Beliefs about cancer curability and estimated survival can differ between patients with cancer and their oncologists, which can affect treatment decision making. This article addresses discordance in beliefs between older patients and their oncologists, as well as between caregivers and oncologists.

Keywords: Beliefs about cancer curability, Discordance, Older adults, Caregivers, Oncologists

Abstract

Background.

Ensuring older patients with advanced cancer and their oncologists have similar beliefs about curability is important. We investigated discordance in beliefs about curability in patient‐oncologist and caregiver‐oncologist dyads.

Materials and Methods.

We used baseline data from a cluster randomized trial assessing whether geriatric assessment improves communication and quality of life in older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Patients were aged ≥70 years with incurable cancer from community oncology practices. Patients, caregivers, and oncologists were asked: “What do you believe are the chances the cancer will go away and never come back with treatment?” Options were 100%, >50%, 50/50, <50%, and 0% (5‐point scale). Discordance in beliefs about curability was defined as any difference in scale scores (≥3 points were severe). We used multivariate logistic regressions to describe correlates of discordance.

Results.

Discordance was present in 60% (15% severe) of the 336 patient‐oncologist dyads and 52% (16% severe) of the 245 caregiver‐oncologist dyads. Discordance was less common in patient‐oncologist dyads when oncologists practiced longer (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84–0.97) and more common in non‐Hispanic white patients (AOR 5.77, CI 1.90–17.50) and when patients had lung (AOR 1.95, CI 1.29–2.94) or gastrointestinal (AOR 1.55, CI 1.09–2.21) compared with breast cancer. Severe discordance was more common when patients were non‐Hispanic white, had lower income, and had impaired social support. Caregiver‐oncologist discordance was more common when caregivers were non‐Hispanic white (AOR 3.32, CI 1.01–10.94) and reported lower physical health (AOR 0.88, CI 0.78–1.00). Severe discordance was more common when caregivers had lower income and lower anxiety level.

Conclusion.

Discordance in beliefs about curability is common, occasionally severe, and correlated with patient, caregiver, and oncologist characteristics.

Implications for Practice.

Ensuring older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers have similar beliefs about curability as the oncologist is important. This study investigated discordance in beliefs about curability in patient‐oncologist (PO) and caregiver‐oncologist (CO) dyads. It found that discordance was present in 60% (15% severe) of PO dyads and 52% (16% severe) of CO dyads, raising serious questions about the process by which patients consent to treatment. This study supports the need for interventions targeted at the oncologist, patient, caregiver, and societal levels to improve the delivery of prognostic information and patients’/caregivers’ understanding and acceptance of prognosis.

Introduction

Ensuring patients with advanced cancer have similar beliefs as their oncologists about cancer curability is essential for treatment decision‐making, advance care planning, and psychological support. Patients who overestimate the curability of their cancer may be more willing to receive intensive treatment [1] and less likely to use end‐of‐life care [2], [3]. Studies have shown that up to 69% of patient‐oncologist dyads have different beliefs about cancer curability or estimated survival [4], [5]. Although the majority of cancer diagnoses and deaths occur in older adults, few data on beliefs about cancer curability exist in this population. Studies have shown that older adults have lower awareness of their diagnosis and prognosis than their younger counterparts [6], [7], [8]. Furthermore, many older adults are frail and have functional, psychological, and social vulnerabilities that may affect how information is communicated and processed. These age‐related vulnerabilities are associated with higher morbidity and mortality [9], [10] and add complexities to the care of and treatment decisions among older adults with cancer. Older adults are at a higher risk of experiencing adverse events related to cancer treatments [11]; therefore, ensuring older adults have similar beliefs about curability as their oncologists may allow them to receive goal‐concordant care.

In cancer care, discordance in prognostic beliefs is presumed to reflect both patients’ understanding of their illnesses and the quality of communication between oncologists and patients [4], [12], [13]. In an effort to improve cancer care delivery, studies have begun to explore the correlates of discordance in prognostic beliefs, although not specifically focusing on older adults [4]. For instance, one study found that discordance in estimated survival was more common when patients were not white [4], which represents a significant health disparity that should be evaluated in the older population.

Caregivers play a significant role in cancer care, especially in older adults; they frequently accompany patients to medical appointments, assist patients in daily activities such as taking medications, and often participate in treatment decision‐making. Therefore, ensuring caregivers have the same beliefs about cancer curability as the oncologist can help reinforce the cancer prognosis in home conversations [14] and help caregivers anticipate the outcome of terminal illness. Surprisingly, few studies have examined caregiver‐oncologist prognostic discordance [5], [15]. To our knowledge, no studies have examined correlates of caregiver‐oncologist discordance in beliefs about curability.

Prior studies on discordance in beliefs about cancer curability or estimated survival have been conducted in specific cancer types, had relatively small sample sizes, or did not focus on older adults and their caregivers [4], [5], [12], [16], [17]. In addition, to our knowledge, there have been no reports about oncologist characteristics associated with discordance, and few studies have examined the severity of discordance in cancer curability [5]. In this study, beyond estimating the prevalence and the severity of discordance in cancer curability in patient‐oncologist and caregiver‐oncologist dyads, we examined correlates of discordance. We hypothesized that age‐related vulnerabilities and non‐white race would be associated with discordance in beliefs about curability in both dyads.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a cluster randomized trial assessing whether geriatric assessment (GA) improves communication and quality of life in older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers (University of Rochester Cancer Center 13070; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02107443; Principal Investigator: S.G.M.) [18]. The primary study was conducted within the University of Rochester Cancer Center National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Program Research Network and enrolled patients who were aged 70 years and above, had a diagnosis of an incurable stage III/IV solid tumor or lymphoma, had at least one impaired GA domain, and were considering or receiving any kind of cancer treatment. GA assesses age‐related vulnerabilities or domains that are predictive of morbidity and mortality in older adults with cancer [19], [20], [21], [22]. In our study, GA domains were assessed using validated tools and cutoffs and included comorbidity [23], functional status [24], [25], [26], [27], physical performance [28], [29], cognition [30], [31], instrumental social support (e.g., someone to help if you were confined to bed) [32], polypharmacy [33], psychological health [34], [35], and nutrition [36], [37], [38] (supplemental online Table 1).

