Heart failure is one of the leading causes of death worldwide and has been singled out as an emerging epidemic.1, 2 With a 5‐year survival rate of 50%, heart failure poses a tremendous burden on our economic and healthcare system. Despite extensive interests and paramount clinical needs, our understanding of heart failure remains incomplete. As a consequence, there is currently no cure.

Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors of heart failure. Under high blood pressure, cardiac ventricular wall stress is mounted. According to Laplace's law, an increase in cardiac wall thickness can effectively ameliorate wall stress.3 This so‐called concentric cardiac growth is achieved by upregulation of sarcomere biosynthesis and enlargement of individual cardiac myocytes attributed to limited replicative capacity in the adult heart. In response to persistent stress, however, this once adaptive hypertrophic growth may progress into decompensation and heart failure. Over the past few decades, numerous signaling molecules and pathways have been identified in cardiac hypertrophic growth and heart failure.4 These processes involve extensive cardiac remodeling in metabolism, structure, and electrophysiology. Growing evidence indicates that metabolic remodeling precedes most, if not all, other pathological alterations and likely plays an essential role in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Ischemic heart disease is another critical contributing factor to heart failure. Patients surviving myocardial infarction (MI) may undergo extensive pathological remodeling in the heart with major metabolic derangements. Here, we review recent findings of cardiac metabolic changes in response to hemodynamic stress and cardiac ischemia with a focus on glucose utilization. We also discuss potential therapeutic targets from carbohydrate metabolic pathways to tackle this devastating heart disease.

Glucose Metabolism in the Heart

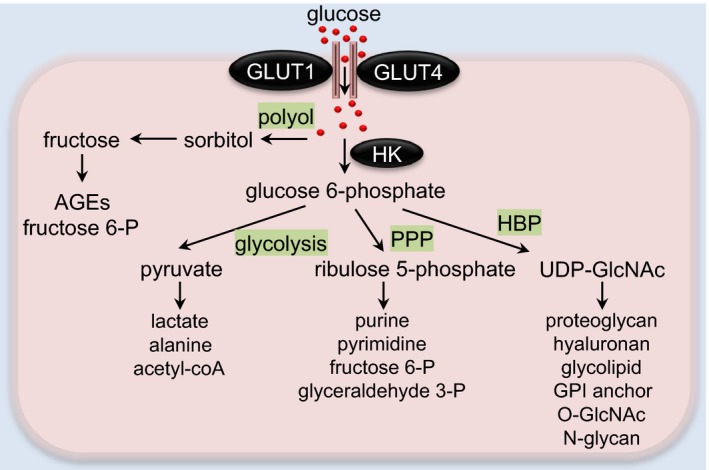

The heart is an omnivore, consuming fuel constantly and using any substrate available.8 The high rates of ATP production and turnover are critical in maintaining cardiac contractility to deliver blood and oxygen to the other organs. Under normal conditions, cardiac ATP is mainly derived from fatty acid (FA) oxidation (FAO), with glucose metabolism contributing less. However, under stress conditions, FAO may be reduced, which is concomitant with increased glucose utilization.9 Glucose uptake in cardiomyocytes is mediated by glucose transporters (GLUTs), with GLUT1 and GLUT4 as the most abundant isoforms.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Whereas GLUT1 is highly expressed in the fetal heart, GLUT4 is predominant in the adult heart. Inside cardiac myocytes, glucose may be first phosphorylated to glucose 6‐phosphate by hexokinase or converted to sorbitol by the polyol pathway. Glucose 6‐phosphate subsequently goes through multiple metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP; Figure 1).6 Pathological alterations of these pathways in cardiac hypertrophy and ischemic heart disease are associated with impaired signaling transduction, perturbed ion and redox homeostasis, and contractile dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Glucose metabolic pathways in the heart. In cardiomyocytes, glucose is transported through glucose transporters GLUT1 or GLUT4. Polyol pathway‐derived sorbitol and fructose may be converted to AGEs or fructose 6‐P for glycolytic use. Intracellular glucose can be phosphorylated to glucose 6‐phosphate by hexokinase (HK). Glucose 6‐phosphate is then metabolized bv multiple pathways, including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). In the cytosol, pyruvate can be utilized to form alanine or lactate. In mitochondria, pyruvate is converted to acetyl‐CoA for the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Ribulose 5‐P derived from PPP can be used for pyrimidine/purine synthesis or converted into intermediates of glycolysis. UDP‐GlcNAc, the final product of HBP, serves as a substrate for the synthesis of proteoglycans, hyaluronan, glycolipid, GPI anchor, O‐GlcNAc modification, and N‐glycan. AGEs indicates advanced glycation end products; fructose 6‐P, fructose 6‐phosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter; glyceraldehyde 3‐P, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; O‐GlcNAc, O‐linked β‐N‐acetylglucosamine; ribulose 5‐P, ribulose 5‐phosphate; UDP‐GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N‐acetylglucosamine.

Glycolysis

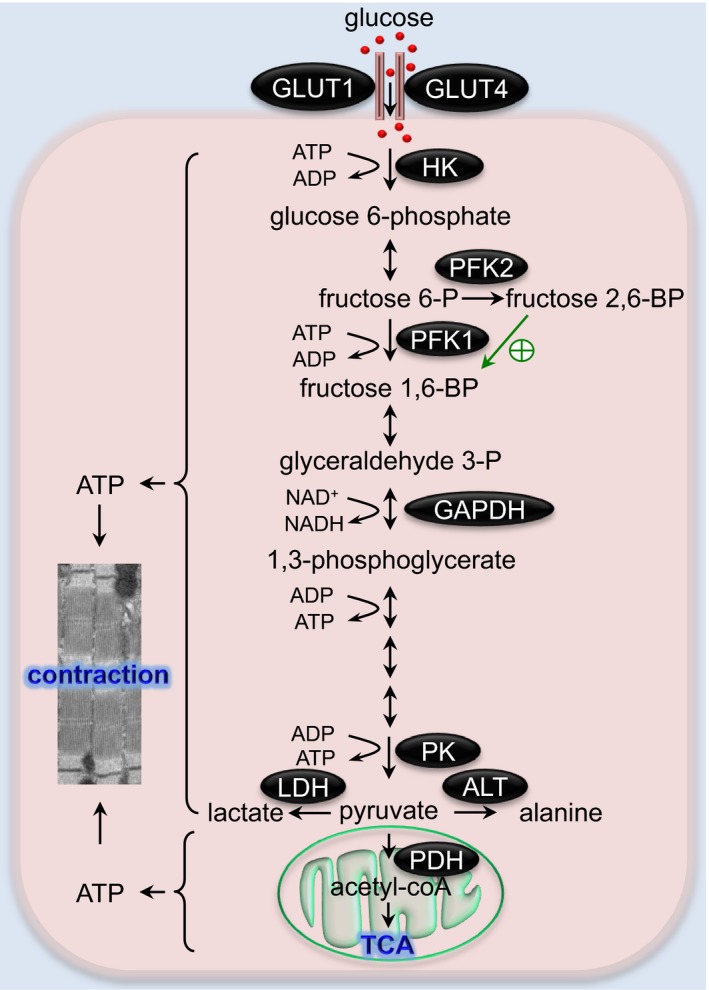

Glycolysis is arguably the most important route for glucose metabolism in a cell, which produces pyruvate, NADH, and ATP. ATP yield from glycolysis, however, contributes only a small portion of the overall ATP pool in the normal heart.17 In cytosol, pyruvate can be further utilized to form alanine by alanine transaminase or reduced to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase. On the other hand, pyruvate is oxidized (known as pyruvate oxidation or glucose oxidation) to generate acetyl‐CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase that fuels the tricarboxylic acid cycle in mitochondria. Three enzymes, including hexokinase, phosphofructokinase (PFK), and pyruvate kinase, catalyze irreversible reactions of glycolysis; thus, they are proposed as critical enzymes in governing glycolysis.18 The control of glycolysis is variably distributed between enzymes and counts on the substrate, hormone, oxygen deficiency, or other different conditions.19 Hexokinase is the first enzyme of glycolysis. Its control of glucose transport is abrogated in the presence of insulin whereas its usage of glucose is favored in the presence of ketones. The second regulatory enzyme of glycolysis is PFK that has 2 isoforms: PFK1 and PFK2. Fructose 6‐phosphate is converted to fructose 1,6‐bisphosphate and fructose 2,6‐bisphosphate (fructose 2,6‐BP) by PFK1 and PFK2, respectively (Figure 2). Fructose 2,6‐BP is a potent activator of PFK1 for production of fructose 1,6‐bisphosphate and following glycolytic flux.20 Pyruvate kinase, the final enzyme of glycolysis, regulates the flux from this pathway. Its control of glycolysis is increased during cardiac perfusion with glucose in the presence of ketones or insulin or both.19 Studies have shown that glycolysis plays a crucial role in maintaining contractile function attributed to the tight coupling of glycolysis‐derived ATP with ion pump ATPase.21

Figure 2.

