Key Points

Question

What are the harms, advantages, and costs associated with alternative guidelines for examining patients with hematuria?

Findings

In a microsimulation modeling study of a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 adults with hematuria, uniform computed tomography scanning appeared to be associated with more than 500 secondary cancers from imaging-associated radiation exposure and was approximately twice the cost of alternative approaches.

Meaning

The balance of harms, advantages, and costs of hematuria evaluation may be optimized with risk stratification and more selective application of diagnostic testing in general and computed tomography imaging in particular.

This microsimulation modeling study evaluates the current guidelines for testing hematuria in adults, comparing the recommended procedures, outcomes, cancer detection rates, costs, advantages, and risks associated with each.

Abstract

Importance

Existing recommendations for the diagnostic testing of hematuria range from uniform evaluation of varying intensity to patient-level risk stratification. Concerns have been raised about not only the costs and advantages of computed tomography (CT) scans but also the potential harms of CT radiation exposure.

Objective

To compare the advantages, harms, and costs associated with 5 guidelines for hematuria evaluation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A microsimulation model was developed to assess each of the following guidelines (listed in order of increasing intensity) for initial evaluation of hematuria: Dutch, Canadian Urological Association (CUA), Kaiser Permanente (KP), Hematuria Risk Index (HRI), and American Urological Association (AUA). Participants comprised a hypothetical cohort of patients (n = 100 000) with hematuria aged 35 years or older. This study was conducted from August 2017 through November 2018.

Exposures

Under the Dutch and CUA guidelines, patients received cystoscopy and ultrasonography if they were 50 years or older (Dutch) or 40 years or older (CUA). Under the KP and HRI guidelines, patients received different combinations of cystoscopy, ultrasonography, and CT urography or no evaluation on the basis of risk factors. Under the AUA guidelines, all patients 35 years or older received cystoscopy and CT urography.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Urinary tract cancer detection rates, radiation-induced secondary cancers (from CT radiation exposure), procedural complications, false-positive rates per 100 000 patients, and incremental cost per additional urinary tract cancer detected.

Results

The simulated cohort included 100 000 patients with hematuria, aged 35 years or older. A total of 3514 patients had urinary tract cancers (estimated prevalence, 3.5%; 95% CI, 3.0%-4.0%). The AUA guidelines missed detection for the fewest number of cancers (82 [2.3%]) compared with the detection rate of the HRI (116 [3.3%]) and KP (130 [3.7%]) guidelines. However, the simulation model projected 108 (95% CI, 34-201) radiation-induced cancers under the KP guidelines, 136 (95% CI, 62-229) under the HRI guidelines, and 575 (95% CI, 184-1069) under the AUA guidelines per 100 000 patients. The CUA and Dutch guidelines missed detection for a larger number of cancers (172 [4.9%] and 251 [7.1%]) but had 0 radiation-induced secondary cancers. The AUA guidelines cost approximately double the other 4 guidelines ($939/person vs $443/person for Dutch guidelines), with an incremental cost of $1 034 374 per urinary tract cancer detected compared with that of the HRI guidelines.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this simulation study, uniform CT imaging for patients with hematuria was associated with increased costs and harms of secondary cancers, procedural complications, and false positives, with only a marginal increase in cancer detection. Risk stratification may optimize the balance of advantages, harms, and costs of CT.

Introduction

Long recognized as a transformative innovation,1 advanced imaging has come under increased scrutiny. Payments for imaging have seen disproportionate growth,2 and up to half of all imaging studies ordered in the United States may be unnecessary.3 Reflecting this tension and despite the intentionally broad scope of the initiative, most of the initial Choosing Wisely campaign’s recommendations involved medical imaging.4 Furthermore, the long-term harms of radiation exposure are gaining more recognition, given evidence of the association between doses in the range of common computed tomography (CT) scans and increased risk for developing cancer in the future.5,6 Compounding the tripling volume of CT procedures in the United States during the past 2 decades to more than 85 million in 20112,7 are the inconsistency in radiation dose per examination and the facility-level variation in dose up to 13-fold.8,9,10

Recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation of hematuria provide an instructive frame of reference within which to consider the advantages, harms, and costs associated with CT. Hematuria is prevalent,11 and nearly 2 million Americans annually are referred to urologists for this finding.12 Current guidelines emphasize a structured evaluation that includes cystoscopy and imaging to rule out urinary tract malignancy, although the threshold for referral and the recommended imaging modality remain uncertain given the limitations in the evidence.13 Given the prevalence, differing recommendations may result in considerable variation in population-level costs14 and patient burden from downstream sequelae.15

Previous cost-effectiveness analyses have suggested that substantial incremental costs and minimal advantages are associated with the substitution of CT for ultrasonography.14,16 Although provocative, these studies have important limitations. First, asymptomatic microscopic hematuria, the focus of these analyses, has a relatively low pretest probability for cancer. Previous publications, including one that serves as a basis for these other studies’ estimates,17 have demonstrated that nearly 20% of referred patients may have a history of gross hematuria, which is associated with higher cancer risk by an order of magnitude. Second, one study modeled renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and upper-tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) as a composite outcome14 despite the differences in CT and ultrasonography for these diagnoses, and the other study assumed perfect sensitivity for CT.16 Third, although the authors of these studies have expressed concerns about the potential harms of radiation exposure from CT scans, as noted elsewhere,18,19,20 real-world variation in dose has not been considered. Multiphase CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis has been associated with not only the highest median dose but also the broadest range of dose and, in turn, the highest adjusted lifetime-attributable risk for cancer among common CT protocols.8

Against this backdrop, we used microsimulation modeling to compare the advantages, harms, and costs associated with different guidelines for hematuria evaluation. We included in the simulated population patients with both gross and microscopic hematuria, considering the detection of upper-tract cancers as discrete entities and accounting for the variation of CT dose in real-world practice.

