Abstract

Context

The high prevalence and negative implications of resident physicians’ burnout is well documented, yet few effective interventions have been identified.

Objective

To document resident and faculty perspectives on resident burnout, including perceived contributing factors and their recommended strategies for attention and prevention.

Design

We conducted 14 focus groups with core faculty and residents in 5 specialties at a large integrated health care system in Southern California. Training programs sampled included family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. Discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a matrix-based approach to identify common themes.

Main Outcome Measures

Resident and faculty perspectives regarding causes of burnout, preventive factors, and potential intervention strategies.

Results

Five themes captured the range of factors participants identified as contributing or protective factors for resident burnout: 1) having or lacking a sense of meaning at work; 2) fatigue and exhaustion; 3) cultural norms in medicine; 4) the steep learning curve from medical school to residency; and 5) social relationships at and outside work. Recommended intervention strategies targeted individuals, residents’ social networks, and the learning and work environment.

Conclusion

We engaged residents and core faculty across specialties in the identification of factors contributing to burnout and possible targets for interventions. Our results highlight potential focus areas for future burnout interventions and point to the importance of interventions targeted at the social environments in which residents’ work and learn.

Keywords: burnout, focus groups, internship and residency, job satisfaction, professional psychology, physician psychology, social support, workplace

INTRODUCTION

The high prevalence and negative effects of burnout among resident physicians are well documented. Previous research cites suicide as the first and second leading cause of death among male and female residents, respectively,1 and other studies link burnout to additional poor resident health outcomes and suboptimal patient care.2

Outcomes research regarding effective interventions of resident burnout, however, remains limited and produces mixed results.3 Additionally, research has focused more on causes than protective factors,4 leaving us with a better understanding of pathology than prevention.5 Researchers recommend engaging residents and faculty in the identification of contributing and protective factors to inform future approaches for improving the well-being of residents.6 This approach could identify specific targets for intervention, yield insights into the most favorable and feasible approaches, and, by involving key stakeholders in the design and implementation, could reduce burnout.7

To date, few studies have engaged both residents and faculty, focusing mostly on residents.8,9 Faculty may have differing insights given their vantage point, exposure to multiple cohorts of residents, connection to leadership, and the power to enact systematic change. Our study aimed to understand how residents and faculty from various specialties understand resident burnout and what they recommend as strategies for addressing it.

METHODS

From October 2016 to February 2017, we conducted 14 focus groups with core faculty and residents in 5 specialties at a large integrated health care system in Southern California. Participants were recruited from medical centers in 2 cities: Los Angeles and Fontana. Sampled programs included family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. One focus group per program was conducted with core faculty and another with residents.

All residents and core faculty from included programs were emailed invitations to participate in a focus group at a predetermined time. Anyone who presented the day of the focus group was allowed to participate. Focus groups were held in a private room at the medical center. Separate guides were developed for faculty and resident discussions (see Appendix, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2019/18-185-App.pdf). The moderator (KI) had no reporting relationships with residents or faculty in any of the participating programs and a neutral note taker was present during each focus group. Participants provided oral informed consent before discussions began. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed; all identifiers were removed before analysis. After each focus group, participants were provided with information on available resources for addressing burnout. The organization’s institutional review board approved the study.

The study team developed a preliminary code list on the basis of the topic guides and used this to code several transcripts. The team then revised the code list, incorporating new codes with definitions and examples. Two team members (KI and DB) coded all remaining transcripts using the Dedoose application.10 Framework, a matrix-based approach, was used to analyze results and identify themes.11 Further analysis was later conducted to determine whether particular themes were present or absent in each focus group (ie, faculty vs residents, or groups conducted with participants in specific specialties). Quotes are included to illustrate themes and were identified using codes to indicate group type and number (eg, F1 indicates Faculty, Group 1, and R4 indicates Residents, Group 4).

