A series of single-cluster nanostructures in different configurations can be achieved with up to 15 kinds of POM clusters.

Abstract

The assembly of atomically precise clusters into superstructures has tremendous potential in structural tunability and applications. Here, we report a series of single-cluster nanowires, single-cluster nanorings, and three-dimensional superstructure assemblies built by POM clusters. By stepwise tuning of interactions at molecular levels, the configurations can be varied from single-cluster nanowires to nanorings. A series of single-cluster nanostructures in different configurations can be achieved with up to 15 kinds of POM clusters. The single-cluster nanowires and three-dimensional superstructures perform enhanced activity in the catalytic and electrochemical sensing fields, illustrating the universal functionality of single-cluster assemblies.

INTRODUCTION

The self-assembly of nanoparticles is a growing interest in nanoscience due to their fundamental research standpoints (1) as well as unique properties (2–5). Inorganic nanocrystals are always regarded as rigid units owing to their lattice structure, and slight deformation in nanocrystals can result in high lattice stress, which restricts them from assembling into sophisticated superstructures. Inorganic clusters with atomic precision structures are a class of materials on the borderline between molecules and nanoparticles (6–8). One of their most distinct features is that their chemical or physical properties can be tuned at the single-atom level (9–12). Moreover, because of their extremely small size, which is close to sub–1 nm (13–15), their assembly may be determined by directional or nondirectional noncovalent bonds at molecular levels (16, 17) and might not follow the hard sphere model as compared with their inorganic nanocrystal counterparts (18–21). Thus, uncommon flexibility and versatility may be achieved in cluster assembly systems to obtain sophisticated superstructures by stepwise tuning of interactions at molecular levels. Affected by the variation of chemical bonds and surroundings, unexpected properties may emerge during the assembly process. However, caused by lack of connective mediates and the aggregation tendency of clusters, the assembly from single clusters into superstructures is still of great challenge.

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are subnanometer-sized clusters with a variety of structures (7) and widespread applications in photochemistry (22), catalysis (23), electronics (24), and electrochemistry (25). The oxygen-enriched surface of the POM cluster provides abundant coordination sites, and the solubility of POM clusters can be easily changed through the encapsulation of surface ligands (26), making them excellent candidates as building blocks for single-cluster assemblies. Kovalenko and co-workers (27) have achieved a family of superlattices assembled by POM clusters and inorganic nanocrystals. Recently, Wang and co-workers (28) reported the double-diamond cubosome superstructures built by heterocluster Janus dumbbells. However, the superstructure assemblies constructed by single POM clusters have not been reported yet.

Here, we report a series of single-cluster nanowires, single-cluster nanorings, and three-dimensional (3D) superstructure assemblies built by POM clusters. Schematics of the synthetic procedure and assembly process of the single-cluster nanostructures are demonstrated in Fig. 1. With lower pH values and more acetate replaced by acetic acid, the linkage between clusters will gradually change from the coordination bond of oxygen into the hydrogen bond of hydroxyl, which results in the change of coordination site at the molecular level and morphology transformation from a nanowire into a nanoring structure ultimately. By the substitution of a single metal atom in the POM cluster, a library of single-cluster nanostructures in different configurations can be achieved with 15 kinds of POM clusters, which reveals the controllability and general feasibility of the single-cluster assembly. The P2W17Mn nanowire displays excellent catalytic activity toward olefin epoxidation, and the 3D superstructures show enhanced sensitivity toward H2O2 detection compared with the unassembled structure, which illustrates the universal functionality and promising applicative prospects of single-cluster assemblies.

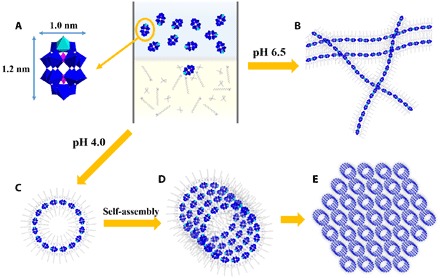

Fig. 1. Schematics of the synthesis and self-assembly process of single POM cluster nanostructures.

(A) Dawson-type POM cluster. (B) Single-cluster nanowires. (C) Single-cluster nanoring. (D) Nanocolumn constructed by nanorings. (E) 3D superstructure assembled by nanorings.

RESULTS

The Eu-substituted Wells-Dawson–type POM cluster, [α-2-P2W17EuO61]7−, is chosen as the typical building block, which is of subspheroidal shape that is 1.2 nm in the long axis direction and 1.0 nm in the short axis direction (Fig. 1A). By the two-phase approach synthesis (29), the single-cluster nanowires and nanorings (Fig. 1, B and C) are achieved in high yield (95% for nanowires and 80% for nanorings). The x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra testify to the constant valence of europium during the synthetic procedure (fig. S1A). The Fourier transform infrared spectra, 31P solid state nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (30), and elemental analysis results (fig. S2, A and B, and table S1) prove the intact POM anions in the product. The weight loss of nanowires and nanorings from the thermogravimetric analysis (fig. S2C) demonstrates that seven potassium ions have been completely substituted by quaternary ammonium cations. Hence, the chemical formula of the POM cluster is suggested to be (CTA)x(TBA)7-x[P2W17EuO61].

