Abstract

The independent effects of different brain pathologies on age-dependent cognitive decline are unclear. We examined this in 300 cognitively unimpaired elderly individuals from the BioFINDER study. Using cognition as outcome we studied the effects of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for amyloid-β (Aβ42/40), neuroinflammation (YKL-40), and neurodegeneration and tau pathology (T-tau and P-tau) as well as MRI measures of white-matter lesions, hippocampal volume (HV), and regional cortical thickness. We found that Aβ positivity and HV were independently associated with memory. Results differed depending on age, with memory being associated with HV (but not Aβ) in older participants (73.3–88.4 years), and with Aβ (but not HV) in relatively younger participants (65.2–73.2 years). This indicates that Aβ and atrophy are independent contributors to memory variability in cognitively healthy elderly and that Aβ mainly affects memory in younger elderly individuals. With advancing age, the effect of brain atrophy overshadows the effect of Aβ on memory function.

Subject terms: Cognitive ageing, Alzheimer's disease, Hippocampus

Introduction

The prevailing hypothesis of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggests β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition in the brain as the primary event followed by tau pathology, neuronal dysfunction, neurodegeneration, and cognitive symptoms1. To understand the pathophysiology of AD and to improve design of clinical trials, more information is needed about the sequential order of and associations between AD biomarkers, and their relationship with other age-associated brain changes. It is especially important to clarify the roles of different biomarkers in early stages of AD, since trials of disease-modifying drugs in late stages of AD have failed and focus is now shifting towards targeting the disease early, even before symptoms develop.

Aβ pathology, detected by amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ peptides, is common in cognitively unimpaired elderly2–5. A person with Aβ pathology can be said to be on the Alzheimer continuum6, and the asymptomatic presence of Aβ pathology in cognitively unimpaired persons may be called preclinical AD7. The direct effects of Aβ pathology on cognitive performance in the preclinical stages are not fully understood, with some studies showing an association between Aβ pathology and worse memory performance cross-sectionally8–12 and others not13–18. However, recent studies conclude that Aβ negative cognitively unimpaired subjects perform better on tests of overall cognition, as well as tests of memory function, compared to Aβ positive, and, more notably, Aβ positive cognitively unimpaired show a faster cognitive decline over time19–21.

Besides Aβ pathology, other AD-related brain changes have also been associated with cognitive decline. Post-mortem studies have shown that the degree of cognitive impairment is closely related to the amount of neurofibrillary tangles, consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau (P-tau), in patients with AD dementia22. Associations have been shown in cognitively unimpaired persons between memory performance and CSF levels of total tau (T-tau) and P-tau17, and longitudinal studies have shown a relationship between CSF tau and change in performance of episodic memory23,24.

Some degree of neuroinflammation is also seen in AD, with glial cells surrounding amyloid plaques25. Levels of YKL-40, a marker of glial activation, are elevated in AD patients compared to controls26 as well as in prodromal AD compared to controls27. Cerebrovascular disease is also an important cause of cognitive decline, and is often seen as comorbidity in people with AD28.

Atrophy of specific structures of the brain is linked to poorer memory function, with both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies showing an association between hippocampal volume (HV) and memory function in cognitively unimpaired subjects29–32. Apart from the hippocampus, neurodegeneration of certain cortical areas, including medial temporal but also lateral temporal, parietal, and frontal structures, has been linked to AD33,34. Atrophy of these specific regions can predict progression to AD dementia in cognitively unimpaired persons35. Neurodegeneration appears to in part mediate the effect of Aβ on cognition9,16,36,37, but Aβ pathology and HV38 or cortical thickness measures10 may also independently affect memory performance in cognitively unimpaired elderly.

It is possible that the effects of different pathological processes and structural changes on cognition are statistically moderated by age. For example, Gorbach et al. showed that hippocampal atrophy is associated with worsening memory in people aged 65–80 but not 55–6039. Also Kaup et al. could show that the association between brain structure and cognition is stronger in older than younger individuals40.

The objectives of this study was to (1) investigate the associations between memory performance as well as attention/executive function and biomarkers of amyloid pathology, tau pathology, inflammation, cerebrovascular pathology, and regional atrophy in cognitively unimpaired elderly, and (2) test to what extent these associations are statistically moderated by age, with the hypothesis (based on above mentioned studies) that the association between HV and memory is moderated by age.

