Abstract

Context:

The objective of this systematic review was to update a prior review and summarize the evidence on the impact of family planning reminder systems (e.g., daily text messages reminding oral contraception users to take a pill).

Evidence acquisition:

Multiple databases, including PubMed, were searched during 2016–2017 for articles published from March 1, 2011, to November 30, 2016, describing studies of reminder systems.

Evidence synthesis:

The search strategy identified 24,953 articles, of which two studies met the inclusion criteria. In total with the initial review, four studies (including two RCTs) examined reminder systems among oral contraception users, with two of three that examined correct use finding a statistically significant positive impact, and one RCT finding a positive impact on knowledge and continuation. Of three studies (including two RCTs) that examined reminder systems among depot medroxyprogesterone acetate users, one of three that examined correct use found a statistically significant positive impact on timely injections at 3 months, and one study found no effect on continued use at 12 months.

Conclusions:

Although this review found mixed support for the effectiveness of reminder systems on family planning behaviors, the highest quality evidence yielded null findings related to correct use of oral contraception and timely depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections beyond 3 months, and found positive findings related to oral contraception continuation and knowledge. Future studies would be strengthened by objectively measuring outcomes and examining additional contraceptive methods and outcomes at least 12 months post-intervention.

Theme information:

This article is part of a theme issue entitled Updating the Systematic Reviews Used to Develop the U.S. Recommendations for Providing Quality Family Planning Services, which is sponsored by the Office of Population Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CONTEXT

Nearly half (45%) of U.S. pregnancies each year are unintended,1 meaning that at the time the pregnancy occurred, the pregnancy was unwanted or the woman became pregnant earlier than desired. Approximately 40% of unintended pregnancies occur among women who used their contraceptive method inconsistently or incorrectly.2 User-dependent contraceptive methods (e.g., oral contraception, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA] injections, and condoms) require adherence by users to ensure method effectiveness, thus accounting for differences in typical and perfect use failure rates.3 Typical use failure rates refer to the effectiveness of different methods during actual use, including inconsistent or incorrect use, whereas perfect use failure rates refer to method effectiveness when users follow directions for use. Examination of population-based data has found disparities in contraceptive failure rates among subgroups of women, including those who are younger, those who belong to certain racial or ethnic minority groups, those who are cohabiting, and those with lower incomes.4

Non-adherence to combined hormonal contraception (e.g., not taking oral contraception pills as prescribed) increases the risk of ovulation5 and side effects (e.g., bleeding irregularities) that may lead to discontinuation6 and periods of non-coverage. DMPA users must also maintain regular dosing schedules because injections must be received within 14 weeks of a previous injection to ensure effective contraceptive action. Condoms require use during each act of intercourse during fertile periods to protect against unintended pregnancy. Given the importance of correct and continued contraceptive use to prevent unintended pregnancy and reduce the occurrence of side effects, it is important to identify interventions that can improve family planning behaviors and effectiveness among users. Reminder systems—interventions intended to remind patients of some behavior to achieve a reproductive health goal, such as taking a pill, attending a clinic visit to receive a DMPA injection, or using a condom—are promising approaches.

During 2010–2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Office of Population Affairs conducted a systematic review summarizing the evidence on the impact of reminder systems in clinical settings to improve family planning outcomes.7 That review assessed all relevant evidence published from January 1, 1985, to February 28, 2011. Along with expert feedback and findings from two other complementary systematic reviews on the impact of contraceptive counseling and education in family planning programs,8,9 the information was used to develop national recommendations for providing quality family planning services.10

The objective of this systematic review is to summarize the body of evidence since the initial review. A cumulative assessment of the evidence is provided by combining findings from this and the initial review.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

This systematic review is reported according to the PRISMA checklist.11 The methods for conducting this updated systematic review were similar to the approach used in the prior reviews and have been described elsewhere.12 Briefly, five key questions (KQs) were developed (Table 1) and an analytic framework (Appendix Figure 1, available online) applied to show the logical relationships between the population of interest (women of reproductive age receiving family planning services in a clinical setting); the reminder system intervention; and the outcomes of interest (long-term, medium-term, and short-term outcomes and client experiences). Search strategies were then developed that included the identification of key terms (Appendix Table 1, available online), which were used to search multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, to identify potential articles published from March 1, 2011, to November 30, 2016.

Table 1.

