ABSTRACT

Background

Most evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of the antithrombotic regimens for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stent (PCI‐S) derives from small, single‐center, retrospective datasets. To obtain further data on this issue, we carried out the prospective, multicenter, observational Management of patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting (AFCAS) registry (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00596570).

Hypothesis

We hypothesize that the antithrombotic treatment of AF patients undergoing PCI‐S is variable and the clinical outcome may vary according to the different regimens.

Methods

Consecutive AF patients undergoing PCI‐S at 17 European institutions were included and followed for 1 year. Outcome measures included: (1) major adverse cardiac/cerebrovascular events (MACCE), including all‐cause death, myocardial infarction, repeat revascularization, stent thrombosis, or stroke/transient ischemic attack, and (2) bleeding, and were compared according to the antithrombotic regimen adopted. A propensity‐score analysis was carried out to adjust for baseline and procedural differences.

Results

Out of the 975 patients enrolled, 914 were included in the final analysis. The mean CHADS2 score was 2.2 ± 1.2, and 71% of patients had a CHADS2 score ≥2. Triple therapy (TT) of vitamin K antagonist (VKA), aspirin, and clopidogrel was prescribed to 74% of patients, dual antiplatelet therapy to 18%, and VKA plus clopidogrel to 8%. At 1‐year follow‐up, no significant differences were found in the occurrence of MACCE and bleeding among the 3 antithrombotic regimens, even when adjusted for propensity score.

Conclusions

In this large, real‐world population of AF patients undergoing PCI‐S, TT was the antithrombotic regimen most frequently prescribed. Although several limitations need to be acknowledged, in our study the 1‐year efficacy and safety of TT, dual antiplatelet therapy, and VKA plus clopidogrel was comparable.

Introduction

In accordance with consensus documents and guidelines, the antithrombotic therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at increased risk of thromboembolism (ie, CHADS2 score ≥2) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stent (PCI‐S) should consist of triple therapy (TT) of vitamin K antagonist (VKA), aspirin, and clopidogrel.1, 2, 3 Most data upon which the current recommendations are based derive from small, single‐center, retrospective datasets, and the level of evidence supporting these recommendations is generally weak.1, 2, 3 More recent data from large, Danish, nationwide registries4, 5, 6, 7 and the WOEST (What is the Optimal Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients with Oral Anticoagulation and Coronary Stenting) study,8 where patients on oral anticoagulation (because of AF, mechanical heart valve, or other) were prospectively randomized to TT or a combination of VKA plus clopidogrel (VKA/C), have questioned the overall validity of current recommendations by showing that VKA/C may have comparable, or even superior, safety and efficacy to TT. Also, the antithrombotic treatment actually ongoing at the time of an adverse event, especially bleeding, has been rarely reported, therefore making questionable the attribution of adverse event to the antithrombotic regimen prescribed at discharge.9

To obtain further data on the current management of AF patients undergoing PCI‐S and define the absolute and relative efficacy and safety of the various antithrombotic regimens, we carried out the Management of patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Coronary Artery Stenting (AFCAS) registry.

Methods

AFCAS is an observational, multicenter, prospective registry where consecutive AF patients undergoing PCI‐S were included (Clinicaltrials.govidentifier NCT00596570). The inclusion criterion was ongoing/history of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent). Because of the observational design, the only exclusion criteria were unwillingness/inability to participate in the study or to give informed consent. At each participating center, patients were treated according to local policies, and were followed up for 1 year. Ethics committees of participating centers approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from every patient. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PCI‐S was performed according to local practice. The periprocedural management was at the operator's discretion. Follow‐up was performed at each enrolling center by means of telephone calls/clinic visits, which were scheduled at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after PCI‐S. Patients were asked about their clinical outcomes, hospitalizations, and medications, and the information was collected.

