SUMMARY

Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc) is an economically important pathogen of carrots. Its ability to epiphytically colonize foliar surfaces and infect seeds can result in bacterial blight of carrots when grown in warm and humid regions. We used high‐throughput sequencing to determine the genome sequence of isolate M081 of Xhc. The short reads were de novo assembled and the resulting contigs were ordered using a syntenic reference genome sequence from X. campestris pv. campestris ATCC 33913. The improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xhc M081 is the first for its species. Despite its distance from other sequenced xanthomonads, Xhc M081 still shared a large inventory of orthologous genes, including many clusters of virulence genes common to other foliar pathogenic species of Xanthomonas. We also mined the genome sequence and identified at least 21 candidate type III effector genes. Two were members of the avrBs2 and xopQ families that demonstrably elicit effector‐triggered immunity. We showed that expression in planta of these two type III effectors from Xhc M081 was sufficient to elicit resistance gene‐mediated hypersensitive responses in heterologous plants, indicating a possibility for resistance gene‐mediated control of Xhc. Finally, we identified regions unique to the Xhc M081 genome sequence, and demonstrated their potential in the design of molecular diagnostics for this pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Xanthomonads are a diverse group of Gram‐negative γ‐proteobacteria. Members of xanthomonads are successful pathogens capable of infecting many agriculturally important crop plants. Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc; synonyms X. campestris pv. carotae, X. carotae; CABI, 2010) causes bacterial leaf blight of carrot, an important disease in most regions of the world. Like most other members of the Xanthomonas genus, Xhc has the ability to epiphytically colonize foliar surfaces of its host. Xhc is also pathogenic and, when weather conditions are sufficiently warm and humid, Xhc can incite foliar disease, which can result in defoliation of host plants with a consequential loss of yield.

Several Xanthomonas isolates belonging to just a few of the many species of this genera have completed genome sequences, including X. campestris pv. campestris (Xcc), X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv; syn. X. vesicatoria, X. axonopodis pv. vesicatoria), X. axonopodis pv. citri (Xac; syn. X. citri pv. citri) and X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo; Salzberg et al., 2008; da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005). Comparisons indicate that most isolates share a high percentage of orthologous genes and long‐range synteny (Blom et al., 2009; da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005). Xoo isolates have similar numbers of genes, but are exceptional in their genome organization. Indeed, Xoo genomes contain the largest number of insertion element families compared with all other sequenced xanthomonads, and have undergone significant numbers of large‐scale rearrangements (Salzberg et al., 2008).

Xanthomonas hortorum is one of the many less‐characterized species within the Xanthomonas genus. Xanthomonas hortorum was initially defined on the basis of DNA hybridization studies (Vauterin et al., 1995). Subsequent phylogenetic and multilocus sequence analyses using gyrB or four housekeeping genes, respectively, confirmed that its isolates represent a distinct species and, furthermore, grouped X. hortorum with X. cynarae and X. gardneri to form a diverse clade (2007, 2009; Young et al., 2008). The determination of the genome sequences for its members will thus be an important contribution to understanding the diversity and evolution of the Xanthomonas genus, and help to resolve this heterogeneous clade.

The process by which Xhc infects its host plant is presumed to be similar to that of other foliar pathogens of Xanthomonas. Xanthomonads typically gain access to their hosts through natural openings and wounds to colonize and proliferate in the intercellular spaces. Pathogenesis by most xanthomonads is dependent on a type III secretion system (T3SS), a molecular injection apparatus that delivers bacterially encoded proteins directly into host cells (Buttner and Bonas, 2010). Once inside the host cell, these so‐called type III effector (T3E) proteins function to perturb host processes, such as pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP)‐triggered immunity (PTI; Jones and Dangl, 2006).

T3Es also have the potential to elicit plant defences. In effector‐triggered immunity (ETI), direct or indirect perception of a single T3E by a corresponding plant resistance (R) protein results in a robust resistance response (Jones and Dangl, 2006). A classic hallmark of ETI is the hypersensitive response (HR), which is visualized as a rapid and localized cell death of the infected area (Greenberg and Yao, 2004). Therefore, T3Es are collectively necessary for many Gram‐negative pathogens to infect host plants, but just a single T3E can limit the host range of a pathogen through its perception by a corresponding host R protein.

The production of commercial carrot crops depends greatly on planting seeds with zero or low contamination of Xhc. The semi‐arid climates in which carrot seeds are produced permit the epiphytic growth of Xhc (du Toit et al., 2005). The bacteria associated with seeds provide the inoculum for bacterial blight when carrots are grown in warm and humid regions. Once the pathogen is established in a crop, the suppression of bacterial blight with bactericides is difficult. Sensitive, specific and facile methods are therefore needed to detect Xhc in seed lots (Meng et al., 2004). The development of cost‐effective management methods against Xhc is also greatly desired (du Toit et al., 2005). A sequenced genome can be an important resource for these purposes and has been used in the development of molecular markers to distinguish between two important Xanthomonas rice pathogens (Lang et al., 2010).

We present an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of the M081 isolate of Xhc. Xhc M081 is distinct from other sequenced isolates of Xanthomonas but, despite the degree of phylogenetic distance from other xanthomonads, Xhc M081 shares many orthologous genes and shows high synteny to Xcc, Xac and Xcv. We characterized the genome of Xhc to gain insight into its mechanisms of pathogenesis. We describe potential virulence genes and provide evidence that Xhc M081 encodes two members of the ETI‐eliciting AvrBs2 and XopQ T3E families (Kearney and Staskawicz, 1990; Wei et al., 2007). These two T3Es are therefore potential targets for the development of control measures against Xhc in carrot. Finally, we identified several regions unique to Xhc, and designed and validated several pairs of primers that specifically amplified products from Xhc but not other tested bacteria. These regions have potential use in the design of molecular diagnostics for Xhc.

RESULTS

Isolation and preliminary typing of Xhc M081

Bacteria were isolated from diseased carrot plants (Daucus carota L.) grown in a seed production field located near Madras, OR, USA. We used several phenotypic and molecular markers to preliminarily type M081. This isolate was selected on the basis of its ability to grow on XCS medium, which is semi‐selective for Xhc (Williford and Schaad, 1984). The colony morphology of M081 grown on yeast–dextrose–calcium carbonate (YDC) medium was also suggestive of it belonging to the Xanthomonas genus (data not shown; Schaad and Stall, 1988). The 16‐23S intergenic spacer region and the elongation factor α‐encoding gene of M081 had the highest similarity to that of Xcc type strain ATCC 33913. In addition, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of M081 with the 3S and 9B primer sets resulted in products that were consistent in size to other isolates of Xhc (Meng et al., 2004; Temple and Johnson, 2009). Finally, and most importantly, we were able to show that M081 could achieve large epiphytic populations [>107 colony‐forming units (cfu)/g leaf tissue] and cause symptoms consistent with bacterial blight of carrots in glasshouse and growth chamber experiments (data not shown). We therefore classified isolate M081 as a member of X. hortorum, which was later substantiated by phylogenetic analysis (see below).

Sequencing and assembly of an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence

We used an Illumina IIG to sequence the genome of Xhc and generated nearly 30 million paired‐end (PE) reads, approximately 19.1 million and 10.4 million of which were 32mer and 70mer pairs, respectively. The theoretical coverage of all filtered PE reads was estimated to be 525×, assuming that Xhc M081 had a genome size of 5.1 megabases (Mb). We elected to use a de novo approach to assemble the PE reads because of our desire to identify unique regions. We also lacked any data that could direct us to a suitable reference genome for a guided approach to assemble the short reads; previous phylogenetic analyses placed Xhc in a clade separate from other Xanthomonas species with sequenced isolates (Parkinson et al., 2009; Young et al., 2008).

We sought to develop an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence for Xhc. This standard requires the use of additional work to eliminate discernible misassemblies and resolve gaps, and is sufficient for the assessment of genomes for gene content and comparisons with other genomes (Chain et al., 2009). To this end, we used the software program Velvet version 0.7.55 and a variety of parameter settings to de novo assemble the PE reads, and generated a total of approximately 30 different assemblies (Zerbino and Birney, 2008). We identified a single high‐quality de novo assembly based on consensus support. In other words, we had greater confidence in the quality of this particular assembly because the majority of its contigs were supported by contigs of other assemblies derived using different Velvet parameter settings (Kimbrel et al., 2010). The one high‐quality assembly we selected was derived from approximately 20 million PE reads with an actual coverage of approximately 110× and had 153 contigs larger than one kilobase (kb) for a sum total of 5.06 Mb. The average contig size was approximately 32 kb, the largest contig was 232 kb and the N50 was 26 contigs; one‐half of the genome was represented by the 26 largest contigs.