The patient's oncologist and a caregiver were also enrolled in the study. Caregivers were selected by the patient when asked, “Is there a family member, partner, friend, or caregiver (age 21 or older) with whom you discuss or can be helpful in health‐related matters?” A total of 31 community oncology practices participated in the study between October 2014 and April 2017. All data reported in this secondary analysis were collected at baseline.

Measures

Following informed consent, patients provided demographic data and completed the self‐reported portion of the GA. Clinical research associates performed the objective assessment portion of the GA. Patients then completed assessments of their beliefs about the curability of the cancer: “What do you believe are the chances the cancer will go away and never come back with treatment?” Response options were 100%, >50%, 50/50, <50%, 0%, or uncertain. We adapted this question from a prior study [39]. We modified this question to decrease the number of response options and to include the option for “uncertain.” Missing or “uncertain” responses were excluded from this analysis because the severity of discordance is best examined with numerical data. Belief about curability was thus assessed on a 5‐point ordinal scale, ranging from 0% (1 point) to 100% (5 points).

Similarly, caregivers provided demographic data, self‐reported their health status, and completed assessments of their beliefs about the curability of the cancer. Oncologists provided demographic data and completed assessments of their beliefs about the curability of the cancer.

Dependent Variable for Patients: Patient‐Oncologist Discordance in Beliefs About Curability.

Prognostic discordance was defined as the presence of any patient‐oncologist difference on the 5‐point ordinal scale. If the difference score was ≥3 points, the prognostic discordance was categorized as severe. For example, if a patient answered >50% (4 points) and his/her oncologist answered 0% (1 point), then prognostic discordance was present (3 points). Definitions of discordance were based on consensus of the study team.

Dependent Variable for Caregivers: Caregiver‐Oncologist Discordance in Beliefs About Curability.

Prognostic discordance was defined as the presence of any caregiver‐oncologist difference on the 5‐point ordinal scale. If the difference score was ≥3 points, the prognostic discordance was categorized as severe.

Key Independent Variables for Patients: Age‐Related Vulnerabilities and Race.

Age‐related vulnerabilities in patients were assessed using the GA as described above. Race was categorized as white (non‐Hispanic white) and other.

Key Independent Variables for Caregivers: Age‐Related Vulnerabilities and Race.

Caregiver health was assessed using validated instruments including the Older Americans Resources and Services Comorbidity [23], 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐12) [40], distress thermometer [41], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐2) [42], and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD‐7) [35]. The SF‐12 assesses functional health status and includes physical and mental health, each scored from 0 to 100 with a lower score indicating more impairment [40]. The distress thermometer consists of an 11‐point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress) [41]. The PHQ‐2 consists of two questions: (a) Little interest or pleasure in doing things, and (b) Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. Each question is scored on a 0–3 scale, 0 indicating not at all and 3 indicating nearly every day, and a total score is generated [42]. The GAD‐7 consists of seven questions, all scored on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) scale (possible range 0–21) [35]. Race was categorized as white (non‐Hispanic white) and other.

Covariates for Regressions Evaluating Correlates of Patient‐Oncologist Discordance.

Covariates included patient demographic (age, gender, education, marital status, and annual household income), clinical (cancer types) and communication variables (communication self‐efficacy and patient recall of prognostic discussions) [12], [13], and oncologist variables (age, gender, race, and number of years in practice since completion of oncology fellowship). Communication self‐efficacy was assessed using the 5‐item Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions (PEPPI) scale; higher scores indicate greater self‐efficacy [43]. For recalled prognostic discussion, patients were asked, “To what extent have you discussed your prognosis with your cancer doctor?” and were provided with the following options: completely, mostly, a little, or not at all [4]. These options were collapsed into two levels (completely and mostly vs. a little and not at all).

Covariates for Regressions Evaluating Correlates of Caregiver‐Oncologist Discordance.

Correlates included caregiver demographic and communication variables as well as oncologist variables as described above. Demographic variables included caregiver age, gender, income, education, and marital status. Communication variables included caregiver recalled prognostic discussion with the oncologist [4] and PEPPI [43].

Statistical Analyses

After describing the population and discordance in beliefs about cancer curability using descriptive analyses, we used bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models to test the hypothesized associations of age‐related vulnerabilities and race with discordance and severe discordance in beliefs about curability in the patient‐oncologist dyads and to identify other correlates of discordance, including patient and oncologist variables. The same analysis was repeated in the caregiver‐oncologist dyads using caregiver and oncologist variables. All variables with a p value of <.20 in bivariate analyses were entered into multivariate models [44]. Backward stepwise regressions were performed with the final models including only significant variables (p < .05). We used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering at the practice level. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS software package (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 541 patient‐oncologist dyads enrolled in the primary study [18], 20 were excluded because the patients (n = 17) and/or oncologists (n = 8) provided no response. An additional 185 patient‐oncologist dyads were excluded because the patients (n = 175) and/or oncologists (n = 15) were uncertain of the prognosis (supplemental online Fig. 1). Of the 414 caregiver‐oncologist dyads enrolled, 3 dyads were excluded because caregiver demographics were completely missing, and 23 dyads were excluded because the caregivers (n = 19) and/or oncologists (n = 4) provided no response. An additional 146 caregiver‐oncologist dyads were excluded because the caregivers (n = 140) and/or oncologists (n = 12) were uncertain of the prognosis. Therefore, our final analytic sample consisted of 336 patient‐oncologist dyads (113 oncologists from 27 practices) and 245 caregiver‐oncologist dyads (104 oncologists from 26 practices; supplemental online Fig. 1).

