Summary

Colletotrichum lentis causes anthracnose, which is a serious disease on lentil and can account for up to 70% crop loss. Two pathogenic races, 0 and 1, have been described in the C. lentis population from lentil.

To unravel the genetic control of virulence, an isolate of the virulent race 0 was sequenced at 1481‐fold genomic coverage. The 56.10‐Mb genome assembly consists of 50 scaffolds with N 50 scaffold length of 4.89 Mb. A total of 11 436 protein‐coding gene models was predicted in the genome with 237 coding candidate effectors, 43 secondary metabolite biosynthetic enzymes and 229 carbohydrate‐active enzymes (CAZymes), suggesting a contraction of the virulence gene repertoire in C. lentis.

Scaffolds were assigned to 10 core and two minichromosomes using a population (race 0 × race 1, n = 94 progeny isolates) sequencing‐based, high‐density (14 312 single nucleotide polymorphisms) genetic map. Composite interval mapping revealed a single quantitative trait locus (QTL), qClVIR‐11, located on minichromosome 11, explaining 85% of the variability in virulence of the C. lentis population. The QTL covers a physical distance of 0.84 Mb with 98 genes, including seven candidate effector and two secondary metabolite genes.

Taken together, the study provides genetic and physical evidence for the existence of a minichromosome controlling the C. lentis virulence on lentil.

Keywords: conditionally dispensable chromosomes, disease resistance, effectors, genomics, genotyping‐by‐whole‐genome shotgun sequencing, legumes, pathogens

Introduction

Colletotrichum lentis Damm can infect various legume species, such as lentil (Lens culinaris), faba bean (Vicia faba), narrow‐leaf vetch (Vicia americana), field pea (Pisum sativum) and, under certain conditions, chickpea (Cicer arietinum) (Gossen et al., 2009). It is a very serious and damaging pathogen on cultivated lentil (Lens culinaris Medik. ssp. culinaris) in western Canada during warm and humid growing seasons, and can account for up to 70% crop loss (Morrall & Pedersen, 1991; Chongo et al., 1999), resulting in economic losses higher than those for most other pathogens of grain legumes.

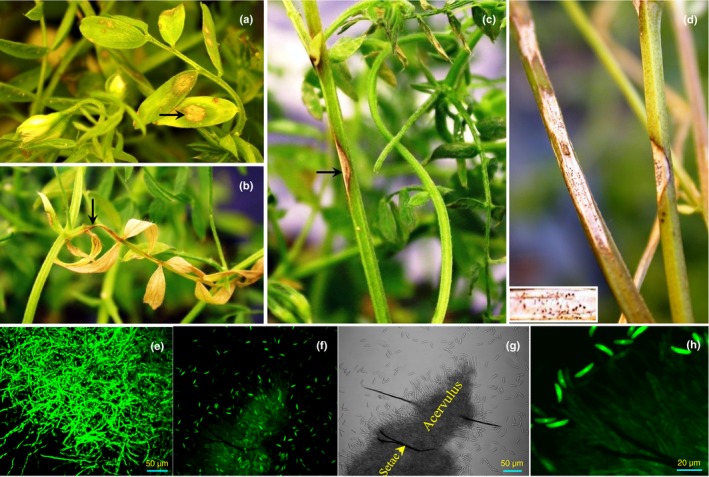

Colletotrichum lentis is a foliar pathogen and infects all aboveground parts of lentil, including leaflets, petioles and stems (Fig. 1a–c). The fungus can survive for up to 5 yr in the soil as microsclerotia (Fig. 1d,e) on lentil stubble and debris left in the field after harvest, which serve as the primary source of inoculum for subsequent lentil crops (Buchwaldt et al., 1996). The pathogen exploits a biphasic intracellular hemibiotrophic infection strategy to colonize lentil plants. The infection cycle starts when asexual spores (conidia) of the pathogen land on the host surface and germinate to form round infection structures called appressoria. A narrow penetration peg emerging from the base of the melanized appressorium ruptures the plant surface to form a spherical infection vesicle, which initiates the symptomless phase of infection, characterized by a thick biotrophic primary hypha emanating from the infection vesicle. Unlike other biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, such as Ustilago maydis, Blumeria graminis and Magnaporthe oryzae, C. lentis forms a weak plant–pathogen interphase characterized by a swift pulling away of the lentil plasma membrane from the biotrophic primary hypha during plasmolysis, indicating that the pathogen employs a unique infection strategy during the quiescent period of infection (Bhadauria et al., 2011). The length of the biotrophic phase varies and can last up to several days depending on temperature and humidity (Armstrong‐Cho et al., 2012). The biotrophic phase ceases once the pathogen deploys the effector CtNUDIX, which probably dismantles the integrity of the lentil plasma membrane (Bhadauria et al., 2013a,b). Disease symptoms appear with the onset of the necrotrophic phase, characterized by thin secondary hyphae, which kill and macerate plant tissues potentially through the massive production of ToxB and hydrolytic enzymes, as manifested by initially water‐soaked lesions that turn necrotic (Bhadauria et al., 2011, 2015). Eventually, orange‐ to salmon‐colored, single‐celled conidia ooze out of subcuticular fruiting structures (acervuli; Fig. 1f–h) in mature lesions, and are dispersed by rain splash to infect healthy neighboring plants, thus serving as a secondary source of inoculum. Under favorable conditions, the latent period of C. lentis infection is 7 d, allowing the pathogen to complete multiple cycles of infection during the cropping season (Chongo & Bernier, 2000).

Figure 1.

Symptoms of anthracnose on lentil (Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris). Anthracnose lesions (arrows) on (a) leaflet, (b) petiole and (c) stem; (d) microsclerotia (pin‐sized dark brown to black structures in lesion) of the causal pathogen Colletotrichum lentis on lentil stem; (e) crushed microsclerotium; and (f–h) conidial dispersal.

Isolates of C. lentis from lentil have been grouped into two pathogenic races, originally named Ct0 and Ct1 (Buchwaldt et al., 2004), but later renamed simply race 0 and 1 to avoid confusion with host resistance or pathogen virulence gene designation (Armstrong‐Cho et al., 2012), a renaming which has since become more logical considering the reclassification of this pathogen from C. truncatum to the new species C. lentis (Damm et al., 2014). Races of C. lentis lack the characteristic features of the classical physiological races, such as completely resistant host cultivars and clearly incompatible reactions characterized by the hypersensitive response. Although differences in responses to the races in partially resistant and fully susceptible lentil cultivars are distinct, there is a strong quantitative effect involved in the interactions (Armstrong‐Cho et al., 2012). Sources of partial resistance against the less virulent race 1 have been identified in L. culinaris and were successfully introgressed into lentil cultivars, such as L. culinaris spp. culinaris cv CDC Robin (Vandenberg et al., 2002). However, high levels of resistance to the virulent race 0 have remained elusive in the cultivated gene pool, but have been identified in the tertiary gene pool of Lens, specifically in L. ervoides (Tullu et al., 2006; Fiala et al., 2009; Bhadauria et al., 2017a).

Several draft and optical map‐based genomes of species in the genus Colletotrichum have been published in past years, addressing and comparing the molecular mechanisms governing the pathogenic life of the species (O'Connell et al., 2012; Baroncelli et al., 2014; Crouch et al., 2014; Gan et al., 2016; Zampounis et al., 2016; Buiate et al., 2017). Although an increasingly more comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of these pathogens is thus emerging, the key genes determining compatibility and virulence in the host have not been identified, with the exception of the C. lindemuthianum–Phaseolus vulgaris pathosystem, which follows a gene‐for‐gene concept as described by Flor in 1946 (Luna‐Martínez et al., 2007). With the inception of next‐generation sequencing, especially massively parallel sequencing, it has become feasible to dissect fungal genomes for loci associated with virulence, in particular when ascospore‐derived populations from crosses are available, as is the case for C. lentis.

In this study, we sequenced, assembled and annotated the genome of the virulent C. lentis isolate CT‐30 (race 0). A high‐density genetic map (14 312 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants) with 12 linkage groups (LGs) was generated through genotyping‐by‐whole‐genome shotgun sequencing of an ascospore‐derived population (n = 94) from the cross of CT‐30 (race 0) and CT‐21 (race 1). The genetic map aided in the ordering and orientation of the assembly scaffolds into pseudomolecules/chromosomes. Using SNPs and virulence data of the population on race 1‐resistant and race 0‐susceptible CDC Robin, a quantitative trait locus (QTL) controlling virulence in C. lentis was mapped onto a minichromosome. The data obtained in the study provide genetic and physical evidence of 10 core and two minichromosomes, and indicate that C. lentis regulates its virulence on lentil through a minichromosome.

Materials and Methods

Fungal isolates

The fertile isolates CT‐30 (race 0) and CT‐21 (race 1) were used as parental isolates to develop an ascospore‐derived progeny isolate population. The virulent isolate CT‐30 was used as a reference isolate to generate a de novo draft genome assembly of C. lentis. All isolates were routinely maintained on oat meal agar (OMA: 30 g blended quick oats (The Quaker Oats Company, Chicago, IL, USA), 8.8 g agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA), 1 l deionized water) plates supplemented with 0.01% chloramphenicol (AMRESCO, Solon, OH, USA).