Ultrathin nanowires several hundred nanometers in length were achieved with neutral POM solution (Fig. 2A and fig. S3A). The single-cluster construction of the nanowire is observed by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Fig. 2B). The ultrahigh aspect ratio brings high surface energy, resulting in a high tendency to assemble and excellent flexibility. In concentrated solutions, the nanowires can form bundle structures (Fig. 2A) and cause the increase in viscosity of the solution, whereas in diluted solutions, random distortions are often observed in the nanowires (fig. S4A).

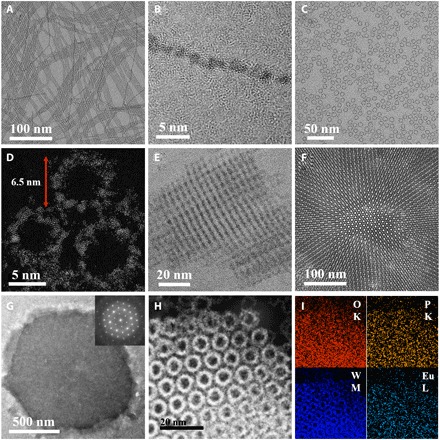

Fig. 2. Characterization of single-cluster nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures.

(A) Typical TEM image of a POM nanowire. (B) High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of a single nanowire. (C) Typical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of a POM nanoring. (D) High-resolution aberration-corrected TEM image of nanorings. (E) TEM image of a small-size superstructure from the side face. (F) TEM image from the top view of the superstructure. (G) Low-magnification TEM image of a 3D superstructure in large size and the corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) image. (H) Dark-field HRTEM image of the superstructure. (I) Energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) elemental mapping analysis of the superstructure.

As the acetic acid was introduced to the POM solution, the resulting nanowires curved and more closed rings were formed (fig. S4, B and C). The morphology transformation was accomplished when the pH was adjusted to 4.0 and stirring time was prolonged to 16 hours, resulting in uniform nanoring structures with a diameter of 6.5 nm (Fig. 2C and fig. S3B). By using high-resolution aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (TEM), single POM clusters of about 1 nm can be clearly observed (Fig. 2D), and no surface ligand is observed between the adjacent POM clusters. Combining the size of the nanoring and POM clusters, we propose that each nanoring is assembled by 16 POM clusters.

To figure out the interactions between adjacent POM clusters, the morphology evolution of the nanowire structure with different concentrations of potassium acetate (KAc) was carried out (fig. S5). The addition of KAc would contribute to the formation of nanowires; longer nanowires were obtained with higher KAc concentration. Desired nanowires with high respect ratio were achieved only with KAc more than twice the POM clusters in molar ratio. Similarly, no nanoring was observed by simply tuning the pH value in the absence of KAc. Hence, the acetic acid and acetate ion would serve as molecular linkers in the formation of nanowire and nanoring structures.

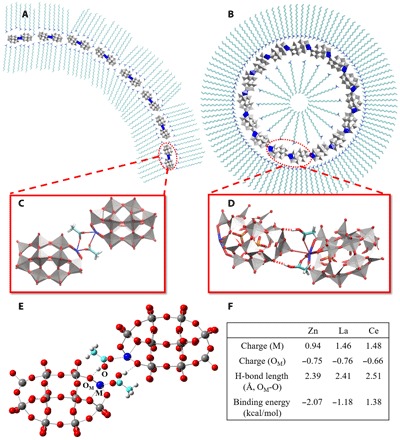

On the basis of potential intermolecular interactions between POM, KAc, and surfactants and the first principles calculations, we propose a molecular model for nanorings and nanowires, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, nanorings and nanowires adopt completely different assembly patterns. When the pH of the solution is higher than the pKa (4.5) of HAc, Ac− is the major species, and two oxygen atoms in the Ac− ligand bond respectively to two metal atoms in adjacent POM clusters and link them together via the coordination bonds, forming a POM dimer in a head-to-head configuration. In addition, positively charged surfactants like cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and tetrabutyl ammonium bromide (TBAB) further connect these negatively charged POM dimers together via electrostatic interactions, which are nondirectional and thereby account for the formation of flexible nanowires. When the pH of the solution is about 4.0, HAc is then the major species. The carbonyl oxygen in HAc still bonds to metal atom in one POM cluster via the coordination bond, while the hydroxyl oxygen in HAc interacts with a surface oxygen at the far end of the other POM through the hydrogen bond, leading to the formation of a POM dimer in the head-to-tail configuration. Both the coordination bond and hydrogen bond are directional, which result in a specific angle of ~22° between the POM clusters. When the head-to-tail linkage of POMs is cyclic, nanorings of 16 clusters form, which is consistent with the experimental observation. The surfactants bind to the exposed surface oxygens of POM and serve as scaffold in the circle, since the radii of the nanorings match the length of the CTAB molecules.

Fig. 3. Molecular model for POM single-cluster self-assembled nanostructures.

