Tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis is a zoonotic infection of the Northern Hemisphere that mainly affects the skin, lymph nodes, bloodstream, and lungs. Other manifestations of tularemia are very rare, especially those with musculoskeletal involvement. Presenting in 2016, we diagnosed two cases of periprosthetic knee joint infections (PJI) caused by Francisella tularensis in Europe (one in Switzerland and one in the Czech Republic).

KEYWORDS: Francisella tularensis, periprosthetic joint infections, biofilms, tick-borne pathogens, zoonotic infectiousness

ABSTRACT

Tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis is a zoonotic infection of the Northern Hemisphere that mainly affects the skin, lymph nodes, bloodstream, and lungs. Other manifestations of tularemia are very rare, especially those with musculoskeletal involvement. Presenting in 2016, we diagnosed two cases of periprosthetic knee joint infections (PJI) caused by Francisella tularensis in Europe (one in Switzerland and one in the Czech Republic). We found only two other PJI cases in the literature, another knee PJI diagnosed 1999 in Ontario, Canada, and one hip PJI in Illinois, USA, in 2017. Diagnosis was made in all cases by positive microbiological cultures after 3, 4, 7, and 12 days. All were successfully treated, two cases by exchange of the prosthesis, one with debridement and retention, and one with repeated aspiration of the synovial fluid only. Antibiotic treatment was given between 3 weeks and 12 months with either ciprofloxacin-rifampin or with doxycycline alone or doxycycline in combination with gentamicin. Zoonotic infections should be considered in periprosthetic infections in particular in culture-negative PJIs with a positive histology or highly elevated leukocyte levels in synovial aspiration. Here, we recommend prolonging cultivation time up to 14 days, performing specific PCR tests, and/or conducting epidemiologically appropriate serological tests for zoonotic infections, including that for F. tularensis.

INTRODUCTION

The most commonly isolated microorganisms in periprosthetic joint infections (PJIs) are staphylococci, streptococci, enterococci, Gram-negative rods, and anaerobic bacteria (1). However, 5 to 35% of PJIs remain culture negative (1) either because of antibiotics given prior to diagnostic aspiration, the inability to detect a recognized PJI pathogen using currently available diagnostic methods, or the difficulty of cultivating or otherwise identifying fastidious microorganisms such as anaerobes, mycobacteria, or fungi.

Little is known about zoonotic infections in joint replacements. We report two PJI cases caused by Francisella tularensis diagnosed in Europe. We searched for positive cultures and specific serology for F. tularensis in our microbiological database in general and reviewed the literature of other orthopedic infections caused by F. tularensis. Focusing on PJIs, we summarized their clinical and microbiological characteristics in a minireview.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture and identification methods.

(i) University of Zurich. To extract bacteria from periprosthetic tissue, samples were vortexed using 4-mm glass beads (Sarstedt, Nürmbrecht, Germany). After homogenization, samples were incubated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions on agar plates and in thioglycolate broth (BD, Allschwil, Switzerland) for enrichment. For aerobic cultivation, Columbia sheep blood agar without antibiotics (bioMérieux, Mary-l’Etoile, France), colistin-nalidixic acid (CNA) blood agar (bioMérieux), MacConkey agar (bioMérieux), and Crowe agar (chocolate agar supplemented with bacitracin and IsoVitaleX [Difco GC medium; Becton, Dickinson]) were used. Brucella agar (anaerobic sheep blood agar plates with hemin and vitamin K1; bioMérieux), kanamycin-vancomycin agar (laked sheep blood brucella agar plates with kanamycin and vancomycin; BD), and phenylethyl alcohol agar plates (BD) were used for anaerobic cultivation (Whitley anaerobic workstation MG1000; Don Whitley Scientific, West Yorkshire, England). The agar plates were incubated for 7 days at 37°C. Thioglycolate broth medium was inspected daily for cloudiness and then plated onto chocolate (aerobic) and brucella (anaerobic) agar plates for further identification. If thioglycolate broth cultures were negative after 10 days of cultivation, blind subcultures plated on chocolate and brucella agar plates were performed and cultivated for another 2 to 3 days. Any suspicious bacterial colony was to be analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) using a Bruker MALDI Biotyper in combination with research-use-only (RUO) versions of the MALDI Biotyper software package (version 3.0) and the reference database version 3.3.1.0 (4,613 entries) or later database versions.

