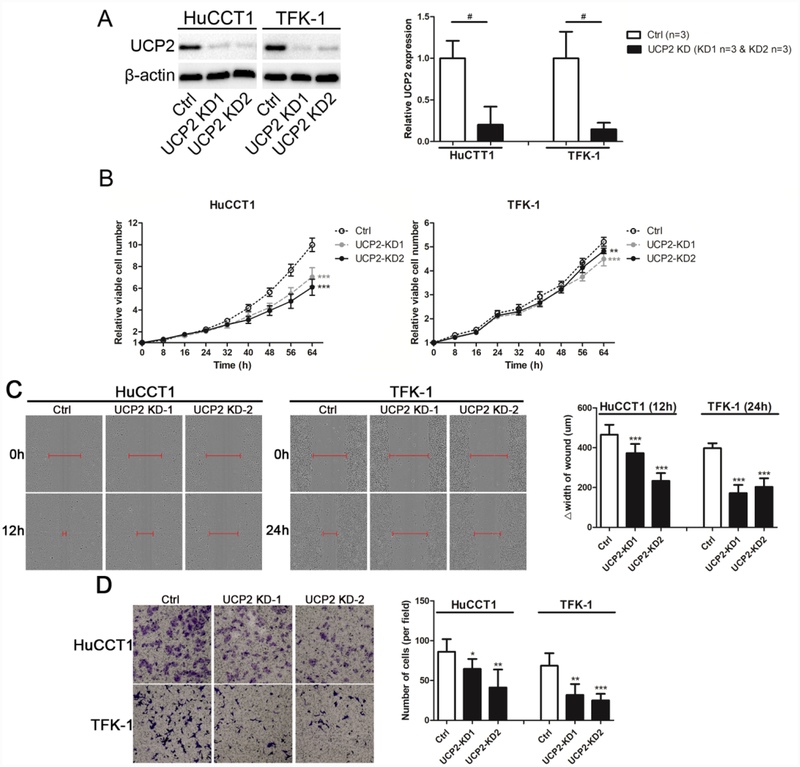

3.2. Cell proliferation and migration were suppressed in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells

To represent the different subtype of cholangiocarcinoma, An ICC cell line HuCCT1 and an ECC cell line TFK-1 were used and infected with UCP2 knockdown lentivirus. After selection, stable knockdown clones were established (Fig. 2A). Cell proliferation assays were performed to determine whether UCP2 knockdown affected cholangiocarcinoma cell growth. As shown in Fig. 2B, cell growth rates were decreased in the UCP2 knockdown cells compared to that in the control cells. Given that higher UCP2 expression was associated with increased lymph node invasion in clinical samples (Table 1), wound healing and transwell assays were performed to study whether UCP2 regulates cell migration and invasion. As shown in Fig. 2C & 2D, cell migration and invasion were suppressed by UCP2 knockdown. These results indicate that aberrant expression of UCP2 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells.

Figure 2.

Cell proliferation and migration are suppressed in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A) Western blots show the protein level of UCP2 is significantly reduced in UCP2 knockdown clones. (B) Cell proliferation assays of UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. (C) Wound healing (magnification: 10×) and (D) transwell invasion assays (magnification: 10×) of UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. △width of wound = width of wound at start (0 h)-width of wound at end (12 h or 24h). UCP2-KD1: UCP2 knockdown clone 1; UCP2-KD2: UCP2 knockdown clone 2. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus the Ctrl clone of the same cell line. #P < 0.05, significant differences between the two groups.

3.3. The mesenchymal phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells was suppressed in UCP2 knockdown cells

When epithelial cancer cells lose their cell adhesion molecules and concomitantly acquire the features of mesenchymal cancer cells, known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), they will gain the stronger ability for migration and invasion [10, 22]. As shown in Fig. 3A, the epithelial adhesion molecule E-cadherin was upregulated whereas the mesenchymal-associated proteins including vimentin, snail, and Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1), were downregulated in the UCP2-knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. These characteristic changes indicate that inhibition of UCP2 may reverse the mesenchymal phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma.