The glycolysis pathway in the heart. A series of enzymatic reactions of glycolysis convert glucose to pyruvate, which may be reduced to lactate or further catabolized by the TCA cycle. Glycolysis‐derived ATP plays a crucial role in maintaining the contractile function of the heart. The green arrow indicates activation of PFK1 by fructose 2,6‐biphosphate. ALT indicates alanine transaminase; fructose 1,6‐BP, fructose 1,6‐bisphosphate; fructose 2,6‐BP, fructose 2,6‐bisphosphate; fructose 6‐P, fructose 6‐phosphate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; GLUT, glucose transporter; glyceraldehyde 3‐P, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate; HK, hexokinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PFK, phosphofructokinase; PK, pyruvate kinase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Glycolysis in the Hypertrophic Heart

During cardiac hypertrophic growth and pathological remodeling, there is a prominent metabolic shift from FAO to glucose utilization. This alteration is associated with an increase in glycolysis in hypertrophied hearts (Table).22, 23, 24, 25 At the mechanistic level, intracellular free AMP in the cardiomyocyte is increased when the heart faces pressure overload, which consequently transduces signaling through AMP‐activated protein kinase. As a result, synthesis of fructose 2,6‐BP, an activator of PFK1, is upregulated and glucose transporter migration to sarcolemmal membrane is enhanced.23 Consistently, a transgenic mouse model overexpressing kinase‐deficient PFK2 in cardiomyocytes has reduced glycolysis attributed to the low level of fructose 2,6‐BP.24 These mice exhibit more‐profound hypertrophy, elevated fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction than control animals in response to pressure overload.25 Failure to increase fructose 2,6‐BP and glycolysis may therefore contribute to the deleterious structural and functional changes in the heart. Taken together, elevation of glycolysis through activation of fructose 2,6‐BP and PFK1 is an adaptive response to cardiac pressure overload. The increase in glycolysis is, however, accompanied by reduced or normal glucose oxidation, which may lead to an uncoupling between glucose uptake and oxidation. This imbalance has been implicated in pathological hypertrophic remodeling in the heart.22

Table 1.

Phenotypes of the Animal Models in Which Glucose Metabolism Is Altered

| Animal Model | Background | Condition | Events | Cardiac Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac‐specific knockout of GLUT4 | C57BL/6, FVB | Baseline |

↑Insulin‐independent glucose uptake ↓Insulin‐dependent glucose uptake |

Mild hypertrophy | 12 |

| I/R | ↓Glycolysis | ↑I/R injury | 13 | ||

| Cardiac‐specific overexpression of GLUT1 | FVB | Baseline |

↑Insulin‐independent glucose uptake ↑Glycolysis |

Normal | 14 |

| 8 wks post‐TAC | ↔Myocardial energetics |

↓Cardiac dysfunction ↑Long‐term survival rate |

|||

| Inducible cardiac‐specific overexpression of GLUT1 | FVB | Baseline (6–10 wks old) | ↑Glucose utilization, glycolysis | Normal | 15 |

| 4 wks post‐TAC |

↑Glucose oxidation, [G‐1‐P], [lactic acid], [glycogen], ATP synthesis ↑FA metabolism, OXPHOS genes |

↓Fibrosis ↑Cardiac hypertrophy |

|||

| Cardiac‐specific knockout of GLUT1 | C57BL/6 | Baseline (6–10 wks) |

↓Glycolysis, glucose oxidation ↑FAO |

Normal | 16 |

| 4 wks post‐TAC |

↓Glycolysis, glucose oxidation ↑FAO |

↔Hypertrophy ↔Mitochondrial function |

|||

| Cardiac‐specific kinase‐deficient PFK‐2 | FVB | Baseline (3–4 m) |

↓Glycolysis, [F‐2,6‐P2], [F‐1,6‐P2] ↑[G‐6‐P], [F‐6‐P], [UDP‐GlcNAc], [glycogen] ↓Insulin sensitivity |

Mild hypertrophy ↑Fibrosis ↓Cardiac function |

24 |

| 13 wks post‐TAC | ↓[F‐2,6‐P2], glycolysis |

↑Cardiac hypertrophy ↑Fibrosis, cardiac dysfunction |

25 | ||

| WT | FVB/NJ | 4 wks of treadmill training |

↓Glycolysis, PFK activity, acute ↑Glycolysis, PFK activity, recovered |

↑Physiological hypertrophy ↑Cardiac function |

26 |

| Cardiac‐specific kinase‐deficient PFK‐2 | Baseline (15–16 wks old) | ↓Glycolysis, PFK activity |

↑Physiological hypertrophy ↑Cardiac function |

||

| Cardiac‐specific phosphatase‐deficient PFK‐2 | Baseline (15–16 wks old) | ↑Glycolysis | ↑Pathological hypertrophy | ||

| Cardiac‐specific phosphatase‐deficient PFK‐2 | FVB/NJ | Baseline (3–4 m) |

↑Glycolysis, [F‐2,6‐P2] ↓[G‐6‐P], [glycogen], FAO |

↑Cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis ↓Hypoxia‐induced contractile inhibition in cardiomyocytes |

31 |

| I/R | ↔Insulin sensitivity | ↔Myocardial infarct size | |||

| AR‐null mice | C57BL/6 | Base line (14–16 wks old) | ↓Ejection fraction, slightly | 63 | |

| 2 wks post‐TAC (12–16 wks old) |

↑Lipid peroxidation‐derived aldehydes ↑Aldehyde‐modified proteins ↑Autophagy |

↑Pathological cardiac hypertrophy ↓Cardiac function |

|||

| Cardiac‐specific overexpression of human AR | C57BL/6 | Baseline (3 m) |

↔Glucose uptake ↔GLUT1, GLUT4, CPT1, AOX mRNA ↑SDH mRNA level |

Normal | 79 |

| Baseline (12 m) | ↓FA metabolism | ↑Cardiac dysfunction | |||

| I/R |

↓ mRNA levels of FA metabolism related genes ↑ROS |

↑Infarct size, apoptosis ↑Cardiac dysfunction |

|||

| PPARα−/− |

↑Glucose uptake/utilization ↑[fructose], [ceramide], ROS ↓FAO, PDK4 |

↑Apoptosis, fibrosis ↓Cardiac function |

|||

| G6PD‐deficient | C3H/HeJ | 3 m | Normal | 99 | |

| 9 m |

↑Oxidative stress ↓[Ca2+]i transport |

↓Cardiac function over time | |||

| 6 wks post‐TAC | ↓Superoxide production | Tendency to develop LV dilation | 100 | ||

| 17 wks post‐TAC (high fructose diet) | ↓Aconitase |

↑Pathological hypertrophy ↓Cardiac function |

|||

| 3 m post‐MI | ↑Oxidative stress |

↑LV dilation ↔Cardiac function, survival |

|||

| I/R | ↓Cellular glutathione (GST, GSH) | ↑I/R injury | 108 | ||

| Cardiac‐specific overexpression of HK2 | FVB/N | Baseline | ↓Oxygen consumption | Normal | 101 |

| Isoproterenol infusion (2–3 mo old) | ↑O‐GlcNAcylation | ↓Cardiac hypertrophy | |||

| Cardiac‐specific knockout of OGT | C57BL/6 | Baseline (4–5 wks) | ↑COX IV, HK, PFK, GLUT1 mRNA levels |

Perinatal death and heart failure ↑Apoptosis, fibrosis, ER stress ↑Cardiac hypertrophy |

133 |

| Cardiac‐specific het of OGT | C57BL/6 | Baseline (2–4 m) | Progressive cardiomyopathy | ||

| Inducible cardiac‐specific knockout of OGT | C57BL/6 | Baseline (<1 m) | ↑GAPDH mRNA level | Normal | 153, 158 |

| Baseline (1–3 m) | ↓Cardiac function over time | 34 | |||

| 2 and 4 wks post‐TAC |

↑TGFβ2 mRNA level ↓GATA4 |

↓Cardiac function | 134 | ||

| 5 d post‐MI | ↓PGC1‐α, PGC1‐β, CPT1, CPT2, MCAD, ATP‐5O, COXIV‐5B, GLUT1, GLUT4 mRNA levels | 158 | |||

| 4 wks post‐MI |

↑Apoptosis, fibrosis ↓Cardiac function |

||||

| Ventricular‐specific knockout of HIF1α | Baseline |

↓GLUT1, HK2, GPD1, GPAT, PPARγ mRNA levels ↑PPARα, PPARβ/δ mRNA levels ↑Mitochondrial‐related genes at mRNA levels ↑PGC1α, M‐CPT1, VDAC, SDHA ↑Repiratory function, DNA content, surface area of mitochondria ↓SERCA2, Ca2+ reuptake ↓ATP, phosphocreatine, lactate |

↓Contractile function, mild hypovascularity | 37, 38 | |

| 14 to 18 d post‐TAC |

↓TAG content ↓GAPDH, GPD1, GPAT activities |

↓Apoptosis ↓Pathological hypertrophy |

166 | ||

| Ventricular‐specific knockout of Vhlh | Baseline |

↑Glycolytic genes, GPD1, GPAT, PPARγ mRNA levels ↓PPARβ/δ mRNA level ↓Mitochondrial‐related genes at mRNA levels ↑HIF1α, PPARγ, FAT/CD36, GPAT ↓PGC1α, M‐CPT1, VDAC, SDHA ↓Repiratory function, DNA content, surface area of mitochondria |

Cardiac hypertrophy | 166 |

AOX indicates acyl‐CoA oxidase 1; AR, aldose reductase; ATP‐5O, ATP synthase subunit 5; COX 5B, cytochrome C oxidase subunit 5B; COX IV, cytochrome C oxidase subunit 4; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; FA, fatty acid; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; FAT/CD36, fatty acid translocase/cluster of differentiation 36; G6PD, glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; GATA4, GATA binding protein 4; GLUT1, glucose transporter type 1; GLUT4, glucose transporter type 4; GPAT, glycerol phosphate acyltransferase; GPD1, glycerol 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; HK2, hexokinase 2; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; LV, left ventricle; MCAD, medium chain acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase; MI, myocardial infarction; OGT, O‐GlcNAc transferase; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; PFK‐2, phosphofructokinase‐2; PGC1‐β, PPARγ coactivator 1 β; PGC1‐α, PPARγ coactivator 1 α; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SDH, sorbitol dehydrogenase; SDHA, succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A; SERCA2, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2; TAC, thoracic aortic constriction; TAG, triglyceride; TGFβ2, transforming growth factor β2; VDAC, voltage‐dependent anion channel.

