Notes

Editorial note

This Cochrane review is now out of date and should not be used for reference. It has been split into four age groups and updated. Please refer to the 5‐11 and 12‐18 age group Cochrane reviews which were published in May 2024:

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD015328.pub2; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD015330.pub2. The 2‐4 age group Cochrane review is planned for publication in September 2024.

Abstract

Background

Prevention of childhood obesity is an international public health priority given the significant impact of obesity on acute and chronic diseases, general health, development and well‐being. The international evidence base for strategies to prevent obesity is very large and is accumulating rapidly. This is an update of a previous review.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of a range of interventions that include diet or physical activity components, or both, designed to prevent obesity in children.

Search methods

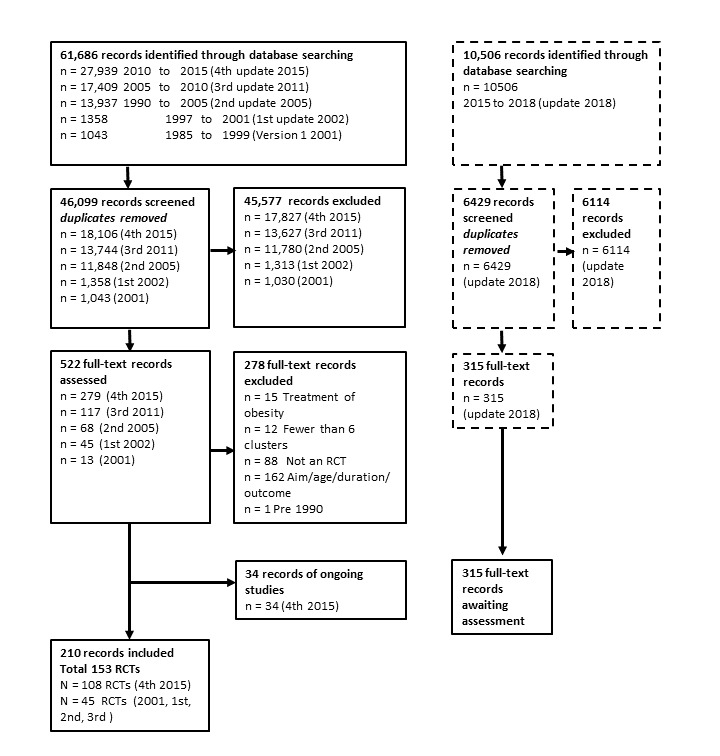

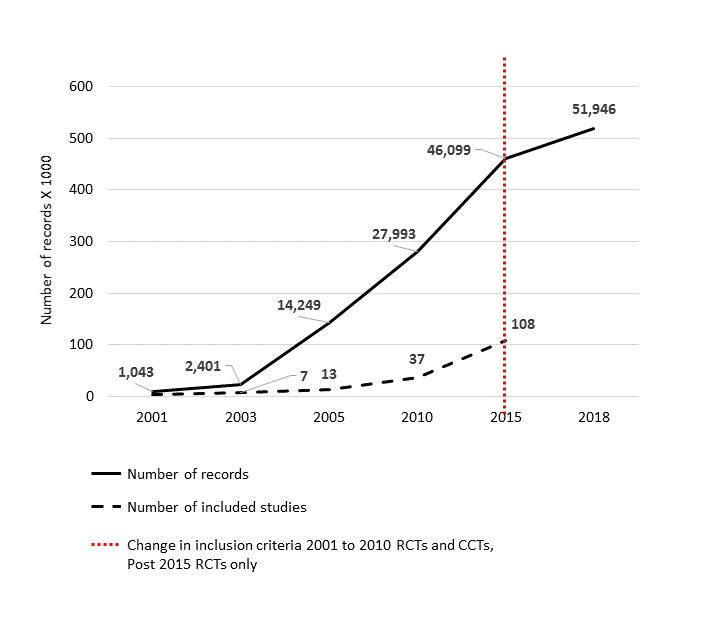

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO and CINAHL in June 2015. We re‐ran the search from June 2015 to January 2018 and included a search of trial registers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of diet or physical activity interventions, or combined diet and physical activity interventions, for preventing overweight or obesity in children (0‐17 years) that reported outcomes at a minimum of 12 weeks from baseline.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data, assessed risk‐of‐bias and evaluated overall certainty of the evidence using GRADE. We extracted data on adiposity outcomes, sociodemographic characteristics, adverse events, intervention process and costs. We meta‐analysed data as guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and presented separate meta‐analyses by age group for child 0 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years, and 13 to 18 years for zBMI and BMI.

