Abstract

Ca2+ regulates multiple processes in nerve terminals, including synaptic vesicle recruitment, priming, and fusion. Munc13s, the mammalian homologs of Caenorhabditis elegans Unc13, are essential vesicle-priming proteins and contain multiple regulatory domains that bind second messengers such as diacylglycerol and Ca2+/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM). Binding of Ca2+/CaM is necessary for the regulatory effect that allows Munc13-1 and ubMunc13-2 to promote short-term synaptic plasticity. However, the relative contributions of Ca2+ and Ca2+/CaM to vesicle priming and recruitment by Munc13 are not known. Here, we investigated the effect of Ca2+/CaM binding on ubMunc13-2 activity in chromaffin cells via membrane-capacitance measurements and a detailed simulation of the exocytotic machinery. Stimulating secretion under various basal Ca2+ concentrations from cells overexpressing either ubMunc13-2 or a ubMunc13-2 mutant deficient in CaM binding enabled a distinction between the effects of Ca2+ and Ca2+/CaM. We show that vesicle priming by ubMunc13-2 is Ca2+ dependent but independent of CaM binding to ubMunc13-2. However, Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 specifically promotes vesicle recruitment during ongoing stimulation. Based on the experimental data and our simulation, we propose that ubMunc13-2 is activated by two Ca2+-dependent processes: a slow activation mode operating at low Ca2+ concentrations, in which ubMunc13-2 acts as a priming switch, and a fast mode at high Ca2+ concentrations, in which ubMunc13-2 is activated in a Ca2+/CaM-dependent manner and accelerates vesicle recruitment and maturation during stimulation. These different Ca2+ activation steps determine the kinetic properties of exocytosis and vesicle recruitment and can thus alter plasticity and efficacy of transmitter release.

Keywords: Munc13, calmodulin, calcium, exocytosis, priming, chromaffin cell, kinetic modeling

Introduction

Information transfer at synapses is initiated by the fusion of neurotransmitter-containing vesicles with the plasma membrane and neurotransmitter release. Before fusion, vesicles translocate to and dock at the plasma membrane and then mature into a fusion-competent state in a process that is termed priming (Rettig and Neher, 2002; Richmond and Broadie, 2002; Sudhof, 2004; Becherer and Rettig, 2006) and represents an essential rate-limiting step in regulated exocytosis (Castillo et al., 2002; Lonart, 2002; Rosenmund et al., 2002). Priming and the vesicle fusion reaction itself require formation of a soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex between syntaxin 1/2 and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) and synaptobrevin/vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP 2) (Hanson et al., 1997; Fasshauer et al., 1998; Sutton et al., 1998; Weber et al., 1998; Jahn and Scheller, 2006). The dynamic regulation of priming determines the amount of neurotransmitter released and can modulate short-term synaptic plasticity (Xu et al., 1999; Lonart and Sudhof, 2000; Fergestad et al., 2001; Rettig and Neher, 2002).

Calcium ions (Ca2+) trigger the final step of vesicle fusion (Katz and Miledi, 1968) but also regulate other steps of the synaptic vesicle cycle such as vesicle priming before the stimulation, the recruitment and maturation of vesicles during stimulation, and vesicle endocytosis. Moreover, the degree of synaptic depression and enhancement during ongoing stimulation and the refilling of the pool of release-competent vesicles are highly dependent on residual free [Ca2+]i (Burgoyne and Morgan, 1995; Dittman and Regehr, 1998; Stevens and Wesseling, 1998; Wang and Kaczmarek, 1998; Gomis et al., 1999). Thus, Ca2+-dependent vesicle maturation accounts for adaptive changes in the synaptic parameters that lead to synaptic plasticity (Zucker, 1996). However, the Ca2+ sensor(s) responsible for these adaptive changes are not known in detail.

The Munc13 proteins Munc13-1, Munc13-2, and Munc13-3 constitute a family of brain-specific presynaptic proteins that are homologous to Caenorhabditis elegans Unc-13 (Brose et al., 1995, 2000). Munc13s are absolutely essential for synaptic vesicle priming and transmitter release in neurons (Aravamudan et al., 1999; Augustin et al., 1999; Richmond et al., 1999; Varoqueaux et al., 2002), and they can also prime secretory granules in chromaffin cells (Ashery et al., 2000). Munc13s are thought to exert their priming function by regulating the conformation of syntaxin 1/2 and its accessibility for SNARE-complex formation (Richmond et al., 2001; Stevens et al., 2005; McEwen et al., 2006). They are regulated by diacylglycerol binding to their C1 domains (Betz et al., 1998; Rhee et al., 2002), and by Ca2+/CaM binding to amphipathic helix motifs that are located adjacent to the C1 domains (Junge et al., 2004).

Ca2+/CaM binding to Munc13s plays a critical role in the activity-dependent plastic adaptation of transmitter release to changing demand, a process designated short-term synaptic plasticity (Zucker and Regehr, 2002; Junge et al., 2004). Ca2+/CaM binds to amphipathic helical structures in all Munc13 isoforms (Dimova et al., 2006), of which only the binding sites in Munc13-1 and the ubiquitously expressed Munc13-2 splice variant (ubMunc13-2) are homologous (Junge et al., 2004; Dimova et al., 2006). Loss-of-function mutations in the Ca2+/CaM-binding sites of Munc13-1 and ubMunc13-2 cause dramatic changes in short-term synaptic plasticity. This was attributed to the elimination of the allosteric activating effect that Ca2+/CaM binding exerts on Munc13s. However, the relative contributions of Ca2+ and CaM to vesicle priming and recruitment during stimulation by Munc13s are not known.

To investigate the contributions of Ca2+ and Ca2+/CaM in regulating ubMunc13-2 activity, we manipulated the Ca2+ concentration or the ability of ubMunc13-2 to bind CaM and examined the resulting effects on vesicle priming and recruitment in chromaffin cells. The effect of Ca2+ on exocytosis is well characterized in this cell type (Bittner and Holz, 1992; Burgoyne and Morgan, 1997; Smith et al., 1998; Voets, 2000; Rettig and Neher, 2002), although a link to Munc13 has not yet been determined. In addition, the role of CaM in chromaffin cells is essentially unknown, although it has been suggested to act in late stages of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis in chromaffin and in PC12 cells (Chamberlain et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1999). We focused our study on ubMunc13-2 because it is expressed in chromaffin cells, and its activity is more dramatically regulated by Ca2+/CaM than that of any other known Munc13 variant (Junge et al., 2004).

Materials and Methods

Chromaffin cell preparation and infection.

Isolated bovine adrenal chromaffin cells were prepared and cultured as described previously (Ashery et al., 1999; Yizhar et al., 2004). Cells were used 2–3 d after preparation. Infection was performed on cultured cells 5–48 h after plating (Ashery et al., 1999). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals were detected using an IX-50 Olympus Optical (Tokyo, Japan) microscope with a filter set for enhanced GFP (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany). The expression levels of ubMunc13-2–enhanced GFP (EGFP) and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP were similar as determined by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence staining (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Membrane-capacitance measurements.

Conventional whole-cell recordings and capacitance measurements were performed as described previously (Yizhar et al., 2004; Nili et al., 2006) and analyzed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). The external bath solution contained the following: 140 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, and 2 mg/ml glucose, pH 7.2, 320 mOsm. For flash photolysis experiments, the internal pipette solution consisted the following (in mm): 105 cesium glutamate, 2 MgATP, 0.3 GTP, 33 HEPES, and 0.33 Fura2FF (TefLabs, Austin, TX) (300 mOsm). The basal Ca2+ for the experiment at high Ca2+ conditions was buffered by a combination of 4 mm CaCl2 and 5 mm o-nitrophenyl (NP)-EGTA (G. Ellis-Davis, MCP Hahnemann University, Philadelphia, PA) to give a free [Ca2+]i of 400 nm (Yizhar et al., 2004; Nili et al., 2006). For the low-priming experiments, cells were dialyzed for 2 min with an internal solution buffered with NP-EGTA to titrate the basal Ca2+ concentration to 100 nm, as measured with Fura2 (NP-EGTA at 5 mm; Ca2+ at 2.8 mm). Experiments were performed 8–16 h after infection at 30–32°C. The analysis and comparison were always performed from pairs of control and Munc13-overexpressing cells from the same batch of cells. We excluded from the analysis cells that had a leak above 50 pA, basal Ca2+ concentrations above 500 nm, post-flash Ca2+ above 30 μm, access resistance above 20 MΩ, or cells that showed spontaneous changes in membrane capacitance that exceeded 10% of the cell surface area. We found that there is a linear relationship between GFP fluorescence and expression levels of ubMunc13-2 (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), similar to our previous findings with tomosyn (Yizhar et al., 2004, 2007). Therefore, to minimize the effects of cell-to-cell variation in our comparative electrophysiological experiments as a result of different expression levels, we systematically selected cells that exhibited similar EGFP fluorescence levels. GFP fluorescence for each cell was measured on the electrophysiological setup before the experiment using a photometric system (T.I.L.L Photonics)and the photomultiplier (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan).