The outcome measures were: (1) major adverse cardiac/cerebrovascular events (MACCE), including all‐cause death, myocardial infarction, repeat revascularization, stent thrombosis (ST), and stroke/transient ischemic attack; (2) bleeding; and (3) total adverse events (MACCE plus bleeding). Myocardial infarction was defined according to the universal definition.10 Repeat revascularization was defined as PCI‐S or coronary bypass surgery in the previously treated vessel. ST was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium classification and included definite and probable events.11 Transient ischemic attack was defined as a focal, transient (<24 hours) neurological deficit adjudicated by a neurologist, whereas stroke was defined as a permanent, focal, neurological deficit adjudicated by a neurologist and confirmed by computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Systemic embolism was defined as signs/symptoms of peripheral ischemia associated or not with a positive imaging test. Bleeding was defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) classification as minor (BARC 2), and major (BARC 3a, 3b, 3c, and 5).12

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as percentage. Independent samples t test and χ2 test were used for the analysis of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Fisher exact, Mann‐Whitney, Kruskall‐Wallis, and Kaplan‐Meier tests were used for univariate analysis.

To adjust for potential selection bias, a multilevel propensity score was calculated by multinomial logistic regression. Clinical variables with a P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in multinomial logistic regression. TT was selected as the reference. The obtained propensity score was employed only for adjustment of the risk in Cox proportional hazards regression. Propensity score‐adjusted analysis was not performed for the VKA plus clopidogrel group because of the small size. Kaplan‐Meier and Cox proportional hazards regression were employed for analysis of time‐to‐event outcomes. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis was performed using a SPSS, versions 16 and 20, statistical software (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Out of the 975 consecutive patients enrolled between October 2008 and August 2010 at 17 institutions in 5 European countries, 61 (6%) were not included in the analysis because they were prescribed either oral anticoagulant only, or single antiplatelet drug, or the combination of VKA and aspirin. Thus, 914 patients were included in the final analysis. TT was prescribed to 679 patients (74%), dual antiplatelet therapy of aspirin and clopidogrel (DAPT) to 162 (18%), and VKA/C to 73 (8%). Baseline characteristics, both overall and according to the adopted antithrombotic regimen, are presented in Table 1. Procedural variables, again both overall and according to the antithrombotic regimen, are presented in the Supporting Table online, as the in‐hospital management and outcome has been reported in detail elsewhere.13

Table 1.

Baseline Patients' Characteristics

| Total, n = 914 | TT, n = 679 | DAPT, n = 162 | VKA/C, n = 73 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 73 ± 8 | 73 ± 8 | 73 ± 8 | 74 ± 8 | 0.70 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 639 (70) | 482 (71) | 105 (65) | 52 (71) | 0.30 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 ± 4.7 | 28 ± 4.7 | 28 ± 4.7 | 28 ± 4.4 | 0.13 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 770 (84) | 568 (84) | 142 (88) | 60 (82) | 0.40 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 610 (67) | 456 (67) | 108 (67) | 46 (63) | 0.78 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 333 (36) | 252 (37) | 54 (33) | 27 (37) | 0.66 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 91 (10) | 70 (10) | 14 (9) | 7 (10) | 0.81 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 233 (26) | 187 (28) | 26 (16) | 20 (27) | 0.010 |

| Previous TIA/stroke, n (%) | 151 (17) | 117 (17) | 23 (14) | 11 (15) | 0.61 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 232 (25) | 170 (25) | 46 (28) | 16 (22) | 0.53 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 157 (17) | 106 (16) | 35 (22) | 16 (22) | 0.10 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 133 (15) | 106 (16) | 18 (11) | 9 (12) | 0.29 |

| Previous hemorrhage, n (%) | 36 (4) | 24 (4) | 9 (6) | 3 (4) | 0.50 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 185 (20) | 139 (21) | 23 (14) | 23 (32) | 0.009 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 50 ± 14 | 49 ± 14 | 52 ± 14 | 48 ± 14 | 0.052 |

| Pattern of atrial fibrillation | |||||

| Permanent, n (%) | 448 (49) | 375 (55) | 35 (22) | 38 (52) | <0.001 |

| Persistent, n (%) | 107 (12) | 78 (12) | 18 (11) | 11 (15) | 0.64 |

| Paroxysmal, n (%) | 352 (39) | 219 (32) | 109 (67) | 24 (33) | <0.001 |

| CHADS2 score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.22 |

| ≥2, n (%) | 647 (71) | 485 (71) | 106 (65) | 56 (77) | 0.16 |

| HAS‐BLED scorea (mean ± SD) | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.64 |