Main results

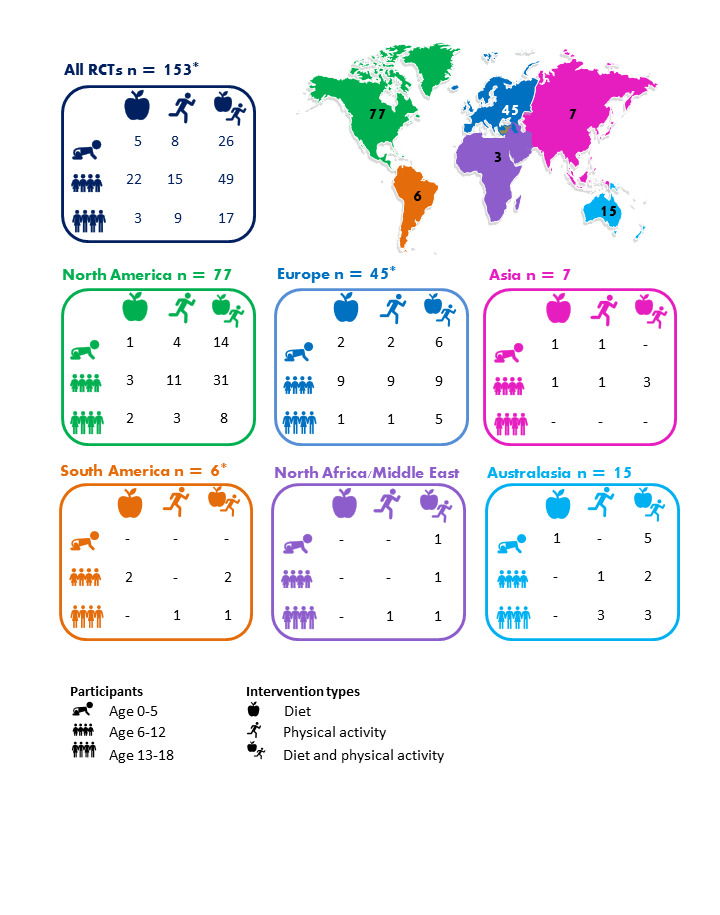

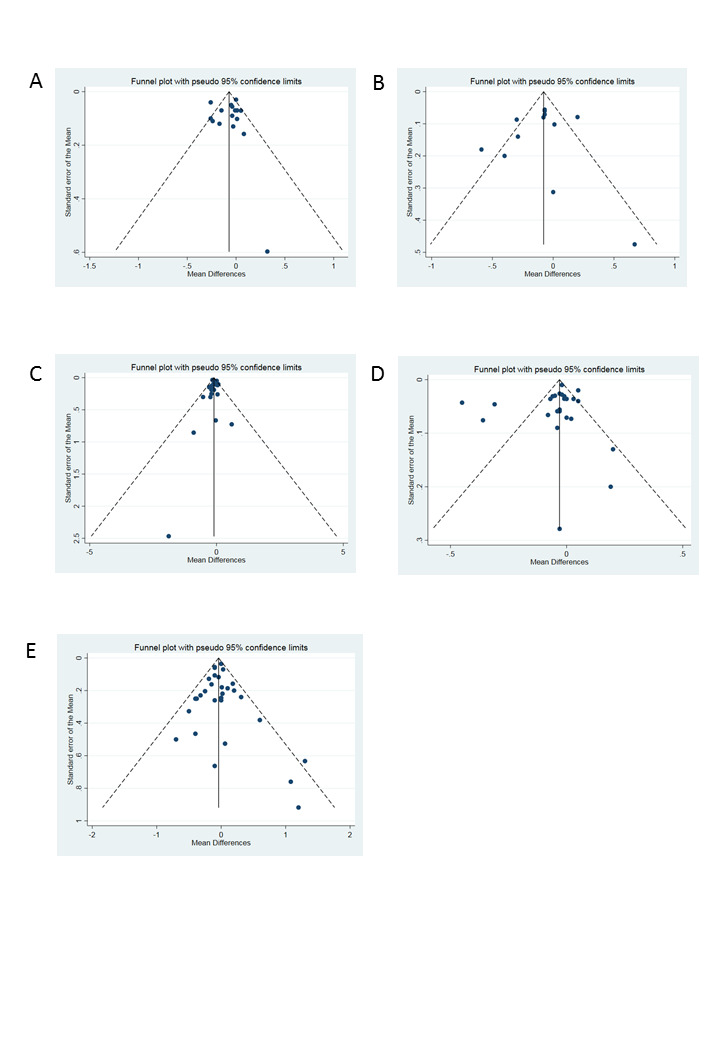

We included 153 RCTs, mostly from the USA or Europe. Thirteen studies were based in upper‐middle‐income countries (UMIC: Brazil, Ecuador, Lebanon, Mexico, Thailand, Turkey, US‐Mexico border), and one was based in a lower middle‐income country (LMIC: Egypt). The majority (85) targeted children aged 6 to 12 years. Children aged 0‐5 years: There is moderate‐certainty evidence from 16 RCTs (n = 6261) that diet combined with physical activity interventions, compared with control, reduced BMI (mean difference (MD) −0.07 kg/m2, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.14 to −0.01), and had a similar effect (11 RCTs, n = 5536) on zBMI (MD −0.11, 95% CI −0.21 to 0.01). Neither diet (moderate‐certainty evidence) nor physical activity interventions alone (high‐certainty evidence) compared with control reduced BMI (physical activity alone: MD −0.22 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.44 to 0.01) or zBMI (diet alone: MD −0.14, 95% CI −0.32 to 0.04; physical activity alone: MD 0.01, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.13) in children aged 0‐5 years. Children aged 6 to 12 years: There is moderate‐certainty evidence from 14 RCTs (n = 16,410) that physical activity interventions, compared with control, reduced BMI (MD −0.10 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.14 to −0.05). However, there is moderate‐certainty evidence that they had little or no effect on zBMI (MD −0.02, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.02). There is low‐certainty evidence from 20 RCTs (n = 24,043) that diet combined with physical activity interventions, compared with control, reduced zBMI (MD −0.05 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.01). There is high‐certainty evidence that diet interventions, compared with control, had little impact on zBMI (MD −0.03, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.01) or BMI (−0.02 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.06).

Children aged 13 to 18 years: There is very low‐certainty evidence that physical activity interventions, compared with control reduced BMI (MD −1.53 kg/m2, 95% CI −2.67 to −0.39; 4 RCTs; n = 720); and low‐certainty evidence for a reduction in zBMI (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI −0.3 to ‐0.1; 1 RCT; n = 100). There is low‐certainty evidence from eight RCTs (n = 16,583) that diet combined with physical activity interventions, compared with control, had no effect on BMI (MD −0.02 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.05); or zBMI (MD 0.01, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.07; 6 RCTs; n = 16,543). Evidence from two RCTs (low‐certainty evidence; n = 294) found no effect of diet interventions on BMI. Direct comparisons of interventions: Two RCTs reported data directly comparing diet with either physical activity or diet combined with physical activity interventions for children aged 6 to 12 years and reported no differences. Heterogeneity was apparent in the results from all three age groups, which could not be entirely explained by setting or duration of the interventions. Where reported, interventions did not appear to result in adverse effects (16 RCTs) or increase health inequalities (gender: 30 RCTs; socioeconomic status: 18 RCTs), although relatively few studies examined these factors.