Key Questions for Updated Systematic Review on Impact of Reminder Systems in Clinical Settings

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| Q1 | Is there a relationship between the utilization of reminder systems and improved long-term outcomes of family planning services (i.e., decreased teen or unintended pregnancies, decreased abortion rates, increased birth spacing, increased achievement of desired family size, improved infant health, increased value-based care, decreased per capita costs, high return on investment)? |

| Q2 | Is there a relationship between the utilization of reminder systems and improved medium-term outcomes of family planning services (i.e., increased contraceptive use, increased use of more effective contraception, increased correct use of contraception, increased consistent use of contraception, increased continuation of contraception use, increased use of dual contraceptive methods, increased use of services, increased repeat or follow-up service use)? |

| Q3 | Is there a relationship between the utilization of reminder systems and improved client experiences (e.g., perception that services are client-centered and equitable, satisfaction with services) or short-term outcomes of family planning services (i.e., increased knowledge or awareness, increased participation in the decision-making process, increased intentions to use contraception, increased intentions to use services, increased acceptance by the community, strengthened social norms, improved parent or partner involvement or community, increased intentions to delay sexual initiation, enhancement of other psychosocial determinants of contraceptive use)? |

| Q4 | What are the barriers and facilitators for clinics to offering reminder systems or for clients to achieving positive outcomes after utilizing reminder systems in the family planningsetting? |

| Q5 | Are there any unintended negative consequences associated with offering reminder systems in the family planningsetting? |

Note: Questions are put into context by the analytic framework presented in Appendix Figure 1 (available online).

Selection of Studies

Retrieval and inclusion criteria were developed a priori and applied to the search results. Eligible studies met the following criteria: conducted in the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or European countries categorized as “very high” on the Human Development Index13; published in English from March 1, 2011, to November 30, 2016; described a study that addresses at least one KQ; and were full-length articles (abstracts and letters to the editor were excluded). RCTs, nonrandomized trials, cohort, and case-control studies were included. Articles also had to evaluate a reminder system intervention in a clinic-based setting where family planning services were provided. Studies that focused solely on prevention of HIV or sexually transmitted infections, without a family planning component, or focused solely on males, were not considered.

Some inclusion criteria were specific to KQs. KQs 1–3 sought to examine the relationships between utilization of reminder systems and improved long-, medium-, and short-term outcomes and client experiences; thus, a comparison group was required for the study to be included. Among included studies, those that also examined barriers and facilitators or unintended negative consequences met the inclusion criteria for KQ 4 or 5.

Data Abstraction, Assessment of Study Quality, and Synthesis of Data

Detailed information was abstracted by a team of four abstractors and reviewed by two authors for relevance to contraceptive counseling; differences were reconciled by consensus. The quality of each piece of evidence was assessed using the grading system developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and risk of bias was rated as low, moderate, or high.14 As different types of reminder systems are appropriate for different contraceptive methods, findings are reported by contraceptive method. Only newly identified studies from the updated search are summarized in detail in the text, although the total body of evidence from both the initial and updated searches are fully described in the evidence tables. Table 2 summarizes the evidence base among oral contraception users, and Table 3 summarizes the evidence base among DMPA users. Appendix Table 2 (available online) describes the details of each study. Summary measures of association were not computed across studies because of the diversity of the interventions, study designs, and populations.

Table 2.

Summary of Impact of Reminder Systems for Oral Contraception Users

| Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-term | Short-term | |||||

| Reference | Quality | Follow-up | Increased correct use of contraception | Increased continuation of contraceptive use | Increased knowledge | Total outcomes with positive impact for studya |

| Lachowsky (2002)15 | Level II-2; high risk for bias | 3–6 months | ↑ | NA | NA | 1/1 |

| Fox (2003)16 | Level II-1; high risk for bias | 3 months | ↑ | NA | NA | 1/1 |

| Hou (2010)17 | Level I; moderate risk for bias | 3 months | ↔ | NA | NA | 0/1 |

| Hall (2013)b,18 Castano (2012)b,19 |

Level I; moderate risk for bias | 6 months | NA | ↑ | ↑ | 2/2 |

| Total studies with positive impacta | 2/3 | 1/1 | 1/1 | |||

Note: ↑ statistically significant positive impact; ↓ statistically significant negative impact; ↔ no evidence of a statistically significant impact.

Statistically significant.