| Indication for PCI | |||||

| Acute STEMI, n (%) | 119 (13) | 89 (13) | 23 (14) | 7 (10) | 0.62 |

| NSTEMI, n (%) | 234 (26) | 174 (26) | 45 (28) | 15 (21) | 0.50 |

| Unstable angina, n (%) | 164 (18) | 106 (16) | 39 (24) | 19 (26) | 0.007 |

| Stable CAD, n (%) | 396 (43) | 310 (46) | 55 (34) | 31 (43) | 0.026 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; NSTEMI, non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TT, triple therapy; VKA, vitamin K‐antagonist; VKA/C, vitamin K antagonists plus clopidogrel.

Maximum score 7, as labile International Normalized Ratio and abnormal liver function were not collected in the original database.

The prescribed duration of antithrombotic therapies and intensity of oral anticoagulation are reported in Table 2. In the TT group, VKA was prescribed lifelong in nearly all patients, whereas this was the case for aspirin in about 60% of patients and for clopidogrel in a very small minority. Clopidogrel was prescribed for 1 month in nearly one‐half of patients and was generally limited to 3 to 6 months in the remaining. In patients discharged on DAPT, aspirin was generally prescribed lifelong and clopidogrel for 12 months. In patients discharged on VKA/C, VKA was prescribed lifelong in nearly all patients and clopidogrel for either 1 or 12 months. In more than half of the cases, however, clopidogrel prescription was limited to 3 to 6 months. The intensity of oral anticoagulation, as expressed by the International Normalized Ratio, was targeted to the conventional level of 2.0 to 3.0 in all cases, both in the TT and VKA/C groups.

Table 2.

Prescribed Duration and Intensity of Antithrombotic Treatments at Discharge

| TT, n = 679 | DAPT, n = 162 | VKA/C, n = 73 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescribed aspirin duration, n (%) | — | ||

| Lifelong | 434 (64) | 139 (86) | |

| 12 months | 82 (12) | 8 (5) | |

| 6 months | 12 (2) | 0 | |

| 3 months | 24 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| 1 months | 104 (15) | 6 (4) | |

| Prescribed clopidogrel duration, n (%) | |||

| Lifelong | 11 (2) | 13 (8) | 4 (6) |

| 12 months | 138 (20) | 86 (53) | 25 (34) |

| 6 months | 66 (10) | 5 (3) | 3 (4) |

| 3 months | 137 (20) | 9 (6) | 12 (16) |

| 1 month | 295 (44) | 37 (23) | 27 (37) |

| Prescribed VKA duration , n (%) | — | ||

| Lifelong | 546 (98) | — | 50 (98) |

| 12 months | 1 (0.2) | — | 0 |

| 6 months | 1 (0.2) | — | 0 |

| 3 months | 1 (0.2) | — | 0 |

| 1 month | 0 | — | 1 (2) |

| Target INR 1.8‐2.5, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | — | 1 (2) |

| Target INR 2.0‐3.0, n (%) | 442 (100) | — | 49 (98) |

| Target INR 3.0‐4.5, n (%) | 0 | — | 0 |

Abbreviations: DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; INR, International Normalized Ratio; TT, triple therapy; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VKA/C, vitamin K antagonist plus clopidogrel.

The adverse events at 1‐year follow‐up are reported in Table 3. No differences in the efficacy and safety end points or total adverse events were observed among groups. Of the major bleeding events occurring after discharge, 16 (49%) in the TT group occurred with this treatment still ongoing, whereas the remaining occurred after TT had been stopped and the following regimens were ongoing: VKA plus aspirin in 10 cases (30%), VKA only in 3 cases (9%), DAPT in 3 cases (9%), and aspirin alone in 1 case (3%). In contrast, all 7 (100%) postdischarge major bleeding events in the DAPT group occurred with such treatment ongoing. In patients discharged on VKA/C, 2 (50%) major bleeding events occurred with such treatment ongoing, and 2 (50%) after clopidogrel had been stopped and VKA only was ongoing.

