Abstract

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) often fold into stable structures upon specific binding. The roles of residual structure of unbound IDPs in coupling binding and folding have been under much debate. While many studies emphasize the importance of conformational flexibility for IDP recognition, it was recently demonstrated that stabilization the N-terminal helix of intrinsically disordered ACTR accelerated its binding to another IDP, NCBD of the CREB-binding protein. To understand how enhancing ACTR helicity accelerates binding, we derived a series of topology-based coarse-grained models that mimicked various ACTR mutants with increasing helical contents and reproduced their NCBD binding affinities. Molecular dynamics simulations were then performed to sample hundreds of reversible coupled binding and folding transitions. The results show that increasing ACTR helicity does not alter the baseline mechanism of synergistic folding, which continues to follow “extended conformational selection” with multiple stages of selection and induced folding. Importantly, these coarse-grained models, while only calibrated based on binding thermodynamics, recapitulate the observed kinetic acceleration with increasing ACTR helicity. However, the residual helices do not enhance the association kinetics via more efficient seeding of productive collisions. Instead, they allow the nonspecific collision complexes to evolve more efficiently into the final bound and folded state, which is the primary source of accelerated association kinetics. Meanwhile, reduced dissociation kinetics with increasing ACTR helicity can be directly attributed to smaller entropic cost of forming the bound state. Altogether, this study provides important mechanistic insights into how residual structure may modulate thermodynamics and kinetics of IDP interactions.

Keywords: binding kinetics, conformational selection, coupled binding and folding, molecular dynamics, topology-based modeling

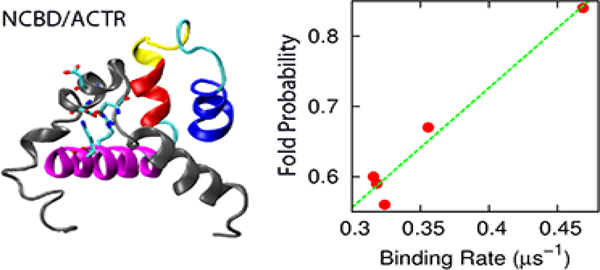

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Unlike well-folded proteins, intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) lack stable 3D structures in the unbound state under physiological conditions[1–9]. They play important roles in cellular protein-protein interaction networks and are capable of interacting with many targets with specificity[3–5, 10–13]. Upon specific binding, IDPs often gain stable secondary and/or tertiary structures[11, 14, 15]. The molecular mechanism of how IDPs achieve efficient coupled binding and folding has been under intensive studies[15–23]. In particular, the unbound states of IDPs often contain residual structure that resembles those in the bound state[6, 7, 11, 23–26], even though the roles of such residual structure in IDP recognition remain debatable. On one hand, residual structure may serve as initial contact points that facilitate productive binding and folding, referred to as conformational selection-like mechanisms[25]. On the other hand, conformational flexibility has been argued to be crucial for binding, and increasing the level of residual structure may reduce the association kinetics[27–29]. Instead, it has been argued that rapid folding upon encounter is critical for IDPs to achieve facile specific recognition[30, 31]. The dual-transition-state theory[32] predicts that the diffusion-limited encounter rate represents an upper-limit for that of IDP coupled binding and folding, which cannot be achieved unless IDPs fold rapidly upon encounter (i.e., beyond the typical speed limit of μs−1 for isolated proteins[33]). If only collisions with conformers with preformed, native-like structures could lead to productive formation of the bound state (i.e., conformational selection-like mechanisms), the overall association kinetics of the coupled binding and folding process would be reduced, at least by the relative population of these pre-folded states. Curiously, it has been observed that IDPs have similar association rates compared to folded proteins[34, 35]. The implication is that IDPs could fold efficiently upon encounter in general. Several features of IDPs have been argued to contribute to efficient folding upon encounter, such as small interacting domains, simple folded topologies with low contact orders, and likely an appropriate balance between residual structure and conformational flexibility[7].

In a recent NMR and stopped-flow kinetic study, Kjaergaard and coworkers examined the effects of stabilizing residual helices on the association of activation domain of the activator for thyroid hormone and retinoid receptors (ACTR) with the nuclear coactivator binding domain (NCBD) of CREB-binding protein[36] (Figure 1). Eight ACTR mutants were designed with varying helical propensities in the N-terminal helix (H1), without perturbing its electrostatic properties or inter-molecular interactions. Intriguingly, increased helicity of ACTR H1 was observed to accelerate the rate of association with NCBD and at the same time decelerate the dissociation rate, leading to a net stabilization of the complex. Such accelerated association induced by increasing residual helicity has also been reported for the association of KIX with c-Myb[37, 38] and assembly of the spectrin tetramerization domain[39]. Yet, this observation is in contrast to several previous studies where the association rates are either reduced (e.g., in p27Kip1/cyclin A/Cdk2[27] and pKID/KIX[28] interactions) or remain similar (e.g., PUMA binding to MCL-1[18]) with increasing residual helicity. Mechanistically how stabilized residual helices modulate the interaction kinetics and mechanism is not clear. While the association rate constant of an ideal conformational selection process depends linearly on the pre-folded population, how residual structure could modulate an induced-folding process is not clear. As discussed in the previous work [36], one plausible explanation is that the rate-limiting folding step occurs after an initial binding step, and the energy barrier decreases with increased helical content[36]. Another interpretation could be the existence of several parallel pathways, and increasing helical population may significantly increase the flux of conformational selection like pathways (rather than lower the barrier height)[36].

