Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) contained in airborne particulate matter have been identified as a contributing factor for inflammation in the respiratory tract. Recently, interleukin-33 (IL-33) is strongly suggested to be associated with airway inflammation. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a receptor for PAHs to regulate several metabolic enzymes, but the relationships between AhR and airway inflammation are still unclear. In this study, we examined the role of AhR in the expression of IL-33 in macrophages. THP-1 macrophages mainly expressed IL-33 variant 5, which in turn was strongly induced by the AhR agonists 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and kynurenine (KYN). AhR antagonist CH223191 suppressed the increase in IL-33 expression. Promoter analysis revealed that the IL-33 promoter has 2 dioxin response elements (DREs). AhR was recruited to both DREs after treatment with TCDD or KYN as assessed by gel shift and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. A luciferase assay showed that one of the DREs was functional and involved in the expression of IL-33. Macrophages isolated from AhR-null mice expressed only low levels of IL-33 even in response to treatment with AhR ligands compared with wild-type cells. The treatment of THP-1 macrophages with diesel particulate matter and particle extracts increased the mRNA and protein expression of IL-33. Taken together, the results show that ligand-activated AhR mediates the induction of IL-33 in macrophages via a DRE located in the IL-33 promoter region. AhR-mediated IL-33 induction could be involved in the exacerbation and/or prolongation of airway inflammation elicited by toxic chemical substances.

Keywords: AhR, IL-33, macrophages, diesel particulate matter

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) belongs to the superfamily of basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim (bHLH/PAS) domain-containing proteins and becomes activated by binding of various low molecular weight compounds, such as 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and benzo(a)pyrene (B(a)P) (Stockinger et al., 2014). AhR is a transcription factor located in the cytoplasm that is retained in a complex with a variety of chaperone proteins, including HSP90. When ligands bind to AhR, the AhR complex translocates into the nucleus where it forms a heterodimer with AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) and binds to dioxin/xenobiotic response elements (DREs/XREs) in the promoter regions of a wide variety of target genes to activate mRNA transcription. AhR is highly expressed in barrier organs such as the lungs and skin. Some ligand-metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP1A1 and UGT1A1, are well-known targets of AhR. Thus, the AhR pathway is an endogenous detoxification mechanism against exogenous harmful compounds.

Recently, the function of AhR in the immune system has become the focus of AhR biology. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) has a DRE site in its promoter region (Vogel et al., 2000), and polychlorinated dibenzodioxins such as TCDD induce COX-2 expression and prostaglandin synthesis (Puga et al., 1997). AhR can activate lung fibroblasts and contribute to cigarette smoke-induced inflammation and lung disorders in a COX-2 and prostaglandin-dependent manner (Martey et al., 2005). We also showed that COX-2 expression was AhR-dependently upregulated in human macrophages by exposure to air pollution particles (Vogel et al., 2005). The expression of other inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-1β (Sutter et al., 1991), interleukin-6 (Hollingshead et al., 2008), interleukin-8 (Vogel et al., 2011), interleukin-17 (Quintana et al., 2008), interleukin-22 (Lee et al., 2012), and tumor necrosis factor α (Lecureur et al., 2005), is also upregulated by AhR. We identified RelB as a new AhR binding partner that functions separately from the other AhR binding partner ARNT (Vogel et al., 2007). The AhR-RelB complex can bind to a RelBAHRE responsive element to regulate the expression of IL-8 for instance. Interestingly, the expression of inflammatory cytokines can be suppressed by AhR in certain situations (Kimura et al., 2009). The mechanism by which AhR induces inflammatory molecules is complicated, but the AhR binding partner could determine the regulatory pattern of the target genes.

One important issue in AhR-dependent inflammation is lung pathology accompanied by the inhalation of airborne particles and/or cigarette smoke, which include numerous environmental chemicals that function as AhR ligands. In particular, AhR activation by environmental chemicals is considered to be involved in the onset or exacerbation of asthma (Manners et al., 2014). Increasing evidence shows that interleukin-33 (IL-33), a secreted cytokine that belongs to the interleukin-1 family, is important in the pathophysiology of asthma and other inflammatory airway disorders. IL-33 is an alarmin that accumulates in the nuclei and is passively released into the extracellular space by cellular damage. In 2010, an IL-33 mutation was reported to be related to asthma for the first time in a large-scale human study (Moffatt et al., 2010). It has been reported that the amount of IL-33 production is proportional to asthma severity (Prefontaine et al., 2009, 2010). IL-33 is released from airway epithelial cells or macrophages to bind to its receptor, ST2. IL-33 subsequently activates Th2 cells and mast cells and then stimulates the release of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin-5 and interleukin-13 by activating group 2 innate lymphoid cells (Drake and Kita, 2017). Therefore, IL-33 is suggested to exacerbate allergic airway inflammation via immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mast cell and/or Th2-eosinophil pathways.

There are a few papers that explore the relationship between AhR and IL-33. Exposure to low concentrations of B(a)P, a potent AhR ligand, increased IL-33 protein expression in mouse lungs sensitized with ovalbumin (Yanagisawa et al., 2016). In addition, Weng et al. reported that IL-33 expression increased in cultured bronchial epithelial cells isolated from asthma patients in response to treatment with diesel particulate matter (DPM) and that AhR was recruited to the IL-33 promoter region (Weng et al., 2018). IL-33 is highly expressed in macrophages. It is well known that macrophages are important in inflammatory diseases of the respiratory system, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the regulation of IL-33 by AhR and the mechanism of IL-33 expression in macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

THP-1 cell culture and differentiation

The human monocytic cell line, THP-1, was obtained from ATCC (TIB-202) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). THP-1 cells (5 × 105 cells/ml) were differentiated using 160 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 2 days and then incubated in fresh RPMI 1640 medium (including 10% FBS) for an additional 2 days (Daigneault et al., 2010).

Total RNA extraction and real-time PCR

mRNA levels were determined according to the protocol described in our previous report (Ishihara et al., 2017). The primer sequences are presented in Table 1. mRNA levels were normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene β-actin, and the values for the treated samples were divided by those for the untreated samples to calculate the relative mRNA levels.

Table 1.