(A) Single-cluster nanowire. (B) Single-cluster nanoring. (C) Building block of a nanowire structure in which two POM clusters are linked head to head by Ac−. (D) Building block of a nanoring structure in which POM clusters are linked head to tail by HAc. (E) Single-cluster nanowire structure model at low pH in which POM clusters are linked by HAc in the head-to-head configuration. (F) Comparison of Mülliken charges on metal M and surface oxygen OM coordinating M in a single POM cluster P2W17M (M = Zn, La, Ce), as well as hydrogen bond length established between OM and hydroxyl oxygen of HAc (OM-O) and binding energy of HAc to single POM cluster calculated by the density functional theory. With the increasing acidity of M, OM becomes less negatively charged, and its ability to establish a hydrogen bond with HAc is diminished. Color code: M, blue; W, gray; O, red; and C, cyan.

It is worth mentioning that the nanorings can spontaneously self-assemble into 3D superstructures at room temperature. A well-ordered 3D superstructure with uniform pore features (6.5 nm in diameter) is observed from the top view, and a layered structure is exhibited from the side face (Fig. 2, E and F). Because of the different orientation stability of the superstructures, more top viewed ones are observed as they grow larger. There are gaps between neighboring nanorings and layers, and the interspaces between nanorings and layers are measured to be 3.5 and 3.8 nm, respectively. Energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) mapping analysis (Fig. 2, H and I) confirms the uniform distributions of tungsten, oxygen, phosphorus, and europium in the structure. The two projection images illustrate the simple hexagonal stacking manner of the superstructures, which is further confirmed by the fast Fourier transform (FFT) image (Fig. 2G). The superstructure can continually grow up to 1 μm if the assembly proceeds for weeks. The magnified image from the center of the superstructure (Fig. 4F) shows that the assembled nanorings are more uniform and compacted, illustrating that the arrangement of clusters inside the nanorings is adjustable during the assembly process.

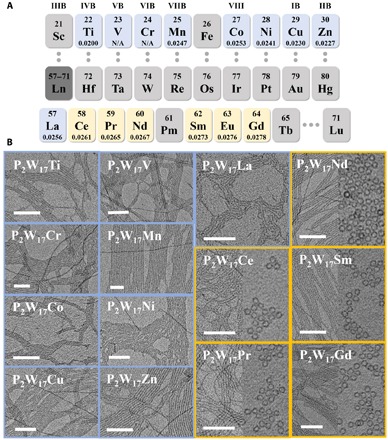

Fig. 4. Gallery of nanostructures constructed by P2W17M clusters.

(A) Map of elements that are able to form P2W17M cluster nanowires (highlighted in blue) and P2W17M cluster nanorings and superstructures (highlighted in orange). The charge-to-radii ratio of the element is listed at the bottom. (B) TEM images of P2W17M cluster nanowires and nanorings. Scale bar, 50 nm.

We further studied the formation process of 3D superstructures on the base of the intermediate shown in figs. S6 and S7. In the early stage of the assembly, nanorings first arrange layer by layer to form 1D nanocolumns (fig. S6), and the nanocolumns would then assemble into 3D superstructures. Simple cubic superstructures are also found in the formation process (fig. S7). These structures are commonly formed with small size in concentrated nanoring dispersions, indicating that the formation is under kinetic control. However, as the superstructure grows larger, the nanorings tend to get closely packed to minimize the surface energy, and the simple cubic superstructures will gradually transform into simple hexagonal ones and are rarely seen in the final product.

The assembly of nanoparticles into superstructures is mainly driven by solvent evaporation. The superstructures are usually unstable and disassemble into isolated building blocks after dilution due to the weak interactions between building blocks. In this work, the self-assembly of nanorings into 3D superstructures is driven by electrostatic attraction. The charge density per molecule is enormous compared with that of inorganic nanoparticles, and the assembly can effectively reduce surface energy, resulting in the spontaneous and irreversible assembly process. The 3D superstructures show high stability upon dilution and ultrasonication. The dilution of nanoring suspensions can only slow down but will not terminate or reverse the assembly process. As the structures are constructed by POM clusters (negatively charged) and quaternary ammonium cations (positively charged) driven by electrostatic attractions, they are sensitive to solvents. The product (including nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures) is unstable toward alcohols, ketones, and ethyl acetate but shows good stability toward alkane solvents (such as cyclohexane and hexane). The morphologies of all these POM cluster assemblies (including 3D superstructures) were well maintained after several washing and dispersing cycles. The above results further reveal the peculiar properties of the single-cluster assemblies.

The electrostatic attraction–driven ultrathin nanostructures display a strong tendency to assemble to reduce the surface energy, and the synergistic effects and specific properties may emerge during the assembly process. Revealed by the TEM images, POM clusters link together along their long axis, and the short axis is covered by surface ligands. Structure details of the single-cluster assemblies are investigated by controlling synthetic parameters seriatim.