Newly identified since 2015 review.

NA, not assessed.

Table 3.

Summary of Impact of Reminder Systems for DMPA Users

| Medium-term outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Quality | Follow-up | Increased correct use of contraception | Increased continuation of contraceptive use | Total outcomes with positive impact for studya |

| Madlon-Kay (1996)20 | Level II-2; high risk for bias | 3 months | ↑ | NA | 1/1 |

| Keder (1998)21 | Level I; high risk for bias | 12 months | ↔ | ↔ | 0/2 |

| Trent (2015)b,22 | Level I; high risk for bias | 9 months | ↔ | NA | 0/1 |

| Total studies with positive impacta | 1/3 | 0/1 | |||

Note: ↑ statistically significant positive impact; ↓ statistically significant negative impact; ↔ no evidence of a statistically significant impact.

Statistically significant.

Newly identified since 2015 review.

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; NA, not assessed.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

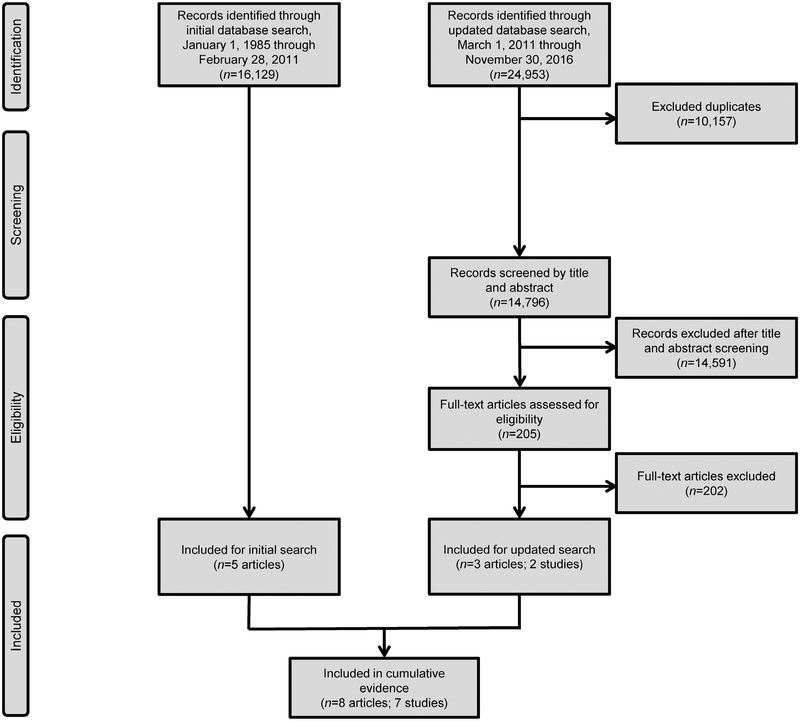

For the updated review, the search strategy identified 24,953 articles (Figure 1). After removal of duplicates (n=10,157) and applying the retrieval criteria, 205 full-text articles were reviewed. Of these, two studies (described in three articles) met the inclusion criteria.18,19,22 Findings from two articles among oral contraception users are described together as a single piece of evidence because they used the same reminder system intervention and included the same sample of participants18,19; only the most recently published article from this study will be referenced in text moving forward.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Both newly identified studies were RCTs, one rated as having moderate risk for bias18 and the other rated as having high risk for bias.22 Both studies examined medium-term outcomes (continuation of oral contraception and correct use of DMPA [i.e., timely injections])18,22; one study also examined knowledge.18 Neither of the newly identified studies examined long-term outcomes, client experiences, unintended negative consequences associated with offering reminder system interventions, or barriers or facilitators facing clinics or clients related to offering or using reminder system interventions. Sample sizes ranged from 10022 to 962,18 and participants from both studies were adolescents or women aged ≤ 25 years. Both studies recruited participants from urban health facilities, one from a family planning health center18 and the other from an academic general pediatric and adolescent medicine practice.22