Primers for Real-Time PCR Expression Analysis

| Target | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Human IL33 V1 | TGCAGCTCTTCAGGGAAGAAA | TCTGTTGGGATTTTCCCAGCTT |

| Human IL33 V4 | AGAGAGGGTGAGTAGGAGCA | TCTGTTGGGATTTTCCCAGCTT |

| Human IL33 V5 | CCTCATCATCTGAGACCAGCA | TCTGTTGGGATTTTCCCAGCTT |

| Human IL33 total | TGAATCAGGTGACGGTGTT | TGGTCTGGCAGTGGTTTT |

| Human CYP1A1 | TAGACACTGATCTGGCTGCAG | GGGAAGGCTCCATCAGCATC |

| Human β-actin | GGACTTCGAGCAAGAGATGG | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG |

| Mouse IL33b | GGGCTCACTGCAGGAAAGTA | TCAGGTTTCTCAATACAGACAGGA |

| Mouse β-actin | AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC | CTCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAA |

Promoter analysis

Promoter analysis of the 5′-upstream regulatory region of human and mouse IL-33 was performed with the TFSEARCH program (Heinemeyer et al., 1998). Genetic sequence data in GenBank were used for the analysis.

Preparation of nuclear proteins and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were isolated from THP-1 cells as described previously (Vogel et al., 2014). In brief, 5 × 106 cells were harvested in PBS containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 0.05 μg/μl aprotinin. After centrifugation, the cell pellets were gently resuspended in 1 ml of hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.13 μM okadaic acid, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 μg/ml each leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin). The cells were allowed to swell on ice for 15 min and then homogenized with 25 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation for 1 min at 16 000 × g, the nuclear pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of ice-cold high-salt buffer (hypotonic buffer with 420 mM NaCl and 20% glycerol). The samples were passed through a 21-gauge needle and stirred for 30 min at 4°C. The nuclear lysates were microcentrifuged at 16 000 × g for 20 min, separated into aliquots, and stored at −80°C.

DNA-protein binding reactions were carried out in a total volume of 15 μl containing 10 μg of nuclear protein, 60 000 counts/min of rat CYP1A1 DRE consensus (5′-GATCTGGCTCTTCTCACGCAACTCCG-3′), human IL-33 DRE1 (5′-CAGGATCTACCACGCATACACTTTC-3′) or human IL-33 DRE2 (5′-GTGGCTCACGCCTGTAATCCC-3′) oligonucleotide, 25 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC). The samples were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Competition experiments were performed in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled DNA fragments. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by exposure of the dehydrated gels to X-ray film.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-AhR antibody (ab2769, Abcam) or control IgG antibody with the Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting immunoprecipitates including DNA were analyzed by real-time PCR using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are listed in Table 2. Human genomic DNA extracted from THP-1 macrophages was used as a positive control. The percentage input of each sample was calculated from the Ct values.

Table 2.

Primers for the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

| Target | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| hIL33 DRE1 | AAGAATGTCAGGATCTACCACGC | TTGCAATATAGGCTCTAGGCAGTG |

| hIL33 DRE2 | GTGTAACTCTTTGACAGTGCTACA | GAACTCCTGACCGCAAGTGA |

Luciferase assay

Approximately 1300 bp of the promoter region flanking human IL-33 exon 1c was cloned into the pNL 3.2 luciferase reporter vector (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) by using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa Bio). Mutation of the DREs was performed with site-directed mutagenesis (Ishihara et al., 2011) and then confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

The pNL vector containing the IL-33 promoter region or the mutated DRE was transfected into THP-1 cells using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with reagents. Luciferase activity was measured using the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) with a GloMax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega) (Ishihara et al., 2015b).

Preparation of bone marrow-derived macrophages

Male C57BL/6J wild-type mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (West Sacramento, California). AhR-null (AhR−/−) mice were generated and kindly provided by Dr Christopher Bradfield from the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research at the University of Wisconsin. The mice were housed (4 per cage) in a specific pathogen-free facility in a humidity- and temperature-controlled room. The animals were maintained on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle and had free access to water and food according to the guidelines set by the University of California, Davis. Mice were allowed to adapt to the facility for 1 week.

Primary bone marrow progenitor cells were isolated and differentiated as described previously (Castaneda et al., 2018). Briefly, the femurs were isolated under sterile conditions, and bone marrow cells were extracted via an RPMI medium-loaded syringe. The cells were passed through a 30 μm cell strainer, and the supernatant was centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 × g. The supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was resuspended and cultured in RPMI medium. Bone marrow-derived macrophage differentiation was performed in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 20 ng/ml; Tonbo Biosciences, San Diego, California) for 7 days.

Preparation of alveolar macrophages

Alveolar macrophages were prepared from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of male C57BL/6J wild-type mice. Mice were killed by an over dose of pentobarbital and were then exsanguinated by cutting the abdominal artery. The trachea was isolated and cannulated with a 23-gauge blunt needle. The lungs were lavaged 5 times with 0.8 ml sterile Ca2+ and Mg2+-free PBS to collect the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The fluid was centrifuged at 350 × g for 10 min and resulted pellets were suspended with RPMI 1640 medium including 10% FBS. The cell suspensions were transferred into 12-well plates with a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml/well. After 2 h incubation, cells were used for experiments.

Preparation of monocyte-derived macrophages from human blood

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from buffy coats of healthy individuals (obtained from the Sacramento Blood Center, California) by Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation, according to the previous report (Chang et al., 2004). CD14+ monocytes from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were then positively selected using anti-CD14 antibody-conjugated magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, California). Purified monocytes (> 95% purity, as determined by flow cytometry with staining for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD20) (data not shown) were cultured at a density of 1.5–2 × 106 cells/ml in 12-well plates (1 ml per well). Macrophage medium consisted of RPMI 1640 medium containing 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM HEPES, 10% FBS, and recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rHu M-CSF 50 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota). M-CSF was replenished every other day. After 6 days of culture, cells were washed by PBS to remove nonadherent cells and then were used for experiments.

Preparation of DPM extracts

DPM NIST 1650b was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Procedures for the preparation of DPM for cell treatments were previously described (Vogel et al., 2005). DPM was suspended in RNase-free water, sonicated briefly and added to the THP-1 cells in culture. For the DPM extract, the particles were added to a Soxhlet apparatus and extracted with dichloromethane overnight. The extract was filtered (0.45 μm Acrodisc), concentrated to 1 ml by TurboVap, and stored in precleaned amber vials. The extract obtained was dried under a gentle stream of high purity nitrogen and then redissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide for testing.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Ishihara et al., 2015a). Briefly, cells were collected and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS). Equal amounts of protein were loaded, separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The blocked membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-IL-33 (sc-130625, Santa Cruz) and anti-α-tubulin (T5168, Sigma-Aldrich). Then, the membrane was incubated in solutions with peroxide-conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher Scientific) and visualized using peroxide substrates (SuperSignal West Pico, ThermoFisher Scientific). The band intensity was quantified using Image J software.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the mean ± SE The statistical analyses were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student’s t test or Dunnett’s test. P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of the IL-33 Exon Utilized in Human Macrophages