Photolysis of caged Ca2+ and [Ca2+]i measurements.

Flashes of UV light were generated by a flash lamp (T.I.L.L. Photonics), and fluorescent excitation light was generated by a monochromator (T.I.L.L. Photonics). The monochromator and flash lamp were coupled using a Dual Port condenser (T.I.L.L. Photonics) into the epifluorescence port of an IX-50 Olympus Optical microscope equipped with a 40× objective (UAPO/340; Olympus Optical). Fura2FF was excited at 350/380 nm and detected through a 500 nm long-pass filter (T.I.L.L Photonics).

Amperometry.

Amperometric activity was detected using 10 μm carbon fiber electrodes prepared as described previously (Ashery et al., 2000; Yizhar et al., 2004). A constant voltage of 800 mV versus an Ag/AgCl reference was applied to the electrode. The tip of the carbon fiber electrode was gently pressed against the cell surface. The amperometric current was recorded using an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). Signals were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2.9 kHz. Data were analyzed with Igor Pro.

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy.

To detect vesicles in cells expressing ubMunc13-2, vesicles were labeled with neuropeptide-Y (NPY)–monomeric red fluorescence protein (mRFP). Cells were electroporated immediately after culturing with 40 μg of DNA encoding NPY–mRFP. After 24 h, the cells were replated on glass coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and infected with Semliki Forest virus (SFV) coding for ubMunc13-2–EFGP or for EGFP as control and imaged the following day. EGFP- and ubMunc13-2–EFGP-overexpressing cells were always imaged on the same day and after an identical infection time. Expression level of NPY–mRFP was quantified by comparing the fluorescence intensity of the cells in an optical section performed at the middle of the cells and was found to be similar in cells expressing EGFP or ubMunc13-2–EFGP (data not shown). Imaging was performed with an Olympus Optical IX-70 inverted microscope with a 60×, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRF) objective (numerical aperture 1.45; Olympus Optical) and a T.I.L.L Photonics TIRF condenser. Laser excitation was provided by two solid-state lasers (Laser Quantum, Stockport, UK) emitting at 473 nm to monitor GFP in transfected cells and 532 nm to monitor vesicles expressing NPY–mRFP. An Andor Ixon 887 EMCCD camera (Andor, Belfast, Northern Ireland) was used to acquire images and was controlled by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). Vesicles were identified according to their distinct point-spread function fluorescence using a custom-written algorithm.

Binding of ubMunc13-2–EGFP to calmodulin.

To prepare ubMunc13-2–EGFP protein for binding assays, BHK21 cells were infected by SFV encoding a full-length ubMunc13-2–EGFP fusion protein (Ashery et al., 1999). After overnight incubation, cells were washed with PBS and subjected to (2 ml of) lysis solution, composed of 60 μm digitonin, 140 mm K-glutamate, 2 mm MgCl2, 20 mm HEPES–KOH, and 200 μm BAPTA, for 20 min at room temperature (RT). The incubating solution (containing ubMunc13-2–EGFP that had diffused out of the cells, i.e., ubMunc13-2–EGFP solution) was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 7 min to remove cell debris. The ubMunc13-2–EGFP solution was then collected, and BAPTA and Ca2+ were added to reach Ca2+concentrations of (0 nm, 50 nm, 100 nm, 250 nm, 500 nm, 10 μm, and 10 mm). Solutions contained 5 mm BAPTA and Ca2+ at 0, 0.83, 1.3, 2.6, 3.4, or 4.8 mm. The 10 mm Ca2+ solution did not contain BAPTA. The free Ca2+ concentration was calculated by an Igor macro and verified on the calibrated electrophysiological setup with Fura2. For the preparation of calmodulin agarose beads, seven aliquots of 30 μl bead solution (P-4385; Sigma) were extensively washed, each with the appropriate preactivation solution, and centrifuged at 200–300 × g for 1 min. The preactivation solutions were composed of 10 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.5, 150 mm NaCl, and a combination of BAPTA and Ca2+ to reach 0, 50 nm, 100 nm, 250 nm, 500 nm, 10 μm, and 10 mm free Ca2+. The beads were then incubated with the ubMunc13-2–EGFP solutions, containing the respective Ca2+ concentrations for 15 min at RT. After the incubation step, the beads were separated from incubation solution by centrifugation at 200–300 × g for 1 min and washed twice, and fluorescent images were taken with a conventional fluorescence microscope equipped with a GFP filter set (TE 2000-S; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). For quantification of ubMunc13-2–EGFP fluorescence on the beads, we used a conventional Nikon microscope (Nikon Eclipse, TE2000-S) equipped with an Ecite lamp for excitation and with a CoolSNAP HQ camera for acquisition (Roper Scientific, Fort Lauderdale, FL). The fluorescent intensity was measured with ImagePro (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) from the circumference of the beads, and local background fluorescence was subtracted. Data from the beads were pooled and averaged to give the averaged fluorescence intensity for each Ca2+ concentration. After the fluorescence inspection, ubMunc13-2 was extracted from the beads by SDS and quantified by Western blotting using specific anti-ubMunc13-2 antibodies. The averaged intensities of the bands were quantified. As control, we used either GFP or ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP. No fluorescence was detected on the beads when using GFP or ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP extracted from cells at all Ca2+ concentrations (data not shown). However, at 10 mm Ca2+, some faint nonspecific binding to the CaM beads was observed for ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP.

Western blotting and immunostaining.

Freshly isolated bovine chromaffin cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 100 × g for 10 min, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then thawed and homogenized in buffer containing 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 320 mm sucrose, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin. Protein concentration was determined by BCA (Pierce, Rockford, IL) assay and adjusted to 2 mg/ml in Laemli's sample buffer. The samples were run in parallel with adult rat brain homogenate (used as positive control) by SDS-PAGE (20 μg/lane). After blotting, nitrocellulose membranes were probed with Munc13 isoform-specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against recombinant protein fragments (Munc13-1, residues 3–317; bMunc13-2, residues 1–305; ubMunc13-2, residues 182–407; Munc13-3, residues 294–574).

Detection of expression of ubMunc13-2–EGFP and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP in chromaffin cells was done as described previously (Yizhar et al., 2007). Briefly, ubMunc13-2–EGFP and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP were expressed in chromaffin cells for 18 h and processed as described above. For immunostaining, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde–1× PBS (Nili et al., 2006), pH 7.4, for 30 min at RT and then washed once with 1× PBS. The anti-ubMunc13-2 antibody was applied overnight at 4°C. A secondary antibody was applied in blocking buffer for 1 h at RT. Epifluorescence images of randomly selected fields were acquired under both 488 and 546 nm excitation wavelengths with the appropriate filter sets for GFP and rhodamine detection, and the average fluorescence at both wavelengths was then calculated for single cells after subtraction of local off-cell background.

The model system.

The process of exocytosis is presented as an array of interactions between synaptic proteins (see Fig. 6). Each step consists of a reaction between one or two reactants and is characterized by forward and backward rate constants. The ratio between the off-rate constants (koff) and the on-rate constants (kon) is equal to the equilibrium constant (Keq). The reaction mechanism is basically linear, in which the product of one step is the reactant for the next. The model in this manuscript is an extension of a formal model presented previously (Mezer et al., 2004, 2006). A detailed description of the logic underlying the model was published previously (Mezer et al., 2004). Briefly, the modeling of the exocytotic process was started with the reaction between SNAP-25 and syntaxin I to form the binary SNARE complex. This complex reacts with the third SNARE protein, the synaptobrevin/VAMP 2, to form the mature ternary SNARE complex. The process moves forward by sequential activation steps. The SNARE complex can be activated by two factors that operate in parallel. The activation can be effected by a general priming factor (PFA) or, alternatively, as presented in detail in this manuscript, by activated ubMunc13-2. The activation of ubMunc13-2 is described in Scheme I and was designed to describe the Ca2+ and CaM effects on the activity of ubMunc13-2 (a detailed description can be found in Results). Whereas PFA is activated by Ca2+ and accounts for the general Ca2+-dependent priming of chromaffin cells, ubMunc13-2 is activated by CaM and several Ca2+-binding steps, which enhance priming only when ubMunc13-2 is expressed. Both the activated ubMunc13-2 and PFA activate the SNARE complex to the SNARE′ state, which in turn interacts with Ca2+ ions and synaptic proteins (complexin and synaptotagmin) to form the release complexes RCI and RCII. We have shown that these release complexes correspond to the readily releasable pool (RRP) and slowly releasable pool (SRP), respectively. Finally, the cascade drives vesicle fusion from RCI and RCII with the cell membrane during Ca2+ binding. The steps beyond the ubMunc13-2 pathway were kept constant according to the previously described parameters (Mezer et al., 2004, 2006).