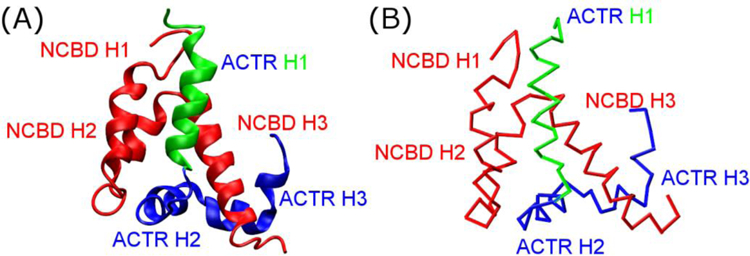

Figure 1.

(A) Structure of the NCBD/ACTR complex (PDB 1KBH[60]) and (B) the Cα-only Gō-like model.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations could provide microscopic details necessary for unveiling the molecular mechanisms of complex coupled binding and folding processes, which often involve multiple intermediate states and parallel pathways[21–23, 28, 31, 40, 41]. However, atomistic simulations using physics-based force fields remain computationally too expensive to sample reversible binding and folding transitions to obtain reliable and statistically meaningful observations on mechanism[7]. Instead, topology-based coarse-grained (CG) modeling has been shown to offer an effective tool for mechanistic studies of coupled binding and folding of IDPs into stable complexes [28, 40, 42], which arguably is also governed by the minimal frustration principle of protein folding[43]. With proper calibration to balance the interplay of residual folding and intermolecular interactions, these Gō-like models have been successfully applied to several IDP complexes, and many predictions have been substantiated by independent experiments [22, 28, 30, 44–46]. In this work, we first derive a series of Gō-like CG models that are carefully calibrated to mimic ACTR mutants with various residual helical contents and reproduce their NCBD binding affinities. Milliseconds of MD simulations were then performed to sample hundreds of reversible coupled binding and folding transitions to analyze the association kinetics and mechanism. The results show that these Gō-like models, while only calibrated based on binding thermodynamics, recapitulate the observed kinetic acceleration with increasing ACTR helicity. Mechanistic analyses reveal that pre-existing structures in ACTR do not significantly alter the baseline mechanism of its synergistic folding upon binding to NCBD. Instead, they accelerate the overall association kinetics mainly by promoting more efficient folding upon encounter.

Results and Discussion

Gō-like models recapitulate higher NCBD/ACTR affinity with stabilized ACTR H1

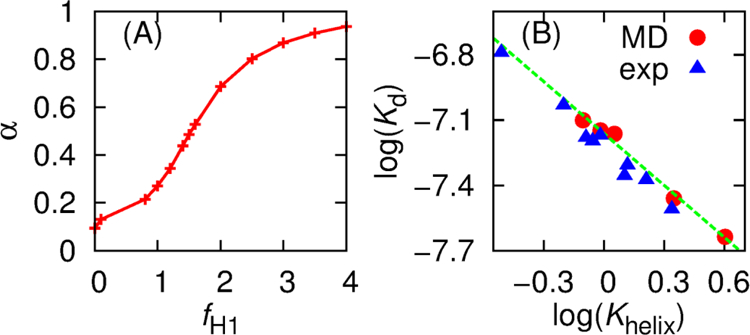

As summarized in Figure 2A and Table 1, scaling of the intra-molecular interaction strengths of ACTR H1 allows direct modulation of its average helicity. The average helicity is bound between 10% to 95% due to the coarse-grained nature of Gō-like model. However, the resulting models overestimate how much NCBD/ACTR is stabilized by increasing ACTR H1 helicity, probably because these models under-estimate the entropic cost of binding-induced folding. To capture the binding affinities of ACTR to NCBD measured experimentally[36], the inter-molecular interaction strength between ACTR and NCBD needs to be slightly scaled down, which was determined by replica exchange (REX) simulations in combination with Hamiltonian mapping[47, 48]. As shown in Figure 2B, log(Kd) of the final calibrated models shows a strong correlation (R2 = 0.98) with log(Khelix), as observed experimentally[36]. The slopes are also similar for the simulated and experimental values[36] (−0.80 and −0.84, respectively). Consistently, the free energy profiles as a function of the fraction of total inter-molecular native contacts (Qinter), presented in Figure 3A and 3B, illustrate that the bound state becomes increasingly favorable as ACTR gains more helical structures at H1 region. Experimentally, various ACTR mutants were designed without perturbing its electrostatic interactions or inter-molecular interactions in the complex[36]. We assume that the bound state remains similar in all mutants. Therefore, increasing ACTR secondary structures could reduce the overall entropic cost of forming NCBD/ACTR complex, to result in augmented complex stability. By decomposing the free energy into enthalpic and entropic contributions (Figure S1), we found that the overall entropic penalty (T∆S) from unbound state (Qinter = 0) to fully bound state (Qinter = 0.6) was indeed reduced from 78.3 kcal/mol to 73.4 kcal/mol as we increased ACTR H1 helicity from 0.44 to 0.80 (Figure S1B upper inset). Being able to capture the key features of experimentally observed structural and thermodynamic properties, the calibrated Gō-like models should enable us to investigate how residual helicity of ACTR H1 modulates the binding kinetics and pathways of NCBD/ACTR interaction.

Figure 2.

(A) H1 helicity of unbound ACTR (α) at 300 K versus the scaling factor fH1 of intra-molecular interaction strengths within ACTR H1 region. (B) log(Khelix) of H1 of unbound ACTR versus log(Kd) of ACTR/NCBD binding at 300 K from simulation and experiment[36]. The green line is the best-fitted line of simulation data. Khelix = α/(1 − α) and simulated Kd was calculated using Equation 1.