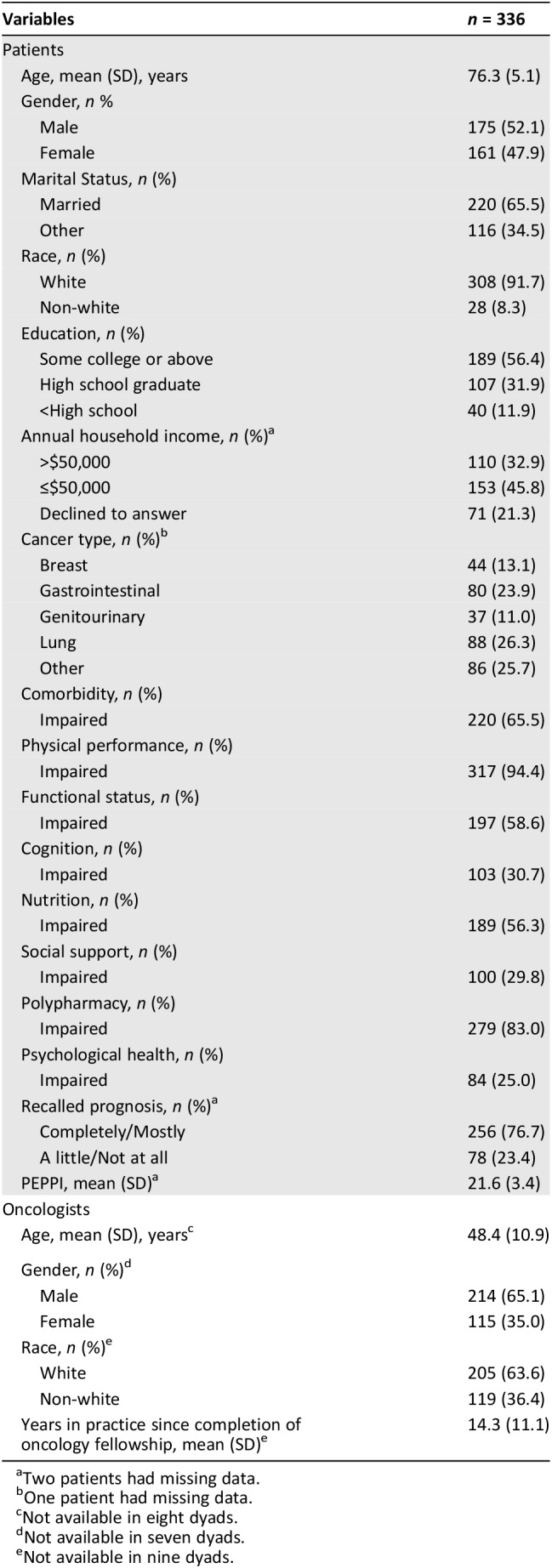

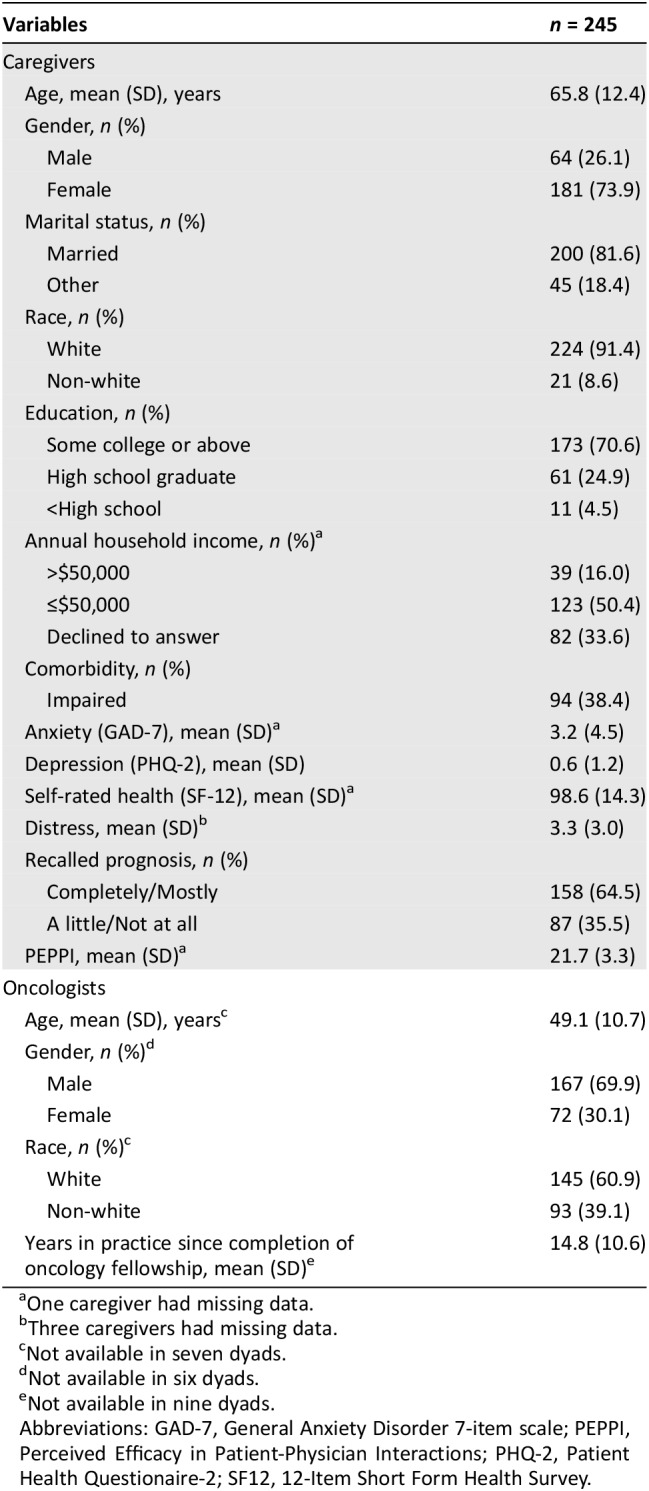

The mean (SD, range) age of the patient and caregiver samples was 76.3 (5.1, 70–93) years and 65.8 (12.4, 26–89) years, respectively. Tables 1 and 2 show baseline demographic and clinical information for the patients and caregivers, respectively, as well as the characteristics of the oncologists. Among the patient‐oncologist dyads, 60.2% (197/327) were race‐concordant. Among the caregiver‐oncologist dyads, 57.9% (138/238) were race‐concordant.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients and oncologists in the patient‐oncologist dyads.

