Summary

Plant endo‐β‐1,4‐glucanases (EGases) include cell wall‐modifying enzymes that are involved in nematode‐induced growth of syncytia (feeding structures) in nematode‐infected roots. EGases in the α‐ and β‐subfamilies contain signal peptides and are secreted, whereas those in the γ‐subfamily have a membrane‐anchoring domain and are not secreted. The Arabidopsis α‐EGase At1g48930, designated as AtCel6, is known to be down‐regulated by beet cyst nematode (Heterodera schachtii) in Arabidopsis roots, whereas another α‐EGase, AtCel2, is up‐regulated. Here, we report that the ectopic expression of AtCel6 in soybean roots reduces susceptibility to both soybean cyst nematode (SCN; Heterodera glycines) and root knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita). Suppression of GmCel7, the soybean homologue of AtCel2, in soybean roots also reduces the susceptibility to SCN. In contrast, in studies on two γ‐EGases, both ectopic expression of AtKOR2 in soybean roots and suppression of the soybean homologue of AtKOR3 had no significant effect on SCN parasitism. Our results suggest that secreted α‐EGases are likely to be more useful than membrane‐bound γ‐EGases in the development of an SCN‐resistant soybean through gene manipulation. Furthermore, this study provides evidence that Arabidopsis shares molecular events of cyst nematode parasitism with soybean, and confirms the suitability of the Arabidopsis–H. schachtii interaction as a model for the soybean–H. glycines pathosystem.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, EGase, Heterodera glycines, Meloidogyne incognita, soybean

Introduction

Plant‐parasitic nematodes cause severe damage to a number of major crops and are responsible for billions of dollars of losses worldwide (Koenning et al., 1999). The soybean cyst nematode (SCN; Heterodera glycines), a sedentary and obligate endoparasite, is one of the main yield‐limiting factors in soybean (Glycine max) (Wrather and Koenning, 2006, 2009). As a more desirable method of SCN control than chemical application, genetic resistance to SCN in soybean has been studied extensively (Concibido et al., 1994, 2004; Diers and Arelli, 1999; Diers et al., 1997; Matson and Williams, 1965; Schuster et al., 2001). Several loci (rhg1, rhg2, rhg3 and rhg4) of resistance to SCN have been reported (Caldwell et al., 1960; Concibido et al., 1994, 1997, 2004; Matson and Williams, 1965; Ruben et al., 2006) and, recently, candidate genes for both Rhg1 (Cook et al., 2012; Matsye et al., 2012) and Rhg4 (Liu et al., 2012) have been isolated and confirmed. However, these genes do not provide resistance to all SCN populations. Moreover, the functional characterization of soybean genes related to suspected functions in nematode parasitism is a daunting task, because of the lack of applicable genetic and molecular tools and resources.

SCN is an obligate parasite of soybean roots and feeds only after it has penetrated the root and migrated to the vascular bundle. Infective second‐stage juveniles (J2s) of SCN then initiate localized reorganization of the host's cell morphology and physiology, resulting in the formation of complex multinucleated feeding structures, called syncytia (Jones, 1981; Jung and Wyss, 1999). Nematodes possess a protrusible hollow stylet and feed exclusively from their syncytia, aided by secretions from the nematode oesophageal glands, as they develop into adult males or females and complete their life cycle (Davis et al., 2004). Some of the first oesophageal secretory proteins identified were cellulases of the endo‐β‐1,4‐glucanase (EGase; EC 3.2.1.4) type (De Boer et al., 1999; Smant et al., 1998). The relevance of glucanases in nematode parasitism is indirectly supported by the fact that the nematodes themselves produce and secrete EGases. Rosso et al. (1999) cloned the cDNA Mi‐eng‐1 from Meloidogyne incognita and suggested that this enzyme is involved in cell wall softening during nematode parasitism. EGases were also found to be secreted by cyst nematodes. ENG‐1 and ENG‐2 were found to be released during penetration and intracellular migration by SCN (De Boer et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999; Yan et al., 2001) and by the tobacco cyst nematode (Goellner et al., 2001). Gao et al. (2004) showed that three EGases are secreted by H. glycines during infection of soybean. Two other EGases were also secreted by the migratory root lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans (Uehara et al., 2001).

Syncytium formation and maintenance are known to be accompanied by changes in plant gene expression (reviewed by Davis et al., 2000, 2004; Hussey et al., 2002; Jasmer et al., 2003; Vanholme et al., 2004; Williamson and Gleason, 2003). More recently, root knot and cyst nematode secretions have been found to produce marked changes in host gene expression at the nematode feeding site (Doyle and Lambert, 2003; Huang et al., 2006; Wang X et al., 2005). Among the plant enzymes playing an important role in the development of nematode feeding sites are plant EGases. They are cellulolytic proteins that hydrolyse the β‐1,4‐glucosidic linkages between glucose residues and usually participate in processes such as cell wall biosynthesis and modifications, cell elongation and differentiation, organ abscission (Del Campillo and Bennett, 1996) and fruit ripening (Rose and Bennett, 1999). Plant EGases belong to the glycosyl hydrolase family 9 (GHF9) (Henrissat et al., 2001) and comprise a large multigene family grouped into three distinct subfamilies (Libertini et al., 2004). The α‐ and β‐EGases all have a predicted N‐terminal signal sequence for secretion to the cell wall, whereas γ‐EGases have a GHF9 catalytic core coupled to a long N‐terminal extension, with a membrane‐spanning domain anchoring the protein to the plasma membrane or intracellular organelles (Molhoj et al., 2002; Robert et al., 2005). There are some reports of the expression of EGase genes during nematode infection. Goellner et al. (2001) found five EGases from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) to be up‐regulated on infection with root knot and cyst nematodes. Wang et al. (2007) isolated the NtCel7 promoter and analysed the expression pattern of NtCel7 in soybean, tomato and Arabidopsis using histochemical approaches and transgenic plants. In addition, Mitchum et al. (2004) and Sukno et al. (2006) showed AtCel1‐driven β‐glucuronidase (GUS) expression in tobacco and Arabidopsis on infection with M. incognita.

More recently, changes in EGase gene expression in soybean and Arabidopsis roots during SCN infection have been reported. Tucker et al. (2007) showed that five EGases (GmCel4, GmCel6, GmCel7, GmCel8 and GmCel9) were highly up‐regulated in soybean root fragments containing syncytia induced by SCN infection. Matthews et al. (2011) reported that two soybean genes encoding EGases, BI969418 (Glyma06g48140.1) and BI785739 (Glyma07g11310.1), increased in expression over 60‐fold at 3 days after infection in soybean roots infected with SCN in an incompatible interaction. Meanwhile, Wieczorek et al. (2008), who examined the expression patterns of EGase genes in Arabidopsis roots infected with the cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii using a syncytium‐specific cDNA library, found that most EGases, including the secreted protein AtCel2 and the membrane‐bound protein KOR3, were up‐regulated at the feeding site. Other EGases, however, were down‐regulated, including a secreted protein encoded by At1g48930 and a membrane‐bound protein designated KOR2. They also observed that the number of females in roots 2 weeks after infection was significantly decreased in cel2 and kor3 T‐DNA mutants.

The identification and modification of host genes, such as EGases, which are potentially involved in the soybean–SCN interaction, as indicated by SCN‐induced changes in expression, might prove to be an important tool to aid the development of SCN‐resistant soybean. Exploitation of the extensive genetic knowledge that is available on the model species Arabidopsis thaliana, which is readily infected by the sugar beet cyst nematode (H. schachtii) (Sijmons et al., 1991), a close relative of SCN, may facilitate such a project. Mazarei et al. (2004), who analysed the expression of the Arabidopsis homologue of a soybean gene that was up‐regulated during SCN infection, found that the pair of homologues behaved in a similar fashion following cyst nematode infection, and that the promoter of the Arabidopsis homologue functioned normally in soybean. They suggested that Arabidopsis shares molecular events of cyst nematode parasitism with soybean, and that the Arabidopsis–H. schachtii interaction is a suitable model for the soybean–H. glycines pathosystem.

