Summary

The Xanthomonas group of phytopathogens causes several economically important diseases in crops. In the bacterial pathogen of rice, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo), it has been proposed that chemotaxis may play a role in the entry and colonization of the pathogen inside the host. However, components of the chemotaxis system, including the chemoreceptors involved, and their role in entry and virulence, are not well defined. In this study, we show that Xoo displays a positive chemotaxis response to components of rice xylem sap—glutamine, xylose and methionine. In order to understand the role of chemotaxis components involved in the promotion of chemotaxis, entry and virulence, we performed detailed deletion mutant analysis. Analysis of mutants defective in chemotaxis components, flagellar biogenesis, expression analysis and assays of virulence‐associated functions indicated that chemotaxis‐mediated signalling in Xoo is involved in the regulation of several virulence‐associated functions, such as motility, attachment and iron homeostasis. The ∆cheY1 mutant of Xoo exhibited a reduced expression of genes involved in motility, adhesins, and iron uptake and metabolism. We show that the expression of Xoo chemotaxis and motility components is induced under in planta conditions and is required for entry, colonization and virulence. Furthermore, deletion analysis of a putative chemoreceptor mcp2 gene revealed that chemoreceptor Mcp2 is involved in the sensing of xylem sap and constituents of xylem exudate, including methionine, serine and histidine, and plays an important role in epiphytic entry and virulence. This is the first report of the role of chemotaxis in the virulence of this important group of phytopathogens.

Keywords: environmental sensing, epiphytic infection, regulation, virulence, xylem sap

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria utilize complex signal transduction cascades to adopt to changes in environmental conditions by the sensing of surrounding environmental cues, such as the host environment, amino acids, sugars and phenolic compounds, and soil conditions, to perform directional motility by a process known as chemotaxis (Matilla and Krell, 2017; Szurmant and Ordal, 2004). Studies in Escherichia coli have elucidated the basic mechanism of the chemotaxis signal transduction system, which involves the sensing of chemotactic effectors or signals by membrane‐bound chemoreceptors. Binding of the chemosensory signal with a chemoreceptor induces a conformational change that leads to the activation and autophosphorylation of the cytoplasmic sensor kinase CheA, which then forms a complex with the chemoreceptor with the help of the adaptor protein CheW. Phosphorylated CheA then trans‐phosphorylates the response regulator CheY, which modulates flagellar motor activity. CheR (methytransferase) and CheB (methylesterase) are involved in pathway adaptation and, together with CheW, CheA and CheY, constitute the core components of the chemotactic signal transduction pathway (Parkinson et al., 2005, 2015; Wadhams and Armitage, 2004). In addition to these core chemotactic components, there are several other auxiliary proteins in diverse bacteria which have evolved to play a role in chemotaxis signal transduction pathways, such as CheD (deamidase), CheV and several phosphatases (CheC, CheZ and CheX) (Matilla and Krell, 2017; Wuichet and Zhulin, 2010).

In contrast with E. coli, several environmental bacteria, particularly plant and animal pathogens, exhibit complex chemotactic signal transduction systems, in which several chemotaxis pathways function in parallel to regulate multiple processes in addition to motility, such as the expression of virulence‐associated functions, modulation of regulatory intracellular cyclic nucleotide levels and development (Kirby, 2009; Matilla and Krell, 2017; Szurmant and Ordal, 2004). Although the complexity of the chemotaxis systems in bacteria has been proposed to play a role in adaptation to diverse fluctuating environmental conditions, their exact role in regulating virulence‐associated functions, the interplay of multiple chemotaxis signal transduction components and their mode of regulation are not well defined.

The Xanthomonas group of phytopathogens causes diseases in several economically important plants (Mansfield et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2011). Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) causes bacterial leaf blight (BLB), a serious disease of rice. Xoo gains entry into rice leaves through natural openings, called hydathodes, at the tip of the leaves and through wounds (Niňo‐Liu et al., 2006). In Xanthomonads, many virulence‐associated functions, such as extracellular polysaccharide, Type II and Type III secretion systems and their effectors, several two‐component sensors and response regulators, and cell–cell signalling, have been shown to be required for disease (Bűttner and Bonas, 2010; Shen and Ronald, 2002). In Xoo and Xanthomonas campestris, a pathogen of cruciferous plants, mutants defective in response regulators and cell–cell signalling exhibit altered chemotactic responses. However, these regulators are also involved in the regulation of several other cellular and virulence‐associated functions (Pandey et al., 2016; Rai et al., 2012; Yaryura et al., 2015). As these regulators are also involved in the modulation of several functions, the contribution of the chemotaxis signal transduction system per se on the entry, colonization and virulence of Xanthomonas remains poorly understood.

Xoo has a complex chemotaxis system consisting of several paralogues of the core chemotaxis components, auxiliary proteins and several putative chemoreceptors (Lee et al., 2005; Midha et al., 2017). In order to gain insights into the role of the chemotaxis system in Xoo entry, colonization and virulence, we performed detailed functional characterization of all the core and auxiliary components of this system. In this study, we demonstrate that Xoo exhibits chemotaxis towards xylem sap constituents and that the expression of chemotaxis components is induced under in planta conditions. We also show that Xoo exhibits a complex interplay of these chemotaxis signal transduction systems, which plays a role in chemotaxis‐driven motility, entry, colonization and regulation of virulence. In addition, we also identify the Xoo chemosensory receptor, mcp2, as being involved in the sensing of xylem sap and the constituents methionine and serine, and as being required for entry and virulence. Our results provide insights into the complex chemotaxis signal transduction system in Xoo that apparently contributes to the adaptation of this pathogen for its different lifestyles.

RESULTS

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae encodes four chemotaxis gene clusters

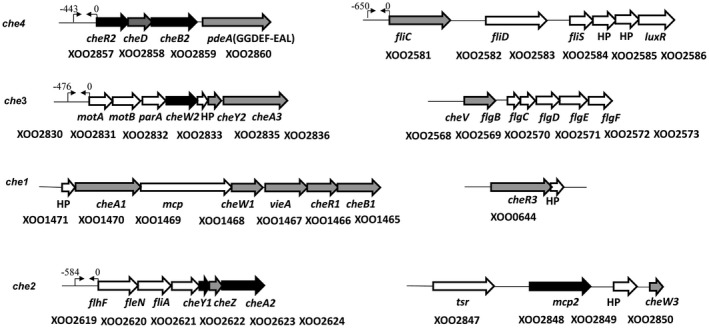

BLAST searches of the Xoo sequenced genomes (Altschul et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2005; Midha et al., 2017) with the nucleotide sequence of genes encoding proteins involved in core chemotaxis functions (CheA, CheW, CheY, CheR, CheB) from other bacteria revealed that Xoo harbours at least four chemotaxis (che) clusters, motility‐related operons, several putative chemoreceptors and chemotaxis auxiliary genes (cheD, cheV, CheZ) (Fig. 1; Table S1, see Supporting Information). Amongst the 13 putative core chemotaxis components of Xoo, nine are paralogues of CheA, CheR and CheW (three for each), and four are paralogues of CheY and CheB (two for each) (Fig. 1; Table S1). In order to understand the role of the complex chemotaxis system of Xoo in environmental sensing and virulence, we performed marker‐free, in‐frame deletion of each individual che gene paralogue, chemoreceptor mcp2 and fliC gene (see Experimental procedures; Tables S1 and S2, see Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Putative chemotaxis gene clusters in the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) genome. The representative organization of Xoo chemotaxis clusters (che1, che2, che3, che4) and motility‐associated functions. Arrows represent the open reading frame and the direction of transcription of Xoo chemotaxis and motility functions. The solid black arrows indicate the core components of the Xoo chemotactic signal transduction system (CheA2, CheR2, CheB2 and CheY1), paralogues of cheARBY, as determined by mutational and functional analysis. Arrows depicted as thin lines facing each other [→ ←] indicate the putative promoter sites relative to the transcriptional start sites of cheR2, motA, flhF and fliC operons.

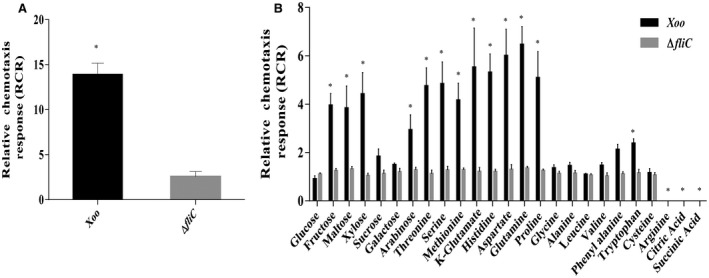

Chemotactic response of Xoo wild‐type strain towards xylem sap and components of xylem sap exudates

It has been shown that Xoo exhibits chemotaxis towards xylem exudates and components of xylem sap, such as glutamine and xylose (Feng and Kuo, 1975; Rai et al., 2012). In order to identify chemotaxis‐inducing compounds in Xoo, we performed syringe capillary assay to determine the chemotactic potential of Xoo towards xylem sap and components of xylem sap and exudate, including several amino acids, sugars and organic acids, such as methionine, glutamine and xylose (Bailey and Leegood, 2016; Feng and Kuo, 1975; Rai et al., 2012). Analysis of the relative chemotaxis response (RCR), which corresponds to the ratio of the number of bacteria in the test capillary to the number of bacteria in the control phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), for each respective strain indicated that wild‐type Xoo exhibited a significant chemotactic response (RCR; P < 0.01 by Student’s t‐test) towards xylem sap, fructose, maltose, xylose, arabinose, glutamate, glutamine, methionine, serine, threonine, aspartate, histidine and tryptophan compared with the ∆fliC mutant (Fig. 2). However, wild‐type Xoo did not exhibit a chemotactic response towards glucose, sucrose, galactose, glycine, leucine, cysteine and proline. Interestingly, Xoo exhibited a chemo‐repellent response towards arginine, citric acid and succinic acid (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Chemotaxis response of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) wild‐type strain to xylem sap and components of xylem exudate in the chemotactic capillary assay. Quantitative chemotactic capillary assay was performed with wild‐type Xoo and ΔfliC mutant 22‐µm filter‐sterilized xylem sap (A) and various sugars (1.8 mg/mL), amino acids [10 mg/mL, except for aspartate (5 mg/mL)], organic acids (1 mg/mL) and phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) (control) (B). The relative chemotaxis response (RCR), which corresponds to the ratio of the number of bacteria in the test capillary to the number of bacteria in the control (PBS), for each respective strain is shown. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). *Statistically significantly different values compared with the value of the ∆fliC (motility control) strain (Student’s t‐test; P < 0.001). The experiments were repeated at least three times.