Two patients had missing data.

One patient had missing data.

Not available in eight dyads.

Not available in seven dyads.

Not available in nine dyads.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the caregivers and oncologists in the caregiver‐oncologist dyads.

One caregiver had missing data.

Three caregivers had missing data.

Not available in seven dyads.

Not available in six dyads.

Not available in nine dyads.

Abbreviations: GAD‐7, General Anxiety Disorder 7‐item scale; PEPPI, Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions; PHQ‐2, Patient Health Questionaire‐2; SF12, 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey.

Prevalence and Extent of Discordance in Beliefs About Curability

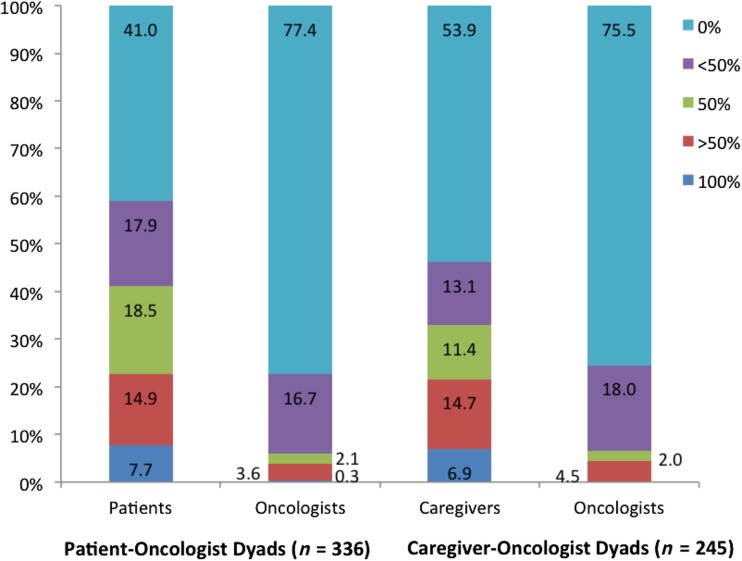

Figure 1 shows the distribution of beliefs about curability. Discordance was present in more than half of the patient‐oncologist (202/336; 60.1%) and caregiver‐oncologist (128/245; 52.2%) dyads, with patients (179/202; 88.6%) and caregivers (100/128; 78.1%) reporting a greater likelihood of cure than oncologists (p < .01 for both; Table 3). Severe discordance was present in 15.1% (51/336) of patient‐oncologist and 16.3% (40/245) of caregiver‐oncologist dyads. In dyads in which patients and caregivers reported a greater likelihood of cure than oncologists, severe prognostic discordance was present in 27.8% (50/180) and 37.0% (37/100), respectively. In dyads in which oncologists reported a greater likelihood of cure, severe prognostic discordance was present in 4.3% (1/23) and 10.7% (3/28), respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of beliefs about curability (patients, caregivers, and oncologists were asked the following question: “What do you believe are the chances the cancer will go away and never come back with treatment?”).

Table 3. Prevalence and extent of prognostic discordance between patients and oncologists, and between caregivers and oncologists.

Beliefs about curability in patients, caregivers, and oncologists were assessed on a 5‐point ordinal scale, including 100% (1), >50% (2), 50/50 (3), <50% (4), 0% (5). Patient‐oncologist and caregiver‐oncologist prognostic discordance were defined as the presence of any difference on the 5‐point ordinal scale.

In 26 (78.8%) of the 33 patient‐oncologist dyads in this column, patients selected >50% and oncologists selected 0%.

In 23 (88.5%) of the 26 caregiver‐oncologist dyads in this column, caregivers selected >50% and oncologists selected 0%.

Rates of patient‐oncologist discordance were no different when patients enrolled with a caregiver compared with those who enrolled without a caregiver (61.9% vs. 54.4%, p = .24). Corresponding rates for severe prognostic discordance were 14.8% and 16.5% (p = .72), respectively. Caregiver‐oncologist discordance was more common in the setting of patient‐oncologist discordance (76.1% vs. 18.9%, p < 0.01).