Metabolic alterations in the heart for glycolysis, glucose oxidation, and FAO may vary depending on the animal models, experimental settings, stage and severity of cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction, and different pathological stimuli. Although evidence is mounting to support decreased FAO and increased glucose utilization, unchanged or elevated FAO and unchanged or decreased glycolysis have also been found in hypertrophied hearts.39 Angiotensin II induces cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction, along with preservation of FAO and glycolysis (slightly reduced, but not significant) and decreases in glucose and lactate oxidation.40 Here, glycolysis rate may be modulated by the sustained/high FAO rate through PFK1 inhibition41 and development of cardiac insulin resistance. Angiotensin II has been found to induce insulin resistance,42 which may lead to impairment of insulin‐dependent glucose uptake and glycolysis. Consistently, the defect in insulin‐induced GLUT4 translocation may cause reduction of glycolysis in abdominal aortic constriction hearts.39 Under insulin resistance, metabolic flexibility of utilizing FAs and glucose is impaired. Therefore, the uncoordinated regulation of glucose oxidation, glycolysis, and FAO may result in ATP deficit and development of heart failure.

Under physiological context, exercise may acutely suppress glycolysis and PFK activity, which are then augmented in the recovery stage.26 It is implied that changes in glucose utilization caused by regular exercise are important for maintaining mitochondrial health and physiological cardiac growth, whereas a consistently high rate of glycolysis induces pathological hypertrophy.26, 27

Glycolysis in the Ischemic and Failing Heart

Consequences of cardiac ischemia include poor oxygen supply and inadequate washout of metabolic wastes.43 Lack of sufficient oxygen dampens cardiomyocyte capacity to break down FAs, which, in turn, decreases the level of cellular citrate and indirectly activates glucose uptake and glycolysis. As a result, glycolytic flux increases during ischemia.43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 It has been shown that glucose uptake increases in mild ischemia, whereas it may actually decrease in severe ischemia (near‐complete blockage of coronary flow).43 When the coronary flow rate progressively reduces, modest ischemia will become moderate and then severe. During this transition, glycolysis produces ATP and maintains ionic homeostasis, providing a beneficial effect. However, under severe ischemia, glycolysis may be more harmful than beneficial. Lack of washout can lead to deleterious effects overshadowing the benefit of generation of anaerobic ATP. Buildup of intracellular protons attributed to poor perfusion may inhibit glycolysis in a feedback manner.43, 45 Further detrimental effects may include disruption of ionic homeostasis by debilitating the Na+, Ca2+ efflux capacity of Na+/K+ ATPase and Ca2+ ATPase,45 thereby impairing contractile function. In addition, pyruvate from glycolysis forms lactate rather than entering pyruvate oxidation, which may lead to an even higher level of lactate and lower rate of glucose oxidation. Collectively, in a manner similar to that proposed in pathological cardiac hypertrophy, increased glycolysis may be accompanied by uncoupling of glucose oxidation and elevation of lactate and proton levels, which, together, contribute to myocardial injury.

Restoration after ischemia (ischemia/reperfusion; I/R) is the most effective approach to mitigate cardiac damage and improve clinical outcomes.49 However, during reperfusion, the glycolytic rate is still high without a parallel increase in glucose oxidation, resulting in continuous reduction in cardiac efficiency.44, 45, 46, 47, 48 Moreover, I/R restores extracellular pH and induces Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+ exchange, which may adversely cause profound intracellular overload of Na+ and Ca2+. Therefore, ionic imbalance is persistent during reperfusion that is considered a culprit for impaired contractility.46 During reperfusion, the increase in FAO is accompanied by a decrease in glucose oxidation, which causes further uncoupling between glucose oxidation and glycolysis.50, 51

In congestive heart failure, the rate of FA utilization is induced whereas the glucose utilization rate is suppressed.52, 53 The high level of plasma norepinephrine may account for the elevated plasma free FAs through lipolysis and re‐esterification, which, in turn, causes the decrement in glucose oxidation.54 Suppression of FAO may represent a promising strategy to improve myocardial energy homeostasis.

In line with aforementioned animal studies, the uncoupling between glycolysis and glucose oxidation has also been discovered in human failing hearts.55, 56 Furthermore, high‐salt‐diet–induced heart failure with preserved ejection fraction shows a progressive increase in glycolysis along with the development of hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction without changes in glucose oxidation. The mismatch between glycolysis and glucose oxidation in the early stage may cause the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.56 Restoration of the coupling may be a potential therapeutic means for treatment of heart failure.44, 45, 46, 56

It is worth noting that the reduction of FAO is not observed in onset of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, but only at the later stage.56 In support of this, the rate of FA utilization, including FAO and lipid incorporation, is inversely correlated with degree of cardiac dysfunction in chronically infarcted rat hearts.57 FAO and glucose oxidation are unaltered in dogs with moderate coronary microembolization‐induced heart failure.58 Furthermore, substrate utilization (eg, FAO) in patients with moderate heart failure is similar to healthy controls.59 These data suggest a significant contribution of the reduced FA utilization to the late stage of heart failure. The difference in metabolic remodeling is likely determined by the type and severity of cardiac disease. Further studies are warranted to dissect the underlying mechanisms for future clinical applications.

Polyol Pathway

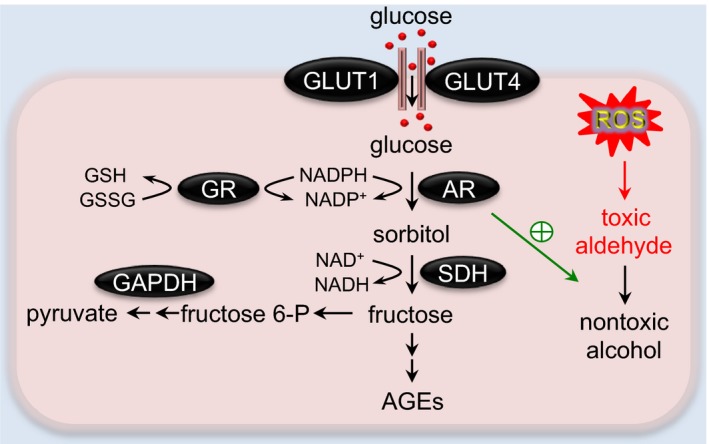

The polyol pathway consists of 2 enzymatic steps (Figure 3). The first reaction is controlled by aldose reductase (AR) for reduction of glucose to sorbitol. The second involves the action of sorbitol dehydrogenase to oxidize sorbitol to fructose. Under euglycemic conditions, <3% of glucose is utilized by the polyol pathway, whereas >30% of glucose is metabolized through this process in the intact rabbit lens under hyperglycemia.60, 61 In the heart, however, the metabolic rate through the polyol pathway remains undefined. AR and sorbitol are known to maintain osmotic balance by regulating the volume and intracellular environment of renal cells in response to alterations of external osmolality.62 Under hyperosmotic conditions, AR is induced in rat kidney mesangial cells, Chinese hamster ovary cells,63 JS1 Schwann cells,64 and rat cardiomyocytes.65 Additionally, overwhelming evidence suggests that AR may act as an antioxidant enzyme.66, 67 Under high oxidative stress conditions, such as vascular inflammation,68, 69 ischemia,70 iron overload,71 and alcoholic liver disease,72 AR is elevated. At the functional level, induction of AR displays cytoprotection against oxidative stress in the Chinese hamster fibroblast cell line.73 Moreover, AR may regulate other glucose metabolic pathways such as glycolysis and glucose oxidation.

Figure 3.

The polyol pathway in the heart. In the polyol pathway, aldose reductase (AR) converts glucose to sorbitol, which is subsequently oxidized to fructose by sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH). AR also acts as an antioxidant enzyme by catalyzing toxic aldehyde to nontoxic alcohol. AGEs indicates advanced glycation end products; fructose 6‐P, fructose 6‐phosphate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; GLUT, glucose transporter; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Polyol Pathway in the Hypertrophic Heart

Limited studies have been directed to dissect the role of polyol pathway in development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Recently, it has been reported that cardiac AR expression28 and its products (fructose and sorbitol)74 are induced in hypertrophied hearts and loss of AR leads to more‐profound hypertrophic growth and cardiac dysfunction.28 AR has been shown to hold the activity of detoxification of reactive aldehydes generated by lipid peroxidation. AR deficiency in hypertrophied hearts may therefore impair reactive aldehydes removal, resulting in elevation of aldehyde‐modified proteins such as 4‐hydroxynonenal (HNE)‐protein and acrolein‐protein adducts. These modified proteins participate in ATP production, protein folding, and autophagy.28 Autophagy in the early stage of hypertrophic growth is adaptive; however, excessive autophagy may induce maladaptive cardiac remodeling.75 Acute increase of AR in cardiac hypertrophy may therefore serve as an adaptive defensive response to detoxify aldehydes and govern autophagy.28 However, further studies are required for better understanding of the mechanistic insights by which the polyol pathway regulates cardiac pathological remodeling.