RESULTS

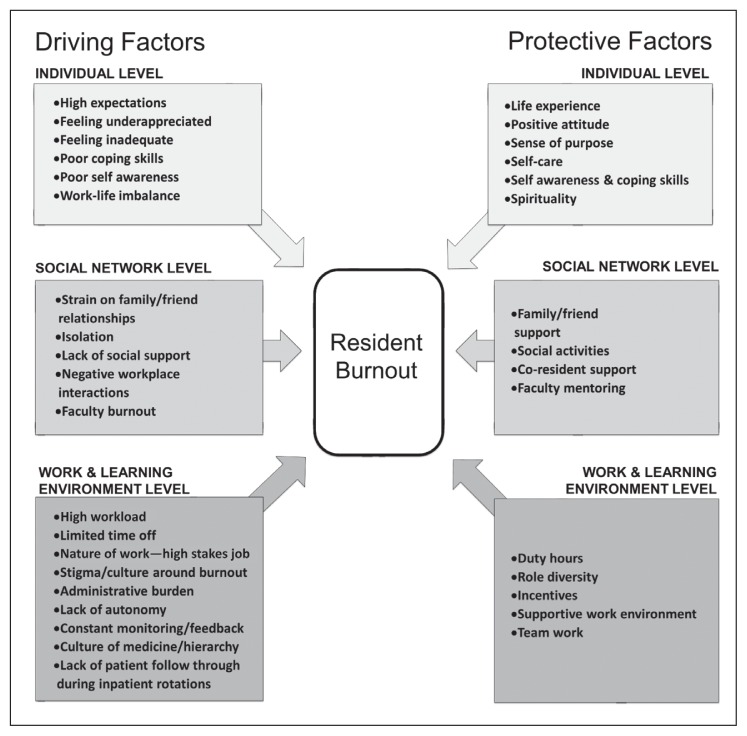

Among residents, 72 (40%) of 181 who were eligible participated. Among core faculty, 48 (52%) of 92 eligible faculty members participated. On average, there were 10 participants per resident group (range = 6–16), and 7 per faculty group (range = 3–12). Of residents in the sample, 42% were men; 33% were postgraduate year (PGY) 1, 33% were PGY 2, 31% were PGY 3, and 3% were PGY 4, similar to the proportions for residents overall in the programs. More than half (54%) of the faculty in the sample were men, which is similar to the proportion for core faculty overall in the programs. Participants identified multiple factors as contributing to and protecting residents from burnout (Figure 1). We found similarities in factors identified among faculty and residents, as well as between medical specialties. Five cross-cutting themes tied these factors together.

Figure 1.

Driving and protective factors of residents’ burnout.

Sense of Meaning and Purpose

Time spent on administrative tasks vs direct patient care resulted in disengagement and residents’ reduced sense of meaning in their work, which contributes to burnout: “The administrative [work] is 85% to 90% of my day … the 10% I get to be with patients is why I did medicine (R4).” Residents believed that faculty overemphasize administrative tasks, which they attribute to regulatory pressures, and felt scrutinized based on the accuracy of medical coding over their performance in patient care.

Poor follow-through with patients also detracts meaning from a resident’s work and becomes a missed opportunity for learning and improvement around patient care: “They [residents] don’t actually see the patients that they admit, so even [if] they could’ve followed the patient ... there is no feedback and reinforcement of how you did, you just get dinged if you missed coding (F4).”

Job-related factors that make work meaningful include seeing positive outcomes, a sense of progress, feeling contributions are appreciated and important, learning, feeling part of a team, diversity in work tasks including opportunities to teach, and having input into decision making. Additionally, both faculty and residents described individual factors influencing residents’ ability to find meaning in their work: Possessing a positive outlook, coping skills, resilience, spirituality, maturity, and maintaining interests or hobbies outside medicine.

Fatigue and Exhaustion

Aspects of residents’ work that contribute to fatigue and exhaustion also contribute to burnout: Long hours, the need to come into work early, and limited time off preclude protective behaviors such as exercise, sleep, and work-life balance. Heavy workloads result in an erosion of boundaries between work and home and interrupt educational activities. Faculty acknowledged that residents receive mixed messages about whether to prioritize educational activities or patient care.