Oral Contraception Users

The newly identified study that examined the impact of a reminder system intervention among oral contraception users found a statistically significant positive impact on continuation and knowledge at 6 months.18 This RCT included 962 sexually active women aged ≤ 25 years who owned a cell phone with text messaging functionality and requested oral contraception. Participants were randomized to receive or not receive 180 text messages over 6 months, sent daily at a designated time chosen by the woman to serve as a reminder to take their daily oral contraceptive pill. The messages included an introductory message, three reminders of how to change contact information or message time, 47 individual educational messages that were repeated up to four times, 12 two-way messages for quality control, and one concluding message. The educational text messages addressed six major dimensions of oral contraception knowledge, including mechanism of action, effectiveness, use, side effects, risks, and benefits. All women, regardless of study group, received protocol-based routine care, including contraceptive counseling by staff and an educational handout. At the 6-month follow-up, women in the intervention group had significantly (p=0.005) higher oral contraception continuation rates (n=480, 64%) compared with women in the control group (n=482, 54%, AOR=1.44, 95% CI=1.03, 2.00). Mean oral contraception knowledge scores were also significantly (p<0.001) higher at 6 months among women in the intervention group (25.5) compared with women in the control group (23.7), corresponding to a 7% and 3% increase in knowledge from baseline. In multivariable modeling, receipt of the text message intervention was the strongest predictor of mean 6-month oral contraception knowledge, with the intervention group compared with control group participants scoring an average of 1.6 points higher.

Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Users

The newly identified study that examined the impact of a reminder system intervention among DMPA users found a statistically significant positive impact on correct use (i.e., timely DMPA injections) for the first maintenance DMPA cycle after initiation (3 months), but not for the second or third maintenance cycles after initiation (6–9 months).22 This RCT included 100 adolescents aged 13–21 years using DMPA who had a cell phone with text messaging capability for personal use. Participants were randomized to receive or not receive an intervention that consisted of a welcome text message and daily text appointment reminders starting 72 hours before their scheduled clinic visit, with the option to cease the messages by responding with their plans to attend the visit. If the adolescent responded “no” that she could not attend her appointment, an e-mail was automatically sent to the nurse case manager who contacted the adolescent for rescheduling. The intervention group also received scheduled health messages regarding condom use for sexually transmitted infection prevention, healthy weight management, encouragement to call the nurse for problems, and a sexually transmitted infection screening reminder. All adolescents, regardless of study group, received standard of care, including an appointment card with the date of their next injection and automated clinic appointment reminders via home telephone. The proportion of adolescents who returned on time for their appointment was higher among those in the intervention group (n=50) compared with those in the control group (n=50) for the first (68% vs 56%) and second maintenance cycles after initiation (68% vs 62%), but not for the third maintenance cycle after initiation (73% vs 72%), although statistical testing was not reported. In linear regression analysis, adolescents in the intervention group returned sooner after scheduled appointments compared with those in the control group for the first maintenance cycle after initiation (p<0.05), but not for the second or third maintenance DMPA cycles after initiation. In this study, it is unclear if estimates were based on intent to treat, or if estimates were only among adolescents who returned for subsequent injections.

DISCUSSION

The cumulative review identified seven studies published from January 1, 1985, to November 30, 2016, that examined the impact of reminder system interventions in clinical settings among a broad age range of women (13–50 years) on family planning outcomes.15–18,20–22 In total, four studies examined the impact of daily reminder systems among oral contraception users,15–18 three examined correct use and found inconsistent findings,15,16,18 and one examined continued use and knowledge of oral contraception and found a modest impact on both outcomes. Three studies in total examined the impact of reminder systems among DMPA users20–22; all three examined correct use and found inconsistent findings,20–22 and one examined continued use and did not find a statistically significant positive impact.21 Three studies included in the body of evidence examined either barriers for clients to achieving positive outcomes after utilizing reminder systems or barriers for clinics to offering reminder systems.16,17,21 No studies from the original or updated searches identified studies of reminder system interventions that examined long-term outcomes, client experiences, or unintended negative consequences associated with reminder system interventions.

The three studies that examined the impact of reminder systems on correct use of oral contraception were from the initial review. Two found a statistically significant positive impact of the reminder system on perfect oral contraception adherence during three cycles. However, both assessed adherence via self-report and had high risk for bias. One was a retrospective historical nonrandomized controlled trial that examined daily e-mail messages,16 and the other was a prospective cohort study that examined use of a small reminder device that emitted a daily audible beep.15 The third study from the initial review used a stronger design (RCT) and a more objective measure of adherence (an electronic monitoring device that sent a wireless signal each time participants opened the device to remove a pill),17,23,24 although it was also rated as having high risk for bias. In contrast to the first two studies, this third study found no significant impact of daily text messages on oral contraception adherence over 3 months.17

