Abstract

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life‐threatening condition caused by direct or indirect injury to the lungs. Despite improvements in clinical management (for example, lung protection strategies), mortality in this patient group is at approximately 40%. This is an update of a previous version of this review, last published in 2004.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacological agents in adults with ARDS on mortality, mechanical ventilation, and fitness to return to work at 12 months.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL on 10 December 2018. We searched clinical trials registers and grey literature, and handsearched reference lists of included studies and related reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing pharmacological agents with control (placebo or standard therapy) to treat adults with established ARDS. We excluded trials of nitric oxide, inhaled prostacyclins, partial liquid ventilation, neuromuscular blocking agents, fluid and nutritional interventions and medical oxygen. We excluded studies published earlier than 2000, because of changes to lung protection strategies for people with ARDS since this date.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risks of bias. We assessed the certainty of evidence with GRADE.

Main results

We included 48 RCTs with 6299 participants who had ARDS; two included only participants with mild ARDS (also called acute lung injury). Most studies included causes of ARDS that were both direct and indirect injuries. We noted differences between studies, for example the time of administration or the size of dose, and because of unclear reporting we were uncertain whether all studies had used equivalent lung protection strategies.

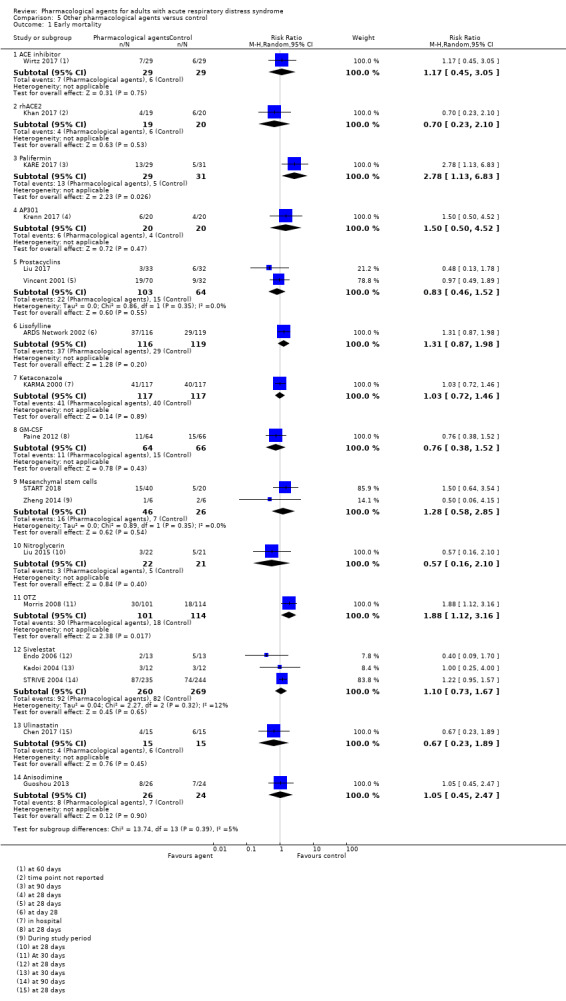

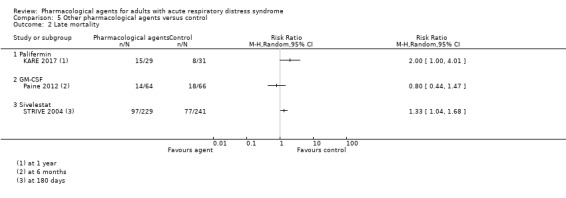

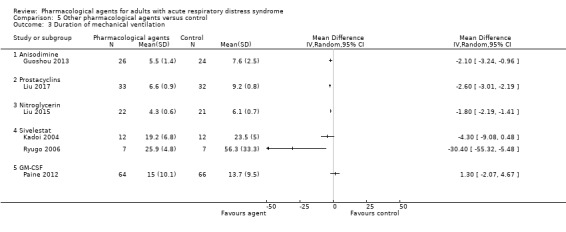

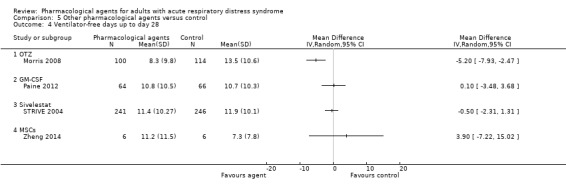

We included five types of agents as the primary comparisons in the review: corticosteroids, surfactants, N‐acetylcysteine, statins, and beta‐agonists. We included 15 additional agents (sivelestat, mesenchymal stem cells, ulinastatin, anisodimine, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, recombinant human ACE2 (palifermin), AP301, granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), levosimendan, prostacyclins, lisofylline, ketaconazole, nitroglycerins, L‐2‐oxothiazolidine‐4‐carboxylic acid (OTZ), and penehyclidine hydrochloride).

We used GRADE to downgrade outcomes for imprecision (because of few studies and few participants), for study limitations (e.g. high risks of bias) and for inconsistency (e.g. differences between study data).

Corticosteroids versus placebo or standard therapy

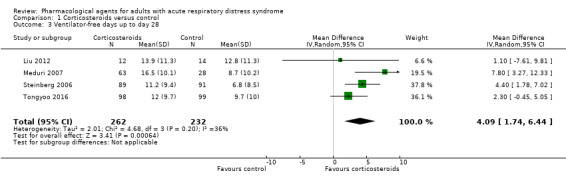

Corticosteroids may reduce all‐cause mortality within three months by 86 per 1000 patients (with as many as 161 fewer to 19 more deaths); however, the 95% confidence interval (CI) includes the possibility of both increased and reduced deaths (risk ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.05; 6 studies, 574 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Due to the very low‐certainty evidence, we are uncertain whether corticosteroids make little or no difference to late all‐cause mortality (later than three months) (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.52; 1 study, 180 participants), or to the duration of mechanical ventilation (mean difference (MD) −4.30, 95% CI −9.72 to 1.12; 3 studies, 277 participants). We found that ventilator‐free days up to day 28 (VFD) may be improved with corticosteroids (MD 4.09, 95% CI 1.74 to 6.44; 4 studies, 494 participants; low‐certainty evidence). No studies reported adverse events leading to discontinuation of study medication, or fitness to return to work at 12 months (FTR).

Surfactants versus placebo or standard therapy

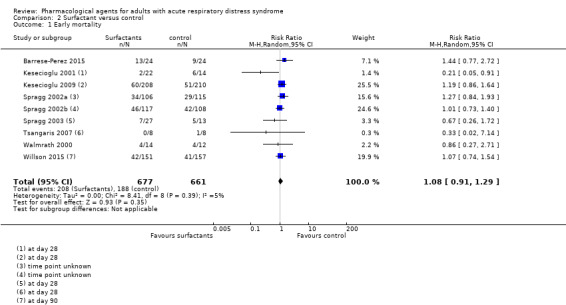

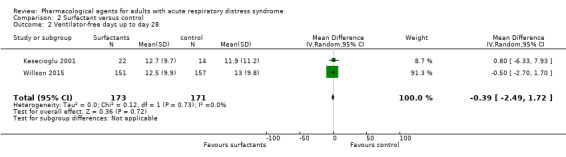

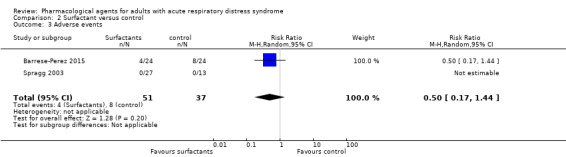

We are uncertain whether surfactants make little or no difference to early mortality (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.29; 9 studies, 1338 participants), or whether they reduce late all‐cause mortality (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.61; 1 study, 418 participants). Similarly, we are uncertain whether surfactants reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation (MD −2.50, 95% CI −4.95 to ‐0.05; 1 study, 16 participants), make little or no difference to VFD (MD −0.39, 95% CI −2.49 to 1.72; 2 studies, 344 participants), or to adverse events leading to discontinuation of study medication (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.44; 2 studies, 88 participants). We are uncertain of these effects because we assessed them as very low‐certainty. No studies reported FTR.