Table 1.

Summary of production simulation details and derived NCBD/ACTR binding kinetic parameters (see Methods for details).

| α | fH1 | finter | tsim (ms) | k+ (μs−1) | k− (μs−1) | kcap (μs−1) | kesc (μs−1) | kevo (μs−1) | Ncap | Nevo | ρevo (%) | MFPTevo (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.44 | 1.4 | 0.977 | 1.79 | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.69 (0.04) | 95.65 (0.41) | 109.15 (0.55) | 0.66 (0.04) | 62484 | 366 | 0.56 | 28.66 |

| 0.49 | 1.5 | 0.973 | 1.76 | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.03) | 94.15 (0.39) | 110.35 (0.43) | 0.67 (0.03) | 58388 | 348 | 0.60 | 29.75 |

| 0.53 | 1.6 | 0.968 | 1.72 | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.52 (0.03) | 93.60 (0.44) | 111.25 (0.49) | 0.67 (0.04) | 54762 | 321 | 0.59 | 28.72 |

| 0.69 | 2 | 0.959 | 1.70 | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.02) | 93.10 (0.52) | 111.25 (0.58) | 0.78 (0.03) | 44312 | 298 | 0.67 | 31.30 |

| 0.80 | 2.5 | 0.955 | 1.60 | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.29 (0.01) | 93.05 (0.70) | 110.65 (0.68) | 0.98 (0.08) | 31481 | 264 | 0.84 | 31.07 |

tsim: accumulated simulation time from 20 independent runs.

ρevo: probability of converting collision complex to fully bound state (i.e., Nevo / Ncap.)

Values in the parenthesis are standard errors of the mean, which is calculated as , where σ is the standard deviation, and n is 20, i.e., the number of independent runs.

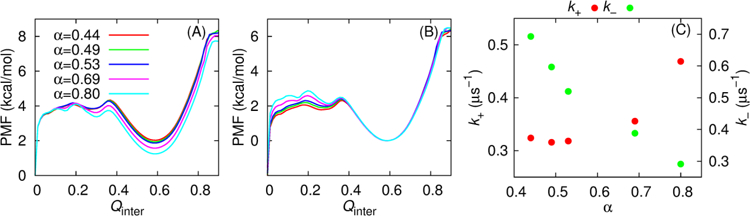

Figure 3.

(A) Potential of mean force (PMF) as a function of Qinter at 314 K for five NCBD/ACTR models. These profiles were obtained from MD production simulations and calculated as −RTln[P(Qinter)], where P(Qinter) is the probability distribution of Qinter, T is the temperature, and R is the gas constant. All traces have been shifted such that the free energy value at Qinter=0 is zero. (B) Same as (A) except that all traces have been shifted that free energy value at Qinter=0.58 is zero. (C) Association and dissociation rates as a function of the H1 helicity of unbound ACTR.

Enhancing ACTR H1 helicity accelerates NCBD binding

An intriguing observation from the experimental study[36] is that stabilizing ACTR H1 increases the association rate constant, and at the same time decreases the dissociation rate constant of ACTR/NCBD complex formation[36]. Even though the Gō-like models were calibrated solely based on thermodynamic properties, they can reproduce the dependence of both association and dissociation rate on ACTR H1 helicity. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 3C, the association rate (k+) is moderately enhanced as ACTR H1 becomes more helical, which is also consistent with decreasing binding free energy barriers as shown in Figure 3A. Free energy decomposition analysis (Figure S1) shows that the binding free energy barrier along Qinter stemmed from the imperfect compensation of the favorable enthalpic and unfavorable entropic contributions, as predicted in the funnel-like free energy landscape theory of protein folding[49]. Stabilizing ACTR H1 results in more favorable interaction energies near the transition state (e.g., Figure S1A inset), thus lowering the free energy barrier of association. We note that the predicted dependence of association kinetics on ACTR H1 helicity is not as linear as observed experimentally, which is likely due to the Cα-only nature of current models. The simulations also predict that the dissociation rate (k−) decreases as α is increased from 0.44 to 0.80 (Figure 3C), which seems to be a direct consequence of increasing stability of the bound state (see Figure 3B).

Accelerated NCBD binding through efficient folding upon encounter

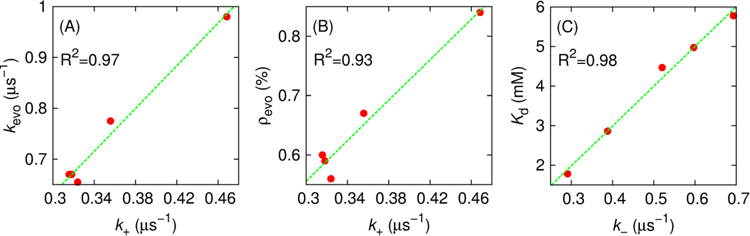

To understand how ACTR H1 helicity enhancement modulates the NCBD/ACTR binding kinetics, we further evaluate its effects on various stages of NCBD/ACTR complex formation. For this, three general states, including the unbound, collision complex and bound states, were defined (see Equation 3) and transitions between these states were extracted from the production trajectories and analyzed. The results are summarized in Table 1. For more disordered ACTR, there were significantly more capture events (Ncap), which seems to be consistent with the fly-casting theory[29]. However, the capture rate (kcap) is only weakly dependent on helicity, consistent with previous analysis showing that fly-casting effects are limited for IDPs [34]. Moreover, the collision complex formation occurs considerably faster than forming the bound complex, and the correlation between capture rate and association rate is very week with R2 = 0.29 (Figure S2), implying that this step alone unlikely determines the overall kinetics of coupled binding and folding of ACTR to NCBD. On the contrary, the evolution rate (kevo) is on the same order of magnitude as the overall binding rate (k+) (Table 1 and Figure 4A) and shows the strongest correlation with k+ (Figure 4A), suggesting that the impacts of increasing ACTR H1 helicity are mainly reflected in kevo.