The one study that examined continued use of oral contraception and oral contraception knowledge was an RCT rated as having moderate risk for bias identified during the review update that used self-reported data to examine the effect of daily educational text messages for 6 months. This study found a significant modest effect on continuation and knowledge, which in other research has been associated with contraception adherence.25 Of note, the continuation rates at 6 months in both the intervention and control groups were lower than the 6-month oral contraception continuation rate reported from a large, prospective observational cohort study.26

Of the three studies that examined the impact of reminder systems on correct use of DMPA20–22 two were from the original review.20,21 One study from the original review was a retrospective cohort study conducted via chart review and rated as having high risk for bias20; this study found a statistically significant impact of receiving a wallet-sized reminder card with the date of the next DMPA injection and a reminder postcard shortly before the next injection appointment. The other two studies, one from the original review21 and one from the review update,22 had stronger designs (RCT), although both were rated as having high risk for bias. Both assessed timeliness of DMPA injections over longer follow-up periods (9–12 vs 3 months), with no significant effect of either a reminder letter 2 weeks prior to the upcoming injection appointment and repeated phone calls if an appointment was missed21 or daily text appointment reminders starting 72 hours before the upcoming injection appointment.22 The one study that examined the impact of a reminder system on continued use of DMPA, identified during the initial review, did not find a statistically significant positive effect of the intervention on DMPA continuation rates at the 12-month follow-up.21

The three studies that examined either barriers for clients to achieving positive outcomes after utilizing reminder systems or barriers for clinics to offering reminder systems16,17,21 were all from the original review. Barriers for clients included costs associated with using the reminder system16,17 and not being able to individualize the time the reminder message was received.16 Barriers for clinics included reminder systems that were too intensive to be incorporated easily into most office settings (e.g., repeated phone calls, facilitation of appointment re-scheduling).21

The effect of reminder systems in other areas of health behavior has been reported. Personal reminders, such as telephone calls or e-mails from healthcare providers, to patients have been shown to improve medication adherence for chronic disorders (e.g., hypertension),27,28 as have electronic reminders automatically sent from healthcare providers to patients.29 One systematic review examined the use of mobile phone text message reminders in healthcare services (mostly related to HIV and diabetes) and found that about three quarters of 60 studies included in the review found improved outcomes, including medication adherence and appointment attendance.30 Another systematic review examined the effectiveness of texting and mobile phone app interventions among adolescents to improve adherence to a wide range of preventive behaviors (e.g., clinic attendance, physical activity, weight management, sun protection, smoking cessation) and found that about half of the included studies demonstrated significant improvements with moderate standardized mean differences.31 Another systematic review limited to RCTs on the effect of mobile phone–based interventions for improving contraception use specifically, which included three of the four RCTs included in this systematic review, concluded that there is limited evidence that interventions delivered by mobile phone can improve contraception use and that the cost effectiveness and long-term effects of these interventions remain unknown.32

The cost of implementing reminder systems likely varies by intervention type. The two studies in this review that reported cost as a barrier to clients reported a monthly charge of $5–$10 for the reminder system service, which consisted of either daily e-mails or text messages.16,17 Because the use of technology and availability of unlimited data plans has greatly changed since the time these studies were conducted, it is possible that cost to clients may no longer be an issue. No other studies included in this review presented data on intervention costs.

It may be that reminder systems to improve adherence with taking medications for health conditions that pose a risk to life have a greater potential to be effective. Women often have ambivalent feelings or conflicted desires toward pregnancy and having a baby,33–35 which may influence correct and continued contraceptive use irrespective of reminder systems. Whereas forgetfulness is a common reason reported for non-adherence to medications being used to treat medical disorders,29 contraceptive behaviors are also influenced by a complex host of factors including personal feelings and beliefs, concerns about side effects, changes in relationship status or partner influences, cultural values and norms, and healthcare system issues.2,36