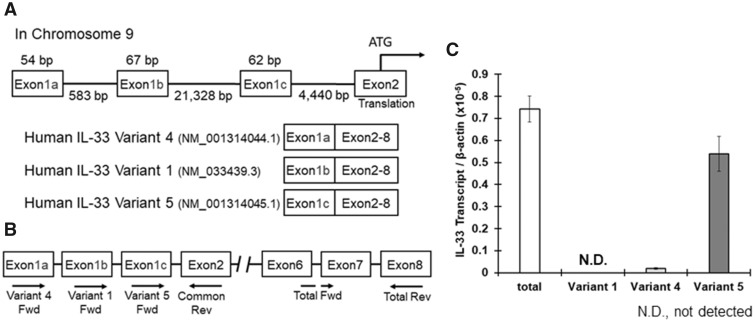

The human IL-33 gene is encoded on chromosome 9 and consists of 8 exons. Human IL-33 has 3 variants of exon 1, exons 1a, 1b, and 1c, which are described in Figure 1A (Tominaga et al., 2013), and different types of cells use different exon variants to regulate IL-33 expression. For example, human umbilical vein endothelial cells mainly use exon 1b, whereas NHEK (keratinocytes) and WI38 (fibroblasts) cells use exon 1c (Tominaga et al., 2013). The IL-33 mRNA variants including exons 1a, 1b, or 1c are classified into variants 4, 1, and 5, respectively, in the GenBank (Figure 1A); we used the GenBank classification system (IL-33 variants 1, 4, and 5). We first examined which variant is expressed in macrophages using specific primers against each IL-33 variant (Figure 1B). Total RNA was extracted from THP-1 cells treated with PMA for macrophage-like differentiation, and then real-time PCR was performed. IL-33 variant 5 was the primary variant amplified, and the variant 5 amplification rate was almost the same as the total IL-33 mRNA amplification rate. IL-33 variant 4 was rarely detected, and IL-33 variant 1 was not detected by real-time PCR (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Interleukin-33 (IL-33) mRNA expression in THP-1 macrophages. A, The human IL-33 gene includes 3 exon 1 variants named 1a, 1b, and 1c (Tominaga et al., 2013). The position of each exon is described. The mRNA variants with exons 1a, 1b, or 1c are registered in the GenBank as variant 4, variant 1, or variant 5, respectively, and are translated into the same protein because exons 2 (includes the start codon) to 8 are common among the 3 variants. B, The primer positions used to detect the mRNA levels of total human IL-33 and variants 1, 4, and 5 are shown. C, Total RNA was extracted from THP-1 macrophages, and cDNA was synthesized. IL-33 mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 4).

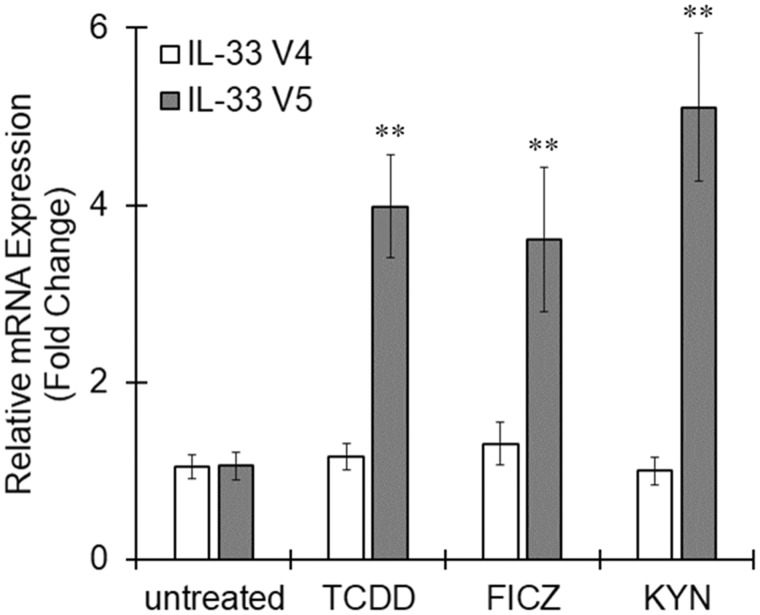

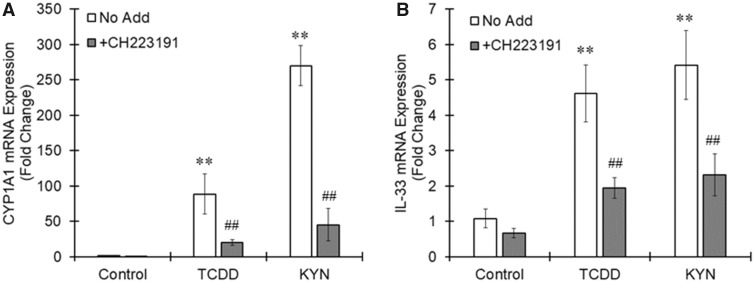

IL-33 Expression Induced by Activated AhR in Macrophages

When THP-1 macrophages were stimulated with AhR agonists TCDD, 6-Formylindolo(3, 2-b)carbazole (FICZ), or kynurenine (KYN) for 6 h, IL-33 variant 5 expression was significantly increased by all 3 agonists, although these AhR agonists showed no effects on IL-33 variant 4 expression (Figure 2). Pretreatment with a specific AhR antagonist, CH223191, clearly canceled the increased expression of CYP1A1 and IL-33 induced by TCDD or KYN (Figure 3). Therefore, IL-33 variant 5 could be one of the targets of activated AhR in macrophages.

Figure 2.

Interleukin-33 (IL-33) expression induced by aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were treated with the AhR agonists 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM), 6-Formylindolo(3, 2-b)carbazole (FICZ) (100 nM), or kynurenine (KYN) (50 μM) for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted, and cDNA was synthesized. The mRNA levels of variants 4 and 5 were measured by real-time PCR. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 6). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test. **p < .01 versus the untreated group.

Figure 3.

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-dependent induction of interleukin-33 (IL-33) expression in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were pretreated with an AhR antagonist, CH223191 (10 μM), 20 min before treatment with 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM) or kynurenine (KYN) (50 μM). Six hours after the AhR agonist treatment, total RNA was prepared from the cells, followed by real-time PCR measurement of the (A) CYP1A1 and (B) IL-33 variant 5 mRNA levels. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 4). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test or a t test. **p < .01 versus the control group. ##p < .01 versus the No Add group.