Comparative and phylogenomic analyses

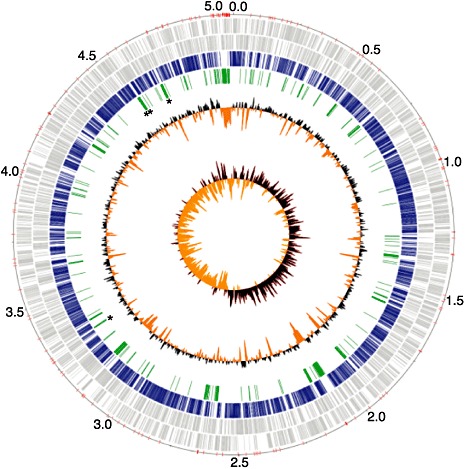

We compared the contigs from Xhc M081 with completed genome sequences from representative isolates of Xanthomonas to search for a genome sequence with sufficient structural similarities to use as a reference for the ordering of contigs (Salzberg et al., 2008; da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005). Our preliminary analysis indicated that the contigs of Xhc M081 had sufficient within synteny to the genome of Xcc ATCC 33913, and it was therefore used to order all contigs of Xhc M081 larger than 1 kb. The resulting assembly was deemed an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence (Chain et al., 2009). The genome is depicted as a single circular chromosome with physical gaps depicted by red tick marks (Fig. 1). We found no evidence for plasmids in Xhc M081, which, thus far, have only been found in Xac and Xcv (da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Circular representation of the improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc) M081. Circle 1 (outer) designates the coordinates of the genome in half million base pair increments (red tick marks denote contig breaks); circles 2 and 3 show predicted coding sequences (CDSs) as grey lines on the positive and negative strands, respectively; circle 4 shows CDSs with homology to at least one other gene in other xanthomonads (e‐value <1 × 10−7); circle 5 shows regions of Xhc M081 larger than 1 kb with no detectable homology to genomes of other xanthomonads; asterisks highlight the locations for the Xhc‐specific primer sets XhcPP02 (between genome coordinates 3.0–3.5) and XhcPP03–XhcPP05 (in numerical order starting near genome coordinate 4.5; see also 2, 5 and Fig. 4); circle 6 shows deviations from the average GC percentage of 63.7% (black, greater; orange, smaller); circle 7 shows GC skew with bias for and against guanine as black and orange, respectively.

The genome of Xhc M081 shares several characteristics with genomes of other representative foliar pathogenic isolates of Xanthomonas (Table 1). Xhc M081 has a high GC content of 63.7% and the size of its genome was within the range of other sequenced genomes of isolates of Xanthomonas (Table 1). We used an automated approach to identify and annotate 4493 coding sequences (CDSs), resulting in a genome coding percentage of 87.4% (Giovannoni et al., 2008; Kimbrel et al., 2010). Given the similarities of the last two characteristics to other Xanthomonas genomes, we are confident that the majority of the Xhc M081 genome is present in the assembly and our automated annotation approach is acceptable.

Table 1.

Comparison of Xanthomonas genome characteristics.

| Isolate* | Xhc † | Xcc | Xcv | Xac | Xoo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (Mb) | 5.062 | 5.076 | 5.178 | 5.176 | 5.240 |

| GC (%) | 63.7 | 65.1 | 64.7 | 64.8 | 63.6 |

| No. CDSs | 4493 | 4179 | 4487 | 4312 | 4988 |

| Average length of CDSs (bp) | 985 | 1032 | 1005 | 1032 | 856 |

| Coding (%) | 87.4 | 84.9 | 87.4 | 86.2 | 81.8 |

CDS, coding sequence; Xac, X. axonopodis pv. citri; Xcc, X. campestris pv. campestris; Xcv, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria; Xhc, Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae; Xoo, X. oryzae pv. oryzae.

See Table 4.

Based on improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence.

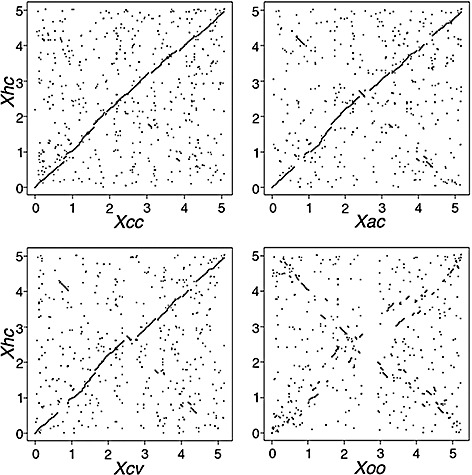

With the exception of Xoo, genomes of the foliar pathogenic xanthomonads share long‐range synteny (Blom et al., 2009; da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005). To determine whether Xhc M081 had similar syntenic relationships, we parsed the genome sequences of Xcc, Xac, Xcv and Xoo into all possible 25mer DNA sequences and aligned the unique 25mers to the genome sequence of Xhc M081 (Fig. 2). Our results confirmed our initial findings by showing the greatest synteny to the genome of Xcc. The genome of Xhc M081 was also syntenic to the genomes of Xac and Xcv, with the exception of a few large insertion–deletions (indels) and inversion events that appeared to be localized to the predicted terminator sequence (data not shown). Similar to others, the genome of Xhc showed little structural similarity to the genome of Xoo.

Figure 2.

Synteny plots comparing the genome structure of Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc) M081 with the genomes of other Xanthomonas species. Unique 25mers from X. campestris pv. campestris (Xcc), X. axonopodis pv. citri (Xac), X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv) and X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) were compared with the improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xhc M081. The start positions of all matching pairs were plotted in an xy graph with the coordinates of the genome of Xhc M081 along the y‐axis and the coordinates of the genomes of Xcc, Xac, Xcv and Xoo along the x‐axis (see Table 4). The termini are located at the approximate mid‐way point for each comparison. Genome scales are shown in 1‐Mb increments.

The Xhc M081 genome encodes a high percentage of proteins orthologous to proteins of other species of Xanthomonas. Reciprocal best hit analysis using blastp showed that 74.2%, 73.8%, 72.9% and 61.1% of the proteins encoded by Xhc M081 were also found in Xcc, Xac, Xcv and Xoo, respectively. The greater than 70% orthology was similar to levels observed in previous comparisons between different Xanthomonas species (Blom et al., 2009; da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005). The smaller amount of orthology to Xoo was not surprising, considering that Xoo appears to be the most distinct of the sequenced foliar pathogenic isolates.

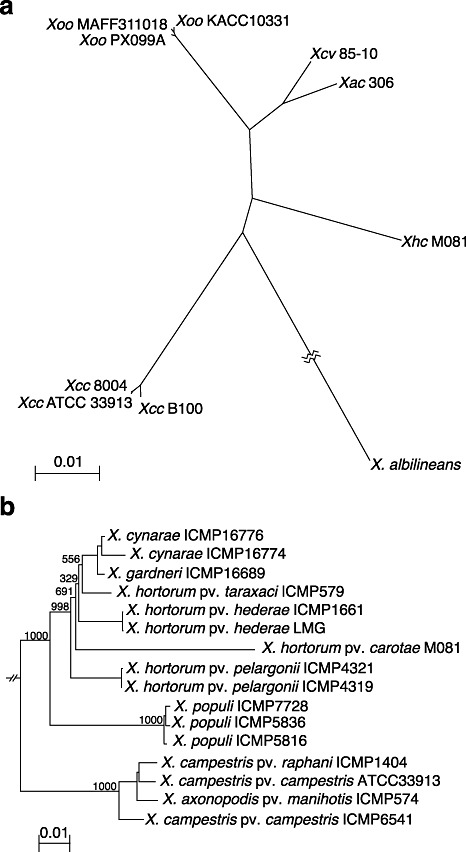

We used two approaches to examine the relationship of Xhc M081 to other xanthomonads. In the first, we used a phylogenomic approach to determine the species' relationship of Xhc M081 to representative isolates of Xanthomonas with completed genome sequences. We identified a core of 1776 translated sequences common to the 10 examined isolates and produced a species' tree based on the comparison of a superalignment from their sequences (Fig. 3a). Each of the previously sequenced species grouped as expected, with Xhc M081 forming a branch by itself. We used multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) to examine the relatedness of Xhc M081 to other isolates of X. hortorum[Fig. 3b; complete tree is provided as Fig. S1 (see Supporting Information); Young et al., 2008]. Xhc M081 grouped with other pathovars of X. hortorum within the heterogeneous clade that also includes X. cynarae and X. gardneri isolates (Young et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Isolate M081 groups with Xanthomonas hortorum. (a) Unrooted phylogenomic tree of 10 Xanthomonas isolates based on a superalignment of 1776 translated sequences. Abbreviations are as described in the text and accession numbers are presented in Table 4. Bootstrap support values for nodes (r= 1000) were all 100. The branch length for X. albilineans was 0.232. Xac, X. axonopodis pv. citri; Xcc, X. campestris pv. campestris; Xcv, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria; Xhc, Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae; Xoo, X. oryzae pv. oryzae. (b) Neighbour‐joining tree of concatenated nucleotide sequences for partial dnaK, fyuA, gyrB and rpoD genes from Xanthomonas strains. A portion of the tree is presented, focusing on the X. hortorum–cynarae–garnderi group. Numbers indicate bootstrap support (r= 1000). The scale bars indicate the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Candidate virulence genes of Xhc M081

We identified several clusters of virulence genes important for pathogenesis by xanthomonads. Xanthan is an exopolysaccharide produced by xanthomonads with important roles in biofilm formation and pathogenesis (Katzen et al., 1998). Synthesis is dependent on a cluster of 12 gum genes, gumB–gumM. We identified a similarly arranged cluster present on a single contig in Xhc M081 (XHC_2807 to XHC_2795), flanked by homologues of gumN–gumP on one side and a tRNA‐encoding gene on the other. The presence of the tRNA‐encoding gene has been implicated as evidence for the acquisition of this gene cluster by horizontal gene transfer (Lu et al., 2008). We did not find any evidence of insertion sequences in this cluster.

The rpf (regulation of pathogenicity factors) cluster of genes encodes positive regulators of extracellular enzymes and proteins that synthesize and perceive an intracellular diffusible factor (DSF) cis‐11‐methyl‐2‐dodecenoic acid, important for virulence (Wang et al., 2004). Four genes are demonstrably important; RpfB and RpfF are involved in the biosynthesis of DSF, whereas RpfG and RpfC are hypothesized to perceive DSF. Xcc mutants of rpfF and rpfC, for example, are compromised in the manipulation of plant stomatal closure, an important step during infection (Gudesblat et al., 2009). Xhc M081 encodes a cluster of approximately 23 kb with eight genes homologous to rpf genes, including rpfB, rpfF, rpfG and rpfC that were all present on one contig.