The evidence summarizing the impact of reminder systems in clinical settings to improve family planning outcomes has several limitations, which should be considered when interpreting the evidence. Of the seven studies included in this review, none were determined to have a low risk for bias (i.e., high quality), and five were determined to have a high risk for bias (i.e., low quality).16,20–22 Studies were considered to be at risk for bias because of selection bias,15,16,21 self-report bias,15,16,18 recall bias,15,18 or short follow-up times for behavioral outcomes.16–18,20–22 Participation rates were low in one study18 and not reported in two studies.15,21 Some studies failed to report comparability between study groups16,20,22 and one included study groups that appeared to differ related to important background and reproductive health characteristics,15 limiting the ability to definitely attribute outcomes to the reminder system. Attrition bias was also an issue for some studies; one did not report the percentage of participants completing the study15 and two did not report the comparability between participants who completed and did not complete the study.16,20 One study was not powered to detect longitudinal efficacy of the intervention.22 Among the included RCTs,17,18,21,22 primary weaknesses included lack of18,22 or not reporting investigator blinding,21 not reporting on allocation concealment,21,22 and not reporting on randomization procedures.22 Last, given that contraceptive behaviors are influenced by a multitude of personal and relationship factors, it would have been helpful if studies had considered findings in light of potential changes in relationship status or pregnancy desires.

Despite these limitations, the evidence base for the impact of reminder system interventions in clinical settings on family planning outcomes also has several strengths. Four of seven studies in this review were RCTs,17,18,21,22 three of which used computer-generated randomization for group assignment.17,18,21 Two studies were conducted in multiple centers.15,16 One study followed participants for 12 months.21 Other strengths included high participation rates in two studies,17,22 high completion rates in one study,17 small differences in follow-up rates between study groups in two studies,17,18 and study groups with similar baseline characteristics in three studies.17,18,21 One study used an objective measurement of oral contraceptive adherence (i.e., electronic monitoring devices),17 and three studies validated information on DMPA injections using clinic records.20–22

At least one additional article meeting the inclusion criteria for this systematic review has been published since the systematic search of the literature. This article37 describes longer-term, post-trial data among a subset of adolescents from a study already included in this systematic review in which text reminders for an upcoming visit had no effect on timely DMPA injections.22 In the article,37 among 87 of the original 100 enrolled adolescents who completed three maintenance DMPA injection cycles, intervention participants had 3.65 increased odds of continuing to use DMPA or a contraceptive implant at the 20-month follow-up compared with control group participants (95% CI=1.26, 10.08). These findings are difficult to interpret given that youth who have already completed three maintenance DMPA injection cycles may be more motivated to continue using the method compared with youth who discontinued the method before the third maintenance injection.

CONCLUSIONS

Although this updated review found mixed support for the effectiveness of reminder system interventions, the studies with the most rigorous designs yielded null findings related to correct use of oral contraception and timely DMPA injections beyond 3 months, and found positive findings related to oral contraception continuation and knowledge. In general, these deductions are consistent with those from the initial review; only two new studies were added to the evidence base for this updated review. There is limited evidence available on the impact of reminder systems that makes it difficult to draw conclusions about when and for whom they might be effective. Technology is constantly changing, however, including advanced use of electronic medical records and patient portals, creating new opportunities to employ reminder system interventions to improve health outcomes, including those related to family planning. Future studies that examine the potential utility and cost effectiveness of reminder systems might be beneficial. These studies would be strengthened by objectively measuring outcomes and examining additional contraceptive methods and behavioral outcomes at least 12 months post-intervention.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This product was supported, in part, by a contract between the Office of Population Affairs and Atlas Research, Inc (HHSP233201500126I).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Office of Population Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to disclose.

THEME NOTE

This article is part of a theme issue entitled Updating the Systematic Reviews Used to Develop the U.S. Recommendations for Providing Quality Family Planning Services, which is sponsored by the Office of Population Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852. 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost JJ, Darroch JE, Remez L. Improving contraceptive use in the United States. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Inst). 2008(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trussell J Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397–404. 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaram A, Vaughan B, Kost K, et al. Contraceptive failure in the United States: estimates from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(1):7–16. 10.1363/psrh.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zapata LB, Steenland MW, Brahmi D, Marchbanks PA, Curtis KM. Effect of missed combined hormonal contraceptives on contraceptive effectiveness: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(5):685–700. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: a prospective evaluation of frequency and reasons. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(3, pt 1):577–582. 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Tiller M, Pazol K, Mautone-Smith N, Gavin LE. Impact of reminder systems in clinical settings to improve family planning outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 suppl 1):S57–S64. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pazol K, Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Mautone-Smith N, Gavin LE. Impact of contraceptive education on contraceptive knowledge and decision making: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 suppl 1):S46–S56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Curtis KM, et al. Impact of contraceptive counseling in clinical settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49 (2suppl 1):S31–S45. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tregear S, Gavin L, Williams J. Systematic review methodology: providing quality family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49 (2 suppl 1):S23–S30. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016: human development for everyone. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2016-report/. Published 2016. Accessed January 2018.