(ii) České Budějovice Hospital. Cultivation methods and duration of cultivations at České Budějovice Hospital were done in a manner similar to that at the University of Zurich.

Retrospective case finding.

We searched for published PJI cases caused by F. tularensis using PubMed, Scopus, and Medline for an epidemiological investigation (searched keywords were Francisella, tular*, joint, arthritis, prosth*, osteomyelitis, bone, and replacement).

Retrospective microbiological review.

We reviewed our hospital databases at the Institute for Clinical Microbiology at the University of Zurich and the České Budějovice Hospital for positive F. tularensis serology or cultures with association of bone and joint infection.

Obtaining other data.

Data not containted in the original case studies were obtained by email communication from the corresponding authors of the cited papers.

RESULTS

Two cases in Europe in 2016.

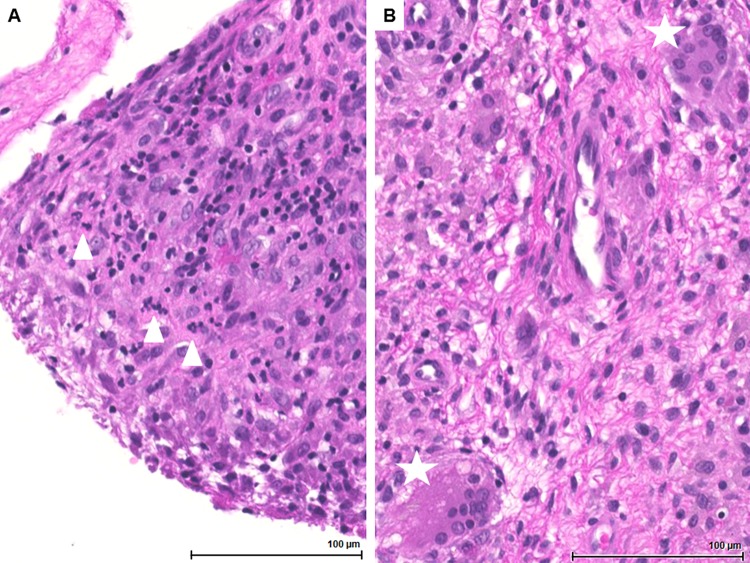

(i) Case 1. An 84-year-old Swiss woman presented in July 2015 with chronic knee pain with reported onset since December 2014 after a right knee joint arthroplasty in 2002. Intermittently, she observed an erythema above the knee without swelling. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were elevated, at 64 mg/liter. Synovial aspiration of the right knee joint revealed elevated leukocyte levels of 11,850 cells/μl with a dominance of neutrophils (80%) without any growth of microorganisms. X-rays showed no loosening of the implant but small tibial osteolysis. A PJI was suspected, and the prosthesis was removed as the first surgery of a two-stage exchange of the prosthesis. At time of explantation of the prosthesis, five out of six tissue biopsy specimens showed growth of F. tularensis on a blind subculture on day 12 after a blind subculture of thioglycolate broth inoculated on day 10, while inoculation on agar plates remained negative. Histology of a tissue biopsy of the recessus medialis revealed focal acute inflammation (dominance of neutrophils) and extended wear of the prosthesis (Fig. 1). Serology results with elevated IgM and IgG were in line with an F. tularensis infection. We changed the empirical intravenous antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanate to oral doxycycline for a total duration of 6 weeks after implant removal. After 2 weeks off antibiotics, the new knee prosthesis was successfully implanted. In the last follow-up 2 years later, the patient was feeling well, had a good quality of life, and was free of infection, and a follow-up tularemia IgM titer decreased from 232 to 111 U/ml. As potential modes of acquisition of F. tularensis, we thought of airborne transmission of contaminated dust while cleaning the rabbit barn located nearby, or a tick bite. However, the patient could not remember any tick bite. She remembered having an episode of fever and sore throat a few months before the onset of knee pain. None of the 10 laboratory staff involved in handling the culture-positive agar plates showed seroconversion after 2 months.