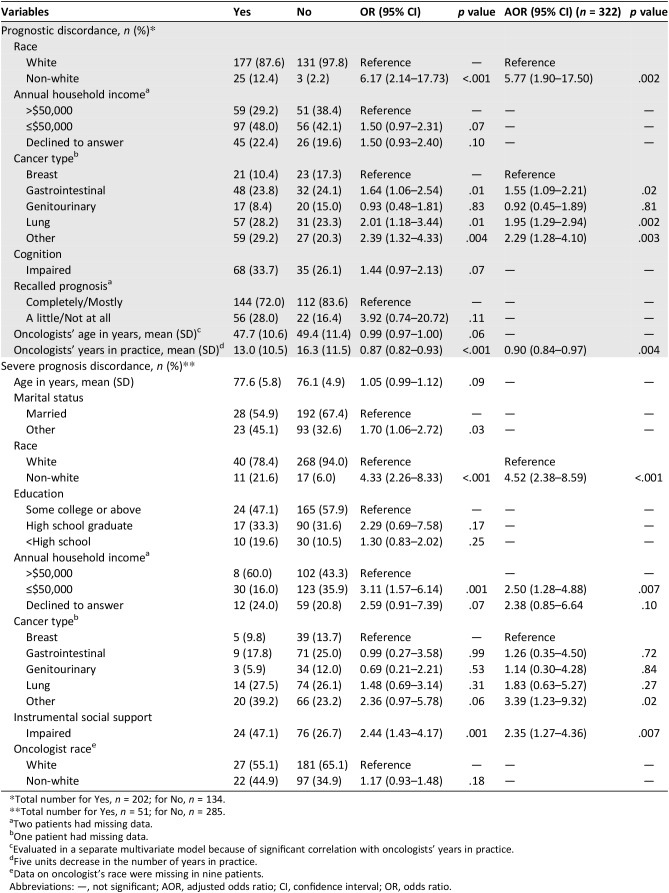

Correlates of Patient‐Oncologist Discordance

On multivariate analysis, discordance in beliefs about curability was more common when patients had lung (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.95, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29–2.94) or gastrointestinal (AOR 1.55, 95% CI 1.09–2.21) cancers than breast cancer and when patients were non‐white (AOR 5.77, 95% CI 1.90–17.50; Table 4). Discordance in beliefs about curability was somewhat less common in dyads that included oncologists who had been in practice longer (5 units increase in the number of years in practice, AOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.97).

Table 4. Bivariate and multivariate analyses evaluating correlates of patient‐oncologist discordance.

Total number for Yes, n = 202; for No, n = 134.

Total number for Yes, n = 51; for No, n = 285.

Two patients had missing data.

One patient had missing data.

Evaluated in a separate multivariate model because of significant correlation with oncologists’ years in practice.

Five units decrease in the number of years in practice.

Data on oncologist's race were missing in nine patients.

Abbreviations: —, not significant; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Severe discordance was more common in non‐white patients (AOR 4.52, 95% CI 2.38–8.59), patients with lower annual household income (≤$50,000 vs. >$50,000; AOR 2.50, 95% CI 1.28–4.88), and patients with impaired instrumental social support (AOR 2.35, 95% CI 1.27–4.36; Table 4).

Correlates of Caregiver‐Oncologist Discordance

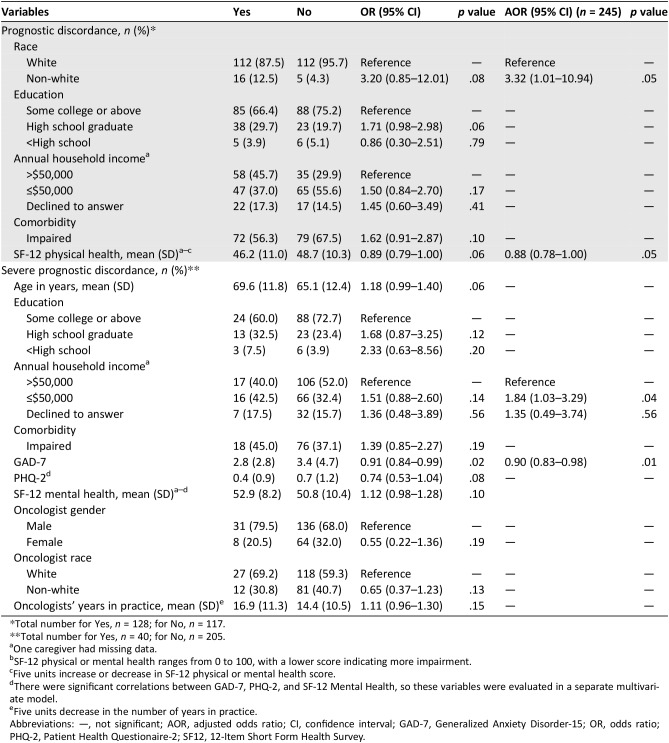

On multivariate analysis, discordance in beliefs about curability was more common in non‐white caregivers (AOR 3.32, 95% CI 1.01–10.94) and in those with worse self‐reported health (5 units decrease in SF‐12 physical health, AOR 0.88, 95% CI 0.78–1.00; Table 5).

Table 5. Bivariate and multivariate analyses evaluating correlates of caregiver‐oncologist discordance.

Total number for Yes, n = 128; for No, n = 117.

Total number for Yes, n = 40; for No, n = 205.

One caregiver had missing data.

SF‐12 physical or mental health ranges from 0 to 100, with a lower score indicating more impairment.

Five units increase or decrease in SF‐12 physical or mental health score.

There were significant correlations between GAD‐7, PHQ‐2, and SF‐12 Mental Health, so these variables were evaluated in a separate multivariate model.

Five units decrease in the number of years in practice.

Abbreviations: —, not significant; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GAD‐7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder‐15; OR, odds ratio; PHQ‐2, Patient Health Questionaire‐2; SF12, 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey.

Severe discordance in beliefs about curability was more common in caregivers with lower annual household income (AOR 1.84, 95% CI 1.03–3.29) and lower anxiety levels (1 unit decrease in GAD‐7, AOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.83–0.98).

Discussion

In this study of community oncologists and their older patients and their caregivers, discordance in beliefs about curability was present in 60.1% of patient‐oncologist dyads and 52.2% of caregiver‐oncologist dyads and was most often (but not always) attributable to patients and caregivers reporting a greater likelihood of cure than oncologists. More than 15% of discordance was designated as severe.