Re‐running the searches in January 2018 identified 315 records with potential relevance to this review, which will be synthesised in the next update.

Authors' conclusions

Interventions that include diet combined with physical activity interventions can reduce the risk of obesity (zBMI and BMI) in young children aged 0 to 5 years. There is weaker evidence from a single study that dietary interventions may be beneficial.

However, interventions that focus only on physical activity do not appear to be effective in children of this age. In contrast, interventions that only focus on physical activity can reduce the risk of obesity (BMI) in children aged 6 to 12 years, and adolescents aged 13 to 18 years. In these age groups, there is no evidence that interventions that only focus on diet are effective, and some evidence that diet combined with physical activity interventions may be effective. Importantly, this updated review also suggests that interventions to prevent childhood obesity do not appear to result in adverse effects or health inequalities.

The review will not be updated in its current form. To manage the growth in RCTs of child obesity prevention interventions, in future, this review will be split into three separate reviews based on child age.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Infant; Male; Behavior Therapy; Body Mass Index; Combined Modality Therapy; Diet; Exercise; Exercise/physiology; Overweight; Overweight/prevention & control; Overweight/therapy; Pediatric Obesity; Pediatric Obesity/prevention & control; Pediatric Obesity/therapy; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Do diet and physical activity strategies help prevent obesity in children (aged 0 to 18 years)?

Background

More children are becoming overweight and obese worldwide. Being overweight as a child can cause health problems, and children may be affected psychologically and in their social life. Overweight children are likely also to be overweight as adults and continue to experience poor physical and mental health.

Searching for studies

We searched many scientific databases to find studies that looked at ways of preventing obesity in children. We included studies aimed at all ages of children. We only included studies if the methods they were using were aimed at changing children's diet, or their level of physical activity, or both. We looked only for the studies that contained the best information to answer this question, ‘randomised controlled trials’ or RCTs.

What we found

We found 153 RCTs. The studies were based mainly in high‐income countries such as the USA and European countries although 12% were in middle‐income countries (Brazil, Ecuador, Egypt, Lebanon, Mexico, Thailand and Turkey). Just over half the RCTs (56%) tried out strategies to change diet or activity levels in children aged 6 to 12 years, a quarter were for children aged 0 to 5 years and a fifth (20%) were for teenagers aged 13 to 18. The strategies were used in different settings such as home, preschool or school and most were targeted towards trying to change individual behaviour.

Did they work?

One widely accepted way of assessing if a child is overweight is to calculate a score based on their height and how much they weigh, and relating this to the weight and height of many children their age in their country. This is called the zBMI score. We found 61 RCTs involving over 60,000 children, that had reported zBMI scores. Children aged 0 to 5, and children aged 6 to 12 who were helped with a strategy to change their diet or activity levels reduced their zBMI score by 0.07 and 0.04 units respectively compared to children who were not given a strategy. This means these children were able to reduce their weight. This change in zBMI, when provided to many children across a whole population, is useful for governments in trying to tackle the problems of obesity in children. Strategies to change diet or physical activity, or both, given to adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 18 years, did not successfully reduce zBMI.

We looked to see if the strategies were likely to work fairly for all children, for example girls and boys, children from wealthy or less wealthy backgrounds, children from different racial backgrounds. Not many RCTs reported this, but in those that did, there was no indication that the strategies increased inequalities. However we could not find enough RCTs with this information to help us answer this question. We also looked to see if children were harmed by any of the strategies, for example by having injuries, losing too much weight or developing damaging views about themselves and their weight. Not many RCTs reported this, but in those that did, none reported any harms from children who had been given strategies to change their diet or physical activity.

We looked at how well the RCTs were done to see if they might be biased. We decided to downgrade some information based on these assessments. The quality of the evidence was ‘moderate’ for children aged 0 to 5 for zBMI, ‘low’ for children aged 6 to 12 and moderate for adolescents (13 to 18).

Our conclusions

Strategies for changing diet or activity levels, or both, of children in order to help prevent them becoming overweight or obese are effective in making modest reductions in zBMI score in children aged 0 to 5 years and in children aged 6 to 12 years. This can be useful to parents and children concerned about children becoming overweight. It can also be useful for governments, trying to tackle a growing trend of children who are becoming obese or overweight. We found less evidence for adolescents and young people aged 13 to 18, and the strategies given to them did not reduce their zBMI score.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years.

| Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years Setting: healthcare setting Intervention: dietary interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with dietary interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.75 | MD 0.14 lower (0.32 lower to 0.04 higher) | 520 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Dietary interventions likely result in little to no difference in zBMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Risk of bias: there is only one study and it has one domain (incomplete outcome data) rated as high risk of bias, with 22% of participants dropping out of the study.

Summary of findings 2. Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years.

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years Setting: childcare/preschool or healthcare setting Intervention: physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.94 to 16.4 kg/m2 | MD 0.22 kg/m2 lower (0.44 lower to 0.01 higher) | 2233 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Physical activity interventions likely do not reduce BMI |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from −0.15 to −0.22 | MD 0.01 higher (0.10 lower to 0.13 higher) | 1053 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Physical activity interventions likely do not reduce zBMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 3. Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years.

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children age 0‐5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years Setting: childcare/preschool, health system, wider community or home Intervention: combined diet and physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.15 to 0.98 | MD 0.07 lower (0.14 lower to 0.01 lower) | 6261 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Diet and physical activity interventions potentially slightly reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.8 to 17.62 kg/m2 | MD −0.11 kg/m2 lower (−0.21 lower to 0.00) | 5536 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | Diet and physical activity interventions likely result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Heterogeneity of this analysis as measured with I2 statistic was 66%, and therefore at high risk of bias. 2Heterogeneity of this analysis as measured with I2 statistic was 69%, and therefore at serious risk of bias.

