Abstract

Background.

Longevity gene klotho (KL) is associated with age-related phenotypes but has not been evaluated against a direct human biomarker of cellular aging. We examined KL and psychiatric stress, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is thought to potentiate accelerated aging, in association with biomarkers of cellular aging.

Methods.

The sample comprised 309 white, non-Hispanic genotyped veterans with measures of epigenetic age (DNA methylation age), telomere length (n = 252), inflammation (C-reactive protein), psychiatric symptoms, metabolic function, and white matter neural integrity (diffusion tensor imaging; n = 185). Genotyping and DNA methylation were obtained on epi/genome-wide beadchips.

Results.

In gene by environment analyses, two KL variants (rs9315202 and rs9563121) interacted with PTSD severity (peak corrected p = .044) and sleep disturbance (peak corrected p = .034) to predict advanced epigenetic age. KL variant, rs398655, interacted with self-reported pain in association with slowed epigenetic age (corrected p = .048). A well-studied protective variant, rs9527025, was associated with slowed epigenetic age (p = .046). The peak PTSD interaction term (with rs9315202) also predicted C-reactive protein (p = .049), and white matter microstructural integrity in two tracts (corrected ps = .005 - .035). This SNP evidenced a main effect with an index of metabolic syndrome severity (p = .015). Effects were generally accentuated in older subjects.

Conclusions.

Rs9315202 predicted multiple biomarkers of cellular aging such that psychiatric stress was more strongly associated with cellular aging in those with the minor allele. KL genotype may contribute to a synchronized pathological aging response to stress and could be a therapeutic target to alter the pace of cellular aging.

1. Introduction

One of the many dynamic tales in Greek mythology is that of the goddess Clotho, one of three sisters born to Zeus and Themis who collectively determined human fate. Clotho, the youngest of the sisters, spun the thread of human life and in so doing, determined an individual’s birth, death, and lifespan (Hamilton, 2011). Clotho’s namesake gene, klotho (KL), and the protein it encodes were so named for their associations with aging and longevity (Kuro-o et al., 1997; Kurosu et al., 2005; Semba et al., 2011; Di Bona et al., 2014). In mice, kl homozygosity is associated with dramatically shortened lifespan (Kurosu et al., 2005) and premature onset of old age-related phenotypes, including motor disturbance, osteoporosis, skin thinning, and artery calcification (Kuro-o et al., 1997). Reduced klotho levels in mice were also associated with shortened telomeres and reductions in stem cell telomerase activity, both biomarkers of cellular aging (Ullah et al., 2018). In contrast, kl overexpression in mice is associated with improved survival (Dubal et al., 2014). In humans, a KL haplotype referred to as KL-VS, and two variants in the haplotype in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) that impact transcription (rs9536314, rs9527025), increase secreted klotho and are associated with longevity (Arking et al., 2002, 2005; Revelas et al., 2018). KL and the protein it encodes have also been linked to many age-related biomarkers and health conditions in humans, including numerous cardiovascular and cardiometabolic problems (Arking et al., 2003, 2005; Majumdar & Christopher, 2011; Semba et al., 2011; Majumdar, Nagaraja & Christopher, 2010), and particularly, with premature onset of these conditions (Arking et al., 2003, Majumdar et al., 2010). Associations with kidney function (Drew et al., 2017), frailty (Shardell et al., 2017), and functional disability (Crasto et al., 2012) have also been reported. Klotho protein levels are negatively related to psychological stress and depression (Prather et al., 2015), suggesting the relevance of the gene to a wide array of adverse health conditions.

There is also considerable evidence of effects of klotho on neural integrity and cognition. In young and aged mice, kl genotype was associated with spatial learning and memory performance and enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation via NMDA receptor signaling (Dubal et al., 2014). Overexpression of kl in transgenic mice carrying early onset Alzheimer’s disease risk mutations protected against the development of neurodegenerative phenotypes via increased NMDA receptor postsynaptic density and long-term potentiation in the hippocampus, and was related to enhanced survival (Dubal et al., 2015). Further, kl knockout mice showed degeneration in pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and in Purkinje cells (Shiozaki et al., 2008), possibly accounting for the motor decline observed in kl models of advanced aging (Kuro-o et al., 1997). In humans, KL-VS was associated with higher scores on composite measures of cognition in three cohorts of varying ages (Dubal et al., 2014), with larger cortical volume in right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), and indirectly linked to improved working memory and executive functions via morphology of this region (Yokoyama et al., 2015). Plasma klotho was associated with better cognitive performance and less cognitive decline over time (Shardell et al., 2015) while Alzheimer’s disease evidenced associations with reduced cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) klotho (Semba et al., 2014). Serum klotho has also been associated with greater grey matter volume in right DLPFC and right middle temporal gyrus (Yokoyama et al., 2017), with functional connectivity between right DLPFC and other prefrontal regions, and within regions of the cortex that comprise the default mode network (Yokoyama et al., 2017).

There is also evidence of KL effects on white matter. In mice, kl knockout was associated with reduced neuronal myelination of the optic nerve and corpus callosum via loss of oligodendrocytes (Chen et al., 2013). Lowered kl expression was found in the white matter of aged Rhesus monkeys (Duce et al., 2008), including in DLPFC (King et al., 2012), possibly as a function of age-related increases in kl promotor region methylation (King et al., 2012). In humans, KL expression in white blood cells (Karami et al., 2017) and klotho concentrations in CSF (Aleagha et al., 2015) are decreased in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, a demyelinating disease.

Though the foregoing suggests that klotho is associated with numerous clinical markers of aging and longevity, no study to date has examined the association of the gene with a direct biomarker of accelerated cellular aging in humans. DNA methylation age (“epigenetic age”) is a strong index (r > .95) of chronological age (Horvath, 2013) that far exceeds the strength of the association between telomeres and age (r ≈ −.30; Müezzinler et al., 2013), making it ideal for an evaluation of the association between KL and accelerated cellular aging. Conceptually, accelerated epigenetic age occurs when estimated DNAm age exceeds chronological age. This is commonly operationally defined as the residuals from an equation in which chronological age is regressed out from epigenetic age. Recent evidence suggests that advanced DNAm age predicts shortened time till death (Chen et al., 2016), inflammatory markers (Quach et al., 2017; Irvin et al., 2018), and diminished neurocognitive integrity (Levine et al., 2015). Pathogenic factors such as obesity (Nevalainen et al., 2017) and tobacco use (Gao et al., 2016) are cross-sectionally predictive of advanced DNAm age. PTSD symptoms (Wolf et al., 2018, 2018, 2018; Wolf, Logue et al., 2016), childhood trauma exposure (Wolf, Maniates et al., 2018; Jovanovic et al, 2017), life stress (Zannas et al., 2015), racial discrimination in the context of poor family support (Brody et al., 2016), alcohol misuse (Wolf, Logue, Morrison et al., 2018), insomnia (Carroll et al., 2016), and depression (Han et al., 2018) have also been associated with various metrics of advanced DNAm age in blood-based studies. Depression was further implicated in one postmortem prefrontal tissue study (Han et al., 2018). Collectively, these studies suggest that many different types of psychiatric stress predispose to accelerated epigenetic aging, however, it is important to note that some studies have reported no significant association at all (e.g., with PTSD, Zannas et al., 2015) and at least one study reported associations between PTSD and decreased epigenetic age (though without comparison to chronological age; Boks et al., 2015). Beyond environmental risk factors, advanced DNAm age is thought to be partially influenced by genotype (Horvath, 2013).

