Abstract

Colorectal adenomas are precursor lesions of colorectal adenocarcinoma. The transition from adenoma to carcinoma in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) has been associated with an accumulation of genetic aberrations. However, criteria that can screen adenoma progression to adenocarcinoma are still lacking. This present study is the first attempt to identify genetic aberrations, such as the somatic mutations, copy number variations (CNVs), and high-frequency mutated genes, found in Thai patients. In this study, we identified the genomic abnormality of two sample groups. In the first group, five cases matched normal-colorectal adenoma-colorectal adenocarcinoma. In the second group, six cases matched normal-colorectal adenomas. For both groups, whole-exome sequencing was performed. We compared the genetic aberration of the two sample groups. In both normal tissues compared with colorectal adenoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma analyses, somatic mutations were observed in the tumor suppressor gene APC (Adenomatous polyposis coli) in eight out of ten patients. In the group of normal tissue comparison with colorectal adenoma tissue, somatic mutations were also detected in Catenin Beta 1 (CTNNB1), Family With Sequence Similarity 123B (FAM123B), F-Box And WD Repeat Domain Containing 7 (FBXW7), Sex-Determining Region Y-Box 9 (SOX9), Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 5 (LRP5), Frizzled Class Receptor 10 (FZD10), and AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1A (ARID1A) genes, which are involved in the Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) signaling pathway. In the normal tissue comparison with colorectal adenocarcinoma tissue, Kirsten retrovirus-associated DNA sequences (KRAS), Tumor Protein 53 (TP53), and Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) genes are found in the receptor tyrosine kinase-RAS (RTK–RAS) signaling pathway and p53 signaling pathway, respectively. These results suggest that APC and TP53 may act as a potential screening marker for colorectal adenoma and early-stage CRC. This preliminary study may help identify patients with adenoma and early-stage CRC and may aid in establishing prevention and surveillance strategies to reduce the incidence of CRC.

Keywords: somatic mutation, colorectal adenoma, early-stage colorectal adenocarcinoma, screen marker

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with increasing numbers of estimated new cases in both males and females [1]. Approximately 0.45% of the population in the USA is diagnosed with CRC [2,3], which is the third most common cancer in the USA. CRC is the second most incident cancer in Thailand. The five-year survival rates of CRC in the early-stage and advanced-stage in males and females are approximately 63%–92% and 11%–89%, respectively [4]. It has been reported that the majority of diagnosed CRC patients in Thailand have advanced-stage cancer (70.80%), with an overall survival rate of 5% [4,5]. Previous studies reported that new CRC cases in Thailand increased by 8.68% and 6.86% in males and females, respectively [5,6]. These results indicated that an effective screening program is necessary for the prevention of CRC in the Thai population [5,7,8]. Therefore, accumulation for mutation information related to CRC in the Thai population by screening for colorectal adenoma, which is the precursor lesion for CRC, and diagnosis of early-stage CRC are both very important for CRC prevention [9,10].

The development of CRC is a complex and heterogeneous process. The transformation of normal colon tissue to a CRC sequence is known to be caused by several genetic aberrations, such as mutations that inactivate tumor suppressor gene function, chromosomal instability, and DNA methylation alteration [11,12,13,14]. The progression from normal tissue to colorectal cancer can be classified into two pathways, which are the traditional pathway and alternative pathway. As for the traditional pathway, the normal cell developed tubular adenomas followed by the development of colorectal cancer through the Wnt signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling pathway, and p53 signaling pathway. The alternative pathway involves sessile serrated polyps and their progression to colorectal cancer by the same sequential pathway as the traditional pathway [11]. Recent advances in DNA sequencing technology have enabled a better understanding of the molecular basis of CRC pathogenesis [13,15,16,17,18]. Comparison of the genetic profile between normal, colorectal adenoma, and CRC in Chinese CRC patients by exome capture sequencing identified somatic gene mutations involved in the Wnt signaling pathway, cell adhesion, and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway [19]. In examining the progression of normal cells to colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma and searching for potential molecular markers, studies have identified differences in driver mutations in sessile serrated adenoma compared with conventional adenoma [20,21]. However, results from a study of African American CRC patients showed different patterns of somatic gene mutations compared with mutations derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data [22].

A recent attempt to establish a screening protocol in the Thai population during July 2009–June 2010 examined new potential CRC screening methods in 1404 healthy volunteers using a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and fecal immunochemical tests (FITs). The obtained results were compared with the screening results by colonoscopy. The study suggested the integration of colonoscopy into the national screening approach for the detection of early-stage CRC [8]. Although the gold standard of CRC early detection is a colonoscopy, this strategy is not cost-effective at the population screening level [23] and may be prone to causing infection by pathogenic bacteria and virus, such as hepatitis B and C, prion disease, Salmonella spp. and HIV [24]. A non-invasive approach can eliminate the risk of infectious disease during the examination. However, methods such as whole-genome sequencing are still expensive. Thus, a non-invasive screening technique with high sensitivity and specificity for early-stage colorectal adenoma and CRC is required [25,26,27].

In general, the treatment of colorectal cancer is chemotherapy, radiotherapy, adjuvant therapy, and surgery [11]. The response rate of the first-line drug which was used in the metastasis stage is 20% [28]. Moreover, the second-line drug which targeted the RAS wild-type has a higher response rate but the side effects may be harmful to patients and affect their quality of life [28]. Recent studies revealed the mechanism of the new therapeutic targets that are involved in cell proliferation, tumor progression, apoptosis, drug resistance, and autophagy [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Inhibition of TGF-β1, FAHFA, which protects tumors from apoptosis, resulting in an enhanced CRC treatment response [31,34]. In addition, the reduction of drug resistance, proliferation, and cancer progression due to silence expression and function of MAGL, HuR, CDC6, and TPC1 represent an innovative therapeutic approach [29,30,32,35]. Moreover, the five-year survival rate of early stage of colorectal cancer is 90% but reduces to 14%–71% in advanced stage [36]. It was found that only 39% of CRC patients were detected in early-stage CRC. This information indicated that increased efficiency of early screening may possibly increase the five-year survival rate and decrease the mortality rate. Therefore, a precise early detection process is vital.

The aim of this study was to identify the genetic abnormalities in genes associated with a high susceptibility of CRC from matched normal, colorectal adenoma, and CRC samples of Thai CRC patients using exome sequencing analysis for potential application as a noninvasive screening marker, such as the amplification of specific genes from stool DNA followed by mutation detection for early screening of precancerous and early-stage CRC.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Gene with Somatic Mutations in Normal-Colorectal Adenoma and Normal-CRC in CRC Patients

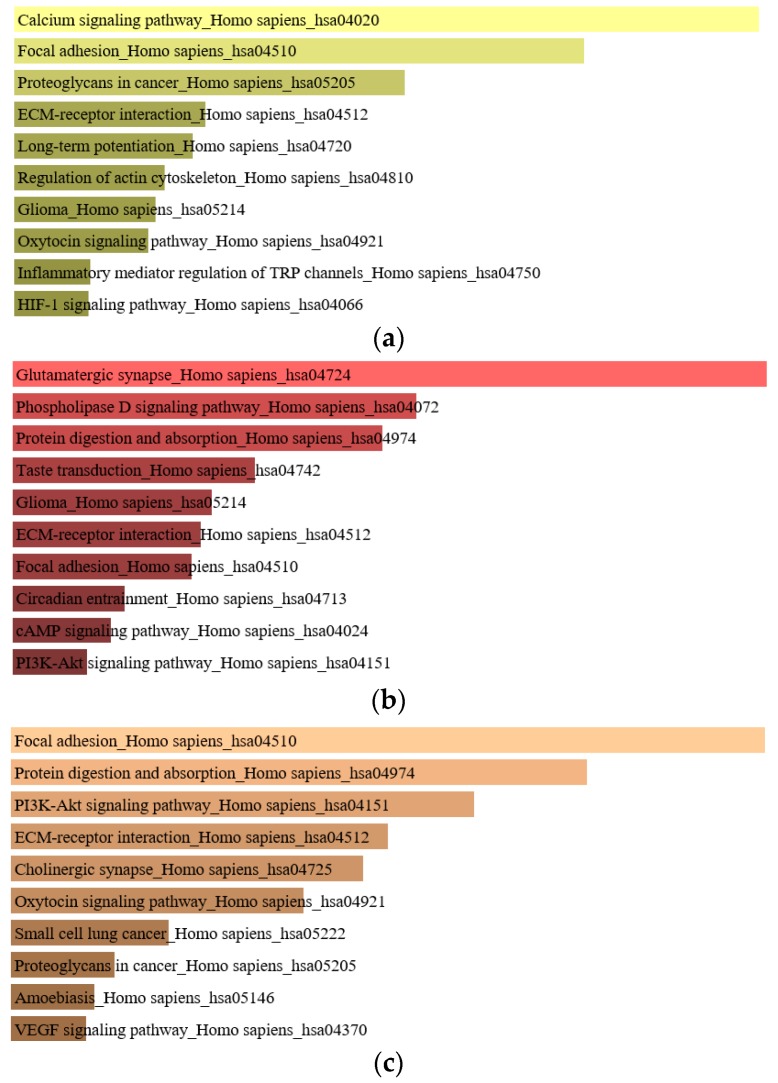

Genes with somatic mutations are mutations that occur in cancer cells and not healthy cells [37], and represent one of the main factors that lead to cancer [38]. A total of 2044 genes with somatic mutations were identified in matched normal-colorectal adenoma, which show enrichment in the calcium signaling pathway, focal adhesion pathway, and proteoglycan in the cancer pathway. A total of 1045 genes with the somatic mutation were classified in matched normal-CRC with enrichment in the glutamatergic synapse pathway, phospholipase D signaling pathway, and protein digestion and absorption pathway. The intersection of a gene with somatic mutations between the matched normal-colorectal adenoma and matched normal-CRC were enriched in the focal adhesion pathway, protein digestion and absorption pathway, and PI3K-Alt signaling pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enriched genes of (a) normal-colorectal adenoma, (b) normal colorectal cancer (CRC), and (c) the intersection of normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC.

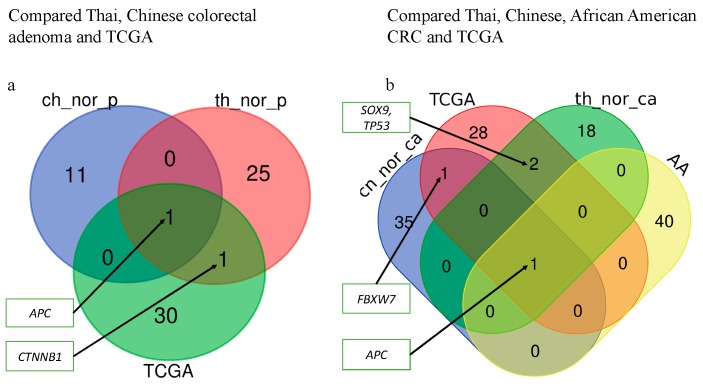

To determine whether the genes with somatic mutations identified from normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC have been reported in other population. The genes with somatic mutations identified from normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC were compared with those of TCGA, African American, and Chinese CRC data. The result revealed different identified genes in the three groups, except APC genes [22]. The African American CRC patient study showed somatic mutations in genes APC, KRAS, Fc Receptor Like 5 (FCRL5), obscurin, cytoskeletal calmodulin and titin-interacting RhoGEF (OBSCN), Retinitis Pigmentosa 1 Like 1 (RP1L1), Dynein Axonemal Heavy Chain 17 (DNAH17), Zinc Finger Protein 568 (ZNF568), and Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 C (CACNA1C) [22]. Based on the TCGA data, the identification of a somatic alteration in CRC was performed by many omics scales within 276 samples. The TCGA analysis result identified gene mutations in APC, TP53, SOX9, KRAS, PIK3CA, TTN, FBXW7, and SMAD4 [13]. The genes with the somatic mutation were compared with TCGA data [13,22] (Figure 2). We found that the identified genes with the somatic mutation from TCGA data showed a minor overlap with those identified from normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC samples. The Chinese study performed whole-exome sequencing for both matched normal-colorectal adenoma and matched normal-CRC to identify the genes with somatic mutations. The matched normal-colorectal adenoma result showed the genes with somatic mutations in APC, AMA3, OR6X1, NMBR, EFR3A, RBFOX1, CDH20, BIRC6, KRT84, SLC15A3, FTHL17, and GLCCI1. The matched normal-CRC revealed the genes with somatic mutation in APC, FBXW7, FLT4, GSK3A, ZFP64, NRXN3, TGM7, GRIK1, KIF25, DTL, GNAL, ATF2, OR51E2, CUX1, PPAP2C, CORO1A, OR13J1, KRTAP19-7, POU4F3, PPP1R3C, NARS2, NFATC2, FAM109A, FAM54A, TFR2, ZNF781, RRP8, ZFP36L2, KRT31, RYR1, KIAA1409, NRG1, PGM1, ALPK1, FAM181A, FCRL3, and SDK1 [19]. Colorectal adenoma samples of p4, p6, p7, p10, p11, p12 exhibit mutations in APC, while p4, p13, and p14 show mutations in CTNNB1. p6 and p11 show mutations in FAM123B. In addition, CRC samples of p5, p10, and p14 reveal the mutation in APC. As for CRC samples of p4, p5, and p10, the mutations of the SOX9 gene were found. While CRC of p2 and p10 exhibit mutations in the TP53 gene (Table S2). Finally, mutations in the FBXW7 and KRAS genes are identified in CRC of p14 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the alter gene between The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Thai patients. The rows show the list of patients. The columns show the list of gene names.

In addition, comparison of the genes with somatic mutations in the normal-CRC, normal-colorectal adenoma groups, the Chinese study, the TCGA data, and African American CRC patients demonstrated that SOX9 and TP53 genes were common genes in the TCGA and Thai normal-CRC data, whereas the CTNNB1 gene was a common gene in the Thai normal-colorectal adenoma and TCGA data. Moreover, the FBXW7 gene was a common gene in Chinese normal-CRC and TCGA (Figure 3) (Table 1). Interestingly, APC was found as a common gene in the four groups.

Figure 3.

Comparison of high-frequency mutated genes. (a) The comparison of genes with somatic mutations from matched normal-colorectal adenoma in Thai CRC samples (th_nor_p), matched normal-colorectal adenoma in Chinese CRC samples (ch_nor_p) and matched normal-CRC in the TCGA sample; (b) the comparison of genes with somatic mutations in matched normal-CRC of Thai people (th_nor_ca), matched normal-CRC in Chinese people (ch_nor_ca), TCGA, and African American (AA) CRC sample.

Table 1.

Genes with somatic mutations identified in this study that overlap with TCGA, Chinese, and African American CRC patient data.

| Patient | Chr | Start | Stop | Reference | Alternative | Gene | Mutation | Exonic Function | Protein Change | Known |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p5t | 5 | 112174631 | 112174631 | C | T | APC | SNV | Stop gain | p.Arg1114Ter | rs121913331, COSM13125 |

| p10t | 5 | 112151185 | 112151185 | T | G | APC | SNV | Splice Region variant | - | |

| p14t | 5 | 112155021 | 112155022 | TG | - | APC | deletion | Frame shift variant | p.Met431ArgfsTer12 | |

| p4low | 5 | 112175639 | 112175639 | C | T | APC | SNV | Stop gain | p.Arg1450Ter | rs121913332, COSM13127 |

| p6low | 5 | 112174249 | 112174249 | T | A | APC | SNV | Stop gain | p.Tyr986Ter | |

| p7low | 5 | 112174129 | 112174129 | A | - | APC | deletion | Frame shift variant | p.Cys947ValfsTer8 | |

| p7low | 5 | 112175255 | 112175255 | G | T | APC | SNV | Stop gain | p.Glu1322Ter | |

| p10low | 5 | 112175390 | 112175391 | - | A | APC | Insertion | Frame shift variant | p.Thr1368AspfsTer7 | |

| p11low | 5 | 112175639 | 112175639 | C | T | APC | SNV | Stop gain | p.Arg1450Ter | rs121913332, COSM13127 |

| p12low | 5 | 112155031 | 112155032 | - | A | APC | Insertion | Frame shift variant | p.Asn436LysfsTer8 | |

| p2t | 17 | 7578510 | 7578510 | G | - | TP53 | Deletion | Frame shift variant | p.C141Afs*29 | COSM69019 |

| p10t | 17 | 7576889 | 7576890 | - | T | TP53 | Insertion | Frame shift variant | p.K320Efs*17 | |

| p4t | 17 | 70119862 | 70119863 | - | TTCGA | SOX9 | Insertion | Missense mutation | p.V291Sfs*94 | |

| p5t | 17 | 70119855 | 70119856 | - | CGAGA | SOX9 | Insertion | Frame shift variant | p.F289Rfs*96 | |

| p10t | 17 | 70118889 | 70118889 | A | A | SOX9 | SNV | Frame shift variant | p.F154Y | |

| p4low | 3 | 41274898 | 41274898 | G | C | CTNNB1 | SNV | Missense mutation | p.Trp383Ser | |

| p13low | 3 | 41266124 | 41266124 | A | G | CTNNB1 | SNV | Missense mutation | p.Thr41Ala | rs121913412 |

| p14low | 3 | 41266097 | 41266097 | G | A | CTNNB1 | SNV | Missense mutation | p.Asp32Asn | rs28931588 |

| p14low | 4 | 153258983 | 153258983 | G | A | FBXW7 | SNV | Stop gain | p.Arg278Ter | |

| p14t | 4 | 153268102 | 153268102 | C | - | FBXW7 | Deletion | Frame shift variant | p.Glu236AsnfsTer3 |

Chr = Chromosome.

2.2. Copy Number Variation (CNVs)

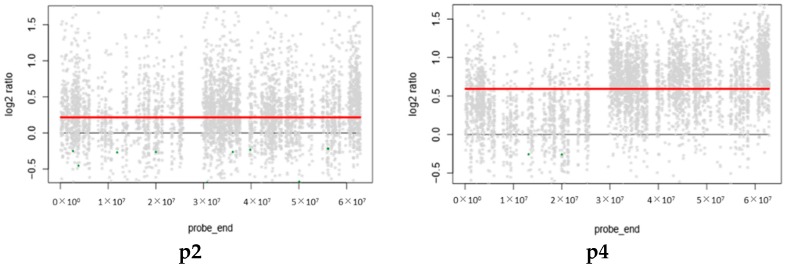

CNVs are structural variations due to chromosome alterations, including duplication or deletion of regions in the genome, that lead to carcinogenesis in tumor patients [39,40]. Early-stage CRC can be detected by the gain of chromosomes 8q, 13, and 20q and loss of chromosomes 8p, 17p, and 18q [41]. Other studies have identified CNVs using plasma and CRC tissues. The finding exhibited the CNVs gain chromosome 20, position 20q12, and the CNVs loss in chromosome 8, position 8p23.1 to 8p23.2 [42]. Therefore, the identification of CNVs may yield more potential markers for further investigation. Here, we identified CNVs from matched normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC only in the autosome. The results revealed the gain of chromosome 20 in four patients (Figure 4). These findings suggest that the gain of chromosome 20 in, for example, the BCL2L1, TPX2, SRC, AURKA, and GNAS genes [43] may be a potential marker for the detection of early-stage CRC (Table S1).

Figure 4.

The gain of copy number variation (CNV) at chromosome 20. Patients p4, p5, p10, and p14 showed the gain of chromosome 20, beside patient p2, who did not pass the criteria.

2.3. The Analysis of Enriched Genes in Normal-Colorectal Adenoma and Normal-CRC Groups

Since colorectal cancer development is involved with several signaling pathways. The analysis of enriched genes provides more information and a better understanding of the colorectal cancer development process. The identified somatic mutation genes in normal-colorectal adenoma are enriched in the calcium signaling pathway, focal adhesion, protein digestion, proteoglycans in cancer, and the extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor pathway. The somatic mutation genes in normal-CRC are enriched in the glutamatergic synapse, phospholipase D signaling pathway, protein digestion and absorption, taste transduction, glioma, ECM-receptor interaction and focal adhesion pathway (Figure 1). The focal adhesion and ECM-receptor pathways play a key role in cancer progression, migration, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis of tumor cells [44,45].

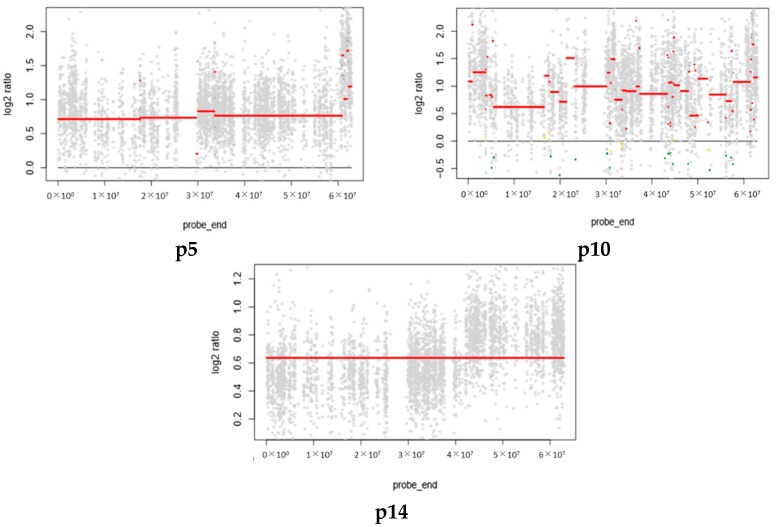

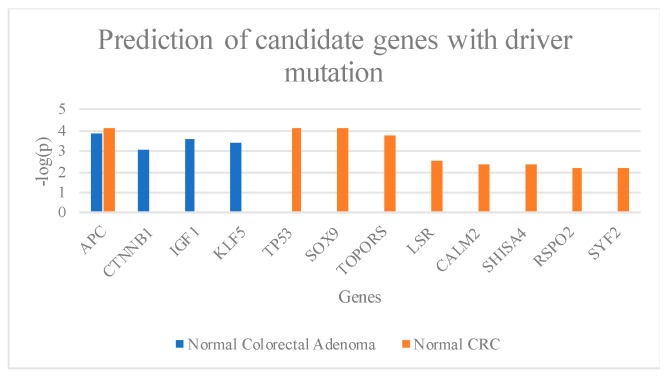

2.4. Candidate Genes with Driver Mutation in Normal-Colorectal Adenoma and Normal-CRC Groups

Candidate genes with driver mutations are genes that participate in the abnormality of cell growth in cancer cells but are not involved in carcinogenesis [38]. It appears that the individual who presents genes with driver mutations may have a greater chance of developing colon cancer. Therefore, the identification of genes with driver mutations in colorectal adenoma and early-stage CRC may help to prevent CRC and improve the survival rate and the quality of life of CRC patients. Our results showed that APC, CTNNB1, IGF1, and KLF5 (Figure 4) were frequently mutated in normal-colorectal adenoma. The result shows four stop gains and three frameshift variants in the APC gene. The CTNNB1 gene contained three missense variants, while IGF1 and KLF5 genes are missense variants (Table S3). The normal-CRC showed mutations in APC, TP53, SOX9, TOPORS, LSR, CALM2, SHISA4, RSPO2, and SYF2 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Prediction of candidate genes with driver mutations from normal-colorectal adenomatous polyps and normal-CRC.

The APC genes contain one stop gain, one frameshift variant, and one splice region variant. The two frameshift variants are detected in TP53 gene. The SOX9 gene contains one missense variant and two frameshift variants. The TOPORS gene shows one stop gain and one frameshift variant. One missense and frameshift variant are found in the LSR gene. The CALM2 gene shows only one splicing region variant. The SHISA4 gene carries in-frame deletion. The RSPO2 gene includes two splice region variants. The SYF2 gene consists of one frameshift variant (Table S3).

3. Discussion

In the last thirty years, the global pattern of incidence and mortality trends of CRC have been divided into three groups: (1) increase of both incidence and mortality, (2) increase in incidence but decrease in mortality, and (3) decrease of both incidence and mortality [46]. The reduction of the mortality rate in groups 2 and 3 is better due to better standard treatment and early detection of colorectal adenoma and CRC. It is suggested that improved screening methods may increase the incidence rate, subsequently reducing the mortality rate in the long-term [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

The progression of normal epithelial cells to CRC involves multiple gene mutations within several signaling pathways, such as the Wnt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K signaling pathway, TGFβ signaling pathway, and p53 signaling pathway [11]. While APC, CTNNB1, LSR, TOPORS, KLF5, IGF1 and SOX9 are related to Wnt signaling pathways, KRAS and BRAF are involved in RAS signaling pathways [54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. This indicates that the abnormalities of proliferative pathways may crucial in early colorectal cancer development. Additionally, the defects of tumor suppressor genes such as ATM and TP53 of the P53 signaling pathways are also at the pivot point of the colorectal tumorigenesis [61,62]. In addition, the CALM2, SHISA4, RSPO2, and SYF2 contributed to cell proliferation [63,64,65,66,67]. However, the role of these genes in the cancer development mechanism has not been elucidated.

Here, we identified mutated genes with somatic mutations in adenoma and CRC samples compared with matched normal samples that are involved in important signaling pathways, including the Wnt and p53 signaling pathways. We identified genes with somatic mutations in the normal-colorectal adenoma samples, APC, CTNNB1, LRP5, FBXW7, and ATM (Figure 2), which overlapped with the TCGA data. Interestingly, the position c.4348C>T (p.R1450*) of the APC gene was found in 2 out of 11 patients in the matched normal-colorectal adenoma tissue. The point mutation was reported as the most common mutation of CRC in previous studies from Tunisia and Iran [68,69]. Moreover, this mutation position was identified as the most frequently mutated position in the colorectal adenoma studied from the United Kingdom, Czech Republic, and the Netherlands also [70]. We also identified genes with somatic mutations in normal-CRC samples, APC, FBXW7, SOX9, KRAS, and TP53 (Figure 2), that overlapped with the TCGA data analysis. All of the identified genes in the present study are the members of the Wnt, p53, and RTK–RAS signaling pathways. The exome sequences obtained from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues of the matched normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC revealed 99.85% coverage in the target region. Analysis of high-frequency mutated genes showed 12 known gene mutations in colon cancer-associated pathways, including APC, TP53, SOX9, TOPORS, IGF1, KLF5, LSR, CALM2, CTNNB1, RSPO2, SYF2, and SHISA4. The normal-colorectal adenoma somatic mutation analysis identified mutations in two key genes, APC and CTNNB1, which are known to be involved in the Wnt signaling pathway. IGF1 contributes to the cell cycle progression and inhibits the apoptosis pathway [71]; IGF1 also promotes cell growth in CRC by activating the VEGF gene and, therefore, supports cancer progression of human colon cancer cells [72]. In addition, KLF5 has been reported as an oncogene that suppresses cancer cell growth and is involved in tumor progression in CRC mouse models [73,74,75,76] (Figure 4). Moreover, a recent study reports that the somatic mutation c.910C>A (p.P304T) position of KLF5 was reported as the hotspot of mutations in the phosphor–degron domain, which promotes cancer cell proliferation [58].

Based on our finding, the normal-CRC showed the candidate genes, including APC, TP53, SOX9, TOPORS, LSR, CALM2, SHISA4, RSPO2, FBXW7, and SYF2. The APC, SOX9, SHISA4, and RSPO2 genes are members of the Wnt signaling pathway [11,65,74,77,78] (Figure 5). The SOX9 gene is overexpressed in both colorectal adenoma and CRC samples compared with normal tissues by 2- and 3.5-fold, respectively [79,80]. SOX9 is not only the downstream regulator and effector of the Wnt signaling pathway but also increases cell proliferation and transformation [80].

Gene function analysis revealed that genes were predominantly enriched in the ECM-receptor interaction and focal adhesion pathways. Integrins directly interact with the components of ECM and contribute to cell motility and invasion. Studies have demonstrated the crucial role of integrins in regulating tumor cell progression and metastasis by increasing tumor cell migration, invasion, proliferation, and survival. Integrin-mediated migration requires focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-Src family kinase (SFK) signaling [44], which are the main kinases in focal adhesion signaling, followed by recruitment of the proteins necessary for focal adhesion development. Tumor cells display highly altered focal adhesion dynamics that may emulate the development and progression of cancer [45].

Wnt/B-catenin is an important signaling cascade involved in both colorectal development and carcinogenesis [81]. The mutations in this pathway are involved in the first step of progress from normal to colorectal adenoma. [82]. Mutation in the p53 signaling pathway is closely associated with the progression of CRC [11]. APC is a tumor suppressor gene and has many functions that affect the progression of cancer cells, such as proliferation, migration, cytoskeletal maintenance, and chromosome instability [83,84]. The TP53 gene plays an important function in either cell proliferation or trigger senescence and apoptosis [85]. Evidence for the roles of APC, TP53, and KRAS as early driver genes has been demonstrated in several reports [62,86]. Mutated APC, TP53, and KRAS have been identified in colon adenoma as well as in CRC [62,86]. Our results suggest that the gene set identified in the Wnt, p53, and RTK–RAS signaling pathways might be used as a candidate precancerous and early-stage screening marker for CRC. However, it could not be concluded that the genes with driver mutations promote the tumorigenesis because, after surgical resection, none of the patients developed colorectal cancer (the median follow-up period was 6.5 years).

Previous studies showed the gain of chromosome 20 in CRC patients and demonstrated its use as a marker to detect early-stage CRC [41,42]. Our results in Thai CRC patients revealed a gain of chromosome 20 in four out of five samples, in agreement with the previous reports (Figure 4). This suggests that the gain of chromosome 20 in CRC patients could act as a marker for the early detection of CRC.

4. Materials and Methods

Here, we identified variants, somatic mutation genes, high-frequency mutated genes, gene list enrichment, and copy number variations (CNVs) following the study flow shown in Figure S1.

4.1. Samples

The patients included in this study were in a CRC screening cohort that underwent colonoscopy at Chulabhorn hospital between July 2009 and June 2010. The present study was approved by the Human Research Ethical Committee of the Chulabhorn Research Institute. All formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens of colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma were obtained from the pathology laboratory unit. The specimens were reviewed by the pathologist to confirm the diagnosis and distinguish between low-grade dysplasia and high-grade dysplasia before performing microdissection.

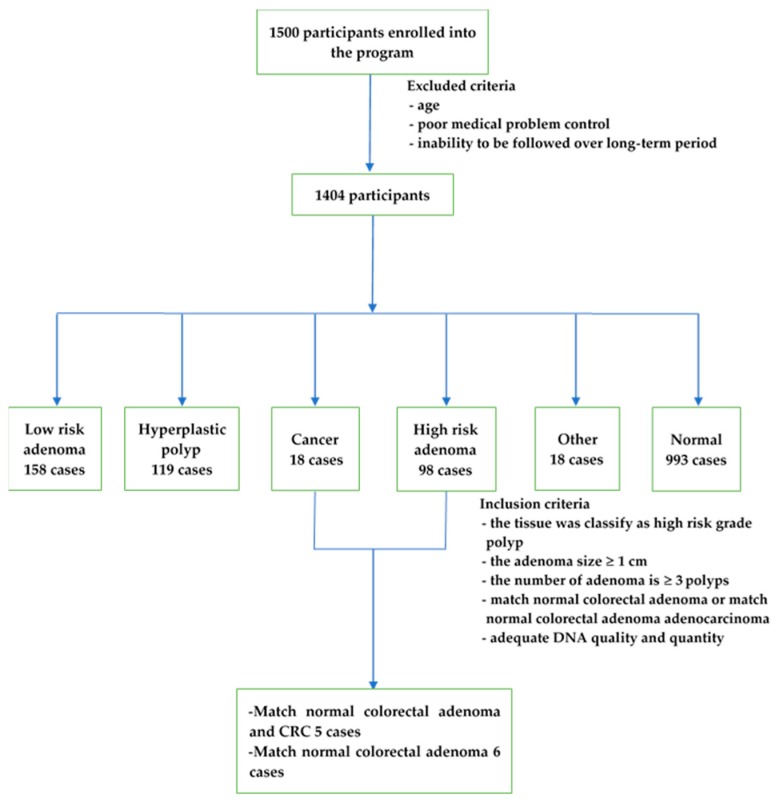

A total of 1500 participants were enrolled in the project (Figure 6). The exclusion criteria included age, poor medical problem control, and the inability to be followed during the study, resulting in 1404 participants [8]. The inclusion criteria were set as (i) colorectal adenoma tissue classified as a high-risk grade, either villous or tubulovillous or sessile serrated polyps, (ii) colorectal adenoma size greater or equal to 1 cm, (iii) the number of colorectal adenomas greater than or equal to 3 polyps, and (iv) matched normal and CRC samples were available. In total, a small cohort of the 5 cases with matched normal and colorectal adenoma tissue and CRC tissue, as well as the 6 cases with matched normal and colorectal adenoma tissue samples, were selected. Patients p2, p4, p6, p7, p10, p11, p12, p13, and p14 had tubular adenoma, while patients p5 and p13_2 had serrated adenoma (Table 2). Among the cases with CRC samples, p4, p5, p10, and p14 showed stage IIA CRC and p2 showed stage I CRC. The locations of most of the specimens were on the left side of the colon, except for the specimen for p10, which was located on the right side.

Figure 6.

Data flow of participants with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (modified from [8]).

Table 2.

The clinical information of colorectal adenomatous and CRC patient.

| Patient | Gender/Age | Adenoma | Adenocarcinoma | Stage/TNM | LVI | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p2 | M/65 | TA | A | I/pT2N0M0 | Y | L |

| p4 | M/55 | TA | A | IIA/pT3N0M0 | N | L |

| p5 | F/58 | SA | A | IIA/pT3N0M0 | Y | L |

| p6 | M/64 | TA | - | - | N | L |

| p7 | M/58 | TA | - | - | N | L |

| p10 | F/56 | TA | A | IIA/pT3N0M0 | Y | R |

| p11 | M/58 | TA | - | - | N | L |

| p12 | M/60 | TA | - | - | N | L |

| p13 | M/61 | TA | - | - | N | L |

| p13_2 | M/61 | SA | - | - | N | L |

| p14 | M/66 | TA | A | IIA/pT3N0M0 | N | L |

M = male, F = female, TA = Tubular adenoma, SA = Serrated adenoma, A = adenocarcinoma, L = left, R = right, LVI = Lymphovascular Invasion, Y = Yes, N = No.

4.2. DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using a QIAmp DNA Microkit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The DNA quality and quantity were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Nanodrop Technology, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. Exome sequencing was performed by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) using the SureSelect human all exon kit V4+UTR (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the exome library of 101 bases paired reads were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at 100 reads coverage.

4.3. Whole-Exome Analysis

To identify point mutations and somatic mutations, the raw FASTQ files were trimmed by trimmomatic [87], then aligned to a human reference genome (GRCh37) by Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool (BWA) [88]; duplicate reads were removed by Picard tools [89] and variant calling was performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit pipeline [90]. Variants were filtered by two criteria: read coverage >50-fold coverage and Phred score >30. The genes with the somatic mutations were predicted in matched normal colorectal adenoma and tumors using MuTect2 [91]. Genes with somatic mutations were filtered by the depth coverage >20-fold coverage. Somatic mutation annotation was performed by Variant Effect Predictor [92]. Default parameters were used in all software analyses.

4.4. CNV Analysis

CNV was identified in matched normal-colorectal adenoma and normal-CRC samples using “ExomeCNV” [93] in the R package with default parameters. The criteria to identify gain or loss of copy number variation used absolute log2 of ratios >0.5 [94] with default parameters.

4.5. The Analysis of Enriched Genes

The analyses of enriched genes in the colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma were performed by the use of genes with somatic mutations in the matched normal-colorectal adenoma and matched normal-CRC. Enrichr was used to identify the enriched genes and the enrichment pathway [95,96].

4.6. The Genes with Driver Mutation Analysis

The matched normal-colorectal adenoma and matched normal-CRC data were used to identify genes with driver mutations using the MutSigCV application with the default parameters [17].

4.7. Availability of Data/Materials

The raw data can be found at the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), accession number PRJNA494574.

5. Conclusions

To identify markers for the early detection of CRC, we explored the genetic alterations in six cases with matched normal colorectal adenoma and five cases with matched normal colorectal adenoma CRC. We performed whole-exome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis focused on CNV, somatic mutations, and candidate genes with driver mutations. Our discoveries showed that the gene sets identified in both matched normal colorectal adenoma and matched normal colorectal adenoma and the CRC group are involved in the Wnt, p53, and RTK–RAS signaling pathways. It might be used as a precancerous and early-stage screening marker candidate for CRC.

However, this finding should be validated in a large sample size. One limitation of the current study is its small sample size, and thus more samples in a larger analysis are required for future studies to validate our findings.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by research funding from the Chalabhorn Royal Academy. The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi through the “KMUTT 55th Anniversary Commemorative Fund”. IN, TW and PJ are partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Science of the National Institute of Health award number P20GM125503. The high-performance computing clusters were supported by University of Arkansas for Medical Science and Systems biology and Bioinformatics group, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi. We thank Sasithorn Chotewuthmontri and MDPI for reading editing a draft of this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/11/7/977/s1, Figure S1: Data flow of the project, Table S1: Cancer related genes in chromosome 20, Table S2: Somatic mutation master table, Table S3: Predicted candidate genes with driver mutation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I., W.U., W.L., S.S., K.K., W.K., C.T., P.J., T.W., I.N., C.A., and S.C.; methodology, T.I., W.U., P.J., T.W., I.N., C.A., and S.C.; software, T.I., P.J., I.N., and S.C.; validation, T.I., P.J. and S.C.; formal analysis, T.I., S.S., P.J., and S.C.; investigation, P.J., T.W., I.N., C.A., and S.C.; resources, W.U., C.B., J.Y., K.S., K.W., W.L., T.S., W.C., and B.S.; data curation, T.I., P.J., T.W., I.N., and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.I., W.U., S.S.; writing—review and editing, P.J., T.W., I.N., C.A., and S.C.; visualization, T.I. and S.C.; supervision, P.J., T.W., I.N., C.A. and S.C.; project administration, C.A., and S.C.; funding acquisition, C.A., and S.C.

Funding

This research was funded by Chulabhorn Royal Academy and King Mongkut’s University of technology Thonburi Grants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K.D., Siegel R.L., Lin C.C., Mariotto A.B., Kramer J.L., Rowland J.H., Stein K.D., Alteri R., Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau U.S. and World Population Clock. [(accessed on 14 April 2018)]; Available online: https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- 4.Phiphatpatthamaamphan K., Vilaichone R. Colorectal Cancer in the Central Region of Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3647–3650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Information Technology Division, National Cancer Institute of Thailand . Hospital-Based Cancer Registry 2017. Pornsup Printing Co., Ltd.; Bangkok, Thailand: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Information Technology Division, National Cancer Institute of Thailand . Hospital-Based Cancer Registry 2016. Pornsup Printing Co., Ltd.; Bangkok, Thailand: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khuhaprema T., Srivatanakul P. Colon and rectum cancer in Thailand: An overview. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;38:237–243. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siripongpreeda B., Mahidol C., Dusitanond N., Sriprayoon T., Muyphuag B., Sricharunrat T., Teerayatanakul N., Chaiwong W., Worasawate W., Sattayarungsee P., et al. High prevalence of advanced colorectal neoplasia in the Thai population: A prospective screening colonoscopy of 1404 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:101. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0526-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fedewa S.A., Ahnen D.J., Meester R.G.S., Barzi A., Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meester R.G., Doubeni C.A., Zauber A.G., Goede S.L., Levin T.R., Corley D.A., Jemal A., Lansdorp-Vogelaar I. Public health impact of achieving 80% colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States by 2018. Cancer. 2015;121:2281–2285. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuipers E.J., Grady W.M., Lieberman D., Seufferlein T., Sung J.J., Boelens P.G., van de Velde C.J., Watanabe T. Colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1:15065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., Velculescu V.E., Zhou S., Diaz L.A., Jr., Kinzler K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muzny D.M., Bainbridge M.N., Chang K., Dinh H.H., Drummond J.A., Fowler G., Kovar C.L., Lewis L.R., Morgan M.B., Newsham I.F., et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carethers J.M., Jung B.H. Genetics and Genetic Biomarkers in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1177–1190. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood L.D., Parsons D.W., Jones S., Lin J., Sjoblom T., Leary R.J., Shen D., Boca S.M., Barber T., Ptak J., et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guda K., Veigl M.L., Varadan V., Nosrati A., Ravi L., Lutterbaugh J., Beard L., Willson J.K.V., Sedwick W.D., Wang Z.J., et al. Novel recurrently mutated genes in African American colon cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1149–1154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417064112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence M.S., Stojanov P., Polak P., Kryukov G.V., Cibulskis K., Sivachenko A., Carter S.L., Stewart C., Mermel C.H., Roberts S.A., et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brim H., Ashktorab H. Genomics of Colorectal Cancer in African Americans. Next Gener. Seq. Appl. 2016;3 doi: 10.4172/2469-9853.1000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou D.E., Yang L., Zheng L.T., Ge W.T., Li D., Zhang Y., Hu X.D., Gao Z.B., Xu J.H., Huang Y.Q., et al. Exome Capture Sequencing of Adenoma Reveals Genetic Alterations in Multiple Cellular Pathways at the Early Stage of Colorectal Tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borras E., San Lucas F.A., Chang K., Zhou R., Masand G., Fowler J., Mork M.E., You Y.N., Taggart M.W., McAllister F., et al. Genomic Landscape of Colorectal Mucosa and Adenomas. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016;9:417–427. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin S.H., Raju G.S., Huff C., Ye Y., Gu J., Chen J.S., Hildebrandt M.A.T., Liang H., Menter D.G., Morris J., et al. The somatic mutation landscape of premalignant colorectal adenoma. Gut. 2018;67:1299–1305. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashktorab H., Daremipouran M., Devaney J., Varma S., Rahi H., Lee E., Shokrani B., Schwartz R., Nickerson M.L., Brim H. Identification of Novel Mutations by Exome Sequencing in African American Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cancer. 2015;121:34–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawler M., Alsina D., Adams R.A., Anderson A.S., Brown G., Fearnhead N.S., Fenwick S.W., Halloran S.P., Hochhauser D., Hull M.A., et al. Critical research gaps and recommendations to inform research prioritisation for more effective prevention and improved outcomes in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2018;67:179–193. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovaleva J., Peters F.T.M., van der Mei H.C., Degener J.E. Transmission of Infection by Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Bronchoscopy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:231–254. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00085-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imperiale T.F., Ransohoff D.F., Itzkowitz S.H. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:187–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J., Feng Q., Wong S.H., Zhang D., Liang Q.Y., Qin Y.W., Tang L.Q., Zhao H., Stenvang J., Li Y.L., et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:70–78. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muguruma N., Tanaka K., Teramae S., Takayama T. Colon capsule endoscopy: Toward the future. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;10:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12328-016-0710-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohelnikova-Duchonova B., Melichar B., Soucek P. FOLFOX/FOLFIRI pharmacogenetics: The call for a personalized approach in colorectal cancer therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10316–10330. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pagano E., Borrelli F., Orlando P., Romano B., Monti M., Morbidelli L., Aviello G., Imperatore R., Capasso R., Piscitelli F., et al. Pharmacological inhibition of MAGL attenuates experimental colon carcinogenesis. Pharmacol. Res. 2017;119:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giri A.K., Aittokallio T. DNMT inhibitors increase methylation in the cancer genome. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:385. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon J.R., Oh S.J., Lee C.K., Chi S.G., Kim H.J. TGF-β1 protects colon tumor cells from apoptosis through XAF1 suppression. Int. J. Oncol. 2019;54:2117–2126. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai J., Wang H., Jiao X., Huang R., Qin Q., Zhang J., Chen H., Feng D., Tian X., Wang H. The RNA-binding protein HuR confers oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer by upregulating CDC6. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koustas E., Sarantis P., Kyriakopoulou G., Papavassiliou A.G., Karamouzis M.V.J.C. The Interplay of Autophagy and Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer—Ways of Enhancing Immunotherapy Action. Cancers. 2019;11:533. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez J.P., Guijas C., Astudillo A.M., Rubio J.M., Balboa M.A., Balsinde J.J.C. Sequestration of 9-Hydroxystearic Acid in FAHFA (Fatty Acid Esters of Hydroxy Fatty Acids) as a Protective Mechanism for Colon Carcinoma Cells to Avoid Apoptotic Cell Death. Cancers. 2019;11:524. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faris P., Pellavio G., Ferulli F., Di Nezza F., Shekha M., Lim D., Maestri M., Guerra G., Ambrosone L., Pedrazzoli P.J.C. Nicotinic Acid Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NAADP) Induces Intracellular Ca2+ Release through the Two-Pore Channel TPC1 in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cancers. 2019;11:542. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson I.R., Takahashi K., Futreal P.A., Chin L. Emerging patterns of somatic mutations in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:703–718. doi: 10.1038/nrg3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stratton M.R., Campbell P.J., Futreal P.A. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shlien A., Malkin D. Copy number variations and cancer. Genome Med. 2009;1:62. doi: 10.1186/gm62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang N., Wang M., Zhang P., Huang T. Classification of cancers based on copy number variation landscapes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:2750–2755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J.F., Kang Q., Ma X.Y., Pan Y.M., Yang L., Jin P., Wang X., Li C.G., Chen X.C., Wu C., et al. A Novel Method to Detect Early Colorectal Cancer Based on Chromosome Copy Number Variation in Plasma. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018;45:1444–1454. doi: 10.1159/000487571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassan N.Z.A., Mokhtar N.M., Sin T.K., Rose I.M., Sagap I., Harun R., Jamal R. Integrated Analysis of Copy Number Variation and Genome-Wide Expression Profiling in Colorectal Cancer Tissues. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ptashkin R.N., Pagan C., Yaeger R., Middha S., Shia J., O’Rourke K.P., Berger M.F., Wang L., Cimera R., Wang J.J., et al. Chromosome 20 q Amplification Defines a Subtype of Microsatellite Stable, Left-Sided Colon Cancers with Wild-type RAS/RAF and Better Overall Survival. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:708–713. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desgrosellier J.S., Cheresh D.A. Integrins in cancer: Biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:890. doi: 10.1038/nrc2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maziveyi M., Alahari S.K. Cell matrix adhesions in cancer: The proteins that form the glue. Oncotarget. 2017;8:48471–48487. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnold M., Sierra M.S., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66:683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camma C., Giunta M., Fiorica F., Pagliaro L., Craxi A., Cottone M. Preoperative radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:1008–1015. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Renehan A.G., Egger M., Saunders M.P., O’Dwyer S.T. Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2002;324:813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGregor S.E., Hilsden R.J., Li F.X., Bryant H.E., Murray A. Low uptake of colorectal cancer screening 3 yr after release of national recommendations for screening. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1727–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atkin W.S., Edwards R., Kralj-Hans I., Wooldrage K., Hart A.R., Northover J.M., Parkin D.M., Wardle J., Duffy S.W., Cuzick J., et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuriki K., Tajima K. The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer and the preventive strategy in Japan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2006;7:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levin B., Lieberman D.A., McFarland B., Andrews K.S., Brooks D., Bond J., Dash C., Giardiello F.M., Glick S., Johnson D., et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith R.A., Andrews K.S., Brooks D., Fedewa S.A., Manassaram-Baptiste D., Saslow D., Brawley O.W., Wender R.C. Cancer screening in the United States, 2017: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:100–121. doi: 10.3322/caac.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L., Shay J.W. Multiple Roles of APC and its Therapeutic Implications in Colorectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao C., Wang Y., Broaddus R., Sun L., Xue F., Zhang W. Exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 drive tumorigenesis: A review. Oncotarget. 2018;9:5492–5508. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reaves D.K., Hoadley K.A., Fagan-Solis K.D., Jima D.D., Bereman M., Thorpe L., Hicks J., McDonald D., Troester M.A., Perou C.M., et al. Nuclear Localized LSR: A Novel Regulator of Breast Cancer Behavior and Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:165–178. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0085-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marshall H., Bhaumik M., Aviv H., Moore D., Yao M., Dutta J., Rahim H., Gounder M., Ganesan S., Saleem A., et al. Deficiency of the dual ubiquitin/SUMO ligase Topors results in genetic instability and an increased rate of malignancy in mice. BMC Mol. Biol. 2010;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang X., Choi P.S., Francis J.M., Gao G.F., Campbell J.D., Ramachandran A., Mitsuishi Y., Ha G., Shih J., Vazquez F., et al. Somatic Superenhancer Duplications and Hotspot Mutations Lead to Oncogenic Activation of the KLF5 Transcription Factor. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:108–125. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vigneri P.G., Tirro E., Pennisi M.S., Massimino M., Stella S., Romano C., Manzella L. The Insulin/IGF System in Colorectal Cancer Development and Resistance to Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2015;5:230. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prevostel C., Rammah-Bouazza C., Trauchessec H., Canterel-Thouennon L., Busson M., Ychou M., Blache P. SOX9 is an atypical intestinal tumor suppressor controlling the oncogenic Wnt/ss-catenin signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82228–82243. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Randon G., Fucà G., Rossini D., Raimondi A., Pagani F., Perrone F., Tamborini E., Busico A., Peverelli G., Morano F. Prognostic impact of ATM mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2858. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39525-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolff R.K., Hoffman M.D., Wolff E.C., Herrick J.S., Sakoda L.C., Samowitz W.S., Slattery M.L. Mutation analysis of adenomas and carcinomas of the colon: Early and late drivers. Genes Chromosome Cancer. 2018;57:366–376. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li T., Yi L., Hai L., Ma H.W., Tao Z.N., Zhang C., Abeysekera I.R., Zhao K., Yang Y.H., Wang W., et al. The interactome and spatial redistribution feature of Ca2+ receptor protein calmodulin reveals a novel role in invadopodia-mediated invasion. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:292. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0253-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cruciat C.M., Niehrs C. Secreted and Transmembrane Wnt Inhibitors and Activators. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;3:a015081. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Furushima K., Yamamoto A., Nagano T., Shibata M., Miyachi H., Abe T., Ohshima N., Kiyonari H., Aizawa S. Mouse homologues of Shisa antagonistic to Wnt and Fgf signalings. Dev. Biol. 2007;306:480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong X., Liao W., Zhang L., Tu X., Hu J., Chen T., Dai X., Xiong Y., Liang W., Ding C., et al. RSPO2 suppresses colorectal cancer metastasis by counteracting the Wnt5a/Fzd7-driven noncanonical Wnt pathway. Cancer Lett. 2017;402:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi F., Cai F.F., Cai L., Lin X.Y., Zhang W., Wang Q.Q., Zhao Y.J., Ni Q.C., Wang H., He Z.X. Overexpression of SYF2 promotes cell proliferation and correlates with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:88453–88463. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abdelmaksoud-Damak R., Miladi-Abdennadher I., Triki M., Khabir A., Charfi S., Ayadi L., Frikha M., Sellami-Boudawara T., Mokdad-Gargouri R. Expression and mutation pattern of beta-catenin and adenomatous polyposis coli in colorectal cancer patients. Arch. Med. Res. 2015;46:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hasanpour M., Galehdari H., Masjedizadeh A., Ajami N. A unique profile of adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutations in Iranian patients suffering sporadic colorectal cancer. Cell J. 2014;16:17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Voorham Q.J., Carvalho B., Spiertz A.J., Claes B., Mongera S., van Grieken N.C., Grabsch H., Kliment M., Rembacken B., van de Wiel M.A., et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis in colorectal flat adenomas. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: A review of the evidence. J. Nutr. 2001;131:3109S–3120S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fukuda R., Hirota K., Fan F., Do Jung Y., Ellis L.M., Semenza G.L. Insulin-like growth factor 1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression, which is dependent on MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in colon cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38205–38211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McConnell B.B., Bialkowska A.B., Nandan M.O., Ghaleb A.M., Gordon F.J., Yang V.W. Haploinsufficiency of Kruppel-like factor 5 rescues the tumor-initiating effect of the Apc(Min) mutation in the intestine. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4125–4133. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwong L.N., Dove W.F. APC and Its Modifiers in Colon Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009;656:85–106. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1145-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nandan M.O., Ghaleb A.M., McConnell B.B., Patel N.V., Robine S., Yang V.W. Kruppel-like factor 5 is a crucial mediator of intestinal tumorigenesis in mice harboring combined ApcMin and KRASV12 mutations. Mol. Cancer. 2010;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sjoblom T., Jones S., Wood L.D., Parsons D.W., Lin J., Barber T.D., Mandelker D., Leary R.J., Ptak J., Silliman N., et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bruun J., Kolberg M., Nesland J.M., Svindland A., Nesbakken A., Lothe R.A. Prognostic Significance of beta-Catenin, E-Cadherin, and SOX9 in Colorectal Cancer: Results from a Large Population-Representative Series. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:118. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seshagiri S., Stawiski E.W., Durinck S., Modrusan Z., Storm E.E., Conboy C.B., Chaudhuri S., Guan Y.H., Janakiraman V., Jaiswal B.S., et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lu B., Fang Y., Xu J., Wang L., Xu F., Xu E., Huang Q., Lai M. Analysis of SOX9 expression in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008;130:897–904. doi: 10.1309/AJCPW1W8GJBQGCNI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matheu A., Collado M., Wise C., Manterola L., Cekaite L., Tye A.J., Canamero M., Bujanda L., Schedl A., Cheah K.S.E., et al. Oncogenicity of the Developmental Transcription Factor Sox9. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1301–1315. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhan T., Rindtorff N., Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–1473. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suleiman S.H., Koko M.E., Nasir W.H., Elfateh O., Elgizouli U.K., Abdallah M.O.E., Alfarouk K.O., Hussain A., Faisal S., Ibrahim F.M.A., et al. Exome sequencing of a colorectal cancer family reveals shared mutation pattern and predisposition circuitry along tumor pathways. Front. Genet. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fearnhead N.S., Wilding J.L., Bodmer W.F. Genetics of colorectal cancer: Hereditary aspects and overview of colorectal tumorigenesis. Br. Med. Bull. 2002;64:27–43. doi: 10.1093/bmb/64.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rusan N.M., Peifer M. Original CIN: Reviewing roles for APC in chromosome instability. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:719–726. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Druliner B.R., Wang P.W., Bae T., Baheti S., Slettedahl S., Mahoney D., Vasmatzis N., Xu H., Kim M., Bockol M., et al. Molecular characterization of colorectal adenomas with and without malignancy reveals distinguishing genome, transcriptome and methylome alterations. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3161. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boardinstitute Picard Tools by Broad Institute. [(accessed on 6 May 2016)]; Available online: www.broadinstitute.github.io/picard.

- 90.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cibulskis K., Lawrence M.S., Carter S.L., Sivachenko A., Jaffe D., Sougnez C., Gabriel S., Meyerson M., Lander E.S., Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McLaren W., Gil L., Hunt S.E., Riat H.S., Ritchie G.R., Thormann A., Flicek P., Cunningham F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sathirapongsasuti J.F., Lee H., Horst B.A., Brunner G., Cochran A.J., Binder S., Quackenbush J., Nelson S.F. Exome sequencing-based copy-number variation and loss of heterozygosity detection: ExomeCNV. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2648–2654. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ivakhno S., Tavare S. CNAnova: A new approach for finding recurrent copy number abnormalities in cancer SNP microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1395–1402. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kuleshov M.V., Jones M.R., Rouillard A.D., Fernandez N.F., Duan Q., Wang Z., Koplev S., Jenkins S.L., Jagodnik K.M., Lachmann A., et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen E.Y., Tan C.M., Kou Y., Duan Q., Wang Z., Meirelles G.V., Clark N.R., Ma’ayan A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.