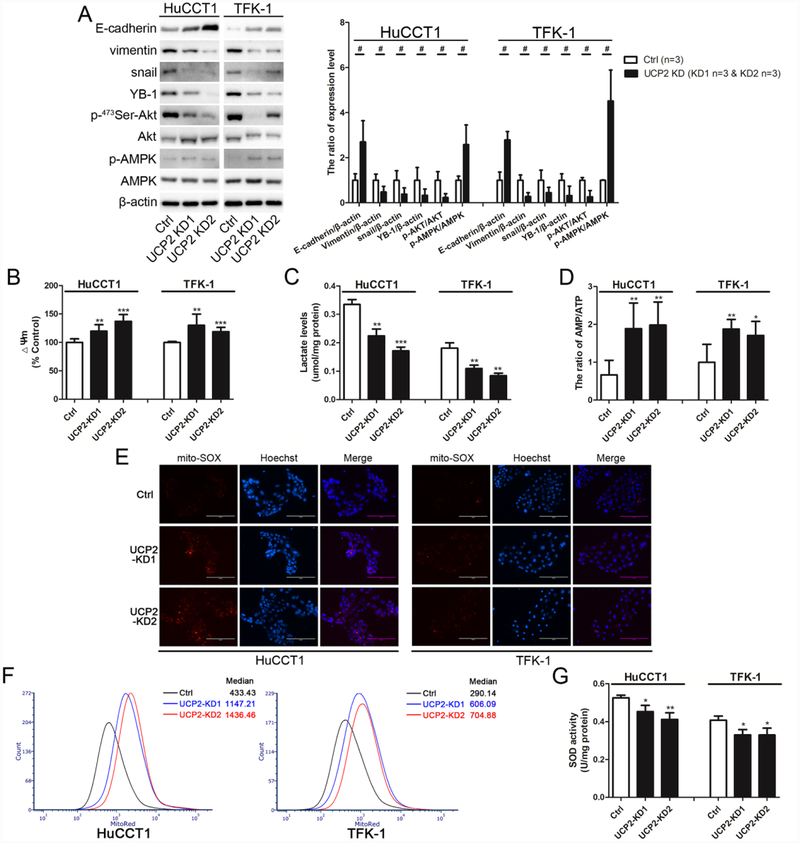

Figure 3.

The AMP/ATP ratio and mtROS levels are increased and glycolysis is inhibited in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A) Detection and quantification of EMT-related markers and the AMPK/Akt signaling molecules in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. (B) Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in UCP2 knockdown cells. (C) Detection of intracellular lactate levels in UCP2 knockdown cells. (D) Detection of the AMP/ATP ratio in UCP2 knockdown cells by HPLC. Fluorescent images (E) and flow sorting (F) of mitoSOX stained cells. (G) Detection of SOD activity in UCP2 knockdown cells. UCP2-KD1: UCP2 knockdown clone 1; UCP2-KD2: UCP2 knockdown clone 2. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus the Ctrl clone of the same cell line. #P < 0.05, significant differences between the two groups.

3.4. The AMP/ATP ratio and mtROS levels were increased in UCP2 knockdown cells

Given the primary function of UCPs as anion carriers across the mitochondrial inner membrane and mediating the mitochondrial uncoupling effect [4], mitochondrial membrane potential (Δѱm) was measured. As shown in Fig. 3B, the levels of mitochondrial membrane potential were increased in the UCP2 knockdown cells compared to that in the control cells. Next, lactate, the metabolic product of glycolysis, was measured to evaluate glycolysis in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. As shown in Fig. 3C, the levels of intracellular lactate were decreased in the UCP2 knockdown cells, suggesting that glycolysis is alleviated when UCP2 expression is inhibited.

Energy production can be influenced by the changes in metabolic states [10]. AMP/ATP levels were measured by HPLC to evaluate the status of energy production in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. As shown in Fig. 3D, the ratios of AMP/ATP were increased in the UCP2 knockdown cells compared to that in the control cells.

Regulating oxidative stress in mitochondria is another important function of UCP2 [23, 24], and enhanced glycolysis could enable cancer cells to avoid excess ROS generation from mitochondrial respiration [25]. Therefore, mtROS levels were detected in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells. As shown in Fig. 3E & 3F, mtROS levels were increased in the UCP2 knockdown cells. Next, SOD activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 3G, the levels of SOD activity were decreased in the UCP2 knockdown cells compared to that in the control cells (Fig. 3G).

3.5. AMPK was activated whereas Akt was inactivated during reverse EMT in UCP2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells

The AMPK signaling, a pivotal pathway in cellular metabolism, is not only activated by an increased AMP/ATP ratio [26, 27], but also regulated by mtROS [14, 28]. Not surprising, AMPK activation was detected in the UCP2 knockdown clones of cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 3A). Previous studies have found that activated AMPK can reverse the mesenchymal phenotype of cancer cells via inhibiting the Akt signaling [29, 30]. Indeed, attenuated Akt activation was detected in the UCP2 knockdown cells (Fig. 3A).