Table 3.

Adverse Events at 1‐Year Follow‐up

| TT, n = 679 | DAPT, n = 162 | VKA/C, n = 73 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total MACCE, n (%) | 147 (22) | 33 (20) | 13 (18) | 0.72 |

| Stroke/TIA | 14 (2) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.20 |

| Peripheral embolism | 6 (1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0.69 |

| Myocardial infarction | 43 (6) | 4 (3) | 4 (6) | 0.16 |

| Revascularization | 54 (8) | 10 (6) | 7 (10) | 0.62 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosis | 9 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.60 |

| All cause mortality, n (%) | 75 (11) | 18 (11) | 5 (7) | 0.54 |

| Total bleedings, n (%) | 119 (18) | 33 (20) | 12 (16) | 0.66 |

| Minor (BARC 2) | 51 (8) | 13 (8) | 7 (10) | 0.81 |

| Major, n (%) | 69 (10) | 20 (12) | 5 (7) | 0.43 |

| BARC 3a | 31 (5) | 6 (4) | 4 (6) | 0.82 |

| BARC 3b | 20 (3) | 12 (8) | 0 | 0.005 |

| BARC 3c | 7 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.95 |

| BARC 5 | 10 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Total events (MACCE + bleeding), n (%) | 219 (40) | 56 (40) | 21 (34) | 0.67 |

Abbreviations: BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; MACCE, major adverse cardiac/cerebrovascular events; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TT, triple therapy; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VKA/C, vitamin K antagonist plus clopidogrel.

Propensity Score‐Adjusted Analysis

At multinomial logistic regression analysis, pattern (paroxysmal vs permanent/persistent) of AF (P < 0.0001), previous thromboembolism (P = 0.03), number of treated vessels (P = 0.001), and acute coronary syndrome as the indication for PCI‐S (P = 0.008) were significantly different in the 3 treatment groups. This was not the case for stent type (bare metal vs drug eluting), previous PCI‐S, and presence of mechanical heart valve, which therefore were not included in the final regression model. In Table 4, the intermediate outcome of patients in the 3 treatment groups, both estimated by actuarial analysis and adjusted for type of stent, CHADS2 score, and propensity score, is reported.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Estimates of Patients' Outcome According to Drug Regimen

| Outcome End Point | P | TT, n (%) | DAPT, n (%) | VKA/C, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| 1 month | 656 (96.6) | 155 (95.7) | 72 (100) | |

| 6 month | 621 (91.5) | 148 (92.0) | 70 (95.9) | |

| 12 month | 604 (89.0) | 144 (88.9) | 68 (93.2) | |

| Log rank | 0.527 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.516 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.575 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.561 | |||

| Freedom from myocardial infarction | ||||

| 1 month | 650 (99.1) | 150 (96.8) | 72 (98.6) | |

| 6 month | 600 (96.3) | 141 (94.2) | 67 (95.8) | |

| 12 month | 560 (92.2) | 137 (93.5) | 65 (94.4) | |

| Log rank | 0.170 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.223 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.168 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.247 | |||

| Freedom from repeat revascularization | ||||

| 1 month | 653 (99.4) | 155 (96.9) | 71 (97.3) | |

| 6 month | 625 (98.7) | 149 (96.3) | 66 (93.1) | |

| 12 month | 585 (94.2) | 145 (95.0) | 63 (90.2) | |

| Log rank | 0.691 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.755 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.660 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.218 | |||

| Freedom from stent thrombosis | ||||

| 1 month | 653 (99.4) | 154 (99.4) | 72 (100) | |

| 6 month | 616 (99.1) | 146 (98.1) | 68 (97.2) | |

| 12 month | 598 (98.6) | 141 (98.1) | 66 (97.2) | |

| Log rank | 0.618 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.598 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.609 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.971 | |||

| Freedom from stroke/TIA | ||||

| 1 month | 655 (99.7) | 153 (98.1) | 72 (100) | |

| 6 month | 619 (99.2) | 146 (96.8) | 70 (100) | |

| 12 month | 596 (97.9) | 140 (95.5) | 67 (98.5) | |

| Log rank | 0.192 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.156 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.176 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.442 | |||