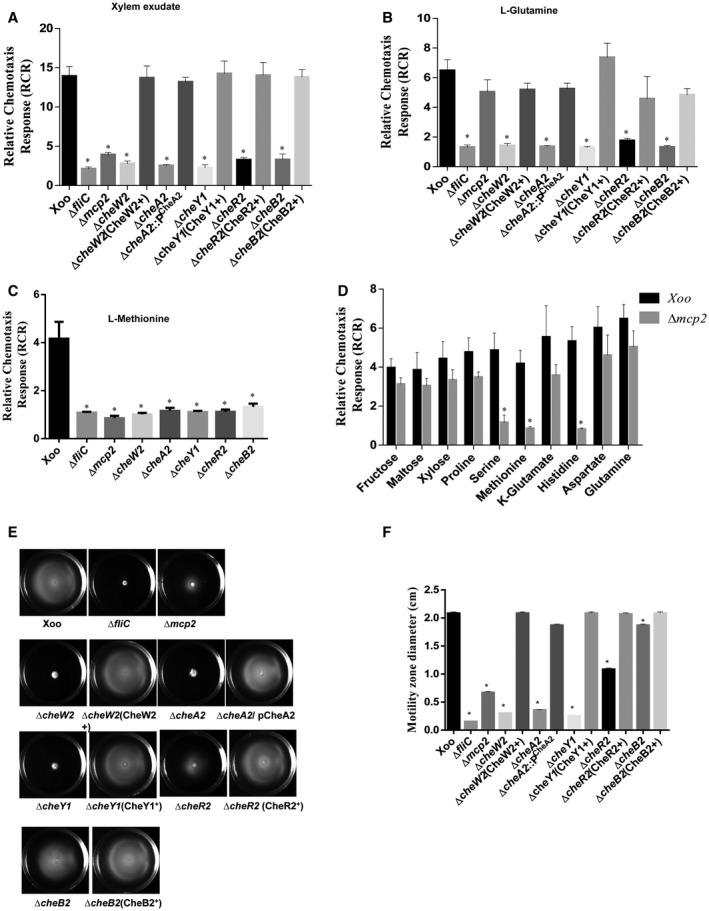

The core chemotaxis system of Xoo consists of CheW2, CheA2, CheY1, CheR2 and CheB2

To dissect the core chemotaxis system of Xoo, we constructed site‐directed, marker‐free, in‐frame deletion mutants of all individual che gene paralogues and performed both qualitative and quantitative chemotaxis response assays (Fig. 2, S1 and S3, see Supporting Information; Table S1). The Xoo ∆cheA2, ∆cheW2, ∆cheY1, ∆cheR2 and ∆cheB2 strains were completely non‐chemotactic in quantitative syringe capillary assays towards xylem sap, glutamine, methionine and xylose, similar to the ΔfliC mutant (Fig. 3A–C and S2, see Supporting Information). A mutant in the Xoo chemoreceptor (XOO2848), ∆ mcp2, exhibited a significantly reduced chemotactic response to xylem sap, methionine, serine and histidine compared with the wild‐type strain, but was proficient in the chemotactic response towards glutamine and xylose (Fig. 3A–D). Deletion mutants in the other paralogues of the core chemosensory pathway (cheA, cheW, cheR and cheB) genes exhibited chemotactic responses similar to those of the wild‐type Xoo strain towards these compounds (Fig. S3A,B; Table S1). Furthermore, mutants in the chemotaxis auxiliary protein encoding genes, ∆ cheD, ∆ cheV, ∆ cheZ and ∆ pdeA, exhibited partially reduced chemotactic responses towards these compounds (Fig. S3A,B; Table S1). Complementation of the mutants by either chromosomal reconstitution with the wild‐type allele [∆cheW2(CheW2+), ∆cheY1(CheY1+), ∆cheR2(CheR2+), ∆cheB2(CheB2+) and Δmcp2(MCP2+)] or plasmid‐borne, wild‐type cheA2 allele [pHM1(∆cheA2/pCheA2)] restored the chemotactic ability similar to that of the wild‐type strain (Fig. 3A,B, S1 and S4, see Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

The Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) core chemotaxis components CheW2, CheA2, CheY1, CheR2 and CheB2 are required for the flagellar‐mediated chemotactic response. Quantitative chemotaxis capillary assay with different Xoo strains: Xoo (wild‐type), ΔfliC, Δmcp2, ΔcheW2, ΔcheA2, ΔcheY1, ΔcheB2, cheR2. Cells were incubated at 28 °C with capillaries containing 0.22‐µm filter‐sterilized rice xylem exudate (A), l‐glutamine (B), l‐methionine (C) and phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The relative chemotaxis response was determined as the number of migrated bacterial cells in the capillary containing xylem exudate, l‐glutamine or l‐methionine to the number of migrated bacterial cells in the capillary containing PBS. (D) Quantitative chemotaxis assay for the Δmcp2 mutant with different chemoattractants for which the Xoo wild‐type strain exhibited a strong chemotactic response. The relative chemotaxis response was determined as the number of migrated bacterial cells in the test capillary containing chemoattractant to the number of migrated bacterial cells in the capillary containing PBS. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). (E) Swim plate motility assay for different Xoo strains: Xoo (wild‐type), ΔfliC, Δmcp2, ΔcheW2, ΔcheA2, ΔcheY1, ΔcheB2, cheR2 and mutants harbouring the reconstructed wild‐type allele on the chromosome. (F) Motility zone diameter quantification from semisolid swim plate motility assay. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 6). *Statistically significantly different values compared with the wild‐type strain (Student’s t‐test; P < 0.001). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Chemotaxis signalling controls flagella‐mediated motility by regulating the flagellar motor rotation frequency or direction (Wadhams and Armitage, 2004). Swimming motility assays on semisolid [0.1% agar containing peptone–sucrose (PS) medium] swim plates indicated that the ∆cheA2, ∆cheW2 and ∆cheY1 mutants exhibited greatly reduced motility, similar to that of the ∆fliC mutant (Fig. 3E,F; Table S1). The ∆ mcp2, ∆cheR2 and ∆cheB2 mutants exhibited partially reduced motility compared with the wild‐type Xoo strain (Fig. 3E,F; Table S1). Strains with mutation in other che paralogues and auxiliary chemotaxis components exhibited altered motility on semisolid swim plate assay (Fig. S3C,D; Table S1).

Taken together, these results suggest that CheW2, CheA2, CheY1, CheR2 and CheB2 constitute the core components of the Xoo chemotactic signal transduction system.

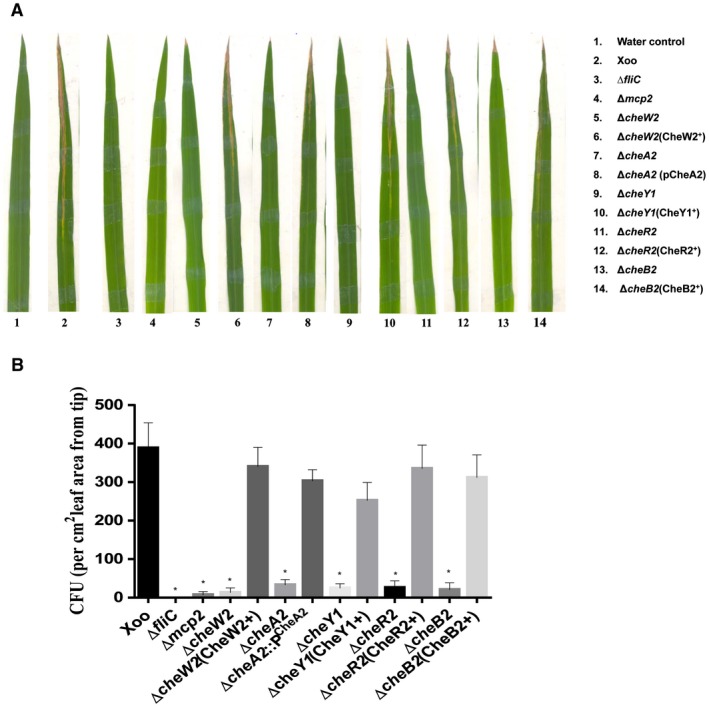

The Xoo chemotaxis system is essential for epiphytic infection and entry into rice leaves

In an attempt to understand the role of chemotaxis in a natural mode of infection, we performed the epiphytic (surface inoculation) mode of infection. In this mode of infection, the bacterial cells are deposited on the rice leaf surface without wounding, and the pathogen gains entry into the leaves through hydathodes, small openings at the tip and margin of the leaf (Mew et al., 1984; Pradhan et al., 2012; Ray et al., 2002). In this mode of infection, progression of lesions takes place from the tip to the base (Fig. 4A). Infection efficiency was determined by scoring the percentage of infected leaves exhibiting disease lesions (browning of the leaf) at 21 days post‐inoculation. Under these conditions, chemotaxis mutants, as well as the ΔfliC (non‐motile flagella‐deficient) mutant, exhibited significantly reduced virulence and infection efficiency (Table S3, see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

The Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) chemotaxis system is required for the epiphytic (surface) mode of infection and entry into rice leaves. (A) Representative photograph of typical symptoms of bacterial leaf blight (BLB) in the epiphytic mode of infection by different strains of Xoo: Xoo (wild‐type), ΔfliC, Δmcp2, ΔcheW2, ΔcheA2, ΔcheY1, ΔcheB2, cheR2. The fresh, healthy rice leaves with intact tips of 30‐day‐old susceptible rice plants (TN‐1) were either dipped in water (control) alone or in bacterial suspension. Lesion lengths and percentage efficiency of infection were measured at 21 days post‐inoculation. (B) Leaf entry assay by epiphytic mode of infection. Inoculations were performed by dipping 12–15‐day‐old leaves of rice seedlings in bacterial cultures for 1 min. Leaves were then washed and surface sterilized to remove bacteria attached to the leaf surface, homogenized and dilution plated to determine the number of colony‐forming units (CFU) per cm2 of leaf area from the tip, representative of bacterial cells inside the leaf. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 5). *Statistically significantly different values compared with the wild‐type strain (Student’s t‐test; *P < 0.001). The experiment was repeated at least three times. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In order to determine whether the virulence deficiency exhibited by the che mutant in the epiphytic mode of infection is caused primarily by a defect in leaf entry, we determined the number of colony‐forming units (CFU) per cm2 inside the leaf tip area after surface sterilization (Fig. 4B; Pradhan et al., 2012). Briefly, similar to epiphytic inoculation, intact rice leaves were dipped in bacterial cultures for 1 min and then washed and surface sterilized to remove bacteria attached to the leaf surface, homogenized and dilution plated to determine CFU (representative of bacterial cells inside the leaves). The che mutants blocked in one of the core chemotaxis components, as well as the ΔfliC mutant, exhibited significant deficiency in leaf entry compared with the wild‐type strain (Fig. 4B).