N‐aceytylcysteine versus placebo

We are uncertain whether N‐acetylcysteine makes little or no difference to early mortality, because we assessed this as very low‐certainty evidence (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.30; 1 study, 36 participants). No studies reported late all‐cause mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, VFD, adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation, or FTR.

Statins versus placebo

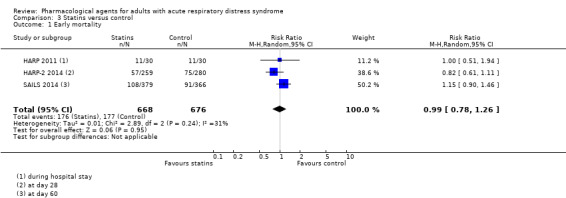

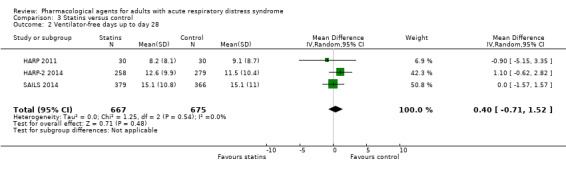

Statins probably make little or no difference to early mortality (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.26; 3 studies, 1344 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) or to VFD (MD 0.40, 95% CI −0.71 to 1.52; 3 studies, 1342 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). Statins may make little or no difference to duration of mechanical ventilation (MD 2.70, 95% CI ‐3.55 to 8.95; 1 study, 60 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We could not include data for adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation in one study because it was unclearly reported. No studies reported late all‐cause mortality or FTR.

Beta‐agonists versus placebo control

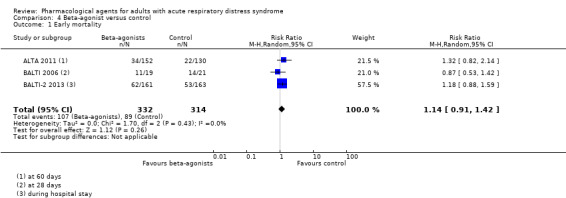

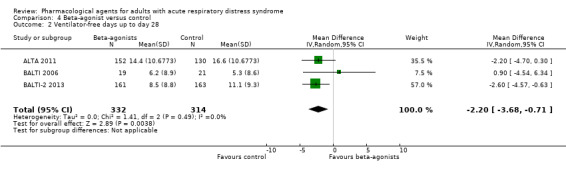

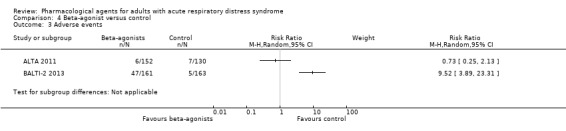

Beta‐agonists probably slightly increase early mortality by 40 per 1000 patients (with as many as 119 more or 25 fewer deaths); however, the 95% CI includes the possibility of an increase as well as a reduction in mortality (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.42; 3 studies, 646 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). Due to the very low‐certainty evidence, we are uncertain whether beta‐agonists increase VFD (MD −2.20, 95% CI −3.68 to −0.71; 3 studies, 646 participants), or make little or no difference to adverse events leading to study drug discontinuation (one study reported little or no difference between groups, and one study reported more events in the beta‐agonist group). No studies reported late all‐cause mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, or FTR.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence to determine with certainty whether corticosteroids, surfactants, N‐acetylcysteine, statins, or beta‐agonists were effective at reducing mortality in people with ARDS, or duration of mechanical ventilation, or increasing ventilator‐free days. Three studies awaiting classification may alter the conclusions of this review. As the potential long‐term consequences of ARDS are important to survivors, future research should incorporate a longer follow‐up to measure the impacts on quality of life.

Plain language summary

Drugs to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults

We set out to determine, from randomized controlled trials, which drugs improve health outcomes in adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Background

ARDS is a life‐threatening condition caused by injury to the lungs, for example from infections such as pneumonia or sepsis, or from trauma. People with ARDS are cared for in an intensive care unit, and need support with breathing from mechanical ventilation. Many people who survive ARDS suffer from muscle weakness, fatigue, reduced quality of life after hospital discharge, and may not be fit for work 12 months later. Despite improvements in techniques to manage ARDS, death rates are still very high. Drugs may help to repair damage to the lung injury, or limit the body's response to the injury (for example, by reducing any excess fluid that may collect around the injured lungs).

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to 10 December 2018. We included 48 studies, of 20 different drug types, involving 6299 people who had ARDS. Three studies are awaiting classification (because we did not have enough details to assess them), and 18 studies are still ongoing. We found differences between included studies, such as the severity of ARDS, or potential differences in clinical management and doses. We excluded studies published before 2000, in order to only include up‐to‐date clinical management of people with ARDS (for example, in the pressure applied during mechanical ventilation). However, we found that many studies did not report these management strategies.

For the main comparisons in this review, we included five types of drugs: corticosteroids, surfactants, N‐acetylcysteine, statins, and beta‐agonists. These were compared to placebo or to standard care.

Key results

Although corticosteroids may reduce the number of people who die within the first three months, and beta‐agonists probably slightly increase these early deaths, we found both an increase and a reduction in deaths in our analyses for these drugs. We found no evidence that surfactants, N‐acetylcysteine, or statins made a difference to the number of people who died within three months. Only two studies (one that assessed steroids, and one surfactants) reported deaths later than three months, but evidence for this was uncertain.

We found that statins or steroids may make little or no difference to the duration of mechanical ventilation, but we were uncertain about the evidence for steroids. Similarly, we were uncertain whether surfactants reduced the use of mechanical ventilation. We found that steroids may improve the number of days that people do not need mechanical ventilation (ventilator‐free days up to day 28), but that beta‐agonists may not improve ventilator‐free days (although we were uncertain about the evidence for beta‐agonists). We found that statins probably make little or no difference to the number of ventilator‐free days; this was also the case for surfactants (although, again, we were uncertain about the evidence for surfactants).

Few studies (and only for surfactants and beta‐agonists) reported whether the study drug was stopped because of serious side effects, and we were uncertain whether either of these drugs led to such serious side effects. No studies reported whether people were fit to return to work 12 months after their illness.

Certainty of the evidence

Most of the findings were supported by low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence, although we were moderately confident in the evidence for some outcomes when statins and beta‐agonists were used. For some outcomes we found too few studies with few participants, and sometimes there were unexplained differences between the studies in their findings. These factors reduced our certainty (or confidence) in our findings. Also, it was not possible to mask some researchers because the study drug was compared to standard therapy (no drug), which may have biased our findings.

Conclusion

We found insufficient evidence to determine confidently whether any type of drug was effective at reducing deaths in people with ARDS, or reducing the length of time that they needed mechanical ventilation. No studies reported fitness to return to work at 12 months. We assessed most outcomes to be low or very low certainty, which reduces our confidence in the findings of the review.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), first described in 1967 (Ashbaugh 1967), is characterized by diffuse inflammation of the lung's alveolar‐capillary membrane in response to various pulmonary and extrapulmonary insults (Ware 2000). These insults cause pulmonary injury by direct mechanisms (for example, gastric aspiration, pneumonia, inhalational injury, pulmonary contusion), or indirect mechanisms (for example, sepsis, trauma, pancreatitis, multiple transfusions of blood products). An American‐European Consensus Conference (AECC) formulated a widely‐cited definition of ARDS as follows (Bernard 1994):

an acute onset of hypoxaemia, with a ratio of the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) to the inspired fraction of oxygen (FiO2) of 200 mmHg or less;

bilateral infiltrates on a frontal chest radiograph;

no clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension or a pulmonary artery occlusion pressure of 18 mmHg or less in the presence of a pulmonary artery catheter.

This AECC definition defined acute lung injury (ALI) as a milder form of lung injury, with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 300 mmHg or less, with ARDS therefore being a subset of ALI. A more recent definition, known as the Berlin definition, provides a time in which ARDS is developed, and categorizes severity into mild, moderate or severe ARDS, thus removing the distinction between ALI and ARDS (ARDS Definition Task Force 2012). This definition includes the following criteria:

within one week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms;

bilateral opacities, not fully explained by effusions, lobar or lung collapse, or nodules;

respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. Objective assessment (e.g. echocardiography) needed to exclude hydrostatic oedema if no risk factor present;

mild ARDS: PaO2/FiO2 > 200 mmHg and ≤ 300 mmHg with positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ≥ 5 cmH2O;

moderate ARDS: PaO2/FiO2 > 100 mmHg and ≤ 200 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O;

severe ARDS: PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O.