In this study, we made use of the Arabidopsis–H. schachtii pathosystem in an effort to broaden the resistance of soybean to SCN. Working with four Arabidopsis EGases previously reported by Wieczorek et al. (2008), we examined whether individual ectopic expression of two Arabidopsis EGase genes, AtCel6 (α‐subfamily) and AtKOR2 (γ‐subfamily), and individual suppression of the soybean homologues of AtCel2 (α‐subfamily) and AtKOR3 (γ‐subfamily), in transgenic soybean roots of composite plants can increase soybean resistance to SCN. In addition, soybean roots expressing AtCel6 were evaluated for resistance to root knot nematode (RKN; M. incognita).

Results

Ectopic expression of AtCel6 in soybean roots increases resistance to SCN and RKN

Wieczorek et al. (2008) previously reported that accession At1g48930, encoding a secreted α‐EGase (designated AtCel6 in this study), was down‐regulated in Arabidopsis roots infected with the cyst nematode H. schachtii. Based on their report, we expected a possible role for AtCel6 in the SCN (H. glycines)–soybean interaction, and generated soybean roots expressing AtCel6 to examine the effect of AtCel6 gene expression on SCN infection in the soybean root system.

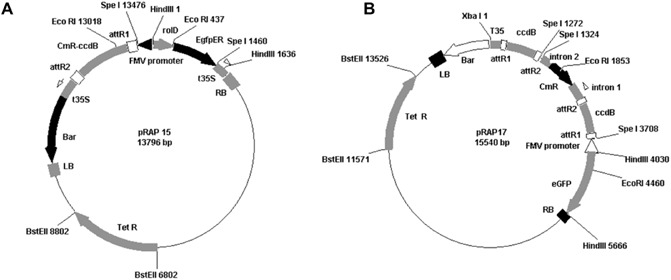

The pRAP15 overexpression vector containing both AtCel6 cDNA, controlled by the Figwort mosaic virus subgenomic transcript (FMV‐sgt) promoter, and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), controlled by the rolD promoter (for visualization of transformed roots), was introduced into roots of the susceptible soybean cultivar ‘Williams 82’ using Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

The pRAP15 (A) and pRAP17 (B) vectors. In both, the cloned DNA sequence replaces the ccdB gene and is inserted into the vector by crossing over between attR sites (on pRAP15 or pRAP17) and attL sites (on pENTR). The Figwort mosaic virus (FMV) promoter drives the expression of the inserted gene or construct. To enable the visualization of transformed roots, the vectors contain the gene encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) controlled by the rolD promoter that gives strong root expression. The gene encoding tetracycline resistance (TetR) provides antibiotic selection. The pRAP17 vector is designed to express double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) using a double pair of Gateway® components with one pair in opposite orientation to the other for easy cloning of DNA fragments in opposite directions. When the cloned DNA fragments are expressed, dsRNA is produced with a hairpin sequence in between. LB, left border; Bar, Basta® resistance gene; t35S, 35S terminator; ccdB, lethality gene; CmR, chloramphenicol resistance gene; RB, right border; attR1, LR bacteriophage γ‐derived recombination site #1; attR2, LR bacteriophage γ‐derived recombination site #2.

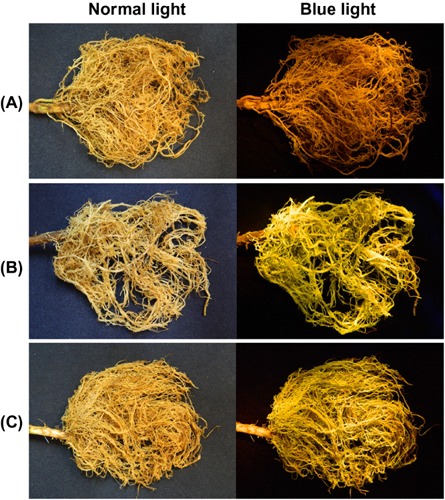

For initial screening, composite plants having roots transformed with pRAP15‐AtCel6 or with empty pRAP15 vector were identified by eGFP fluorescence at 30 days after Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformation. Roots transformed with both pRAP15‐AtCel6 and the empty pRAP15 vector showed eGFP fluorescence under blue light, whereas the non‐transgenic control did not fluoresce (Fig. 2). The transformation efficiency for the formation of composite plants with transformed roots was 63% for the pRAP15 control and 51% for pRAP15‐AtCel6. Overexpression of AtCel6 in soybean roots produced no obvious morphological or physiological plant phenotype changes compared with the empty vector controls.

Figure 2.

Appearance of soybean roots expressing AtCel6 30 days after Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformation under normal light (left) and blue light (right). (A) Non‐transgenic control roots. (B) Roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector exhibiting enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fluorescence. (C) Roots transformed with the pRAP15‐AtCel6 construct exhibiting eGFP fluorescence.

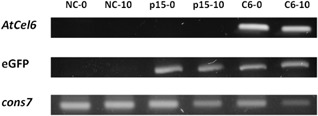

Transgenic roots were analysed for the presence and expression of the AtCel6 gene insert. Total RNA was extracted from roots transformed with pRAP15‐AtCel6 and with the empty pRAP15 vector and from non‐transgenic control roots immediately before SCN inoculation and at 10 days after inoculation (10 dai). A cDNA library was made from the RNA and used as the template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed using AtCel6 internal primers and an eGFP‐specific primer set (Table 1). A 301‐bp fragment was amplified with AtCel6 internal primers only from roots transformed with AtCel6, whereas a 706‐bp fragment was amplified with the eGFP primer set from roots transformed with both AtCel6 and the empty pRAP15 vector (Fig. 3). PCR with primers designed for cons7, a constitutively expressed soybean metalloprotease gene used as a non‐target control, resulted in amplification from all samples (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Primers used in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing

| Primer | Sequences (5′–3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| AtCel6‐OE | F, CACCTGGAGAGAAAACTTAGA | 2002 |

| R, GCTCAACTTGGTTGGCTATGT | ||

| AtKOR2‐OE | F, CACCAAACCTTAATCATCCA | 1906 |

| R, TTTCAAGGCTTCCAGGCTTT | ||

| GmCel7‐KO | F, CACCTCATGGAGCGTTATTG | 249 |

| R, CAGTTTCTGCGGCAACTTCTG | ||

| GmKOR3‐KO | F, CACCCGCTTTAGACGAGACA | 134 |

| R, AGAGTGCCGAGTGTCCAGAT | ||

| M13 | F, GTAAAACGACGGCCAG | — |

| R, CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC | ||

| FMV‐F | F, GGAGCCCTCCAGCTTCAAAG | — |

| Intron‐R | R, ATATGGACACGTTAACTGG | — |

| eGFP | F, ATCGATGAATTTGTTCGTGAACTATTAGTTGCGG | 706 |

| R, ATCGATGCATGCCTGCAGGTCACTGGATTTTG | ||

| Ri | F, TCAGCCTCCCCGCCGGATG | 812 |

| R, ATGCAAAAGACAGGATTGATCGCA | ||

| AtCel6‐internal | F, GCCATTGAGGAAGCTGGTAAG | 301 |

| R, GGATCTTATGGAGGAGGATC | ||

| cons7 | F, CTGTGCTCATGCAGAGGAAT | 134 |

| R, CTCGTGGAGTTTGGTCTCAA | ||

| GmCel7‐qPCR | F, GATTGCTGTACACCCGGGAA | 112 |

| R, CCGATCTGGTCCACCAACAA |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Figure 3.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of AtCel6 and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) gene expression in non‐transgenic control roots (NC), control roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector (p15) and roots transformed with the pRAP15‐AtCel6 construct (C6) at two time points. The constitutively expressed soybean gene cons7 was used as a positive control. NC‐0, NC at 0 days after inoculation (dai); NC‐10, NC at 10 dai; p15‐0, p15 at 0 dai; p15‐10, p15 at 10 dai; C6‐0, C6 at 0 dai; C6‐10, C6 at 10 dai.