Figure 4.

(A) Evolution rate and (B) probability of collision complex evolving into the bound state as a function of the associate rate. (C) Kd at 314 K versus the dissociation rate.

Note that both mean first passage time of evolution (MFPTevo) and number of evolution events (Nevo) contribute to the calculation of kevo (Equation 6), and we would like to further understand which one is the dominant factor that leads to increased kevo (and k+) induced by ACTR H1 stabilization. Intriguingly, MFPTevo is on the order of tens of nanoseconds in all cases (Table 1), suggesting that evolution from collision complex to bound state occurs rapidly for successful transitions. This agrees well with previous notion that many rare events are rare because they are infrequent, and not because they are slow (for instance, the protein folding transition path time was found to be 10,000 shorter than the mean waiting time in unfolded state) [50–52]. This observation also implies that NCBD/ACTR complex formation seems to be a sharp, cooperative structural transition, as suggested previously by Dogan and coworkers[53]. Therefore, MFPTevo cannot be used to explain the kinetic advantage of increased ACTR helicity on NCBD binding. As shown in Table 1, MFPTevo indeed doesn’t decrease when ACTR is more helical, and similar insensitivity of MFPTevo in response to changes of ionic strength is also found in the case of PUMA binding to Mcl-1[54]. Instead, greater kevo and k+ arise mainly due to the higher probability of converting collision complex to fully bound state (ρevo) for ACTR variants with more preformed H1 helical structures (Figure 4B). That is, ACTR residual structure accelerates NCBD binding mainly by promoting more efficient folding upon encounter.

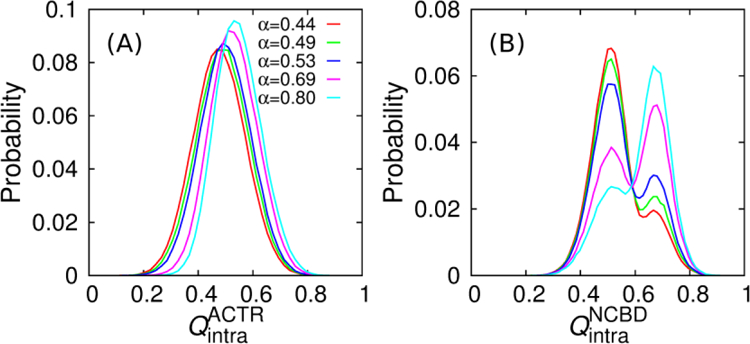

The above findings from kinetic analysis are further supported by the thermodynamic and structural analysis. As shown in Figure 3A, the free energy profiles reveal the presence of a metastable intermediate state at Qinter ≈ 0.3, which appears to be critical for lowering binding free energy barriers as ACTR H1 helicity increases. As shown in Figure 5, when unbound ACTR has a higher level of secondary structures, more native contacts can be formed in both peptides at this intermediate state, which may explain the extra enthalpy gain (Figure S1A inset) that lowers the binding free energy barrier. Furthermore, the presence of energetically more favorable, structurally more ordered intermediate state may be more “folding-competent” both energetically and topologically, which is consistent with the higher probability of collision complex evolving into fully bound state induced by ACTR helicity enhancement (Table 1). Altogether, the current analysis reinforces the pivotal role of efficient folding upon encounter in accelerating the overall kinetics of coupled binding and folding[7, 30–32].

Figure 5.

Distributions of the fraction of native contacts formed within ACTR (A) and NCBD (B) in the intermediated state (0.21 ≤ Qinter ≤ 0.32).

The reduced dissociation rate as ACTR H1 becomes increasingly helical (Table 1) appeared to correlate well with the increased binding affinity between ACTR and NCBD (Figure 4C). This is not surprising considering that dissociation is largely a unimolecular process, where the rate is mainly determined by the depth of the bound free energy minimum[49]. In other words, reduction of dissociation rate is a direct consequence of stronger binding between NCBD and ACTR with increasing ACTR H1 helicity.