Methods

We developed a patient-level microsimulation model using TreeAge Pro (TreeAge Software Inc) to compare 5 guidelines for the initial diagnostic evaluation of hematuria. We projected downstream outcomes and costs for a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 adults with hematuria. A detailed schematic of the model is presented in eFigure 1A to 1G in the Supplement. We used test-specific characteristics to compare cancer detection rates, false-positive results, radiation-induced secondary cancers, procedural complications, and costs per patient. This study was conducted from August 2017 through November 2018. Approval from an institutional review board was not needed because this study was a computer simulation based on published estimates in the literature.

We modeled data on patients’ age, sex, and presence and type of urinary tract cancer (bladder, RCC, or UTUC) from the 2 largest prospective hematuria cohort studies (1 from the United States,17 and 1 from the United Kingdom21) involving a total of 6363 patients (Table 1). We obtained distributions of other risk factors (smoking status and history of gross hematuria) from the US study (n = 4414).17 We constrained the simulation to exclude patients with a history of contrast allergy or renal impairment, as these conditions may be a factor in the selection of imaging modality.22 We validated model performance by comparing model-estimated cancer rates with those from a meta-analysis of 32 hematuria evaluation studies.22

Table 1. Model Input Variables.

| Characteristic | Base Case Value (Range)a | Distributionb | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 0.55 (0.46-0.65) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Men, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.08 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.13 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.21 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.24 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.33 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Women, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.12 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.18 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.27 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.21 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.22 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Probability of urinary tract cancer | |||

| Men, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.02 (0-0.04) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.03 (0.01-0.05) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.07 (0.03-0.11) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.10 (0.06-0.14) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.15 (0.08-0.19) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Women, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0 (0-0.02) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.01 (0-0.01) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.02 (0-0.04) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.05 (0.01-0.11) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.10 (0.03-0.17) | β | Loo et al,17 2013; Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Type of urinary tract cancer | |||

| Men with bladder cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.89 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.71 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.80 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.85 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.85 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Men with UTUC, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.02 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.03 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.03 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Men with RCC, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.11 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0.29 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.18 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.11 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.12 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Women with bladder cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 1.00 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.80 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.88 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.91 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Women with UTUC, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.04 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Women with RCC, age, y | |||

| <40 | 1.00 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 40-49 | 0 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 50-59 | 0.20 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| 60-69 | 0.12 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| ≥70 | 0.05 | Dirichlet | Edwards et al,21 2006 |

| Smoking history | |||

| Probability of cancer given smoking history | |||

| Men | 0.06 | β | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Women | 0.02 | β | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Gross hematuria history in the past 6 mo | |||

| Probability of cancer given gross hematuria history | |||

| Men | 0.10 | β | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Women | 0.05 | β | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Patients with >25 RBC per HPF | |||

| Men with cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.11 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 40-49 | 0.16 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 50-59 | 0.15 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 60-69 | 0.11 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| ≥70 | 0.48 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Men without cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.25 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 40-49 | 0.27 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 50-59 | 0.09 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 60-69 | 0.13 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| ≥70 | 0.25 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Women with cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.14 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 40-49 | 0.14 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 50-59 | 0.14 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 60-69 | 0.19 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| ≥70 | 0.38 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Women without cancer, age, y | |||

| <40 | 0.23 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 40-49 | 0.30 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 50-59 | 0.13 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| 60-69 | 0.13 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| ≥70 | 0.21 | Dirichlet | Loo et al,17 2013 |

| Test characteristics | |||

| Ultrasonography scan | |||

| Sensitivity | |||

| RCC | 0.91 (0.86-0.96)c | β | Aslaksen et al,24 1990 |

| UTUC | 0.71 (0.67-0.75) | β | Edwards et al,21 2006; Datta et al,252002; Unsal et al,26 2011 |

| Specificity | |||

| RCC | 0.99 (0.94-1.00)c | β | Aslaksen et al,24 1990 |

| UTUC | 0.90-1.00 | Uniform | An assumption |

| Flexible cystoscopy | |||

| Bladder cancer | |||

| Sensitivity | 0.98 (0.94-0.99) | β | Blick et al,65 2012 |

| Specificity | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | β | Blick et al,65 2012 |

| CT urography | |||

| Sensitivity | |||

| RCC | 0.96 (0.88-1.00) | β | Chlapoutakis et al,27 2010 |

| UTUC | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) | β | Fritz et al,28 2006 |

| Specificity | |||

| RCC | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | β | Chlapoutakis et al,27 2010 |

| UTUC | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) | β | Li et al,29 2008 |

| Effective radiation dose (range), mSv | 31 (6.4-90) | Triangular | Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| 2017 costs per patient, mean (SD), US$ | |||

| Renal ultrasonography; CPT/HCPCS code: 76770 | 145 (78) | γ | CMS,39 2017 |

| Flexible cystoscopy; CPT/HCPCS code: 52000 | 570 (516) | γ | CMS,39 2017 |

| CT urography; CPT/HCPCS code: 74178 | 371 (228) | γ | CMS,39 2017 |

| Procedural complications, % (95% CI) | |||

| Dysuria after cystoscopy | 11 (10-12) | β | Stav et al,30 2004 |

| UTI after cystoscopy | 1.9 (0-3) | β | Herr,31 2015 |

| Contrast-induced nephropathy | 4 (1-19)d | β | Golshahi et al,32 2014; Silver et al,33 2015; Marenzi et al,34 2004 |

| Allergy to contrast media | 0.6 (0.57-0.63)c | β | Silverman et al,35 2009 |

| CT radiation-induced cancers | |||

| LAR of solid cancer incidence, y | |||

| 35-40 | 0.36 | Dirichlet | Shuryak et al,36 2010; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| 40-49 | 0.40 | Dirichlet | Shuryak et al,36 2010; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| 50-59 | 0.42 | Dirichlet | Shuryak et al,36 2010; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| 60-69 | 0.38 | Dirichlet | Shuryak et al,36 2010; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| ≥70e | 0.26 | Dirichlet | Shuryak et al,36 2010; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| LAR of leukemia incidence, % | |||

| Female age, y | |||

| 35-49 | 0.016 | γ | National Research Council et al,6 2006; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| ≥50 | 0.016 | γ | National Research Council et al,6 2006; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| Male age, y | |||

| 35-49 | 0.022 | γ | National Research Council et al,6 2006; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

| ≥50 | 0.022 | γ | National Research Council et al,6 2006; Smith-Bindman et al,8 2009 |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CT, computed tomography; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; HPF, high-powered field; LAR, lifetime attributable risk; mSv, millisievert; RBC, red blood cells; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UTI, urinary tract infection; UTUC, upper-tract urothelial carcinoma.