FIG 1.

Histopathology of the knee PJI case in Zurich with acute inflammation with dominance of neutrophils at time of implant removal. (A) Tunica synovialis with florid granulocytic inflammation. Triangles indicate small clusters of neutrophils (hematoxylin and eosin [HE] staining, ×200 magnification). (B) Foreign body reaction to prosthetic material with diffuse histiocytic infiltration and multinucleated giant cells, indicated by asterisks (HE staining, ×200 magnification).

(ii) Case 2. An 84-year-old Czech male had a history of right knee total arthroplasty in 2006 and PJI in the same joint caused by Escherichia coli in 2008 that was treated with open synovectomy, mobile component replacement, and retention of the fixed components, along with antibiotic therapy. After this, he was asymptomatic for 8 years.

In July 2016, he presented with fever, abdominal pain, and elevated inflammatory parameters (CRP level, 166 mg/liter), but no source of infection was found. He was treated with oral amoxicillin-clavulanate and discharged as fever and abdominal symptoms rapidly resolved. Ten days later, he presented to an orthopedic clinic complaining of increasing pain in the right knee, where a large effusion had developed. Blood tests showed a leukocyte count of 4.80 × 109 cells/ml and CRP concentration of 98.4 mg/liter. The right knee effusion was aspirated, yielding over 70 ml of cloudy fluid, which showed highly elevated leukocytes (++++ by microscopy; flow cytometry was not possible because of high viscosity of the fluid) and no organisms. After 4 days of the aspirate incubation, small colonies of Gram-labile (indifferent state) to Gram-negative coccobacilli were seen on Columbia 5% sheep blood agar (Bio-Rad Corp., Hercules, CA, USA). Because of their morphological appearance, F. tularensis was suspected, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed from the colonies, which confirmed the identification. Serology for tularemia had shown a 1:80 titer (total antibody; microagglutination test; Bioveta, Inc., Ivanovice na Hané, Czech Republic).

The knee X-ray was not suggestive of loosening of the implant, and a synovectomy and mobile-component replacement with retention of the joint prosthesis were recommended. The patient declined any surgical intervention; therefore, he was treated with 100 mg doxycycline orally twice a day for 21 days, of which the first 10 days was in combination with 240 mg gentamicin intravenously once daily. Two months later, he presented with recurring effusion of the knee, and the second reaspiration showed fluid with minimum white cells, no bacterial growth of prolonged culture, and negative 16S rRNA gene PCR. He was given another course of antibiotics, this time being 500 mg ciprofloxacin orally twice a day for 20 days.

During the follow up, the persistent small pain-free effusion in his right knee was reaspirated after 4, 10, and 24 months from the initial presentation. All aspirates were unremarkable regarding cell count and culture-negative and 16S rRNA gene PCR-negative results. His blood inflammatory markers were unremarkable as well. He did not complain of any systemic symptoms, and the knee X-ray did not detect any signs of loosening. After 24 months, he was discharged from the clinic with the advice to be rereferred in case of any problems.

Personal history identified garden work and outdoor walks in the tularemia area of endemicity as the only risk factors for zoonotic infections. Given the abdominal symptoms, the intestinal form of tularemia was suspected to be the port of entry into the bloodstream and secondary spread to the knee.

The operating room and laboratory staff involved in handling of the first aspirate and culture-positive agar plates were offered a prophylactic course of doxycycline (n = 7). None of them developed any clinical symptoms of tularemia.

Retrospective case findings.