Material and Methods

Participants

This was a cross-sectional study using an existing cohort of cognitively unimpaired people from the Swedish BioFINDER study. Details of the study, including inclusion criteria are described at http://www.biofinder.se. In short, participants from an existing longitudinal population-based community cohort study were recruited. The participants had to be over 65 years of age (a cut-off often used in the field, since it is the age discriminating between early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease), without subjective memory complaints, without history of severe neurological or psychiatric disorder, have Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 28 (out of 30) or higher, and not fulfil criteria of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Lund University Research Ethics Committee approved the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

CSF

Lumbar CSF samples were stored in −80 °C pending analyses. Levels of Aβ42, Aβ40, T-tau, and P-tau were measured using the Elecsys fully automated immunoassay, as described previously41. We used the Aβ42/40 ratio as a proxy for brain Aβ deposition42. Levels of YKL-40 were measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as described previously27.

Imaging

The participants underwent MRI brain scanning at 3 Tesla using a standardized protocol of sequences. The volume of white matter lesions (WML; seen as hyperintensities in T2 weighted scans) was measured using the Lesion Segmentation Tool (https://www.applied-statistics.de/lst.html). Automatic segmentation using FreeSurfer software version 5.1 (http://www.freesurfer.net) was performed to measure total intracranial volume (ICV), HV, and regional cortical thickness. The sum of left and right HV was used, but analyses were also performed with left and right HV respectively to look for laterality effects. For cortical thickness, division into frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes was done using the standard FreeSurfer parcellation43. Additionally, entorhinal and parahippocampal cortices were combined in one meta-region, chosen for its association with memory function44. Thickness measures from both hemispheres were combined and adjusted for surface area.

Cognition

The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) 10-word delayed recall45 was used as a measure of memory performance. The number of correct answers was used. The Trailmaking Test A (TMT-A)46, Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)47, and A Quick Test for Cognitive Speed (AQT)48 were used to form a composite measure of attention and executive function. The raw scores were converted into z scores based on the distribution in the current population, and, if applicable, inverted so that a higher value represented better attention/executive function. The composite was the mean of these z scores.

Statistics

A cut-off for Aβ positivity was defined using mixture modelling in a larger sample of the BioFINDER study (n = 889 in total) consisting of a group of cognitively unimpaired subjects, including the sample included in this study and an additional 25 subjects (n = 325), as well as a group of subjects with subjective cognitive decline (SCD; n = 204), MCI (n = 276), or dementia (n = 84), using the R package “mixtools”. Mixture modelling is a 2-step procedure based on an expectation maximization algorithm, which assumes that the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio is a mixed sample from two different normal distributions (in this case one with a normal Aβ deposition and one with an abnormal Aβ deposition). Mixture modelling has previously successfully been used to identify cut-offs for Aβ biomarkers49,50.

To compare differences between groups, the chi-square test was used for dichotomous variables and the independent samples t-test for numerical variables. Linear regression models were tested to assess the effects of different biomarkers on cognition, with and without covariates (age, sex, and years of education, and HV was also adjusted for ICV). Interaction terms were tested for biomarkers and age. To facilitate interpretation of interactions and main effects, we used z scores of continuous variables. Test of statistical mediation was performed using the causal steps approach51. WML volume was used after logarithmic transformation (ln), because of skewed distribution. Statistical significance was defined by p < 0.05. Correction for multiple comparisons was performed by the false discovery rate when indicated. Statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.3) and SPSS Statistics for Mac (version 24).