Polyol Pathway in the Ischemic and Failing Heart

AR functions as an antioxidant enzyme in protecting hearts and arteries from the toxic effects of lipid peroxidation products such as HNE and reactive aldehydes.61, 69, 76 Specifically, the generation of nitric oxide and activation of protein kinase C are required for the action of AR in the late phase of ischemic preconditioning, which consequently diminishes the injury caused by lipid peroxidation products.70 Reduction of AR expression and activity in dogs’ failing hearts results in abnormal lipid‐peroxidation–derived aldehyde metabolism and contributes to the excessive buildup of reactive aldehydes, which may amplify chronic oxidative stress.77

Although ample findings support a beneficial effect of the polyol pathway during ischemia, some studies have shown its contribution to the vulnerability of cardiovascular complications in diabetes mellitus,78, 79, 80, 81, 82 ischemia,29, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88 and aging.89 AR activation has been observed in ischemic hearts, which may exacerbate cardiac damage after I/R and cause cardiac dysfunction in aging mice.29 Here, AR may drive the conversion of glucose to fructose and diminish FA utilization.29 Additionally, AR may exacerbate I/R injury by impairment of mitochondrial membrane function through inducing oxidative stress (ie increase in malondialdehyde contents and decrease in mitochondrial antioxidant manganese superoxide dismutase activity).87

Moreover, inhibition of AR shows cardioprotection in diabetic79, 80, 82 and ischemic mice.83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 90 The anti‐ischemic effects likely involve improving cardiac energy metabolism83, 90 and contractile function,86, 88 suppressing oxidative stress,84, 85, 88, 90, 91 and preserving mitochondrial function.87 Indeed, polyol pathway inhibition is linked to a higher rate of glycolysis and more‐prominent ATP generation.92 Elevated glycolysis and reduction of oxidative stress by AR inhibition have been proposed to cause the reduction of NADH/NAD+ by attenuation of NAD+ use through sorbitol dehydrogenase; hence, NAD+ is preserved for glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase in glycolysis.84, 93 Additional evidence for the antioxidant effect of AR inhibition is that it may reserve NADPH to fuel the glutathione reductase pathway. Inhibition of AR alleviates I/R injury along with the decrease in reactive oxygen species (ROS), malondialdehyde,91 and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, the by‐product of lipid peroxidation.85 Furthermore, AR inhibitor may attenuate elevation of Na+ and Ca2+ during I/R. This effect has been explained, in part, by induction of sodium and calcium efflux resulting from activation of Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by the AR inhibitor.94 Additionally, inhibition of AR restores the activity of Ca2+ATPase by dampening tyrosine nitration and normalizing S‐glutathionylation of this pump.88 Ectopic lipid accumulation in the heart may contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.95, 96, 97 AR promotes lipid accumulation in the heart by competing with histone deacetylase 3 for corepressor complex interaction, resulting in free histone deacetylase 3 for degradation. This action leads to downregulation of the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ and retinoic acid receptor pathways and, consequently, lipid accumulation.98

The role of the polyol pathway on redox stress in diabetes mellitus is emerging.99 A reduced content of NADPH has been found in diabetic lung100 and pancreas.101 The usage of NAPDH by AR may reduce NAPDH availability for glutathione reductase to maintain reduced glutathione and may induce superoxide generation. Moreover, NADH level is elevated in chronic hyperglycemia that involves reduced glycolysis,92 impairment of mitochondrial function, and augmented ROS generation.102 This increase of NADH may be associated with the polyol pathway. The usage of NAD+ by sorbitol dehydrogenase, the second step in the polyol pathway, can reduce the content of NAD+ for glycolysis and produce NADH. In addition, fructose produced by the polyol pathway is converted into fructose 3‐phosphate and leads to generation of 3‐deoxyglucosone, a precursor for advance glycation end product formation. AR may therefore catalyze advance glycation end product production and induce oxidative stress. Excessive accumulation of advance glycation end products contributes to the pathogenesis of diabetic complications.103, 104

It is worth mentioning that the osmotic consequence of activated polyol pathway in diabetes mellitus is one of the potential pathological mechanisms. Accumulation of sorbitol causes hyperosmotic stress, which is associated with development of diabetic cataract,105 reduced Na+/K+ ATPase activity, elevated oxidative stress,106 and ATP deficit.107 In cultured rat cardiomyocytes, AR not only contributes to the depletion of glutathione content, but also hyperosmotic stress‐induced apoptosis.65 Taken together, it is possible that the role of the polyol pathway or AR in the heart depends on the context of pathological cardiac disease. More work remains to be done to understand how the polyol pathway senses the signals to defend or exacerbate cardiac injury under different pathological contexts.

Pentose Phosphate Pathway

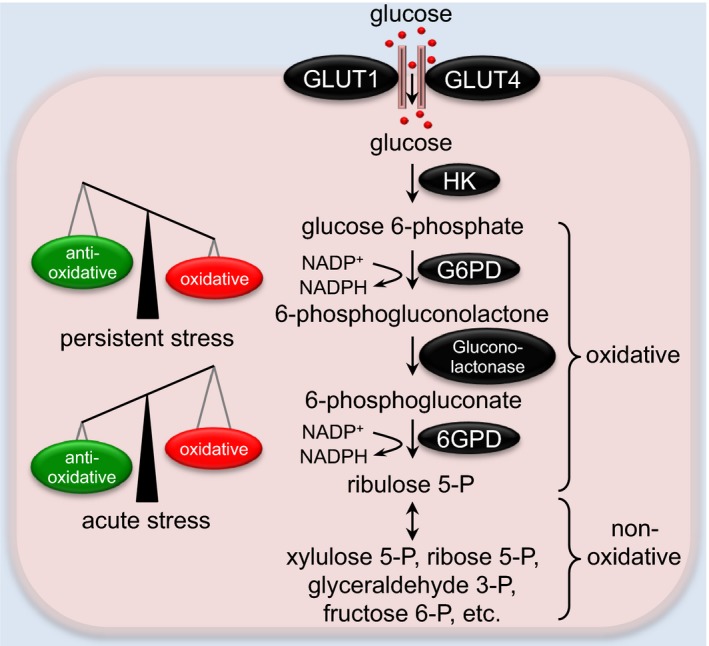

There are 2 branches in the PPP: oxidative and nonoxidative. The oxidative PPP generates NAPDH and ribulose 5‐phosphate (Figure 4). On the other hand, the nonoxidative branch metabolizes ribulose 5‐phosphate to 5‐carbon sugars for nucleotide biosynthesis or generation of intermediates for the glycolytic pathway (ie, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate and fructose 6‐phosphate). The nonoxidative reactions are reversible, which may regenerate ribulose 5‐phosphate from glycolytic intermediates. The oxidative PPP is a critical source of cytosolic NADPH that maintains reduced glutathione levels.30 Moreover, NAPDH contributes to the generation of cytosolic ROS through activation of NADPH oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Thus, the PPP may play a dual role in the regulation of redox balance.6

Figure 4.

The pentose phosphate pathway in the heart. The oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) generates NADPH and ribulose 5‐phoshpate (ribulose 5‐P), which are mainly used for anabolism. The nonoxidative phase of PPP stimulates the interconversion of 5‐carbon sugars with a series of reversible reactions. Whereas acute activation of the PPP confers cardioprotection against oxidative stress, persistent upregulation of the PPP may exacerbate oxidative damage and contribute to cardiomyopathies. 6GPD indicates 6‐phosphogluconate dehydrogenase; fructose 6‐P, fructose 6‐phosphate; G6PD, glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase; GLUT, glucose transporter; glyceraldehyde 3‐P, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate; HK, hexokinase; ribose 5‐P, ribose 5‐phosphate; xylulose 5‐P, xylulose 5‐phosphate.

PPP in the Hypertrophic Heart

The role of the PPP in maintenance of cytosolic redox homeostasis has been reported from studies on glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), the rate‐limiting enzyme of the PPP. In response to cellular oxidative stress, G6PD activity is rapidly increased with corresponding translocation from the cytosol to the cell‐surface membrane.30 At both in vitro and in vivo levels, G6PD shows a cardioprotective effect against free radical injury whereas depletion of G6PD causes adversity on cardiac contraction.30 In addition, G6PD‐deficient mice display progressive pathological structural modeling and develop moderate hypertrophy at 9 months of age.30 Cardiac oxidative stress in these animals is augmented in response to MI or pressure overload.31 Glucose phosphorylation by hexokinase is the first step to initiate glucose utilization. Overexpression of hexokinase 2 shows an antihypertrophic effect in both phenylephrine‐triggered hypertrophic cardiomyocytes and isoproterenol‐induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice.33 Importantly, the beneficial effect of hexokinase 2 is associated with an elevated G6PD activity, leading to enhanced glucose utilization through the PPP and attenuated ROS accumulation.33 Taken together, increase in G6PD under various pathological conditions may serve as a defensive mechanism to protect cardiac myocytes against injury.

PPP in the Ischemic and Failing Heart

A detrimental effect of the oxidative PPP has been found in cardiac I/R.108 During acute I/R, the oxidative PPP‐derived NAPDH is mostly metabolized by NAPDH oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Inhibition of the oxidative PPP as well as NAPDH oxidase/nitric oxide synthase is cardioprotective against I/R‐induced creatinine kinase release (an index of cardiac injury). Furthermore, an increase in G6PD expression and activity has been observed in both human and canine heart failure.109, 110 Importantly, the PPP‐derived NAPDH is also elevated and fuels superoxide production in failing hearts. Collectively, these observations strongly suggest that the increased availability of NAPDH, presumably through the oxidative PPP in failing hearts, may have a more‐dominant effect on stimulating superoxide generation compared with its antioxidant role. Under the condition of severe heart failure, the glycolytic pathway is depressed.111, 112 It is possible that a larger fraction of glucose entering cardiomyocytes triggers upregulation of the PPP. Interestingly, elevation of blood glucose after meals rapidly boosts the generation of ROS in failing hearts, but does not have an effect in normal hearts. This repeated physiological effect likely adds more oxidative stress to the failing heart.113 Indeed, inhibition of the oxidative PPP during acute hyperglycemia enhances cardiac glucose oxidation, oxygen consumption, and cardiac work and prevents oxidative stress in failing hearts.113 This inhibition may, however, be partial given that complete inhibition of oxidative PPP may cause an adverse effect, as observed in isolated adult cardiomyocytes.30 The partial inhibition is sufficient to maintain a proper balance of reduced glutathione for the antioxidant system while blunting the harmful, excessive level of NAPDH. It is, however, not clear whether sustained suppression of the oxidative PPP at the early stage of heart failure development would mitigate oxidative stress and dampen disease progression. It seems that in the onset of cardiac remodeling, the PPP acts as an adaptive response to accommodate cardiac stress by maintaining redox homeostasis.32 However, under persistent stress, the PPP may contribute to the pathogenesis of heart failure. The intracellular pathways mediating PPP actions remain to be fully characterized.