To figure out the effect of alkyl chains of surfactants on nanowires, CTAB (C16) was replaced by octadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (OTAB, C18), tetradecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (TTAB, C14), and dodecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (DTAB, C12) in the synthesis. Similar nanostructures were feasible with OTAB and TTAB but unavailable with DTAB (figs. S8 and S9) or shorter-chained ones. Small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) profiles of the abovementioned nanowire structures demonstrate that the interspace between nanowires reduces as the alkyl chain length of surfactants decreases (fig. S8D). The values of distances further prove the double layer structure of the surface ligand between parallel nanowires. Moreover, the alkyl chains of surface ligands also influence the assembly rate of nanorings. The longer the surfactant chain, the better the deformability of the nanoring shells and the longer time they need to assemble into a well-ordered 3D superstructure. Nanorings with surfactant of OTAB, CTAB, and TTAB took 10, 3, and 1 day to assemble into 3D superstructures, respectively.

The influence of molecular linkers on the formation of nanostructures was then investigated by substituting the acetate (acetic acid) with formate (formic acid) and propionate (propionic acid) in the synthesis. Nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures of similar structural parameters could be achieved (fig. S10). Structural details were characterized by SAXS, and we found that as the alkyl chain of acids increased, intercluster distances expanded while the internanowire distance shrank slightly. The molecular linkers, sized much smaller than the POM cluster, locate in the center between adjacent clusters. As the alkyl chain grows, clusters are pushed away due to the steric hindrance effect, and the intercluster distance is expanded. Meanwhile, the covering surface ligands will invade the outer space generated, resulting in closer distance to clusters and a slight decrease in interspace between nanowires.

According to the molecular models, POM dimers in nanowire structures are linked via surfactant electrostatic attractions, which are weak and nondirectional. This type of linkage results in enlarged intermolecular distance as well as uncommon flexibility. High surface energy and excellent deformability impel nanowires to form bundles in concentrated solutions and become flexible in diluted suspensions. It is noteworthy that the single-cluster nanostructures not only provide flexibility but also bring elasticity to the system due to the noncovalent bond linkage. The average distances between adjacent clusters decrease during the assembly process and are measured to be 1.27, 1.25, and 1.22 nm in nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures, respectively, according to the SAXS results (fig. S11A). In the morphology transformation from nanowire to nanoring, the configuration of the POM dimer varies from head-to-head to head-to-tail with a specific angle, and the linkage between dimers changes from electrostatic attractions into coordinate bonds, leading to the shortening of intercluster distance and weaker flexibility of the nanoring structure. The assembly of nanorings into 3D superstructures further compresses the inter- and intrananoring distance, forming a more ordered and rigid shape of nanorings and closer intercluster distance. The shorter distance between POM clusters connected via coordination bonds can efficiently promote electron transfer and performs unpredictable properties in potential applications.

Owing to the extremely small size, the replacement of a single atom in the cluster can cause notable changes in properties. Thus, we try to substitute the europium atom in the POM cluster with other transition metals, of which the formula of the anionic POM clusters is [α-2-P2W17MO61]x− (x = 7 or 8, marked as P2W17M). Strikingly, similar nanostructures can be prepared with up to 15 kinds of POM clusters, but the configurations are not quite the same with each element. Figure 4 exhibits the overview of the involved transition elements and TEM images of the corresponding P2W17M nanostructures. The single-cluster nanowires can be achieved with 15 kinds of P2W17M clusters including metal elements M of transition metals (Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn; marked as Mtrans) and lanthanide (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, and Gd; marked as Ln), while the single-cluster nanorings and 3D superstructures can only be obtained with 6 P2W17Ln clusters including those of Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, and Gd. TEM images of the corresponding nanostructures composed of 14 kinds of P2W17M clusters are exhibited in Fig. 4B; enlarged images and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) results are shown in figs. S12 and S13. SAXS results (fig. S11, B and C) manifest the single-cluster constructions of the 14 kinds of P2W17M nanowires. In particular, for the P2W17V nanowires, vanadium was reduced to tetravalence with ascorbic acid in the synthesis (fig. S1B). It is worth mentioning that with the employment of the Dawson-type POM cluster with no transition metal atom, [α-2-P2W17O61]10−, ultrathin nanobelts 10 nm in width were achieved (fig. S14). No further curve or assembly was observed under similar reaction conditions.

To explain why only six P2W17Ln clusters self-assemble into nanorings, while the other nine P2W17M clusters always form nanowires irrespective of pH, we scrutinize the molecular model and building blocks of nanowires and nanorings. As mentioned above, the nanowire structures are built from the head-to-head configuration of POM dimers. To facilitate the formation of nanoring structures, the head-to-tail connection of the POM clusters is necessitated. This is feasible only if the pH of the solution is low and the hydrogen bond is formed between the hydroxyl oxygen of HAc and the surface oxygen of POM located far from the metal atom M. It is noteworthy that the ability of surface oxygens to accept hydrogen varies due to the influence of metal element M. The charge-to-radii ratio of all the metal elements involved, which can reflect the acidity of M, is listed in Fig. 4A, except for Cr and V due to their different coordination structure. In the nine P2W17M (M = Mtrans and La) clusters, the acidity of M is relatively weak, so oxygens coordinating M are more negatively charged (less than −0.7 atomic charge) and act as stronger hydrogen acceptors than oxygens far from M as illustrated in Fig. 3F. In the case of low pH, two P2W17M clusters can be linked head to head via HAc through a coordination bond and a hydrogen bond, giving rise to the nanowire structure (Fig. 3E and fig. S15), similar to the one with Ac− as linkers at high pH. In the six P2W17Ln (Ln = Ce-Gd) clusters, the acidity of M is further reinforced with decreasing ionic radii, and oxygens coordinating M become less negatively charged, so that binding of HAc to these oxygens is no longer favored in energy. Instead, forming a hydrogen bond between oxygens at the far end of P2W17Ln and the hydroxyl group in HAc is preferred, which facilitates the head-to-tail connection of POMs and the formation of nanoring structures.