Values in parentheses represent upper and lower bounds used in sensitivity analyses and are based on 95% CIs obtained from the literature unless noted otherwise.

In multiway probabilistic sensitivity analysis, model variables were altered randomly by the following distributions, accounting for data characteristics and skewness: β (allowing only values between 0 and 1), γ (allowing only nonnegative values), Dirichlet (multivariate generalization of the β distribution for multinomial data), uniform (defined by the minimum and maximum values for the variable), or triangular distribution (describing the expected minimum, maximum, and modal values).40,41

Values in parentheses represent 5% SD of the mean.

Values in parentheses represent a range of plausible values obtained from the literature.

The excess cancer risk in the 70 years-or-older age group was calculated as a weighted mean of the risks for the 70-to-79 years and 80 years-or-older age groups using the 2015 population age distribution from the US Census Bureau.66

We simulated the clinical encounter and sequelae for the model cohort (n = 100 000) under each of 5 evaluation guidelines (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Under the Dutch and Canadian (Canadian Urological Association [CUA]) guidelines, eligible patients (50 years or older or 40 years or older, respectively) received cystoscopy and ultrasonography.18,19 Under the guidelines of Kaiser Permanente (KP), a large integrated health care system in the United States, only patients with a history of gross hematuria received CT and cystoscopy; smokers, males, and anyone 50 years or older received cystoscopy and ultrasonography, whereas nonsmoking female patients younger than 50 years did not undergo any evaluation.23 Under the Hematuria Risk Index (HRI) guidelines, we calculated HRI scores (eMethods in the Supplement) for each patient to determine their evaluation method (none for low-risk, cystoscopy and ultrasonography for moderate-risk, and cystoscopy and CT for high-risk patients).17 Under the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines, all patients 35 years or older received cystoscopy and CT.22

Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of cystoscopy, ultrasonography, and CT for each cancer type (bladder, RCC, or UTUC) as well as rates of test-specific complications (urinary tract infection from cystoscopy, CT contrast-induced nephropathy, and contrast allergy) were obtained from published sources (Table 1).17,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35

We modeled the lifetime-attributable risks of cancer from CT radiation exposure as a function of radiation dose and age at exposure.6,36 Each examination was modeled as a factor in radiation exposure of 6.4 to 90 millisieverts (mSv), reflecting the observed range of effective dose for the multiphase abdomen and pelvis CT imaging.8 We performed a sensitivity analysis around effective dose to characterize the plausible range using community-based data (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).37 Biological outcomes of the one-time CT radiation exposure were modeled over the patients’ lifetime using a study of radiation carcinogenesis that found increased risks after exposure in middle or older age.36 We used the reported age-specific estimates of excess lifetime risk of radiation-induced solid cancers and leukemia normalized for a dose of 0.1 gray (Gy) per 100 000 patients.6,36 Next, we adjusted the cancer risks by the mean effective dose (in mSv) for CT after converting it to absorbed dose (in Gy) using a radiation weighing factor of 1 for x-rays.36,38 The age-specific, dose-adjusted lifetime risks of radiation-induced cancer are reported in Table 1 and eTables 2 to 4 in the Supplement.

Costs were estimated from the US national payer (Medicare) perspective using 2017 US dollars and were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System for 2017, which reports the national mean outpatient payments based on the Ambulatory Payment Classification system (Table 1).39 We used the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System and Current Procedural Terminology codes to identify costs for each test. False-positive costs were estimated as costs of the initial diagnostic evaluation and did not include costs associated with downstream testing. Because we only included one-time costs associated with initial workup, we did not discount costs.

Cost-effectiveness and Sensitivity Analyses

We ranked the strategies in the 5 guidelines from least to most expensive and compared them sequentially in terms of cost per urinary tract cancer cases detected. We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of each strategy as the additional cost divided by the additional number of cancer cases detected compared with the next less expensive alternative, removing any dominated strategies from the next sequential comparison.40

We altered all input variables simultaneously in probabilistic sensitivity analysis with 10 000 iterations to assess the implication of uncertainty for the model using CIs, ranges, or SDs from the published literature (Table 1).6,8,17,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39 When such values were unavailable, we evaluated uncertainty by setting plausible bounds to ±5% of base case values. We used β distribution for binomial data, including probabilities and test characteristics (sensitivity and specificity); γ distribution for costs; Dirichlet distribution for multinomial data; and triangular distribution for the effective radiation dose (Table 1), following best practices.41

Results

The simulated cohort included 100 000 patients. A total of 3514 (3.5%) of these patients had urinary tract cancers (95% CI, 3.0%-4.0%), an estimated prevalence rate similar to the malignancy rate of 4.0% from a meta-analysis of 32 studies of initial hematuria evaluation.22 Of these cancers, 2978 (84.7%; 95% CI, 2490-3500) were bladder cancer, 443 (12.6%; 95% CI, 280-630) were RCC, and 93 (2.6%; 95% CI, 30-180) were UTUC.

Advantages and Harms

Table 2 shows the expected health and economic outcomes associated with each guideline (sex- and age-specific results are in eTable 5 in the Supplement). The Dutch guidelines had the lowest cancer detection rate of 92.9% (n = 3263). Cancer detection rates increased in parallel with greater intensity of evaluation to 95.1% (n = 3343) for the CUA guidelines, 96.3% (n = 3385) for the KP guidelines, 96.7% (n = 3399) for the HRI guidelines, and 97.7% (n = 3432) for the AUA guidelines.