The primary aims of this study were to evaluate: (a) if common genetic variants in KL are associated with advanced DNAm age and other biomarkers of cellular aging; and (b) if KL variants strengthen the association between psychiatric stress and accelerated DNAm age in blood (and other biomarkers of cellular aging; i.e., G X E). Given that our sample was enriched for PTSD, our analyses focused on PTSD symptoms as the primary stress marker. However, because it is unlikely that the impact of psychiatric stress on accelerated cellular aging would be unique to PTSD (Wolf, Logue, Morrison et al., 2018), we also separately examined genotype interactions with other stress-related conditions, including major depressive disorder, alcohol-use disorders, pain, and sleep disturbance. These conditions tend to be highly comorbid (Slade & Watson, 2006; Wulff et al., 2010; Plana-Ripoll et al., 2019) and given prior associations between these conditions and markers of cellular aging and inflammation (McEwen & Kalia, 2010; Epel & Prather, 2018; Glaus et al., 2018; Michopoulos et al., 2017), they are likely to share common stress-related pathophysiological features. The primary hypothesis of this study was that SNPs in KL would be associated with advanced DNAm age and would moderate associations between measures of psychiatric stress and advanced DNAm age (and other markers of cellular aging) in blood. Given that the effects of KL and its protein on longevity and age-related phenotypes may vary as a function of age (Arking et al., 2003; Majumdar et al., 2010), we also evaluated whether associations between KL and stress on advanced cellular age varied as a function of chronological age.

We examined several indicators of cellular aging (in addition to epigenetic age), each of which has shown associations with klotho, stress, and/or with normal and accelerated aging, namely: telomere length; C-reactive protein (CRP); metabolic dysfunction; and white matter microstructural integrity (visualized with Diffusion Tensor Imaging; DTI). Telomere length tends to have a modest association with age, but is important for understanding age-related disease because critically short telomeres lead to cellular senescence, inflammation, and oxidative stress (Campisi & di Fagagna, 2007). There is evidence that numerous psychiatric and environmental stressors (including PTSD) are associated with telomere length (Lindqvist et al., 2015), making this biomarker relevant to the study of KL and psychiatric stress. CRP is a marker of “inflammaging,” which is an age-associated condition defined by chronic inflammation, and a contributor to cellular aging (Baylis et al., 2013). CRP is also highly sensitive to stress and is associated with PTSD, other psychiatric conditions (Michopoulos et al., 2015; Dubois et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2018), and accelerated epigenetic age (Quach et al., 2017). Metabolic pathology was evaluated because it is an index of altered homeostasis observed in cellular aging (López-Otin et al., 2016), and has been associated with cellular aging over time, as measured by mitochondrial DNA copy number (Révész et al., 2018). Moreover, critical components of metabolic pathology (i.e., obesity) have been associated with advanced epigenetic age (Quach et al., 2017) and we have previously shown that metabolic syndrome is associated both cross-sectionally and longitudinally with PTSD (Wolf, Bovin et al., 2016). We included white matter microstructural integrity in our analyses because this measure shows particular sensitivity to age-related decline (Salat et al., 2005) and was previously associated with advanced epigenetic age (Wolf, Logue et al., 2016). Based on the foregoing, we hypothesized that KL genotype, alone and in the presence of psychiatric stress, would be associated with alterations in these biomarkers of cellular aging.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in the full cohort were 532 veterans (90.8% male) who were deployed to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and participated in a study of the psychological, neurocognitive, and health correlates of deployment-related stressors (The Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders, TRACTS; McGlinchey et al., 2017). To avoid possible genetic population-stratification confounds, the analytic sample was limited to the white, non-Hispanic subsample with complete data on the variables of interest (n = 309 for DNAm age, n = 252 for telomeres, n = 185 for neuroimaging), with ancestry determined by genotypes (Logue et al., 2015; demographics, Tables 1, S1). Participants underwent a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, physiological assessment, blood draw for genetic and metabolic testing, and a series of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 309)

| Variable | M (SD) | % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 93.5 (289) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 100 (309) | |

| Age | 32.04 (8.40) | |

| PTSD dx | 64.1 (198) | |

| PTSD severity | 52.45 (29.62) | |

| Pain severity | 29.55 (25.80) | |

| Sleep disturbance | 10.06 (4.90) | |

| MDD dx | 25.6 (79) | |

| Alcohol-use dx | 6.5 (20) |

Note. The full sample was of mixed ancestry but due to concerns relating to population stratification, only the largest ancestry subsample (white, non-Hispanic) was analyzed, as determined based on genotype in concert with self-reported race and ethnicity. Veterans who did not have neuroimaging data were, on average about 2.76 years older than those with this data (p = .004), but there were no differences in sex or PTSD diagnostic status. Age was controlled for in neuroimaging analyses. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; dx = diagnosis.

2.2. Measures

PTSD was assessed by psychologists using the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995). Major depression and alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 1997). The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (Kubany et al., 2000), a self-report index of 21 potentially traumatic experiences, was administered to assess trauma across the lifespan. Self-reported pain within the past month and global sleep quality were measured with the short form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ; Melzack, 1987) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al., 1989), respectively.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Metabolic, Inflammatory, and Biophysical Measures.

Fasting overnight blood samples were obtained by a phlebotomist and samples processed the same day in a clinical laboratory (Wolf, Sadeh et al., 2016). HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c), insulin and CRP (Miller et al., 2018, see Supplementary Materials) were assayed. One subject was excluded from CRP-related analyses because the obtained CRP value was more than 12 SDs above the sample mean. Height, weight, waist-to-hip ratio and two seated blood pressure readings were taken, separated by 1-minute (Table S2).

2.3.2. MRI.

Scans were collected with a 12-channel head coil on a 3-Tesla Siemens Trio MRI scanner. DTI data were analyzed with a combination of software packages including the FreeSurfer image analysis suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) and The Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain FSL software package (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (Smith et al. 2006) was used to align FA images to standard space and a threshold of 0.2 was used to restrict the skeleton to only white matter (Supplementary Materials).

2.3.3. DNA, DNAm, and Related Statistical Procedures.

DNA was extracted from blood samples. Genotype calls were based on the Illumina HumanOmni2.5–8 array and DNAm on the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC array (Supplementary Materials). We examined all SNPs on the chip that passed quality controls with at least 5% minor allele frequency (MAF), < 5% missing calls, and within 5,000 base pair of the KL gene (per the GRCh37/hg19 build; Supplementary Materials). Ancestry-based principal components (PCs) were generated from common SNPs (Supplementary Materials). Proportional white blood cell (WBC) types, including CD8-T and CD4-T cells, natural killer cells, b-cells, and monocytes, were calculated from the methylation data (Aryee et al., 2014; Fortin et al., 2017) and were simultaneously included as covariates in analyses examining epigenetic age and telomeres (Supplementary Materials). DNAm age (Horvath, 2013) was estimated using the R script version of the Horvath algorithm based on 335 DNAm probes (Supplementary Materials).

2.3.4. Telomere Length Estimates.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR; Cawthon, 2002) was used to determine average relative telomere length from the same leukocytes the DNA was extracted from. Quantification is based on the copy-number ratio between telomeric repeats and a single-copy (36B4) reference gene (T/S Ratio, -dCt). The average telomere length across all chromosomes in a cell population is represented by the T/S ratio, which was calculated by subtracting the average 36B4 threshold cycle (Ct) value from the average telomere Ct value for each subject (Supplementary Materials). Estimates were obtained in two batches and batch number and estimated WBCs from the DNAm data were included as a covariate in these analyses. These data were available for a subset of n = 252 subjects.

2.4. Data Analysis

We first computed an index of advanced epigenetic age by regressing DNAm age on chronological age and saving the residuals (“DNAm age residuals”). Advanced DNAm age is captured by positive residuals. We individually evaluated the 43 KL SNPs with at least 5% MAF (MAF; Table 2), alone and in interaction with PTSD severity, as predictors of DNAm age residuals, controlling for the top two ancestry PCs, sex, and estimated WBCs in the first step of the regression. The multiple-testing correction across SNPs and interaction terms in this study was achieved via Monte Carlo null simulation with 10,000 replicates. This simulation permutes the genotypes across subjects to create a simulated minimum p-value distribution which is used to generate corrected p-value estimates for the main effect of SNPs and then is utilized again to generate corrected p-values for the interaction terms. This procedure, which we have utilized previously (e.g., Miller et al., 2015, 2018), yields an experiment-wide corrected p-value that takes into account the correlational structure of SNPs, similar to the Max[T] permutation procedure in PLINK, as well as the correlation structure of dependent variables. This approach avoids the overly conservative false discovery rate and Bonferroni correction methods in situations in which test statistics are correlated. The same approach was followed to separately examine SNP interactions with other markers of psychiatric stress, controlling for PTSD severity. Secondary regressions were conducted in age-stratified groups split at the median (30 years). Additional follow-up analyses (Supplementary Materials) further controlled for potential confounds, including other diagnoses, traumatic brain injury, health conditions, and medications (Table S1).