The important role of the PPP in maintaining proper intracellular redox states has also been revealed in cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs).114 The activities of key enzymes of the PPP (G6PD and transketolase) are reduced in CPCs of diabetic mice, leading to accumulation of glucose metabolic intermediates and execution of apoptosis. Importantly, upregulation of the PPP by benfotiamine treatment in diabetic mice restores G6PD and transketolase activities, decreases ROS and advance glycation end product accumulation, and prevents CPCs from cell demise. Consequently, development of cardiomyopathy and postischemic heart failure in diabetic mice is attenuated.114 The beneficial effect of the PPP in progression of heart failure has also been shown in Dahl salt‐sensitive rats.115 Indeed, dichloroacetate treatment induces the PPP, which is involved in prevention of left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure.

At the mechanistic level, decrease of the PPP in CPCs may be attributed to upregulation of glycolysis and glycerolipid biosynthesis.116 Salabei et al show that 6‐phosphofructo‐2‐kinase/fructose 2,6‐P2 bisphosphatase 3, an isoform of PFK2, is significantly elevated in diabetic CPCs, which may promote usage of 3‐carbon intermediates of glycolysis for glycerolipid production and consequently suppress glucose utilized for the PPP. This metabolic imbalance may lead to impairments in mitochondrial function and CPC proliferation. In agreement, the metabolite profiles of ex vivo rodent hearts perfused with glucose117 or PFK2 mutant‐expressing cardiomyocytes118 show that PFK coordinately regulates glycolysis and other ancillary glucose metabolic pathways, including the PPP, the HBP, glycerolipid biosynthesis, and the polyol pathway. Activation of PFK causes a disproportionate distribution of glucose flux by directly limiting intermediates of glycolysis for ancillary glucose metabolic pathways and indirectly regulating the cataplerotic activity of mitochondria.118

Along these lines, decrease in the PPP may also limit proliferation of fetal cardiomyocytes under diabetic conditions. Ribulose 5‐phosphate is an important intermediate of the PPP pathway,119 which can be used for glucose production, glycolysis, pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis, purine nucleotide synthesis, and ATP generation. Recently, it has been shown that cardiomyocyte maturation is induced by nucleotide deprivation, not by cell‐cycle blockage.120 Importantly, the role of nucleotide biosynthesis by the PPP is indicated as a primary determinant of the promitotic effect of glucose. These findings may provide certain mechanistic explanations for congenital heart disease in gestational diabetes mellitus, in which the high blood glucose level may suppress fetal cardiomyocytes proliferation. Therefore, targeting the PPP to control the proliferation of CPCs and cardiomyocytes may represent a promising approach for cardiac regeneration and treatment of diabetes mellitus–related cardiac disease.

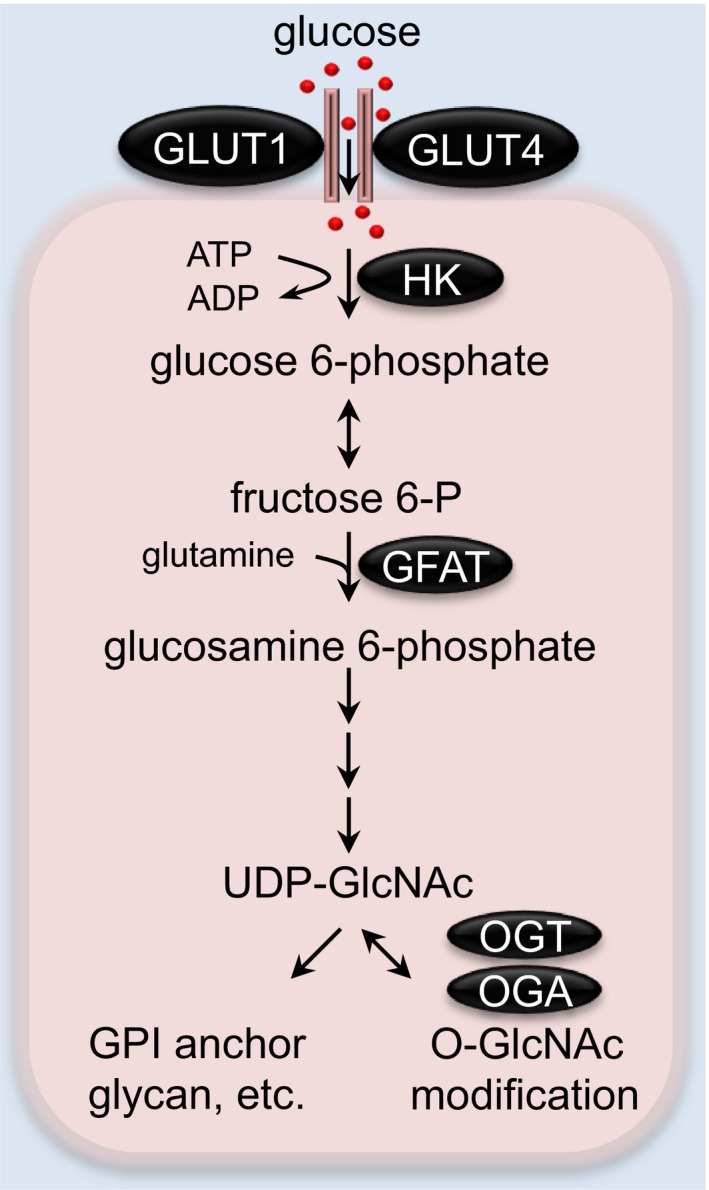

Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway

At baseline, 2% to 5% of glucose is metabolized by the HBP, which has been found in adipocytes and skeletal muscle.121, 122, 123 This contribution can be significantly larger under stress conditions.124 The HBP is regulated by both nutrient inputs (glucose and glucosamine) and the rate‐limiting enzyme, glutamine:fructose 6‐phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT; Figure 5). GFAT converts fructose 6‐phosphate to glucosamine 6‐phosphate and eventually generates the final product, uridine diphosphate N‐acetylglucosamine (UDP‐GlcNAc). UDP‐GlcNAc serves as a substrate for the synthesis of proteoglycan, hyaluronan, glycolipid, glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, and N‐glycan. Additionally, UDP‐GlcNAc is used for O‐GlcNAcylation, a prominent posttranslational modification of O‐linked β‐N‐acetylglucosamine (O‐GlcNAc).125, 126, 127, 128 The 2 key enzymes of O‐GlcNAcylation are O‐GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O‐GlcNAcase, which add the GlcNAc moiety donated from UDP‐GlcNAc to, and remove from, target proteins at the Ser/Thr amino acid residues, respectively. This dynamic process plays a critical role in sensing cellular stressors, cell‐cycle alterations, and nutrient levels, which has been implicated in the pathophysiology of various heart diseases.129, 130, 131

Figure 5.

The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) in the heart. The rate‐limiting enzyme of the HBP, GFAT, converts fructose 6‐P and glutamine to glucosamine 6‐phosphate, which is used to generate the final product, UDP‐GlcNAc. UDP‐GlcNAc is a substrate for various biosynthetic pathways, including glycan synthesis, glycerolipid production, etc. UDP‐GlcNAc is also used for a prominent posttranslational protein modification on Ser/Thr sites by O‐GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which is counteracted by O‐GlcNAcase (OGA) to catalyze the removal of O‐GlcNAc. GFAT indicates glutamine:fructose 6‐phosphate amidotransferase; GLUT, glucose transporter; HK, hexokinase; UDP‐GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N‐acetylglucosamine.

HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation in the Hypertrophic Heart

Previous studies have shown that the HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation are activated during cardiac hypertrophy development. Indeed, pressure overload induces mRNA expression of GFAT2 and OGT and increases cardiac UDP‐GlcNAc levels.132, 133 Correspondingly, O‐GlcNAc posttranslational modification on cardiac proteins is augmented.133, 134, 135, 136 Moreover, the increase in O‐GlcNAcylation has been revealed in hearts of hypertensive rats and aortic stenosis patients.133 Similarly, cardiomyocytes treated with hypertrophic stimuli (ie, phenylephrine, angiotensin II) show increases in O‐GlcNAc levels whereas HBP inhibition causes a decrease in O‐GlcNAc levels and counteracts the prohypertrophic effect.135, 137 These findings suggest that O‐GlcNAcylation plays an important role in pathological cardiac hypertrophy, and inhibition of O‐GlcNAcylation blunts hypertrophy progression. However, long‐term reduction of O‐GlcNAc levels is detrimental and causes cardiomyopathy.34, 36

Furthermore, diabetes mellitus is associated with cardiac hypertrophy and elevation of O‐GlcNAcylation.137, 138, 139, 140 The increase of O‐GlcNAcylation is accompanied by impaired cardiac hypertrophy in db/db diabetic hearts along with augmentation of B‐cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl‐2)‐induced cardiomyocyte death, thereby accelerating the progression to heart failure.137 In both high‐glucose–treated cardiac myocytes and hypertrophic myocardium of streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats, O‐GlcNAc levels, extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) activity, but not p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase or c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK) activity, and cyclin D2 expression are upregulated.139 Accordingly, inhibition of O‐GlcNAcylation blocks activation of ERK1/2, hypertrophic growth, and cyclin D2 expression.139 ERK1/2 promotes compensative cardiac hypertrophy, whereas p38 and JNK are involved in development of cardiomyopathy.141 In this context, O‐GlcNAcylation may contribute to an adaptive form of cardiac hypertrophic growth.