Table 2. Expected Health and Economic Outcomes for Each of the Assessed Guidelinesa .

| Outcome | Mean No. (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch Guidelines19 | CUA Guidelines18 | KP Guidelines23 | HRI Guidelines17,67 | AUA Guidelines22 | ||||||

| Cancer Detected | Cancer Missed | Cancer Detected | Cancer Missed | Cancer Detected | Cancer Missed | Cancer Detected | Cancer Missed | Cancer Detected | Cancer Missed | |

| Simulated primary cancerb | ||||||||||

| Total urinary tract cancers | ||||||||||

| 3514 (2980-4090) | 3263 (2260-3240) | 251 (140-400) | 3343 (2300-3290) | 172 (100-300) | 3385 (2550-3600) | 130 (60-270) | 3399 (2740-3750) | 116 (50-250) | 3432 (2760-3850) | 82 (0-80) |

| Bladder cancer | ||||||||||

| 2978 (2490-3500) | 2838 (2300-3300) | 141 (70-380) | 2906 (2340-3350) | 72 (40-340) | 2907 (2350-3350) | 71 (40-330) | 2907 (2350-3350) | 71 (40-330) | 2918 (2420-3440) | 60 (0-230) |

| RCC | ||||||||||

| 443 (280-630) | 360 (220-530) | 82 (20-160) | 371 (230-540) | 72 (20-140) | 397 (250-570) | 46 (10-100) | 404 (250-580) | 39 (0-100) | 425 (270-610) | 19 (0-70) |

| UTUC | ||||||||||

| 93 (30-180) | 65 (10-140) | 28 (0-70) | 65 (10-140) | 28 (0-70) | 80 (20-160) | 13 (0-40) | 87 (20-170) | 6 (0-30) | 89 (30-180) | 5 (0-20) |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||||||||

| UTI from cystoscopy | 1179 (712-1762) | 1230 (744-1839) | 1260 (762-1833) | 1260 (762-1833) | 1902 (1152-2839) | |||||

| Dysuria | 6820 (3517-11 054) | 7114 (3671-11 530) | 7289 (3761-11 811) | 7289 (3761-11 811) | 11 003 (5682-17 824) | |||||

| False-positive cases (CT, ultrasonography, or cystoscopy) | 6452 (4040-9410) | 6740 (4220-9820) | 9099 (6270-12 450) | 13 811 (10 800-17 170) | 22 189 (17 520-27 370) | |||||

| CT-associated events | ||||||||||

| CT allergy | NA | NA | 135 (50-262) | 151 (66-278) | 618 (228-1197) | |||||

| Contrast nephropathy | NA | NA | 898 (247-1933) | 1009 (358-2044) | 4114 (1138-8830) | |||||

| Radiation-induced cancers | ||||||||||

| Lifetime cancers | NA | NA | 108 (34-201) | 136 (62-229) | 575 (184-1069) | |||||

| Cost, US$ | ||||||||||

| Total | 44 254 (8112-129 435) | 46 163 (8466-135 063) | 51 920 (12 546-143 170) | 59 751 (13 434-153 739) | 93 886 (21 670-237 374) | |||||

| False-positivec | 2426 (177-8071) | 2535 (185-8427) | 3615 (363-11 262) | 5862 (747-17 013) | 9365 (1212-27 015) | |||||

Abbrevations: AUA, American Urological Association; CT, computed tomography; CUA, Canadian Urological Association; KP, Kaiser Permanente; HRI, Hematuria Risk Index; NA, not applicable; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UTI, urinary tract infection; UTUC, upper-tract urothelial carcinoma.

The simulation included 100 000 virtual patients, and 10 000 data points were sampled from the prespecified distribution of each input variable.

The sum of detected and missed cancer cases may differ from the total simulated primary cancers by 1 SD because of rounding.

Costs of false-positive test results from cystoscopy, ultrasonography, and/or CT in initial episode of care.

The CUA and Dutch guidelines had 0 radiation-associated cancers from CT because both recommend against CT in first-line evaluation. The model projected 108 (95% CI, 34-201) radiation-induced cancers under the KP guidelines, 136 (95% CI, 62-229) under the HRI guidelines, and 575 (95% CI, 184-1069) under the AUA guidelines per 100 000 patients. Sensitivity analyses that explored a broader range (3.5-144 mSv) of observed multiphase CT doses from the community37 were associated with an estimate of 782 per 100 000 radiation-induced cancers for the uniform approach (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The age breakdown of secondary solid cancers and leukemias is detailed in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

Additional harms associated with more intensive workup included more false-positive cases: 22 189 (95% CI, 17 520-27 370) for the AUA guidelines compared with 13 811 (95% CI, 10 800-17 170) for the HRI, 9099 (95% CI, 6270-12 450) for the KP, 6740 (95% CI, 4220-9820) for the CUA, and 6452 (95% CI, 4040-9410) for the Dutch guidelines. Total short-term procedural complications (CT allergy, contrast nephropathy, dysuria, and urinary tract infection) were also greatest for the AUA guidelines at 17 637 compared with 9709 for the HRI, 9582 for the KP, 8344 for the CUA, and 7999 for the Dutch guidelines.