Discordance in beliefs about curability reflects both a patient's understanding of their illness and the quality of communication between oncologist and patient. A prior study suggested that a majority of discordance in estimated survival was attributable to patients misunderstanding their oncologists’ opinions [4], perhaps due to the strategies employed by oncologists in communicating prognosis. For example, one study showed that oncologists’ use of pessimistic statements was more likely to lead to concordance [12]. Discordance may also occur as a result of avoidance of prognostic discussions by patients and physicians [45], [46], physicians’ discomfort in discussing prognosis [47], or physicians’ lack of confidence in responding to patients’ emotions [48]. Oncologists rarely offer prognostic information unless asked by patients [49], which can be a barrier for older adults who may be less likely to ask questions [50]. In addition, discordance may stem from fixed patient/caregiver beliefs or inaccurate interpretations of prognostic information [51].

We found that severe discordance in beliefs about cancer curability was more common in older patients with impaired instrumental social support. This may reflect the lack of a support system, which is common among older adults, that affords an opportunity for older patients to discuss their prognosis [52]. It may also represent inadequate discussion of prognosis by oncologists with older patients who lack instrumental social support due to oncologists’ concerns that older patients may not be able to cope with the information. It is interesting that cognition was not associated with discordance, because cognitive impairment may affect the ability of older patients to understand their disease and prognosis. Our study only recruited patients who were considering or receiving active treatments, and it is possible that older patients with severe cognitive impairment were screened out from the study. Discordance was more common in caregivers with poorer self‐reported physical health, although the reason for this is unclear. A prior study has shown that patients with better performance status were more likely to have inaccurate beliefs about cancer curability [53]. The relationship between caregiver health and discordance should therefore be further investigated. This is important because many caregivers of older adults have poor physical health and comorbidities [54].

Prior studies have demonstrated that acceptance of prognosis is associated with greater anxiety symptoms in patients, but this association is less well studied in caregivers [55], [56]. We showed that caregiver anxiety was lower in dyads characterized by severe discordance in beliefs about curability, which, like in patients [55], may reflect a lack of acceptance of prognosis or the use of coping mechanisms to ward off anxiety. However, this area requires further investigation. Although discussion of prognosis may raise anxiety in some caregivers and patients, it might strengthen the patient‐physician relationship [57]. Oncologists who convey accurate prognostic information might also expose patients to fewer unnecessary and aggressive treatments that can cause more harm than benefits over the longer term. Palliative care interventions could help support oncologists’ efforts to convey prognosis [55].

Consistent with prior research [4] and our hypothesis, discordance was more prevalent among dyads with non‐white patients and non‐white caregivers. Oncologist race was not associated with discordance in beliefs about curability. Higher discordance in patients and caregivers of non‐white race may be partially due to cultural barriers [58], [59] associated with the delivery of prognostic information [60]. In addition, disease perceptions vary based on racial and cultural background [61], [62], [63], which may affect how prognostic information is processed, encoded, recalled, and accepted.

Compared with patient‐oncologist dyads involving older patients with breast cancer, dyads in which patients had lung cancer or gastrointestinal cancer were more likely to be discordant in their beliefs about curability. This intriguing finding might suggest differences in how oncologists communicate prognosis with older patients who have lung or gastrointestinal cancer compared with breast cancer [64], [65]. Perhaps oncologists are more reluctant to share prognostic information with older patients with lung or gastrointestinal cancer. It is also possible that older patients with advanced gastrointestinal or lung cancer may have a different understanding about the chance of cure compared with those with breast cancer [56], [66], [67]. These differences may be driven by several factors. Prognoses of lung and gastrointestinal cancers are generally worse than those of breast cancer; the worse the news, the more difficult it might be for patients to process and encode [68]. Moreover, given the gravity of the prognoses in lung and gastrointestinal cancers, it might be more difficult for older patients to accept terrifying prognostic information, even if it is understood and encoded [69]. There are also different societal perceptions, with more negative attitudes toward lung versus breast cancer [70]. Along similar lines, societal efforts in promoting cancer awareness have historically focused more on breast cancer [70], [71].

Individuals with fewer years of education and those with lower incomes are more likely to receive chemotherapy and be hospitalized before death and less likely to be referred for palliative care or hospice [72], [73], [74]. Observed socioeconomic disparities in cancer care outcomes remain poorly understood. We showed that severe discordance in beliefs about curability was more common in older patients and caregivers with lower annual household incomes, which is an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES). Lower levels of health literacy and higher levels of fatalism are both common in patients with lower SES [75], both of which may contribute to prognostic discordance [51]. Power asymmetries in the patient/caregiver‐clinician relationship [76], [77] are accentuated in the care of individuals with lower SES. Many studies have shown that individuals with lower SES perceive that their physicians treat and communicate with them differently, and believe that there may be differences in testing, medication, access to care, and quality of care [78], [79], [80]. In the cancer setting, these perceptions might heighten patient/caregiver distrust of physicians and contribute to discordance in beliefs about curability.

Discordance in beliefs about curability was less common in dyads involving oncologists who practiced longer. Experienced oncologists may have a higher propensity [81] or comfort level [82] for discussing prognosis, which can help patients understand their illness. It is also possible that older patients are more likely to believe or trust more experienced oncologists [83].

Taken together, our findings suggest that discordance about beliefs about curability is present in more than 50% of oncologist‐patient and oncologist‐caregiver dyads. In more than 15% of these dyads, the discordance may be severe enough to raise difficult questions about whether patients are sufficiently informed to make treatment decisions. An intervention that focuses on communication was attempted to promote greater agreement about prognosis but was unsuccessful, suggesting that more than communication training is required [4], [39]. Multimodal interventions are needed to improve how oncologists communicate prognosis and to empower older patients and their caregivers to enquire about prognosis, taking into account the racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds of the patients and caregivers as well as their beliefs, emotions, and fears [39]. In addition, the problem of severe discordance may require broader public health and policy initiatives to assess whether patients are adequately informed to provide consent to potentially toxic treatments [84], [85]. Nonetheless, although avoiding discordance would seem to be clinically intuitive, it is important to note that, unlike patient's perceived prognosis and curability, the association of discordance in beliefs about curability with outcomes is not well studied, and future studies are needed to assess its relationship with outcomes.