Results

Out of the 361 participants of the cohort of cognitively unimpaired in the Swedish BioFINDER Study, 300 had complete baseline MRI and CSF analyses and were included in the present study. Demographics are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 shows a histogram of the age distribution in the sample. The cut-off for Aβ positivity was defined as Aβ42/40 < 0.051 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The proportion of amyloid positive subjects in each group used for mixture modelling is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics. Descriptive characteristics in the total population and split into two age groups by the median age (73.3 years). Mean (SD) if not otherwise specified. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ40, amyloid-β 40; Aβ42, amyloid-β 42; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WML, white matter lesion; ctx, cortex; ADAS, Alzheimer's disease assessment scale; AQT, A quick test of cognitive speed; SDMT, symbol digit modalities test; TMT-A, trailmaking test A.

| All (n = 300) | Younger (n = 150) | Older (n = 150) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 73.8 (5.0) | 69.7 (2.1) | 77.9 (3.5)*** |

| Sex (% female) | 59.7 | 52.0 | 67.3** |

| Education (years) | 12.3 (3.7) | 13.1 (3.8) | 11.5 (3.5)*** |

| APOE ε4 allele carrier (%; n = 297) | 27.9 | 28.4 | 27.5 (ns) |

| CSF Measures | |||

| Aβ40 (pg/l) | 18 418 (5 638) | 17 602 (5 283) | 19 234 (5 877)* |

| Aβ42 (pg/l) | 1 429 (648) | 1 379 (626) | 1 478 (667; ns) |

| Aβ42/40 | 0.081 (0.064) | 0.078 (0.023) | 0.084 (0.087; ns) |

| Aβ status (% positive) | 18.0 | 13.3 | 22.7* |

| P-tau (ng/l) | 20.1 (7.85) | 18.2 (6.6) | 22.0 (8.5)*** |

| T-tau (ng/l) | 234 (84.1) | 213 (71.1) | 255 (90.8)*** |

| YKL-40 (ng/l; n = 299) | 196 053 (67 789) | 180 181 (64 993) | 212 032 (66 992)*** |

| MRI Measures | |||

| WML volume (cm3) | 10.6 (13.7) | 7.43 (11.1) | 13.8 (15.2)*** |

| Total intracranial volume (cm3) | 1 557 (158) | 1 582 (150) | 1 531 (162)** |

| Hippocampal volume (cm3) | 7.37 (1.02) | 7.77 (0.94) | 6.96 (0.93)*** |

| Entorhinal/parahippocampal ctx (mm) | 2.64 (0.33) | 2.76 (0.27) | 2.53 (0.34)*** |

| Temporal ctx (mm) | 2.48 (0.21) | 2.56 (0.17) | 2.41 (0.23)*** |

| Frontal ctx (mm) | 2.24 (0.19) | 2.29 (0.16) | 2.19 (0.20)*** |

| Parietal ctx (mm) | 2.06 (0.15) | 2.09 (0.13) | 2.02 (0.16)*** |

| Occipital ctx (mm) | 1.86 (0.11) | 1.88 (0.10) | 1.84 (0.11)** |

| Cognitive Measures | |||

| ADAS Cog delayed recall (correct answers) | 8.0 (2.0) | 8.3 (1.5) | 7.6 (2.2)** |

| AQT (seconds; n = 299) | 66.4 (13.0) | 64.1 (12.1) | 68.7 (13.4)** |

| SDMT (correct answers; n = 298) | 36.8 (8.43) | 39.9 (8.04) | 33.6 (7.58)*** |

| TMT A (seconds) | 46.2 (16.9) | 41.5 (13.8) | 51.0 (18.3)*** |

Associations between biomarkers and memory

In univariable analyses, Aβ positivity (β = −0.15; p = 0.009), higher P-tau (β = −0.15; p = 0.012), higher T-tau (β = −0.13; p = 0.021), and higher YKL-40 (β = −0.13; p = 0.026) were associated with worse memory performance. When controlling for age, sex, and education, only Aβ positivity (β = −0.14; p = 0.013) remained significantly associated with memory (Table 2). Larger WML volume (β = −0.14 (p = 0.020), smaller total HV (β = 0.21; p < 0.001), and thinner cortex of all regions studied (β 0.13–0.28; p 0.001–0.030) were associated with worse memory, in the unadjusted analyses. When controlling for age, sex, and education (and for HV also ICV), smaller HV (β = 0.27; p < 0.001) and thinner entorhinal/parahippocampal (β = 0.22; p < 0.001), temporal (β = 0.16; p = 0.012), and frontal (β = 0.14; p = 0.022) cortical thickness were associated with worse memory (Table 2). The results did not differ if total HV was replaced with left (β = 0.25; p < 0.001) or right HV (β = 0.24; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Associations between CSF/MRI measures and cognition. Linear regression models with cognitive measures as dependent variables and CSF/MRI measures as independent variables. Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: controlling for age, sex, and education, and for hippocampal volume also total intracranial volume. Standardized beta coefficients with p values (unadjusted and false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted in parentheses) are presented. Abbreviations: ADAS, Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ, amyloid-β; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WML, white matter lesion; ctx, cortex.