Time spent at work is stressful because of time constraints and the urgent nature of tasks. This contributes to negative thoughts and feelings about not making progress and never having done enough. “One of the reasons you get so burn[ed] out is … you don’t even feel like you’re providing good care (R4).” A sense of urgency was also seen as detracting from learning: “Just the pure pressure and constancy of that urgency … there’s no time to reflect or think about your patients (F4).” The demanding nature of work also makes it challenging for residents to pursue self-care: “It’s easy to get caught up in the flow of it and disregard your own feelings and basic needs (R5).”

Residents cited the high stakes of the job as being emotionally taxing: “These are people’s lives in our hands (R7).” Residents described difficulty establishing appropriate boundaries with patients, at times becoming too emotionally involved and using desensitization as a self-protective mechanism: “You have to find ways of coping … like callous humor or minimizing things … because if you didn’t, then it would weigh pretty heavily on you (R5).”

Spending time away from work to reset and rejuvenate, obtaining adequate sleep, engaging in exercise and hobbies, maintaining a life outside work, and stress management are factors cited as helping to prevent exhaustion.

Cultural Values of Medicine

Participants reported that cultural values in medicine contribute to burnout, including stigma of burnout and expectations that physicians be “superhuman (R2).” “Residency in general has a culture of [having] to pretend you’re okay (R2).” Reaching out to colleagues for help is difficult because of these cultural beliefs: “You don’t want to complain to your colleagues because it’s … admitting to your inability to keep up (R6).”

Being burned out is sometimes normalized, for example, “I don’t think anybody gets through residency without being burned out at some point. (F3)” Alternatively, burnout is seen as an impossible problem to resolve without major structural changes, which participants thought were unlikely to occur: “It doesn’t always seem like there are viable alternatives. ... [A]re you gonna work less (R6)?” The need for, and futility in pursuing, system-level changes as a solution was emphasized: “The necessity of residents to do the main work of the hospital is inherent in residency, and so there’s no way to support us in some of the stuff that leads us to exhaustion and hopelessness, without the hospital taking a huge financial and workload hit (R4).”

Other shared cultural beliefs support prioritizing work over personal time and self-care. Residents described feeling guilty about taking time off: “I feel like I’m never sick enough to prove I’m sick (R2).” Organizational messages also signal that residents should prioritize patients’ needs over their own: “You’re always being told the patient comes first (R4).”

Faculty acknowledged poor self-care themselves, making it challenging for them to be role models for residents: “I could teach you a differential, but if I don’t know self-care, how am I gonna teach you that (F6)?” Some faculty expressed beliefs about the current generation of residents (the Millennials, or Generation Y) as being less tolerant than previous generations. In several faculty focus groups, participants described residents as more prone to complain, sensitive to negative feedback, and having unrealistic expectations.

Residents are familiar with these faculty beliefs, viewing them as unfair and lacking acknowledgment of major changes that have occurred in medicine: “I am covering over 100 patients at a time and [don’t] feel like I’m doing meaningful work bedside with the patient. … [T]he work has changed so much that I think we are having higher levels of burnout because the work we do is less fulfilling (R4).” Residents sometimes feel shut down by faculty comments about generational differences that marginalize their experiences.

Steep Learning Curve

Transitioning from medical school to residency involves a steep and inherently stressful learning curve, with a tremendous amount of information to absorb and increased responsibilities: “One minute ago you didn’t have any responsibility, and now you’re in charge and you have to make decisions and it affects people’s lives (F6).” During this transition, residents struggle with feelings of self-doubt and insecurity. Frequent performance feedback, typically highlighting weaknesses and areas for improvement, exacerbates these feelings. Faculty acknowledged that residents receive an excessive amount of feedback, which is not always delivered in an optimal fashion or time. However, they commented that current residents seem to have a particularly hard time accepting feedback, which they attributed to generational differences: “They want to be perfect. They want you to tell them all the things they did great (F7).”