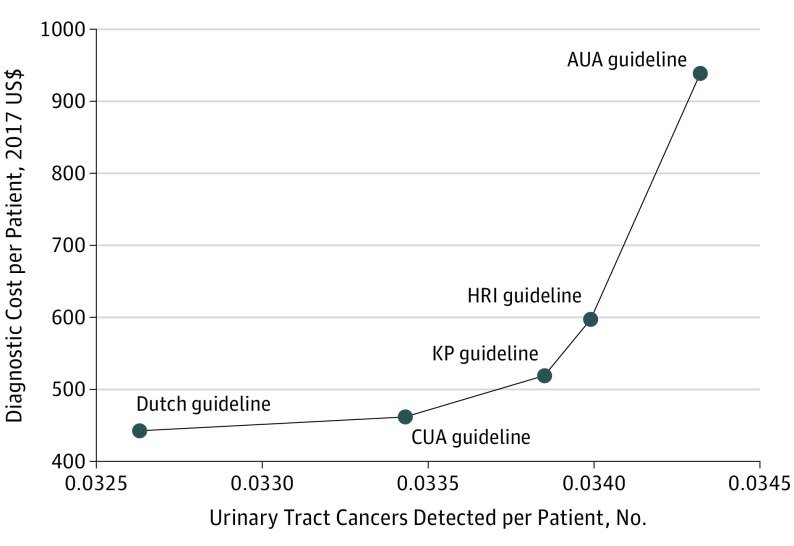

Cost-effectiveness Analysis

The Dutch guidelines were associated with the lowest ($443) and the AUA guidelines with the highest ($939) per-person costs. The relative costs were approximately twice as high using the AUA guidelines compared with all other strategies. Results from the base case cost-effectiveness analysis are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. Decreasing the eligible age for evaluation with cystoscopy plus ultrasonography from 50 years or older (Dutch) to 40 years or older (CUA) had an incremental cost of $23 864 per additional cancer detected. Compared with the CUA guidelines, the KP guidelines had an ICER of $137 063 per additional cancer detected. The HRI guidelines had an ICER of $559 378 per additional cancer detected compared with the KP ICER. The AUA guidelines had an ICER of $1 034 374 per additional cancer detected compared with HRI.

Table 3. Incremental Cost per Hematuria-Associated Urinary Tract Cancer Case Detected .

| Guidelines | Cost in Millions, US$ | Cancer Cases Detected, No. | Incremental Cancer Cases Detected, No. | ICER (Cost per Additional Cancer Case Detected), US$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Incremental | ||||

| Dutch19 | 44.3 | 1 [Reference] | 3263 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| CUA18 | 46.2 | 1.9 | 3343 | 80 | 23 864 |

| KP23 | 51.9 | 5.7 | 3385 | 42 | 137 063 |

| HRI17,67 | 59.8 | 7.9 | 3399 | 14 | 559 378 |

| AUA22 | 93.9 | 34.1 | 3432 | 33 | 1 034 374 |

Abbreviations: AUA, American Urological Association; CUA, Canadian Urological Association; HRI, Hematuria Risk Index; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (the additional cost divided by the additional advantage of a strategy compared with the next less expensive alternative); KP, Kaiser Permanente.

Figure 1. Cost-effectiveness Efficiency Frontier for Hematuria Guidelines Under Consideration.

AUA indicates American Urological Association; CUA, Canadian Urological Association; HRI, Hematuria Risk Index; and KP, Kaiser Permanente.

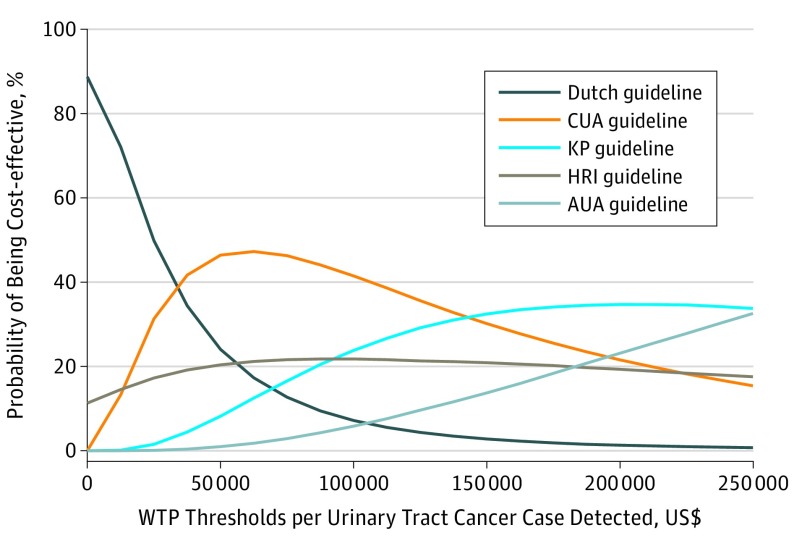

The results from the probabilistic sensitivity analysis using 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations are presented as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (Figure 2), which show the probability that each set of guidelines would be considered cost-effective for various willingness-to-pay thresholds.41 Given that the health outcomes of interest are in natural units (cancers detected) rather than utility values that can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years, no commonly accepted cost-effectiveness threshold exists against which to compare each set of guidelines.40,42 The probability of the AUA guidelines being cost-effective gradually increased with the willingness-to-pay threshold but remained lower than for other strategies across a wide range of willingness-to-pay thresholds up to $250 000 per additional cancer detected.

Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness Acceptability Curves (CEACs) of Initial Evaluation of Hematuria From a US Medicare Payer Perspective.

Each CEAC represents the probability that a strategy is cost-effective under different willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds for an additional hematuria-associated urinary tract cancer case detected. No commonly accepted cost-effectiveness threshold exists against which to compare the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios expressed as incremental cost per additional urinary tract cancer detected; therefore, a wide range of possible WTP thresholds was plotted. AUA indicates American Urological Association; CUA, Canadian Urological Association; HRI, Hematuria Risk Index; and KP, Kaiser Permanente.

Discussion

Hematuria is a common clinical finding for which the optimal approach is uncertain, particularly with regard to the role of CT imaging.13 A health technology assessment identified 79 hematuria diagnostic algorithms, none of which had been formally evaluated in terms of the algorithm’s association with patient outcomes.43 In this study, we examined the trade-offs of advantages, harms, and costs across 5 representative guidelines for hematuria evaluation. The findings are strengthened by the use of a microsimulation model to capture the heterogeneity of the target population. Specifically, we made the assumption of a subgroup with gross hematuria, reflecting real-world practice,17 in contrast to previous studies that focused on the lower-risk subset of patients with asymptomatic microhematuria.14,16 Although most clinicians view microscopic and gross hematuria differently and patients with microhematuria gain less advantage from testing, much of the evidence supporting current guidelines conflates these entities.44 The approach we developed permits the assessment of the relative advantages, harms, and costs of different testing strategies within and across these patient subgroups (Table 2). Differences in bladder cancer diagnostic yield reflect a variety of recommended age thresholds for uniform evaluation by cystoscopy (Dutch, CUA, and AUA) and strategies omitting cystoscopy for lowest-risk patients, such as nonsmoking female patients younger than 50 years with microhematuria (KP and HRI, consistent with recommendations from other organizations45).