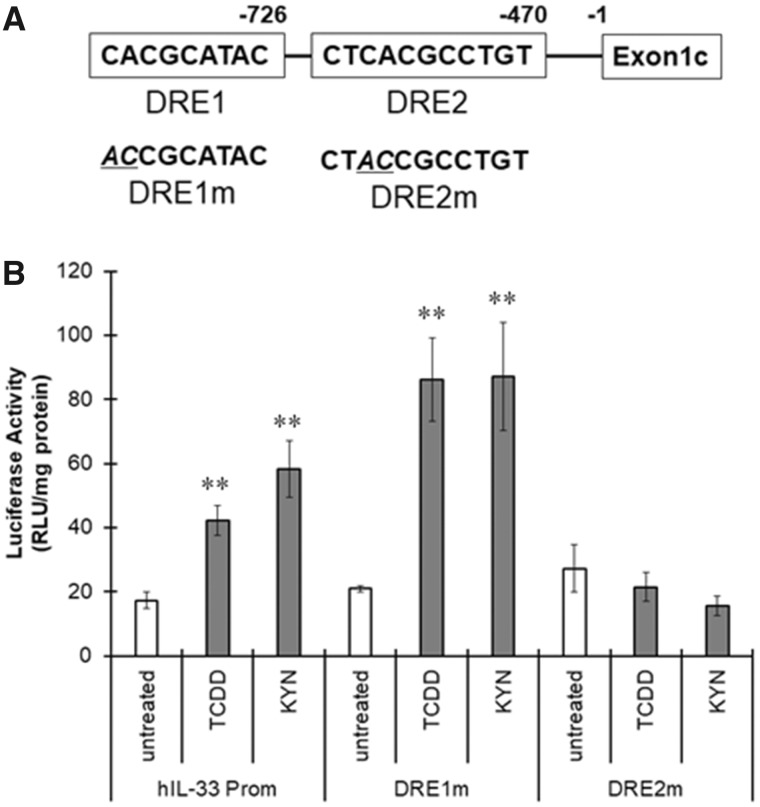

Functional DRE in the Promoter Region of IL-33 Variant 5

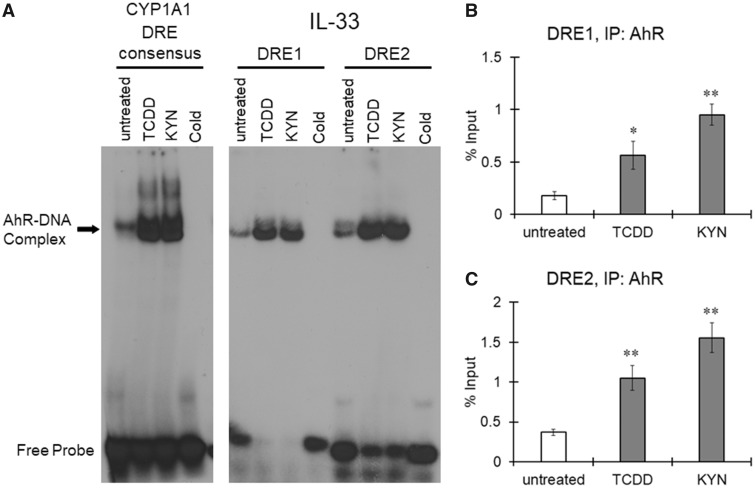

We identified 2 DREs upstream of human IL-33 exon 1c, named DRE1 and DRE2, in silico (Figure 5A); thus, we examined AhR recruitment to these DREs in the IL-33 promoter by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. A signal for the AhR-DNA complex was detected in nuclear extracts prepared from untreated THP-1 macrophages using the rat CYP1A1 DRE as a probe (Figure 4A). Treatment with TCDD or KYN increased the intensity of the AhR-DNA complex band, indicating that AhR was activated by TCDD and KYN in THP-1 macrophages (Figure 4A). When nuclear extracts of untreated THP-1 macrophages were mixed with oligonucleotides, including human IL-33 DRE1 or DRE2 (Figure 4A), the AhR-DNA complex was detected. The signal for these AhR-DNA complexes largely increased when the nuclear extract from TCDD- and KYN-treated cells was tested (Figure 4A), indicating that activated AhR can bind to human IL-33 DRE1 and DRE2. A ChIP assay showed that the amount of DNA including IL-33 DRE1 and DRE2 precipitated with the anti-AhR antibody increased after treatment with TCDD and KYN (Figs. 4B and 4C). Taken together, these results indicate that activated AhR strongly binds to both DRE1 and DRE2 in the IL-33 promoter region in macrophages.

Figure 5.

Involvement of the dioxin response element (DRE) located in the interleukin-33 (IL-33) promoter region in aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-induced IL-33 expression. A, The DRE sequences identified in the human IL-33 promoter region are named DRE1 and DRE2. B, THP-1 macrophages were transfected with pNL containing the human IL-33 promoter harboring wild-type DREs, the DRE1 mutation (DRE1m) or the DRE2 mutation (DRE2m) and then treated with 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM) and kynurenine (KYN) (50 μM) for 6 h. The cells were collected and lysed to measure luciferase activity. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 6). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test. *p < .5, **p < .01 versus the untreated group.

Figure 4.

Recruitment of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) to the dioxin response elements (DREs) in the interleukin-33 (IL-33) promoter region. THP-1 macrophages were treated with 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM) or kynurenine (KYN) (50 μM) for 1 h. A, Nuclear extracts from untreated or AhR ligand-treated cells were used for an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), which was performed using double-stranded, 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the DRE binding sequence of the rat CYP1A1 promoter (left panel) or human IL-33 promoter (right panel). To confirm specificity, a 100-fold excess of unlabeled DRE oligonucleotide was added (cold). B, Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed to assess the binding of AhR to DREs within the human IL-33 promoter region. Human genomic DNA (input for precipitation) was used as a positive control, and immunoprecipitation with a nonspecific antibody (IgG) was used as a negative control. The resulting precipitants were analyzed by real-time PCR, and the percent input was calculated. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test. **p < .01 versus the untreated group.

We cloned an approximately 1300 bp region upstream of the human IL-33 exon 1c into the pNL vector and introduced mutations in the DRE1 and DRE2 sequences to generate vectors harboring DRE-mutated IL-33 promoters, named DRE1m and DRE2m, respectively (Figure 5B). When the THP-1 macrophages transfected with pNL including the IL-33 promoter were treated with TCDD or KYN, luciferase activity was significantly higher than that of the untreated cells (Figure 5B). Although the response of DRE1m to TCDD or KYN was higher than that of the nonmutated IL-33 promoter, DRE2m did not function in the presence of TCDD and KYN (Figure 5B). Therefore, DRE2 in the promoter region of human IL-33 is considered to be responsible for IL-33 induction by activated AhR.