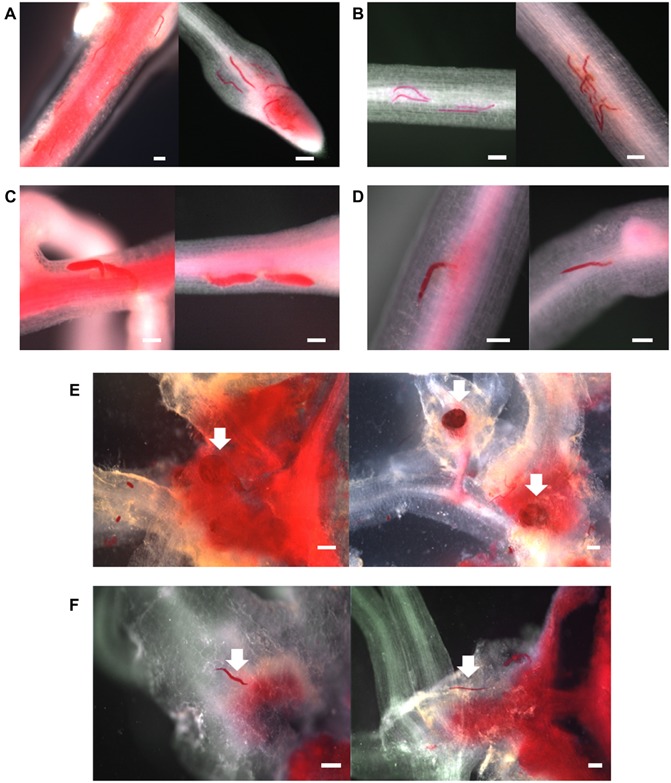

SCNs were visualized by staining with acid fuchsin to monitor SCN invasion and development inside roots. A comparison of infection of pRAP15‐AtCel6 transformed roots with the pRAP15 control revealed similar numbers of nematodes penetrating the root and no developmental difference between them at 3 dai (Fig. 4A,B). However, at 10 dai, most nematodes were developing normally and exhibited a swollen shape in roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector, whereas nematodes in roots transformed with pRAP15‐AtCel6 were still thin and small, showing interrupted nematode development (Fig. 4C,D). RKN (M. incognita) development inside roots was also monitored, and gall formation on the roots was examined at 35 dai. Many nematodes reached the adult stage in roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector, forming abundant galls and producing egg masses (Fig. 4E). In contrast, in pRAP15‐AtCel6 transformed roots, gall formation was not severe and nematodes were still thin and had not developed to the adult stage (Fig. 4F). These results show that the expression of AtCel6 in soybean roots interferes with the nematode life cycle, interrupting nematode development after SCN or RKN inoculation.

Figure 4.

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) development at two time points (A–D) and root knot nematode (RKN) development at 35 days (E,F) after soybean root inoculation. SCNs are more mature and larger in control roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector than in roots expressing AtCel6 at 10 days after inoculation (dai) (A–D). The number of RKN galls is greater in roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector than in roots expressing AtCel6 (E,F). (A) Control roots at 3 dai. (B) Roots expressing AtCel6 at 3 dai. (C) Control roots at 10 dai. (D) Roots expressing AtCel6 at 10 dai. (E) Control roots at 35 dai. (F) Roots expressing AtCel6 at 35 dai. The white arrows point to RKN. Bars, 500 μm.

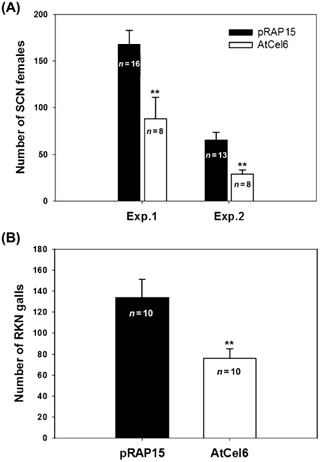

The effect of overexpression of AtCel6 in soybean roots on the development of SCN and RKN was quantified by counting the number of mature SCN females or RKN galls per plant on roots transformed with either pRAP15‐AtCel6 or the empty pRAP15 control at 35 dai. Averaging the results of two independent SCN assays, there was a 51% reduction in the number of SCN females for plants with pRAP15‐AtCel6 transformed roots, compared with the results for roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector (Fig. 5A). The average number of RKN galls on roots transformed with pRAP15‐AtCel6 was 76 galls per plant versus an average of 134 galls per plant for the pRAP15 control, representing a 43% decrease (Fig. 5B). These differences are considered to be statistically significant (P < 0.01), indicating that ectopic expression of AtCel6 in soybean roots increases soybean resistance to both SCN and RKN.

Figure 5.

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) and root knot nematode (RKN) susceptibility of soybean roots expressing AtCel6. (A) Number of mature SCN females per plant at 35 days after inoculation (dai) on control roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector and on roots expressing AtCel6. The susceptibility to SCN was measured in two independent experiments (Exp. 1 and Exp. 2). (B) Number of RKN galls per plant at 35 dai on control roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 vector and on roots expressing AtCel6. Bars represent means and SEM, with the number of replications noted. **Significantly different from the control (P < 0.01).

Suppression of GmCel7, a soybean homologue of AtCel2, increases resistance to SCN in soybean roots

The Arabidopsis gene Cel2 (AtCel2) also encodes a secreted α‐EGase, but, in contrast with AtCel6, AtCel2 is up‐regulated in Arabidopsis roots infected by H. schachtii (Wieczorek et al., 2008). Soybean homologues of AtCel2 were identified on the basis of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences through database comparisons at the Phytozome website (http://www.phytozome.net). The deduced amino acid sequence of AtCel2 (At1g02800.1) is highly conserved in the closest soybean homologue Gm02g01990.1 (designated GmCel7 in the GenBank database), for which the encoded protein has 75% identity and 91% similarity to AtCel2 (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information). As shown in Fig. S1, GmCel7 and AtCel2 robustly share the GHF9 motif, a known conserved domain of EGases, suggesting that GmCel7 and AtCel2 play a similar role in SCN‐infected soybean roots.

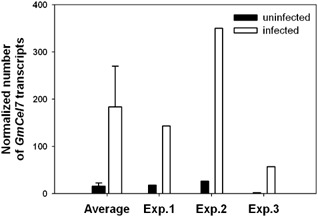

In order to examine the effect of SCN infection on the expression of the GmCel7 gene in soybean roots, total RNA was extracted from SCN‐infected soybean roots and from uninfected control roots at 10 dai, and real‐time quantitative PCR analyses were performed on three biological replicates. The level of GmCel7 expression was expressed as the number of GmCel7 transcripts normalized by the number of transcripts of the reference gene cons7. The average level of expression of GmCel7 was 11 times higher in SCN‐infected soybean roots than in uninfected ones, suggesting that the suppression of GmCel7 might reduce soybean root susceptibility to SCN (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of GmCel7 gene expression in soybean cyst nematode (SCN)‐infected and uninfected soybean roots. Total RNA from infected and uninfected control soybean roots was extracted at 10 days after SCN inoculation, respectively. The level of expression of GmCel7 is expressed as the number of GmCel7 transcripts normalized by the number of transcripts of the reference gene cons7, as determined by real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis. The ‘Average’ bar represents the mean of the results for three biological replicates.

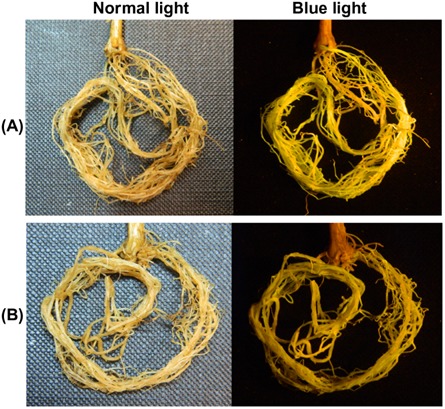

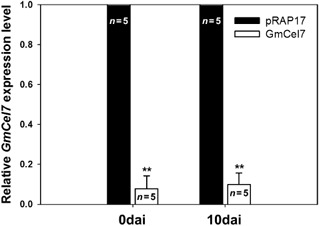

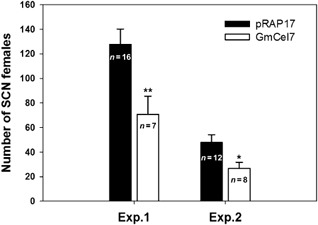

To evaluate the effect of the suppression of expression of GmCel7 on SCN infection of soybean roots, soybean roots were transformed with the pRAP17‐GmCel7 RNAi vector (Fig. 1B). For initial screening, roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmCel7 and with the empty pRAP17 vector were identified by eGFP fluorescence under blue light 30 days after A. rhizogenes transformation (Fig. 7). The transformation efficiency for the formation of composite plants with transformed roots was 57% for the pRAP17 control and 52% for pRAP17‐GmCel7. Suppression of GmCel7 in soybean roots was not accompanied by obvious morphological or physiological plant phenotype changes. The transcript level of GmCel7 in pRAP17‐GmCel7 transformed roots was determined by real‐time quantitative PCR. Total RNA was extracted separately from roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmCel7 and with the empty pRAP17 vector, both immediately before inoculation with SCN and at 10 dai. Real‐time quantitative PCR was performed using a GmCel7‐qPCR primer set for the GmCel7 target gene, with the cons7 gene as an internal control for normalization of the results (Table 1). GmCel7 was noticeably down‐regulated in roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmCel7 relative to pRAP17 control roots at both time points, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8). Averaging the results of two independent SCN assays, there was a 44% reduction in the number of mature SCN females per plant for roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmCel7, compared with the results for pRAP17 control roots (Fig. 9). Thus, suppression of GmCel7 expression in SCN‐infected soybean roots increased soybean resistance to SCN.