The role of O‐GlcNAcylation in cardiac hypertrophy is complex and depends on the type of hypertrophic growth.33 It is well known that calcineurin‐NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) signaling governs cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload.142 O‐GlcNAc modification on NFAT is required for its translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus, where NFAT stimulates the transcription of various hypertrophic genes. In other words, O‐GlcNAc may contribute to cardiac hypertrophy through NFAT activation.143 Consistently, inhibition of O‐GlcNAcylation dampens NFAT‐induced cardiac hypertrophic growth. More recently, the antihypertrophic action of AMP‐activated protein kinase has been firmly associated with reduction of O‐GlcNAcylation.144 Importantly, O‐GlcNAcylation of troponin T is one of the downstream targets of AMP‐activated protein kinase in cardiac hypertrophic growth.144 There are several additional O‐GlcNAcylated proteins from cardiac myofilaments, including cardiac myosin heavy chain, α‐sarcomeric actin, myosin light chain 1 and 2, and troponin I.145 These key contractile proteins are O‐GlcNAcylated at phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated sites. For example, myosin light chain 1 is O‐GlcNAcylated at Thr 93/Thr 164, which are different from phosphorylation sites at Thr 69 and Ser 200.145, 146 However, the O‐GlcNAc residues in cardiac troponin I and myosin light chain 2 lie on the phosphorylation sites Ser 150 and Ser 15, respectively.145 At the functional level, O‐GlcNAcylation of key contractile proteins may inhibit protein‐protein interactions, resulting in reduction of calcium sensitivity, and thereby modulating contractile function.147

Under the physiological context, decreases in HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation have been shown in hearts of swim‐trained mice.148 Additionally, in treadmill running mice, cytosolic O‐GlcNAcylated proteins are decreased after 15 minutes of exercise, whereas there is no change of O‐GlcNAcylation 30 minutes later.149 Mechanistically, this acute response leads to removal of O‐GlcNAc groups from OGT, resulting in dissociation of OGT and histone deacetylases from the repressor element 1–silencing transcription factor chromatin repressor and triggering physiological hypertrophic growth.149 Interestingly, swim training normalizes elevated O‐GlcNAcylation in hearts of streptozotocin‐induced diabetic mice by increasing O‐GlcNAcase expression and activity; however, there is no change in OGT.150 Collectively, these findings highlight the role of O‐GlcNAcylation in physiological cardiac hypertrophic growth.

HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation in the Ischemic and Failing Heart

In response to various cellular stresses, the HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation increase rapidly.151, 152, 153 Previous studies have shown that elevated O‐GlcNAcylation confers strong cardioprotection in I/R.75, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159 This is partly explained by increasing O‐GlcNAcylated voltage‐dependent anion channels and reducing sensitivity to mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, thereby increasing mitochondrial tolerance to oxidative stress.154, 160 In addition, induction of the HBP and O‐GlcNAcylation by glucosamine promotes mitochondrial Bcl‐2 translocation, which is associated with restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential and cardioprotection.155, 157 Moreover, protection of increased O‐GlcNAcylation has been proposed to attribute to depletion of the calcium‐induced stress response.158, 159 Recently, elevated O‐GlcNAcylation and OGT expression along with reduction of OGA have been reported in infarction‐induced heart failure in mice.35 Cardiomyocyte‐specific deletion of OGT causes significant reduction in O‐GlcNAcylation, which provokes heart failure after MI and impairs cardiac compensatory potential during heart failure development.35 Together, mounting evidence suggests that acute increase of O‐GlcNAcylation is beneficial in the heart against various stressors.

As a metabolic and stress sensor, O‐GlcNAcylation is altered in several chronic disease conditions161 including heart disease.140, 153, 162 Induction of O‐GlcNAcylation has been observed in hypertensive hearts,133, 163 diabetic hearts,164, 165 chronically hypertrophied hearts, and failing hearts.133 Studies have shown that this increase may contribute to contractile and mitochondrial dysfunction.162 Consistently, suppression of O‐GlcNAcylation by overexpression of O‐GlcNAcase normalizes cardiac O‐GlcNAcylation levels and improves calcium handling and cardiac contractility in the diabetic heart.166 Thus, it is speculated that the acute increase in O‐GlcNAcylation is an adaptive response to protect the heart from injury, whereas prolonged, persistent activation is maladaptive and contributes to cardiac dysfunction.

Emerging evidence has shed light on the upstream regulators of the HBP. We have shown that GFAT1 is a direct target of X‐box binding protein 1 (XBP1s), a key transcriptional factor of the unfolded protein response (UPR).124 Consistently, overexpression of XBP1s in cardiomyocytes promotes HBP activity, resulting in elevation of UDP‐GlcNAc levels and O‐GlcNAcylation. Notably, I/R activates XBP1s, which couples the UPR to the HBP to protect the heart from reperfusion injury.124 More recently, another UPR effector, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), has been demonstrated as a direct regulator of GFAT1 expression.167 Deprivation of amino acids or glucose activates the general control nonderepressible 2/eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha/ATF4 pathway and leads to increases in GFAT1 and O‐GlcNAcylation.167 Taken together, the HBP and cellular O‐GlcNAcylation may serve as a buffering mechanism for the UPR to accommodate fluctuations in the cell in response to intra‐ or extracellular cues.

Other Glucose Metabolic Pathways

Glycerolipid Synthetic Pathway

Fructose 1,6‐bisphosphate, an intermediate of glycolysis, can be converted to glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Dihydroxyacetone phosphate may then be reduced to glycerol 3‐phosphate (glycerol 3‐P) by glycerol 3‐P dehydrogenase. Glycerol 3‐P is derived from not only glucose through glycolysis, but also glycerol through the action of glycerol kinase, which serves as a substrate for acylation by glycerol 3‐P acyltransferase, the first step of the glycerolipid synthetic pathway (GLP).

Although little is known about the role of the GLP in cardiomyopathy, the activities of glycerol 3‐P dehydrogenase and glycerol 3‐P acyltransferase, 2 crucial enzymes of the GLP, are elevated in hypertrophied hearts.37 Studies show that the GLP is, at least in part, associated with regulation of glycolysis by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF‐1α)37, 38 and PFK.116 Emerging evidence indicates that HIF1α and peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ are elevated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Interestingly, induction of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ expression by hypertrophy is HIF1α dependent, which subsequently induces glycerol 3‐P acyltransferase. Therefore, hypertrophy‐activated HIF1α triggers the synthesis of lipids by coregulation of glycolysis and GLP. At the functional level, HIF1α‐mediated cardiac lipid accumulation leads to cell death through the HIF1α/peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ/octamer 1/growth arrest and DNA‐damage‐inducible α axis. Suppression of HIF1α therefore protects the heart from hypertrophy‐induced cardiac dysfunction. This cardioprotection may be attributed to, at least partly, the increases of cAMP response element‐binding protein activity and sarco/ER Ca2+‐ATPase 2A expression.37 Additionally, activation of PFK in diabetic CPCs induces glycolysis and promotes the conversion of the 3‐carbon intermediates of glycolysis to GLP. As a consequence, the GLP may initiate an adipogenic program in CPCs and contribute to lipid accumulation.116 In cardiomyocytes, low glycolytic activity may reduce glycerophospholipid synthesis at the glycerol 3‐P dehydrogenase 1–committed step. In contrast, high glycolytic activity could promote phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis while attenuating glucose‐derived carbon incorporation into the FA chains of phosphatidylinositol and triacylglycerols.118 Taken together, these findings suggest that there is a concerted regulation of glycolysis and GLP in response to stress‐induced pathological hypertrophy. Further work is needed to dissect the direct link of GLP with pathological cardiac remodeling.

Serine Biosynthetic Pathway

Serine biosynthesis is another ancillary glucose metabolic pathway to use glyceraldehyde 3‐P to generate serine in 3 steps by phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, phosphoserine aminotransferase 1, and phosphoserine phosphatase. Serine can be used to synthesize amino acids glycine and cysteine, which are biosynthetic precursors of glutathione, purine, and porphyrin. Serine may also constitute components of sphingolipids and phospholipids. In addition, serine provides the 1‐carbon units to the 1‐carbon metabolism pathway for purine, thymidine, methionine, and 5‐adenosylmethionine syntheses.168 Because of the requirement of serine in the synthesis of variously important molecules, it is proposed as a central metabolic regulator of cell function, growth, and survival.169, 170 There are extensive studies on the role of serine biosynthesis in cancer168, 171, 172 whereas the importance in cardiac disease is poorly understood. Recently, activation of serine and the 1‐carbon metabolism pathway induced by CnAβ1, a calcineurin isoform, shows a protective effect in the heart under pressure overload.173 Induction of this pathway leads to increased ATP synthesis and reduced glutathione levels, improved cardiac contraction, and cardioprotection against oxidative injury. Further work is warranted to delineate the role of serine biosynthesis in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology.

Glycogen Metabolic Pathways

Glucose can be converted to glycogen, a multibranched polymer of glucose, for storage through the glycogen synthesis pathway. Cardiac glycogen serves as a significant source of glucose to support high energy demand not only in the normal heart, but also in the hypertrophied heart during normal aerobic perfusion174, 175 or under low‐flow ischemia.176, 177 In the hypertrophied heart, glycolysis using glycogen‐derived glucose is not altered compared with that in the normal heart whereas glycolysis with exogenous glucose is increased.175 Also, myocardial glycogen turnover occurs in both normal and hypertrophied hearts. During mild/moderate low‐flow ischemia, rates of glycolysis as well as glucose oxidation are not different in the hypertrophied heart compare with those in the normal heart.176 The contribution of glycogen metabolism in the hypertrophied heart during normal aerobic flow or mild/moderate low‐flow ischemia is similar to those in the normal heart. However, during severe low‐flow ischemia, rates of glycolysis from both exogenous glucose and glycogen are augmented in the hypertrophied heart, along with the increase in glycogen turnover.