Summary of findings 4. Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control in children aged 0 to 5 years.

| Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 0 to 5 years Setting: preschool, school, home, healthcare or wider community Intervention: dietary combined with physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Insufficient weight gain in infants Assessed with number of children with weight < 5th percentile and number of infants whose weight fell by 2 major centile markers Follow‐up: mean 1 year | One study of an infant feeding intervention. There was no difference in numbers of infants with weight < 5th percentile between intervention and control groups nor in the numbers of children dropping by 2 major centiles between year 1 and year 2, but this was just 80 participants. | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1 |

| Physical injuries Assessed with counts of the number of injuries | No effect of intervention on numbers of physical injuries reported in the control and intervention arms | 652 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| Adverse events | No 'adverse events' reported | 983 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 |

| Infections Assessed with parental questionnaire Follow‐up: range 2 months to 4 months | No effect of intervention on numbers of reported infections. These data are very uncertain. A single study of just 41 participants found similar numbers of (parent‐reported) infections in children in the intervention and control groups. | 709 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| Accidents Assessed with parental questionnaire Follow‐up: range 2 months to 4 months | No effect on number of accidents. These data are very uncertain. A single study of just 41 participants found similar numbers of (parent‐reported) accidents in children in the intervention and control groups. | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4 |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1Downgraded three times. Twice for imprecision, as evidence based on just one study with only 110 participants. Downloaded once for risk of bias as we judged three domains at high risk of bias and two unclear from a total of six items. 2Downgraded twice for imprecision because this outcome was reported in one of 26 studies. 3Downgraded three times for imprecision as this outcome was measured in only one of 26 studies and only 42 participants.

Summary of findings 5. Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: school or wider community Intervention: dietary interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with dietary interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.09 to 0.41 | MD 0.03 lower (0.06 lower to 0.01 higher) | 7231 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Dietary interventions alone do not reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.9 to 25.1 kg/m2 | MD 0.02 kg/m2 lower (0.11 lower to 0.06 higher) | 5061 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Dietary interventions alone do not reduce BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 6. Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: wider community or school Intervention: physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.09 to 1.75 | MD 0.02 lower (0.06 lower to 0.02 higher) | 6841 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Physical activity interventions likely result in little to no difference in zBMI. Physical activity vs control ‐ setting |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.7 to 20.41 kg/m2 | MD 0.1 kg/m2 lower (0.14 lower to 0.05 lower) | 16,410 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate2 | Physical activity interventions likely reduce BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Four of seven studies have at least one domain judged to be high risk of bias. In addition removal of these studies substantially changes the effect of having an intervention, from no effect to there being a positive effect of the intervention. 2Removal of six studies, rated high risk of bias, increased the effect size and narrowed the confidence interval.

Summary of findings 7. Adverse event outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to no intervention in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Adverse event outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: preschool, school, home, healthcare or wider community Intervention: physical activity Comparison: control | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Physical injuries | No effect on numbers of children with physical injuries in the control and intervention arms | 912 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

| Underweight Assessed with counts of children assessed as underweight | No effect on number (proportion) of children designated as underweight | 5266 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High1 |

| Depression Assessed with child's depression inventory | Depression was reduced in children in the intervention group (MD −0.21, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.001) Baseline depression score of the control group was 2.09 (SD 2.74) | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| Body satisfaction Assessed with Silhouettes scale, Self‐perceived body shape scale and the Body Dissatisfaction scale | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| Increased weight concerns | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1Downgraded for risk of bias because this study has one domain at high risk of bias. Downgraded for imprecision because only one of 22 studies reported this outcome. 2Downgraded for risk of bias as one domain of the bias tool was at high risk of bias. Downgraded for imprecision as the study included only 225 participants.

Summary of findings 8. Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: home, wider community or school Intervention: diet and physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.05 to 0.9 | MD 0.05 lower (0.10 lower to 0.01 lower) | 24,043 (20 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | Diet and physical activity interventions combined may reduce zBMI slightly |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.57 to 24.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.05 kg/m2 lower (0.11 lower to 0.01 higher) | 19,498 (25 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Diet and physical activity interventions combined may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Heterogeneity was very high with an I2 statistic of 87%. 2If studies at high risk of bias are removed, the effect of the intervention is increased from being consistent with having no effect, to indicating that the intervention reduced body‐mass index in comparison to the control.

Summary of findings 9. Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to no intervention or usual care for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 6 to 12 years Setting: school or wider community Intervention: combined dietary and physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Underweight Assessed with counts of children assessed as underweight | No effect on number (proportion) of children designated as underweight | 784 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 |

| Depression Assessed with Child's Depression Inventory | Depression was reduced in children in the intervention group (MD −0.21, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.001) Baseline depression score of the control group was 2.09 (SD 2.74) |

225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 |

| Increased weight concern Assessed with scales for weight concern | No effect of the intervention on concern about weight | 285 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Body satisfaction Assessed with Silhouettes scale, Self‐perceived Body Shape scale and the Body Dissatisfaction scale | No effect of intervention (diet and physical activity) on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 1128 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Visits to a healthcare provider | Visits to a healthcare provider were similar in the intervention and control groups; N = 1 in intervention and N = 2 in control | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 |

| Adverse events related to taking of blood samples | < 3%, similar numbers in the intervention (1.6%) and control (1.7%) groups (RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) | 4603 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate4 |

| Underweight Assessed with waist circumference of children < 10th centile | Waist circumference of children < 10th centile for weight did not differ between the intervention and control group (P = 0.373) | 724 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate4 |

| Injuries | Similar numbers of children were reported with injuries in the intervention (11%, N = 2) and control (4.7%, N = 1) groups | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RD: risk difference | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1Downgraded for risk of bias because one of the studies had an outcome rated as high risk of bias. 2Downgraded for risk of bias as one domain of the bias tool was at high risk of bias. Downgraded for imprecision as the study included only 225 participants. 3Downgraded twice for imprecision, only 60 participants, and only three events. 4Downgraded once for imprecision as there were very few events.

Summary of findings 10. Diet interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years.

| Diet interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years Setting: home or school Intervention: diet interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 24.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.13 kg/m2 lower (0.50 lower to 0.23 higher) | 294 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | Diet interventions may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1There are two studies and one has two domains at high risk of bias. 2There are two studies with 294 participants in total.