Xoo chemotaxis components are required for maximum virulence

To understand the role of chemotaxis components in virulence, we performed infection assays by the leaf clipping (wound) inoculation method (Chatterjee and Sonti, 2002; Kauffman et al., 1973). In this method, bacteria are directly delivered into the wound site, bypassing the epiphytic mode of infection. Xoo causes BLB disease with symptoms of brown dried lesions on the leaf (Figs S5A and S6A, see Supporting Information). The chemotaxis mutants of Xoo exhibited reduced lesion size and migration inside the leaves compared with the wild‐type strain (Figs S5 and S6). Interestingly, in comparison with the wild‐type Xoo strain, the lesions caused by chemotaxis mutants were always smaller (Figs S5A and S6A). The Δmcp2 mutant exhibited a significant reduction in lesion length (similar to the water control) and migration inside the leaves compared with the wild‐type strain (Figs S4D–F and S5). Complementation of the ΔcheA2, ΔcheR2, ΔcheW2, ΔcheY1 mutants and the Δmcp2 mutant with the wild‐type allele restored virulence to that of the wild‐type strain (Figs S4D–F and S5).

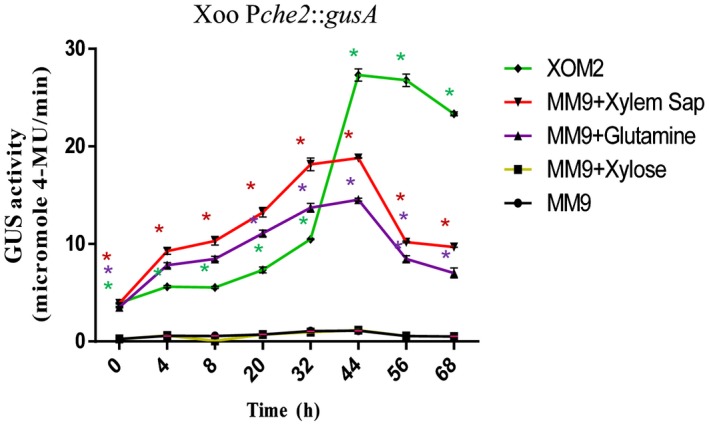

Expression of Xoo chemotaxis clusters (che2) and the fliC operon in the presence of xylem sap and plant‐mimicking XOM2 medium

In an attempt to understand the role of chemotaxis‐mediated flagellar motility in the entry, colonization and virulence at the leaf surface, we performed expression analysis of chemotaxis genes using chromosomal gusA reporter gene fusions in the wild‐type Xoo (Pche2::gusA; Pche3::gusA; Pche4::gusA; PfliC::gusA) grown in MM9 (minimal medium; Kelemu and Leach, 1990), MM9 + glutamine, MM9 + xylose, MM9 + xylem sap and XOM2 medium (plant growth‐mimicking medium; Tsuge et al., 2002) (Fig. 5, S7 and S8, see Supporting Information). β‐Glucuronidase (GUS) reporter assays revealed that the expression of the che2 cluster was induced in the wild‐type Xoo strain grown in both XOM2 medium and MM9 medium supplemented with either xylem sap or glutamine (a constituent of xylem sap) (Fig. 5). In contrast, the Pche2::gusA transcriptional reporter fusion exhibited a low basal level of expression in MM9 medium alone (Fig. 5). The Pche3::gusA, Pche4::gusA and PfliC::gusA reporter fusions exhibited significantly higher expression in XOM2 medium compared with MM9 minimal medium or rich PS medium (Figs S7 and S8). Taken together, the data suggest that the Xoo chemotaxis system is induced under the conditions expected in plants.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional analysis of the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) che2 chemotaxis cluster. Expression analysis was performed with the Xoo wild‐type strain harbouring the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) chromosomal reporter fusion (Pche2::gusA) grown in MM9, XOM2, MM9 + xylem sap and MM9 + glutamine by monitoring GUS activity. GUS activity was measured at 365 nm/455 nm excitation/emission wavelength, respectively, and represented as the number of cell‐normalized nanomoles of 4‐methylumbelliferone (4‐MU) produced per minute. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of the mean (n = 3). *P < 0.001 in Student’s t‐test: significant difference between the data obtained for MM9 medium supplemented with either glutamine or xylem sap and XOM2 medium compared with those obtained from MM9 medium growth conditions. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

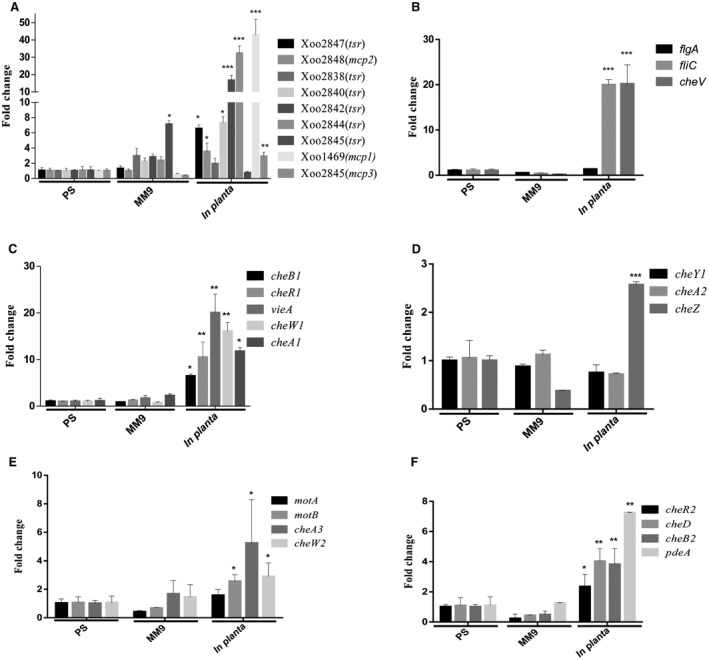

Xoo chemoreceptors, chemotaxis and motility genes are induced in planta

Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) analysis of chemoreceptors, chemotaxis and motility encoding genes of Xoo was performed with RNA isolated from bacterial cells harvested from infected leaves (Pradhan et al., 2012; see Experimental procedures), as well as from Xoo cells grown in either rich (PS) or minimal (MM9) medium, to determine whether the chemotaxis functions are induced in planta. Gene expression analysis revealed that genes encoding proteins of several chemoreceptors [Xoo1469 (Mcp1), Xoo2840 (tsr), Xoo2842 (tsr), Xoo2844 (tsr)], chemotaxis and motility [che1, che2, che3, che4 cluster proteins, FlgA, FliC and CheV] of Xoo were significantly induced in planta compared with PS (rich medium) or MM9 (minimal medium) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) chemotaxis and motility genes exhibit induced expression in planta. Relative quantification of expression of Xoo chemotaxis and motility cluster genes by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR). RNA was isolated from wild‐type Xoo cells harvested from infected leaves, as well as from Xoo cells grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.2 in either rich (PS) or minimal (MM9) medium. The amount of RNA relative to that in wild‐type cells grown in PS medium is equal to 1.0 and is normalized for 16S ribosomal RNA, used as an endogenous control to normalize the RNA for cellular abundance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 in Student’s t‐test. Standard errors were calculated based on at least three independent experiments (A‐F) Real time expression analysis of genes involved in chemotaxis and motility functions‐(A) chemotaxis receptors; (B) motility; (C‐F) chemotaxis core and auxiliary components .

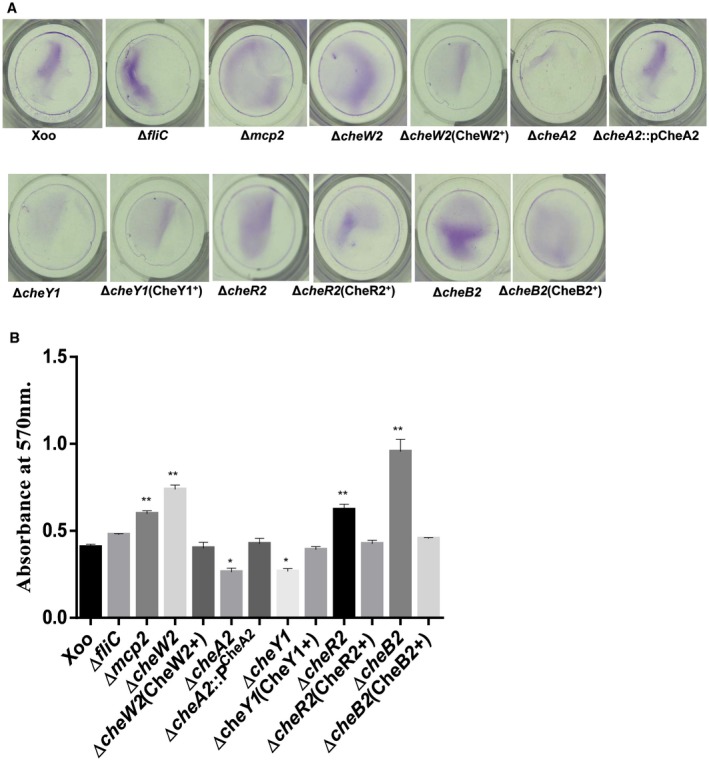

Chemotaxis mutants of Xoo exhibit altered attachment and biofilm formation

As several virulence‐associated functions, such as biofilm formation, iron metabolism, Type II and Type III secretion systems and their effectors, play a role in the virulence of Xoo in rice, we investigated whether the virulence deficiency exhibited by the chemotaxis deficient mutants is a result of these phenotypes.