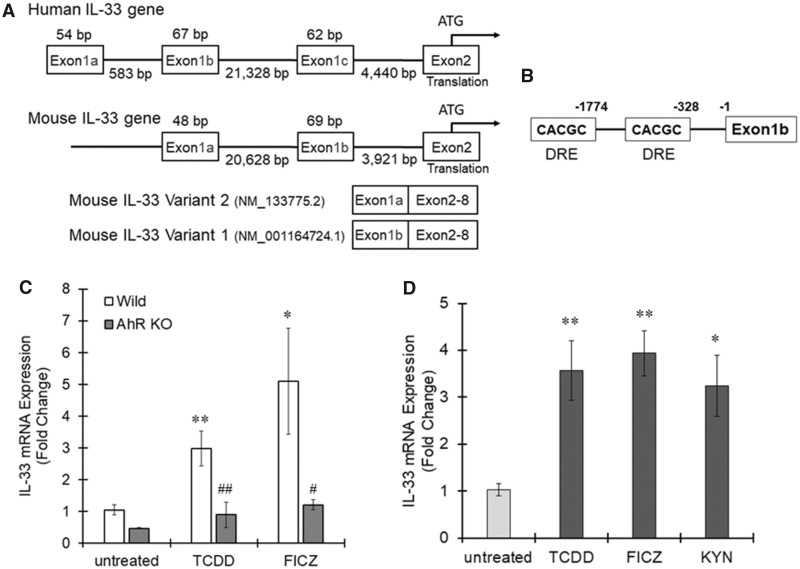

AhR-Dependent IL-33 Induction in Murine Macrophages

To confirm IL-33 induction by activated AhR in macrophages, we next used bone marrow-derived macrophages prepared from wild-type and AhR-null mice. Two types of IL-33 variants, IL-33a and IL-33b, with different exon 1 variants, exons 1a and 1b, respectively, are reported in mice (Figure 6A) (Talabot-Ayer et al., 2012). Given their chromosomal position and homology, mouse exons 1a and 1b are considered to correspond with human exons 1b and 1c, respectively (Figure 6A). This conclusion is supported by a report that mouse macrophages express an IL-33 mRNA transcript containing exon 1b (Talabot-Ayer et al., 2012). In silico promoter analysis revealed that 2 DRE core sequences exist in the upstream region of exon 1b and that no DRE core sequence was detected upstream of exon 1a (Figure 6B), suggesting that IL-33 is regulated by AhR in mouse macrophages, similar to how it is regulated in human macrophages. Wild-type bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with TCDD or FICZ showed significantly higher IL-33b expression than untreated cells (Figure 6C). There was no change in IL-33b expression in AhR-null bone marrow macrophages treated with TCDD and FICZ (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-dependent interleukin-33 (IL-33) induction in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. A, The mouse IL-33 gene includes 2 exon 1 variants, 1a and 1b (Talabot-Ayer et al., 2012). The position of each exon is described. Two mRNA variants containing exons 1a or 1b are registered in the GenBank as variant 2 (IL-33a) or variant 1 (IL-33b), respectively, and are translated into the same protein because exons 2 (includes the start codon) to 8 are common between the 2 variants. B, Dioxin response element (DRE) core sequences were identified in the mouse IL-33 promoter region. C, Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages prepared from wild-type or AhR-null mice were treated with 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM) and 6-Formylindolo(3, 2-b)carbazole (FICZ) (100 nM) for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted from the cells, and real-time PCR was subsequently performed to measure IL-33b mRNA expression. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 4–5). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test or a t test. *p < .05, **p < .01 versus the untreated group. #p < .05, ##p < .01 versus the wild-type group. D, Mouse alveolar macrophages were treated with TCDD (10 nM), FICZ (100 nM), or KYN (50 μM) for 6 h and then IL-33b expression was evaluated by real-time PCR. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 5). Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test. *p < .05, **p < .01 versus the untreated group.

When mouse alveolar macrophages were stimulated by AhR agonists, TCDD, FICZ, or KYN for 6 h, the expression of IL-33b significantly increased with all AhR ligands (Figure 6D). Together, these results show that IL-33 is regulated by AhR in mouse macrophages.

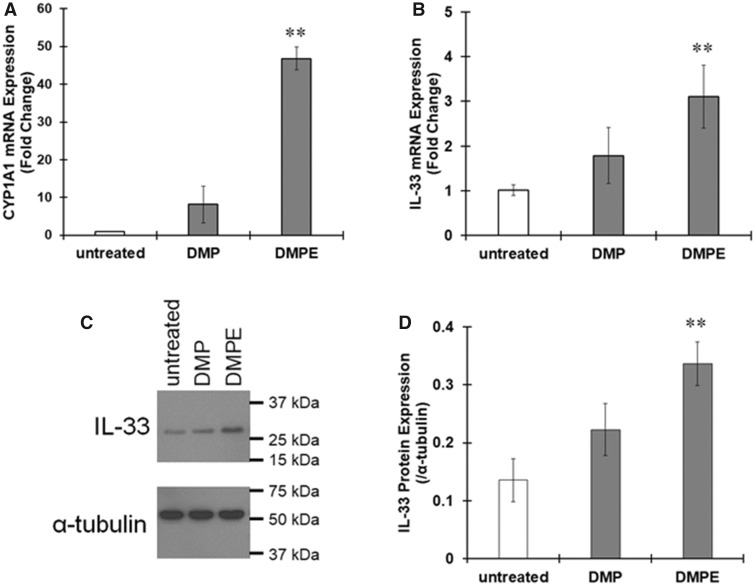

IL-33 Induction by DPMs in Macrophages

We next examined the effects of diesel particles on THP-1 macrophages. When macrophages were treated with DPMs or DPM extracts for 6 h, CYP1A1 mRNA expression largely increased (Figure 7A), indicating DPMs and the extracts activated AhR. IL-33 mRNA levels also increased in response to DPMs or the extracts (Figure 7B), and the amount of IL-33 protein was clearly increased by treatment with DPMs or DPM extracts (Figure 7C). These data suggest that chemicals in diesel particles induce elevated expression of IL-33 by activating AhR.

Figure 7.