Other examples of homologous virulence genes included the four‐gene operon of hmsHFRS which encodes haemin storage systems involved in biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis (Abu Khweek et al., 2010). Xhc M081 contains homologues of wzm and wzt involved in the synthesis of lipopolysaccharides (Rocchetta and Lam, 1997). However, like X. fuscans ssp. aurantifolii types B and C, the wzt gene of Xhc M081 appears to encode a C‐terminal truncated protein, which is predicted to be affected in substrate binding (Cuthbertson et al., 2005; Moreira et al., 2010). Xhc M081 encodes a homologue of yapH, a plant adhesion protein, hlyD and hlyB genes for haemolysin secretion and a homologue of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa asnB gene, involved in asparagine and O‐antigen biosynthesis (Augustin et al., 2007; Das et al., 2009; Holland et al., 2005).

The type IV secretion system (T4SS) is an apparatus used by many bacteria to interact with their hosts (Alvarez‐Martinez and Christie, 2009). Clusters of T4SS‐encoding genes have been identified in genome sequences of xanthomonads, but the role of T4SS in the virulence of xanthomonads is still unclear (da Silva et al., 2002). Xhc M081 appears to encode for a T4SS (XHC_2815‐XHC_2830), but it was difficult for us to determine whether the T4SS is functional because the cluster of genes was distributed across three separate and adjoining contigs with physical gaps that corresponded to what appears to be three different copies of virB4. Whether the three copies are bona fide or an artefact of misassembly is unresolved. The three contigs that encode T4SS were approximately 10 kb away from the gum cluster. In the genome of Xcc ATCC 33913, which was used as a reference to order the contigs of Xhc M081, these two gene clusters are nearly 26 kb apart (da Silva et al., 2002).

T3SS is another apparatus used by many Gram‐negative pathogens to interact with their hosts. In plant pathogens, T3SS is required for pathogenesis and is encoded by a single cluster of genes, called hrp genes (Lindgren et al., 1986; Niepold et al., 1985). All hrp genes of Xhc M081 (CDSs XHC_1407 to XHC_1426), except for hrcC, were found in their entirety and were clustered on a single contig of 25 kb in length. We used PCR and sequencing of the product to complete the ∼50 nucleotides of the C‐terminal coding portion of the hrcC CDS and join the T3SS‐encoding contig with its neighbouring contig. The organization of the hrp cluster in Xhc was identical to that of the corresponding hrp genes of other Xanthomonas foliar pathogens. In addition, we did not identify any polymorphisms in CDSs that would overtly affect function (data not shown). T3SS of Xhc is consequently predicted to be complete and functional.

We mined the Xhc M081 genome sequence for candidate T3E genes. In Xanthomonas and Ralstonia spp., T3E genes are often preceded by a cis regulatory motif recognized by the transcriptional regulator HrpX (Koebnik et al., 2006; Mukaihara et al., 2004). We identified 118 putative Plant‐Inducible‐Promoter boxes (PIP‐boxes) in the genome of Xhc M081. Of these 118, only 38 had a CDS within 300 bp of a putative PIP‐box. We further eliminated 26 CDSs because their translated sequences were homologous to proteins with functions atypical of T3Es. We also used blastp searches to find 10 more CDSs with translated sequences homologous to known T3Es (Table 2).

Table 2.

Candidate type III effectors of Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc) M081.

| Gene* | e‐value† | Name/function | Distance from PIP‐box (bp)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0064 | 0.0 | avrBs2 | 64 |

| 0287 | 6 × 10−62 | xopR | 63 |

| 0288§ | 1 × 10−21 | xopR | 76 |

| 0818 | 0.0 | xopAG | Not found |

| 1217 | 0.0 | xopQ | 74 |

| 1402 | 0.0 | xopF1 | 863 |

| 1403 | 7 × 10−107 | xopZ | Not found |

| 1405 | 2 × 10−119 | hrpW ¶ | Not found |

| 1411 | 1 × 10−68 | hpaA | Not found |

| 1431 | 0.0 | xopX | Not found |

| 1432 | 0.0 | xopX | Not found |

| 4256/4257** | 0.0 | xopAD | Not found |

| 4368 | 8 × 10−22 | xopAE/hpaF | 41 |

| 4426 | 1 × 10−21 | avrXccA1 | Not found |

| 4439 | 2 × 10−72 | xopT | Not found |

| 0140 | n/a | Hypothetical | 34 |

| 0803 | n/a | Hypothetical | 472 |

| 1218 | n/a | Hypothetical | 70 |

| 2239§ | n/a | Hypothetical | 151 |

| 2558 | n/a | Hypothetical | 68 |

| 3774 | n/a | Hypothetical | 166 |

| 4437§ | n/a | Hypothetical | 204 |

n/a, not applicable.

Coding sequence (CDS) identifier number.

blastx.

Distance of predicted start codon from the 3′ end of the Plant‐Inducible‐Promoter box (PIP‐box).

Unique to Xhc M081.

Helper protein secreted by type III secretion system (T3SS).

Potential pseudogene (see corresponding text).

Three of the candidate T3E genes required additional characterizations because of evidence for potential assembly artefacts. Two CDSs, both with homology to xopX, were found in tandem in one contig. The translated sequences of the xopX homologues were 61% identical (77% similar) to each other, and the genes have a similar arrangement in Xcc ATCC 33913, suggesting that this was not an artefact of short‐read assembly (White et al., 2009). Nonetheless, we used PCR of Xhc M081 genomic DNA and sequencing of the product to confirm the presence of tandem copies of xopX. Similarly, we found two CDSs with homology to xopR in tandem on a contig. One of the CDSs appeared to be full length relative to xopR of Xcc ATCC 33913. The other CDS had weaker homology to xopR and was shorter. Both xopR homologues, however, had putative PIP‐boxes less than 100 bp upstream of their predicted start codons, suggesting the two to be separate candidate T3E genes. We again confirmed this arrangement using PCR and sequencing of the amplified product (data not shown). Finally, xopAD was found on more than one contig. We speculate that the repeats, approximately 126 bp in length, were difficult to assemble. The repeats also made it difficult to design specific primers for PCR and gap closure. Therefore, we were unable to determine whether xopADXhc encodes a full‐length product, or is a pseudogene similar to xopAD of Xcv (White et al., 2009). Not including xopAD, Xhc encodes at least 21 candidate T3Es with three unique to Xhc M081.

Two of the candidate T3E genes of Xhc M081 are highly homologous to demonstrable ETI‐eliciting T3Es. AvrBs2 (88% identity) was first characterized in Xcv and is very widespread on the basis of a survey of various races of Xcv and other pathovars of X. campestris (Kearney and Staskawicz, 1990). Given the prevalence of avrBs2 in Xanthomonas spp., it was not at all surprising that at least 10 kb of DNA sequence flanking either side of this T3E gene in Xhc M081 was also conserved in Xcc, Xcv, Xac and Xoo. Furthermore, the regions surrounding and including avrBs2 had a GC percentage that was not significantly different from the genome average of 63.7%. This observation suggests that avrBs2 was probably present in an ancestor common to the foliar pathogenic species of Xanthomonas.

XopQ (92% identical) is also prevalent in xanthomonads. XopQ is a member of the HopQ1‐1 family of T3Es first discovered in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Chang et al., 2005; Guttman et al., 2002; Petnicki‐Ocwieja et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2007). In contrast with avrBs2Xhc, comparisons of the 5 kb of DNA sequences flanking xopQ of Xhc M081 showed a variable pattern that was difficult to interpret. We also noted that xopQ resides in a 20‐kb region with an average GC content of 55%, a large deviation from the Xhc M081 genome average of 63.7%. Finally, the CDS just upstream of xopQXhc encodes an IS4 family transposase, the presence of which appears to be unique to Xhc M081. In total, these data suggest that the different foliar pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. examined may have acquired xopQ independently after they diverged from their common ancestor.

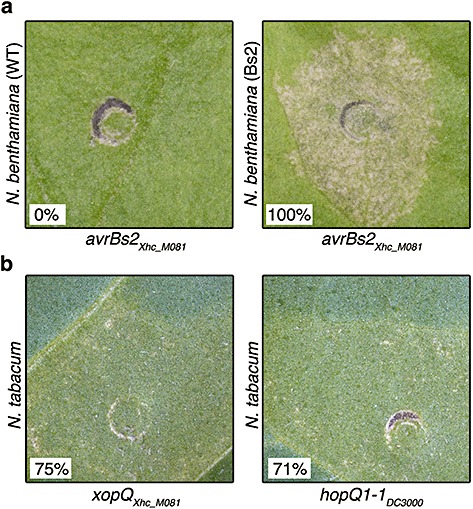

We determined whether AvrBs2Xhc and XopQXhc could elicit HR in plants. The R gene corresponding to avrBs2 has been cloned (Tai et al., 1999). Bs2 encodes nucleotide‐binding and leucine‐rich repeat motifs typical of many R proteins and Bs2 is sufficient to elicit an HR in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana plants when co‐expressed with avrBs2 (Tai et al., 1999). HopQ1‐1 elicits an HR in wild‐type N. benthamiana as well as N. tabacum. The R gene corresponding to hopQ1‐1 has yet to be identified, but nevertheless could provide another opportunity for potential control against Xhc.