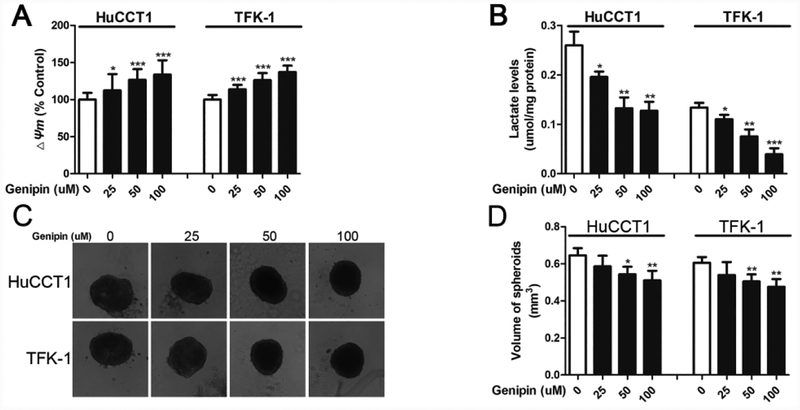

3.6. 3D spheroid growth and cell migration were suppressed and the epithelial phenotype was induced upon genipin treatment

Genipin, an inhibitor of UCP2’s proton-leak activity, has been tested for its anti-tumor activity in several human cancer cells [8, 17]. Here we applied genipin to cholangiocarcinoma cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, the levels of mitochondrial membrane potential were increased after genipin treatment, confirming that genipin inhibits UCP2’s proton-leak activity. Similar to the UCP2 knockdown approach, genipin treatment also decreased the levels of lactate in cholangiocarcinoma cells (Fig. 4B). Next, 3D spheroid growth of HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells was used to mimic tumor growth in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4C & 4D, genipin treatments (50 and 100 μM) reduced the sizes of the spheroids formed by HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells.

Figure 4.

Genipin treatments suppress spheroid growth of cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A) Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in cholangiocarcinoma cells after genipin treatments. (B) Detection of intracellular lactate levels in cholangiocarcinoma cells after genipin treatments. (C & D) Detection and quantification of spherical growth after genipin treatments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus the 0 μM genipin group.

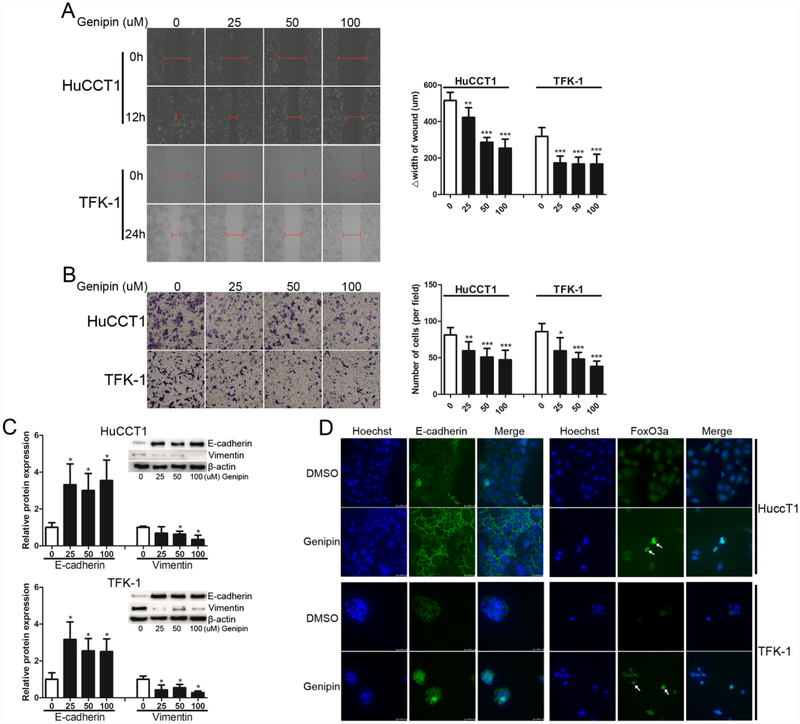

Similar to the effect of UCP2 knockdown, genipin treatment suppressed cell migration and invasion of HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells (Fig. 5A and 5B). Given that UCP2 knockdown reverses the mesenchymal phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells, Markers for EMT were detected in HuCCT1 and TFK-1 cells after genipin treatment. As shown in Fig. 5C, the expression of E-cadherin was upregulated whereas that of vimentin was downregulated. Nuclear translocation of FOXO3 has been observed as an important event to reverse the mesenchymal phenotype of cancer cells by abundant studies [29, 31, 32]. Hence, we detected the subcellular location of FoxO3a in cholangiocarcinoma cells with or without genipin treatment by immunofluorescence staining. Interestingly, more nuclear FoxO3a (the activated form) was observed in genipin-treated cells, along with more E-cadherin expression in the cell membrane (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Genipin treatments suppress cell migration and induce the epithelial phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A) Wound healing (magnification: 10×) and (B) transwell invasion assays (magnification: 10×) after genipin treatments. (C) Detection and quantification of EMT-related markers after genipin treatments. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin and FoxO3a in cholangiocarcinoma cells after treated with 50 μM genipin for one week (white arrow: FoxO3a nuclear localization; magnification: 40×). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus the 0 μM genipin group.