In ischemic preconditioning, reduced glycogenolysis and cardiac glycogen content may decrease glucose availability for glycolysis, lower acid production, and protect the heart from ischemic injury.178 In I/R, elevation in glycogen synthesis lowers the source of glucose for glycolysis, decreases acid generation, and prevents Ca2+ overload.179 In rats under fasting conditions, cardiac glycogen content is elevated, which protects the heart from ischemic damage. The increased glycogen utilization may serve as a critical source of ATP to maintain calcium homeostasis. On the other hand, fed rats similarly show elevation in cardiac glycogen content. However, the increase of circulating insulin limits glycogen utilization, which leads to an increase in lactate production and more‐pronounced cardiac injury by ischemia.180 Taken together, understanding of the fundamental bases for glycogen homeostasis in cardiac pathophysiology is essential to harness the knowledge for therapeutic gain.

Pharmacological Agents to Modulate Metabolic Remodeling

There are a number of potential metabolic targets for treatment of heart diseases. The central goals of metabolic therapies are maintenance of flexibility in substrate use and the capacity of cardiac oxidative metabolism, which may, in turn, promote myocardial energy efficiency and improve cardiac function.181 FAO is a major contributor to energy production in the normal heart; however, FAO is less energy efficient than glucose oxidation because of its higher oxygen consumption. Therefore, optimizing cardiac energy metabolism by inhibiting FAO and inducing glucose oxidation may be a potential approach to treat heart failure.45, 182

Inhibiting FA Uptake

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) is a key enzyme for FA uptake into mitochondria. Direct modulation of FAO using carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 inhibitors (eg, etomoxir and perhexiline) shows beneficial effects in treatment of heart failure. Etomoxir inhibits carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 and suppresses FAO, along with augmented glucose oxidation, resulting in cardioprotection from ischemia.183 Treatment of etomoxir also improves myocardial performance of hypertrophied hearts following pressure overload184 and slows the progression from compensatory to decompensated cardiac hypertrophy, in part, by inducing sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport.185 Both etomoxir and perhexiline show beneficial effects on the improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction of patients with chronic heart failure.186, 187 However, use of these agents for heart failure is limited (perhexiline) or even terminated (etomoxir) because of hepatotoxic side effects.

Suppressing FA β‐oxidation

Trimetazidine suppresses the rate of FAO by inhibiting 3 ketotacyl‐CoA thiolase, the last enzyme in FAO, concomitant with increased glucose oxidation. Clinically, trimetazidine is used as an antianginal agent in the treatment for stable angina. It improves left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with either ischemic cardiomyopathy188 or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.189 Especially, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy treatment with trimetazidine shows reduced FAO as well as increased insulin sensitivity. In addition, the improvement of ejection fraction by trimetazidine is more dramatic when used together with β‐blockers, suggesting an additive effect of trimetazidine and β‐adrenoceptor antagonism.189

Reducing Circulating FA

Glucose‐insulin‐potassium (GIK) increases glycolysis, reduces levels of circulating free FA, and hence decreases FAO. GIK had beneficial effects in patients with MI, shown by reduction of infarct size and mortality.190, 191, 192, 193, 194 However, effects of GIK are not always consistent. Some clinical studies have reported that GIK did not improve survival and decrease cardiac events in patients with acute MI.195, 196 Clinical use of GIK remains to be fully validated.

Increasing Glucose Oxidation

Activation of glucose oxidation is an effective way to provide a more energy‐efficient substrate, which may show beneficial effects on improving cardiac function. Dichloroacetate (DCA) enhances glucose oxidation by activating the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which is associated with improvement of coupling between glycolysis and glucose oxidation in the heart after ischemia197 or pressure overload.198 Likewise, DCA promotes myocardial efficiency in patients with coronary artery disease.199 The beneficial effects of DCA in high‐salt‐diet–induced congestive heart failure in Dahl salt‐sensitive rats are associated with increases in glucose uptake, cardiac energy reserve, and the PPP and the decrease in oxidative stress.115 However, DCA does not show its protective effects in patients with congestive heart failure.200 In diabetic rat hearts, although DCA treatment during reperfusion significantly augments glucose oxidation, DCA has no effect on functional recovery from ischemic injury. Glucose oxidation may not be a key factor in governing the ability of diabetic rat hearts to recover from I/R.201

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Numerous studies have firmly established that heart failure is associated with profound metabolic remodeling. Multiple layers of crosstalk exist among individual glucose metabolic pathways to regulate substrate availability and ATP production. The increase in glucose metabolism in onset of heart disease is associated with an adaptive mechanism to protect the heart from injury. Chronic activation, however, may lead to decompensation and heart failure progression. Metabolic remodeling plays an essential role in regulating not only nutrient utilization, but also ionic and redox homeostasis, UPR, and autophagy, thereby affecting cardiac contractile function. A better and more‐thorough understanding of the mechanisms of action and regulation may pave a new way for therapeutic discoveries to tackle heart failure.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from American Heart Association (14SDG18440002, 17IRG33460191), American Diabetes Association (1‐17‐IBS‐120), and NIH (HL137723) (to Wang).

Disclosures

None.

J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012673 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012673.