Neither of the R genes has been identified in carrot, and so we elected to use tobacco and Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transient expression to test for the elicitation of HR. Agrobacterium carrying a cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S‐expressing avrBs2 from Xhc M081 caused a rapid HR 24 h post‐infiltration (hpi) in transgenic N. benthamiana constitutively expressing Bs2 (Fig. 4; Tai et al., 1999). In contrast, no phenotypes were visible in wild‐type N. benthamiana lacking Bs2 following infiltration with Agrobacterium carrying the same DNA construct. Transient expression of CaMV 35S‐expressing xopQ and hopQ1‐1 cloned from P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 also resulted in strong, rapid HRs in 75% and 71%, respectively, of infiltrated leaves of wild‐type N. tabacum. No phenotypes were observed following challenge of tobacco plants with Agrobacterium lacking T3E genes (data not shown). These results suggest that avrBs2Xhc and xopQXhc are sufficiently similar to their original founding family members for their translated products to be perceived by a corresponding R protein and elicit ETI. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that HopQ1‐1 and XopQ are perceived by two different R proteins of tobacco, although both appeared to elicit ETI in an age‐dependent manner, with more robust HRs in older leaves.

Figure 4.

AvrBs2Xhc and XopQXhc elicit a hypersensitive response in tobacco plants. Plants were challenged with optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 1.0 of Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying avrBs2, xopQ or hopQ1‐1 under the regulation of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. (a) Wild‐type and transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana, expressing Bs2, were challenged with A. tumefaciens carrying avrBs2 (Tai et al., 1999). (b) Wild‐type N. tabacum was challenged with A. tumefaciens carrying xopQ or hopQ1‐1. Twenty‐four leaf panels were infiltrated per experiment and experiments were repeated three times with identical results (percentages with a response are shown). Plant responses were scored 24 h post‐infection.

Development of molecular markers for Xhc

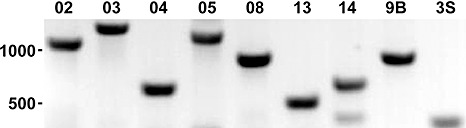

As an important step towards the development of molecular markers for the diagnosis of Xhc contamination in lots of carrot seeds, we searched the Xhc M081 genome for unique regions based on comparisons with genomes of other Xanthomonas species. Over 500 kb of sequences distributed over 171 different regions larger than 1 kb were identified (Fig. 1, track 5). We focused our efforts on 16 regions based on the criteria of size, location in the genome relative to each other, and uniqueness to Xhc based on blastn results to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database. Using these 16 regions as templates, we designed 18 different primer pairs (XhcPP =Xhc Primer Pair). We used PCR of genomic DNA from Xhc M081 as a template to test these primers. Seven pairs led to amplifications of products of the expected size (Fig. 5). PCR with XhcPP05 resulted in a second fragment, but it appeared to amplify with far less efficiency and was larger in size than the expected product (not shown). PCR with XhcPP14 also resulted in a less abundant second product that was smaller in size.

Figure 5.

A panel of molecular markers specific to Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc). An inverse image of a 1 × Tris‐Acetate EDTA (TAE) agarose gel showing amplified products from genomic DNA extracted from Xhc M081. The primer pairs used are shown along the top. Their expected fragment lengths were 1041, 1266, 620, 1119, 875, 517, 651, 900 and 300 bp, respectively. Primer pairs 9B and 3S are from Meng et al. (2004). The 500 and 1000 base markers from the 100‐bp DNA ladder (NEB, Quick‐Load) are shown.

We tested the seven primer pairs in PCR with genomic DNA from Xhc isolates found in four world‐wide regions that produce carrot seeds to determine whether the primer pairs are broadly applicable for Xhc (Table 3). PCR with primer pairs XhcPP08, XhcPP13 and XhcPP14 yielded different sized products or failed to amplify a fragment from all tested Xhc seed isolates. In contrast, PCR with primer pairs XhcPP02, XhcPP03, XhcPP04 and XhcPP05 amplified a fragment of the expected size from all tested Xhc seed isolates (see also Fig. 1; asterisks track 5).

Table 3.

Evaluation of oligonucleotide primers for specific detection of Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc).

| Strain | Primer pair (XhcPP)* | Primer pair* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 08 | 13 | 14 | 9B‡ | 3S‡ | LAMP§ | |

| Xhc M081 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Xhc PNW1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Xhc PNW2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Xhc Fr1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Xhc Ar1 | + | + | + | + | +† | − | + | + | + | + |

| Xhc Ch1 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Xhc Ch2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Xhc Ch3 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Xcc ATCC 33913 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Xcv MTV1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Xccor ID‐A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| Xhh ATCC 9653 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

LAMP, loop‐mediated isothermal polymerase chain reaction; Xcc, X. campestris pv. campestris; Xccor, X. campestris pv. coriander; Xcv, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria; Xhh, X. hortorum pv. hederae.

+, Primer pair yielded a product of the expected size (see Fig. 4); −, primer pair failed to yield a product.

Product was not of the expected size (1.2 kb).

We also tested the seven primer pairs, or a subset of them, against available type strains, related strains and 23 isolates of bacteria from 14 genera that are commonly associated with plant surfaces. None of the seven tested pairs amplified a fragment from genomic DNA extracted from Xcc ATCC 33913, Xcv MTV1, X. campestris pv. coriander ID‐A (Xccor ID‐A) or X. hortorum pv. hederae (Xhh) ATCC 9653 (Table 3). We noted a very faint band of approximately 600 bp with XhcPP03 when tested with DNA from Xhh. The inability of our primer pairs to amplify products from Xccor ID‐A was encouraging because the 3S and 9B primer pairs could not distinguish between Xccor ID‐A and isolates of Xhc (Meng et al., 2009; Poplawsky et al., 2004). PCR with XhcPP02, XhcPP03, XhcPP04 and XhcPP05 failed to yield a single product of the expected size from any of the 23 bacterial isolates associated with plant surfaces (Table S1, see Supporting Information). Reactions with XhcPP04 resulted in multiple, faint and nonspecific amplified products from many of the tested isolates. Therefore, amongst the bacteria tested, the primer pairs XhcPP02, XhcPP03, XhcPP04 and XhcPP05 appeared to be specific to Xhc.

We performed post hoc analysis to determine whether regions to which XhcPP02–XhcPP05 annealed corresponded to any CDSs. One of the XhcPP02 primers annealed to XHC_2981 (TetR regulator) and the other annealed to an intergenic region. Genes homologous to XHC_2981 are present in other soil bacteria, but none were detected in genomes of xanthomonads. XhcPP03 annealed to XHC_4113 and XHC_4114 (both are annotated as ‘hypothetical’). Homologues are present in other xanthomonads but, unlike Xhc M081, are not clustered and not within an amplifiable distance. XhcPP04 annealed to XHC_4117 (membrane fusion protein). Here, too, homologues are present in other xanthomonads, but we observed very little nucleotide homology. Finally, XhcPP05 annealed to XHC_4175 (‘hypothetical’), which is unique to Xhc M081, and XHC_4176 (patatin‐like protein). The genomic regions corresponding to these four primer pairs are thus strong candidates for use in the development of molecular diagnostic tools for the detection of contamination of Xhc on carrot seeds, irrespective of the global regions in which the seeds are produced.

DISCUSSION

The semi‐arid climate of the Pacific Northwest region of the USA and Canada is ideal for carrot seed production. In this region, epiphytic populations of Xhc on umbels can infect developing seeds without eliciting foliar disease. As a consequence, Xhc can be unknowingly abundant on seeds harvested from production fields, which then serves as the inoculum for bacterial blight on carrots grown in other regions more conducive for disease development (du Toit et al., 2005). The asymptomatic ‘epidemic’ of epiphytic colonization of the seed crops frequently necessitates hot water treatment of seed lots to reduce the seed‐borne populations of Xhc. Hot water treatment, however, is expensive and potentially injurious to seeds.

The diagnosis of seed lots for contamination by Xhc is therefore critical, but often time consuming, owing to the common use of dilution plating to enumerate Xhc before and after treatment. As a step towards the development of confident and facile detection methods for Xhc, we used an Illumina IIG to determine the genome sequence of Xhc M081, an isolate found on infected carrots grown in central Oregon. Short‐reads were de novo assembled and contigs ordered on the basis of a syntenic reference genome sequence to develop an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence. The genome sequence of isolate M081 of Xhc is thus the first for this clade, and is important for filling in the gaps along the phylogenetic tree of Xanthomonas in order to understand the evolutionary relationship and genetic diversity within this genus of important plant pathogens.

The observed long‐range synteny to representative isolates of foliar xanthomonads, except Xoo, could simply be a consequence of our efforts to use the Xcc ATCC 33913 genome to order the contigs of Xhc M081. Several points suggest otherwise. The genome of Xhc M081 was de novo assembled and synteny to the examined genomes of Xanthomonas species was found both within and across its contigs, with the exception of Xoo. Furthermore, the majority of genomic regions greater than 1 kb and unique to Xhc, as well as the regions inverted relative to Xac and Xcv, were wholly contained within contigs. Finally, the analysis of GC skew showed a general bias of guanine in the leading strand, indicating that there was no overt incorrect ordering of contigs (Fig. 1; Arakawa and Tomita, 2007; Rocha, 2004). Together, these observations justified the use of the Xcc ATCC 33913 genome to order the contigs of Xhc M081, and indicated that the observed synteny is a true reflection of similarities in genome structures rather than an artefact of our in silico efforts to improve the genome.