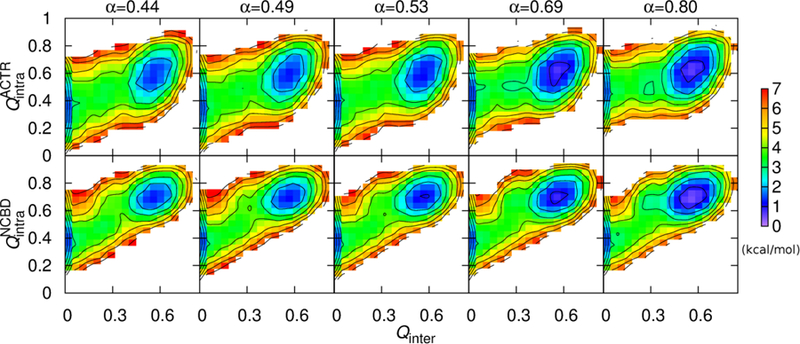

Baseline mechanism of NCBD/ACTR recognition

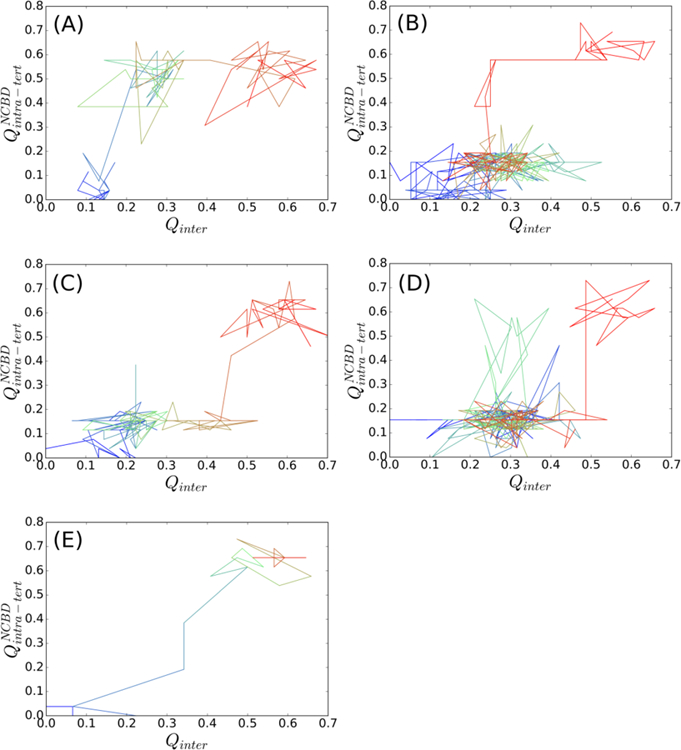

Although the topology-based models neglect many atomistic details and the absolute values presented here may not be directly compared with experimental results, these models were based on the principle of minimal frustration of protein folding[55–57] and should be able to capture the essential mechanistic features, which are referred to as the “baseline mechanism” of coupled binding and folding of IDPs. The carefully calibrated Gō-like models seem to reproduce both thermodynamic and kinetic properties of NCBD/ACTR complex formation, thus allowing us to derive further mechanistic insights into NCBD/ACTR coupled binding and folding. As shown in Figure 6, the overall folding of each peptide is coupled with the binding in a cooperative manner, as the fractions of total intra-molecular native contacts ( and ) increase gradually with Qinter. This is consistent with previous experimental[58] and simulation findings[22, 23, 31]. Such an overall mechanism is conserved as ACTR H1 becomes more helical (Figure 6). Moreover, detailed examination of the transition path ensemble suggests that the ensemble is heterogeneous and transitions at the microscopic level may involve multiple trials and steps (Figure 7). The presence of several intermediate states as well as involvement of both conformational selection (e.g., Figure 7A and 7B) and induced fit (e.g., Figure 7C and 7D) pathways seems to agree with the “extended conformational selection” model[59]. These mechanistic features have been described in detail in our previous work[22].

Figure 6.

2D free energy profiles at 314 K as a function of Qinter and (top) or (bottom). Contour levels are drawn at every 1 kcal/mol.

Figure 7.

Representative transitions from unbound to bound state. The traces were color in time ordering from blue to red. (A) and (B) are for conformational selection like pathways, and (D) for induced fit like pathways, and (E) for other pathways. Transient, but non-productive visit of alternative pathways was present in (B) and (D), but absent in (A) and (C).

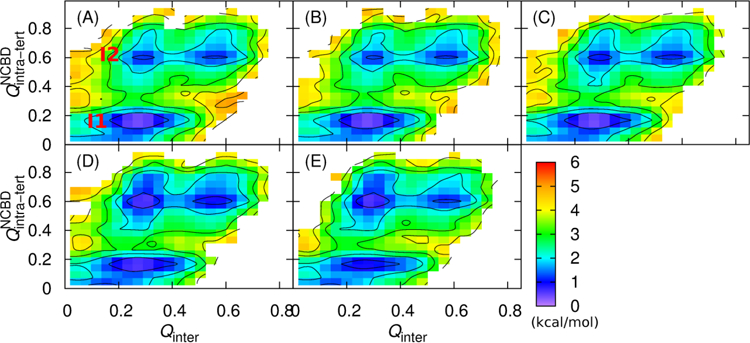

Stabilizing ACTR H1 results in continued differences in the pathway of coupled binding and folding. We have analyzed all productive transitions from unbound to bound states by monitoring the change of NCBD intra-molecular tertiary structures in response to ACTR binding. Figure 8 shows the 2D free energy profiles as a function of and Qinter, which reveal how the relative populations of two key intermediates (I1 and I2 in Figure 8A) change with increasing ACTR H1 helicity. For more disordered ACTR H1, intermediate state I1 appears to be dominant, where most tertiary structures within NCBD were not formed (e.g., see Figure 8A). As ACTR H1 becomes increasingly helical, the population of intermediate state I2 increases, where NCBD has already gained significant amount of tertiary structures when only ~25% of native contacts between NCBD and ACTR have been formed (e.g., see Figure 8E). Such shift of relative populations of I1 and I2 also suggests that as ACTR H1 became more helical, there is a greater chance that NCBD could become folded before reach the fully bound state. This is consistent with the previous notion that enhancing the helicity of ACTR H1 results in an intermediate state with “folding-competent” topology, thus promoting efficient folding upon encounter and accelerating its association with NCBD.

Figure 8.

2D free energy profiles at 314 K as a function of and Qinter calculated from transition path ensembles. Panels A–E are for α = 0.44, 0.49, 0.53, 0.69 and 0.80, respectively. Contour levels are drawn at every 1 kcal/mol.