To achieve the single-cluster assemblies, the key point is to create a tunable linkage between adjacent POM clusters. According to the molecular models, the substitutional metal atom in the cluster is essential for the connection since it provides a steady coordination site for the molecular intermediate. For the POM clusters with no metal substitution, the linkage between clusters can be nondirectional, leading to the formation of 2D and 3D nanostructures such as nanosheets and spheres. Therefore, the metal-substituted Keggin-type POM clusters ([PW11MO39]x−) are also potential candidates to assemble into similar structures. However, further investigations are needed to verify the configuration and establish a general synthetic method for the construction of single POM cluster assemblies.

POM clusters are potential candidates in the photochemical, catalytic, and electrochemical fields due to their remarkable redox property (31). In single-cluster assemblies, the various intercluster distances and connection types between clusters may lead to promotions in application potentials. Therefore, the catalytic and electrochemical sensing performances are tested with selected single-cluster nanostructures and are shown in Fig. 5.

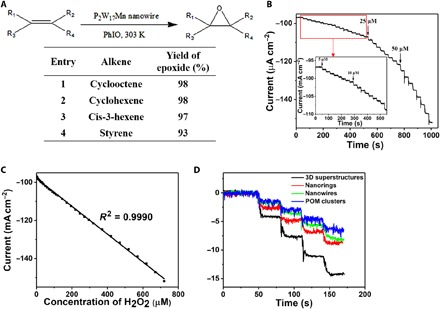

Fig. 5. Catalytic and electrochemical sensing performances of single-cluster nanostructures.

(A) Epoxidation of olefins with PhIO catalyzed by the P2W17Mn nanowires. Electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide (B to D). (B) Recorded amperometric response of a POM superstructure with the addition of hydrogen peroxide. (C) Corresponding calibration plot of steady-state currents against concentration of hydrogen peroxide. (D) Comparative amperometric response of 3D superstructures (black), nanorings (red), nanowires (green), and POM clusters (blue) with the addition of hydrogen peroxide (50 μM) at −0.78 V versus saturated calomel electrode.

Reactions of olefin epoxidation catalyzed by P2W17Mn nanowires are performed at room temperature. The catalytic epoxidation of cyclooctene can reach a yield of 98% within 2 hours, and high yields of 98, 97, and 93% are achieved with substrates of cyclohexene, cis-3-hexene, and styrene, respectively, under the same reaction conditions (Fig. 5A). The single-cluster nanowire structure shows notably improved catalytic activity of high yield in mild condition compared with the P2W17Mn precursor (table S2) and other POM catalysts (23, 32). Moreover, the P2W17Mn nanowires can be regarded as single-atom catalysts with uniform dispersion. Control experiments with (CTA)x(TBA)6-xP2W18O62, (CTA)x(TBA)10-xP2W17O61, and (CTA)x(TBA)7-xP2W17EuO61 as catalysts were also performed under the same conditions with reaction time prolonged to 24 hours. However, no epoxy product was detected, which indicated that the Mn atom played an essential role as the catalytic active center. By the substitution of the single metal atom in the POM cluster, more single-atom catalysts with diverse functionalities can be prepared, revealing the inestimable applicative potentials of the single-cluster nanostructures.