With regard to imaging, we examined comparators in which all patients, even those with gross hematuria, received ultrasonography (CUA, 40 years or older; Dutch, 50 years or older). The remaining comparators illustrated trade-offs of advantages, harms, and costs associated with the omission of imaging for the lowest-risk patients (KP and HRI) and substitution of CT for ultrasonography for those with gross hematuria (KP) or multiple risk factors, including gross hematuria (HRI), and a comparator in which all patients, even those with microhematuria, received CT (AUA). Recommendations against uniform CT in this context explicitly cite concerns about costs and harms, in particular radiation exposure.18,19,20 The findings support these concerns, as the strategy of CT for all patients was associated with not only substantially greater costs but also a larger number of false-positive results, procedural complications, and—considering the wide variation in CT dose in the real world—an estimated risk of radiation-induced future cancer for 1 in 174 patients tested.

These findings support the concepts that most patients are at below-average risk and may have less-than-average advantage from treatment46 and that as intensity increases beyond an optimal level, the growth in advantages slows while harms and costs rise rapidly.47 Given the imperfect sensitivity of diagnostic testing, no guidelines detected all cancers. The most intensive guidelines missed 82 (2.3%) of 3514 cases, with an estimated 575 additional future cancers associated with radiation from CT. Although our sources for variable estimation did not permit modeling of cancer stage and grade by site and risk group, and the advantage of early detection in this context was uncertain, most of the incremental additional cases detected with CT imaging were RCCs (Table 2). Although RCC was classically associated with the triad of flank pain, palpable mass, and gross hematuria,48 it is increasingly an incidental diagnosis,49 and concerns have been raised about overdiagnosis.50,51 The rate of RCC in this simulated population (443 [0.44%] of 100 000), drawn from the 2 largest series of hematuria evaluation, is comparable to the rate of renal procedures (0.57%) and nephrectomy (0.44%) in a recently published study of US Medicare patients undergoing thoracoabdominal CT imaging for all indications.52

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Our aim was to compare the trade-offs between representative contemporary recommendations, and we assumed 100% fidelity to a given set of guidelines in each simulation. Given the complex reality of clinical practice, these simulations should be considered a stylized comparison of different approaches. For example, the AUA guidelines recommend CT for all adults 18 years or older with 3 or more red blood cells per high-powered field on a single microscopic urinalysis,22 whereas other strategies not only have higher age thresholds for evaluation but also suggest a referral after multiple urinalyses with positive results.17,18,19,23,53 Our comparisons focused on the top-line recommendations of different guidelines, but future work might consider alternative diagnostic pathways, including magnetic resonance imaging, urinary cytological testing, or other optional adjuncts in this setting. Furthermore, although nearly 2 million US patients are referred to urologists annually for evaluation,12 the total population with hematuria is much larger. Multiple observational studies suggest that most patients with hematuria, including those with high-risk features,54 do not undergo timely evaluation with cystoscopy and imaging.55,56,57,58 Improving the value of care in this context may require addressing potentially larger problems of misallocation of testing resources, which can have greater welfare costs than overuse.59

In the United States, medically associated exposure to ionizing radiation has increased 6-fold in the past 3 decades,60 mostly owing to the rapid increase in CT imaging.5 The general consensus is that radiation from medical imaging is carcinogenic, but the exact magnitude of iatrogenic cancer risk remains uncertain. The most accepted model is the no-threshold linear risk model established by the Biologic Effects of Ionizing Radiation report.6 This model states that each increase in effective dose of radiation is accompanied by a linearly proportional increase in the risk of later malignancy and that no threshold exists at which the risk of cancer rises dramatically. We estimated 575 of 100 000 radiation-induced cancers in the uniform CT approach. These estimates were higher than those obtained in related work (149 of 100 000),16 which did not account for the wide dose variation in real-world practice. The implication of dose variation is underscored in our sensitivity analyses that explored the plausible range of variation in the community37 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). A framework of stewardship strategies61 could mitigate these risks, including restricting the population for whom CT imaging is recommended as well as developing interventions62 supporting proficient and consistent execution of best practices to reduce dose variation.

We estimated a large number of false-positive cases on the basis of test specificity. Our estimates for false-positive costs reflected only the testing in the initial encounter and not the additional downstream testing or procedures, accounting in part for the lower cost estimates in the model compared with estimates in previous related work.14 False positives are rarely reported in the hematuria diagnostic testing literature,15 and there is a paucity of data on the practice patterns in that context. We did not include estimates for incidental findings, which occurred in more than 30% of this type of CT imaging.63 Such findings may be associated with potentially unnecessary anxiety, patient and family burden,64 physical risks, and costs15 associated with additional testing or procedures.13 As such, the cost and harm estimates here should be viewed as conservative. Treatment for secondary cancers from radiation exposure, which have a case fatality rate of 50% or more,6 also carries harms and costs not included in this model; therefore, the total burden of risks attributable to CT is likely to be substantially greater.

Conclusions

Well-intentioned efforts may lead to the widespread dissemination of clinical practices before their safety and effectiveness are clearly understood. This model-based comparison of 5 different guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of hematuria suggests that, in addition to its substantial costs, the potential harms of the intensive application of uniform CT urography may outweigh the advantages of early diagnosis of urinary tract malignant neoplasms.

eMethods.