Table 2.

Minor Allele Frequencies (MAF) and Base Pair Location of KL Variants

| SNP | Base Pair | Minor Allele | MAF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs75535087 | 33585338 | A | 9.90 |

| rs397703 | 33587329 | G | 18.69 |

| rs398655 | 33587652 | C | 40.71 |

| rs562020 | 33592070 | A | 33.65 |

| rs495392 | 33592193 | A | 26.12 |

| rs73176817 | 33592313 | G | 8.81 |

| rs425686 | 33592527 | G | 33.81 |

| rs568461 | 33592755 | G | 33.87 |

| rs575536 | 33592777 | A | 25.24 |

| rs2283368 | 33593270 | G | 10.00 |

| rs499091 | 33594156 | G | 41.05 |

| rs211234 | 33595128 | A | 40.19 |

| rs526906 | 33598987 | A | 15.97 |

| rs525014 | 33599198 | A | 33.01 |

| rs9526952 | 33600815 | A | 7.03 |

| rs12867024 | 33604321 | G | 9.74 |

| rs563925 | 33606057 | A | 27.16 |

| rs508394 | 33606669 | A | 39.94 |

| rs9536234 | 33607814 | A | 16.99 |

| rs7982726 | 33610711 | G | 16.93 |

| rs569546 | 33611114 | G | 15.87 |

| rs8000084 | 33611193 | A | 16.67 |

| rs685417 | 33613132 | G | 32.75 |

| rs9526998 | 33613579 | A | 16.83 |

| rs1334928 | 33615948 | C | 40.42 |

| rs2516571 | 33616067 | G | 15.34 |

| rs2320762 | 33617174 | C | 34.35 |

| rs1888057 | 33622695 | A | 24.76 |

| rs657049 | 33622817 | G | 32.42 |

| rs497050 | 33622882 | G | 32.42 |

| rs2283370 | 33622962 | A | 15.18 |

| rs2249358 | 33623164 | G | 32.43 |

| rs683907 | 33624175 | G | 41.69 |

| rs9563121 | 33624506 | A | 25.72 |

| rs7987923 | 33625012 | A | 17.47 |

| rs9527024 | 33627693 | A | 17.41 |

| rs9527025 | 33628193 | C | 17.15 |

| rs9527026 | 33628239 | A | 17.41 |

| rs564481 | 33634983 | A | 42.01 |

| rs648202 | 33635463 | A | 14.54 |

| rs9563124 | 33637539 | G | 35.78 |

| rs9315202 | 33642016 | A | 25.64 |

| rs677332 | 33643904 | G | 41.99 |

Note. We only examined SNPs on the array with minor allele frequencies of 5% or greater. Base pair location is derived from the GRCh37/hg19 build. KL is located on chromosome 13. MAF = minor allele frequency; KL = klotho; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

Regression was also applied to examine the peak SNP1 in interaction with PTSD (from analyses predicting DNAm age residuals) in association with telomere length estimates, metabolic pathology, and log-transformed CRP values (Miller et al., 2018); these analyses controlled for the aforementioned covariates and additionally controlled for both age and DNAm age residuals.2 Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was measured via factor scores derived from a confirmatory factor analysis of raw metabolic parameters (Wolf, Sadeh et al., 2016; Supplementary Materials). There was no multiple testing correction for analyses predicting MetS factor scores, CRP, or telomere length, because these analyses reflect distinct hypotheses which were each tested once (i.e., using the peak SNP that was identified in the prior multiple-testing corrected analyses focused on epigenetic aging). We also evaluated four bilateral white matter tracts, based on proximity to regions previously associated with klotho: the cingulum bundle/cingulate, the cingulum bundle/hippocampus, the fornix/stria terminalis, and the superior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Dubal et al., 2014; Yokoyama et al., 2015). Given that this family of tests evaluated multiple regions of interest, the same permutation-based correction for multiple testing described above was employed to account for the eight dependent variables and their correlational structure (Miller et al., 2015). Separate analyses were conducted for fractional anisotropy (FA), radial diffusivity (RD), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and axial diffusivity (AxD) DTI parameters. For all analyses, unstandardized coefficients are reported in tables and standardized (std) coefficient estimates are presented in the text. All analyses involving multiple testing correction were conducted in R v 3.4.1, latent variable analyses were conducted in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017), and all other analyses were conducted in SPSS v. 25.

3. Results

3.1. KL X PTSD Severity in Association with DNAm Age Residuals

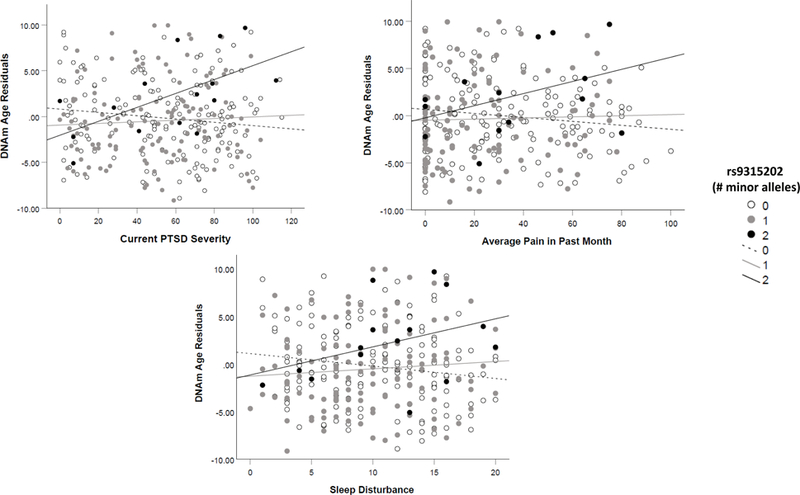

Chronological age and DNAm age were highly correlated (r = .85, p < .001; Figure S1). The KL-VS protective variant, rs9527025, was associated with slowed DNAm age (std β = −.11, p = .046; Table S3); in the age-stratified analyses, this was only significant in the older subsample (std β = −.21, p = .007). There were no corrected significant SNP main effects (Table S3). There were two corrected significant SNP X PTSD severity effects (rs9563121 and rs9315202, which are in perfect LD: std βs = .30 and .30; corrected ps = .049 and .044, respectively; Tables 3, S3). The peak-PTSD interaction term (with rs9315202) was decomposed by examining the association between PTSD severity and DNAm age residuals in each genotype group separately. The relationship between PTSD severity and DNAm age residuals was strongest for those with two copies of the minor allele (AA genotype) of rs9315202 (n = 22; p = .018; Figure 1), while it was not significantly related with DNAm age residuals in those with zero (GG) or one (AG) copy of the minor allele (ps = .08 and .53, respectively). The pattern of results was unchanged when the aforementioned potential confounds were evaluated (Supplementary Materials; interaction term ps = .001 to .004 with potential confounds in the model). Splitting the sample at the median age revealed that the interaction was significant in older (n = 154, p = .026), but not younger (n = 154, p = .36) veterans.

Table 3.