The high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xhc was derived from short reads and improved using only in silico approaches. This requires an acknowledgement of potential limitations. Unlike completed genomes, the draft assembly of Xhc still contained a considerable number of ambiguous bases, which we did not attempt to resolve. These did not appear to have a significant effect on our analysis because the number of annotated CDSs was similar to other xanthomonads. Repeated sequences, such as tandem repeats or duplicate regions in the genome, are particularly challenging for short‐read assembly (Pop and Salzberg, 2008). For example, Xcc ATCC 33913 is reported to have two rRNA‐encoding operons; we only identified one in Xhc M081. We suspect our sequenced isolate also has two rRNA‐encoding operons, but they collapsed into one contig.

Analysis of the Xhc M081 genome provided insights into the mechanisms of pathogenesis. We found a complete gum gene cluster, which is hypothesized to have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer and is an important acquisition for the evolution of pathogenesis by xanthomonads (Lu et al., 2008). Similarly, Xhc M081 encoded for a cluster of rpf genes, which is not surprising considering that these genes were probably present early in the evolution of Xanthomonadaceae (Lu et al., 2008). We also found clusters of genes that encode T4SS and T3SS. The T4SS‐encoding gene cluster of Xhc M081 was fragmented and we hesitate in speculating on its functionality. In contrast, inspection of the T3SS‐encoding region suggested it to be functional, and the need for T3SS in the pathogenesis by foliar pathogens of Xanthomonas is well demonstrated. T3SS delivers T3E proteins with demonstrable roles in the dampening and eliciting of the host defence (White et al., 2009). We identified 21 candidate T3E genes and the products from two, AvrBs2Xhc and XopQXhc, elicited HRs when transiently overexpressed in Nicotiana spp.

These so‐called ‘avirulence’ proteins are potential targets for the development of carrot cultivars resistant to Xhc through introgression of the corresponding R genes, assuming that Bs2 and the R gene corresponding to xopQ are present in the carrot germplasm. It is, however, unclear whether resistance gene‐mediated control can provide durable control. AvrBs2 is nearly ubiquitous and is required for full virulence by foliar Xanthomonas pathogens. However, Bs2 resistance in pepper incurs such a strong negative selective pressure that Xcv isolates with mutations in avrBs2 with little to no cost in virulence are prominent (Gassmann et al., 2000; Leach et al., 2001; Swords et al., 1996).

We found no evidence for genes of Xhc M081 that encode for members of the transcriptional activator‐like (TAL) family of T3Es (Boch et al., 2009; Moscou and Bogdanove, 2009). TAL effectors are characterized by a variable number of amino acid repeating motifs, nuclear localization signals and an acidic transcriptional activation domain. The repeated sequences could be difficult to assemble accurately, but hallmarks of TAL effector genes should still be detectable. We searched but failed to identify any hallmarks of TAL‐encoding genes, and thus suspect that the absence of TAL‐encoding genes from Xhc M081 is a true reflection of its repertoire of T3Es rather than of the limitations of short‐read assembly.

The genome sequence of Xhc M081 will be useful for the development of molecular detection methods for the diagnosis of Xhc contamination on carrot seeds. We developed primer pairs XhcPP02–XhcPP05 that specifically amplified a fragment of DNA from eight globally dispersed isolates of Xhc, but not from other species of Xanthomonas, another pathovar of X. hortorum or other bacteria commonly associated with plants. Practical implementation of these primers, however, will require additional testing against a larger collection of bacteria associated with carrot seed. Furthermore, to advance molecular diagnostics for Xhc, we intend to use the genomic regions corresponding to these primer pairs to develop primers for use in loop‐mediated isothermal PCR (LAMP; Mori and Notomi, 2009; Temple and Johnson, 2009). This method shows tremendous potential because it is quick to perform and obviates the need for dilution plating. LAMP also shows superior performance to quantitative PCR because of its robustness in the presence of PCR inhibitors (T. N. Temple and K. B. Johnson, unpublished data), and can be performed in various conditions/facilities with limited equipment and resources (Mori and Notomi, 2009).

The improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xhc M081 also has potential use in the molecular typing of Xhc. Primer pairs XhcPP08, XhcPP13 and XhcPP14 yielded similarly sized PCR products from isolates from the Northern Hemisphere (XhcPNW1, XhcPNW2 and XhcFr1). In contrast, these primer pairs resulted in polymorphic banding patterns when diagnosing isolates of Xhc from the Southern Hemisphere. Primer pairs XhcPP13 and XhcPP14 failed to yield a product from Xhc_Ch1, whereas primer pairs XhcPP08 and XhcPP13 failed to yield a product from Xhc_Ch3. Primer pair XhcPP13 failed to amplify a fragment of DNA and primer pair XhcPP08 yielded a larger sized product from isolate Xhc_Ar1.

The standard to which we attempted to adhere is considered to be sufficient for genome mining and comparative approaches (Chain et al., 2009). Genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis have been performed for numerous bacterial plant pathogens to identify virulence factors, to better understand phylogenetic relationships among closely related bacterial species and to identify sequences of DNA novel to a species for potential application to molecular detection technologies. Our sequencing and generation of an improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence for an isolate of X. hortorum has strong potential for the development of diagnostic tools for the management of Xhc, and provided a greater understanding of this economically important bacterial pathogen.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains and plasmids

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 4. Xanthomonas isolates and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 were grown in King's B medium at 28 °C. Escherichia coli and A. tumefaciens GV2260 were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C and 28 °C, respectively. The following concentrations of antibiotics were used: 50 µg/mL rifampicin (100 µg/mL for A. tumefaciens), 25 µg/mL gentamycin, 30 µg/mL kanamycin (100 µg/mL for A. tumefaciens) and 50 µg/mL cycloheximide.

Table 4.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant information | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | F‐Φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gryA96 thi‐1 hsdR17 (rK‐ mK+)supE44 relA1 deoRΔ(lacZY‐argF)U169 | Gibco‐BRL |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae M081 | Wild‐type | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae PNW1* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in USA | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae PNW2* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in USA | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae Fr1* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in France | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae Ar1* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in Argentina | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae Ch1* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in Chile | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae Ch2* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in Chile | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae Ch3* | Isolated from carrot seed lot produced in Chile | This study |

| Xanthomonas hortorum pv. hederae ATCC 9653 | Type strain | Vauterin et al. (1995) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. coriander ID‐A | Isolated from coriander seed lot produced in Oregon, USA | Poplawsky et al. (2004) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris ATCC 33913 | Type strain | da Silva et al. (2002) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria MTV1 | Wild‐type | This study |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV2260 | Wild‐type, RifR | Deblaere et al. (1985) |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 | Wild‐type, RifR | Cuppels (1986) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDONR207 | Gateway entry vector, GmR | Invitrogen |

| pDONR207:avrBs2 | CDS of avrBs2 in entry vector | This study |

| pDONR207:xopQ | CDS of xopQ in entry vector | This study |

| pDONR207:hopQ1‐1 | CDS of hopQ1‐1 in entry vector | J. H. Chang and J. L. Dangl, unpublished data |

| pGWB14 | Gateway destination vector, plant expression binary; CaMV 35S, C‐term 3XHA, KanR | Nakagawa et al. (2007) |

| pGWB14:avrBs2 | Plant expression binary with CDS of avrBs2 | This study |

| pGWB14:xopQ | Plant expression binary with CDS of xopQ | This study |

| pGWB14:hopQ1‐1 | Plant expression binary with CDS of hopQ1‐1 | This study |

| Used for genome comparisons | ||

| Xanthomonas albilineans | NC_013722 | Pieretti et al. (2009) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris str. ATCC33913 | NC_003902 | da Silva et al. (2002) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris str. 8004 | NC_007086 | Qian et al. (2005) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris str. B100 | NC_010688 | Vorholter et al. (2008) |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri str. 306 | NC_003919 | da Silva et al. (2002) |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria str. 85–10 | NC_007508 | Thieme et al. (2005) |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae KACC10331 | NC_006834 | Lee et al. (2005) |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae MAFF 311018 | NC_007705 | Ochiai et al. (2005) |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae PXO99A | NC_010717 | Salzberg et al. (2008) |

CaMV, cauliflower mosaic virus; CDS, coding sequence.

Isolates recovered from seed lots were typed as Xhc on the basis of growth on XCS and yeast–dextrose–calcium carbonate (YDC) media and of positive amplification with Xhc‐specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and loop‐mediated isothermal PCR (LAMP) primers (data not shown).

Molecular techniques

To prepare genomic DNA for high‐throughput sequencing, we isolated genomic DNA from Xhc M081 using osmotic shock and alkaline lysis followed by a phenol–chloroform extraction. DNA was prepared for Illumina sequencing according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). We used paired‐end sequencing of 36mers (three channels) and 76mers (one channel).

To test primer pairs for molecular diagnostics of Xhc, PCRs were carried out in 25‐µL reaction mixtures containing 1 × ThermoPol Buffer [20 mm Tris‐HCl, 10 mm (NH4)2SO4, 10 mm KCl, 2.0 mm MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X‐100, pH 8.8 at 25 °C], 250 µm of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 3.0 mm MgCl2, 1.0 µm of each primer (Table 5), 2.0 units Taq and Pfu DNA polymerase (25 : 1 mixture) and 2.5 µL of template genomic DNA. Cycling parameters for PCR were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 62.7 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 45 s, with a final extension of 72 °C for 1 min.