Electrochemical detection of H2O2 was carried out with different morphologies of P2W17Eu cluster assemblies. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the P2W17Eu superstructure/GCE (glassy carbon electrode) in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline in the absence of H2O2 and in the presence of 2 mM H2O2 are shown in fig. S16A. In contrast, the CV curves of P2W17Eu nanorings, nanowires, and clusters were tested in the same condition and shown in fig. S16 (B to D). To examine the sensitivity of the P2W17Eu superstructure toward H2O2, an electrode potential of −0.78 V (versus saturated calomel electrode) was used for the H2O2 detection. Figure 5B shows the amperometric response of the POM superstructure/GCE with successive step changes of H2O2 concentration. The detection limit of the P2W17Eu superstructure was 5 μM (S/N = 3), and the current response can reach steady state in less than 4 s. The calibration plot of the hydrogen peroxide sensor shown in Fig. 5C has a linear response range from 5 to 720 μM with a determination coefficient (R2) of 0.9990, as well as a sensitivity of 73.1 μA mM−1 cm−2. As presented in fig. S16E, there are no distinctive changes in current with the addition of methanol, glucose, uric acid, and ascorbic acid, which suggests that the P2W17Eu superstructure has high selectivity toward the detection of H2O2. In the control experiment, the amperometric responses of other POM nanostructures were carried out at the same electrode potential and shown in Fig. 5D. With the addition of the same amount of H2O2 (50 μM), the sensitivities of P2W17Eu clusters, nanowires, and nanorings were measured to be 31.6, 39.7, and 43.9 μA mM−1 cm−2, respectively. The P2W17Eu superstructure performs with notably enhanced sensitivity and lower noise in comparison with other unassembled nanostructures, which is due to the promotion of electron transfer in materials contributed by the shorter distance between adjacent clusters. These results illustrate the superiority and promising prospect of single-cluster assemblies as sensors and catalysts, and present the possibility of modifying the functionality of materials from the molecular level.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have achieved a series of single-cluster nanowires, single-cluster nanorings, and 3D superstructure assemblies built by POM clusters. By the substitution of a single metal atom in the POM cluster, a library of single-cluster nanostructures in different configurations can be achieved with 15 kinds of POM clusters, revealing the controllability and general feasibility of the single-cluster assembly. The configuration can be varied from single-cluster nanowires to nanorings by stepwise tuning at the molecular levels. Molecular models are established to clarify the interactions between clusters and the influence of substituted metal atom to the assembly. The P2W17Mn nanowire shows excellent catalytic activity toward olefin epoxidation, and the P2W17Eu 3D superstructures display enhanced sensitivity toward H2O2 detection, which illustrates the various functionalities of single-cluster assemblies. This work has pointed out new avenues to the “bottom up” fabrication of flexible nanostructures and superstructure assemblies with diverse functionalities and may enlighten the design of inorganic metamaterials from the molecular level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of P2W17Ln nanowires

K7P2W17LnO61 (330 mg) and 40 mg of KAc were dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water (pH 6.5) without further pH control. CTAB (79 mg) and 69 mg of TBAB were dissolved in 15 ml of chloroform. The organic phase was added dropwise into the POM solution under vigorous stirring. After 1 hour, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the organic phase was collected. The clear solution was evaporated under ambient condition. The product was obtained as powder (Ln = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd).

Synthesis of P2W17Mtrans nanowires

The synthetic methods for P2W17Mtrans nanowires were similar to those of P2W17Ln nanowires except for the pH values of the POM solution, which were K8P2W17TiO61 (pH 5.5), K7P2W17VO62 (pH 4.0), K7P2W17CrO61 (pH 10.0), K8P2W17MnO61 (pH 4.6), K8P2W17CoO61 (pH 4.0), K8P2W17NiO61 (pH 3.8), K8P2W17CuO61 (pH 4.0), and K8P2W17ZnO61 (pH 4.5). In particular, for the synthesis of P2W17V nanowires, 330 mg of K7P2W17VO62, 50 mg of KAc, and 40 mg of ascorbic acid were dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water to reduce V(V) into V(IV). Other synthetic parameters were the same with those of P2W17Ln nanowires.

Synthesis of P2W17Ln nanorings

K7P2W17LnO61 (330 mg) and 40 mg of KAc were dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water, and the pH was adjusted to 4.0 by acetic acid. CTAB (330 mg) and 69 mg of TBAB were dissolved in 30 ml of chloroform. The organic phase was added dropwise into the POM solution under vigorous stirring. After 16 hours, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, and the organic phase was collected. The clear solution was evaporated under ambient condition. The product was obtained as some powder (Ln = Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd).

Self-assembly of nanorings into 3D superstructures

Twenty milligrams of nanorings was dispersed in 10 ml of chloroform, and the solution was put into a sealed bottle for several days. The self-assembled superstructures were formed when the solution became turbid. The product was collected by centrifugation and dried under air.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0700101 and 2016YFA0202801) and the NSFC (21431003). Author contributions: Q.L. and P.H. conceived and designed the experiments. P.H. carried out the synthesis of the P2W17Eu nanowires, and Q.L. investigated the formation of the rest of the P2W17M nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures. Q.L. carried out the characterizations, electrochemical tests, and catalytic performance of the nanostructures. L.G. and B.N. performed the TEM imaging and analysis. H.Y. and D.W. designed the molecular models and performed the computer simulations. Q.L., X.W., H.Y., and D.W. cowrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaax1081/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. XPS spectrums of metal elements in nanowire structures.

Fig. S2. Characterizations of POM nanowire and nanoring structures.

Fig. S3. TEM images of single-cluster nanostructures in low magnification.

Fig. S4. The morphology transformation from nanowires into nanorings.

Fig. S5. TEM images of products synthesized with different concentrations of KAc.

Fig. S6. TEM images of nanocolumns assembled by nanorings.

Fig. S7. Typical TEM images of simple cubic (CTA)x(TBA)7-xP2W17EuO61 superstructures.

Fig. S8. TEM images of nanowires encapsulated by surfactants with different alkyl chain lengths.

Fig. S9. TEM images of nanorings and 3D superstructures encapsulated by surfactants with different alkyl chain lengths.

Fig. S10. TEM images of nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures with different alkyl chains of acids.

Fig. S11. SAXS results of P2W17M cluster nanostructures.

Fig. S12. TEM images and EDX results of nanowire structures constructed by P2W17M clusters.

Fig. S13. TEM images and EDX results of nanostructures constructed by P2W17Ln clusters.