| Freedom from BARC >1 bleedings | ||||

| 1 month | 590 (93.7) | 131 (92.8) | 66 (95.8) | |

| 6 month | 542 (90.8) | 117 (87.7) | 60 (95.8) | |

| 12 month | 515 (89.4) | 112 (86.2) | 56 (92.5) | |

| Log rank | 0.563 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.332 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.447 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.342 | |||

| Freedom from MACCE | ||||

| 1 month | 642 (93.9) | 147 (90.7) | 69 (94.5) | |

| 6 month | 587 (86.6) | 135 (83.3) | 63 (86.3) | |

| 12 month | 538 (79.4) | 129 (79.6) | 60 (82.2) | |

| Log rank | 0.775 | |||

| CHADS2 adjusted | 0.753 | |||

| DES adjusted | 0.847 | |||

| Propensity score adjusted | 0.745 |

Abbreviations: BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DES, drug‐eluting stent; MACCE, major adverse cardiac/cerebrovascular events; TT, triple therapy; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VKA/C, vitamin K antagonist plus clopidogrel.

Data are reported as number of patients at risk entering the study intervals (percentage).

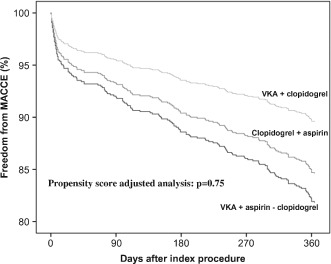

In the Figure, the cumulative Kaplan‐Meier estimates of freedom from MACCE in the 3 treatment groups, after adjustment for propensity score, are presented. As compared to the reference TT, the 12‐month estimated relative risk (and 95% confidence intervals) of MACCE with DAPT and VKA/C were 0.85 (0.40‐1.76) and 0.68 (0.24‐1.88), respectively.

Discussion

In the real‐world population of AF patients undergoing PCI‐S who were included in the prospective, multicenter AFCAS registry, TT was the antithrombotic regimen most frequently prescribed at discharge. As most patients were at moderate–high risk of stroke (ie, CHADS2 score ≥2), this result could be anticipated. Indeed, the percentage of patients discharged on TT (74%) almost perfectly matched that of patients with CHADS2 score ≥2 (71%). Nonetheless, some deviation from current recommendations can be appreciated, as a large proportion of patients receiving DAPT were at moderate–high risk of stroke. This is in the absence of significant differences in the risk of bleeding between groups, as shown by comparable HAS‐BLED scores. In agreement with current recommendations, the duration of clopidogrel treatment in the TT group has been generally kept short (ie, 1 to 3–6 months), likely aiming to reduce the risk of bleeding.

In contrast with most of the previous literature consistently showing that TT is associated with less MACCE but more bleeding compared to other antithrombotic regimens,14, 15 we observed comparable efficacy and safety of TT, DAPT, and VKA/C. Whereas this discrepancy may be accounted for by the heterogeneity in design, indications for VKA and PCI‐S, combinations and doses of antithrombotic agents, and follow‐up durations of previous studies,14, 15 it is of note that our findings are in accordance with more recent data derived from large, Danish, nationwide registries, where a comparable overall efficacy of TT, DAPT, and VKA/C on the occurrence of MACCE in AF patients undergoing PCI‐S has been reported.7 The lowest prevalence of patients with a CHADS2 score ≥2 (in whom oral anticoagulation is warranted) in the DAPT group compared to the other 2 groups including VKA (ie, TT and VKA/C) should also be taken into account when considering the comparable incidence of stroke observed in our population. Such consideration can also be advocated for the similar results of a recent study where 622 AF patients undergoing PCI‐S, in all cases with drug‐eluting stents, were enrolled and treated with either TT, DAPT, or the combination of VKA plus single antiplatelet agent (either aspirin or clopidogrel).16 It must not be overlooked, however, that the relatively small size of our DAPT group may have also played a role in the comparable stroke rate. The incidence of definite/probable ST was also comparable in the 3 treatment groups. Although this could be anticipated for the 2 regimens (ie, TT and DAPT) including DAPT (which is the current therapeutic standard after PCI‐S), the comparable incidence with VKA/C is of note. Again, the lack of differences could be due to the size of the population, and especially of the VKA/C group, which was largely undersized to detect differences in a rare event such as ST. Alternatively, it may be hypothesized that an antiplatelet agent more potent than aspirin, such as clopidogrel, might be sufficient when combined with VKA to prevent ST. Indeed, a comparable incidence of ST with TT and VKA/C has also been observed in the recent WOEST study.8 Owing to the small sample size, together with the open‐label design, the findings relative to the incidence of ST in the WOEST study8 cannot, however, be considered conclusive. For the same reasons, the result of a superior efficacy of VKA/C over TT on the occurrence of MACCE cannot be considered conclusive either.8 Nonetheless, in our study also, the freedom from MACCE, as shown by the propensity score‐adjusted Kaplan‐Meier curves (Figure), albeit not reaching statistical significance, appears greater with VKA/C in comparison to both TT and DAPT.