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braunwald E. Shattuck lecture–cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1360–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drazner MH. The progression of hypertensive heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashrafian H, Frenneaux MP, Opie LH. Metabolic mechanisms in heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:434–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doenst T, Nguyen TD, Abel ED. Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: implications beyond ATP production. Circ Res. 2013;113:709–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kundu BK, Zhong M, Sen S, Davogustto G, Keller SR, Taegtmeyer H. Remodeling of glucose metabolism precedes pressure overload‐induced left ventricular hypertrophy: review of a hypothesis. Cardiology. 2015;130:211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ritterhoff J, Tian R. Metabolism in cardiomyopathy: every substrate matters. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wende AR, Brahma MK, McGinnis GR, Young ME. Metabolic origins of heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2017;2:297–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gibb AA, Hill BG. Metabolic coordination of physiological and pathological cardiac remodeling. Circ Res. 2018;123:107–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abel ED. Glucose transport in the heart. Front Biosci. 2004;9:201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abel ED, Kaulbach HC, Tian R, Hopkins JC, Duffy J, Doetschman T, Minnemann T, Boers ME, Hadro E, Oberste‐Berghaus C, Quist W, Lowell BB, Ingwall JS, Kahn BB. Cardiac hypertrophy with preserved contractile function after selective deletion of GLUT4 from the heart. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1703–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tian R, Abel ED. Responses of GLUT4‐deficient hearts to ischemia underscore the importance of glycolysis. Circulation. 2001;103:2961–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liao R, Jain M, Cui L, D'Agostino J, Aiello F, Luptak I, Ngoy S, Mortensen RM, Tian R. Cardiac‐specific overexpression of GLUT1 prevents the development of heart failure attributable to pressure overload in mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2125–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pereira RO, Wende AR, Olsen C, Soto J, Rawlings T, Zhu Y, Anderson SM, Abel ED. Inducible overexpression of GLUT1 prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and attenuates structural remodeling in pressure overload but does not prevent left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000301 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pereira RO, Wende AR, Olsen C, Soto J, Rawlings T, Zhu Y, Riehle C, Abel ED. GLUT1 deficiency in cardiomyocytes does not accelerate the transition from compensated hypertrophy to heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;72:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chanda D, Luiken JJ, Glatz JF. Signaling pathways involved in cardiac energy metabolism. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:2364–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li XB, Gu JD, Zhou QH. Review of aerobic glycolysis and its key enzymes – new targets for lung cancer therapy. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6(1):17‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kashiwaya Y, Sato K, Tsuchiya N, Thomas S, Fell DA, Veech RL, Passonneau JV. Control of glucose utilization in working perfused rat heart. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25502–25514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hue L, Rider MH. Role of fructose 2,6‐bisphosphate in the control of glycolysis in mammalian tissues. Biochem J. 1987;245:313–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dhar‐Chowdhury P, Malester B, Rajacic P, Coetzee WA. The regulation of ion channels and transporters by glycolytically derived ATP. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:3069–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leong HS, Brownsey RW, Kulpa JE, Allard MF. Glycolysis and pyruvate oxidation in cardiac hypertrophy—why so unbalanced? Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2003;135:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, Lorell BH, Pinz I, Schultz V, Tornheim K, Tian R. Mechanisms for increased glycolysis in the hypertrophied rat heart. Hypertension. 2004;44:662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donthi RV, Ye G, Wu C, McClain DA, Lange AJ, Epstein PN. Cardiac expression of kinase‐deficient 6‐phosphofructo‐2‐kinase/fructose‐2,6‐bisphosphatase inhibits glycolysis, promotes hypertrophy, impairs myocyte function, and reduces insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48085–48090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang J, Xu J, Wang Q, Brainard RE, Watson LJ, Jones SP, Epstein PN. Reduced cardiac fructose 2,6 bisphosphate increases hypertrophy and decreases glycolysis following aortic constriction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gibb AA, Epstein PN, Uchida S, Zheng Y, McNally LA, Obal D, Katragadda K, Trainor P, Conklin DJ, Brittian KR, Tseng MT, Wang J, Jones SP, Bhatnagar A, Hill BG. Exercise‐induced changes in glucose metabolism promote physiological cardiac growth. Circulation. 2017;136:2144–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Q, Donthi RV, Wang J, Lange AJ, Watson LJ, Jones SP, Epstein PN. Cardiac phosphatase‐deficient 6‐phosphofructo‐2‐kinase/fructose‐2,6‐bisphosphatase increases glycolysis, hypertrophy, and myocyte resistance to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2889–H2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baba SP, Zhang D, Singh M, Dassanayaka S, Xie Z, Jagatheesan G, Zhao J, Schmidtke VK, Brittian KR, Merchant ML, Conklin DJ, Jones SP, Bhatnagar A. Deficiency of aldose reductase exacerbates early pressure overload‐induced cardiac dysfunction and autophagy in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;118:183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Son NH, Ananthakrishnan R, Yu S, Khan RS, Jiang H, Ji R, Akashi H, Li Q, O'Shea K, Homma S, Goldberg IJ, Ramasamy R. Cardiomyocyte aldose reductase causes heart failure and impairs recovery from ischemia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jain M, Brenner DA, Cui L, Lim CC, Wang B, Pimentel DR, Koh S, Sawyer DB, Leopold JA, Handy DE, Loscalzo J, Apstein CS, Liao R. Glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase modulates cytosolic redox status and contractile phenotype in adult cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2003;93:e9–e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hecker PA, Lionetti V, Ribeiro RF Jr, Rastogi S, Brown BH, O'Connell KA, Cox JW, Shekar KC, Gamble DM, Sabbah HN, Leopold JA, Gupte SA, Recchia FA, Stanley WC. Glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency increases redox stress and moderately accelerates the development of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jain M, Cui L, Brenner DA, Wang B, Handy DE, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J, Apstein CS, Liao R. Increased myocardial dysfunction after ischemia‐reperfusion in mice lacking glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase. Circulation. 2004;109:898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCommis KS, Douglas DL, Krenz M, Baines CP. Cardiac‐specific hexokinase 2 overexpression attenuates hypertrophy by increasing pentose phosphate pathway flux. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000355 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Watson LJ, Long BW, DeMartino AM, Brittian KR, Readnower RD, Brainard RE, Cummins TD, Annamalai L, Hill BG, Jones SP. Cardiomyocyte Ogt is essential for postnatal viability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H142–H153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watson LJ, Facundo HT, Ngoh GA, Ameen M, Brainard RE, Lemma KM, Long BW, Prabhu SD, Xuan YT, Jones SP. O‐linked beta‐N‐acetylglucosamine transferase is indispensable in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17797–17802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dassanayaka S, Brainard RE, Watson LJ, Long BW, Brittian KR, DeMartino AM, Aird AL, Gumpert AM, Audam TN, Kilfoil PJ, Muthusamy S, Hamid T, Prabhu SD, Jones SP. Cardiomyocyte Ogt limits ventricular dysfunction in mice following pressure overload without affecting hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2017;112:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krishnan J, Suter M, Windak R, Krebs T, Felley A, Montessuit C, Tokarska‐Schlattner M, Aasum E, Bogdanova A, Perriard E, Perriard JC, Larsen T, Pedrazzini T, Krek W. Activation of a HIF1alpha‐PPARgamma axis underlies the integration of glycolytic and lipid anabolic pathways in pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2009;9:512–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang Y, Hickey RP, Yeh JL, Liu D, Dadak A, Young LH, Johnson RS, Giordano FJ. Cardiac myocyte‐specific HIF‐1alpha deletion alters vascularization, energy availability, calcium flux, and contractility in the normoxic heart. FASEB J. 2004;18:1138–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang L, Jaswal JS, Ussher JR, Sankaralingam S, Wagg C, Zaugg M, Lopaschuk GD. Cardiac insulin‐resistance and decreased mitochondrial energy production precede the development of systolic heart failure after pressure‐overload hypertrophy. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1039–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mori J, Basu R, McLean BA, Das SK, Zhang L, Patel VB, Wagg CS, Kassiri Z, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Agonist‐induced hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction are associated with selective reduction in glucose oxidation: a metabolic contribution to heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jenkins CM, Yang J, Sims HF, Gross RW. Reversible high affinity inhibition of phosphofructokinase‐1 by acyl‐CoA: a mechanism integrating glycolytic flux with lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11937–11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Izawa Y, Yoshizumi M, Fujita Y, Ali N, Kanematsu Y, Ishizawa K, Tsuchiya K, Obata T, Ebina Y, Tomita S, Tamaki T. ERK1/2 activation by angiotensin II inhibits insulin‐induced glucose uptake in vascular smooth muscle cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Opie LH. Myocardial ischemia‐metabolic pathways and implications of increased glycolysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1990;4:777–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lopaschuk GD. Metabolic changes in the acutely ischemic heart. Heart Metab. 2016;70:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jaswal JS, Keung W, Wang W, Ussher JR, Lopaschuk GD. Targeting fatty acid and carbohydrate oxidation—a novel therapeutic intervention in the ischemic and failing heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1333–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gao Q, Deng H, Li H, Sun C, Sun Y, Wei B, Guo M, Jiang X. Glycolysis and fatty acid β‐oxidation, which one is the culprit of ischemic reperfusion injury? Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Finegan BA, Lopaschuk GD, Coulson CS, Clanachan AS. Adenosine alters glucose use during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Circulation. 1993;87:900–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu Q, Docherty JC, Rendell JCT, Clanachan AS, Lopaschuk GD. High levels of fatty acids delay the recoveryof intracellular pH and cardiac efficiency inpost‐ischemic hearts by inhibiting glucose oxidation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang X, Xu L, Gillette TG, Jiang X, Wang ZV. The unfolded protein response in ischemic heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;117:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lopaschuk GD, Wambolt RB, Barr RL. An imbalance between glycolysis and glucose oxidation is a possible explanation for the detrimental effects of high levels of fatty acids during aerobic reperfusion of ischemic hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fillmore N, Mori J, Lopaschuk GD. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation alterations in heart failure, ischaemic heart disease and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2080–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Galzerano D, D'Amore A, Rubino P, Verza M, Teasuro P, Varricchio M, D'Onofrio F. Total‐body and myocardial substrate oxidation in congestive heart failure. Metabolism. 1994;43:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Taylor M, Wallhaus TR, Degrado TR, Russell DC, Stanko P, Nickles RJ, Stone CK. An evaluation of myocardial fatty acid and glucose uptake using PET with [18F]fluoro‐6‐thia‐heptadecanoic acid and [18F]FDG in patients with congestive heart failure. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lommi J, Kupari M, Yki‐Jarvinen H. Free fatty acid kinetics and oxidation in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Diakos NA, Navankasattusas S, Abel ED, Rutter J, McCreath L, Ferrin P, McKellar SH, Miller DV, Park SY, Richardson RS, Deberardinis R, Cox JE, Kfoury AG, Selzman CH, Stehlik J, Fang JC, Li DY, Drakos SG. Evidence of glycolysis up‐regulation and pyruvate mitochondrial oxidation mismatch during mechanical unloading of the failing human heart: implications for cardiac reloading and conditioning. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2016;1:432–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fillmore N, Levasseur JL, Fukushima A, Wagg CS, Wang W, Dyck JRB, Lopaschuk GD. Uncoupling of glycolysis from glucose oxidation accompanies the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Mol Med. 2018;24:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Heather LC, Cole MA, Lygate CA, Evans RD, Stuckey DJ, Murray AJ, Neubauer S, Clarke K. Fatty acid transporter levels and palmitate oxidation rate correlate with ejection fraction in the infarcted rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chandler MP, Kerner J, Huang H, Vazquez E, Reszko A, Martini WZ, Hoppel CL, Imai M, Rastogi S, Sabbah HN, Stanley WC. Moderate severity heart failure does not involve a downregulation of myocardial fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1538–H1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Funada J, Betts TR, Hodson L, Humphreys SM, Timperley J, Frayn KN, Karpe F. Substrate utilization by the failing human heart by direct quantification using arterio‐venous blood sampling. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. González RG, Barnett P, Aguayo J, Cheng HM, Chylack LT Jr. Direct measurement of polyol pathway activity in the ocular lens. Diabetes. 1984;33:196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Srivastava SK, Ramana KV, Bhatnagar A. Role of aldose reductase and oxidative damage in diabetes and the consequent potential for therapeutic options. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:380–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Burg MB. Role of aldose reductase and sorbitol in maintaining the medullary intracellular milieu. Kidney Int. 1988;33:635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kaneko M, Carper D, Nishimura C, Millen J, Bock M, Hohman TC. Induction of aldose reductase expression in rat kidney mesangial cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells under hypertonic conditions. Exp Cell Res. 1990;188:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mizisin AP, Li L, Perello M, Freshwater JD, Kalichman MW, Roux L, Calcutt NA. Polyol pathway and osmoregulation in JS1 Schwann cells grown in hyperglycemic and hyperosmotic conditions. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F90–F97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Galvez AS, Ulloa JA, Chiong M, Criollo A, Eisner V, Barros LF, Lavandero S. Aldose reductase induced by hyperosmotic stress mediates cardiomyocyte apoptosis: differential effects of sorbitol and mannitol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38484–38494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Srivastava S, Dixit BL, Cai J, Sharma S, Hurst HE, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Metabolism of lipid peroxidation product, 4‐hydroxynonenal (HNE) in rat erythrocytes: role of aldose reductase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Srivastava S, Spite M, Trent JO, West MB, Ahmed Y, Bhatnagar A. Aldose reductase‐catalyzed reduction of aldehyde phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53395–53406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK. Activation of nuclear factor‐kappaB by hyperglycemia in vascular smooth muscle cells is regulated by aldose reductase. Diabetes. 2004;53:2910–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rittner HL, Hafner V, Klimiuk PA, Szweda LI, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Aldose reductase functions as a detoxification system for lipid peroxidation products in vasculitis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1007–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shinmura K. Aldose reductase is an obligatory mediator of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res. 2002;91:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Barisani D, Meneveri R, Ginelli E, Cassani C, Conte D. Iron overload and gene expression in HepG2 cells: analysis by differential display. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. O'connor T, Ireland LS, Harrison DJ, Hayes JD. Major differences exist in the function and tissue‐specific expression of human aflatoxin B1 aldehyde reductase and the principal human aldo‐keto reductase AKR1 family members. Biochem J. 1999;343:487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Keightley JA, Shang L, Kinter M. Proteomic analysis of oxidative stress‐resistant cells: a specific role for aldose reductase overexpression in cytoprotection. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]