Summary of findings 11. Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years.

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years Setting: school Intervention: physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.21 to 0.81 | MD 0.2 lower (0.3 lower to 0.1 lower) | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 | The evidence suggests physical activity interventions reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 20.4 to 26.65 kg/m2 | MD 1.53 kg/m2 lower (2.67 lower to 0.39 lower) | 720 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical activity interventions on BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1One study with only 100 participants. 2Evidence from one study, which we rated at high risk of bias for blinding of participants. 3When we removed the data from studies with at least one domain at high risk of bias, the treatment effect reduces to show no difference between intervention and control. 4Heterogeneity is very high (93% value for I2 stastic). Also, one study has values that show an extremely positive effect of the intervention. When we removed this study of 80 participants, the positive effect of the intervention is removed.

Summary of findings 12. Adverse events outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to control in children aged 13 to 18 years.

| Adverse event outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children age 13 to 18 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years Intervention: physical activity Comparison: control (no intervention or usual care) | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Body satisfaction Assessed with Silhouettes scale, Self‐perceived Body Shape and Body Dissatisfaction scale | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 190 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 |

| Unhealthy weight gain Assessed with counts of children with unhealthy weight gain | No effect of intervention on unhealthy gains in weight | 546 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

| Self‐acceptance/self‐worth Assessed with Harter self‐worth scale | One study (N = 190) reported no effect of intervention on self‐acceptance. A second CRt of the same intervention reported improved self‐worth in those children who received the intervention | 546 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

| Binge eating Assessed with percent of episodes of binge eating in the past month | No effect of intervention on binge eating | 556 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1Downgraded as this study has two domains at high risk of bias. 2Downgraded for imprecision as study had only 190 participants. 3Downgraded for risk of bias, as both studies had at least one domain at high risk of bias.

Summary of findings 13. Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years.

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years Setting: home or school Intervention: diet and physical activity interventions Comparison: control | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.21 to 0.81 | MD 0.01 higher (0.05 lower to 0.07 higher) | 16,543 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | Combined diet and physical activity interventions may result in little to no difference in zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 18.99 to 24.57 kg/m2 | MD 0.02 kg/m2 lower (0.1 lower to 0.05 higher) | 16,583 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2,3 | Combined diet and physical activity interventions may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1Heterogeneity is very high, measured at 92% with I2 statistic. 250% of the studies in this meta‐analysis are at high risk of bias. 3Heterogeneity is high, measured at 58% with I2 statistic.

Summary of findings 14. Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years.

| Adverse events outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years Setting: school Intervention: diet and physical activity Comparison: control (no intervention or usual care) | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Depression Assessed with Child's Depression Inventory | No effects of the intervention on depression | 779 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Clinical levels of shape and weight concern | No effect of intervention on clinical numbers of shape or weight concern | 282 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 |

| Anxiety Assessed with anxiety scale | No effect of the intervention on anxiety | 779 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1Downgraded for risk of bias because these data appear to be from a post hoc subgroup analysis. 2Downgraded for imprecision as the number of participants was small.

Summary of findings 15. Dietary interventions compared to physical activity interventions for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Dietary interventions compared to physical activity interventions for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: school Intervention: dietary interventions Comparison: physical activity interventions | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with physical activity interventions | Risk with dietary intervention | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.4 to 18.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.03 kg/m2 lower (0.25 lower to 0.2 higher) | 4917 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Dietary interventions result in little to no difference in BMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.2 | MD 0.11 lower (0.62 lower to 0.4 higher) | 1205 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | 'Dietary interventions' results in little to no difference in zBMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 16. Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to physical activity interventions alone for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to physical activity interventions alone for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: school Intervention: combined diet and physical activity interventions Comparison: physical activity interventions alone | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with physical activity interventions | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 17.7 kg/m2 | MD 0.04 kg/m2 lower (1.05 lower to 0.97 higher) | 3946 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Combined dietary and physical activity interventions result in little to no difference in BMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.15 | MD 0.16 lower (0.57 lower to 0.25 higher) | 3946 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Combined dietary and physical activity intrventions result in little to no difference in zBMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Summary of findings 17. Dietary interventions alone compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years.

| Dietary interventions alone compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years Setting: school Intervention: dietary interventions alone Comparison: combined diet and physical activity interventions | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | Risk with dietary intervention | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 17.4 kg/m2 | MD 0.28 kg/m2 lower (1.67 lower to 1.11 higher) | 3971 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Dietary interventions alone result in little to no difference in BMI compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.2 | MD 0.05 higher (0.38 lower to 0.48 higher) | 3971 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Dietary interventions alone result in little to no difference in zBMI compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BMI: body‐mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; zBMI: body‐mass index z score | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

Background

Obesity prevention is an international public health priority (WHO 2016), and there is growing evidence of the impact of overweight and obesity on short‐ and long‐term functioning, health and well‐being (Reilly 2011). In a wide range of countries (including more recently, middle‐ and low‐income countries), high and increasing rates of overweight and obesity have been reported over the last 30 to 40 years (WHO 2016).

The global evidence suggests that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children started to rise at the end of the 1980’s GBD Obesity Collaboration 2014. By 2010, 43 million children under five years of age were overweight or obese, with approximately 35 million of these children living in low‐ and middle‐income countries (de Onis 2010). Internationally, childhood obesity rates continue to rise in some countries (e.g. Mexico, India, China, Canada), although there is evidence of a slowing of this increase or a plateauing in some age groups in some countries (WHO 2016). The World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity (WHO 2016), found that childhood obesity, including obesity in preschool children and adolescents, is reaching alarming proportions in many countries and poses an urgent and serious challenge. The Sustainable Development Goals, set by the United Nations in 2015, also identify prevention and control of non‐communicable diseases, including obesity, as core priorities (United Nations).