Table 5.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primer pair | Sequence of top strand primer (5′ to 3′) | Sequence of bottom strand primer (5′ to 3′) | Product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| XhcPP01 | TTGCGGCCGGCAAAATGCAC | CTACGATCAGGCGGCGCAGG | 1323 |

| XhcPP02 | ACGCAGGCAGACACGACACG | GCGCTTTCGCTCAATGGCGG | 1041 |

| XhcPP03 | TGGGTGCCATAGCGTTGCGG | TGCGCCTCTGGTTGCACTCG | 1226 |

| XhcPP04 | CTCCACGCGCAGGTCCAGTG | GAGAAGCCTGGCTGACGCCG | 620 |

| XhcPP05 | ACAGGCCGAGTCGCAACAGC | TGCTGCCGCGAAACCCGATT | 1119 |

| XhcPP06 | AATGGATGTGGCCGCACGGG | GGTTGCGCTGGATGCGGTCT | 963 |

| XhcPP07 | AGATCGATGCGCTCGGCAGC | TTCCGACGCCGTCACCTTGC | 1405 |

| XhcPP08 | GCGCATCCATTTGCCAGCCG | CCCGCTCTTGCTCACCTGCC | 875 |

| XhcPP09 | GTTGCTTGGCGTGCGTGGTG | CGCGTGGTGGGAGCGTTCTT | 1038 |

| XhcPP10 | AGCTGTTGCCGGAACTCGCC | GCGCAGACCACGAAGTCGCT | 1207 |

| XhcPP11 | GCTGGGCTCGTCGGCGTATC | GGGAATGCCGCGTTGGTGGA | 1224 |

| XhcPP12 | TAGCTGTTGCTGCACGGCCC | TCGTTGCGCCCTCGTTGTCC | 1437 |

| XhcPP13 | AGCGGCAGCCGAGAACAACC | GCGCGCGCTACGAGATGAGT | 517 |

| XhcPP14 | ATCGGCCTGTGCAACGGTGG | ACGCGCTGCGCTGAAGAGTT | 651 |

| XhcPP15 | CATTGCGCGCATACACCGCC | CGTTGGCGCAGGTGGGGATT | 552 |

| XhcPP16 | TGTCGAACAGCCGCCCGAAC | CAGCAGTGCGGACACGCAGA | 979 |

| XhcPP17 | TCGGGCACTTGAAGGCGCAG | GTCGGTCGCGCCGTAGATGG | 523 |

| XhcPP18 | AACTCGCGCGTTCTTGCGGA | TGGCGCAACGGGGATTGGTC | 666 |

| 9B* | CATTCCAAGAAGCAGCCA | TCGCTCTTAACACCGTCA | 900 |

| 3S* | TGCCTGGCTACGGAATTA | ATCCACATCCGCAACCAT | 300 |

| XopQ | CAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCATGGATTCCATCAGGCATCGCCCC | GAAAGCTGGGTGTTTTTCAGAAGCAAGCGCCAC | 1379 |

| AvrBs2 | CAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCATGCGTATTGGTCCTTTGCAACC | GAAAGCTGGGTGCTGCTCCGGCTCGATCTGTTTGGC | 2157 |

| XopX | AGCTTGGTCGCATGTTCACC | TCTGCGAAACAGAGCATTGG | 828 |

| XopR | CATTGACGGCAGCTGCTTGC | ATAACGATGCGATACAGCG | 666 |

| HrcC, hpa1, hpa2 | ATACCGATCAGACCGATCTG | GGCAATCCGCGATGTATCC | 600 |

| B1 and B2 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT | AGATTGGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT | Gateway cloning |

To clone candidate T3E genes, we used primer pairs in a two‐step PCR for the CDSs of avrBS2 and xopQ (Chang et al., 2005; Table 5). DNA fragments were cloned into pDONR207 using BP Clonase following the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The CDS for hopQ1‐1 was previously cloned in pDONR207 (J. H. Chang and J. L. Dangl, unpublished data). All three CDSs were cloned into pGWB14 using LR Clonase (Nakagawa et al., 2007; Invitrogen).

To prepare PCR fragments for Sanger sequencing, products were treated with ExoI and SAP for 20 min at 37 °C, followed by 40 min at 80 °C. Sanger and Illumina sequencing were performed at the Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing Core Laboratories (CGRB; Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA).

Genome assembly

The last four and six bases were trimmed off from the 36mer and 76mer reads, respectively, and all short reads that contained ambiguous bases, as well as its paired read, were removed. We used Velvet 0.7.55 to de novo assemble the reads, and the highest quality assembly was identified using methods described previously (Kimbrel et al., 2010; Zerbino and Birney, 2008). We used Mauve Aligner 2.3 (default settings) and the genome sequence of Xcc strain ATCC 33913 as a reference to order the Xhc M081 contigs (da Silva et al., 2002; Rissman et al., 2009). We used an automated method, as described previously, to annotate the improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of Xhc M081 (Delcher et al., 1999; Giovannoni et al., 2008; Kimbrel et al., 2010).

Bioinformatic analyses

Circular diagrams were plotted using DNAplotter (Carver et al., 2009; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Artemis/circular/).

Synteny plots were generated by first identifying all the unique 25mers present within the genome sequences for Xcc strain ATCC 33913, Xac strain 306, Xcv strain 85‐10 and Xoo PXO99A (da Silva et al., 2002; Salzberg et al., 2008; Thieme et al., 2005). We used cashx to map the unique 25mers to the genome sequence of Xhc M081, and R to display perfect matching 25mers relative to their coordinates in the respective genomes (Fahlgren et al., 2009; R Development Core Team, 2007).

Phylogenomic relationships of Xhc M081 to other isolates of Xanthomonas were determined using hal (Table 4; Robbertse et al., 2006; http://aftol.org/pages/Halweb3.htm). The tree was visualized using the Archaeopteryx and Forester Java application (Zmasek and Eddy, 2001; http://www.phylosoft.org/archaeopteryx/).

For MLSA, we extracted partial sequences of dnaK, fyuA, gyrB and rpoD from the genome sequence of Xhc M081. Sequences were concatenated and used in comparisons with corresponding sequences as determined previously (Young et al., 2008). Neighbour‐joining trees were generated with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

To identify regions unique to Xhc M081, we used blastn to compare the Xhc M081 genome to Xcc, Xac, Xcv and Xoo (e‐value >1 × 10−7). Contiguous regions larger than 1 kb were used as queries in blastn searches of the NCBI nr/nt database. NCBI Primer‐blast was used to design PCR primers specific to these regions of the Xhc M081 genome by excluding those that could potentially amplify known xanthomonad sequences (taxid:338; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer‐blast/).

Identification of candidate T3E genes

We used a Perl regular expression to search for the PIP‐box sequence, TTCGB‐N15‐TTCGB, where B is any base except adenine (Fenselau and Bonas, 1995; Tsuge et al., 2005). CDSs were classified as candidate T3Es if they met both of the following criteria: (i) the CDS must be no more than 300 bp downstream of an identified PIP‐box; (ii) the translated sequence of the CDS must have no or low homology to sequences with annotated functions not normally associated with T3E proteins. Amino acid sequences of confirmed T3Es from xanthomonads and other phytopathogens were also used as queries in blastp searches (e‐value <1 × 10−7) against the 4493 Xhc M081 translated CDSs (http://www.xanthomonas.org;Kimbrel et al., 2010; White et al., 2009).

Agrobacterium‐mediated transient expression

Binary vectors carrying candidate T3E genes were mobilized into A. tumefaciens GV2260 via three‐way conjugation. Bacteria were grown overnight in King's B medium, washed in 10 mm MgCl2 and resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. A blunt syringe was used to infiltrate bacteria into leaves of 6‐week‐old wild‐type N. tabacum, N. benthamiana or transgenic N. benthamiana constitutively expressing the Bs2 resistance gene (Tai et al., 1999). Leaves were scored at 24 hpi.

Plants were maintained in a growth chamber cycling 9 h light/25 °C during the day and 15 h dark/20 °C during the night.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DEBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number AEEU00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AEEU01000000.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Complete neighbour‐joining tree of concatenated nucleotide sequences for partial dnaK, fyuA, gyrB and rpoD genes from Xanthomonas strains (Young et al., 2008). Numbers indicate bootstrap support (r = 1000). The scale bars indicate the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Table S1 Testing Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae (Xhc) Primer Pair (XhcPP) against other plant‐associated bacteria.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Chris Sullivan and Mark Dasenko (Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing) for computational support and DNA sequencing, Philip Hillebrand for assistance, Jason Cumbie and Dr Joey Spatafora for advice, Dr Brian Staskawicz for providing transgenic N. benthamiana seeds, and Dr Virginia Stockwell and Dr Joyce Loper for providing their culture collection. Xhc M081 was originally isolated by Fred Crowe at Oregon State University (OSU), Central Oregon Research and Extension Center, Madras, OR, USA. Xhc‐infested carrot seed lots, Xcv strain MTV1 and Xccor ID‐A were provided by Lindsey du Toit and Mike Derie of Washington State University, Mt Vernon, WA, USA. This research was supported in part by start‐up funds from OSU and the National Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2008–35600‐18783 from the United States Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Microbial Functional Genomics Program to JHC and the California Fresh Carrot Advisory Board to KBJ.