It has been reported that the chemotactic signal transduction system plays a role in the regulation of biofilm formation in bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Hickman et al., 2005; Matilla and Krell, 2017; Merritt et al., 2007). In Xanthomonas, it has been shown that biofilm formation plays an important role in virulence and colonization (Pandey et al., 2016; Pradhan et al., 2012; Rai et al., 2012).

We performed the quantification of attachment and biofilm formation in 24‐well polystyrene sterile culture plates. Quantification of biofilm formation indicated that the ∆mcp2, ∆cheW2, ∆cheW3, ∆cheA3, ∆cheY2, ∆vieA, ∆cheR2, ∆cheR3, ∆cheB2, ∆cheD and ∆cheV mutants exhibited enhanced biofilm formation/attachment compared with the wild‐type Xoo strain. In contrast, the ∆cheW1, ∆cheA2, ∆cheY1, ∆cheZ and ∆pdeA strains exhibited slightly reduced biofilm formation/attachment compared with the wild‐type strain (Fig. 7 and S9, see Supporting Information).

Figure 7.

Mutants of the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) chemotaxis component exhibit altered biofilm formation. (A) Biofilm formation by different Xoo strains in the static biofilm after 48 h of growth and staining with 0.1% crystal violet. (B) Quantification of attached cells of different Xoo strains in the static biofilm after 48 h of growth. Attached cells were stained with crystal violet, dissolved in ethanol and quantified by measurement of the absorbance at 570 nm. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). *,**Statistically significantly different values compared with the wild‐type strain (Student’s t‐test; *P < 0.001, **P < 0.01). The experiment was repeated three times. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

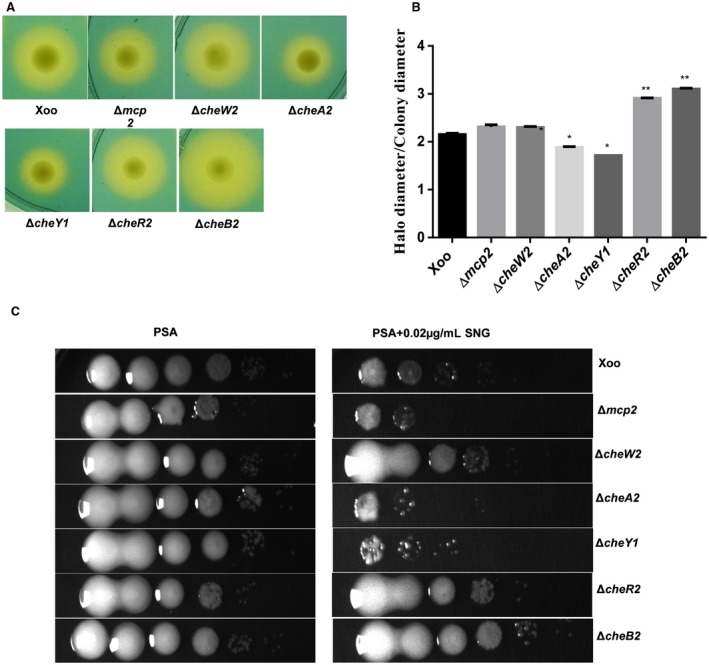

Chemotaxis mutants of Xoo exhibit altered siderophore production and intracellular free iron levels

To investigate whether the Xoo chemotaxis mutants are altered in iron homeostasis, we performed siderophore production assays (an indicator of iron starvation; Chatterjee and Sonti, 2002) on peptone–sucrose agar–chrome azurol sulphonate (PSA‐CAS) plates containing 2,2′‐dipyridyl (DP), a specific iron chelator. The ∆cheW2, ∆cheW3, ∆cheA3, ∆cheY2, ∆vieA, ∆cheR1, ∆cheR2, ∆cheB2, ∆cheD and ∆cheZ mutants significantly overproduced siderophore compared with the parental wild‐type strain (8A,B and S10A,B, see Supporting Information). In contrast, the ∆cheW1, ∆cheA2 and ∆cheY1 mutants exhibited reduced siderophore production compared with the wild‐type strain (8 and S10). We next performed streptonigrin (SNG) sensitivity assays, which depends on the intracellular iron levels, to assess the intracellular iron content in different strains of Xoo. SNG acts as a bactericide by promoting the formation of oxygen radicals, and its bactericidal activity is directly correlated with the intracellular iron content (Hassett et al., 1987; Schmitt, 1997). The ∆mcp2, ∆cheW1, ∆cheV, ∆cheA1, ∆cheA2, ∆cheZ, ∆cheY1, ∆cheY2, ∆vieA, ∆pdeA, ∆cheR3 and ∆cheB1 mutants were hypersensitive to SNG compared with the wild‐type Xoo strain. In contrast, the ∆cheD, ∆cheW2, ∆cheW3, ∆cheA3, ∆cheR1, ∆cheR2 and ∆cheB2 strains were less sensitive, indicative of low intracellular iron levels, compared with the wild‐type Xoo strain (8C and S10C).

Figure 8.

Mutants of the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) chemotaxis component exhibit altered siderophore production and sensitivity to streptonigrin (SNG). (A) Representative photographs of siderophore production assay by different strains of Xoo. Siderophore production is indicated by the presence of an extended halo around the colony grown on peptone–sucrose agar (PSA) plates containing chrome azurol sulphonate (CAS) + 50 µm 2,2′‐dipyridyl (PSA‐CAS + DP). (B) Quantification of siderophore production. The average ratio of siderophore halo to colony diameter for different strains of Xoo grown on PSA‐CAS‐DP plates. (C) SNG sensitivity plate assay. Different strains of Xoo were grown in peptone–sucrose (PS) medium at a density of 1 × 109 cells/mL. Cultures (4 μL) from each serial dilution were spotted onto PSA plates containing 0.02 μg/mL SNG. Plates were incubated for 72 h at 28 °C to observe bacterial growth. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). *,**Statistically significantly different values compared with the wild‐type strain (Student’s t‐test; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001). The experiments were repeated at least three times. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

In many bacteria, chemotaxis plays an important role in the adaptation to changing environmental conditions by the modulation of directional motility. Several plant‐ and animal‐pathogenic bacteria possess complex chemosensory signal transduction systems, wherein the interplay of multiple chemotaxis pathways has been proposed to be involved in the regulation of chemotaxis‐driven motility, together with other cellular functions.

Xanthomonas spp. possess a complex chemosensory system having several paralogues of the core and auxiliary chemotaxis components (Fig. 1; Table S1). Although chemotaxis has been proposed to play a role in the plant entry and colonization of xanthomonads, the exact role of chemotaxis in the epiphytic and pathogenic lifestyle is largely unknown.

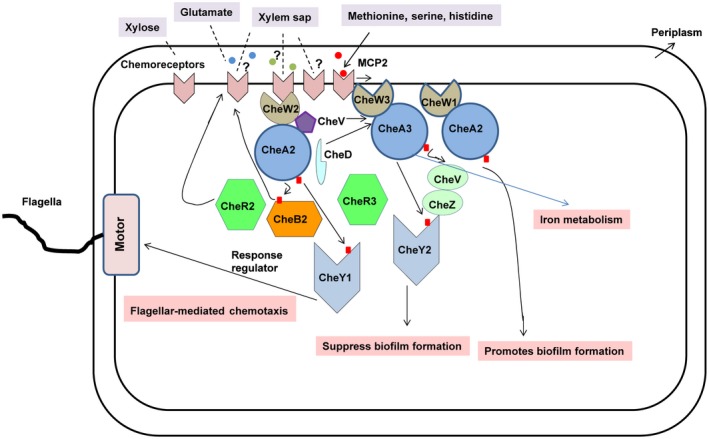

In this study, we show that CheA2, CheR2, CheW2 and CheYI constitute the core elements of the chemotaxis signal transduction system in Xoo. Xoo exhibits a chemotactic response towards xylem sap and components of xylem exudate, including several amino acids, sugars and organic acids, such as methionine, glutamine and xylose (Fig. 2; Bailey and Leegood, 2016; Feng and Kuo, 1975; Rai et al., 2012). We show that paralogues of the core chemotaxis components and auxiliary chemotaxis system also contribute to entry, colonization and virulence, and are involved in a complex interplay for the coordinated regulation of motility and virulence‐associated functions, including biofilm formation and iron metabolism (Fig. 9). In addition, we show that the chemoreceptor mcp2 is involved in Xoo sensing of both xylem sap and its constituents (serine, methionine and histidine), and is also required for entry into rice, and virulence (Figs 3, 4 and S4).

Figure 9.

A proposed model for the role of chemotaxis in the regulation of the virulence‐associated functions of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). Xoo encodes several paralogues of the core chemotaxis and auxiliary systems. The core chemotaxis signal transduction system (CheW2, CheA2, CheR2 and CheY1) is involved in the sensing of xylem sap constituents and the regulation of directional motility. The interplay of several paralogues of the chemotaxis system contributes to the coordinated regulation of motility, biofilm formation and iron metabolism. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Interestingly, although the mcp2 mutant of Xoo exhibits a reduced chemotactic response towards methionine, serine and histidine, it is proficient towards glutamine, xylose and other constituents of xylem sap (Fig. 3A–D). Xoo encodes at least 11 putative chemotaxis receptors, all of which are largely uncharacterized, particularly with regard to their role in chemoeffector (ligand) recognition. In general, the ligands specific for given chemoreceptors in bacteria are largely unknown (Kirby, 2009; Matilla and Krell, 2017). It has been proposed that diversity in the ligand‐binding domains (LBDs) of chemoreceptors and the lack of consensus, particularly in the LBD of closely related homologous chemoreceptors, may be one of the reasons for the difficulty in the functional interpretation of diverse cognate ligand (chemoeffector)‐chemoreceptor(s) found in closely related bacterial species (Matilla and Krell, 2017). It is possible that other chemotactic sensory receptors in Xoo may also be involved in the sensing of different constituents of xylem sap and/or other yet to be identified environmental signals.