Once childhood obesity is established, it is difficult to reverse through interventions (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Mead 2017), and tracks through to adulthood (Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), strengthening the case for primary prevention. Adult obesity is associated with increased risk of heart disease, stroke, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and some cancers (Bhaskaran 2014; Yatsuya 2010). Children who are obese have poorer psychological well‐being and elevated levels of a number of cardiometabolic risk factors (Kipping 2008a). Obesity co‐morbidities including high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol and insulin insensitivity are being observed at an increasingly early age. Childhood obesity may cause musculoskeletal problems, obstructive sleep apnoea, asthma and a number of psychological issues (NHS England 2014). Childhood obesity is associated with type 2 diabetes and heart disease in adulthood and middle‐age mortality (Public Health England 2015). Treating obesity is very expensive and, in the UK, it was estimated (in 2014) that the NHS spends GBP 5.1 billion per year on obesity related illnesses (Dobbs 2014).

Primary preventive efforts are likely to have optimal effects if started in early childhood with parental involvement (Summerbell 2012). From birth to starting primary school is a crucial time point for obesity prevention interventions, when diet and activity behaviour are being established between parent and child. Lifestyle modification interventions to improve dietary quality, increase physical activity levels and reduce sedentary behaviours, often using behaviour‐changing techniques and involving parents or carers, or both, are the mainstay for interventions in preschool‐aged children. By intervening at such an early age, it may be possible to prevent obesity levels continuing to rise for future generations and is crucial to reducing health inequalities (Marmot 2010). As highlighted by the Commission (WHO 2016), adolescence may be a critical time for excess weight gain, in that this age group normally have more freedom in food and beverage choices made outside the home compared with younger children. This, alongside the fact that physical activity usually declines during adolescence, particularly in girls, offers both opportunities and barriers for those developing interventions.

Obesity prevalence is also inextricably linked to the degree of relative social inequality, with greater social inequality associated with a higher risk of obesity in most high‐income countries (even in infants and young children (Ballon 2018)), but in most low‐and middle‐income countries the reverse relationship is observed (Monteiro 2004). It is therefore critical that in preventing obesity we are also reducing the associated gap in health inequalities, ensuring that interventions do not inadvertently have more favourable outcomes in those with a more socio‐economically advantaged position in society. The available knowledge base on which to develop a platform of obesity prevention action and base decisions about appropriate public health interventions to reduce the risk of obesity across the whole population, or targeted towards those at greatest risk, still remains limited (Gortmaker 2011; Hillier‐Brown 2014).

The WHO Commission (WHO 2016), states that progress in tackling childhood obesity has been slow and inconsistent, and obesity prevention and treatment requires a whole‐of‐government approach in which policies across all sectors systematically take health into account, avoid harmful health impacts, and thus improve population health and health equity. Indeed, it is now acknowledged that tackling obesity requires a systems approach and policy initiatives across government departments that are joined‐up (Rutter 2017). However, as Knai and colleagues have noted in relation to Chapter 2 of the Childhood Obesity Plan for England, it suffers from continued reliance on self‐regulation at an individual level (Knai 2018). The WHO Commission (WHO 2016), suggests that upstream interventions providing guidance and training to caregivers working in child‐care settings and institutions on appropriate advice on diet, physical activity and sleep for preschool children may be particularly important. The WHO Commission (WHO 2016), also suggests that upstream interventions may be particularly important for adolescents, for example, targeting the marketing of unhealthy foods such as sugar‐sweetened beverages; tackling the obesogenic environment, such as take‐away food outlets.

The aim of this review was to update the evidence base for children given the exponential growth of studies in this field over the last five to 10 years, and thus ensure that the review remains current and policy and practice‐relevant, with particular regard for health equity. We have updated this Cochrane Review to include data reported in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published up to and including 2015. In this update, we present data by age group, from 0 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years; and 13 to 18 years. We also provide a list of RCTs published between 2016 and 2018, which we deem, from the information reported in the abstract, as likely to meet the inclusion criteria of this review.

Going forward, we will split the review into three reviews based on child age: from 0 to 5 years; 6 to 12 years, and 13 to 18 years. It is reasonable to believe that different interventions might work differently in children of different ages. For example, meaningful parent engagement may be a key factor for the effectiveness of interventions for preschool children, but this may not be the case for adolescents; adolescents may find online interventions easy to use, and attractive and engaging, because of their cognitive ability and affinity for social media, but these types of interventions might not work well for younger children.

Description of the condition

Overweight and obesity are terms used to describe an excess of adiposity (or fatness) above the ideal for good health. Current expert opinion supports the use of body‐mass index (BMI) cut‐off points to determine weight status (as healthy weight, overweight or obese) for children and adolescents and several standard BMI cut‐offs have been developed (Cole 2000; Cole 2007; de Onis 2004; de Onis 2007). Despite this, there is no consistent application of this methodology by experts and a variety of percentile‐based methods are also used, which can make it difficult to compare RCTs that have used different measures and weight outcomes.

Overweight and obesity in childhood are known to have significant impact on both physical and psychosocial health (reviewed in Lobstein 2004). Indeed, many of the cardiovascular consequences that characterise adult‐onset obesity are preceded by abnormalities that begin in childhood. Hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, abnormal glucose tolerance (Freedman 1999), and type 2 diabetes (Arslanian 2002), occur with increased frequency in obese children and adolescents and children. In addition, obesity in childhood and adolescence are known to be independent risk factors for adult obesity (Must 1992; Must 1999; Power 1997; Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), underpinning the importance of obesity prevention efforts.

Modifiable determinants of childhood obesity

Obesity results from a sustained positive energy imbalance and a variety of genetic, behavioural, cultural, environmental and economic factors have been implicated in its development (reviewed in Lobstein 2004). The interplay of these factors is complex and has been the focus of considerable research, however, the burden of obesity is not experienced uniformly across a population, with the highest levels of the condition experienced by those most disadvantaged. In high‐income countries there is a significant trend observed between obesity and lower socio‐economic status, while in some developing countries the contrary is found, with children from relatively affluent families more vulnerable to obesity.