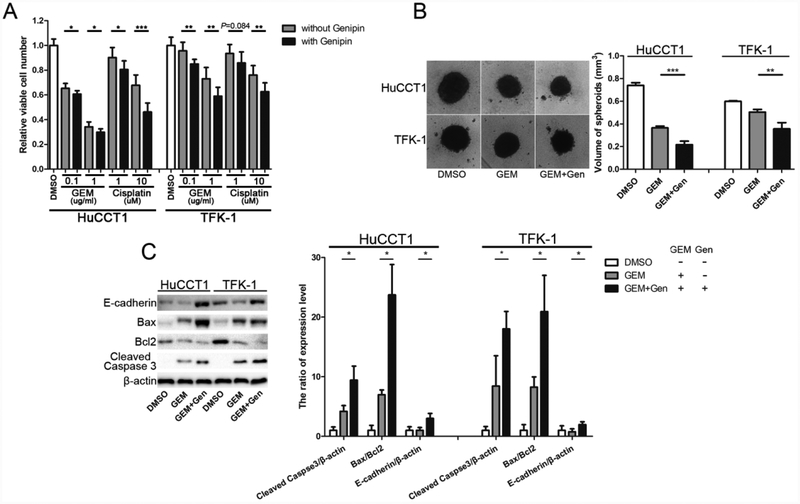

3.7. Cholangiocarcinoma cells became more sensitive to drugs upon genipin treatment

Besides facilitating metastasis, EMT is also regarded as an important inducement for treatment resistance, including chemotherapy resistance [11, 33–35]. We studied whether genipin can make cholangiocarcinoma cells more sensitive to chemo drugs. As shown in Fig. 6A, the combination treatments induced more cell death of cholangiocarcinoma cells than gemcitabine or cisplatin alone. The combination treatments further suppressed 3D spheroid growth of cholangiocarcinoma cells (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Genipin makes cholangiocarcinoma cells more sensitive to drug treatments. (A) Comparison of chemosensitivity with or without genipin (50 μM). (B) Spheroid growth of cholangiocarcinoma cells after genipin (50 μM) plus gemcitabine (1 μg/ml) treatment for one week. (C) Detection and quantification of the apoptotic and EMT markers. The spheroids from the 3D culture were collected and used for the experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, significant difference between the two groups.

Cleaved-caspase 3 and the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 are often used to evaluate apoptosis [36, 37]. The spherical tumors in 3D culture were collected to detect these markers for apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 6C, the ratios of Bax/Bcl2 were increased at the protein levels in the cells treated with genipin plus gemcitabine, compared to gemcitabine alone. Similarly, the levels of cleaved-caspase 3 were also increased in the combined treatment groups (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, the combination treatment also induced the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Fig. 6C).