Residents acknowledged that having unrealistic expectations of themselves was a challenge and assumed that faculty share their high expectations. Poorly communicated faculty expectations, and uncertainty regarding whether they are being met, contribute to residents’ stress and anxiety.

Residents’ steep learning curve extended to facing a realistic understanding about what their career as a physician involves. Faculty noted that residents often romanticize their chosen profession and are disappointed when reality doesn’t match these expectations: “Medicine isn’t glamorous (F7).”

Social Relationships

With limited time to spend with family and friends, and a demanding job that is difficult for those outside the profession to understand, residents feel isolated from their usual sources of social support. Many residents are juggling multiple roles and responsibilities, including marriages, children, and aging parents, which exacerbates stress levels. Tense and hostile interpersonal interactions at work or challenging interactions with patients, families, ancillary staff, and faculty are sources of stress. Residents feel disrespected and unappreciated when told they are “just a resident” or when dedicated educational time is interrupted for nonurgent matters. Both residents and faculty also acknowledged faculty burnout as a problem and noted that faculty sometimes model “bad behaviors” or foster a “culture of complaining.”

Strong social support at home and at work protect residents from burnout, and the importance of peer support was emphasized. Several residents commented on positive experiences having seniors or chief residents reach out when they had been struggling: “When I was an intern … they really took care of me even on wards … and I try to pay it forward (R5).” The importance of social support from peers is the ability to relate: “A lot of people don’t understand what you’re going through except the people going through it (R7).” Informal opportunities to get together with other residents promotes connection and allows residents to process stressful experiences. Supportive and engaged faculty were also protective: “Sometimes you’ll have an attending who really cares about you, wants to teach, is invested in you. You don’t feel like you’re getting in the way (R1).”

Recommendations to Address Resident Burnout

Participants identified strategies to help prevent and mitigate the effects of burnout. These strategies targeted 3 levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strategies to reduce residents’ burnout and promote well-being, compiled from focus groups with residents and faculty

| Target | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Individual residents |

|

| Residents’ social networks, particularly peers and faculty |

|

| Learning and work environment |

|

Individual-Level Strategies

Participants recommended educating residents and faculty on the signs and symptoms of burnout, making support available to those experiencing symptoms, and additional education about resources available to residents. Faculty recommended educating residents on stress management techniques and coping skills, as well as strategies to find meaning and purpose in their work and establishing more realistic expectations. Some faculty also proposed screening for resilience during recruitment to identify candidates who may be less prone to burnout.

Social Network Strategies

Suggestions addressing the social network included peer-centered strategies: “Peer to peer is probably the most valuable. … They’re going to respect … the person next to [them] … going through the exact same challenges more than a person of designated authority (F6).” Social activities, team building, peer-to-peer mentoring, confidential discussions, and training residents to look for burnout in each other were all mentioned as opportunities for fostering connection.

Both residents and faculty mentioned the importance of addressing burnout in the faculty and recommended restructuring attitudes that stigmatize burnout or attribute it to generational differences. They also suggested intentional role modeling by faculty: “Being an example as to how you as a faculty member aren’t burned out, how you as a faculty member get day-to-day joy out of your practice, how you’ve found ways to get through your day and find meaning (F6).”

Learning and Work Environment Strategies

Some participants viewed systems factors as the most critical target for interventions, rather than individual strategies, such as relaxation techniques: “We’ve had Tai Chi people and yoga people and all those things, but I don’t think that is the solution. We’re not gonna yoga our way out of this. [Burnout] is literally a system issue (R4).” Participants suggested restructuring work to make it more meaningful for residents, increasing awareness and recognition of positive work outcomes, and providing opportunities to pursue personal interests through electives, teaching, and research.

Other areas identified as targets for interventions included the high workload, limited time off, and lack of control. Specific suggestions included dedicated time off for self-care, allowing residents to have greater control over their schedules, and creating an anonymous and confidential forum where residents could voice their concerns and see them addressed: “Not only a place to talk and be able to be heard, but also action is taken upon those things (R2).”