Description of the intervention

This review involves assessing educational, behavioural and health promotion interventions. We use the terms 'intervention' and 'programme' interchangeably throughout this review. The Ottawa Charter defines four action areas for health promotion: 1) actions to develop personal skills, which are actions targeted at individual skills, behaviours, or knowledge and beliefs; 2) actions to strengthen community actions, which are actions targeted at communities and include environmental and settings‐based approaches to health promotion; 3) actions to reorientate health services, which are actions within the health sector and relate to the delivery of services; and 4) actions to build healthy public policy and create supportive environments, which are intersectoral in nature and relate to creating physical, social and policy environments that promote health WHO 1986.

Why it is important to do this review

Governments internationally are being urged to take action to prevent childhood obesity and to address the underlying determinants of the condition. To provide decision makers with high‐quality research evidence to inform their planning and resource allocation, this review aims to provide an update of the evidence from RCTs designed to compare the effect of interventions to prevent childhood obesity with the effect of receiving an alternative intervention or no intervention. We aimed to update the previous review (Waters 2011), which concluded that many diet and exercise interventions to prevent obesity in children appeared ineffective in preventing weight gain, but could be effective in promoting a healthy diet and increased levels of physical activity. The previous review also urged reconsideration of the appropriateness of study durations, designs and intervention intensity as well as making recommendations in relation to comprehensive reporting of RCTs. Overall however, although there was insufficient evidence to determine that any one particular programme could prevent obesity in children, the evidence suggested that comprehensive strategies to increase the healthiness of children’s diets and their physical activity levels, coupled with psycho‐social support and environmental change were most promising. We incorporated research evidence that has been published since that time and is also consistent with emerging issues in relation to evidence reviews and synthesis (Higgins 2011a). We also noted the important work around implementation of policies and interventions to prevent obesity in children (Wolfenden 2016a). In addition, to meet the growing demand from public health and health promotion practitioners and decision makers, we have attempted to include information related not only to the impact of interventions on preventing obesity, but also information related to how outcomes were achieved, how interventions were implemented, the context in which they were implemented (Wang 2006), and the extent to which they work equitably (Tugwell 2010). This new aspect of the review was partly guided by the Systematic Reviews of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions (Armstrong 2007), more recommendations for complex reviews and useful evidence for decision makers (Waters 2011), and informed by expert opinion.

Objectives

The main objective of the review was to determine the effectiveness of a range of interventions that include diet or physical activity components, or both, designed to prevent obesity in children, by updating the 2011 version of the review (Waters 2011). Specific objectives include:

evaluation of the effect of dietary educational interventions versus control on changes in zBMI score, BMI and adverse events among children under 18 years;

evaluation of the effect of physical activity interventions versus control on changes in zBMI score, BMI and adverse events among children under 18 years;

evaluation of combined effects of dietary educational interventions and physical activity interventions versus control on changes in zBMI score and BMI among children under 18 years

evaluation of the effect of dietary educational interventions versus physical activity interventions on changes in zBMI score, BMI and adverse events among children under 18 years.

Secondary aims were to examine the characteristics of the programmes and strategies to answer the question, 'what works for whom, why and at what cost?'. Secondary objectives include the evaluation of sociodemographic characteristics, process indicators (such as intensity, duration, setting and delivery of intervention) and contextual factors that might contribute to the outcome of the interventions. Specific objectives include:

evaluation of sociodemographic characteristics of participants (socioeconomic status, gender, age, ethnicity, geographical location, etc.);

evaluation of particular process indicators (i.e. those that describe why and how a particular intervention has worked).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included data from RCTs that were designed or had an underlying intention to prevent obesity. We included RCTs that had an active intervention period of any duration, provided that the studies reported follow‐up outcome data at a minimum of 12 weeks from baseline. We included RCTs in which individuals or groups of individuals were randomised, however, for those with group randomisation we only included cluster‐RCTs with six or more groups. We categorised RCTs primarily according to the target age group (0 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years, and 13 to 18 years). We excluded RCTs published before 1990. The global evidence suggests that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children, including preschool children, started to rise at the end of the 1980s (de Onis 2010; GBD Obesity Collaboration 2014). Given the lag time between the conception, funding, and the completion of RCTs, we considered a 1990 publication date as a pragmatic and reasonable starting point for the literature in the area.

Types of participants

We included RCTs of children with a mean age of less than 18 years at baseline. We included RCTs where children were part of a family group receiving the intervention if outcome evaluation could be extracted separately for the children. In order to reflect a public health approach that recognises the prevalence of a range of weight within the general population of children we included RCTs where the participants included children who were overweight or obese. We included RCTs that restricted eligibility according to weight if the eligibility was not restricted to children with obesity. We also included RCTs where children were ‘at risk’ for obesity, for example their parent(s) was/were overweight, or the children had low levels of physical activity. RCTs that only enrolled children who were obese at baseline we considered to be focused toward treatment rather than prevention and we therefore excluded them. We excluded RCTs of interventions designed to prevent obesity in pregnant women and RCTs designed for children with a critical illness or severe co‐morbidities.

Types of interventions

Strategies

We included educational, health promotion, psychological, family, behavioural therapy, counselling, management strategies.

Interventions included

We included various types of diet or physical activity interventions, or both. We included RCTs of interventions that included diet and nutrition, or exercise and physical activity, or both; interventions may also have included other elements such as lifestyle change (e.g. changes to sedentary behaviour or sleep) and social support. We included complementary feeding RCTs, which aimed to promote a healthy weight in babies and toddlers. We also included interventions that aimed to increase motor skills in young children, where the rationale for these interventions was based on the evidence that greater motor skills in young children lead to higher levels of physical activity as the child grows older. We excluded RCTs where the rationale of the intervention was other than preventing obesity.

Setting

We included interventions in any setting. These included interventions within the wider community (including faith‐based settings), school and out‐of‐school‐hours care, home, healthcare, and childcare or preschool/nursery/kindergarten.

Types of comparison

We included RCTs that compared diet or physical activity interventions, or both, with a non‐intervention control group who received no treatment or usual care, or another active intervention (i.e. head‐to‐head comparisons).