Fig. S14. TEM images of (CTA)x(TBA)10-xP2W17O61 nanobelts.

Fig. S15. Optimized complex structure of HAc and the P2W17M (M = Zn, La, Ce) cluster.

Fig. S16. CV curves and selectivity test for the hydrogen peroxide detection.

Table S1. Elemental analysis results of nanowire and nanoring structures.

Table S2. Epoxidation of olefins with PhIO catalyzed by the P2W17Mn POM precursor.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Shevchenko E. V., Talapin D. V., Kotov N. A., O'Brien S., Murray C. B., Structural diversity in binary nanoparticle superlattices. Nature 439, 55–59 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redl F. X., Cho K.-S., Murray C. B., O'Brien S., Three-dimensional binary superlattices of magnetic nanocrystals and semiconductor quantum dots. Nature 423, 968–971 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross M. B., Ku J. C., Vaccarezza V. M., Schatz G. C., Mirkin C. A., Nanoscale form dictates mesoscale function in plasmonic DNA–nanoparticle superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 453–458 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang Y., Ye X., Chen J., Cai Y., Diaz R. E., Adzic R. R., Stach E. A., Murray C. B., Design of Pt–Pd binary superlattices exploiting shape effects and synergistic effects for oxygen reduction reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 42–45 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudiksen M. S., Lauhon L. J., Wang J., Smith D. C., Lieber C. M., Growth of nanowire superlattice structures for nanoscale photonics and electronics. Nature 415, 617–620 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin R., Zeng C., Zhou M., Chen Y., Atomically precise colloidal metal nanoclusters and nanoparticles: Fundamentals and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 116, 10346–10413 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long D.-L., Burkholder E., Cronin L., Polyoxometalate clusters, nanostructures and materials: From self assembly to designer materials and devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 105–121 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborty I., Pradeep T., Atomically precise clusters of noble metals: Emerging link between atoms and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 117, 8208–8271 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negishi Y., Nobusada K., Tsukuda T., Glutathione-protected gold clusters revisited: Bridging the gap between gold(I)−thiolate complexes and thiolate-protected gold nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5261–5270 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bootharaju M. S., Joshi C. P., Parida M. R., Mohammed O. F., Bakr O. M., Templated atom-precise galvanic synthesis and structure elucidation of a [Ag24Au(SR)18]− nanocluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 128, 934–938 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W., Chen S., Oxygen electroreduction catalyzed by gold nanoclusters: Strong core size effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 121, 4450–4453 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyo E. C., Vajda S., Catalysis by clusters with precise numbers of atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 577–588 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng C., Chen Y., Kirschbaum K., Appavoo K., Sfeir M. Y., Jin R., Structural patterns at all scales in a nonmetallic chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500045 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadzinsky P. D., Calero G., Ackerson C. J., Bushnell D. A., Kornberg R. D., Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1 Å resolution. Science 318, 430–433 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu S., Wang X., Ultrathin nanostructures: Smaller size with new phenomena. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 5577–5594 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou X.-S., Zhu G.-L., Ren L.-J., Huang Z.-H., Zhang R.-B., Ungar G., Yan L.-T., Wang W., Mesoscale graphene-like honeycomb mono- and multilayers constructed via self-assembly of coclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1805–1811 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grill L., Dyer M., Lafferentz L., Persson M., Peters M. V., Hecht S., Nano-architectures by covalent assembly of molecular building blocks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 687–691 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong A., Chen J., Vora P. M., Kikkawa J. M., Murray C. B., Binary nanocrystal superlattice membranes self-assembled at the liquid–air interface. Nature 466, 474–477 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henzie J., Grünwald M., Widmer-Cooper A., Geissler P. L., Yang P., Self-assembly of uniform polyhedral silver nanocrystals into densest packings and exotic superlattices. Nat. Mater. 11, 131–137 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Y., Nguyen T. D., Yang M., Lee B., Santos A., Podsiadlo P., Tang Z., Glotzer S. C., Kotov N. A., Self-assembly of self-limiting monodisperse supraparticles from polydisperse nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 580–587 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovalenko M. V., Scheele M., Talapin D. V., Colloidal nanocrystals with molecular metal chalcogenide surface ligands. Science 324, 1417–1420 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y., Zhang B., Wang Y., Yue L., Li W., Wu L., A photo-driven polyoxometalate complex shuttle and its homogeneous catalysis and heterogeneous separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14500–14503 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumann R., Dahan M., A ruthenium-substituted polyoxometalate as an inorganic dioxygenase for activation of molecular oxygen. Nature 388, 353–355 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell S. G., Streb C., Miras H. N., Boyd T., Long D.-L., Cronin L., Face-directed self-assembly of an electronically active Archimedean polyoxometalate architecture. Nat. Chem. 2, 308–312 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin Q., Tan J. M., Besson C., Geletii Y. V., Musaev D. G., Kuznetsov A. E., Luo Z., Hardcastle K. I., Hill C. L., A fast soluble carbon-free molecular water oxidation catalyst based on abundant metals. Science 328, 342–345 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H., Sun H., Qi W., Xu M., Wu L., Onionlike hybrid assemblies based on surfactant-encapsulated polyoxometalates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1300–1303 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodnarchuk M. I., Erni R., Krumeich F., Kovalenko M. V., Binary superlattices from colloidal nanocrystals and giant polyoxometalate clusters. Nano Lett. 13, 1699–1705 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H.-K., Ren L.-J., Wu H., Ma Y.-L., Richter S., Godehardt M., Kübel C., Wang W., Unraveling the self-assembly of hetero-cluster Janus dumbbells into hybrid cubosomes with internal double diamond structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 831–839 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan D., Jia X., Tang P., Hao J., Liu T., Self-patterning of hydrophobic materials into highly ordered honeycomb nanostructures at the air/water interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 119, 3406–3409 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W., Francesconi L. C., Polenova T., 31P Magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy for probing local environments in paramagnetic europium-substituted Wells−Dawson polyoxotungstates. Inorg. Chem. 46, 7861–7869 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long D.-L., Tsunashima R., Cronin L., Polyoxometalates: Building blocks for functional nanoscale systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1736–1758 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuwei X., Ning Z., Yu S., Kunlan L., Reaction-controlled phase-transfer catalysis for propylene epoxidation to propylene oxide. Science 292, 1139–1141 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Q., Howell R. C., Bartis J., Dankova M., Horrocks W. D., Rheingold A. L., Francesconi L. C., Lanthanide complexes of [α-2-P2W17O61]10-: Solid state and solution studies. Inorg. Chem. 41, 6112–6117 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu L.-Y., Shan Q.-J., Gong J., Lu R.-Q., Wang D.-R., Synthesis, properties and characterization of Dawson-type tungstophosphate heteropoly complexes substituted by titanium and peroxotitanium. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans., 4525–4528 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbessi M., Contant R., Thouvenot R., Herve G., Dawson type heteropolyanions. 1. Multinuclear (phosphorus-31, vanadium-51, tungsten-183) NMR structural investigations of octadeca(molybdotungstovanado)diphosphates .alpha.-1,2,3-[P2MM'2W15O62]n- (M, M' = Mo, V, W): Syntheses of new related compounds. Inorg. Chem. 30, 1695–1702 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rong C., Anson F. C., Simplified preparations and electrochemical behavior of two chromium-substituted heteropolytungstate anions. Inorg. Chem. 33, 1064–1070 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik S. A., Weakley T. J. R., Heteropolyanions containing two different heteroatoms. Part II. Anions related to 18-tungstodiphosphate. J. Chem. Soc. A, 2647–2650 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyon D. K., Miller W. K., Novet T., Domaille P. J., Evitt E., Johnson D. C., Finke R. G., Highly oxidation resistant inorganic-porphyrin analog polyoxometalate oxidation catalysts. 1. The synthesis and characterization of aqueous-soluble potassium salts of .alpha.2-P2W17O61(Mn+.cntdot.OH2)(n-10) and organic solvent soluble tetra-n-butylammonium salts of .alpha.2-P2W17O61(Mn+.cntdot.Br)(n-11) (M = Mn3+,Fe3+,Co2+,Ni2+,Cu2+). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 7209–7221 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartis J., Kunina Y., Blumenstein M., Francesconi L. C., Preparation and tungsten-183 NMR characterization of [α-1-P2W17O61]10-, [α-1-Zn(H2O)P2W17O61]8-, and [α-2-Zn(H2O)P2W17O61]8-. Inorg. Chem. 35, 1497–1501 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, D. Williams-Young, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, D. J. Fox, Gaussian 16 Rev. B.01, (Wallingford, CT, 2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaax1081/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. XPS spectrums of metal elements in nanowire structures.