Changing the cultural environment to reduce the stigma of burnout and encourage and support wellness and self-care is also important to residents and faculty: “Making an environment where people feel like they can ask for help (R3).” Having faculty openly and frequently discuss burnout was recommended as a strategy to reduce stigma. Other recommendations included reducing conflict among the faculty, ensuring supportive leadership, and promoting faculty who are compassionate and reach out to residents: “Building a culture of wellness … a mindset of being intentional towards caring about residents? Do we reach out and say ‘hey, how are you doing today?’ or ‘is there anything we can do to help support you more’ (F1)?”

Residents and faculty also expressed the need for the integration of a proactive system to identify and support residents with burnout symptoms, such as conducting routine surveys, incorporating discussions of burnout into routine resident check-in meetings, standardizing a process for addressing burned-out residents, and hiring a mental health professional into the Graduate Medical Education Department.

DISCUSSION

Intervention strategies to address resident burnout are limited,3 and identification of new approaches to prevent and alleviate burnout is a priority.2 However, consensus regarding the critical issues that interventions should address, and the level at which they should be targeted is lacking. Sponsoring institutions and residency programs are confronted with an overwhelming number of potential resident wellness interventions that they might consider implementing. Our study sought to determine what residents and faculty, who have direct experiences with resident burnout, view as both contributing and protective factors, as well as how best they think burnout might be addressed. Our findings provide insights that may help focus future prevention efforts.

Although we expected to find differences between residents and faculty, these groups shared perspectives on both the contributing and protective factors of resident burnout, as well as potential interventions. Both groups viewed resident burnout as a problem with varied causes and recommended solutions targeting multiple levels: Individual residents, residents’ social networks, and the learning and work environment.12 Nevertheless, most factors identified as contributing to resident burnout were related to the learning and work environment. This finding is in accordance with previous research and theory, which characterizes burnout as a problem arising from the social environments in which people work, and not as a problem caused by the people working in those environments.2,13,14

Despite this, intervention approaches for physician burnout have predominantly focused on individuals, and not on work environments.3,13,15 An exception is the handful of studies that assessed how duty-hour restrictions affect resident burnout. A recent review concluded that restricting work hours reduced residents’ emotional exhaustion but did not have an impact on the other 2 domains of burnout: Depersonalization and low personal accomplishment.3 Various authors have called for additional interventions to address burnout that target residents’ learning and work environment.13,16,17

Our research yields insights about possible targets for interventions at the level of the learning and work environment. Our findings support Maslach and Leiter’s14 areas of work life framework, which identifies 6 domains of organizational factors as predictors of burnout: 1) workload, 2) control, 3) rewards, 4) community, 5) fairness, and 6) values. Residents and faculty in our focus groups connected all these factors to burnout. For example, the chronically unmanageable workload and excessive physical and emotional demands of the work were cited as contributing factors. Residents’ lack of control and autonomy was reported as a major source of stress. Residents also stated that a lack of reward for their work, both financial and nonfinancial, resulted in feeling unappreciated and that their work lacked meaning.

Residents also described feeling they were treated unfairly or disrespectfully because of their low status as a trainee. Conflicts between personal values and work also emerged, with residents reporting they thought their performance was suboptimal because of lack of time, support, or preparation. They also perceived the administrative tasks they spent a large amount of time on were not meaningful or educationally valuable, and at times they did not see their work as having clear benefits for patient welfare. A community of supportive peers and faculty was a protective element, as other studies have found.8,9,18

Improving the fit between residents and job conditions in any of these 6 domains is likely to improve residents’ work engagement and reduce burnout.14,17 Some work domains may be more easily transformed than others, and this framework provides multiple focus points to be leveraged for improvements. Many of the participant recommendations for intervention strategies were well aligned with this framework. Decreasing administrative work and improving systems for time off to support rest, recovery, and self-care will target workload. Fostering a culture of appreciation and recognition targets rewards. Allowing for more choice in work and vacation schedules, increasing electives, and creating a forum where residents can voice concerns targets autonomy. Increasing the amount of time residents spend on direct patient care vs administrative tasks targets personal values. Scheduled retreats and social activities, formal mentoring programs, and teamwork target community. There are various possibilities for how specific interventions can be designed to target these domains.17