The strengths of our study include the number of older patients and their caregivers enrolled as well as its enrollment in the community oncology setting. There are several limitations to our study. First, this observational study was not designed to determine how or why discordance in beliefs about curability occurs. Second, our study included a small number of non‐white patients and caregivers. Third, our study is likely underpowered to detect significant associations between oncologist race and discordance in beliefs about curability, and these associations require further investigations. Finally, the psychometric properties of the item used to assess beliefs about curability are unknown.

Conclusion

Discordance in beliefs about curability is common and occurred in more than half of patient‐oncologist and caregiver‐oncologist dyads. In about 15% of these dyads, discordance was severe enough to raise serious questions about the process by which older patients consent to treatment. Our study supports the need for interventions targeted at the oncologist, patient, caregiver, and societal levels to improve the delivery of prognostic information and patients’/caregivers’ understanding and acceptance of prognosis.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Susan Rosenthal for her editorial assistance. This work was funded through a Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634; S.G.M.), UG1 CA189961, R01 CA177592 (S.G.M.), and R01CA168387 (P.D.) from the National Cancer Institute, and K24 AG056589 from the National Institute of Aging (S.G.M.). This work was made possible by the generous donors to the Wilmot Cancer Institute geriatric oncology philanthropy fund. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. This study was presented as a poster presentation at the 2018 International Society of Geriatric Oncology Annual Meeting.

Deceased.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Kah Poh Loh, Supriya Gupta Mohile, Ronald Epstein, William Dale, Arti Hurria, Paul Duberstein

Provision of study material or patients: Alison Conlin, James Bearden III, Adedayo Onitilo

Collection and/or assembly of data: Lianlian Lei, Eva Culakova, Megan Wells, Nikesha Gilmore

Data analysis and interpretation: Kah Poh Loh, Lianlian Lei, Eva Culakova

Manuscript writing: Kah Poh Loh, Colin McHugh, Paul Duberstein

Final approval of manuscript: Kah Poh Loh, Supriya Gupta Mohile, Jennifer L. Lund, Ronald Epstein, Lianlian Lei, Eva Culakova, Colin McHugh, Megan Wells, Nikesha Gilmore, Mostafa R. Mohamed, Charles Kamen, Valerie Aarne, Alison Conlin, James Bearden III, Adedayo Onitilo, Marsha Wittink, William Dale, Arti Hurria, Paul Duberstein