Regression Results from Models with Corrected Significant Interactive Effects of KL and Psychiatric Stress on DNAm Age Residuals (n = 309)

| Variable | β | SE | p | p corrected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Covariates | ||||

| Intercept | −.205 | 1.998 | .918 | N/A |

| Sex | .503 | 0.959 | .600 | N/A |

| PC1 | 2.004 | 4.612 | .664 | N/A |

| PC2 | −6.559 | 4.660 | .160 | N/A |

| PTSD severity | −6.026 × 10−4 | 0.008 | .939 | N/A |

| Sleep disturbancea | −.002 | .069 | .981 | N/A |

| Painb | −.003 | .011 | .767 | N/A |

| CD4-T | −4.080 | 5.332 | .445 | N/A |

| CD8-T | −3.350 | 6.431 | .603 | N/A |

| NK | 4.550 | 8.016 | .570 | N/A |

| Monocytes | 21.867 | 10.217 | .033 | N/A |

| B-cell | −45.409 | 11.352 | < .001 | N/A |

| 2: SNP | ||||

| rs9563121c(PTSD model) | .589 | .399 | .141 | .858 |

| rs9315202(PTSD model) | .372 | .396 | .348 | .995 |

| rs398655c(pain model) | .624 | .345 | .072 | .635 |

| 3: Interactions | ||||

| rs9563121(w/PTSD) | .039 | .013 | .003 | .049 |

| rs9315202(w/PTSD) | .040 | .013 | .002 | .044 |

| rs9563121(w/sleep) | .236 | .080 | .004 | .032 |

| rs9315202(w/sleep) | .232 | .079 | .004 | .033 |

| rs398655(w/pain) | −.038 | .013 | .003 | .048 |

Note. Only results from models in which an interaction effect was significant after correction for multiple testing across all SNPs are shown. Separate models were run for interactions with PTSD, sleep disturbance, and pain, but are included in a single table for efficiency. Full model results for all SNPs and all models are listed in Tables S3-S5. Coefficients in the table are unstandardized; standardized results are provided in the text. KL = klotho; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; DNAm = DNA methylation; PC = principal component; CD = cluster of differentiation; NK = natural killer; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; w = with.

Only included as a main effect in models focused on sleep disturbance in interaction with KL SNPs.

Only included as a main effect in models focused on pain in interaction with KL SNPs.

Each SNP was evaluated in a separate regression, but are shown here in one step for efficiency.

Figure 1.

shows the consistent pattern of association between PTSD symptom severity (Panel A, top left), pain severity in the past month (Panel B, top right), and sleep disturbance (Panel C, bottom) with DNAm age residuals as a function of rs9315202 genotype. Those with two copies of the minor allele (AA) at this locus evidenced a stronger association between each measure of psychiatric stress and DNAm age residuals.

3.2. KL X Other Markers of Psychiatric Stress in Association with DNAm Age Residuals

The interaction between rs398655 and self-reported pain was associated with DNAm age residuals (std β = −.35, corrected p = .048; Table 3) and rs9315202 evidenced a nominally significant interaction (std β = .24, p = .015; Table S4), with both interactions relatively stronger in the older cohort. Sleep disturbance interacted with rs9315202 (and with rs9563121, the SNP in high LD) to predict DNAm age residuals (std β = .40, corrected p = .033; Tables 3, S5, Figure 1), with effects significant in the older but not the younger cohort (p = .038 vs. .089). There were no corrected significant interaction effects with other markers of psychiatric stress.

3.3. rs9315202 X PTSD Severity in Association with Telomere Length, MetS, and CRP

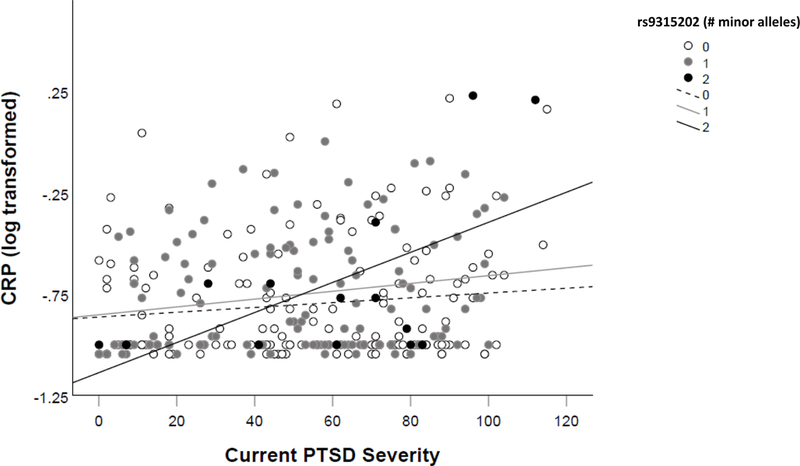

Following the gene-based analyses, we selected the peak SNP (rs9315202) X PTSD severity term for further analysis with additional biomarkers of cellular aging. There were no main or interactive effects of this SNP or PTSD severity in analyses evaluating telomere length (Table 4). This held when we examined the age-based subgroups (all interaction p > .20) and when we conducted analyses in each telomere batch separately (all interaction p > .15).3 The rs9315202 X PTSD severity term did not predict MetS factor scores, but the SNP evidenced a significant main effect (std β = .10, p = .015; Table 4). Follow-up analyses revealed that this effect was largely accounted for by the association with the lower-order Lipids/Obesity factor scores (std β = .13, p = .008; see Supplementary Materials for results pertaining to other MetS factors). 4 Splitting the sample by the median age showed that the effect on MetS was significant in the older cohort (p = .019) but not the younger one (p = .404). The rs9315202 X PTSD severity term predicted log-transformed CRP (std β = .25, p = .049; Table 4, Figure 2). The association between PTSD and increased CRP was significant among those with AA and AG genotypes (p = .018 and .033, respectively), but not those with GG (p = .12). Age-stratified analyses revealed an effect driven by the older subgroup (p = .035) that was not significant among the younger group (p = .76). The pattern of results was not substantially changed by inclusion of potential confounds (see Supplementary Materials for details; all SNP main effects for MetS p ≤ .018 and all SNP interaction effects for CRP p = .036 - .075 with potential confounds in the model; all std β within .02 of models without these confounds included).

Table 4.

Results of Regressions Evaluating Peak KL SNP in Interaction with PTSD Severity on Metabolic, Inflammatory and Telomere Length Parameters

| MetS Factor Scores |

Log CRP |

Telomere Length |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | ||

| 1: Covariates | |||||||||||

| Intercept | −.019 | .010 | .062 | −.993 | .106 | <.001 | .319 | .107 | .003 | ||

| Age | .003 | <.001 | <.001 | .000 | .002 | .885 | −.004 | .001 | .003 | ||

| Sex | −.084 | .007 | <.001 | .104 | .070 | .135 | .110 | .049 | .024 | ||

| PC1 | −.059 | .033 | .074 | .124 | .337 | .713 | .224 | .217 | .301 | ||

| PC2 | .024 | .033 | .477 | .279 | .346 | .422 | −.010 | .211 | .961 | ||

| PTSD severity | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .002 | .001 | .002 | 2.466 X 10−5 | <.001 | .945 | ||

| DNAm age res | .001 | <.001 | .068 | −.001 | .004 | .882 | −.001 | .003 | .686 | ||

| TL Batch | .480 | .027 | <.001 | ||||||||

| CD8-T | .228 | .339 | .501 | ||||||||

| CD4-T | .136 | .245 | .580 | ||||||||

| NK | .213 | .391 | .588 | ||||||||

| B cells | .283 | .558 | .612 | ||||||||

| Monocytes | −.226 | .474 | .634 | ||||||||

| 2: SNP | |||||||||||

| rs9315202 | .007 | .003 | .015 | .044 | .029 | .129 | .017 | .018 | .334 | ||

| 3: PTSD Interaction | |||||||||||

| rs9315202 | −3.824 × 10−5 | <.001 | .682 | .002 | .001 | .049 | .001 | .001 | .285 | ||

Note. There was no correction for multiple testing as each model for different dependent variables was executed only once but results are combined into a single table for brevity; n = 308 for metabolic and CRP analyses and n = 252 for telomere analyses. Telomere batch and estimated white blood cell types were included as covariates in analyses predicting telomere length and are not applicable to analyses predicting MetS factor scores or CRP values. MetS factor scores have a mean of 0 and SD of 1. Beta values are unstandardized (standardized results are provided in the main text). KL = klotho; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; MetS = metabolic syndrome; CRP = C-reactive protein; PC = principal component; DNAm = DNA methylation; DNAm age res = DNA methylation age residuals; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; TL = telomere length; NK = natural killer cells.

Figure 2.

shows the association between PTSD severity and inflammation (CRP values) as a function of rs9315202 genotype.