Our study results also confirm that there are social and cultural norms in medicine that stigmatize burnout and make self-care a challenge for physicians.12,13,19 Cultural changes are needed to support healthier behaviors. Faculty served as role models for residents and can demonstrate healthy and productive attitudes and behaviors but can also reinforce existing cultural norms and stigma. Faculty members were at times burned out themselves, not surprising given their exposure to the same work environment as residents. Both residents and faculty commented that addressing faculty burnout was critical for addressing resident burnout.

Faculty beliefs about generational differences emerged as a salient theme in the focus groups. Some faculty acknowledged beliefs about Generation Y (the Millennial generation), to which most current residents belong, as being less motivated to work, more prone to complain, and having unrealistic expectations. These beliefs affected how faculty perceived residents and presented challenges for faculty in responding to residents’ distress. Residents reported direct exposure to these beliefs and thought that their experiences were at times discounted and not taken seriously by faculty.

Although most research on generational differences has occurred in industries outside health care, the literature has found real and measurable disparities, which should be acknowledged and addressed to create the most effective educational and clinical practice environments for everyone. Like what we heard in our focus groups, previous research has found that the Millennial generation places higher value on work-life integration, working in teams, receiving clear communication and frequent feedback, and having a close mentorship relationship with someone who can foster both professional and personal development.20,21 Additionally, the Millennial generation wants to believe their work has meaning, be acknowledged for their efforts, and feel valued for their contribution.22,23 Faculty development to support working with and teaching millennials may be beneficial.24 However, additional studies of generational differences (real and perceived) and their impact on faculty and residents in the health care industry are warranted.

Given the continued stigma associated with burnout, formal curriculum on burnout and wellness for residents and faculty is essential to provide accurate information on burnout prevalence, signs and symptoms, coping and self-care, and to make confidential support available. This may prove helpful for residents in identifying and supporting peers. So that the importance of the content is not undermined, this education should be incorporated into regularly scheduled didactics, and not as an add-on or optional curriculum. The stigma and normalization of burnout symptoms also underscore the importance of proactive systems to identify individuals experiencing burnout. Faculty reported a need for a clear protocol outlining how residents with burnout symptoms should be supported vs leaving this up to program discretion.

Residents and faculty identified the need for interventions targeted at individuals. One suggestion included fostering opportunities for residents to reflect on and connect with what brings meaning to their work. Job-related sources of gratitude and physician self-awareness are factors that have been reported by physicians as helping to promote resilience,25 and interventions to enhance these factors have demonstrated effectiveness.26 Another recommendation pertained to helping residents with setting realistic expectations. The transition from medical school to residency involves a steep learning curve, which is stressful and challenging for a resident’s perceived competence.9,18 This adjustment may also involve the reconciliation of idealized views of medicine with reality.18 Strategies to help residents establish realistic expectations during this inherently stressful transition, and to reinforce their competence, might be useful to enhance their well-being.27 Having faculty provide frequent positive feedback and explicit information on performance expectations may be an area of intervention related to these points. Clear benchmarks for performance could reduce anxiety associated with unclear expectations and would allow residents to evaluate their own performance against a standard. Positive feedback could bolster residents’ sense of confidence by reinforcing existing areas of competence. Formal mentoring programs might also help residents in establishing appropriate expectations.

Although we recruited participants from 2 medical centers in different cities in Southern California, our research is limited by the fact that residents were recruited from a single institution. It is possible that the views expressed by the participants in this study do not reflect the views of other residents and faculty in different training programs or settings. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, we made efforts to help residents feel comfortable by holding separate groups by program, and by having a focus group moderator who was not directly affiliated with any of the residency programs. Despite our efforts to promote frank and open discussion, it is possible that some participants felt reluctant to express their honest views. Additionally, the resident focus groups were held with residents across training years. It is possible that participants’ views regarding factors contributing to burnout or interventions vary by training year,18 but this was not something explored in our research. Although our study identified many areas of focus for future interventions, additional research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these approaches.