In our population, the incidence of bleeding was not different in the 3 treatment groups. Whereas an increase in bleeding with TT compared to VKA/C has generally been reported,14, 15 the relative risk of such an increase has been estimated to be only 0.97 to 1.34.14 More recent data derived from large, Danish, nationwide registries further confirm that TT is associated with a nonsignificantly greater risk of bleeding compared to VKA/C,7 thereby supporting our findings of the comparable safety of the 2 regimens. The contrasting observation of a large and significant reduction in the incidence of bleeding with VKA/C compared to TT reported in the recent WOEST study8 may again be related to methodological features. Among them, the open‐label design may have lead to an over‐reporting of bleeding events, which were 3‐ to 4‐fold higher than the average incidences reported in the literature,4, 5, 6, 7, 14, 15 and in our study, and also much higher than the incidence anticipated at the time of sample size calculation.8 In contrast with most of the literature reporting a consistent increase in bleeding with TT compared to DAPT,4, 5, 6, 7, 14, 15 no differences were seen in our population. The relatively small size, especially of the DAPT group, should be considered when trying to explain this discrepancy with previous studies.4, 5, 6, 7, 14, 15

Figure 1.

Freedom from major adverse cardiac/cerebrovascular events (MACCE) after percutaneous coronary intervention with stent in patients with atrial fibrillation according to different drug treatment strategies. Estimated rates are adjusted for propensity score. Abbreviations: VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

In regard to the severity of bleeding, it is of note that major bleeds, defined as combined BARC 3a, 3b, 3c, and 5,12 were also comparable in the 3 groups of our population. Previous reports have shown that TT is associated with a 2‐ and 3‐fold higher incidence of major bleeding events compared to antithrombotic regimens not including VKA and DAPT, respectively.17, 18 Whereas the heterogeneity in design, indications for VKA and PCI‐S, combinations and doses of antithrombotic agents, and follow‐up durations may again have played a role in this discrepancy,14 it also needs to be acknowledged that only in our study was the antithrombotic treatment actually ongoing at the time of the bleeding event evaluated. Only one‐half of the major bleeding events observed after discharge in patients who had been prescribed TT and VKA/C occurred with these regimens ongoing. When considering that, on the contrary, all major bleeds with DAPT occurred with such treatment ongoing, proper attribution of the bleeding event to (and therefore proper estimation of the true safety profile of) the corresponding antithrombotic regimen may have not been accurate in previous reports. Comparison of bleeding rates among studies, however, is difficult, owing to the different bleeding definitions that have been used. In the attempt to more objectively identify and count the bleeding events, thereby potentially forming the base for future comparisons, we applied the more standardized BARC classification.12

Our study is limited by all of the inherent limitations of observational studies, including individual decision making in treatment choices. The absolute low rate of adverse events (both overall and in the individual groups) and the relative small size of some treatment groups, particularly the group receiving VKA/C, need also to be acknowledged, as they may have precluded the possibility of finding differences among the 3 antithrombotic regimens.