| ADAS Cog delayed recall | Attention/executive composite score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| CSF MEASURES | ||||||||

| Aβ positivity | −0.15 | 0.009 | −0.14 | 0.013 (0.062) | −0.051 | 0.38 | −0.020 | 0.70 (0.81) |

| P-tau | −0.15 | 0.012 | −0.11 | 0.061 (0.19) | −0.13 | 0.027 | −0.023 | 0.67 (0.81) |

| T-tau | −0.13 | 0.021 | −0.097 | 0.099 (0.24) | −0.14 | 0.018 | −0.025 | 0.64 (0.81) |

| YKL-40 | −0.13 | 0.026 | −0.073 | 0.22 (0.44) | −0.092 | 0.11 | 0.046 | 0.40 (0.63) |

| MRI MEASURES | ||||||||

| WML volume | −0.14 | 0.020 | −0.030 | 0.64 (0.81) | −0.25 | <0.001 | −0.098 | 0.086 (0.24) |

| Hippocampal volume | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.27 | <0.001 (0.011) | 0.33 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.014 (0.062) |

| Entorhinal/parahippocampal ctx | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 (0.011) | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.043 | 0.46 (0.67) |

| Temporal ctx | 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.012 (0.062) | 0.21 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.96 (0.98) |

| Frontal ctx | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.022 0.081) | 0.16 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.98) |

| Parietal ctx | 0.16 | 0.006 | 0.083 | 0.17 (0.37) | 0.16 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.94 (0.98) |

| Occipital ctx | 0.13 | 0.030 | 0.051 | 0.40 (0.63) | 0.18 | 0.001 | 0.059 | 0.28 (0.51) |

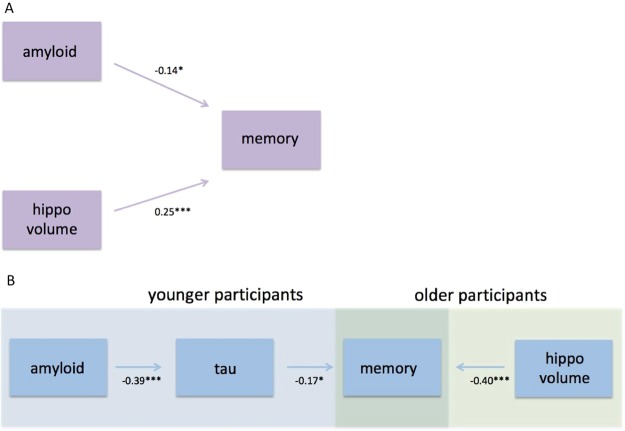

When including all the biomarkers that were significant (not adjusted for multiple comparisons) after controlling for demographic variables in the same model, Aβ positivity (β = −0.14; p = 0.010) and smaller HV (β = 0.25; p < 0.001), but not temporal or frontal cortical thickness, were independently associated with worse memory (Table 3 and Fig. 1A). In Supplementary Table 2, different linear regression models including all or subsets of these biomarkers are shown.

Table 3.

Independent effects of amyloid pathology and hippocampal volume on memory function. Multivariable linear regression, with ADAS-Cog delayed recall as dependent variable. Standardized beta coefficients with p values (unadjusted and false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted in parentheses) are presented as well as the R2 value for the whole model. Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid-β.

| β | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.054 | 0.44 (0.59) |

| Sex | 0.11 | 0.11 (0.19) |

| Education | 0.087 | 0.12 (0.19) |

| Intracranial volume | −0.17 | 0.030 (0.08) |

| Aβ positivity | −0.14 | 0.010 (0.04) |

| Hippocampal volume | 0.25 | <0.001 (0.008) |

| Temporal cortex | 0.044 | 0.72 (0.72) |

| Frontal cortex | 0.042 | 0.71 (0.72) |

| R2 | 0.143 | |

Figure 1.