Intervention personnel

There was no restriction on who delivered the interventions, for example, researchers, primary care physicians (general practitioners), nutrition/diet professionals, teachers, physical activity professionals, health promotion agencies, health departments, faith leaders or others.

Indicators of theory and process

We collected data on indicators of intervention process and evaluation, health promotion theory underpinning intervention design, modes of strategies, and attrition rates from these studies. We compared where possible, whether the effect of the intervention varied according to these factors. We included this information in descriptive analyses and used it to guide the interpretation of findings and recommendations.

Interventions excluded

We excluded RCTs of interventions designed specifically for the treatment of childhood obesity and RCTs designed to treat eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa. We excluded any drug or surgery interventions, as these are treatment interventions. We excluded RCTs that were exclusively focused on breast or bottle feeding; for example, RCTs that solely evaluated the effect of various protein levels in infant formulas. We also excluded RCTs that focused solely on strength and fitness training (not aimed at obesity prevention).

Types of outcome measures

To be included, studies had to report one or more of the following primary review outcomes, presenting a baseline and a post‐intervention measurement. We focused on reporting the results for the anthropometric outcomes (primary outcomes) and listing other outcomes.

Primary outcomes

zBMI score/BMI

Prevalence of overweight and obesity

Weight and height

Ponderal index

Per cent fat content

Skin‐fold thickness

Summary of findings

We present 'Summary of findings' tables in which we report zBMI score, BMI and adverse events for the three age groups of children (0 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years and 13 to 18 years), and three intervention types (diet, physical activity, diet and physical activity combined).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for this update and for previous versions of this review. We did not exclude studies based on language.

For the 2015 update (in this review we included and synthesised data from all studies identified)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2010, Issue 1 to 2016 Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE (Ovid) January 2010 to June 2015

Embase (Ovid) January 2010 to June 2015

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ovid) March 2010 to June 2015

PsycINFO (Ovid) 2010 to June 2015

For the 2018 update (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for studies identified as potentially relevant from screening titles and abstracts)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 6 to 2018, Issue 1), in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

Embase (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

PsycINFO (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

Complete search strategies and search dates for each database can be found in the Appendices.

Update 2018 (Appendix 1). Potentially relevant studies stored in Studies awaiting classification

Update 2015 (Appendix 2). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

Update 2010 (Appendix 3). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

Update 2005 (Appendix 4). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

Searching other resources

For the 2018 update on 22 January 2018 we searched ClinicalTrials.gov with the filter 'Applied Filters: Child (birth–17)'. We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, search portal (ICTRP), using the filter for studies in children. In addition, we scanned the reference lists of key systematic reviews and references of included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2015 update, one review author (TB) performed title and abstract screening, and another review author (CS) checked a random subsample (10%). For the 2018 update, two review authors (TB and ME) independently assessed all titles and abstracts in duplicate using RAYYAN software (Rayyan‐QCRI 2016). For titles and abstracts that potentially met the inclusion criteria, we obtained the full text of the article for further evaluation. Two review authors (from TB, CO and ME), independently assessed the full‐text reports of studies against a list of criteria for inclusion. We resolved differences in opinion or uncertainty through a process of discussion. Occasionally we brought in a third review author (CS, TM).

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction form, based on the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies (Thomas 2003), with additional data extraction items specifically related to implementation. For studies identified between 2010 and 2015 we extracted information relevant to equity using the PROGRESS (Place, Race, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socio‐economic status (SES), Social status) checklist (Ueffing 2009). And to facilitate full understanding of interventions we also incorporated items from the TIDieR checklist and guide (Hoffman 2014). We also extracted information relevant to assessing risk of bias, source and involvement of funders, data on indicators of intervention process and evaluation, health promotion theory underpinning intervention design, modes of strategies, and attrition rates. Two review authors (CO, TB) independently extracted data from included papers into the data extraction form for each study.

This review sought to identify studies that had reported on socio‐demographic characteristics known to be important from an equity perspective using the PROGRESS checklist (Ueffing 2009).

We attempted to capture factors that we could use to assess implementability of the interventions. These included: programme reach (i.e. was the intervention available to all those to whom it would be relevant?); programme acceptability (was the intervention acceptable to the target population?); and programme integrity (was the programme implemented as planned?). A comprehensive process evaluation allowed us to monitor variability in context and delivery, and to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of included RCTs using the 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). At least two review authors assessed each study as being at ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias for each item. Review authors were not blinded with respect to study authors, institution or journal. We used discussion and consensus to resolve any disagreements.

We incorporated performance and detection bias under the item 'blinding' in the 'Risk of bias' tool. We assessed this to be at low risk for RCTs that reported blinding of outcome assessors, and high risk for RCTs reporting that outcome assessors were not blinded.

We assessed RCTs as low risk for attrition bias if an adequate description of participant flow through the study was provided, the proportion of missing outcome data was relatively balanced between groups and the reasons for missing outcome data were provided and we considered them unlikely to bias the results. We assessed RCTs ‘high’ risk for attrition if attrition was 30% or greater at final follow‐up.

For cluster‐randomised trials we made an additional assessment listed as ‘other bias’ based on the advice for dealing with cluster‐RCTs (Higgins 2011a). For ‘timing of recruitment of clusters’, we rated RCTs at ‘high’ risk of bias if the studies had recruited the clusters after randomisation and at ‘low’ risk of bias if recruitment occurred before randomisation.

For selective outcome reporting we searched for both trial registrations and protocols. Where we were unable to find a trial registration or protocol, we recorded 'selective outcome reporting' as unclear. If all relevant primary outcomes reported in the study report or protocol were reported in the results of the paper, we marked these as low risk of bias. If relevant primary outcomes reported in the study report or protocol were not reported (in the results paper) we recorded these as high risk of bias. Where studies reported an outcome in the results paper that they had not prespecified in the protocol or trials register, we reported this as high risk of bias. For RCTs where we could not locate a protocol or trial registration document, we recorded risk of bias as unclear. See Table 8.5 and Section 8.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Measures of treatment effect