4. DISCUSSION

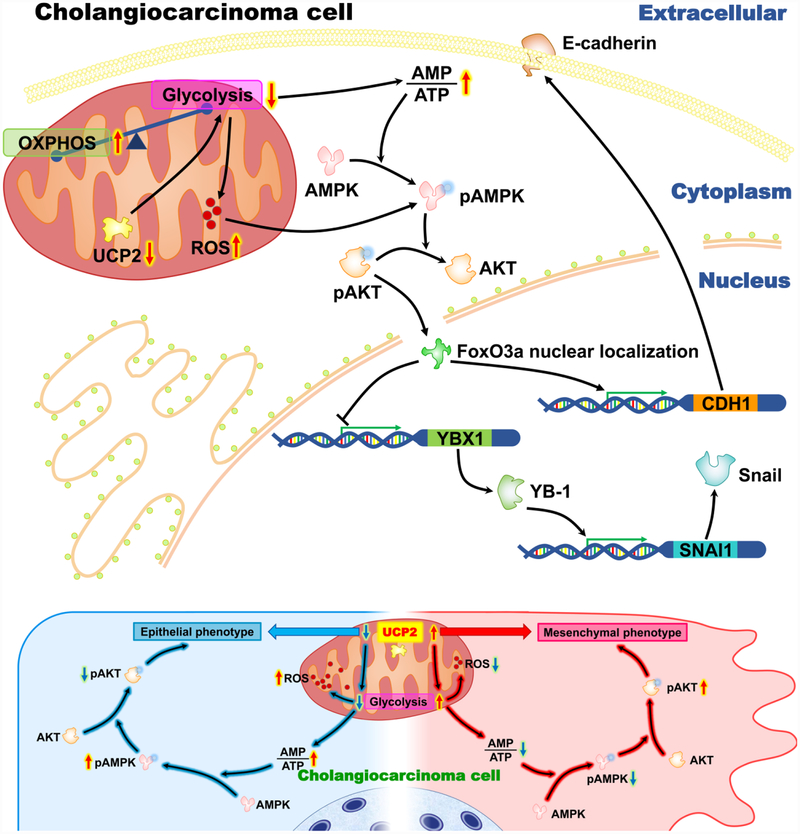

Metabolic plasticity and reprogramming is a pivotal factor in the process of oncogenesis and tumor development even influences prognosis [10]. As a dismal carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma requires more research efforts to improve prognosis. As one of the cancer hallmarks, cancer metabolism is an emerging area for developing new therapies. As an important regulator of energy metabolism, UCP2 is highly expressed in various cancers, including pancreatic, prostate, breast, lung, and skin cancer [5–7]. In this study, we first report that UCP2 is upregulated in human cholangiocarcinoma and its mRNA levels are positively associated with lymph invasion and negatively associated with treatment outcomes. Using cholangiocarcinoma cells, our studies demonstrate that highly expressed UCP2 also contributes to EMT, a process known to promote tumor metastasis and invasion [22, 38, 39]. Many cancers rely on aerobic glycolysis, also known as “the Warburg effect”, in support of the high-load metabolism and rapid growing [10, 40]. As a transporter in the mitochondrial inner membrane, UCP2 functions as an important mediator for glycolysis in a number of cancers [8, 9]. Based on our results, how UCP2 promotes cholangiocarcinoma progression via regulating cancer metabolism has been summarized in Fig. 7. When UCP2 is inhibited in cholangiocarcinoma cells, glycolysis is alleviated, the ratio of AMP/ATP is increased, AMPK becomes activated whereas Akt is inactivated. These results suggest that aerobic glycolysis is a major energy provider in cholangiocarcinoma cells, and UPC2 is an important regulator of glycolysis.

Figure 7.

A schematic diagram showing the potential mechanisms of how UCP2 inhibition suppresses cholangiocarcinoma cell growth.

Higher AMP levels can activate AMPK, a critical energy sensor. Studies have shown that AMPK activities are lower when cells undergo glycolysis but become higher during oxidative phosphorylation [10, 14]. Inactivation of AMPK drives a metabolic switch to glycolysis [41]. When AMPK is activated, Akt is often inactivated in human cancers [42, 43]. The phosphorylation of Akt is a potent inducer for EMT, which activates a series of downstream targets [44, 45]. How UCP2 mediates these events? Our results demonstrate increased levels of mtROS and decreased levels of SOD activities in UPC2 knockdown cholangiocarcinoma cells, suggesting a link between UCP2, SOD, and mtROS. Although ROS are regarded as initiators in cancer, high ROS levels cause cell death and migration inhibition in cancer cells [25, 46–48]. During metabolic reprogramming, the AMPK signaling can also be activated by mtROS [10, 14, 28], which provides an additional route for UCP2 to regulates the AMPK/Akt pathway.

What are the potential downstream events of the AMPK/Akt pathway in cholangiocarcinoma cells? The transcription factor FoxO3a is known to negatively regulate tumorigenesis and chemoresistance in cholangiocarcinoma [49]. In various cancers, the activation of FoxO3a is inhibited by activated Akt [45, 50, 51]. Given that inactivated FoxO3a is cytoplasmically sequestrated in cancer cells [52], the subcellular location of FoxO3a in genipin-treated cholangiocarcinoma cells was detected. More nuclear FoxO3a (the activated form) was observed in genipin-treated cells (Fig. 5D). FoxO3a suppresses tumor progression through regulating YB-1, snail, and E-cadherin [53, 54]. In our study, YB-1 and Snail were downregulated whereas E-cadherin was upregulated in the UCP2 knockdown cells (Fig. 3A). Taken together, suppression of UCP2 inhibits glycolysis, increases mtROS, activates AMPK and inactivates Akt, which might be responsible for the reverse EMT phenotype in cholangiocarcinoma cells.

As a translational approach, we applied the UCP2 inhibitor genipin in our studies. Genipin treatment induces the epithelial phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells, similar to the UCP2 gene knockdown approach. Although genipin shows no overt toxicity in animal studies, its potential toxicity should not be ignored. We tested the toxicity of genipin using HEK-293 cells. Based on our preliminary studies, genipin was toxic to the cells at the highest concentration (200 μM). Therefore, three concentrations including 25 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM of genipin were used in our experiments. Both 50 μM and 100 μM genipin inhibited the growth of HuCCT1 cells.