Expression analysis using chromosomal reporter gus fusions and real‐time qRT‐PCR analysis indicates that Xoo chemotaxis and motility components are all induced in planta (Figs 5 and 6). In a recent study of protein expression in Xanthomonas citri (a pathogen of citrus) grown in vitro and inside the host plant citrus, many components of the chemotaxis system, including chemoreceptors and flagellar‐mediated motility, are induced in planta compared with in vitro conditions (Moreira et al., 2015). It seems likely that the transcriptional response of chemotaxis and motility components in Xanthomonas–plant interactions is an adaptive strategy for the bacterium to maximize its fitness in the host plant.

Deletion mutants in the paralogues of the core chemotaxis components cheA2, cheW2 and cheY1 exhibit a significant defect in flagellar‐mediated motility and chemotactic response towards xylem sap and constituents, similar to a non‐motile ΔfliC (flagella) mutant (Fig. 3; Table S1). However, the cheR2 and cheB2 mutants exhibit partially reduced motility, but are severely deficient in chemotactic responses to xylem sap and its constituents, and are also deficient in entry via the epiphytic mode of infection (Figs 3 and 4). These results indicate that directional motility mediated by the chemotaxis response contributes to Xoo entry inside rice leaves. Apart from the core chemotaxis components (cheA2, cheW2, cheY1, cheR2 and cheB2), other paralogues of the core chemotaxis signal transduction system and genes encoding proteins involved in the auxiliary chemotaxis system (cheD, cheV and cheZ) also exhibit altered motility and chemotactic response (Fig. S3). This indicates that, in Xoo, a complex interplay of several chemotaxis components plays a role in chemotaxis signal transduction system function. It is pertinent to note that, some bacteria, such as Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, possess multiple chemotaxis pathways. Pseudomonas aeruginosa has four chemosensory pathways, which are involved in diverse functions, such as chemotaxis‐driven motility, virulence, cyclic nucleotide turnover and regulation of type IV pili‐driven movement (Guvener et al., 2006; Hickman et al., 2005; Kirby, 2009).

Although mutants in the chemotaxis system of Xoo exhibit significant virulence deficiency in the epiphytic mode of infection (Fig. 4), these mutants also exhibit reduced virulence and migration when delivered to the wound site (Figs S5 and S6). This result suggests that, in Xoo, apart from the contribution of the chemotaxis signal transduction system to the directional motility for entry by the natural mode of infection, the chemotaxis‐mediated signal transduction system may also be involved in the regulation or modulation of other virulence‐associated functions. The assay of biofilm formation, siderophore production and intracellular iron levels shows that the chemotaxis mutants of Xoo are altered in these important virulence‐associated functions (Figs 7 and 8). It is pertinent to note that, in Ralstonia solanacearum and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato, it has been shown that the mutants defective in the chemotaxis system exhibit reduced virulence when inoculated by the natural mode of infection (spray or dip inoculation), but are virulence proficient when inoculated directly by wound infection (Clarke et al., 2016; Tans‐Kersten et al., 2001; Yao and Allen, 2006). In contrast, it has been shown that Dickeya dadantii chemotaxis mutants exhibit defects in entry into plants, as well as reduced virulence, even after wound inoculation (Antunez‐Lamas et al., 2009b, 2009a,2009b, 2009a).

In Xoo, the mutants in mcp2 and paralogues of the core chemotaxis components (cheA3, cheW3, cheY2 and cheR3) and chemotaxis auxiliary genes (cheD, cheV) exhibit enhanced biofilm formation compared with the wild‐type strain (Fig. 7 and S9). This indicates that the Xoo chemotaxis system suppresses biofilm formation. In Xanthomonas and the closely related Xylella fastidiosa, it has been shown that mutants in the motility and attachment functions exhibit opposite effects on movement and biofilm formation, and it has been proposed that these processes may oppose each other (Chatterjee et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2010 Rai et al., 2012). It is likely that the reduced motility exhibited by the mutants of the Xoo chemotaxis component may contribute to the hyper‐biofilm formation phenotype. In contrast with the enhanced biofilm formation phenotype exhibited by cheA3, cheW3, cheY2 and cheR3, cheW1, cheA2, cheY1 and cheZ exhibit reduced biofilm formation. This result indicates that the role of chemotaxis in biofilm formation in Xoo appears to be rather complex, as the interplay of multiple components of the chemotaxis signal transduction system may have a coordinated role in fine tuning both motility and attachment. It is also possible that the interplay of multiple chemotaxis pathways may be involved in an alternative mode of regulation of virulence and cell‐associated functions, such as biofilm formation and iron metabolism.

In several bacteria, it has been reported that, apart from motility, several other cell‐associated functions are also regulated by chemotaxis‐mediated signal transduction by affecting the alternative mode of regulation of gene expression (Kirby, 2009; Matilla and Krell, 2017; Szurmant and Ordal, 2004). For example, in Vibrio cholera, it has been shown that mutations in CheY proteins also affect the production of cholera toxin by altering its gene expression, in addition to its role in chemotaxis‐mediated motility (Bandyopadhaya and Chaudhuri, 2009; Lee et al., 2001). Different paralogues of the chemotaxis components are involved in the regulation of functions other than chemotaxis‐driven motility in the human pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi (Li et al., 2002; Motaleb et al., 2011). Some of the alternative modes of gene regulation by chemotaxis signal transduction systems that have been proposed include the presence of additional domains associated with the response regulator CheY, such as domains involved in the modulation of the secondary messenger cyclic di‐GMP (Hickman et al., 2005), and trans‐phosphorylation of multiple CheY‐like proteins by the chemotaxis sensor kinase CheA, leading to alteration in the signal transduction flow and interference in other two‐component regulators (Jimenez‐Pearson et al., 2005; Sourjik and Schmitt, 1998; Szurmant and Ordal, 2004; Wuichet and Zhulin, 2010). As Xoo chemotaxis mutants exhibit altered motility, biofilm formation and iron metabolism, we performed expression analysis of virulence‐associated functions of Xoo by real‐time qRT‐PCR from RNA isolated from different strains of Xoo: wild‐type (Xoo), ΔcheY1 and ΔcheY1(CheY1+) (ΔcheY1 mutant harbouring the chromosomal reconstituted wild‐type allele). Expression analysis indicated that the ΔcheY1 mutant exhibits reduced expression of virulence functions [such as motility (fliC; XOO2581), rpoN; adhesins for attachment atsE (XOO0041), xadA (XOO0842); iron uptake fyuA (XOO0897, a putative ferric uptake receptor); siderophore uptake (xsuA; XOO1359)] compared with the wild‐type Xoo strain (Fig. S11, see Supporting Information). This indicates that, in Xoo, in addition to chemotaxis‐driven motility, the chemotaxis signal transduction system is involved in the regulation of virulence and cell‐associated functions, such as biofilm formation and iron metabolism.

Iron homeostasis, which includes iron uptake, metabolism and storage, plays an important role in the virulence of several animal and plant pathogens (Andrews et al., 2003; Cassat and Skaar, 2013; Expert et al., 2012). In Xanthomonas, it has been shown that iron metabolism and regulation play a crucial role in virulence (Javvadi et al., 2018; Pandey and Sonti, 2010; Pandey et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b; Rai et al., 2015). Xanthomonads produce xanthoferrin, an α‐hydroxycarboxylate‐type siderophore, under iron starvation conditions, which is required for the uptake of the ferric form of iron (Chatterjee et al., 2002; Pandey and Sonti, 2010; Pandey et al., 2017a; Rai et al., 2015). Mutants of the Xoo chemotaxis component exhibit altered siderophore production and sensitivity to SNG (Figs 8 and S10). The Xoo chemotaxis signal transduction system is thus also involved in the modulation of iron metabolism. It is pertinent to note that, in Helicobacter pylori, the chemoreceptor TlpD is also involved in the modulation of expression of genes for iron nutrition. TlpD interacts with both CheA and enzymes such as aconitase and catalase, involved in iron metabolism and oxidative stress. Interestingly, a TlpD mutant exhibited increased sensitivity to iron limitation and oxidative stress (Behrens et al., 2016). It is possible that the Xoo chemotaxis components are also involved in the interaction with the components of iron uptake/metabolism, thus modulating iron homeostasis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the chemotaxis study are listed in Table S2. Xoo and Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 8004 strains were grown at 28 ºC and 200 rpm (New Brunswick Scientific, Innova 43, Edison, NJ, USA) in PS and nutrient broth medium (Tsuchia et al., 1982). Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37 ºC and 200 rpm in Luria–Bertani medium (Miller, 1992). The growth of Xoo strains in modified minimal medium (MM9) and plant growth‐mimicking medium (XOM2) was performed as described previously (Kelemu and Leach, 1990; Tsuge et al., 2002). The concentrations of antibiotics used were as follows: rifampicin (Rif; 50 μg/mL); spectinomycin (Spec; 50 μg/mL); kanamycin (Kan; 50 μg/mL); ampicillin (Amp; 100 μg/mL); gentamycin (Gent; 5 μg/mL); nalidixic acid (Nal; 50 μg/mL); 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐d‐galactoside (X‐Gal; 25 μg/mL). For iron starvation conditions, DP (Fluka Analytical, Steinheim, Westphalia, Germany) was used as an Fe2+ chelator in PS medium.

Molecular biology and microbiology techniques

Standard genetics and molecular techniques were used for genomic DNA isolation, plasmid isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, ligation, transformation and agarose gel electrophoresis, as described previously (Sambrook et al., 1989). High‐fidelity Phusion taq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), Taq DNA polymerase and restriction and ligation enzyme (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA transformations were performed by either heat shock or electroporation. The oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table S4 (see Supporting Information).

Construction of marker‐free deletion mutants of Xoo

The mcp and che genes in Xoo were deleted using a marker‐free deletion technique employing the pK18mobSacB system, which uses a suicidal vector harbouring the kanamycin gene (kan) and SacB gene as selection and counter‐selection markers, respectively (Schäfer et al., 1994). Briefly, the 5′ and 3′ flanking ends of the target gene were PCR amplified, digested with a common inward restriction enzyme and ligated. The ligated fragment was cloned into the backbone of the pK18mobSacB plasmid after restriction digestion with the appropriate enzymes to make a deletion construct. The resulting constructs (listed in Table S2) were introduced into the Xoo wild‐type strain by electroporation. Single recombinants which were sucrose sensitive and kanamycin resistant were obtained in selection plates containing kanamycin. To obtain in‐frame deletion, single recombinants (Kanr, Sucs) were grown in nutrient broth for three passages and then dilution plated to select for sucrose‐resistant and kanamycin‐sensitive colonies. The double recombinants were then screened by PCR to confirm the deletion and further verified by sequencing. The primers used for the construction of the deletion strains are listed in Table S4.