Figure 7.

Appearance of soybean roots transformed with the pRAP17‐GmCel7 RNAi construct under normal light (left) and blue light [right, showing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fluorescence] 30 days after Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformation. (A) Control roots transformed with the empty pRAP17 vector. (B) Roots transformed with the pRAP17‐GmCel7 construct.

Figure 8.

Relative expression levels of GmCel7 in soybean roots transformed with the pRAP17‐GmCel7 RNAi construct (white bars) and with the empty pRAP17 vector (black bars). Total RNA was extracted from roots immediately before soybean cyst nematode (SCN) inoculation [0 days after inoculation (dai)] and at 10 dai. Bars represent means (and SEM for GmCel7 plants) of results for five individual plants. **Mean significantly different from the control (P < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) susceptibility of soybean roots with suppressed expression of GmCel7. The numbers of mature SCN females per plant at 35 days after inoculation (dai) on roots transformed with the empty pRAP17 vector and with the pRAP17‐GmCel7 RNAi construct were measured in two independent experiments (Exp. 1 and Exp. 2). Bars represent means and SEM, with the number of replications noted. *Mean significantly different from the control (P < 0.05). **Mean significantly different from the control (P < 0.01).

Two γ‐EGases, AtKOR2 and GmKOR3, have no significant effect on SCN response

In a study of gene expression at the feeding site of Arabidopsis roots infected with the cyst nematode H. schachtii, Wieczorek et al. (2008) reported that the Arabidopsis gene KOR3 (AtKOR3; At4g24260.1), encoding a membrane‐bound γ‐EGase, was up‐regulated, whereas a gene encoding another membrane‐bound γ‐EGase, AtKOR2 (At1g65610.1), was down‐regulated. Composite soybean plants with transgenic roots were produced to determine whether ectopic expression of AtKOR2 or suppression of the soybean homologue of AtKOR3 could increase resistance to SCN in soybean roots.

Soybean homologues of AtKOR3 were identified as described above. The deduced amino acid sequence of AtKOR3 (At4g24260.1) is highly conserved in the closest soybean homologue Gm17g00710.1 (designated GmKOR3 in this study), for which the encoded protein has 73% identity and 89% similarity to AtKOR3 (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information). The two proteins also robustly share the GHF9 motif.

The transcript level of GmKOR3 in pRAP17‐GmKOR3 transformed roots was determined by real‐time quantitative PCR. Total RNA was extracted separately from roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmKOR3 and with the empty pRAP17 vector, both immediately before inoculation with SCN and at 10 dai. GmKOR3 was remarkably down‐regulated in roots transformed with pRAP17‐GmKOR3 compared with pRAP17 control roots at both time points, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. S3, see Supporting Information).

Soybean roots transformed with pRAP15‐AtKOR2 or pRAP17‐GmKOR3 were subjected to SCN assay. Neither construct significantly affected the number of SCN females per plant, compared with the results for roots transformed with the empty pRAP15 or pRAP17 vectors (data not shown).

Discussion

Both the ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis α‐EGase gene AtCel6 and suppression of the soybean homologue (GmCel7) of another α‐EGase, AtCel2, reduced the number of mature SCN (H. glycines) females on SCN‐infected soybean roots. In contrast, both the ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis γ‐EGase gene AtKOR2 and suppression of the soybean homologue (GmKOR3) of another γ‐EGase, AtKOR3, in soybean roots had no significant effect on SCN parasitism.

Plant EGases are grouped into three distinct subfamilies. The α‐ and β‐subfamilies contain secreted and soluble EGases which are involved in physiological roles, such as elongation, ripening and abscission. The γ‐subfamily, also referred to as the KOR subfamily, is composed of proteins having a membrane‐spanning domain (Libertini et al., 2004). Although the secreted EGases are likely to act in all layers of the cell wall, including the outermost layer, the plasma membrane‐anchored EGases may act only at the innermost layers of the cell wall facing the plasma membrane (Molhoj et al., 2002). The results of our investigation of two α‐EGases and two γ‐EGases revealed that individual genetic manipulation of the two α‐EGases in soybean roots significantly affected SCN parasitism, suggesting that the structural divergence between secreted and membrane‐anchored EGases results in a functional difference between the two types of EGase with regard to SCN parasitism.

Soybean roots transformed with AtCel6 also showed a significant decrease in the number of RKN (M. incognita) galls. Although the mechanisms of giant cell and syncytium formation differ, these nematode feeding cells share several characteristics in common, including localization in vascular tissue adjacent to xylem elements, dense cytoplasm, organelle proliferation, and elaborate thickening and ingrowths of peripheral cell walls (Hussey and Grundler, 1998). According to Goellner et al. (2001), both cyst nematodes and RKN recruit plant EGase activity as one component of the extensive remodelling of cell walls that occurs within their respective feeding cells. Thus, genetic modification of some EGases may be an effective method to increase plant resistance to both SCN and RKN.

Many resistance (R) genes have been cloned from various plant species. They encode proteins that contain tandem leucine‐rich repeats (LRRs) and have highly conserved functional domains, such as the nucleotide binding (NB) domains and core residues of the LRRs. These features are retained even among distantly related R genes (McDowell and Woffenden, 2003; Williamson, 1999; Williamson and Hussey, 1996), suggesting that most plant species share plant–pathogen interaction mechanisms. Arabidopsis has been widely used as a model to study plant–pathogen interactions. Many crops and Arabidopsis share similar modes of action regarding disease resistance. For example, the homologues of the avr genes of bean and pea (Dangl et al., 1992) and an SCN‐induced gene of soybean (Mazarei et al., 2004) were identified in Arabidopsis and behaved in a similar fashion. Conversely, Arabidopsis resistance genes effective against crop pathogens have been identified and found to have the same functionality in crops. For example, the tomato carrying the Arabidopsis NPR1 (nonexpresser of pathogenesis‐related 1) gene (Lin et al., 2004) and the soybean carrying the Arabidopsis PAD4 (phytoalexin deficient 4) (Youssef et al., 2013) and PSS1 (Phytophthora sojae susceptible 1) (Sumit et al., 2012) genes provided resistance to certain pathogens. In addition, Wang Z et al. (2005) reported that a transgenic Arabidopsis coi1‐1 mutant expressing the soybean homologue (GmCOI1) of the Arabidopsis COI1 (coronatine insensitive 1) gene was found to exhibit normal jasmonate responses, resulting in plant defence against Botrytis cinerea and Erwinia carotovora. These findings, together with the results reported here, suggest that the non‐leguminous Arabidopsis plant shares molecular events that occur during cyst nematode parasitism with the leguminous soybean plant.

Arabidopsis is a host plant for several species of RKN and the cyst nematode H. schachtii. Transgenic Arabidopsis lines containing reporter gene constructs whose expression is modulated by nematode infection have been generated by Williamson and Hussey (1996). DNA constructs designed to confer resistance to nematodes can be tested using Arabidopsis as a model system. Those constructs providing increased resistance can be engineered into important crops to promote host resistance against the nematodes. For example, genes encoding proteins detrimental to nematodes may be engineered into crop plants to block the establishment of a feeding site or to interrupt feeding cell development (Williamson and Hussey, 1996).