Inhibition of UCP2 has been tested to overcome chemotherapy resistance in several cancer cells [9, 55]. We treated cholangiocarcinoma cells with genipin plus gemcitabine. We used 50 μM genipin, since this concentration did not inhibit cell growth after a 48-hour treatment (data not shown). Results from MTT and 3D spheroid assays demonstrate that genipin treatment makes cholangiocarcinoma cells more sensitive to gemcitabine. To determine whether genipin by itself induces apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells, the protein levels of Bax and Bcl2 were examined. The results found no significant change in the Bax/Bcl2 ratio after genipin treatment (data not shown). Whereas this concentration of genipin enhanced apoptosis in combination with gemcitabine (Fig. 6C). These results may provide an explanation for the association between higher UCP2 expression and worse prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma patients after chemotherapy.

In summary, our results demonstrate that UCP2 is upregulated in human cholangiocarcinoma, which is associated with worse prognosis. Inhibition of UCP2 suppresses glycolysis, cell proliferation, migration, spheroid growth; reverses EMT; and reduces drug resistance in cholangiocarcinoma cells. These changes are possibly regulated by activated AMPK and inactivated Akt, and mtROS may connect UCP2 to the AMPK/Akt signaling.

Acknowledge

The work was sponsored by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) No. 81602044; Zheng Shu Medical Elite Scholarship Fund; Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China No. LY19H160016 and LY17H030001; and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health P20GM121307.

IncuCyte Zoom was provided by the Feist-Weiller Cancer Center’s Innovative North Louisiana Experimental Therapeutics program (INLET), which is directed by Dr. Glenn Mills at LSUHSC-Shreveport and supported by the LSU Health Shreveport Foundation. We thank Dr. Ana-Maria Dragoi, Associate Director of INLET, Dr. Jennifer Carroll, Director of the In Vivo, In Vitro Efficacy Core and Reneau Youngblood, Research Associate for their assistance in IncuCyte studies.

Flow cytometry experiments were performed by David Custis at the institutional Research Core Facility.