3.4. rs9315202 X PTSD Severity in Association with White Matter Tracts

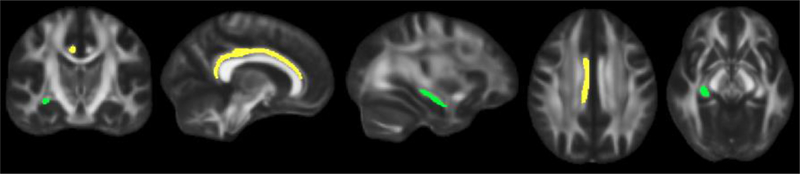

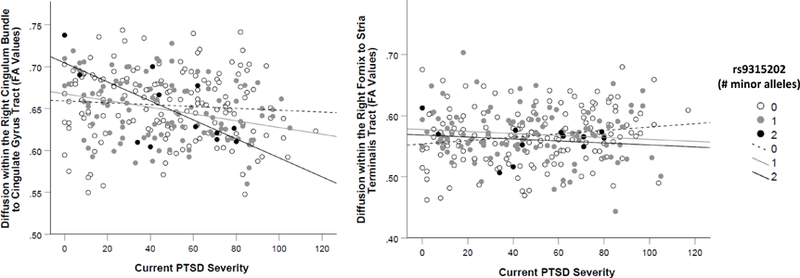

There was no main effect of rs9315202 on white matter tracts, but there was a significant PTSD X rs9315202 effect on FA values in the right cingulum bundle/cingulate gyrus (std β = −.54, corrected p = .005) and in right fornix/stria terminalis (std β = −.44, corrected p = .035; Table 5, Figure 3).5 The association between PTSD severity and diffusion within the cingulum bundle/cingulate gyrus tract was not significant in those with zero copies of the minor allele (GG, p = .336), but was associated in those with one (AG, p = .001) and two (AA, p = .015) copies (Figure 4). In the right fornix/stria terminalis, GG genotype was protective against loss of neural integrity as a function of PTSD severity (p = .027), while the association was not significant in the AG (p = .258) or AA (p = .632) groups (Figure 4). For the right cingulum bundle/cingulate tract, the interaction was evident in both the younger (p = .017) and older (p = .041) subsamples. In contrast, the SNP X PTSD severity effect on right fornix/stria terminalis was significant in the older subsample (p = .010) but not the younger one (p = .253). Inclusion of potential confounds did not alter the primary results (all interaction term p ≤ .007 when potential confounds were included in the models; Supplementary Materials).

Table 5.

Regression Results from Models with Corrected Significant Interactive Effects of Peak KL SNP X PTSD Severity on Fractional Anisotropy Values in White Matter Tracts (n = 185)

| Right Cingulum Bundle/Cingulate Gyrus |

Right Fornix/Stria Terminalis |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | SE | p | p corrected | β | SE | p | p corrected | |

| 1: Covariates | |||||||||

| Intercept | .660 | .018 | < .001 | N/A | .556 | .021 | < .001 | N/A | |

| Age | 2.200 × 10−4 | < .001 | .557 | N/A | −7.901 × 10−4 | < .001 | .061 | N/A | |

| Sex | −5.093 × 10−3 | .012 | .667 | N/A | .029 | .013 | .031 | N/A | |

| PC1 | −.041 | .054 | .451 | N/A | −.032 | 0.060 | .598 | N/A | |

| PC2 | −.055 | .055 | .315 | N/A | .052 | 0.062 | .397 | N/A | |

| PTSD severity | −2.469 × 10−4 | < .001 | .017 | N/A | 1.227 × 10−4 | < .001 | .290 | N/A | |

| DNAm age res | −8.801 × 10−4 | .001 | .176 | N/A | −1.223 × 10−4 | .001 | .867 | N/A | |

| 2: SNP | |||||||||

| rs9315202 | −8.367 × 10−5 | .005 | .986 | 1.000 | .006 | .005 | .238 | .825 | |

| 3: PTSD Interaction | |||||||||

| rs9315202 | −5.889 × 10−4 | < .001 | .001 | .005 | −5.520 × 10−4 | < .001 | .004 | .035 | |

Note. Only results from models in which the interaction term was significantly associated with the white matter tract after correction for multiple testing across 4 bilateral tracts (8 total) are shown. Results for other tracts and DTI metrics are listed in Tables S6 and S7. KL = klotho; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PC = principal component; DNAm = DNA methylation; DNAm age res = DNA methylation age residuals.

Figure 3.

shows the white matter tracts that were associated with the rs9315202 by PTSD severity interaction term. The right cingulum bundle/cingulate gyrus is shown in yellow and the right fornix/stria terminalis is identified in green. From left to right, images represent, coronal, sagittal (next two), and axial (last two) slices.

Figure 4.

shows the association between PTSD severity and diffusion (FA values) in the right cingulum bundle/cingulate gyrus tract (Panel A, left) and in the right fornix/stria terminalis (Panel B, right) as a function of rs9315202 genotype in the clinical cohort. PTSD was more strongly associated with degraded neural integrity in those with two copies of the minor allele at this locus.

4. Discussion

Elucidating relationships across multiple biomarkers of accelerated aging is critical for identifying coordinating aging processes and for discovering new molecular targets to slow the pace of cellular aging. Results of this study showed that rs9315202 in the longevity gene KL evidenced a consistent pattern of association with multiple peripheral and neuroimaging biomarkers of cellular aging. This SNP interacted with various indices of psychiatric stress, including PTSD and sleep disturbance (and nominally, with pain) to predict advanced DNAm age. The SNP was also associated with other metrics of accelerated aging including age-adjusted measures of CRP and white matter microstructural integrity such that individuals carrying two copies of the minor allele showed stronger positive associations between PTSD and cellular aging. The minor allele of the same SNP was also associated with worsening metabolic pathology. These results raise the possibility that KL genotype may contribute to the coordination of accelerated aging across the periphery and central nervous system such that those with the risk variant develop a systemic pathological aging response to environmental stress. Nearly all these effects were accentuated in the relatively older subjects. As circulating klotho is known to decrease with age (Semba et al., 2011; Semba et al., 2014), this suggests that the SNP potentiates this decline in older adults, leaving them more vulnerable to the biological effects of stress. This is consistent with the notion of age-dependent effects of KL, such as loss of klotho neuroprotection in older adults as a function of genotype (Shardell et al., 2015; Mengel-From et al., 2016). In our sample of highly stressed veterans with a marked prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses, this klotho-related decline may occur prematurely.

We also investigated associations with one of the most well studied KL polymorphisms (rs9527025). The minor allele of this SNP is thought to confer protection against age-related mental and physical decline (Arking et al., 2002). The findings of this study extend this to slower epigenetic aging and reduced metabolic pathology. To our knowledge, this is the first study to support a link between this variant and DNAm age residuals and it suggests that epigenetic aging may mediate the association between KL and age-related phenotypes, such as cognitive decline and metabolic pathology, though longitudinal data is needed to provide a strong test of this hypothesis. Additional evidence for a role of KL on advanced epigenetic age was evident in the interaction between rs398655 and pain in association with DNAm age residuals. The minor allele of this SNP in this study was protective, consistent with prior evidence of its association with enhanced cognitive function (Mengel-From et al., 2016). The DNAm age algorithm does not include KL probes, thus these associations represent novel findings that are not merely an artifact of the genes in the index.

The KL-associated brain regions in this study were also consistent with prior findings. The peak interaction SNP was associated with reduced microstructural integrity in white matter tracts involving the right cingulum bundle/cingulate and fornix/stria terminalis. The cingulum bundle is a ring-shaped limbic association fiber that links prefrontal, temporal, parietal, and subcortical structures, including hippocampus, parahippocampus, and amygdala (Bubb et al., 2018); integrity of this tract has been associated with PTSD (Daniels et al., 2013). The implicated portion of the tract is relatively more anterior and superior than the region of the bundle more closely connected to the hippocampus, which was not associated with KL in this study. The implicated region shows age-related decline and is involved in executive functions and working memory (Bubb et al., 2018), which have also previously been associated with KL (Dubal et al., 2014). We found lateralized effects in the right hemisphere of this prefrontal association fiber and this is consistent with prior work suggesting KL-related right DLPFC morphological changes (Yokoyama et al., 2015). The same KL SNP (rs9315202) interacted with PTSD to predict integrity of the right fornix/stria terminalis. The fornix is a triangular shaped commissural tract linking frontal regions to the hippocampus and has been associated with memory performance and Alzheimer’s disease (Mielke et al., 2012). Limbic and frontal morphological and functional alterations are frequently associated with PTSD (Pitman et al., 2012) and these results suggest that stress-associated morphological decline is dependent, in part, on KL.