In this study, we identified the genes encoding endo‐β‐1,4‐glucanases essential for the development of nematode feeding sites based on the Arabidopsis–pathogen pathosystem. The genes were transferred into soybean roots, demonstrating that these genes can confer some resistance to nematodes in soybean. Nematodes in the genera Heterodera and Globodera of the cyst nematodes and the genus Meloidogyne of the RKNs have complex interactions with their host plants that result in major morphological and developmental changes in both organisms (Williamson and Hussey, 1996). Soybean genotypes display a range of resistance to SCNs and/or RKNs, showing continuous phenotypic variation ranging from high susceptibility to high resistance conferred by multiple genes. Therefore, soybean R genes against the nematodes contribute only small additive effects to resistance in soybean (Concibido et al., 2004; Luzzi et al., 1994; Youssef et al., 2013). A single soybean R gene has not been identified that provides full resistance to all populations of soybean cyst nematodes and RKNs. Therefore, it may be necessary to pyramid R genes to confer full resistance in soybean to these nematodes.

In conclusion, this work provides a basis for further exploration of the significant role of EGases in nematode resistance in soybean, and translates the knowledge gained from the model plant, Arabidopsis, to a field crop, soybean.

Experimental Procedures

Gene isolation and vector construction

Total RNA was extracted from G. max roots and Arabidopsis thaliana plants using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA. The RNA was employed to synthesize first‐strand cDNA using a Super Script III First‐Strand Synthesis System Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) with oligo d(T) as the primer, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Open reading frames (ORFs) of AtCel6 (Phytozome accession no. At1g48930.1) and AtKOR2 (At1g65610.1) for the overexpression vector constructs were amplified from Arabidopsis cDNA using gene‐specific primers, and PCR primers for RNAi vector constructs of GmCel7 (Glyma02g01990.1) and GmKOR3 (Glyma17g00710.1) genes were designed to amplify gene fragments that were 200–500 base pairs (bp) in length from soybean cDNA (Table 1). All primer sets for vector constructs contained CACC at the 5′ end of the forward primer, which is necessary for directional cloning using the Gateway® (Invitrogen) system. The PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel and extracted using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The purified PCR fragments were cloned into the pENTR cloning vector using a pENTR™ Directional TOPO® Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). Vectors containing the genes of interest were transformed into competent Escherichia coli cells using One Shot® Mach1™‐T1R chemically competent E. coli (Invitrogen). Transformed E. coli were grown and harvested using a QIAprep® Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), and the plasmid contents were confirmed by DNA sequencing using the vector‐specific primers M13‐F and M13‐R (Table 1).

The AtCel6 and AtKOR2 constructs were transferred to the gene expression vector pRAP15 (Fig. 1A; Matsye et al., 2012) between the attR1 and attR2 sites designed for directional cloning using Invitrogen's Gateway® technology mediated by LR Clonase™ II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). In this vector, the FMV‐sgt promoter drives expression of the inserted gene. To enable visualization of transformed roots, the vector contains the gene encoding eGFP (Haseloff et al., 1997) controlled by the rolD promoter, which gives strong root expression. The gene encoding tetracycline resistance (TetR) provides antibiotic selection. The Clonase II reaction product was used to transform E. coli cells as described above with selection on 10 μg/mL tetracycline plates. The presence of the insert in the correct orientation downstream from the FMV promoter was confirmed by PCR using the FMV promoter‐specific primer FMV‐F and the gene‐specific reverse primer (Table 1).

The GmCel7 and GmKOR3 RNAi constructs were moved from the pENTR vector to pRAP17 (Klink et al., 2009) using Invitrogen's Gateway® technology. pRAP17 is designed to express double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) using a double pair of Gateway® components; one pair is in opposite orientation to the other pair for easy cloning of DNA fragments in opposite directions. When the cloned DNA fragments are expressed, dsRNA is produced with a hairpin sequence in between (Fig. 1B). The cloning reaction was mediated by Gateway® LR clonase™ II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). The RNAi DNA fragments replace the ccdB genes and are inserted into the vector by the crossing over between the attR sites (on pRAP17) and attL sites (on pENTR). Transformation into the pRAP17 vector was confirmed by PCR using three different primer sets. The first primer set was used to confirm the presence of the RNAi fragment in the forward direction using the gene‐specific forward primer and intron 1 reverse primer Intron‐R (Table 1). The second was used to confirm the presence of the FMV promoter and the RNAi fragment in the reverse direction using FMV‐F and the gene‐specific reverse primer (Table 1). The vector pRAP17 also contains the gene encoding eGFP under control of the rolD promoter. Finally, the presence of the eGFP gene was confirmed using forward and reverse primers specific to the eGFP gene (Table 1).

Transformed pRAP15 and pRAP17 clones were moved individually to competent A. rhizogenes ‘K599’ cells (Haas et al., 1995) using the freeze–thaw method (Hofgen and Willmitzer, 1988) and the transformations were confirmed by PCR as described above. The presence of the gene encoding eGFP was confirmed by PCR using eGFP‐F and eGFP‐R primers (Table 1), and eGFP was confirmed visually in transgenic roots. The presence of the A. rhizogenes Ri plasmid, which is necessary for root transformation, was confirmed by PCR using Ri‐F and Ri‐R primers (Table 1).

Soybean root transformation

The co‐cultivation medium for the generation of transformed soybean roots was prepared by growing each transformed A. rhizogenes clone in 5 mL of Terrific Broth (TB; Research Products International Group, Mount Prospect, IL, USA) medium containing 5 μg/mL tetracycline overnight at room temperature on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The 5‐mL culture was used to inoculate a 1‐L flask of TB + 5 μg/mL tetracycline medium, and was incubated on a rotary shaker at 135 rpm overnight at room temperature. The culture was centrifuged at 2800 g at 4 °C for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with 3% sucrose (pH 5.7) according to Klink et al. (2009). A mock co‐cultivation medium (MS medium lacking A. rhizogenes) was prepared for the non‐transformed control plants.

Composite soybean plants containing untransformed shoots and transformed roots were generated as described previously (Ibrahim et al., 2011; Klink et al., 2009). Agrobacterium rhizogenes containing the pRAP15 or pRAP17 vector with no gene of interest inserted was grown to create vector‐only control roots. For each gene to be tested, 100 soybean plants (cv. William 82; PI 518671) were grown in Promix for 7 days before transformation. The plants were cut at the soil line with a razor blade and the stem ends were placed into small beakers containing transformed A. rhizogenes suspended in co‐cultivation solution. The beakers were placed into a vacuum chamber for 30 min to infiltrate the co‐cultivation solution into the plants. The vacuum was released and the plants were co‐cultivated overnight at 23 °C on a rotary shaker at 65 rpm. The plant stems were washed with deionized distilled water to remove excess A. rhizogenes, placed in a small beaker containing distilled water and stored for approximately 48 h at 23 °C in an illuminated growth chamber. The plantlets were planted in 50‐cell flats filled with pre‐wetted Promix in a glasshouse. Four weeks after planting, the Promix was washed from the plant roots and the plants were screened to identify transformed roots. Transformed roots expressing eGFP fluorescence were recognized by their green colour when viewed under a Dark Reader Spot Lamp (Clare Chemical Research, Dolores, CO, USA), whereas non‐transformed roots did not exhibit eGFP fluorescence. Non‐eGFP roots were partially removed to encourage the growth of transformed roots and the plants were replanted in Promix. Control plants were trimmed in a similar manner. After 2 weeks, non‐eGFP roots were removed completely and control plants were trimmed to a similar degree. Twelve transformed composite plants were used in each nematode assay, together with 15–20 empty pRAP15 or pRAP17 control plants and 15–20 non‐transformed control plants.

Nematode preparation and inoculation

SCN population NL1‐RHg was grown in a glasshouse (average temperature, 22 °C; photoperiod, 16 h light/8 h dark cycle) at the US Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD, USA, as described previously (Klink et al., 2007).