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic DNA (gDNA) from mycelia of isolate CT‐30 was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). The CT‐30 gDNA was sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 and MiSeq sequencers (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Three paired‐end libraries with insert sizes of 250, 300 and 350 bp were constructed using the TruSeq DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc.) and sequenced to generate 2 × 100‐bp and 2 × 250‐bp reads. In addition, two mate‐pair libraries with insert sizes of 5 and 10 kb were prepared using the Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc.) and sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 platform to generate 2 × 100‐bp reads. The sequencing was performed at the Centre d'Innovation Génome Québec, Montréal, Canada. Duplicates, singletons, low‐quality reads (< Q30) and adapter sequences were removed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014). High‐quality HiSeq and MiSeq paired‐end reads were assembled into contigs using SOAPdenovo2 (Luo et al., 2012). The contigs were then anchored with a kmer of 81 using the mate‐pair reads.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession NWBT00000000. The version described in this article is version NWBT01000000.

Genome annotation

Before genome annotation, repeats from assembly scaffolds were masked using repeatmasker v.4.0.5 (Smit et al., 1996) and a fungal‐specific library of repetitive elements from RepBase (Jurka et al., 2005). The masked genome was used for ab initio gene model prediction using fgenesh (Solovyev et al., 2006) with Colletotrichum species‐specific (C. fioriniae Marcelino & Gouli ex R.G. Shivas & Y.P. Tan, C. higginsianum Sacc., C. graminicola (Ces.) G.W. Wilson, C. orbiculare Damm, P.F. Cannon & Crous and C. gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. & Sacc.) gene‐finding parameters.

Gene space coverage and genome completeness were determined using busco with a set of 1438 fungi‐specific conserved orthologous genes (Simão et al., 2015). Non‐coding RNA species, such as tRNA and rRNA, were predicted using tRNAscan‐SE (Lowe & Eddy, 1997) and rnammer (Lagesen et al., 2007), respectively. smurf (Khaldi et al., 2010) and dbCAN (Yin et al., 2012) were used to predict secondary metabolite cluster genes and carbohydrate‐active enzymes (CAZymes), respectively, in the C. lentis genome. Candidate effectors were identified following a pipeline described previously (Bhadauria et al., 2015, 2017b). signalP v.4.0 (Petersen et al., 2011) and protcomp‐AN v.10.0 (Softberry Inc., Mount Kisco, NY, USA), and tmhmm (Sonnhammer et al., 1998), were used to predict subcellular localization and transmembrane helices in the C. lentis proteome, respectively. predgpi (Pierleoni et al., 2008), netnglyc v.1.0 and netoglyc v.4.0 (Steentoft et al., 2013) were used to scan the C. lentis proteome for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor addition sites, N‐glycosylation sites and O‐glycosylation sites, respectively.

Development of a biparental C. lentis population

A biparental ascospore‐derived C. lentis population was generated in vitro by mating race 0 isolate CT‐30 with race 1 isolate CT‐21 following the procedure developed by Armstrong‐Cho & Banniza (2006). In short, stems of senescent plants of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) cultivar Eston were cut into 5‐cm pieces and autoclaved. The stems were then soaked in a 1 : 1 conidial suspension (2 × 105 conidia ml−1) of CT‐30 and CT‐21 in 20‐ml test tubes and incubated at 22°C with gentle shaking for 2 h. The stems were removed and placed in Petri dishes containing filter paper placed on top of 1.5% water agar. The plates were sealed with parafilm (Bemis Co. Inc., Neenah, WI, USA) and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 10–14 d for the induction of sexual fruiting structures (perithecia).

Mature perithecia were removed from the stems and washed individually in several droplets of sterile water to remove conidia. Each perithecium was crushed on a glass slide to release asci, which were then transferred into Petri dishes with OMA. Asci were teased gently to release and separate the ascospores before being incubated at 22°C until the ascospores had germinated. Individual germinated ascospores were transferred to new Petri dishes with OMA.

Phenotyping of the ascospore‐derived C. lentis population for virulence

Ninety‐four arbitrarily selected ascospore‐derived isolates, CT‐21 and CT‐30 were grown on OMA medium in Petri dishes for 10 d; conidia were harvested and spore suspensions were prepared with 50 000 spores ml−1.

Isolates were phenotyped in a phytotron chamber using an incomplete block design with six replications. Differential lentil cultivar CDC Robin (partially resistant to race 1 and susceptible to race 0) and susceptible cultivar Eston were grown at four plants per 10 × 10‐cm2 square pot filled with a 3 : 1 mix of Sunshine Professional Mix no. 4 (Sun Gro Horticulture, Bellevue, WA, USA) and perlite (Special Vermiculite Canada, Winnipeg, MB, Canada) for 3 wk. For inoculation, each plant was sprayed with 3 ml of conidial suspension and pots were incubated in a mist tent with 100% relative humidity for 24 h. Disease severity on leaves and stems was assessed separately at 7 d post‐inoculation (7 dpi) using the Horsfall–Barratt scale (Horsfall & Barratt, 1945). As anthracnose severity on stems provides the clearest differentiation between the races, only data from stem lesions are presented.

Disease scores were transformed into mid percentage values and averaged for each pot before analysis of variance using the mixed model procedure (proc mixed) of Sas v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Isolates and lentil cultivar were considered as fixed factors, whereas replicates and incomplete blocks were considered as random factors. The Shapiro–Wilk test implemented in proc univariate and mixtools implemented in R were used to determine the distribution of anthracnose severity on lentil stems.

Whole‐genome shotgun sequencing and variant calling

gDNA was extracted from mycelia of ascospore‐derived isolates and parental isolates CT‐30 and CT‐21 using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc.). Ninety‐six gDNA libraries were prepared using an Illumina TruSeq DNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. In short, 1 μg of high‐quality gDNA (A260/280, 1.8–2.0; A260/230, 2.0–2.4) per isolate was sheared mechanically, and the resulting fragments were end‐repaired and three prime adenylated. Paired‐end barcoded adapters were ligated to the A‐tailed DNA fragments. Libraries were multiplexed into four pools, 24 libraries per pool. Gel‐based size selection was performed at this stage, and 300‐bp DNA inserts were purified from gel bands. Library quality and size were checked on a BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) using the Agilent 1000 DNA chip (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The pooled libraries were quantified using the KAPA library quantification kit for Illumina sequencing platforms (KAPA Biosystems Inc., Woburn, MA, USA). The adapter dimer contamination‐free, 20‐pM, 24‐plex library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform to generate 2 × 100‐bp reads at the Centre d'Innovation Génome Québec, Montréal, Canada.

High‐quality paired‐end reads (Q > 30 with a sliding window of four bases) were mapped onto the C. lentis genome assembly using novalign (http://novocraft.com/). SNP variants were called from the mapped reads where parental isolates showed polymorphisms and were recorded in variant call format (vcf) using samtools mpileup (Li et al., 2009). In total, 96 vcf files were generated and merged into a population vcf before linkage mapping of SNPs. Post‐mapping quality filtering was performed as described by Bhadauria et al. (2017a).

Genetic linkage mapping, QTL detection and comparative mapping

The CT‐30 × CT‐21 genetic map was constructed by grouping high‐quality SNP markers into LGs using madmapper Python scripts (http://cgpdb.ucdavis.edu/XLinkage/MadMapper) and ordering markers within the groups using the record algorithm implemented in the Windows version of record (Van Os et al., 2005). checkmatrix Python script (Kozik & Michelmore, 2006) was used to validate the genetic map. Composite interval mapping (CIM) implemented in the Windows version of QTL cartographer v.2.5 (Wang et al., 2012) was used to map the QTL controlling the C. lentis virulence on lentil. A logarithm of the odds (LOD) score threshold of three was used to locate the QTL.

Homologous pseudomolecule sequences between C. lentis and C. higginsianum were identified using nucmer and visualized using mummerplot of mummer software (Kurtz et al., 2004).

RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐Seq) and reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR)

We used transcriptome data obtained from CT‐30‐infected tissues of lentil cultivar Eston displaying three fungal infection stages (appressoria‐assisted penetration of epidermal cells (23 h post‐inoculation (hpi)), biotrophic hyphae (55 hpi) and necrotrophic hyphae (96 hpi)) and vegetative mycelia primarily to assist in and consolidate the annotation (gene model prediction) of the C. lentis genome. We used the cultivar Eston instead of the differential CDC Robin as it is fully susceptible to both races, and hence can capture expressed gene models during various stages of the C. lentis infection process. As the experimental conditions were replicated (three biological replications), we also used the data to profile differential gene regulation.

Spray inoculation was conducted as described above in a randomized complete block design with three replications, and infected lentil tissues were harvested for the three fungal infection stages. Vegetative mycelia were collected as described by Bhadauria et al. (2017b). All tissues were flash‐frozen in liquid N2 before storing at −80°C. Frozen tissues were ground into a fine powder for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega Corp., Fitchburg, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, in‐column DNase treatment was also performed during the RNA extraction. RNA samples were quantified on a NanoDrop ND 1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and samples with an A260 : 280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 and an A260 : 230 ratio of 2.0–2.4 were further assessed for RNA integrity on a BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies) using an Agilent RNA 6000 Nano chip. Samples with an RNA Integrity Number of larger than 7 were used to generate mRNA‐Seq stranded libraries. A total of 500 ng was employed to generate RNA‐Seq libraries using the NEBNext Ultra Directional (stranded) RNA Library Prep kit for Illumina sequencing (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). Libraries were quantified using the KAPA library quantification kit for Illumina sequencing platforms (KAPA Biosystems Inc.). Nine pM of stranded mRNA library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 to generate 125‐bp paired‐end reads. In total, three lanes of the flow cell were used for sequencing.