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Hirose T, Yamaoka T, Ohnishi T et al. Patient willingness to undergo chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy for locally advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW, Walling A, Dy S et al. Patient beliefs that chemotherapy may be curative and care received at the end of life among patients with metastatic lung and colorectal cancer. Cancer 2015;121:1891–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yennurajalingam S, Lu Z, Prado B et al. Association between advanced cancer patients' perception of curability and patients' characteristics, decisional control preferences, symptoms, and end‐of‐life quality care outcomes. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1609–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G et al. Determinants of patient‐oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY et al. Patients' and family caregivers' understanding of the cancer stage, treatment goal, and chance of cure: A study with patient‐caregiver‐physician triad. Psychooncology 2018;27:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numico G, Anfossi M, Bertelli G et al. The process of truth disclosure: An assessment of the results of information during the diagnostic phase in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol 2009;20:941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brokalaki EI, Sotiropoulos GC, Tsaras K et al. Awareness of diagnosis, and information‐seeking behavior of hospitalized cancer patients in Greece. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caruso A, Di Francesco B, Pugliese P et al. Information and awareness of diagnosis and progression of cancer in adult and elderly cancer patients. Tumori 2000;86:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosko AE, Huang Y, Benson DM et al. Use of a comprehensive frailty assessment to predict morbidity in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing transplant. J Geriatr Oncol 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 2013;121:4287–4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2366–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson TM, Alexander SC, Hays M et al. Patient‐oncologist communication in advanced cancer: Predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D et al. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: Associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3809–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston G, Abraham C. Managing awareness: Negotiating and coping with a terminal prognosis. Int J Palliat Nurs 2000;6:485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Changes in prognostic awareness among seriously ill older persons and their caregivers. J Palliat Med 2006;9:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El‐Jawahri A, Traeger L, Kuzmuk K et al. Prognostic understanding, quality of life and mood in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:1119–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidet P, Hamel MB, Davis RB et al. Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician‐patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 1998;105:222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A et al. Improving communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment (GA): A University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) cluster randomized controlled trial (CRCT). J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 18):LBA10003a. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishijima TF, Deal AM, Lund JL et al. The incremental value of a geriatric assessment‐derived three‐item scale on estimating overall survival in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2018;9:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos MV et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: An International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood 2015;125:2068–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dottorini L, Catena L, Sarno I et al. The role of Geriatric screening tool (G8) in predicting side effect in older patients during therapy with aromatase inhibitor. J Geriatr Oncol 2019;10:356–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz J, Miller AA, Tooze JA et al. Frailty assessment predicts toxicity during first cycle chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer regardless of chronologic age. J Geriatr Oncol 2019;10:48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn JE, Rudberg MA, Furner SE et al. Mortality, disability, and falls in older persons: The role of underlying disease and disability. Am J Public Health 1992;82:395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitelaw NA, Liang J. The structure of the OARS physical health measures. Med Care 1991;29:332–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self‐maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brorsson B, Asberg KH. Katz index of independence in ADL. Reliability and validity in short‐term care. Scand J Rehabil Med 1984;16:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavasini R, Guralnik J, Brown JC et al. Short Physical Performance Battery and all‐cause mortality: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Med 2016;14:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P et al. Validation of a short Orientation‐Memory‐Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140:734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P et al. The Mini‐Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population‐based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1451–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burholt V, Windle G, Ferring D et al. Reliability and validity of the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) social resources scale in six European countries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:S371–S379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol 2016;7:346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weintraub D, Oehlberg KA, Katz IR et al. Test characteristics of the 15‐item geriatric depression scale and hamilton depression rating scale in Parkinson disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wild B, Eckl A, Herzog W et al. Assessing generalized anxiety disorder in elderly people using the GAD‐7 and GAD‐2 scales: Results of a validation study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:1029–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montejano Lozoya R, Martinez‐Alzamora N, Clemente Marin G et al. Predictive ability of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA‐SF) in a free‐living elderly population: A cross‐sectional study. PeerJ 2017;5:e3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Losonczy KG, Harris TB, Cornoni‐Huntley J et al. Does weight loss from middle age to old age explain the inverse weight mortality relation in old age? Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flodin L, Svensson S, Cederholm T. Body mass index as a predictor of 1 year mortality in geriatric patients. Clin Nutr 2000;19:121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ et al. Effect of a patient‐centered communication intervention on oncologist‐patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: The VOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurria A, Li D, Hansen K et al. Distress in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4346–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ‐2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN et al. Perceived efficacy in patient‐physician interactions (PEPPI): Validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.In Lee K, Koval JJ. Determination of the best significance level in forward stepwise logistic regression. Commun Stat Simul Comput 1997;26:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Attitude and self‐reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:2389–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MH et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end‐of‐life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psychooncology 2015;24:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Granek L, Krzyzanowska MK, Tozer R et al. Oncologists' strategies and barriers to effective communication about the end of life. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:e129–e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scrimin S, Axia G, Tremolada M et al. Conversational strategies with parents of newly diagnosed leukaemic children: An analysis of 4880 conversational turns. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henselmans I, Smets EMA, Han PKJ et al. How long do I have? Observational study on communication about life expectancy with advanced cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1820–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noordman J, Driesenaar JA, Henselmans I et al. Patient participation during oncological encounters: Barriers and need for supportive interventions experienced by elderly cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:2262–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duberstein PR, Chen M, Chapman BP et al. Fatalism and educational disparities in beliefs about the curability of advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta‐analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;75:122–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eidinger RN, Schapira DV. Cancer patients' insight into their treatment, prognosis, and unconventional therapies. Cancer 1984;53:2736–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P et al. Quality of life of caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nipp RD, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Coping and prognostic awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2551–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El‐Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER et al. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2014;120:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fenton JJ, Duberstein PR, Kravitz RL et al. Impact of prognostic discussions on the patient‐physician relationship: Prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harris JJ, Shao J, Sugarman J. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis and prognosis in Northern Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang X, Butow P, Meiser B et al. Attitudes and information needs of Chinese migrant cancer patients and their relatives. Aust N Z J Med 1999;29:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trevino KM, Zhang B, Shen MJ et al. Accuracy of advanced cancer patients' life expectancy estimates: The role of race and source of life expectancy information. Cancer 2016;122:1905–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orom H, Kiviniemi MT, Underwood W 3rd et al. Perceived cancer risk: Why is it lower among nonwhites than whites? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramirez AS, Rutten LJ, Oh A et al. Perceptions of cancer controllability and cancer risk knowledge: The moderating role of race, ethnicity, and acculturation. J Cancer Educ 2013;28:254–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson R, Mills ME. Cancer patients' satisfaction with communication, information and quality of care in a UK region. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costantini M, Morasso G, Montella M et al. Diagnosis and prognosis disclosure among cancer patients. Results from an Italian mortality follow‐back survey. Ann Oncol 2006;17:853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shin JA, El‐Jawahri A, Parkes A et al. Quality of life, mood, and prognostic Understanding in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Palliat Med 2016;19:863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scheibe S, Carstensen LL. Emotional aging: Recent findings and future trends. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2010;65B:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Solomon S, Lawlor K. Death anxiety: The challenge and the promise of whole person care In: Hutchinson TA, ed. Whole Person Care: A New Paradigm for the 21st Century. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2011:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sriram N, Mills J, Lang E et al. Attitudes and stereotypes in lung cancer versus breast cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carter AJ, Nguyen CN. A comparison of cancer burden and research spending reveals discrepancies in the distribution of research funding. BMC Public Health 2012;12:526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe‐Galloway S et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health 2014;39:1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bergman J, Saigal CS, Lorenz KA et al. Hospice use and high‐intensity care in men dying of prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tucker‐Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H et al. Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psychooncology 2015;24:572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rikard RV, Thompson MS, McKinney J et al. Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: A third look at the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). BMC Public Health 2016;16:975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishler EG, Amara Singham LR, Hauser ST et al. Social contexts of health, illness, and patient care. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health 2003;93:248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arpey NC, Gaglioti AH, Rosenbaum ME. How socioeconomic status affects patient perceptions of health care: A qualitative study. J Prim Care Community Health 2017;8:169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M et al. Socio‐economic status of the patient and doctor‐patient communication: Does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns 2005;56:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Becker G, Newsom E. Socioeconomic status and dissatisfaction with health care among chronically ill African Americans. Am J Public Health 2003;93:742–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC et al. Physicians' propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients' awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med 2014;17:673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hui D, Cerana MA, Park M et al. Impact of oncologists' attitudes toward end‐of‐life care on patients' access to palliative care. The Oncologist 2016;21:1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.The Associated Press‐NORC Center for Public Affairs Research . Finding quality doctors: How Americans evaluate provider quality in the United States. Available at http://www.apnorc.org/PDFs/Finding%20Quality%20Doctors/Finding%20Quality%20Doctors%20Research%20Highlights.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2018.

- 84.Brennan F, Stewart C, Burgess H et al. Time to improve informed consent for dialysis: An international perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1001–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kliger AS. Quality measures for dialysis: Time for a balanced scorecard. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]