SCN (H. glycines) females were harvested from soybean (G. max) roots 2–4 months after inoculation. The females were purified by sucrose flotation (Jenkins, 1964) and then crushed gently to release the eggs. The eggs were sterilized by 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 1.5 min and then washed with sterile water and placed in a small plastic tray with 120 mL of sterile water and 1.2 mL of sterile 300 mM ZnSO4.7H2O. The tray was placed on a heated shaker at 28 °C and 50–75 rpm for aeration. After 3 days, the J2s were separated from unhatched eggs through a 25‐μm nylon cloth mesh and concentrated to a final optimized concentration of 1000 J2s/mL. Two millilitres of J2 inoculum were added to each root system of transgenic roots of composite plants for the SCN susceptibility assay. The plants were grown in sand in the glasshouse for 35 days, and mature females were harvested as described below.

RKN (M. incognita) females were harvested from roots of pepper (Capsicum annuum) cultivar PA136 2–4 months after inoculation. Eggs used to inoculate roots of soybean seedlings were extracted using a 1% NaOCl solution (Zhou et al., 1998). The concentration of the egg suspension was adjusted to 1500 eggs/mL. Two millilitres of inoculum were added to each root system. The plants were grown in sand in the glasshouse for 35 days, and RKN galls were counted as described below.

SCN female and RKN gall counts

Thirty‐five days after inoculation with SCN, test plants were placed in water and the roots were gently rubbed to dislodge female nematodes. These were collected between nested 850‐ and 250‐μm sieves and washed onto lined filter paper in a Buchner funnel system under constant vacuum (Krusberg et al., 1994). Females were counted under a dissecting microscope. Fresh and dry weights for each root ball were recorded for each plant. For the RKN assay, roots were washed free of sand. After the fresh root weight had been recorded, the RKN galls were counted.

Outliers in the data were removed using Grubbs' test (Grubbs, 1969) at the GraphPad QuickCalcs website (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/grubbs1/). The normality of the data was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965; online version implemented by S. Dittami, http://dittami.gmxhome.de/shapiro/). Means were compared using PROC TTEST from SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Measurement of gene expression levels by real‐time quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from three to five individual biological replicates at each time point (0 and 10 dai) using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Roots having the strongest eGFP expression and highest root quality were selected. RNA from soybean roots transformed with the empty pRAP17 vector containing no gene of interest was used as a control to measure endogenous gene expression. The RNA was treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA and then employed to synthesize cDNA using the SuperScript III First‐Strand Synthesis System Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. Gene‐specific primers targeted to flanking regions of the RNAi segments were designed using Primer 3 software (Table 1) to yield PCR‐amplified fragments of approximately 100 bp. Primer pair specificity was initially tested by running the PCR products on an agarose gel to ensure that a single band of the expected size was obtained. The constitutively expressed soybean metalloprotease gene cons7 (AW310136) was used as an internal control in the RNA samples to normalize the results (Libault et al., 2008), and specific primers was designed (Table 1). Negative controls for quantitative PCR included reactions containing no template and reactions with the DNAse‐treated RNA as the template to ensure the absence of genomic DNA. These controls resulted in no amplification. The quantitative PCRs were conducted in triplicate for each root cDNA sample using Brilliant II SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Relative quantities of gene expression were determined with serial dilutions over a five‐log range using the Stratagene Mx 3000P Real‐Time PCR System (Stratagene). DNA accumulation during the reaction was measured with SYBR Green with ROX (6‐Carboxyl‐X‐Rhodamine) as the reference dye. PCR efficiencies were equal in each case and greater than 90%. The Ct value (cycle at which there is the first clearly detectable increase in the fluorescence) was calculated using the software provided with the Stratagene Mx 3000P Real‐Time PCR system. Dissociation curves showed amplification for only one product for each primer set.

For quality assurance purposes, only quantitative PCR assays that resulted in standard curves with the following parameters (Bustin, 2002) were considered: (i) linear standard curve throughout the measured area; (ii) standard curve slope between −3.6 and −3.1; and (iii) R 2 value above 0.99. The Ct values for each of the RNA samples were normalized to a value determined by comparing the cons7 regression line of the individual cDNA samples with the collective regression line of the combined RNA samples.

Root staining procedure and microscopy examination

To monitor nematode invasion and development inside the roots, at 3 and 10 dai for SCN and at 35 dai for RKN, plant roots were stained with acid fuchsin according to Byrd et al. (1983) and Mahalingan and Skorupska (1996). Briefly, roots were washed in gently flowing tap water to remove soil and debris, cut into 2‐cm segments, placed in a small beaker and soaked in 20–30 mL of 10% commercial Clorox (chlorine bleach, 5.25% NaOCl) for 3 min. The roots were rinsed in tap water and then transferred to a 50‐mL glass bottle containing 20 mL of distilled water and left to boil in a microwave with loosened cap. A 500‐μL aliquot of acid fuchsin (0.15 g/10 mL H2O) and 500 μL of glacial acetic acid were added to the root samples and heated to boiling in a microwave twice. The roots were left to cool to room temperature before removing the excess stain with running tap water using Miracloth on the top of the bottle. Twenty millilitres of clearing reagent (1/3 lactic acid + 1/3 glycerol + 1/3 distilled water) was added to the roots and they were left to de‐stain for 2 h to overnight. The nematodes were stained red as observed in the roots under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ 1500 Stereomicroscope; Nikon Corporation, Melville, NY, USA). Stereomicroscopic images were captured with an Optronics Magna Fire model S99802 CCD camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA, USA).

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of AtCel2 (At1g02800.1) and its soybean homologue GmCel7 (Gm02g01990.1). GmCel7 shares 75% identity and 91% similarity with AtCel2. Sequences were aligned with the clustalw program. Dashes indicate gaps in the amino acid sequences used to optimize alignment. Regions of identical (dark grey shade, asterisks) and similar (light grey shade, dots) amino acids are indicated. Underlining identifies the GHF9 gene motif.

Fig. S2 Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of AtKOR3 (At4g24260.1) and its soybean homologue GmKOR3 (Gm17g00710.1). GmKOR3 shares 73% identity and 89% similarity with AtKOR3. Sequences were aligned with the clustalw program. Dashes indicate gaps in the amino acid sequences used to optimize alignment. Regions of identical (dark grey shade, asterisks) and similar (light grey shade, dots) amino acids are indicated. Underlining identifies the GHF9 gene motif.

Fig. S3 Expression level of GmKOR3 gene of transformed soybean roots with pRAP17‐GmKOR3. Each total RNA from the empty pRAP17 control and transformed soybean roots with pRAP17‐GmKOR3 was extracted at 0 days after soybean cyst nematode (SCN) inoculation (before inoculation) and at 10 days after inoculation (dai), respectively. GmKOR3 gene expression was measured as the copy number of the transcripts normalized by the copy number of the reference gene (cons7) through real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction analysis. The white bar represents the mean of the relative GmKOR3 gene expression level of pRAP17‐GmKOR3 transformed individual plants (n = 5) compared with empty pRAP17 controls (black bar, n = 5), with the standard errors of the mean noted. The asterisks (**) denote the mean value significantly different from the empty pRAP17 control as determined by PROC TTEST (P < 0.01).

Acknowledgements

DNA sequencing was performed by Patrick Elia, USDA‐ARS Soybean Genomics and Improvement Laboratory, Beltsville, MD, USA. This research was supported by a grant from the BioGreen 21 program (project no. PJ007031200802), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bustin, S.A. (2002) Quantification of mRNA using real‐time reverse transcription PCR (RT‐PCR): trends and problems. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 29, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, D.W. , Kirkpatrick, T. Jr and Barker, K.R. (1983) An improved technique for clearing and staining plant tissues for detection of nematodes. J. Nematol. 15, 142–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.E. , Brim, C.A. and Ross, J.P. (1960) Inheritance of resistance of soybeans to the cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines . Agron. J. 52, 635–636. [Google Scholar]