REFERENCES

- Abu Khweek, A. , Fetherston, J.D. and Perry, R.D. (2010) Analysis of HmsH and its role in plague biofilm formation. Microbiology, 156, 1424–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez‐Martinez, C.E. and Christie, P.J. (2009) Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 775–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa, K. and Tomita, M. (2007) The GC Skew Index: a measure of genomic compositional asymmetry and the degree of replicational selection. Evol. Bioinform. Online, 3, 159–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin, D.K. , Song, Y. , Baek, M.S. , Sawa, Y. , Singh, G. , Taylor, B. , Rubio‐Mills, A. , Flanagan, J.L. , Wiener‐Kronish, J.P. and Lynch, S.V. (2007) Presence or absence of lipopolysaccharide O antigens affects type III secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Bacteriol. 189, 2203–2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom, J. , Albaum, S.P. , Doppmeier, D. , Puhler, A. , Vorholter, F.J. , Zakrzewski, M. and Goesmann, A. (2009) EDGAR: a software framework for the comparative analysis of prokaryotic genomes. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch, J. , Scholze, H. , Schornack, S. , Landgraf, A. , Hahn, S. , Kay, S. , Lahaye, T. , Nickstadt, A. and Bonas, U. (2009) Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL‐type III effectors. Science, 326, 1509–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner, D. and Bonas, U. (2010) Regulation and secretion of Xanthomonas virulence factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABI (2010) Crop Protection Compendium. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, T. , Thomson, N. , Bleasby, A. , Berriman, M. and Parkhill, J. (2009) DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics, 25, 119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain, P.S. , Grafham, D.V. , Fulton, R.S. , Fitzgerald, M.G. , Hostetler, J. , Muzny, D. , Ali, J. , Birren, B. , Bruce, D.C. , Buhay, C. , Cole, J.R. , Ding, Y. , Dugan, S. , Field, D. , Garrity, G.M. , Gibbs, R. , Graves, T. , Han, C.S. , Harrison, S.H. , Highlander, S. , Hugenholtz, P. , Khouri, H.M. , Kodira, C.D. , Kolker, E. , Kyrpides, N.C. , Lang, D. , Lapidus, A. , Malfatti, S.A. , Markowitz, V. , Metha, T. , Nelson, K.E. , Parkhill, J. , Pitluck, S. , Qin, X. , Read, T.D. , Schmutz, J. , Sozhamannan, S. , Sterk, P. , Strausberg, R.L. , Sutton, G. , Thomson, N.R. , Tiedje, J.M. , Weinstock, G. , Wollam, A. and Detter, J.C. (2009) Genomics. Genome project standards in a new era of sequencing. Science, 326, 236–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.H. , Urbach, J.M. , Law, T.F. , Arnold, L.W. , Hu, A. , Gombar, S. , Grant, S.R. , Ausubel, F.M. and Dangl, J.L. (2005) A high‐throughput, near‐saturating screen for type III effector genes from Pseudomonas syringae . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 2549–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppels, D.A. (1986) Generation and characterization of Tn5 insertion mutations in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51, 323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson, L. , Powers, J. and Whitfield, C. (2005) The C‐terminal domain of the nucleotide‐binding domain protein Wzt determines substrate specificity in the ATP‐binding cassette transporter for the lipopolysaccharide O‐antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes O8 and O9a. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30 310–30 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, A. , Rangaraj, N. and Sonti, R.V. (2009) Multiple adhesin‐like functions of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae are involved in promoting leaf attachment, entry, and virulence on rice. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere, R. , Bytebier, B. , De Greve, H. , Deboeck, F. , Schell, J. , Van Montagu, M. and Leemans, J. (1985) Efficient octopine Ti plasmid‐derived vectors for Agrobacterium‐mediated gene transfer to plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 4777–4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher, A.L. , Harmon, D. , Kasif, S. , White, O. and Salzberg, S.L. (1999) Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4636–4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren, N. , Sullivan, C.M. , Kasschau, K.D. , Chapman, E.J. , Cumbie, J.S. , Montgomery, T.A. , Gilbert, S.D. , Dasenko, M. , Backman, T.W. , Givan, S.A. and Carrington, J.C. (2009) Computational and analytical framework for small RNA profiling by high‐throughput sequencing. RNA, 15, 992–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenselau, S. and Bonas, U. (1995) Sequence and expression analysis of the hrpB pathogenicity operon of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria which encodes eight proteins with similarity to components of the Hrp, Ysc, Spa, and Fli secretion systems. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 8, 845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, W. , Dahlbeck, D. , Chesnokova, O. , Minsavage, G.V. , Jones, J.B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2000) Molecular evolution of virulence in natural field strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria . J. Bacteriol. 182, 7053–7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni, S.J. , Hayakawa, D.H. , Tripp, H.J. , Stingl, U. , Givan, S.A. , Cho, J.C. , Oh, H.M. , Kitner, J.B. , Vergin, K.L. and Rappe, M.S. (2008) The small genome of an abundant coastal ocean methylotroph. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1771–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.T. and Yao, N. (2004) The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant–pathogen interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudesblat, G.E. , Torres, P.S. and Vojnov, A.A. (2009) Xanthomonas campestris overcomes Arabidopsis stomatal innate immunity through a DSF cell‐to‐cell signal‐regulated virulence factor. Plant Physiol. 149, 1017–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, D.S. , Vinatzer, B.A. , Sarkar, S.F. , Ranall, M.V. , Kettler, G. and Greenberg, J.T. (2002) A functional screen for the type III (Hrp) secretome of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae . Science, 295, 1722–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, I.B. , Schmitt, L. and Young, J. (2005) Type 1 protein secretion in bacteria, the ABC‐transporter dependent pathway (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 22, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen, F. , Ferreiro, D.U. , Oddo, C.G. , Ielmini, M.V. , Becker, A. , Puhler, A. and Ielpi, L. (1998) Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris gum mutants: effects on xanthan biosynthesis and plant virulence. J. Bacteriol. 180, 1607–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (1990) Widespread distribution and fitness contribution of Xanthomonas campestris avirulence gene avrBs2 . Nature, 346, 385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel, J.A. , Givan, S.A. , Halgren, A.B. , Creason, A.L. , Mills, D.I. , Banowetz, G.M. , Armstrong, D.J. and Chang, J.H. (2010) An improved, high‐quality draft genome sequence of the Germination‐Arrest Factor‐producing Pseudomonas fluorescens WH6. BMC Genomics, 11, 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnik, R. , Kruger, A. , Thieme, F. , Urban, A. and Bonas, U. (2006) Specific binding of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria AraC‐type transcriptional activator HrpX to plant‐inducible promoter boxes. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7652–7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J.M. , Hamilton, J.P. , Diaz, J.G.Q. , Van Sluys, M.A. , Burgos, J.R.G. , Cruz, C.M.V. , Buell, C.R. , Tisserat, N.A. and Leach, J.E. (2010) Genomics‐based diagnostic marker development for Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and X. oryzae pv. oryzicola . Plant Dis. 94, 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, J.E. , Vera Cruz, C.M. , Bai, J. and Leung, H. (2001) Pathogen fitness penalty as a predictor of durability of disease resistance genes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39, 187–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.M. , Park, Y.J. , Park, D.S. , Kang, H.W. , Kim, J.G. , Song, E.S. , Park, I.C. , Yoon, U.H. , Hahn, J.H. , Koo, B.S. , Lee, G.B. , Kim, H. , Park, H.S. , Yoon, K.O. , Kim, J.H. , Jung, C.H. , Koh, N.H. , Seo, J.S. and Go, S.J. (2005) The genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae KACC10331, the bacterial blight pathogen of rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 577–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, P.B. , Peet, R.C. and Panopoulos, N.J. (1986) Gene cluster of Pseudomonas syringae pv. ‘phaseolicola’ controls pathogenicity of bean plants and hypersensitivity of nonhost plants. J. Bacteriol. 168, 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H. , Patil, P. , Van Sluys, M.A. , White, F.F. , Ryan, R.P. , Dow, J.M. , Rabinowicz, P. , Salzberg, S.L. , Leach, J.E. , Sonti, R. , Brendel, V. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2008) Acquisition and evolution of plant pathogenesis‐associated gene clusters and candidate determinants of tissue‐specificity in Xanthomonas . PLoS ONE, 3, e3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. , Umesh, K. , Davis, R. and Gilbertson, R. (2004) Development of PCR‐based assays for detecting Xanthomonas campestris pv. carotae, the carrot bacterial leaf blight pathogen, from different substrates. Plant Dis. 88, 1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X. , Ludy, R. , Fraley, C. and Osterbauer, N. (2009) Identification of Xanthomonas leaf blight from umbelliferous seed crops grown in Oregon (Abstr.). Phytopathology, 99, S84. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.M. , Almeida, N.F., Jr , Potnis, N. , Digiampietri, L.A. , Adi, S.S. , Bortolossi, J.C. , da Silva, A.C. , da Silva, A.M. , de Moraes, F.E. , de Oliveira, J.C. , de Souza, R.F. , Facincani, A.P. , Ferraz, A.L. , Ferro, M.I. , Furlan, L.R. , Gimenez, D.F. , Jones, J.B. , Kitajima, E.W. , Laia, M.L. , Leite, R.P., Jr , Nishiyama, M.Y. , Rodrigues Neto, J. , Nociti, L.A. , Norman, D.J. , Ostroski, E.H. , Pereira, H.A., Jr , Staskawicz, B.J. , Tezza, R.I. , Ferro, J.A. , Vinatzer, B.A. and Setubal, J.C. (2010) Novel insights into the genomic basis of citrus canker based on the genome sequences of two strains of Xanthomonas fuscans subsp. aurantifolii . BMC Genomics, 11, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y. and Notomi, T. (2009) Loop‐mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a rapid, accurate, and cost‐effective diagnostic method for infectious diseases. J. Infect. Chemother. 15, 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou, M.J. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2009) A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science, 326, 1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaihara, T. , Tamura, N. , Murata, Y. and Iwabuchi, M. (2004) Genetic screening of Hrp type III‐related pathogenicity genes controlled by the HrpB transcriptional activator in Ralstonia solanacearum . Mol. Microbiol. 54, 863–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, T. , Kurose, T. , Hino, T. , Tanaka, K. , Kawamukai, M. , Niwa, Y. , Toyooka, K. , Matsuoka, K. , Jinbo, T. and Kimura, T. (2007) Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niepold, F. , Anderson, D. and Mills, D. (1985) Cloning determinants of pathogenesis from Pseudomonas syringae pathovar syringae . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, H. , Inoue, Y. , Takeya, M. , Sasaki, A. and Kaku, H. (2005) Genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae suggests contribution of large numbers of effector genes and insertion sequences to its race diversity. Jpn Agric. Res. Q. 39, 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, N. , Aritua, V. , Heeney, J. , Cowie, C. , Bew, J. and Stead, D. (2007) Phylogenetic analysis of Xanthomonas species by comparison of partial gyrase B gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 2881–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, N. , Cowie, C. , Heeney, J. and Stead, D. (2009) Phylogenetic structure of Xanthomonas determined by comparison of gyrB sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59, 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petnicki‐Ocwieja, T. , Schneider, D.J. , Tam, V.C. , Chancey, S.T. , Shan, L. , Jamir, Y. , Schechter, L.M. , Janes, M.D. , Buell, C.R. , Tang, X. , Collmer, A. and Alfano, J.R. (2002) Genomewide identification of proteins secreted by the Hrp type III protein secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 7652–7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti, I. , Royer, M. , Barbe, V. , Carrere, S. , Koebnik, R. , Cociancich, S. , Couloux, A. , Darrasse, A. , Gouzy, J. , Jacques, M.A. , Lauber, E. , Manceau, C. , Mangenot, S. , Poussier, S. , Segurens, B. , Szurek, B. , Verdier, V. , Arlat, M. and Rott, P. (2009) The complete genome sequence of Xanthomonas albilineans provides new insights into the reductive genome evolution of the xylem‐limited Xanthomonadaceae . BMC Genomics, 10, 616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop, M. and Salzberg, S.L. (2008) Bioinformatics challenges of new sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 24, 142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplawsky, A.R. , Robles, L. , Chun, W. , Derie, M.L. , du Toit, L.J. , Meng, X. and Gilbertson, R. (2004) Identification of a Xanthomonas pathogen of coriander from Oregon USA (Abstr.). Phytopathology, 94, S85. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W. , Jia, Y. , Ren, S.X. , He, Y.Q. , Feng, J.X. , Lu, L.F. , Sun, Q. , Ying, G. , Tang, D.J. , Tang, H. , Wu, W. , Hao, P. , Wang, L. , Jiang, B.L. , Zeng, S. , Gu, W.Y. , Lu, G. , Rong, L. , Tian, Y. , Yao, Z. , Fu, G. , Chen, B. , Fang, R. , Qiang, B. , Chen, Z. , Zhao, G.P. , Tang, J.L. and He, C. (2005) Comparative and functional genomic analyses of the pathogenicity of phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris . Genome Res. 15, 757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2007) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; ISBN 3‐900051‐07‐0, URL. Available at http://www.R‐project.org[accessed on Mar 29, 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- Rissman, A.I. , Mau, B. , Biehl, B.S. , Darling, A.E. , Glasner, J.D. and Perna, N.T. (2009) Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics, 25, 2071–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbertse, B. , Reeves, J.B. , Schoch, C.L. and Spatafora, J.W. (2006) A phylogenomic analysis of the Ascomycota. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetta, H.L. and Lam, J.S. (1997) Identification and functional characterization of an ABC transport system involved in polysaccharide export of A‐band lipopolysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Bacteriol. 179, 4713–4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, E.P. (2004) The replication‐related organization of bacterial genomes. Microbiology, 150, 1609–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg, S.L. , Sommer, D.D. , Schatz, M.C. , Phillippy, A.M. , Rabinowicz, P.D. , Tsuge, S. , Furutani, A. , Ochiai, H. , Delcher, A.L. , Kelley, D. , Madupu, R. , Puiu, D. , Radune, D. , Shumway, M. , Trapnell, C. , Aparna, G. , Jha, G. , Pandey, A. , Patil, P.B. , Ishihara, H. , Meyer, D.F. , Szurek, B. , Verdier, V. , Koebnik, R. , Dow, J.M. , Ryan, R.P. , Hirata, H. , Tsuyumu, S. , Won Lee, S. , Seo, Y.S. , Sriariyanum, M. , Ronald, P.C. , Sonti, R.V. , Van Sluys, M.A. , Leach, J.E. , White, F.F. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2008) Genome sequence and rapid evolution of the rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae PXO99A. BMC Genomics, 9, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad, N.W. and Stall, R.E. (1988) Xanthomonas In: Laboratory Guide for Identification of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, 2nd edn (Schaad N.W., ed.), pp. 81–94. St. Paul, MN: APS Press. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A.C. , Ferro, J.A. , Reinach, F.C. , Farah, C.S. , Furlan, L.R. , Quaggio, R.B. , Monteiro‐Vitorello, C.B. , Van Sluys, M.A. , Almeida, N.F. , Alves, L.M. , do Amaral, A.M. , Bertolini, M.C. , Camargo, L.E. , Camarotte, G. , Cannavan, F. , Cardozo, J. , Chambergo, F. , Ciapina, L.P. , Cicarelli, R.M. , Coutinho, L.L. , Cursino‐Santos, J.R. , El‐Dorry, H. , Faria, J.B. , Ferreira, A.J. , Ferreira, R.C. , Ferro, M.I. , Formighieri, E.F. , Franco, M.C. , Greggio, C.C. , Gruber, A. , Katsuyama, A.M. , Kishi, L.T. , Leite, R.P. , Lemos, E.G. , Lemos, M.V. , Locali, E.C. , Machado, M.A. , Madeira, A.M. , Martinez‐Rossi, N.M. , Martins, E.C. , Meidanis, J. , Menck, C.F. , Miyaki, C.Y. , Moon, D.H. , Moreira, L.M. , Novo, M.T. , Okura, V.K. , Oliveira, M.C. , Oliveira, V.R. , Pereira, H.A. , Rossi, A. , Sena, J.A. , Silva, C. , de Souza, R.F. , Spinola, L.A. , Takita, M.A. , Tamura, R.E. , Teixeira, E.C. , Tezza, R.I. , Trindade dos Santos, M. , Truffi, D. , Tsai, S.M. , White, F.F. , Setubal, J.C. and Kitajima, J.P. (2002) Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature, 417, 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swords, K.M. , Dahlbeck, D. , Kearney, B. , Roy, M. and Staskawicz, B.J. (1996) Spontaneous and induced mutations in a single open reading frame alter both virulence and avirulence in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria avrBs2 . J. Bacteriol. 178, 4661–4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai, T.H. , Dahlbeck, D. , Clark, E.T. , Gajiwala, P. , Pasion, R. , Whalen, M.C. , Stall, R.E. and Staskawicz, B.J. (1999) Expression of the Bs2 pepper gene confers resistance to bacterial spot disease in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14 153–14 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple, T.N. and Johnson, K.B. (2009) Detection of Xanthomonas hortorum pv. carotae on and in carrot with loop‐mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (Abstr.). Phytopathology, 99, S186. [Google Scholar]