Figure 6.

The sequence of events used in the model to simulate the exocytotic process with ubMunc13-2 and Ca2+/CaM. All reaction steps are arranged as published previously (Mezer et al., 2004) and are elaborated in Materials and Methods. A parallel pathway was added on the right to account for the effect of ubMunc13-2 and CaM. The parameters for the rate constants are listed in Table 2.

Genetic algorithm.

To search for the rate and concentration constants of the model in the high-dimensional optimization space, we applied the genetic algorithm search technique as described previously (Mezer et al., 2006). Briefly, each generation consisted of 100 “genotypes,” each of them having a random set of adjustable parameters that were selected from within the permitted range (see Table 2). For any given set of parameter values, the ordinary differential equations can be solved using standard numerical subroutines such as Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) ODE23s. The program used these values to reconstruct the experimental control ubMunc13-2 overexpression data. The level of agreement between the experimental data and the numerical solutions can be expressed by a fitness function, which is weighed as an average of the squares of the differences between the calculated solutions and the measured signals and is normalized with respect to the calculated signal. At the end of the generation, the best-fit phenotype was cloned and replaced the worst fitting one. The genetic algorithm was evolved using “genes” manipulated by the following alterations: two heuristicXover, two arithXover, two simpleXover, four boundaryMutation, five multiNonUnifMutation, 10 nonUnifMutation, and two unifMutation. All these genetic manipulations are standard procedures and defined in the GAOT program of Matlab (Houck et al., 1995). The fitness function was calculated for all new combinations, and their values were evaluated both among the present generation and with respect to those genotypes of the previous generation. The length of a 1500-generation run required 10–20 h, depending on the processor in use. The genetic algorithm search was repeated 15 times, and the search results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The kinetics, equilibrium, and concentration constants of reactions 0′-1 to 0′-3 and 3a that reconstruct the fusion dynamics with the ubMunc13-2-overexpressing cells

| No. | Reaction | Mean value | SDs | Search range | Result range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0′-1a | CaM + Munc13 ⇆ CaM-Munc13 | [Munc13] = 1.8e-8 | 1.1e-8 | 1e-10 to 1e-7 | 1e-7 to 4.5e-7 |

| kon = 1.3e4 | 7.5e3 | 1e1 to 1e9 | 1.3e3 to 2.1e4 | ||

| Kd = 2.5e-6 | 2.2e-6 | 1e-10 to 1e-5 | 9e-7 to 8e-6 | ||

| 0′-1b | CaM–Munc13 + Ca2+ ⇆ CaM–Munc13′ | [CaM] = 1e-6 | No search | No search | No search |

| (in excess) | |||||

| kon = 6.35 1e8 | 2.5e9 | 1e6 to 1e10 | 3e6 to 1e10 | ||

| Kd = 2.5e-7 | 1e-7 | 1e-14 to 1e-5 | 5e-8 to 5e-7 | ||

| 0′-2 | CaM–Munc13′ + Ca2+ ⇆ CaM–Munc13″ | kon = 6.4e6 | 5e7 | 1e6 to 1e9 | 5.3e6 to 7.4e6 |

| Kd = 7e-6 | 3e-7 | 1e-8 to 1e-5 | 1e-6 to 1e-5 | ||

| 0′- 3 | CaM–Munc13″ + Ca2+ ⇆ CaM–Munc13‴ | kon = 2.6e8 | 3.2e8 | 1e6 to 1e9 | 1e7 to 1e9 |

| Kd = 5.6e-6 | 2.5e-6 | 1e-8 to 1e-5 | 2e-6 to 1e-5 | ||

| 3a | CaM–Munc13‴ + SNARE ⇆ CaM–Munc13–SNARE (= SNARE′) | kon = 9.5e10 | 1. e10 | 1e6 to 1e11 | 5e10 to 1e11 |

| Kd = 3e-9 | 1.5e-9 | 1e-13 to 1e-7 | 9e-10 to 5e-9 |

The parameters are results of the genetic algorithm searching method. For each parameter, we present the mean value, SDs, the search range, and the result range.

Range of variance set for the adjustable parameters.

The signals were reconstructed by a search in a multidimensional parameter space for the unknown rate and concentration constants. In the present work, the genetic algorithm search was performed for 11 parameters for the new equations that describe the ubMunc13-2 interaction with Ca2+, CaM, and SNAREs (see Table 2 and Scheme 1). The rate and equilibrium constants were allowed to vary from the upper limit set by the Debye–Smoluchowski equation (Gutman and Nachliel, 1997) to a few orders of magnitude below it (see Table 2). The concentration of CaM, which is the most abundant protein in the cell, was set to 1 μm. In addition, the rate and equilibrium constants that define the control secretion in cells that do not express Munc13-2 were kept as published (Mezer et al., 2006). All definitions of the adjustable parameters, the upper and lower limits, and the final values derived by the analysis are listed in Table 2.

Results

Ca2+-dependent CaM binding to ubMunc13-2

The interaction between the isolated CaM-binding domain of ubMunc13-2 and CaM is tightly regulated by Ca2+ and occurs at Ca2+ concentrations as low as 20–30 nm (Dimova et al., 2006). To determine the Ca2+ concentration necessary for CaM binding to full-length ubMunc13-2, we performed binding experiments of ubMunc13-2 to CaM-agarose beads. ubMunc13-2–EGFP was expressed in BHK21 cells for 24 h, and the cells were then permeabilized and ubMunc13-2–EGFP was allowed to diffuse from the cells into the medium. The medium containing ubMunc13-2–EGFP was collected, depleted of cell debris by centrifugation, and divided into samples containing increasing calcium concentrations [0 nm (5 mm BAPTA), 50 nm, 100 nm, 250 nm, 500 nm, 10 μm, and 10 mm]. Each sample was incubated with CaM-agarose beads for 15 min, and then the beads were washed extensively. The amount of ubMunc13-2–EGFP bound to the beads was determined by quantifying the bead fluorescence and, in parallel, by quantitative Western blotting. Both types of analysis demonstrated a strong dependence of CaM binding to ubMunc13-2–EGFP on the Ca2+ concentration, with an EC50 for [Ca2+] of ∼100 nm (Fig. 1). Thus, even in resting cells, in which the [Ca+2]i is in the range of 50–100 nm, up to 50% of the ubMunc13-2 molecules may be associated with CaM.

Figure 1.

Ca2+-dependent ubMunc13-2 binding to CaM. A, Fluorescent images of the CaM-bound agarose beads exposed to ubMunc13-2–EGFP protein at varying Ca2+ concentrations. In the absence of Ca2+ (0 nm; 5 mm BAPTA), no GFP fluorescence was detected on the beads. However, at as little as 100 nm Ca2+, typical GFP staining was observed at the rim of the beads. B, Western blot determination of ubMunc13-2 protein levels extracted from the CaM-agarose beads. C, Averaged concentration dependence of Ca2+-induced ubMunc13-2–EGFP binding to the CaM-agarose beads. The data points represent quantification of the bead fluorescence (black squares), quantification of the Western blot bands (gray circles), or the simulation of the concentration-dependent curve according to the parameters obtained with the expanded mechanistic model (white circles) (for more details, see Results).