Conclusions

Recent NMR structural studies and stopped-flow kinetic measurements have shown that increasing helicity of ACTR H1 not only enhances the stability of NCBD/ACTR complex, but also accelerates the association rate while decelerating the dissociation rate[36]. This is surprising because previous studies have generally emphasized the importance of conformational flexibility in IDP recognition and stabilizing residual helicities have been found to either reduce the binding kinetics or have minimal impacts[18, 27, 28]. Here we have constructed a series of topology-based coarse-grained models that were carefully calibrated by reproducing key thermodynamic properties of the unbound state and NCBD/ACTR interaction. Through milliseconds of MD simulations, hundreds of reversible binding and folding transitions were generated to analyze the kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanism of NCBD/ACTR interaction.

The results show that with an increasing amount of preformed structural elements in unbound IDPs, the overall entropic cost of forming NCBD/ACTR complex is reduced, which leads to increased binding affinity and thus reduced dissociation rate. Increasing ACTR helicity does not significantly alter the baseline mechanism of the synergistic folding of ACTR and NCBD during association, which continues to follow an “extended conformational selection” model with multiple stages of selection and induced folding. Increasing residual structure in ACTR H1, however, results in a higher probability of productive evolution of nonspecific collision complexes to the final bound and folded state, and this is shown to be the primary source of accelerated association kinetics. Taken together, this study provides mechanistic insights into how residual structure modulates thermodynamics and kinetics of coupled binding and folding of IDPs and highlights the importance of efficient folding upon encounter in such processes.

Methods

Topology-based coarse-grained models of NCBD/ACTR

A Cα-only sequence-flavored Gō-like model was previously derived for the wild-type NCBD/ACTR complex (see Figure 1)[22]. Briefly, this model was built based on PDB structure 1KBH[60] (model 1) using the MMTSB Gō-Model Builder (http://www.mmtsb.org)[57, 61]. It was then calibrated to recapitulate the overall residual structure level of unbound peptides and the binding affinity. This was achieved by first uniformly scaling the interaction strengths of intra-molecular native contacts, to reproduce the experimental residual helicity profiles of unbound peptides. The interaction strengths of inter-molecular native contacts were then scaled to match the simulated binding affinity of the complex with experimental values. In this model, the total numbers of native contacts between peptides (Ninter), within NCBD , within ACTR and in NCBD intra-molecular tertiary structures are 76, 78, 49 and 26, respectively.

To model ACTR variants with different H1 residual helicities, the above Gō-like model was further tuned by uniformly scaling its interaction strengths of all intra-molecular native contacts within segment H1. Scaling factors for ACTR H1 (fH1) were set at 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 2.0 and 2.5 for five ACTR variants, which yield H1 residual helicities (α) ranging from 0.44 to 0.80 (see Table 1), comparable to the experimental values for mutants studied by Kjaergaard and coworkers[36]. For each model, the inter-molecular interaction strengths between ACTR variant and NCBD were uniformly rescaled, such that the calculated thermodynamic stability of the NCBD/ACTR complex matched the experimental value[36]. This fine-tuning was performed using replica exchange (REX) simulations in combination with Hamiltonian mapping[48, 62]. The inter-molecular scaling factors (finter) in the five final models are 0.977, 0.973, 0.968, 0.959 and 0.955, respectively (see Table 1).

Simulation protocols

All MD simulations were performed using CHARMM[63, 64], and REX simulations were performed using CHARMM[63, 64] with MMTSB[65]. Langevin dynamics was used with a friction coefficient of 0.1 ps−1 and a time step of 10 fs. All bond lengths were constrained using SHAKE[66].

To compute the averaged helicities of ACTR H1, 1 μs MD simulations of ACTR alone were performed at 300 K. For all simulations of NCBD/ACTR, the complex was put in a cubic box with the size of 105 Å under periodic boundary conditions. First, a REX simulation of the complex was performed for 2 μs using the original Gō-like model[22] to generate structural ensembles. Hamiltonian mapping[48, 62] was then used to identify scaling parameters that would reproduce the experimental stabilities. 2 μs REX simulations using these new models were then carried out to verify the stability of the complex. After model calibration, all production simulations of the NCBD/ACTR complexes were performed at 314 K, near the melting temperatures. For each model, 20 independent simulations were initiated from random conformations. The accumulated simulation times ranged from 1.60 to 1.79 ms for each complex (Table 1), which yielded hundreds of reversible binding/unbinding transitions for reliable analysis of kinetic rates and pathways. Simulation trajectories were saved every 100 ps for analysis.

Analysis

To calculate the average helicity, we first calculated the number of (i, i+4) Cα-Cα contacts in ACTR H1. A contact is considered to be formed if the Cα-Cα distance is no more than 1 Å greater than that in the fully folded state (PDB: 1KBH). The overall helicity of ACTR H1 was then calculated as the ensemble-averaged fraction of (i, i+4) Cα-Cα native contacts formed.

For the complex, the dissociation constants (Kd in M) were computed from the bound probabilities (pb) as[22]

| (1) |

where V0 is the volume of simulation box in Å3. Conformations with Ninter ≥ 44 are considered bound.