Chromosomal reconstitution and construction of plasmids for complementation analysis

Complementation was performed by reconstituting the full‐length gene into the genomic background of the marker‐free deletion mutant using the pK18mobSacB system. The full‐length gene was amplified using 5′ and 3′ flanking deletion primers (Table S4), and cloned into the pK18mobSacB vector. The pK18mobSacB vector harbouring the full‐length genes was introduced into the respective deletion mutant background and selected for sucrose sensitivity and kanamycin resistance to obtain single recombinants. The single recombinants were grown in nutrient broth and screened for sucrose‐resistant and kanamycin‐sensitive double recombinants. The double recombinants were further screened by PCR and sequencing to confirm reconstitution of the wild‐type allele and further confirmed by complementation of the phenotypes. The cheA complementation was performed by introducing the pHM1 expression vector harbouring full‐length cheA under the lacz promoter.

Construction of promoter fusions with the GUS reporter

A suicidal vector pVO155 containing the promoter‐less gusA gene was used to construct GUS reporter fusions, as described previously (Oke and Long, 1999; Pandey et al., 2016). Briefly, the respective putative promoter sequences of che2, che3, che4 and fliC gene clusters were amplified by the primers listed in Table S4 and cloned into pVO155, upstream of the gusA reporter gene. Subsequently, the resulting constructs (Table S2) were introduced into the Xoo wild‐type strain by electroporation to obtain chromosomal reporter fusions. Insertion of the GUS reporter cassette was confirmed by PCR and sequencing using gusA‐specific and plasmid flanking primers.

Motility assays

Swim plate assay was performed as described previously (Rai et al., 2012). Briefly, Xoo strains were grown in PS medium supplemented with the required antibiotics until the early stationary phase, pelleted down at 4000 rpm (Sorvall RC‐5B, Dupont, New Mexico, USA) for 10 min, washed twice and resuspended in sterile PBS. Four microlitres of bacterial suspension were inoculated at the centre of swim plates (0.1% agar containing PS medium) and incubated at 28 ºC. The motility was quantified by measuring the diameter of the swimming motility zone after 40 h.

Collection of xylem sap (guttation fluid)

The collection of xylem sap was carried out as described previously (Ray et al., 2002; Yamaji et al., 2008) with some modifications. Guttation is most noticeable when transpiration is suppressed, and root pressure and relative humidity are high. Four‐week‐old seedlings of the susceptible rice variety ‘Taichung Native‐1’ (TN‐1) were maintained under highly humid conditions in specially built chambers kept in the glasshouse. Xylem sap was collected from the leaf tips and margins early in the morning with the help of a micropipette. The first few droplets were discarded to avoid contamination, and filter sterilized at 0.22 µm (Millex‐GS, Mumbai, India). The collected leaf guttation fluid (xylem sap) was immediately kept at –80 ºC for further use.

Chemotaxis assay by the capillary method

For the chemotaxis assay, the syringe capillary method was carried out as described previously with certain modifications (Mazumder et al., 1999; Pandey et al., 2016). Briefly, Xoo strains were grown in PS medium supplemented with the required antibiotics to OD600 = 1. The cells were pelleted at 4000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R, New Delhi, India) for 10 min, washed twice and resuspended in sterile PBS. Capillary tubes (0.45 mm × 13 mm; single‐use syringe 1 mL, Dispo Van, Faridabad, Haryana, India) containing various 0.22‐µm (Millex‐GS) filter‐sterilized monosaccharides (1.8 mg/mL), amino acids [10 mg/mL except aspartate (5 mg/mL)], organic acids (1 mg/mL), PBS or xylem sap (guttation fluid) were incubated with cell suspension (in 0.5‐mL Eppendorf tubes) of Xoo strains at 28 ºC for 4 h. To determine the CFU of bacteria in the capillary, the content of the capillary was serially dilution plated on PSA. RCR was quantified as the number of migrated bacterial cells in the syringe capillary containing the test chemoattractant to the number of migrated bacterial cells in the syringe capillary containing PBS to rule out cells migrated either as a result of bacterial random motility or diffusion.

Chemotaxis in the soft agar plate assay was performed as described previously (Yao and Allen, 2006) with slight modifications. Bacterial suspension was prepared in a similar manner to the capillary method mentioned above. Five microlitres of cell suspension were inoculated on plates and incubated at 28 ºC for 5–6 days. The RCR was measured as (MM9 + xylem exudate plate) zone diameter to (MM9 plate) zone diameter.

Virulence assays

Virulence assay was performed by wound and surface inoculation methods. Wound inoculation was performed by the leaf clipping method (Kauffman et al., 1973). Xoo strains were grown in PS medium supplemented with the required antibiotics to OD600 = 1. Cells were pelleted down at 6000 rpm for 10 min, washed and resuspended in sterile PBS to a density of 109 cells/mL. Sterile surgical scissors dipped in these culture suspensions were used to clip the healthy leaf tips of 40–45‐day‐old leaves of susceptible variety TN‐1 plants. At 2 weeks post‐inoculation, the lesion was quantified by measuring the lesion length. For each strain, at least 20 leaves were inoculated per experiment and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Assays for epiphytic infection by surface inoculation were performed as described previously (Pradhan et al., 2012; Ray et al., 2002). Xoo strains were grown in PS medium supplemented with the required antibiotics until early stationary phase, pelleted down at 6000 rpm for 10 min, washed and resuspended in sterile PBS (10 mL) to a density of 3 × 109 cells/mL. Healthy leaves, about 25–30 days old, of susceptible variety TN‐1 plants were dipped into these bacterial suspensions up to a distance of 2–3 cm for 1 min. Plants were maintained under conditions of high humidity in specially built chambers for 24 h before inoculation. After 21 days, the total number of leaves exhibiting disease lesions was counted and the percentage of infection was calculated against the total number of leaves inoculated.

For leaf entry assay, surface inoculation was performed as described above for epiphytic inoculation with healthy tillering stage leaves (Pradhan et al., 2012). After 2 h of incubation at 28 ºC, a 1‐cm2 area from the leaf tip was surface sterilized and homogenized, and CFU was determined by serial dilution plating. Entry efficiency was measured in terms of CFU/cm2 of leaf area from the tip. For each strain, five leaves were inoculated per experiment and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Migration of Xoo inside the leaves

Wound inoculation was carried out as described previously. The migration assay was performed as described previously with certain modifications (Chatterjee and Sonti, 2002). At 5 days post‐inoculation, the leaves were detached from the plant and surface sterilized in 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Mumbai, India). The leaves were then washed three times in 70% ethanol (Commercial Alcohols, Brampton, ON, Canada) and sterile double‐distilled water (DDW), cut into approximately 1‐cm pieces (along the width) from the bottom of the leaf to the top (site of inoculation) by sterile surgical scissors and incubated on PSA medium supplemented with antibiotics (rifampicin, cycloheximide and cephalexin) at 28 °C. Migration was estimated by observing the colonies formed after 3–5 days by the bacterial ooze from the cut ends of the leaves.

GUS reporter assays

To investigate the role of the chemotaxis system of Xoo in rice leaf blight disease development, we performed expression analysis assays as described previously (Pandey et al., 2016, 2017a) with some modifications. Briefly, for in vitro expression analysis, Xoo strains harbouring the chromosomal transcriptional fusions with the GUS reporter were grown in PS medium supplemented with the required antibiotics until the early stationary phase, pelleted down at 4000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R) for 10 min and washed twice with sterile PBS. Then, the pellets were resuspended in PS, XOM2, MM9 and MM9 together with sodium glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), xylem sap or d‐xylose, at the concentrations used in the capillary chemotaxis assay, and grown at 28 ºC and 200 rpm in a shaking incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, Innova 43). At regular time intervals, the absorbance was measured at 600 nm, the cells were harvested from 1 mL of culture, washed with sterile PBS, resuspended in 250 μL of 1 mm 4‐methylumbelliferyl‐β‐d‐glucuronide (MUG) extraction buffer [50 mm sodium dihydrogen phosphate (pH 7.0), 10 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% sodium lauryl sarcosine, 0.1% Triton X‐100 and 10 mm β‐mercaptoethanol] and incubated at 37 ºC for 30 min. Subsequently, reactions were terminated after the addition of 675 μL of stop solution (0.2 m Na2CO3) to 75 μL of reaction mixture, and fluorescence was measured with 4‐methylumbelliferone (4‐MU; Sigma, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) as the standard at excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 nm and 455 nm, respectively. Cell‐normalized GUS activity for GUS assays was expressed as micromoles of 4‐MU produced per minute per 1 × 109 cells.

Expression analysis by qRT‐PCR

For expression analysis by qRT PCR, the Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) method was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was isolated from cultures grown to mid‐exponential phase in PS, pelleted, washed with sterile PBS and exposed overnight to XOM2 and MM9 at 28 °C and 200 rpm (New Brunswick Scientific). Isolation of RNA from infected leaves (in planta) were performed as described previously (Pradhan et al., 2012). Briefly, leaves from rice plants infected with the wild‐type strain of Xoo (10 leaves) were cut 5 days after inoculation at the region in which the lesion ended, and the cut surface was placed in 1 mL of water in an Eppendorf tube for 1 h to allow the xylem sap and bacteria to flow into the water. The bacterial cells were pelleted in a microfuge tube, washed and processed for RNA isolation. The RNA was isolated by the Trizol (Invitrogen) method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real‐time RT‐PCR was performed as described previously (Pradhan et al., 2012). Real‐time qRT‐PCR was performed in a 7500 Real‐time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and analysed by SDS relative quantification software (Applied Biosystems) as described previously (Pandey et al., 2016). The primers used for real‐time qRT‐PCR are listed in Table S4.