ubMunc13-2 acts as a priming factor for chromaffin granules

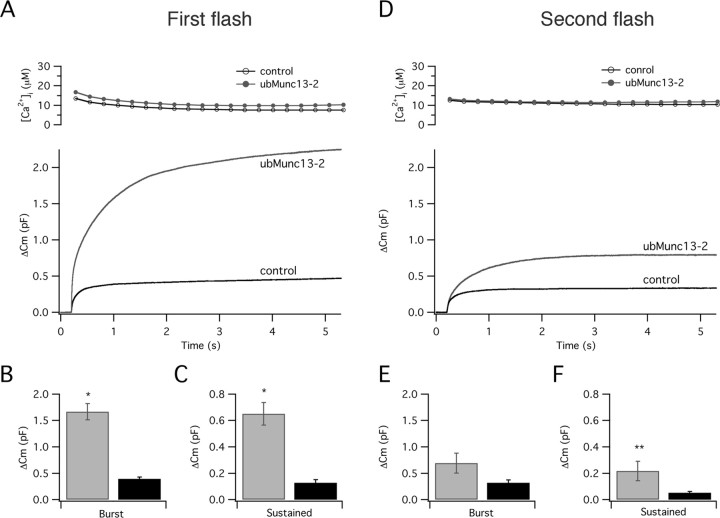

As a baseline for our study, we characterized the effect of ubMunc13-2 on secretion from bovine chromaffin cells. We first verified that this isoform is expressed in bovine chromaffin cells and found very low levels of expression of ubMunc13-2 together with Munc13-1, as published previously (Ashery et al., 2000), and Munc13-3 (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We performed the present study on ubMunc13-2 because its activity is more significantly regulated by Ca2+/CaM than that of any other known Munc13 variant (Junge et al., 2004). To study the effects of ubMunc13-2 on chromaffin granule secretion, we overexpressed ubMunc13-2–EGFP in bovine chromaffin cells using the SFV expression system (Ashery et al., 1999; Yizhar et al., 2004). We stimulated exocytosis by flash photolysis of caged Ca2+, which causes step-like increases in [Ca+2]i, and followed exocytosis by measuring changes in membrane capacitance. Control cells displayed a typical biphasic increase in membrane capacitance, in which an exocytotic burst is followed by a sustained phase of secretion (Fig. 2). The exocytotic burst results from the fusion of a pool of fusion-competent vesicles, whereas the sustained phase represents the fusion of vesicles that are recruited and undergo priming from an unprimed pool during the Ca2+ pulse (Ashery et al., 2000; Neher, 2006). In the present study, we will use the term vesicle priming to refer to the process of vesicle maturation before the pulse and the term vesicle recruitment to refer to the process of vesicle maturation and priming that occurs during stimulation (Kushmerick et al., 2006; Neher, 2006; Sakaba, 2006). Overexpression of ubMunc13-2–EGFP significantly enhanced both the exocytotic burst and the sustained exocytosis component (Fig. 2B,C). Thus, the increased exocytotic burst indicated that ubMunc13-2–EGFP enhances priming and increases the number of fusion-competent vesicles under resting conditions, whereas the increased sustained component implied that ubMunc13-2–EGFP also accelerates vesicle recruitment and priming during the stimulation.

Figure 2.

ubMunc13-2 overexpression enhances secretion in chromaffin cells. A, Averaged calcium ([Ca2+]i, top trace) and capacitance changes (Cm, bottom trace) in control, noninfected cells (n = 43) and ubMunc13-2 cells (n = 38) in response to flash photolysis of caged Ca2+. The response to the first flash stimulation was significantly larger in ubMunc13-2 cells than in controls. The bar panel represents the average increase in capacitance during the exocytotic burst (0–1 s) (B) and during the sustained component (1–5 s) (C). B, Burst: 395 ± 37 fF in control cells, 1670 ± 157 fF in ubMunc13-2 cells. C, Sustained component: 127 ± 23.1 fF in control cells, 651 ± 85.1 fF in ubMunc13-2 cells. D, The response to the second flash stimulation was still larger in ubMunc13-2 cells than in control cells. E, Burs: 316 ± 56.4 fF in control cells, 694 ± 187 fF in ubMunc13-2 cells. F, Sustained component: 51.5 ± 10.1 fF in control cells, 216 ± 74.6 fF in ubMunc13-2 cells. [Ca2+]i was set to ∼400 nm for 30 s before the stimulation: 380 ± 33 nm for ubMunc13-2; 410 ± 22 nm for control cells. Bars represent mean ± SEM; *p < 0.001; **p < 0.01.

We next analyzed the effect of ubMunc13-2–EGFP overexpression on the two burst components by multiple exponential fitting (Xu et al., 1998; Voets, 2000). The fast burst component (τ of ∼30 ms) results from the fusion of vesicles from an RRP, whereas the slow phase (τ of ∼300 ms) represents the fusion of vesicles from the SRP (Xu et al., 1998). We found the size of the RRP to be enhanced by a factor of 3.8 and that of the SRP by a factor of 5 compared with control cells (Table 1). The time constant of release from the RRP was similar in overexpressing and control cells, whereas the time constant of release from the SRP was slower in overexpressing cells compared with control cells (Table 1). A comparison between the normalized capacitance curves of control and ubMunc13-2–EGFP-overexpressing cells confirmed the apparently slower and larger SRP component in the latter (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that ubMunc13-2 alters the kinetics of the slow burst component. However, it should be noted that, using the simulation approach, we found that the slower time constant was not attributable to the slower release from the SRP but rather to slower maturation of vesicles during the pulse, which caused the apparent slow release (for more details, see Figs. 5, 6).

Table 1.

Effect of ubMunc13-2 and ubMunc13-2W387R on the different kinetics components of the exocytotic burst

| RRP |

SRP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time constant | Amplitude | Time constant | Amplitude | |

| ubMunc13-2 | 17.85 ± 1.42 (n = 38) | 612.79 ± 86.20 (n = 38) | 440.16 ± 42.84 (n = 38) | 1063.78 ± 134.62 (n = 38) |

| Control | 19.55 ± 2.20 (n = 43) | 159.27 ± 22.42 (n = 43) | 195.08 ± 18.47 (n = 43) | 211.32 ± 22.10 (n = 43) |

| ubMunc13-2W387R | 19.18 ± 2.45 (n = 31) | 520.54 ± 67.75 (n = 31) | 286.18 ± 39.11 (n = 31) | 462.51 ± 57.54 (n = 31) |

| Control | 23.46 ± 2.89 (n = 32) | 176.83 ± 33.40 (n = 32) | 240.23 ± 28.06 (n = 32) | 214.96 ± 20.94 (n = 32) |

Figure 3.

CaM interaction with ubMunc13-2 enhances the activity of ubMunc13-2 and specifically affects the slow burst component. A, Averaged membrane-capacitance measurements of ubMunc13-2 (gray, ubMunc13-2), ubMunc13-2W387R (light gray; W387R), and control cells (black, control). Comparison of the capacitance traces reveals that the interaction of CaM with ubMunc13-2 enhances exocytosis and contributes mainly to increased secretion in the second phase of the burst component (slow burst). Burst amplitudes: ubMunc13-2-EGFP, 1670 ± 157 fF; ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP, 1227 ± 101 fF; control, 409 ± 29 fF; and sustained component: ubMunc13-2–EGFP, 651 ± 85 fF; ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP, 475 ± 101 fF; control, 93 ± 39 fF. [Ca2+]i was set to ∼400 nm for 30 s before the stimulation: 380 ± 33 nm for ubMunc13-2, n = 38; 370 ± 43 nm for ubMunc13-2W387R, n = 31; 410 ± 22 nm for control, n = 43. B, The normalized dynamics of secretion in ubMunc13-2 (gray), ubMunc13-2W387R (light gray), and control cells (black). C, Membrane-capacitance increase in response to 30 depolarization pulses to +10 mV for 40 ms at 4 Hz for ubMunc13-2 (gray), ubMunc13-2W387R (light gray), and control cells (black). D, The increase in membrane capacitance for each depolarization pulse (taken from C). Notice that, although ubMunc13-2 and ubMunc13-2W387R secrete to a similar extent in the first 3–4 depolarization pulses, ubMunc13-2 maintained higher secretion at later depolarization pulses as well.

Figure 5.

Simulation of the experimental data by the exocytosis mechanistic model. The experimental and simulated fusion reactions were measured for control and overexpressing cells under priming and low-priming conditions. A, Reconstruction of the secretion in control cells either with priming (top curves; experimental, black; reconstructed, gray) or under low priming (bottom curves; experimental, black; reconstructed, gray). B, Reconstruction of secretion in ubMunc13-2- and ubMunc13-2W387R-overexpressing cells. Each set of curves corresponds to experimental (black lines) or reconstructed (gray lines) dynamics: i, ubMunc13-2 cells under priming conditions; ii, ubMunc13-2W387R cells under priming conditions; iii, ubMunc13-2 cells under low-priming conditions; iv, ubMunc13-2W387R cells under low-priming conditions. C, Subtraction of the experimental control curves from the corresponding curves of the overexpression conditions. The traces correspond to four scenarios: i, ubMunc13-2 cells under priming conditions; ii, ubMunc13-2W387R cells under priming conditions; iii, ubMunc13-2 cells under low-priming conditions; iv, ubMunc13-2W387R cells under low-priming conditions. The response onset is indicated by an arrow.

The enhanced exocytotic burst in ubMunc13-2–EGFP-overexpressing cells could result from an increase in either the number of docked vesicles or the number of primed vesicles. To distinguish between the two possibilities, we quantified the number of docked vesicles using TIRF. To selectively stain vesicles, cells were electroporated with a plasmid carrying the gene coding for vesicular protein NPY, in frame with the gene coding for mRFP (Campbell et al., 2002). After 24 h, the NPY–mRFP-expressing cells were infected with SFV encoding the ubMunc13-2–GFP fusion protein or SFV encoding GFP as a control. Cells overexpressing GFP or ubMunc13-2–GFP together with NPY–mRFP were taken for the TIRF measurements, and images of the footprints of the cells were taken. Because the footprint of each cell is different, we measured the footprint area according to the GFP fluorescence detected by excitation at 473 nm. The mRFP-labeled vesicles were detected by light excitation at 532 nm. The number of vesicles per cell was calculated by dividing the number of visible vesicles in the evanescent field by the footprint surface area. We found that the number of vesicles located within the evanescent field was not altered by overexpression of ubMunc13-2–EGFP (ubMunc13-2 cells: 0.35 vesicles/μm2 ± 0.08, n = 7; control cells: 0.28 vesicles/μm2 ± 0.02, n = 7), indicating that ubMunc13-2–EGFP acts at a postdocking step and enhances vesicle priming, similar to Munc13-1–EGFP (Ashery et al., 2000).