Two other PJI cases (2, 3) and one osteomyelitis case (4) but without a joint prosthesis were found in the literature. The clinical and microbiological characteristics of all four PJIs are summarized in Table 1. Three out of four PJI cases due to Francisella tularensis presented in knee arthroplasty. All were detected by positive microbiological cultures and confirmed by positive serology, three with confirmation result by molecular-genetic methods and one with additional acute inflammation in histopathology as an indirect sign (Fig. 1). All were successfully treated, two cases with exchange of the prosthesis, one with debridement and retention, and one with repeated aspiration of the synovial fluid only. Antibiotic treatment was given between 3 weeks and 12 months using either ciprofloxacin with or without rifampin or doxycycline with or without gentamicin.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of 4 patients with Francisella tularensis PJIs

| Characteristica | Data by case no., countryb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, Switzerland (23) | 2, Czech Republic | 3, Ontario, Canada (2) | 4, Illinois, USA (3) | |

| Age (yr), sex | 84, female | 84, male | 68, male | 77, male |

| Yr of presentation | 2016 | 2016 | 1999 | 2017 |

| Affected joint | Knee | Knee | Knee | Hip |

| Immunosuppression | No | No | Rheumatoid arthritis (methotrexate) | No |

| Previous infection of affected joint | No | E. coli PJI infection 8 years prior, cured with DAIR | Enterococcus faecalis PJI, cured | No, but recent (7 days) revision THR due to pain and limited range of movement |

| Potential source of acquisition | Housing of rabbits in next-door house (infected dust?) | No apparent exposure, but abdominal symptoms prior to joint effusion are suggestive of intestinal tularemia | Hunter, tick bite 6 mo before arthroplasty | Hunter, no tick bite |

| Time to diagnosis after previous surgical intervention/revision | 12 years | 8 years | 6 months | 25 years; bullous lesion on shin 1 yr before onset of symptoms |

| Clinical findings | Erythema, joint pain, no fever | Fever, abdominal pain, confusion, painful knee effusion | Discharge from joint, no fever | Fever, joint pain |

| CRP concn (mg/liter) | 81 | 98 | NA | 16 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 69 | NA | 47 | 96 |

| Microbiology | ||||

| Positive culture status | Yes (6 out of 7), thioglycolate broth; sonication negative | Yes, Columbia 5% sheep blood agar | Yes, chocolate agar | Yes (out of 2), Vitek cultures |

| Type of sample | Tissue cultures | Joint aspiration | Joint aspiration | Joint aspiration |

| Days of cultivation until growth | 12 (blind subculture) | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Molecular method | 16S rRNA gene and specific PCR negative in tissue sample; 16S rRNA gene sequencing of growing pathogen positive | 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing of the colonies grown on agar | Culture sequencing; F. tularensis tularensis bv. type B | NA |

| Serology result for F. tularensis | IgM, 232.6 U/ml (N, <10 U/ml); IgG, 126.4 U/ml (N, < 0 U/ml) | 1:80 titer (microagglutination) | 1:320 titer (microagglutination) | Results reported as positive from the lab without stating any titers |

| Finding in histopathology | Acute inflammation, wear of prosthesis | NA | NA | NA |

| Surgical treatment | 2-stage revision joint replacement | Repeated aspiration only | 2-stage revision joint replacement | DAIR |

| Antibiotic treatment | 6 wk; 100 mg doxycycline twice daily | 3 wk and 3 wk; 20 days of 100 mg doxycycline bd plus 10 days of 240 mg gentamicin od, followed by 20 days of 500 mg ciprofloxacin bd | 6 mo; ciprofloxacin-rifampin (unknown dose), initially no response to ciprofloxacin in monotherapy | 12 mo; 100 mg doxycycline bd |

| Cure (time to follow-up) | 2 years | 2 years | >6 months | 1 year |

| No. of healthcare workers who took postexposure antibiotic prophylaxis | 0 | 7 | Unknown | Unknown |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; N, normal.

DAIR, debridement, antibiotics, implant retention; THR, total hip replacement; NA, not available; bd, twice daily; od, once daily.

Microbiological database research.

(i) Zurich. In 12 PJI cases with available F. tularensis serology classified as culture-negative PJIs, F. tularensis serology remained negative, as found in a retrospective analysis of the microbiology database. Regarding positive growth in tissue biopsy specimens or blood cultures, only 7 other positive F. tularensis cultures were documented in the same period in Zurich but without any association with an orthopedic infection.