A de novo transcriptome assembly was constructed from high‐quality paired‐end reads following a pipeline developed by Haas et al. (2013). The pipeline is based on the trinity assembler suite (Grabherr et al., 2011). The differential gene expression analysis was performed using deseq and edger R Bioconductor packages (Anders & Huber, 2010; Robinson et al., 2010). Details on RNA‐Seq data analysis can be found in Supporting Information Notes S1.

We used the differential cultivar CDC Robin to analyze the comparative expression of key genes located in the QTL controlling the C. lentis virulence on lentil. Genes were functionally annotated through blastx search of peptide sequences in the GenBank non‐redundant (nr) protein database, and by searching for homologous transcripts using the Reference RNA sequence (refseq_RNA) database to identify those with potential involvement in pathogenicity and/or virulence based on other Colletotrichum spp. The annotation ‘C. lentis‐specific’ was assigned to hits in which functional domains were unknown or unidentified. Selected genes were cross‐referenced with RNA‐Seq data and only differentially selected genes were selected. Infected leaf samples were collected at two stages, biotrophic phase and necrotrophic phase, and RNA was extracted from these samples as described above. The 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001) was used to profile the expression of the genes using C. lentis glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and 60S as reference genes and vegetative hyphae as a calibrator.

Results and Discussion

High‐quality C. lentis genome assembly

Sequencing of the fertile C. lentis isolate CT‐30 (race 0) on Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms yielded a genome assembly of 56.10 Mb with a 1481‐fold coverage (Tables 1, S1). A total of 2980 contigs was assembled from 100‐ and 250‐bp paired‐end reads originating from short paired‐end libraries (250, 300 and 350 bp). Anchoring of contigs using 100‐bp paired‐end reads from long mate‐pair libraries (5 and 10 kb) resulted in 50 scaffolds with an N 50 length of 4.89 Mb, which is higher than that of almost all other sequenced Colletotrichum species, such as an N 50 scaffold length of 579.19 kb for C. graminicola (57.44 Mb, 653 scaffolds), 428.89 kb for C. orbiculare (88.3 Mb, 525 scaffolds), 112.81 kb for C. gloeosporioides (55.6 Mb, 1241 scaffolds), 137.25 kb for C. fioriniae (49.01 Mb, 1108 scaffolds) and 292 kb for C. incanum (53.25 Mb, 1036 scaffolds) (O'Connell et al., 2012; Gan et al., 2013, 2016; Baroncelli et al., 2014). The first genome assembly of C. higginsianum (53.35 Mb, 367 scaffolds) also had a lower N 50 length of 265.5 kb (O'Connell et al., 2012), but, in a recently reported improved version of the C. higginsianum genome assembly with 25 scaffolds, the N 50 scaffold length was increased to 5.20 Mb (Zampounis et al., 2016). Furthermore, using PacBio and optical mapping, the authors sequenced 11 of the 12 chromosomes from telomere to telomere. Eighteen scaffolds of C. lentis contain at least one telomere, as evident by the presence of tandem repeats (TTAGGG)n or (CCCTAA)n. Among these, three (scaffold10, scaffold14 and scaffold16) have both telomeres and hence are full chromosomes. Scaffold14 is a 1.52‐Mb minichromosome.

Table 1.

The Colletotrichum lentis genome assembly features

| Genome features | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Assembly size | 56.10 Mb |

| Contigs | 2980 |

| Contig N/L50 | 248/51.16 kb |

| Scaffolds | 50 |

| Scaffold N/L50 | 5/4.89 Mb |

| Gap | 1.70% |

| Protein coding gene models | 11 436 |

| GC content | 48.62% |

| tRNA | 329 |

| rRNA | 54 |

| Repeat elements | 4.56% |

| Gene model coveragea | 99.58% |

Complete/partial gene models as evaluated by BUSCO (Simão et al., 2015).

Nearly 90% (51.0 Mb) of the C. lentis genome assembly was contained in 15 scaffolds of varying lengths ranging from 1.46 to 6.69 Mb, suggesting that the C. lentis genome assembly is a high‐quality reference assembly and close to the pseudomolecule level. The genome size of C. lentis (56.10 Mb) is similar to that of other Colletotrichum species, except for C. orbiculare whose genome is expanded to 88.3 Mb. A total of 1432 (98.58%) of 1438 benchmarking universal single‐copy fungal orthologous genes (Simão et al., 2015) were mapped onto the genome, providing further evidence for a near‐complete genome assembly. Repetitive DNA represents 4.56% of the genome assembly, which is greater than that reported in C. higginsianum (1.2%) and C. gloeosporioides (0.75%), but less than that in C. graminicola (12.2%) and C. orbiculare (8.3%). The C. lentis genome has a GC content of 48.62%, which is comparable with that of other Colletotrichum species.

Genome annotation reveals reduction in gene models involved in pathogenesis

A total of 11 436 protein‐coding gene models was predicted in the genome of C. lentis (Tables 1, S2), lower than that reported for other sequenced Colletotrichum species, such as C. graminicola (12 006), C. orbiculare (13 479), C. fioriniae (13 759), C. higginsianum (14 651) and C. gloeosporioides (15 469). The number of gene models in C. lentis is comparable with that of C. incanum, whose genome contains 11 852 gene models (Gan et al., 2016).

Similarly, with 237 effectors (Table S3), the effectorome of C. lentis is reduced relative to that of other Colletotrichum species, such as C. orbiculare (700) and C. gloeosporioides (755) (Gan et al., 2016). Twenty‐three of them are unique to C. lentis, whereas the remaining have homologs within the genus Colletotrichum. Of the 237 candidate effectors, 143 were differentially expressed (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) in the host lentil cv Eston (susceptible to both races) during infection when compared with vegetative mycelia. Nearly 57% of the candidate effectors (135) have known homologs, suggesting a conserved infection strategy across species belonging to the genus Colletotrichum. These include various classes of extracellular (EC) proteins known to sequester fungal chitin to evade detection by the host, host‐range‐determining pea pathogenicity protein 1 (Pep1), biotrophy–necrotrophy switch regulator NUDIX, biotrophy‐associated secreted protein 2, cholera enterotoxin subunit A2, cell death‐inducing necrosis and ethylene‐inducing protein 1‐like protein 4, chitin‐binding proteins and CFEM (Common in Fungal Extracellular Membrane proteins) domain‐containing protein.

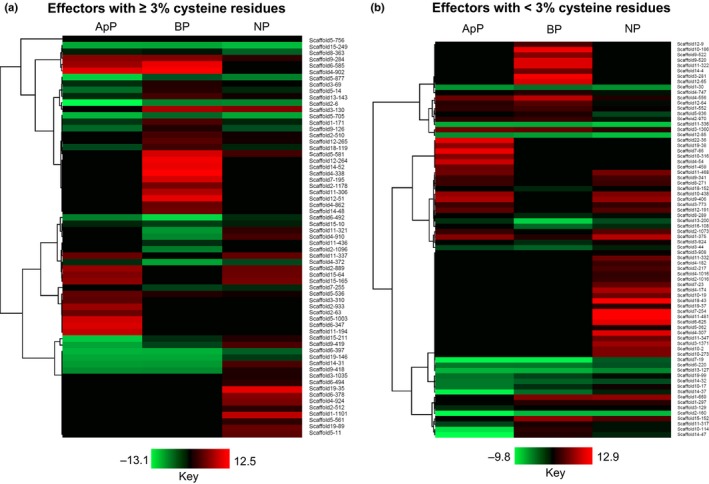

The number of cysteine‐rich effectors (3.0% or more cysteine residues) was also considerably lower in C. lentis (104) compared with C. orbiculare (372) and C. gloeosporioides (355) (Table S3). Of these, 14 were highly induced during the penetration of lentil cells via appressoria. These include EC7 (scaffold6‐347, 9.6‐fold), EC2 (scaffold5‐1003, 9.2‐fold), EC14 (scaffold11‐194, 8.6‐fold), EC20 (scaffold2‐63, 4.8‐fold), a chitin‐binding protein (scaffold2‐933, 6.8‐fold) and a CFEM domain‐containing protein (scaffold5‐536, 4.3‐fold) (Fig. 2a; Table S4). Nineteen were upregulated during the biotrophic phase wherein lentil epidermal cells were colonized by thick primary hyphae. Among them were EC34 (scaffold4‐338, 11.5‐fold), an alcohol dehydrogenase (scaffold12‐265, 3.9‐fold) and four C. lentis‐specific candidate effectors (scaffold14‐52 (10.4‐fold), scaffold14‐48 (5.0‐fold), scaffold13‐143 (3.0‐fold) and scaffold2‐510 (3.0‐fold)). Seventeen candidate effectors were induced during the necrotrophic phase wherein lentil cells were macerated by the secondary hyphae, including two cell wall‐degrading pectate lyases (scaffold19‐35 (10.2‐fold) and scaffold1‐1101 (8.3‐fold)) and a glycoside hydrolase (scaffold6‐378, 5.9‐fold).

Figure 2.

Heatmap representing the expression of candidate effectors (log2 fold change (log2 FC) ≥ 2, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) of Colletotrichum lentis in planta (lentil cultivar Eston) compared with in vitro‐grown mycelia. (a) Cysteine‐rich (≥ 3% cysteine residues) candidate effectors; (b) candidate effectors containing < 3% cysteine residues. Hierarchical clustering was performed to cluster gene expression using the one minus Pearson correlation. ApP, appressorium‐assisted penetration (23 h post‐inoculation (hpi)); BP, biotrophic phase (55 hpi); NP, necrotrophic phase (96 hpi).