The larger sustained component in Munc13-2–EGFP-overexpressing cells compared with control cells indicated that ubMunc13-2–EGFP also enhances vesicle recruitment during the stimulation. It is also possible that ubMunc13-2–EGFP enhances vesicle replenishment after the stimulation, as seen in neurons overexpressing ubMunc13-2–EGFP (Junge et al., 2004). To investigate this in more detail, we performed experiments with paired flash stimulations given at a 2-min interval. The response of the same cell to the second flash stimulation characterizes its ability to replenish releasable vesicle pools that were depleted by the first flash stimulation. The exocytotic response to the second flash stimulation in ubMunc13-2–EGFP-overexpressing cells was still larger than that of control cells, indicating that ubMunc13-2–EGFP also improves vesicle replenishment between the two stimulations. This feature seems to be specific to ubMunc13-2–EGFP because overexpression of Munc13-1–EGFP does not have any such effect on vesicle replenishment (Ashery et al., 2000). This is in agreement with the larger augmentation seen in ubMunc13-2-expressing neurons compared with Munc13-1-expressing neurons after a high-frequency stimulation period (Rosenmund et al., 2002; Junge et al., 2004).

Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 affects the slow burst component

The findings of the previous experiment indicate that ubMunc13-2 enhances both vesicle priming under resting conditions (measured as an enhanced burst component) and vesicle recruitment during the calcium pulse (measured as an increased sustained component). To differentiate between the effect of Ca2+ and the effect of CaM on the activity of ubMunc13-2 in vesicle priming and recruitment, we performed the following experiments. In a first set of experiments, we investigated how Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 affects its function. This was done overexpressing the Ca2+/CaM-binding-deficient mutant, ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP (Junge et al., 2004) in the cells. In a second set of experiments, we lowered the basal calcium concentration to evaluate the effect of calcium on ubMunc13-2 priming activity (see below).

Exocytosis from cells overexpressing ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP was increased compared with that of control cells, but this increase was less pronounced than that seen during overexpression of ubMunc13-2–EGFP (Fig. 3A). The exocytotic burst was enhanced only twofold in cells expressing ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP compared with 3.8-fold in ubMunc13-2-EGFP–expressing cells. The sustained release component in cells expressing ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP was four times larger than in control cells and similar to that in cells expressing ubMunc13-2–EGFP (Fig. 3A).

Additional analysis of the burst components demonstrated that the RRP in cells expressing ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP was increased by a factor of 2.5 compared with control cells (Table 1). The ability of ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP to increase the RRP size indicates that granule priming to the RRP by ubMunc13-2 is only partially dependent on Ca2+/CaM binding. Interestingly, the main difference between ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells was the significant secretion during the second phase of the burst (SRP), which was evident only in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells (Fig. 3A). Although the slow burst component in ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells was increased by only a factor of ∼2, it was increased by a factor of ∼5 in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells (Table 1). This indicates that Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2–EGFP accelerates the rate of vesicle recruitment during the Ca2+ pulse, which leads to an increase in the size of the SRP.

The previous set of experiments revealed that robust stimulation that raises Ca2+ to relatively high levels (above 10 μm) causes significantly more secretion in ubMunc13-2 cells. We next performed additional experiments using more subtle physiological stimulations (Seward and Nowycky, 1996; Engisch et al., 1997; Chan and Smith, 2001). We applied either trains of action potentials or trains of short depolarization pulses (30 pulses of 10–40 ms each at 4 Hz). In the experiments presented in Figure 3, C and D, cells were stimulated with 30 depolarization pulses at 4 Hz. Secretion in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells was four to five times larger compared with secretion from control, noninfected cells, whereas secretion from ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells was larger than in controls but smaller than in ubMunc13-2 cells (Fig. 3C). Secretion during the first depolarization was similar in ubMunc13-2–EGFP and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells, and both were larger than in control cells. In addition, in ubMunc13-2 cells, an additional increase in secretion was evident at later stages of the stimulation (Fig. 3D, from the 4th to the 10th depolarization pulses). This effect was not detected in control or ubMunc13-2W387R cells, indicating that this enhancement depends specifically on Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2.

These sets of experiments demonstrated that the basal priming activity of ubMunc13-2 is almost independent of Ca2+/CaM binding and that the vesicle recruitment/maturation activity of ubMunc13-2 during prolonged stimulation is boosted by Ca2+/CaM binding at high [Ca2+]. Therefore, we hypothesize that there are two modes of Ca2+-dependent activation of ubMunc13-2. One mode is independent of CaM binding and corresponds to basal priming, and a second, Ca2+/CaM-dependent mode is effective at high Ca2+ concentration. The latter mode of activation causes the slow, intense SRP-like secretion. The next set of experiments verified and extended this hypothesis.

Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 enhances vesicle recruitment at high [Ca2+]i

The priming reaction in chromaffin cells is highly dependent on [Ca2+]i, and various mechanisms have been suggested to explain this Ca2+ dependence (Bittner and Holz, 1992; von Ruden and Neher, 1993; Smith et al., 1998; Voets, 2000). In the previous set of experiments, [Ca2+]i was set to ∼400 nm for 30 s before the stimulation (Figs. 2, 3) to achieve high priming conditions. Given that ubMunc13-2 has several putative Ca2+-binding domains (Basu et al., 2007), we decided to test whether the priming activity of ubMunc13-2 depends on the basal Ca2+ concentration. To evaluate the Ca2+ dependence of priming in overexpressing cells, we lowered the basal [Ca2+]i before the flash to ∼100 nm, thus creating conditions that barely support Ca2+-dependent priming in chromaffin cells (Smith et al., 1998; Voets, 2000), and monitored the responses of those cells to flash stimulation (Voets, 2000). In response to the flash stimulation, the initial release phase, which lasted ∼50–100 ms, had similar amplitudes in control, ubMunc13-2–EGFP-expressing and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 4A,C). This phase represents the secretion of those few vesicles that were primed at 100 nm [Ca2+]i. Beyond this time point, the three curves strongly diverged. The control cells showed a slow but steady sustained release component (Fig. 4A,C). The ubMunc13-2–EGFP-expressing cells entered a phase of robust release, which started with a delay and exhibited overall S-shaped kinetics (Fig. 4A,B). In ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells, this S-shape was not observed, but a larger sustained-release phase, exceeding that of control cells by a factor of 2, was still detectable (Fig. 4A,C).

Figure 4.

CaM stimulates ubMunc13-2 activity at high Ca2+ levels. A, The average secretion responses of cells overexpressing ubMunc13-2 (gray, ubMunc13-2, n = 21) or ubMunc13-2W387R (light gray, W387R, n = 23) and control cells (black, control, n = 37) under conditions of low preflash calcium (low-priming conditions). The initial secretion in control, ubMunc13-2–EGFP-expressing, and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP-expressing cells was low in response to the flash stimulation. ubMunc13-2–EGFP-expressing cells showed a robust S-shaped release time course that started with a 250 ms delay after the flash (gray curve). B, The capacitance increase in ubMunc13-2 cells (gray trace) after a small RRP-like secretion step (1) displays linear dynamics for the next 200–250 ms (2) until the beginning of secretion with exponential kinetics (3, S-shape-like secretion). In ubMunc13-2W387R (light gray curve) and control (black trace) cells, only the first RRP-like phase is similar to ubMunc13-2. C, The bar panel represents a quantitative comparison of the different secretion phases. During the initial 100 ms, secretion was low in all cells, indicating reduced priming of vesicles to the releasable pools at low basal Ca2+ (106 ± 27 fF for ubMunc13-2–EGFP; 85 ± 16 fF for ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP; 74 ± 11 fF for control cells). ubMunc13-2, which is able to bind CaM, but not ubMunc13-2W387R shows enhanced secretion mainly in the second phase, 0.1–2 ms, during the flash stimulation (1160 ± 180 fF for ubMunc13-2–EGFP; 330 ± 40 fF for ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP; 90 ± 10 fF for control cells). The sustained component (2–5 s) in both ubMunc13-2- and ubMunc13-2W387R-overexpressing cells is larger than in the control (ubMunc13-2–EGFP; 364 ± 66.2 fF, ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP; 216 ± 36.2 fF, control; 86.7 ± 16.3 fF). Results represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.0001.