Fig. S2. Characterizations of POM nanowire and nanoring structures.

Fig. S3. TEM images of single-cluster nanostructures in low magnification.

Fig. S4. The morphology transformation from nanowires into nanorings.

Fig. S5. TEM images of products synthesized with different concentrations of KAc.

Fig. S6. TEM images of nanocolumns assembled by nanorings.

Fig. S7. Typical TEM images of simple cubic (CTA)x(TBA)7-xP2W17EuO61 superstructures.

Fig. S8. TEM images of nanowires encapsulated by surfactants with different alkyl chain lengths.

Fig. S9. TEM images of nanorings and 3D superstructures encapsulated by surfactants with different alkyl chain lengths.

Fig. S10. TEM images of nanowires, nanorings, and 3D superstructures with different alkyl chains of acids.

Fig. S11. SAXS results of P2W17M cluster nanostructures.

Fig. S12. TEM images and EDX results of nanowire structures constructed by P2W17M clusters.

Fig. S13. TEM images and EDX results of nanostructures constructed by P2W17Ln clusters.

Fig. S14. TEM images of (CTA)x(TBA)10-xP2W17O61 nanobelts.

Fig. S15. Optimized complex structure of HAc and the P2W17M (M = Zn, La, Ce) cluster.

Fig. S16. CV curves and selectivity test for the hydrogen peroxide detection.

Table S1. Elemental analysis results of nanowire and nanoring structures.

Table S2. Epoxidation of olefins with PhIO catalyzed by the P2W17Mn POM precursor.