SNG sensitivity assay

The SNG sensitivity assay was performed to determine intracellular iron levels, as SNG causes cell death by reacting with free ferrous iron to produce superoxide and hydroxyl free radicals (Hassett et al., 1987; Pandey et al., 2016; Schmitt, 1997). Xoo cultures were grown to mid‐exponential phase in PS, pelleted, washed with sterile PBS and normalized to an OD600 of 1.0. Cultures were serially diluted and then spotted on PSA containing 0.02 μg/mL of SNG (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Plates were then incubated at 28 °C for 72 h to observe growth inhibition.

CAS plate assays for siderophore production

Siderophore assay was performed on a CAS indicator plate as described previously (Chatterjee and Sonti, 2002; Schwyn and Neilands, 1987). In siderophore plate assay, freshly grown bacterial strains were spotted onto PSA plates containing DP, with CAS and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA) as indicators. CAS/HDTMA complexes with ferric ion to produce a blue colour. During growth, bacteria secrete siderophores, which chelate iron from the dye complex, turning orange around the colonies, and measured as the halo diameter to colony diameter ratio (Chatterjee and Sonti, 2002).

Biofilm assay

Biofilm assay was performed as described previously (Chatterjee et al., 2010; Pradhan et al., 2012; Rai et al., 2012). Xoo (wild‐type), che mutants and complementation strains were grown overnight in PS broth medium supplemented with the required antibiotics at 28 °C and 200 rpm, pelleted down at 6000 rpm for 10 min, washed and resuspended in sterile milli q (MQ). Approximately, 1 × 109 cells were transferred into 2 mL of fresh PS medium in 24‐well sterile polystyrene culture plates and incubated at 28 °C without shaking. After 48 h, the medium was decanted gently, the wells were washed with autoclaved water to remove loosely attached cells and adherence was monitored by 1% crystal violet staining. Excess stain was removed by washing the wells with DDW. The biofilm was quantified by dissolving the attached cells in 1 mL of 90% ethanol and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm.

In planta bacterial growth assay

For bacterial growth in the host, 30–35‐day‐old susceptible rice plant leaves were clip inoculated. Every alternate day post‐inoculation, a 1‐cm2 leaf area below the lesion point was cut and surface sterilized by sequential dipping in 1% (vol/vol) sodium hypochlorite (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 70% ethanol and washing three times in sterile water. Sterilized leaves were crushed using a mortar and pestle and serially dilution plated onto PS medium containing the required antibiotics. Cyclohexamide and cephalexin were added to reduce fungal and other bacterial contamination, respectively. Bacterial growth was measured in the form of CFU/cm2 leaf area.

Author contributions

R.K.V. performed all the experiments and analysed the data. B.S. generated the cheA complementation plasmid and the complemented strain. SC designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig S1 Qualitative chemotaxis swim plate assay response of different strains of Xoo. (A)Swim plate motility assay was performed on 0.1% agar minimal media (MM9) plates alone or MM9 containing 100 μl xylem sap. 5 μl of cell suspension of 1×109 was inoculated on plates and incubated at 28°C for 5‐6 days. (B) Raitio of motility zone diameter on MM9 plates containing xylem sap over MM9 plate only for each respective strain. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=6). *, ** statistically significant different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.01, **P<0.001,).The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Fig S2 Quantitative chemotaxis capillary assay in response to D‐(+)‐Xylose with different Xoo strains; ΔfliC, ΔcheW2, ΔcheA2, ΔcheY1, ΔcheB2, cheR2 and and mutants harbouring reconstructed wild type allele on the chromosome Cells were incubated at 28°C with capillaries containing D‐(+)‐Xylose and PBS. Relative chemotaxis response was determined by migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing Xylose over the migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing PBS. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=6). *, statistically significant different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; *P<0.001). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Fig S3 Chemotaxis response of Xoo mutants in the paralogs of the core chemotaxis and auxillary chemotaxis components. Quantitative chemotaxis capillary assay in response to xylem sap (A) and L‐glutamine (B) with different Xoo strains; Xoo (wild type), ΔfliC, ΔcheA1, ΔcheA3, ΔcheW1, ΔcheW3, ΔcheY2, ΔvieA , ΔcheB1, ΔcheR1 , ΔcheR3, ΔcheD, ΔcheV, ΔcheZ, ΔpdeA. Cells were incubated at 28°C with capillaries containing xylem sap, L‐glutamine and PBS. Relative chemotaxis response was determined by migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing chemoattractant over the migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing PBS. (C) Swim plate motility assay for different Xoo strains; Xoo (wild type), ΔfliC, ΔcheA1, ΔcheA3, ΔcheW1, ΔcheW3, ΔcheY2, ΔvieA , ΔcheB1, ΔcheR1 , ΔcheR3, ΔcheD, ΔcheV, ΔcheZ, ΔpdeA. (D) Motility zone diameter measured from semisolid swim plate motility assay. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=6). *, **,*** statistically significantly different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 ). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Fig S4 Role of Xoo mcp2 in chemotaxis, motility and virulence. (A) Quantitative chemotaxis capillary assay in response to L‐Histidine (10mg/ml) with different Xoo strains; Xoo wild type, Δmcp2, and Δmcp2 (Mcp2+) (mcp deletion mutant complemented with the chromosomally reconstituted wild type allele). Cells were incubated at 28°C with capillaries containing xylem sap, L‐glutamine and PBS. Relative chemotaxis response was determined by migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing chemoattractant over the migrated bacterial cells in capillary containing PBS. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=6). (B) Swim plate motility assay for different Xoo strains; Xoo (wild type), Δmcp2, and Δmcp2 (Mcp2+). (C) Motility zone diameter measured from semisolid swim plate motility assay. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=6). (D) Representative picture of typical symptom of BLB in wound infection by different strains of Xoo. (E) Quantification of lesion length at 15 days post inoculation. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=15). (F) In planta bacterial migration assay was performed on on leaves inoculated by leaf clip method 5‐day‐ post inoculation. Migration assay was performed by inoculating 1cm pieces of infected leave, cut from base to tip with sterile scissors on rich PS medium with respective antibiotics. Migration was estimated by observing colonies formed after 1 to 3 days by the bacterial ooze from the cut ends of rice leaf pieces. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=6). *, statistically significant different values compared to the value of Xoo wild‐type strain (student's t test; P<0.001). The experiments were repeated two times.

Fig S5 Role of Xoo chemotaxis components in virulence by wound inoculation. Virulence assays were conducted by inoculating 40‐ to 50‐day‐old rice plants of the susceptible `Taichung Native‐1' (Tn‐1) through wound inoculation . Rice leaves were cliped with sterile surgical scissors dipped in bacterial suspension of 1 × 109 cells/ml density. (A) Representative picture of typical symptom of BLB in wound infection by different strains of Xoo. (B) Quantification of lesion length at 15 days post inoculation. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=18). (C ) In planta bacterial migration assay was performed on on leaves inoculated by leaf clip method 5‐day‐ post inoculation. Migration assay was performed by inoculating 1cm pieces of infected leave, cut from base to tip with sterile scissors on rich PS medium with respective antibiotics. Migration was estimated by observing colonies formed after 1 to 3 days by the bacterial ooze from the cut ends of rice leaf pieces. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=18). *, **,*** statistically significantly different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 ). The experiment was repeated three times.

Fig S6 Virulence assay of different strains of Xoo by wound inoculation. Virulence assays were conducted by inoculating 40‐ to 50‐day‐old rice plants of the susceptible `Taichung Native‐1' (Tn‐1) through wound inoculation . Rice leaves were cliped with sterile surgical scissors dipped in bacterial suspension of 1 × 109 cells/ml density. (A) Representative picture of typical symptom of BLB in wound infection by different strains of Xoo. (B) Quantification of lesion length at 15 days post inoculation. Data are shown as mean± S.D. (n=18). (C ) In planta bacterial migration assay was performed on on leaves inoculated by leaf clip method 5‐day‐ post inoculation. Migration assay was performed by inoculating 1cm pieces of infected leave, cut from base to tip with sterile scissors on rich PS medium with respective antibiotics. Migration was estimated by observing colonies formed after 1 to 3 days by the bacterial ooze from the cut ends of rice leaf pieces. *, **,*** statistically significantly different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 ). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Fig S7 Transcriptional analysis of the Xoo chemotaxis clusters (che3, che4) and flagellar biosyntehsis cluster (fli). Expression analysis was carried out with the Xoo wild type stains harboring the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) chromosomal reporter fusion; Pche3::gusA, Pche4::gusA, PfliC::gusA grown under MM9, XOM2, MM9 + xylem sap, MM9 + glutamine conditions by monitoring the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) activity. β‐Glucuronidase (GUS) activity was measured at 365/ 455 nm excitation/emission wavelength respectively and represented as cell normalized nanomoles of 4‐methyl‐umbelliferone (4‐MU) produced per minute. Error bars represent SD of the mean (n = 3). *indicates P<0.001 in Student's t test, significant difference between the data obtained for the MM9 medium supplemented with xylem sap and XOM2 medium, compared to those obtained from the MM9 growth condition.

Fig S8 Transcriptional analysis of the Xoo chemotaxis clusters (che2, che3, che4) and functions involved in flagellar biogenesis in different growth medium. Expression analysis was carried out with the Xoo wild type stains harboring the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) chromosomal reporter fusion; (A) Pche2::gusA, (B) Pche3::gusA, (C) Pche4::gusA, (D) PfliC::gusA. Strains were grown under PS (rich medium), MM9, XOM2, MM9 + xylem sap, MM9 + glutamine conditions by monitoring the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) activity. β‐Glucuronidase (GUS) activity was measured at 365/ 455 nm excitation/emission wavelength respectively and represented as cell normalized nanomoles of 4‐‐‐umbelliferone (4‐MU) produced per minute. Error bars represent SD of the mean (n = 3). *indicates P<0.001 in Student's t test, significant difference in expression compared to the expression in rich PS medium.

Fig S9 Altered biofilm formation exhibited by mutants of the chemotaxis component of Xoo. (A) Biofilm formation by different Xoo strains in the static biofilm after 48 hrs of growth and staining with 0.1% Crystal Violet. (B) Quantification of attached cells of different Xoo strains in the static biofilm after 48‐hours of growth. Attached cells were stained with Crystal Violet (CV), dissolved in ethanol and quantified by measuring absorbance at 570 nm. Data are shown as mean ± S.D (n=3). *, ** statistically significantly different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.001, ** P<0.01 ). The experiment was repeated three times.