Because simple exponential fittings could not describe the exocytosis kinetics in ubMunc13-2–EGFP-expressing cells under the low-priming conditions, we quantified secretion by dividing the release curves into three phases: the burst phase (up to 100 ms), an intermediate phase (100 ms to 2 s) representing the S-shaped phase, and the sustained phase (2–5 s) (Fig. 4B). The secretion amplitudes measured during the first 100 ms were similar for the three cell types (Fig. 4B). Although ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells showed an ∼30% larger initial burst component than control cells, it was significantly smaller than the initial release in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells under higher basal Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 2B; 700 fF). The small initial amplitude in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells indicated that no significant priming of vesicles to the RRP occurs at low basal Ca2+ concentrations (low-priming conditions), even in the presence of ubMunc13-2–EGFP. Thus, it appears that Ca2+ is needed for the priming activity of ubMunc13-2. The second release phase in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells was seven times larger than in control cells and approximately three times larger than in ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells (Fig. 4C). This enhanced secretion represents the action of a Ca2+/CaM/ubMunc13-2-dependent vesicle-recruitment process in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells during the pulse. The subsequent sustained phases were larger in ubMunc13-2–EGFP and ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP cells compared with the sustained component in control cells (Fig. 4C).

The delayed, S-shaped secretion phase in cells overexpressing ubMunc13-2–EGFP at low basal [Ca2+]i differed from the typical two-component secretion time course seen in chromaffin cells at high basal [Ca2+]i during photolysis of caged Ca2+. Nevertheless, the rate of secretion in this phase decayed exponentially with a time constant of 600–700 ms, which is similar to the slow time constant of the SRP in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells under high [Ca2+]i (priming) conditions (Fig. 2). We verified that this secretory component represents fusion of catecholamine-containing granules and not nonspecific membrane fusion (Xu et al., 1998) using amperometry and found a good correlation between the delayed increase in capacitance curves and the delayed increase in amperometric activity (supplemental Fig. S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

We assume that, under low [Ca2+]i (priming) conditions, the small pool of primed vesicles in ubMunc13-2–EGFP cells contributes to the small burst and that this pool is depleted during the initial 100 ms of the stimulation. Thus, the delayed secretory phase represents the fusion of vesicles that were recruited and matured into the fusion-ready state during the stimulation. As we later deduced from a detailed simulation (see below), the kinetics of this phase provides a very good estimate of the time required for vesicle recruitment and priming by ubMunc13-2 during stimulation, i.e., the time course of vesicle maturation. The lack of such a delayed S-shaped secretion in cells expressing ubMunc13-2W387R–EGFP demonstrates the important role of Ca2+/CaM in modulating ubMunc13-2 activity and indicates that Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 enhances vesicle recruitment during the stimulation.

Kinetics analysis of the priming mechanism

We next examined at which stage the CaM–ubMunc13-2 complex operates in the sequence of events leading to exocytosis. Because ubMunc13-2 causes an apparent change in the kinetics of the SRP and has an S-shaped time course that cannot be fitted with the three-exponential fitting procedure, we decided to analyze the nature of these changes using a detailed kinetics analysis based on a previously published protein–protein interaction simulation (Mezer et al., 2004, 2006). We implemented a set of new reactions in the model that represent the binding of Ca2+/CaM to ubMunc13-2, performed a detailed kinetics search, and reconstructed the experimental data (Fig. 5) using the genetic algorithm technique (Mezer et al., 2006).

The original mechanistic model contained an original priming reaction, marked as reaction 0, in which a protein suspected to be Munc13-1 is activated by Ca2+ ions, and later on, Munc13-1 activates the SNARE complex. We expanded this step into a set of three reactions representing the sequential activation of ubMunc13-2 by Ca2+/CaM (Scheme I, Fig. 6, reactions 0′-1 to 0′-3). The first step (0′-1) represents the Ca2+-dependent formation of the ubMunc13-2/CaM/Ca2+ complex. The next steps (0′-2 and 0′-3) are the binding of additional Ca2+ ions to the complex that were needed for the fitting of the signals (for more details, supplemental Results, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and the subsequent activation of SNARE complexes by the ubMunc13-2/CaM/Ca2+ complex (reaction 3a). Nevertheless, we kept a second, parallel pathway for the Ca2+-activated priming reaction by a priming factor that we named PFA (Fig. 6, reaction 0). Under these conditions, PFA is active in all cells, whereas in cells overexpressing ubMunc13-2, the parallel priming system consisting of the ubMunc13-2/CaM pathway is also activated. Because we found that ubMunc13-2 is expressed in bovine chromaffin cells (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), it might also be active in control cells. However, because the expression level of ubMunc13-2 is low in control cells (supplemental Fig. S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and the kinetics of fusion are significantly different from those seen after ubMunc13-2 overexpression (Figs. 2, 4), we assume that endogenous ubMunc13-2 in bovine chromaffin cells does not dominate the priming reaction. Both ubMunc13-2 and PFA are activated by Ca2+ and participate in the same secretion mechanism, converting the SNARE complexes into active SNARE complexes (SNARE′: reactions 3a and 3b in Fig. 6, respectively) and thus increasing the number of primed vesicles.

|

The secretion curves for control cells (Fig. 5A) were accurately reconstructed by the model using the very same set of previously published parameters without any readjustments (Mezer et al., 2004, 2006). The reconstruction of the fusion dynamics recorded for the ubMunc13-2 cells and the ubMunc13-2W387R cells was also very accurate (Fig. 5B) for all experimental conditions. The rate constants and parameters used for the simulation are given in Table 2. A major advantage of the mechanistic model is that the reconstruction of the experiments is accompanied by a careful evaluation of the results according to the dynamics of the new reactions and their rate constants. A mechanistic clarification of the results is given below.

Evaluation of the priming mechanism

To better understand the ubMunc13-2 pathway, we subtracted the contribution of the control cells from the total signals of the overexpressing cells (Fig. 5C). This provided a good approximation of the net contribution of ubMunc13-2 and ubMunc13-2W387R to the measured signals and significantly improved our interpretation of the maturation of protein complexes in the ubMunc13-2 pathway. Under low priming conditions, practically no vesicles matured via the ubMunc13-2 pathway compared with control cells (Fig. 5Ciii), so once the Ca2+ pulse is given (arrow in Fig. 5C), there is no burst at all. Thereafter, after a short delay, the reaction exhibits an S-shaped phase, lasting ∼1–2 s, during which the ubMunc13-2 pathway reacts to the added Ca2+ ions, and the vesicles mature and fuse with the plasma membrane.

We next addressed two main questions: (1) what causes the slower, delayed secretion in ubMunc13-2 cells under low priming conditions? and (2) what prevents secretion in these cells (Fig. 5Ciii) from reaching the higher level seen in ubMunc13-2 cells that undergo priming (Fig. 5Ci)?

(1) Analysis of the dynamics of the intermediate protein complexes of the model during the Ca2+ pulse indicated that the rate-limiting step is the binding of synaptotagmin to the SNARE–complexin complex (Fig. 6, steps 6 and 11) or, as recently suggested, the replacement of complexin by synaptotagmin (Tang et al., 2006; see also Giraudo et al., 2006). This slows down the maturation of SNARE′ into a fully functional complex with synaptotagmin (SNARE#) and causes the delayed S-shaped secretion in “unprimed” ubMunc13-2 cells and the slow and sustained secretion in “primed” ubMunc13-2 cells (supplemental Fig. S3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Thus, because the inherent process of vesicle maturation is rather slow, there is a continuous but slow supply of new primed vesicles for fusion during the Ca2+ stimulation, i.e., vesicle recruitment. This slow secretion overrides the SRP component and extends into the sustained component. This slow phase in ubMunc13-2 cells under priming conditions reflects the maturation/recruitment of vesicles through the exocytosis cascade and does not represent slow fusion of vesicles from the SRP (or RCII). Therefore, the mechanistic model provides a molecular explanation for the different kinetics components of the secretion. In addition, the analysis provides a first estimation of the rate of vesicle recruitment and priming in chromaffin cells at high Ca2+ levels.

(2) We further investigated the mechanisms that might explain why the total secretion in the unprimed ubMunc13-2 cells (Fig. 5Ciii) is smaller than that in primed ubMunc13-2 cells (Fig. 5Ci). Analysis of the intermediate complexes in the ubMunc13-2 pathway and examination of the rate constants of the different reactions revealed that the lower amplitude is attributable to the slow reaction between ubMunc13-2, CaM, and Ca2+ (reaction 0′-1 in Scheme I). This reaction is at least one order of magnitude slower than the duration of the Ca2+ pulse (Table 2). Therefore, during the 5 s stimulation, only a small fraction of ubMunc13-2 cells mature and bypass this step, and the contribution of ubMunc13-2 to fusion under these conditions is limited. At high basal Ca2+ levels (400 nm for 30 s, i.e., the priming period), the system proceeds beyond this step, and the number of primed complexes is increased. Thus, this step represents a Ca2+- and time-dependent “priming switch.”