(ii) České Budějovice Hospital. No data about tularemia serology are available from prosthetic joint infections from České Budějovice Hospital. Between 2003 and 2015, only one positive blood culture out of 64 tularemia cases (1.6%) not related to orthopedic infections was detected (A. Chrdle, P. Tinavská, O. Dvořáčková, P. Filipová, V. Hnetilová, P. Žampach, K. Batistová, V. Chmelík, A. S. Semper, and N. J. Beeching, submitted for publication).

DISCUSSION

Orthopedic infections caused by F. tularensis are very rare. Next to our two PJI cases in Europe, we only found two other PJI cases, one described in Canada in 1999 (2, 3) and one in the United States in 2017 (2, 3). In other zoonotic PJIs, such as those caused by Listeria monocytogenes (5, 6), Coxiella burnetii (7), Pasteurella multocida (8), or Brucella species (9), there has recently been an increase in reported orthopedic cases. In contrast to the other zoonotic pathogens, we have not found any diagnosed native joint arthritis and found only one case of osteomyelitis, which was caused by direct inoculation from a cat bite after a penetrative open injury in conjunction with Pasteurella infection (4). Biofilm formation in F. tularensis, as it has been documented in vitro and in the aquatic environment (10), might be an important virulence factor in prosthetic material-related infection.

Three out of four PJI cases described here were localized in the knee joint. Two of them had a lesion on the lower limb, suggestive of an infected tick bite (11), leading to an ulceroglandular form of tularemia. Such a skin lesion (often presenting as a nonhealing ulcer) may persist for several months. F. tularensis bacteria disseminate via the lymphatic system to the regional lymph nodes and other tissues (11). Alternatively, PJI could be caused by a hematogenous spread of F. tularensis in transient bacteremia or introduced in a previously damaged tissue via migrating granulocytes or macrophages using a Trojan horse mechanism. All four cases had some type of previous inflammation in the affected joint arthroplasty so that we question the possibility of migration of macrophages into the joint for a reason other than tularemia. Those macrophages, which are attracted to a minor injury in the prosthetic joint, may have incidentally brought in F. tularensis in their vacuolae (12, 13), and the infection had then flared up after apoptosis. Due to the fact that two out of four patients were hunters, the transmission route could also be through exposure to blood or body fluid with contaminated meat (11). In Germany, between 2002 and 2016, 10 outbreaks of tularemia were associated with contact with wild animals in the context of hunting (14).

In all four PJI cases, diagnosis was made by culture-based methods in part with longer incubation times than expected in other pathogens more commonly isolated in PJI (1). In the Swiss case, the diagnosis would have been missed if the cultures were stopped at day 10. It can be hypothesized that other tularemia cases may have been missed due to short cultivation time, difficulty growing, and being categorized as culture-negative PJI cases (15). Some of them may have resolved spontaneously, while others might have been inadvertently rightly treated with ciprofloxacin, used in some centers as a part of empirical therapy for culture-negative PJIs.

The low numbers of positive F. tularensis cultures or serology results both in the microbiological laboratory of Zurich and České Budějovice illustrate the rare event of F. tularensis infection. In general, the majority of clinical tularemia cases are diagnosed by an antibody test and only a minority by culture. Two large case series of F. tularensis infections reported only 14% (149/1,034 cases, Turkey tularemia cohort) (16) and 20.8% (21/101 cases, French cohort 2006 to 2010) positive cultures (17). None of these cohorts, however, reported native or prosthetic joint or bone infections. The low sensitivity of the culture-based methods might be due to the current practice in many microbiology laboratories. Seven incubation days instead of 10 days is standard, and often only anaerobic cultures and enrichment broths are kept for 10 days.

The fact that all four so-far-reported tularemia PJI cases have been diagnosed by positive culture may signify that this is only the tip of the iceberg, and in reality, there are more undiagnosed cases. However, no zoonotic pathogens as potential PJI pathogens to be searched for are mentioned in major guidelines (18–21).