Effects of amyloid, tau, and hippocampal volume on memory function. (A) Shows the independent effects of amyloid pathology and HV on memory function, using a multivariable linear regression with ADAS-Cog delayed recall as dependent variable, and amyloid positivity, HV, and frontal (ns), and temporal cortical thickness (ns) as independent variables, controlling for age, sex, education, and total intracranial volume. (B) Shows the age-dependent effects of amyloid pathology, tau pathology, and HV on memory function. The effects of amyloid positivity and HV on memory performance were tested in the two age groups separately (see Suppl. Table 3). Two separate multivariable linear regressions were performed, in the younger group with amyloid positivity as independent variable and ADAS- Cog delayed recall as dependent variable (controlling for age, sex, and education), and in the older group with HV as independent variable and ADAS-Cog delayed recall as dependent variable (controlling for age, sex, education, and total intracranial volume). Secondarily, a simple mediation analysis was performed, analysing the associations between a) amyloid positivity and P-tau (controlling for age and sex) and b) P-tau and memory performance (controlling for amyloid pathology, age, and sex). Standardized beta coefficients are presented, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Associations between biomarkers and attention/executive function

Higher P-tau (β = −0.13; p = 0.027) and T-tau (β = −0.14; p = 0.018) were associated with worse performance on the composite attention/executive score unadjusted, but not when controlling for age, sex, and education (Table 2). No associations were seen between attention/executive function and Aβ positivity or YKL-40 (Table 2). Larger WML volume (β = −0.25; p < 0.001), smaller total HV (β = 0.33; p < 0.001), and thinner cortex of all regions studied (β 0.16–0.22; p 0.001–0.007) were associated with worse attention/executive function, but when controlling for age, sex, and education (and for HV also ICV), only HV remained significantly associated (β = 0.16; p = 0.014; Table 2). When replacing total HV with left (β = 0.16; p = 0.012) or right HV (β = 0.13; p = 0.037) the results were similar.

Associations between Aβ and brain structure

There was no association between Aβ positivity and HV, neither unadjusted (β = −0.033; p = 0.57) nor when adjusting for age, sex, and ICV (β = 0.011; p = 0.81). When replacing total HV with left (β = −0.011; p = 0.81) or right HV (β = 0.031; p = 0.52) and adjusting for age, sex, and ICV, the results were similar. Likewise, there were no associations between Aβ positivity and any of the measures of cortical thickness, neither unadjusted (β −0.071–0.026; p 0.22–0.91) nor when adjusting for age and sex (β −0.038–0.051; p 0.36–0.74).

Interactions between biomarkers and age to predict cognition

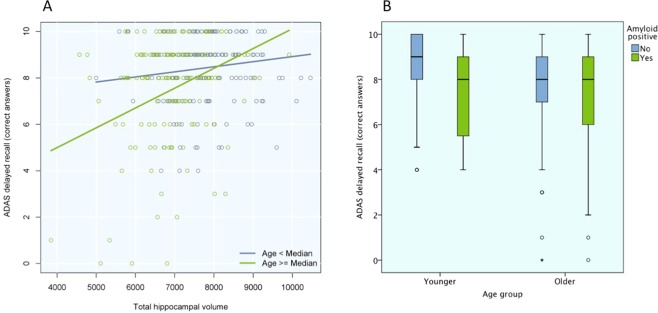

A significant interaction effect between total HV and age (used as a continuous predictor) on memory was seen (p = 0.040). Secondarily, we performed an exploratory analysis with the sample divided into younger and older participants, split by the median age (73.3 years). When using age as a dichotomous predictor, similar results were seen for the interaction effect (p = 0.007). When stratifying into the two age groups, the relationship between HV and memory was not statistically significant in the younger group (p = 0.066), but in the older group there was a highly significant relationship when controlling for demographic variables (β = 0.40; p < 0.001; Figs 1B and 2A, Suppl. Table 3).

Figure 2.