Upregulation of interleukin-33 (IL-33) expression by diesel particulate matter (DPM) in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were treated with DPM (5 μg/ml) or DPM extracts (DPME, 10 μg/ml) for 6 h. A and B, The mRNA expression of (A) CYP1A1 and (B) IL-33 variant 5 was evaluated by real-time PCR. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test. **p < .01 versus the untreated group. C and D, IL-33 protein expression was evaluated by immunoblotting. C, Representative images of immunoblotting. D, The band intensity was measured, and the protein levels of IL-33 were divided by those of α-tubulin to calculate the relative protein levels. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test. **p < .01 versus the untreated group.

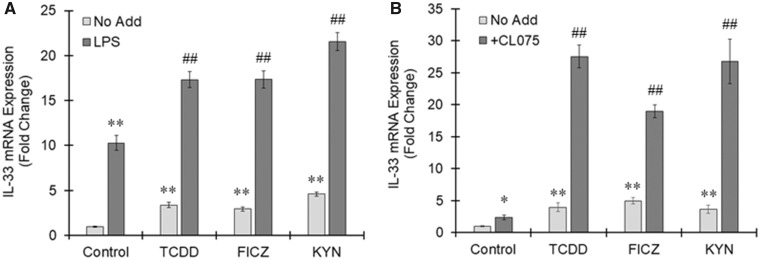

Interaction Between AhR-Dependent IL-33 Induction and Inflammation

THP-1 macrophages were treated with TCDD, FICZ, or KYN in the presence or absence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 agonist. LPS alone induced IL-33 expression in THP-1 macrophages, suggesting that IL-33 is elicited downstream of TLR4 signaling (Figure 8A). AhR-dependent induction of IL-33 largely increased in macrophages with TLR4 activation (Figure 8A). CL075 is a thiazoloquinolone derivative that binds to and activates TLR8 in human neutrophils and dendritic cells. Figure 8B shows that TCDD, FICZ, as well as KYN induced the expression of IL-33 in human macrophages derived from blood monocytes. The highest induction of IL-33 in resting human macrophages was found after treatment with FICZ (approximately 5-fold increases) (Figure 8B). The induction of IL-33 by AhR ligands was further increased in TLR8-activated human macrophages and led to 27-fold increase after treatment with TCDD and KYN and a 19-fold increase by FICZ in the presence of CL075 (Figure 8B). These results suggest that AhR-induced IL-33 expression is enhanced under inflammatory conditions.

Figure 8.

Enhanced interleukin-33 (IL-33) expression by aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands under inflammatory condition. A, THP-1 macrophages were treated with 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (10 nM), 6-Formylindolo(3, 2-b)carbazole (FICZ) (100 nM), or kynurenine (KYN) (50 μM) for 6 h in the presence or absence of LPS (10 ng/ml). IL-33 variant 5 expression was assessed by real-time PCR. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 4). Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett's test or a t test. **p < .01 versus the No Add, control group. ##p < .01 versus the No Add group. B, Human macrophages derived from blood monocytes were treated with TCDD (1 nM), FICZ (100 nM), or KYN (50 μM) in the presence or absence of CL075 (5 μg/ml) for 24 h. Real-time PCR was performed to measure IL-33 variant 5 mRNA. The values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's test or a t test. *p < .05, **p < .01 versus the No Add, control group. ##p < .01 versus the No Add group.

DISCUSSION

The human IL-33 gene includes 8 exons. Exon 2 contains the translation start site, but 3 types of exon 1, exons 1a, 1b, and 1c corresponding to variants 4, 1 and 5, respectively, have been identified (Tominaga et al., 2013). THP-1 macrophages expressed variants 4 and 5, and the mRNA levels of variant 5 were 30 times higher than those of variant 4. Thus, human macrophages mainly use a promoter region flanking exon 1c of IL-33. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells mainly use exon 1b and weakly use exon 1a, whereas NHEK (keratinocytes) and WI38 (fibroblasts) cells use exon 1c (Tominaga et al., 2013). Thus, the IL-33 promoter usage depends on the cell type. Tissue- or cell type-specific gene expression is controlled by the expression and activity of transcription factors and/or the open or closed configurations of the chromosomal domains. E26 transformation-specific (ETS) family transcription factors such as PU.1 and ETS2 play an important role in the differentiation and homeostasis of macrophages (Greaves and Gordon, 2002). When we analyzed the promoter region of human IL-33 in silico, several EST family consensus sequences, GGAA-containing sequences, were identified in all exon 1 variants (data not shown). Reportedly, the chromatin modifications H3K4me1 and H3H27ac are observed in activated enhancers in macrophages, and these modifications are distinct from general modifications; H3K4me3 is an activating mark, and H3K27me3 is a repressive mark (Lavin et al., 2014). Transcription factor regulation and chromatin modification might contribute to macrophage-specific IL-33 variant 5 expression.

In this study, IL-33 variant 5 (exon 1c) expression was increased by AhR ligands. There are 2 DREs containing the core CACGC sequence 726 (DRE1) and 470 (DRE2) bp upstream of IL-33 exon 1c. EMSA and ChIP assays clearly showed that AhR was recruited to both DREs, but a luciferase assay with mutated DREs revealed that DRE2, the DRE closer to exon 1c, could be involved in IL-33 induction by activated AhR. Interestingly, compared with the wild-type (not mutated) IL-33 promoter, the promoter with the DRE1 mutation increased the luciferase signals. Therefore, DRE1 can suppress IL-33 expression in a manner dependent on AhR ligands. In general, the association of a transcription factor with a corepressor suppresses downstream gene expression. Estrogen receptor α (ERα) reportedly suppresses AhR-ARNT-dependent transcription (Beischlag and Perdew, 2005). ERα can interact with AhR-ARNT complexes bound to the CYP1A1 promoter region to decrease the CYP1A1 expression induced by AhR. Gradin et al. reported a factor that has histone deacetylase activity and can directly bind to DREs to suppress the dioxin signal (Gradin et al., 1999), which was identified as AhR repressor later (Mimura et al., 1999). Further experiments are needed to uncover the role of the DREs upstream of IL-33 exon 1c in IL-33 expression.