Antibiotic treatment in our four cases was given between 3 weeks and 12 months with either ciprofloxacin-rifampin or with doxycycline alone or in combination with gentamicin. Antibiotic susceptibility has not changed over the years, and doxycycline, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones alone or in combination are the mainstay of therapy (22). There are only limited data on the in vitro antibiotic susceptibility of F. tularensis; however, no major changes in susceptibility rates have been reported. The duration of antibiotic therapy of more common manifestations of tularemia usually does not exceed 3 weeks; however, there have been case reports of prolonged clinical courses of tularemia with the need for repeated antibiotic therapy (14). In all four reported cases of tularemia PJI, the antibiotic therapy was prolonged or repeated, and two of the cases appeared not to respond to the initial course of antibiotics.

There is also a significant public health and occupational health issue in cases where F. tularensis is cultured in a routine bench in microbiological laboratory from an unsuspecting sample. Every institution has a different approach; in the Czech case, all contacts were offered prophylactic doxycycline without seroconversion testing, while in the Swiss case, only observation for seroconversion was performed (23).

In summary, F. tularensis is capable of causing prosthetic joint infections, as shown in this study, but it is a rarely detected pathogen in this setting. Culture-positive PJIs have begun to be reported more in recent years, probably due to increasing numbers of implanted arthroplasties and the aging population (24), along with awareness of prolonged incubation time (25, 26) in initially culture-negative PJIs and a more active lifestyle including outdoor activities of people with joint replacements. Since F. tularensis is a fastidious growing organism, we hypothesize that multiple cases may have been missed and recommend considering tularemia together with other zoonotic pathogens in culture-negative PJIs with a positive histology or significantly elevated leukocytes in the synovial fluid. For that, we suggest prolonging the cultivation time up to 14 days, including aerobic cultures, and performing specific PCRs along with additional serological tests for zoonotic infections, including F. tularensis, in culture-negative PJIs. While advancements in the molecular biology techniques, such as new-generation sequencing (19, 27), may refine the proportion of PJIs without known pathogens, clinicians should consider both travel-related and endemic zoonotic infections in cases of true-culture- and PCR-negative PJIs and request specific antibody tests as an additional diagnostic step after blood and joint/tissue sampling for pathogens appropriate for their given geography and patient travel history.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge C. L. Cooper and H. Rawal for their willingness to provide additional details of their reported cases and V. Egli for updated follow-up data of the Zurich case.