Age-dependent associations for hippocampal volume and amyloid positivity with memory. (A) Shows the age-dependent associations between HV and memory. The effect of HV on memory performance was tested in the two age groups separately. Linear regression were tested with HV as independent variable and ADAS-Cog delayed recall as dependent variable, controlling for age, sex, education, and total intracranial volume. Results for the younger (blue) and older (green) participants are presented separately. (B) Shows the age-dependent associations between amyloid positivity and memory with a box-plot showing the results on ADAS-Cog, divided by age group (younger to the left, older to the right) and amyloid status (Aβ negative in blue, Aβ positive in green), unadjusted.

No significant interaction was detected between Aβ positivity and age on memory (p = 0.38), but when stratifying into the two age groups, the opposite from HV was seen, i.e. there was an association between Aβ positivity and worse memory in the younger group (β = −0.23; p = 0.003), but not in the older group (p = 0.38; Figs 1B and 2B, Suppl. Table 3). Based on the theoretical model of amyloid pathology preceding tau pathology in AD52, we tested if the association between Aβ positivity and memory was mediated by P-tau. When adding P-tau in the model in the younger group, a statistical mediation effect was seen, i.e. higher P-tau (β = −0.17; p = 0.045) but not Aβ positivity (β = −0.15; p = 0.079) was significantly associated with worse memory (Fig. 1B, Suppl. Table 4), and Aβ positivity was associated with higher P-tau (β = −0.39; p < 0.001; Fig. 1B, Suppl. Table 5) when controlling for age and sex.

No significant interactions were seen between any of the other CSF/MRI biomarkers and continuous age on memory, and no interactions with age were seen for any of the biomarkers on attention/executive function (data not shown). We also looked on interactions on memory function between Aβ positivity and sex and education respectively, as well as between HV and sex and education respectively. None of these interactions were significant (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study of cognitively unimpaired elderly, we found that (1) Aβ positivity, HV, and cortical thickness (temporal and frontal) were associated with worse memory, with independent effects of Aβ and HV on memory; (2) the Aβ effect on memory could be confirmed in the younger part of the sample, while the HV effect on memory was significant in the older part of the sample only; (3) Aβ positivity was not related to atrophy; and (4) biomarkers of white matter lesions and inflammation were not associated with memory or attention/executive function when controlling for demographic covariates. Taken together, our findings indicate that Aβ pathology and brain atrophy are independent contributors to subtle memory decline in cognitively healthy elderly. Furthermore, Aβ pathology mainly influences memory in the younger part of the population, possibly through mechanisms such as tau that do not require gross atrophy. With advancing age, the effect of brain atrophy seems to overtake the effect of Aβ on memory function.

Our findings are in agreement with previous studies where brain structure and Aβ pathology also were independently associated with memory performance in cognitively unimpaired, without an association between Aβ and atrophy10,38. Some studies have argued that the Aβ effect on memory is mediated by neurodegeneration9,36, at least to some degree16,37. However, the studies showing that neurodegeneration mediates the effect of Aβ on memory included patients with MCI in their analyses9,16,36,37, while the independent effect was seen when analysing cognitively unimpaired separately or adjusting for diagnosis as a co-variate10,38. One interpretation of this is that later on in the AD process, the Aβ effect on memory is in part mediated through atrophy, but in the preclinical stages of the disease, Aβ pathology affects memory performance without being associated with atrophy. Such atrophy-independent effects of Aβ could depend on early tau pathology, causing dysfunction of neurons or loss of synapses, without gross atrophy. This hypothesis is supported by the statistical mediation effect of P-tau in the present study, where Aβ no longer had a significant association with memory when including P-tau in the model (Fig. 1B, Suppl. Table 4). However, the effect of P-tau on memory was not very strong and a trend was still seen for Aβ (p = 0.079) and this mediation effect needs to be studied further.

The age dependent associations between amyloid pathology, hippocampal volume, and memory have in part been described before in cognitively unimpaired subjects, where memory function has been shown to be more vulnerable to hippocampal volume loss at older age39,40. This could imply that the function of other areas important for memory performance is impaired at higher age, contributing to worse memory without the need of as much hippocampal atrophy as in younger individuals. This is plausible considering age as a proxy of known and unknown processes, which can affect brain structure and function, such as TDP-43 accumulation53. Aβ was associated with memory in the younger but not the older participants. However, in the absence of a statistically significant interaction effect between amyloid and age on memory, the interpretation of this should be made with caution. This age difference could be explained by other pathologies being more common in the older group, which may overshadow the effect of Aβ pathology on memory.