Fig S10 Siderophore production and sensitivity to streptonigrin OF Xoo chemotaxis component mutants. (A) Representative pictures of siderophore production assay by different strains of Xoo. Siderophore production is indicated by the presence of an extended halo around the colony grown on peptone‐sucrose agar plates containing chrome azurol sulphonate (CAS) + 50 μM 2,2' dipyridyl (PSA‐CAS +DP) (B) Quantification of siderophore production. Average ratio of siderophore halo to colony diameter for different strains of Xoo grown on PSA‐CAS‐DP plate. (C) Streptonigrin (SNG) sensitivity plate assay. Different strains of Xoo were grown in PS media at a density of 1×109 cells/ml. 4μL of cultures from each serial dilution was spotted on PSA plates containing 0.02μg/ml SNG. Plates were incubated for 72 h at 28°C to observe bacterial growth. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3). *, **, *** statistically significantly different values compared to the value of wild‐type strain (student's t test; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 ). The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Fig S11 Expression analysis of virulence associated functions by real‐time qRT‐PCR. Relative quantification of expression of the virulence associated functions; motility fliC (XOO2581) (A), rpoN (B); adhesins for attatchment atsE (XOO0041; host attachment protein) (C), xadA (XOO0842; adhesin) (D); iron uptake fyuA (XOO0897, a putative ferric uptake receptor) (E), siderophore uptake (xsuA; XOO1359) (F). RNA was isolated from different strains of Xoo; wild type (Xoo), ΔcheY1 and ΔcheY1(CheY1+) (ΔcheY1 mutant harbouring the chromosomal reconstituted wild type allele), grown to an optical density (OD600) of 1.2 in PS medium. Amount of RNA relative to that in the wild‐type cells is equal to 1.0 and is normalized for 16S ribosomal RNA, used as an endogenous control to normalize the RNA for cellular abundance. * P<0.001 in Student's t test. Standard errors were calculated based on at least three independent experiments.

Table S1 Components of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae chemotaxis system.

Table S2 Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Table S3 Mutants of chemotaxis component of Xoo exhibit virulence deficiency in epiphytic (surface inoculation) mode of infection.

Table S4 Oligonucleotides used in this study.

Acknowledgements

R.K.V. is the recipient of Junior and Senior Research Fellowships from the Department of Biotechnology, India, towards the pursuit of a PhD degree. This study was supported by funding to S.C. from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Department of Science and Technology‐SERB, Government of India and core funding from centre for dna fingerprinting and diagnostics, telengana, india (CDFD). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Altschul, S.F. , Madden, T.L. , Schaffer, A.A. , Zhang, J. , Zhang, Z. , Miller, W. , et al (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI‐BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodriguez‐Quiñones F. (2003) Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 215–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunez‐Lamas, M. , Cabrera, E. , Lopez‐Solanilla, E. , Solano, R. , Gonzalez‐Melendi, P. , Chico, J.M. , et al (2009b) Bacterial chemoattraction towards jasmonate plays a role in the entry of Dickeya dadantii through wounded tissues. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunez‐Lamas., M. , Cabrera‐Ordonez, E. , Lopez‐Solanilla, E. , Raposo, R. , Trelles‐Salazar, O. , Rodriguez‐Moreno, A. and Rodriguez‐Palenzuela, P. (2009a) Role of motility and chemotaxis in the pathogenesis of Dickeya dadantii 3937 (ex Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937). Microbiology, 155, 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K.J. and Leegood, R.C. (2016) Nitrogen recycling from the xylem in rice leaves: dependence upon metabolism and associated changes in xylem hydraulics. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2901–2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhaya, A. and Chaudhuri, K. (2009) Differential modulation of NFkappaB‐mediated pro‐inflammatory response in human intestinal epithelial cells by cheY homologues of Vibrio cholerae . Innate Immun. 15: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, W. , Schweinitzer, T. , McMurry, J.L. , Loewen, P.C. , Buettner, F.F. , Menz, S. , et al (2016) Localisation and protein‐protein interactions of the Helicobacter pylori taxis sensor TlpD and their connection to metabolic functions. Sci. Rep. 6, 23 582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bűttner, D. and Bonas, U. (2010) Regulation and secretion of Xanthomonas virulence factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassat, J.E. and Skaar, E.P. (2013) Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe, 13, 509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. , Almeida, R. P. P. and Lindow, S. E. (2008a) Living in two worlds: the plant and insect lifestyles of Xylella fastidiosa . Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 243–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. , Killiny, S. , Almeida, R.P.P. and Lindow, S.E. (2010) Role of cyclic di‐GMP in Xylella fastidiosa biofilm formation, plant virulence and insect transmission. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 23, 1356–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. and Sonti, R.V. (2002) rpfF mutants of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae are deficient for virulence and growth under low iron conditions. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 15, 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. , Wistrom, C. and Lindow, S.E. (2008b) A cell–cell signaling sensor is required for virulence and insect transmission of Xylella fastidiosa . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 2670–2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C.R. , Hayes, B.W. , Runde, B.J. , Markel, E. , Swingle, B.M. Vinatzer, B.A. (2016) Comparative genomics of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato reveals novel chemotaxis pathways associated with motility and plant pathogenicity. PeerJ. 4: e2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert, D. , Franza, T. and Dellagi, A. (2012) Molecular aspects of iron metabolism in pathogenic and symbiotic plant‐microbe associations In: SpringerBriefs in Biometals (Expert D. and O’Brian M.R., eds.), pp. 7–39. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.Y. and Kuo, T.T. (1975) Bacterial leaf blight of rice plant. VI. Chemotactic responses of Xanthomonas oryzae to water droplets exudated from water pores on the leaf of rice plants. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Guvener, Z.T. , Tifrea, D.F. , Harwood, C.S. (2006) Two different Pseudomonas aeruginosa chemosensory signal transduction complexes localize to cell poles and form and remould in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett, D.J. , Britigan, B.E. , Svendsen, T. , Rosen, G.M. and Cohen, M.S. (1987) Bacteria form intracellular free radicals in response to paraquat and streptonigrin. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 13 404–13 408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, J.W. , Tifrea, D.F. , Harwood, C.S. (2005) A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 14 422–14 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javvadi, S. , Pandey, S.S. , Mishra, A. , Pradhan, B.B. and Chatterjee, S. (2018) Bacterial cyclic β‐(1,2)‐glucans sequester iron to protect against iron‐induced toxicity. EMBO Rep. 19, 172–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Pearson, M.A. , Delany, I. , Scarlato, V. and Beier, D. (2005) Phosphate flow in the chemotactic response system of Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology, 151, 3299–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, N.T. , Reddy, A.P.K. , Hsieh, S.P.Y. and Merca, S.D. (1973) An improved technique for evaluation of resistance of rice varieties to Xanthomonas oryzae . Plant Dis. Rep. 57, 537–541. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemu, S. and Leach, J.E. (1990) Cloning and characterization of an avirulence gene from Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 3, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, J.R. (2009) Chemotaxis‐like regulatory systems: unique roles in diverse bacteria. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee., B.M. , Park, Y.J. , Park, D.S. , Kang, H.W. , Kim, J.G. , Song, E.S. ,et al (2005) The genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae KACC10331, the bacterial blight pathogen of rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 577–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. , Butler, S.M. and Camilli, A. (2001) Selection for in vivo regulators of bacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 6889–6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. , Bakker, R.G. , Motaleb, M.A. , Sartakova, M.L. , Cabello, F.C. and Charon, N.W. (2002) Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 6169–6174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, J. , Genin, S. , Magori, S. , Citovsky, V. , Sriariyanum, M. , Ronald, P. , et al (2012) Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 13, 614–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla, M.A. and Krell, T. (2017) The effect of bacterial chemotaxis on host infection and pathogenicity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, fux052 10.1093/femsre/fux052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, R. , Phelps, T.J. , Krieg, N.R. and Benoit, R.E. (1999) Determining chemotactic responses by two subsurface microaerophiles using a simplified capillary assay method. J. Microbiol. Methods, 37, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, P.M. , Danhorn, T. and Fuqua, C. (2007) Motility and chemotaxis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens surface attachment and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8005–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mew, T.W. , Mew, I.C. and Huang, J.S. (1984) Scanning electron microscopy of virulent and avirulent strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae on rice leaves. Phytopathology, 74, 635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Midha, S. , Bansal, K. , Kumar, S. , Girija, A.M. , Mishra, D. , Brahma, K. , et al (2017) Population genomic insights into variation and evolution of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae . Sci. Rep. 7, 40 694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.H. (1992. ) A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia Coli and Related Bacteria, Vol. 1 Cold Spring Harbor: CSHL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.M. , Facincani, A.P. , Ferreira, C.B. , et al (2015) Chemotactic signal transduction and phosphate metabolism as adaptive strategies during citrus canker induction by Xanthomonas citri . Funct. Integr. Genomics, 15, 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb, M.A. , Sultan, S.Z. , Miller, M.R. , Li, C. and Charon, N.W. (2011) CheY3 of Borrelia burgdorferi is the key response regulator essential for chemotaxis and forms a long‐lived phosphorylated intermediate. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3332–3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niňo‐Liu, D.O. , Ronald, P.C. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2006) Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 7, 303–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke, V. and Long, S.R. (1999) Bacterial genes induced within the nodule during the Rhizobium‐legume symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A. and Sonti, R.V. (2010) Role of the FeoB protein and siderophore in promoting virulence of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae on rice. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3187–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.S. , Patnana, P.K. , Lomada, S.K. , Tomar, A. and Chatterjee, S. (2016) Co‐regulation of iron metabolism and virulence associated functions by iron and XibR, a novel iron binding transcription factor, in the plant pathogen Xanthomonas. PLoS Pathog. 12(11), e1006019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.S. , Patnana, P.K. , Rai, S. and Chatterjee, S. (2017a) Xanthoferrin, the α‐hydroxy carboxylate type siderophore of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris is required for optimum virulence and growth inside cabbage. Mol. Plant Pathol. 18, 949–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]