The SNP rs9315202 has not previously been described in the literature, but is in complete or high LD with other SNPs (which are not included on this genotyping chip) which have been identified in prior longevity-related studies. The literature suggests that rs1207362, which is in high LD with our peak SNP (r2 = .93, D’ = 1.0) was associated with longevity in a highly aged sample (Soerensen et al., 2012). Few studies have comprehensively studied the landscape of KL variants in association with multiple age-related phenotypes or in interaction with environmental stressors and our results highlight the importance of doing so.

The risk versus protective effects of KL variants may operate through multiple dynamic biological mechanisms. The encoded protein (α-klotho), considered a humoral “longevity factor” (Yokoyama et al., 2017), separates from its transmembrane form to inhibit insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1; Kurosu et al., 2005), a critical contributor to an organism’s lifespan (Kenyon, 2010). In mice, klotho reduced oxidative stress-related cell death and related DNA and neuronal damage (Yamamoto et al., 2005; Zeldich et al., 2014). It also altered endothelial cell functioning (Saito et al., 1998; Nagai et al., 2000) and protected cardiac tissue from inflammatory toxicity (Hui et al., 2017), via intermediate inflammatory and oxidative stress processes (Maekawa et al., 2009). In humans, plasma klotho levels were inversely associated with CRP (Semba et al., 2011), and CSF klotho levels were positively related to antioxidant capacity in multiple sclerosis patients (Aleagha et al., 2015). Klotho also binds to fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs; Kurosu et al., 2006), integral to neural cell development and survival (Yun et al., 2010), and plays a role in Wnt signaling (Liu et al., 2007).

There is good reason to consider the potential therapeutic role of klotho as there is evidence that neurodegenerative phenotypes may be reversed with klotho. A klotho protein fragment delivered peripherally improved cognition and memory in both young and aged mice, though it did not cross the blood brain barrier (Leon et al., 2017). Delivery of viral vectors to the ventricles and hippocampus in middle-aged and old mice increased expression of a kl isoform across multiple brain regions (including prefrontal cortex and hippocampus), and improved mobility, memory, and cognition (Massó et al., 2017). Therapeutic effects on white matter have also been reported: kl overexpression in mice yielded remyelination of the corpus callosum following experimentally-induced demyelination (Zeldich et al., 2015). State-of-the-science gene editing techniques, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR), may offer therapeutic opportunities to alter endogenous klotho levels and improve health, neural integrity, and cognition, as recently demonstrated in human neuronal and kidney cell lines (Chen et al., 2018). These studies collectively suggest a role for klotho in neuroprotection and as a potential therapeutic agent to reverse or slow the pace of cellular aging.

Results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Generalizability is limited to the white, primarily male, non-Hispanic veteran population and replication in more diverse samples is needed. We did not have sufficient sample size to perform three-way interaction tests with age and thus age-stratified analyses should be interpreted cautiously and should be reevaluated in larger samples. As well, other biological and behavioral indices of cellular aging, such as unmeasured immune and inflammatory markers, immune-related gene expression, additional white matter tracts, and measures of frailty and motor function, that were not examined may be relevant to our understanding of KL on accelerated aging. Similarly, there may be other important metrics of psychiatric stress that interact with KL that were not examined in this study. Most importantly, this study did not include a replication sample and thus evaluation of the consistency of this effect in other samples is critical. The validity of the findings reported here is, however, substantiated by the similarity in patterns of association across the periphery and neuroimaging parameters reflecting multiple biological processes and stressors.

Findings of this study contribute to a growing literature suggesting a major role for KL across multiple markers of accelerated aging, including epigenetic aging, inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and loss of neural integrity. The KL variant rs9315202 altered the influence of psychiatric stress on accelerated aging across the periphery and imaging-markers of the central nervous system, perhaps via insufficient KL expression and subsequent loss of later-life klotho protections. Findings not only contribute to our understanding of a coordinated stress-related accelerated aging process, but also suggest the potential broad therapeutic value of klotho enhancement in those most at risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant number R03AG051877 (EJW)], United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences R&D (CSRD) Service Merit Review Award [grant number I01 CX-001276-01 (EJW)], National Institute of Mental Health [grant number 5T32MH019836-18 (FGM)], National Institute of Mental Health [grant number R21MH102834 (MWM), VA CSR&D Career Development Award [grant number 1 IK2 CX001772-01 (DRS)], and VA BLR&D Merit Award [grant number 1I01BX003477-01 (MWL)]. This work was also supported by a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE 2013A) to EJW, as administered by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and by the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS), a VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Traumatic Brain Injury Center of Excellence (B9254-C), and the Cooperative Studies Program, Department of Veterans Affairs. This research is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Pharmacogenomics Analysis Laboratory, Research and Development Service, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas, and the National Center for PTSD. The contents of this abstract do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

We also replicated all analyses with rs9527025, even though its association with DNAm age residuals was not corrected significant in our first regression. This SNP is one of the variants in the KL-VS haplotype that is in 100% LD. Because this is a widely published SNP, the criteria for significance was set at p < .05, as results pertaining to this SNP capture replication of its effect on age-related phenotypes. The other KL-VS variant, rs9536314, was also on the chip, but had a high missing rate (7%) and was excluded from analyses. However, the former SNP is a perfect proxy for the latter in European ancestry samples.

The inclusion of the latter term was to ensure that significant effects for KL X PTSD severity were not simply a function of covariance between the interaction term and DNAm age residuals.

There was also no main or interactive effect of the KL-VS variant, rs9527025, in association with telomere length.

In parallel analyses, the KL-VS variant, rs9527025, just missed the threshold for significance in association with MetS factor scores (std β = −.070, p = .083), though the effect was significant in the older subsample (std β = −.14, p = .025). No effects of this SNP emerged in predicting log CRP values.

In parallel analyses with the KL-VS SNP rs9527025, this SNP interacted with PTSD to predict FA values in the right fornix/stria terminalis (std β = −.33, p = .039). It was not associated with the right cingulum bundle/cingulate gyrus tract.