An epidemiological study of 50 countries reported the prevalence of ARDS as 10.4% of all intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, with mortality estimated to be approximately 40% (Bellani 2016). Almost all people with ARDS require mechanical ventilation to survive; all require supplemental oxygen. In addition, survivors have a prolonged stay in the ICU and demonstrate significant functional limitations, primarily fatigue and muscle weakness, that reduce their quality of life after hospital discharge; only 50% of survivors are fit to return to work after 12 months (Herridge 2003).

Description of the intervention

Research on therapy for ARDS has focused on both physiological and pharmacological therapies. Lung protection strategies, using lower tidal volumes (Guay 2018), have been widely adopted since the ARDS Network publication (ARDS Network 2000; Petrucci 2013). Other strategies that have been trialed include high‐frequency oscillatory ventilation (Sud 2016), high versus low PEEP (Santa Cruz 2013), pressure‐controlled versus volume‐controlled ventilation (Chacko 2015), recruitment manoeuvres (Hodgson 2016), and use of prone positioning (Bloomfield 2015).

The pathogenesis of ARDS, extensively reviewed elsewhere (Luce 1998; Ware 2000), provides multiple potential targets for pharmacological interventions. Regardless of the inciting insult, the pathology of ARDS features damage to the alveolar‐capillary membrane, with leakage of protein‐rich oedema fluid into alveoli. Epithelial damage involves the basement membrane and types I and II cells. Injury reduces the amount and function of surfactant produced by type II cells. This increases alveolar surface tension, decreases lung compliance, and causes atelectasis. Endothelial damage is associated with numerous inflammatory events. These include neutrophil recruitment, sequestration and activation; formation of oxygen radicals; activation of the coagulation system, leading to microvascular thrombosis with platelet‐fibrin thrombi; and recruitment of mesenchymal cells with production of procollagen (a precursor to fibrosing alveolitis). Within the alveolar space, the balance between pro‐inflammatory (for example, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha and interleukins (IL) 1, 6, and 8) and anti‐inflammatory mediators (for example, IL‐1 receptor antagonist and soluble TNF receptor) favours ongoing inflammation. In summary, initial lung injury is followed by repair, remodelling, and fibrosing alveolitis.

Interventions in this review are pharmacological agents that aim to repair specific damage or response to the lung injury. These agents may be man‐made, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) and include, amongst others: corticosteroids; surfactants; N‐acetylcysteine; statins; and beta‐agonists.

How the intervention might work

The diversity of approaches to pharmacological therapy for ARDS reflects the complex pathophysiology, and each therapy may differ in its proposed mechanism of action. Of just some of the possible pharmacological agents that may be used to treat the symptoms of ARDS: corticosteroids may provide multiple anti‐inflammatory pathways (Pehora 2017; Polderman 2018); surfactants may restore the normal mechanical properties of alveoli (surface tension, alveolar opening) (Spragg 2003); N‐acetylcysteine may be used for its antioxidant properties (Ortolani 2000); statins may reduce pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses (HARP‐2 2014); and beta‐agonists may reduce pulmonary oedema and improve alveolar fluid clearance (ALTA 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Recent guidelines have recommended the use of therapies in relation to lung protection strategies, fluid management strategies, neuromuscular blocking agents (Lundstrøm 2017), positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP), extra‐corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), extra‐corporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCOR), and prone positioning (FICM/ICS Guideline Development Group 2018). This guideline provides a research recommendation for corticosteroids because of insufficient evidence; the range of pharmacological agents in this review are not included in the guideline. The effectiveness of pharmacological agents to reduce mortality or mechanical ventilation is still not established (Nanchal 2018).

This review is an update of a previous version (Adhikari 2004). Research interest in this condition continues, and we aim to incorporate new findings for agents included in the previous version, as well as new agents that were not previously included. The outcomes in the previous version remain relevant, but this review includes consideration of the long‐term consequences and includes fitness to return to work after 12 months (Herridge 2003). The methods used to assess the certainty of evidence in Cochrane Reviews has since been updated, and we reflect these methodological changes and now incorporate a GRADE assessment and 'Summary of findings' tables for the primary comparisons.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacological agents in adults with ARDS on mortality, mechanical ventilation, and fitness to return to work at 12 months.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded quasi‐randomized trials.

We excluded studies published prior to 2000. We based the decision to restrict studies by publication date on an important study in 2000 advocating the use of lower tidal volumes in people with ARDS, which resulted in changes to standard practice in mechanical ventilation management for these people (ARDS Network 2000).

Types of participants

We included adult participants with ARDS admitted to an ICU. We used authors' definitions of adult, and included studies if the mean age of participants was more than 18 years. In addition, we used authors' definitions of ARDS, and included participants that were diagnosed according to the AECC criteria, with a distinction between ALI and ARDS (Bernard 1994), and the later Berlin definition which includes a distinction between mild, moderate, and severe ARDS (ARDS Definition Task Force 2012), or other criteria. We excluded studies in which ARDS (and ALI, where appropriate) was not reported as a required study inclusion criterion; we therefore excluded studies in which participants with ARDS were reported as a subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

We included pharmacological agents compared to a placebo or to no therapy for the treatment of established ARDS, including any pharmacological agent given for the treatment of established mild ARDS (or ALI) that may prevent the development of ARDS. We included pharmacological agents that were man‐made, natural, or endogenous (from within the body).

We excluded enteral and intravenous therapies that are either not considered to be pharmacological by regulatory authorities (nutritional or herbal interventions) or are combined with other management strategies (fluid management). We excluded therapies that have been reviewed in other Cochrane Reviews: inhaled nitric oxide (Gebistorf 2016); inhaled prostacyclins (Afshari 2017); and partial liquid ventilation (Galvin 2013). We excluded pharmacological therapies used as part of a strategy of mechanical ventilation (neuromuscular blocking agents), and medical oxygen. We excluded studies of activated protein C (APC), which is now a withdrawn drug.

We excluded any pharmacological therapy started for prophylaxis of mild ARDS, even when continued in people who subsequently developed moderate or severe ARDS. We excluded studies directly comparing two pharmacological therapies without a no‐treatment or placebo control group.

Each type of agent represented a different comparison, and we separately analysed data for each comparison group. We selected five primary comparisons in the review.

Corticosteroids versus control

Surfactants versus control

N‐acetylcysteine versus control

Statins versus control

Beta‐agonists versus control

We analysed other types of agents as secondary comparison groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Early all‐cause mortality (at or before three months after randomization). We included ICU and hospital mortality in this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Late all‐cause mortality (more than three months after randomization).

Duration of mechanical ventilation (defined as the time from randomization to extubation, study withdrawal, or death).

Number of ventilator‐free days to day 28 (Schoenfeld 2002).

Adverse events (defined as those leading to discontinuation of the study medication). In studies with a no‐placebo control arm, adverse events were defined as those leading to discontinuation of the study medication, or 'serious adverse events' using study authors' definitions.

Fitness to return to work at 12 months.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified RCTs through literature searching with systematic and sensitive search strategies, as outlined in Chapter 6.4 of theCochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Cochrane Handbook;Higgins 2011). We applied no restrictions to language or publication status. We searched the following databases for relevant trials:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018; Issue 12);

MEDLINE (Ovid SP; 1946 to 10 December 2018);

Embase (Ovid SP; 1974 to 10 December 2018);

CINAHL (EBSCOhost: 1937 to 10 December 2018).

We developed a subject‐specific search strategy in MEDLINE and other listed databases. We developed the search strategy in consultation with the Information Specialist for the Cochrane Emergency and Critical Group. Search strategies can be found in: Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4.

We scanned the following clinical trials registers for ongoing and unpublished trials:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) on 18 December 2018);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) on 10 December 2018.