Of the 237 candidate effectors, 133 contained 0–2.9% cysteine residues (Table S3). Of these, 19 were induced during the penetration phase via appressoria, including appressorium‐specific protein Cas1 (scaffold7‐86, 11.0‐fold), a cell wall protein (scaffold4‐54, 9.1‐fold), polysaccharide deacetylase (scaffold1‐459, 4.9‐fold), SCP‐like EC protein (scaffold12‐191, 4.3‐fold) and pathogenesis‐associated protein Cap20 (scaffold3‐773, 2.7‐fold) (Fig. 2b; Table S5). Fifteen candidate effectors were upregulated during the biotrophic phase, including three paralogs of the NUDIX effector (scaffold12‐65 (9.7‐fold), scaffold12‐9 (3.4‐fold) and scaffold1‐552 (2.8‐fold)) and EC32 (scaffold11‐322, 10.0‐fold). Thirty candidate effectors were induced during the biotrophic phase, and the majority were involved in plant cell tissue maceration, such as endoglucanase II (scaffold7‐254 (12.9‐fold), scaffold18‐43 (11.8‐fold), scaffold4‐174 (7.9‐fold), scaffold10‐438 (5.7‐fold) and scaffold2‐1016 (2.5‐fold)), endo‐1,4‐β‐xylanase (scaffold6‐625, 10.5‐fold), pectinesterase (scaffold4‐307, 10.2‐fold) and amidohydrolase (scaffold4‐307, 7.2‐fold).

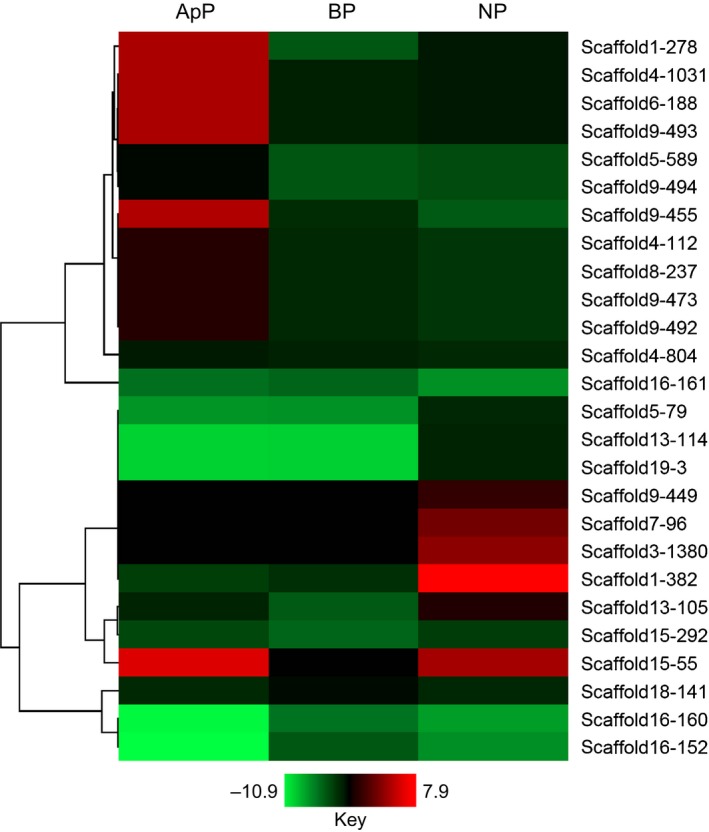

The C. lentis genome contains 43 secondary metabolite backbone‐forming proteins, which is lower than the numbers identified in the genomes of C. higginsianum (84), C. graminicola (53), C. orbiculare (54) and C. gloeosporioides (76) (Fig. S1). Six were induced during the penetration phase via appressoria, comprising five polyketide synthases (PKSs; scaffold15‐55 (6.1‐fold), scaffold4‐1031 (4.8‐fold), scaffold6‐188 (4.8‐fold), scaffold9‐493 (4.8‐fold) and scaffold1‐278 (4.8‐fold)) and one dimethylallyl tryptophan synthase (scaffold9‐455, 4.9‐fold) (Fig. 3; Tables S6, S7). The induction of PKS genes during this phase is consistent with their involvement in appressorium‐dependent penetration as they encode enzymes implicated in melanin biosynthesis. Lack of induction in the expression of backbone genes was evident during the biotrophic phase, whereas four were upregulated during the necrotrophic phase, for example, one non‐ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS; scaffold1‐382, 7.9‐fold), two NRPS‐like (male sterility proteins; scaffold3‐1380 (4.0‐fold) and scaffold7‐96 (3.3‐fold)) and one PKS (scaffold15‐55, 4.6‐fold).

Figure 3.

Heatmap representing the expression of secondary metabolite backbone genes (log2 fold change (log2 FC) ≥ 2, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) of Colletotrichum lentis in planta (lentil cultivar Eston) compared with in vitro‐grown mycelia. Hierarchical clustering was performed to cluster gene expression using the one minus Pearson correlation. ApP, appressorium‐assisted penetration (23 h post‐inoculation (hpi)); BP, biotrophic phase (55 hpi); NP, necrotrophic phase (96 hpi).