Abbreviations

- UCP2

Uncoupling protein 2

- ICC

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- ECC

extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- NBD

normal biliary duct

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transitions

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- YB-1

Y-box binding protein-1

- Bax

BCL2-associated X protein

- Bcl2

B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2

- FoxO3a

Forkhead box O3A

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- mtROS

mitochondrial ROS

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference

- [1].Rizvi S, Gores GJ, Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma, Gastroenterology 145(6) (2013) 1215–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM, Biliary tract cancers, N Engl J Med 341(18) (1999) 1368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF, The Cholangiopathies, Mayo Clin Proc 90(6) (2015) 791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Robbins D, Zhao Y, New aspects of mitochondrial Uncoupling Proteins (UCPs) and their roles in tumorigenesis, Int J Mol Sci 12(8) (2011) 5285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Su WP, Lo YC, Yan JJ, Liao IC, Tsai PJ, Wang HC, Yeh HH, Lin CC, Chen HH, Lai WW, Su WC, Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 regulates the effects of paclitaxel on Stat3 activation and cellular survival in lung cancer cells, Carcinogenesis 33(11) (2012) 2065–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pons DG, Nadal-Serrano M, Torrens-Mas M, Valle A, Oliver J, Roca P, UCP2 inhibition sensitizes breast cancer cells to therapeutic agents by increasing oxidative stress, Free Radic Biol Med 86 (2015) 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li W, Nichols K, Nathan CA, Zhao Y, Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 is up-regulated in human head and neck, skin, pancreatic, and prostate tumors, Cancer Biomark 13(5) (2013) 377–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brandi J, Cecconi D, Cordani M, Torrens-Mas M, Pacchiana R, Dalla Pozza E, Butera G, Manfredi M, Marengo E, Oliver J, Roca P, Dando I, Donadelli M, The antioxidant uncoupling protein 2 stimulates hnRNPA2/B1, GLUT1 and PKM2 expression and sensitizes pancreas cancer cells to glycolysis inhibition, Free Radic Biol Med 101 (2016) 305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Derdak Z, Mark NM, Beldi G, Robson SC, Wands JR, Baffy G, The mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 promotes chemoresistance in cancer cells, Cancer Res 68(8) (2008) 2813–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jia D, Park JH, Jung KH, Levine H, Kaipparettu BA, Elucidating the Metabolic Plasticity of Cancer: Mitochondrial Reprogramming and Hybrid Metabolic States, Cells 7(3) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gaianigo N, Melisi D, Carbone C, EMT and Treatment Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer, Cancers (Basel) 9(9) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].van Roy F, Beyond E-cadherin: roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer, Nat Rev Cancer 14(2) (2014) 121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Halldorsson S, Rohatgi N, Magnusdottir M, Choudhary KS, Gudjonsson T, Knutsen E, Barkovskaya A, Hilmarsdottir B, Perander M, Maelandsmo GM, Gudmundsson S, Rolfsson O, Metabolic re-wiring of isogenic breast epithelial cell lines following epithelial to mesenchymal transition, Cancer Lett 396 (2017) 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yu L, Lu M, Jia D, Ma J, Ben-Jacob E, Levine H, Kaipparettu BA, Onuchic JN, Modeling the Genetic Regulation of Cancer Metabolism: Interplay between Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation, Cancer Res 77(7) (2017) 1564–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Carpino G, Cardinale V, Folseraas T, Overi D, Grzyb K, Costantini D, Berloco PB, Di Matteo S, Karlsen TH, Alvaro D, Gaudio E, Neoplastic transformation of peribiliary stem cell niche in cholangiocarcinoma arisen in primary sclerosing cholangitis, Hepatology (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Qian Y, Yao W, Yang T, Yang Y, Liu Y, Shen Q, Zhang J, Qi W, Wang J, aPKC-iota/PSp1/Snail signaling induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and immunosuppression in cholangiocarcinoma, Hepatology 66(4) (2017) 1165–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shanmugam MK, Shen H, Tang FR, Arfuso F, Rajesh M, Wang L, Kumar AP, Bian J, Goh BC, Bishayee A, Sethi G, Potential role of genipin in cancer therapy, Pharmacol Res 133 (2018) 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD, Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method, Methods 25(4) (2001) 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sun A, Li C, Chen R, Huang Y, Chen Q, Cui X, Liu H, Thrasher JB, Li B, GSK-3beta controls autophagy by modulating LKB1-AMPK pathway in prostate cancer cells, Prostate 76(2) (2016) 172–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhao Y, Chaiswing L, Velez JM, Batinic-Haberle I, Colburn NH, Oberley TD, St Clair DK, p53 translocation to mitochondria precedes its nuclear translocation and targets mitochondrial oxidative defense protein-manganese superoxide dismutase, Cancer Res 65(9) (2005) 3745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kauffman ME, Kauffman MK, Traore K, Zhu H, Trush MA, Jia Z, Li YR, MitoSOX-Based Flow Cytometry for Detecting Mitochondrial ROS, React Oxyg Species (Apex) 2(5) (2016) 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kalluri R, Weinberg RA, The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, J Clin Invest 119(6) (2009) 1420–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dando I, Pacchiana R, Pozza ED, Cataldo I, Bruno S, Conti P, Cordani M, Grimaldi A, Butera G, Caraglia M, Scarpa A, Palmieri M, Donadelli M, UCP2 inhibition induces ROS/Akt/mTOR axis: Role of GAPDH nuclear translocation in genipin/everolimus anticancer synergism, Free Radic Biol Med 113 (2017) 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qiao C, Wei L, Dai Q, Zhou Y, Yin Q, Li Z, Xiao Y, Guo Q, Lu N, UCP2-related mitochondrial pathway participates in oroxylin A-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells, J Cell Physiol 230(5) (2015) 1054–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lu J, Tan M, Cai Q, The Warburg effect in tumor progression: mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism, Cancer Lett 356(2 Pt A) (2015) 156–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Carling D, AMPK signalling in health and disease, Curr Opin Cell Biol 45 (2017) 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, Leclerc J, Foretz M, Andreelli F, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview, Clin Sci (Lond) 122(6) (2012) 253–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rabinovitch RC, Samborska B, Faubert B, Ma