Mouse macrophages are reported to use a promoter region flanking IL-33 exon 1b to transcribe IL-33 mRNA. Mouse IL-33 exon 1b is very similar to human IL-33 exon 1c regarding the position of exon 2 and sequence homology. Two DRE core sequences were identified upstream of mouse IL-33 exon 1b. Considering that human DRE2 functions in the presence of AhR ligands, the DRE closer to mouse IL-33 exon 1b might contribute to AhR-dependent IL-33 expression. We found DRE cores upstream of the human IL-33 exons 1a and 1b (data not shown). Although macrophages express IL-33 variant 4, IL-33 variant 4 expression was not affected by treatment with AhR ligands. The DREs flanking human IL-33 exon 1a (variant 4) exists approximately 1200 and 1600 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site in exon 1a, and thus, compared with DRE2, which exists 470 bp upstream of the transcription start site in exon 1c that was involved in IL-33 induction in this study, these DREs are distal. Therefore, the distance from the transcription initiation site might be a reason that the DREs flanking exon 1a do not function in IL-33 transcription. Namely, IL-33 induction by activated AhR could depend on the type of exon 1 that a cell natively uses for IL-33 expression in addition to AhR expression and activity. In fact, the IL-33 expression induced by AhR ligands is different among cell types. Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF7 cells and human lymphoma U937 cells showed increased expression of IL-33 in the presence of AhR ligands, whereas human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells and human lung carcinoma A549 cells did not (data not shown). In addition, there is no DRE core sequence within 3000 bp upstream of the rat IL-33 transcription start site, and no induction of IL-33 expression is observed in the lungs of TCDD-treated Wistar rats (unpublished results). Thus, IL-33 induction by activated AhR can be different between species as well as cell types. IL-33 expression is regulated in a complicated manner even among mammals.

Recently, Weng et al. reported that AhR contributes to the epithelium-derived expression of cytokines, including IL-33, and that AhR is observed to be recruited to the IL-33 promoter region by ChIP assay (Weng et al., 2018). Comparing the primer sequences used in their report with the sequence of the IL-33 promoter region, there is no DRE core sequence in the region where AhR was recruited. There are several reports on nonclassical DREs such as AHRE-II (Sogawa et al., 2004), AnC (Zhang et al., 2003), NC-XRE (Huang and Elferink, 2012), and RelBAHRE (Vogel et al., 2007). When we searched for these nonclassical DREs in the promoter region from 1 to 3000 bp upstream of the transcription starting site of IL-33 variant 5 mRNA, 1 RelBAHRE was found between DRE1 and DRE2. Therefore, mechanism(s) other than classic DRE function such as RelBAHRE might be involved in IL-33 induction by the AhR pathway.

DPM exposure elicited IL-33 expression in macrophages. DPMs upregulate Th2 cytokine expression in CD4+ T cells in vitro and promote allergic airway inflammation in vivo (Xia et al., 2015). IL-33 also directly acts on CD4+ T cells, mast cells, and eosinophils to aggravate the adaptive phase of type 2 immune responses (Bartemes and Kita, 2012). Considering that IL-33 is closely related to the pathophysiology of asthma, it is plausible that IL-33 induction by AhR could be involved in asthma triggered by environmental chemicals. Macrophages have been reported to respond to LPS to increase IL-33 expression (Schmitz et al., 2005), and this response is probably owing to the fact that NF-kB (RelA) response elements are found in the flanking regions of the human IL-33 exons 1a, 1b, and 1c. In this study, we showed that AhR can induce an inflammatory reaction via the upregulation of IL-33 expression. Therefore, IL-33 induction by chemicals might form a positive-feedback loop to exacerbate chronic inflammation in bronchial asthma and other airway inflammatory disorders.

AhR-dependent IL-33 induction was potentiated in the presence of TLR ligands, LPS, or CL075 in macrophages, suggesting IL-33 overexpression under inflammation. Chronic airway inflammation is the basal pathophysiology of asthma patients, and PM2.5 is well known to be an exacerbating factor for asthma (Gehring et al., 2015). Therefore, enhancement of IL-33 expression by TLR ligands might explain the aggravation of asthma by particle matters. Further study is needed to uncover the relationships between AhR-mediated IL-33 expression and inflammation.

In conclusion, human macrophages express the IL-33 mRNA variant harboring exon 1c. Activated AhR can bind to the DRE flanking region of exon 1c to upregulate IL-33 expression. As many AhR ligands are found in DPMs and are reportedly involved in deteriorating and prolonged airway inflammation, IL-33 induction activated via AhR may contribute to chronic inflammation in the respiratory tract.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms Sarah Y. Kado for technical assistance during the course of this study.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the grant KAKENHI from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, grant number (15KK0024 and 17H04714 to Y.I.) and the grant from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, grant number (R01 ES019898 and R01 ES029126 to C.F.A.V.).