Indirect support for our model came from an unexpected direction. When we simulated the Ca2+-dependent binding of ubMunc13-2 to the CaM beads (Fig. 1C) using the parameters obtained by the genetic algorithm for the above model, we obtained a relatively good fit to the concentration–response curve (Fig. 1C, white circles). Therefore, the same rate constants that were sought and adjusted to fit the dynamic electrophysiological measurements can also reconstruct the biochemical interaction of ubMunc13-2 with CaM and Ca2+.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the involvement of ubMunc13-2 in vesicle priming and recruitment in chromaffin cells and investigated the effects of Ca2+ and CaM on these processes. We found that ubMunc13-2 enhances exocytosis and acts as a priming factor for chromaffin granules and that CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 specifically enhances vesicle recruitment during ongoing stimulation. Interestingly, we found that the priming of vesicles by ubMunc13-2 into the RRP depends on Ca2+ but is independent of CaM binding to ubMunc13-2. This CaM-independent effect of calcium might be mediated via several other putative Ca2+-binding domains of Munc13, including the C2B domain (Basu et al., 2007). The low-priming protocol provided information about the kinetics of vesicle priming and indicated that, after a small burst in ubMunc13-2 cells, secretion is delayed. This 200 to 300 ms delay might reflect the onset of priming, and the time constant of the S-shaped secretory phase (700 ms) corresponds to the time course of vesicle recruitment under high Ca2+ conditions. Interpreting these results in the framework of a mechanistic model that describes the exocytotic process as a sequence of protein–protein interactions revealed that the slow exocytotic phase represents the kinetics of vesicle maturation and recruitment under high Ca2+. The main finding of our study is that there are two steps to the activation of Munc13 by calcium, a slow and high-affinity step that controls the priming and a faster step that controls recruitment during the pulse. The first, slow step (0′-1) acts as a Ca2+- and time-dependent priming switch.

Chromaffin cells have been used extensively as a model for neurosecretion, and the molecular machinery of exocytosis in these cells is similar to that in neurons (Burgoyne and Morgan, 1995, 2003; Neher, 2006). Our data indicate that vesicle recruitment in chromaffin cells depends on Ca2+/CaM binding to ubMunc13-2, similar to vesicle pool refilling in neurons (Junge et al., 2004). In addition, the size of the RRP in chromaffin cells and the amplitude of the EPSC in neurons both depend on ubMunc13-2 but are independent of CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 (Junge et al., 2004). Thus, in both systems, the resting RRP size depends on ubMunc13-2, but is less affected by CaM binding to ubMunc13-2.

Activity-dependent regulation of RRP refilling or synaptic augmentation also depends on Ca2+ (Dittman and Regehr, 1998; Stevens and Wesseling, 1998; Wang and Kaczmarek, 1998; Junge et al., 2004). Although many synaptic proteins can be modulated by Ca2+, the precise molecular mechanism of vesicle pool refilling and replenishment is not known. In the calyx of Held, this process has been found to be CaM dependent (Sakaba and Neher, 2001). In hippocampal neurons, RRP refilling depends on CaM binding of Munc13s, which boosts the activity of the latter and enhances vesicle recruitment and refilling (Junge et al., 2004). Here, we demonstrate that CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 is necessary for vesicle recruitment during stimulation in chromaffin cells. In addition, the similar onset of the augmentation seen in hippocampal neurons (100 ms) (Junge et al., 2004) and the delayed, S-shaped release phase in chromaffin cells indicate that vesicle recruitment by the ubMunc13-2–CaM complex in chromaffin cells occurs on the same timescale as augmentation in neurons. Thus, although a clear and direct comparison between the secretable vesicle pools in chromaffin cells and neurons may be problematic (Neher, 2006), our data show a good correlation between the CaM- and ubMunc13-2-dependent RRP size in chromaffin cells and the EPSC/pool sizes in neurons, and between vesicle recruitment and augmentation, respectively, in these two cell types.

One possible mode of action for Munc13 is its binding to syntaxin, which may keep syntaxin in a conformation that facilitates SNARE-complex formation (Richmond et al., 2001). Interfering with this interaction abolishes the priming activity of Munc13 (Basu et al., 2005; Madison et al., 2005; Stevens et al., 2005). An interesting finding that emerges from our simulation is that the binding of the Munc13–CaM complex to SNARE (reaction 3a) is exceptionally fast (Table 2). This reaction rate is even faster than the maximal rate of a diffusion-controlled reaction. Such a high rate can only fit reactions between proteins that are already connected to each other. Accordingly, we suggest that ubMunc13-2 may already be tightly coupled to syntaxin or to syntaxin in the SNARE complex under resting conditions. This conclusion agrees with the biochemical result of an upstream interaction between Munc13s and syntaxin (Betz et al., 1997). This tight binding might ensure that the activation of ubMunc13-2 by Ca2+, either directly (Basu et al., 2007) or through CaM, will rapidly transduce its effect to syntaxin and the fusion machinery. Munc13 has been suggested to be present in two pools: a cytosolic pool and a membrane-associated pool, which may be anchored through RIM, the cytoskeleton, or syntaxin (Rhee et al., 2002). Based on our model, we suggest that the membrane-associated pool of ubMunc13-2 is tightly coupled to syntaxin. The enhancement via Ca2+/CaM might increase the interaction with syntaxin or recruit more Munc13 from the cytosolic pool.

Electrophysiological measurements from endocrine cells led to the identification of distinct pools of vesicles that represent different stages of vesicle maturation along the secretory pathway (Rettig and Neher, 2002; Richmond and Broadie, 2002; Becherer and Rettig, 2006). A direct equilibrium between several vesicular pools has been suggested to control the kinetics of fusion (Heinemann et al., 1993; Neher, 1998; Voets et al., 1999; Rettig and Neher, 2002). Although this latter macroscopic model is rather simple and suitable for fitting experimental data, the parameters derived by the analysis cannot be readily interpreted in terms of biochemical events representing the molecular mechanism of the maturation–release process. Recently, we have expanded this classical view and simulated exocytotic reactions via a mechanism based on a detailed description of the maturation reactions, in which the rate constants are directly associated with intermolecular reactions between defined proteins (Mezer et al., 2004, 2006). Although this presentation is less intuitive and the reconstruction of the experimental data more laborious, it yields precise, detailed mechanistic parameters characterizing the individual steps of the fusion process. The results of the present study were subjected to kinetics analysis using above mentioned exocytotic models. The analysis using the macroscopic model (i.e., triple-exponential fitting) implied that the rate of vesicle fusion from the SRP in ubMunc13-2 cells is significantly altered by the overexpression of ubMunc13-2. Analysis with the mechanistic model (Mezer et al., 2004) revealed that the maturation of activated SNARE complexes, up until the synaptotagmin–Ca2+-binding steps, is rather slow. This produces an apparent slow release in ubMunc13-2 cells (that overrides the SRP and extends into the sustained component in these cells) and the delayed, S-shaped-like secretion phase under low-priming conditions in ubMunc13-2 cells. Thus, the mechanistic model demonstrates a link between molecular interactions and the kinetics of fusion, and, accordingly, we propose that the slow phase in ubMunc13-2 cells reflects the maturation of vesicles through the exocytosis cascade and not slow fusion of vesicles from the SRP. The results and analysis provide a precise description of the time course of a major priming pathway of the release system in chromaffin cells. It is worth noting that the priming reaction does not occur in a single step: it involves a complex cascade of interactions among various proteins and second messengers such as CaM and Ca2+. Therefore, as soon as more information about the effect of the manipulation of other proteins becomes available, a much clearer picture of this important process will emerge.

The model search revealed an interesting priming/recruitment mechanism consisting of two types of Ca2+-sensor steps: a high-affinity step that responds rather slowly to the presence of Ca2+ ions (step 0′-1) and that corresponds with priming, and low-Ca2+-affinity steps (0′-2 and 0′-3), which facilitate ubMunc13-2 maturation during the high Ca2+ pulse and enable efficient vesicle maturation and recruitment. The combination of these two features allows the system to maintain a stable basal level of primed vesicles under moderate priming conditions (300–400 nm Ca2+) and to recruit more vesicles during the Ca2+-pulse phases (10 μm). We suggest that the high-affinity slow step (0′-1) acts as a “priming switch.” Under low [Ca2+], hardly any vesicles undergo maturation and the number of primed vesicles is low. During longer priming periods (several tens of seconds), the number of primed vesicles that mature and pass through this slow step increases, and, consequently, secretion during the burst will be larger. Thus, this reaction determines how much secretion will occur based on previous exposure to Ca2+. Interestingly, using this slow reaction, the model can “remember” and “react to” the [Ca2+] that it was “exposed to” before the major Ca2+ pulse. A similar mechanism may exist in cells, enabling a conditional response that depends on previous [Ca2+] levels, a process that might be similar to those occurring during short-term plasticity (Zucker and Regehr, 2002), although additional experiments are needed to demonstrate a direct link to plasticity. Another advantage of a slow Ca2+-priming switch might be the prevention of the effects of short [Ca2+]i fluctuations on the priming level, a characteristic that could increase the robustness of secretory-system responses.