All kinetic information was derived from production simulations of the complex. Both the binding (k+) and unbinding rates (k−) were calculated directly as the inverse of corresponding mean first passage times (MFPTs) between the bound (B) and unbound (U) states (Equation 2), where the two states were defined as Ninter ≥ 44 and Ninter < 1, respectively. Running average over 10 ns was performed before assigning the states to suppress fictitious high frequency transitions.

| (2) |

To further understand how residual helical stability may affect different stages of coupled binding and folding, three general conformational states were defined, including an additional collision complex (CC) state,

| (3) |

where kcap, kesc, and kevo are capture, escape and evolution rates, respectively. Here, the unbound state was more strictly defined as conformations without specific or nonspecific inter-molecular contacts (i.e., Ninter < 1 and ). CC includes conformations with only nonspecific inter-molecular contacts (i.e., Ninter < 1 and ). Again, running average over 10 ns was performed before state assignment. kcap, kesc, and kevo were calculated from number of transitions and MFPT between states as described previously[31, 42]:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Ncap, Nesc, and Nevo are the numbers of capture, escape, and evolution transitions, respectively.

Ensembles of transition path trajectories were collected from production MD simulations to further analyze the pathways of NCBD/ACTR synergistic folding. Each transition path trajectory was defined between the fully unbound state (Ninter = 0 and ) last visited and the fully bound state (Ninter ≥ 50) first visited (e.g., see Figure 7). The more stringent state criteria are necessary to eliminate spurious, noncommitting transitions. Very few intra-molecular tertiary contacts were present in bound state of ACTR[22], thus we didn’t examine ACTR folding upon binding. NCBD is a molten globular protein with a high level of secondary structures in the unbound state. Its binding-induced folding was analyzed by tracking its intra-molecular tertiary structure formation, quantified by .

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mechanistic roles of residual structure in IDP binding remain intensely debated.

Topology-based modeling recapitulates increasing ACTR helicity enhances binding rate

Residual helices mainly promote more efficient folding following binding.

Efficient folding upon binding is critical for achieving fast IDP association kinetics

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM114300) and National Science Foundation (MCB 1817332). The simulations were performed at Massachusetts Green High-Performance Computing Center (MGHPCC).

Abbreviations:

- ACTR

activation domain of the activator for thyroid hormone and retinoid receptors

- IDP

intrinsically disordered proteins

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MFPT

mean first passage time

- NCBD

the nuclear coactivator binding domain of CREB-binding protein

- REX

replica exchange

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: None.