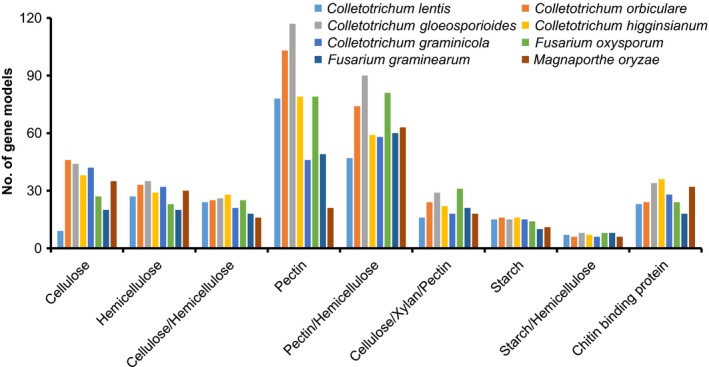

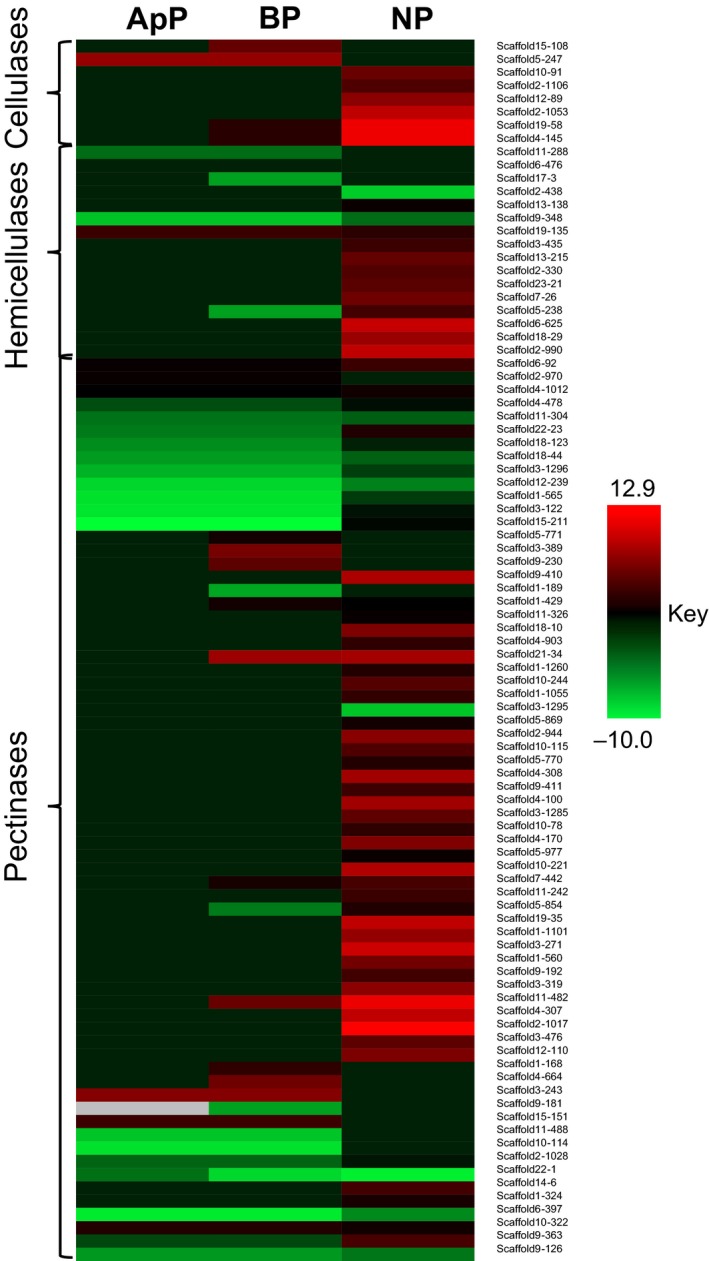

Fungal pathogens deploy CAZymes to gain access to plant tissues by breaking down plant cell wall components, such as cellulose, hemicellulose and pectins. Similar to effectors and secondary metabolites, genome analysis revealed that C. lentis encoded fewer CAZymes (229) than any other sequenced genome in the genus, including C. orbiculare (327), C. gloeosporioides (364), C. higginsianum (278) and C. graminicola (288) (Fig. 4; Table S8). The contraction of the CAZyme arsenal is attributed to a reduction in cellulose‐degrading enzymes (7), which is four‐ to five‐fold lower than in any other Colletotrichum species. Of these 229 CAZymes, 155 were differentially expressed in planta when compared with vegetative mycelia (Table S9). Six of the eight cellulases were highly induced during the necrotrophic phase (scaffold2‐1106 (glucanase, 5.1‐fold), scaffold19‐58 (glycosyl hydrolase, 12.3‐fold), scaffold4‐145 (glucanase, 12.3‐fold), scaffold2‐1053 (exoglucanase, 10.2‐fold), scaffold12‐89 (glucanase, 7.8‐fold) and scaffold10‐91 (β‐glucosidase, 6.3‐fold)) (Table S9). Similarly, hemicelluloses (48%) and pectinases (47%) were activated during this phase, including xylanase (scaffold6‐625 (10.5‐fold) and scaffold2‐990 (10.2‐fold)), polysaccharide lyase (12.9‐fold), α‐l‐rhamnosidase (12.2‐fold), cell wall glycosyl hydrolase (10.7‐fold), pectinesterase (10.2‐fold) and pectate lyase (10.2‐fold) (Fig. 5). Some of the CAZymes are also involved in fungal cell wall remodeling or modification to adapt to the in planta infection life style. These include those binding fungal chitin to evade recognition by the host defense system, such as intracellular hyphae protein 1 (scaffold3‐243, 7.6‐fold), chitin recognition proteins (scaffold15‐151 (4.3‐fold) and scaffold10‐322 (3.1‐fold)) and chitin deacetylase (scaffold4‐664, 6.6‐fold).

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of carbohydrate‐active enzymes (CAZymes) of Colletotrichum lentis. The y‐axis indicates the number of gene models encoding CAZymes associated with the degradation of plant cell wall components (x‐axis).

Figure 5.

Heatmap representing the expression of Colletotrichum lentis genes encoding enzymes required for the degradation of plant cell wall components, such as cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin (log2 fold change (log2 FC) ≥ 2, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) in planta (lentil cultivar Eston) compared with in vitro‐grown mycelia. Hierarchical clustering was performed to cluster gene expression using the one minus Pearson correlation. ApP, appressorium‐assisted penetration (23 h post‐inoculation (hpi)); BP, biotrophic phase (55 hpi); NP, necrotrophic phase (96 hpi).

The expansion and contraction of gene families encoding potential virulence factors are known to be associated with the host range of Colletotrichum species, but it is not known whether expanded or contracted gene families are the ancestral state. In the C. acutatum species complex, lineage‐specific losses of CAZymes and effectors could be associated with a narrower host range, whereas an expansion of these gene families was found in lineages with a broader host range (Baroncelli et al., 2016). Similarly, the contraction in gene families encoding candidate effectors, CAZymes and enzymes implicated in secondary metabolism in C. lentis is likely associated with a narrow host range restricted to a few species in the Fabeae.

Genotyping by re‐sequencing reveals 10 core and two minichromosomes

High‐density genetic linkage maps are an ideal tool to understand the structural features of a genome, such as the number of rearrangements within, and general organization of, chromosomes, and can be used to assemble supercontigs or scaffolds into pseudomolecules/chromosomes by ordering and orienting them with the help of anchoring genetic markers. However, for fungal species, this requires a laborious process of developing mapping populations originating from biparental crosses.

Unlike other fungal species, fungi in the genus Colletotrichum predominantly reproduce asexually, and sexual reproduction is rare in the field (O'Connell et al., 2012). The reference isolate CT‐30 (race 0) used in the study is cross‐fertile with isolate CT‐21 (race 1) in the laboratory on sterile lentil stems (Armstrong‐Cho & Banniza, 2006). We generated ascospore‐derived progeny isolates from an in vitro‐induced cross between these two isolates. Ninety‐four of these, together with the parental isolates, were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, which yielded 598 130 601 paired‐end 100‐bp shotgun sequencing reads. The reads were aligned against the C. lentis genome assembly, which resulted in 535 158 586 uniquely mapped reads (89.47%) and 62 972 015 multimapped and unmapped reads (10.53%). The uniquely mapped reads give a 19.08‐fold genomic coverage of isolates with an average of 5574 569 reads per isolate (Table S10). A total of 73 817 polymorphisms between the parental isolates CT‐30 and CT‐21 were called from the uniquely mapped reads using Bowtie2/SAMtools mpileup. Of these, 15 796 were insertion and deletion (INDEL) polymorphisms and 58 021 were SNPs. SNPs are the most frequent genetic variations and provide unique positional information across the population at single base resolution, and therefore were selected for linkage mapping.

Only 14 132 (24%) SNPs remained after a stringent post‐mapping quality filtering based on an allele coverage of five‐fold or more, < 25% missing allele calls per locus and per isolate (SNP calls missing in 26 isolates or fewer) and 0.33 minor allele frequency. The SNPs were assembled into 931 unique haplotypes consisting of 530 genetic bins within which markers showed no evidence of recombination, and 401 singletons (Table 2). The χ 2 test revealed that 6.12% (57 SNP markers) of the mapped SNP loci deviated significantly (P < 0.05) from the expected 1 : 1 ratio of parental allele contribution considering the haploid genome of C. lentis (Table S11).

Table 2.

Summary of the Colletotrichum lentis genetic linkage map

| Linkage groups | Genetic bins | Markers in genetic bins | Singleton markers | Unique haplotypes | Genetic distance (cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52 | 895 | 49 | 101 | 194.36 |

| 2 | 73 | 1672 | 37 | 110 | 181.65 |

| 3 | 67 | 2046 | 50 | 117 | 180.17 |

| 4 | 51 | 3739 | 40 | 91 | 179.79 |

| 5 | 47 | 901 | 37 | 84 | 178.90 |

| 6 | 44 | 969 | 36 | 80 | 149.68 |

| 7 | 59 | 776 | 42 | 101 | 149.28 |

| 8 | 50 | 927 | 33 | 83 | 132.53 |

| 9 | 45 | 561 | 41 | 86 | 129.81 |

| 10 | 34 | 510 | 32 | 66 | 122.78 |

| 11 | 5 | 943 | 4 | 9 | 19.83 |

| 12 | 3 | 193 | 0 | 3 | 7.06 |

| Total | 530 | 14 132 | 401 | 931 | 1625.84 |

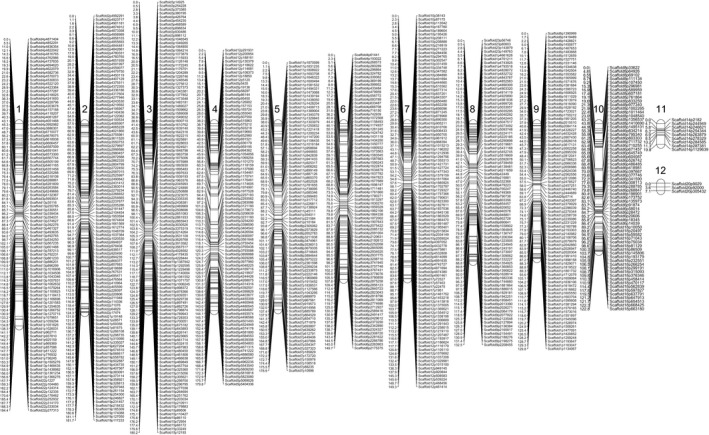

The high‐quality SNPs were used to construct a linkage map. The SNP markers were mapped into 12 LGs, which is equivalent to the chromosome number of the closely related species C. higginsianum (O'Connell et al., 2012; Zampounis et al., 2016) (Fig. 6). Results of 2D‐checkmatrix (Kozik & Michelmore, 2006) and R/qtl (Broman et al., 2003) confirmed the high quality of the genetic linkage map (Fig. S2), which covered a cumulative distance of 1625.8 cM (1 cM = 34 505 bp) with an average intermarker distance of 1.44 cM (49 690 bp). The map covers a similar distance to the amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)‐based map constructed for C. lindemuthianum (1897 cM), but is much denser than the average intermarker distance of 11.49 cM for that species (Luna‐Martínez et al., 2007). The number of SNP markers varied from three in LG12 to 117 in LG3, and the genetic distance from 7.06 cM (296 404 bp) in LG12 to 194.36 cM (3 785 929 bp) in LG1 (Table 2). The LGs were numbered from LG1 to LG12 by decreasing genetic distance (Fig. 6). LG1 to LG10 spans a higher physical distance (3.70 Mb or more) than the remaining two LGs LG11 (1.13 Mb) and LG12 (0.30 Mb) (Table 3), suggesting that the C. lentis genome is organized into 10 core and two minichromosomes. Scaffold14 contains both telomeric ends (CCCTAA)n at the 5′‐end and (TTAGGG)n at the 3′‐end, and harbors LG11 (1.13 Mb). As a result of low recombination at telomeres, LG11 lacks the ends (telomeres) of scaffold14. Therefore, we conclude that scaffold14 and LG11 both represent the same minichromosome 11 (1.52 Mb). Accumulating evidence suggests that the genomes in the genus Colletotrichum are organized into 10 core chromosomes and a variable number of minichromosomes, such as two in C. higginsianum (0.65 and 0.61 Mb) and three in C. graminicola (ranging from 0.51 to 0.71 Mb) (O'Connell et al., 2012).

Figure 6.

High‐density genetic linkage map of the Colletotrichum lentis biparental population (n = 94 ascospore‐derived isolates) originating from a cross between isolates CT‐30 (race 0) and CT‐21 (race 1). To the right of the linkage groups (1–12) are single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers whose genetic positions in centimorgans are shown to the left of the linkage groups.