REFERENCES

- Bartemes K. R., Kita H. (2012). Dynamic role of epithelium-derived cytokines in asthma. Clin. Immunol. 143, 222–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beischlag T. V., Perdew G. H. (2005). ER alpha-AHR-ARNT protein-protein interactions mediate estradiol-dependent transrepression of dioxin-inducible gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21607–21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda A. R., Pinkerton K. E., Bein K. J., Magana-Mendez A., Yang H. T., Ashwood P., Vogel C. F. A. (2018). Ambient particulate matter activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in dendritic cells and enhances Th17 polarization. Toxicol. Lett. 292, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. L., Baumgarth N., Yu D., Barry P. A. (2004). Human cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10 homolog inhibits maturation of dendritic cells and alters their functionality. J. Virol. 78, 8720–8731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault M., Preston J. A., Marriott H. M., Whyte M. K., Dockrell D. H. (2010). The identification of markers of macrophage differentiation in PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS One 5, e8668.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake L. Y., Kita H. (2017). IL-33: Biological properties, functions, and roles in airway disease. Immunol. Rev. 278, 173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring U., Wijga A. H., Hoek G., Bellander T., Berdel D., Bruske I., Fuertes E., Gruzieva O., Heinrich J., Hoffmann B. (2015). Exposure to air pollution and development of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis throughout childhood and adolescence: A population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradin K., Toftgard R., Poellinger L., Berghard A. (1999). Repression of dioxin signal transduction in fibroblasts. Identification of a putative repressor associated with Arnt. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13511–13518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves D. R., Gordon S. (2002). Macrophage-specific gene expression: Current paradigms and future challenges. Int. J. Hematol. 76, 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer T., Wingender E., Reuter I., Hermjakob H., Kel A. E., Kel O. V., Ignatieva E. V., Ananko E. A., Podkolodnaya O. A., Kolpakov F. A., et al. (1998). Databases on transcriptional regulation: TRANSFAC, TRRD and COMPEL. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead B. D., Beischlag T. V., Dinatale B. C., Ramadoss P., Perdew G. H. (2008). Inflammatory signaling and aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediate synergistic induction of interleukin 6 in MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 68, 3609–3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Elferink C. J. (2012). A novel nonconsensus xenobiotic response element capable of mediating aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 81, 338–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y., Ito F., Shimamoto N. (2011). Increased expression of c-Fos by extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation under sustained oxidative stress elicits BimEL upregulation and hepatocyte apoptosis. FEBS J. 278, 1873–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y., Itoh K., Ishida A., Yamazaki T. (2015a). Selective estrogen-receptor modulators suppress microglial activation and neuronal cell death via an estrogen receptor-dependent pathway. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 145, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y., Itoh K., Tanaka M., Tsuji M., Kawamoto T., Kawato S., Vogel C. F. A., Yamazaki T. (2017). Potentiation of 17beta-estradiol synthesis in the brain and elongation of seizure latency through dietary supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid. Sci. Rep. 7, 6268.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y., Takemoto T., Itoh K., Ishida A., Yamazaki T. (2015b). Dual role of superoxide dismutase 2 induced in activated microglia: Oxidative stress tolerance and convergence of inflammatory responses. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 22805–22817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A., Naka T., Nakahama T., Chinen I., Masuda K., Nohara K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kishimoto T. (2009). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in combination with Stat1 regulates LPS-induced inflammatory responses. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2027–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin Y., Winter D., Blecher-Gonen R., David E., Keren-Shaul H., Merad M., Jung S., Amit I. (2014). Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell 159, 1312–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecureur V., Ferrec E. L., N’diaye M., Vee M. L., Gardyn C., Gilot D., Fardel O. (2005). ERK-dependent induction of TNFalpha expression by the environmental contaminant benzo(a)pyrene in primary human macrophages. FEBS Lett. 579, 1904–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Cella M., McDonald K. G., Garlanda C., Kennedy G. D., Nukaya M., Mantovani A., Kopan R., Bradfield C. A., Newberry R. D., et al. (2012). AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat. Immunol. 13, 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manners S., Alam R., Schwartz D. A., Gorska M. M. (2014). A mouse model links asthma susceptibility to prenatal exposure to diesel exhaust. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134, 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martey C. A., Baglole C. J., Gasiewicz T. A., Sime P. J., Phipps R. P. (2005). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a regulator of cigarette smoke induction of the cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin pathways in human lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 289, L391–L399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura J., Ema M., Sogawa K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1999). Identification of a novel mechanism of regulation of Ah (dioxin) receptor function. Genes Dev. 13, 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt M. F., Gut I. G., Demenais F., Strachan D. P., Bouzigon E., Heath S., von Mutius E., Farrall M., Lathrop M., Cookson W., et al. (2010). A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prefontaine D., Lajoie-Kadoch S., Foley S., Audusseau S., Olivenstein R., Halayko A. J., Lemiere C., Martin J. G., Hamid Q. (2009). Increased expression of IL-33 in severe asthma: Evidence of expression by airway smooth muscle cells. J. Immunol. 183, 5094–5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prefontaine D., Nadigel J., Chouiali F., Audusseau S., Semlali A., Chakir J., Martin J. G., Hamid Q. (2010). Increased IL-33 expression by epithelial cells in bronchial asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, 752–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puga A., Hoffer A., Zhou S., Bohm J. M., Leikauf G. D., Shertzer H. G. (1997). Sustained increase in intracellular free calcium and activation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in mouse hepatoma cells treated with dioxin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 54, 1287–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana F. J., Basso A. S., Iglesias A. H., Korn T., Farez M. F., Bettelli E., Caccamo M., Oukka M., Weiner H. L. (2008). Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 453, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J., Owyang A., Oldham E., Song Y., Murphy E., McClanahan T. K., Zurawski G., Moshrefi M., Qin J., Li X., et al. (2005). IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity 23, 479–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogawa K., Numayama-Tsuruta K., Takahashi T., Matsushita N., Miura C., Nikawa J., Gotoh O., Kikuchi Y., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (2004). A novel induction mechanism of the rat CYP1A2 gene mediated by Ah receptor-Arnt heterodimer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 318, 746–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger B., Di Meglio P., Gialitakis M., Duarte J. H. (2014). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Multitasking in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 403–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter T. R., Guzman K., Dold K. M., Greenlee W. F. (1991). Targets for dioxin: Genes for plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 and interleukin-1 beta. Science 254, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talabot-Ayer D., Calo N., Vigne S., Lamacchia C., Gabay C., Palmer G. (2012). The mouse interleukin (Il)33 gene is expressed in a cell type- and stimulus-dependent manner from two alternative promoters. J. Leukoc. Biol. 91, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga S., Hayakawa M., Tsuda H., Ohta S., Yanagisawa K. (2013). Presence of a novel exon 2E encoding a putative transmembrane protein in human IL-33 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 430, 969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C., Boerboom A. M., Baechle C., El-Bahay C., Kahl R., Degen G. H., Abel J. (2000). Regulation of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-2 induction by dioxin in rat hepatocytes: Possible c-Src-mediated pathway. Carcinogenesis 21, 2267–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C. F., Khan E. M., Leung P. S., Gershwin M. E., Chang W. L., Wu D., Haarmann-Stemmann T., Hoffmann A., Denison M. S. (2014). Cross-talk between aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the inflammatory response: A role for nuclear factor-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1866–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C. F., Li W., Wu D., Miller J. K., Sweeney C., Lazennec G., Fujisawa Y., Matsumura F. (2011). Interaction of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and NF-kappaB subunit RelB in breast cancer is associated with interleukin-8 overexpression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 512, 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C. F., Sciullo E., Li W., Wong P., Lazennec G., Matsumura F. (2007). RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 2941–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C. F., Sciullo E., Wong P., Kuzmicky P., Kado N., Matsumura F. (2005). Induction of proinflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein in human macrophage cell line U937 exposed to air pollution particulates. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 1536–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng C. M., Wang C. H., Lee M. J., He J. R., Huang H. Y., Chao M. W., Chung K. F., Kuo H. P. (2018). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by diesel exhaust particles mediates epithelium-derived cytokines expression in severe allergic asthma. Allergy 73, 2192–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M., Viera-Hutchins L., Garcia-Lloret M., Noval Rivas M., Wise P., McGhee S. A., Chatila Z. K., Daher N., Sioutas C., Chatila T. A. (2015). Vehicular exhaust particles promote allergic airway inflammation through an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-notch signaling cascade. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 441–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa R., Koike E., Win-Shwe T. T., Ichinose T., Takano H. (2016). Low-dose benzo[a]pyrene aggravates allergic airway inflammation in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 36, 1496–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zheng W., Jefcoate C. R. (2003). Ah receptor regulation of mouse Cyp1B1 is additionally modulated by a second novel complex that forms at two AhR response elements. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 192, 174–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]