- 14.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21–35. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachowsky M, Levy-Toledano R. Improving compliance in oral contraception: the reminder card. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2002;7(4):210–215. 10.1080/ejc.7.4.210.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox MC, Creinin MD, Murthy AS, Harwood B, Reid LM. Feasibility study of the use of a daily electronic mail reminder to improve oral contraceptive compliance. Contraception. 2003;68(5):365–371. 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou MY, Hurwitz S, Kavanagh E, Fortin J, Goldberg AB. Using daily text-message reminders to improve adherence with oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):633–640. 10.1097/AOG.0-b013e3181eb6b0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall KS, Westhoff CL, Castano PM. The impact of an educational text message intervention on young urban women’s knowledge of oral contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(4):449–454. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castano PM, Bynum JY, Andres R, Lara M, Westhoff C. Effect of daily text messages on oral contraceptive continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119(1):14–20. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823d4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madlon-Kay DJ. The effectiveness of a mail reminder system for depot medroxyprogesterone injections. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(4):234–236. 10.1001/archfami.5.4.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keder LM, Rulin MC, Gruss J. Compliance with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: a randomized, controlled trial of intensive reminders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(3, pt 1):583–585. 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trent M, Thompson C, Tomaszewski K. Text messaging support for urban adolescents and young adults using injectable contraception: outcomes of the DepoText Pilot Trial. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(1):100–106. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potter L, Oakley D, de Leon-Wong E, Canamar R. Measuring compliance among oral contraceptive users. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(4):154–158. 10.2307/2136191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson HN, Borrero S, Lehman E, Velott DL, Chuang CH. Measuring oral contraceptive adherence using self-report versus pharmacy claims data. Contraception. 2017;96(6):453–459. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomaszewski D, Aronson BD, Kading M, Morisky D. Relationship between self-efficacy and patient knowledge on adherence to oral contraceptives using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):110 10.1186/s12978-017-0374-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Madden T, Secura G. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1083–1091. 10.1097/AOG.0-b013e3182a91f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marquez Contreras E, Vegazo Garcia O, Martel Claros N, et al. Efficacy of telephone and mail intervention in patient compliance with antihypertensive drugs in hypertension. ETECUM-HTA study. Blood Press. 2005;14(3):151–158. 10.1080/08037050510008977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waalen J, Bruning AL, Peters MJ, Blau EM. A telephone-based intervention for increasing the use of osteoporosis medication: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(8):e60–e70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vervloet M, Linn AJ, van Weert JC, de Bakker DH, Bouvy ML, van Dijk L. The effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):696–704. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kannisto KA, Koivunen MH, Valimaki MA. Use of mobile phone text message reminders in health care services: a narrative literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(10):e222 10.2196/jmir.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badawy SM, Kuhns LM. Texting and mobile phone app interventions for improving adherence to preventive behavior in adolescents: a systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(4):e50 10.2196/mhealth.6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith C, Gold J, Ngo TD, Sumpter C, Free C. Mobile phone-based interventions for improving contraception use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(6):CD011159 10.1002/14651858.CD011159.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JA, Popkin RA, Santelli JS. Pregnancy ambivalence and contraceptive use among young adults in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(4):236–243. 10.1363/4423612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cutler A, McNamara B, Qasba N, Kennedy HP, Lundsberg L, Gariepy A. “I Just Don’t Know”: an exploration of women’s ambivalence about a new pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(1):75–81. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones RK. Change and consistency in U.S. women’s pregnancy attitudes and associations with contraceptive use. Contraception. 2017;95(5):485–490. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clare C, Squire MB, Alvarez K, Meisler J, Fraser C. Barriers to adolescent contraception use and adherence. Int J Adolesc Med Health. In press. Online October 15, 2016 10.1515/ijamh-2016-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchanan CRM, Tomaszewski K, Chung SE, Upadhya KK, Ramsey A, Trent ME. Why didn’t you text me? Poststudy trends from the DepoText Trial. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(1):82–88. 10.1177/0009922816689674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.