- Concibido, V.C. , Denny, R.L. , Boutin, S.R. , Hautea, R. , Orf, J.H. and Young, N.D. (1994) DNA marker analysis of loci underlying resistance to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines Ichinohe). Crop Sci. 34, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Concibido, V.C. , Lange, D.A. , Denny, R.L. , Orf, J.H. and Young, N.D. (1997) Genome mapping of soybean cyst nematode resistance genes in ‘Peking’, PI 90763, and PI 88788 using DNA markers. Crop Sci. 37, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Concibido, V.C. , Diers, B.W. and Arelli, P.R. (2004) A decade of QTL mapping for cyst nematode resistance in soybean. Crop Sci. 44, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.E. , Lee, T.G. , Guo, X. , Melito, S. , Wang, K. , Bayless, A.M. , Wang, J. , Hughes, T.J. , Willis, D.K. , Clemente, T.E. , Diers, B.W. , Jiang, J. , Hudson, M.E. and Bent, A.F. (2012) Copy number variation of multiple genes at Rhg1 mediates nematode resistance in soybean. Science, 338, 1206–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L. , Ritter, C. , Gibbon, M.J. , Mur, L.A. , Wood, J.R. , Godd, S. , Mansfield, J. , Taylor, J.D. and Vivian, A. (1992) Functional homologs of the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance gene in bean and pea. Plant Cell, 5, 1359–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.L. , Hussey, R.S. , Baum, T.J. , Baker, J. , Schots, A. , Rosso, M.N. and Abad, P. (2000) Nematode parasitism genes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38, 365–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.L. , Hussey, R.S. and Baum, T.J. (2004) Getting to the roots of parasitism by nematodes. Trends Parasitol. 20, 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, J.M. , Yan, Y. , Wang, X. , Smant, G. , Hussey, R.S. , Davis, E.L. and Baum, T.J. (1999) Developmental expression of secretary β‐1,4‐endoglucanases in the subventral esophageal glands of Heterodera glycines . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 12, 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campillo, E. and Bennett, A.B. (1996) Pedicel break strength and cellulose gene expression during tomato flower abscission. Plant Physiol. 111, 813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diers, B.W. and Arelli, P.R. (1999) Management of parasitic nematodes of soybean through genetic resistance. In: Proceedings of the 6th World Soybean Research Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 4–7 August 1999 (Kauffman H.E., ed.), pp. 300–306. Champaign: Superior Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Diers, B.W. , Arelli, P.R. and Kisha, T.J. (1997) Genetic mapping of soybean cyst nematode resistance genes from PI 88788. Soybean Genet. Newsl. 24, 194–195. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, E.A. and Lambert, K.N. (2003) Meloidogyne javanica chorismate mutase 1 alters plant cell development. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 16, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B. , Allen, R. , Davis, E.L. , Baum, T.J. and Hussey, R.S. (2004) Molecular characterization and developmental expression of a cellulose‐binding protein gene in the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines . Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 1377–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goellner, M. , Wang, X. and Davis, E.L. (2001) Endo‐β‐1,4‐glucanase expression in compatible plant–nematode interaction. Plant Cell, 13, 2241–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs, F. (1969) Procedures for detecting outlying observations in samples. Technometrics, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, J.H. , Moore, L.W. , Ream, W. and Manulis, S. (1995) Universal PCR primers for detection of phytopathogenic Agrobacterium strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2879–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseloff, J. , Siemering, K.R. , Prasher, D.C. and Hodge, S. (1997) Removal of a cryptic intron and subcellular localization of green fluorescent protein are required to mark transgenic Arabidopsis plants brightly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2122–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat, B. , Coutinho, P.M. and Davies, G.J. (2001) A census of carbohydrate‐active enzymes in the genome of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 55–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofgen, R. and Willmitzer, L. (1988) Storage of competent cells for Agrobacterium transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G. , Dong, R. , Allen, R. , Davis, E.L. , Baum, T.J. and Hussey, R.S. (2006) A root‐knot nematode secretory peptide functions as a ligand for a plant transcription factor. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey, R.S. and Grundler, F.M.W. (1998) Nematode parasitism of plants In: The Physiology and Biochemistry of Free‐Living and Plant‐Parasitic Nematodes (Perry R.N. and Wright D.J., eds), pp. 213–243. Wallingford: CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey, R.S. , Davis, E.L. and Baum, T.J. (2002) Secrets in secretions: genes that control nematode parasitism of plants. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 14, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, H.M.M. , Alkaharouf, N.W. , Meyer, S.L.F. , Aly, M.A.M. , Gamal El‐Din, A.E.K.Y. , Hussein, E.H.A. and Matthews, B.F. (2011) Post‐transcriptional gene silencing of root‐knot nematode in transformed soybean roots. Exp. Parasitol. 127, 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmer, D.P. , Goverse, A. and Smant, G. (2003) Parasitic nematode interactions with mammals and plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41, 245–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, W.R. (1964) A rapid centrifugal‐flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Dis. Rep. 48, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.G. (1981) Host cell responses to endoparasitic nematode attack: structure and function of giant cells and syncytia. Ann. Appl. Biol. 97, 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C. and Wyss, U. (1999) New approaches to control plant parasitic nematodes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Klink, V.P. , Overall, C.C. , Alkharouf, N. , MacDonald, M.H. and Matthews, B.F. (2007) A comparative microarray analysis of an incompatible and compatible disease response by soybean (Glycine max) to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) infection. Planta, 226, 1423–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink, V.P. , Kim, K.H. , Martins, V. , MacDonald, M.H. , Beard, H.S. , Alkharouf, N.W. , Lee, S.K. , Park, S.C. and Matthews, B.F. (2009) A correlation between host‐mediated expression of parasite genes as tandem inverted repeats and abrogation of development of female Heterodera glycines cyst formation during infection of Glycine max . Planta, 230, 53–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenning, S.R. , Overstreet, C. , Noling, J.W. , Donald, P.A. , Becker, J.O. and Fortnum, B.A. (1999) Survey of crop losses in response to phytoparasitic nematodes in the United States for 1994. J. Nematol. 31 (4S), 587–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusberg, L.R. , Sardanelli, S. , Meyer, S.L.F. and Crowley, P. (1994) A method for recovery and counting of nematode cysts. J. Nematol. 26, 599. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault, M. , Thibivilliers, S. , Bilgin, D.D. , Radwan, O. , Benitez, M. , Clough, S.J. and Stacey, G. (2008) Identification of four soybean reference genes for gene expression normalization. Plant Genome, 1, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Libertini, E. , Li, Y. and McQueen‐Mason, S.J. (2004) Phylogenetic analysis of the plant endo‐1,4‐β‐glucanase gene family. J. Mol. Evol. 58, 506–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.C. , Lu, C.F. , Wu, J.W. , Cheng, M.L. , Lin, Y.M. , Yang, N.S. , Black, L. , Green, S.K. , Wang, J.F. and Cheng, C.P. (2004) Transgenic tomato plants expressing the Arabidopsis NPR1 gene display enhanced resistance to a spectrum of fungal and bacterial diseases. Transgenic Res. 13, 567–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. , Kandoth, P.K. , Warren, S.D. , Yeckel, G. , Heinz, R. , Aldel, J. , Yang, C. , Jamai, A. , El‐Mellouki, T. , Juvale, P.S. , Hill, J. , Baum, T.J. , Cianzio, S. , Whitham, S.A. , Korkin, D. , Mitchum, M.G. and Meksem, K. (2012) A soybean cyst nematode resistance gene points to a new mechanism of plant resistance to pathogens. Nature, 492, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi, B.M. , Boerma, H.R. and Hussey, R.S. (1994) A gene for resistance to the southern root‐knot nematode in soybean. J. Hered. 85, 484–486. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingan, R. and Skorupska, H.T. (1996) Cytological expression of early response to infection by Heterodera glycines, Ichinohe in resistant PI 437654 soybean. Genome, 39, 986–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson, A.L. and Williams, L.F. (1965) Evidence of fourth gene for resistance to the soybean cyst nematode. Crop Sci. 5, 477. [Google Scholar]

- Matsye, P.D. , Lawrence, G.W. , Youssef, R.M. , Kim, K.H. , Matthews, B.F. , Lawrence, K.S. and Klink, V.P. (2012) The expression of a naturally occurring, truncated allele of an α‐SNAP gene suppresses plant parasitic nematode infection. Plant Mol. Biol. 80, 131–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B.F. , Ibrahim, H.M.M. and Klink, V.P. (2011) Changes in the expression of genes in soybean roots infected by nematodes In: Soybean‐Genetics and Novel Techniques for Yield Enhancement (Krezhova D., ed.), pp. 77–96. Rijeka: InTech. [Google Scholar]