CONCLUSION

Given the diverse factors that contribute to resident burnout, a silver bullet intervention is unlikely. Our results highlight potential focus areas for future burnout interventions and point to the importance of interventions targeted at the social environments in which residents work and learn. Other residency programs and sponsoring institutions may wish to consider implementing a similar effort to engage residents and faculty in understanding causes of burnout and recommended interventions. This will aid in identification of locally relevant solutions and may foster a greater sense of ownership in whatever strategies are ultimately implemented.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Yaghmour NA, Brigham TP, Richter T, et al. Causes of death of residents in ACGME-accredited programs 2000 through 2014: Implications for the learning environment. Acad Med. 2017 Jul;92(7):976–83. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016 Jan;50(1):132–49. doi: 10.1111/medu.12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busireddy KR, Miller JA, Ellison K, Ren V, Qayyum R, Panda M. Efficacy of interventions to reduce resident physician burnout: A systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Jun;9(3):294–301. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00372.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebensohn P, Dodds S, Benn R, et al. Resident wellness behaviors: Relationship to stress, depression and burnout. Fam Med. 2013 Sep;45(8):541–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009 Feb;84(2):269–77. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938a45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slavin SJ, Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Acad Med. 2016 Sep;91(9):1194–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daskivich TJ, Jardine DA, Tseng J, et al. Promotion of wellness and mental health awareness among physicians in training: Perspective of a national, multispecialty panel of residents and fellows. J Grad Med Educ. 2015 Mar;7(1):143–7. doi: 10.4300/JGME-07-01-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutherford K, Oda J. Family medicine residency training and burnout: A qualitative study. Can Med Educ J. 2014 Dec 17;5(1):e13–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedoose Version 7.0.23, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data [Internet] Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC; 2016. [cited 2019 Feb 15]. Available from: www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social scientist students and researchers. London, UK: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sklar DP. Fostering student, resident, and faculty wellness to produce healthy doctors and a healthy population. Acad Med. 2016 Sep;91(9):1185–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery A. The inevitability of physician burnout: Implications for interventions. Burn Res. 2014 Jun 1;1(1):50–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maslach C, Leiter MP. New insights into burnout and health care: Strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2017 Feb 1;39(2):160–3. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Feb 1;177(2):195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslach C. Burnout and engagement in the workplace: New perspectives. Eur Health Psychologist. 2011 Sep 1;13(3):44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident wellness matters: Optimizing resident education and wellness through the learning environment. Acad Med. 2015 Sep 1;90(9):1246–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satterfield JM, Becerra C. Developmental challenges, stressors and coping strategies in medical residents: A qualitative analysis of support groups. Med Educ. 2010;44(9):908–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slavin SJ. Medical student mental health: Culture, environment, and the need for change. JAMA. 2016 Dec 6;316(21):2195–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourenco AP, Cronan JJ. Teaching and working with millennial trainees: Impact on radiological education and work performance. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017 Jan;14(1):92–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boysen PG, 2nd, Daste L, Northern T. Multigenerational challenges and the future of graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2016 Spring;16(1):101–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M. Go ahead and fire me!: The top three things generation Y does not like about working @ your medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014 Jul-Aug;30(1):60–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cahill TF, Sedrak M. Leading a multigenerational workforce: Strategies for attracting and retaining millennials. Front Health Serv Manage. 2012 Fall;29(1):3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eckleberry-Hunt J, Tucciarone J. The challenges and opportunities of teaching ‘generation Y’. J Grad Med Educ. 2011 Dec;3(4):458–61. doi: 10.4300/JGME-03-04-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwak J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. 2013 Mar;88(3):382–9. doi: 10.1097/acm.0b013e318281696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009 Sep 23;302(12):1338–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ten Cate OT, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2011 Dec 1;33(12):961–73. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.595435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]