Table 3.

Genetic map‐guided Colletotrichum lentis genome assembly at the pseudomolecule level

| Chromosomes | Size (Mb) | GC (%) | Repeat element kb (%) | Retroelements | DNA transposons | Small RNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | 3.785929 | 51.87 | 129.09 (3.41%) | 34 | 1 | 0 |

| Chr2 | 6.04485 | 52.10 | 182.09 (3.01%) | 46 | 13 | 0 |

| Chr3 | 5.611468 | 51.19 | 215.13 (3.83%) | 88 | 17 | 1 |

| Chr4 | 5.770251 | 49.38 | 231.47 (4.01%) | 95 | 22 | 0 |

| Chr5 | 6.258091 | 49.88 | 191.86 (3.07%) | 64 | 11 | 0 |

| Chr6 | 4.623406 | 49.55 | 194.63 (4.21%) | 104 | 21 | 0 |

| Chr7 | 4.675034 | 50.11 | 190.46 (4.07%) | 73 | 6 | 1 |

| Chr8 | 4.085457 | 50.82 | 180.75 (4.42%) | 92 | 14 | 1 |

| Chr9 | 4.219243 | 50.94 | 136.95 (3.25%) | 26 | 5 | 0 |

| Chr10 | 3.697061 | 50.97 | 143.32 (3.88%) | 35 | 11 | 2 |

| Chr11 | 1.128011 | 38.60 | 96.78 (8.58%) | 102 | 31 | 0 |

| Chr12 | 0.296404 | 38.60 | 23.16 (7.81%) | 18 | 15 | 0 |

| Unassembled | 5.904878 | 47.99 | 342.54 (5.80%) | 239 | 112 | 2 |

| Total | 56.100083 | 48.62 | 2258.23 (4.57%) | 1016 | 279 | 7 |

Genome assembly at the chromosome level and comparative mapping

Twenty‐two scaffolds of the C. lentis genome assembly ranging from 0.16 to 6.69 Mb were ordered and oriented into 12 chromosomes using the unique coordinates of the 931 SNP markers distributed on the CT‐30 × CT‐21 linkage map (Table S12). The chromosomes contain 46.83 Mb of the 56.10‐Mb genome assembly. Furthermore, we took advantage of genetic bins to further extend the chromosome lengths as SNP markers within the genetic bins share the same genetic distance (identical haplotypes) whilst differing in physical distance. This resulted in the assignment of an additional 3.38 Mb to chromosomes, increasing the size of sequences assembled into chromosomes to 50.21 Mb (89.51% of the genome), leaving 11.49% (5.90 Mb) of the genome unassembled (Table 3).

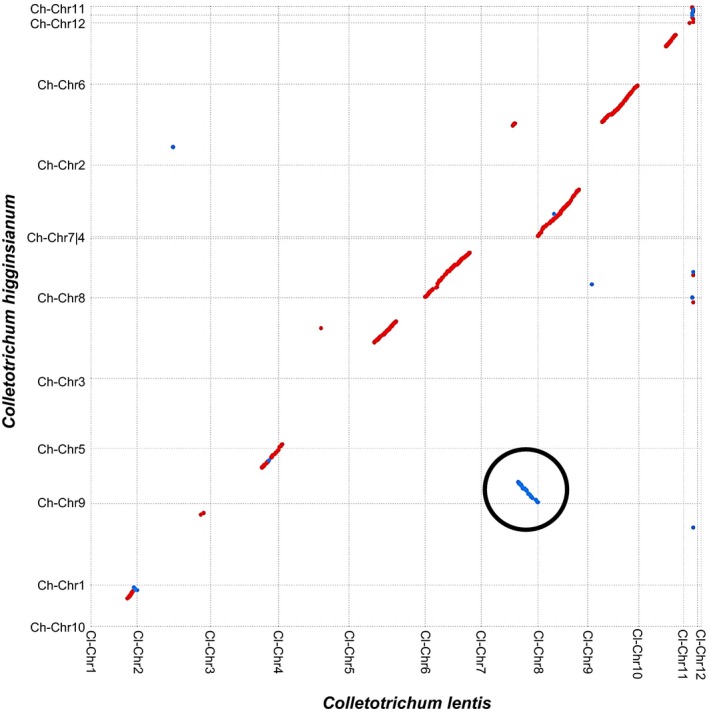

Comparative analysis reveals a truncated collinearity along the pseudomolecules of C. lentis and C. higginsianum. A high level of collinearity was identified between C. lentis (Cl)‐Chromosome (Chr) 6 and C. higginsianum (Ch)‐Chr8, and between Cl‐Chr8 and Ch‐Chr4 (Fig. 7). A reciprocal translocation was observed in C. lentis between chromosomes 3 and 7 (Fig. 7). The minichromosome Cl‐Chr11 is syntenic to Ch‐Chr11 and Ch‐Chr12, suggesting that both C. higginisianum minichromosomes may be two segments (0.65 and 0.61 Mb) of a larger minichromosome (1.26 Mb) that is almost similar in size to Cl‐Chr11. Both C. lentis minichromosomes Cl‐Chr11 and Cl‐Chr12 contain 38.60% GC content, which is significantly lower than that of the core genome (50.68% for Chr1 to Chr10). At the same time, both minichromosomes are enriched with repetitive DNA (averaging 8.2%) compared with the core genome (3.72%) (Table 3). These minichromosomes are gene sparse as the gene density (Chr11, 132 genes; Chr12, 31 genes; 111 genes/Mb on average) is just over one‐half of that of the core genome (204 genes/Mb on average). We also checked the SNP, presence/absence and INDEL variants located on minichromsomes in the C. lentis biparental population, confirming that all 94 progeny isolates maintained both minichromosomes, suggesting that C. lentis does not lose minichromosomes after meiosis (Tables S13–S16).

Figure 7.

Dot plot representing the correspondence between Colletotrichum higginsianum chromosomes (Ch‐Chr1 to Ch‐Chr12, x‐axis) and C. lentis chromosomes (Cl‐Chr1 to Cl‐Chr12, y‐axis). Translocation is circled in black. Red dots (lines) represent sequences aligning in the same direction, whereas blue dots (lines) show sequences aligning in the opposite direction.

QTL mapping reveals a minichromosome governing the C. lentis virulence on lentil

To determine the genetic control of virulence in C. lentis, the genotyped ascospore‐derived isolates (n = 94) were phenotyped for virulence, measured as anthracnose severity on the differential L. culinaris spp. culinaris cv CDC Robin in the glasshouse.

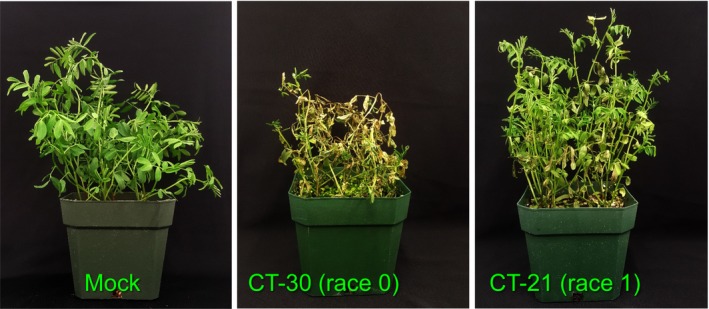

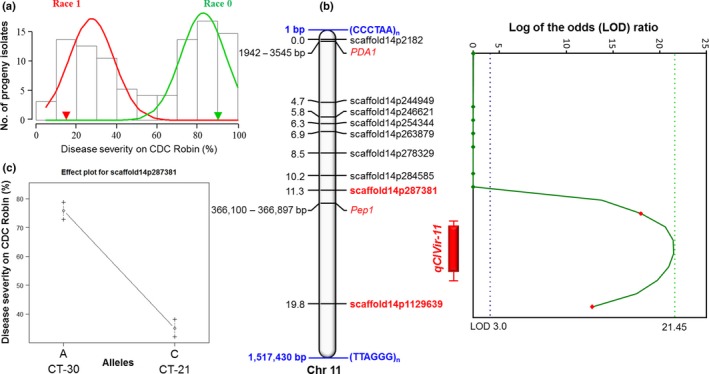

The disease severity caused by isolates ranged from 9 to 100%. The race 1 isolate CT‐21 caused 16% disease severity on CDC Robin (partially resistant to this race), whereas CT‐30, the race 0 isolate, caused 91% disease severity on CDC Robin, which is susceptible to this race (Fig. 8). Analysis of variance revealed significant effects of isolates on anthracnose severity on CDC Robin (F = 14.64, P < 0.001). The frequency distribution of isolates for anthracnose severity on CDC Robin with partial resistance to race 1 revealed a bimodal distribution, indicating that the virulence of C. lentis on lentil may be controlled by a single major effect QTL (Fig. 9a).

Figure 8.

Disease reactions of Colletotrichum lentis isolates on the differential Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris cultivar CDC Robin at 7 d post‐inoculation.

Figure 9.

Phenotyping of ascospore‐derived isolates and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping. (a) Frequency distribution of anthracnose severity on the differential Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris cultivar CDC Robin. (b) QTL qClVIR11 controlling virulence of Colletotrichum lentis on lentil is shown as a red solid bar with 1 – LOD confidence intervals. Vertical lines with caps on the bars represent 2 – LOD likelihood intervals. The chart next to the QTL displays the logarithm of the odds (LOD) ratio along minichromosome 11. The chromosome contains telomeric tandem repeats (CCCTAA)n at the 5′‐end and (TTAGGG)n at the 3′‐end. Blue and green dotted lines represent the LOD score threshold set for QTL detection and the observed LOD score, respectively. (c) Effect plot for the SNP marker scaffold14p287381 linked to the QTL qClVIR11.