An association with attention/executive function was seen for HV, but not for any of the cortical thickness measures. This could be due to a larger variability in the HV variable, making it easier to find an existing association. Also, there are substantial interindividual differences between cortical thickness measures, making these analyses hard to interpret in cross-sectional studies54.

This study has its limitations. First, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is a cross-sectional study, which means you cannot establish temporal changes of the variables. Second, studies have shown P-/T-tau to only exhibit moderate55,56 or no57 correlation with tau neuropathology, while the correlation between tau-PET (AV-1451) and tau neuropathology is stronger58. Therefor, using tau-PET instead of CSF P-tau in the mediation analysis may give different, and more accurate, results. Third, the memory test used only has ten levels and this in combination with the high overall cognitive performance may result in a ceiling effect. This would make it harder to find an actual association, which is a reason to interpret negative findings with some caution.

In conclusion we found that Aβ positivity in cognitively unimpaired people affects memory function without involvement of brain atrophy. It indicates that, of the pathologies studied here, Aβ pathology contributes the most to memory decline in cognitively unimpaired younger elderly. With increasing age, this effect may be overshadowed by other pathological processes, which lead to brain atrophy. To understand the mechanisms of cognitive impairment in the elderly, future studies would benefit from analyses of other biomarkers that may provide a more detailed characterization of other age-associated brain changes, for example being able to study α-synuclein and TDP-43 pathology in vivo.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Work at the authors’ research centre was supported by the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation, the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg foundation, the Strategic Research Area MultiPark (Multidisciplinary Research in Parkinson’s disease) at Lund University, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, the Swedish Brain Foundation, The Parkinson foundation of Sweden, The Parkinson Research Foundation, the Skåne University Hospital Foundation, the Swedish federal government under the ALF agreement, Kockska foundation and the Bundy Academy.

Author Contributions

A.L.S. performed the calculations and wrote the main manuscript. O.H. and S.P. contributed as senior authors and conceived the original idea. All authors provided feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Competing Interests

O.H. has acquired research support (for the institution) from Roche, G.E. Healthcare, Biogen, AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, Fujirebio, and Euroimmun. In the past 2 years, he has received consultancy/speaker fees (paid to the institution) from Biogen, Roche, and Fujirebio. A.L.S., E.S., P.S.I., N.M. and S.P. report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sebastian Palmqvist and Oskar Hansson jointly supervised this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-47638-y.