- Mazarei, M. , Lennon, K.A. , Puthoff, D.P. , Rodermel, S.R. and Baum, T.J. (2004) Homologous soybean and Arabidopsis genes share responsiveness to cyst nematode infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 409–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, J.M. and Woffenden, B.J. (2003) Plant disease resistance genes: recent insights and potential applications. Trends Biotechnol. 21, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchum, M.G. , Sukno, S. , Wang, X. , Shani, Z. , Tsabary, G. , Shoseyov, O. and Davis, E.L. (2004) The promoter of the Arabidopsis thaliana Cel1 endo‐1,4‐β‐glucanase gene is differentially expressed in plant feeding cells induced by root‐knot and cyst nematodes. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molhoj, M. , Pagant, S. and Hofte, H. (2002) Towards understanding the role of membrane‐bound endo‐β‐1,4‐glucanases in cellulose biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert, S. , Bichet, A. , Grandjean, O. , Kierzkowski, D. , Satiat‐Jeunemaître, B. , Pelletier, S. , Hauser, M.T. , Höfte, H. and Vernhettes, S. (2005) An Arabidopsis endo‐1,4‐β‐D‐glucanase involved in cellulose synthesis undergoes regulated intracellular cycling. Plant Cell, 17, 3378–3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.K.C. and Bennett, A.B. (1999) Cooperative disassembly of the cellulose–xyloglucan network of plant cell walls: parallels between cell expansion and fruit ripening. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, M.N. , Favery, B. , Piotte, C. , Arthaud, L. , De Boer, J.M. , Hussey, R.S. , Bakker, J. , Baum, T.J. and Abad, P. (1999) Isolation of a cDNA encoding a β‐1,4‐endoglucanase in the root‐knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and expression analysis during plant parasitism. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 12, 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben, E. , Jamai, A. , Afzal, J. , Njiti, V.N. , Triwitayakorn, K. , Iqbal, M.J. , Yaegashi, S. , Bashir, R. , Kazi, S. , Arelli, P. , Town, C.D. , Ishihara, H. , Meksem, K. and Lightfoot, D.A. (2006) Genomic analysis of the rhg1 locus: candidate genes that underlie soybean resistance to the cyst nematode. Mol. Genet. Genomics, 276, 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, I. , Abdelnoor, R.V. , Marin, S.R.R. , Carvalho, V.P. , Kiihl, R.A.S. , Silva, J.F.V. , Sediyama, C.S. , Barros, E.G. and Moreira, M.A. (2001) Identification of a new major QTL associated with resistance to soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines). Theor. Appl. Genet. 102, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S. and Wilk, M.B. (1965) Analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar]

- Sijmons, P.C. , Grundler, F.M.W. , von Mende, N. , Burrows, P.R. and Wyss, U. (1991) Arabidopsis thaliana as a new model host for plant‐parasitic nematodes. Plant J. 1, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Smant, G. , Stokkermans, J.P. and Yan, Y. (1998) Endogenous cellulases in animals: isolation of β‐1,4‐endoglucanase genes from two species of plant‐parasitic cyst nematodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 4906–4911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukno, S. , Shimerling, O. , McCuiston, J. , Tsabary, G. , Shani, Z. , Shoseyov, O. and Davis, E.L. (2006) Expression and regulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana Cel1 endo‐1,4‐β‐glucanase gene during compatible plant–nematode interactions. J. Nematol. 38, 354–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumit, R. , Sahu, B.B. , Xu, M. , Sandhu, D. and Bhattacharyya, M.K. (2012) Arabidopsis nonhost resistance gene PSS1 confers immunity against an oomycete and a fungal pathogen but not a bacterial pathogen that cause diseases in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M.L. , Burke, A. , Murphy, C.A. , Thai, V.K. and Ehrenfried, M.L. (2007) Gene expression profiles for cell wall‐modifying proteins associated with soybean cyst nematode infection, petiole abscission, root tips, flowers, apical buds, and leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3395–3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara, T. , Kushida, A. and Momota, Y. (2001) PCR‐based cloning of two β‐1,4‐endoglucanases from the root‐lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans . Nematology, 3, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Vanholme, B. , De Meutter, J. , Tytgat, T. , Van Montagu, M. , Coomans, A. and Gheysen, G. (2004) Secretions of plant‐parasitic nematode: a molecular update. Gene, 332, 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Meyers, D. , Yan, Y. , Baum, T. , Smant, G. , Hussey, R. and Davis, E. (1999) In planta localization of β‐1,4‐endoglucanase secreted by Heterodera glycines . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 12, 64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Mitchum, M.G. , Gao, B. , Li, C. , Diab, H. , Baum, T.J. , Hussey, R.S. and Davis, E.L. (2005) A parasitism gene from a plant‐parasitic nematode with function similar to CLAVATA3/ESR (CLE) of Arabidopsis thaliana . Mol. Plant Pathol. 6, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Replogle, A. , Davis, E.L. and Mitchum, M.G. (2007) The tobacco Cel7 gene promoter is auxin‐responsive and locally induced in nematode feeding sites of heterologous plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Dai, L. , Jiang, Z. , Peng, W. , Zhang, L. , Wang, G. and Xie, D. (2005) GmCOI1, a soybean F‐box protein gene, shows ability to mediate jasmonate‐regulated plant defense and fertility in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 18, 1285–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, K. , Hofmann, J. , Blöchl, A. , Szakasits, D. , Bohlmann, H. and Grundler, F.M. (2008) Arabidopsis endo‐1,4‐β‐glucanases are involved in the formation of root syncytia induced by Heterodera schachtii . Plant J. 53, 336–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V.M. (1999) Plant nematode resistance genes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V.M. and Gleason, C.A. (2003) Plant–nematode interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V.M. and Hussey, R.S. (1996) Nematode pathogenesis and resistance in plants. Plant Cell, 8, 1735–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrather, J.A. and Koenning, S.R. (2006) Estimates of disease effects on soybean yields in the United States 2003–2005. J. Nematol. 38, 173–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrather, J.A. and Koenning, S.R. (2009) Estimates of disease effects on soybean yields in the United States 1996 to 2007. Plant Manage. Netw . Retrieved September 1, 2013 from http://www.plantmanagementnetwork.org/pub/php/research/2009/yields/. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y. , Smant, G. and Davis, E. (2001) Functional screening yields new β‐1,4‐endoglucanase gene from Heterodera glycines that may be the product of recent gene duplication. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, R.M. , MacDonald, M.H. , Brewer, E.P. , Bauchan, G.R. , Kim, K.H. and Matthews, B.F. (2013) Ectopic expression of AtPAD4 broadens resistance of soybean to soybean cyst and root‐knot nematodes. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N. , Tootle, T.L. , Tsui, F. , Klessig, F. and Glazebrooka, J. (1998) PAD4 functions upstream from salicylic acid to control defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 10, 1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of AtCel2 (At1g02800.1) and its soybean homologue GmCel7 (Gm02g01990.1). GmCel7 shares 75% identity and 91% similarity with AtCel2. Sequences were aligned with the clustalw program. Dashes indicate gaps in the amino acid sequences used to optimize alignment. Regions of identical (dark grey shade, asterisks) and similar (light grey shade, dots) amino acids are indicated. Underlining identifies the GHF9 gene motif.

Fig. S2 Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of AtKOR3 (At4g24260.1) and its soybean homologue GmKOR3 (Gm17g00710.1). GmKOR3 shares 73% identity and 89% similarity with AtKOR3. Sequences were aligned with the clustalw program. Dashes indicate gaps in the amino acid sequences used to optimize alignment. Regions of identical (dark grey shade, asterisks) and similar (light grey shade, dots) amino acids are indicated. Underlining identifies the GHF9 gene motif.

Fig. S3 Expression level of GmKOR3 gene of transformed soybean roots with pRAP17‐GmKOR3. Each total RNA from the empty pRAP17 control and transformed soybean roots with pRAP17‐GmKOR3 was extracted at 0 days after soybean cyst nematode (SCN) inoculation (before inoculation) and at 10 days after inoculation (dai), respectively. GmKOR3 gene expression was measured as the copy number of the transcripts normalized by the copy number of the reference gene (cons7) through real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction analysis. The white bar represents the mean of the relative GmKOR3 gene expression level of pRAP17‐GmKOR3 transformed individual plants (n = 5) compared with empty pRAP17 controls (black bar, n = 5), with the standard errors of the mean noted. The asterisks (**) denote the mean value significantly different from the empty pRAP17 control as determined by PROC TTEST (P < 0.01).