Conclusion

In our large, prospective, real‐world population of AF patients undergoing PCI‐S, TT was the most frequently prescribed antithrombotic regimen. The 1‐year efficacy and safety of TT, DAPT, and VKA/C were comparable (even after adjustment for propensity score). Owing to the acknowledged study limitations, however, we believe that our results should not invalidate the current recommendations of prescribing TT to AF patients at moderate–high risk of stroke. Larger, prospective, randomized trials are warranted to further characterize the efficacy and safety of the various combinations of oral anticoagulants (including newer, non‐VKA dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban) and antiplatelets (including newer P2Y12‐receptor inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor) in AF patients undergoing PCI‐S.

Supporting information

Table S1. XXX

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study coordinator, Tuija Vasankari, RN, for her input in data management.

AFCAS trial investigators: T. Kiviniemi, H. Lahtela, P. Porela, K .E .J. Airaksinen, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland; M. Niemelä, T. Kervinen, F. Biancari, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland; P. P. Karjalainen, J. Mikkelsson, A. Ylitalo, Satakunta Central Hospital, Pori, Finland; M. Puurunen, M. Laine, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; S. Vikman, A.‐P. Annala, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland; P. Tuomainen, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland; K. Nyman, Keski‐Suomi Central Hospital, Jyväskylä, Finland; J. Sia, Keski‐Pohjanmaa Central Hospital, Kokkola, Finland; A. Schlitt, Martin Luther‐University Halle‐Wittenberg, and Department of Cardiology, Paracelsus Harz‐Clinic, Bad Suderode, Germany; P. Kirchhof, Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany; M. Weber, J. Ehret, Kerckhoff Heart Center, Bad Nauheim, Germany; H. Thiele, M. Woinke, Heart Center Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany; J. Kreuzer, St. Vincenz Krankenhaus, Limburg, Germany; A. Rubboli, Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy; L. La Vecchia, Ospedale S. Bortolo, Vicenza, Italy; A. Capecchi, Ospedale Civile, Bentivoglio, Italy; G. Y .H. Lip, University Department of Medicine, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom; J. Valencia, General Hospital University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain.

This study was supported by unrestricted grants from Novartis Germany and Sanofi‐Aventis Germany, and by grants from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Helsinki, Finland.

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Lip GY, Huber K, Andreotti F, et al; European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis . Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention/stenting. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Faxon DP, Eikelboom JW, Berger PB, et al. Consensus document: antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary stenting. A North American perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:572–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sørensen R, Hansen ML, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Risk of bleeding in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with different combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, vitamin K antagonists in Denmark: a retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data. Lancet. 2009;374:1967–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hansen M, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2010;170:1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lamberts M, Olesen JB, Ruwald MH, et al. Bleeding after initiation of multiple antithrombotic drugs, including triple therapy, in atrial fibrillation patients following myocardial infarction and coronary intervention. A nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2012;126:1185–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lamberts M, Gislason GH, Olesen JB, et al. Oral anticoagulation and antiplatelets in atrial fibrillation patients after myocardial infarction and coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt F, et al; WOEST study investigators . Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open‐label, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rubboli A, Halperin JL. Pro: Antithrombotic therapy with warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel is the recommended regime in anticoagulated patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome and/or undergo percutaneous coronary interventions. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:752–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schlitt A, Rubboli A, Lip GY, et al. The management of patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: in‐hospital data from the atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary artery stenting study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:E864–E870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reed GW, Cannon CP. Triple oral antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation and coronary artery stenting. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moser M, Olivier CB, Bode C. Triple antithrombotic therapy in cardiac patients: more questions than answers [published online ahead of print December 2, 2013]. Eur Heart J. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao F, Zhou YJ, Wang ZJ, et al. Comparison of different antithrombotic regimens for patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing drug‐eluting stent implantation. Circ J. 2010;74:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao HJ, Zheng ZT, Wang ZH, et al. “Triple therapy” rather than “triple threat”: a meta‐analysis of the two antithrombotic regimens after stent implantation in patients receiving long‐term oral anticoagulant treatment. Chest. 2011;139:260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gao F, Zhou YJ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meta‐analysis of the combination of warfarin and dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting in patients with indications for chronic oral anticoagulation. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. XXX