No funding was received for this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tande AJ, Patel R. 2014. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:302–345. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper CL, Van Caeseele P, Canvin J, Nicolle LE. 1999. Chronic prosthetic device infection with Francisella tularensis. Clin Infect Dis 29:1589–1591. doi: 10.1086/313550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rawal H, Patel A, Moran M. 2017. Unusual case of prosthetic joint infection caused by Francisella tularensis. BMJ Case Rep 2017:bcr-2017-221258. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuen JC, Malotky MV. 2011. Francisella tularensis osteomyelitis of the hand following a cat bite: a case of clinical suspicion. Plast Reconstr Surg 128:37e–39e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182174626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader G, Al-Tarawneh M, Myers J. 2016. Review of prosthetic joint infection from Listeria monocytogenes. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 17:739–744. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlier C, Leclercq A, Cazenave B, Desplaces N, Travier L, Cantinelli T, Lortholary O, Goulet V, Le Monnier A, Lecuit M, L. monocytogenes Joint and Bone Infections Study Group. 2012. Listeria monocytogenes-associated joint and bone infections: a study of 43 consecutive cases. Clin Infect Dis 54:240–248. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Million M, Bellevegue L, Labussiere AS, Dekel M, Ferry T, Deroche P, Socolovschi C, Cammilleri S, Raoult D. 2014. Culture-negative prosthetic joint arthritis related to Coxiella burnetii. Am J Med 127:786.e7–786.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honnorat E, Seng P, Savini H, Pinelli PO, Simon F, Stein A. 2016. Prosthetic joint infection caused by Pasteurella multocida: a case series and review of literature. BMC Infect Dis 16:435. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1763-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JM, Folb J, Kalra S, Squire SB, Taegtmeyer M, Beeching NJ. 2016. Brucella melitensis prosthetic joint infection in a traveller returning to the UK from Thailand: case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis 14:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Hoek ML. 2013. Biofilms: an advancement in our understanding of Francisella species. Virulence 4:833–846. doi: 10.4161/viru.27023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis J, Oyston PC, Green M, Titball RW. 2002. Tularemia. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:631–646. doi: 10.1128/cmr.15.4.631-646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozanic M, Marecic V, Abu Kwaik Y, Santic M. 2015. The divergent intracellular lifestyle of Francisella tularensis in evolutionarily distinct host cells. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005208. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brock SR, Parmely MJ. 2017. Complement C3 as a prompt for human macrophage death during infection with Francisella tularensis strain SCHU S4. Infect Immun 85:e00424-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00424-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faber M, Heuner K, Jacob D, Grunow R. 2018. Tularemia in Germany–a re-emerging zoonosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:40. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berbari EF, Marculescu C, Sia I, Lahr BD, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Gullerud R, Osmon DR. 2007. Culture-negative prosthetic joint infection. Clin Infect Dis 45:1113–1119. doi: 10.1086/522184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erdem H, Ozturk-Engin D, Yesilyurt M, Karabay O, Elaldi N, Celebi G, Korkmaz N, Guven T, Sumer S, Tulek N, Ural O, Yilmaz G, Erdinc S, Nayman-Alpat S, Sehmen E, Kader C, Sari N, Engin A, Cicek-Senturk G, Ertem-Tuncer G, Gulen G, Duygu F, Ogutlu A, Ayaslioglu E, Karadenizli A, Meric M, Ulug M, Ataman-Hatipoglu C, Sirmatel F, Cesur S, Comoglu S, Kadanali A, Karakas A, Asan A, Gonen I, Kurtoglu-Gul Y, Altin N, Ozkanli S, Yilmaz-Karadag F, Cabalak M, Gencer S, Umut Pekok A, Yildirim D, Seyman D, Teker B, Yilmaz H, Yasar K, Inanc Balkan I, Turan H, Uguz M, et al. . 2014. Evaluation of tularaemia courses: a multicentre study from Turkey. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:O1042–O1051. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurin M, Pelloux I, Brion JP, Del Bano JN, Picard A. 2011. Human tularemia in France, 2006–2010. Clin Infect Dis 53:e133–e141. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 56:e1–e25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goswami K, Parvizi J, Maxwell Courtney P. 2018. Current recommendations for the diagnosis of acute and chronic PJI for hip and knee-cell counts, alpha-defensin, leukocyte esterase, next-generation sequencing. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 11:428–438. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9513-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sendi P, Zimmerli W. 2012. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections in clinical practice. Int J Artif Organs 35:913–922. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mühlhofer HM, Pohlig F, Kanz KG, Lenze U, Lenze F, Toepfer A, Kelch S, Harrasser N, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Schauwecker J. 2017. Prosthetic joint infection development of an evidence-based diagnostic algorithm. Eur J Med Res 22:8. doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0245-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomaso H, Hotzel H, Otto P, Myrtennas K, Forsman M. 2017. Antibiotic susceptibility in vitro of Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica isolates from Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2539–2543. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller PM, Bruderer V, Muller F. 2016. Restricted identification of clinical pathogens categorized as biothreats by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 54:816. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03250-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Pozo JL, Patel R. 2009. Clinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic joints. N Engl J Med 361:787–794. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0905029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossard DA, Ledergerber B, Zingg PO, Gerber C, Zinkernagel AS, Zbinden R, Achermann Y. 2016. Optimal length of cultivation time for isolation of Propionibacterium acnes in suspected bone and joint infections is more than 7 days. J Clin Microbiol 54:3043–3049. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01435-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schäfer P, Fink B, Sandow D, Margull A, Berger I, Frommelt L. 2008. Prolonged bacterial culture to identify late periprosthetic joint infection: a promising strategy. Clin Infect Dis 47:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/592973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarabichi M, Shohat N, Goswami K, Alvand A, Silibovsky R, Belden K, Parvizi J. 2018. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: the potential of next-generation sequencing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 100:147–154. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]