Composite interval mapping was performed using 931 SNPs and least‐square means of anthracnose severity, resulting in a single QTL qClVIR11 (LOD = 21.45, P < 0.05) mapped onto the gene‐sparse minichromosome 11 (Figs 9b, S3b, S4). The detection of a single QTL is consistent with the bimodal distribution of anthracnose severity caused by ascospore‐derived isolates on the differential cultivar CDC Robin. The QTL explains 85.23% of the variation in anthracnose severity among isolates, confirming that qClVIR‐11 is a major effect QTL. The additive genetic effect of the nearest locus, scaffold14p28738, linked to qClVIR11 was +26.49 (allele A), and therefore, as expected, isolate CT‐30 contributed the virulence allele to the population (Fig. 9c). The QTL flanked by two markers (scaffold14p287381 and scaffold14p1129639) covers a genetic distance of 8.5 cM and a physical distance of 0.84 Mb.

The QTL contains 98 genes, including seven candidate effector and two secondary metabolite genes (Table S17). Two (PDA1 and Pep1) of six pea pathogenicity (Pep) cluster gene orthologs were identified on the 1.52‐Mb minichromosome 11. In Fusarium solani f. sp. pisi, the Pep cluster genes are localized in a 1.6‐Mb conditionally dispensable minichromosome, which is essential for its virulence on pea (Fusarium root rot). Four of the Pep genes (PDA1, Pep1, Pep2 and Pep5) are known to contribute to virulence. In F. oxysporum f. sp. pisi, PDA1 is always found with Pep1 on a minichromosome, and both are located in close proximity to each other (Temporini & VanEtten, 2004). For the F. solani species complex, it has been speculated that these minichromosomes are acquired by individual isolates through horizontal gene transfer based on the discontinuous phylogenetic distribution of PDA and Pep genes, and that they enable these isolates to colonize additional ecological niches, such as new host species (reviewed in Coleman, 2016). Similar to F. oxysporum f. sp. pisi, PDA1 and Pep1 are 0.36 Mb apart in C. lentis (Fig. 9b). Pisatin demethylase encoded by PDA1 detoxifies the phytoalexin pisatin produced as a defense response by pea (Coleman et al., 2011). PDA1 is located outside of QTL qClVIR‐11, whereas Pep1 is inside the QTL region. The presence of PDA1 and Pep1 suggests that minichromosome 11 may be a conditionally dispensable chromosome. It appears that Pep1 is unlikely to be associated with the difference in virulence between CT‐30 and CT‐21 isolates as the expression of the gene is biologically insignificant (CT‐30/CT‐21 at the biotrophic phase, 5.83 ± 0.41/6.59 ± 0.19 (log2 fold ± SEM, P > 0.01); Table S17). Recently, Plaumann et al. (2018) have identified two T‐DNA insertion C. higginsianum mutants, vir‐49 and vir‐51, defective in the passage from biotrophy to necrotrophy. Both mutants show attenuated virulence on the host Arabidopsis thaliana and lack chromosome 11. Similar to our finding in C. lentis, the authors concluded that chromosome 11 is a conditionally dispensable minichromosome controlling C. higginsianum virulence on A. thaliana.

Concluding remarks

Several genomes in the genus Colletotrichum have been sequenced, but only two have been assembled to the chromosome level guided through optical maps (O'Connell et al., 2012). Here, we present a population sequencing (POPSEQ)‐based genome assembly of C. lentis and provide genetic and physical evidence for the presence of 10 core and two minichromsomes. One of the minichromosomes regulates the C. lentis virulence on lentil. To our knowledge, this is the first genetic map‐based genome assembly reported for any fungal plant pathogen.

Author contributions

S.B. is grant holder. S.B., V.B. and C.P. designed the research and V.B. was the leading researcher. V.B., R.M. and A.C‐S., under the supervision of S.B., performed the experiments and analyzed the data, except for the expression profiling of 22 genes, which was conducted by L.L. and J.H. The research was conducted at the Crop Development Centre/Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. Genome annotation, masking of repetitive sequences, CAZyme and secondary metabolite identification, prediction of telomeric regions in the scaffolds, and comparative genome mapping and visualization were performed by V.B. at the Swift Current Research and Development Center, Agriculture and Agri‐Food Canada, Swift Current, Saskatchewan, Canada. V.B. drafted the manuscript at the Swift Current Research and Development Center, Agriculture and Agri‐Food Canada, Swift Current, Saskatchewan, Canada with contributions from S.B., who also edited the manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed by all co‐authors.

Supporting information

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Fig. S1 Comparative analysis of secondary metabolite backbone genes in Colletotrichum species.

Fig. S2 Validation of the genetic linkage map of ascospore‐derived isolates originating from a cross between Colletotrichum lentis isolates CT‐30 and CT‐21.

Fig. S3 Genetic and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping.

Fig. S4 Colletotrichum lentis minichromosome 11.

Table S1 Libraries, sequencing platforms and sequence reads used to generate the Colletotrichum lentis genome assembly

Table S2 General feature format (gff) of Colletotrichum lentis protein‐coding gene models

Table S3 List and functional annotation of candidate effectors predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome

Table S4 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed cysteine‐rich candidate effectors of Colletotrichum lentis isolate CT‐30 in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S5 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed candidate effectors of Colletotrichum lentis containing < 3% cysteine residues in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S6 List and functional annotation of the secondary metabolite backbone genes predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome

Table S7 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed secondary metabolites of Colletotrichum lentis backbone genes in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S8 List and functional annotation of the carbohydrate‐active enzymes predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome and associated with the degradation of cell wall components and chitin binding

Table S9 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed genes of Colletotrichum lentis encoding carbohydrate‐active enzymes in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S10 Whole‐genome shotgun sequencing of Colletotrichum lentis population

Table S11 Segregation distortion of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers

Table S12 Colletotrichum lentis pseudomolecules/chromosomes

Table S13 qClVir11 haplotype: the qClVir11 region flanked by scaffold14p287381 and scaffold14p1129639 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers contains 1363 SNPs

Table S14 Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants with allele coverage ≥ 5 on minichromosome 12 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S15 Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants with allele coverage > 2 on minichromosome 12 of the progeny isolate GT‐2 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S16 Insertion/deletion (INDEL), presence/absence and polymorphism length on minichromosome 11 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S17 List and functional annotation of candidate genes underlying the quantitative trait locus (QTL) qClVIR11 controlling the Colletotrichum lentis virulence on lentil, and expression data of CT‐21 and CT‐30 during the biotrophic and necrotrophic phases

Notes S1 RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐Seq) data analysis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery and NSERC‐CRD grants, and funding from the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers and the Western Grains Research Foundation, Canada awarded to S.B. Technical support for this study was provided by S. Boechler, C. Knihniski, D. Congly, D. Klassen, C. Armstrong‐Cho and A. Hendriks. The authors would like to thank Dr Sean Walkowiak (Crop Development Centre/Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan) for generating a summary table of sequence reads used in the assembly of the C. lentis genome.

Contributor Information

Vijai Bhadauria, Email: vijai.bhadauria@canada.ca.

Sabine Banniza, Email: sabine.banniza@usask.ca.