References

- Aleagha MSE, Siroos B, Ahmadi M, Balood M, Palangi A, Haghighi AN, & Harirchian MH (2015). Decreased concentration of klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 281, 5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking DE, Atzmon G, Arking A, Barzilai N, & Dietz HC (2005). Association between a functional variant of the klotho gene and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, stroke, and longevity. Circulation Research, 96(4), 412–418. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000157171.04054.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking DE, Becker DM, Yanek LR, Fallin D, Judge DP, Moy TF, … Dietz HC (2003). Klotho allele status and the risk of early-onset occult coronary artery disease. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 72(5), 1154–1161. doi: 10.1086/375035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M, Arking A, Mian IS, Fried L, … Dietz HC (2002). Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(2), 856–861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022484299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, & Irizarry RA (2014). Minfi: A flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics, 30(10), 1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis D, Bartlett DB, Patel HP, & Roberts HC (2013). Understanding how we age: Insights into inflammaging. Longevity & Healthspan, 2(1), 8–8. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, & Keane TM (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boks MP, van Mierlo HC, Rutten BP, Radstake TR, De Witte L, Geuze E, … Vermetten E (2015). Longitudinal changes of telomere length and epigenetic age related to traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 51, 506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Miller GE, Yu T, Beach SRH, & Chen E (2016). Supportive Family Environments Ameliorate the Link Between Racial Discrimination and Epigenetic Aging: A Replication Across Two Longitudinal Cohorts. Psychological Science, 27(4), 530–541. doi: 10.1177/0956797615626703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubb EJ, Metzler-Baddeley C, & Aggleton JP (2018). The cingulum bundle: Anatomy, function, and dysfunction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 92, 104–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J, & d’Adda di Fagagna F (2007). Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8(9), 729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM (2002). Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Research, 30(10), e47–e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JE, Esquivel S, Goldberg A, Seeman TE, Effros RB, Dock J, … Irwin MR (2016). Insomnia and Telomere Length in Older Adults. Sleep, 39(3), 559–564. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BH, Marioni RE, Colicino E, Peters MJ, Ward-Caviness CK, Tsai PC, … Horvath S (2016). DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: Meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging (Albany NY), 8(9), 1844–1865. doi: 10.18632/aging.101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Pollack S, Hunter DJ, Hirschhorn JN, Kraft P, & Price AL (2013). Improved ancestry inference using weights from external reference panels. Bioinformatics, 29(11), 1399–1406. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Sloane JA, Li H, Aytan N, Giannaris EL, Zeldich E, … Abraham CR (2013). The antiaging protein klotho enhances oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination of the CNS. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(5), 1927–1939. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2080-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Zeldich E, Li Y, Yuste A, & Abraham CR (2018). Activation of the anti-aging and cognition-enhancing gene klotho by CRISPR-dCas9 transcriptional effector complex. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 64(2), 175–184. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-1011-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasto CL, Semba RD, Sun K, Cappola AR, Bandinelli S, & Ferrucci L (2012). Relationship of low-circulating “anti-aging” klotho hormone with disability in activities of daily living among older community-dwelling adults. Rejuvenation Research, 15(3), 295–301. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JK, Lamke JP, Gaebler M, Walter H, & Scheel M (2013). White matter integrity and its relationship to PTSD and childhood trauma—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 30(3), 207–216. doi: 10.1002/da.22044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bona D, Accardi G, Virruso C, Candore G, & Caruso C (2014). Association of klotho polymorphisms with healthy aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rejuvenation Research, 17(2), 212–216. doi: 10.1089/rej.2013.1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew DA, Katz R, Kritchevsky S, Ix J, Shlipak M, Gutierrez OM, … Sarnak M (2017). Association between soluble klotho and change in kidney function: The health aging and body composition study. Journals of the American Society of Nephrology, 28(6), 1859–1866. doi: 10.1681/asn.2016080828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, Broestl L, Worden K, Wang D, … Yu G-Q (2014). Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition. Cell Reports, 7(4), 1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Zhu L, Sanchez PE, Worden K, Broestl L, Johnson E, … Mucke L (2015). Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(6), 2358–2371. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5791-12.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois T, Reynaert C, Jacques D, Lepiece B, Patigny P, & Zdanowicz N (2018). Immunity and psychiatric disorders: Variabilities of immunity biomarkers are they specific? Psychiatria Danubina, 30, Supplement 7, 447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duce JA, Podvin S, Hollander W, Kipling D, Rosene DL, & Abraham CR (2008). Gene profile analysis implicates klotho as an important contributor to aging changes in brain white matter of the rhesus monkey. Glia, 56(1), 106–117. doi: 10.1002/glia.20593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, & Prather AA (2018). Stress, Telomeres, and Psychopathology: Toward a Deeper Understanding of a Triad of Early Aging. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 371–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, Williams J, & Benjamin L User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders: SCID-II 1997. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin JP, Triche TJ Jr., & Hansen KD (2017). Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEpic array with minfi. Bioinformatics, 33(4), 558–560. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y, Breitling LP, & Brenner H (2016). Relationship of tobacco smoking and smoking-related DNA methylation with epigenetic age acceleration. Oncotarget, 7(30), 46878–46889. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus J, von Kanel R, Lasserre AM, Strippoli MF, Vandeleur CL, Castelao E, … Merikangas KR (2018). The bidirectional relationship between anxiety disorders and circulating levels of inflammatory markers: Results from a large longitudinal population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 35(4), 360–371. doi: 10.1002/da.22710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton E (2017). Mythology: Timeless tales of gods and heroes: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, Chan RF, Hattab MW, Shabalin AA, … Penninx B (2018). Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(8), 774–782. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S (2013). DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biology, 14(10), R115–R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, Zhai Y, Ao L, Cleveland JC Jr., Liu H, Fullerton DA, & Meng X (2017). Klotho suppresses the inflammatory responses and ameliorates cardiac dysfunction in aging endotoxemic mice. Oncotarget, 8(9), 15663–15676. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin MR, Aslibekyan S, Do A, Zhi D, Hidalgo B, Claas SA, … Arnett DK (2018). Metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers are associated with epigenetic aging acceleration estimates in the GOLDN study. Clinical Epigenetics, 10, 56. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0481-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Vance LA, Cross D, Knight AK, Kilaru V, Michopoulos V, … Smith AK (2017). Exposure to violence accelerates epigenetic aging in children. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 8962. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09235-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami M, Mehrabi F, Allameh A, Pahlevan Kakhki M, Amiri M, & Emami Aleagha MS (2017). Klotho gene expression decreases in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 381, 305–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ (2010). The genetics of ageing. Nature, 464(7288), 504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GD, Rosene DL, & Abraham CR (2012). Promoter methylation and age-related downregulation of klotho in rhesus monkey. Age, 34(6), 1405–1419. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9315-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, & Burns K (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 210–224. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, … Nabeshima YI. (1997). Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature, 390, 45. doi: 10.1038/36285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, … Kuro-o M (2006). Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(10), 6120–6123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, … Kawaguchi H (2005). Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone klotho. Science, 309(5742), 1829–1833. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon J, Moreno AJ, Garay BI, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL, Wang D, & Dubal DB (2017). Peripheral elevation of a klotho fragment enhances brain function and resilience in young, aging, and alpha-Synuclein transgenic mice. Cell Reports, 20(6), 1360–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ME, Lu AT, Bennett DA, & Horvath S (2015). Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging (Albany NY), 7(12), 1198–1211. doi: 10.18632/aging.100864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist D, Epel ES, Mellon SH, Penninx BW, Révész D, Verhoeven JE, … Wolkowitz OM (2015). Psychiatric disorders and leukocyte telomere length: Underlying mechanisms linking mental illness with cellular aging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 55, 333–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, … Finkel T (2007). Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science, 317(5839), 803–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue MW, Amstadter AB, Baker DG, Duncan L, Koenen KC, Liberzon I, … Ressler KJ (2015). The psychiatric genomics consortium posttraumatic stress disorder workgroup: Posttraumatic stress disorder enters the age of large-scale genomic collaboration. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(10), 2287–2297. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C, Galluzzi L, Freije JMP, Madeo F, & Kroemer G (2016). Metabolic control of longevity. Cell, 166(4), 802–821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa Y, Ishikawa K, Yasuda O, Oguro R, Hanasaki H, Kida I, … Rakugi H (2009). Klotho suppresses TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in the endothelium and attenuates NF-Kappab activation. Endocrine, 35(3), 341–346. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9181-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar V, & Christopher R (2011). Association of exonic variants of klotho with metabolic syndrome in Asian Indians. Clinica Chimica Acta, 412(11–12), 1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar V, Nagaraja D, & Christopher R (2010). Association of the functional KL-VS variant of klotho gene with early-onset ischemic stroke. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 403, 412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massó A, Sanchez A, Bosch A, Gimenez-Llort L, & Chillon M (2018). Secreted alpha-klotho isoform protects against age-dependent memory deficits. Mol Psychiatry, 23(9), 1–11. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Kalia M (2010). The role of corticosteroids and stress in chronic pain conditions. Metabolism, 59, Supplemental 1, S9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, & Fortier CB (2017). A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: The TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(3). doi: 10.1002/mpr.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R (1987). The Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain, 30(2), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengel-From J, Soerensen M, Nygaard M, McGue M, Christensen K, & Christiansen L (2016). Genetic variants in klotho associate with cognitive function in the oldest old group. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(9), 1151–1159. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos V, Rothbaum AO, Jovanovic T, Almli LM, Bradley B, Rothbaum BO, … Ressler KJ (2015). Association of CRP genetic variation and CRP level with elevated PTSD symptoms and physiological responses in a civilian population with high levels of trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(4), 353–362. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos V, Powers A, Gillespie CF, Ressler KJ, & Jovanovic T (2017). Inflammation in Fear- and Anxiety-Based Disorders: PTSD, GAD, and Beyond. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 254–270. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke MM, Okonkwo OC, Oishi K, Mori S, Tighe S, Miller MI, … Lyketsos CG (2012). Fornix integrity and hippocampal volume predict memory decline and progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 8(2), 105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Maniates H, Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Schichman SA, Stone A, … McGlinchey R (2018). CRP polymorphisms and DNA methylation of the AIM2 gene influence associations between trauma exposure, PTSD, and C-reactive protein. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 67, 194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Sadeh N, Logue M, Spielberg JM, Hayes JP, … McGlinchey R (2015). A novel locus in the oxidative stress-related gene ALOX12 moderates the association between PTSD and thickness of the prefrontal cortex. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 62, 359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müezzinler A, Zaineddin AK, & Brenner H (2013). A systematic review of leukocyte telomere length and age in adults. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(2), 509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai R, Saito Y, Ohyama Y, Aizawa H, Suga T, Nakamura T, … Kuroo M (2000). Endothelial dysfunction in the klotho mouse and downregulation of klotho gene expression in various animal models of vascular and metabolic diseases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 57(5), 738–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevalainen T, Kananen L, Marttila S, Jylhävä J, Mononen N, Kähönen M, … Hurme M (2017). Obesity accelerates epigenetic aging in middle-aged but not in elderly individuals. Clinical Epigenetics, 9, 20. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0301-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, Shin LM, Orr SP, Gilbertson MW, … Liberzon I (2012). Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(11), 769–787. doi: 10.1038/nrn3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, Benros ME, Dalsgaard S, de Jonge P, … McGrath JJ (2019). Exploring Comorbidity Within Mental Disorders Among a Danish National Population. JAMA Psychiatry Published online January 16, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather AA, Epel ES, Arenander J, Broestl L, Garay BI, Wang D, & Dubal DB (2015). Longevity factor klotho and chronic psychological stress. Translational Psychiatry, 5, e585. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach A, Levine ME, Tanaka T, Lu AT, Chen BH, Ferrucci L, Ritz B, …Horvath S (2017). Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging, 9, 419–437. 10.18632/aging.101168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Révész D, Verhoeven JE, Picard M, Lin J, Sidney S, Epel ES, … Puterman E (2018). Associations between cellular aging markers and metabolic syndrome: Findings from the cardia study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(1), 148–157. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelas M, Thalamuthu A, Oldmeadow C, Evans TJ, Armstrong NJ, Kwok JB, … Mather KA (2018). Review and meta-analysis of genetic polymorphisms associated with exceptional human longevity. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 175, 24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Yamagishi T, Nakamura T, Ohyama Y, Aizawa H, Suga T, … Nagai R (1998). Klotho protein protects against endothelial dysfunction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 248(2), 324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, Hevelone ND, Fischl B, Corkin S, Rosas HD, & Dale AM (2005). Age-related changes in prefrontal white matter measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1064, 37–49. doi: 10.1196/annals.1340.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K, Bandinelli S, Dalal M, Crasto C, … Ferrucci L (2011). Plasma klotho and cardiovascular disease in adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(9), 1596–1601. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba RD, Cappola AR, Sun K, Bandinelli S, Dalal M, Crasto C, … Ferrucci L (2011). Plasma klotho and mortality risk in older community-dwelling adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 66(7), 794–800. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba RD, Moghekar AR, Hu J, Sun K, Turner R, Ferrucci L, & O’Brien R (2014). Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Letters, 558, 37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.10.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Semba RD, Kalyani RR, Bandinelli S, Prather AA, Chia CW, & Ferrucci L (2017). Plasma klotho and frailty in older adults: Findings from the InCHIANTI study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Semba RD, Rosano C, Kalyani RR, Bandinelli S, Chia CW, & Ferrucci L (2015). Plasma klotho and cognitive decline in older adults: Findings from the InCHIANTI study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(5), 677–682. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki M, Yoshimura K, Shibata M, Koike M, Matsuura N, Uchiyama Y, & Gotow T (2008). Morphological and biochemical signs of age-related neurodegenerative changes in klotho mutant mice. Neuroscience, 152(4), 924–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T, & Watson D (2006). The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychological Medicine, 36(11), 1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/s0033291706008452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, … Matthews PM (2006). Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage, 31(4), 1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soerensen M, Dato S, Tan Q, Thinggaard M, Kleindorp R, Beekman M, … Westendorp RG (2012). Human longevity and variation in GH/IGF-1/insulin signaling, DNA damage signaling and repair and pro/antioxidant pathway genes: Cross sectional and longitudinal studies. Experimental Gerontology, 47(5), 379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah M, & Sun Z (2018). Klotho deficiency accelerates stem cells aging by impairing telomerase activity. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences Vol. XX, No. XX, 1–12. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly261 doi:10.1093/gerona/gly26110.1093/gerona/gly261doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Bovin MJ, Green JD, Mitchell KS, Stoop TB, Barretto KM, … Marx BP (2016). Longitudinal associations between post-traumatic stress disorder and metabolic syndrome severity. Psychological Medicine, 46(10), 2215–2226. doi: 10.1017/s0033291716000817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Hayes JP, Sadeh N, Schichman SA, Stone A, … Miller MW (2016). Accelerated DNA methylation age: Associations with PTSD and neural integrity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 63, 155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Morrison FG, Wilcox ES, Stone A, Schichman SA, … Miller MW (2018). Posttraumatic psychopathology and the pace of the epigenetic clock: A longitudinal investigation. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, Schichman SA, Stone A, Sadeh N, … Miller MW (2018). Accelerated DNA methylation age: Associations with posttraumatic stress disorder and mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80(1), 42–48. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Maniates H, Nugent N, Maihofer AX, Armstrong D, Ratanatharathorn A, … Logue MW (2018). Traumatic stress and accelerated DNA methylation age: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 92, 123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Sadeh N, Leritz EC, Logue MW, Stoop TB, McGlinchey R, … Miller MW (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder as a catalyst for the association between metabolic syndrome and reduced cortical thickness. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5), 363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff K, Gatti S, Wettstein JG, & Foster RG (2010). Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(8), 589–599. doi: 10.1038/nrn2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Gurnani P, Nandi A, Kurosu H, … Kuro-o M (2005). Regulation of oxidative stress by the anti-aging hormone klotho. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280(45), 38029–38034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509039200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama JS, Marx G, Brown JA, Bonham LW, Wang D, Coppola G, … Dubal DB (2017). Systemic klotho is associated with klotho variation and predicts intrinsic cortical connectivity in healthy human aging. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 11(2), 391–400. doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9598-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama JS, Sturm VE, Bonham LW, Klein E, Arfanakis K, Yu L, … Dubal DB (2015). Variation in longevity gene klotho is associated with greater cortical volumes. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 2(3), 215–230. doi: 10.1002/acn3.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun Y-R, Won JE, Jeon E, Lee S, Kang W, Jo H, … Kim H-W (2010). Fibroblast growth factors: Biology, function, and application for tissue regeneration. Journal of Tissue Engineering, 2010, 218142. doi: 10.4061/2010/218142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannas AS, Arloth J, Carrillo-Roa T, Iurato S, Röh S, Ressler KJ, … Mehta D (2015). Lifetime stress accelerates epigenetic aging in an urban, African American cohort: Relevance of glucocorticoid signaling. Genome Biology, 16(1), 266. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0828-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldich E, Chen CD, Avila R, Medicetty S, & Abraham CR (2015). The anti-aging protein klotho enhances remyelination following cuprizone-induced demyelination. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 57(2), 185–196. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0598-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldich E, Chen CD, Colvin TA, Bove-Fenderson EA, Liang J, Tucker Zhou TB, … Abraham CR (2014). The neuroprotective effect of klotho is mediated via regulation of members of the redox system. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(35), 24700–24715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.567321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.