eFigure 1A. Depiction of the Decision Tree Model

eFigure 1B. Assignment of Patient Characteristics

eFigure 1C. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the AUA Guideline

eFigure 1D. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the KP Guideline

eFigure 1E. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the HRI Guideline

eFigure 1F. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the CUA Guideline

eFigure 1G. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the Dutch Guideline

eFigure 2. Sensitivity Analysis of CT Radiation-induced Cancer Cases Under Two Modeling Scenarios for Effective Radiation Dose Under the AUA, KP, and HRI Guidelines

eTable 1. Comparison of Different Evaluation Recommendations Under the Five Guidelines

eTable 2. Lifetime Attributable Risks of Solid Cancer and Death from Cancer Due to Radiation by Age at Exposure

eTable 3. BEIR VII (2006) Radiation Report Estimates: Number of Cases per 100 000 Persons of Mixed Ages Exposed to 0.1 Gy

eTable 4. BEIR VII (2006) Radiation Report Estimates: Lifetime Attributable Risk of Leukemia Incidence and Mortality per 100 000 Exposed Persons

eTable 5. Break-down of Expected Primary Detected and Missed Cancer Cases and Secondary Radiation-induced Cancer Cases (N = 100 000)

References

- 1.Fuchs VR, Sox HC Jr. Physicians’ views of the relative importance of thirty medical innovations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(5):30-42. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.5.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, et al. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2400-2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendee WR, Becker GJ, Borgstede JP, et al. Addressing overutilization in medical imaging. Radiology. 2010;257(1):240-245. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahesh M, Durand DJ. The Choosing Wisely campaign and its potential impact on diagnostic radiation burden. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(1):65-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography–an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Radiation Effects Research; Committee to Assess Health Risks From Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation. Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation BEIR VII Phase II. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.PS Net: Patient Safety Network. Radiation safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/27/radiation-safety. Accessed January, 2017.

- 8.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2078-2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith-Bindman R, Moghadassi M, Griffey RT, et al. Computed tomography radiation dose in patients with suspected urolithiasis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1413-1416. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith-Bindman R, Wang Y, Yellen-Nelson TR, et al. Predictors of CT radiation dose and their effect on patient care: a comprehensive analysis using automated data. Radiology. 2017;282(1):182-193. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohr DN, Offord KP, Owen RA, Melton LJ III. Asymptomatic microhematuria and urologic disease: a population-based study. JAMA. 1986;256(2):224-229. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380020086028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David SA, Patil D, Alemozaffar M, Issa MM, Master VA, Filson CP. Urologist use of cystoscopy for patients presenting with hematuria in the United States. Urology. 2017;100:20-26. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen M, Qaseem A; High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians . Hematuria as a marker of occult urinary tract cancer: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):488-497. doi: 10.7326/M15-1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern JA, Chughtai B, Ghomrawi H. Cost-effectiveness of common diagnostic approaches for evaluation of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):800-807. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai WS, Ellenburg J, Lockhart ME, Kolettis PN. Assessing the costs of extraurinary findings of computed tomography urogram in the evaluation of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Urology. 2016;95:34-38. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yecies T, Bandari J, Fam M, Macleod L, Jacobs B, Davies B. Risk of radiation from computerized tomography urography in the evaluation of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. J Urol. 2018;200(5):967-972. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loo RK, Lieberman SF, Slezak JM, et al. Stratifying risk of urinary tract malignant tumors in patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(2):129-138. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wollin T, Laroche B, Psooy K. Canadian guidelines for the management of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults. Can Urol Assoc J. 2009;3(1):77-80. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Molen AJ, Hovius MC. Hematuria: a problem-based imaging algorithm illustrating the recent Dutch guidelines on hematuria. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):1256-1265. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loo R, Whittaker J, Rabrenivich V. National practice recommendations for hematuria: how to evaluate in the absence of strong evidence? Perm J. 2009;13(1):37-46. doi: 10.7812/TPP/08-083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards TJ, Dickinson AJ, Natale S, Gosling J, McGrath JS. A prospective analysis of the diagnostic yield resulting from the attendance of 4020 patients at a protocol-driven haematuria clinic. BJU Int. 2006;97(2):301-305. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. ; American Urological Association . Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6)(suppl):2473-2481. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser Permanente Southern California Standardized Hematuria Evaluation Clinical Reference [guideline]. Pasadena, CA: Southern California Permanente Medical Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aslaksen A, Halvorsen OJ, Göthlin JH. Detection of renal and renal pelvic tumours with urography and ultrasonography. Eur J Radiol. 1990;11(1):54-58. doi: 10.1016/0720-048X(90)90103-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datta SN, Allen GM, Evans R, Vaughton KC, Lucas MG. Urinary tract ultrasonography in the evaluation of haematuria–a report of over 1,000 cases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84(3):203-205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unsal A, Calişkan EK, Erol H, Karaman CZ. The diagnostic efficiency of ultrasound guided imaging algorithm in evaluation of patients with hematuria. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79(1):7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chlapoutakis K, Theocharopoulos N, Yarmenitis S, Damilakis J. Performance of computed tomographic urography in diagnosis of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma, in patients presenting with hematuria: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73(2):334-338. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritz GA, Schoellnast H, Deutschmann HA, Quehenberger F, Tillich M. Multiphasic multidetector-row CT (MDCT) in detection and staging of transitional cell carcinomas of the upper urinary tract. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(6):1244-1252. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Z-H, Gong D-X, Kong C-Z. CT urography in the detection and staging of renal pelvic and ureteral carcinoma. China J Mode Med. 2008;22:046 http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-ZXDY200822046.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stav K, Leibovici D, Goren E, et al. Adverse effects of cystoscopy and its impact on patients’ quality of life and sexual performance. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6(8):474-478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herr HW. The risk of urinary tract infection after flexible cystoscopy in patients with bladder tumor who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics. J Urol. 2015;193(2):548-551. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golshahi J, Nasri H, Gharipour M. Contrast-induced nephropathy; a literature review. J Nephropathol. 2014;3(2):51-56. doi: 10.12860/jnp.2014.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silver SA, Shah PM, Chertow GM, Harel S, Wald R, Harel Z. Risk prediction models for contrast induced nephropathy: systematic review. BMJ. 2015;351:h4395. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marenzi G, Lauri G, Assanelli E, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(9):1780-1785. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman SG, Leyendecker JR, Amis ES Jr. What is the current role of CT urography and MR urography in the evaluation of the urinary tract? Radiology. 2009;250(2):309-323. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuryak I, Sachs RK, Brenner DJ. Cancer risks after radiation exposure in middle age. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(21):1628-1636. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guite KM, Hinshaw JL, Ranallo FN, Lindstrom MJ, Lee FT Jr. Ionizing radiation in abdominal CT: unindicated multiphase scans are an important source of medically unnecessary exposure. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):756-761. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Food and Drug Administration. Radiation quantities and units. https://www.fda.gov/Radiation-EmittingProducts/RadiationEmittingProductsandProcedures/MedicalImaging/MedicalX-Rays/ucm115335.htm. Accessed August 2015.