References

- Anders S, Huber W. 2010. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 11: R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong‐Cho CL, Banniza S. 2006. Glomerella truncata sp. nov., the teleomorph of Colletotrichum truncatum . Mycological Research 110: 951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong‐Cho C, Wang J, Wei Y, Banniza S. 2012. The infection process of two pathogenic races of Colletotrichum truncatum on lentil. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 34: 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baroncelli R, Amby DB, Zapparata A, Sarrocco S, Vannacci G, Le Floch G, Harrison RJ, Holub E, Sukno SA, Sreenivasaprasad S et al 2016. Gene family expansions and contractions are associated with host range in plant pathogens of the genus Colletotrichum . BMC Genomics 17: 555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroncelli R, Sreenivasaprasad S, Sukno SA, Thon MR, Holu E. 2014. Draft genome sequence of Colletotrichum acutatum sensu lato (Colletotrichum fioriniae). Genome Announcement 2: e00112–e00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, Banniza S, Vandenberg A, Selvaraj G, Wei Y. 2011. EST mining identifies proteins putatively secreted by the anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum truncatum . BMC Genomics 12: 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, Banniza S, Vandenberg A, Selvaraj G, Wei Y. 2013a. Overexpression of a novel biotrophy‐specific Colletotrichum truncatum effector, CtNUDIX, in hemibiotrophic fungal phytopathogens causes incompatibility with their host plants. Eukaryotic Cell 12: 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, Bett KE, Zhou T, Vandenberg A, Wei Y, Banniza S. 2013b. Identification of Lens culinaris defense genes responsive to the anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum truncatum . BMC Genetics 14: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, MacLachlan R, Pozniak C, Banniza S. 2015. Candidate effectors contribute to race differentiation and virulence of the lentil anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum lentis . BMC Genomics 16: 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, Ramsay L, Vandenberg A, Bett KE, Banniza S. 2017a. QTL mapping reveals genetic determinants of fungal disease resistance in the wild lentil Lens ervoides . Scientific Reports 7: 3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria V, Vijayan P, Wei Y, Banniza S. 2017b. Transcriptome analysis reveals a complex interplay between resistance and effector genes during the compatible lentil–Colletotrichum lentis interaction. Scientific Reports 7: 42338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Wu H, Churchill GA. 2003. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19: 889–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwaldt L, Anderson KL, Morrall RAA, Gossen BD, Bernier CC. 2004. Identification of lentil germplasm resistant to Colletotrichum truncatum and characterization of two pathogen races. Phytopathology 94: 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwaldt L, Morrall RAA, Chongo G, Bernier CC. 1996. Windborne dispersal of Colletotrichum truncatum and survival in infested lentil debris. Phytopathology 86: 1193–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Buiate EAS, Xavier KV, Moore N, Torres MF, Farman ML, Schardl CL, Vaillancourt LJ. 2017. A comparative genomic analysis of putative pathogenicity genes in the host‐specific sibling species Colletotrichum graminicola and Colletotrichum sublineola . BMC Genomics 18: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chongo G, Bernier CC. 2000. Effects of host, inoculum concentration, wetness duration, growth stage, and temperature on anthracnose of lentil. Plant Disease 84: 544–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chongo G, Bernier CC, Buchwaldt L. 1999. Control of anthracnose in lentil using partial resistance and fungicide applications. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 24: 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JJ. 2016. The Fusarium solani species complex: ubiquitous pathogens of agricultural importance. Molecular Plant Pathology 17: 146–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JJ, Wasmann CC, Usami T, White GJ, Temporini ED, McCluskey K, VanEtten HD. 2011. Characterization of the gene encoding pisatin demethylase (FoPDA1) in Fusarium oxysporum . Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 24: 1482–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch J, O'Connell R, Gan P, Buiate E, Torres MF, Beirn L, Shirasu K, Vaillancourt L. 2014. The genomics of Colletotrichum In: Dean R, Lichens‐Park A, Kole C, eds. Genomics of plant‐associated fungi: monocot pathogens. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Damm U, O'Connell RJ, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. 2014. The Colletotrichum destructivum species complex – hemibiotrophic pathogens of forage and field crops. Studies in Mycology 79: 49–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala JV, Tullu A, Banniza S, Séguin‐Swartz G, Vandenberg A. 2009. Interspecies transfer of resistance to anthracnose in lentil (Lens culinaris Medic.). Crop Science 49: 825–830. [Google Scholar]

- Gan P, Ikeda K, Irieda H, Narusaka M, O'Connell RJ, Narusaka Y, Takano Y, Kubo Y, Shirasu K. 2013. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the hemibiotrophic stage shift of Colletotrichum fungi. New Phytology 197: 1236–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan P, Narusaka M, Kumakura N, Tsushima A, Takano Y, Narusaka Y, Shirasu K. 2016. Genus‐wide comparative genome analyses of Colletotrichum species reveal specific gene family losses and gains during adaptation to specific infection lifestyles. Genome Biology and Evolution 8: 1467–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen BD, Anderson KL, Buchwaldt L. 2009. Host specificity of Colletotrichum truncatum from lentil. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 31: 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q. 2011. Full‐length transcriptome assembly from RNA‐Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology 29: 644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M et al 2013. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA‐Seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols 8: 1494–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall JG, Barratt RW. 1945. An improved grading system for measuring plant disease. Phytopathology 35: 655. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. 2005. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetics and Genome Research 110: 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi N, Seifuddin FT, Turner G, Haft D, Nierman WC, Wolfe KH, Fedorova ND. 2010. SMURF: genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genetics and Biology 47: 736–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozik A, Michelmore R. 2006. Suite of Python MadMapper scripts for quality control of genetic markers, group analysis and inference of linear order of markers on linkage groups. [WWW document] URL http://cgpdb.ucdavis.edu/XLinkage/MadMapper/ [accessed 11 December 2015].

- Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology 5: R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 35: 3100–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. 1997. tRNAscan‐SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 25: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna‐Martínez F, Rodríguez‐Guerra R, Victoria‐Campos M, Simpson J. 2007. Development of a molecular genetic linkage map for Colletotrichum lindemuthianum and segregation analysis of two avirulence genes. Current Genetics 51: 109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, He G, Chen Y, Pan Q, Liu Y et al 2012. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory‐efficient short‐read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrall RAA, Pedersen EA. 1991. Discovery of lentil anthracnose in Saskatchewan in 1990. Canadian Plant Disease Survey 71: 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell RJ, Thon MR, Hacquard S, Amyotte SG, Kleemann J, Torres MF, Damm U, Buiate EA, Epstein L, Alkan N et al 2012. Lifestyle transitions in plant pathogenic Colletotrichum fungi deciphered by genome and transcriptome analyses. Nature Genetics 44: 1060–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Methods 8: 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierleoni A, Martelli PL, Casadio R. 2008. PredGPI: a GPI anchor predictor. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaumann P, Schmidpeter J, Dahl M, Taher L, Koch C. 2018. A dispensable chromosome is required for virulence in the hemibiotrophic plant pathogen Colletotrichum higginsianum . Frontiers in Microbiology 9: e1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. EdgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single‐copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31: 3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A, Hubley R, Green P. 1996. RepeatMasker Open‐3.0. [WWW document] URL http://www.repeatmasker.org [accessed 15 January 2017].

- Solovyev V, Kosarev P, Seledsov I, Vorobyev D. 2006. Automatic annotation of eukaryotic genes, pseudogenes and promoters. Genome Biology 7: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer EL, von Heijne G, Krogh A. 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proceedings International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology 6: 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steentoft C, Vakhrushev SY, Joshi HJ, Kong Y, Vester‐Christensen MB, Schjoldager KT, Lavrsen K, Dabelsteen S, Pedersen NB, Marcos‐Silva L et al 2013. Precision mapping of the human O‐GalNAc glycoproteome through simple cell technology. EMBO Journal 32: 1478–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temporini ED, VanEtten HD. 2004. An analysis of the phylogenetic distribution of the pea pathogenicity genes of Nectria haematococca MPVI supports the hypothesis of their origin by horizontal transfer and uncovers a potentially new pathogen of garden pea: Neocosmospora boniensis . Current Genetics 46: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullu A, Buchwaldt L, Lulsdorf M, Banniza S, Barlow B, Slinkard AE, Sarker A, Tar'an B, Warkentin T, Vandenberg B. 2006. Sources of resistance to anthracnose (Colletotrichum truncatum) in wild Lens species. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 53: 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg A, Kiehn FA, Vera C, Gaudiel R, Buchwaldt L, Dueck S, Wahab J, Slinkard AE. 2002. CDC Robin lentil. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 82: 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Van Os H, Stam P, Visser R, Van Eck H. 2005. RECORD: a novel method for ordering loci on a genetic linkage map. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 112: 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng Z. 2012. Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5. [WWW document] URL http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart [accessed 15 February 2016].

- Yin Y, Mao X, Yang J, Chen X, Mao F, Xu Y. 2012. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate‐active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 40: W445–W451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampounis A, Pigné S, Dallery J‐F, Wittenberg AHJ, Zhou S, Schwartz DC, Thon MR, O'Connell RJ. 2016. Genome sequence and annotation of Colletotrichum higginsianum, a causal agent of crucifer anthracnose disease. Genome Announcement 4: e00821‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Fig. S1 Comparative analysis of secondary metabolite backbone genes in Colletotrichum species.

Fig. S2 Validation of the genetic linkage map of ascospore‐derived isolates originating from a cross between Colletotrichum lentis isolates CT‐30 and CT‐21.

Fig. S3 Genetic and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping.

Fig. S4 Colletotrichum lentis minichromosome 11.

Table S1 Libraries, sequencing platforms and sequence reads used to generate the Colletotrichum lentis genome assembly

Table S2 General feature format (gff) of Colletotrichum lentis protein‐coding gene models

Table S3 List and functional annotation of candidate effectors predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome

Table S4 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed cysteine‐rich candidate effectors of Colletotrichum lentis isolate CT‐30 in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S5 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed candidate effectors of Colletotrichum lentis containing < 3% cysteine residues in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S6 List and functional annotation of the secondary metabolite backbone genes predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome

Table S7 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed secondary metabolites of Colletotrichum lentis backbone genes in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S8 List and functional annotation of the carbohydrate‐active enzymes predicted in the Colletotrichum lentis genome and associated with the degradation of cell wall components and chitin binding

Table S9 Log2 fold change (log2FC) of differentially expressed genes of Colletotrichum lentis encoding carbohydrate‐active enzymes in susceptible lentil cultivar Eston

Table S10 Whole‐genome shotgun sequencing of Colletotrichum lentis population

Table S11 Segregation distortion of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers

Table S12 Colletotrichum lentis pseudomolecules/chromosomes

Table S13 qClVir11 haplotype: the qClVir11 region flanked by scaffold14p287381 and scaffold14p1129639 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers contains 1363 SNPs

Table S14 Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants with allele coverage ≥ 5 on minichromosome 12 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S15 Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants with allele coverage > 2 on minichromosome 12 of the progeny isolate GT‐2 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S16 Insertion/deletion (INDEL), presence/absence and polymorphism length on minichromosome 11 of Colletotrichum lentis

Table S17 List and functional annotation of candidate genes underlying the quantitative trait locus (QTL) qClVIR11 controlling the Colletotrichum lentis virulence on lentil, and expression data of CT‐21 and CT‐30 during the biotrophic and necrotrophic phases

Notes S1 RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐Seq) data analysis.