Abstract

It is commonly accepted that the mechanical stimuli are important factors in the maintenance of normal structure and function of the articular cartilage. Despite extensive efforts, the cellular mechanisms underlying the responses of articular chondrocytes to mechanical stresses are not well understood. In the present review, different types of shear bioreactor and potential mechanisms that mediate and regulate the effect of shear on chondrocyte are discussed.

For this review, the search of the literature was done in the PubMed, Scopus, Web of sciences databases to identify papers reporting data about shear on chondrocyte. Keywords “shear, chondrocyte, cartilage, bioreactor” were used. Studies published until the first of March 2018 were considered in this paper. The review focused on the experimental studies conducted the effect of shear stress on cartilage tissue in vivo and in vitro. In this review, both experimental studies referring to human and animal tissues were taken into account. The following articles were excluded: reviews, meta-analysis, duplicate records, letters, and papers that did not add significant information. Mechanism of shear stress on chondrocyte, briefly can be hypothesized as (1) altered expression of aggrecan and collagen type II, (2) altered cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) serum levels, consequently, organizing the arrangement binding of glycosaminoglycans, integrins, and collagen, (3) induction of apoptosis signals, (4) altered expression of integrin.

Keywords: Shear, Bioreactors, Chondrocyte, Regeneration

Background

It is now commonly accepted that the mechanical stimuli are important factors in the maintenance of normal structure and function of the articular cartilage and changes its morphology in response to mechanical stimuli. Despite extensive efforts, the cellular mechanisms underlying the responses of articular chondrocytes to mechanical stresses are not well understood [1].

The mechanisms by which chondrocytes actively respond to mechanical stimuli are important for understanding the modulators and signaling pathways involved in the pathogenesis of major disabling diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) [2]. But, due to the complexity of the signaling mechanisms, the detailed pathways remain unclear.

Different mechanical stimuli such as compressive and tensile forces modulate chondrocyte function. Articular cartilage is the highly specialized hydrated (80% water) connective tissue that experiences the solute transport in the cartilage and movement of fluid during the loading and unloading conditions (exploding water during loading, and draw back into the tissue during unloading) [3].

By the movement of fluid within cartilage, chondrocytes experience potential fluid shear stress that affects chondrocytes proliferation, apoptosis, growth and differentiation, and extracellular matrix production [4]. A number of pathways involved in transduction of the mechanical stimuli of shear stress to intracellular signaling, but despite the extensive effort, exact mechanisms remain unclear. Thus, in the present review, different types of shear bioreactor and potential mechanisms that mediate and regulate chondrocyte proliferation and matrix production are discussed.

Main text

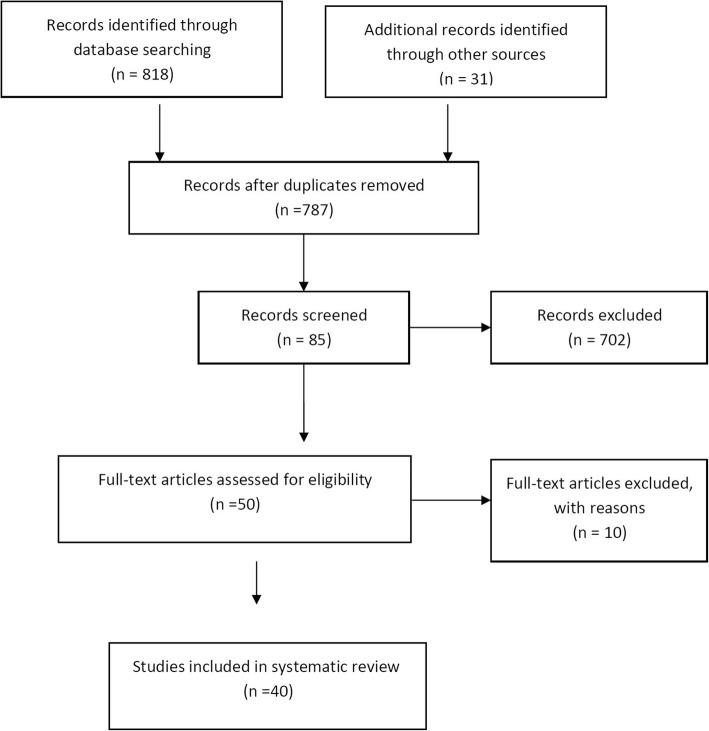

For this review, the search of the literature was done in the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Sciences databases to identify papers reporting data about the effect of shear stress on chondrocyte. Keywords “shear, chondrocyte, cartilage, bioreactor” were used. Studies published until the first of March 2018 were considered in this paper. The review focused on the experimental studies conducted shear stress on cartilage tissue in vivo and in vitro. In this review, both experimental studies referring to human and animal tissues were taken into account. The following articles were excluded: reviews, meta-analysis, duplicate records, letters, and papers that did not add significant information (Fig. 1). Data assessment was conducted independently by 2–6 investigators using predefined terms.

Fig 1.

Flow chart illustrating the number of investigations and studies included in the analysis

Cartilage

Articular cartilage as a highly specialized avascular, aneural, and alymphatic, connective tissue is composed largely of water, collagen, proteoglycans, and cells. The primary function of articular cartilage is to provide a smooth well-lubricated surface for synovial joint and to facilitate the transmission of loads. The composition and structure of articular cartilage have a direct role in its function as a lubricious, load-bearing tissue. To achieve a deep understanding of load-bearing properties, two major sets macromolecules, the proteoglycans, and collagens must first be well understood since structural interactions between these macromolecules resist compressive loads and retain water [5] (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Table 1.

| Water | Collagens | Proteoglycans | Other molecules | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 70–80(per ww) | 50–75(per dw) | 15–30(per dw) | |

| Property | Interstitial fluid | Collagen type II | Aggrecan, (hyaluronan + chondroitin and keratan sulfates | Fibronectin, cartilage oligomeric protein, thrombospondin, tenascin, matrix-GLA (glycine-leucine-alanine) protein, chondrocalcin, and superficial zone protein |

| Function | Transporting both nutrients and waste within the tissue |

Fibrillar and globular collagen types, such as types V, VI, IX, and XI Intermolecular interactions as well as modulating |

Comprised of a protein core with attached polysaccharide chains (glycosaminoglycans). |

Table 2.

Zonal structure of hyaline articular cartilage: from the articulating surface down to the subchondral bone [6, 7]

| Zone | % | Collagen | Collagen alignment | Shape of cell | Proteoglycan | Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The superficial (tangential) | 10–20 | Small diameter, densely packed collagen fibers | Parallel to the cartilage | Flattened, discoidal shapes | Low proteoglycan | Low permeability |

| The middle, or transitional | 40–60 | – | Arcade-like structure | Spherical in shape | Reaches its maximum | – |

| The deep zone/radial | 30% | Collagen large fibers | Perpendicular to the articular surface | Columnar organization. elongated | Proteoglycan much lower than in the middle zone | “Tidemark” |

| The calcified zone | – | – | – | – | – | transitions into the subchondral bone |

Table 3.

Territorial Structure of hyaline articular cartilage [8]

| Location | Collagen fibers | Proteoglycans | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Pericellular matrix chondron |

Type II, VI, and IX concentrated in the pericellular network of thin fibrils as fibronectin. | Mainly proteoglycans as aggrecan, hyaluronan and decorin, glycoproteins, and other non-collagenous proteins | Functional role to initiate signal transduction within cartilage with load bearing |

| 2 |

(The territorial matrix) This region is thicker than the pericellular matrix |

Fine collagen fibrils, forming a basketlike network around the cells Type VI collagen microfibrils but little or no fibrillar collagen. |

High concentrations | May protect the cartilage cells against mechanical stresses and may contribute to the resiliency of the articular cartilage structure and its ability to withstand a substantial load |

|

The interterritorial matrix largest of the 3 matrix regions; it contributes most to the biomechanical properties of articular cartilage |

Large collagen type IV fibers Randomly oriented bundles of large collagen fibrils, as zonal structure collagen type II, type XI collagen and type IX collagen |

Are abundant |

Bulk of articular cartilage permitting association with other matrix components and retention of proteoglycans. These collagens give to the cartilage form, tensile stiffness, and strength |

Table 4.

Properties of articular cartilage chondrocyte

| Chondrocyte | |

|---|---|

| Role | Development, maintenance, and repair of the extracellular matrix (ECM). |

| Origin | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| Volume | 2% of the total volume of articular cartilage. |

| Shape, number, and size | Vary in shape, number, and size, depending on the anatomical regions of the articular cartilage. |

| Respond to stimuli | Respond to a variety of mechanical stimuli and growth factors |

| Replication | Detectable cell division, limited potential for replication |

| Synthesis matrix | Responsible for both the synthesis and the breakdown of the cartilaginous matrix. |

| Differentiation | Highly differentiated cell, highly specialized, metabolically active cells |

| Adaption by low oxygen | Well adapted by low oxygen consumption to conditions |

Zonal structure of hyaline articular cartilage from the articulating surface down to the subchondral bone is shown in Table 2. Territorial structure of hyaline articular cartilage is shown in Table 3.

Chondrocyte

Within the cartilage matrix, the chondrocyte is the only responsible cell type for synthesis extracellular matrix and constitute about 2% of the total volume of articular cartilage.

Effect of mechanical stimuli on chondrocyte

Interactions between chondrocytes and the ECM, consequently, homeostasis maintenance of the articular cartilage modulated by several stimuli such as mechanical stress, soluble mediators, and matrix composition. Mechanical stimuli affecting chondrocytes are divided into four categories (dynamic compression, fluid shear, tissue shear, and hydrostatic). Here, we focused on the effect of shear stress on chondrocyte metabolism. Also, four general categories of shear bioreactors are discussed [9, 10].

Effect of shear stress on chondrocyte metabolism

As mentioned above, cartilage is a highly hydrated connective tissue. Approximately, 70% of water is expelled when the tissue is loaded in compression resulting in potential fluid shear stress at or near the cellular membrane. The water was osmotically drawn back when the tissue is unloaded [11–13]. Therefore, chondrocyte can experience fluid shear stress when water is relocated during compression [14].

Shear stress as a mechanical stimulation has been shown to affect chondrocytes through changes in membrane potential, solute transport, or cellular deformation. It is hypothesized that articular chondrocyte metabolism is modulated by direct effects of shear forces that act on the cell through mechanotransduction processes and the properties of the cross-linked type II collagen fibrils.

Experimental studies with shear stress

Four general categories of shear bioreactors have been carried out including contact shear, fluid flow, direct fluid perfusion, and low shear “microgravity” bioreactors (Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8)

Table 5.

Effect of experimental contact shear on chondrocyte proliferation and matrix composition

| Hz | % strain | Cell proliferation | Collagen | GAG | Proteoglycan | Scaffold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | 1 | 2 | Chondrocyte | 40% increase | Not measured | 25% increase | (Cpp) calcium poly phosphate |

| [16] | 0.01 | 0.4–1.6 | Chondrocyte | 40% increase | Not measured | 25% increase | Cartilage disk |

| [17] | 0.1 | 0.5–6 | Chondrocyte | 30–35% increase | Not measured | 20–25% increase | Cartilage explant |

| [18] | 0.0.1 | 1–3 | Chondrocyte | 50% increase | Not measured | 25% increase | Cartilage explant |

| [19] | 0.05–0.5 | – | Chondrocyte | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | Bovine nasal cartilage |

| [20] | 1 | – | Chondrocyte | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | Agarose |

| [21] | 1 | 2.5% | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Agarose gels |

| [22] | 0.1 | 3 | Chondrocyte | 30–100% increase | Increase | 100–200% increase | Cartilage explant disks |

| [23] | 0.5 | – | Chondrocyte | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | No scaffolds |

| [24] | 0.05 | – | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Not measured | No scaffolds |

| [25] | 0.5 | 10–20% | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Fibrin-polyurethane |

Table 6.

Experimental fluid shear by different bioreactor and scaffolds and effects on chondrocyte proliferation and matrix composition

| RPM | Scaffold | Cell proliferation | Collagen | GAG | Proteoglycan | Type for bioreactor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | 80 | PGA | Chondrocyte | Increase 80% | Increase | Not measured | Spinner flask |

| [27] | 50 | PGA | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Spinner flask |

| [28] | 50 | No scaffolds | Chondrocyte | Increase 125% | Increase 60% | Not measured | Spinner flask |

| [29] | 90 | osteochondral tissue | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Spinner bioreactor |

| [30] | 50–140 | No scaffolds | No cell | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | Wavy-walled bioreactor |

| [31] | – | chitosan/gelatin | Adipose-derived stem cells | Increase | Increase | Increase | Spinner flask |

| [32] | – | No scaffolds | Chondrocyte | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | 3D finite element model |

| [33] | – | No scaffolds | No cell | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | Hollow fiber (mathematical modeling) |

| [24] | – | No scaffolds | Chondroprogenitor cells | Increase | Increase | Increase | Model |

| [34] | – | No scaffolds | No cell | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | Hollow fiber (mathematical modeling) |

Table 7.

Effect of perfusion bioreactor on chondrocyte proliferation and matrix composition

| Pa | Rate | Cell proliferation | Collagen | GAG | Proteoglycan | Scaffold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | – | 0.33 ml/min | Chondrocyte | Collagen2 increase 240% | 300% (S)180% (NS) | Increase 35% aggrecan | Collagen sponges |

| [36] | – | 1 μm/s | Chondrocyte | 155% increase | Increase 184% | Increase 118% | PLLA/PGA |

| [37] | 0.01 | – | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Micro-porous scaffolds |

| [38] | 0.01 | 0.5 ml/min | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Polyestherurethane foams |

| [39] | 0.1. | 2 ml/min | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Explant |

| [40] | – | 0.1 ml/min | Human mesenchymal stem cells | Increase | Increase | Increase | Polycaprolactone (PCL) beads |

| [41] | – | 3 ml/min | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Alginate |

| [42] | – | 0.33 ml/min | Chondrocyte | – | Increase | Increase | Electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone |

| [43] | – | 1000, 300 μm/s | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Collagen sponges |

| [44] | 0.05–0.45 | 0.005–0.045 ml/min | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Polyurethane |

| [45] | – | 10 μm/s | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | No scaffolds |

Table 8.

Effect of perfusion bioreactor with low shear on chondrocyte proliferation and matrix composition

| Pa | RPM | Rate | Cell proliferation | Collagen | GAG | Proteoglycan | Scaffold | Bioreactor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46–49] | 1.10 | – | 0.5–2 | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Alginate | Perfusion |

| [50] | – | 15–30 | – | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Hyaluronan benzyl ester non-woven | Rotating |

| [51] | – | – | – | No cell | Increase 33% | Increase 68% | Not measured | No scaffolds | Rotating |

| [52] | – | – | – | Chondrocyte | Increase 39% | increase 95% | – | No scaffolds | - |

| [53] | 17 kPa | 1.32 ml h−1 | Chondrocyte | Increase | Increase | Increase | Scaffold-free | acoustofluidic perfusion |

Contact shear

During the physiological situation, cartilage is rubbing against either cartilage or produce contact shear. Several studies attempted to stimulate the solid-on-solid, contact shear using bioreactors and different scaffold (Table 5). The results of Waldman et al. study demonstrated that intermittent application of dynamic shearing forces (2% shear strain amplitude at a frequency of 1 Hz) increased both collagen and proteoglycan synthesis and improves the quality of cartilaginous tissue [15]. Also, in the study of Frank et al. through metabolic studies and application of sinusoidal macroscopic shear deformation (rotational resolution is 0.0005°), increase in the synthesis of proteoglycan and proteins was detected [16]. Several studies examined the tissue shear loading (0.01–1.0 Hz, using 1–3% sinusoidal shear strain amplitudes) on chondrocyte biosynthesis and revealed that the synthesis of protein by approximately 50% and proteoglycans by approximately 25% increased [17, 18]. Colombo t al. developed and validated a multi-axial device named RPETS with sinusoidal motion frequency between 0.05 and 0.5 Hz [19]. Also, Di Federico et al. described an in vitro mechanical system to chondrocyte-seeded agarose constructs (compressive and shear loading regimen at 1 Hz for up to 48 h) to investigate the response of chondrocytes to a complex physiologically relevant deformation profile [20]. In the study of Chai et al., bovine articular chondrocytes were seeded in 2% agarose gels subjected to a 24-h dynamic compression regime (1 Hz, 2.5% dynamic strain amplitude, 7% static offset strain) that increased proteoglycan synthesis and total glycosaminoglycans (GAG) accumulation [21]. In a similar study, Fitzgerald et al. subjected intact cartilage explants to 1–24 h of continuous dynamic compression or dynamic shear loading at 0.1 Hz. Results showed that most matrix proteins were upregulated by 24 h of dynamic compression or dynamic shear [22]. Malaeb et al. built a four-chamber bioreactor to apply hydrostatic pressure, compression, shear, and torsion (frequency of 0.5 Hz). Results showed that the system was capable of delivering a variety of mechanical stimuli in native cartilage [23]. In a study, Juhasz et al. investigated the loading scheme (0.05 Hz, 600 Pa; for 30 min) on chondroprogenitor cells of 4-day-old chicken embryos. The results showed that several cartilage matrix constituents, including collagen type II and aggrecan core protein, as well as matrix-producing hyaluronan synthases increased [24]. Also, Vainieri et al. developed a model of osteochondral defect from bovine stifle joints using bioreactor that mimics the multi-axial motion of an articulating joint. Results revealed that proteoglycan 4 and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, mRNA ratios of collagen type II to type I, and aggrecan to versican were markedly improved [25].

Fluid shear

Fluid flow bioreactor development is consistent with the hypothesis that increase in nutrient and wastes transfer lead to increase in cell metabolism. Several bioreactors including spinner flask and wavy-walled bioreactor developed for the purpose (Table 6).

Gooch et al. investigated the effects of the hydrodynamic environment by using spinner flask (80 RPM) on bovine calf chondrocytes seeded on polyglycolic acid meshes. The finding of the study was higher fractions of collagen and more GAG in chondrocytes [26]. Also, Bueno et al. developed a wavy-walled bioreactor to provide high-axial mixing environment to the cultivation of cartilage constructs. Polyglycolic acid scaffolds seeded with bovine articular chondrocytes and resulted increased cell proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition [27]

Vunjak-Novakovic et al. investigated the effect of bovine articular chondrocytes seeded in fibrous polyglycolic acid in well-mixed spinner flasks. This environment resulted in the formation of 20–32-micron diameter cell aggregates that enhanced the kinetics of cell attachment [28]. In a similar study, Theodoropoulos et al. placed articular cartilage of bovine metacarpal-phalangeal joints in spinner bioreactors and maintained on a magnetic stir plate at 90 rotations per minute (RPM). The study found that there was a significant increase in collagen content, the expression of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), and aggrecan [29]. Study of Bilgen et al. that applied a wavy-walled bioreactor (WWB) demonstrated the importance of characterization of mixing and impact of changes in bioreactor geometry and operating conditions [30]. In the study of Song et al. in a spinner flask, adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) seeded with chitosan/gelatin hybrid hydrogel scaffolds. ADSCs differentiated into chondrocytes and expressed more proteoglycans and cell distribution [31]. In another study, Cortez et al. developed a 3D finite element model to mechanical simulate (5%, 10%, and 15% of compressive strain with frequencies of 0.5 Hz, 1 Hz, and 2 Hz) the diffusion and transport of nutrients. The findings showed that fluid shear stress improved the solute transport and chondrocyte activity [32]. Also, Chapman et al. applied a model to predict the optimal flow rate of culture medium into the fiber lumen [33]. Juhasz et al. in a study investigated the loading scheme (0.05 Hz, 600 Pa; for 30 min) on chondroprogenitor cells and showed an increase in cartilage matrix constituents of chicken embryos, including collagen type II and aggrecan core protein, as well as matrix-producing hyaluronan synthases [24]. Also, Pearson et al. applied a model of fluid flow, nutrient transport, and cell distribution using a hollow fiber membrane bioreactor. With the model and the effect of mechanotransduction on the distribution investigated [34].

Perfusion bioreactor

Transfer nutrient through the three-dimensional biomaterial and tissue constructs is one of the serious problem and limitations of fluid shear bioreactors. Therefore, direct perfusion bioreactor with different flow rates investigated and developed to overcome the nutrient limitations (Table 7). Mizuno et al. in a study cultured bovine articular chondrocytes in 3D collagen sponges with medium perfusion (0.33 mL/min) for up to 15 days. Interestingly, the results demonstrated that these conditions that are beneficial for other cell types inhibit chondrogenesis by articular chondrocytes [35]. Pazzano et al. cultured chondrocytes seeded on PLLA/PGA under to 1 μm/s flow and demonstrated a 118% increase in DNA content, a 184% increase in GAG content, and a 155% increase in hydroxyproline content [36]. Also, culture of bovine articular chondrocytes seeded on micro-porous scaffolds under a median shear stress of 1.2 and 6.7 mPa, promoted the formation of extra-cellular matrix specific to hyaline cartilage [37]. In another study, bovine articular chondrocytes seeded on polyesterurethane foams and cultured for 2 weeks under flow rate (0.5 ml/min). The results of study indicated that mean content in DNA and GAG increased [38]. In a similar study, the culture of human chondrocytes in bioreactor applied loading (0.1 MPa for 2 h) and perfusion (2 ml) led to increase of COL2A1 expression and decrease of COL1A1 and MMP-13 expression [39]. Carmona-Moran and Wick applied perfusion bioreactor to promote chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Results of this culture condition showed that after day 14, collagen deposition and proteoglycan deposition increased [40]. Yu et al. developed the tubular perfusion system (TPS) and cultured chondrocytes encapsulated in alginate for 14 days and demonstrated that 3 mL/min does not damage the chondrocytes. This culture condition resulted in increased gene expression levels of aggrecan, type II collagen, and superficial zone protein [41]. In a similar study, Dahlin et al. cultured chondrocytes seeded onto electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) under perfusion condition and demonstrated an increase in chondrocyte proliferation and glycosaminoglycan production [42]. Mayer et al. cultured human articular chondrocytes seeded in collagen sponges with a bidirectional perfusion bioreactor. Results indicated that perfusion bioreactor and cocktail of soluble factors, the BIT (BMP-2, insulin, thyroxin) improved the distribution and quality of cartilaginous matrix [43]. Raimondi et al. investigated the effects of three different perfusion flow rates and shear stress levels (0.005, 0.023 ml/min and 0.045 ml/min) to chondrocytes detachment from cellularized constructs. Results indicated the number of detached cells increased [44]. Also, the finding of Tonnarelli et al. study indicated that culture of chondrocytes bioreactor culture conditions support chondrogenic differentiation [45].

Low shear bioreactor

Low shear mixing improves the growth of cells on three-dimensional scaffolds and applies minimal loading to constructs. Rotating bioreactors are the most popular devices to apply low shear mixing (Table 8). Several studies investigated the effect of flow-induced shear stress by perfusion bioreactor on alginate encapsulating chondrocytes. Tissue construct subjected to shear showed morphological features, which are characteristic of natural cartilage [46–49]. Also, Tognana et al. examined the culture of bovine calf chondrocytes and hyaluronan benzyl ester non-woven mesh under perfusion bioreactor. Results indicated that this culture condition improved chondrogenesis and integrative repair in engineered cartilage [50]. In a similar study, Tsao et al. developed a mathematical model to characterize cell-medium interactions and demonstrated that experimental results support the numerical simulation [51]. The finding of Martin et al.’s study indicated that composition and mechanical properties of engineered cartilage (highest fractions of glycosaminoglycans and collagen) can be modulated by the culture conditions [52]. Li et al developed acoustofluidic perfusion bioreactors to overcome the limitations of conventional static cartilage bioengineering [53].

Conclusion

In the field of tissue engineering, several bioreactors developed at once and at different times to apply mechanical forces to cartilage constructs. Mechanism of shear stress on chondrocyte, briefly, can be hypothesized as the following [24, 29, 35, 41]:

Altered expression of aggrecan and collagen type II

Altered cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) serum levels, consequently, organizing the arrangement binding of glycosaminoglycans, integrins, and collagen

Induction of apoptosis signals

Altered expression of integrin.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to acknowledge them.

Authors’ contributions

NS and AMG involved in the literature review, creation of the manuscript and editing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dowling EP, Ronan W, Ofek G, Deshpande VS, McMeeking RM, Athanasiou KA, et al. The effect of remodelling and contractility of the actin cytoskeleton on the shear resistance of single cells: a computational and experimental investigation. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(77):3469–3479. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pingguan-Murphy B, El-Azzeh M, Bader D, Knight M. Cyclic compression of chondrocytes modulates a purinergic calcium signalling pathway in a strain rate-and frequency-dependent manner. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(2):389–397. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denison TA. The effect of fluid shear stress on growth plate chondrocytes. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh C-C, Chang S-F, Huang T-Y, Chang H-I, Kuo H-C, Wu Y-C, et al. Shear stress modulates macrophage-induced urokinase plasminogen activator expression in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R53. doi: 10.1186/ar4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palukuru Uday P., McGoverin Cushla M., Pleshko Nancy. Assessment of hyaline cartilage matrix composition using near infrared spectroscopy. Matrix Biology. 2014;38:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sophia Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health. 2009;1(6):461–468. doi: 10.1177/1941738109350438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poole A. Robin, Kojima Toshi, Yasuda Tadashi, Mwale Fackson, Kobayashi Masahiko, Laverty Sheila. Composition and Structure of Articular Cartilage. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2001;391:S26–S33. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koay E, Athanasiou K. Articular cartilage biomechanics, mechanobiology, and tissue engineering. Biomechanical Systems Technology: Muscular Skeletal Systems 2009. p. 1-37.

- 9.Kamiya T, Tanimoto K, Tanne Y, Lin YY, Kunimatsu R, Yoshioka M, et al. Effects of mechanical stimuli on the synthesis of superficial zone protein in chondrocytes. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2010;92(2):801–805. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YH, Barabino GA. Environmental factors in cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue and Organ Regeneration: Advances in Micro- and Nanotechnology 2014. p. 408-54.

- 11.Lane Smith R, Trindade MCD, Ikenoue T, Mohtai M, Das P, Carter DR, et al. Effects of shear stress on articular chondrocyte metabolism. Biorheology. 2000;37(1-2):95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malaviya P, Nerem RM. Fluid-induced shear stress stimulates chondrocyte proliferation partially mediated via TGF-β1. Tissue Eng. 2002;8(4):581–590. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RL, Donlon BS, Gupta MK, Mohtai M, Das P, Carter DR, et al. Effects of fluid-induced shear on articular chondrocyte morphology and metabolism in vitro. J Orthop Res. 1995;13(6):824–831. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang ML, Peng ZX. Wear in human knees. Biosurf Biotribol. 2015;1(2):98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bsbt.2015.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldman SD, Spiteri CG, Grynpas MD, Pilliar RM, Kandel RA. Long-term intermittent shear deformation improves the quality of cartilaginous tissue formed in vitro. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(4):590–596. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank EH, Jin M, Loening AM, Levenston ME, Grodzinsky AJ. A versatile shear and compression apparatus for mechanical stimulation of tissue culture explants. J Biomech. 2000;33(11):1523–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin M, Emkey GR, Siparsky P, Trippel SB, Grodzinsky AJ. Combined effects of dynamic tissue shear deformation and insulin-like growth factor I on chondrocyte biosynthesis in cartilage explants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;414(2):223–231. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin M, Frank EH, Quinn TM, Hunziker EB, Grodzinsky AJ. Tissue shear deformation stimulates proteoglycan and protein biosynthesis in bovine cartilage explants. Arch Biochemi Biophys. 2001;395(1):41–48. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombo V, Correro MR, Riener R, Weber FE, Gallo LM. Design, construction and validation of a computer controlled system for functional loading of soft tissue. Med Eng Phys. 2011;33(6):677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Federico E, Bader DL, Shelton JC. Design and validation of an in vitro loading system for the combined application of cyclic compression and shear to 3D chondrocytes-seeded agarose constructs. Med Eng Phys. 2014;36(4):534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chai DH, Arner EC, Griggs DW, Grodzinsky AJ. αv and β1 integrins regulate dynamic compression-induced proteoglycan synthesis in 3D gel culture by distinct complementary pathways. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(2):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald JB, Jin M, Grodzinsky AJ. Shear and compression differentially regulate clusters of functionally related temporal transcription patterns in cartilage tissue. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(34):24095–24103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malaeb W, Mhanna R, Hamade R, editors. Multi-variant bioreactor for cartilage tissue engineering. Middle East Conference on Biomedical Engineering, MECBME; 2016.

- 24.Juhász T, Matta C, Somogyi C, Katona É, Takács R, Soha RF, et al. Mechanical loading stimulates chondrogenesis via the PKA/CREB-Sox9 and PP2A pathways in chicken micromass cultures. Cell Signal. 2014;26(3):468–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vainieri ML, Wahl D, Alini M, van Osch GJVM, Grad S. Mechanically stimulated osteochondral organ culture for evaluation of biomaterials in cartilage repair studies. Acta Biomater. 2018;81:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gooch KJ, Kwon JH, Blunk T, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Effects of mixing intensity on tissue-engineered cartilage. Biotechnolo Bioeng. 2001;72(4):402–407. doi: 10.1002/1097-0290(20000220)72:4<402::AID-BIT1002>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bueno EM, Bilgen B, Barabino GA. Wavy-walled bioreactor supports increased cell proliferation and matrix deposition in engineered cartilage constructs. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(11-12):1699–1709. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vunjak-Novakovic G, Obradovic B, Martin I, Bursac PM, Langer R, Freed LE. Dynamic cell seeding of polymer scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Progress. 1998;14(2):193–202. doi: 10.1021/bp970120j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theodoropoulos John S., DeCroos Amritha J. N., Petrera Massimo, Park Sam, Kandel Rita A. Mechanical stimulation enhances integration in an in vitro model of cartilage repair. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2014;24(6):2055–2064. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilgen B, Chang-Mateu IM, Barabino GA. Characterization of mixing in a novel wavy-walled bioreactor for tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92(7):907–919. doi: 10.1002/bit.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song K, Li L, Li W, Zhu Y, Jiao Z, Lim M, et al. Three-dimensional dynamic fabrication of engineered cartilage based on chitosan/gelatin hybrid hydrogel scaffold in a spinner flask with a special designed steel frame. Mat Sci Eng. 2015;55:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cortez S, Completo A, Alves JL, editors. The influence of mechanical stimulus on nutrient transport and cell growth in engineered cartilage: a finite element approach. ECCOMAS Congress 2016 - Proceedings of the 7th European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering; 2016.

- 33.Chapman LAC, Whiteley JP, Byrne HM, Waters SL, Shipley RJ. Mathematical modelling of cell layer growth in a hollow fibre bioreactor. J Theor Biol. 2017;418:36–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson NC, Waters SL, Oliver JM, Shipley RJ. Multiphase modelling of the effect of fluid shear stress on cell yield and distribution in a hollow fibre membrane bioreactor. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14(2):387–402. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno S, Allemann F, Glowacki J. Effects of medium perfusion on matrix production by bovine chondrocytes in three-dimensional collagen sponges. J Biomed Mat Res. 2001;56(3):368–375. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010905)56:3<368::AID-JBM1105>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pazzano D, Mercier KA, Moran JM, Fong SS, DiBiasio DD, Rulfs JX, et al. Comparison of chondrogensis in static and perfused bioreactor culture. Biotechnol Progress. 2000;16(5):893–896. doi: 10.1021/bp000082v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raimondi MT, Candiani G, Cabras M, Cioffi M, Laganà K, Moretti M, et al. Engineered cartilage constructs subject to very low regimens of interstitial perfusion. Biorheology. 2008;45(3-4):471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raimondi MT, Moretti M, Cioffi M, Giordano C, Boschetti F, Laganà K, et al. The effect of hydrodynamic shear on 3D engineered chondrocyte systems subject to direct perfusion. Biorheology. 2006;43(3-4):215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu G, Mayer-Wagner S, Schröder C, Woiczinski M, Blum H, Lavagi I, et al. Comparing effects of perfusion and hydrostatic pressure on gene profiles of human chondrocyte. J Biotechnol. 2015;210:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.06.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carmona-Moran CA, Wick TM. Transient Growth Factor Stimulation Improves Chondrogenesis in Static Culture and Under Dynamic Conditions in a Novel Shear and Perfusion Bioreactor. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2015;8(2):267–277. doi: 10.1007/s12195-015-0387-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu L, Ferlin KM, Nguyen B-NB, Fisher JP. Tubular perfusion system for chondrocyte culture and superficial zone protein expression. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2015;103(5):1864–1874. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahlin RL, Meretoja VV, Ni M, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Hypoxia and flow perfusion modulate proliferation and gene expression of articular chondrocytes on porous scaffolds. AIChE J. 2013;59(9):3158–3166. doi: 10.1002/aic.13958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayer Nathalie, Lopa Silvia, Talò Giuseppe, Lovati Arianna B., Pasdeloup Marielle, Riboldi Stefania A., Moretti Matteo, Mallein-Gerin Frédéric. Interstitial Perfusion Culture with Specific Soluble Factors Inhibits Type I Collagen Production from Human Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes in Clinical-Grade Collagen Sponges. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0161479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raimondi MT, Bertoldi S, Caddeo S, Farè S, Arrigoni C, Moretti M. The effect of polyurethane scaffold surface treatments on the adhesion of chondrocytes subjected to interstitial perfusion culture. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;13(4):364–374. doi: 10.1007/s13770-016-9047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tonnarelli B, Santoro R, Asnaghi MA, Wendt D. Streamlined bioreactor-based production of human cartilage tissues. Eur Cell Mat. 2016;31:382–394. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v031a24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gharravi AM, Orazizadeh M, Ansari-Asl K, Banoni S, Izadi S, Hashemitabar M. Design and fabrication of anatomical bioreactor systems containing alginate scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2012;4(2):65–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gharravi AM, Orazizadeh M, Hashemitabar M. Direct expansion of chondrocytes in a dynamic three-dimensional culture system: Overcoming dedifferentiation effects in monolayer culture. Artificial Organs. 2014;38(12):1053–1058. doi: 10.1111/aor.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gharravi AM, Orazizadeh M, Hashemitabar M. Fluid-induced low shear stress improves cartilage like tissue fabrication by encapsulating chondrocytes. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17(1):117–122. doi: 10.1007/s10561-015-9529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gharravi AM, Orazizadeh M, Hashemitabar M, Ansari-Asl K, Banoni S, Alifard A, et al. Design and validation of perfusion bioreactor with low shear stress for tissue engineering. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33(2):185–192. doi: 10.5405/jmbe.1075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tognana E, Chen F, Padera RF, Leddy HA, Christensen SE, Guilak F, et al. Adjacent tissues (cartilage, bone) affect the functional integration of engineered calf cartilage in vitro. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2005;13(2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsao Y-MD, Boyd E, Wolf DA, Spaulding G. Fluid dynamics within a rotating bioreactor in space and Earth environments. J Spacecraft Rockets. 1994;31(6):937–943. doi: 10.2514/3.26541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin I, Obradovic B, Treppo S, Grodzinsky AJ, Langer R, Freed LE, et al. Modulation of the mechanical properties of tissue engineered cartilage. Biorheology. 2000;37(1-2):141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li S, Glynne-Jones P, Andriotis OG, Ching KY, Jonnalagadda US, Oreffo ROC, et al. Application of an acoustofluidic perfusion bioreactor for cartilage tissue engineering. Lab Chip. 2014;14(23):4475–4485. doi: 10.1039/C4LC00956H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]