References

- [1].Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol 1999;293:321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015;16:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Showing your ID: intrinsic disorder as an ID for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J Mol Recognit 2005;18:343–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Babu MM, van der Lee R, de Groot NS, Gsponer J. Intrinsically disordered proteins: regulation and disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2011;21:432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Click TH, Ganguly D, Chen J. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in a Physics-Based World. Int J Mol Sci 2010;11:5292–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen JH. Towards the physical basis of how intrinsic disorder mediates protein function. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2012;524:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tsai CJ, Ma B, Sham YY, Kumar S, Nussinov R. Structured disorder and conformational selection. Proteins 2001;44:418–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Das RK, Ruff KM, Pappu RV. Relating sequence encoded information to form and function of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015;32:102–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smock RG, Gierasch LM. Sending signals dynamically. Science 2009;324:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2009;19:31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z. Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:6573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J Mol Biol 2002;323:573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shammas SL, Crabtree MD, Dahal L, Wicky BIM, Clarke J. Insights into Coupled Folding and Binding Mechanisms from Kinetic Studies. J Biol Chem 2016;291:6689–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rogers JM, Oleinikovas V, Shammas SL, Wong CT, De Sancho D, Baker CM, et al. Interplay between partner and ligand facilitates the folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:15420–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arai M, Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins influence the mechanism of binding and folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:9614–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Toto A, Camilloni C, Giri R, Brunori M, Vendruscolo M, Gianni S. Molecular Recognition by Templated Folding of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. Sci Rep 2016;6:21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rogers JM, Wong CT, Clarke J. Coupled Folding and Binding of the Disordered Protein PUMA Does Not Require Particular Residual Structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014;136:5197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Crabtree MD, Mendonca C, Bubb QR, Clarke J. Folding and binding pathways of BH3-only proteins are encoded within their intrinsically disordered sequence, not templated by partner proteins. J Biol Chem 2018;293:9718–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dahal L, Kwan TOC, Shammas SL, Clarke J. pKID Binds to KIX via an Unstructured Transition State with Nonnative Interactions. Biophys J 2017;113:2713–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ganguly D, Chen J. Atomistic details of the disordered states of KID and pKID. implications in coupled binding and folding. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:5214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ganguly D, Zhang W, Chen J. Synergistic folding of two intrinsically disordered proteins: searching for conformational selection. Mol BioSyst 2012;8:198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang W, Ganguly D, Chen J. Residual structures, conformational fluctuations, and electrostatic interactions in the synergistic folding of two intrinsically disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 2012;8:e1002353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fisher CK, Stultz CM. Constructing ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2011;21:426–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fuxreiter M, Simon I, Friedrich P, Tompa P. Preformed structural elements feature in partner recognition by intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol 2004;338:1015–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Borcherds W, Theillet FX, Katzer A, Finzel A, Mishall KM, Powell AT, et al. Disorder and residual helicity alter p53-Mdm2 binding affinity and signaling in cells. Nature chemical biology 2014;10:1000–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bienkiewicz EA, Adkins JN, Lumb KJ. Functional consequences of preorganized helical structure in the intrinsically disordered cell-cycle inhibitor p27(Kip1). Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;41:752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Turjanski AG, Gutkind JS, Best RB, Hummer G. Binding-induced folding of a natively unstructured transcription factor. PLoS Comput Biol 2008;4:e1000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shoemaker BA, Portman JJ, Wolynes PG. Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: The fly-casting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:8868–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ganguly D, Otieno S, Waddell B, Iconaru L, Kriwacki RW, Chen J. Electrostatically Accelerated Coupled Binding and Folding of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J Mol Biol 2012;422:674–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ganguly D, Zhang W, Chen J. Electrostatically Accelerated Encounter and Folding for Facile Recognition of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9:e1003363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhou HX. From Induced Fit to Conformational Selection: A Continuum of Binding Mechanism Controlled by the Timescale of Conformational Transitions. Biophys J 2010;98:L15–L7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. The protein folding ‘speed limit’. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2004;14:76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang Y, Liu Z. Kinetic advantage of intrinsically disordered proteins in coupled folding– binding process: a critical assessment of the “fly-casting” mechanism. J Mol Biol 2009;393:1143–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014;16:6323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Iešmantavičius V, Dogan J, Jemth P, Teilum K, Kjaergaard M. Helical propensity in an intrinsically disordered protein accelerates ligand binding. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2014;53:1548–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Arai M, Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins influence the mechanism of binding and folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences 2015;112:9614–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Giri R, Morrone A, Toto A, Brunori M, Gianni S. Structure of the transition state for the binding of c-Myb and KIX highlights an unexpected order for a disordered system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:14942–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hill SA, Kwa LG, Shammas SL, Lee JC, Clarke J. Mechanism of Assembly of the Non-Covalent Spectrin Tetramerization Domain from Intrinsically Disordered Partners. J Mol Biol 2014;426:21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ganguly D, Chen J. Topology-based modeling of intrinsically disordered proteins: balancing intrinsic folding and intermolecular interactions. Proteins 2011;79:1251–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Knott M, Best RB. A preformed binding interface in the unbound ensemble of an intrinsically disordered protein: evidence from molecular simulations. PLoS Comput Biol 2012;8:e1002605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang Y, Liu Z. Kinetic advantage of intrinsically disordered proteins in coupled folding-binding process: a critical assessment of the “fly-casting” mechanism. J Mol Biol 2009;393:1143–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wolynes PG. Recent successes of the energy landscape theory of protein folding and function. Q Rev Biophys 2005;38:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lu Q, Lu HP, Wang J. Exploring the mechanism of flexible biomolecular recognition with single molecule dynamics. Phys Rev Lett 2007;98:128105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang J, Wang Y, Chu X, Hagen SJ, Han W, Wang E. Multi-Scaled Explorations of Binding-Induced Folding of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Inhibitor IA3 to its Target Enzyme. PLoS Comput Biol 2011;7:e1001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Law SM, Gagnon JK, Mapp AK, Brooks CL 3rd. Prepaying the entropic cost for allosteric regulation in KIX. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:12067–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Law SM, Ahlstrom LS, Panahi A, Brooks CL III. Hamiltonian Mapping Revisited: Calibrating Minimalist Models to Capture Molecular Recognition by Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2014;5:3441–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Shea JE, Nochomovitz YD, Guo ZY, Brooks CL. Exploring the space of protein folding Hamiltonians: The balance of forces in a minimalist beta-barrel model. J Chem Phys 1998;109:2895–903. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wolynes PG. Evolution, energy landscapes and the paradoxes of protein folding. Biochimie 2015;119:218–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhang BW, Jasnow D, Zuckerman DM. Efficient and verified simulation of a path ensemble for conformational change in a united-residue model of calmodulin. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences 2007;104:18043–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chung HS, Louis JM, Eaton WA. Experimental determination of upper bound for transition path times in protein folding from single-molecule photon-by-photon trajectories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:11837–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Neupane K, Ritchie DB, Yu H, Foster DAN, Wang F, Woodside MT. Transition Path Times for Nucleic Acid Folding Determined from Energy-Landscape Analysis of Single-Molecule Trajectories. Physical review letters 2012;109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dogan J, Mu X, Engstrom A, Jemth P. The transition state structure for coupled binding and folding of disordered protein domains. Sci Rep-Uk 2013;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chu WT, Clarke J, Shammas SL, Wang J. Role of non-native electrostatic interactions in the coupled folding and binding of PUMA with Mcl-1. PLoS computational biology 2017;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Spin glasses and the statistical mechanics of protein folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences 1987;84:7524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struc Biol 2004;14:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Karanicolas J, Brooks CL. The origins of asymmetry in the folding transition states of protein L and protein G. Protein Sci 2002;11:2351–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dogan J, Schmidt T, Mu X, Engstrom A, Jemth P. Fast association and slow transitions in the interaction between two intrinsically disordered protein domains. The Journal of biological chemistry 2012;287:34316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Csermely P, Palotai R, Nussinov R. Induced fit, conformational selection and independent dynamic segments: an extended view of binding events. Trends Biochem Sci 2010;35:539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Demarest SJ, Martinez-Yamout M, Chung J, Chen HW, Xu W, Dyson HJ, et al. Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature 2002;415:549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Karanicolas J, Brooks CL. Improved Go-like models demonstrate the robustness of protein folding mechanisms towards non-native interactions. J Mol Biol 2003;334:309–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Law SM, Ahlstrom LS, Panahi A, Brooks CL 3rd. Hamiltonian Mapping Revisited: Calibrating Minimalist Models to Capture Molecular Recognition by Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2014;5:3441–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. Charmm - a Program for Macromolecular Energy, Minimization, and Dynamics Calculations. J Comput Chem 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Brooks BR, Brooks CL, Mackerell AD, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, et al. CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program. J Comput Chem 2009;30:1545–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks CL. MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J Mol Graphics Modell 2004;22:377–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical-Integration of Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints - Molecular-Dynamics of N-Alkanes. J Comput Phys 1977;23:327–41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.