References

- 1.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowe CC, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010;31:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mormino EC. The relevance of beta-amyloid on markers of Alzheimer’s disease in clinically normal individuals and factors that influence these associations. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2014;24:300–312. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9267-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansen WJ, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:1924–1938. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwan MD, et al. Subjective Memory Complaints in APOEvarepsilon4 Carriers are Associated with High Amyloid-beta Burden. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49:1115–1122. doi: 10.3233/jad-150446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack CR, Jr., et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pike KE, et al. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:2837–2844. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mormino EC, et al. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain. 2009;132:1310–1323. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, et al. Spatially distinct atrophy is linked to beta-amyloid and tau in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;84:1254–1260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen RC, et al. Association of Elevated Amyloid Levels With Cognition and Biomarkers in Cognitively Normal People From the Community. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:85–92. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araque Caballero MA, Kloppel S, Dichgans M, Ewers M, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I. Spatial Patterns of Longitudinal Gray Matter Change as Predictors of Concurrent Cognitive Decline in Amyloid Positive Healthy Subjects. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55:343–358. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aizenstein HJ, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storandt M, Mintun MA, Head D, Morris JC. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Abeta deposition. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:1476–1481. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dore V, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of the relationship between Abeta deposition, cortical thickness, and memory in cognitively unimpaired individuals and in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:903–911. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattsson N, et al. Brain structure and function as mediators of the effects of amyloid on memory. Neurology. 2015;84:1136–1144. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettigrew C, et al. Relationship between cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neuropsychologia. 2015;78:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mielke MM, et al. Influence of amyloid and APOE on cognitive performance in a late middle-aged cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker JE, et al. Cognitive impairment and decline in cognitively normal older adults with high amyloid-beta: A meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;6:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donohue MC, et al. Association Between Elevated Brain Amyloid and Subsequent Cognitive Decline Among Cognitively Normal Persons. JAMA. 2017;317:2305–2316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Insel PS, et al. Cognitive and functional changes associated with Abeta pathology and the progression to mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;48:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson PT, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012;71:362–381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glodzik L, et al. Phosphorylated tau 231, memory decline and medial temporal atrophy in normal elders. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:2131–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aschenbrenner AJ, et al. Alzheimer Disease Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers Moderate Baseline Differences and Predict Longitudinal Change in Attentional Control and Episodic Memory Composites in the Adult Children Study. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2015;21:573–583. doi: 10.1017/s1355617715000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heneka MT, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig-Schapiro R, et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janelidze S, et al. CSF biomarkers of neuroinflammation and cerebrovascular dysfunction in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e867–e877. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prins ND, et al. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain. 2005;128:2034–2041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer JH, et al. Longitudinal MRI and cognitive change in healthy elderly. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:412–418. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persson J, et al. Longitudinal structure-function correlates in elderly reveal MTL dysfunction with cognitive decline. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:2297–2304. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward AM, et al. Relationships between default-mode network connectivity, medial temporal lobe structure, and age-related memory deficits. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedden T, et al. Multiple Brain Markers are Linked to Age-Related Variation in Cognition. Cereb. Cortex. 2016;26:1388–1400. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickerson BC, et al. The cortical signature of Alzheimer’s disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid-positive individuals. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:497–510. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jack CR, Jr., et al. Different definitions of neurodegeneration produce similar amyloid/neurodegeneration biomarker group findings. Brain. 2015;138:3747–3759. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickerson BC, et al. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2011;76:1395–1402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim YY, et al. Relationships between performance on the Cogstate Brief Battery, neurodegeneration, and Abeta accumulation in cognitively normal older adults and adults with MCI. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2015;30:49–58. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villeneuve S, et al. Cortical thickness mediates the effect of beta-amyloid on episodic memory. Neurology. 2014;82:761–767. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chetelat G, et al. Independent contribution of temporal beta-amyloid deposition to memory decline in the pre-dementia phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2011;134:798–807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorbach T, et al. Longitudinal association between hippocampus atrophy and episodic-memory decline. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;51:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaup A. R., Mirzakhanian H., Jeste D. V., Eyler L. T. A Review of the Brain Structure Correlates of Successful Cognitive Aging. Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 2011;23(1):6–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.23.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansson O, et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-beta PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1470–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janelidze S, et al. CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 and Abeta42/Abeta38 ratios: better diagnostic markers of Alzheimer disease. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2016;3:154–165. doi: 10.1002/acn3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desikan RS, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitan RM. The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955;19:393–394. doi: 10.1037/h0044509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. (Western Psychological Services, 1991).

- 48.Palmqvist S, Minthon L, Wattmo C, Londos E, Hansson O. A Quick Test of cognitive speed is sensitive in detecting early treatment response in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2010;2:29. doi: 10.1186/alzrt53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmqvist S, et al. Earliest accumulation of beta-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nature communications. 2017;8:1214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertens D, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE, Visser PJ. Unbiased estimates of cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 1-42 cutoffs in a large memory clinic population. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0233-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Josephs KA, et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy and presence of post-mortem TDP-43 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:917–924. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30284-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raz N, Rodrigue KM. Differential aging of the brain: patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006;30:730–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buerger K, et al. CSF phosphorylated tau protein correlates with neocortical neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006;129:3035–3041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tapiola T, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid {beta}-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:382–389. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Engelborghs S, et al. No association of CSF biomarkers with APOEepsilon4, plaque and tangle burden in definite Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:2320–2326. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith R, et al. 18F-AV-1451 tau PET imaging correlates strongly with tau neuropathology in MAPT mutation carriers. Brain. 2016;139:2372–2379. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.