- Thieme, F. , Koebnik, R. , Bekel, T. , Berger, C. , Boch, J. , Buttner, D. , Caldana, C. , Gaigalat, L. , Goesmann, A. , Kay, S. , Kirchner, O. , Lanz, C. , Linke, B. , McHardy, A.C. , Meyer, F. , Mittenhuber, G. , Nies, D.H. , Niesbach‐Klosgen, U. , Patschkowski, T. , Ruckert, C. , Rupp, O. , Schneiker, S. , Schuster, S.C. , Vorholter, F.J. , Weber, E. , Puhler, A. , Bonas, U. , Bartels, D. and Kaiser, O. (2005) Insights into genome plasticity and pathogenicity of the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria revealed by the complete genome sequence. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7254–7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Toit, L.J. , Crowe, F.J. , Derie, M.L. , Simmons, R.B. and Pelter, G.Q. (2005) Bacterial blight in carrot seed crops in the Pacific Northwest. Plant Dis. 89, 896–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge, S. , Terashima, S. , Furutani, A. , Ochiai, H. , Oku, T. , Tsuno, K. , Kaku, H. and Kubo, Y. (2005) Effects on promoter activity of base substitutions in the cis‐acting regulatory element of HrpXo regulons in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae . J. Bacteriol. 187, 2308–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauterin, L. , Hoste, B. , Kersters, K. and Swings, J. (1995) Reclassification of Xanthomonas . Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45, 472–489. [Google Scholar]

- Vorholter, F.J. , Schneiker, S. , Goesmann, A. , Krause, L. , Bekel, T. , Kaiser, O. , Linke, B. , Patschkowski, T. , Ruckert, C. , Schmid, J. , Sidhu, V.K. , Sieber, V. , Tauch, A. , Watt, S.A. , Weisshaar, B. , Becker, A. , Niehaus, K. and Puhler, A. (2008) The genome of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris B100 and its use for the reconstruction of metabolic pathways involved in xanthan biosynthesis. J. Biotechnol. 134, 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.H. , He, Y. , Gao, Y. , Wu, J.E. , Dong, Y.H. , He, C. , Wang, S.X. , Weng, L.X. , Xu, J.L. , Tay, L. , Fang, R.X. and Zhang, L.H. (2004) A bacterial cell–cell communication signal with cross‐kingdom structural analogues. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]