In summary, we used the chromaffin cell as a tool to study discrete functional elements of the exocytotic reaction, namely vesicle priming and recruitment mediated by ubMunc13-2 and Ca2+/CaM. Our data indicate that CaM binding to ubMunc13-2 is not necessary for priming into the RRP but that the Ca2+/CaM interaction enhances vesicle recruitment and exocytosis during the stimulation. The slow ubMunc13-2 calcium-dependent priming switch and the fast ubMunc13-2, Ca2+/CaM recruitment steps can account for the robustness of synaptic transmission and plasticity.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Israel Science Foundation Grants 424/02-16.6 and 1211/07 (U.A.), the Yeshaya Horowitz Association through the Center for Complexity Science (U.A., M.G., M.A.), and German Research Foundation Grant SFB406/A1 (N.B.). We thank members of our laboratories for fruitful discussions and comments on this manuscript and Ana Vitkin for assistance with the CaM-binding experiment.

References

- Aravamudan B, Fergestad T, Davis WS, Rodesch CK, Broadie K. Drosophila UNC-13 is essential for synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:965–971. doi: 10.1038/14764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashery U, Betz A, Xu T, Brose N, Rettig J. An efficient method for infection of adrenal chromaffin cells using the Semliki Forest virus gene expression system. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:525–532. doi: 10.1016/s0171-9335(99)80017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashery U, Varoqueaux F, Voets T, Betz A, Thakur P, Koch H, Neher E, Brose N, Rettig J. Munc13–1 acts as a priming factor for large dense-core vesicles in bovine chromaffin cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:3586–3596. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin I, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC, Brose N. Munc13–1 is essential for fusion competence of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1999;400:457–461. doi: 10.1038/22768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu J, Shen N, Dulubova I, Lu J, Guan R, Guryev O, Grishin NV, Rosenmund C, Rizo J. A minimal domain responsible for Munc13 activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1017–1018. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu J, Betz A, Brose N, Rosenmund C. Munc13–1 C1 domain activation lowers the energy barrier for synaptic vesicle fusion. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1200–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4908-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becherer U, Rettig J. Vesicle pools, docking, priming, and release. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:393–407. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0243-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Okamoto M, Benseler F, Brose N. Direct interaction of the rat unc-13 homologue Munc13–1 with the N terminus of syntaxin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2520–2526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Sudhof TC, Rettig J, Brose N. Munc13–1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;21:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner MA, Holz RW. Kinetic analysis of secretion from permeabilized adrenal chromaffin cells reveals distinct components. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16219–16225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Hofmann K, Hata Y, Sudhof TC. Mammalian homologues of Caenorhabditis elegans unc-13 gene define novel family of C2-domain proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25273–25280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Rosenmund C, Rettig J. Regulation of transmitter release by Unc-13 and its homologues. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Ca2+ and secretory-vesicle dynamics. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93900-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Common mechanisms for regulated exocytosis in the chromaffin cell and the synapse. Seminars Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:141–149. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1996.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Secretory granule exocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:581–632. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Schoch S, Schmitz F, Sudhof TC, Malenka RC. RIM1alpha is required for presynaptic long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;415:327–330. doi: 10.1038/415327a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain LH, Roth D, Morgan A, Burgoyne RD. Distinct effects of α-SNAP, 14-3-3 proteins, and calmodulin on priming and triggering of regulated exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1063–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SA, Smith C. Physiological stimuli evoke two forms of endocytosis in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;537:871–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YA, Duvvuri V, Schulman H, Scheller RH. Calmodulin and protein kinase C increase Ca2+-stimulated secretion by modulating membrane-attached exocytic machinery. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26469–26476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova K, Kawabe H, Betz A, Brose N, Jahn O. Characterization of the Munc13-calmodulin interaction by photoaffinity labeling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1256–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Calcium dependence and recovery kinetics of presynaptic depression at the climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6147–6162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engisch KL, Chernevskaya NI, Nowycky MC. Short-term changes in the Ca2+-exocytosis relationship during repetitive pulse protocols in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9010–9925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09010.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasshauer D, Eliason WK, Brunger AT, Jahn R. Identification of a minimal core of the synaptic SNARE complex sufficient for reversible assembly and disassembly. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10354–10362. doi: 10.1021/bi980542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergestad T, Wu MN, Schulze KL, Lloyd TE, Bellen HJ, Broadie K. Targeted mutations in the syntaxin H3 domain specifically disrupt SNARE complex function in synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9142–9150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09142.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo CG, Eng WS, Melia TJ, Rothman JE. A clamping mechanism involved in SNARE-dependent exocytosis. Science. 2006;313:676–680. doi: 10.1126/science.1129450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis A, Burrone J, Lagnado L. Two actions of calcium regulate the supply of releasable vesicles at the ribbon synapse of retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6309–6317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06309.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman M, Nachliel E. Time resolved dynamics of proton transfer in proteinous systems. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:329–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Heuser JE, Jahn R. Neurotransmitter release: four years of SNARE complexes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann C, von Ruden L, Chow RH, Neher E. A two-step model of secretion control in neuroendocrine cells. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00374600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck CR, Joines JA, Kay MG. Raleigh, NC: NCSU-IE TR; 1995. Genetic algorithm for function optimization: a Matlab implementation; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs-engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge HJ, Rhee JS, Jahn O, Varoqueaux F, Spiess J, Waxham MN, Rosenmund C, Brose N. Calmodulin and Munc13 form a Ca2+ sensor/effector complex that controls short-term synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2004;118:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. J Physiol (Lond) 1968;195:481–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick C, Renden R, von Gersdorff H. Physiological temperatures reduce the rate of vesicle pool depletion and short-term depression via an acceleration of vesicle recruitment. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1366–1377. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G. RIM1: an edge for presynaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G, Sudhof TC. Assembly of snare core complexes occurs prior to neurotransmitter release to set the readily-releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27703–27707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison JM, Nurrish S, Kaplan JM. UNC-13 interaction with syntaxin is required for synaptic transmission. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2236–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen JM, Madison JM, Dybbs M, Kaplan JM. Antagonistic regulation of synaptic vesicle priming by tomosyn and UNC-13. Neuron. 2006;51:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezer A, Nachliel E, Gutman M, Ashery U. A new platform to study the molecular mechanisms of exocytosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8838–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2815-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezer A, Ashery U, Gutman M, Project E, Bosis E, Fibich G, Nachliel E. Systematic search for the rate constants that control the exocytotic process from chromaffin cells by a genetic algorithm. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. A comparison between exocytic control mechanisms in adrenal chromaffin cells and a glutamatergic synapse. Pflügers Arch. 2006;453:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nili U, de Wit H, Gulyas-Kovacs A, Toonen RF, Sorensen JB, Verhage M, Ashery U. Munc18–1 phosphorylation by protein kinase C potentiates vesicle pool replenishment in bovine chromaffin cells. Neuroscience. 2006;143:487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig J, Neher E. Emerging roles of presynaptic proteins in Ca++-triggered exocytosis. Science. 2002;298:781–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1075375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Betz A, Pyott S, Reim K, Varoqueaux F, Augustin I, Hesse D, Sudhof TC, Takahashi M, Rosenmund C, Brose N. Beta phorbol ester- and diacylglycerol-induced augmentation of transmitter release is mediated by Munc13s and not by PKCs. Cell. 2002;108:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J, Broadie K. The synaptic vesicle cycle: exocytosis and endocytosis in Drosophila and C. elegans. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:499–507. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Davis WS, Jorgensen EM. UNC-13 is required for synaptic vesicle fusion in C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:959–964. doi: 10.1038/14755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Weimer RM, Jorgensen EM. An open form of syntaxin bypasses the requirement for UNC-13 in vesicle priming. Nature. 2001;412:338–341. doi: 10.1038/35085583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Sigler A, Augustin I, Reim K, Brose N, Rhee JS. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron. 2002;33:411–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T. Roles of the fast-releasing and the slowly releasing vesicles in synaptic transmission at the calyx of held. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5863–5871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Calmodulin mediates rapid recruitment of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2001;32:1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seward EP, Nowycky MC. Kinetics of stimulus-coupled secretion in dialyzed bovine chromaffin cells in response to trains of depolarizing pulses. J Neurosci. 1996;16:553–562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Moser T, Xu T, Neher E. Cytosolic Ca2+ acts by two separate pathways to modulate the supply of release-competent vesicles in chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1998;20:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wesseling JF. Activity-dependent modulation of the rate at which synaptic vesicles become available to undergo exocytosis. Neuron. 1998;21:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]