Searching other resources

We carried out citation searching of identified included studies published since 2010 in Web of Science on 7 January 2019 (apps.webofknowledge.com). We conducted a search of grey literature using Opengrey on 7 January 2019 (www.opengrey.eu/). In addition, we scanned reference lists of relevant systematic reviews which were recently published (since 2015). We did not contact content experts to enquire about additional unpublished trails during the 2019 update.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (SL and either MP, CT, or AS) independently completed data collection on studies written in English or Spanish before comparing results and reaching consensus. One review author (SL) completed data collection using the English abstract for studies written in Chinese; Dr Henry HL Wu completed full data extraction of the Chinese study reports (Acknowledgements). One review author (AS) was available to resolve conflicts if required.

Selection of studies

We used reference management software to collate the results of searches and to remove duplicates (Endnote). We used Covidence 2018 software to screen results of the search of titles and abstracts and to identify potentially relevant studies. We sourced the full texts of all potentially relevant studies and considered whether they met the inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We reviewed abstracts at this stage, and included them in the review only if they provided sufficient information and relevant results that included denominator figures for the intervention and control groups. We recorded the number of papers retrieved at each stage and report this information using a PRISMA flow chart. We reported in the review brief details of closely related but excluded papers.

Data extraction and management

We used Covidence 2018 software to extract data from individual studies. A basic template for data extraction forms is available at www.covidence.org. We adapted this template to include the following information.

Methods: type of study design; setting; dates of study; funding sources and study author declarations of interest.

Participants: number of participants randomized to each group; baseline characteristics (to include: criteria for ARDS diagnosis; time since onset of ARDS; PaO2:FiO2 at baseline; risk factors; Lung Injury Score (LIS) (Murray 1988); and illness severity scores such as 'Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II' (APACHE II).

Intervention: details of pharmacological intervention and control (to include dose, timing and duration of administration), details of any other treatment. We attempted to collect data on clinical management of participants during the study period, which may influence results; we based this on the current guidelines for the management of ARDS, which includes information about: lower tidal volumes, fluid management strategies, neuromuscular blocking agents, positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP), extra‐corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), extra‐corporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCOR), and prone positioning (FICM/ICS Guideline Development Group 2018).

Outcomes: all relevant review outcomes as measured and reported by study authors, including time points of measurement.

Outcome data: results of outcome data

We considered the applicability of information from individual studies and the generalizability of data to our intended study population (i.e. the potential for indirectness in our review). If we found associated publications from the same study, we created a composite data set based on all eligible publications.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SL and either MP or CT) independently assessed study quality, study limitations, and the extent of potential bias by using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). We assessed the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias);

Allocation concealment (selection bias);

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors (performance and detection bias);

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias);

Other potential risks of bias.

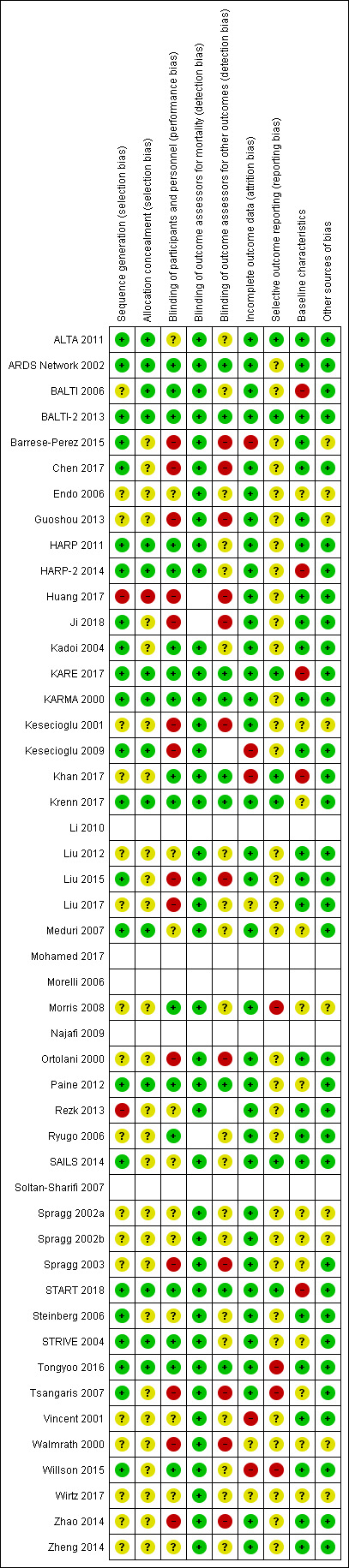

In addition, we assessed comparability of baseline characteristics between study groups, as characteristics such as illness severity may influence response to treatment. For each domain, we judged whether study authors had made sufficient attempts to minimize bias in their study design. We made judgements using three measures: high; low; and unclear risk of bias. We recorded this judgement in 'Risk of bias' tables and present a summary 'Risk of bias' figure (see Figure 2).

Measures of treatment effect

We collected dichotomous data for mortality outcomes, adverse events, and fitness to return to work. We collected continuous data for duration of mechanical ventilation, and number of ventilator‐free days up to day 28. We reported dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) to compare groups, and continuous data as mean differences (MDs). We reported 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

We noted studies that had more than one intervention group. We combined data in intervention groups and compared these combined data with the control group. We used sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of combining data from more than one intervention group in a study.

Dealing with missing data

We considered data to be complete if losses were reported and explained by study authors, and we combined no incomplete data in the meta‐analysis. We did not contact study authors to clarify missing information about study characteristics.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed whether evidence of inconsistency was apparent in our results by considering heterogeneity. We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by comparing similarities in our included studies between study designs, participants, interventions, and outcomes, and used the data collected from the full‐text reports (as stated in Data collection and analysis). We assessed statistical heterogeneity by calculating the Chi2 text or I2 statistic and judged any heterogeneity above an I2 value or 60% and a Chi2 P value of 0.05 or less to indicate moderate to substantial statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

As well as looking at statistical results, we considered point estimates and overlap of CIs. If CIs overlap, then results are more consistent. However, combined studies may show a large consistent effect but with significant heterogeneity. We therefore planned to interpret heterogeneity with caution (Guyatt 2011a).

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to source published protocols for each of our included studies by using clinical trials registers. We compared published protocols with published study results, to assess the risk of selective reporting bias. We planned to generate a funnel plot to assess the risk of publication bias if we identified sufficient studies reporting on an outcome (i.e. more than 10 studies (Sterne 2017)). An asymmetrical funnel plot may suggest publication of only positive results (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We completed meta‐analyses of outcomes for which we had comparable effect measures from more than one study for each comparison group, and when measures of heterogeneity indicated that pooling of results was appropriate. We did not pool studies that had a high level of methodological or clinical heterogeneity. We used the statistical calculator in Review Manager 5 to perform meta‐analysis (Review Manager 2014).

We used the Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model to account for potential variability in participant conditions between studies.

We calculated CIs at 95% and used a P value of 0.05 or less to judge whether a result was statistically significant. We considered imprecision in the results of analyses by assessing the CI around an effect measure; a wide CI would suggest a higher level of imprecision in our results. A small number of studies may also reduce precision (Guyatt 2011b).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform subgroup analysis because we found insufficient studies in each comparison group (i.e. fewer than 10) to enable meaningful analysis (Deeks 2017). If we had found sufficient studies, we planned to perform subgroup analysis as follows:

severity of ARDS: studies with participants meeting the criteria for mild ARDS versus studies with participants meeting the criteria for moderate ARDS; or studies with participants meeting the criteria for moderate ARDS versus studies with participants meeting the criteria for severe ARDS. We used the more recent Berlin definition of ARDS for these cut‐off points (ARDS Definition Task Force 2012);

time since onset of ARDS: early (72 hours or less) versus late (more than 72 hours).

We reported the information collected for these subgroups for each primary comparison group.

Sensitivity analysis

Although we had tried to include studies that only used current guidelines on the clinical management of ARDS by excluding studies published prior to 2000, we found that studies did not consistently or sufficiently report clinical management protocols. The ARDS Network study published in 2000 demonstrated a reduction in mortality when lower tidal volumes were used (ARDS Network 2000). Studies in which this strategy was not used may therefore not be generalizable to current management of people with ARDS, and we excluded these studies during sensitivity analysis in order to explore this potential effect on the results.

We also explored the potential effect of decisions made as part of the review process. We performed the following sensitivity analysis on our primary outcome (early all‐cause mortality) in our primary comparisons in this review.

We excluded studies in which use of lower tidal volumes was not reported.

We excluded studies that we judged at high or unclear risk of selection bias.

We excluded studies that we judged to have high risk of attrition bias because of missing data which were unbalanced between groups, and unexplained.

We conducted meta‐analysis using the alternative meta‐analytic effects model (i.e. fixed‐effect).

In multi‐arm studies in which data from more than one intervention group were combined, we separately included data for each arm in analysis.

In each sensitivity analysis we compared the effect estimate with the main analysis. We reported these effect estimates only if they indicated a difference in interpretation of the effect.

Summary of findings' tables and GRADE

One review author (SL) used the GRADE system to assess the certainty of the body of evidence associated with the following outcomes (Guyatt 2008):

early all‐cause mortality (at or before three months after randomization);

late all‐cause mortality (more than three months after randomization);

duration of mechanical ventilation;

number of ventilator‐free days to day 28;

adverse events;

fitness to return to work at 12 months.

The GRADE approach appraises the certainty of a body of evidence based on the extent to which we can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Evaluation of the certainty of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias, directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of the effect estimates, and risk of publication bias.

We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADE profiler software for the following comparisons in this review (GRADEpro GDT):

corticosteroids versus control (Table 1);

surfactants versus control (Table 2);

N‐acetylcysteine versus control (Table 3);

statins versus control (Table 4);

beta‐agonists versus control (Table 5).

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Corticosteroids compared to control for adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

| Corticosteroids compared to control for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||||

|

Population: adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome

Setting: intensive care units in: China; Kuwait; Thailand; and USA Intervention: corticosteroids (methylprednisolone; hydrocortisone; and budesonide Comparison: control (placebo or standard therapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with corticosteroids | |||||

|

Early all‐cause mortality (≤ 3 months) Reported at: day 14; day 28; day 60; and in hospital |

Study population | RR 0.77 (0.57 to 1.05) | 574 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

‐ | |

| 374 per 1000 | 288 per 1000 (213 to 393) | |||||

|

Late all‐cause mortality ( > 3 months) Reported at: 180 days |

Study population | RR 0.99 (0.64 to 1.52) | 180 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb |

‐ | |

| 319 per 1000 | 315 per 1000 (204 to 484) | |||||

|

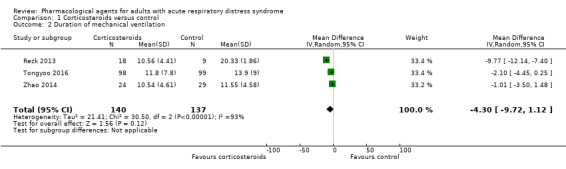

Duration of mechanical ventilation Measured in days |

In the control group, mean values range from 11.6 days to 20.3 days | MD 4.30 days lower (9.72 days lower to 1.12 days higher) | ‐ | 277 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

We did not include 1 additional study (91 participants) in the analysis because data were reported as median values; study authors reported a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation with corticosteroids use |

| Ventilator‐free days up to day 28 | In the control group, mean values range from 6.8 days to 12.8 days | MD 4.09 days higher (1.74 higher to 6.44 higher) | ‐ | 494 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd |

‐ |

|

Adverse events Defined as leading to discontinuation of study medication; or for studies with standard care control, defined by study authors as "serious adverse events" |

‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies reported or measured this outcome |

| Fitness to return to work at 12 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies reported or measured this outcome |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aWe downgraded one level for study limitations (risks of bias were uncertain or high amongst studies), and by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants). bWe downgraded by one level for study limitations (we were unable to assess risk of reporting bias because of retrospective clinical trial registration and analysis was completed post hoc), and by two levels for imprecision (evidence was from one study with few participants). cWe downgraded by one level for study limitations (risks of bias were uncertain or high amongst studies), by one level for inconsistency (evidence of substantial statistical heterogeneity) and by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants). dWe downgraded by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants), and by one level for inconsistency (we noted a wide confidence interval in the effect estimate).

Summary of findings 2. Surfactants compared to control for adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

| Surfactants compared to control for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||||

| Population: adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome Setting: intensive care units in: Austria, Belgium; Canada; Cuba; Europe (one multicentre study did not report countries within Europe); Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Netherlands; Norway; South Africa; Spain; Sweden; UK; USA Intervention: surfactants (surfacen; HL10; venticute; alveofact; calfactant) Comparison: control (placebo or standard therapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with surfactants | |||||

|

Early all‐cause mortality (≤ 3 months) Reported at: 28 days; and 90 days. Time point not reported in 4 studies |

Study population | RR 1.08 (0.91 to 1.29) | 1338 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa |

‐ | |

| 284 per 1000 | 307 per 1000 (259 to 367) | |||||

|

Late all‐cause mortality ( > 3 months) Reported at: 180 days |

Study population | RR 1.28 (1.01 to 1.61) | 418 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb |

‐ | |

| 362 per 1000 | 463 per 1000 (366 to 583) | |||||

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation Measured in days |

In the control mean duration was 8.1 days | MD 2.5 days lower (4.95 days lower to 0.05 days lower) | ‐ | 16 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

We did not include 1 additional study (48 participants) in analysis because values of data (mean or median) were unclear; study authors reported little or no difference between groups in duration of mechanical ventilation |

| Ventilator‐free days up to day 28 | In the control group, mean values range from 11.9 days to 13 days | MD 0.39 days lower (2.49 days lower to 1.72 days higher) | ‐ | 344 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd |

We did not include 4 additional studies (512 participants) in analysis because data were not reported sufficiently; 3 studies reported little or no difference between groups, and 1 study reported more ventilator‐free days in the intervention group |

|

Adverse events Defined as leading to discontinuation of study medication; data collected during study period |

Study population | RR 0.50 (0.17 to 1.44) |

88 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe |

‐ | |

| 216 per 1000 |

108 per 1000 (37 to 311) |

|||||

| Fitness to return to work at 12 months | ‐ | Not estimable | No studies reported or measured this outcome | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aWe downgraded by three levels; by two levels for study limitations (studies comparing surfactants with standard therapy were all at high risk of performance bias, and we noted other risks of bias that were high or unclear amongst studies), and by one level for inconsistency (we noted some differences in data between studies and we found too few studies to explore these differences through subgroup analyses). bWe downgraded by three levels; by two levels for study limitations (study was at high and unclear risks of bias), and by one level for imprecision (evidence was from a single study). cWe downgraded by three levels; by one level for study limitations (studies were at high risk of performance bias), by one level for inconsistency (we noted differences in data between studies), and by one level for imprecision (evidence was from two studies with few participants). dWe downgraded by three levels; by two levels for study limitations (studies comparing surfactants with standard therapy were all at high risk of performance bias, and we noted other risks of bias that were high or unclear amongst studies), and by one level for inconsistency (we noted differences in data between studies). eWe downgraded by three levels; by two levels for study limitations (studies comparing surfactants with standard therapy were at high risk of performance bias, and we noted other risks of bias that were high or unclear amongst studies), and by one level for imprecision (evidence was from two studies with few participants).

Summary of findings 3. N‐acetylcysteine compared to control for adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

| N‐acetylcysteine compared to control for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||||

| Population: adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome Setting: intensive care unit in: Italy Intervention: N‐acetylcysteine Comparison: control (placebo) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with N‐acetylcysteine | |||||

|

Early all‐cause mortality (≤ 3 months) Reported at: 30 days |

Study population | RR 0.64 (0.32 to 1.30) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa |

‐ | |

| 583 per 1000 | 373 per 1000 (187 to 758) | |||||

| Late all‐cause mortality ( > 3 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| Ventilator‐free days up to day 28 | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

|

Adverse events Defined as leading to discontinuation of study medication |

‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| Fitness to return to work at 12 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aWe downgraded by three levels; by one level for study limitations (unblinded study at high risk of performance bias). and by two levels for imprecision (evidence from one study with few participants).

Summary of findings 4. Statins compared to control for adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

| Statins compared to control for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||||

| Population: adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome Setting: intensive care units in: Northern Ireland; UK; USA Intervention: statins (simvastatin; and rosuvastatin) Comparison: control (placebo) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with statins | |||||

|

Early all‐cause mortality (≤ 3 months) Reported at: 60 days; and during hospital stay |

Study population | RR 0.99 (0.78 to 1.26) | 1344 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

‐ | |

| 262 per 1000 | 259 per 1000 (204 to 330) | |||||

| Late all‐cause mortality ( > 3 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation Measured in days |

In the control group, mean duration was 15.9 days | MD 2.70 days higher (0.35 days lower to 8.95 days higher) | ‐ | 60 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb |

‐ |

| Ventilator‐free days up to day 28 | In the control group, mean values range from 9.1 days to 15.1 days | MD 0.40 days higher (0.71 days lower to 1.52 days higher) | ‐ | 1342 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec |

‐ |

|

Adverse events Defined as leading to discontinuation of study medication |

‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | One study measured discontinuation of treatment because of an adverse event, but data were not reported by study authors |

| Fitness to return to work at 12 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aWe downgraded by one level for inconsistency; we noted some differences in data between studies and we found too few studies to explore these differences through subgroup analyses. bWe downgraded by two levels for imprecision; evidence was from one study with few participants. cWe downgraded by one level for inconsistency; we noted some differences in data between studies and we found too few studies to conduct subgroup analyses to explore these differences.

Summary of findings 5. Beta‐agonist compared to control for adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

| Beta‐agonist compared to control for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome | ||||||

| Population: adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome Setting: intensive care units in: UK; and USA Intervention: beta‐agonist (salbutamol; and albuterol) Comparison: control (placebo) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with beta‐agonist | |||||

|

Early all‐cause mortality (≤ 3 months) Reported at: 28 days; 60 days; and during hospital stay |

Study population | RR 1.14 (0.91 to 1.42) | 646 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

‐ | |

| 283 per 1000 | 323 per 1000 (258 to 402) | |||||

| Late all‐cause mortality (> 3 months | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| Ventilator‐free days up to day 28 | In the control group, mean values range from 5.3 days to 16.6 days | MD 2.20 days lower (3.68 days lower to 0.71 days lower) | ‐ | 646 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb |

‐ |

|

Adverse events Defined as leading to discontinuation of study medication; data collected during study period |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 606 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

We did not pool data in 2 studies because of potential differences in types of adverse events. 1 study reported little or no difference between groups; and 1 study reported more adverse events when participants were given beta‐agonists |

| Fitness to return to work at 12 months | ‐ | ‐ | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | No studies measured or reported this outcome |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aWe downgraded by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants). bWe downgraded by three levels; by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants), and by two levels for inconsistency (inspection of data showed differences in direction of effect between studies which we could not explain). cWe downgraded by three levels; by one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants), and by two levels for inconsistency (inspection of data showed differences in direction of effect between studies, and a high level of statistical heterogeneity, which may be due caused by differences in types of adverse events measured by study authors).

Because of the broad range of types of pharmacological agents eligible for inclusion in this review, it was not feasible to produce a 'Summary of findings' table for each type of agent. Our choice of comparisons for the 'Summary of findings' tables was based on agents which are most commonly used and recognized in a global clinical setting, and followed advice given by the Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care Group.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

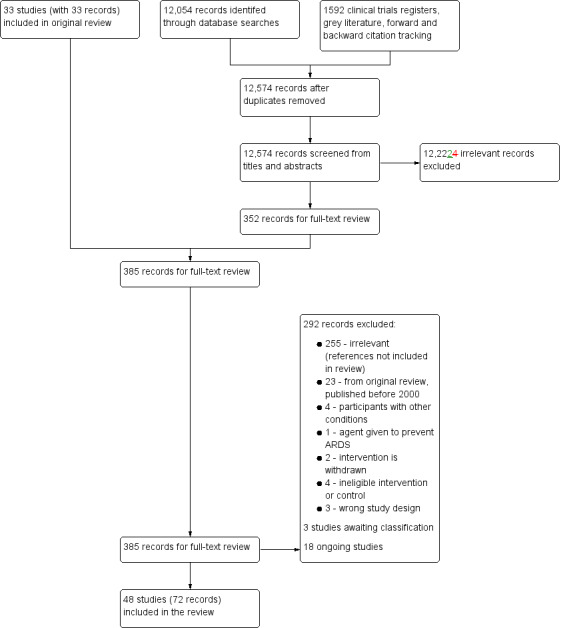

We screened 12,574 titles and abstracts, which included forward‐ and backward‐citation searches, clinical trials registers and grey literature. We sourced 352 full‐text reports to assess eligibility (Figure 1).

1.

Flow diagram for searches conducted since publication of the last version of the Review up to 10 December 2018

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies. A summary of study characteristics for the primary comparisons is included in Appendix 5.

We included 48 RCTs (72 publications) with 6299 participants (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013; Barrese‐Perez 2015; Chen 2017; Endo 2006; Guoshou 2013; HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; Huang 2017; Ji 2018; Kadoi 2004; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2001; Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; Li 2010; Liu 2012; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Meduri 2007; Mohamed 2017; Morelli 2006; Morris 2008; Najafi 2009; Ortolani 2000; Paine 2012; Rezk 2013; Ryugo 2006; SAILS 2014; Soltan‐Sharifi 2007; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Spragg 2003; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Vincent 2001; Walmrath 2000; Willson 2015; Wirtz 2017; Zhao 2014; Zheng 2014).

Five studies were conducted by the ARDS Clinical Trials Network (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; KARMA 2000; SAILS 2014; Steinberg 2006). if the studies were known by acronyms, we used them for study names, rather than study author names. We included five studies for which we could only source the abstract and this limited the details of study characteristics that we were able to extract (Kesecioglu 2001; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Walmrath 2000; Wirtz 2017). We sourced the full text of all remaining studies.

Study population

Twenty studies included participants that had ARDS defined by the AECC (ARDS Network 2002; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013; Barrese‐Perez 2015; HARP 2011; Kadoi 2004; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; Liu 2012; Liu 2015; Meduri 2007; Paine 2012; Spragg 2003; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Vincent 2001; Willson 2015; Zhao 2014). Only two studies used the more recent Berlin definition (Mohamed 2017; Zheng 2014). Guoshou 2013 used criteria from the Society of Critical Care Medicine of Chinese Medicine Association (SCCMCMA 2006). The remaining studies did not reference the criteria that they used to define ARDS.

We attempted to differentiate the severity of ARDS in the included studies using the Berlin definition of ARDS (ARDS Definition Task Force 2012). However, we found it was not possible to do this precisely for each study because of a lack of detail in study reports. We used only the measure of PaO2/FiO2 to distinguish between severities of ARDS, because these data were most commonly (although not consistently) reported in studies. Two studies included only participants with mild ARDS (defined by the study authors as ALI, with a PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg) (Li 2010; Ryugo 2006). The remaining studies included participants with a mean PaO2/FiO2 value which was ≤ 200 mmHg but was likely to include participants that had mild, moderate, and severe ARDS; we expected from the mean values that most participants had moderate ARDS.

Most studies included ARDS with a risk factor from both direct and indirect causes, with pneumonia and sepsis often reported as the most frequent cause. Five studies reported inclusion of participants with only specific risk factors, which were: trauma (Endo 2006); heatstroke (Chen 2017); sepsis (Liu 2015; Morelli 2006); systematic inflammatory response syndrome after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (Ryugo 2006); blunt chest trauma (Tsangaris 2007).

Although we hoped to extract sufficient data on clinical management of participants relating to current ICU guidelines on ARDS (FICM/ICS Guideline Development Group 2018), we found that this was generally poorly reported in studies. No studies reported whether practitioners followed all aspects of clinical management that we had hoped to collect during data extraction (lower tidal volumes, fluid management strategies, neuromuscular blocking agents, positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP), extra‐corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), extra‐corporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCOR), and prone positioning). We found that 25 studies reported the use of lower tidal volumes to manage ventilation (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; Chen 2017; HARP‐2 2014; KARE 2017; Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; Liu 2012; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Meduri 2007; Mohamed 2017; Morelli 2006; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Willson 2015; Zhao 2014; Zheng 2014), with many studies using the ARDS Network low tidal volume protocol (ARDS Network 2000). However, compliance with this lung protection strategy was not reported.

Study setting

All studies were conducted in hospital settings; even if not reported, we expected participants to be recruited in ICUs. Twenty‐three were multicentre studies (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; Chen 2017; HARP‐2 2014; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2001; Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Liu 2017; Meduri 2007; Morris 2008; Ortolani 2000; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; Spragg 2003; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Vincent 2001; Walmrath 2000; Willson 2015). The centre was unclearly reported in four studies (Endo 2006; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Wirtz 2017). The remaining studies were conducted in a single centre.

Interventions and comparisons

For the primary comparisons, we found:

seven studies (643 participants) that assessed corticosteroids which were: hydrocortisone (Liu 2012; Tongyoo 2016); methylprednisolone (Meduri 2007; Rezk 2013; Steinberg 2006); or budesonide (Mohamed 2017; Zhao 2014). One study used standard therapy in the control group (Zhao 2014); the remaining studies were compared with a placebo or control agent;

nine studies (1340 participants) compared surfactants with either a placebo (Willson 2015), or standard therapy (Barrese‐Perez 2015; Kesecioglu 2001; Kesecioglu 2009; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Spragg 2003; Tsangaris 2007; Walmrath 2000). Spragg 2003 was a three‐arm study which compared a high dose and a low dose of surfactant with a placebo;

three studies (86 participants) compared N‐acetylsysteine with either standard therapy (Najafi 2009; Soltan‐Sharifi 2007), or a placebo (Ortolani 2000). Ortolani 2000 was a three‐arm study that included a N‐acetylcysteine group and a N‐acetylcysteine with rutin group;

three studies (1345 participants) compared statins with a placebo (HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; SAILS 2014);

three studies (648 participants) compared a beta‐agonist with a placebo (ALTA 2011; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013).

For the secondary comparison of other pharmacological agents, we found:

four studies (556 participants) compared sivelestat (Endo 2006; Kadoi 2004; Ryugo 2006; STRIVE 2004). Endo 2006 did not report any information on the control group such as whether a placebo or standard treatment was used as a comparison; the remaining studies compared the agent with a placebo control;

two studies (75 participants) compared mesenchymal stem cells, which were: allogeneic adipose‐derived (Zheng 2014); and allogeneic bone marrow‐derived (START 2018);

two studies (110 participants) compared ulinastatin with standard therapy (Chen 2017; Ji 2018);

one study (50 participants) compared anisodimine with standard therapy (Guoshou 2013);

one study (61 participants) compared ACE inhibitor (Enalaprilat) with a placebo control (Wirtz 2017);

one study (39 participants) compared recombinant human angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (rhACE2) with a placebo control (Khan 2017);

one study (60 participants) compared recombinant human keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) (Palifermin) with a placebo control (KARE 2017)

one study (132 participants) compared recombinant human granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) with a placebo control (Paine 2012);

one study (40 participants) compared AP301 with a placebo control (Krenn 2017);

one study (35 participants) compared levosimendan with a placebo control (Morelli 2006);

two studies (167 participants) compared prostacyclins given intravenously: liposomal prostaglandin‐E1 (PGE1) with a placebo (Vincent 2001), and alprostadil with standard care (Liu 2017);

one study (235 participants) compared lisofylline with a placebo control (ARDS Network 2002);

one study (234 participants) compared ketaconazole with a placebo control (KARMA 2000);

two studies (205 participants) compared nitroglycerin with standard care (Huang 2017; Liu 2015). In Huang 2017, nitroglycerin was given alongside propofol administration;

one study (215 participants) compared L‐2‐oxothiazolidine‐4‐carboxylic acid (OTZ) with a placebo (Morris 2008);

one study (45 participants) compared penehyclidine hydrochloride with standard therapy (Li 2010).

Outcomes

Five studies reported no outcomes relevant to the review (Li 2010; Mohamed 2017; Morelli 2006; Najafi 2009; Soltan‐Sharifi 2007).

Of the remaining studies, only three studies did not report data for early mortality (Huang 2017; Ji 2018; Ryugo 2006). Five studies reported data for late mortality (KARE 2017; Kesecioglu 2009; Paine 2012; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004). Nineteen studies reported duration of mechanical ventilation (Barrese‐Perez 2015; Chen 2017; Endo 2006; Guoshou 2013; HARP 2011; Huang 2017; Ji 2018; Kadoi 2004; KARE 2017; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Meduri 2007; Paine 2012; Rezk 2013; Ryugo 2006; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Vincent 2001; Zhao 2014). Twenty‐six studies reported ventilator‐free days up to day 28 (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013; HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2001; Krenn 2017; Liu 2012; Meduri 2007; Morris 2008; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Spragg 2003; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Walmrath 2000; Willson 2015; Wirtz 2017; Zheng 2014). Nine studies reported adverse events that led to the discontinuation of study medication (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; Barrese‐Perez 2015; Guoshou 2013; HARP‐2 2014; KARMA 2000; Morris 2008; Spragg 2003). We found no studies reporting the long‐term outcome of fitness to return to work at 12 months.

Funding sources

Eight studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies (Kesecioglu 2001; Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; Morris 2008; STRIVE 2004; Walmrath 2000; Willson 2015), or by combined funding that included pharmaceutical funding (KARE 2017; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; Spragg 2003). Of these studies, we noted the involvement of the funders in the study design, implementation, and interpretation of the results in four studies (Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; STRIVE 2004; Willson 2015).

Early stopping

Thirteen studies were stopped early (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; HARP‐2 2014; Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Morris 2008; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; STRIVE 2004; Vincent 2001; Willson 2015; Wirtz 2017). Of these, only three studies did not report whether the decision to terminate the trial was made by an independent monitoring board (Khan 2017; Morris 2008; Wirtz 2017). The decision in one study was made by the investigators, who were employees of the funders (Willson 2015). We reported reasons for early stopping in Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 292 articles following review of full‐text. We report on 37 studies in the review which we identify as key excluded studies. A brief description of these studies, and the reason for exclusion, is reported in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Twenty‐three of these studies were in the previous version of this review (Adhikari 2004); we excluded them because they were published before 2000 (Abraham 1996; Abraham 1999; Anzueto 1996; Ardizzoia 1993; Bernard 1987; Bernard 1997; Bernard 1999; Bone 1989; Domenighetti 1997; Gottlieb 1994; Gregory 1997; Holcroft 1986; Jepsen 1992; Meduri 1998; Reines 1985; Reines 1992; Rossignon 1990; Shoemaker 1986; Steinberg 1990; Suter 1994; Tuxen 1987; Weg 1994; Weigelt 1985). In addition, we excluded four studies which included participants that did not exclusively have ARDS (Bastin 2010; Bastin 2016; Confalonieri 2005; Presneill 2002), one study in which the agent was given to prevent rather than to treat ARDS (Shyamsundar 2010), two studies that assessed an agent which is now withdrawn from the market (Cornet 2014; Liu 2008), three studies that assessed a neuromuscular blocking agent (Forel 2006; Gainnier 2004; Papazian 2010), one study that did not have a control group (Hua 2013), and three studies that were an ineligible study design (Annane 2006; Markart 2007; Vincent 2009).

Studies awaiting classification

We found three studies awaiting classification (Hegazy 2016; NCT00879606; RPCEC00000126). Hegazy 2016 assessed the use of nebivol; this study is published only as an abstract, with insufficient information to assess eligibility. During our search of clinical trials registers, we found two studies that were completed but for which results have not yet been published; these studies assessed recombinant chimeric anti‐tissue factor antibody ALT‐83 (NCT00879606), and surfactants (RPCEC00000126). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification

Ongoing studies

We found 18 ongoing studies (ACTRN12612000418875; ACTRN12615000373572; Bellingan 2017; ChiCTR1800014733; ChiCTR1800014998; EUCTR2012‐000775‐17; JPRN‐JapicCTI‐163320; Villar 2016; NCT02326350; NCT02595060; NCT02611609; NCT02895191; NCT03017547; NCT03042143; NCT03202394; NCT03346681; NCT03371498; NCT03608592). Agents assessed in these trials are: heparin; corticosteroids; mesenchymal stem cells; Multistem; rhGM‐CSF; dexamethasone; aspirin; N‐acetylcysteine; ulinastatin; FP‐1201‐lyo; MR11A8; IC‐ 14; and BIO‐11006. Estimated recruitment in these studies is 2068 participants. See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

See 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for included studies in which outcome data is reported. Blank spaces in tables indicate that study authors did not report review outcomes.

We did not complete 'Risk of bias' assessments for studies in which no review outcomes were reported (Li 2010; Mohamed 2017; Morelli 2006; Najafi 2009; Soltan‐Sharifi 2007).

We did not assess risk of detection bias for either mortality or other outcomes if these were not reported by study authors.

Blank spaces in the 'Risk of bias' figure indicate that we did not conduct 'Risk of bias' assessments.

Allocation

We judged 23 studies to have low risk of selection bias for sequence generation, because study authors reported sufficient methods for randomization (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; Barrese‐Perez 2015; Chen 2017; HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; Ji 2018; Kadoi 2004; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2009; Krenn 2017; Liu 2015; Meduri 2007; Paine 2012; SAILS 2014; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Willson 2015). One study did not report sufficient methods for randomization; because we noted an unexplained uneven number of participants in each group, we judged this study to have high risk of selection bias for sequence generation (Rezk 2013). We judged one study to have high risk of selection bias because of methods used to randomize participants to groups using folded‐up paper (Huang 2017). Remaining studies reported insufficient methods of sequence generation, and we judged these to be at an unclear risk of bias.

We judged 15 studies to have low risk of bias for allocation concealment, because study authors reported sufficient methods for this judgement (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013; HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2009; Krenn 2017; Meduri 2007; Paine 2012; START 2018; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016). In Huang 2017, we judged that allocation could not be effectively concealed and we judged this study to have a high risk of bias. Remaining studies reported insufficient details, and we judged them to be at an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

We judged all studies that used standard therapy control, rather than placebo control, to be at high risk of performance bias (Barrese‐Perez 2015; Chen 2017; Guoshou 2013; Huang 2017; Ji 2018; Kesecioglu 2001; Kesecioglu 2009; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Spragg 2003; Tsangaris 2007; Walmrath 2000; Zhao 2014). In addition, one placebo‐controlled trial was described as unblinded by the study authors, and we judged this study to be at risk of performance bias (Ortolani 2000). Twelve studies reported insufficient information, and we judged these to have an unclear risk of performance bias (ALTA 2011; Endo 2006; Liu 2012; Meduri 2007; Rezk 2013; SAILS 2014; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Steinberg 2006; Vincent 2001; Wirtz 2017; Zheng 2014). We judged the remaining studies to be at a low risk of performance bias.

For detection bias, we did not expect lack of blinding to influence outcome assessment of mortality, and we judged all studies that reported mortality data (including those in which blinding was not possible) to have low risk of detection bias for this outcome. However, we judged studies that used standard therapy control to have a high risk of detection bias for other reported outcomes (Barrese‐Perez 2015; Chen 2017; Guoshou 2013; Ji 2018; Kesecioglu 2001; Li 2010; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Najafi 2009; Spragg 2003; Tsangaris 2007; Walmrath 2000; Zhao 2014). We judged one placebo‐controlled study to have a high risk of detection bias. Only nine studies adequately reported blinding of outcome assessors for all outcomes, and we judged these studies to have a low risk of detection bias for other reported outcomes (ARDS Network 2002; BALTI‐2 2013; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; Paine 2012; START 2018; Tongyoo 2016). Remaining studies did not report sufficient information about blinding outcome assessors, and we judged these studies to have an unclear risk of detection bias for other reported outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged 36 studies to have a low risk of attrition bias because study authors reported no participant losses or few losses (less than 10%) (ALTA 2011; ARDS Network 2002; BALTI 2006; BALTI‐2 2013; Chen 2017; Endo 2006; Guoshou 2013; HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; Huang 2017; Ji 2018; Kadoi 2004; KARE 2017; KARMA 2000; Kesecioglu 2001; Krenn 2017; Liu 2012; Liu 2015; Liu 2017; Meduri 2007; Morris 2008; Ortolani 2000; Paine 2012; Rezk 2013; Ryugo 2006; SAILS 2014; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Spragg 2003; START 2018; Steinberg 2006; STRIVE 2004; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Zhao 2014; Zheng 2014).

We judged five studies to have a high risk of attrition bias; in one study we were concerned by uneven numbers of participants who did not complete treatment (Barrese‐Perez 2015), and in four studies we were concerned about the influence of early stopping on the results (Kesecioglu 2009; Khan 2017; Vincent 2001; Willson 2015).

We could not ascertain loss of participants in two studies reported as abstracts because of insufficient information (Walmrath 2000; Wirtz 2017)

Selective reporting

We found only seven studies with prospective clinical trials registration and outcome information reported equivalently in the clinical trials registration documents and the published completed study report (ALTA 2011; BALTI‐2 2013; KARE 2017; Khan 2017; Krenn 2017; SAILS 2014; START 2018).

Three studies were prospectively registered with clinical trials registers, but we noted discrepancies and could not effectively assess risks of reporting bias for these studies (HARP 2011; HARP‐2 2014; Paine 2012); we judged these as having unclear risk of bias.

We judged four studies to have a high risk of reporting bias (Morris 2008; Tongyoo 2016; Tsangaris 2007; Willson 2015). Morris 2008 declared that some data were held by the sponsors who had chosen not to publish the data because of negative results. We were concerned about discrepancies between the clinical trials registration documents and the published completed study reports in Tongyoo 2016 and Willson 2015, In Tsangaris 2007, outcome data were only reported briefly, and some adverse events listed in the Methods section of the study report were omitted from the Results section.

Remaining studies did not report pre‐published protocols or report registration with clinical trials registers, and it was therefore not feasible to assess risk of reporting bias.

Baseline characteristics

We noted some differences baseline characteristics in five studies, which we rated at high risk of bias because differences in these characteristics could influence outcome data (BALTI 2006; HARP‐2 2014; KARE 2017; Khan 2017; START 2018). We also noted differences in the baseline characteristics of six studies, and rated them at unclear risk of bias because we were uncertain whether these characteristics could influence outcome data (Krenn 2017; Meduri 2007; Paine 2012; Spragg 2003; STRIVE 2004; Tsangaris 2007).

Seven studies did not provide sufficient information on baseline characteristics to allow a judgement (Endo 2006; Kesecioglu 2001; Morris 2008; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Walmrath 2000; Wirtz 2017).

We judged the remaining studies to have a low risk of bias because baseline characteristics were comparable between groups.

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies were abstracts and, because of insufficient information, it was not possible to assess whether other risks of bias were present (Kesecioglu 2001; Spragg 2002a; Spragg 2002b; Walmrath 2000; Wirtz 2017).

In addition, we judged four studies to have unclear risks of other bias: two did not report details of standard therapy control (Endo 2006; Guoshou 2013), and two studies excluded a large number of participants before randomization (Barrese‐Perez 2015; Morris 2008).

We noted no other potential sources of bias in the remaining studies, and judged these to have low risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Corticosteroids versus control

Primary outcome

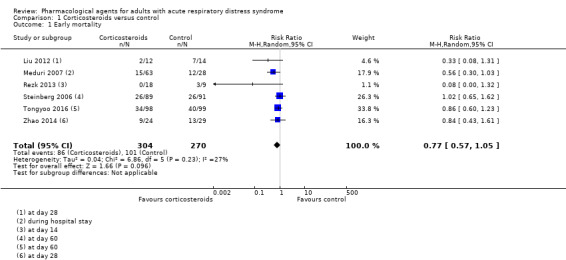

Early all‐cause mortality

Six studies reported early mortality for 574 participants (Liu 2012; Meduri 2007; Rezk 2013; Steinberg 2006; Tongyoo 2016; Zhao 2014). We included data collected at the latest time point which was: day 14 (Rezk 2013); day 28 (Liu 2012; Zhao 2014); day 60 (Steinberg 2006; Tongyoo 2016); and in hospital (Meduri 2007).

Corticosteroids may reduce the number of deaths from any cause within three months by 86 per 1000 patients (with as many as 161 fewer or 19 more deaths). However, we note that the 95% confidence interval (CI) includes the possibility of both increased and reduced deaths (risk ratio (RR) 0.77, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.05; I2 = 27%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). We used GRADE to downgrade the certainty of the evidence by two levels; one level for study limitations (risks of bias were uncertain or high amongst studies) and one level for imprecision (evidence was from few studies with few participants). See Table 1,

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus control, Outcome 1 Early mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Late all‐cause mortality