- 39.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital outpatient PPS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/index.html. Updated March 8, 2019. Accessed November 4, 2017.

- 40.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision Modelling for Health Economic Evaluation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness–the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796-797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodgers M, Nixon J, Hempel S, et al. Diagnostic tests and algorithms used in the investigation of haematuria: systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(18):iii-iv, xi-259. doi: 10.3310/hta10180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults (2016). American Urological Association website. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/asymptomatic-microhematuria-(amh)-guideline. Published 2012. Accessed November 2017.

- 45.Committee on Gynecologic Practice, American Urological Society Committee opinion No. 703 summary: asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):1153-1154. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vickers AJ, Kent DM. The Lake Wobegon effect: why most patients are at below-average risk. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(12):866-867. doi: 10.7326/M14-2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris RP, Wilt TJ, Qaseem A; High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians . A value framework for cancer screening: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):712-717. doi: 10.7326/M14-2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2477-2490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luciani LG, Cestari R, Tallarigo C. Incidental renal cell carcinoma-age and stage characterization and clinical implications: study of 1092 patients (1982-1997). Urology. 2000;56(1):58-62. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00534-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605-613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson DC, Vukina J, Smith AB, et al. Preoperatively misclassified, surgically removed benign renal masses: a systematic review of surgical series and United States population level burden estimate. J Urol. 2015;193(1):30-35. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welch HG, Skinner JS, Schroeck FR, Zhou W, Black WC. Regional variation of computed tomographic imaging in the United States and the risk of nephrectomy. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):221-227. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson J, Fawcett D, Feehally J, Goldberg L, Kelly J, MacTier R; on behalf of the Renal Association ad British Association of Urological Surgeons. Joint consensus statement on the initial assessment of haematuria. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/News/haematuria_consensus_guidelines_July_2008.pdf. Published July 2008. Accessed November 2017.

- 54.Elias K, Svatek RS, Gupta S, Ho R, Lotan Y. High-risk patients with hematuria are not evaluated according to guideline recommendations. Cancer. 2010;116(12):2954-2959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bassett JC, Alvarez J, Koyama T, et al. Gender, race, and variation in the evaluation of microscopic hematuria among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):440-447. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3116-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nieder AM, Lotan Y, Nuss GR, et al. Are patients with hematuria appropriately referred to urology? a multi-institutional questionnaire based survey. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(5):500-503. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buteau A, Seideman CA, Svatek RS, et al. What is evaluation of hematuria by primary care physicians? use of electronic medical records to assess practice patterns with intermediate follow-up. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(2):128-134. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedlander DF, Resnick MJ, You C, et al. Variation in the intensity of hematuria evaluation: a target for primary care quality improvement. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):633-640.e611. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenbaum L. The less-is-more crusade - are we overmedicalizing or oversimplifying? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(24):2392-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1713248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mettler FA Jr, Bhargavan M, Faulkner K, et al. Radiologic and nuclear medicine studies in the United States and worldwide: frequency, radiation dose, and comparison with other radiation sources–1950-2007. Radiology. 2009;253(2):520-531. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532082010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Durand DJ, Lewin JS, Berkowitz SA. Medical-imaging stewardship in the accountable care era. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1691-1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1507703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Demb J, Chu P, Nelson T, et al. Optimizing radiation doses for computed tomography across institutions: dose auditing and best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):810-817. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lumbreras B, Donat L, Hernández-Aguado I. Incidental findings in imaging diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(988):276-289. doi: 10.1259/bjr/98067945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ray KN, Chari AV, Engberg J, Bertolet M, Mehrotra A. Opportunity costs of ambulatory medical care in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(8):567-574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blick CG, Nazir SA, Mallett S, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic strategies for bladder cancer using computed tomography (CT) urography, flexible cystoscopy and voided urine cytology: results for 778 patients from a hospital haematuria clinic. BJU Int. 2012;110(1):84-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.20105 population estimates, American FactFinder. US Census Bureau website. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Published June 2016. Accessed November 2017.

- 67.Yard DH. A hematuria risk index: interview with Ronald Loo, MD. Renal & Urology News website. https://www.renalandurologynews.com/home/departments/expert-qa/a-hematuria-risk-index-interview-with-ronald-loo-md/. Published November 13, 2013. Accessed November 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eFigure 1A. Depiction of the Decision Tree Model

eFigure 1B. Assignment of Patient Characteristics

eFigure 1C. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the AUA Guideline

eFigure 1D. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the KP Guideline

eFigure 1E. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the HRI Guideline

eFigure 1F. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the CUA Guideline

eFigure 1G. Adult Hematuria Workup Algorithm Under the Dutch Guideline

eFigure 2. Sensitivity Analysis of CT Radiation-induced Cancer Cases Under Two Modeling Scenarios for Effective Radiation Dose Under the AUA, KP, and HRI Guidelines

eTable 1. Comparison of Different Evaluation Recommendations Under the Five Guidelines

eTable 2. Lifetime Attributable Risks of Solid Cancer and Death from Cancer Due to Radiation by Age at Exposure

eTable 3. BEIR VII (2006) Radiation Report Estimates: Number of Cases per 100 000 Persons of Mixed Ages Exposed to 0.1 Gy

eTable 4. BEIR VII (2006) Radiation Report Estimates: Lifetime Attributable Risk of Leukemia Incidence and Mortality per 100 000 Exposed Persons

eTable 5. Break-down of Expected Primary Detected and Missed Cancer Cases and Secondary Radiation-induced Cancer Cases (N = 100 000)