EH, Gravel SP, Andrzejewski S, Raissi TC, Pause A, St-Pierre J, Jones RG, AMPK Maintains Cellular Metabolic Homeostasis through Regulation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species, Cell Rep 21(1) (2017) 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chou CC, Lee KH, Lai IL, Wang D, Mo X, Kulp SK, Shapiro CL, Chen CS, AMPK reverses the mesenchymal phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the Akt-MDM2-Foxo3a signaling axis, Cancer Res 74(17) (2014) 4783–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dokla EM, Fang CS, Lai PT, Kulp SK, Serya RA, Ismail NS, Abouzid KA, Chen CS, Development of Potent Adenosine Monophosphate Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) Activators, ChemMedChem 10(11) (2015) 1915–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Belguise K, Guo S, Sonenshein GE, Activation of FOXO3a by the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces estrogen receptor alpha expression reversing invasive phenotype of breast cancer cells, Cancer Res 67(12) (2007) 5763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ni D, Ma X, Li HZ, Gao Y, Li XT, Zhang Y, Ai Q, Zhang P, Song EL, Huang QB, Fan Y, Zhang X, Downregulation of FOXO3a promotes tumor metastasis and is associated with metastasis-free survival of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma, Clin Cancer Res 20(7) (2014) 1779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, Sheng J, Li F, Wong ST, Choi H, El Rayes T, Ryu S, Troeger J, Schwabe RF, Vahdat LT, Altorki NK, Mittal V, Gao D, Epithelial-to mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance, Nature 527(7579) (2015) 472–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Amawi H, Ashby CR, Samuel T, Peraman R, Tiwari AK, Polyphenolic Nutrients in Cancer Chemoprevention and Metastasis: Role of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal (EMT) Pathway, Nutrients 9(8) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brozovic A, The relationship between platinum drug resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Arch Toxicol 91(2) (2017) 605–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vaughan AT, Betti CJ, Villalobos MJ, Surviving apoptosis, Apoptosis 7(2) (2002) 173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zinkel S, Gross A, Yang E, BCL2 family in DNA damage and cell cycle control, Cell Death Differ 13(8) (2006) 1351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA, Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease, Cell 139(5) (2009) 871–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chaffer CL, San Juan BP, Lim E, Weinberg RA, EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis, Cancer Metastasis Rev 35(4) (2016) 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Warburg O, On the origin of cancer cells, Science 123(3191) (1956) 309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Antico Arciuch VG, Russo MA, Kang KS, Di Cristofano A, Inhibition of AMPK and Krebs cycle gene expression drives metabolic remodeling of Pten-deficient preneoplastic thyroid cells, Cancer Res 73(17) (2013) 5459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kim KY, Baek A, Hwang JE, Choi YA, Jeong J, Lee MS, Cho DH, Lim JS, Kim KI, Yang Y, Adiponectin-activated AMPK stimulates dephosphorylation of AKT through protein phosphatase 2A activation, Cancer Res 69(9) (2009) 4018–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jin Q, Feng L, Behrens C, Bekele BN, Wistuba II, Hong WK, Lee HY, Implication of AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt-regulated survivin in lung cancer chemopreventive activities of deguelin, Cancer Res 67(24) (2007) 11630–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Larue L, Bellacosa A, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3’ kinase/AKT pathways, Oncogene 24(50) (2005) 7443–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sunters A, Madureira PA, Pomeranz KM, Aubert M, Brosens JJ, Cook SJ, Burgering BM, Coombes RC, Lam EW, Paclitaxel-induced nuclear translocation of FOXO3a in breast cancer cells is mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt, Cancer Res 66(1) (2006) 212–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Galadari S, Rahman A, Pallichankandy S, Thayyullathil F, Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: To promote or to suppress?, Free Radic Biol Med 104 (2017) 144–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Al-Khayal K, Alafeefy A, Vaali-Mohammed MA, Mahmood A, Zubaidi A, Al-Obeed O, Khan Z, Abdulla M, Ahmad R, Novel derivative of aminobenzenesulfonamide (3c) induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through ROS generation and inhibits cell migration, BMC Cancer 17(1) (2017) 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huynh DL, Zhang JJ, Chandimali N, Ghosh M, Gera M, Kim N, Park YH, Kwon T, Jeong DK, SALL4 suppresses reactive oxygen species in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma phenotype via FoxM1/Prx III axis, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 503(4) (2018) 2248–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Guan L, Zhang L, Gong Z, Hou X, Xu Y, Feng X, Wang H, You H, FoxO3 inactivation promotes human cholangiocarcinoma tumorigenesis and chemoresistance through Keap1-Nrf2 signaling, Hepatology 63(6) (2016) 1914–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Das TP, Suman S, Alatassi H, Ankem MK, Damodaran C, Inhibition of AKT promotes FOXO3a-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer, Cell Death Dis 7 (2016) e2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Liu Z, Shi Z, Lin J, Zhao S, Hao M, Xu J, Li Y, Zhao Q, Tao L, Diao A, Piperlongumine-induced nuclear translocation of the FOXO3A transcription factor triggers BIM-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells, Biochem Pharmacol 163 (2019) 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Liu Y, Ao X, Ding W, Ponnusamy M, Wu W, Hao X, Yu W, Wang Y, Li P, Wang J, Critical role of FOXO3a in carcinogenesis, Mol Cancer 17(1) (2018) 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shiota M, Song Y, Yokomizo A, Kiyoshima K, Tada Y, Uchino H, Uchiumi T, Inokuchi J, Oda Y, Kuroiwa K, Tatsugami K, Naito S, Foxo3a suppression of urothelial cancer invasiveness through Twist1, Y-box-binding protein 1, and E-cadherin regulation, Clin Cancer Res 16(23) (2010) 5654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ma Z, Xin Z, Hu W, Jiang S, Yang Z, Yan X, Li X, Yang Y, Chen F, Forkhead box O proteins: Crucial regulators of cancer EMT, Semin Cancer Biol 50 (2018) 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dalla Pozza E, Fiorini C, Dando I, Menegazzi M, Sgarbossa A, Costanzo C, Palmieri M, Donadelli M, Role of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 in cancer cell resistance to gemcitabine, Biochim Biophys Acta 1823(10) (2012) 1856–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]